Motion to Vacate Suspension of and Reinstate Order Pending Certiorari

Public Court Documents

September 30, 1969

8 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Alexander v. Holmes Hardbacks. Motion to Vacate Suspension of and Reinstate Order Pending Certiorari, 1969. 7a365d48-cf67-f011-bec2-6045bdffa665. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/79ed61e6-5da9-4373-b0ae-6a7c5e8333ae/motion-to-vacate-suspension-of-and-reinstate-order-pending-certiorari. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

A »

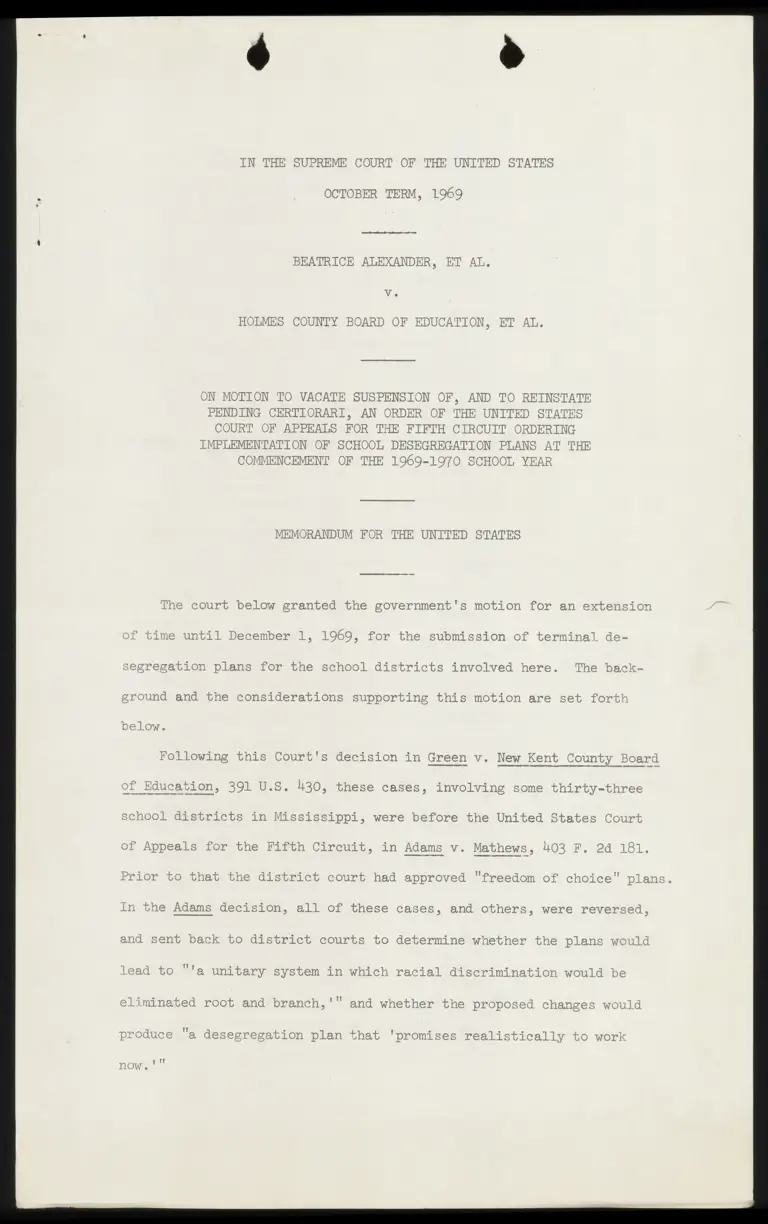

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

OCTOBER TERM, 1969

BEATRICE ALEXANDER, ET AL,

Ve

HOLMES COUNTY BOARD OF EDUCATION, ET AL.

ON MOTION TO VACATE SUSPENSION OF, AND TO REINSTATE

PENDING CERTIORARI, AN ORDER OF THE UNITED STATES

COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT ORDERING

IMPLEMENTATION OF SCHOOL DESEGREGATION PLANS AT THE

COMMENCEMENT OF THE 1969-1970 SCHOOL YEAR

MEMORANDUM FOR THE UNITED STATES

The court below granted the government's motion for an extension

* time until December 1, 1969, for the submission of terminal de-

segregation plans for the school districts involved here. The back-

ground and the considerations supporting this motion are set forth

below.

Following this Court's decision in Green v. New Kent County Board

of Education, 391 U.S. 430, these cases, involving some thirty-three

school districts in Mississippi, were before the United States Court sch

Of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit, in Adams v. Mathews, $03 FP. 24 181.

Prior to that the district court had approved "freedom of choice" plans.

In the Adams decision, all of these cases, and others, were reversed,

and sent back to district courts to determine whether the plans would

lead to "'a unitary system in which racial discrimination would be

! eliminated root and branch,'" and whether the proposed changes would

produce "a desegregation plan that "promises realistically to work

¢

- Dw

On remand, the district court again approved the “freedom of choice”

plans. The United States again appealed to the court of appeals, and an

expedited procedure was followed in that court. The United States asked

for orders which would lead to desegregation in most of the schools

beginning in the fall of 1969. In the proceedings before the court of

appeals, the United States stated its belief that such plans could be

developed and put into effect within the time available, and the United

States proposed a timetable for the development and implementation of the

plans.

In these proceedings in the court of appeals, the United States also

suggested that the Department of Justice was not expert in educational

administration, and that better progress might be made if experienced

educators from the Department of Health, Education and Welfare were

brought into the picture.

The court of appeals adopted all of the recommendations of the

United States. It ordered the district court to formulate plans which

would "disestablish the dual school systems in question.” It also

ordered the district court to request "that educators from the Office

of Education of the United States Department of Health, Education and

Welfare collaborate with the defendant school boards in the preparation

of plans" which would carry out the court's order. Finally, it set up

a timetable--admittedly a very tight one--under which plans should be

presented to the district court by August 11, 1969, for hearing on

August 21, 1969, and to be implemented by the district court no later

than August 25, 1969--a date which was later changed by the court of

appeals to September 1, 1969.

The Department of Health, Education and Welfare filed plans by

August 11, 1969. On August 19, 1969, Robert H. Finch, Secretary of

Health, Education and Welfare of the United States, sent a letter to

“ »

“3m

Chief Judge Brown of the court of appeals, and to the three district

judges involved in the case, requesting the court to grant a further

delay until December 1, 1969. The court of appeals directed the district

court to consider this request, and a motion filed by the United States

based on the request, and to make recommendations with respect to it.

The district court held a hearing, and recommended that the Secretary's

request be granted. This has been approved by the court of appeals, which

has amended its earlier order, by eliminating the September 1, 1969, dead-

line, and fixing a new deadline of December 1, 1969. The court, at the

suggestion of the Department of Justice, also ordered each of the Boards,

in conjunction with the Office of Education, to "develop a program to

prepare its faculty and staff for the conversion from the dual to the

unitary system" and to do this by October 1, 1969. Finally, also at

the suggestion of the Department of Justice, the Boards were ordered

not to construct any new facilities "until a terminal plan has been

approved by the court."

The Office of Education of the Department of Health, Education and

Welfare was given specific responsibilities by the order of the court

of appeals entered on July 3, 1969. Although there was no reference to

the Secretary of Health, Education and Welfare in this order, he is the

officer who is responsible for the activities of the entire Department,

including the Office of Education. In effect, the Office of Education,

and through it, the Secretary of Health, Education and Welfare, were

made a sort of collective "Special Master" for the purpose of assisting

the district court in carrying out its undenisbly exceedingly difficult

task. The Office of Education did endeavor to comply with its assign-

ment, but when the Secretary had an opportunity to review the plans, he

concluded that the immediate implementation of the plans would involve

great difficulties and would be extremely disruptive. Having the

responsibility which undoubtedly rested upon him, and having no time

¢ »

- ie

at all available, he had little practical alternative but to make the

report to the court which he did.

It might be suggested that the Secretary could have written a more

discriminating and eclectic letter, explaining in more detail the reasons

for his judgment, saying that some plans were all right, that some others

needed modification, and that still others required further consideration

because of special problems which he then pointed out. But the situation

was far too complex for that. There are thirty-three school systems in-

Se

volved, with 166 schools, and close to 2,000 teachers--and there was

literally no time left in which the Secretary might consider all the

problems involved.

Of course there is great pressure to bring desegregation, and to

bring it now. Fifteen years have passed since this Court's decision in

the Brown caver hers can be little doubt where the basic fault lies

in this matter. The reason why the plans are so difficult to formulate

and to implement is largely because the local school boards involved in

this case have generally done nothing but resist; they have continuously

failed and refused to develop plans for the effective desegregation of

their schools, so as to eliminate the long-established dual school

System. | The temptation to say that they must obey the law, and that

Stier Tat do it by an imminent fixed date, is very great. That is

what the court of appeals did in its original order in these cases.

But the court of appeals also sought the help of the Department of

Health, Education and Welfare in implementing its order. When looked

at in gross the fixed deadline had seemed feasible. When looked at

in detail by the Secretary, however, he concluded there were too many

unresolved problems to leave it possible for him to feel conscientiously

that he could approve the plans. Much experience shows that desegre-

gation plans are more effective, are more readily accepted and carried

out, when there is some opportunity for preparation of the community,

—

¢ »

ea

and particularly when the details of the plans can be explained to the

teachers involved, and their support enlisted. Under the draconian

order of the court of appeals--requested by the United States, it is

true--there was no opportunity for this preliminary groundwork. Be-

TT ——— pe ——————— ———

m————

cause of the failure of the local Boards to cooperate, none of the

preliminary planning and work had been done, and when August 19th

ity there was no time left in which this could be planned and

carried out. If only a single school system had been involved, or two

or three school systems, it might have been possible to put on some

sort of a crash program which would have given some prospect of success.

But there are thirty-three school systems concerned in these cases.

There was no prospect at all that the necessary detailed planning and

work could be done to make the plans ones which would meet this Court's

directive that there should be a plan of desegregation that "promises

realistically to work now."

Neither the courts below nor the Department of Justice are experts

on education. They are concerned with constitutional requirements, and

that concern obviously remains a deep commitment. The Office of

Education does have educational experience, and the Secretary is

responsible for its actions. What the Secretary has said in substance

is: "The plans won't work. We need more time, until December lst."

It is recognized that this means, in most situations, another school

year, and that is a tragedy and a default. But it may be less of a

default in the long run than would be forcing through plans now which

are not sufficiently developed, and do not hold out adequate prospect

of success. At any rate that was the Secretary's considered judgment,

reached under grea’ difficulties. His recommendation has been sup-

ported by both courts below. That action, by judges close to the scene,

should not be interfered with by a Justice of this Court. The court

below has clearly indicated that it intends the desegregation process to go

é M

-C-

forward as quickly as possible. Its conclusion that it should forego

its original deadline and fix a new one should be given considerable

weight. |

The position taken by the Secretary was supported the testimony

of two government expert witnesses which was given at the hearing in the

district court on August 25, 1969. The qualifications of these witnesses,

and their testimony, may be summarized as follows:

1. Jesse J. Jordan, Senior Program Officer for Title IV, U. S.

Office of Education, Atlanta, Georgia} Bachelor's Degree in Mathematics

and Education; Master's Degree in School Administration; three years as

a teacher and three years as a principal; twelve years as a school

administrator in elementary and secondary education, including holding

the position of Assistant Superintendent.

2. Howard O. Sullins, Program Officer, Office of Education,

Charlottesville, Virginia} Bachelor's Degree in English and History;

Master's Degree, Columbia University, in Education; completed all re-

quirements for a Doctorate in Education from the University of Virginia

in the field of administration and supervision, except for completion

of his dissertation which is currently being written; four years a

classroom teacher; thirteen years a high school principal; three years

superintendent of schools.

Jordan served as a member of the committee which reviewed all of

the plans in the instant cases, talked with and worked closely with

those educators who were in the field actually Sovaleting both the

facts for and the plans themselves.

Sullins testified that he had Geo the team leader that developed

the plans for the Hinds, Madison and Canton school districts; that he

had personally gathered the facts, interviewed the superintendent and

other administrators within these districts and discussed the entire

* »

- 7 =

problem with the school boards of the districts involved. His testimony

shows that he was as familiar with the details of these three districts

as one could rogsivie be within the short period of time that was

allotted to him to undertake the investigation, and to analyze the

information and draft a desegregation plan.

_ Both witnesses testified that in general they believe that the

plans prepared by the Office of Education experts were reasonable,

educationally sound and would result in an administratively feasible

unitary school organization. Both agreed, however, that they did not

have sufficient time to conduct detailed studies of such things as

curriculum, finances and transportation which would ordinarily be done

when reorganizing a school system.

These witnesses testified that a unitary school system is superior

educationally to a dual school system. These witnesses further testi-

fied that, in their judgment, there was insufficient time to implement

the Office of Education plans in time for this school year. For example,

Sullins testified:

Since there is then a rather massive job of reorganization

and in most cases restructuring of the grades in a parti-

cular school, considerable time should be spent in properly

planning the educational program which will be made avail-

able for the boys and girls in these schools. (Tr. 1khh.)

Sullins went on to describe problems with respect to revamping the

transportation routes (Tr. 1L4), reorganizing the faculties (Tr. 145),

preparing the students (Tr. 145-146), replanning federally funded projects

(Tr. 146-147), and rescheduling of high school classes (Tr. 187-188). He

testified that in the school systems in which he Wane he saw no evidence

of any planning for the implementation of his desegregation plan or any

other desegregation plan which would disestablish the dual school system

(Tr. 186). According to Sullins, "It is my professional judgment that in

order to make a desegregation plan work, it must be properly planned"

(Tr. 186). Jordan and Sullins both testified that the transition from

dual to unitary school systems is smoother if school districts move to-

gether. (Tr. 97-98, 148.)

é i

WEE ip

The petitioners offered the testimony of a highly-qualified edu-

cator but on cross-examination it was established that this witness

had no experience whatsoever in local, elementary and secondary school

administration and had no particular knowledge of the school districts

involved.

The duty of a school board in these cases is to convert from a

dual to a unitary school system. The objective is the disestablishment

of the dual school system through the use of plans "realistically"

designed to work. Where the local school districts refuse to come for-

ward with such plans, as the vast majority did here, the United States,

in order to aid the district courts in the desegregation process, must

take upon itself the additional burden of designing such plans. The

United States has done so, willingly and with every hope of success,

but this is no easy task and it is sometimes fraught with the frus-

trations of unfamiliarity and the pressures of time. The Secretary of

the Department of Health, Education and Welfare, as the Cabinet officer

charged with implementing the federal government's interests in elementary

and secondary education, takes upon himself in these situations a tremen-

dous burden, for his obligation is to achieve a sound, feasible, realistic

program of education for all the children, both Negro and white, in these

school districts, unfortunately presided over by recalcitrant and re-

luctant public officials, whose duties and functions must be carried out

by others.

In this situation, great weight and consideration should be given

to the opinion of the Secretary whose Department was brought into the

situation by the court below.

We respectfully submit that the judgment of the court of appeals--

a court which has shown particular sensitivity to the need and importance

of prompt and vigorous action to accomplish effective desegregation--should

not be suspended.

ERWIN N. GRISWOLD,

Solicitor General.

SEPTEMBER 1969.