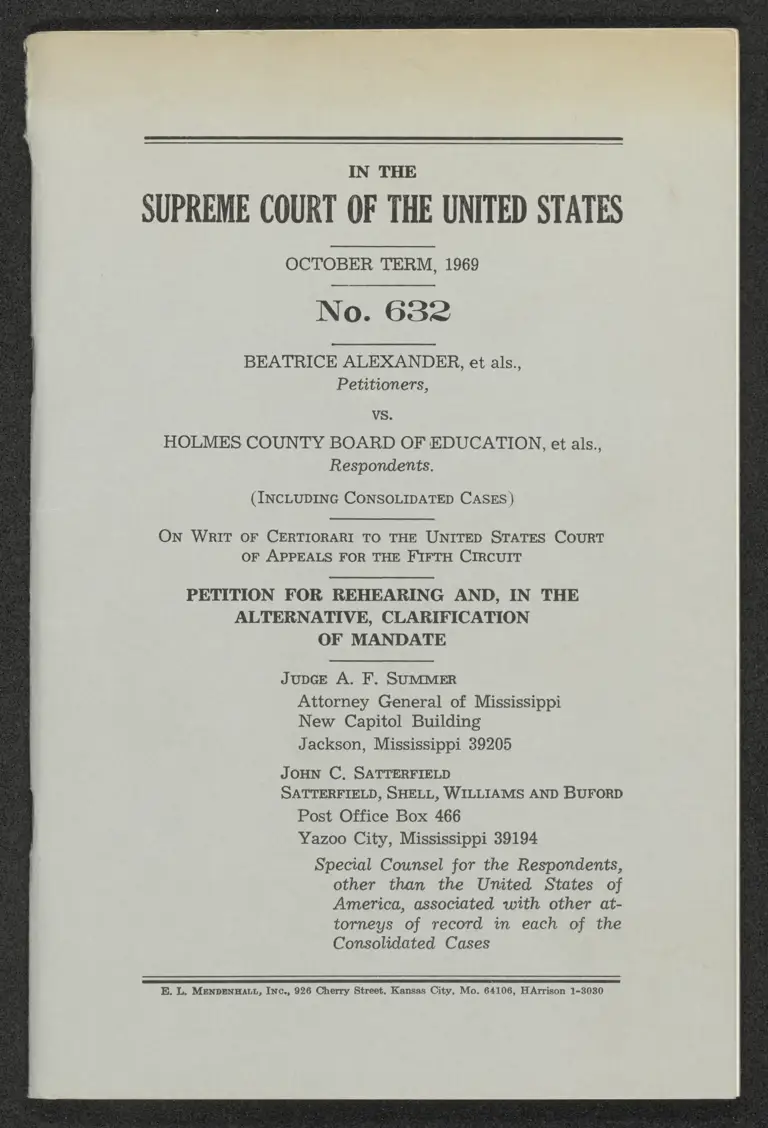

Petition for Rehearing and, in the Alternative, Clarification of Mandate

Public Court Documents

November 21, 1969

48 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Alexander v. Holmes Hardbacks. Petition for Rehearing and, in the Alternative, Clarification of Mandate, 1969. 7f204e3d-cf67-f011-bec2-6045bdd81421. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/7a1ebdc0-5c2c-4d1b-a362-a612a9db3be3/petition-for-rehearing-and-in-the-alternative-clarification-of-mandate. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

OCTOBER TERM, 1969

No. 632

BEATRICE ALEXANDER, et als.,

Petitioners,

VS.

HOLMES COUNTY BOARD OF EDUCATION, et als.,

Respondents.

(IncLuDING CONSOLIDATED CASES)

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT

OF APPEALS FOR THE FiFTH CIRCUIT

PETITION FOR REHEARING AND, IN THE

ALTERNATIVE, CLARIFICATION

OF MANDATE

JupGe A. F. SUMMER

Attorney General of Mississippi

New Capitol Building

Jackson, Mississippi 39205

JOHN C. SATTERFIELD

SATTERFIELD, SHELL, WILLIAMS AND BUFORD

Post Office Box 466

Yazoo City, Mississippi 39194

Special Counsel for the Respondents,

other than the United States of

America, associated with other at-

torneys of record in each of the

Consolidated Cases

BE. L. MENDBENHALL, INC., 926 Cherry Street. Kansas City, Mo. 64106, HArrison 1-3030

INDEX

Preliminary SIalement .............c.ccocciincnsntiictnenios oxtsizones 1

I. The Respondents Have Not Been Accorded Due

Process of Law. There Has Been No Hearing on

the Merits by Any Court nor Any Opportunity

for the Litigants to Be Heard on the Merits

Through Their Atlormeys i... ...... oh 1

II. The Judgment Now Entered by the Court of

Appeals Conflicts with Decisions of the Courts

of Appeal of Other: Circuits oi... iin. il. 8

III. The Constitutional Duty to Remove Vestiges of

the Dual System of Public Schools Does Not Re-

quire the Entry of These Judgments .................... 15

IV. The HEW Plans, with the Inclusion of the Alter-

native or “Interim” Steps in Student and Faculty

Integration, Would Put into Immediate Effect

Unitary Racially Non-Discriminatory School

SYSIEME ol. to eee rss nsesssseunans 22

Exhibit A—Illustrations of “Composite Building In-

formation”. Contained. in HEW Plans .........cccc. coe. oot. 31

CONCUSSION .......000. 200 Be... 25a mevese sets rosstisrsnsvensasions 37

Certificate of Bervice: wo... cirri serorsnisnsves titernes 38

TABLE oF CASES

Adams v. Mathews, 403 F.2d 181 (5th Cir. 1968) ...........

A Et ee, i 8,11,12,13, 24, 25, 26, 27

Broussard v. Houston Ind. School District, 395 F.2d

Br re see 21

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483, 74 S.Ct.

658,98 LEA 873 (1054). i... eerie, 13,15

Carr .v. Montgomery. County, 23 1.84.24 263. .............

16,22,23, 24. 29

II INDEX

Clark v. Board of Education of Little Rock School

District, 369 F.2d 661, rehearing denied, 374 F.2d

SR en lil hel 17,13

Deal v. Cincinnati Board of Education, 369 F.2d 55

(6th Cir. 1966), cert. denied, 389 U.S. 847, 83 S.Ct.

39, 19 T.UA2d 114 (1867) . . ir 10,11

Downs v. Board of Education of Kansas City, 336 F.2d

988 (1964), cert. denied, 380 U.S. 914, 85 S.Ct. 898,

13 L.Ed.2d S00 (1865) ..........ooccncevmenisconsivissitter mis msscsseitnions 13

Goss v. Board of Education of Knoxville, Tennessee,

ETA Re ERR 3, 11,17, 13

Green v. County School Board of New Kent County,

Virginia 381: US. 430 (1968) +... vvciiiioncnrionns

i RT ea 9, 10, 15, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 28

Hovey. v. Zllioit, 167 U.S. 408, 42 1. E4. 415 .................. 5

Mapp v. Board of Education of Chattanooga, Tennessee,

A 2 Br a 14

Monroe v. Board of Commissioners of the City of Jack-

son, Tennessee, 350 F.2d 955: (6th Cit.) .—coveeceeeeenene-

I a 9.15,16,17,22,23,24. 25,23

Morgan v. United States of America, 304 U.S. 13, 82

LEA 1129 6

Powell v. Alabama, 297 U.S. 45, 77 1. Bd. 153 ........coeooz.-.. 7

Raney v. Board of Education of Gould, Arkansas, 391

U.S. 443 (1963)... 9,15, 22 23, 24 25,28

Springfield School Committee v. Barksdale, 348 F.2d

3681... WIE I Ee LE 12

USA. vv. Jejjerson, 3B0:F.2d 305 ........coomnensiseeserneensorcess 1,723

United States v. Board of Ed. Polk County, 395 F.2d

SLE EE ei ee CR i 27

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

OCTOBER TERM, 1969

No. 632

BEATRICE ALEXANDER, et als.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants-Petitioners,

VS.

HOLMES COUNTY BOARD OF EDUCATION, et als.,

Defendants-Appellees-Respondents.

JOAN ANDERSON, et als.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants-Petitioners,

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Intervenor-Appellant-Respondent,

VS.

CANTON MUNICIPAL SCHOOL DISTRICT, et als., and

MADISON COUNTY SCHOOL DISTRICT, et als.,

Defendants-Appellees-Respondents.

ROY LEE HARRIS, et als.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants-Petitioners,

VS,

YAZOO COUNTY BOARD OF EDUCATION, et als,

Defendants-Appellees-Respondents.

JOHN BARNHARDT, et als.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants-Petitioners,

VS.

MERIDIAN SEPARATE SCHOOL DISTRICT, et als,

Defendants-Appellees-Respondents.

DIAN HUDSON, et als,

Plaintiffs-Appellants-Petitioners,

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Intervenor-Appellant-Respondent,

; vs.

LEAKE COUNTY SCHOOL BOARD, et als.,

Defendants-Appellees-Respondents.

JEREMIAH BLACKWELL, JR. et als,

Plaintiffs-Appellants-Petitioners,

ISSAQUENA COUNTY BOARD OF EDUCATION, et als.,

Defendants-Appellees-Respondents.

CHARLES KILLINGSWORTH, et als.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants-Petitioners,

As hand au

ENTERPRISE CONSOLIDATED SCHOOL DISTRICT and

QUITMAN CONSOLIDATED SCHOOL DISTRICT,

Defendants-Appellees-Respondents.

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Plaintiff-Appellant-Respondent,

GEORGE MAGEE, JR,

Intervenor-Petitioner,

VS.

NORTH PIKE COUNTY CONSOLIDATED SCHOOL

DISTRICT, et ole.

Defendants-Appellees-Respondents.

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Plaintiff-Appellant-Respondent,

GEORGE WILLIAMS, et als.,

Intervenors-Petitioners,

VS.

WILKINSON COUNTY SCHOOL DISTRICT, et als.,

Defendants-Appellees-Respondents.

PETITION FOR REHEARING AND, IN THE

ALTERNATIVE, CLARIFICATION

OF MANDATE

PRELIMINARY STATEMENT

In accordance with the provisions of Rule 58 of the

Rules of this Court, the respondents filed this petition for

rehearing and, in the alternative, for clarification of the

Per Curiam mandate rendered in the above styled consoli-

dated causes on October 29, 1969, state the grounds for such

belief as hereinafter set forth.

I.

The Respondents Have Not Been Accorded Due Process

of Law. There Has Been No Hearing on the Merits by

Any Court nor Any Opportunity for the Litigants to

Be Heard on the Merits Through Their Attorneys.

The nine cases consolidated for the purposes of the

petition for writ of certiorari are a portion of the twenty-

five cases consolidated under Docket Nos. 28,030 and

28,042 by the Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit. The

opinion therein was rendered July 3, 1969, and appears

as U.S.A. et als., v. Hinds County, et als., not yet reported.

As was found in such opinion, all of these school districts

had been operating for a number of years under a Jef-

ferson type decree which provided a freedom of choice

plan as authorized and delineated in Jefferson II. U.S.A. v.

Jefferson, 380 F.2d 385.

The Per Curiam mandate dated October 29, 1969,

after requiring that the school systems here involved

2

should not operate as dual school systems based on race

but should “begin immediately to operate as unitary school

systems within which no person is to be effectively ex-

cluded from any school because of race or color”, provided

as follows:

The Court of Appeals may in its discretion direct the

schools here involved to accept all or any part of the

August 11, 1969, recommendations of the Department

of Health, Education, and Welfare, with any modifica-

tions which that court deems proper insofar as those

recommendations insure a totally unitary school sys-

tem for all eligible pupils without regard to race or

color.

The Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit has now

acted under the circumstances hereinafter fully detailed.

It has substituted for all of the Jefferson type decrees pro-

viding for freedom of choice and has rendered a decree,

the nature of this decree will be hereinafter described. At-

tached to this decree are the thirty HEW plans filed on

August 11, 1969. With the very minor exceptions detailed

in the decree, these are put in full force and effect in every

particular. The Court did not permit the alternate step

procedure (referred to in many plans as “interim steps”)

to be utilized.

On October 29 the Per Curiam opinion of the Supreme

Court was rendered. Copies thereof were received by at-

torneys for the defendants on or about Friday, October 31,

and Saturday, November 1.

On Friday, October 31, the Court of Appeals issued its

order directing all parties to all twenty-five suits to file

with the Clerk of that Court on or before Wednesday,

November 5, their recommended and proposed orders to ef-

fectuate and implement the opinion and decree of this Court.

Such order was received bythe attorneys for the parties

in due course of the mails, a few being orally notified.

3

The order of the Court of Appeals issued on Friday,

October 31, contained the following directions:

Appellants, appellees and the United States of Amer-

ica as amicus or intervenor shall file with the Clerk

of this Court on or before the fifth day of November,

1969, their recommended and proposed orders which

will properly effectuate and implement the opinion

and decree of the Supreme Court of the United States

rendered on October 29, 1969, in the above named

cases.

On Monday, November 3, attorneys for the defend-

ants were advised by telephone and otherwise to be pres-

ent in New Orleans before the Court of Appeals at 1:00

P.M. on Thursday, November 6, to attend a pre-order con-

ference, and to have the superintendents of the school dis-

tricts present at that time.

On Wednesday, November 5, the various districts

filed their proposed orders embodying plans which had

been very hastily prepared and revised over the week end,

these being in the hands of the Court for from twenty-

four to thirty-six hours prior to the “pre-order conference”

held at 1:00 P.M. on Thursday, November 6. In the mean-

while, the attorneys for the private plaintiffs had sent

to the Court copies of the several plans of desegregation

filed by HEW on August 11. Hence a very few hours was

consumed by the Court of Appeals in a comparison of these

plans.

The oral notification to attorneys for the school dis-

tricts to be present at the “pre-order conference” on No-

vember 6 included a statement that no arguments would

be received on that date but there would only be a dis-

cussion of the order. The transcript of the proceedings on

that date includes the following description of what oc-

curred at the “pre-order conference’:

4

(Page references are to the transcript.)

(p. 2) Ladies and gentlemen, we have called this

pre-order conference today for the purpose of making

some announcements and also to exchange views. Af-

ter we make some statements, we want everyone to

feel free to ask questions. We don’t intend to have

any legal arguments, as such, but we do think it would

be well for anyone that has questions, that you feel

free to make such inquiries as you may have. . . .

(p. 3) We have also studied the Supreme Court de-

cision in these cases and we are of the view that ac-

tion is required, and immediate action. . ..

(p. 5) We have prepared a draft order, it is not a

final Order. We hope to put the Order out tomorrow.

We did not want to put an order out until we had this

conference and we want to tell you generally what is

in the order now so that you will be advised as to

what questions you may wish to pose.

(p. 6) Now, we are going on then, and we say to ef-

fectuate the conversion of these school systems to

unitary school systems within the context of the Su-

preme Court order the following things have to be

done, and then generally we are putting into effect in

every case, except the ones I will tell you about, the

recommended plan of the Office of Education, HEW.

And that is a permanent plan and not the interim

plan.

In accordance with the announcement and require-

ment of the Court, no argument was presented by any of

the attorneys. No briefs on the merits were prepared

within the three business days involved nor permitted to

be filed by the Court. No hearing of any kind was had in

the Court of Appeals at this or any other time, concerning

the judgments proposed to be entered and the specific,

clear, detailed, and revoluntionary provisions thereof, em-

bodied therein through attachment of the plans filed by

HEW on August 11.

5

Never in the history of jurisprudence in the United

States has the fundamental concept of due process of law

been so flagrantly violated. The following has occurred:

1. The original judgment of the Court of Appeals of

July 3 set up a procedure whereby hearings would be had

and due process of law completed.

2. The amendatory order of August 28, 1969, entered

by the Court of Appeals also set up a procedure whereby

hearings would be had and due process of law completed.

3. The mandate of the Supreme Court of October 29,

1969, provided:

The Court of Appeals may make its determination and

enter its order without further arguments or submis-

sions.

4. The Court of Appeals having elected to prohibit all

attorneys from presenting either briefs or oral arguments

on the merits and not to consider any evidence before a

Master or otherwise, due process of law was never accorded

to either the United States as plaintiff or intervenor in

twenty of these suits, nor to the school districts as defend-

ants in twenty-five of these suits. (The Court of Appeals

applied the mandate of this Court to all twenty-five consoli-

dated cases.)

Every citizen of the United States is protected by the

constitutional guarantee of due process of law. This is

fundamental and has always been one of the basic concepts

of our system of justice. One of the early statements of

this fundamental constitutional right, which lives today

for the protection of every citizen, was made by this Court

through Justice White in Hovey v. Elliott, 167 U.S. 409,

42 L.Ed. 415, as follows:

The fundamental conception of a court of justice is

condemnation only after hearing. To say that courts

6

have inherent power to deny all right to defend an ac-

tion and to render decrees without any hearing what-

ever is, in the very nature of things, to convert the

court exercising such an authority into an instrument

of wrong and oppression, and hence to strip it of that

attribute of justice upon which the exercise of judicial

power necessarily depends. . .

In Golpin v. Page, 835 US, ........ . 18 Wall, 350 [21:0591,

the court said (p. 368 (963) ):

“It is a rule as old as the law, and never more to

be respected than now, that no one shall be personally

bound until he has had his day in court, by which is

meant, until he has been duly cited to appear, and has

been afforded an opportunity to be heard. Judgment

without such citation and opportunity wants all the

attributes of a judicial determination; it is judicial

usurpation and oppression, and can mever be upheld

where justice is justly administered.”

Again, in Ex parte Wall, 107 U.S. 239 [27.582], the

court quoted with approval the observations as to “due

process of law” made by Judge Cooley, in his Constitu-

tional Limitations, at page 353, where he says:

“Perhaps no definition is more often quoted than

that given by Mr. Webster in the Dartmouth College

Coase, 17US..... , 4 Wheat. 518 [4:629]: ‘By the law of

the land is most clearly intended in the general law;

a law which hears before it condemns, which proceeds

upon inquiry and renders judgments only after trial.

The meaning is that every citizen shall hold his life,

liberty, property, and immunities under the protection

of the general rules which govern society.” ”

In Morgan v. United States of America, 304 U.S. 13, 82

L.Ed. 1129, this Court said through Chief Justice Charles

Evans Hughes:

The right to a hearing embraces not only the right

to present evidence but also a reasonable opportunity

7

to know the claims of the opposing party and to meet

them. The right to submit argument implies that op-

portunity; otherwise the right may be but a barren

one.

Here, there has never been an opportunity for evidence

to be introduced, there has been no opportunity whatso-

ever for the parties to be heard by their attorneys, in the

District Court, in the Court of Appeals or in the Supreme

Court of the United States as to any matter pertaining to

the merits of the judgment which has been entered. The

present judgment sets aside each judgment under which

each of these school districts had been operating for a num-

ber of years, a judgment theretofore approved by the Court

of Appeals of the Fifth Circuit in Jefferson II. It has de-

stroyed in every district freedom of choice. It has re-

quired compulsory integration of every faculty and staff to

the racial balance existing in the entire system. It will

require compulsory assignment of students by use of pair-

ing, racial zoning or direct assignment. In most instances

this will also approach a racial balance and in every in-

stance it is designed to and will very materially remove

existing racial imbalance. This action falls squarely with-

in the rules announced by this Court in Powell v. Ala-

bama, 287 U.S. 45, 77 L.Ed. 158, in which this Court said:

... The words of Webster, so often quoted, that by “the

law of the land” is intended “a law which hears before

it condemns,” have been repeated in varying forms of

expression in a multitude of decisions. In Holden wv.

Hardy, 169 U.S. 366, 389, 42 1..Ed. 780, 790, 18 S.Ct.

383, the necessity of due notice and an opportunity oy

being heard is described as among the “immutable

principles of justice which inhere in the very idea of

free government which no member of the Union may

disregard.”

And Mr. Justice Field, in an earlier case, Galpin v.

Page, 18 Wall. 350, 368, 369, 21 L.Ed. 959, 963, 964,

8

said that the rule that no one shall be personally

bound until he has had his day in court was as old

as the law, and it meant that he must be cited to

appear and afforded an opportunity to be heard. “Judg-

ment without such citation and opportunity wants all

the attributes of a judicial determination; it is judicial

usurpation and oppression, and mever can be upheld

where justice is justly administered.”

This Court is not now considering actions taken on or

prior to July 3, 1969. There has been mo hearing on the

merits upon any plan of desegregation embodied in the

judgments entered on November 7. Moreover, no court

has permitted the plaintiff, the United States of America,

or the defendants in these cases to be heard on the merits

by brief or otherwise. Not one iota of testimony has been

permitted before any court upon any portion of the judg-

ments and plans now put into effect.

11.

The Judgment Now Entered by the Court of Appeals

Conflicts with Decisions of the Courts of Appeal of

Other Circuits.

The judgment entered here results in complete de-

struction of freedom of choice plans being based upon dicta

first appearing in Adams: *

If in a school district there are still all-Negro schools,

or only a small fraction of Negroes enrolled in white

schools, or no substantial integration of faculties and

school activities then, as a matter of law, the existing

plan fails to meet constitutional standards as estab-

lished in Green.

It appears that the entry of this judgment also arises

from a misunderstanding of what constitutes a dual system

1. Adams v. Mathews, 403 F.2d 181 (5th Cir. 1968).

9

of schools and a misunderstanding of the clause “a unitary

nondiscriminatory school system”.

Through a misconstruction of the “trilogy of cases”,

Green, Monroe and Raney, this panel of the Court of Ap-

peals now finds itself in direct conflict with decisions of

other circuits. The panel in Adams had before it a docket

setting only. Yet, it seized upon numerous elements

which were considered in combination and separated then,

so that each separate element is now made the sine qua

non of continuance of freedom of choice. This is also true

in the varying definitions of what constitute the “vestiges

of a dual school system” that must be removed.

The Court of Appeals of the Sixth Circuit determined

on February 10, 1969, in Goss v. Board of Education of

Knoxville, Tennessee, 406 F.2d 1183, that the elimination

of all-Negro and all-white schools is not a condition pre-

cedent to either the establishment of a unitary, nonracial

school system, or to the continuation of a freedom of

choice plan of desegregation. In the Knoxville system

there were five all-Negro schools and twenty-nine schools

having faculties of only one race. It also found that in

1960 the district had “a school system completely and de

jure segregated both as to students and faculty”. In

holding that the Knoxville school system was constitu-

tionally acceptable, the Court of Appeals said:

Preliminarily answering question I, it will be sufficient

to say that the fact that there are in Knoxville some

schools which are attended exclusively or predomi-

nantly by Negroes does mot by itself establish that

the defendant Board of Education is violating the

constitutional rights of the school children of Knox-

ville. Deal v. Cincinnati Bd. of Education, 369 F.2d

55 (6th Cir. 1966), cert. denied, 389 U.S. 847, 88 S.Ct.

39, 19 LLEd.2d 114 (1967); Mapp v. Bd. of Education,

373 F.2d 75, 78 (6th Cir. 1967). Neither does the fact

10

that the faculties of some of the schools are exclu-

sively Negro prove, by itself, violation of Brown.

The Court then discussed the rule set forth in Green,

including in the statement that the school boards are

“charged with the affirmative duty to take whatever

steps might be necessary to convert to a unitary system

in which racial discrimination would be eliminated root

and branch”. In applying this to the Knoxville District

and discussing its effect, the Court of Appeals of the Sixth

Circuit said:

The Court further said that it would be their duty

“to convert to a unitary system in which racial dis-

crimination would be eliminated root and branch.”

391 U.S. at 437-438, 88 S.Ct. at 1694. We are not sure

that we clearly understand the precise intendment of

the phrase “a unitary system in which racial dis-

crimination would be eliminated,” but express our

belief that Knoxville has a unitary system designed

to eliminate racial discrimination.

The Court brushed aside the position that different

constitutional principles should be applied to southern

states where there had been in the past de jure segrega-

tion as contrasted to northern states where there had been

in the past de facto segregation. This was of particular

importance as Deal involved formerly de facto segregation

and Goss involved formerly de jure segregation. The

Court said:

In Monroe v. Bd. of Commissioners, 380 F.2d 955, 958

(6th Cir. 1967), we expressed our view that the end

product of obedience to Brown I and II need mot be

different in the southern states, where there had been

de jure segregation, from that in morthern states in

which de facto discrimination was a fortuity. Our

observations in that regard were not found invalid

by the Supreme Court’s opinion reversing our Monroe

13

decision. See Monroe v. Board of Commissioners, 391

U.S. 450, 83 S.Ct. 1700, 20 1.Ed.2d 733 (1963).

The constitutional principles thus found to be applica-

ble to both southern states and northern states were

stated by the Sixth Circuit in Deal, cited as supporting

authority in Goss. Deal involved the Cincinnati school

system in which de facto segregation had resulted in

heavy racial imbalance in the schools.? Racial discrimina-

tion may be removed by different methods, including

freedom of choice plans, validly set up, properly admin-

istered, with choices freely exercised without external

pressures so that the plan itself (without regard to the

statistical results produced by choices thereunder) is

constitutionally acceptable. Adams and Hinds County

are actually bottomed solely upon statistics and are in

direct conflict with both Goss and Deal. In Deal the

Sixth Circuit said:

The cases recognize that the calculus of equality is

not limited to the single factor of “balanced schools”;

rather, freedom of choice under the Fourteenth

Amendment is a function of many variables which

may be manipulated differently to achieve the same

result in different contexts. . . .

This is in accord with our holding that bare statistical

imbalance alone is mot forbidden. There must also

be present a quantum of official discrimination in

order to invoke the protection of the Fourteenth

Amendment. . . .

2. The report of the Cincinnati school system to HEW for the

school year 1968 revealed that of the 106 schools in the Cincinnati

Public School System, forty were composed of students of one

race (i.e., more than 99 per cent Negro or 99 per cent white

students), of which thirteen schools were Negro and twenty-

seven schools were white.

12

Finally, in the one case in which a district court ap-

parently accepted the appellants’ theory of racial

imbalance, Barksdale v. Springfield School Comm.,

237 F.Supp. 543 (D.Mass. 1965), the first Circuit, in

vacating the decision and dismissing the complaint

without prejudice specifically rejected any such as-

serted constitutional right. Springfield School Comm.

v.. Barksdale, 348 B2d 261, 264 (1st Cir. 1965).

Adams and its progeny, including Hinds County, are

in direct conflict with Springfield School Committee v.

Barksdale, 348 F.2d 361, rendered by the Court of Appeals

of the First Circuit in 1965. The district court found that

two of the elementary schools had over 80 percent Negro

pupils, that fourteen elementary schools had no Negro

pupils or less than one per cent Negro pupils, and that

the school system was racially imbalanced. The Court of

Appeals said:

Having reached its conclusions, the court ordered the

defendants to submit a plan to correct racial im-

balance in the Springfield schools.

The Court vacated the order of the district court and

reversed, stating the constitutional principles as follows:

Certain statements in the opinion, notably that

“there must be no segregated schools,” suggest an ab-

solute right in the plaintiffs to have what the court

found to be “tantamount to segregation” removed at

all costs. We can accept no such constitutional right.

C1. Bell v. School City of Gary, 7 Cir., 1963,:324 F.24

209, cert. den. 377 U.S. 924, 84 S.Ct. 1223, 12 L.Ed.24

216; Downs v. Board of Education, 10 Cir., 1945, 336

F.2d 988, cert. den. 380 U.S. 914, 85 S.Ct. 898, 13 L.Ed.2d

300.5.

But more fundamentally, when the goal is to equalize

educational opportunity for all students, it would be

no better to consider the Negro’s special interests

13

exclusively than it would be to disregard them com-

pletely.

The hard and fast Adams rule, the statistically-based

Hinds County decision, and like decisions conflict with

United States v. Cook County, 404 F.2d 1125, 1135, decided

by the Court of Appeals of the Seventh Circuit on De-

cember 17, 1968. The panels of this Circuit have brushed

aside good faith. They require hard and fast statistical

results now. To the contrary, the Court said in Cook

County:

There is no hard and fast rule that tells at what

point desegregation of a segregated district or school

occurs. The court in Northcross said the “minimal

requirements for non-racial schools are geographic

zoning, according to the capacity and facilities of the

buildings and admission to a school according to

residence as a matter of right.” 333 F.2d at 662.

On the other hand, “The law does not require a

maximum of racial mixing or striking a rational

balance accurately reflecting the racial composition

of the community or the school population.” United

States v. Jefferson County Board, 372 F.2d 836, 847,

n. 5 (5th Cir. 1966) oif'd en bane, 330 F.2d 385

(5th Cir.), cert. denied, Cado Parish School Board

vy, United States, 389 U.S. 840, 83 5.Ct. 67, 19 L.Ed.2d

103 (1967).

By the entry of this judgment there arises a conflict

with the opinion of the United States Court of Appeals

for the Tenth Circuit in Downs v. Board of Education

of Kansas City, 336 F.2d 988 (1964), cert. denied 380

U.S. 914, 35 S.Ct 898,.13 1.¥d.2d :.300..(19865). : This

involved the public schools of the Kansas City,

Kansas, school system, which was operated on a

segregated basis prior to Brown I. Thereafter the schools

were integrated based chiefly upon zones and neighbor-

14

hood school systems including the right of transfer. The

Court held:

There is. to be sure, a racial imbalance in the public

schools of Kansas City. . . .

Appellants also contend that even though the Board

may not be pursuing a policy of intentional

seosregation, there is still segregation in fact in the

school svstem and under the principles of Brown

v. Board of Education, supra, the Board has a

positive and affirmative duty to eliminate segrega-

tion in fact as well as segregation by intention.

While there seems to be authority to support that

contention, the better rule is that although the

Fourteenth Amendment prohibits segregation, it does

not command integration of the races in the public

schools and Negro children have mo constitutional

right to have white children attend school with

them. (Citing authorities).

See also Mapp v. Board of Education of Chattanooga,

Tennessee, 373 F.2d 75, rendered by the United States

Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit. This involved a

school system in which de jure segregation continued until

it was removed by a grade-to-grade extension of a freedom

of choice plan resulting in “full integration of all grades in

September 1966”. In response to an attack upon the plan

by the plaintiffs, the Court upheld the plan and said:

To the extent that plaintiffs’ contention is based on

the assumption that the School Board is under a con-

stitutional duty to balance the races in the school sys-

tem in conformity with some mathematical formula,

it is in conflict with our recent decision in Deal wv.

Cincinnati Board of Education, 369 F.2d 55 (6th Cir.

1966).

15

1M.

The Constitutional Duty to Remove Vestiges of the

Dual System of Public Schools Does Not Require the

Entry of These Judgments.

The Court of Appeals has construed the Per Curiam

order as either overruling or substantially modifying Green,

Raney and Monroe. It has also construed such order to

require entry of judgments resulting in compulsory integra-

tion of students and faculty and the elimination of all fre-

dom of choice. Confusion has arisen from the various in-

terpretations of the duty of school boards articulated in

Green:

School boards such as the respondent then operating

state-compelled dual systems were nevertheless

clearly charged with the affirmative duty to take

whatever steps might be necessary to convert to a

unitary system in which racial discrimination would be

eliminated root and branch. See Cooper v. Aaron, su-

pra, at 7, 3 L.Ed.2d at 10; Bradley v. School Board,

33217.8. 103, 15 1.E4d.2d 137, 86 S.Ct. 224: cf. Watson

v. City of Memphis, 373 U.S. 526, 10 1.Ed.2d 529, 33

S.Ct. 1314. The constitutional rights of Negro school

children articulated in Brown I permit no less than

this; and it was to this end that Brown II commanded

school boards to bend their efforts. . . . Note. “We

bear in mind that the court has not merely the power

but the duty to render a decree which will so far as

possible eliminate the discriminatory effects of the

past as well as bar like discrimination in the future.”

Louisiana v. United States, 380 U.S. 145, 154, 13 L.Ed.

2d 709, 715, 85 S.Ct. 817.

Although the passage of time now requires more real-

istic results and more comprehensive steps without further

delay, the basic constitutional principles originally an-

nounced in Brown I have not been changed in the succeed-

16

ing pronouncements by the Supreme Court up to and in-

cluding Carr?

Monroe v. Board of Commissioners of the City of

Jackson, Tennessee, 380 F.2d 955 (6th Cir.), involved

a formerly racially segregated de jure school sys-

tem. Because of its significance here and its direct con-

flict with these judgments, we quote from such decisions:

Appellants argue that the courts must now, by recon-

sidering the implications of the Brown v. Board of Edu-

cation decisions in 347 U.S. 483, 74 S.Ct. 686, 98 L.Ed.

873 (1954) and 349 U.S. 294, 75 S.Ct. 753, 99 L.Ed. 1033

(1955), and upon their own evaluation of the com-

mands of the Fourteenth Amendment, require school

authorities to take affirmative steps to eradicate that

racial imbalance in their schools which is the product

of the residential pattern of the Negro and white

neighborhoods. The District Judge’s opinion discusses

pertinent authorities and concludes that the Fourteenth

Amendment did not command compulsory integration

of all of the schools regardless of an honestly composed

unitary neighborhood system and a freedom of choice

plan. We agree with his conclusion. ... He concluded

“We read Brown as prohibiting only enforced segre-

gation.” 369 F.2d at 60. We are at once aware that

we were there dealing with the Cincinnati schools

which had been desegregated long before Brown,

whereas we consider here Tennessee schools desegre-

gated only after and in obedience to Brown. We are

not persuaded, however, that we should devise a math-

ematical rule that will impose a different and more

stringent duty upon states which, prior to Brown,

maintained a de jure biracial school system, than upon

those in which the racial imbalance in its schools has

come about from so-called de facto segregation—this

to be true even though the current problem be the same

in each state.

3. Carr v. Montgomery County, 23 1. Ed.2d 263.

17

However ugly and evil the biracial school systems ap-

pear in contemporary thinking, they were, as Jeffer-

son, supra, concedes, de jure and were once found law-

ful in Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S, 537, 16 S.Ct. 1138,

41 L.Ed. 256 (1896), and such was the law for 58 years

thereafter. To apply a disparate rule because these

early systems are now forbidden by Brown would be

in the nature of imposing a judicial Bill of Attainder.

Such proscriptions are forbidden to the legislatures of

the states and the nation—U.S. Const. Art. I, Section

9, Clause 3 and Section 10, Clause 1. Neither, in our

view, would such decrees comport with our current

views of equal treatment before the law.

A writ of certiorari was granted by the Supreme Court

in this case and the decision appears as Monroe. The sole

issue in that case was the constitutionality of a “free trans-

fer” provision in the plan of desegregation. The same suit

again came before the Court of Appeals of the Sixth Cir-

cuit on February 10, 1969, as Goss. The Court construed

the holding of the Supreme Court in Monroe as follows:

In Monroe v. Bd. of Commissioners, 380 F.2d 955, 159

(6th Cir. 1967), we expressed our view that the end

product of obedience to Brown I and II need not be

different in the southern states, where there had been

de jure segregation, from that in morthern states in

which de facto discrimination was a fortuity. Our ob-

servations in that regard were mot found invalid by

the Supreme Court’s opinion reversing our Monroe de-

cision. See Monroe v. Board of Commissioners, 391

U.S. 450, 88 S.Ct. 1700, 20 L.Ed.2d 733 (1968).

When Cooper again reached the Court of Appeals of

the Eighth Circuit the opinion was rendered as Clark v.

Board of Education of Little Rock School District, 369 F.2d

661, rehearing denied, 374 F.2d 569. The Court delineated

a school system and its operation which falls within the

constitutional mandate of the Supreme Court as follows:

18

The Constitution prohibits segregation of the races, the

operation of a school system with dual attendance

zones based upon race, and assignment of students on

the basis of race to particular schools. If all of the

students are, in fact, given a free and unhindered

choice of schools, which is honored by the school board,

it cannot be said that the state is segregating the

races, operating a school with dual attendance areas

or considering race in the assignment of students to

their classrooms. We find no unlawful discrimination

in the giving of students a free choice of schools.

The school system of Little Rock had been a dual seg-

regated school system. Hence, the decisions of the Eighth

Circuit in Clark as well as the decision in Goss (both con-

sidering formerly de jure segregated systems) are directly

applicable to this judgment.

The rule applied in Clark to the Little Rock school sys-

tem is certainly applicable to the thirty districts here:

Though the Board has a positive duty to initiate a plan

of desegregation, the constitutionality of that plan does

not necessarily depend upon favorable statistics indi-

cating positive integration of the races. ... The sys-

tem is not subject to constitutional objections simply

because large segments of whites and Negroes choose

to continue attending their familiar schools. It is true

that statistics on actual integration may tend to prove

that an otherwise constitutional system is not being

constitutionally operated. However, these statistics

certainly do not conclusively prove the unconstitution-

ality of the system itself. . ..

In short, the Constitution does mot require a school

system to force a mixing of the races in school accord-

ing to some predetermined mathematical formula.

Therefore, the mere presence of statistics indicating

absence of total integration does not render an other-

wise proper plan unconstitutional.

19

The initial step to determine what are vestiges of a

racially discriminatory dual school system (in which sep-

aration of the races has been de jure) as distinguished

from racially nondiscriminatory unitary school systems

(in which separation of the races has been de facto) is to

eliminate those elements common to both.

Compilations before the Court of Appeals were as-

sembled from the statistical information filed with the

Department of Health, Education and Welfare and show

the racial composition of schools in the one hundred largest

school districts in this nation as of October 15, 1968. They

were filed by school districts under the requirements of

Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and are upon Civil

Rights Forms OS/CR 102-1 and OS/CR 101. Most of these

districts have never had a dual system.

Assuming that a school with less than one percent of

the minority race is an all-white or all-Negro school, of the

12,497 schools in the one hundred largest school districts in

the United States 6,137 schools are either all-white or all-

Negro. Thus, more than forty-eight percent of the schools

in these districts are either all-white or all-Negro. It is

also found that in districts having as much as twenty per-

cent or more Negro student enrollment, only one district

does not have within it all-Negro schools. This is the

Rochester, New York, Monroe County School District. In

the consolidated cases at bar only one of the thirty districts

has less than twenty percent Negro student enrollment.

These facts cannot be a “vestige of the dual system of

schools” but resulted from the natural process of education

in a unitary, non-racial school system:

20

Schools

with

Faculty Schools

Total of of All-

Schools One One Negro

District in Dist. Race Race Schcols

Chicago Public Schools,

Chicago, Ill. 610 236 392 208

Indianapolis Public Schs.,

Indiana 119 L 52 17

Des Moines Community A

Schs., Iowa 81 52 36 _.

Boston School Dept.,

Massachusetts 196 108 56 11

Detroit Public Schools,

Michigan 302 10 98 67

Special School Dist. No. 1,

Minneapolis, Minn. 98 52 42 na

St. Louis City Sch. Dist.,

Mo. 164 81 114 83

Kansas City School Dist.,

Mo. 99 14 43 19

Newark Public Schools

Newark, N. J. 80 1 2 27

Oklahoma City Public Sch.

Dist., I-89, Okla. 115 5 71 15

Dallas Indep. Sch. Dist.,

Texas 173 149 117 26

Los Angeles School Dist.,

Calif. 591 229 359 65

Sch. Dist: No.''1, City

& Co. of Denver, Colo. 116 32 54 3

District of Columbia

Public Schools 188 26 114 114

Gary Community Schools,

Cary, Ind. 45 6 25 21

Cleveland, Ohio,

Cuyahoga Co. 180 38 115 57

21

New York City Public Schs.

NY; N.Y. 853 221 158 113

Houston Indep. Schools,

Houston, Texas 225 9 139 61

School Dist. of

Philadelphia, Pa. 278 3 37 63

Broussard* approved the Houston Independent School

District as being in compliance with constitutional re-

quirements under a freedom of choice plan. According to

its official report as of October 15, 1968, there then re-

mained sixty-one all-Negro schools, seventy-eight all-white

schools, and there were eighty-six desegregated schools.

It is clear that the following do not constitute vestiges

of a de jure racially discriminatory dual school system:

(1) All-Negro schools and all-white schools, identi-

fiable as being attended by students of only one race or by

students predominantly of one race.

(2) Schools being served by faculty and staff com-

posed of members of one race or composed predominantly

of members of one race.

(3) Schools in which the number of students of the

two races do not materially vary from year to year, i.e,

in which statistics do not demonstrate that the number of

Negro students is increasing in a school attended pre-

dominantly by white students or in which Negro teachers

are not increasing where the faculty is composed pre-

dominantly of members of the white race.

We respectfully submit that the entry of these judg-

ments was the result of a misconstruction of the Per

Curiam order dated October 29, 1969. It is clear that the

Court of Appeals believed it had been expressly directed

4. Broussard v. Houston Ind. School District, 395 F.2d 817.

22

to enter the judgments now in effect. A clarification of

the mandate removing this belief would permit the Court

of Appeals to enter judgments in accordance with Green,

Monroe, Raney and Carr and other applicable decisions of

this court. The entry of proper judgments within the scope

of such decisions and what we believe to be the meaning

of the Per Curiam order would remove the above conflicts

with other Circuits.

ky.

The HEW Plans, with the Inclusion of the Alternative

or “Interim” Steps in Student and Faculty Integration,

Would Put into Immediate Effect Unitary Racially

Non-Discriminatory School Systems.

The HEW plans of August 11, 1969 all included a two-

step procedure. As to students, the first step (in most of

the plans called an “interim” step) will result in substantial

integration of students and faculty. These alternative or

initial steps modify the freedom of choice plans in various

ways including pairing of grades, closing of schools, zoning

to bring about fixed student attendance patterns, etc. They

generally required faculty integration to the extent of one-

half of the ultimate requirement.

When the Per Curiam opinion is construed in the con-

text of previous decisions of this Court its description of

a unitary school system is clear. The mandate would re-

quire the Court of Appeals to enter an order as to the

school districts:

. . . directing that they begin immediately to op-

erate as unitary school systems within which mo

person should have to be effectively excluded from

any school because of race or color.

23

The key is the removal of all discrimination, in com-

pulsory and complete integration attained by various

forms of mandatory asignment of students.

It does not seem to have been generally recognized

that the Supreme Court of the United States in Green,

Raney, Monroe and Carr not only failed to place its stamp

of approval upon Jefferson II, but affirmatively declined

to hold that the Fourteenth Amendment requires com-

pulsory integration in public schools. These cases clearly

and unmistakably describe the school system which meets

all constitutional guarantees.

The key is complete and immediate removal of racial

discrimination, and not complete compulsory integration

of students through mandatory assignment of students by

various means.

In Green such system is described as: “A racially

nondiscriminatory school system”—“a unitary, nonracial

system of public education” —*a unitary system in which

racial discrimination would be eliminated root and branch.”

In Raney such system is described as: “A wunitary,

nonracial school system”.

In Monroe such school system is described as: “A

racially non-discriminatory system”—"“a unitary system in

which racial discrimination would be eliminated root and

branch”—“a system without a ‘white’ school and a ‘Negro’

school, just schools”.

In Carr such school system is described as: “A sys-

tem of public education free of racial discrimination”—"“a

completely unified unitary nondiscriminatory school sys-

tem”—*“a racially nondiscriminatory school system”.

The Supreme Court affirmatively declined to hold in

Green that the Fourteenth Amendment requires ‘“com-

pulsory integration”, saying:

24

The Board attempts to cast the issue in its broadest

form by arguing that its “freedom-of-choice” plan may

be faulted only by reading the Fourteenth Amendment

as universally requiring “compulsory integration”, a

reading it insists the wording of the Amendment will

not support. But that argument ignores the thrust of

Brown II. In the light of the command of that case,

what is involved here is the question whether the

Board has achieved the “racially mon-discriminatory

school system” Brown II held must be effectuated in

order to remedy the established unconstitutional de-

ficiencies of its segregated system.

The Adams dicta upon which these judgments are

based arose through the consideration of one paragraph,

one sentence or even a portion of one sentence in Green,

Raney, or Monroe. A study of these opinions as a whole

(supplemented by Carr) reveal the fallacy of the reasoning

upon which the Adams dicta was based. The panels of

this Court have failed to follow the teachings of these

cases. It is only by a consideration of the many complex

factors entering into the educational process and par-

ticularly into the desegregation of a formerly de jure

and formerly de facto segregated schools, that we are able

to chart the course which is in the best interest of the

students and of our public schools. This was the objec-

tive stated by Mr. Justice Black in Carr.

In Green the Supreme Court found that the school sys-

tem of New Kent County was a dual school system and

described such system as follows:

. . . Racial identification of the system’s schools was

complete, extending not just to the composition of

student bodies at the two schools but to every facet of

school operations—faculty, staff, transportation, ex-

tracurricular activities and facilities.

25

In Green, Raney and Monroe there was considered

many of the factors which, when taken as a whole and in

combination, should be utilized in determining the applica-

tion of the following test:

Where the Court finds the board to be acting in good

faith and the proposed plan to have real prospects of

dismantling the state-imposed dual system ‘at the

earliest practicable date” then the plan may be said

to provide effective relief. . . . Moreover, whatever

plan is adopted will require evaluation in practice. . . .

The elements elucidated in these cases included:

1.

11

12.

Every facet of school operations;

. Faculty, staff and student body;

. Transportation and construction of new buildings;

2

3

4.

5}

6

7

Extracurricular activities and facilities;

. Majority to minority transfer;

. Method of exercising the freedom of choice;

. Assignment of students who did not exercise the

freedom of choice;

. Whether or not the “public school facilities for

Negro pupils (were) inferior to those provided for

white pupils”;

. Operation of the freedom of choice plan “in a con-

stitutionally permissible fashion”;

. “All aspects of school life including faculties and

staffs’;

Whether “the board had indeed administered the

plan in a discriminatory fashion”;

The comparative treatment of students attempting

“to transfer from their all-Negro zone schools to

schools where white students were in the ma-

jority’;

26

13. The comparative treatment of “white students

seeking transfers from Negro schools to white

schools”;

14. Whether “the transfer (provision) lends itself to

perpetuation of segregation”.

Within the broad statements of Green fall the follow-

ing additional phases of a school system:

15. Athletic activities within the schools;

16. Parent-teacher associations;

17. Faculty and staff meetings within schools and of

faculties and staffs of the various schools at the

elementary, junior high school and high school

levels;

18. School-sponsored visitation of student body of-

ficers and student committees;

19. In-service training of teachers and staff to assist

in the desegregation process;

20. Participation by students in various types of stu-

dent organizations.

Yet under the Adams dicta, upon which this judg-

ment is based (thereafter quoted by several panels) any

one of the following factors standing alone will outlaw

freedom of choice and require compulsory integration by

mandatory student assignment (racial zoning or racial in-

dividual assignments).

If there is an all-Negro school in the district freedom

of choice is “impermissible”; or

If “only a small fraction of Negroes [have] enrolled

in white schools” freedom of choice is impermissible; or

If “no substantial integration of faculties and school

activities” has been attained, freedom of choice is imper-

missible.

27

On April 18, 1968, it was held in United States v. Board

of Ed. Polk County, 395 F.2d 66, 69:

The record here discloses what the courts have pre-

viously commented on, that is it is rare, almost to the

point of nonexistent, that a white child, under a free-

dom of choice plan, elects to attend a “predominantly

Negro” school. As this court said in the first Jeffer-

son case:

“In this circuit white students rarely choose to

attend schools identified as Negro schools. . . .”

Yet on August 20, 1968, only four months later, the

Adams dicta outlawed any freedom of choice plan “if in a

school district there are still all-Negro schools”.

Again on September 24, 1968, in Graves the panel

said:

In its opinion of August 20, 1968, this Court noted that,

under Green (and other cases), a plan that provides

for an all-Negro school is unconstitutional.

Judge Bell sounded a warning in Jefferson IV which is

accentuated by the decision in these twenty-five consoli-

dated cases. The deviation from accepted constitutional

principles and the destructive effect upon the desegregation

process is increasing with every decision by a panel of this

Court. On July 1 of this year, Judge Bell said in Jefferson

IV:

I concur in the opinion and the result thereof except

to the extent, if any, that the decisions of this court

cited therein may exceed the requirements laid down

by the Supreme Court in Green v. County School Board

of New Kent County, Virginia, 391 U.S. 430 (1963);

Raney v. Board of Education of Gould, Arkansas, 391

U.S. 443 (1968); Monroe v. Board of Commissioners

of the City of Jackson, Tennessee, 391 U.S. 450 (1968),

to-wit: that the dual school systems be disestab-

28

lished. I am in fundamental disagreement with the

approach of an appellate court stipulating the details of

transition plans where couched in terms of constantly

escalating interim demands. The specter of escala-

tion, with no end in sight, retards the disestablishment

process.

Congress has never acted as it could have under Section

5 of the Fourteenth Amendment to set uniform stand-

ards for disestablishing dual school systems. Mean-

while, no court has defined “disestablishment”. My

view continues to be that school systems are entitled

to know the ultimate standard. United States v. Jef-

ferson County Board of Education, 5 Cir., 1967, 380

F.2d 385, dissenting opinion at p. 413.

It is clear that when the HEW plans are put into ef-

fect as terminal plans, including the alternate or “interim

steps” in student and faculty integration, these plans will

be operated as unitary non-racial non-discriminatory uni-

tary school systems, unless the Court holds that every

single element mentioned in Green, Raney and Monroe is

a separate sine qua non of such system.

We respectfully submit that even if the most extreme

interpretation were correct, alternate or “interim steps” are

permitted. There is little difference betwen the word “im-

mediately” used in the Per Curiam order of October 29 and

the word “now” as was said in this connection by Judge

Bell at the Pre-Order hearing (Tr. p.6): :

Now, that is the language of the Supreme Court deci-

sion. It is a little different from some of the language

used in the other Supreme Court decisions but prob-

ably means the same thing.

We attach as “Exhibit A” hereto, several typical illus-

trations of “composite building information” contained in

the HEW plans showing the ultimate effect thereof with-

out using the interim or alternate steps. It will be noted

29

that the student integration is substantially to a racial bal-

ance.

All of the 25 judgments entered in these cases

(through attachment of detailed plans made a part of the

general judgment) contain the ultimate mandatory provi-

sion that “principals, teacher-aides and other staff” shall

be assigned:

. . . that the ratio of negro to white teachers in each

school, and the ratio of other staff each are substan-

tially the same as each such ratio is to teachers and

other staff, respectively in the entire school system.

The initial or alternative step in these judgments re-

quired a ratio balance to the extent of 50% of the ultimate

goal. When the Court of Appeals put into effect the ulti-

mate goal it has resulted in judgments violating the teach-

ing of Carr.

COMPOSITE RUILLING INFORMATION FORM

2 = ~ ; ; : CC .

pain Lins m er 3 So TOR A JIE AT 1 7¢ 9-70 FECAL KS (rn Udi yy ~YCrlllA S

! Capacity ll Students Staff

Name of School Grades | Perm. J. Pores, | W N T Ww N T Comments

|

FRANK LL De 4/3 8/380 == SL 5/0 CIT

|

a »! ’

Liccee Hae Devt [ -& JOA — 5371560 1/697

| | .

¢

0

i rd [08311072 R185 Ew

| 2

>

Jones Socema (weenped) TA LG

KETARDE DD i

i

|

|

7

CRALD TIAL. 1694 |/075 2G

{G INFORMATION FORM ¥

i 1.01 V BUL oSITe govp

| |

i

-

»

«TN.

sy

a

A

AL rte OF

rg

Staff

S

IS

[oS

Studen

3

Grades

School Name of

EE GE a ER LE FOR

oof

fhepec? 4

Dn E: [47-70 ‘af guts

Capacity i Students I Starf

arc of Schaal Credes Perm. i Poprs, I N 2 nh vw N I Comments

pal g20]| 237)

RRM

_ ee ply ok | 213 | 39571 463

Lisi ol 1200 | Joo | p00

N22 / -[ | | 257 N50 | 400

a el £3 | 57 11493 Ly

| Sori tl 2. /

2088 7229 [4314

Ni €e

TORMATION FORM \

Lawperorre Coun Ty 752-20 YA I Ar ERP

Ss

L

-

-

2

AN

=

Ne.

bi

~

2

Ps

r

5

=

N

e

~

L

)

13

L

E

S

Q

w|

Ny

[1

Q

N

y

.

=

HS

|

&

oN

=

p

N

a

~ts

L

Y

)

RK

>

n

e

Bl.

|

3%

Ng

S

l

)

5

KY

~~

x

bt

$

x

h

y

N

0

n

L

=

-

[%)

uv

L

Te

S

s

R

D

A

s

I

R

R

B

i

A

_

B

E

A

R

a

N

p

as Lo

~

a

3

N

\

-

=

MN

o

N

oR

SA

SL

E

r

X=

[TS]

a

:

Uy

S

e

[Vl

fet

NES

L

O

s

wn

o

F

S

H

h

N

HL H

E

A

h

n

L

t

a

=

oe

Le

2

[4 [3]

©

\

al

Q

$e

E

N

(&}

34

vi

L

S

E

Q

Oo]

IN

a9}

f

~

Swiiie

NG

dy

lice

ort

[9]

%

n

e

exe

fa)

T

[e)

are z 3]

v3

wn

os

~

wr

(

[eo]

(J)

NY

E

3

2

B

~

—

i

o

8

\~

[3]

N

D

t

y

™

\

=

~

c

~

a)

Gf

=

aent

h

X2

>

pS

EAT

C

l

l

0

E

R

A

S

OS

a

n

e

pre

a

o

r

e

r

—

5

=o

)

Fr

<

D

O

Q

Q

Th

~S3

i

e

,

A

(4)

Ua

0

~

S

3)

)

| PS

P|

~

~

Bu

<

»

Niaing

=

S

C

R

E

a

e

Fis

Oo

o

Qo

.

o

So

2a

5

™y

Lu

©

hy

1]

Ey,

oat: _[haTecded 1969-40

COMPOLLLE SLIDING TWEORMATION FORM

Lincaln County

BE i om id ASSERT BR LE ESE BA

GE

Capacity Students Staff

Name of School Grades Perm, W. Ports. W N T N T Comments

Eva Hares Hich /o—-12 5 4p Clo Bsa 2ol \ LoL au Xi 1dr ehosinm

Loyd Staw Tr. Hyél, 4-9 2D 209 | [85 274

LE eras Fo vs, {= 210 /2 Ef) 79 247.

Meet Lincoln /=9 TA 222] 135) ru)

[Fp ue Chitto 2-9 10 Fr 22/362/

TE Ae I 2/0 JIE a7 lpn

Enter prise / =2 260 220 /25| B55]

Wi 167/\ 10/2268

LUiLPIIG INFORMATION FORM (NEUSE

Vr a = Thies

DAEs J 24 2 2.4

Capacity Students i!

Name of School Grades Perm. W. Ports. W N T | Comments

3 8] Take HAE

dle

| I

Dnt sill tl te LY TL of 0 T T0220 ooo | i

Vi - plinihe |

Frere alll | 7-8 217 10 £27 97) rami sods | I

H

. | {i

rrr BELA Ln $433 of LRA 20024 2|082 | i

=f sing LY fr AS |

fol a tt A Ste Vr FAVE dab-3 7 3

GAD. Jitter ;

ff le PTD AA RE TAAL REAL

|

Arr EAS 20 =02 | ets Fro | te s|agn | Fo; | db

ND

27.7.3 233” Ress LZ 79 £l 20 oh

V4

37

The result of the alternate or interim steps is the

equivalent of pairing of three out of seven schools in Leake

County; pairing of grades one through six in Franklin

County; pairing of four out of seven schools in Lincoln

County; pairing of seven out of twelve grades in the Holly

Bluff District; pairing of students in three out of seven

school buildings in the Yazoo City District and equivalent

effect in Lauderdale County. As thus modified, freedom

of choice would remain until September 1970 when the

ultimate steps would be taken.

CONCLUSION

We respectfully submit that a rehearing should be

granted in this matter or at least that the mandate be

amended so as to clarify the discretion vested in the Court

of Appeals and to also make it clear that complete integra-

tion of students and faculty comparable to the racial com-

position of the school system is not required.

We hereby certify as attorneys of record for the Re-

spondents that this Petition for Rehearing is presented in

good faith and not for delay.

Respectfully submitted,

JOHN C. SATTERFIELD

and

JupGgeE A. F. SUMMER

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I hereby certify that copies of the foregoing Motion

for Rehearing were served on the opposing counsel on this

21st day of November, 1969, by mailing copies of same,

postage prepaid, at the last known address as follows:

Melvyn R. Leventhal

Reuben V. Anderson

Fred L. Banks, Jr.

John A. Nichols

538-1/2 North Farish Street

Jackson, Mississippi 39202

Jack Greenberg

Jonathan Shapiro

Norman Chachkin

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York

Jeris Leonard

Assistant Attorney General

Department of Justice

Washington, D. C.

Erwin N. Griswold

Solicitor General of the U. S. Department of Justice

Washington, D. C.

Robert E. Hauberg

United States Attorney

Post Office Building

Jackson, Mississippi

JOHN C. SATTERFIELD

Jupce A. F. SUMMER