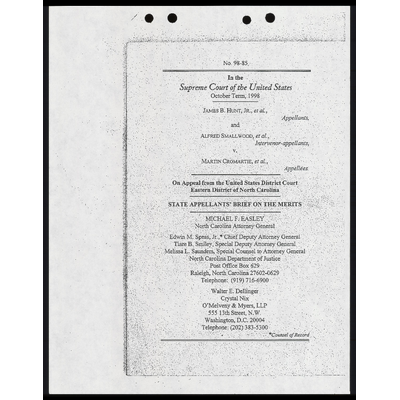

State Appellants’ Brief on the Merits

Public Court Documents

November 10, 1998

58 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Cromartie Hardbacks. State Appellants’ Brief on the Merits, 1998. 4ac58ba7-d90e-f011-9989-7c1e5267c7b6. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/7a5422fd-f41b-42d2-8f37-51859da9fa4c/state-appellants-brief-on-the-merits. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

ial te 98-85, : Tag

i In the ns = RL

Sarma Coir of the United States pigs

October T Term; 1998 2 pare

5 Javies B HoT, =r, et al,

ALFRED SMALLWOOD, et tal,

= in MARTIN CROMARTE,, ef tal,

CAA 3) opellans : : a Ta

ON Seri

a 2 : ; SE

on Appeal from the ST States District Court. he Ri

rict Ranke Carolina %

°E dwin M. Speak, | r. x Chief Desi Aiomey General

"i Tiare B. Smiley, Special Deputy Attorney. General

Melissa] L. ‘Saunders, Special Counsel to General 2 . i IE : |

ak North Carolina Department of Justice

ns “7 Post Office Box 629.

Raleigh, North Carolina 27602- 0629

Mr 019) 716- 6900

Walter. Dellinger 4 Ti i PRI

AE . Crystal Nig. ole nit, pi

i OMaveny & Myers, Lp

555 13th Street, N.W.

‘Washington, DC: 20004

Telephone: or 383 5300

re EL wot nL ies

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

In a racial gerrymandering case, is an inference drawn

from the challenged district’s shape and racial

demographics, standing alone, sufficient to support

summary judgment for the plaintiffs on the contested

issue of the legislature’s predominant motive in

designing the district, when that inference is directly

contradicted by the affidavits of the legislators who

drew the district?

In applying the Shaw-Miller predominance test, may a

court rely on isolated and sporadic party registration

data to reject a state’s assertion that partisan political

considerations were the predominant factor in a

district’s design, when the uncontroverted evidence

established that the state used actual voting results,

rather than party registrationdata, to shape the district’s

boundaries? |

May a plaintiff subject a majority-maj oritydistrict with

a substantial minority population to the strict scrutiny

of the Shaw-Miller doctrine, simply by showing that it

is slightly irregular in shape and contains a higher

concentration of minority voters than its neighbors,

when there is absolutely no additional evidence that

race was the predominant factor in its design?

ally left blank.

i

ion

is page intent Th

E

R

T

iii

LIST OF PARTIES

JAMES B. HUNT, JR., in his official capacity as Governor of

the State of North Carolina, DENNIS WICKER in his official

capacity as Lieutenant Governor of the State of North Carolina,

HAROLD BRUBAKER in his official capacity as Speaker of

the North Carolina House of Representatives, ELAINE

MARSHALL in her official capacity as Secretary of the State

of North Carolina, and LARRY LEAKE, S. KATHERINE

BURNETTE, FAIGER BLACKWELL, DOROTHY

PRESSER and JUNE YOUNGBLOOD in their capacity as the

North Carolina State Board of Elections, are appellants in this

case and were defendants below;

ALFRED SMALLWOOD, DAVID MOORE, WILLIAM M.

HODGES, ROBERT L. DAVIS, JR., JAN VALDER,

BARNEY OFFERMAN, VIRGINIA NEWELL, CHARLES

LAMBETH and GEORGE SIMKINS are intervenor-appellants

‘in this case and were intervenor-defendants below:

MARTIN CROMARTIE, THOMAS CHANDLER MUSE,

R. O. EVERETT, J. H. FROELICH, JAMES RONALD

LINVILLE, SUSAN HARDAWAY, ROBERT WEAVER and

JOEL K. BOURNE are appellees in this case and were

plaintiffs below.

This page intentionally left blank.

v

TABLE OF CONTENTS

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

LIST OF PARTIES

JURISDICTION

CONSTITUTIONAL AND STATUTORY

PROVISIONS INVOLVED

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

A. THE 1997 REDISTRICTING PROCESS

B. THE 1997 PLAN

D. THE THREE-JUDGE DISTRICT COURT’S OPINION ..

E. THE INTERIM PLAN

I. THE DISTRICT COURT’S JUDGMENT

SHOULD BE REVERSED BECAUSE

PLAINTIFFS FAILED TO CARRY THEIR

BURDEN OF PROVING THAT RACE WAS

THE PREDOMINANT FACTOR IN THE

DESIGN OF DISTRICT 12

vi

A. THE DISTRICT COURT APPLIED AN IMPROPER

EVIDENTIARY STANDARD IN GRANTING

PLAINTIFFS SUMMARY JUDGMENT. ......c..... 17

. PLAINTIFFS FAILED TO SATISFY THE

DEMANDING PREDOMINANCE STANDARD

NECESSARY TO SUPPORT STRICT SCRUTINY. .... 18

1. Plaintiffs’ Circumstantial Evidence Derived

From The Shape And Demographics Of The

District Was Inadequate To Establish The

Predominant Use Of Race. ........ cx... 22

. Defendants’ Direct Evidence Clearly

Established That Non-Racial Goals Were

The Predominant Factor In The Design Of

District 12. This Evidence Was Sufficient

Not Only To Defeat Plaintiffs’ Motion But

To Obtain Summary Judgment For

Defendants. ........ ei TO SNR 24

. THE DISTRICT COURT WRONGLY DENIED

THE STATE’S CROSS-MOTION FOR

SUMMARY JUDGMENT BECAUSE THE

STATE PRESENTED SUBSTANTIAL AND

CREDIBLE EVIDENCE THAT DISTRICT 12'S

SHAPE AND RACIAL DEMOGRAPHICS

WERE THE RESULT OF LEGITIMATE,

NON-RACIAL, POLITICAL MOTIVES. ...... 28

A. THE STATE’S RELIANCE ON VOTING

BEHAVIOR DOES NOT TRIGGER STRICT

SCRUTINY. ... vu ain ssw sina sities es tivnin's s sansa 30

vii

B. THE DISPARITY BETWEEN PARTY

REGISTRATION AND VOTING BEHAVIOR IN

NORTH CAROLINA EXPLAINS THE SHAPE

AND RACIAL DEMOGRAPHICS OF

DISTRICT 12. . sists dade os ial 31

. TO DETERMINE THE LEGISLATURE’S

PREDOMINANT MOTIVATION IN DESIGNING

A DISTRICT THE COURT MUST CONSIDER

THE DISTRICTASA WHOLE. .............. 34

III. APPLICATION OF STRICT SCRUTINY TO

DISTRICT 12 IS UNWARRANTED BECAUSE

IT DOES NOT GIVE RISE TO THE KINDS OF

HARMS WITH WHICH THE SHAW-MILLER

DOCTRINE IS CONCERNED. .............. 38

CONCLUSION ..il 0000.0: aici ales 44

OE

R

A

P

a

viii

[This page intentionally left blank.]

1X

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

CASES

Abrams v. Johnson, 521 US. 74 (A997)... ovine sun. 6

Anderson v. Liberty Lobby, Inc.,

477 U8: 2801086 ii . os aces oi 17,19,26

Baker v. Carr,369U.S. 186 (1962) ................. 37

Borden, Inc. v. Spoor, Behrins, Campbell Young, Inc.,

1828 F. Supp 216 (S.DNN. 1993) ........ 00. 00 26

Burns w Richardson, MAUS. 750966) o.. 8 25

Bushy. Vera, 517U.8. 9521996) .......... .0 us er

Celotex Corp. v. Catrett, 477 U.S. 317 (1986) ...... 17,18

Davis v. Bandemer, 478 U.S. 109 (1986) ............. 35

DeWitt v. Wilson, 515 U.S. 1170 (1995),

summarily aff’g, 856 F. Supp. 1409 (E.D. Ca. 1994) .. 40

Edwards v. Aguillard, 482 U.S. 578 (1986) ........ 22,43

Gaffney v. Cummings, 412 U.S. 735 (1973) ........ 24,42

Hllinois v. Krull, 480 U.S.340 (1987) ........cvv..... 26

Johnson v. Miller, 922 F. Supp. 1556 (S.D. Ga. 1995),

afd, 21 U8, 7401097) .... occu sia inn 4,6

X

Johnson v. Mortham, 915 F. Supp. 1529

(ND. Fl8, 1003) .. nes va sda Bs cles os 27

Joint Anti-Fascist Refugee Comm. v. Mc Grath,

34 U.S. 123 (108) es less avian nov aininin miims sain os 26

Karcher v. Dageett, 462 U.S. 725 (1983) ....... 0a’ 25

Lawyer v. Department of Justice, 521 U.S. 567,

1178. CLRIBOI007) ss vs oars evi s si nssns svn 20, 43

McDonald v. Board of Election Comm rs of Chicago,

BOATS. 80241989) '. v. + « «cis vis «Hal wih wives 26

Miller v. Johnson, 515 U.S. 900 (1995) .......... passim

Mueller v. Allen, 463 U.S. 388 (1983) ............... 26

Nunez v. Superior Oil Co.,572 F.2d 1119 (CA5 1978) .. 26

Price Waterhouse v. Hopkins, 490 U.S. 228 (1989) ..... 43

Rosther v. Goldliers. 455 US STQBY) L000... 26

Shaw v. Hunt (Shaw II), 517 U.S. 899 (1996) .... 2,20,21

Shaw v. Reno (Shaw I), 509 U.S. 630 (1993) . 19, 38, 39, 40

Starceski v. Westinghouse Elec. Corp.,

54 F.3d 1080 (CAI T9953) it. ovis consvsnainnsyetininis 43

Thornburg v. Gingles, 478 U.S.30 (1986) ............ 36

United States v. Hays, 515 0.8.737(1995) ........... 39

X1

Vera v. Bush, 933 F. Supp. 1341 (S.D. Tex. 1996) ....... 4

White v. Weiser, 120.8. 783 (1973) vn sane n se nvuins 25 :

Wightman v. Springfield Terminal Ry. Co., :

100 F.3¢. 2284CATA006) : oh... oii Bisu iii ik 18 }

STATUTES i

WUC S153. Le Ck dR 1

MISCELLANEOUS

11 JAMES WM. MOORE, ET AL., MOORE’S

FEDERAL PRACTICES 56.034]. ...........5 ervey 17

11 JAMES WM. MOORE, ET AL., MOORE'S

FEDERAL PRACTICES 56.10[6] ....coniev cv eins, 18

11 JAMES WM. MOORE, ET AL., MOORE'S

FEDERAL PRACTICE S$ 36, 11J1UD] ..v nuteseniinnsin. 17

DD

© = B.. >

o

y

od = e)

=

= y =

®

pod

(3)

of

o a,

2 = f=

p

s

{

R

e

B

R

S

C

e

53

STATE APPELLANTS’ BRIEF ON THE MERITS

Governor James B. Hunt, Jr., and the other state defendants

below appeal from the final judgment of the three-judge United

States District Court for the Eastern District of North Carolina,

dated April 6, 1998, which declared District 12 in the

congressional redistricting plan enacted by the North Carolina

General Assembly on March 31, 1997, unconstitutional and

permanently enjoined defendants from conducting any

elections under that plan.

OPINIONS BELOW

The April 14, 1998 opinion of the three-judge district court,

which has not yet been reported, appears at JS at 1a.!

JURISDICTION

The district court’s judgment was entered on April 6, 1998.

On April 8, 1998, defendants filed an amended notice of appeal

to this Court. Jurisdiction of this Court on appeal is § fnvoked

under 28 U.S.C. § 1253.

CONSTITUTIONAL AND STATUTORY

PROVISIONS INVOLVED

This appeal involves the Equal Protection Clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United States

and Rule 56 of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, Summary

Judgment. See JS at 169a & 171a-173a.

! References to “JS” are to the Appendix of the Jurisdictional

Statement; references to “JA” are to the Joint Appendix.

Lat al

2

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

A. THE 1997 REDISTRICTING PROCESS

In Shaw v. Hunt (Shaw II), 517 U.S. 899 (1996), this Court

held that District 12 in North Carolina’s 1992 congressional

redistricting plan (“the 1992 plan”) violated the Equal

Protection Clause because race predominated in its design and

it could not survive strict scrutiny. The matter was remanded

to the district court for an appropriate remedy. On remand, the

district court afforded the state legislature an opportunity to

redraw the state’s congressional plan to correct the

constitutional defects found by this Court. The General

Assembly established Senate and House redistricting

committees to carry out this task. Senator Roy A. Cooper, III,

a Democrat, was appointed Chairman of the Senate Committee

and Representative Edwin McMahan, a Republican, was

appointed Chairman of the House Committee. JS at 70a, 80a.

~ Like the majority of members on the committees, neither

Senator Cooper nor Representative McMahan had served on

the committee that drafted the 1992 plan.’

In consultation with the legislative leadership, the

committees determined that, to pass both the Democratic-

controlled Senate and the Republican-controlled House, the

new plan needed to maintain the existing partisan balance in

the state’s congressional delegation (a six-six split between

Democrats and Republicans). Because party registration is not

2 Only 11 of the 41 legislators appointed to these committees had

served on the redistricting committees that drafted the 1992 plan. See

Bartlett Aff. (CD 47),Vol. I Commentary at 5.

~

J

a reliable predictor of voting behavior, the committees used the

actual votes cast in a series of elections between 1988 and 1996

to craft Democratic and Republican districts. These election

results were the principle factor that guided the committees in

configuring the plan and in placing precincts within the

districts. JS at 71a, 73a, 77a, 80a-81a, 81-82a.

In designing the plan, the committees sought to comply

with the requirements of the Voting Rights Act, as well as the

constitutional requirement of population equality. JS at 73a-

77a, 82a-83a; JA at 63a. Well aware of their responsibilities

under this Court’s decision in Shaw and its progeny, however,

the committees ensured that racial considerations did not

predominate over race-neutral districting criteria. To this end,

the new plan was designed: (1) to avoid dividing precincts; (2)

to avoid dividing counties when reasonably possible;* (3) to

* The computerized data base the committees used to draw the plan

included the total number of people in each precinct who voted for each

major candidate in the 1988 Court of Appeals election, the 1988 Lieutenant

Governor election, and the 1990 United States Senate election. See JA at

101-110. In addition, both the Senate and House committees used precinct-

by-precinctelection results for a series of statewide elections between 1990

and 1996 to draw the plan. JS at 73a, 81a.

* In North Carolina, as in most of the southeasternstates, it is virtually

impossible to design a congressional map that does not split any of the

State’s 100 counties, given the constitutional mandate of population

equality and other legitimate districting concerns. Indeed, all of the

southeastern states currently include multiple county divisions in their

congressional plans, and in Florida's congressional plan 26 of 67 counties

(38.8%) are divided. JS at 109a-110a, 115a-116a. For this reason, the

committees chose to avoid dividing counties only to the extent reasonably

possible.

i im Ntamn Varn Fe mend 1 mn Rent

4

eliminate cross-overs, double cross-overs, and other artificial

means of maintaining contiguity; (4) to group together citizens

with similar needs and interests; and (5) to ensure ease of

communication between voters and their representatives. JS at

72a, 81a, 63a-64a. The committees did not utilize shape or

mathematical compactness measures in constructing the plan.

The committees’ strategy proved successful. On March 31,

1997, the North Carolina legislature enacted a new

congressional redistricting plan, 1997 Session Laws, Chapter

11 (“the 1997 plan”), the redistricting law at issue in this case.’

The plan was a bipartisan one, endorsed by the leadership of

both parties in both houses. See JS at 77a, 82a-83a, 64a.

However, twelve of the seventeen African-American members

of the House voted against the plan because they believed it did

not adequately take into account the interests of the State’s

African-American residents. See JS at 83a.

B. THE 1997 PLAN

The 1997 plan creates six “Democratic” districts and six

“Republican” districts. These districts preserve the partisan

cores of their 1992 predecessors, yet their lines are significantly

different: they reassign more than 25% of the State’s

* In this respect, the North Carolina legislature succeeded where other

similarly - situated state legislatures have not. See, e.g., Johnson v. Miller,

922 F. Supp. 1556, 1559 (S.D. Ga. 1995), aff'd, 521 U.S. 74 (1997) (on

remand from this Court’s decision in Miller v. Johnson, 515 U.S. 900

(1995)) (legislature abdicated its redistricting responsibilities to federal

district court); Vera v. Bush, 933 F. Supp. 1341, 1342 (S.D. Tex. 1996) (on

remand from this Court’s decision in Bush v. Vera, 517 U.S. 952 (1996)

(same).

5

population and nearly 25% of its geographic area. The most

dramatic changes are in District 12, which contains less than

70% of its original population and only 41.6% of its original

geographic area. JS at 130a-132a, 153a, 155a.

The 1997 plan respects the traditional race-neutral

districting criteria identified by the legislature. In particular,

District 12 divides only one precinct (a precinct that is divided

in all local districting plans as well); it includes parts of only

six counties; and it achieves contiguity without relying on

artificial devices like cross-overs and double cross-overs.S It

creates a district joining together citizens with similar needs

and interests in the urban and industrialized areas along the

interstate highways that connect Charlotte and the Piedmont

Urban Triad, areas in which the bulk of the State’s recent

population growth has occurred. JS at 63a-67a, 73a-74a, 82a,

Stuart Aff. (CD 47), Rpt. at 9-10. Of the 12 districts in the 1997

plan, it has the third shortest travel time (1.67 hours) and the

third shortest distance (95 miles) between its farthest points,

making it “highly accessible” for a congressional repre-

sentative.” JS at 105a. Moreover, because District 12 is built

around major transportation corridors, it functions effectively

® In contrast, District 12 in the 1992 plan divided 48 precincts:

included parts of 10 counties; and achieved contiguity only by heavy

reliance on artificial devices like cross-overs and double cross-overs. See

JS at 63a.

’ In contrast, District 12 in the 1992 plan had a travel time of 2.97

hours and a travel distance of 162.4 miles between its farthest points,

ranking it in the bottom one-third of North Carolina’s 12 districts based on

time and distance. See JS at 105a-106a.

6

for representatives and for constituents.!? Mathematical

measures of geographic compactness were not among the

criteria adopted by the legislature in designing the new plan.

Even so, District 12’s geographic compactness is significantly

improved over the 1992 plan, though it remains relatively low.’

Seventy-five (75%) percent of District 12’s registered

voters are Democrats. More importantly, at least 62% of the

district’s registered voters voted for the Democratic candidate

in the 1988 Court of Appeals election, the 1988 Lieutenant

Governor election, and the 1990 United States Senate election.

JS at 99a.

District 12 is not a majority-minority district by any

measure: only 46.67% of its total population, 43.36% of its

voting age population, and 46% of its registered voter

8 See Webster Report, JS at 124a-130a, 134a (noting that District 12’s

“focus upon major transportation corridors” makes its travel time

compactness substantially better than that of many districts that score higher

under mathematical measures of compactness). District 12 is similar in

concept to Georgia's new Eleventh Congressional District, drawn by a

three-judge district court when the Georgia legislature could not agree on

a new plan in the wake of this Court’s 1995 decision in Miller. The

Eleventh District stretches from suburban Atlanta to the North Carolina and

Tennessee borders, connecting parts of 13 different counties and splitting

six of them. Because the district is built around the “connecting cable” of

Interstate 85, however, and has a distinct “urban/suburban flavor,” its

residents have “a palpable community of interests.” Johnson v. Miller, 922

F. Supp. at 1564. In Abrams v. Johnson, 521 U.S. 74 (1997), this Court

upheld the Eleventh District as drawn.

? District 12’s dispersion compactness measure in the 1997 plan is

142% improved over the 1992 plan and its perimeter compactness measure

is 193% improved. See JS at 127a -128a, 143a-146a.

7

population is African-American." Race was not a dominant or

controlling factor in the development or enactment of the plan.

JS at 77a, 83a, 87a-88a. Partisan voting patterns, not race, were

the predominant basis for assigning voters to the district.!! See

JS at 66a-67a, 77a, 82a-83a, 99a.

Because 40 of North Carolina’s 100 counties are subject to

the preclearancerequirementsof Section 5 of the Voting Rights

Act, the legislature submitted the 1997 plan to the United

States Department of Justice for preclearance. The Department

precleared the plan on June 9, 1997.

C. LEGAL CHALLENGES To THE 1997 PLAN

Equal protection challenges to the 1997 plan were first

raised in the remedial phase of the Shaw litigation, when the

State submitted the plan to the three-judge court to determine

whether it cured the constitutional defects in the earlier plan.

Two of the plaintiffs who challenge the 1997 plan in the instant

In contrast, 56.63% of the total population, 53.34% of the voting age

population, and 53.54% of the registered voter population of District 12 in

the 1992 plan was African-American. See JA at 111-117.

"District 1 is another of the six “Democratic” districts established by

the 1997 plan. Unlike District 12, District 1 is a majority-minority district

by one measure: 50.27% of its total population is African-American. Like

District 12, District 1 respects the traditional race-neutral redistricting

criteria identified by the legislature. It contains no divided precincts, divides

only 10 counties and achieves contiguity without relying on artificial

devices like cross-overs and double cross-overs. It creates a district joining

together citizens in the mostly rural and economically depressed counties

in the State’s northern and central Coastal Plain. See JS at 63a-67a, 73a-74a,

82a, JA at 101-105, Goldfield Aff. (CD 47), Rpt. at 8-12.

8

case - Martin Cromartie and Thomas Chandler Muse -

participated as parties plaintiff in that remedial proceeding. So

did Robinson Everett, who was both a named plaintiff and the

plaintiffs’ attorney in the Shaw case.

In that remedial proceeding, Everett and his co-plaintiffs

(“the Shaw plaintiffs”) were given an opportunity to litigate any

constitutional challenges they might have to the 1997 plan,

which the State had enacted under the Shaw court’s injunction.

They elected not to avail themselves of that opportunity.

Exercising its authority to review the State’s proposed

remedial plan, the court ruled that the plan was “in conformity

with constitutional requirements” and that it was an adequate

remedy for the constitutional defects in the prior plan “as to the

plaintiffs and plaintiff-intervenors in this case.” JS at 167a,

160a. On that basis, the court entered an order approving the

plan and authorizing the state defendants to proceed with

congressional elections under it. Everett and his co-plaintiffs

took no appeal from that order. |

Having forgone an opportunity to litigate their

constitutional challenges to the 1997 plan before the three-

judge court in Shaw, Everett and his co-plaintiffs sought to

have those same claims adjudicated by a different three-judge

court. They did so by amending a complaint in a separate

lawsuit they had previously filed against the same defendants.

In that amended complaint, Cromartie, Muse, and four persons

who had not been named as plaintiffs in Shaw (“the Cromartie

plaintiffs”) - all represented by Everett - asserted racial

Fx

9

gerrymandering challenges to Districts 1 and 12 in the 1997

plan.

On January 15, 1998, the Cromartie case was assigned to

a three-judge panel. On January 30, 1998, four days before.the

close of the candidate filing period, the Cromartie plaintiffs

moved for a preliminary injunction halting all further elections

under the 1997 plan. Several days later, they also moved for

summary judgment. The state defendants filed a cross-motion

for summary judgment. On March 23, 1998, the last day on

which the parties were allowed to file materials in support of

the motions for summary judgment, the Cromartie plaintiffs

filed their expert witness affidavits and various statistical

2 In their Jurisdictional Statement, the state defendants challenged the

Jistrict court’s ruling that the final judgment entered by the district court on

'emand from this Court’s decision in Shaw II - a judgment which found the

1997 plan constitutionaland authorized the State to proceed with elections

ander it - did not preclude the constitutional challenges to that very plan that

- re being asserted in this parallel proceeding. The state defendants continue

0 believe that the District 12 claims asserted in this case are barred by that

‘inal judgment because they are asserted by persons who must - in fairness -

de considered “privies” of at least one of the named plaintiffs in Shaw,

Robinson Everett. Because the policies behind the doctrine of claim

sreclusion are at their most compelling when the claims in question seek to

:njoin a state’s electoral processes, and the entry of two dramatically

nconsistent judgments against a state in parallel litigation involving such

:losely affiliated plaintiffs is an affront to the integrity of the federal judicial

iystem, this Court should craft a rule of privity that would bar these claims.

he state defendants recognize that the record, as it now stands, may be

nsufficient to permit this Court to undertake that task. Accordingly, they

1ave elected not to press that argument further on this appeal, but to save

t for remand, should this Court deem a remand necessary for other reasons.

E

R

BEI 0 RIL Tt DI NL, J TR

10

information, including maps showing partisan registration by

precinct in portions of District 12.13

Eight days later, before either party had conducted any

discovery and without an evidentiary hearing, the three-judge

court heard brief oral arguments on the pending motions for

preliminary injunction and summary judgment. Three days

after that, on April 3, 1998, the court, with Circuit Judge Sam

J. Ervin, III dissenting, granted the Cromartie plaintiffs’

motion for summary judgment, declared District 12 in the 1997

plan unconstitutional, and permanently enjoined the state

defendants from conducting any primary or general elections

under the 1997 plan. JS at 45a. The court’s order did not

explain the basis for its decision, stating only that

“[m]emoranda with reference to [the] order will be issued as

soon as possible.”* JS at 46a.

> Prior to that point, plaintiffs only had filed several incompetent

affidavits of laypersons with no personal knowledge about the redistricting

process. See JA at 47-83 and at 137-155. Had they been afforded an

adequate opportunity to respond to plaintiffs’ eleventh hour showing,

defendants could have cleared up the court’s misunderstandingof plaintiffs’

irrelevant registration data (that the redistricting committees had not used

in fashioning the 1997 plan) with the more probative election results (that

the committees in fact relied upon). See Argument II, infra.

4 The state defendants immediately noticed an appeal to this Court.

Since the elections process under the 1997 plan was already underway and

the primary election only a few weeks away, they asked the district court to

stay its April 3rd order pending disposition of that appeal. When it refused

to do so, the state defendants made application to Chief Justice Rehnquist

for a stay of the same order. The Chief Justice referred that application to

the full Court, which denied it on April 13, 1998. When this Court denied

the stay application, the district court had yet to issue its opinion explaining

its order and permanent injunction.

11

D. THE THREE-JUDGE DISTRICT COURT’S OPINION

On April 14, 1998, the three-judge court issued an opinion

explaining the basis for its order and injunction of April 3,

1998. JS at 1a-44a. The court held that the Cromartie plaintiffs

were entitled to summary judgment on their challenge to

District 12, because the “uncontroverted material facts”

established that the legislature had “utilized race as the

predominant factor in drawing the District." JS at 21a-22a.

Unlike the lower courts whose “predominance” findings this

Court upheld in Miller, Bush, and Shaw II, the court below did

not base its finding on any direct evidence of legislative

motivation; instead, it predicated its ruling of constitutional

invalidity entirely on an inference drawn from the district’s

shape and racial demographics. JS at 19a-22a.

The court reasoned that District 12 was “unusually shaped,”

that it was “still the most geographically scattered” of North

Carolina’s twelve congressional districts, that its dispersion and

perimeter compactness measures were lower than the mean for

the twelve districts in the plan, that it “include[s] nearly all of

the precincts with African-Americanpopulation proportions of

over forty percent which lie between Charlotte and

Greensboro,” and that when it splits cities and counties, it does

so “along racial lines.” The court concluded that these so-called

“facts,” established - as a matter of law - that the legislature had

'* The court also held that the Cromartie plaintiffs were nor entitled to

summary judgment on their challenge to District 1, the only majority-

minority district in the 1997 plan. JS at 22a-23a.

12

“disregarded traditional districting criteria” and “utilized race

as the predominant factor” in designing District 12.” JS at 20a-

22a.

Although the court acknowledged that the state defendants

had produced evidence that partisan political preference, rather

"than race, was the predominant factor in the design of District

12, it chose not to credit this evidence because “the legislators

excluded many heavily-Democraticprecincts from District 12,

even though those precincts immediately border the District.”

JS at 20a.

Judge Ervin dissented. At the outset, he noted that the :

plaintiffs in this case - unlike those in Miller, Bush, and Shaw

II - had presented no direct evidence that the legislature was

motivated predominantly by racial considerations in designing

District 12, but relied solely on an inference they claimed could

‘be drawn from the district’s shape and racial demographics. JS

at 26a-29a. He found this inference decidedly weaker than

those in the Court’s prior cases, because District 12 was not a

majority-minority district, it had not been drawn to comply

with the Department of Justice’s invalid “black maximization”

“policy, and its shape was “not so bizarre or unusual . . . that it

cannot be explained by factors other than race.”JS at 25a-26a,

30a-35a. |

16 In reaching this conclusion, the court relied entirely on maps offered

by plaintiffs showing the Democratic registration of precincts in Guilford,

Forsyth and Mecklenburg Counties. JS at 8a-9a. (citing McGee Aff. (CD

61), Exhibits N, O and P). The uncontested evidence presented by the State,

however, indicated that the legislature used election results, not party

registration, to measure the partisan nature of the districts. JS at 73a, 81a.

13

In addition, Judge Ervin noted, the state defendants had

rebutted the Cromartie plaintiffs’ circumstantial evidence with

“convincing” evidence that partisan political preference, rather

than race, had been the predominant factor in drawing the

district.” JS at 25a-26a, 34a-36a. According to Judge Ervin, the

case law required the court to accept this evidence as true.” JS

at 27a.

"7 In addition to presenting affidavits from the legislatorswho drew the

plan, the state defendants presented the expert statistical evidence of Dr.

David W. Peterson. Dr. Peterson conducted a comprehensive statistical

analysis of the correlation between District 12’s boundary and the race,

party affiliation, and political voting patterns of the voters in the precincts

that touch along the inside and outside of that boundary. He concluded that

the boundary’s path “can be attributed to political considerations with at

least as much statistical certainty as it can be attributed to racial

considerations,” that the statistical evidence “support[s] the proposition that

creation of a Democratic majority in District Twelve was a more important

consideration in its constructionthan was the creation of a black majority,”

and that “there is no statistical indication that race was the predominant

factor determining the border.” See JS at 872-88a, 99a.

18 As Judge Ervin correctly observed, the Cromartie plaintiffs’

evidence that District 12 excluded certain precincts with a large number of

registered Democrats did not undermine the credibility of this evidence, for

several reasons. First, it consisted not of a comprehensive examination of

the district’s entire circumference, but of selective examples. Second, it

ignored the fact that the legislators who drew the plan said they used actual

election results, rather than party registration figures, to construct the

district’s lines in recognition of the fact “that voters often do not vote in

accordance with their registered party affiliation.” JS at 33a-36a. Indeed, he

found the evidence that race had predominated in the design of District 12

so weak that he would have entered summary judgment against the

Cromartie plaintiffs on that claim. JS at 43a-44a. :

14

E. THE INTERIM PLAN

The district court allowed the General Assembly 30 days to

redraw the state’s congressional redistricting plan to correct the

defects it had found in the 1997 plan. On May 21, 1998, the

General Assembly enacted an interim congressional

redistricting plan, 1998 Session Laws, ch. 2 (“the Interim

Plan”), and submitted it to the district court for approval. The

Interim Plan specifically provides that it is effective for the

1998 and 2000 elections only if this Court fails to reverse the

district court decision holding the 1997 plan unconstitutional.

The Department of Justice precleared the Interim Plan on June

8, 1998. On June 22, 1998, the district court entered an order

tentatively approving the Interim Plan and authorizing the State

to proceed with the 1998 elections under it.'* JS at 175a-180a.

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

The judgment below is riddled with errors; it cannot stand.

Initially, in holding that plaintiffs were entitled to summary

judgment on their District 12 claim, ‘the district court |

committed three critical errors. First, the court improperly

required the state defendants to bear the burden of persuasion

. at summary judgment, when this Court’s cases make clear that

burden lies with the plaintiffs. Second, the court found the

predominance standard satisfied by evidence falling far short

of that which this Court has previously found sufficient to

impugn the considered choices of a state legislature. Third, the

'* On July 17, 1998, plaintiffs noticed an appeal from that order. This

Court has yet to act on that appeal.

rpm TTT ET TIN a ror mre pve AT AS a am Ct gem

15

court failed to accord the testimony of state legislators a

presumption of truthfulness and engaged instead in unfounded

second-guessing of their motivations, which this Court’s

precedents forbid it to do. Each of these errors independently

provides sufficient basis for reversing the lower court’s entry

of summary judgment for the plaintiffs.

The uncontroverted evidence in the summary judgment

record established that the legislature designed the districting

plan as a whole, and District 12 in particular, to preserve the

existing partisan balance in the State’s congressional

delegation, and that it used actual election results, not voter

registration data, to accomplish this purpose. In denying the

defendants’ motion for summary judgment, the district court

made at least two critical errors. First, it relied on voter

registration data, which the legislature did not use in designing

District 12. Second, it relied on limited information about a

handful of isolated precincts rather than carefully and fully

examining the design of the district as a whole. Had the district

court not made these errors, but correctly applied the law to the

uncontroverted facts before it, it would have been compelled to

enter summary judgment for the defendants.

North Carolina’s District 12 is a majority-majority district

with a substantial minority population. Its boundaries were

drawn on the basis of actual voting patterns in order to create

a plan that would preserve the existing partisan balance in the

State’s congressional delegation. Such a district, even if

somewhat oddly shaped, does not give rise to any of the harms

with which the Shaw doctrine is concerned. Because applying

the strict scrutiny of Shaw to such a district represents a

OBER REZR RSET WEAR SON PY

16

substantial - and indefensible - extension of this Court’s case

law, the district court’s decision must be reversed.

ARGUMENT

I. THE DISTRICT COURT’S JUDGMENT SHOULD BE

REVERSED BECAUSE PLAINTIFFS FAILED TO

CARRY THEIR BURDEN OF PROVING THAT

RACE WAS THE PREDOMINANT FACTOR IN THE

DESIGN OF DISTRICT 12.

In concluding that the defendants’ stated purposes for

drawing the boundaries of District 12 were false, and that race

was instead the predominant motivating factor, the district

court committed at least three manifest errors. First, the court

‘improperly required the state defendants to bear the burden of

persuasion at summary judgment, when this Court’s precedents

make clear that burden lies with the plaintiffs. Second, the

court found the Miller predominance standard satisfied on a

significantly lower evidentiary showing than this Court has

required in previous redistricting cases. Third, the court failed

to accord the State’s testimony a presumption of truthfulness,

a presumption mandated by this Court’s precedents. In light of

these fatal deficiencies, the district court’s grant of summary

judgment to plaintiffs should be overturned.

17

A. THE DISTRICT COURT APPLIED AN IMPROPER

EVIDENTIARY STANDARD IN GRANTING

PLAINTIFFS’ SUMMARY JUDGMENT.

A motion for summary judgment must be resolved by

reference to the evidentiary burdens that would apply at trial.

Andersonv. Liberty Lobby, Inc., 477 U.S. 242, 250-54 (1986).

When a party seeks summary judgment on an issue on which

he will have the burden of persuasion at trial, he is entitled to

prevail only if the evidence in the summary judgment record is

such that no reasonable fact finder hearing that evidence could

fail to find for him on that issue.” See id. at 252-55. In other

words, the movant’s evidence, viewed in the light most

favorable to his opponent, must be “so one-sided” that he

would be entitled to judgment as a matter of law at trial. See id.

at 249-52 (explaining that the summary judgment standard

“mirrors” the Rule 50(a) standard for a directed verdict at trial).

Under this stringent standard, a party who has the burden of

persuasion at trial is seldom entitled to summary judgment in

his favor. See 11 JAMES WM. MOORE ET AL., MOORE’S

FEDERAL PRACTICE § 56.03[4],at 56-37 through 56-38 & n.54; nl

id. § 56.11[1][b], at 56-90 through 56-91 (3d ed. 1997). ) SE

In this case, the burden of persuasion at trial for proving

that race was the predominant factor in the design of District 12

20 - By contrast, a party who will not have the burden of persuasion at

trial may obtain summary judgment simply by showing that his opponent

has insufficient evidence to permit a reasonable finder of fact to return a

verdict in his favor. See Celotex Corp. v. Catrett, 477 U.S. 317, 324-26

(1986).

18

clearly rested with the plaintiffs. See Miller v. Johnson, 515

U.S. 900, 916 (1995) (the plaintiff bears the burden of proving

the race-based motive). The district court ignored this

allocation of the burden of proof in concluding that the

plaintiffs were entitled to summary judgment. Indeed, a careful

reading of the court’s opinion makes clear that despite the

court’s assertions, it analyzed plaintiffs’ motion under the

standard that applies to parties who will not have the burden of

persuasion at trial.?! See JS at 21a (citing Celotex Corp. v.

Catrett, 477 U.S. 317, 324 (1986)). On this basis alone, the

court’s decision should be overturned.

B. PLAINTIFFS FAILED TO SATISFY THE DEMANDING

PREDOMINANCE STANDARD NECESSARY To

SUPPORT STRICT SCRUTINY.

In addition to misallocating the burden of persuasion, the

district court failed to require a sufficient evidentiary showing

that race - and not neutral redistricting criteria - was the

predominant factor motivating the State’s redistricting plan.

Had the district court applied the proper standard, it could not

21 That the court also had before it the state defendants’ cross-motion

for summary judgment should have had no bearing on its analysis of the

plaintiffs’ motion. See 11 JAMES WM. MOORE ET AL., MOORE’S FEDERAL

PRACTICE § 56.10[6] (3d ed. 1997) (cross-motions for summary judgment

must be evaluated independently,according to the usual summary judgment

standard, and the denial of one does not imply the grant of the other);

Wightmanv. Springfield Terminal Ry. Co., 100 F.3d. 228, 230 (CA1 1996)

(cross-motions for summary judgment do not alter basic Rule 56 standard,

nor do they necessarily warrant the grant of summary judgment to either

party).

19

have justified a grant of summary judgment. See Anderson, 477

U.S. at 252-55.

In Shaw I, this Court first recognized that a facially race-

neutral electoral districting plan could, in certain exceptional

circumstances, be a “racial classification” subject to strict

scrutiny under the equal protection clause. Shaw v. Reno (Shaw

I), 509 U.S. 630, 642-44, 646-47, 649 (1993). Two years later,

in Miller, this Court established a narrow condition for the

application of strict scrutiny: compelling evidence “that race

for its own sake, and not other districting principles, was the

legislature’s dominant and controlling rationale in drawing its

district lines.” 515 U.S. at 913 (emphasis added). To satisfy this

standard at the summary judgment stage, a plaintiff must prove

that the evidence, viewed in the light most favorable to the

defendant, demonstrates that the legislature “subordinated

traditional race-neutral districting principles . . . to racial

considerations,” such that race was “the predominant factor” in

the design of the districts. Id. at 916. |

In Miller, this Court recognized that “[f]ederal court review

of districting legislation represents a serious intrusion on the

most vital of local functions,” that redistricting legislatures are

almost always aware of racial demographics, and that the

“distinction between being aware of racial considerations and

being motivated by them” is often difficult to draw. 515 U.S.

at 915-16. For these reasons, this Court directed the lower

courts to “exercise extraordinary caution” in applying the

predominancetest. Id. at 916; see id. at 928-29 (O’Connor, J.,

concurring) (stressing that the Miller standard is a “demanding”

20

one, which subjects only “extreme instances of [racial]

gerrymandering” to strict scrutiny).

In its various opinions in Bush, this Court made clear that

neither proof the legislature considered race as a factor in

drawing district lines nor evidence the legislature neglected

traditional districting criteria is sufficient to trigger strict

scrutiny. Bush v. Vera, 517 U.S. 952, 958, 962 (1996) (plur.

op.). Instead, strict scrutiny applies only when the plaintiff

establishes both that (1) the State substantially neglected

traditional districting criteria in drawing district lines, and (2)

that it did so predominantly because of racial considerations.”

Id. at 962-63 (plur. op.); id. at 993-94 (O’Connor, J,

concurring). BL

In this case, plaintiffs clearly failed to meet their

evidentiary burden. A comparison of the evidence proffered in

the Court’s prior cases with that offered by the plaintiffs in this

case bolsters this conclusion. For instance, before applying

strict scrutiny and overturning Texas’ redistricting plan in

Bush, a plurality of the Court found not only that Texas’ district

was irregular in shape, but also that there was “substantial

direct evidence of the legislature’s racial motivations.” 517

U.S. at 960 (emphasis added). This evidence included the

state’s preclearance report to the Justice Department, which

2 Since Bush, this Court has twice applied this same formulation of

the threshold test for strict scrutiny. See Lawyer v. Department of Justice,

521 U.S. 567, _, 117 S. Ct. 2186, 2194-95 (1997) (finding standard not

satisfied); Shaw v. Hunt, (Shaw II), 517 U.S. 899, 906-07 (1996) (finding

standard satisfied).

21

“report[ed] a consensus within the legislature that the three new

congressional districts ‘should be configured in such a way as

to allow members of racial, ethnic, and language minorities to

elect Congressional representatives.’ Id. Because of this goal,

the report acknowledged, three majority-minority districts were

created. See id. at 960-61. In addition, the plurality found that

Texas legislatorshad used an unprecedented computer program

that “permitted redistricters to manipulate district lines on

computer maps,” making “more intricate refinements on the

basis of race than on the basis of other demographic

information.” Id. at 961-62. Taken together,” the plurality held,

these findings justified the application of strict scrutiny.

Likewise, in Miller and Shaw II, the Court applied strict

scrutiny only after finding that the districts’ bizarre geographic

shapes, coupled with the state defendants’ admissions that they

had intentionally set out to create majority-minority districts,

established that race was the predominant factor in the design

of those districts. See Miller, 515 U.S. at 917-18 (citing

Georgia’s admission that it “would not have added those

portions of” the counties “but for the need to include additional

black population in that district”); Shaw II, 517 U.S. at 906

(citing the State’s preclearance submission, which

¥ Notably, the Court emphasized that it was not holding that “any one

of these factors is independently sufficient to require strict scrutiny.” Bush,

517 U.S. at 962.

# Justices Thomas and Scalia, who joined in the judgment, held that

the state’s admission that it intentionally created majority-minority districts

was sufficient to justify strict scrutiny. See id. at 1002. No such admission

has been made in this case.

22

acknowledged that the district’s “overriding purpose” was to

create two majority-minority districts). No such evidence is

present in this case. .

1. . Plaintiffs’ Circumstantial Evidence Derived

From The Shape And Demographics Of The

District Was Inadequate To Establish The

Predominant Use Of Race.

In this case, the only evidence in the record that could even

remotely support the plaintiffs’ assertion of a predominantly

racial motive in District 12’s design was an inference the

plaintiffs asked the court to draw from the district’s shape and

racial demographics.” This evidence was legally insufficient to

sustain plaintiffs’ burden on summary judgment. While District

12 is admittedly less compact than the State’s other districts, it

covers a significantly smaller radius than the State’s earlier

plan, is contiguous and roughly equal throughout in length, and

it does not rely on artificial devices such as cross-overs and

double cross-overs to achieve that contiguity. See JS at 36a

(Ervin, J., dissenting) (citing Affidavit of Dr. Gerald R.

Webster). Of the 12 districts in the 1997 plan, it “has the third

25 Plaintiffs presented various maps and demographic data, as well as

the affidavits of several experts who relied on the same evidence of shape

and racial demographicsto opine that race was the predominant factor used

by the State to draw the boundaries of the congressionaldistricts. See, e.g.,

Declaration of Dr. Ronald E. Weber JA at 219-20. But as this Court has

explained in another context, “the postenactment testimony of outside

experts is of little use” in determining the legislature’s purpose in enacting

a particular statute, when none of those experts “participated. in or

contributed to the enactment of the law or its implementation.” Edwards

v. Aguillard, 482 U.S. 578, 595-96 (1986).

23

shortest travel time (1.67 hours) and the third shortest distance

(95 miles) between its farthest points.” JS at 105a.

Equally as important, unlike in Bush, Miller or Shaw II, the

record itself is devoid of any support for plaintiffs’ assertion

that race was the overarching motivation for the district’s

design. District 12 was not the product of the Department of

Justice’s invalid “black maximization” policy. There were no

concessions of racial motivations by the state defendants; there

were no race-based admissions in the myriad of indicators

traditionally used to glean legislative intent - the plain language

of the legislation, the committee hearings, the committee

reports, the floor debates, the State’s § 5 submissions - and

there. were no acknowledgments in the post-enactment

statements of those who participated in the drafting or

enactment of the plan that race was a motivating factor. See JS

at 33a (Ervin, J., dissenting) (“Plaintiffs’ have proffered neither

direct nor circumstantial evidence that the General Assembly

was pressured by the Department of Justice to maximize

minority participation when it redrew the congressional

districts in 1997.”). Because plaintiffs’ showing that race was

the predominant factor in the design of District 12 was

deficient, they were not entitled to summary judgment.

24

Defendants’ Direct Evidence Clearly

Established That Non-Racial Goals Were The

Predominant Factor In The Design Of

District 12. This Evidence Was Sufficient Not

Only To Defeat Plaintiffs’ Motion But To

Obtain Summary Judgment For Defendants.

Far from supporting plaintiffs’ position, the record contains

substantial evidence that race was anything but a predominant

factor in the design of District 12. The district court’s decision

thus warrants reversal not only because it sided improperly

with plaintiffs but because it should have granted defendants’

cross-motion for summary judgment.

The North Carolina legislature, exercising the state’s right |

to design its own congressional districts, selected a number of

traditional - and race-neutral - districting criteria to be used in

constructing the 1997 plan: contiguity, respect for political

subdivisions, respect for voters’ needs and interests,

preservation of the partisan balance in the State’s congressional

delegation, avoidance of contests between incumbents, and, to

the extent possible while curing the constitutional defects in the

prior plan, preservation of the cores of prior districts. JS at 73a-

74a, 8la. The Court previously has found use of such

districting criteria entirely legitimate.

26 This Court has held that a state may draw district lines to allocate

seats proportionately to major political parties. See Gaffney v. Cummings,

412 U.S. 735, 751-54 (1973); see also Bush, 517 U.S. at 963-64, (opinion

of O'Connor, J., joined by Rehnquist, C.J. and Kennedy, J). This Court also

has held that both preserving the cores of prior districts and avoiding

contests between incumbents are legitimate state districting goals. See

25

The State’s lawful, non-racial motivations were confirmed

by affidavits from the legislators who headed the legislative

committees that drew the 1997 plan and shepherded it through

the General Assembly. These legislators testified under oath

that they and their colleagues were well aware, when they

designed and enacted the 1997 plan, of the constitutional

limitations imposed by this Court’s decisions in Shaw and its

progeny, and that they therefore took pains to ensure that race

was not the predominant - or even a significant - factor in the

design of any of its districts. Rather, the legislature’s

overarching goal was preservation of the six-to-six Democratic

and Republican electoral balance. Maintenance of the existing

electoral balance was essential to gain passage of any new

redistricting plan since the Senate was Democratic-controlled

and the House was dominated by Republicans. See JS at 70a-

72a, 81a. As Senator Cooper stated, “I knew that any plan

which gave an advantage to Democrats faced certain defeat in

the House while any plan which gave an advantage to

Republicans faced certain defeat in the Senate.” JS at 73a.

“Preserving the existing partisan balance, therefore, was the

only means by which the General Assembly could enact a plan

as required by the Court.” Id. See also JS at 37a (Ervin, J.,

dissenting) (noting that District 12 had to be drawn to protect

incumbents).

Karcher v. Daggett, 462 U.S. 725, 740 (1983); White v. Weiser, 412 U.S.

783, 791, 797 (1973); Burns v. Richardson, 384 U.S. 73, 89 n.16 (1966);

see also Bush, 517 U.S. at 964 (opinion of O’Connor, J., joined by

Rehnquist, C.J. and Kennedy, J).

26

At the summary judgment stage, the district court was

obligated to accept this testimony as truthful. See Liberty

Lobby, 477 U.S. at 255 (“The evidence of the non-movant is to

be believed, and all justifiable inferences are to be drawn in his

favor”). But instead the court did precisely the opposite - it

assumed that these North Carolina legislators had lied under

oath in order to hide a racial agenda.” In so doing, the court

only compounded its errors. As this Court has held repeatedly,

courts may not blithely attribute unconstitutional motivations

to state legislators. See Miller, 515 U.S. at 915-16; Mueller v.

Allen, 463 U.S. 388, 394 (1983).% This Court has made clear

that these cautionary principles are fully applicable in Shaw

cases. Miller, 515 U.S. at 915 (“Although race-based

decisionmaking is inherently suspect, until a claimant makes a

showing sufficient to support that allegation the good faith of

a state legislature must be presumed.” (citation omitted)); id. at

27 That the finder of fact at trial would be the three-judge panel, rather

than a jury, does not excuse the court’s failure to credit this testimony. Even

in a non-jury case, a court ruling on a motion for summary judgment is

obligated to accept the testimony of the nonmoving party’s witnesses as

true. See, e.g., Nunez v. Superior Oil Co., 572 F.2d 1119, 1123-25 (CAS

1978); Borden, Inc. v. Spoor, Behrins, Campbell, Young, Inc., 828 F. Supp.

216, 218-19 (S.D.N.Y. 1993).

28 When a federal court is called upon to judge the constitutionality of

an act of a state legislature, it must “presume” that the legislature “act[ed]

in a constitutionalmanner,” Illinois v. Krull, 480 U.S. 340, 351 (1987); see

McDonald v. Board of Election Comm'rs of Chicago, 394 U.S. 802, 809

(1969), and remember that it ““is not exercising a primary judgment but is

sitting in judgment upon those who also have taken the oath to observe the

Constitution.” Rostkerv. Goldberg, 453 U.S. 57, 64 (1981) (quoting Joint

Anti-Fascist Refugee Comm. v. McGrath, 341 U.S. 123, 164 (1951)

(Frankfurter, J., concurring)).

27

916 (courts adjudicating Shaw claims are obligated to accord

the challenged plan “the presumption of good faith that must be

accorded [all] legislative enactments”).Indeed, the presumption

of legislative good faith has even greater force in redistricting

cases, given the “sensitive” and highly political nature of the

redistricting process and the “serious intrusion” on state

political judgments that federal court review of state districting

legislation entails. See id. at 916 (admonishing lower courts “to

exercise extraordinary caution in adjudicating claims that a

State has drawn district lines on the basis of race” (emphasis

added)); id. at 916-17 (directing courts to bear in mind the

demanding nature of “the plaintiff's burden of proof at trial”

and “the intrusive potential of judicial intervention into the

legislative realm” when assessing the adequacy of a plaintiff's

showing at the summary judgment stage).”

» Precisely for these reasons, lower federal courts entertaining Shaw

claims have consistently refused to resolve the “predominance” issue

without a full evidentiary hearing, except in cases where the defendants

have conceded it. Indeed, the decision below is one of only two reported

decisions in which a contested issue of “predominance” has been resolved

in the plaintiffs’ favor on summary judgment. The other, that of the three-

judge panel in Johnson v. Mortham, 915 F. Supp. 1529 (N.D. Fla. 1995),

also drew a vigorous dissent. See id. at 1560, 1563-68 (Hatchett, Circuit

Judge, dissenting) (calling it “grave error” to resolve the “predominance”

issue in plaintiffs’ favor on summary judgment, given the “complex and

important” nature of the case and Miller's “directive” to use “extraordinary

caution in adjudicating claims that a state has drawn district lines on the

basis of race’) (emphasis in original)). The error committed here was even

graver, for the plan being challenged in Johnson had been drawn by a court,

rather than a legislature, making the “predominance” issue considerably less

difficult than it is here - and the need for deference less pressing than that

owed by a federal court to a state legislative branch.

28

In short, there was simply no justification for the district

court to ignore this Court’s directives and grant plaintiffs,

rather than defendants, summary judgment. That it did so on

such a weak showing - based on imputed motives and without

full evidentiary hearing - is even less defensible. The decision

should be overturned.

II. THE DISTRICT COURT WRONGLY DENIED THE

STATE’S CROSS-MOTION FOR SUMMARY

JUDGMENT BECAUSE THE STATE PRESENTED

SUBSTANTIAL AND CREDIBLE EVIDENCE THAT

DISTRICT 12°S SHAPE AND RACIAL

DEMOGRAPHICS WERE THE RESULT OF

LEGITIMATE, NON-RACIAL, POLITICAL

MOTIVES.

Although partisan voting preferences determined the

boundaries of District 12, the district court condemned the

district on the basis of party registration data not relied on by

the legislature. The district court’s conclusion that race was the

predominant factor is flawed because the court failed to

distinguish between plaintiffs’ irrelevant partisan registration

figures and the actual partisan voting preferences demonstrated

by voting results - the information in fact used by Senator

Cooper and Representative McMahan in the redistricting

process. This error was compounded by the court’s rejection of

a statistically reliable and systematic analysis of the district as

a whole in favor of picking and choosing a few isolated

examples from around the district. Because of these errors, the

court failed to recognize the plaintiffs’ utter failure of proof on

their required burden to demonstrate predominance of racial

29

motivation, and hence, that summary judgment should have

been granted to the State.

To the extent the shape of District 12 is somewhat irregular

and its boundaries correlate with race, the plan’s architects,

Senator Cooper and Representative McMahan, testified that

partisan election considerations, and not race, explain these

results. JS at 69a-84a. Their testimony is confirmed by the

extensive statistical analysis from Dr. David Peterson.?® The

district court failed to address Dr. Peterson’s study, but instead,

relied on maps supplied by plaintiffs from three of the six

counties in the district. The district court focused on a handful

of precincts that border District 12, but were not included in the

district despite having Democratic voter-registration

majorities, even though the registered Democrats in these

districts consistently voted Republican. Because the court

failed to require the plaintiffs to meet head-on the state

defendants’ contemporaneous and documented explanation for

the district they drew, the court wrongly concluded that race,

not partisanship, must have accounted for the design of District

12 and wrongly denied summary judgment to the State.

30 -Dr. Peterson in his analysis traveled along the boundaries of the

districts, comparing each precinct included in District 12 with each

corresponding excluded precinct that adjoined District 12. From these

comparisons, Dr. Peterson concluded that partisan explanations were “at

least as strong” and “somewhat stronger’ than racial ones in accounting for

the District’s design. JS at 98a.

30

A. THE STATE’S RELIANCE ON VOTING BEHAVIOR

DOES NOT TRIGGER STRICT SCRUTINY.

This Court has upheld the use of partisan election results in

the drawing of district lines so long as race is not used as a

proxy for voting preferences. In Bush, a majority of this Court

made clear that a district is not subject to strict scrutiny simply

because there is some correlation between its lines and racial

demographics, if the evidence establishes that those lines were

in fact drawn on the basis of political voting preference, rather

than race. See 517 U.S. at 968 (opinion of O’Connor, J., joined

by Rehnquist, C.J. and Kennedy, J.) (“If district lines merely

correlate with race because they are drawn on the basis of

political affiliation, which correlates with race, there is no

racial classification to justify, just as racial disproportions in

the level of prosecutions for a particular crime may be

unobjectionable if they merely reflect racial disproportions in

the commission of that crime.”); id. at 1027-29 (Stevens, J.,

joined by Ginsburg and Breyer, JJ., dissenting); id. at 1059-60

(Souter, J., joined by Ginsburg and Breyer, JJ., dissenting). _

Contrary to the. district court’s suggestion, this is not a

situation like that in Bush, where the state has used race “as a

proxy for political characteristics” in its political

gerrymandering.®! See JS at 22a, n.7 (citing Bush, 517 U.S. at

3! By contrast, the undisputed evidence here established that the racial

data available to the North Carolina legislature was no more detailed than

the other demographic data it used: racial demographics, voter registration

and election results. All are reported at the precinct level. Compare Bush,

517 U.S. at 961-67, 969-70, 975 (plur. op.) (finding legislature’s use of

racial data that was significantly more detailed than its data on other voter

eo]

968 (plur. op.). Instead, the undisputed evidence in the record

showed that the State used political characteristics, as

represented by actual election results, not racial data, to draw

the lines. Bush specifically stated, that the legislature’s use of -

such “political data” to accomplish otherwise legitimate

“political gerrymandering” will not subject the resulting district

to strict scrutiny, “regardless of its awareness of its racial

implications and regardless of the fact that it does so in the

context of a majority-minority district.” 517 U.S. at 968 (plur.

op.); see id. at 1027-29 (Stevens, J., joined by Ginsburg and

Breyer, JJ., dissenting); id. at 1059-60 (Souter, J., joined by

Ginsburg and Breyer, JJ., dissenting). In this case, legitimate

the use of political data to design District 12 - which did not

result in a majority-minority district - does not trigger strict

scrutiny and there is no racial classification to justify.

B. THE DISPARITY BETWEEN PARTY REGISTRATION

AND VOTING BEHAVIOR IN NORTH CAROLINA

EXPLAINS THE SHAPE AND RACIAL DEMOGRAPHICS

OF DISTRICT 12.

The district court’s analysis of District 12 completely failed

to take into account that voters in North Carolina often do not

vote in accordance with their party affiliation. The affidavits

in the record state that in predicting the partisan voting patterns

of various precincts, the legislature did not rely on voter

registration data but, rather, employed the far more meaningful

and reliable method of actual election results. As Senator

demographicsto be convincing circumstantial evidence that race had been

its predominant consideration in designing the challenged districts).

32

Cooper’s stated, “election results were the principal factor

which determined the location and configuration of all districts

in Plan A [the Plan at issue here] so that a partisan balance

which could pass the General Assembly could be achieved.”3?

The district court did not address the State’s affidavits directly.

Instead, relying on plaintiffs’ maps, the court focused on a few

precincts with Democratic majority voter registration rates that

bordered District 12 but were not included in the district. Based

on these isolated examples, the court concluded that the

“uncontroverted material facts” demonstrate that District 12

was drawn based on racial identification, rather than political

identification, because some Democratic majority precincts

were bypassed in drawing the district. JS at 21a. But party

registration data was precisely what the legislature chose not to

use in constructing its districts, since such data was less reliable

than actual voting histories in guaranteeing specific partisan

outcomes.

32 JA 73a. Representative McMahan'’s affidavit states: “The means I

used to check on the partisan nature of proposed new districts was the

election results in the General Assembly’s computer data base (the 1990

Helms-Gantt election and the 1988 elections for Lieutenant Governor and

one of the Court of Appeals seats).” JA 81a-82a.

Even on the present record, the registration maps relied on by the

court demonstrate that, with only very rare exceptions, the excluded

precincts consistently have Democratic voter registration below 60%, while

the adjoining precincts included in the district consistently have higher

Democratic voter registration ranging from 60% to over 90%. On the rare

occasions when a precinct within the district is between 50% and 60% in

Democratic registration, the Democratic registration for each such district

consistently is higher than that for its adjoining excluded precinct. See

McGee Aff. (CD 61), Exs. N, O and P, lodged with the Court.

33

Far from this being a minor technical matter, the use of

actual voting patterns rather than registration rates is highly

probative on how precincts actually vote and hence which ones

are genuinely safe Democratic precincts.* In North Carolina,

many voters who have long been registered as Democrats vote

Republicanin national or statewide races.>’ In North Carolina,

voter registrationis obviously not a reliable indicator of actual

voting patterns.

* Not until its memorandum opinion was filed did the court indicate

its misunderstanding of the relevance of registration data. If given the

opportunity to address the court’s concern, the defendants would have

provided the far more probative election results for the excluded precincts

highlighted by the court. The majority of these precincts show dominant

Republican voting majorities.

As of 1990, 65% of the State’s voters were registered as Democrats HE fy

and 30% as Republicans. Yet in the 1988 Presidential election, George fe FE

Bush received 58% of the vote compared to Michael Dukakis’ 42%; in |

1992, George Bush and Bill Clinton each received 43%. Since 1992, the

State has had two Republican Senators. See The Almanac -of American

Politics 1990, 1994 and 1996. (The demographic and registration data

available on the State’s redistricting computer is based on 1990

information.)

3 If voter registration were a reliable measure of partisan preference,

then the Republican-controlledState House would never have agreed to the

redistricting plan. Based on registration figures, 10 of 12 districts have

Democratic majorities in registration and an eleventh district has a

Democratic plurality (49.32% Democratic to 43.81% Republican). There

is one Republican district, but only with a plurality in registration (46.80%

Republican to 46.55% Democratic). JA at 105-07. District 12 itself

demonstratesthe often significant disparity between registration and voting

patterns: the District has a 75% Democratic registration, but only a 62%

Democratic preference in election results. JS at 99a.

ER

kd

Bs

Re

Pi

XY

wf

os

ei

Eon

i

Ya A

: 6

: 3

. 3

Ri

I

a

fo

. |

i

si

f

i

h

a

A

5

4

E

L

T

e

e

I

A

A

C

A

A

S

S

T

A

S

S

d

S

e

E

L

R

S

P

a

r

r

p

e

e

r

to

e

34

Seeking to generate a congressional districting plan that

would as a whole preserve the existing partisan balance, and

seeking to make District 12 a Democratic district as part of this

plan, the legislature for understandable reasons did not rely on

voter registration rates, but on actual election data - as the two

key political actors, Senator Cooper and Representative

McMahan, testified in their affidavits. The magnitude of the

court’s error in failing to consider the proper criteria in its equal

protection analysis warrants reversal of the court’s decision.

CC... TO DETERMINE THE LEGISLATURE’S

PREDOMINANT MOTIVATION IN DESIGNING A

DISTRICT, THE COURT MUST CONSIDER THE

DISTRICT AS A WHOLE.

The court’s analysis was deficient in other key respects. In

weighing the evidence before it, the court both examined the

wrong criteria and focused on isolated precincts, rather than

reviewing the design of the district as a whole. Had the court

conducted the complex predominant motive inquiry properly,

it could not have justified a grant of summary judgment to

plaintiffs. The court also did not take into account the

statistically sound and comprehensive analysis of District 12

made by Dr. Peterson. The results of this report should have,

at a minimum, raised a genuine issue of material fact and more

likely, helped establish defendants’ entitlement to summary

judgment.

Judicial inquiry into the design of a congressional district

is a complex and demanding task. In the legislative districting

context, partisan actors must make decisions about the general

33

location of the various districts in the plan as a whole. These

are strongly interlocking decisions, of course, because for

partisan purposes, what matters is not any district in isolation,

but the predicted partisan effects of the plan as an entirety. See,

e.g., Davis v. Bandemer, 478 U.S. 109, 145 (1986) (O’Connor,

J., concurring in the judgment) (“The opportunity to control the

drawing of electoral boundaries through the legislative process

of apportionment is a critical and traditional part of politics in

the United States, and one that plays no small role in fostering

active participation in the political parties at every level.”).

This is the general, complex context against which courts

must adjudicate the role of race - and in particular, whether race

predominated. In this case, the district court failed to apply the

“predominant motive” standard in a manner that systematically

analyzed District 12 as a whole. District 12 contains 155

precincts. Yet, the district court focused on three of the six

included counties, and concentrated on only 32 excluded

precincts with Democratic voter-registration majorities. Based

“on its isolation of these particular precincts, the district court

wrongly concluded that the district as a whole had been drawn

with a predominantly racial purpose. Thus, even if the court

had not misunderstoodthe difference between voter registration

data and actual election results, its approach to applying Shaw -

by picking and choosing selected features of a district, rather

than examining the district as a whole - was fatally flawed.

There are likely a number of techniques through which

lower courts statistically could analyze the predominant

redistricting motivation for a district as a whole. Here the State

offered one such approach. The State submitted an extensive

Ss

R

A

AI

Sr

an

a

a

e

E

R

A

S

CI

Ch

P

e

e

s

A

2 E

R

E

EN

A

T

E

F

E

E

e

Sd

ri

nd

CE

C

o

t

a

e

e

R

a

Os

L

E

a

s

S

A

L

E

e

T

S

R

EA

R

e

A

a

P

p

2

A

A

E

H

S

o

h

o

Lt

36

statistical analysis from an expert statistician that did not

isolate a small number of precincts, but instead

comprehensively examined all of District 12 and its

surrounding territory. Dr. Peterson concluded that racial

considerations did not predominate in the drawing of District

12. JS at 87, 98a. This statistical analysis, along with the

testimony of the legislators, should have been enough to enable

the State not only to defeat plaintiffs’ motion for summary

judgment, but also to obtain judgment in its favor. This is not

to say that this statistical analysis is the only means of bringing

more than anecdotal perspectives to bear on applying the

predominant motive test. But this method of analysis does

provide at least one way lower courts, as well as redistricters

seeking to comply in good faith with Shaw, can gain more

concrete guidance into how to assess whether the predominant

motive for a district or districting plan rests on constitutional

permissible considerations.

The point of such method is to offer a more reliable means

than intuitive, ad hoc, and necessarily subjective approaches to