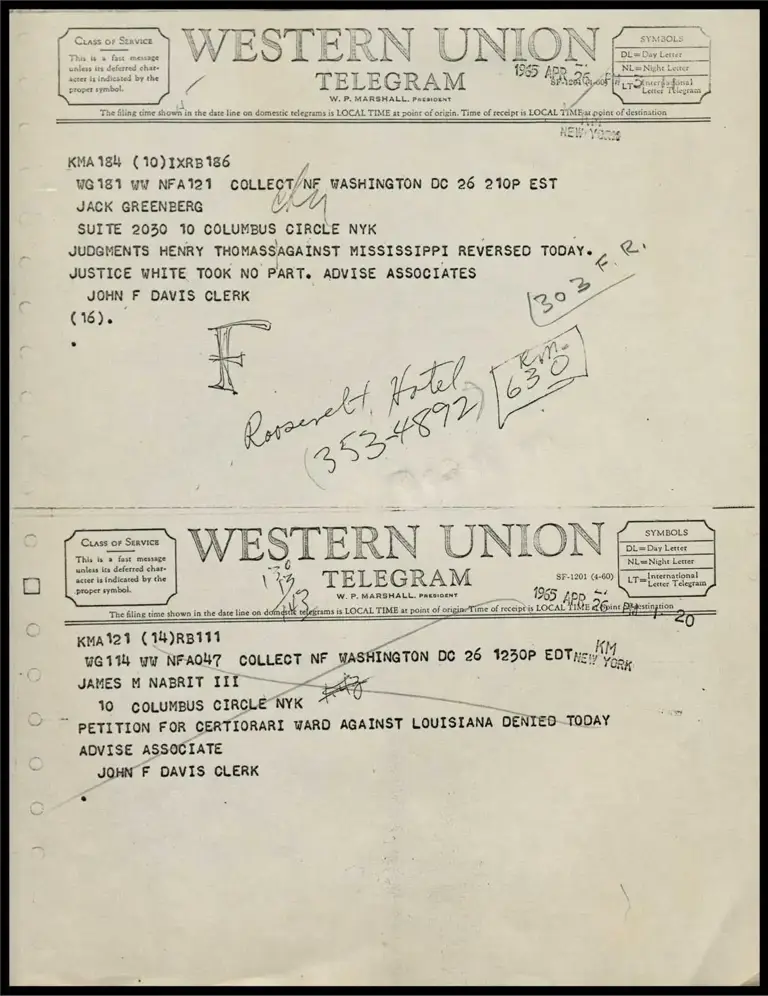

Telegram: Jack Greenberg to John F. David Clerk

Press Release

April 26, 1965

Cite this item

-

Press Releases, Loose Pages. Telegram: Jack Greenberg to John F. David Clerk, 1965. 98dff5e4-bd92-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/7a5d8d79-9508-4139-ac37-68bbfa28b458/telegram-jack-greenberg-to-john-f-david-clerk. Accessed March 05, 2026.

Copied!

KMA184 (10)1xXRB186

WG181 ww NFA121 COLLEGT/NF WASHINGTON DC 26 210P EST

JACK GREENBERG UY

SUITE 2030 10 COLUMBUS CIRCLE NYK

JUDGMENTS HENRY THOMASSAGAINST MISSISSIPPI REVERSED TODAY. , @'‘

JUSTICE WHITE TOOK NO PART. ADVISE ASSOCIATES M Bs

JOHN F DAVIS CLERK a2 02 sii

(16). = ee A

(ln BE

ed eee”

WESTE RN UNI ON

(i TELEGRAM 1065 W.P, MARSHALL. pnseioenr 1955

‘The filing time shown in the date line on d

pp) St =

hadk telegrams is LOCAL TIME at point of origine'Time of receipts ook Hike 2 2G ins Bi singtion

KMai21 (14)RB191

WG114 wy NFAOS7 COLLECT NF WASHINGTON DC 26 1250P EDTy,

JAMES M NABRIT IIT <a

10 COLUMBUS CIRCLE NYK

~ PETITION FOR CERTIORARI WARD AGAINST LOUISIANA DENIED TODAY

ADVISE ASSOCIATE

JOHN F DAVIS CLERK

‘Crass oF Service

hare

acter is indicated by the

proper symbol.