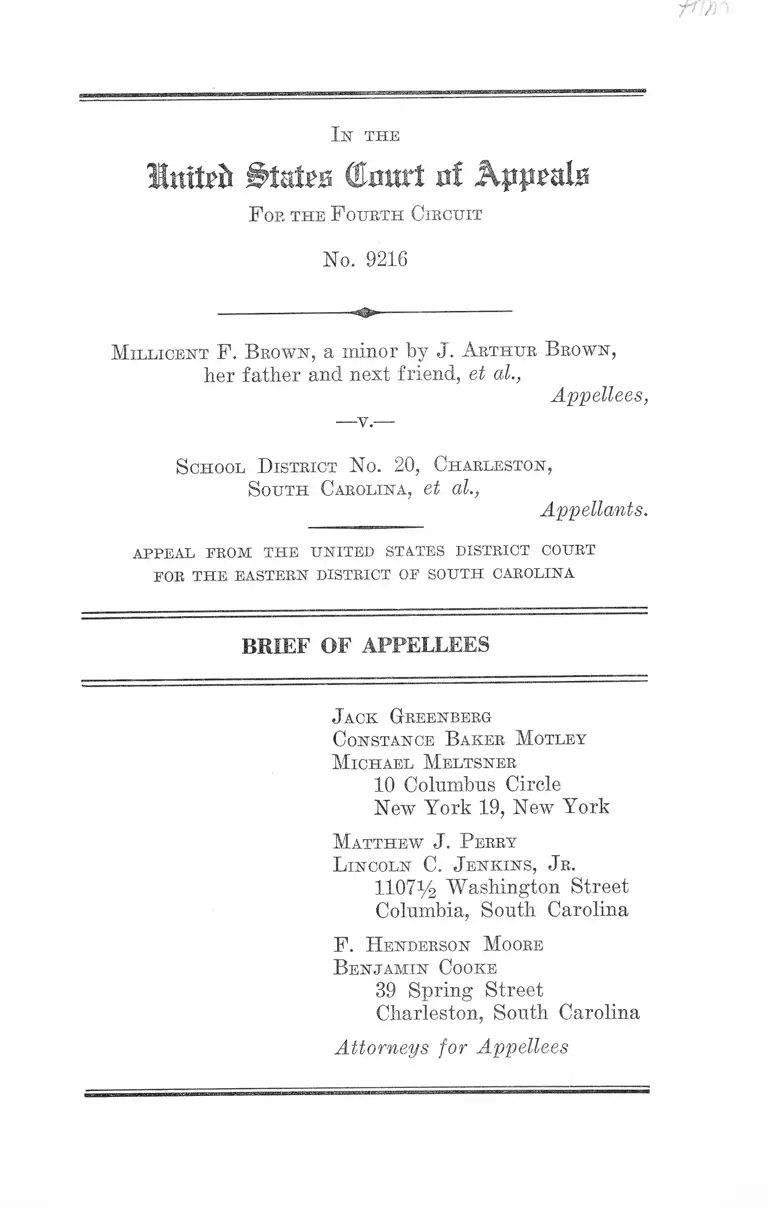

Brown v. School District No. 20, Charleston South Carolina Brief of Appellees

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1963

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Brown v. School District No. 20, Charleston South Carolina Brief of Appellees, 1963. 1e756cc9-b69a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/7a852fe1-0aae-4d63-9609-26496316959e/brown-v-school-district-no-20-charleston-south-carolina-brief-of-appellees. Accessed February 08, 2026.

Copied!

I n th e

Intfrii BUim Olmtrt of Kppmlz

F oe the F ourth Circuit

No. 9216

M illicent F. Brown, a minor by J. A rthur B rown,

her father and next friend, et at.,

Appellees,

— v .—

S chool D istrict No. 20, Charleston,

South Carolina, et al.,

Appellants.

APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF SOUTH CAROLINA

BRIEF OF APPELLEES

Jack Greenberg

Constance Baker M otley

M ichael M eltsner

10 Colnmbns Circle

New York 19, New York

Matthew J. Perry

L incoln C. Jenkins, Jr.

1107V2 Washington Street

Columbia, South Carolina

F. H enderson M oore

B enjamin Cooke

39 Spring Street

Charleston, South Carolina

Attorneys for Appellees

I N D E X

PAGE

Statement of Facts .......................................................... 1

A rgument .............................-....................................................... 5

The District Court Properly Enjoined Operation

of the Public School System of Charleston, South

Carolina on a Racially Segregated Basis and

Ordered Admission of Appellees to Formerly All-

White Schools ............................................................ 5

Conclusion ...................... ............................................................ 13

T able oe Cases

Armstrong v. Board of Ed. of City of Birmingham,

323 F. 2d 333 (5th Cir. 1963) ..................................... 8

Bradley v. School Board of City of Richmond, 317

F. 2d 429 (4th Cir. 1963) ............................................ 7, 8

Briggs v. Elliott, 132 F. Supp. 776 (E. D. S. C. 1955) .... 2

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483, 349 U. S.

294 ..................................... ........ -................................2,6,11

<KBush y. Orleans Parish School Board, 308 F. 2d 491

(5th Cir. 1962) ................ ............. ........ .... - - - .......... 7

Carson v. Warlick, 238 F. 2d 724 (4th Cir. 1956) ....... 7

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1 ................... ....................... 6,11

Gibson v. Board of Education of Dade County, 246

F. 2d 913 (5th Cir. 1958) ............................................ 7

Goss v. School Board of City of Knoxville, 373 U. S.

683 .................................................................................. 5

Green v. School Board of City of Roanoke, 304 F. 2d

118 (4th Cir. 1962) ........................................................ 7, 8

11

PAGE

Hamm v. County School Board of Arlington, 263 F. 2d

226 (4th Cir. 1959) ........................................................ 9

Jackson v. School Board of Lynchburg, 321 F. 2d 230

(4th Cir. 1963) ............................................................. <3? 11

Jeffers v. Whitley, 309 F. 2d 621 (4th Cir. 1962) .........7,11

Johnson v. Virginia, 373 U. S. 61 ................................. 12

Jones v. School Board of City of Alexandria, 278 F.

2d 72 (4th Cir. 1960) .................................................7, 8, 9

McNeese v. Board of Education, 373 U. S. 668 .......... 6, 7, 8

Marsh v. County School Board of Roanoke County, Va.,

305 F. 2d 94 (4th Cir. 1962) ..................................... 7

Northcross v. Board of Education of the City of Mem

phis, 302 F. 2d 818 (6th Cir. 1963) ......... .......... .......... 7

Norwood v. Tucker, 287 F. 2d 798 (8th Cir. 1961) .... 9

Stell v. Savannah-Chatham County Board of Educa

tion, 318 F. 2d 425 (5th Cir. 1963) ............................. 12

Watson v. City of Memphis, 373 IT. S. 526 .................. 5, 6

Wheeler v. Durham City Board of Education, 309 F.

2d 621 (4th Cir. 1962) ...................................... .......... 7

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions

S. C. Code (1962) §21-751 ................... ................. ......... 2

S. C. Code (1962) §§21-247 et seq.................................. 4, 6

S. C. Const. 1895, Art. II, §7 ......................................... 2

I n th e

lutteft (Emtrt ni Kppmlz

F oe the F ourth Circuit

No. 9216

M illicent F. Brown, a minor by J. A rthur Brown,

her father and next friend, et al.,

Appellees,

—v.-

S chool D istrict N o. 20, Charleston,

South Carolina, et al.,

Appellants.

APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF SOUTH CAROLINA

BRIEF OF APPELLEES

Statement of Facts

Appellees wish to call to the attention of the Court cer

tain facts not found in the Statement in appellants’ Brief.

The total population of School District No. 20, Charleston,

South Carolina, is 65,925, of which 32,313 persons, or 49%,

are white and 33,612, or 51%, are Negro (93).* 12,647 pupils

were enrolled for the 1962-63 school year (93). 3,108 pupils,

or 24% %, were white and attended six schools (55, 93).

9,539 pupils, or 74%%, were Negro and attended nine

schools (55, 93). The School Board employs 420 teachers,

134 are white and 286 are Negro (94). Prior to the order

Citations are to the Appendix to Appellants’ Brief.

2

of the district court which the School Board appeals here,

no child of one race attended school with children of the

other race (51, 55) and no teacher of one race taught

children of the other race (75).

The record clearly reveals that the School Board operates

a dual school system based on race. Prior to the decision

of the United States Supreme Court in Brown v. Board

of Education, 347 U. S. 495, school segregation was required

by law in South Carolina, S. C. Const. 1895, Art. II, §7;

§21-751 S. C. Code (1962). These provisions were declared

unconstitutional in Briggs v. Elliott, 132 F. Supp. 776, 778

(E. D. S. C. 1955), hut the School Board has neither taken

any action to desegregate the schools nor indicated an

intention to do so in the future (74, 85, 88). The Chairman

of the School Board testified that no action had been taken

by the Board and that none was contemplated (85). The

Superintendent of Schools has never been authorized to

accept Negro pupils or teachers in white schools (74, 75).

The Board has never announced or notified parents that

enrollment, assignment, or transfer is available without

regard to race (49, 52). Desegregation has not even been

discussed with the Negro supervisor of Negro schools (88),

who testified that he administers “an entirely separate”

school system within a system (88).

Overlapping attendance areas or zones are employed to

assign children to the schools. White children live in the

zones of Negro schools hut attend white schools; Negro

children live in the zones of white schools but attend all-

Negro schools (77-82). Negroes graduating from ele

mentary schools “ feed” to Negro high schools and whites

to white high schools (41, 42, 51, 55, 81). White teachers

are assigned to white schools; Negro teachers to Negro

schools (75). Negro pupils are scattered throughout the

3

school district but they all attend the nine all-Negro schools

(80, 82).

When a white elementary school (Mitchell) was closed

recently, all its former pupils living on one side of a line

bisecting School District No. 20 were by direction of the

Superintendent assigned to one of the other two white

elementary schools and all former pupils living on the other

side of the line were assigned to the other white elementary

school (83, 80, 82, 52).

Forty-six Negro parents, including the parents of some

of the appellees, filed a petition with the School Board in

1955 requesting the Board initiate desegregation (72, 73).

The Board replied that “it is not practical or advisable to

do this at this time” (74).

In 1960, Negro school children and their parents, includ

ing most of the appellees, applied to the Board for transfer

to white schools (251), but the applications were denied

(and on appeal to the County Board of Education (252-254)

denial of transfer was affirmed (257, 258)) on the ground

that the applications were not filed four months prior to

the opening of school (252).

In 1961, appellees and several other Negro children ap

plied to the School Board for transfer to white schools

(259). Ail these applications were denied by the Board

as not in the “best interests” of the pupil (260-267). It

was not in appellee Brown’s “best interests” to be trans

ferred because she was “well adjusted” and “ popular” at

the school she attended (263-64). On the other hand, the

Board concluded Clarissa Karen Hines should be denied

transfer because she was a “ timid, introverted child” (266-

67). Appellee Clover’s application was denied on the

ground that the Negro school she attended was superior

4

to the white school to which she desired transfer (275).

Four of the appellees appealed to the County Board of

Education where the denials were affirmed (271-73).

The record is clear that only Negro children seeking

transfer to white schools have ever been required to use

the transfer procedure set out by the S. C. Code §§21-247

et seq. and the rules of the Board (40-41). As the Super

intendent put it, “ These rules and administrative proce

dures . . . were developed to handle requests . . . where

Negro children requested transfers to white schools” (141).

School children are not assigned by the Board on the basis

of academic qualifications, test scores, adjustment or their

“best interests” (126, 141). Aside from these Negro ap

pellees, the School Board assigns children to school by

means of dual school attendance areas (77-83, 140, 141).

The record reveals substantial inferiorities in the Negro

schools. For the school year ending in 1962, the Board

spent $267.11 for each white child and only $169.75 for each

Negro child (54, 129). White teachers must score 500 on

the National Teachers Examination; Negro teachers are

employed if they score 425 (131). Despite the fact that

sufficient numbers of Negro teachers scoring 500 could not

be found, white teachers were not assigned to Negro schools

(132). The pupil-teacher ratio is significantly lower in the

white schools. Negro schools do not offer many courses

taught at the white schools such as refrigeration, wood

working, machine shop, drafting, and four years of Latin.1

1 See Plaintiffs’ Exhibits 16-21 (243-44) which have not been

printed in the appendix to appellants’ Brief.

5

A R G U M E N T

The District Court Properly Enjoined Operation of

the Public School System of Charleston, South Carolina

on a Racially Segregated Basis and Ordered Admission

of Appellees to Formerly All-White Schools.

This is another of the now familiar public school de

segregation cases to reach this court since Brown v. Board

of Education of Topeka. After a full trial, the District

Court issued an order, which the School Board and inter

vening white parents appeal here, providing for (292-96):

1. Admission in September, 1963 of eleven Negro school

children to the school which they would attend if they were

white;

2. Injunctive relief (to take effect with the school year

1964-65) restraining refusal to admit, assign, or transfer

Negro school children on the basis of race;

3. Procedures to be followed by the School Board (until

a desegregation plan is adopted) in disposing of requests

for non-racial assignment or transfer and notifying parents

and school children of their right to choose to attend non-

segregated schools.

The basis for this judgment is plain. The district court,

in fact, provided only minimal relief in light of the Supreme

Court’s recent admonition that “ all deliberate speed” will

not “be fully satisfied by types of plans and programs for

desegregation . . . which eight years ago might have been

deemed sufficient” Watson v. City of Memphis, 373 U. S.

526; Goss v. School Board of Knoxville, 373 U. S. 683.

6

Nine years after the decision of the Supreme Court in

the Brown case, 347 U. S. 483 (1954), the School Board had

not taken and had no plans to take any action (85) to carry

out its constitutional responsibility of “good faith compli

ance at the earliest practicable date” . Brown v. Board of

Education, 349 U. S. 294, 300, 301 (1955). Despite “ explicit

pronouncements” from this Court, Jackson v. School Board

of Lynchburg, 321 F. 2d 230 (4th Cir. 1963) and from the

Supreme Court, Watson v. City of Memphis, 373 U. S. 526,

the School Board had done nothing in the way of “ initiat

ing” desegregation and bringing about the elimination of

racial segregation in the school system under its jurisdic

tion. Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1, 4 (1958). The Board

defended on the ground that the Negro appellees had not

exhausted their administrative remedies. However, the

Board is, obviously, in no position to claim, either on the

facts or the law, McNeese v. Bd. of Education, 373 U. S.

668, that administrative remedies are adequate to secure

the constitutional rights of appellees and the class they

represent.

Four of the appellees fully complied with the adminis

trative remedies set out in S. C. Code (1962) §§21-247,

et seq., and the rules and regulations of the Board (248-50).

Faced with exhaustion of the administrative process, the

Board urges that the administrative determination of these

appellees’ constitutional rights is final. But any contention

that school children who have fully complied with a state’s

administrative remedy for seeking transfer to white schools

are barred from obtaining the relief sought here from a

federal court totally misconceives the nature of the rule

requiring exhaustion of administrative remedies. Exhaus

tion of even a nondiseriminatory administrative procedure

(and, as we will show, the procedure here is discriminatory)

is at most a prerequisite for stating a cause of action. Car

7

son v. Warlick, 238 F. 2d 724, 729 (4th Cir. 1956). The

proposition that the School Board is the final judge of

whether there is racial segregation violative of appellees’

constitutional rights is obviously groundless, McNeese v.

Bd. of Education, supra, and refuted by countless decisions

of this Court and district courts reversing administrative

determinations regarding racial segregation.

Negro school children clearly need not comply with the

administrative remedy offered by this School Board, for it

is now well settled in this Circuit that Negro students seek

ing a desegregated education need not exhaust administra

tive remedies, supplied by pupil assignment laws and pro

cedures so long as a racially segregated school system is

maintained. Marsh v. County School Board of Roanoke

County, Va., 305 F. 2d 94, 98, 99 (4th Cir. 1962); Green

v. School Board of City of Roanoke, 304 F. 2d 118, 123, 124

(4th Cir. 1962); Wheeler v. Durham City Board of Educa

tion, 309 F. 2d 630, 632, 633 (4th Cir. 1962) • Jeffers v.

Whitley, 309 F. 2d 621, 627-29 (4th Cir. 1962); Bradley v.

School Board of City of Richmond, 317 F. 2d 429, 436, 437

(4th Cir. 1963); Jones v. School Board of Alexandria, 278

F. 2d 72, 76 (4th Cir. I960).2

Appellants administer a school system where pupils of

the Negro race are completely segregated in their own

schools pursuant to their own attendance areas. “Obviously

the maintenance of a dual system of attendance areas

based on race offends the constitutional rights of the plain

2 These holdings are in accord with those of other circuits. See

Northcross v. Board of Education of the City of Memphis, 302 F.

2d 818 (6th Cir. 1963) ; Gibson v. Board of Education of Dade

County, 246 F. 2d 913 (5th Cir. 1958) ; Bush v. Orleans Parish

School Board, 308 F. 2d 491 (5th Cir. 1962).

8

tiffs and others similarly situated and cannot be tolerated.”

Jones, supra, at 278 F. 2d 72, 76 (4th Cir. 1960). Given seg

regation based on race, the South Carolina pupil assignment

laws and the rules of the Board cannot be constitutionally

applied to appellees since they establish “hurdles to which

a white child living in the same area as the Negro and hav

ing the same scholastic aptitude would not be subjected,

for he would have been initially assigned to the school to

which the Negro seeks admission,” Green, supra, at 304 F.

2d 118, 123, 124.3

These principles apply to this record with force. The

School Board’s contention that the complete segregation

which the lower court found to exist here is “voluntary” is

wholly specious. When a white elementary school was

closed, former students were assigned to other white ele

mentary schools (79, 80). One of the appellees resided

across the street from a white elementary school (80) but

her application to transfer to that school was denied (274-

76). The record is uncontradicted that all-Negro elementary

schools “ feed” all-Negro high schools; all-white elementary

schools “ feed” all-white high schools (41, 42, 81, 82).

Moreover, the Board has employed the administrative

procedures only when dealing with interracial transfers and

3 In addition to recent decisions of the Fourth Circuit holding

that Negro school children need not comply with administrative pro

cedures prior to instituting suit in the federal courts when a

school system is operated on a racially segregated basis, the United

States Supreme Court in McNeese v. Board of Education, 373

U. S. 668, has “put beyond debate the proposition that, in a school

desegregation case, it is not necessary to exhaust state administra

tive remedies before seeking relief in the federal courts,” Armstrong

v. Board of Education of City of Birmingham, 323 F. 2d 333 (5th

Cir. 1963).

9

not for initial assignment (140,141). This Court specifically

condemned use of assignment procedures for transfer and

not initial assignment in Jones v. School Board of Alex

andria, 278 F. 2d 72, 77 (4th Cir. 1960): “ Such action

would also be subject to attack on constitutional grounds,

for by reason of the existing segregation pattern, it will

be Negro children, primarily, who seek transfers.” On this

record and considering the statements of school officials,

there is “nothing to indicate a desire or intention to use the

enrollment or assignment system as a vehicle to desegre

gate the schools” Bradley v. School Board of City of Rich

mond, 317 F. 2d 429, 437 (4th Cir. 1963). When Negro par

ents petitioned for desegregation in 1955, the Board took

no action (74). Applications for transfer in 1960 were filed

“ too late” for consideration (252-58). In 1961, the applica

tions were rejected as not in the / ‘best interests” of the

children involved (259-76). The only common factor which

applied to each of the applicants was their desire to trans

fer to white schools. The denial of transfer as not in the

pupils “best interests” strongly suggests that it was de

segregation which was thought not to be in their “best in

terests” and nothing else. For example, some appellees

were denied transfer because they were well adjusted at the

segregated school which they attended (263-64) while others

were denied transfer because they were poorly adjusted

where they were and allegedly would have trouble adjusting

to a new school (266-67). Such inconsistently applied “cri

teria” do not constitute a “ legal ground for the rejection

of the . . . applications” Hamm, v. County School Board of

Arlington, 263 F. 2d 226, 228 (4th Cir. 1959); Norwood v.

Tucker, 287 F. 2d 798, 809 (8th Cir. 1961).

Given the Board’s intransigent attitude toward deseg

regation and continued maintenance of a racially segregated

school system, the district court was fully justified in find

10

ing inadequate the administrative remedy offered by the

Board.

The Board maintains that the district court had no discre

tion to provide the manner in which parents were to be

notified that their children had the right to attend a school

without regard to race. The order provides that parents

be notified that if their child is entering school for the

first time the child may be presented “ at any school serving

the child’s grade level without regard to whether the school

. . . was formerly attended solely by Negro pupils or solely

by white pupils” (294) ; or if the child seeks to transfer, he

may do so by so informing the School Board (294). The

court provided that notice of “ the right to attend a school

freely selected without regard to race” (294) should be

given to the parents at least 10 days before the end of the

1963-64 school year and again 30 days before the beginning

of the 1964-65 school year, and following school years, as

well as to children entering the system for the first time

(295).

The court explicitly provided that no particular form of

language was necessary and that “ the school authorities

may adopt such other language consistent with the purpose

of the order as they may desire” (295). The Board was

directed to apply for any reasonable modification of the

order necessary to solve administrative problems (296).

The Board complains that this portion of the order is

an attempt to take over the school system but does not

specify the manner in which notifying school children and

parents of their constitutional rights interferes with the

administration of the school system or the prerogatives of

the Board. And the Board has not applied for any modi

fication of this section of the order in the district court.

11

Under Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483, 349

U. S. 294, the District Judge has a duty to oversee the

Board’s responsibility for providing an adequate plan to

desegregate the schools. Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1, 7.

Notice of the right to attend schools without regard to race

is a necessary part of an adequate plan. Joffers v. Whitley,

309 F. 2d 621, 629 (4th Cir. 1962). The District Judge

required that parents be informed in a reasonable manner

at reasonable times of their constitutional right to a school

system operated without regard to race Jackson v. School

Board of Lynchburg, 321 F. 2d 230, 233 (4th Cir. 1963). In

fact, this Court in Jeffers v. Whitley, 309 F. 2d at 629 (4th

Cir. 1962) directed the district court to issue the order to

which the Board here objects:

The order should further provide that, if the School

Board does not adopt some other nondiscriminatory

plan, it shall inform pupils and their parents that there

is a right of free choice at the time of initial assign

ment and at such reasonable intervals thereafter as

may be determined by the Board with the approval of

the district court. How and when such information

shall be disseminated may be determined by the district

court after receiving the suggestions of the parties.

(Emphasis supplied.)

White parents and their children were permitted, over

the objection of appellees, to intervene below in order to

join the Board in presenting a factual basis for an effort to

have Brown v. Board of Education overruled. The court

permitted intervenors and the Board great latitude in in

troducing evidence for this purpose, but the court held it

was bound by decisions of this Court and the Supreme

Court with respect to the unconstitutionality of racial seg

regation (290). Intervenors and the School Board now

12

appeal to this Court claiming stare decisis does not apply

and that Brown v. Board of Education did not decide a ques

tion of law. This contention is erroneous. Plainly and

simply stated, “ . . . it is no longer open to question that

a state may not constitutionally require segregation of

public facilities.” Johnson v. Virginia, 373 U. S. 61.

The Fifth Circuit recently has had occasion to consider

the question raised here by the Board and intervenors and

summarily rejected it in Stell v. Savannah-Chatham County

Board of Education, 318 F. 2d 425, 427 (5th Cir. 1963):

The district court for the Southern District of Georgia

is bound by the decision of the United States Supreme

Court, as are we. Unless and until that Court over

rules its decision in Brown v. Topeka, no trial court

may, upon finding the existence of a segregated school

system, refrain from acting as required by the Su

preme Court merely because such district court may

conclude that the Supreme Court erred either as to its

facts or as to the law.

In short, public school segregation is foreclosed as a

litigable issue in the district court.

13

CONCLUSION

W herefore, for the foregoing reasons, appellees pray

the judgment of the court below be affirmed.

Respectfully submitted,

Jack Greenberg

Constance Baker Motley

M ichael M eltsner

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

Matthew J. Perry

L incoln C. Jenkins, J r .

1107% Washington Street

Columbia, South Carolina

F. H enderson M oore

Benjamin Cooke

39 Spring Street

Charleston, South Carolina

Attorneys for Appellees

.

38