Legal Research on Charges

Working File

January 1, 1983 - January 1, 1983

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Bozeman & Wilder Working Files. Legal Research on Charges, 1983. 2ad90437-f092-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/7a9217d0-6558-4102-829f-e902c825647c/legal-research-on-charges. Accessed February 05, 2026.

Copied!

T_

s t2-l(;-12 (lotrIt'l's

kA"Cq

s 12-1(;-l;]

slrr,r,r'rrrg []tirt pri,rr', rirrrirutl lrrot,,r,rlirrgs itg:rnrst

irrst;rrrt pl:tirrtil'l' n't.rt tt,rrrrirnrtt ri rrr lris favlr'. ir?

ALI(2rl l0ll,l.

l'lfft,ct of fitilurc or refusrtl,,f court. ilt

prosecutiort for assirult with lntelt to t:trrrrrrrit

rolrlrlr\', to instruct on assau lt arrd b:rttur1,. i-r8

A LIt2d l{oli.

Irrstructions Lo jury us to lrel dicnt or sirrrilar

nrirtlrern:rtit'al busis frrr l'ixing dlnragcs for pain

and suffering. (iU ,\l,lt2d 111i.,2.

ol'li,rrsl lrg:rinst I:rtrs rr,grrlirtirrg s:rlls ol lir;rror.

5i .,\ l.lt:',1 l:lrq2.

I )rrtl ol' tri:rl t'orrrl to irrstrrrct on sr,ll'rlr'ti,rrst',

irt :tbsence of retluest lrv accusetl. it; ALIt2d

I l7(r

lnslrtrr:Liorrs irr lrctirtrrs ltglrinsl lnotor t';rrrilr

lor irrjrtrv l-(, l):rss(,ng(.r iry sutlrlcn si,r1r1ring,

sttrting. or lurclring ol convcvirnco. ;7 r\l,lt2(l

i,

Ittstruction itr rnaliciorrs lrrost,cuLion irction of

lirrrit:rt i,,rr of lrur'p0s0 r lf (lo(,llnt(,ilt;rr.V r'\'i(lcil(:('

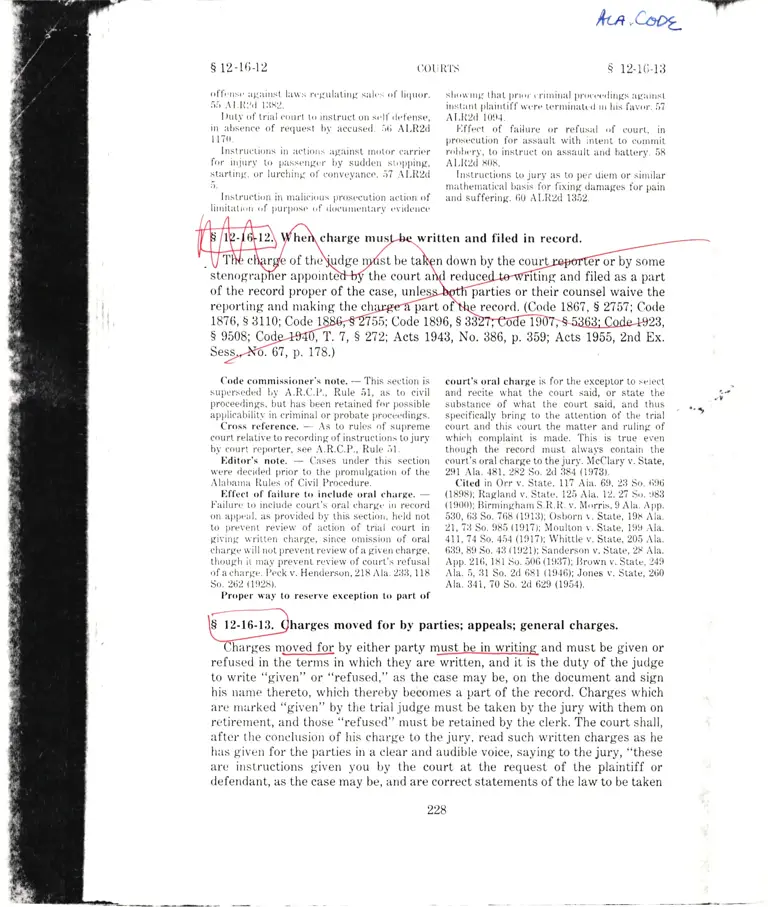

charge nrus written and filed in record.

of thei t, be ta down by the cou 0r by some

stenogralrher app0irl the eourt a I retlu ling and filed as a pi]rL

of lhe recorcl proper of the case, un larties or their counsel waive the

reportir)g and nraking the ch part o reeord. (Code 1867, $ 2757; Cotle

18?6, ti 31i0;Code LBBffi-2755; Code 1896, S

Acts, T. 7, 5 272; Acts 1943, No. 386, 1955, 2nd Ex.

Sess 67, p. 178.)

('otle commissioner's note. -']'his section is

supcrsedrrl l,v A.R.C.l'., Rule irl, as to eir.il

proceedrngs, but has been retained for pussible

applicabilitv in criminnl or ploirate [)roce(,{lings.

Cross rt,ference. -- As to rulcs of sulrreme

court relirtive to recorrling of instructions to jurl'

b1 courl l'cl)orter, see :\.R.C.P., Rule il.

Hditor's note. -

(luses under this section

n't,re rleciderl lrrior to the pronrulgirliorr of the

,\lrtlr:rrrn Itules of Civil I'rocedure.

llffect of failure to include ornl chargt'. -l"ailurt. to inclurle court's r.rral t'htrg.. irr record

orr u1r1rt,irl, irs provided by this sectiorr, ht,ld not

t() I)revent revie*'of acti()n of triirl cr.rurt in

giving uritten chirrge, since onrissiou of oral

charge w ill rrot l)revent revierv of ir giverr charge,

thr.ruglr it r))[r.y prevenL rt,r'ierv of cortrt's l'('fusal

of a t'harge. I)eck v. Henrlersr-rn, 21il ,\la. 2;];1, t lll

So.262 (11)2E).

I)roper lr'ay to reserve exc€pti(rn lo part ()f

.-------\

\S tz-to-t:1. Qha.ges moved for by parties; appeals; general charges.

\_---------

Charges nloved_tq by either party n35!_he_in_wri!lry.and musL be given or

refused in the terms in which they are written, and it is the dutv of the judge

lo write "given" or "refused," as the case may be, on the document and sign

his nirnre Lhereto, rvhich thereby becornes a part of the record. Charges which

are rnarked "given" by the trial iudge must be taken by the jury with them on

rctirerlrent, and those "refuscd" nlust be retained by the clerk. The court shall,

aftcr tl)e conelllsior) of his charge to the jurv, read such \t,r'itten charges as he

Itits given for the parties in a clear and audible voice, saying to the jury, "these

nre irrsLmctions given .you by the court at the request of the plaintiff or

defendant, as the case may be, and are correct statements of the law to be taken

court's oral charge is for Lhe exceptor to sel(.ct

and recite rvhat the court said, or state thc

substance of what the court said, and thus

specificallv bring to the attention of the trial

court and this court the nratter and ruling of

rvhiclr conrplaint is made. This is true eren

though the recortl rnust alrvavs contain the

court's ural charge to the jurv. McClary v. State,

291 Ala. .IU1, 2li2 So. 2rl 384 (11)73t.

Cited in ()rr v. St.te. l1T Ai1.6l). 2ll So. {it}(i

(1111)tl); Itagland v. State, 12;-r r\la. 12. 2? S,r. rlllil

(l{}t){)); []irnringhlrn S.ll.lt. v. Morris,9 Ala. r\1rp.

5:J0, (i;J So.7(i8 (11)1:l); ()sborn.". State, 198 r\la.

21, ?;l Sr.r.9tt5 (1917); \iloulton r. Sti.te, ll)9,\la.

411,74 So.454 (1()17); Whittle v. State,20ir Ala.

6:19,89 So.,1;t (11)21); S:rnderson v. State,28 Ala.

App. 21ti, lltl So. i06 (1!)il?); Ilrown v. State, ?4!l

Ala.5, ill So. 2rl 6111 (1{),1(i); Jones v. State,2(i0

Ala. 34i, 70 So. 2tl 629 (1954).

.1

228

t

ll'

s 12-16-13 JURIES s 12-16-13! 12-16-13

(.(l;ngs agililtst

,r his favor. S?

i of cottrt, rtt

lrrt to cotttnlit

rrrrl battcrv. ii(

Itr,trt or sitnilar

,rnirgt:s for llirirt

\'r 0r bY sollle

"lerl as a ptlrt

, rerl wairre thc

, ti 2?l-r?; (lotle

ri;t' Csds l0!'1,

191'15, 2nd Ex.

r'elrtor to seltlct

r ,,1, or stirte the

I siiitl, attrl thrts

ron of the trilrl

' r' atrd t'trling of

'i is is tttte t'r't'tt

, s eontltitt tlrt'

'lt'{.llari'v. State,

r il173).

\ r.r. (i1), 2il So. {i1)(i

.' '.r. 12. 2? So. lll{il

\lorris, 1) ,\la. r\1rp.

Stitte, l1)lt ,\la

. State, l1)9 .\lrr.

. r Statr. 21t.-r ;\lir.

r. Statt,, 28 .\l[.

l' .\'n \'. St:rte,2Jl)

. I

nes \'. StlIt('. 2(i{}

li arges.

,rst l)e givett or

.L', of t.lte jurlge

utnent and sigl)

('ltztrgcs rvhich

:r' rvith tht:t-l] otr

'i'lie court shall,

',' rtlrttrges zrs he

thr: jurY, "[lrestl

t , plirirrtiff or

'iitw to lrt'taken

by you in connection with what has already been said to you'" The refusal of

,".hqlgg,, though a correct statemenb of the iu*, .@

on app&t if it appears that the same rule of law was substantiallv and fairlv

g

"t

es must be set out in the record on appeal

in the following manner:

(1) The charge of the court;

(2) The charges given at the request of the plaintiff or the state;

(3) The charges given at the request of the defendant; and

(4) The charges refused to the appellant.

Every general charge shall be in writing or be taken down by the court reporter

.as it is tlelivered tolhe jury. (Code 1852, S 2355; Code 1867, 5 2?56; Code 1876,

5 3109; Code i886, $ 2?56; Code 1896, 5 3328; Code 190?, 5 5364; Acts 1915, No'

?16, p. 815; Code 1923, S 9509; Code 1940, T. 7,5 273.)

Crdc c,mrnissiont,r's notc. - This section is sttlrt'rst'dt'tl hy A.R.(l.l'., Itule 51, ils to civil

preces6ings, 5ut has [een retainerl for possible applicability in crinrinal or probate proceetlings.

ll

!l

rl

il Jr

lt

'li

ri

L General Consideration.

il. Olrarges to Be in \Vriting.

IIL Given or Refused as Written.

IV. I)uty to Write "Given" or "Refuserl."

V. [)art of Record.

VI. Reading of Given Charges'

Vll. Given Charges Taken bY JurY.

VIII. Instructions Already Covered.

IX. Appeal.

X. Rules of Trial Court.

I. (;ENI]RAI, CONSIDERATION.

Cross rcference. - ['or rules of supreme

court regarding request for instructions by

counsel, see A.R.C.P., Rule 51.

Flditor's note. -

('ases under this section

were decided prior to the promulgation of the

r\labanra Ilules of Civil I'rocedure.

is an indispensable part of the crime, ,h;l

defendanl is entitled, upon written requesl' to I

have the trial judge charge the jury that the /

state must prove intent (to steal or conrmit a I

felony) beyond a reasonahle doubt. Davis v.

I

State, 42 Rl". app. 3?4, 165 So. 2d 918 (196{). J

And drunkenness. - On a plea of not guilty

to crimes (such as murdcr, robbery and larcen."-)

which require a speci;rl intent, e.g., ntalice or

animus furandi. the li*v r.,f Alabama allows the

jury to consider evidence of a defendant's

irunkenne*" not for the purpost' of

acquitting hirn altogether . . . but for the purpose

of ascertaining whether or not his conrlition has

renrlered him at the time of the act capable of

harboring such special intent. However' the trial

court will not I)e l)ut in error for the failure so

to r:hargc uttltrss tlttl tlcfendant asks for an

appropriate instruction. Grossnickle v. State' 44

AIa. App. 384, 209 So. 2d iJ96 (1968).

Cited in Keeby v. State, 52 Ala. App. 31, 2it8

So. 2d 813 (19?3); Conner v. State, 52 Ala. App'

82, 289 So. 2d 650 (19?3); Morrow v. State, 52

Ala. App. 145, 290 So. 2d 209 (19?3); Williams v'

State, il Ala. App. 694, 2it8 So. 2d 753 (197a);

Culbert v. State, S2 Ata. ,tpp. 167, 290 So. 2d 235

(19?4); Marlz v. SLate, 52 Ala. App.200' 290-So'

2d 661 (19?4); Barnett v. State, 52 Ala. App. 260,

;

r

i

.l

!L-.41.

fl

,i,

Applicability of section. - In contriist to

Ilule il of the Rules r-,f Civil Procedure, this

section rt mains in full force antl effect as to

crrrngakasg$-St. John v. State, 55 Ala. App. 95,

:lXl .So. 2d 215,iert. denied,2l)4 Ala. ?68, llllJ So.

2d 2111 (19ii).

'l'inre ai which written charges must be

presented is zrny time during the trial and before

the jurv retires. Smith v. State, 51 Ala. App. 527'

2tt?'So. 2rl z:llt (ll)73), ct'rt. tle nied, 2ll2 ltla.7it\,

2tl1) So. 2rl li0lJ (1974).

Statements of law in judicial opinions are

not alwa.vs pnrper for jury instructions in other

cases. KnighLv. State, 2?:l AIa.480, i42 So. 2d

899 ( 1962).

Lilting language from an opinion and

embodying it in a written charge does not of

itself rlake it a correct instruction to the jury.

Knight v. state, 2?:J Ala. 480, 142 so. 2d t]99

(1962).

Charging proof of intent. - Because intent

229

#1*

Q 12 l(i 13 C()t,li'l's s 12-16-13 512

' the 1.

all. ll,

( l9(i2,

llf or

and

Hollir

(197tt t

Ilefr

by cr,,

reqUlr

in wrrr

556 (l

llut

err(rr i

writin

2d 2t;:

Ac,

charg'

not ir,

215 S,,

l&'lr

If ehar

legal

evider,

judgnr,

unless

..ilrrli.ur

trfeen

v. Ilel'

appt,ll

charg,

was as

it u,as

of Ml ir

by 0r,r

MeKp,

was

Holltrr.

Atr,l

charg,

then t

referer

not uir;

( 1871 ).

couplir

or or,

alrearlr

etc., (',,

Whr',

- \4'r,

reques I

both

chargt,

the cas.

Ala. \;

(litql

422 (l{),

602 ilfl

36 So.

603, 36

App. ;,

251 Ah

21ll So 2rl :ti,:l (11)1 lt; ll,rlr','r, \. Sl;rlr,, il .\l:r.

,\1rgr lili l, 21lli So 2rl 'iitl ( lll? 1); I'r'irrr',, r'. ('ilI ol'

Ilirrrringlr;rrrr, Iiil Al:r .,\pp. :1).1. 2lllr S{r. 2{l il:11}

(l:l?l): Sl,rrr r'. Sl;rrr, lllil,\l;r. 201. :llrl S,,. 2rl 7S

(lll?l), ln(lcl)r'rrrl,'rrt l,il'r'& ,\r't'irlt t,t Itr:,. ('o. r'.

II:rrrr,,ll, iril ,\l;r. r\1r1r :l!li, :l()l S,r 2rl :ia ( 11171);

llrtrr,rrv v Slrlr'. iil ,\l:r. r\1rJr. l?ll,:l(ll So.'}l 2,1i1

( I il'; I ): (',rnnon \'. St:tt,,, ill ,\ l:r. ,\1,1,. ;{ll), :il) I S().

'2rl .ll ) l l lt?,l l: I". \\'. \\', rr,l ii r rt't lr v. l( iri,r'. :11,: i,\ l:t.

,.1,a. :l(t.l )('. Zri {;? ( l:r; ll, llt.r,{,tr r'. Sl:rtr,. ii.l :\ltr.

,\ 1,1r .,rs. illrl S,,. ]l ;{;:l ( I l} ; I r: \\'ilir,rrrr,, r . Sr:rtr',

;-rl ,\l:r ,\p1r. Zll, :llr; So. lrl rii (lll?i,): l)r':rrr r'.

Sl;r1,,, i L\l:1. ,\111, 2?lr, :il)7 So l2rl ?? (l1)ii);

i\lit,'lrr,ll \'. St:r1{,. i L\lrr. ,\1rp. ;t'1.1. :107 S,,. lrl 72{)

(ll)?5); Lrrvrrc r'. St:Llr,, il ,\lir. .\1r1, i21), illl) So.

2rl 211) ( Ill?.ir); Wcsl l Strrtt,, r-r L\lrr. ,\yrp. (i.17,

:ll2 So. 2,1 ti (ll)7i); Wrrlklr v. St:rtt,. i{i Alrr.

i\1rI l[1.;.|20 So 2rl ?l;:l (lll7:,): l,,lstUrr r. Slirtt,,

i{i ,\l:r i\1r1r. 2l}ll, :l:)l So. 2rl 2til (ll}7;).

('1ll;rlt,rltl rt'l'r.r.r,1ct'.. Sr,r, rtli'rt,rrcls

tttrllt \ l2 l{i I l.

l,lilrrr',' l,r r'ornyrlr, rvitlr st:rtut(,, ( ('r)slitlttionr\l

lrrovisir,n, r)r ('ollrI I'rtl, 1,t',,rirlitr{ lirr givirrg

instlrrr'tions to .ittt'r itr $ r'itilrg. I l; \l,li l:J:12.

ll. (lll,\ltcI,lS 'l'o llll lN

wtit't'tN(;.

('hirrges nrrtlerl for b-r'r:ither p:trl.r'nrrrst he

irr rvrilirrg. IlrrrL,t' tlte t,xIn'ss Irt'r)r'isiott of

tlris :r,r'tiott, lrll,'lrrrt(,'s nrr)\'r'{l for lr! r'illrt'r'

Ir:lll', ;u',' tt'r;trir,',1 to lr,' itr rvrrtirrg. \rrt'llrcrrl r'.

S t : rt,,, I :t,\ [ilmTTlxr ;'J r : Tf;.i;' rTA t : r r t,. I l, .\ I :r.

,,\1r1r. li:1. 1lS So. lil? (11,2:l); Ililrrrrr v. St:rte, 2l)

r\ l;r .\1r1r. :lX(i, lllll So X(i0 ( ll) l{)); l'lrrrlrgt,rrcr' .,\irl

l,il,, .\.r:'rt r'. (ilrtrrl,lr,, ill r\lir.,\1i1r. :17?, 40 So.

2rl rS? (llr llt); [irritIlrrlrr r.. St:r1,,, :ti r\llt. ,\plt.

,rjl. ll) So.'j(l ?Sll (lltr(l): (ir';rlr:trn v. St:rt(,.4()

i\ I:r \ 1,Ir. l? l, I l; So. lrl 2)ll) ( 1 lrrll) l h'r'l rrtrrrl v.

Sl ;rl,', l(i,\ l;r. r\ 1r1,. {;:l I. 2 l? S(). 2(l :i!r, I I 117 I ).'l'll(i

(:{rrrrt ma}' Il(,t giVt' ir clta|g| unlr'ss so

r'(,(l lri,st (.(1. ('oInrtr k0r' \'. St:ttr,, I l) r\ l:i. r\ I rlr. 5(t(1,

ll8 S,r iili:i ( ll)2:l). ,\rrrl, :r lirltiori, flrilrrtl ot't'ottrt

to 11ir,, it ll,;rrg,, rr,,l rtrltttstlrl is nrrt ln'ot.

Ilttt,llrr v Stirtr., :jl) ,\llr. ,\1,1r. 'i17. i{)2 So. .1(i1

(llr2l)

'l'llis slltiotr x'(ltlil r :r t lt:tt t'lr;trgt's l,r, t{'tl(l(,rPtl

Il),'{'(,ull irr u'riling ('oslrl t'. Strtte.,l2 r\la. App.

lr;0. l:,ri s,' j'l i:t;i rl:,r;:lt

'l'lris s,.r'ti,rn prls, ril,,,s tlrrt t'lt;rr1Jr,s trrttsl lrt'

tll,)\'r'(l l{rr irr rvrilirrll. \\'ilrlt,r v. Sllrtr', irl Allt.

r\1r1, li7, llllll So. ll,l:l:1.; (lll?,1).

.,\rrrl tet'olrl rrrrrsl shorv rvritttrr le(lut,st. -'l lrI r','l'rts:tl ol :r i'lr:rt'J{t'r'(,(lu{'l.l('{i is l|,rt :ttr t'r11rr

li,r' u lrr, lt tlrr' .jtrrllJrrr,,rrl rvill lrt' t'r,r't'rst,rl rvltt,tt

tlrr, r't.r'orrl rlor,s rrot rrlrrrv tlrrt it rvlts I'r,,ltt,','rl ttl

tvriltrtll rLs rt'rluit,,,l I't tlris slcliott. (lroslr\ !'.

llut('lrilrs()tr, i:i .\l;1. i I lS?ir); ,l11t'r,1,.,,)rr \'. St,rl('.

ir5 ALr. lirl (157(i); \\'lrt,less r'. Illrork's, 70 r\l:r.

,lll) (1881); Iiickt,tts r'. Ilirrnirrglranr St. Itv., 1.,5

Al:r. {i(ttt, 5 Srr. ili:i (lxtr1}); l}elli}rgt'r r'. Statr,,1)2

Alu. r,{i. l} So.:ll)1) (1x11{)); \!nl11nr v. St:tte. 1)1 Alir.

i(i. 1l So.87 (l81ll); I.irxrvortlr v. Ilrown, 114 Ala.

iZ1tll.2l So.4l:i 113t17; llr,rrtlerson v. State, 137

\ l:r. Hll, ll.l So. l{2}t ( llX)ll); .Johrrson v. State, ll Ala.

,\1r1r. l5l-r, i7 So. ,{{l1l {1912}; -F\rote v. SUIte, 16

,\lir A1r1r. l:J(i, ?5 So. 728 (llrl?l;Mitchell v. Surte,

lll Ala. Ap1r. 24x, ll(i So.6J-r3 (1923).'l'his is upon

I hr, firrniliar lrrinciple tlrat all reasonable

irrtt'nrlrlr,nls rrrust be indulgerl to support the

.irr,lgr,,",,l" of a ('orrrt of gerreral .jurisdiction and

tll:lt llnless err()r'is irffirnr:rtivt'lv slrorvn hv the

l1'('ot1l no r'('r'('r's:rl t'rtrt lr0 lurrl. l-l('tr(k'l'son v.

St:rtr,, lii7 .\lir. s:1. :l.t So. l{2lr (llX)i'}).

\\'lrr,re rro rerluestt:rl writtor) clrargr's appeared

irr Llre rccorrl,:rnrl no r,,xceptiot) \.\'as reserved to

tlre court's or;tl clutrgc iul(l tl)e onlt, point raised

irr alrpellurrt's lrrit,f pertainrrrl to such charges, an

lffirrnarrce of the case was rlict.tterl. Oarithers

v. (lorrrrrrercirtl ('rerlit Corp., ll:l Ala. r\pp. 472, 34

Srr. 2rl i05 (l1l.1l{).

llrrt rvlrr,rr, tlrc ck'rk t'r'rlifir.s tlr:rt tlrt'cll:trges

:r lt, orr l'iIr irr lris ol'l'it't. ltrrtl rtrt, nrirrli(,(l "rofttscd"

irr tlre lrrrnrlu'riting of lhe presirlirrg judge, this

rrr;rkes therrr a l)iirt of the record irnd enables the

sul)renre ('olrrl to rt,vise tlreir refusal, althCrugh

tlrt, recortl ()n appeirl (lrill of exceptions

lrrt,r,iorrsly) rloes not st:lte thxt ttrey were asked

in w'r'iting. lVirrslorv v. Stlrte, ?(i Ala. 42 (1884).

Otherwise :rppellate court u'ill not review

rt,l'usal of trial court, - [inless iL af firrlatively

;rlrl)t'irrs that the clrarge irsk|rl was in writing,

tirt irlrlrt:lllt+-, t'ourt will l)ot rcview the action of

tlrt' lorvr,r corrrt in r('fusing it. Hublrtrd v. State,

Zitil i\lu. 183, 215 So. 2tl 2(il (19(ili).

,\ triirl court cunnot be revers(-.d for relusril kr

givt, a charge askerl urrless it appears that the

r:h:rrge w:rs uskerl in rvriting as this section

rt:rlrrirt,s. Ilenlley \'. Larvson, 280 Ala. 220, L91

So. 2rl :,l72 (l1l(i(i); Hubbard v. State, 283 Ala. 183,

21i Srr. 2rl 2{;l (11,(;U).

'l'lre sll[)renre court will not reverse a

;rrtlgrrrerrt t,f the circuit court for its refusal to

l.tivc iI ch:rrge aske<l unless it ztplretrs that such

rhulgt w:rs I)ut in writil)g iis this section

lrlovirles. []ush v. Stunton, 27:l Ala. (i1ir, 14:J So.

2il (;21 ( llXi2).

,\s:u'r'rrserl rlirl not re(lu(,st a sl)ecial written

instnrctiorr as to irrtoxicltiorr accr-rrrling to the

I)r':r('ti('p estitlrlislrlrl lri' tlris st'ctiorr, tlrc circuit

corrrt's frtilure t,, irrclurle in tlre ontl charge an

irrstnrction :rs to intoxic:rtion of al)tx,llitnt as

ll'li,cting lris inlt,nt is not suhjt,ct to revierv by

I lrt crrrtrt of ;ryr1 rr':rls. ( i rosstricklr, v. SLrrte, 44 Ala.

.\1,1'. :tx1, Zlrll So. 2rl lil,{i (11,{ih).

l'or charge prescntr'd ()rilll.\' nonreviewrrble, I'I'his st,ction I,r'eclrrrlcs tlre coult of alryreals I

frrrrrr rt,r'it,lirrg ir rnotion f,,r a chltrge rvhich is I

l,l'r.s(,r)t('(l onlv or:rlll to tlrt, jurlge. Harris v. I

Sl:rlt,, l.J ,\l:r. .\1,p. 1,19.212 Sr,. :.|d til)i (11)68).J

As is case wlrere no request made. - If there

cirn be no reversal for fzrilure to give a charge

*'lrcrt,tlre request is nrade orally, then it does not

aplrear that a reversal should be allowed where

230