Patton v. Mississippi Brief for Petitioner

Public Court Documents

October 6, 1947

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Patton v. Mississippi Brief for Petitioner, 1947. 73cb4fe9-c09a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/7aabff4f-bcfd-4213-b99c-df8b42717541/patton-v-mississippi-brief-for-petitioner. Accessed March 13, 2026.

Copied!

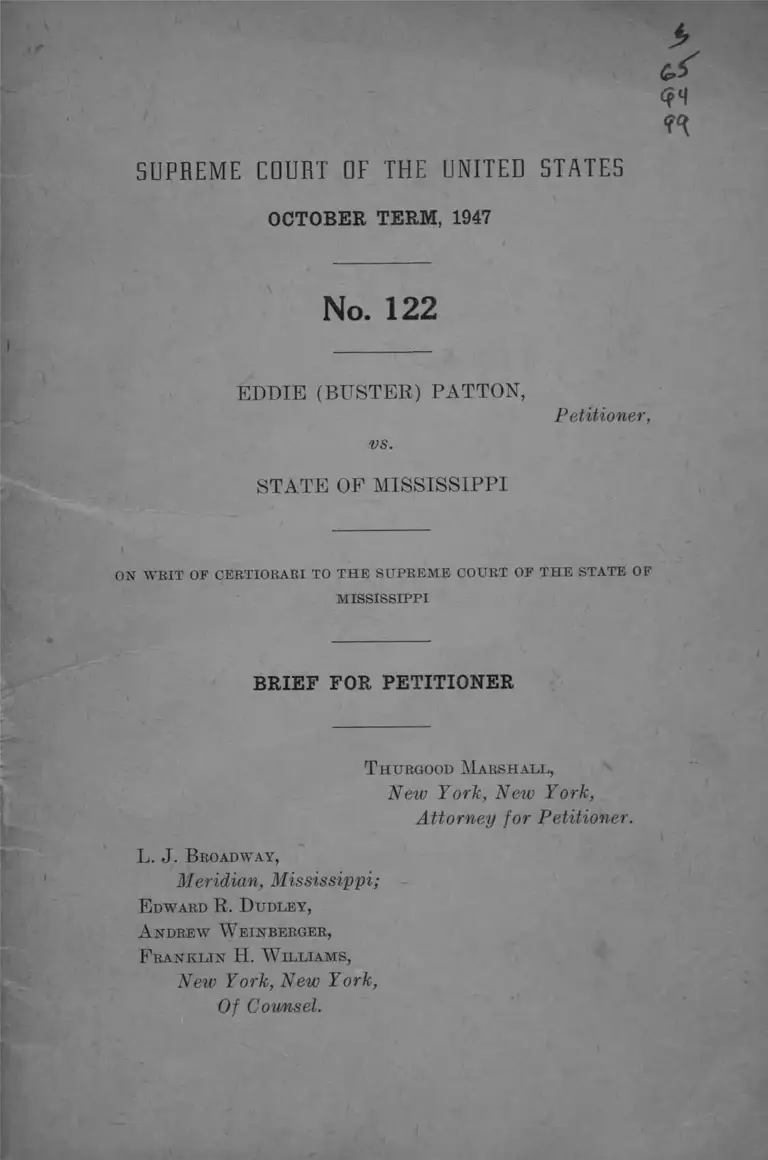

S U P R E M E CO URT OF TH E U N I T E D S T A T E S

OCTOBER TERM, 1947

n

No. 122

EDDIE (BUSTER) PATTON,

vs.

STATE OF MISSISSIPPI

Petitioner,

ON W RIT OF CERTIORARI TO TH E SUPREM E COURT OF T H E STATE OF

M ISSISSIPPI

BRIEF FOR PETITIONER

T h u r g o o d M a r s h a l l ,

New York, New York,

Attorney for Petitioner.

L. J. B r o a d w a y ,

Meridian, Mississippi;

E d w a r d R. D u d l e y ,

A n d r e w W e i n b e r g e r ,

F r a n k l i n H . W i l l i a m s ,

New York, New York,

Of Cownsel.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Opinion of Court below................................................. 1

Jurisdiction .................................................................. 1

Statement of case ........................................................ 2

Errors relied upon......................................................... 3

Argument:

I. The Supreme Court of Mississippi erred in

denying petitioner the equal protection of

the laws and due process of law guaran

teed by the Fourteenth Amendment by

affirming the conviction of a Negro by a

jury of white persons upon an indictment

found and returned by a grand jury of

white persons, from both of which said

juries all qualified Negroes have for a

long period of Years been systematically

excluded solely on account of race or color

pursuant to established practices............. 4

A. Petitioner was indicted and con

victed by Grand and Petit Juries in

the Circuit Court of Lauderdale

County in which Court at the time

of this trial and for a long period

of years prior thereto Negroes have

been systematically excluded from

jury service solely because of race

or color within the meaning of the

decisions of this Court.................... 5

(1) The record in this case clearly

establishes the systematic

exclusion of qualified Ne

groes from jury service in

Lauderdale County, Mis

sissippi, solely because of

race and co lo r ...................

(2) In affirming the conviction of

petitioner herein the Su

preme Court of Missis-

—2960

11 INDEX

Page

sippi erred in refusing to

consider evidence of sys

tematic exclusion of Ne

groes from jury service in

that county prior to the

year of the instant case. . .

II. The conviction of petitioner upon confessions

and statements extorted by force, duress

and intimidation obtained by officers and

agents of the State of Mississippi while

acting in their official capacity is a denial

of the equal protection and due process of

the law guaranteed by the Fourteenth

amendment to the Constitution of the

United States............................................. 18

Conclusion .................................................................... 20

T a b l e o f C a s e s

Brown v. Mississippi, 297 U. S. 278............................ 19

Brain v. U. .S'., 168 U. S. 532......................................... -19

Bush v. Kentucky, 107 U. S. 110.................................. 4

Carter v. Texas, 177 U. S. 442...................................... 5

Chambers v. State of Florida, 309 U. S. 227............... 19

(Creswill v. Knights of Pythias, 225 U. S. 246.............

■■Ex parte Virginia, 100 U. S. 313..................................

i Fisk v. Kansas, 274 IT. S. 380 .......................................

Hale v. Kentucky, 303 U. S. 613 ..................................

Hollins v. Oklahoma, 295 U. S. 394..............................

Lisenba v. California, 314 U. S. 219............................ 19

Martin v. Texas, 200 U. S. 316......................................

Neal v. Delaware., 103 U. S. 370 .................................... 14

Norris v. Alabama, 294 U. S. 587........................ . 5

Patterson v. Alabama, 294 U. S. 600.......................... 5

Pierre v. Louisiana, 306 U. S. 354................................

Rogers v. Alabama, 192 U. S. 226 ................................ 5

Smith v. Texas, 311 U. S. 128....................................... 6

Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U. S. 303..................... 4

Thiel v. Southern P. Co., 328 IT. S. 217........................ 18

Ward v. Texas, 316 U. S. 547....................................... 19

INDEX 111

O t h e r M a t e r i a l C i t e d Page

Mississippi Code, 1942, Sections 1762, 1766, 1768,

1772 ........................................... 5,11,15

Minutes of Special Committee to Investigate Sena

torial Campaign Expenditures, 1946, Senate of the

United States, 79th Congress; In the Matter of the

Investigation of the Mississippi Democratic Pri

mary Campaign of Senator Theodore Gr. Bilbo, Sen

ator, State of Mississippi, pp. 22, 98, 137, 146-147,

267,134,139, 320, 619, 608, 365, 395, 731, 754, 813. . 15

General Laws of Mississippi, 1946, Chapter 441...... 15

S U P R E M E E D U R T OF T H E U N I T E D S T A T E S

OCTOBER TERM, 1947

No. 122

EDDIE (BUSTER) PATTON,

vs.

Petitioner,

STATE OF MISSISSIPPI

ON W RIT OF CERTIORARI TO TH E SUPREM E COURT OF TH E STATE OF

M ISSISSIPPI

BRIEF FOR PETITIONER

Opinion of Court Below

The opinion has not been reported officially. It is

reported in 29 So. (2d) 96 and appears at pages 227-235 of

the record. Suggestion of Error (Petition for Rehearing)

was overruled by the Supreme Court of Mississippi on the

17th day of March, 1947 (R. 153), without opinion.

Jurisdiction

The date of the judgment in the Circuit Court of Lauder

dale County, Mississippi, is March 2, 1946. This judgment

was affirmed by the Supreme Court of Mississippi on Feb-

1 d

2

ruary 10, 1947. Suggestion of Error was overruled on

March 17, 1947.

Certiorari to review the judgment of the Supreme Court

of the State of Mississippi affirming the conviction was

granted by this Court on June 23,1947 (R. 153) upon a peti

tion therefor filed on June 12, 1947, and based upon Sec

tion 237(b) of the Judicial Code (28 U. S. C. 344(b)).

Statement of Case

Petitioner, a young ignorant Negro, was indicted on the

18th day of February, 1946, by the grand jury of Lauderdale

County, Mississippi, for the alleged murder of one Jim

Meadows, a white man fifty-three years of age. His trial

in the Circuit Court of Lauderdale County was begun on

February 28, 1946, and concluded the same day. He was

sentenced on March 2,1946, to suffer death by electrocution.

Prior to the trial on the merits, petitioner moved to

quash the indictment upon the grounds that Negroes in

Lauderdale County were systematically excluded from

service, on the jury solely because of their race or color

(R. 1). That motion was denied (R. 2). During the trial,

objection was made by petitioner to the introduction into

evidence of statements and confessions obtained from

petitioner by officers through the use of force, threats and

intimidation (R. 142). The court overruled the objections

(R. 142). An appeal was taken to the Supreme Court

of Mississippi. After affirmation by the court (R. 152),

Suggestion of Error was filed (R. 144) and overruled

(R, 153).

The material facts concerning the exclusion of Negroes

from jury service and the method of obtaining the con

fession are discussed in the argument herein.

3

Errors Relied Upon

I

The Supreme Court of Mississippi erred in denying peti

tioner the equal protection of the laws and due process of

law guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment by affirming

the conviction of a Negro by a jury of white persons upon

an indictment found and returned by a grand jury of white

persons, from both of which said juries all qualified Negroes

have for a long period of years been systematically excluded

solely on account of race or color pursuant to established

practices.

A. PETITIONEE W AS INDICTED AND CONVICTED BY GRAND AND

PE TIT JURIES IN TH E CIRCUIT COURT OP LAUDERDALE COUNTY IN

W H IC H COURT AT TH E TIM E OF TH IS TRIAL AND FOR A LONG PERIOD

OF YEARS PRIOR THERETO NEGROES HAVE BEEN SYSTEM ATICALLY

EXCLUDED FROM JU R Y SERVICE SOLELY BECAUSE OF RACE OR COLOR

W IT H IN TH E M EANING OF T H E DECISIONS OF TH IS COURT.

(1) The Record in this Case Clearly Establishes the Sys

tematic Exclusion of Qualified Negroes from Jury Service

in Lauderdale County, Mississippi, Solely Because of Race

and Color.

(2) In Affirming the Conviction of Petitioner Herein

The Supreme Court of Mississippi Erred in Refusing to

Consider Evidence of Systematic Exclusion of Negroes

from Jury Service in that County Prior to the Year of the

Instant Case.

2d

4

II

The conviction of petitioner upon confessions and state

ments extorted by force, duress and intimidation obtained

by officers and agents of the State of Mississippi while act

ing in their official capacity is a denial of the equal protec

tion and due process of the law guaranteed by the Four

teenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United States.

ARGUMENT

I

The Supreme Court of Mississippi erred in denying peti

tioner the equal protection of the laws and due process of

law guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment by affirming

the conviction of a Negro by a jury of white persons upon

an indictment found and returned by a grand jury of white

persons, from both of which said juries all qualified Negroes

have for a long period of years been systematically excluded

solely on account of race or color pursuant to established

practices.

It is well settled that whenever by an action of a State

all persons of a particular race are excluded solely because

of their race or color from service as jurors in a criminal

prosecution of a person of that race the equal protection of

the laws is denied to him, and he is deprived of due process

of law contrary to the Fourteenth Amendment of the United

States Constitution. This principle applies whether the

action is by virtue of a statute 1 or by the action of adminis

1 Bush v. Kentucky, 107 U. S. 110, 122; Strauder v. West Virginia, 100

U. S. 303, 309.

5

trative officers 2 and whether the exclusion is from service

on petit juries 3 or grand juries.4 5

The Mississippi Supreme Court, while admitting that this

principle is well settled,® refused to apply it to the facts of

this case, and by reason of such failure denied petitioner his

constitutional rights.

A . PETITIONER. WAS INDICTED AND CONVICTED BY GRAND AND

PETIT JU R IE S IN T H E CIRCUIT COURT OF LAUDERDALE COUNTY,

M ISSISSIPPI, IN W H IC H COURT AT TH E TIM E OF TH IS TRIAL AND

FOR A LONG PERIOD OF YEARS PRIOR THERETO NEGROES HAVE

BEEN SYSTEM ATICALLY EXCLUDED FROM JU R Y SERVICE SOLELY

BECAUSE OF RACE OR COLOR W IT H IN TH E M EANING OF THE

DECISIONS OF T H IS COURT.

While the Mississippi statutes relative to juries and

jurors 6 do not in terms provide for the exclusion of Negroes,

the evidence discloses an exclusion and resultant discrimina

tion by administrative officers as uniform and effective as

if required by statute.

(1) The Record in This Case Clearly Establishes the

Systematic Exclusion of Qualified Negroes from Jury

Service in Lauderdale County Solely Because of Race and

Color.

2 Rogers v. Alabama, 192 U. S. 226, 229; Carter v. Texas, 177 U. S.

442.

3 Norris v. Alabama, 294 U. S. 587; Strauder v. West Virginia, supra.

4 Carter v. Texas, supra, at page 444; Patterson v. Alabama, 294 U. S.

600.

5 “ It has long been settled in this country that an intentional and arbi

trarily systematic exclusion of Negroes from grand and petit jury lists

solely because of their race and color denies the equal protection of the

laws to a Negro charged with crime, so that at this time no parade o f the

authorities is necessary on that point” (R. 146).

6 Mississippi Code (1942), sections 1762-1772.

6

The Mississippi Supreme Court in affirming the judg

ment of the trial court held that the evidence was sufficient

to sustain the action of the trial judge in overruling peti

tioner’s motion to quash the indictment and his objection to

the special venire on the grounds that Negroes were

excluded from such juries. In a recent case involving this

identical question this Court in a unanimous opinion by Mr.

Justice Black recognized the responsibility of this Court

to make an independent appraisal of the evidence as it

relates to the petitioner’s constitutional rights.7

In an opinion by Mr. Chief Justice Hughes, after stating

the general principle set out above, it was pointed out

that:

“ The question is of the application of this established

principle to the facts disclosed by the record. That

the question is one of fact does not relieve us of the

duty to determine whether in truth a federal right has

been denied. When a federal right has been specially

set up and claimed in a state court, it is our province to

inquire not merely whether it was denied in express

terms but also whether it was denied in substance and

effect. If this requires an examination of evidence,

that examination must be made. Otherwise, review by

this Court would fail of its purpose in safeguarding

constitutional rights.8

Such an independent appraisal of the evidence herein

will reveal that qualified Negroes were systematically

excluded from jury service in Lauderdale County, Mis

sissippi, because of race or color within the meaning of

prior decisions of this Court. The testimony of fourteen

witnesses, not sympathetic to either petitioner or members

of his race, reveals that Negroes were systematically

7 Smith v. Texas, 311 U. S. 128 at p. 130.

8 Norris v. Alabama, supra, at p. 589.

7

excluded from, jury service in that county solely because

of race or color.

B. M. Stephens, a former member of the Board of Super

visors of the county from 1924 through 1931, and Sheriff

of the county from 1931 through 1935, testified that as

supervisor it was his duty to help fill the jury boxes and i

during these years he had never known a Negro to “ be on

the jury, coming out of the jury box or going into it” and 1 ^

that during that time it was a matter of common knowledge \

that there were some Negroes qualified_£or jury service in

the gountv (B. 3-6).

Mrs. Addie Bivers, a deputy circuit clerk for four (4)

years and a clerical worker in the office of the Circuit Clerk

for two (2) years prior thereto, testified that to her knowl

edge no Negro had served, been called on to serve or drawn

on a jury, grand or petit, during that time; that in 1945, the

Clerk did list eight (8) Negro qualified jurors for service

in the local Federal District Court (B. 8). She further

testified that no Negro was called or served on the grand

jury for the term at which petitioner was indicted (B. 6-12).

C. C. Ferrill, Circuit Clerk, with over thirteen (13) years .

service in the Chancery Clerk’s office, testified that he never

knew of a Negro serving on the jury at any term of the

Circuit Court or being drawn or summoned for such service.

He further testified that it was his judgment that there were *

about twenty-five (25) qualified Negro jurors in Beat One,

city of Meridian, which city is in Lauderdale County (B.

12-23).

Howard Cameron, Chancery Clerk since January, 1936,

and deputy for such office since March, 1933, testified that

in his judgment, there were eight thousand to ten thousand

qualified electors in the county and that there were several

hundred Negro registrants on the books of Lauderdale

County (B. 25). He further testified that to his knowledge

since 1933 there had never been any Negro empanelled for

8

nor any to serve on the grand or petit jury in the criminal

courts of the county, and that there were no Negroes on the

grand jury that indicted petitioner (R. 23-31).

W. Y. Brame, Sheriff since 1944 and tax assessor for the

county for twelve years prior thereto, testified that there

were no Negroes on the jury summoned for the February,

1946 term of court; that he knew of only one Negro having

been summoned for jury duty during his connection with

the county government, which individual did not report,

and that he had found from time to time some forty (40) to

fifty (50) Negro registrants on the books (R. 31-38).

Tom Johnson, member of the Board of Supervisors,

testified that during his twenty-five (25) to thirty (30) years’

service in such county, he had never listed any Negro jurors

and had never tried to determine whether there were any

qualified for such in his jurisdiction (R. 42-48). He testi

fied: “ Q. Mr. Johnson, in making up your jury list since

you have been supervisor have you made any effort at any

time to determine whether in the registration books for

your beat there were registered Negroes with a view of

listing them for jury service! A. I have never had that

in mind, because we did not have any darkies of conse

quence in the beat, have not yet. I have enough troubles

without going into all those details.”

J. A. Riddell, Judge, Lauderdale County Court, and a

practicing attorney in the county since 1916, and a resident

in the county since 1911, testified that since 1916 no Negro

had served upon the grand jury in the county and that no

Negro had been called or qualified for such service during

those years; that in his judgment there were about one

hundred (100) Negro qualified electors (R. 48-54).

George Beeman, Superintendent of Education of the

county for ten (10) years, testified that during those years

no Negro had been impanelled or called to the jury box

for the grand jury (R. 54-57).

9

Donovan Ready, a CPA, testified that a check of the

number of qualified electors of the county in the years 1941

and 1942 showed that there were at least thirty (30) to sixty

(60) Negro qualified electors, and that there might have

been others whom he did not know (R. 57-60).

E. C. Gunn, a member of the Board of Supervisors for

about six (6) years, testified that though there were four

(4) or five (5) Negroes on the registration books of his Dis

trict, he had not listed a Negro for jury duty during his

term in office, and that to his knowledge not a single Negro

had been called to the jury box with the view of being

qualified for grand jury service, nor had any served on

the grand jury during his term of office (R. 60-63).

L. D. Walker, member of the Board of Supervisors for

seventeen (17) years, testified that to his knowledge no

Negro had served on the grand jury or had been called to

qualify for such during his period of service. He stated

further that he did not know of an instance in the history

of the county where a colored person had served upon the

grand jury (R. 63-69).

0. L. King, member of the Board of Supervisors for

seven years, stated that he did not know of having ever

seen a Negro impanelled or called to the jury box during

his period of service (R. 69-74).

William Wright, member of the Board of Supervisors for

about nine (9) or ten (10) months, testified that no Negroes

served on the February, 1946 grand jury, and that he

knew that for fifteen (15) years no Negroes had served on

the grand jury in that county, though there were some

qualified Negro electors on the books (R. 74-80).

Frank Kennedy, former member of the Board of Super

visors from 1928 to 1932, testified that during his term of

office he did not list the name of any Negro on the jury

list though there were one or two that he knew of who were

in every respect qualified, and that there might have been

10

more so qualified that lie did not know. He stated further

that to his knowledge no Negro had ever served on the

grand jury (E. 80-84).

There was testimony to show that the ratio of Negroes to

whites in the population of Lauderdale County was approxi

mately sixty-five (65) to thirty-five (35) (R. 85) or fifty-

fifty (R. 83).

In the face of this testimony, the Supreme Court of the

State of Mississippi, in its opinion, concluded that the

trial judge was justified “ in finding that there were not

over fifty qualified Negro electors in the county, of whom

. . . one-half were women, which would leave twenty-five

qualified Negro male electors. He was justified also in

accepting the testimony . . . that at least half the Negro

electors . . . were teachers or ministers or physicians,

or otherwise exempt from jury service. Of the twenty-five

qualified Negro male electors, there would be left . . .

twelve or thirteen available male Negro electors . . .

or about one-fourth of one per cent Negro jurors,—four

hundred to one’ ’ (R. 148).

Continuing to apply the rule of an alleged percentage

as to the special venire the Court held: “ For the reasons

already heretofore stated there was only a chance of 1 in

400 that a Negro would appear on such a venire and as this

venire was of one hundred jurors, the sheriff, had he

brought in a Negro, would have had to discriminate against

white jurors, not against Negroes,—he could not be ex

pected to bring in one-fourth of one Negro” (R. 149).

The opinion of the Supreme Court of Mississippi ignores

most of the material testimony on the jury question and

based its decision upon testimony of three of the fourteen

witnesses called to the effect that there were an estimated

eleven thousand qualified electors in the county and that

there were less than one hundred, or as one witness testified

11

fifty qualified Negro electors in the county9 half of whom

were estimated to be ineligible because of sex or occupation

(R. 147-149).

In examining Mrs. Addie Rivers, a Deputy Clerk, as to

the contents of two poll tax books representing two divisions

of one precinct there were found the names of at least eleven

Negroes, which names indicated that they were men in every

respect qualified to be listed on the jury rolls (R. 38-41).

Howard Cameron, Chancery Clerk testified that:

“ Q. Mr. Cameron, could you and would you give

the court the benefit of your very best judgment as to

the number of names of members of the Negro race that

now appear upon the registration books of Lauderdale

County ?

9 Code 1942, Section 1762, 1766, 1768, 1772.

Section 1762 provides who are competent jurors in the following lan

guage: “ Every male citizen not under the age of twenty-one years, who

is a qualified elector and able to read and write, has not been convicted of

an infamous crime, or the unlawful sale o f intoxicating liquors within a

period of five years and who is not a common gambler or habitual drunkard,

is a competent juror (both grand and petit); but no person who is or has

been within twelve months the overseer o f a public road or road contractor

shall be competent to serve as a grand juror. . . .”

Section 1766, Code of Mississippi, 1942:

“ The board of supervisors at the April meeting in each year or at a

subsequent meeting is not done at the April meeting, shall select and make

a list o f persons to service as jurors in the circuit.court for the twelve

months beginning more than thirty days afterwards, and as a guide in

making the list they shall use the registration book of voters, and shall

select and list the names of qualified persons of good intelligence, sound

judgment, and fair character, and shall take them as nearly as they con

veniently can, from the several supervisor’s districts in proportion to the

number of qualified persons in each. . . . The clerk of the circuit court

shall put the names from each supervisor’s district in a separate box or

compartment, kept for the purpose, -which shall be locked and kept closed

and sealed, except when juries are drawn, when the names shall be drawn

from each box in regular order until a sufficient number is drawn. The

board of supervisors shall cause the jury box to be emptied of all names

therein, and the same to be refilled from the jury list as made by them at

said meeting. I f the jury box shall at any time be so exhausted of names

as that a jury cannnot be drawn as provided by law, then the board of

12

“ A. Frankly I have never given it any considera

tion, but I am under the opinion that there are several

htmdred of them” (R. 25).

A County Court Judge, J. A. Riddell, testified that in

his judgment there were about one hundred Negro qualified

• electors in the county (R. 75-82) while, Donovan Ready,

another witness, found as a result of a personal check of the

' rolls in 1941 and 1942 from thirty to sixty Negro qualified

electors whom he personally kneiv.

An independent examination of the evidence in this case

will reveal:

(1) That for at least thirty years prior to the trial of

petitioner, no Negro had been drawn, summoned or served

on a Grand or Petit Jury in Lauderdale County.

(2) That at various times during these years there had

been from twenty-five to several hundred qualified Negro

electors who could have been properly listed, drawn or

summoned for such service, and that the existence of such

qualified Negro electors was common knowledge through

out the county.

(3) That the Clerk of the Circuit Court, at the request

of the Federal Jury Commissioner, had, with little effort,

supervisors may at any regular meeting make a new list of jurors in the

manner herein provided. In order that the board of supervisors may

properly perform the duties required of it hy this section, it is hereby

made the duty of the circuit clerk of the county and the registrar of the

voters (also the clerk) to certify to the board of supervisors during the

month o f March of each year under the seal of his office the number of

qualified electors in each o f the several supervisor’s districts in the

county.”

Section 1768, Mississippi Code 1942, provides that the list o f names thus

selected and made up be certified to the clerk o f the circuit court, and

carefully filed and preserved by him as a record of his office.

Section 1772 of the same code provides how grand and petit juries are

drawn for terms of court.

13

furnished him with a list of at least eight such Negroes who

were in every respect so qualified.

(4) That no Negroes served on the Grand Jury which

found the indictment in the instant case, and that no

Negroes served on the Petit Jury which convicted the

petitioner.

The testimony establishing these facts was sufficient in

itself to make out a prima facie case of the denial of the

equal protection of the laws to petitioner. In Norris v.

Alabama, supra, where similar evidence was introduced,

the Court said:

“ We are of the opinion that the evidence required

a different result from that reached in the state court.

We think that the evidence that for a generation or

longer no Negro had been called for service on any

jury in Jackson County, that there were Negroes quali

fied for jury service, that according to the practice of

the jury commission their names would normally

appear on the preliminary list of male citizens of the

requisite age but that no names of Negroes were placed

on the jury roll, and the testimony with respect to the

lack of appropriate consideration of the qualifications

of Negroes, established the discrimination which the

Constitution forbids.” 10

Once this prima facie case had been established by peti

tioner, it then became incumbent upon the State to prove

by competent testimony that Negroes were not unconstitu

tionally excluded from jury service. This burden the State

failed to sustain.11

10 294 U. S. 587, 596.

11 “ We think that this evidence failed to rebut the strong prima facie

case which defendant had made. That showing as to the long-continued

exclusion of Negroes from jury service, and as to the many Negroes quali

fied for that service, could not be met by mere generalities. If, in the

presence of such, testimony as defendant adduced, the mere general asser-

14

2) In Affirming the Conviction of Petitioner Herein The

Supreme Court of Mississippi Erred in Refusing to Con

sider Evidence of Systematic Exclusion of Negroes from

Jury Service in That County Prior to the Year of the

Instant Case.

The Supreme Court of Mississippi refused to consider

the evidence of the systematic exclusion of Negroes from

jury service over a long period of years prior to the year

immediately preceding the trial:

“ We have not gone back of the year of and immedi

ately preceding this trial, as to the jury lists, for the

evident reason that in that respect we are concerned

with that which bears real relation to the instant case

and therefore with the present and that which was in

the immediate parts,—not with what may have hap

pened in remote days. And in following out the mathe

matical calculations per capita among the nonexempt

qualified persons, we are not to be considered as having

resorted to it as an exclusion method for the solution

of the question with which we have above dealt. Upon

such a broad issue other considerations are to have

their proper bearing. We have proceeded as we have

here, because that method is sufficient for the present

case” (R. 149).

Prior decisions of this Court have clearly established

the principle that testimony of the exclusion of Negroes

from jury service in former years is competent evidence of

unconstitutional discrimination in the selection of jurors

and is entitled to great weight.12

tions by officials of their performance o f duty were to be accepted as an

adequate justification for the complete exclusion of Negroes from iurv

service, the constitutional provision— adopted with special reference to

their protection— would be but a vain and illusory requirement.”— Norris

v. Alabama, supra, at p. 598.

12 Norris v. Alabama, supra; Neal v. Delaware, 103 U. S. 370. See

also: 82 L. Ed. 1070, 1072.

15

Under the laws of the State of Mississippi, in addition

to requiring as a prerequisite for being eligible for jury

service, that one be “ a qualified elector,” 13 it is also re

quired that the registration book of voters shall be used

“ as a guide in making the list” of potential jurors. The

code further provides that the list of prospective jurors

shall be certified to the Clerk of the Circuit Court, filed and

preserved by him.14 15

Testimony presented before the Special Committee to

Investigate Senatorial Campaign Expenditures, 1946-79th

Congress at hearings held in Jackson, Mississippi on the

2d, 3d, 4th and 5th days of December, 1946, showed a

state-wide condition of intimidation by State officers of

large blocks of Negroes who attempted to register and to

vote in a recent primary held in that State.ir'

In 1946, Mississippi passed a law exempting veterans

from payment of poll taxes under certain conditions.16 A

great movement of Negro veterans took place all over the

State to register to vote. There were 66,972 discharged

Negro veterans in Mississippi and practically 100% of them

could read and write.17

The Supreme Court of Mississippi in a futile effort to

distinguish this case from Smith v. Texas, supra, pointed

out that in the Smith case ten percent of the qualified

jurors were Negroes and that in the instant case the ratio

was less than one percent. In doing this the Court not only

ignored the evidence of witnesses that there were “ hun-

13 Mississippi Code, 1942, Section 1762.

14 Mississsippi Code, 1942, Section 1768.

15 See Minutes of Special Committee to investigate Senatorial Campaign

Expenditures, 1946, Senate of the United States, 79th Congress; In the

Matter of the Investigation of the Mississippi Democratic Primary Cam

paign of Senator Theodore Or. Bilbo, Senator, State of Mississippi, pp.

22, 98, 137, 146-147, 267, 134, 139, 619, 608, 365, 395, 731, 754, 813.

16 General Laws of Mississippi— 1946, Chap. 441, App. April 10, 1946.

17 See Minutes, footnote 15, pages 491-493.

16

dreds” of Negroes qualified for jury service but also

ignored the reasons for there being only “ hundreds” of

Negro registered voters. The State of Mississippi acting

through its officers not only excluded Negroes from jury

service by refusing to call qualified Negroes, but also

effectively excluded Negroes by preventing them from quali

fying under the laws of Mississippi by means of force,

intimidation and duress in violation of the United States

Constitution.

Accordingly, many hundreds of Negroes whose names

should legitimately appear upon the registration rolls in

the custody of the Circuit Clerk of Lauderdale County,

which rolls by law were to be used as a guide in selecting

and making a list of potential jurors 18 were unlawfully

denied the opportunity to have their names entered thereon.

There can be no clearer indication of the atmosphere

in which the juries of Lauderdale County are selected and in

which petitioner was tried than the testimony of Tom John

son, a member of the Board of Supervisors off and on since

1904 and in continuous service since 1928, that:

“ Q. Mr. Johnson, in making up your jury list since

you have been supervisor have you made any effort at

any time to determine whether in the registration books

for your beat there were registered Negroes with a

view of listing them for jury service!

A. I have never had that in mind, because we did not

have any darkies of consequence in the beat, have not

yet. I have enough troubles without going into all

those details” (R. 46).

Mr. Johnson, on the other hand, testified:

“ Q. As a general thing, the vast majority of whites

meet those requirements of good intelligence, sound

judgment and fair character?

A. Not all.

18 Mississippi Code, 1942, Section 1766.

17

Q. I would hate to say all. The vast majority of

them do though, don’t they?

A. The vast majority do; yes, sir.

Q. Therefore you list whites insofar as that qualifica

tion is concerned generally, don’t pay so much attention

to it, is concerned generally, don’t pay so much atten

tion to it, as you do regard them of good intelligence,

sound judgment and fair character?

A. There are some exceptions. In other words, sup

pose a man is in trouble all the time, been convicted of

selling whiskey, any other violations of the law, I don’t

consider him worthy of a juryman.

Q. When you have that knowledge certainly you

don’t, and you are right, but where you don’t have

knowledge personally and should not have any, you go

on the assumption he will meet that qualification?

A. Yes, sir; as far as I know I try to put him in

there if (fol. 74) he is qualified in that request” (R. 48).

The extent of this discrimination becomes more apparent

when we compare the fact that there are 10,435 white per

sons over the age of twenty-one in Lauderdale County and

5,548 Negroes over the age of twenty-one in that county and

witness after witness testified that no Negro had ever

been called for jury service in that county.18a

This type of law enforcement is in direct opposition to

our Constitution as interpreted by this Court and is m

flagrant disregard of the principle as set forth in a recent

decision.

“ The American tradition of trial by jury, considered

in connection with either criminal or civil proceedings,

necessarily contemplates an impartial jury drawn from

a cross-section of the community. This does not mean,

of course, that every jury must contain representatives

of all the economic, social, religious, racial, political and

geographical groups of the community; frequently

180 16th United States Population Census— 1940.

18

such complete representation would be impossible.

But it does mean that prospective jurors shall be

selected by court officials without systematic and inten

tional exclusion of any of these groups. Recognition

must be given to the fact that those eligible for jury

service are to be found in every stratum of society.

Jury competence is an individual rather than a group

or class matter. That fact lies at the very heart of the

jury system. To disregard it is to open the door to class

distinctions and discriminations which are abhorrent to

the democratic ideals of trial by jury.” 19

II

The conviction of petitioner upon confessions and state

ments extorted by force, duress and intimidation obtained

by officers and agents of the State of Mississippi while acting

in their official capacity is a denial of the equal protection

and due process of the law guaranteed by the Fourteenth

Amendment to the Constitution of the United States.

From the testimony of a deputy sheriff in the instant

case, it was ascertained that petitioner, an ignorant Negro

youth, was taken to the local jail and placed in the office at

approximately 1 p. m. on the afternoon of his arrest (R.

He was kept in this secluded office and was denied

any opportunity to contact an attorney, relatives or friends.

He was forced to remain so confined in the presence of

numerous policemen and other law enforcement officials

whose powers in his mind undoubtedly were greatly magni

fied, until about 8 or 8 :30 that night. During all of this time

he was denied food and drink. He was being continually

subjected to grilling, questioning and cross-examination by

approximately seven or nine white officers. He was made

19 Thiel v. Southern P. Co., 328 U. S. 217, at p. 220.

19

f & t

to strip off his clothing and lie on the floor naked (R. •4#§).

There was some testimony which wo.uld lead to an inference

that he was actually beaten (R. m y . While on the floor,

he was continually told that he was lying; that he might

as well tell the truth and that they were_gping to get it out

of him anyhow (R. ^ i

As a result of this tortuous inquisition, petitioner

allegedly confessed to having stolen and concealed certain

articles belonging to the deceased, and made other state

ments tending to connect him with the crime. He was then

chained and manacled and carried to various remote places

where he allegedly pointed out the hiding place of these

articles and identified them.

After a brief* and cursory preliminary hearing as to the

voluntary nature of parts of these confessions, at which

time only^Se^?ftless testified, the court allowed numerous

references to be made to them ^ erH ie objection ofneti-

tioner (R. 4 $ ( f f , £ 2 , . # ^ 204; H 0f. '

These rulings were error and the admission of such

testimony was in violation of constitutional guarantees of

equal protection and due process of the law.20

The State Supreme-Court in its opinion attempted to

justify the admission of various portions of the appellant’s

alleged confession on the ground that they “ had definite

relations to the articles mentioned and to the pointing out of

the place where appellant admitted he had concealed them

. . . ’ ’ However, as stated by this Court:

“ The aim of the requirement of due process is not

to exclude presumptively false evidence, but to prevent

20 Brain v. U. S., 168 U. S. 532; Brown v. Mississippi, 297 U. S. 278;

Chambers v. Florida, 309 U. S. 227; Lisenba v. California, 314 tJ. S, 219;

Ward v. Texas, 316 U. S. 547.

20

* ' * *

fundamental unfairness in the use of evidence whether

true or false. The criteria for decision of that ques

tion may differ from’ those appertaining to the state’s

rule as to the admissibility of a confession. As applied

to a criminal trial, denial of due process is the failure

to observe that fundamental fairness essential to the

very concept of justice . . . Such unfairness exists

when a coerced confession is used as a means of obtain

ing a verdict of guilt. We have so held in every in

stance in which we have set aside for want of due

process a conviction based on a confession” (italics

ours).21

The conviction of petitioner herein should be reversed.

It was based solely upon a confession secured under cir

cumstances constituting duress and intimidation, a situation

which has been many times the basis for this Court’s re

versal of such unlawful convictions.22 •*».

- * ’Conclusion •

Petitioner was indicted and tried by juries from which

members of his race were systematically excluded simply

because they were Negroes. This not only violates our

Constitution and the laws enacted under it but is at war with

our basic concepts of a democratic society and a representa

tive government.

The record clearly shows further that petitioner’s con

viction was based upon portions of a confession extorted

from him through the use of force, duress, violence and

intimidation.

The court’s refusal to quash the indictment herein, and

its refusal to quash the special venire and the admission of

21 Lisenba v. California, supra, at 236.

22 See footnote 20, supra.

21

portions of an unlawfully obtained confession were viola

tive of the Constitution and laws of the United States.

W h e r e f o r e , it is respectfully submitted that the judg

ment of the Supreme Court of the State of Mississippi

should be reversed.

T h t j r g o o d M a r s h a l l ,

20 West 40 Street,

New York 18, Neiv York,

Attorney for Petitioner.

L. J. B r o a d w a y ,

P. 0. Box 969,

2nd Floor Rosenbaum Building,

Meridian, Mississippi;

A n d r e w W e i n b e r g e r ,

67 West 44 Street,

New York 18, New York;

E d w a r d R. D u d l e y , ,

F r a n k l i n H. W i l l i a m s ,

20 West 40th Street,

Netv York 18, New York,

Of Counsel.

(2960)

1 '

'

■ • v-

. v: