Response in Opposition to Appellees' Motion to Expedite Schedule for Appeal

Working File

March 22, 2000

4 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Cromartie Hardbacks. Response in Opposition to Appellees' Motion to Expedite Schedule for Appeal, 2000. 44aaf7cf-db0e-f011-9989-002248226c06. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/7aaef43b-1fce-4cc4-8edb-869c1ccc1c37/response-in-opposition-to-appellees-motion-to-expedite-schedule-for-appeal. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

NORMAN CHACHKIN - sup ct response ® to expedite.wpd a C EE

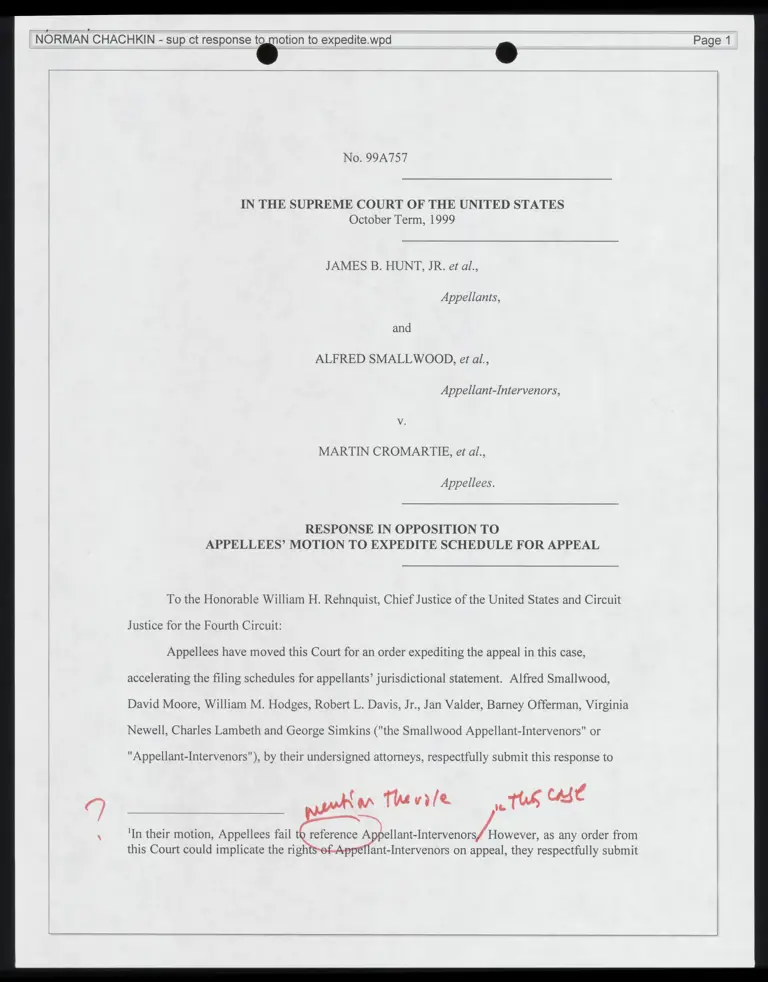

No. 99A757

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

October Term, 1999

JAMES B. HUNT, JR. et al.,

Appellants,

and

ALFRED SMALLWOOD, et al.,

Appellant-Intervenors,

V.

MARTIN CROMARTIE, et al.,

Appellees.

RESPONSE IN OPPOSITION TO

APPELLEES’ MOTION TO EXPEDITE SCHEDULE FOR APPEAL

To the Honorable William H. Rehnquist, Chief Justice of the United States and Circuit

Justice for the Fourth Circuit:

Appellees have moved this Court for an order expediting the appeal in this case,

accelerating the filing schedules for appellants’ jurisdictional statement. Alfred Smallwood,

David Moore, William M. Hodges, Robert L. Davis, Jr., Jan Valder, Barney Offerman, Virginia

Newell, Charles Lambeth and George Simkins ("the Smallwood Appellant-Intervenors" or

"Appellant-Intervenors"), by their undersigned attorneys, respectfully submit this response to

ail fenife | uk cdl

'In their motion, Appellees fail t yo etn tiie as any order from

this Court could implicate the righ ant-Intervenors on appeal, they respectfully submit

| NORMAN CHACHKIN - sup ct co De to expedite.wpd

Appellees’ Motion to Expedite Schedule for Appeal. For the following reasons, the Smallwood

Appellant-Intervenors respectfully request that the Circuit Justice or this Court deny Appellees’

motion. |

Appellees] offer one principle rationale in support of their motion. They argue that, since

"the parties to this litigation are well aware of the legal issues which may arise and are also

familiar with this Court’s precedents concerning such issues," Appellants can prepare their

jurisdictional statement on an expedited basis. Appellees’ Motion to Expedite Schedule for

Appeal ("Appellees’ Motion") at 2-3.

Appellees’ arguments do not support expediting the appeal in this case. Indeed, as

Appellees seem to be encouraging this Court to make its determination on the merits based in

part upon the appellants’ Jansdistionatyl a, see id. at a nd 4, this Court should permit

Appellants and Appellant-Intervenors boil fr le ttt

below’in their jurisdictional Semen 0 pew LE

Under this Court’s precedents, 2. ‘analytically distinct" claim recognized in Shaw v.

Reno, 509 U.S. 630 (1993) demands a particularly fact-intensive evaluation, requiring a

"searching inquiry . . . before strict scrutiny can be found applicable." Bush v. Vera, 517 U.S.

952, 958 (1996). See id at 959 (in "mixed motive" cases, "careful review" is necessary to

determine application of strict scrutiny to electoral districts). Accordingly, this Court remanded

this case for a full trial on the merits after holding "it was error in this case for the District Court

to resolve the disputed fact of motivation at the summary judgement stage." Hunt v. Cromartie,

119 S. Ct. 1545, 1552 (1999).

During the three-day trial in this case, an extensive factual record was developed by the

parties, containing detailed information about the legislative motivations in creating the Twelfth

this response to Appellees’ motion.

| NORMAN CHACHKIN - sup ct response ® to expedite.wpd » Page 3

/ recap itulnfed Mm Phe pop

/

Congressional District and the Loctinmes of the process that lead to the creation of the

challenged redistricting plan/ While FE ni that the issues on appeal have been

raised in Appellants’ stay dpplications, see Appellees’ Motion at 3, in & the extensive trial

record has not been peesented to this Court. Only a full appellate SS duleil permit Appellants

and Appellant-Intervenors sufficient time to cull the record and present a complete jurisdictional

statement that will aid this Court in making its determination in this matter.

On appeal, this Court will have to determine what role, if any, that race played in the

redistricting process. This Court should allow itself the benefit of reviewing a complete set of

jurisdictional statements and appendices, so that it may evaluate whether the district court in fact

engaged in the fact-intensive inquiry and exhaustive review of the legislative process required by

this Court’s precedents.

*The Smallwood Appellant-Intervenors are unaware of a situation in which this Court has

expedited the appeal of a case brought under the constitutional regime set forth in Shaw v. Reno

and its progeny, particularly following the grant of a stay pending appeal. Granting Appellee’s

motion may, therefore, be unprecedented in cases such Hunt v. Cromartie.

3

Page 4

CONCLUSION

For the reasons set forth herein, the Smallwood Appellant-Intervenors respectfully

request that the Circuit Justice or this Court deny Appellees’ Motion to Expedite Schedule for

Appeal. J

ADAM STEIN

Ferguson, Stein, Wallas, Adkins

Gresham & Sumter, P.A.

312 West Franklin Street

Chapel Hill, North Carolina 27516

(919) 933-5300

This 22nd day of March, 2000.

_ ew Ariel

Respectfully submitted,

ELAINE R. JONES

Director-Counsel and President

NORMAN J. CHACHKIN

JACQUELINE A. BERRIEN

NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street, Suite 1600

New York, New York 10013

(212) 219-1900

TODD A. COX

NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc.

1444 1 Street, N.W., 10th Floor

Washington, D.C. 20005

(202) 682-1300