Riddick v The School Board of the City of Norfolk Appellants Brief

Public Court Documents

October 29, 1984

75 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Riddick v The School Board of the City of Norfolk Appellants Brief, 1984. 294d196e-c29a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/7ab4bb7b-a094-43c0-af7f-c5de2bf3f0f5/riddick-v-the-school-board-of-the-city-of-norfolk-appellants-brief. Accessed February 25, 2026.

Copied!

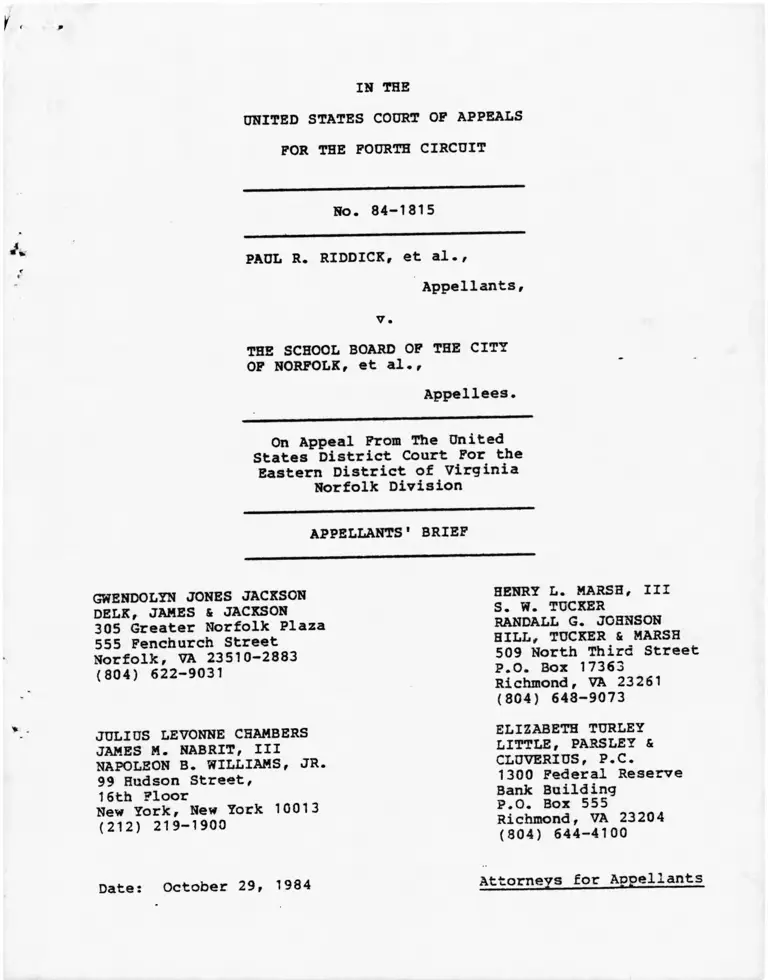

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

NO. 84-1815

PAUL R. RIDDICK, et al.,

Appellants,

v.

THE SCHOOL BOARD OF THE CITY

OF NORFOLK, et al.,

Appellees.

On Appeal From The United

States District Court For the

Eastern District of Virginia

Norfolk Division

APPELLANTS' BRIEF

GWENDOLYN JONES JACKSON

DELK, JAMES & JACKSON

305 Greater Norfolk Plaza

555 Fenchurch Street

Norfolk, VA 23510-2883

(804) 622-9031

JULIUS LEVONNE CHAMBERS

JAMES M. NABRIT, III

NAPOLEON B. WILLIAMS, JR.

99 Hudson Street,

16th Floor

New York, New York 10013

(212) 219-1900

Date: October 29, 1984

HENRY L. MARSH, III

S. W. TUCKER

RANDALL G. JOHNSON

HILL, TUCKER & MARSH

509 North Third Street

P.O. Box 17363

Richmond, VA 23261

(804) 648-9073

ELIZABETH TURLEY

LITTLE, PARSLEY &

CLUVERIUS, P.C.

1300 Federal Reserve

Bank Building

P.O. Box 555

Richmond, VA 23204

(804) 644-4100

Attorneys for Appellants

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Table of Authorities ..................................

QUESTIONS PRESENTED ...................................

STATEMENT OF THE CASE .................................

A. Procedural History of the Riddick

Action ......................................

B. Background of the Riddick Action ...........

C. The Beckett Action ..........................

STATEMENT OF THE FACTS ................................

A. The Board's New Neighborhood School Plan ....

B. History of Desegregation in Norfolk ........

Educational Deficiencies ..............

C. School and Housing Segregation .............

D. The Desegregation Period ....................

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT ...................................

ARGUMENT ..............................................

POINT I

IN DISMANTLING THE CURRENT BUSING DESEGRE

GATION PLAN AND IMPLEMENTING A NEIGHBORHOOD

SCHOOL ATTENDANCE PLAN, THE SCHOOL BOARD HAS

DEFAULTED ON ITS AFFIRMATIVE CONSTITUTIONAL

OBLIGATIONS AND HAS PERPETUATED THE EFFECTS

OF THE PRIOR DE JURE DUAL SYSTEM OF PUBLIC

EDUCATION IN NORFOLK ............................

A. Applicable Legal Principles ...............

1. The Nature of the Affirmative Con

stitutional Obligation ...............

£221

iii

vii

1

1

1

2

5

5

10

10

12

17

20

22

22

22

22

- i -

Page

2. Psychological Effects .................

3. Remedying Educational Deficiencies ...»

4. Reciprocal Effects of Housing and

School Segregation ....................

POINT II

THE DISTRICT COURT ERRED IN HOLDING THAT ITS

1975 ORDER DECLARING THE SCHOOL SYSTEM UNITARY

MADE IRRELEVANT PLAINTIFFS' PROOF THAT THE PRO

POSED NEIGHBORHOOD SCHOOL SYSTEM PERPETUATED

CONTINUING EFFECTS OF THE PRIOR DUAL SYSTEM, AND

REQUIRED PLAINTIFFS INSTEAD TO PROVE THAT THE

BOARD'S PLAN RESULTED FROM AN INTENTION TO

DISCRIMINATE ON THE BASIS OF RACE ............. '

25

26

28

35

POINT III

THE DISTRICT COURT ERRED IN HOLDING THAT THE

SCHOOL DISTRICT OPERATES A UNITARY SCHOOL

SYSTEM ..................................... 47

POINT IV

THE SCHOOL AUTHORITIES HAVE THE BURDEN OF

PROVING THAT THE SCHOOL SYSTEM IS FREE OF THE

DISCRIMINATORY EFFECTS OF THE DE JURE SYSTEM

AND THAT THEIR NEIGHBORHOOD PLAN WILL NOT PER

PETUATE THE VESTIGES OF THAT SYSTEM ...........

POINT V

THE SCHOOL BOARD'S PROPOSED PLAN IS BASED

UPON AND MOTIVATED BY RACIAL CRITERIA, AND IS

RACIALLY DISCRIMINATORY TOWARDS PLAINTIFFS IN

VIOLATION OF THE RIGHTS OF BLACK CHILDREN UNDER

THE FOURTEENTH AMENDMENT TO THE CONSTITUTION

OF THE UNITED STATES ...........................

52

CONCLUSION

56

65

ii

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Allen v. McCurry, 449 O.S. 90 ( 980) .................. 38,43

Azalea Drive-in Theater, Inc. v. Hanft,

540 F.2d 713 (4th Cir. 1976) .....................

Berry v. School District of City of Benton Harbor,

515 F. Supp. 344 ( W.D. Mich. 1981) ............ 31

Blonder-Tongue Labs v. University of Illinois,

Foundation, 402 O.S. 313 (1971) .................. 40,42,44

Page

Bradley v . Milliken, 620 F.2d 1143 (6th Cir.), 50cert . denied, 449 U.s. o/u ( ............

Brose av. Sears, Roebuck & Co., 455 F.2d 763 . ' 39(5th CXIT • \ *3 ! £ ) •••■•*********

Brown v . Board of Education (Brown I), 347 U.S. . 22,25,59483

Brown v . Board of Education (Brown II), 349 U.S. 22294

Carson v. American Brands, Inc., 654 F.2d 300 43( 4th

Chambers

364

v. Hendersonville City Board of Education, 53F . 2d 1 by ( 4tn Cir . * • • • ............

Columbus Board of Education v. Penick, 443 U.S. 22,24449

Cromwell 41V. Sac, 94 U.o. 331 { lo/o/ ............

Davis v.

721

East Baton Rouge Parish School Board, 60F.2d 1425 (3tn Cir. 1500/ ............

Dayton Board of Education v. Brinkman (Dayton II), 23,24,304 4 3 34,55,57

Deposit Guaranty National Bank v. Roper, 445 U.S. 463 26

Eisen v.

( 1 9

Carlisle & Jacquelin, 417 U.S. 156 43

- iii -

Evans v. Buchanan, 583 F.2d 750 (3rd Cir. 1978),

Cert, denied sub nom. Delaware State Board

of Education v. Evans, 446 D.S. 923 (1980),

rehearing denied, 447 U.S. 916 (1980) ......

Flinn v. FMC Corp., 582 F.2d 1169 (4th Cir. 1975),

cert, denied 424 U.S. 967 (1976) ...........

Goss v. Board of Education of City of Knoxville,

Tenn., 444 F.2d 632 (6th Cir. 1971), cert,

denied, 414 U.S. 1171 (1974) ................

51

44,45

50

Green v. County School Board of New Kent County,

391 U.S. 430 (1968) .......................

Hansberry v. Lee, 311 U.S. 32 (1940) ..........

Kaspar Wire Works, Inc. v. Leco Engineering &

Mach., Inc., 575 F.2ds 530 (5th Cir. 1978)

Keyes v. School District No. 1, Denver, Colo.,

413 U.S. 189 (1973) .......................

. 22,23,49

. 44,46,47

37,38,39,40

22,23,48,55

Lee v. Macon County Board of Education, 465 F.2d

369 (5th Cir. 1972) ...........................

Lee v. Macon County Board of Education, 616 F.2d 805

(5th Cir. 1980) ...............................

Lemon v. Bossier Parish School Board, 444 F.2d

1400 (5th Cir. 1971) ..........................

Mapp of Chattanooga,

1971), aff'd 477v. Board of Education of City

329 F. Supp. 1374 (E.D. Tenn. ■ => /

F.2d 851 (6th Cir.) (per curiam), cert, denied

414 U.S. 1022 (1973) .........................

Marshall v. Holiday Magic, Inc., 550 F.2d 173 (9th

Cir. 1977) ...................................

Miller Brewing Co. v. Jos. Schlitz Brewing Co., 605

F.2d 990, 996 (7th Cir. 1978) ................

50

43

38,39,40

Milliken v. Bradley (Milliken II, 443 U.S. 267

(1977) ..................................

Mullaney Central Hanover Bank & Trust Co., 339

U.S. 306 (1950) .........................

24,25,26,27

47

iv

Page

Regents of the University of California v. Bakke,

438 U.S. 265 (1978) ........................

Ross v. Houston Independent School District, 699

F.2d 218 (5th Cir. 1983) ...................

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education

402 U.S. 1 (1977) ..........................

59

50

3,23,24

28,49,52,55

United Airlines, Inc. v. McDonald, 432 U.S.

385 (1977) .....................................

United States v. Davis, 460 F.2d 792 (4th Cir.

1972) ..........................................

United States v. International Building Co., 345

U.S. 502 ( 1 953) ............................ ....

United States v. Jefferson County Board of Education,

380 F.2d 385 (5th Cir.), cert, denied, 389

U.S. 840 (1967) ................................

United States v. Scotland Neck City School Board,

407 U.S. 484 (1972) ............................

United States v. Texas Education Agency, 647 F.2d

504 (5th Cir. 1981), cert, denied sub nom.

South Park Independent School District v.

United States, 102 S. Ct. 1002 (1982) .........

Valerio v.

(N.D.

Vaughns v.

County

Boise Cascade Corp., 80 F.R.D. 626

Cal. 1978) .........................

Board of Education of Prince George’

, 574 F. Supp. 1280 (D. Md. 1983) ..

s

Villaae of Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan Housing

Development Corp., 429 U.S. 252 (1972) .......

Washington v. Davis, 426 U.S. 229 (1976) ..........

Wright v. Council of City of Emporia, 407 U.S.

451 (1972) ....................................

Zablocki v. Redhail, 434 U.S. 374 (1978)

46,47

41

36,40-

27

59

49

43

50

57,60

57,60,64

24

46,47

- v -

Page

References to Beckett v. School Board of the City

of Norfolk and to Brewer v. School Board of

Norfolk are made continually throughout the

Brief .......................................

- vi -

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

I.

Does a consent decree which specifies that a formerly de

jure racially segregated school system is unitary and which was

entered without the consent of all parties and without notifica

tion to absent class members, operate to dissolve an injunction

against the school board or otherwise serve to eliminate the

board's burden to justify subsequent creations of single race

schools?

Did the district court err in permitting a school board with

a history of opposition to Brown to reestablish a system of

racially segregated schools for more than 47% of its black

elementary children?

III.

Whether a formerly de j ure segregated public school system

can abandon a plan which desegregates the school system in favor

of a neighborhood school assignment plan that resegregates the

school system through intentional discriminatory official acts

and through official acts perpetuating adverse effects of the

School Board's previous operation of segregated system?

vii -

IV.

Can a school board which actively participated in interlock

ing relationships with various governmental agencies to create

racial segregated housing and segregated schools resegregate

those particular schools on the basis of the segregated housing

it created.

V.

Do community opposition to desegregation and white flight

constitute valid justifications for establishing racially

segregated elementary schools?

VI.

Whether the district court made the requisite findings of

fact required by Rule 52(a) of the Federal Rules of Civil

Procedure?

- viii

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

A. Procedural History of the Riddick Action

This action was commenced on May 5, 1983 by black pupils

enrolled in the public school system of Norfolk, Virginia.

Plaintiffs sought to enjoin implementation of a pupil assignment

plan adopted by the School Board on February 2, 1983, which

terminated busing of elementary pupils for desegregation and

assigned students in elementary grades to neighborhood schools.

Plaintiffs assailed the plan on the grounds that it violated the

Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United States,

and prevented the School Board from carrying out its affirmative

duty to eradicate the effects of past discriminatory action from

the Norfolk school system.

The District Court entered a final order on July 9, 1984.

holding that the pupil assignment plan was not unconstitutional.

The court denied the request of plaintiffs that injunctive relief

be granted and that the order of the court, dated February 14,

1 9 7 5 , in Beckett v. School Board of the City of Norfolk, be set

aside. (A. 1997) An appeal from the order was taken on August 8,

1984. (A. 1998)

B. Background of the Riddick Action

Plaintiffs' complaint (A. 8) was filed following a motion

filed by the School Board in Beckett seeking declaratory relief

that the plan was constitutional, and following a complaint

1 See ___

F. Supp.

rec-ited

Beckett, et al School Board

the

of the

history120 (E.D. Va. 1967) and

therein at 269 F. Supp at 120, n,

Citv of Norfolk, 269

of'the Beckett case

1 .

1

School Board of the City of Norfolk v.filed by the Board in

Bell et al. , Civil Action No. 83-225-N, (E.D. Va.), seeking the

2same relief.

The Bell action was voluntarily dismissed. The School

Board's motion in Beckett was withdrawn pursuant to an under

standing that the issues raised therein would be raised in

Riddick.

C. The Beckett Action

Beckett was a class action commenced by black school

children on May 10, 1956, see, Beckett v. School Board of the

City of Norfolk, Va., 148 F. Supp. 430 (E.D. Va.), aff'd, 246

F.2d 325 (4th Cir. 1957), cert, denied, 355 D.S. 855 (1957)

(following intervention by additional black plaintiffs, the case

was captioned Brewer v. School Board of the City of Norfolk)) ,

see Brewer, supra, 349 F .2d 414 (4th Cir. 1969), to enjoin the

School Board from maintaining a dual school system and to provide

students with a desegregated education. The United States

intervened as a plaintiff. This Court held in Brewer, 343 F.2d

408, 41 0 ( 4th Cir. 1970), cert, denied, ____ U.S. ----, 90 S.Ct.

2247, that the evidence "clearly depicts a dual system of schools

based on race." 2

2 The School Board's motion in Beckett, supra

Bell, supra, were filed intheDistrict

T51TT.

and its complaint in

Court on March 23rd,

2

The district court's initial plan to redress the constitu

tional violation was rejected by this Court on the ground that

the plan excluded blacks from integrated schools on account of

their race , assigned blacks to schools which were not middle

class schools (and which by the Board's own standards were deemed

to be inferior schools), 3 preserved the traditional racial

characteristics of Norfolk's schools, and failed to create a

unitary school system in Norfolk. 434 F.2d at 411.

The district Court was ordered to "enter an order approving

a plan for a unitary school system" and to have the plan "remain

in full force and effect, regardless of appeal, unless it is

4

modified by an order of this Court." 434 F.2d at 412.

On a subsequent appeal, the judgment of the district court

was again vacated and the district court was ordered to have the

School Board draw up a plan of desegregation conforming to

guidelines laid down in Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board_of

5

Education, 402 D.S. 1 (1971).

The plan of the School Board rejected by the Court of Appeals was

based upon the principle, which the District Court found sup

ported by the evidence, that "pupils do better m school with a

predominantly middle class milieu" and that white pupils

Generally are middle class, and black pupils general are a

lower socio-economic class." Brewer, supra, 434 F.2d at 411.

See Beckett, 302 F. Supp. 18, and 308 F. Supp

opinions of the district court precipitating the

by the Court of Appeals.

This Court, in Brewer, supra, directed the

and the School Board to ^wnsider the use of all

, 1274, for the

above decision

district court

techniques for

3

On remand, the district court adopted a desegregation plan

which paired and clustered various schools in the Norfolk school

district, and assigned some students to schools beyond walking

distance from their homes. The order was modified on appeal to

provide for free transportation. Brewer,456 F.2d 943.

On February 14, 1975, the district judge, John A.

MacKenzie, entered an order dismissing the Beckett action with

leave to reinstate upon good cause. The order was entered

pursuant to the consent of plaintiffs and defendants. The United

States, the third party to the action, did not sign the consent

order, and was not notified that the parties had submitted a

proposed order of dismissal. The joint request for an order of

dismissal, submitted without supporting documentation and entered

without hearing, argument, or notification to class members,

recited the following:

It appearing to the Court that all issues in

this action have been disposed of, that the

School Board of the City of Norfolk has

satisfied its affirmative duty to desegregate,

that racial discrimination through official

action has been eliminated from the system,

and that the Norfolk School System is now

"unitary," the court doth accordingly

ORDER AND DECREE that this action is hereby

dismissed, with leave to any party to rein

state this action for good cause shown.

desegreaation." 444 F . 2d at 101. The_ only techniques of

desegregation used, however, by the district court were those

identified by the Court of Appeals in the Brewer opinion,

namely, the "pairing or grouping of schools, noncontiguous

attendance zones, restructuring of grade levels, and the trans

portation of pupils." Brewer, 444 F.2d 99, 101 (1971). See,

also Brewer, 456 F.2d 943, 945 (4th Cir. 1972).

4

Counsel for plaintiffs and defendants signed the decree with a

statement "We ask for this." The consent decree did not indicate

6

that the outstanding injunction would be dissolved or modified.

Thereafter, Beckett remained dormant until the School Board filed

a motion for a declaratory judgment that its neighborhood school

attendance plan was constitutional.

STATEMENT OF THE FACTS

A. The Board's New Neighborhood School Plan

The pupil assignment plan adopted by the Board on February

2 , 1983 is similar the freedom of choice plan rejected by the

Court of Appeals in Brewer, 397 F.2d 37 (4th Cir. 1965). It has

two principal features. First, it terminates the School Board's

program requiring the busing of elementary students for degrega-

7

tion. Secondly, with few exceptions it assigns, elementary

8

students, grades K-6, to neighborhood schools. (A. 2000). The 6 7 8

6 The effect of the consent decree was to clear the court's docket,

an administrative convenience. Nothing in the order suggested

that the oustanding injunction would be dissolved or modified.

7 There are 36 public elementary schools in Norfolk. The elemen—

tary grades are defined as the Kindergarten grades through the

sixth grade. At the time of trial, there were fourteen (14)

single attendance zone schools. Students attending these schools

are not bused for desegregation. The remaining twenty-two (22)

schools participate in the busing program for desegregation.

8 Additional features of the plan include a majority-minority

transfer provision pursuant to which students in schools in which

persons of their race constitute 70% or more of the enrollment

can transfer to a school, and obtain free transportation thereto,

where the percentage of students of his or her race is less than

5

resolution of the School Board adopting the plan recited that the

action was taken on the basis of an "extensive review of current

practices of student assignments ... to determine if it is

desirable and prudent to reduce the cross-town busing of younger

9children."

The Board's plan creates ten (10) elementary schools in

which the enrollment will be 95% or more black. (A. 2010) The

busing plan now in effect has no elementary school with an

enrollment in which 95% or more of the students are black. (A.

2288-92) The school system in 1 983 had 20,681 (58%) black

elementary students and 13,327 (42%) white students. (A. 2296)

The Board's plan distributes the students into ten schools with

an enrollment of 97% or more black. These schools with their

actual enrollment for 1 970 and 1 973 and their proposed 1984

enrollment under the board's plan are as follows: 9

or equal to 50%. (A. 2005). The Board estimates that if a

maximum of 18% of the black students in schools over 70% black

transfer to schools enrolling over 50% white students, then ten

schools in the system will be 97% or more black. (A. 2010a)

The plan also include a multicultural program under which

children in racially isolated black schools will, through video

and other means, obtain inter-racial exposure to white children.

(Ap. 2010g)

9 The resolution recited that the new assignment plan was "in the

best interests of all Norfolk Children and holds the greatest

promise of affording those children a quality education in a

unitary and truly desegregated school system." (A. 2000)

6

School Percent Black Percent BlackSchool

Prop. Prop.

1970 1983 1984 1970 1983 1984

Bowling Park 57 81 100% Roberts Park 100% 77 98%

Chesterfield 93 70 99% St. Helena 100% 58 99%

Diggs Park 100 67 97% Tidewater Park 100% 69 100%

.Tarfix 65 98% Tucker 100% 47 98%

Monroe 99 63 99% Young Park 100% 57 100%

(A. 2261-4, A. 2290-•92, A. 2298-2302) .

These schools have an enrollment of 97% or more black students

with or without the majority -minority transfer program (A.

2298-2301)

The Board's plan creates, out of a white elementary pupil

population of 42*, ten schools having a 64% or greater white

enrollment.10 The schools, are listed in the chart below:

Percent Percent

School White School White

Bay View 85% Sewells Pts 66%

Camp Allen 64% Sherwood For. 70%

Little Creek 72% Tarrallton 78%

Oceanair 71% Willoughby 64%

Ocean View 83%

(A. 2298-2302).

10 The Board claims that if 18% of the black students in schools

enrolling over 70% black pupils take advantage of the majority

minority transfer provision, then only five schools will have a

white enrollment exceeding 64%. The schools are Bay View (74%),

Little Creek (65%), Oceanair (69%), Sewells Pts (66%, and

Sherwood For. (65%). (A. 2010a)

7

The ten schools with a black enrollment exceeding 97% have

11

40% of Norfolk's black elementary students. (A. 2010) No

significant number of white students are expected to seek

transfers pursuant to the majority-minority transfer program.

(A. 289-90).

The Board's plan creates twelve schools with an enrollment

of 70% or more black students.12 (A. 2313). The twelve schools

constitute 33% of Norfolk's elementary schools and contain 5,721

black students, or 47.1% of the black elementary pupils in the

school district. Id.

Under the current plan, four schools, in 1983 and 1984, had

black enrollment-of more than 70%. The four schools represent

10% of the elementary schools and contain 1.586 students, or

13.7% of the black elementary students.

In 1 970, one year before adoption of the current plan, 32%

of all elementary schools had a black enrollment of 70% or more.

(A. 2313). The Board's plan would make, 33% of the elementary

schools have 70% or more black enrollment in 1984.

11 The Board says that under its plan students assigned to all black

schools obtain the advantages of a desegregation education

through a multicultural program which will provide occasional

opportunities, involving the use of video programs and other

means, for students of different races to come into contact with

one another. (A. 2010g)

12 These schools include schools previously identified herein as

having more than 97% black enrollment and also include Lindenwood

(79% minority) and Willard (74%) elementary schools, (A. 2010)

Exhibit 151 has prepared u n d e , the _5SS Board's plan would be in effect in 1984. Thus, the statistics

Drovided in its summary for the year 1984 are statistics appl

able to the Board's proposed plan and not the current plan.

8

The Board's plan creates approximately the same percentage

of schools with an enrollment of 95%, or more, black students as

existed in 1 970, the year prior to the start of desegregation.

(A.2317). The ten schools which, under the Board's plan, have

95% or more black enrollment are the same school that had a black

enrollment of 95% or more in 1970. (Ex. 149, A. 2310).

The ten (10) racially isolated schools which, under the

board's plan, are 95% or more black constitute 28% of all

elementary schools, enroll 4,738 black students, and contain 40%

of all black elementary students. Similar statisties existed

prior to the implementation of the current plan, when there were,

in 1970, 16 racially isolated schools which constituted 30% of

the elementary schools and enrolled 8,889 black students. Thus,

under the Board's plan, schools which were segregated in 1970

will mostly be segregated in 1984-85.

When the Board adopted its neighborhood school plan, overall

black enrollment had leveled off at 58%,13 14 15 black enrollment had

declined continuously over a twelve-year period with 24,000

black pupils in 1969 and 20,191 black students in 1983 (Ex. 145,

A. 2296), white enrollment had increased, from 14,427 in 1981 to

14,611 in 1983 (Ex. 145, A. 2296), and overall enrollment of

13 There were no racially isolated black

desegregation process from 1971 to 1984.

schools throughout the

(Ex. 153, A. 2317)

14 (A. 2296).

15 id.

9

1 6

elementary students was projected to increase with 11,814 k-3

students in 1982 to 13,825 k-3 students in 1988. See Ex. 146, A.

2297.

Following the institution of this action, the School Board

delayed implementation of its neighborhood school plan from the

1983-84 school year to 1984-85. (A map of the single-attendance

zones proposed for 1983-84 is in Agreed Exhibit 1-3 and a map of

the zones for 1984-85 is in Agreed Exhibit 1-C.)

When the neighborhood school plan was adopted, the Board

simultaneously rejected an alternative plan, designated^ as Plan

II,16 17 which reduced the length of bus rides for all children who

were bused, assigned children to schools near their homes, and

eliminated racially isolated schools. Insufficient support at

public hearings was the reason given by the Board for rejecting

Plan II. (Transcript Johnson - A. 331, McLaulin - A. 451).

B. History of Desegregation in Norfolk

Educational Deficiencies

The effects of the dual school system existing prior to 1971

continued to exist before and after the school system was

declared unitary. When the Norfolk school system was declared

unitary in 1975, SRA achievement test scores for black students

in the 2nd, 4th, and 6th grades were 19, 17 and 17 percentile

points respectively, or several points below the 20-24 percentile

16 Id. See, Ex. 146, A. 2297.

17 Plan II is described in Appendix pp. 2376-8, 2392-3

10

points achievement test scores for black students in the period

of segregation preceding the adoption in 1971 of the current

desegregation plan. (Ex. 43, A. 2141-2). Even two years after

the school system was declared unitary, achievement test scores

for black 4th and 6th grades were 1-2 percentile points below

their pre-desegregation level. (Ex. 43, A. 2141-2). Throughout

this two year period, black achievement scores fluctuated between

17 and 19 percentile points. _Id. (Ex. 43, A. 2141-2).

Similarly, before 1971, the gap between black and white

achievement test scores for the 2nd, 4th, and 6th grades, was 21

percentile points. (Ex. 43, A. 2141-42, p. 25.) When the

district court, in 1975, however, found the school system

unitary, the gap had actually increased to 22, 20, and 26

percentile points respectively for the 2nd, 4th and 6th grades.

As late as 1978-79, the gap in achievement test scores between

black and white students remained at the pre-desegregation levels

of 1968-70. Id. Achievement test scores for black elementary

pupils reached their lowest level since 1965 in 1973-74, the year

before the school system was declared unitary, (A. 2142) and

1 8 Black achievenment test scores only began to rise above their

pre-desegregation level years after the 1975 order when, in

1978-79 or 1979-80, they ranged from 24 percentile points to 32

percentile points. This rise in test scores coincided with the

first use bV the Board, in 1979, of a special education program,

namely the Competency Challenge program, to raise achievement

test scores. (Ex. 43, A. 2141-2).

11

during 1974-75, when the school system was declared unitary,

black achievement test scores reached their second or third

lowest level since 1965. (A. 2139).

C. School and Housing Segregation

During the period of de jure racial segregation, the School

Board took a number of steps affecting the location of housing

sites for black and white parents of school-age children in

Norfolk. Included among these steps were numerous letters by the

School Board to the Norfolk Redevelopment and Housing Authority

in which the School Board "confirm(ed) conversations concerning

the interlocking of our school program with your double program

of redevelopment of slum areas and construction of housing on

vacant land sites." 19 (Ex. 218(c), p. 8; Ex. 218(d), p. 8; Ex.

19 m a letter dated August 7, 1952, for example the School

Board notified the Norfolk Redevelopment and Housing Authority,

with respect to the area bounded by Fenchurch St., Wood St.,

Tidewater Dr., and City Hall Avenue, that it "confirms conversa

tions concerning the relationship between your three contemplated

slum site housing projects and our school program. (Ex.

last page) . The letter noted that the Authority propose to

erect approximately 630 dwelling units for Negro occupancy ...

(and) to displace 75 white and 479 Negro families. Id.

The Board's letter suggested that since "(t)he Henry Clay

School at the intersection of Fenchurch and Holt Streets is

attended by white children," and that "since your housing program

will substantially eliminate all white families in the area, it

will be logical to convert the Henry Clay School for the use of

negro children", and that it should be done "coincidentally with

the completion of your projects." Id.

After noting that the Henry Clay School had an exclusive

white enrollment of 250 pupils, the School Board assured the

Housing Authority that although the Authorities was placing 151

more negro families on the site of the two projects than will be

displaced, the net addition of 250 Negro school seatings will

considerably alleviate present overcrowding in existing Negro

schools in the areas." Id.

12

218(e), p. 8; A. 2432; Ex. 218(i), last page; Ex. 218(k), last

paqe; A. 2454—5; Ex 218(v), p. 1)*

The School Board's committment to the projects was made at a

time when the Housing Authority was noting, with respect to the

projects, that "(s)ince Negro projects ... have already absorbed

all vacant land suitable for low-rent Negro housing, any future

20

projects will have to be built on slum land." (Ex. 218(h), p. * 20

A similar pattern of involvement between the School Board

and the Housing Authority occurred on other housing prefects.

Concerning redevelopment and construction work by the Housing

Authority in a number of areas in Norfolk, the School Board, by

letter dated February 15, 1950, notified the Authority that its

"program ... entails a considerable redistribution of families

and school population" but that the School Board appreciated

that new facilities are necessary in slum areas to make them

suitable for re-use." (Ex. 218(c), p. 8).

The assurances were given concerning housing construction

and work in the areas of Roberts Park, Marshall Manor, Princess

Anne Road and Broad Creek Road west of the City Line,

Chesterfield Heights, Campastella, and the area around

Monticellow Ave. and Church St., Elmwood Cemetery, and Brambelton

Avenue. (Ex. 218(c), Ex. 218(d), p. 8).

20 The Housing Authority frequently performed its responsibilities

in accordance with racial criteria. For example, on April 3,

1951, the Authority made the following comment:

The 12 white families eligible for public

low-rent housing will be rehoused in this

Authority's 400-unit project VA-6-8 ... The

269 eligible Negro-families will be relocated

largely on proposed project site. This will

be accomplished ... in stages.

(Ex. 218(h), p. 11). In the same April 3, 1951 report, a

revision of one of the Authority's Development Program, the

Authority wrote that "there are presently under construction two

white projects." (Ex. 218(h), P. 12).

In

project

measures

a previous development program concerning the same

the Authority noted that the School Board had taken

to reduce enrollment in the nearly "Negro" Titus school

13

4, Ex. 21 8(i), P. 4).

A proposed school building program for Norfolk in January

1949, provided that "(a) new school for Negro children should be

built in an area where new housing is constructed for those moved

from the slum clearance area" and that "(t)his should be a part

of the slum clearance program." (A. 2452-3). On December 28,

1950, the School Board, in a letter from its superintendent,

notified the Housing Authority that as a result of the

Authority’s redevelopment work near Tidewater Drive, the school

system was "confronted with the need for additional facilities

for Negro children in this neighborhood or the transfer of the

building now used by the white children for use by Negro". (A.

2456).

During the 1950’s, 5,014 black families were displaced

through the work of the Norfolk Redevelopment and Housing

Authority.21 * * (Transcript 1590). This represented almost 29% of

all black households in Norfolk. (A. 759, A. 2402)

During the 1960's before Norfolk was desegregated, 1,764

black families, or 8.5% of black families in Norfolk, were

displaced from their homes. (A. 760, A. 2402). From 1950 to

but that the Authority's "contemplated relocation of some 1200

families from the center of the city to the outskirts will

further contribute to the decongestion of the Negro school system

in the area." (Ex. 218(i) , p. 6).

21 Approximately, 2,800 housing units were ^ilSlace-their construction occurred subsequent to the initial displace

ment. (Transcript 1590-1592).

14

1982, approximately 9,416 black households were displaced in

Norfolk (A. 2402).

Twenty-five percent (25%) of Norfolk's black school children

reside in public housing and have had the location of their homes

determined by site selection decisions of public bodies of

Norfolk.22 The black population of Norfolk from 1960 to 1980

ranged from 25.8% to 35%. (A. 46). Sixty-three percent (63%) of

the households displaced from 1 950 to 1 980, however, were black

households.23 (A. 758, 2402) Most of the schools built from 1974

to 1984 were built either in the redevelopment areas or on the

property of the U.S. Navy. (A. 1339)

The displacement of residences through urban redevelopment

and the concomitant location of schools in the vicinity of public

housing projects occurred, in many instances, when both state law

and Norfolk local law required streets, blocks, and districts to

24be racially segregated. (Ex. 343, 344) A. 2508).

22 Housing projects are located in areas that are predominantly

black (A. 748-750). Norfolk's housing projects house

25.3% of black familes in Norfolk. Id. Ninety-two percent of

public and subsidized family units in Norfolk are occupied by

blacks, (A. 747), and 40% of black renter households

live in public housing. (A. 751).

23 From 1960 to 1980 when blacks and other familes were displaced

from their homes, the number of owner-occupied units in Norfolk

increased by 432 units but the number of owner-occupied units in

nearby Virginia Beach increased by 39,813 units and in Chesapeake

the number of owner-occupied increased by 13,000 units. (Tran

script 1541-42, Ex. 169C). 24

24 chapter 157 of Pillard’s Code Biennial 1912, adopted on March 12,

1912, required residential districts to be designated as white

or "colored" and further provided that "it shall be unlawful for

any colored person, not then residing m a <Hs£rict so define-d

and designated as a white district ... to move into and occupy as

15

Approximately thirty (30) of Norfolk's public elementary

schools were constructed during the period when chapter 157 and

§3046 were effective. (Ex. 164F, 214).25 26 Two of the elementary

schools which have an enrollment equal to or greater than 95%

black under the Boards neighborhood school plan were built during

2 6

the time when state and local law required housing segregation.

(Ex. 164F).

Nine of the elementary schools with a black enrollment of

95% or more are located near public housing projects. (A. 782-4)

Eight of the nine schools were constructed when Norfolk's school

system was segregated.27 (Ex. 164F). Eight o£ the schools were

a residence any building or portion thereof in such white

district (Ex. 343 ). This provision was extended by the

Virgin ia*leg islature in the Virginia Code of 1942 Cities and

Tbwns-General Provisions § 3046, and maintained until the Code of

1959. (Ex. 343).

white not then residing

a district so

move into and occupy

thereof, in such colored

of March 12, 1912.

m

toThe statute similarly prohibited "anydefined and designated as a colored district

as a residence any building, or portion

district." Ex. 343, paragraph 4 of Act

Norfolk adopted, on June 19, 1911, a ordi-

nance implementing the discriminatory provisions of Chapter 157

of Pollard's Code of 1912. See Code of 1920, Chapter 7.

25 Exhibit 214 is a list of schools and the dates of their original

construction.

26 Chesterfield and Tucker were opened respectively in 1920 and

1940.I VJ •

27 The eight schools are Chesterfield ( 1920), Tucker <1942), Bo

Park (1953), Diggs Park (1953), Young Park ( 1954), Roberts

(1964), Tidewater Park (1964), and St. Helena (1966).

Bowline

Par)

16

built near or adjacent to housing projects built in or prior to

1955.28 (A. 782-4, Ex. 164F). They were built during a time when

the United States Department of Housing and Urban Development

found that "rigid patterns of segregated public housing exist m

Norfolk," (A. 2519-20) and that the Norfolk Housing Authority was

not in compliance with the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Id.

Between 1971 and 1980 when the present desegregation plan

was in effect, the neighborhood of Norfolk became somewhat more

integrated. The black population of Norfolk was dispersed

throughout the city to an extent greater than it had been during

preceding decades although not dispersed enough to bring about

fully integrated neighborhoods. (A. 775-6).

D. The Desegregation Period

During the implementation of the court-ordered dessegrega-

tion plan of 1971, defendants submitted several reports contain

ing data on school enrollment figures and employment of faculty

and administrative personnel. (Def. Ex. 38, A. 2574). The

reports were submitted only from 1971 to 1974. These reports

28 chesterfield elementary lies adjacent to Grandy Park

(1953); Tucker school lies adjacent to Oakleaf Park (

Diggs Park (1952); Bowling Park school is adjacent to

project (1952); Diggs park school is near Diggs Park

?1952); Young Park is adjacent to Young Park project

Roberts Park school is near Roberts Park project

Tidewater Park school is adjacent to Tidewater Par

(1955); and Jacox school lies adjacent to Roberts Par

Roberts East (1953), and Moton Park projects (1962).

proj ects

942) and

Bowling

project

(1953);

(1942);

proj ect

(1942),

(Ex. 164F)

29 There were approximately nine such "reports." (Def. Ex. 38, A.

2574). The first report, dated October 2 , 1972, contained

statistics on pupil enrollment and professional employment. Id.

TheSecond report contained data relating to a school lor

students who were drop-outs. The third was a 1 972 report which,

17

were the basis for the district court's decree in 1975 that the

Norfolk school system was unitary and that the action in Beckett^

supra, should be dismissed. No information on the progress of

efforts to deal with school drop-outs or disciplinary problems

30

was presented by the Board to the court.

like the above-described 1971 report, contained enrollment and

employment data for Norfolk's public schools. The fourth report

was a supplement to the 1972 report and contained a summary of

the racial distribution in the school system of principals an

assistant principals by race.

The fifth report was a letter, dated February 23, 1973, fro™

defendants' counsel to the District Judge, informing the court

that the School Board proposed to conduct renovation and con

struction at five sites and that judicial approval of their

actions was not required. The sixth report was a letter dated

June 29, 1973 advising the district court of the Board s plan to

institute a kindergarten program for the 1973-74 school year and

that court approval was not required.

The seventh report was a letter which notified the district

court, on January 1 1 , 1 973 that improvements and alterations

would be made to one high school and two elementary schools, and

that court approval of the projects was not required. The eighth

and ninth reports were 1973 and 1974 school reports providing

statistics on enrollment and employment m the school system.

The reports described herein were contained in Exhibit 38

which defendants presented in evidence on June 11, 1984, three

months after trial. They were presented during the course of

oral argument. Plaintiffs were not presented with an opportunity

to rebut the impact of these reports through additional evidence

3 0 The only information received by the district court, prior to the

court's order declaring the school system unitary, concerning e

school's system's efforts in dealing with drop-outs and discipli

nary problems was contained in a report outlining admission

guidelines, student rights, and student responsibilities in

"transition" school established by the Board, after August 4,

1 972, for school drop-outs. (Ex. 38). The district court

entered an order on August 4, 1972 authorizing the School Board

to establish a transition school. Id. Plaintiffs in Bec|e|^ had

objected to the creation of the transition school on the ground

that it would further segregation. The district court overrule

the objections. (Ex. 38).

18

During the 1971-1975 period, no reports were presented to

the district court on residential segregation, remedial educa

tional programs, counseling programs, parental involvement,

educational background of parents (see, Ex. 194), magnet schools,

achievement test scores, educational gains, educational programs,

or the promotion of desegregation of neighborhoods. (A. 286)

When the district court ordered the defendants to desegre

gate the school system in 1971, white enrollment had fallen from

59.7% in 1966 to 51.9% while black enrollment increased, during

the period, from 40.3% to 48.1. (Ex. 38, A. 2580). For 1971-72,

the enrollment in elementary schools was 50% white and 50% black.

(Ex. 38, A. 2577). By September 30, 1974, four and a half months

before the district court's February 14, 1975 unitary decree,

white enrollment in the elementary schools had fallen to 49% and

black enrollment had risen to 51%. (Ex. 38, A. 2618). For the

total ten-year period, from 1966 to 1975, white enrollment in the

Norfolk school system decreased from 59.7% to 49%, a total of

10.7 percentage points. From 1975 to 1983, white enrollment

decreased from 49% to 42%, a total of seven percentage points.

( E x . 1 4 5 ) .

From 1971 to 1975, the period in which the school system was

under supervision by the district court, the number of black

segregated elementary schools having a black enrollment 15%

higher than the district mean only decreased from seven (7)

schools to five (5) schools, or less than 29%. (A. 2305-11).

19

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

The district court below misapprended the applicable legal

principles and criteria for determining the constitutional

vaidity of the actions of the Norfolk School Board in implement

ing a geographical attendance plan and terminating a cross town

busing plan for desegregating the elementary schools.

During the past 29 years this School Board has established a

history of resistance to the implementation of the decision in

Brown v. Board of Educatin. More than 30 years after Brown, the

district court approved a plan which permits the school board,

after a short period of desegregation during which the vestiges

of the former dual system were not eliminated, to reestablish a

sytem which perpetuates the effects of the board's past discrimi

nation by assigning more than 47% of its black elementary

children to racially segregated schools and 40% to racially

isolated schools.

The district court erred in holding that a former de jure

segregated public school system can abandon a plan which desegre

gates the school system in favor of a geographical assignment

plan that resegregates the school system through intentional

discriminatory official actions and through official actions

perpetuating the adverse effects of the School Board's previous

20

operation of its segregated system. The court erred in holding

that a School Board which actively participated in an interlock

ing relationship with other governmental agencies to create

racially segregated housing and segregated schools will be

allowed to resegregate those particular schools when the segre

gated housing remains intact.

The district court erred in deciding that a consent decree

which specifies that a former de ;jure racially segregated school

system is unitary when said decree was entered without consent of

all parties and without notification to absent class members,

operated to dissolve an injunction against the school board and

otherwise to eliminate the board's burden to justify the creation

of single race schools. Because of this error, the court

improperly shifted the burden from the perpetrators of the

unconstitutional conduct to the victims of the conduct.

Finally, the district court erred in deciding that white

community opposition to desegregation and white flight constitute

a valid justification for establishing racially segregated

schools and in refusing to make findings of fact required by Rule

52(a) of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure.

21

ARGUMENT

POINT I

IN DISMANTLING THE CURRENT BUSING DESEGREGA

TION PLAN AND IMPLEMENTING A NEIGHBORHOOD

SCHOOL ATTENDANCE PLAN, THE SCHOOL BOARD HAS

DEFAULTED ON ITS AFFIRMATIVE CONSTITUTIONAL

OBLIGATIONS AND HAS PERPETUATED THE EFFECTS OF

THE PRIOR DE JURE DUAL SYSTEM OF PUBLIC

EDUCATION IN-NOFFOLK.

A. Applicable Legal Principles

■j # The Nature of the Affirmative Constitutional

Obligation

This Court, in Brewer v. School Board of the City— of

Norfolk, supra, 434 F . 2d at 410, found that the Norfolk School

Board operated a statutory dual system of public education for

black and white school children at the time Brown v. Board_of

Education (Brown I), 347 U.S. 483 ( 1 954 ), was decided. The

School Board therefore had an "affirmative duty 'to effectuate a

transition to a racially nondiscriminatory school system.'" Keyes

v. School District No. 1, Denver, Colo., 413 U.S. 189, 200 (1973)

quoting Brown v. Board of Education (Brown II), 349 U.S. 294, 301

(1955). Since Brown I, Norfolk's Board of Education "has been

under a continuous constitutional obligation to disestablish its

dual system." Columbus Board of Education v. Penick, 443 U.S.

449, 458 (1979).

The scope of the Board's affirmative duty to disestablish

the dual system has been set forth in general terms in numerous

Supreme Court opinions. In spelling out the extent of this

constitutional obligation, the Supreme Court, in Green v. County

22

School Board of New Kent County, 391 U.S. 430 (1 968), said that

"(s)chool boards ... operating state-compelled dual systems were

clearly charged with the affirmative duty to take whatever

steps might be necessary to convert to a unitary system in which

racial discrimination would be eliminated root and branch. Ic3.

391 U.S. at 437-38.

To insure that school boards have enforced their affirmative

obligation to root out racial discrimination, the Supreme Court

has required offending school boards to satisfy three essential

conditions. First, the school board must eliminate from the

public schools within its jurisdiction "all vestiges of state-

imposed segregation." Swann, supra, 402 U.S. at 15.

Second, as part of its affirmative obligation, the Supreme

Court has stated that a school board must not "take any action

that would impede the process of disestablishing the dual system

and its effects." Dayton Board of Education v. Brinkman (Dayton

II), 443 U.S. 526, 538 ( 1 979). Third, the Court has emphasized

the "affirmative responsibility" of a school board "to see that

pupil assignment policies ... 'are not used and do not serve to

31 under Green, supra, and the later cases, a unitary school system

was defined as one in which racial discrimination had been

"eliminated root and branch." See, also, Columbus Board ,P_1

Education v. Penick, 443 U.S 449, 458-59 (1979); ^ v- School

pi strict" No. 1, Denver, Colo_._, supra, 413 U.S. at n. 11 (19 ),

Swann v.' Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education, 402 U.S. 1, 15

(1971 )~.

23

perpetuate or re-establish the dual system.'" Dayt?j? XI' suP^a'

443 O.S. at 538, quoting Columbus Board of Education v._Penick_,

443 U.S. at 460.

Where a school board's actions continues, or increases, the

effects of the dual system, the Court has said that the board has

a "heavy burden" in justifying its actions. Dayton II, 443 U.S.

at 538. Also, see Wright v. Council of City of Emporia, 407 D.S.

451, 467 (1972). In determining whether a school board has

carried out its constitutional obligations, the Supreme Court has

pointedly emphasized that "the measure of the post-Brown I

conduct of a school board under an unsatisfied duty to liquidate

a dual system is the effectiveness, not the purpose, of the

actions in decreasing or increasing the segregation caused by the

dual system." Dayton II, 443 U.S. at 538.

Cases such as Dayton II, Green, and Swann demonstrate that a

school board's affirmative duty in effectuating a transition to a

unitary school system and in "disestablishing the dual system and

its effects," Dayton II, 443 D.S. at 538, requires it "to do more

than abandon its prior discriminatory purpose." Id. Ultimately,

the Court has held, the school board must take action which will

"restore the victims of discriminatory conduct to the position

they would have enjoyed in terms of education had ... (their

education) been provided in a nondiscriminatory manner in a

school system free from pervasive de j ure racial segregation."

Milliken v. Bradley (Milliken II), 443 U.S. 267, 282 (1977).

24

To restore black schoolchildren to the condition in which

they would have been absent racially segregated schools, the

following three conditions, arising as a result of a <3e jure

racially segregated schools, must, at a minimum, be redressed:

(1 ) psychological injury to black and white schoolchildren; (2 )

inferior education for black children; and (3) residential

segregation in the school district.

2. Psychological Effects

In Brown v. Board of Education (Brown I), 347 O.S. 483

(1954), the Court made an explicit finding that racial segrega

tion inflicts upon black children "a feeling of inferiority as to

their status in the community that may affect their hearts and

minds in a way unlikely ever to be undone." Brown I, supra, 347

U.S. at 494. In the Court's subsequent decision in Milliken II,

the Supreme Court found that "children who have been thus

educationally and culturally set apart from the larger community

will inevitably acquire habits of speech, conduct, and attitudes

32 In the trial below, Dr. Robert Green, an eminent educational

psychologist who testified in Milliken v. Braaley, 433 U.S. 267

(1977) and in numerous other school desegregation cases, testi

fied that a de jure racial education results in inferior educa

tion for blacks and creates adverse mental attitudes that

detract from the ability of the child in later life as a parent

to help his or her children in providing educational _ support such

as assisting in homework or in transmitting educational values.

(A. 557-61).

Dr. Green also testified that implementation ̂ of the Board s

plan would have a "negative impact" upon black children in their

education, self-image, and in their aspirations m later life.

(A. 552-56, 565-66).

25

Milliken II, 433 U.S. atn 33

reflecting their cultural isolation."

287. These holdings, or findings, of the Supreme Court are

binding upon this Court and cannot be successfully assailed by a

School Board seeking to default upon its constitutional obliga

tion. The Court also found in Milliken II, supra, that "pupil

assignment alone does not automatically remedy the impact of

previous, unlawful educational isolation." Id.

3. Remedying Educational Deficiencies

Norfolk's dual school system caused both psychological

injury to black children and educational deficiencies. In

Milliken II, the Supreme Court held that there are "built-m * 33

inadequacies of a segregated educational system." Id., 433 U.S.

at 284. As a result of these inadequacies, racially segregated

school systems often cause black pupils to have "significant

deficiencies in communications skills-reading and speaking." Id.,

at 290. AS a result of these deficiencies, black schoolchildren

33 ThP Court in Milliken II also found that black schoolchildren^ who

attended a de jure segregated school system were^

acquire speecTThablti, for example, which vary from the environ

ment in which they must ultimately function and compete, if t ey

are to enter and be a part of that community. _ Id. 433 U.S. at

287 Moreover, the Court noted,"speech habits acquired in a

segregated system do not vanish simply by moving the child to

desegregated school." Id. 433 U.S. at 288.

26

"experience the effects of segregation until such future time as

... remedial programs can help dissipate the continuing effects

of past misconduct." Milliken II, 433 U.S. at 290.

The inclusion of educational components in a school desegre

gation decree* 35 forms an integral part of a program for compens

atory education to be provided Negro students who have long been

disadvantaged by the inequities and discrimination inherent in

the dual school system . " 36 Milliken II, 433 U.S. at 284. The

remedial and counseling educational components upheld in Milliken

II are generally "deemed necessary to restore the victims of

discriminatory conduct" to the positions they would have had in

the absence of discrimination. Id_. 433 U.S. at 282.

34 The existence of the above stated pernicious effects from a dual

school system simply show that "past discriminatory student

assignment policies can themselves manifest and breed other

inequities built into a dual system founded on racial discrimi

nation." Milliken II, 433 U.S. at 283.

35 The lower federal courts have been warned by the Supreme Court

that they "need not, and cannot, close their eyes to inequali

ties, shown by the record, which flow from a longstanding

segregated system." Id. 433 U.S. at 283. To protect the victims

of” racial discrimination and to insure that they are restored to

their "rightful place," federal courts must fashion judicial

decrees in school desegregation cases which are aptly tailored

to remedy the consequences of the constitutional violation.

Milliken II, 433 U.S. at 287.

36 -rhe use of educational components such as compensatory programs

as desegregation tools was first approved by the Supreme Court in

Milliken II, supra, and had been in existence at^least 5°UI;_years

prior to the time when the district, m 1971, failed to include

the educational components in its desegregation plan. See United

states v. Jefferson County Board of Educatio^, 380 ~ T T 2 d 3«b,

394-395 ( 5th Cir.) , cert, denied 389 U.S. 84(5 0 967) .

27

4. Reciprocal Effects of Housing and School Segregation

The third condition to be remedied in the transition from a

dual system to a unitary system is the impact of residential

segregation upon schools and vice versa. One basic finding in

Swann is that school policies in building schools and filling

them "may well promote segregated residential patterns which,

when combined with 'neighborhood zoning,' further lock the school

system into the mold of separation of races." Swann, 402 U.S. at

2 1.

The Supreme Court said in Swann that the location of schools

during a period of de jure racial discrimination will "influence

the patterns of residential development of a metropolitan area

and have important impact on composition of inner-city neighbor-

37hood." Swann, 402 D.S. at 20-21.

Because of the ripple effect of school segregation upon

housing segregation and housing segregation upon school segrega

tion, freedom of choice plans and neighborhood school plans, as

we]_l as other forms of racially neutral pupil assignment plans,

are disallowed as desegregation plans, and are deemed inadequate,

when they "fail to counteract the continuing effects of past

school segregation resulting from discriminatory location of

school sites." Swann, supra, 402 U.S. at 28. 37

37 The Court stated in Swann that "(p)eople gravitate towards school

facilities, just as schools are located in response to the needs

of people." 402 U.S. at 20.

28

Applying these principles to the instant action the black

plaintiff school children proved at trial that the School Board

failed to carry out its affirmative obligations, and that both

the School Board and the District Court below failed to comply

with the order of this Court requiring the District Court to

"enter an order approving a plan for a unitary school system and

to have the order "remain in full force and effect ... unless it

is modified by an order of this Court." Brewer v. School Board

of the City of Norfolk, supra, 434 F.2d at 410, 412.

The undisputed evidence adduced at trial shows the follow

ing: (1 ) that appellees' neighborhood pupil assignment plan

creates ten (1 0 ) racially isolated black elementary schools

containing approximately 40% of all black elementary public

schoolchildren in Norfolk; (2) that the schools containing 95% or

greater black enrollment under the Board's plan are, with few

exceptions, the same schools which had 95% or greater black

enrollment prior to 1971; (3 ) that nine of the elementary schools

having a black enrollment greater than or equal to 95% are

located near public housing projects whch were (a) built and

located in accordance with de_ jure racial criteria or (b) placed

near elementary schools that were located and occupied in

accordance with de jure racial criteria; (4) the percentage of

elementary schools under the Board's plan having a black enroll

ment of 9 5 % or more is approximately the same percentage of

elementary schools in 1971 having a black enrollment of 95% or

29

more; and (5) that there were no racially isolated black elemen

tary schools in Norfolk throughout the thirteen year period from

1971 to 1984. (Ex. 153, A. 2317).

These discriminatory results of the Board's action in

terminating the busing desegregation program and adopting a

neighborhood school attendance plan, show that the Board's

actions violate its obligation "to see that pupil assignment

policies ... 'are not used and do not serve to perpetuate or

re-establish the dual system," Dayton II, supra, 443 U.S. at 538,

and violate its obligation to avoid "any action that would impede

the process of disestablishing the dual system and its effects."

Id.

Moreover, the Board's action impedes the dismantling of

Norfolk's dual school system, and its effect, by inflicting

adverse psychological and educational harm upon the 40% of black

elementary students assigned to schools where black enrollment

exceeds 95%.

Dr. Green testified that the Board's plan will cause

psychological harm to black children at a time when they are most

susceptible to learning, that the plan will adversely affect

racial attitudes, and that it will create psychological distance

between black and white schoolchildren. (Ex. 167, A. 2389-90; A.

551-56, A. 577-78). Dr. Robert Crain further testified that the

board's desegregation plan will deprive 40% of Norfolk's black

30

elementary schoolchildren of the advantages of desegregation at

the time when school desegregation has the maximum positive

impact upon learning, namely, in grades K-3. (Rec. 1058, A. 617).

Both Dr. Green and Dr. Crain testified that the Board's plan

will perpetuate the effects of the prior dual school system by

placing in racially black isolated schools those black pupils

whose parents obtained an inferior education under the de jure

system and who, as a consequence, are less able to provide needed

parental support to help their children in educational matters

such as homework, home study, or other methods to help them

slough off the adverse psychological and educational effects

resulting from the Board’s plan. (A. 558-561, A. 624-25). Even

the Board and its educational experts concede that homework, home

intervention, and the home environment are among the most vital

factors having a positive contribution upon the child's ability

3 8to learn. (A. 2527-28).

Plaintiffs Exhibit 194, showing the years of education

completed for whites and blacks in Norfolk in 1960, further

demonstrates that blacks in Norfolk have completed less years of

38 Appellees' expert Herbert Walberg introduced an exhibit which

purports to determine, in numerical terms, the influence of

various factors which have an impact on learning. {A. 2 5 2 1 28).

Without conceding the accuracy of Walberg s ranking/ thatPfIctSrS of the various educational factors, appellants note that factors

relating ̂ o individualized parental support are listed as being

among the most important whereas being in a homogenous g r < J f

listed as having a minor effect and the use of television, which

would presumably include the video programs described in

appellees' multicultural program, is described as having

negative effect. (A. 2527-28)

31

education than whites in Norfolk at every level, or grade, of

education. Appellees' plan perpetuates this result. Evidence

presented at trial showed, on the basis of studies of the

long-range effects of desegregation upon black schoolchildren,

that black children attending desegregated schools and classes

are less likely to drop out of high school or college, and that

39

they do better upon graduation from college. (A. 626-29).

Moreover, the failure of the Board to incorporate remedial,

or compensatory, educational and counseling components into the

1971 desegregation plan and to hold off instituting^ special

educational programs, such as the 1979 Competency Challenge

program which could reduce the black-white achievement gap or

otherwise raise black achievement test scores, will further

aggravate the effects of the prior dual system upon black pupils

whose parents obtained a racially de jure segregated education in

Norfolk in the fifties and sixties, if the Board's plan is

implemented

Dr. Albert L. Ayars, past superintendent of the Norfolk

school system for 11 years and the only recipient of both the

Leadership for Learning Award and the Distinguished Service Award

39 Studies of the effects of desegregated schools upon black

schoolchildren also show that such children, as adults, get

better jobs, have less trouble with the police, have higher

incomes, obtain more desegregated jobs, complain less about

working with white superivisors, and are more likely to live in

integrated housing. (A. 627-628). See Crain, R.; Hawes, J.;

c ^ 4-+- p • PA-irhprt. J. : The Lonq Term Effects of an Educationalinitial Remits Prom A btudv ot Desegregation

(April," 1$63), published by Center for social organization or

Schools, John Hopkins University.

32

from the American Association of School Administrators, testified

that Norfolk's black-white achievement gap is a legacy of past

racial discrimination but that continued implemention of the

current busing plan would substantially decrease the extent of

the gap. (A. 1 66-67 ). By terminating the busing plan and

adopting a pupil assignment plan which resegregates the school

system at 1970 levels, the Board violates its constitutional duty

not to perpetuate the effects of Norfolk's prior dual system of

public instruction.

Professor Yale Rabin, associate professor of urban and

environmental planning and associate dean of school of architec

ture at the University of Virginia, offered evidence showing that

the Board's neighborhood school plan perpetuates the effects of

past residential segregation caused by school and other public

authorities.40 * He testified that the current busing plan "assured

the maintenance of a stable racial balance in the schools and

made the schools no threat to whites living in desegregated

neighborhoods whereas the proposed neighborhood school plan "will

provide an impetus to the accelerated transition of those

neighborhoods from part white" and will cause whites living there

to flee to all-white neighborhoods. (A. 788-89). Similar

40 professor Rabin testified that "patterns of racial segregation

which exist in the City of Norfolk have been substantially

influenced and reinforced by the actions of government agencies

here in the city over a long period of time." (A. 786). See also

pp A 773-74 where professor Rabin demonstrates how school and

housing authorities in Norfolk followed a general plan to develop

a neighborhood-based city plan in which racial criteria were

used, in the 60's, to designate neighborhoods.

33

testimony was given by Dr. Crain. (A. 658 61). The Board s

plan reverses the desegregation which has occurred in residential

areas, (A. 647) and tends to destabilize neighborhoods which,

under the current plan, have been stable, (A. 1950), thereby

42

perpetuating the effects of past unlawful discrimination.

Overall, the Board's neighborhood school plan would serve to

perpetuate the effects of past discriminatory conduct by (1 )

resegregating schools previously segregated before 1971; (2)

forcing 40% of the black elementary students in the school system

to suffer the same psychological and educational problems and

deficiencies their parents suffered under Norfolk's dual system;

(3) widening the black-white achievement gap; and (4) resegre

gating neighborhoods and otherwise impeding the further desegre

gation of neighborhoods in Norfolk. These actions of the Board

add up to a violation of its "affirmative responsibility to see

that pupil assignment policies ... are not used and do not serve

to perpetuate or re-establish the dual school system." Dayton

II, supra, 443 U.S. at 538.

41 Appellees offered no evidence showing that the current busing

plan has segregated neighborhoods or would, if continued,

segregate neighborhoods. Appellees limited their contentions in

this lawsuit to the claim that the current busing plan would, if

continued, resegregate schools, not neighborhoods. 42

42 Evidence presented at trial showed that "cities which have a

school desegregation plan in place are desegregating their

housing at three times the rate that school districts are doing

that do not have a school busing plan in effect." (A. 658 659)

34

POINT II

THE DISTRICT COURT ERRED IN HOLDING THAT ITS

1975 ORDER DECLARING THE SCHOOL SYSTEM UNITARY

MADE IRRELEVANT PLAINTIFFS' PROOF THAT THE

PROPOSED NEIGHBORHOOD SCHOOL SYSTEM PERPE

TUATED CONTINUING EFFECTS OF THE PRIOR DUAL

SYSTEM, AND REQUIRED PLAINTIFFS INSTEAD TO

PROVE THAT THE BOARD' S PLAN RESULTED FROM AN

INTENTION TO DISCRIMINATE ON THE BASIS OF

RACE.

The District Court held that proof of continuing effects of

past discrimination and the perpetuation of these effects by the

Board's proposed neighborhood school plan, were irrelevant to the

proceedings below because the effect of the 1975 court order

declaring the school system unitary and dismissing the Beckett,

or Brewer, action was "to shift the burden of proof from the

defendant School Board to the plaintiffs, who must now show that

the 1983 Proposed Plan results from an intent on the part of the

School Board to discriminate on the basis of race." In adopting

this standard as the measure of constitutionality validity of the

Board's action in terminating crosstown busing and adopting a

neighborhood school assignment plan, the Court misapprehended

applicable legal principles determining when preclusive effect is

to given to prior judgments and, thereby, erred as a matter of

law.

The opinion of the district court holding that Black

children were precluded by the 1975 decree from contesting

recitals in that decree that the school system was unitary, that

35

the effects of prior discrimination had been eliminated, and that

the school system had satisfied its affirmative obligations,

violates every known, established legal principle.

First, the record demonstrates that the February 1 4, 1975,

Beckett order by the District Court was based upon the consent of

the parties and was not a judgment rendered by that court

pursuant to an evidentiary hearing conducted by it and was not

based upon any evidentiary materials presented to the Court for

its consideration by the parties. See Beckett Docket. (A.

2574). In the federal courts, a judgment based upon consent has

no collateral estoppel effect. S e e , United--stateg— ^

International Building Co., 345 D.S. 502 (1953). The Supreme

Court held in United States v. International Building Co., supra_,_

that:

A judgment entered with the consent of the

parties may involve a determination of

questions of fact and law by the court. But

unless a showing is made that that was the

43 The District Judae stated, in an ambiguous section of the

opinion, that he could not "agree with the present efforts of

plaintiffs to label the February 14, 1 975 Order as a Consent

Decree," but then went on to state that the "(t)he language of

the Order of February 14, 1975 was fully agreed to by counsel for

plaintiffs and defendants." T h e short of the matter, however, is

that, as is indicated in the District Court's opinion itself,

plaintiffs' and defendants' counsel in Beckett submitted the

proposed order to the district court, without any supporting

affidavits or papers or even a notice of motion or a motion, and

then said, at the end of the proposed order "we ask for this and

affixed their names, namely Henry L. Marsh, III and Allan G.

Donn. Such actions clearly evidence that the 1975 order was a

consent order, that is, a judgment entered upon the consent of

the parties affixing their signatures to it. As a consent order,

however, the order has no collateral estoppel effect. United

States v. International Building Co., supra.

36

case, the judgment has no greater dignity, so

far as collateral estoppel is concerned, than

any judgment entered only as a compromise of

the parties. 44 _Id. 345 U.S. at 506.

Second, as a consent judgment, the 1975 order was defective

because it required the consent of all parties. Only two,

however, of the three parties signed the proposed consent

judgment. The United States did not sign and was not notified

that the parties were submitting, or had submitted, a proposed

judgment of compromise and dismissal. A consent judgment which

is not based upon the consent of all parties to a suit who are

affected by the judgment, is void or voidable since the consent

which would give the judgment life and efficacy was not forth

coming. A fortiori, a purported consent decree which does not

have the consent of all affected parties is not entitled to get

preclusive effect through collateral estoppel.

Third, the 1975 decree neither dissolved nor purported to

dissolve the previous injunction which the District Court issued

in 1971 in obedience to the order of this Court. Although the

effect of the 1 975 dismissal was, as an administrative matter,

to clear the district court's docket, it left the injunction

outstanding. Language far more explicit than that contained in

the 1 975 decree is necessary to dissolve an outstanding in-

j unction.

44 See also, Kaspar Wire Works, Inc, v

Mach ine, Inc., 575 F .2d 5 3 0, 539 (5 th

Federal Practice, fl 0.443(3), p. 3909.

Leco Engineering and

Cir. 1 978')"; IB Moore's

37

Moreover/ nothing in the four corners of the consent decree

suggests or implies that the injunction outstanding was, or