Rabinowitz v. United States Supplemental Brief for Appellee

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1963

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Rabinowitz v. United States Supplemental Brief for Appellee, 1963. 9775c4b7-c19a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/7ad648e5-382f-4dcb-b078-0093b2830d85/rabinowitz-v-united-states-supplemental-brief-for-appellee. Accessed February 04, 2026.

Copied!

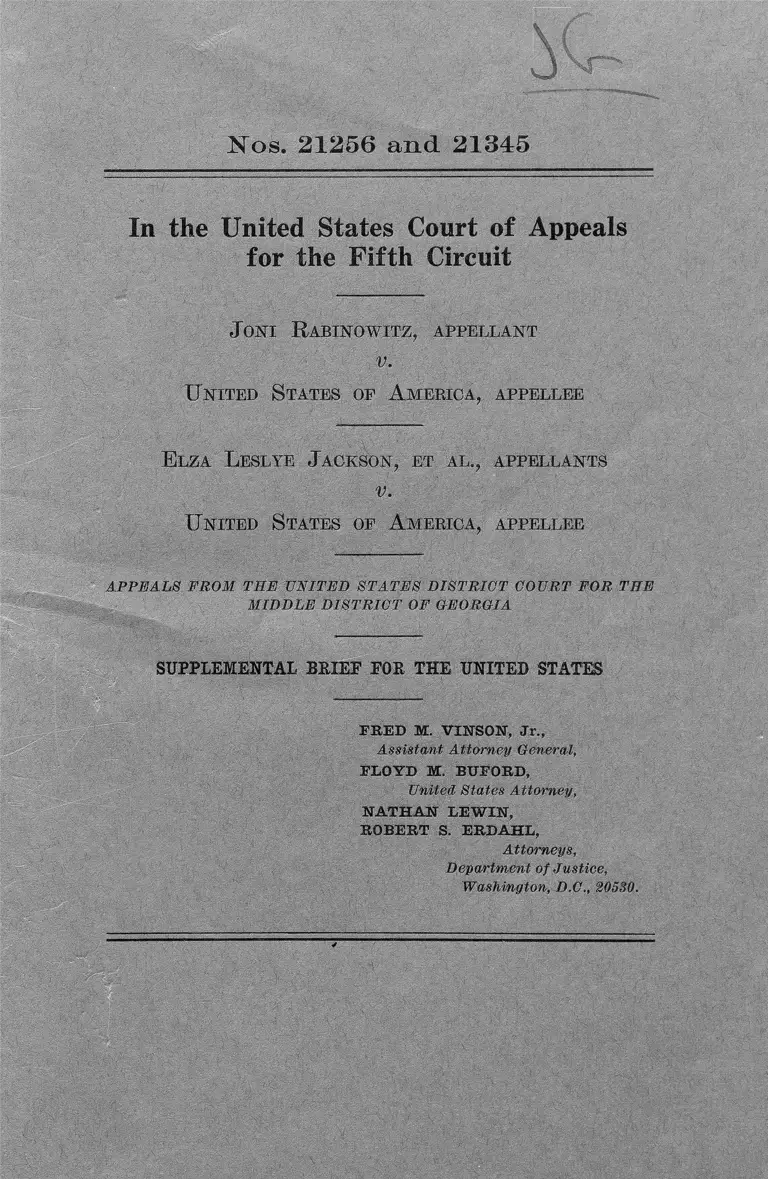

N os. 21256 and 21345

In the United States Court of Appeals

for the Fifth Circuit

J oni R abinowttz, appellant

V .

U nited S tates of A merica, appellee

E lza L eslte J ackson, et al., appellants

v.

U nited S tates of A merica, appellee

A PPE A LS FROM TH E UNITED STATES D IS T R IC T COURT F O R TH E

M ID D LE D IS T R IC T O F GEORGIA

SUPPLEMENTAL BRIEF FOR THE UNITED STATES

F R E D M . V IN SO N , Jr.,

A ssistant A ttorn ey General,

F L O Y D M . B U FOR D,

United States A ttorney,

N A T H A N L E W IN ,

R O B E R T S. E R D A H L ,

A ttorneys,

D epartm ent o f Justice,

W ashington, D.C., S0530.

I N D E X

Pag*

'Statement_________________________________ 1

I . Census data concerning the Macon Division----- 2

II . The jury commission____________________________ 3

I I I . Standards used by the jury commission for com

piling the jury list----------------------------- -------------- 4

IV . Procedures by which the 1959 jury list was com

piled_____________________________________________ 6

A . The 1953 list_____________________________ 6

B. Compilation of the 1959 list-------- „ --------- 7

1. Commissioner’s method-------------- 7

2. Clerk’s method__________ ________ 8

3. Questionnaires_______ ______ _— 9

V . Results___________________________________________ 10

V I . Explanations offered for results----------------------- - 12

VTI. Actual service by Negroes as jurors,-------------------- 13

V I I I . The district court’s ruling________________________ 14

Discussion________________________________________________________ 16

Introduction_________________________________________________ 16

I. It is only purposeful exclusion from jury service

because of race or other similar status which

contravenes constitutional and statutory stand

ards_______________________________________________ 17

A . The constitutional ground______ ._______ 18

B . The statutory ground___________________ 28

II . The procedures for compiling the jury list be

low met constitutional and statutory standards, 33

I I I . In the particular circumstances of this case, the

addition of only four new Negro names in the

compilation of the 1959 jury list and the fail

ure during the period involved to make further

affirmative efforts to add additional Negro

names to the list leads us to suggest that this

court, reverse the convictions in the exercise of

its supervisory power____________________________ 38

796^ 006— 65 ---------- 1 (I)

II

C IT A T IO N S

Qages • Page

Akins v. Texas, 325 U .S. 358--------------------------- 2 2 ,2 3 ,2 4 ,2 7 ,3 4

Arnold v. North Carolina, 376 U .S . 773--------------------------- 24

A very v. Georgia, 345 U .S . 559— ------------------------------------ 24

Ballard v. United States, 329 U .S . 187------------------ 28 ,30 ,31 ,33

Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U .S . 497----------------------------------------

v. Allen, 344 U .S . 443-------------------------------------- 21 ,23 ,27

Brown v. Ae-io Jersey, 175 U .S . 172--------------------------------- 18

5y^ C a rter v. Texas, 177 U .S . 442------------------------------------------ 21

C W eB v. 339 U .S. 282____________________ 2 5 ,26 ,27 ,42

Chamce v. United States, 322 F.2d 201, certiorari denied,

379 U .S . 823____________________________________________29,32

Commonwealth v. Wright, 79 K y. 22,42 Am.Rep. 203— 22

Delaney v. United States, 199 F.2d 107------------------------- 19

Dow v. Caimegie-Illinois Steel Corporation, 224 F.2d

414, certiorari denied, 350 U .S . 971----------------------- 29 ,30 ,31

. F ay v. New York, 332 U .S . 261------- 1 7 ,2 0 ,2 1 ,2 2 ,2 3 ,2 7 ,3 6 ,3 7

^A F rqzer v. United States, 335 U .S. 497------------------------------- 30

Glgsser v. United States, 315 U .S. 60-------- : ----------------- -— 30

Goldsby, United States ex rel. v. Harpole, 363 F.2d 71— 42

Kayes v. Missouri, 120 U .S . 68---------------------------------------- 18

xyH ernandez v. Texas, 347 U .S . 475----------------------------- 21 ,24 ,26

l^ K i l l v. Texas, 316 U .S . 400----------------------------------------------- 24,26

H o yt v. Florida, 368 U .S . 57-------------------------------------------- 27

International Longshoremen's <& Ware. Unions. Acker

man, 82 F . Supp. 65------------------------------------------------------- 21

Legmllou, United States ex rel. v. Davis, 115 F . Supp.

9 2 . 21

iPM artin v. Texas, 200 U .S . 316------------------------------------------ 23

Need v. Delaware, 103 U .S . 370---------------------------------------- 21,22

orris v. Alabama, 294 U .S. 587-------------------------------- 24 ,26 ,33

Northern Pacific B .R . Co. v. Herbert, 116 U .S . 642------- 18

y ^ O f fu t t v. United States, 348 U .S . 11-------------------------------- 11

yA 'P adgett v. Buxton-Smith Mercantile Co., 283 F.2d 21,

certiorari denied, 365 U .S . 828------------------------------------ 34

Patton v. Mississippi, 332 U .S . 463-------------------------------- 24

Pierre v. Louisiana, 306 U .S . 354------------------------------------ 24

Rawlins v. Georgia, 201 U .S . 638------------------------------------ 22

^ yR eece v. Georgia, 350 U .S . 85------------------------------------------ 24,26

Respublica v. Mesca, 1 Dali. 73---------------------------------------- 18

Rideau v. Louisiana, 373 U .S. 723---------------------------------- 19

Ill

Cases— Continued Page

l^ ^ S e a le s v. United States, 367 U .S . 203----------------------------- 34

Seals, United States ex rel. v. Wiman, 304 F . 2d 53------- 25,26

Shepherd v. Florida, 341 U .S . 50----------------------------------- 19

, ^ S m i t h v. Mississippi, 162 U .S . 592------------------------------ 23

. S S m ith v. Texas, 311 U .S . 128-------------- ----------------------- 24 ,25 ,26

State v. Lea, 228 La. 724, 84 So. 2d 169, certiorari <--------

denied, 350 U .S . 1007-------------------------------------------------- 22

Strauder v. W est Virginia, 100 U .S . 303-------------- 19 ,20 ,21 ,26

> 4 » t . Alabama, 380 U .S . 202------------------21 ,2 2 ,2 3 ,27 ,2 8 , 34

arrance v. Florida, 188 U .S . 519----------------------------------- 23

TM el v. Southern Pacific Company, 328 U .S . 217---------- 28

2 9 ,3 0 ,3 1 ,37

‘ Thomas v. Texas, 212 U .S . 278-------------------------------2 2 ,2 3 ,2 7 ,34

United States v. Brandt, 139 F . Supp. 349---------------------- 29,31

United States v. Cartadho, 25 Fed; Cas. 312-------------------- IS

fi^H JPited States v. Clancy, 276 F . 2d 617, reversed on

other grounds, 365 U .S . 312---------------------------------------- 31

S ^ U n ited States v. Dennis, 183 F . 2d 201, affirmed, 341

U .S. 494___________________________________- ________ 29 ,30 ,36

United States v. Flynn, 216 F . 2d 354, certiorari denied,

348 U .S . 494____________________________________________ 29

United States v. Foster, 83 F . Supp. 197__--------------------- 29

United States v. Fujimoto, 102 F . Supp. 890____________ 29

tfnited States v. Greenberg, 200 F . Supp. 382_________ 29,31

t̂ r^fjnited States v. Henderson, 298 F . 2d 522, certiorari

denied, 369 U .S . 878___________________________________ 36,37

United States v. Local 36 o f International Fishermen,

70 F . Supp. 782, affirmed 177 F . 2d 320, certiorari

denied, 339 U .S . 947___________________________________ 31

United States v. Boemig, 52 F . Supp. 857_____________ 28

United States v. Roma,no, 191 F . Supp. 772____________ 29

. ^ H n i t e d States v. W ood, 299 U .S . 123----------------------------- 18

Virginia, ex parte, 100 U .S. 339----------------------- ------------ - 20

Walker x. United States, 93 F . 2d 383, certiorari denied,

303 U .S . 644____________________________________________ 34

Windom v. United States, 260 F . 2d 384______________ 34

i^ ^ T o w n g v. United States, 212 F . 2d 236, certiorari

denied, 347 U .S. 1015------------------------------------------------- 31

Constitution:

F ifth Amendment________________ 19

Fourteenth Amendment________________________________ 19

IV

Statutes: p»se

Civil Eights Act of 1957------------------------------------------------- 4 ,32

Code of Ala., Title 30, § 2-------------------------------------------- 18

Code of Md., Article 51, § 2 3 ------------------------------------- 18

28 U .S.C . 1861_______________________________ 1 7 ,28 ,30 ,32 ,36

28 U .S .C . 1863__________________________________________ 30

28 U .S .C . 1864---------------------- -- --------------------------------------- 32

Miscellaneous:

103 Cong. Eec-------------------------------------------------------------------- 32,33

Forsyth, Trial by Jury , 228-230------------------------------------- - 18

1 Pollock and Maitland, History of English Law , 473- 18

Potter’s Historical Introduction to English Law (4th

ed.) 190----------------------------- ----------------------------------------- l g

Thompson & Merriam on Juries, §§ 16, 17-------------------- 18

The Jury System in the Federal Courts, 26 F .E .D .

409___________________________________ 3M °

In the United States Court of Appeals

for the Fifth Circuit

No. 21256

Joxi R abinowitz, appellant

V.

U nited S tates op A merica, appellee

No. 21345

E lza L eslye J ackson, et al., appellants

v.

U nited S tates op A merica, appellee

A PPE A LS FRO M T H E UNITED STATES D IS T R IC T COURT F O R T E E

M ID D L E D IS T R IC T OF GEORGIA

SUPPLEMENTAL BRIEF FOR THE UNITED STATES

STATEM ENT

Both Rabinowitz v. United States, No. 21256, and

Jackson, et al. v. United States, No. 21345, present at

tacks upon the method by which the 1959 jury list was

compiled in the Macon Division of the United States

District Court for the Middle District of G-eorgia.

The appellants in both cases were, in fact, indicted

by the same grand jury, and were tried by petit juries

(i)

2

drawn from the same box. Additionally, the de

fendant in United States v. Anderson, Criminal No.

2222 (which ended in a mistrial), was indicted by

the same grand jury, although tried in the Albany

Division. The record in Jackson (hereinafter desig

nated J.) in regard to the jury challenge consists, by

stipulation, of the record made in Anderson and the

record made in Rabinowitz (hereinafter designated

R .).

I. Census data concerning the Macon Division

As set forth in the 1960 census, the eighteen coun

ties comprising the Macon Division o f the Middle

District of Georgia have a total population of 373,594,

of which 39% are non-white, and a total adult popu

lation of 204,321, of which 35% are non-white.

38.9% of the white population and 11.6% of the Ne

gro population over the age of 25 have completed four

years of high school. Thus, non-whites comprise ap

proximately 11% of those in the Division who have

completed a high school education.1 The median

years of education for urban whites in the Division is

11.7 years; for rural whites, 8.8 years; for urban non

whites it is 6.8 years; for rural non-whites, 5.1 years.

Although levels of income do not reflect with pre

cision the levels o f intelligence or civic interest of the

populace, there is some relationship. In this respect,

the eighteen counties in the Division had an average

1 According to appellant Kabinowitz, Negroes comprise 24.3%

of the population of the division over the age of 25 who are

“ functionally literate” (i.e., have completed five years of

schooling), and 21.9% of those who have completed six years

(No. 21256, App. Supp. Brief, p. 2 ).

3

of 45.4% of families whose total income was under

$3,000, the range on an individual county basis run

ning from a low of 20.6% to a high of 67.2%. Me

dian income by county for all persons, white and non

white, ranged from a high of $3,418 to a low of

$1,537, and for all families from a high of $5,051 to

a low of $1,907. Median non-white personal income

by county ranged from a high of $1,036 to a low of

$657, and non-white family income from a high of

$2,174 to a low of $1,204.

II. The jury commission

William P. Simmons, the jury commissioner at the

time the jury list in question was compiled, is a prom

inent business man who has been very active in civic

affairs. He is a member of the Bibb County Board

o f Education, a trustee o f Wesleyan College, and a

member of the Governor’s Commission on Efficiency

and Economy (J. 175).

John P. Cowart, the clerk, served previously as

Assistant United States Attorney and as United States

Attorney. He was personally appointed as Assistant

United States Attorney by President Roosevelt in

1934, and was appointed United States Attorney by

the same president in 1945. He was appointed clerk

by the court in 1952 (J. 100).

The jury commission worked closely with District

Judge Bootle. Upon appointment as commissioner,

Mr. Simmons was personally instructed as to his du

ties by the judge, and was given a copy of the manu

al for jury selection published by the Administrative

Office of the United States Courts (R. 184). Both

4

the clerk and the commissioner discussed their se

lection procedures with the judge before putting them

into operation (R. 228-229).

III. Standards used by the jury commission for compiling the

jury list

Both the commissioner and the clerk emphasized

in their testimony that they were guided, in compiling

the jury list, by the twin goals of achieving as repre

sentative a list as possible while at the same time pro

viding potential jurors who would be capable of per

forming their duties with understanding, intelligence

and integrity. Thus, the commissioner stated that his

goal was “ an outstanding blue ribbon jury list of peo

ple we thought would perform very good service,”

and as a result, in selecting names, character and

intelligence were taken into consideration (J. 173).

H e pointed out that a lot of people can read and write

but are incapable of imderstanding courtroom pro

ceedings, and an effort was made to avoid add

ing the names of such persons to the list (R. 209).

Hence, the effort was to find persons who were

thought qualified to perform good jury service (R.

183). This was the only limitation, however. The

attempt was made to have all types of vocations and

occupations represented on the list, and to see that

both the Negro race and women were represented (R.

186). In short, it was considered important to ob

tain qualified jurors of each race from every county

(R. 198).

Similarly, the clerk deemed himself governed by

the Civil Rights Act o f 1957 (R. 227). He studied

the Administrative Office manual and the cases cited

therein, and attempted to keep current on the latest

cases in regard to jury selection (R. 228). He tried

for an age balance on the list, keeping in mind the

fact that the very old might be ineligible due to in

firmity, and the very young might be unavailable

because of college or military service (R. 240). He

and the commissioner discussed with the judge the

possibility of omitting certain classes of persons for

whom jury service might be a hardship, such as

nurses and school teachers, but in the end it was

decided that no such class would be excluded (R. 228-

229). Similarly, the deputy clerk, who made in

quiries for potential jurors under the clerk’s instruc

tions, stated that he was looking for good jurors, and

that his idea of a good juror was a person of good

character and intelligence who could understand cases

that are tried in court (R. 263).

While the commissioner believed that it was impor

tant to obtain Negro names for the list, he had no

preconceived notion in regard to the desirable quantum

(R. 216). He did not attempt to achieve propor

tional representation (R. 186-187), but rather he and

the clerk attempted to obtain as many names of quali

fied Negroes and as many names of qualified whites

as they could (R. 187). In like vein, the clerk testified

that he used census figures only to prorate the list by

county, but not to ascertain the Negro percentage of

the population (R. 259).

The clerk also indicated his recognition of the ne

cessity for constant improvements in the selection

techniques, and of the desirability of taking into ae-

796- 009— 65— 2

5

count the latest teachings of the cases on the subject.

However, there are seven divisions in the district, and

it had taken from six to eight months to compile a

separate list for each of the divisions (R. 240).

Hence, he did not deem it feasible to revise the jury

list each time a new case was decided, but instead

felt that the time to take new cases into consideration

was when the jury box was replenished in regular

order (R. 230).

IV. Procedures by which the 1959 jury list was compiled

A. The 1953 list

When the jury list now under attack was compiled

in 1959, the commission started with the list which

had previously been compiled in 1953, taking off the

names of those who were deceased or physically dis

qualified and adding new names (R. 182). There

were 1,897 names on the original 1953 list (R. 220),

and the names of 308 women were subsequently added

when Georgia law (which at the time governed federal

jury qualifications in the district) made them eligible

for service (R. 221). Although they thus started with

about 2,000 names, only about 1,000 were left when

the names of those who had moved, died or aged had

been removed (R. 238).2 Forty of the names on the

list were marked with a “ C” in red crayon (R. 223-

224). The clerk did not know who had thus marked

the list (R. 225), although he speculated that the

purpose was to make certain that the list would be

replenished with Negroes (J. 112). There were other

2 Further analysis of the questionnaires since the hearings

below indicates that at least 1,624 persons on the 1953 list were

sent questionnaires in 1959. See p. 12, infra.

6

Negro names on the list which were not so marked

(R. 251-257), a total of 97 additional ones (R. 285-

286), and possibly more (R. 291).3

B. Compilation of the 1959 list

1. Commissioner’s method

In obtaining names for the 1959 list, the jury com

missioner used two basic sources: the suggestions of

friends whose integrity and opinion he valued, and of

people whom he knew were active in civic life, busi

ness, and church affairs (R. 183). He made general

inquiries, and did not tell the people to whom he

talked that he was developing information for the

jury list, as he did not want to have people say that

they did not want to be on the list (R. 190). He used

this personal inquiry method, rather than availing

himself of such existent lists as those of automobile

owners, telephone subscribers and taxpayers, because

he was not attempting to compile names qua names,

but only the names of those he thought would be

qualified (R. 210). He made inquiries of both

Negroes and white persons, and had occasion to talk

to Negroes frequently (R. 191). For example, he

talked to Negroes who were employed in his own com

pany (as foremen, etc.) (R. 192), although he was not

successful in obtaining very many names from them

(R. 193). He also talked with Negroes in the school

system in Bibb County (R. 191), and made inquiries

among the faculty of the Negro college in Peach

3 Further analysis indicates that the 1953 list as supplemented

contained the names of at least 177 Negroes. See n. 6, infra,

p. 12.

7

Comity (R. 214-215). He was sure that he must

have talked to both, white persons and Negroes in

Crawford County, as he had occasion to see both

fairly frequently (R. 199). Most of his contacts were

white (R. 215). However, in every instance in which

he made inquiries of a white person, he asked for the

names of competent Negro jurors—i.e., those who, like

potential white jurors, met the statutory qualifications

and in addition possessed integrity, good character

and intelligence—if the person could provide him with

any (R. 198).

2, C lerk ’s m ethod

The clerk also had two basic sources for names:

he would call friends and public officials whom he

knew and ask them for suggestions, and he sent his

chief deputy into counties other than Bibb to talk

to people and obtain suggestions (R. 231). He also

used the telephone book, but only as a reminder of

people whom he knew but might have forgotten

(R. 236). In Bibb County he had four or five white

sources, and five Negro sources (J. 110, 121-122).

He also obtained Negro names from white sources.

Two assistant United States Attorneys provided him

with suggestions for prospective Negro jurors (J.

129), and he also obtained suggested names of

Negroes from a state judge, attorneys in practice,

their secretaries, and a former United States At

torney (J. 134-135). He recalled telling some of

his sources to suggest more Negro names to him, as

they had not provided him with enough (J. 135).

He did not rely upon state jury lists as a prime source

of names, even when state qualifications governed

8

9

federal qualifications. His deputy reviewed state lists

at that time, but he did not (J. 108-109).

The deputy clerk got his names primarily from

public officials in the outlying counties (R. 260),

although he also contacted business men, merchants,

and secretaries, in law and business offices (R. 261;

J. 143). When he contacted state officials, they would

use their jury books to make suggestions. They did

not do so exclusively, however, and provided as many

names from memory as from their books (J. 142).

He always asked specifically for ISTegro names (R. 261,

265), and specifically requested that he be provided

with as many Negro names as possible (J. 145). He

asked that he be provided with a representative group

of Negroes, but always particularly mentioned school

teachers (R. 262). From his white sources he ob

tained, for example, the names of those who taught

at the Negro college in Peach County (R. 264). He

did not seek out Negroes to make inquiries from,

since it was his belief that the persons he did talk to

were acquainted with both Negroes and whites (R.

263).

3, Q uestionnaires

After the commissioner and clerk compiled their

separate lists of prospective jurors, they sent out de

tailed questionnaires to those on the combined list.

The questionnaires were sent both to persons whose

names were newly acquired and to those whose names

remained on the 1953 list after it was pruned (R.

237). The commissioner’s recollection was that some

4,000 questionnaires were sent out (R. 187), and the

10

clerk estimated that the number was either 4,000 or

5,000 (R. 237). Of this number, 2,500 or 3,000 were

returned (ibid.);* some were not returned until after

the final list was compiled (R. 238). Some returns

indicated that the persons were disqualified, as, for

example, because o f poor health (R. 189). On others,

the persons would offer information in support o f

Claims that they were unable to serve (R. 239). I f

the clerk and commissioner agreed with the reasons

o f such persons, their names would not be added to

the final list (R. 240). From the questionnaires

which were returned, 1,985 names were finally selected

for the list (R. 237, 239).

One of the questions on the questionnaire inquired as

to race. The commissioner believed that the reason

was to insure that there would be Negroes on the list,

and pointed out that other questions inquired as to

sex and age, two other factors which had to be consid

ered in obtaining a broad representation (R. 188).

The clerk also stated that the question as to race was

to insure that the names of Negroes would be included

on the final jury list (R. 241; J. 132). Race was not

a consideration in determining which names would

actually be placed upon the list; all that was consid

ered was the person’s qualifications (J. 132). The

jury list itself contained no designations in regard

to race (J. 133).

iV. Results

At the time of hearings below, it was agreed, from a

study of the questionnaires returned by those persons 4

4 The actual number returned was 2338. See p. 11, infra.

whose names appear on the 1959 jury list, that Ne

groes comprise 117, or 5.9%, of those on the list. In

connection with the preparation of this brief, we re

quested the United States Attorney to have a fuller

analysis made of all o f the questionnaires returned—-

including those returned by persons who for one

reason or another were not placed on the 1959

list—and to compare the 1959 list and questionnaires

with the 1953 list to determine the number o f carry

overs.5 He has reported the following:

Of the 1985 persons on the 1959 list, 1428 are

carry-overs from the 1953 list and 557 are new names.

O f the 117 Hegroes on the list, 113 are carry-overs

and 4 are new. Of the 1868 persons on the list who

are white or who did not designate their race on their

questionnaires (there are 5 of the latter), 1,315 are

carry-overs and 553 are new. Hence, o f the new

names added to the list in 1959, 553 are white or of

unknown race and 4 are Negroes.

A total of 2,338 persons returned questionnaires in

1959, and of these, 353 were not placed on the list

for one reason or another. Of these 353, 297 were

white, 53 were Negro, and 3 did not indicate their

race (although one of the 3 has been unofficially

identified as a Negro). Of the 353, 196 had appeared

on the 1953 list, and 157 were new names. Broken

down by race, 150 whites were new names and 147

had appeared on the 1953 list, 7 Negroes were new

names and 46 had appeared on the 1953 list, and all

3 unknowns had appeared on the 1953 list. Hence,

5 The 1959 returned questionnaires in the clerk’s possession are

being forwarded to the clerk of this Court.

11

12

Negroes comprised 7 of the 157 new names in this

group.6

Of the 2,338 questionnaires returned, 1,624 were

carry-overs from the 1953 list and 714 were new con

tacts. Of the 1,624 carry-overs, 1,465 were whites or

of unknown race and 159 were Negroes (taking ac

count of the person unofficially known to be Negro,

the count would be 1,464 and 160). Of the 714 new

contacts, 703 were white and 11 were Negro. Hence,

a total of 170 Negroes returned questionnaires in

1959, or 7.3% .of those returned (171 taking account of

the person unofficially known to be Negro), 159 (or

160) being carry-overs and 11 being new contacts.

The 353 persons not placed on the 1959 list were

omitted for the following reasons: .

White Negro Race

unknown

63 4 1

26 9 1

188 24 1

20 0 0

Other (felony conviction, illiteracy, civil service employment, etc.) _ 0 16 0

T o t a l . _____ ______ __________ ___________ _ ------------ 297 53 3

V I. Explanations offered for results

Asked by appellant in No. 21,256 to explain the

small proportion of Negro names on the list, the

commissioner suggested that Negroes, as a group, are

0 It would thus appear that the 1953 jury list as supplemented

contained the names of 177 Negroes: the 113 carry-overs who

appeared on the 1959 list, the 46 carry-overs who returned

questionnaires in 1959 but were not placed on the list, and 18

of the 40 persons on the 1953 list whose names were marked

thereon with a “ C” (see p. 6, supra) and who did not return

questionnaires in 1959 (22 of the 40 did return questionnaires).

13

not as numerically qualified as are whites, and that,

because of lack o f acquaintanceship among Negroes,

it was necessary to rely for suggestions upon those

persons whom he did know and whose judgment and

opinion he respected (R. 215). Asked the same ques

tion by the defendant in Criminal No. 2222, he re

plied that it was a well-known fact that, although

regrettable and unfortunate, “ there is infinitely more

illiteracy among the Negro group,” and hence, nu

merically, there are not as many Negroes who are

qualified in terms of educational standards as there

are whites (J. 174-175). He added that he felt that

his experience as a member of the Bibb County

Board of Education and trustee of Wesleyan College,

as well as his experience as a member o f the Gov

ernor’s Commission, which was making an elaborate

study of the Georgia school system, qualified him to

make this judgment (J. 175).

The clerk stated that he was not sure that he agreed

with the commissioner that the lack of acquaintances

among Negroes was a cause of low representation

(R. 242). Rather, he suggested that it is as difficult

to obtain qualified Negroes to serve as jurors as it is

to obtain qualified women, because, like women,

Negroes do not want to serve as jurors (R. 241).7

VII. Actual service by Negroes as jurors

There were five Negroes on the grand jury which

returned the indictments in these cases. A panel of

7 W e are informed by the United States Attorney that the 1959

list contained the names of 288 women, of whom 200 had been on

the 1953 list as supplemented. A s previously noted, m$ra, p. 6,

the names of 308 women were supplemented to the 1953 list.

796- 00& — 65— 3

14

45 was drawn from the jury box to obtain the twenty-

three grand jurors (R. 424). We are informed by

the United States Attorney that the panel o f 94

drawn from which the juries for all of the trials below

were selected included three Negroes. None were

reached on voir dire in the Rabinowitz trial; from one

to three were reached on voir dire in the separate

trials of the Jackson appellants, but all who were

reached were challenged peremptorily by the Govern

ment. Calling upon this experience in the District

Court going back to 1934, as Assistant United States

Attorney (when his duties included making present

ments to grand juries), United States Attorney, and

clerk, the clerk stated that he could not “ recall many

times, if any, * * * that there weren’t Negroes on

both the grand jury and the petit jury, in not only the

Macon Division but every other division in this dis

trict” (J. 123; see also J. 104). He specifically re

called the recent criminal trial of the mayor of W ar

ner Robins in which a Negro woman had served as a

juror (R. 255-256).

VIII. The district court’s ruling

Judge Bootle ruled in the Rabinowitz case as fol

lows (R. 293-294) :

I am going to overrule this motion. The

Wiman case pays some considerable attention

to percentages, but there are other factors in

the Wiman case in addition to percentages, and

there are differences in the grand jury system

of selection and the result and the percentages

relating thereto in this case and in the Wiman

case.

15

Now just how far the Courts may go in the

future in looking at certain percentages and

saying that will do and that won’t, and how

much emphasis they are going to pay to the

matter of Negroes and Whites and whether

that is the controlling [590] element in the per

centages and in the ratio of representation on

the list I can’t say hut I am satisfied, as counsel

very commendably concedes here, that there

was no intentional discrimination on the part

of the Jury Commissioners in this District.

And while that is not controlling in this case

it is a factor of considerable importance.

There are, perhaps, some practical difficul

ties in selecting juries. For instance, in this

ease I don’t know now how many question

naires were sent out to either White or Ne

groes. I don’t know what the answers were to

those questionnaires. I don’t know how many

Whites or how many Negroes said “ please

don’t put me on the list, please excuse me, my

job will interfere” , how many of them ex

pressed a desire to serve, how many expressed

an unwillingness to serve.

I may say this, that this jury list will be

revised from time to time. I f the Negroes in

this district want to serve they can cooperate

by giving to the Jury Commissioners some reli

able information about themselves so that they

can receive beyond any peradventure of a doubi

all consideration that they are entitled to re

ceive. But that is a matter for the future.

Taking this case as the facts present it and

as the law reads, I think I can not do anything

except overrule this motion.

Now, do you have another one, perhaps a

16

short one? And I may just add to what I

have been saying, I have heard a good bit of

evidence about school teachers. That might

be a good [591] place to go for information,

probably would be, but it is a mighty bad place

to go to get a juror. The school teachers are

so busy that they will offer an excuse if you

happen to get one and he is summoned to court

to serve. I don’t doubt that they have an ex

cuse. They want to go back to the class room.

I have had that experience over and over and,

of course, their excuse would generally he hon

ored if you had enough jurors to serve without

them.

DISCU SSION

Introduction

As the Court will see (infra, pp. 38-42), although

on the first argument of these eases we contended

that the judgments of conviction should be affirmed,

we have, since that time, become aware of new facts

(supra, pp. 11-12), which have persuaded us to suggest

that the Court, in the exercise of its supervisory

jurisdiction, grant appellants new trials.

In this brief, we will first recanvass the cases set

ting out the constitutional and statutory standards for

jury selection. We will then turn to the facts of

these cases as they appear of record and give our

reasons for believing that the court below was cor

rect in concluding on the evidence before it that no

violation of constitutional or statutory standards has

been established. Finally, we will discuss the new

facts which we have discovered—namely, that of 557

new names added to the 1959 jury list over and above

17

those carried over from the 1953 list, only four were

of Negroes—and present to the Court the reasons

why we believe that these facts, in the context of the

importance o f securing adequate representation of

Negroes in the administration of justice, warrant

the granting of new trials.

I

It is only purposeful exclusion from jury service because of

race or other similar status which contravenes constitutional

and statutory standards

There are two grounds upon which the unlaw

fulness of a federal grand or petit jury can be as

serted. The first is constitutional; to prevail upon

this ground, a litigant must establish, as he would

were he challenging a state jury, that the nature of

the jury was such that the submission of his cause

to it for judgment deprived him of due process of

law.8 The second ground is statutory; to prevail,

a litigant must establish that the jury was selected

in violation of the standards set by Congress in 28

II.S.C. 1861 et seq. In essence, however, the same

showing is necessary to establish a case upon either

ground; vis., purposeful discrimination on the basis

of race or other like status, or the adoption and use

of a procedure for obtaining jurors which is in

8 A n attack on a state jury can assert the denial of both

due process and equal protection of the law. See F a y v. New

York , 332 TJ.S. 261, 284 n. 27. In regard to juries, however,

the area of the two constitutional protections Would appear to

be co-extensive. And compare Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U .S.

497, 499.

18

herently and necessarily discriminatory, must be

proved.

A. The constitutional ground

The constitutional principles o f “ due process” and

“ equal protection” guarantee to a litigant a fair trial

by an unbiased and impartial tribunal. Brown v.

New Jersey, 175 U.S. 172, 175; Hayes v. Missouri, 120

U.S. 68, 71; Northern Pacific R .R . Co. v. Herbert,

116 U.S. 642, 646. They do not, either in terms or by

necessary implication, establish any requirement con

cerning the classes of persons to whom jury service

must be open. Indeed, even though a litigant is him

self a member of a class which is excluded from such

service, he does not necessarily have a ground for

constitutional objection. For example, it could

hardly be contended that it is a denial of due process

or equal protection to require an alien or a minor to

submit his cause for judgment to a jury which by law

must be composed of adult citizens. Compare United

States v. Wood, 299 U.S. 123, 145.9 The law, in

9 As W ood points out, aliens were once entitled at common

law to a jury de medietate linguae— one half aliens and the

other half citizens— presumably upon the theory that xenopho

bic bias on the part of citizens was to be presumed. See also

Respublica v. Mesca, 1 Dali. 73 (O . & T. Pa., 1783); United

States v. Gartacho, 25 Fed. Cas. 312 (Case No. 14,738) (D . Va.,

1823); cf. Code of Ala., Tit. 30, § 2, and Code of M d., Art. 51,

§ 23, derogating the common law privilege in those states. For

the origins of the privilege, see Thompson & Merriam on

Juries, §§ 16, 17; Forsyth, Trial by Jury , 228-230; I Pollock &

Maitland, H istory of English Law , 473; Potter’s Historical In

troduction to English Law (4th ed.), 190. The privilege was

never deemed to be of constitutional dimensions, and its early

statutory abandonment would appear to reflect the view that

xenophobia is not a significant impediment to jury impartiality.

19

short, ordinarily presumes disinterested impartiality

on the part of jurors unless the contrary is specif

ically demonstrated in the individual case.

The line of so-called “ Negro exclusion” cases stem

ming from Strauder v. W est Virginia, 100 U.S. 303,

does not constitute a deviation from the rule that it is

only juror impartiality with which the Fifth and

Fourteenth Amendments are concerned. Rather,

those cases establish the subsidiary rule that where a

Negro litigant is forced to trial before a jury upon

which members of his race are, by reason of their

race, precluded from serving, a special circumstance

exists in which juror bias, rather than jury impar

tiality, must be presumed.10 In Strauder:, state law

limited jury service to white male adult citizens. The

Supreme Court found no difficulty with the limita

tions in regard to sex, majority and citizenship. Id.,

at 310. It took note, however, “ that prejudices often

exist against particular classes in the community,

which sway the judgment o f jurors, and which, there

fore, operate in some cases to deny to persons of those

classes the full enjoyment o f the protection which

others enjoy,” and found that “ [t]he framers of the

[Fourteenth] amendment must have known full well

the existence of such prejudice and its likelihood to

10 Although it is highly unusual to indulge a conclusive pre

sumption that jurors are biased against a litigant without some

showing as to their actual state of mind, nevertheless exclusion

cases are not the only ones in which such an approach is

adopted. A similar conclusive presumption of bias is indulged,

for example, when pervasive and intense prejudicial pretrial

publicity is established. Cf. Rideau v. Louisiana, 373 U .S . 723;

Shepherd v. Florida, 341 U .S . 50 (concurring opinion); D e

laney v. United States, 199 F . 2d 107 (C .A . 1, 1952).

20

continue against the manumitted slaves and their

race, and that knowledge was doubtless a motive that

led to the amendment.” Id., at 309. Then, observing

that “ [t]he very idea o f a jury is a body of men com

posed of the peers or equals of the person whose

rights it is selected or summoned to determine; that

is, of his neighbors, fellows, associates, persons having

the same legal status in society as that wdiich he holds”

(id., at 308), it held (ibid.) :

The very fact that colored people are singled

out and expressly denied by a statute all right

to participate in the administration of the law,

as jurors, because of their color, though they

are citizens, and may be in other respects fully

qualified, is practically a brand upon them,

affixed by the law, an assertion of their inferi

ority, and a stimulant to that race prejudice

which is an impediment to securing to in

dividuals of the race that equal justice which

the law aims to secure to all others. [Emphasis

added.]

In sum, the Court held in Strauder that the trial

o f a Negro defendant by a jury upon which members

o f his race are precluded by law from serving de

prives him of his constitutional right to “ an impar

tial jury trial.” Ex parte Virginia, 100 U.S. 339,

345. This holding can be seen to have been bottomed

upon two essential factors: (1) recognition of what

a later Court referred to as “ the long history of un

happy relations between the two races” (Fay v. New

York, 332 U.S. 261, 282), from which bias on the part

o f white jurors against Negro litigants is likely to

21

result,11 and (2) legislation which precluded jury

service by Negroes, thereby placing an official impri

matur of ratification and approval upon such bias.12

In Neal v. Delaware, 103 17.S. 370, the Court ex

panded the rule, making it applicable where the ex

clusion results from administrative action rather than

from legislation. See also Garter v. Texas, 177 U.S.

442, 447. The bases for the rule, however, remained

the same. Administrative exclusion, as much as leg

islative exclusion, was held to prejudice “ the fairness'

and integrity of the whole proceeding against the

11 A s noted in F ay, 332 U .S . at 283, this is not to imply that

it is only Negro exclusion which the Fifth and Fourteenth

Amendments forbid. The ambit of the amendments reaches

“to any identifiable group in the community which may be the

subject of prejudice.” Swain v. Alabama, 380 U .S . 202, 205,

citing Hernandez v. Texas, 347 U .S . 475. Nevertheless, uncon

stitutional discrimination has been found in only three cases

which did not involve Negroes: Hernandez, where the record

showed that the status in the community of Mexican-Americans

was equivalent to that of Negroes; United States ex rel. Leguil-

lou v. Davis, 115 F . Supp. 392 (D .Y .I ., 1953), where the court ex

pressly found that community prejudice existed against the

Puerto Rican minority in St. Croix (see 115 F . Supp. at 398);

and International Longshoremen’s cfi Ware. Union v. Ackerman,

82 F. Supp. 65 (D . Haw., 1948), where Filipinos were excluded

from grand jury service because “ [w]e just have a lot of other

men a lot better” and the grand jury list was disproportionately

stocked with “haoles” (persons of mainland American or north

ern European descent) “so that they might have an oppor

tunity to run the country” (see 82 F . Supp. at 119).

12 In Fay, the Court noted that “ a Negro who confronts a

jury on which no Negro is allowed to sit * * * might very

well say that a community which purposely discriminates

against all Negroes discriminates against him.” 332 U .S . at

293. In Brown v. Allen , 344 U .S . 443, 471, as well as in

Strauder, 100 U .S . at 309, it referred to Negro exclusion as

“jury packing.”

22

prisoner.” Neal V. Delaware, supra, 103 U.S. at 396.

Since the rule thus has its basis in a presumption

of juror bias, it follows that a litigant must meet two

conditions in order to offer it as a ground for over

turning unfavorable action against him by a grand or

petit jury. The first is that he must himself be of

the class against which discrimination was exercised

in the jury selection procedure. Fay v. New York,

supra, 332 U.S. at 287 yRawlins v. Georgia, 201 U.S.

638, 640; State v. Lea, 228 La. 724, 730, 84 So. 2d 169,

170-171 (S. Ct., 1955), certiorari denied, 350 U.S.

1007; Commonwealth v. Wright, 79 Ky. 22, 42 Am.

Rep. 203 (C.A. 1880). A litigant who is not of the

excluded class could hardly claim to be the victim of

bias resulting from the exclusion.13 14

Secondly, he must establish the existence of a pur

poseful and substantially effective effort to deprive

members of his class or group of any realistic oppor

tunity to serve as jurors. I f the jury which considers

his case contains a fair representation of members of

his class or group, he can hardly claim the existence

of a condition from which bias against him would be

inferrable. Compare Swain v. Alabama, 380 U.S. 202,

205;14 Akins v. Texas, 325 U.S. 358, 405-406; Thomas

13 Concededly, however, a litigant who, like appellant in

No. 21256, is involved in legal proceedings as the result of

activities wherein he associated himself with a minority group

can properly claim that community prejudice against that

group would be reflected in jury bias against himself.

14 Significantly, although there were three dissenters in Swain

(Warren, C.J., Goldberg and Douglas, JJ-), they did not dis

agree with the majority holding that neither the jury list or

venire as such, nor the grand jury which indicted petitioner

(upon which two Negroes sat), was composed in such a manner

23

v. Texas, 212 U.S. 278, 283. And, unless their omis*

sion is the result of a purposeful exclusion, it could

hardly be thought to constitute “ jury packing” (see

n. 12, supra, p. 21), or to carry the implication that

community prejudices have been given an official

sanction. As the Supreme Court stated in its most

recent pronouncement on this matter on March 8,

1965, it is only “ a State’s purposeful or deliberate

denial to Negroes on account of race of participation

as jurors in the administration of justice [which]

violates the Equal Protection Clause.” Swain v.

Alabama, supra, 380 U.S. at 204.

Thus, from the very beginning, the Supreme Court

has held that an intention to exclude must be estab

lished ( Thomas v. Texas, supra, 212 U.S. at 282-283;

Akins v. Texas, supra, 325 U.S. at 403-404; Fay v.

New York, supra, 332 U.S. at 284; Brown v. Allen,

344 U.S. 443, 471), and that the person attacking the

selection procedure has the burden of proving this

intent. Smith v. Mississippi, 162 U.S. 592, 600; Tar-

ranee v. Florida, 188 U.S. 519; Martin v. Texas, 200

U.S. 316; Fay v. New York, supra, 332 U.S. at 285.

While the eases in which the necessary proof has been

made have generally been marked by a minimal rep

resentation of the minority group on the jury list in

comparison to their proportion of the population,

such minimal representation does not of itself violate

the Constitution. Brown v. Allen, supra, 344 U.S. at

as to violate his constitutional rights. Rather, the basis for

their dissent was the historical use in the county in question

of peremptory challenges which resulted in no Negroes ever

having sat as petit jurors. See 380 U .S. 233 et seq.

24

471. As the Supreme Court has explained, “ [ ojur

directions that indictments be quashed when Negroes,

although numerous in the community, were excluded

from grand jury lists have been based on the theory

that their continual exclusion indicated discrimina

tion and not on the theory that racial groups must be

recognized.” 'Akins v. Texas, supra, 325 U.S. at 403.

In short, since proof o f a discriminatory purpose

brings into issue the subjective state of mind of jury

selection officials—a fact which rarely lends itself to

direct affirmative proof—a litigant is permitted to

establish a prima facie case by proof of the objec

tive results of the jury selection procedure at issue.

Norris v. Alabama, 294 U.S. 587, 591; Pierre v. Lou

isiana, 306 U.S. 354, 361; Smith v. Texas, 311 U.S.

128, 131; Hill v. Texas, 316 U.S. 400, 404; Patton v.

Mississippi, 332 U.S. 463, 466; Hernandez v. Texas,

347 U.S. 475, 480; Reece v. Georgia, 350 U.S. 85, 88;

Arnold v. North Carolina, 376 U.S. 773, 774.

The dispositive question, moreover, is whether the

facts indicate a purposeful exclusion from actual jury

service, and not merely a purposeful exclusion from

the lists from which jurors are chosen. Avery v.

Georgia, 345 U.S. 559. Hence, the necessary prima

facie inference is raised when a showing of “ the selec

tion on the jury list of a relatively few Negroes who

would probably be disqualified for actual jury serv

ice” is combined with a showing that none had ever

served as jurors. Reece v. Georgia, supraP Simi- 15

15 In Reece, only six of the 534 names on the grand jury list

were of Negroes. One was a non-resident of that county, two

were over 80 years of age (one of the two being partially deaf

25

larly, token participation of Negroes in actual grand

jury service can raise the inference of a discrimina

tory intent which is merely dissembled if Negro rep

resentation on the jury list is minimal ( United States

ex rel Seals v. Wiman, 304 F. 2d 53 (C.A. 5, 1962)),16

and particularly if the procedures for selecting jurors

appear to have been manipulated in such a way as to

minimize the translation of token Negro representa

tion on the list into actual jury service by Negroes.

Smith v. Texas, supra.17 And again, if Negro par

ticipation in grand jury service has been intention

ally limited to the exact proportion of members of the

race who are eligible for such service, and if such pro

portion is substantially lower than the proportion of

members o f the race to the total population, a dis

criminatory intent may be found. Cassell v. Texas,

and the other in poor health), and the other three were 62

years of age. The clerk and deputy clerk both testified that

they had never known a Negro to serve on a grand jury in

the county.

16 There had been only three Negroes among the 504 grand

jurors who had served on 28 grand juries in a nine-year period.

304 F . 2d at 61. Negroes comprised 31.7% of the population

but less than 2% of the persons on the jury rolls. Id. at 59.

17 Only three individual Negroes had served on five of the

thirty-two grand juries which had been impaneled over a

seven-year period. There were 18 Negroes among the 512 per

sons summoned for grand jury duty during this time, but 13

of them were placed at the bottom of the list where they stood

small likelihood of being reached for actual service, and only

one was listed where he had to be reached. Negroes comprised

20% of the population and 10% of the poll tax payers. 311

U .S. at 129.

26

339 U.S. 282, 286-287 (plurality opinion), 295 (con

curring opinion).18

The inference raised by such evidence, however, is

only prima facie and not conclusive. While mere

general disclaimers are not sufficient to rebut it (Nor

ris v. Alabama, supra, 294 U.S. at 598; Hernandez

v. Texas, supra, 347 U.S. at 481-482 ; Reece v. Georgia,

supra, 350 U.S. at 88),19 compelling rebuttal can be

18 Such grudging acceptance of Negroes as eligible for jury

duty can be said to have the same effect of singling them out

as a class apart (see Strauder v. W est Virginia, supra, 100

U .S. at 308) as would an outright exclusion. But quaere if

a Negro indicted by one of the grand juries upon which a

Negro had served could claim that, however much the over

all procedure was tainted by a discriminatory purpose, he was

affected by it. In Wiman, Smith and Cassell, the indictments

at issue were returned by all-white grand juries.

19 Similarly, jury selection officials cannot excuse a total

omission of Negroes from jury service or the mere token par

ticipation of members of that race in the jury process upon

the ground that they lack acquaintanceship with qualified Ne

groes. Rather, they are under a duty actively to seek out

Negroes who qualify. Smith v. Texas, supra, 311 U .S . at 132;

Hill v. Texas, supra, 316 U .S . at 404; Cassell v. Texas, supra,

339 U .S . at 290 (plurality opinion). There would appear to

be two grounds for this rule. First, it would offer too facile

kn alibi for purposeful discrimination if it could be dissembled

by the virtually irrebuttable contention of lack of acquaintance

ship among Negroes. A s the Court said in Smith, the Con

stitution forbids discrimination, “ whether accomplished in

geniously or ingenuously.” 311 U .S . at 132. Secondly, the

very community patterns which generate prejudice would be

responsible for the lack of acquaintanceship, and hence an omis

sion on that basis would be as much a stimulant to juror

prejudice as would a purposeful exclusion. Compare Strauder

v. W est Virginia, supra, 100 U .S . at 308. But if officials make

bona fide efforts to obtain the names of Negroes who qualify

as jurors, and if their efforts eventuate into actual participa

tion by Negroes as jurors on a regular basis, then they would

27

provided by a showing that Negroes have regularly

participated as grand jurors and have appeared on

the panels from which petit jurors are chosen (see

Swain v. Alabama, supra, 380 U.S. at 205; Akins v.

Texas, supra, 325 U.S. at 405-406; Thomas V. Texas,

supra, 212 U.S. at 283), or by a showing that the dis

proportion on the jury list, however gross, resulted

from factors other than race. Brown v. Allen, supra,

344 U.S. at 481.20 There is no constitutional require

ment that jury lists reflect the proportional strength

of the various elements of the population (Fay v.

New York, supra, 332 U.S. at 291; Cassell v. Texas,

supra, 339 U.S. at 286; Brown v. Allen, supra, 344

U.S. at 471; Hoyt v. Florida, 368 U.S. 57, 69; Swain

v. Alabama, supra, 380 U.S. at 208), and hence “ [t]he

mere fact of inequality in the number selected does

not in itself show discrimination.” Akins v. Texas,

supra, 325 U.S. at 403. In short, if there is Negro

representation on the jury list, even though dispro

portionately low, and there is actual jury service by

Negroes at more than a mere token level, then there

appear to meet the requirements of the Smith-Hill-Cassell

rule, even though the proportion of Negroes on the jury list

is small and might have been larger had the efforts been more

vigorous. A s the Supreme Court stated the rule in Hill,

“ [discrimination can arise from the action of commission

ers * * * w]-10 neither know nor seek to learn whether there are

in fact any qualified to serve” (emphasis added). 316 U .S.

at 404.

20 In Brown , Negroes comprised only 7% o f those on the

jury list in a county where they comprised 38% of the eligible

taxpayers, but the discrimination which caused this was eco

nomic rather than racial and hence the court found no consti

tutional violation.

28

is no violation of constitutional standards. See Swain

v. Alabama, supra, 380 U.S. at 209.

B. The statutory ground

A litigant’s statutory rights in regard to jury se

lection arise from, different considerations than do his

constitutional rights. The “ statutory scheme” of 28

U.S.C. 1861 et seq. is not limited in contemplation to

juror impartiality, but rather is designed to provide

the jury system itself with a “ broad base,” Ballard

v. United States, 329 U.S. 187, 195, so that the jury

will be “ drawn from a cross-section of the commu

nity,” Thiel v. Southern Pacific Go., 328 U.S. 217, 220,

and be “ truly representative of it.” Ballard v.

United States, supra, at 191. Hence the exclusion of

a cognizable class or group violates the statutory

scheme even though—like the women, in Ballard or

the daily wage earners in Thiel—the members of such

class or group are not the subjects of community

prejudice, since their omission deprives the jury of

“ a flavor, a distinct quality.” Ballard v. United

States, supra, at 194. And since, irrespective of any

possibility of juror bias, such exclusion “ does not

accord to the defendant the type of jury to which

the law entitles him,” the statutory right, unlike the

constitutional one, may be asserted by any litigant,

even though he is not a member of the excluded

class. Id., at 195; see also United, States v. Roemig,

52 F. Supp. 857, 862 (IsT.D. Ia., 1943). The gist of

a statutory complaint, unlike a constitutional one, thus

does not pertain to exclusions from the jury itself,

since “ complete representation [of all elements of so

ciety] would be impossible” on a single jury. Thiel

29

y. Southern Pacific Co., supra, at 220. Rather, the

complaint is directed at exclusions from the jury

list, which distort the ‘ Muck of the draw” and pre

clude the possibility that the jury (and particularly

the pptit jury after both sides have exercised their

challenges) will reflect the mesne sentiments and the

consensual views of the community.

But although the desideratum is thus that the jury

list be “ drawn from a cross-section of the commu

nity,” it does not follow that the list must reflect

the relative population strength of all elements

of the community. Proportional representation is

no more required by statute than it is by the Con

stitution. Chance v. United States, 322 F. 2d 201,

204-205 (C.A. 5, 1963), certiorari denied, 379 U.S.

823; United . States v. Flynn, 216 F. 2d 354 (C.A.

2, 1954), certiorari denied, 348 U.S. 494; Dow v.

Carnegie-Illinois Steel Corporation, 224 F. 2d 414,

428 (C.A. 3, 1955), certiorari denied, 350 U.S. 971;

United States v. Dennis, 183 F. 2d 201, 223 (C.A. 2,

1950), affirmed, 341 U.S. 494; United States v. Green

berg, 200 F. Supp. 382, 392 (S.D.U.Y., 1961) ; United

States v. Romano, 191 F. Supp. 772, 774—775 (D.

Conn., 1961); United States v. Brandt, 139 F. Supp.

349, 354-355 (K D . Ohio, 1955); United States v.

Fujimoto, 102 F. Supp. 890, 894 (I). Haw., 1952) ;

United States v. Foster, 83 F. Supp. 197, 208

(S.D.H.Y., 1949). In Thiel, the Supreme Court ex

plained that the requirement that juries be “ drawn

from a cross-section of the community” means only

“ that prospective jurors shall be selected by court

officials without systematic and intentional exclusion

30

o f any [economic, social, religious, racial, political

and geographical] groups,” 328 tT.S. at 220, adding

that “ a blanket exclusion o f all daily wage earn

ers * * * must be counted among those tendencies

which undermine and weaken the institution o f jury

trial.” Id. at 224 [Emphasis added]. In Ballard,

it held that it was “ the purposeful and systematic

exclusion of women from the panel” which constituted

“ a departure from the scheme of jury selection which

Congress adopted,” 329 TT.S. at 193, and further

stated that “ [t]he evil lies in the admitted exclusion

o f an eligible class or group in the community in

disregard of the prescribed standards o f jury selec

tion.’ ’ Id-, at 195. [Emphasis added.] In short,

what the Court held Congress to have forbidden is

the same purposeful exclusion which the Constitu

tion forbids. The only variation is that Congress has

forbidden all purposeful exclusions (other than those

sanctioned by 28 TT.S.C. 1861 and 1863), and not

merely those which stimulate juror bias against par

ticular litigants.21

Ballard and Thiel have been generally construed by

lower courts as forbidding only purposeful and total

exclusion, and not as placing any affirmative require

ments upon jury officials. See Frazer v. United

States, 335 TT.S. 497, 504; United States v. Dennis,

supra, 183 E. 2d at 219, 223; Dow v. Carnegie-Illinois

21 The Court has also held that the statutory scheme places

one further inhibition upon jury officials: they cannot limit

their selections from a given class to a specialized subgroup

with particular interests within that class, as, e.g., choosing only

those women who are members of the League of Women

Voters. See Glasser v. United States, 315 U .S . 60, 83-87.

31

Steel Corporation, supra, 224 F. 2d at 423; United

States v. Clancy, 276 F. 2d 617, 632 (C.A. 7, 1960),

reversed on other grounds, 365 U.S. 312; Young v.

United States, 212 F. 2d 236, 238 (C.A.D.C., 1954),

certiorari denied, 347 U.S. 1015; United States v.

Brandt, supra, 139 F. Supp. at 354; United States

v. Greenberg, supra, 200 F. Supp. at 393. As was

concluded in United States v. Local 36 of Interna

tional Fishermen, 70 F. Supp. 782, 790 (SJD. Cal.,

1947), affirmed, 177 F. 2d 320 (C.A. 9, 1949), cer

tiorari denied, 339 U.S. 947, after a detailed analysis,

Thiel holds only “ that for a jury panel to be invalid

because o f discrimination there must be clear evidence

of an intent on the part of the jury commissioner or

the clerk, or both, to prevent or exclude, or to devise

and use a system or method of selection which is cal

culated and intended by them, or either of them, to

result in the prevention or exclusion of, any person

or group of persons from being called for jury service

on account Of, and solely because o f” their member

ship in a cognizable class. [Emphasis added.]22

22 In D ow v. Camegie-IUinois Steel Corporation, supra, the

Third Circuit took a broader view of Thiel and Ballard, and

held that they forbade federal jury officials “ to exclude any

cognizable groups from jury lists through neglect as well as

through intentional conduct.” 224 F . 2d at 424. No other

court has given the two cases that broad an interpretation.

The Third Circuit, however, made it clear that it viewed only

total exclusion by neglect to contravene the statutory scheme.

It held that so long as “each official was aware o f this signifi

cant racial segment of our population [Negroes], and each,

in the proper exercise o f his discretion, devised his own method

to insure their representation”, their efforts were not unlawful

even if “more effective or vigorous methods of solicitation”

might have been devised. Id. at 425.

The amendment of 28 U.S.C. 1861 brought about

by the Civil Rights Act of 1957 has, as this Court

recognized in Chance v. United States, supra, 322 F.

2d at 205, placed federal jury officials “ under no

mandatory or positive commands,” but has left them

“ on the contrary, controlled by one negative require

ment: they may not discriminate, directly or indi

rectly.” Prior to the amendment, federal jurors had

to be competent to serve as state jurors. I f states

(as most Ahem did) required jurors to be. electors,

and if Negroes were generally excluded from the

franchise in certain states, then their disability as

state jurors made them ineligible as federal jurors.

The purpose of the amendment was to qualify

Negroes as federal jurors despite their discriminatory

disqualification under state practices. . See 103 Cong.

Ree. 13154, 13157, 13277, 13249, 13325-13326. There

is nothing in the amendment which requires federal

officials to take positive steps of any particular vigor

to obtain Negro jurors, a fact which caused Senator

Morse to object that “ [t]he provision is not self-en

forcing,” id. at 13317, and Senator Douglas to object

that “ [njothing in the amendment compels an affirma

tive change in the practice of selecting juries.” Id.

at 13250. [Emphasis added.] See also remarks of

Senator Carroll, id. at 13293. Senator Clark went

further and proposed that the amendment “ should

require the nondiscriminatory selection of jurors in

proportion to the population within the district,” id.

at 13290, adding that “ unless strong mandatory lan

guage is written into the proposed jury-trial amend

ment, preferably in connection with section 1864, we

32

shall have done nothing more than remove a qualifica-

tion.” Id. at 13290-13291. [Emphasis added.]

Since the views of Senators Morse, Douglas, Carroll

and Clark did not prevail, it follows that the amend

ment has left the “ statutory scheme” where Thiel

and Ballard proclaimed it to be: with the single com

mand that there must be no purposeful exclusions

based upon race or any other similar status.

II

The procedures for compiling the ju ry list below met constitu

tional and statutory standards

Applying the principles enunciated in the foregoing

cases, it can be seen that the procedures used to com

pile the jury list in the Macon Division of the Middle

District of G-eorgia did not violate either constitu

tional or statutory standards. That is to say, the

record, taken as a whole, does not support the con

clusion that there existed a purposeful discrimination

against Negroes because of race or that the procedures

were inherently calculated to discriminate on the basis

of race. A prima facie inference of purposeful dis-

eriminaiioiriimglLt, peBBaps, be raised on the basis

o f.proportions (i.e., Negroes comprising 35% of the

adult popTrlatien^-in^r^fviSion, 7.3% of those who

returned questionnaires, and 5.9% of those on the

jury list) were such proportions the only facts which

the record disclosed. But the inference loses its com-

H n ji — ....— — ....... -nin Vl

pelling force when measured against the fact that,

unlike such cases as Norris v. Alabama, 294 U.S. 587,

the record here shows that Negroes have regularly

served as both grand and petit jurors within the divi-

33

34

sic®, and that five Negroes served on the indicting

grand jury in these cases. Where Negroes actually

serve regularly as jurors, the record can hardly be

said to establish a purpose to preclude them from such

service or to evince a procedure which has such pre

clusion as its natural and inherent result. Compare

Swain v. Alabama, supra, 380 U.S. at 205; Akins v.

Texas, supra, 325 U.S. at 405-406; Thomas v. Texas,

212 U.S. at 283. In such circumstances, whatever else

may be said about the disproportion on the jury list,

it falls short of establishing either constitutional or

statutory fallibility in the procedures by which the

list was compiled.

In the face of the actual participation of Negroes

as jurors which the record here shows, a claim of

constitutional or statutory infirmity would have to

rest upon the nature of the procedure used (i.e., the

“ key man” or suggestor system), or upon the stand

ards for jury service which the clerk and commis

sioner applied in making their selections. The sug

gestor system, however, has been specifically ap

proved for use in federal courts. Scales v. United

States, 367 U.S. 203, 259; Padgett v. Buxton-Smith

Mercantile Go., 283 F. 2d 21, 41—46 (C.A. 10), cer

tiorari denied, 365 U.S. 882; Windom v. United

States, 260 F. 2d 384 (C.A. 10); Walker v. United

States, 93 F. 2d 383 (C.A. 8, 1937), certiorari denied,

303 U.S. 644. Nor was its application in these cases

improper or unlawful. In turning for suggestions to

persons whom they knewT and trusted, the clerk and

commissioner followed the procedure twice recom

mended (in 1942 and 1960) by the Judicial Confer

ence Committee on the Operation o f the Jury System:

vis., “ that the ‘key-men’ asked to suggest names

should be those citizens of the district who are most

likely to be impartial and who are known to have a

high sense of civil responsibility.” The Jury System

in the Federal Courts, 26 F.R.D. 409, 428-429. See

also n. 23, pp. 40-41, infra.

In seeking jurors who were not merely literate, but

rather who had the education and intelligence to be

able to understand and decide cases presented in fed

eral courts, the clerk and commissioner also followed

the recommendations of the Judicial Conference Com

mittee that “ jurors should possess as high a degree

of intelligence, morality, integrity, and common sense,

as can be found by the persons charged with the duty

of making the selection. The Jury System in the

Federal Courts, supra, 26 F.R.D. at 425; see also 418,

419, 421. As the 1960 report stated, id. at 419:

The jury holds in its collective hands the life,

liberty and welfare of individual defendants in

criminal cases and the interests of litigants in

civil eases. The importance of improving the

calibre of these judges of the facts is therefore

self evident.

and:

In order to get better jurors, the Committee

recommends greater care in the compilation of

the list of jurors whose names go into the jury

wheel or box from which trial jurors are

chosen.

Procedures calculated to obtain high calibre and

intelligent jurors have never been deemed repugnant

to either the Constitution or to federal jury laws.

36

Thus, the Supreme Court, noting that “ [a] fair ap

plication of literacy, intelligence and other tests

would hardly act with proportional equality on all

levels of life,” has held that “ [t]he state’s right to

apply these tests is not open to doubt even though

they disqualify, especially in the conditions that pre

vail in New York, a disproportionate number o f

manual workers.” Fay v. New York, supra, 332 U.S.

at 291. The Fay holding, moreover, has been specifi

cally applied to federal jury selection in accordance

with statutory standards ( United States v. Dennis,

supra, 183 F. 2d at 222) ; it was held to offer a valid

and adequate explanation for the disproportionately

low number of Negroes whose names appeared on

the federal jury lists there in question. Id. at 223.

And in United States v. Henderson, 298 F. 2d 522, 525

(1962), certiorari denied, 369 U.S. 878, the Seventh Cir

cuit, after noting that the 1957 amendment of 28 U.S.C.

1861 was “ designed to attain objectives not inconsistent

with recognition that a reasonable level of intelligence

is appropriate, if not a requisite, to the rendition of

efficient service as a juror,” held that it was proper for

jury officials to consider, in making their selections for

the jury box, whether prospective jurors had completed

eight years of formal education, because:

Recognition that the statute envisions “ effi

cient” service requires rejection of a conclusion

that an intelligence level equated with mere

literacy was intended to be imposed as a maxi

mum standard to be employed by the clerk and the

commissioner in the selection of persons pursuant

to § 1864 whose names are to be placed in the

box from which jurors are drawn.

37

The only limitation upon the discretion of jury

officials in adopting procedures calculated to insure

efficient service is that “ [recognition must be given

to the fact that those eligible for jury service are to

be found in every stratum of society,” and that

“ [j]ury competence is an individual rather than a

group or class matter.” Thiel v. Southern Pacific

Co., supra, 328 U.S. at 220. Standards for jury selec

tion must not be “ irrational,” United, States v. Hen

derson, supra, 298 V. 2d at 525, and must be applied

in an even-handed fashion. Compare Fay v. New

York, supra, 332 U.S. at 291. The record here shows

that the clerk and jury commissioner were guided by

the principle enunciated in Thiel, and set about to ob

tain intelligent and efficient jurors on an individual

basis, without regard to societal status. Their stand

ards, adopted after consultation with Judge Bootle

and based upon the advice set forth in the manual for

jury selection published by the Administrative Office

of the United States Courts, can hardly be deemed

“ irrational.” There is no suggestion in the record

that they applied the standards other than even-

liandedly, exacting the same qualifications for white

persons as they did for Kegroes. There is thus

nothing about the standards which they adopted which

is either inherently discriminatory, or which evinces

a purpose to discriminate, on the basis o f race.

It is our submission, therefore, that, on the record

as it was made in the district court, the court was

correct in its conclusion that the appellants had not

shown that the jury box was defective from either

the constitutional standpoint or the standpoint of the

38

federal statutory scheme as it was administered by the

clerk and jury commissioner under the supervision of

the district court in compiling a list of jurors avail

able to meet the needs of the court in the adminis

tration of justice in the Macon Division. In this

view, neither the indictments returned by the grand

jury nor the verdicts of the petit juries, all the mem

bers o f which were drawn by lot from the jury box,

are vulnerable on the grounds asserted by the

appellants.

I ll

In the particular circumstances of this case, the addition of

only four new Negro names in the compilation of the 1959

jury list and the failure during the period involved to make

further affirmative efforts to add additional Negro names to