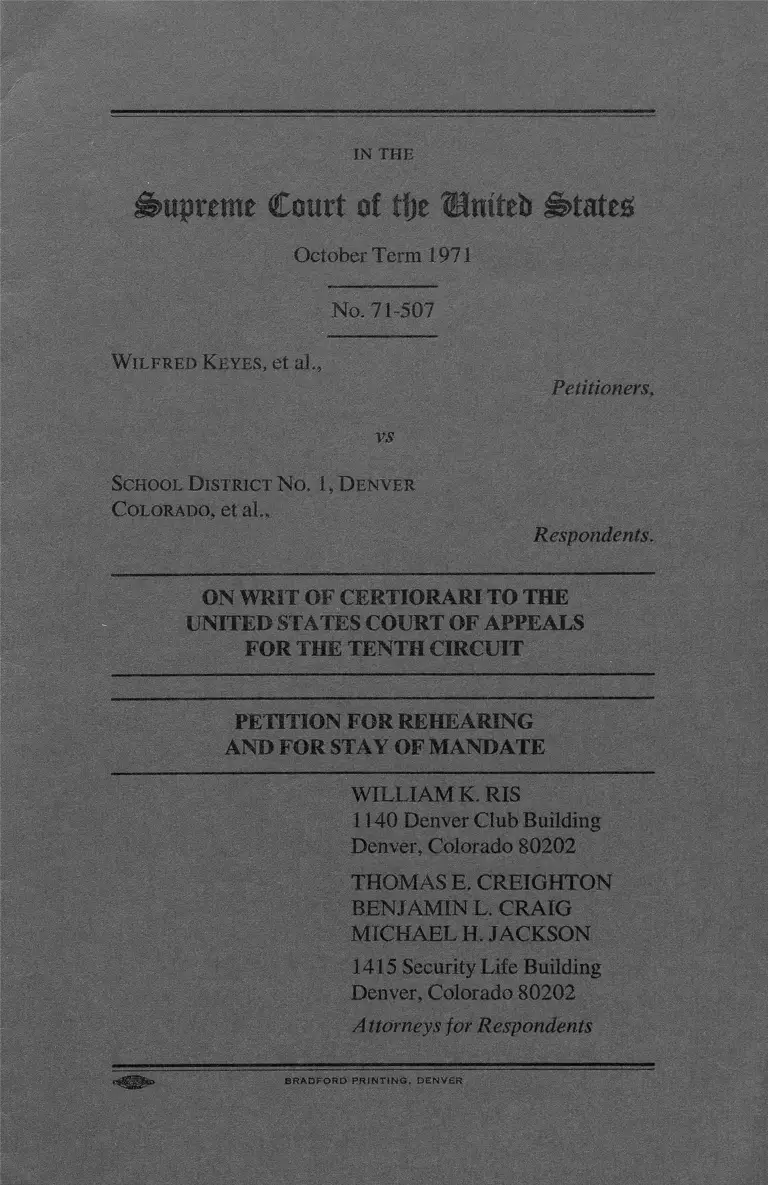

Keyes v. School District No. 1 Denver, CO. Petition for Rehearing and for Stay of Mandate

Public Court Documents

October 4, 1971

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Keyes v. School District No. 1 Denver, CO. Petition for Rehearing and for Stay of Mandate, 1971. 96a341f9-b99a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/7b5c1884-dc60-4cfa-9d83-5fb3f572dcf9/keyes-v-school-district-no-1-denver-co-petition-for-rehearing-and-for-stay-of-mandate. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

IN THE

Supreme Court of tf?e W n itzb H>tate£

October Term 1971

No. 71-507

Wilfred Keyes, et al.,

Petitioners,

vs

School D istrict No. 1. Denver

Colorado, et al..

Respondents.

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE TENTH CIRCUIT

PETITION FOR REHEARING

AND FOR STAY OF MANDATE

WILLIAM K. RIS

1140 Denver Club Building

Denver, Colorado 80202

THOMAS E. CREIGHTON

BENJAMIN L. CRAIG

MICHAEL H. JACKSON

1415 Security Life Building

Denver, Colorado 80202

A ttorneys for Respondents

B R A D F O R D P R I N T I N G , D E N V E R

IN THE

Supreme Court of tfje ®mteb States

October T erm 1971

No. 71-507

Wilfred Keyes, et al.,

vs

School D istrict No. 1, D enver

Colorado, et al.,

Petitioners,

Respondents.

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE TENTH CIRCUIT

PETITION FOR REHEARING

AND FOR STAY OF MANDATE

Respondents respectfully petition the Court for a rehear

ing on one of the two questions decided by the Court in its

Opinion of June 21, 1973, namely, whether the courts

below applied the correct legal standard in addressing peti

tioners’ claims of state-imposed segregation in the core city

schools; and as to that question, respondents seek rehearing

only as to that part of the question relating to the shifting of

the burden of proof discussed in Part III of the Opinion.

— 2

Respondents also request that the mandate be stayed

until disposition of this petition.

Grounds for the Petition

1. Summary

The Opinion leaves doubt as to whether the school au

thorities have the burden of proving lack of segregative in

tent as to their actions prior to the intentionally segregative

actions, first occurring in 1960, proven by the petitioners.

All precedent and authority hold that prior intentional

acts are probative on the question of the intent associated

with later acts. Yet the Opinion does not explicitly confine

the effect of the burden-shifting principle to actions at or

after the time of the proven intentional segregative acts.

Whether the respondents’ burden of proof extends to

school district actions prior to 1960, when the first segrega

tive act, the building of Barrett School, was shown, will

make a substantial difference, upon remand, in the scope of

the proceedings, including the time required for trial prepa

ration, the duration of the trial, and the expense to the

school district. It will make the difference of whether the

school district must carry the burden of proof respecting the

intent of all of its actions for only the 14-year period extend

ing back to 1959, or for a much longer period of at least

twice that duration to the early 1940’s when ethnic concen

trations first began to appear in the Denver schools.

2. The Authorities and Precedents

All of the treatises and cases cited by the Court refer to

prior or concurrent conduct. The touchstone for the bur

den-shifting rule is the

“. . . well-settled evidentiary principle that ‘the

prior doing of other similar acts, whether clearly

3

part of a scheme or not, is useful as reducing the

possibility that the act in question was done with

innocent intent.’ II Wigmore, Evidence 200 (3d

ed. 1940).” (emphasis added) (Opinion, p. 17)

The example of the application of the principle from the

criminal context (Nye & Nissen v. United States, 336 U.S.

613 [1949]) involved presentation of false invoices during

the same period of time as the acts charged (332 U.S. at

618).

The school desegregation cases cited by the Court —

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education, 402

U.S. 1 (1971), and the teacher discharge cases — all in

volved a “history of segregation,” which the Court expressly

defines:

“Indeed, to say that a system has a ‘history of

segregation’ is merely to say that a pattern of in

tentional segregation has been established in the

past.” (emphasis added) (Opinion, p. 20)

The Court then restates its holding, in the light of these

authorities, as follows:

“Thus, be it a statutory dual system or an aleg-

edly unitary system where a meaningful portion

of the system is found to be intentionally segre

gated, the existence of subsequent or other segre

gated schooling within the same system justifies a

rule imposing on the school authorities the bur

den of proving that this segregated schooling is

not also the result of intentionally segregative

acts.” (emphasis added) (Opinion, p. 20)

The use of the words “subsequent or other,” especially in

light of the authorities cited, is consistent with the applicabil

ity of the shift of burden to subsequent or contemporaneous

4 —

situations, excluding prior segregated schooling from the

operation of the burden-shifting rule.

3. The Application of the Rule by the Courts Below

The courts below clearly recognized that prior segrega

tive acts have probative value on the issue of segregative

intent with respect to later acts.

This Court commenced its discussion of the burden-shift

ing principle with the observation that the District Court

had considered “past discriminatory acts . . . in assessing the

causes of current segregation . . . ” (emphasis added)

(Opinion, n. 14, p. 16). The District Court had limited its

consideration of the Park Hill actions in 1960 (building

Barrett), 1962 and 1964 (boundary changes at Stedman

and Hallett), and 1965 (mobile units at Stedman and Hal-

let), to the assessment of segregative purpose of the later

1969 acts (the repeal of the racial balancing resolutions).

Thus, the limitation of the District Court’s comment is

chronological, not geographical.

When the Court of Appeals agreed with the District

Court that the “petitioners had failed to prove” intentional

discriminatory acts causing present racial imbalance in the

core city schools, the Court of Appeals clearly limited the

imposition of the burden on petitioners to the time period

prior to 1960 when there were no prior segregative acts

shown:

“Where, as here, the system is not a dual one, and

where no type of state imposed segregation has

previously been established, the burden is on

plaintiff to prove by a preponderance of evidence

that the racial imbalance exists and that it was

caused by intentional state action, (emphasis

added) (445 F. 2d at 1006, A.P. 148a)

5

4. The Structure of the Case and the Order of Events

The segregative acts in Park Hill occurred in the 1960’s,

as the Opinion notes (p. 8); but, with one exception, the

Opinion nowhere identifies the time period in which the acts

with respect to the core city schools took place. The excep

tion is the reference to actions in the core city area antedat

ing the 1954 decision in Brown, where the focus of the

Opinion was on the attenuation of causal effect, as distinct

from intent. (Opinion, p. 20)

Respondents believe that it is probable that the Court, in

formulating the burden-shifting principle, misapprehended

the order of events as between the Park Hill schools and the

core city schools. This could easily have happened because

the Park Hill evidence was presented at the first hearing in

support of the first cause of action, and the trial court’s

opinions thereon were announced and reported first. The

District Court discussed the Park Hill evidence in the first

part of its opinion on the merits, and the Court of Appeals

did likewise in its opinion. Petitioners, in their brief, consis

tently reversed the chronology in discussing the evidence

and other aspects of the case, and discussed the Park Hill

events first before turning to the earlier events in the core

city area.

Actually, almost all of the actions of the school district

with respect to the core city area took place in the 1950’s,

under wholly different school boards, ten years before the

Park Hill events.

5. The Secondary Issue of Causal Attenuation

Nor does the discussion of causal attenuation (Opinion,

pp. 20, 21) appear to carry the application of the burden-

shifting principle back to actions taken prior to the period

of proven intentional segregation. This is because the show

ing of causal attenuation comes into play as to those acts

6 —

which cannot be shown to lack segregative intent. (Opinion,

p. 21) And such intent, by all authorities cited, can be in

ferred only on the basis of prior or contemporaneous

segregative acts, and not on the basis of subsequent in

tentional acts many years later.

Conclusion

We are assured by Biblical authority that the iniquities

of the fathers will not be visited on the children. Con

versely, the Court should not visit the “sins” of one genera

tion of school board members and administrators upon the

men and women serving in such capacities in an earlier

generation.

WHEREFORE, respondents respectfully pray that re

hearing be granted on the question of whether proven dis

criminatory acts may be deemed probative on the issue of

the segregative purpose of earlier acts, thus shifting the bur

den of proof as to such earlier acts. A resolution of this

question is of substantial importance in determining the

scope of the future conduct of this litigation.

This petition is filed after the Court has adjourned; re

spondents, accordingly, also respectfuly request that the

mandate of the Court be stayed until disposition of this

petition, in the interests of orderly further proceedings

below.

Respectfully submitted,

WILLIAM K. RIS

1140 Denver Club Building

Denver, Colorado 80202

THOMAS E. CREIGHTON

BENJAMIN L. CRAIG

MICHAEL H. JACKSON

1415 Security Life Building

Denver, Colorado 80202

Attorneys for Respondents

— 7 —

CERTIFICATE

The undersigned, counsel for respondents, certify that the

foregoing Petition for Rehearing is presented in good faith

and not for the purpose of delay, and that the petition is

restricted to substantial grounds now available to respond

ents in view of the Opinion herein.

Attorneys for Respondents