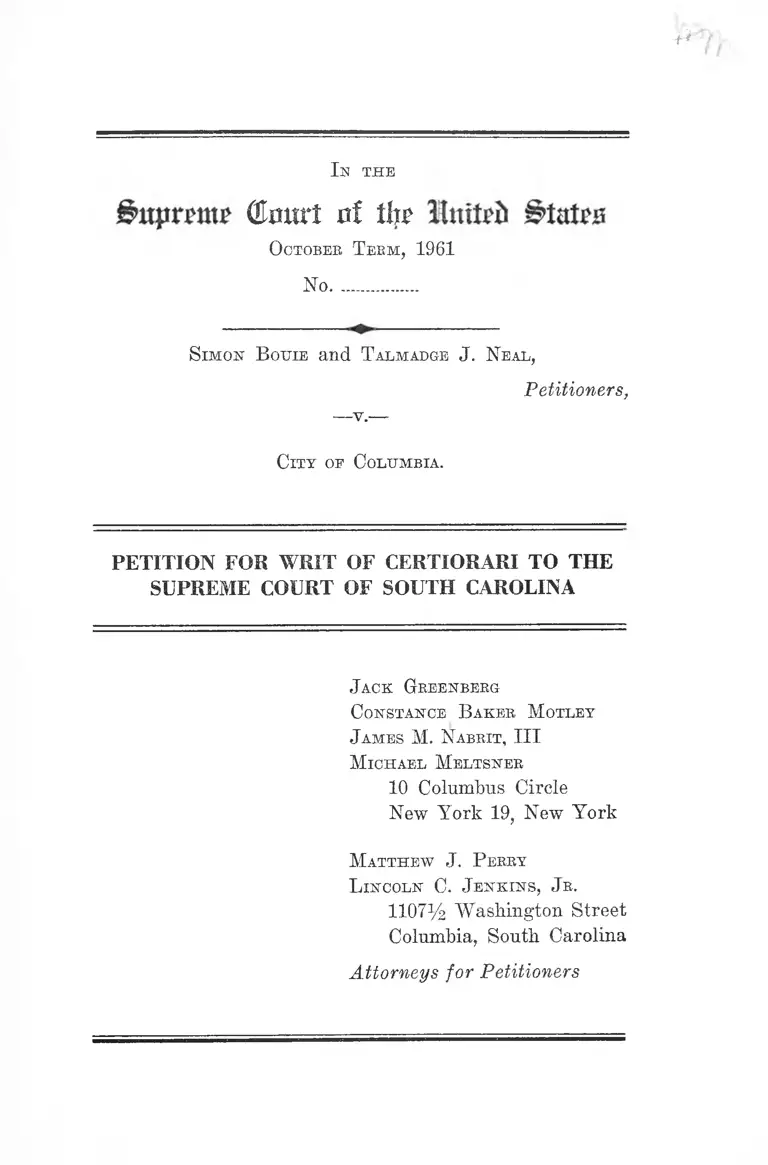

Bouie v. City of Columbia Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court of South Carolina

Public Court Documents

March 7, 1962

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Bouie v. City of Columbia Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court of South Carolina, 1962. ef0e1e35-ca9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/7b65a3d8-d73e-4d11-af30-f515e023fcd3/bouie-v-city-of-columbia-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari-to-the-supreme-court-of-south-carolina. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

p

I n the

(&mvt at tin

Octobeb T eem, 1961

No................

S imon B ouie and T almadge J. Neal,

Petitioners,

—v.—

City of Columbia.

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

SUPREME COURT OF SOUTH CAROLINA

J ack Geeenbeeg

Constance B aker Motley

J ames M. Nabrit, I I I

Michael Meltsner

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

Matthew J . P erry

L incoln C. J enkins, J r,

1107% Washington Street

Columbia, South Carolina

Attorneys for Petitioners

I N D E X

PAGE

Citations to Opinions Below ......................................... 1

Jurisdiction .................................................................... 2

Questions Presented ...................................................... 2

Statutory and Constitutional Provisions Involved........ 3

Statement ........................................................................ 3

How the Federal Questions Were Raised and Decided 6

Reasons for Granting the W rit..................................... 10

I. The Decision Below Conflicts With Prior De

cisions of This Court Which Condemn the Use

of State Power to Enforce Racial Segregation 10

II. The Decision Below Conflicts With Decisions

of This Court Securing the Right of Freedom

of Expression Under the Fourteenth Amend

ment to the Constitution of the United States 16

Conclusion ...................................................................... 27

A p p e n d ix

Opinion of the Columbia Recorder’s Court.................. la

Opinion of the Richland County C ourt.......................... 3a

Opinion of the Supreme Court of South Carolina........ 10a

Denial of Rehearing by the Supreme Court of South

Carolina....................................................................... 14a

11

Table of Cases

PAGE

Abrams v. United States, 250 U. S. 616......................... 17

Boynton v. Virginia, 364 U. S. 454 ................................ 11

Breard v. Alexandria, 341 U. S. 622 ...... ...............—14,17

Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S. 6 0 ................................ 12

Burton v. Wilmington Parking Authority, 365 U. S.

715 ............................................................................... 13

Cantwell v. Connecticut, 310 U. S. 296 ........................... 26

Champlin Rev. Co. v. Corporation Com. of Oklahoma,

286 U. S. 210.............................................................. 26

Chaplinsky v. New Hampshire, 315 U. S. 568 .............. 25

City of Charleston v. Mitchell, —— S. C. ----- , 123

S. E. 2d 512 (Petition for Writ of Certiorari No. 846

filed 30 U. S. L. Week 3324) ................................... 10,11

City of Columbia v. B arr,----- S. C .------ , 123 S. E. 2d

521 (Petition for Writ of Certiorari No. 847 filed

30 U. S. L. Week 3324) ............................................ 10,11

City of Greenville v. Peterson, ----- S. C. ——, 122

S. E. 2d 826 (Petition for Writ of Certiorari No. 750

filed 30 U. S. L. Week 3274) ................................9,11, 21

Civil Rights Cases, 109 U. S. 3 ................................... 11,15

District of Columbia v. John R. Thompson Co., 346

IJ. S. 100...................................................................... 13

Freeman v. Retail Clerks Union, Washington Superior

Court, 45 Lab. Rel. Ref. Man. 2334 (1959) ................ 18

Garner v. Louisiana, 368 U. S. 157 ...... 13-14,15,16,18, 26

Goldblatt v. Town of Hempstead, 30 U. S. L. Week

4343 12

Ill

PAGE

Herndon v. Lowry, 301 U. S. 242 ........................... .23, 24, 25

Hudson County Water Co. v. McCarter, 209 U. S. 349 16

Lanzetta v. New Jersey, 306 U. S. 451 ........................ 22, 24

Mapp v. Ohio, 367 U. 8. 643 ..................................... . 14

Marsh v. Alabama, 326 U. S. 501...................................12,18

Martin v. Struthers, 319 U. S. 141 ................................ 17

McBoyle v. United States, 283 U. S. 25 .......................23, 25

Monroe v. Pape, 365 U. S. 167 ..................................... 11

Munn v. Illinois, 94 U. S. 113......................................... 12

N. A. A. C. P. v. Alabama, 357 U. S. 449 ....................... 17

Napue v. Illinois, 360 H. S. 264 ................................... 11

N. L. E. B. v. American Pearl Button Co., 149 F. 2d

258 (8th Cir. 1945) .................................................. 18

N. L. E. B. v. Fansteel Metal Corp., 306 U. S. 240 ........ 18

People v. Barisi, 193 Misc. 934, 83 N. Y. S. 2d 277 (1948) 18

People v. King, 110 N. Y. 419, 18 N. E. 245 (1888),

Annotation 49 A. L. E. 505 ..................................... 13

Pickett v. Kuchan, 323 111. 138, 153 N. E. 667, 49

A. L. E. 449 (1926) ..................................... .............. 13

Pierce v. United States, 314 U. S. 206 ........................ 22, 24

Poe v. Ullman, 367 U. S. 497 ......................................... 14

Eailway Mail Assn. v. Corsi, 326 U. S. 88..................... 13

Bepublic Aviation Corp. v. N. L. E. B., 324 U. S. 793....12,18

Schenck v. United States, 249 U. S. 4 7 ........................ 19

Screws v. United States, 325 U. S. 91............................ 11

Shelly v. Ivraemer, 334 U. S. 1 ................. ................... 11,12

Shramek v. Walker, 149 S. E. 331.................................. 8

State v. Gray, 76 S. C. 83 .............................................. 20

IV

PAGE

State v. Green, 35 S. C. 266 ................................... 20

State v. Hallback, 40 S. C. 298 ....................................... 20

State of Maryland v. Williams, Baltimore City Court,

44 Lab. Bel. Bef. Man. 2357 (1959) .......................... 18

State v. Mays, 24 S. C. 190........................................... 20

State v. Tenney, 58 S. C. 215......................................... 20

Stromberg v. California, 283 U. S. 359 ......................... 17

Thompson v. City of Louisville, 362 U. S. 199.............. 21

Thornhill v. Alabama, 310 U. S. 88 .........................14,17,18

United States v. Cardiff, 344 U. S. 174 .......................23, 24

United States v. L. Cohen Grocery Co., 255 U. S. 81....23, 24

United States v. Weitzel, 246 U. S. 533 ......................... 23

United States v. Willow Biver Power Co., 324 U. S.

499 ............................................................................... 12

United States v. Wiltberger, 18 U. S. (5 Wheat.) 76 .... 23

Western Turf Asso. v. Greenberg, 204 U. S. 359 .......... 13

West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnette,

319 U. S. 624 ......... ..................................................... 17

Winters v. New York, 333 U. S. 507 .......................... 25, 26

Statutes

Code of Laws of South Carolina, 1952, Section 15-909 .... 5, 7,

8

Code of Laws of South Carolina, 1952, Section 16-386 .... 3, 5,

6, 7, 8, 9

Code of Laws of South Carolina, 1960, Section 16-386 .... 21,

25

United States Code, Title 28, Section 1257(3) .............. 2

V

Other Authorities

PAGE

Ballentine, “Law Dictionary” (2d Ed. 1948) ................ 25

Black’s “Law Dictionary” (4th Ed. 1951) ..................... 25

Henkin, “Shelley v. Kraemer: Notes for a Revised

Opinion,” 110 U. of Penn. L. Rev. 473 ............... 12,13,14

Konvitz, “A Centnry of Civil Rights” .......................... 13

I n th e

Bnpnm$ (Emtrt of tip llnttefi

Octobee Term, 1961

No................

Simon B otjie and T almadge J. Neal,

Petitioners,

—v.—

City oe Columbia.

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

SUPREME COURT OF SOUTH CAROLINA

Petitioners pray that a writ of certiorari issue to review

the judgment of the Supreme Court of South Carolina,

entered in the above entitled case on February 13, 1962,

rehearing of which was denied on March 7, 1962.

Citation to Opinions Below

The opinion of the Supreme Court of South Carolina is

unreported as of yet and is set forth in the appendix hereto,

infra, pp. 10a-13a. The opinion of the Richland County

Court is unreported and is set forth in the appendix hereto,

infra, pp. 3a-9a. The opinion of the Recorder’s Court of

the City of Columbia is unreported and is set forth in the

appendix hereto, infra, pp. la-2a.

2

Jurisdiction

The Judgment of the Supreme Court of South Carolina

was entered February 13, 1962, infra, pp. 10a-13a. Petition

for Behearing was denied by the Supreme Court of South

Carolina on March 7, 1962, infra, p. 14a.

The jurisdiction of this Court is invoked pursuant to

Title 28, United States Code, Section 1257(3), petitioners

having asserted below and asserting here, deprivation of

rights, privileges and immunities secured by the Constitu

tion of the United States.

Questions Presented

1. Whether the due process and equal protection clauses

of the Fourteenth Amendment permit a state to use its

executive and judiciary to enforce racial discrimination

in conformity with a state custom of discrimination by

arresting and convicting petitioners of criminal trespass

on the premises of a business which has for profit opened

its property to the general public.

2. Whether petitioners’ conviction of trespass at the

restaurant of a variety store offends the due process clause

of the Fourteenth Amendment when petitioners were con

victed for engaging in a sit-in protest demonstration and

the criminal statute applied to convict petitioners gave no

fair and effective warning that their actions were pro

hibited, and their conduct violated no standard required

by the plain language of the law or any earlier inter

pretation thereof.

3

S tatu to ry and C onstitu tional P rovisions Involved

1. This case involves Section 1 of the Fourteenth Amend

ment to the Constitution of the United States.

2. This case also involves Section 16-386, Code of Laws

of South Carolina for 1952, as amended, which states:

Entry on lands of another after

notice prohibiting same

Every entry upon the lands of another where any

horse, mule, cow, hog or any other livestock is pastured,

or any other lands of another after notice from the

owner or tenant prohibiting such entry shall be a mis

demeanor and be punished by a fine not to exceed one

hundred dollars or by imprisonment with hard labor

on the public works of the county for not exceeding

thirty days. When any owner or tenant of any lands

shall post a notice in four conspicuous places on the

borders of such land prohibiting entry thereon a proof

of the posting shall be deemed and taken as notice

conclusive against the person making entry as afore

said for the purpose of trespassing.

Statement

At approximately 11:00 A.M. on March 14, 1960, peti

tioners, two Negro college students entered the Eckerd’s

Variety Store in Columbia, South Carolina (R. 36, 49).

They seated themselves at a booth in the food department

and sought service (R. 7, 31, 33, 35, 49, 52). Both testified

they had money with which to purchase food (R. 3, 16,

38, 48, 51, 55). No one spoke to the petitioners or ap

proached them to take their order for food (R. 31, 32, 38).

After petitioners were seated an employee of the store

4

put up a chain with a “No Trespassing” sign (R. 35). Peti

tioners testified that white persons were seated in the food

department and were being served food at this time (R. 36,

37, 53, 54). They continued to sit in the booth for some

fifteen or twenty minutes (R. 30, 49). While waiting ser

vice, petitioners sat each with an open book before him

(R. 3, 16, 38, 51).

The manager of Eckerd’s called the Columbia police

(R. 32) who arrived and proceeded with the manager

directly to the booth where petitioners were seated (R. 3, 6).

The manager told petitioners to leave “ . . . because we

aren’t going to serve you” (R. 3, 12). Petitioners remained

seated and the Chief of Police then asked petitioners to

leave (R. 3, 50). When petitioners did not comply the

Chief of Police placed them under arrest (R. 3, 13). Bouie

asked the Chief of Police “for what” (R. 4, 5, 12). The

Chief then “reached and got him by the arm . . . and . . .

had to pull him out of the seat” (R. 4). The Chief then

seized him by the belt, gave him a “preliminary frisk,” and

marched him out of the store (R. 4, 17, 51). Bouie testified

that he offered no resistance and told the Chief “That’s

all right, Sheriff, I ’ll come on” (R. 51).

The Chief was asked on cross examination: Q. “Chief,

isn’t it a fact that the only reason you were called in from

the Police Department to arrest these two persons, was

because they were Negroes who were asking for srvice

(sic) in the food department in Eckerd’s drug store, and

the manager was directing them out because they were

Negroes? Isn’t that correct?” A. “Why certainly, I would

think that would be the case” (R. 20, 21).

Eckerd’s, one of Columbia’s larger variety stores is part

of a regional chain with numerous stores located through

out the South (R. 19, 29). In addition to the food depart-

5

ment, Eckerd’s maintains other departments including retail

drug, cosmetic and prescriptions (R. 20, 29). Negroes and

whites are invited to purchase and are served alike in all

departments of the store with the single exception that

Negroes “have never been” served in the food department

which is reserved for whites (R. 29, 30, 52). Negroes are

not served in the food department because as the store

manager put it, “ . . . all the stores do the same thing”

(R. 31). There was, however, no evidence that any signs

or notices are present in the store indicating that Negroes

are not served at the lunch counter.

Throughout the events that led to their arrest, petitioners

were completely orderly and peaceful (R. 9, 35).

Petitioners were charged with trespass in violation of

Section 16-386 as amended of the Code of Laws of South

Carolina, infra, p. 10a. Section 16-386 states:

Entry on lands of another after

notice prohibiting same.

“Every entry upon the lands of another where any

horse, mule, cow, hog or any other livestock is pastured,

or any other lands of another, after notice from the

owner or tenant prohibiting such entry shall be a

misdemeanor and he punished by imprisonment with

hard labor on the public works of the county for not

exceeding thirty days. When any owner or tenant of

any lands shall post a notice in four conspicuous places

on the borders of such land prohibiting entry thereon

a proof of the posting shall he deemed and taken as

notice conclusive against the person making entry as

aforesaid for the purposes of trespassing.”

Petitioners were also charged with breach of the peace

in violation of Section 15-909, Code of Laws of South Caro-

6

lina, 1952, infra, p. 10a. Petitioner Bouie was also charged

with the common law crime of resisting arrest, infra, p. 10a.

Petitioners were tried in the Recorder’s Court of the

City of Columbia without a jury and convicted of trespass

in violation of Section 16-386 and sentenced to pay fines

of $100.00 or serve thirty days in jail, $24.50 of the fines

being suspended. Petitioner Bouie was convicted of resist

ing arrest and fined $100.00 or thirty days, $24.50 of the fine

being suspended. Bouie’s sentences were to run consecu

tively (R. 62, 63).

Petitioners appealed to the Richland County Court which

sustained the judgments and sentences of the Recorder’s

Court of the City of Columbia on April 28, 1961, infra,

pp. 3a-9a.

Petitioners thereupon appealed to the Supreme Court

of South Carolina which affirmed the judgment of convic

tion of trespass in violation of Title 16, Section 386 of

the 1952 Code of Laws of South Carolina, as amended,

and reversed the judgment of conviction against petitioner

Bouie for resisting arrest on February 13, 1962, infra,

pp. 10a-13a. The Supreme Court of South Carolina denied

rehearing on March 7, 1962, infra, p. 14a.

How the Federal Questions Were Raised

and Decided Below

At the close of the Prosecution’s case in the Recorder’s

Court of the City of Columbia, petitioners moved to dis

miss the charges against them on the grounds, inter alia,

that (R. 25, 26, 65-66):

“ . . . for the State to stand idly by and allow a private

individual in public business to discriminate against

the defendants on the basis of race and color alone

7

and then for the State to back up this discrimination

by State action in ejecting, arresting and subjecting

to trial these defendants is a denial of due process

of law and a denial of the equal protection of the

laws as guaranteed by the 14th Amendment of the

United States Constitution.

The defendants move to dismiss the charges of tres

pass and breach of the peace, in violation of State

Statutes Section 16-386 and 15-909, on the ground that

evidence proves that the defendants were merely at

tempting to exercise their rights as business invitees

of a business catering to the general public to exercise

the freedom of being served by said business on a

non-discriminating basis without regard to race and

color and in so doing were not guilty of any crime.

Further, the defendants move to dismiss all charges

against them on the ground that to deprive them of

their liberty to enter such a business establishment

as the record describes and be served as others, and

that to be ejected and arrested by agents of the State

—the police—solely on the basis of race and color,

and to be singled out as the only persons ejected while

others remain, is a denial of due process of law and

the equal protection of the laws as guaranteed by the

14th Amendment of the United States Constitution.”

The motion was overruled by the trial Court (R. 26).

Petitioners moved to dismiss the charges against them

on the same grounds at the close of trial (R. 60, 63-66).

This motion was denied by the trial Court (R. 60, 61-63).

Subsequent to judgment of conviction in the trial Court

petitioners moved for arrest of judgment or in the alterna

tive a new trial on the ground that:

8

“ . . . State Code No. 16-386, as amended, trespass

and State Code No. 15-909, breach of peace, though

constitutional on their faces, are as to these defen

dants, unconstitutionally applied, thus denying to these

defendants due process of law and equal protection

of the laws, in violation of the 14th Amendment of

the United States Constitution . . . ” (R. 68).

The motion for arrest of judgment or in the alternative

for a new trial was supported by the same grounds as

petitioners’ motions to dismiss (R. 68-69). This motion

was denied by the trial Court (R. 61).

Petitioners appealed to the Richland County Court re

newing the constitutional objections to their convictions

relied upon in the trial Court. The Richland County Court

held that the proprietor of a restaurant can choose his

customers on the basis of color without violating consti

tutional provisions and that in aiding his policy of exclu

sion the State of South Carolina was not enforcing racial

discrimination (R. 71, 74). The Court also held:

The Defendants, under South Carolina law, had no

right to remain in the stores after the manager asked

them to leave. Shramek v. Walker, 149 S. E. 331, 152

S. C. 88. As the Court quoted the rule, “while the

entry by one person on the premises of another may

be lawful, by reason of express or implied invitation

to enter, his failure to depart, on the request of the

owner, will make him a trespasser, and justify the

owner in using reasonable force to eject him” (R.

72-73).

Petitioners appealed to the Supreme Court of South

Carolina claiming error in that the Court below refused

(R. 76, 77):

9

“ . . . to hold that the evidence shows conclusively that

the arresting officers acted in the furtherance of a

custom, practice and policy of discrimination based

solely on race or color, and that the arrests and con

victions of appellants under such circumstances are

a denial of due process of law and the equal protection

of the laws, secured to them by the Fourteenth Amend

ment to the United States Constitution.

4. The Court erred in refusing to hold that the

evidence establishes merely that at the time of their

arrests appellants were peaceably upon the premises

of Eckerd’s drug store as customers, visitors, busi

ness guests or invitees of a business establishment

performing economic functions invested with the public

interest, and that the procurement of the arrest of

appellants by management of said establishment under

such circumstances in furtherance of a custom, prac

tice and policy of racial discrimination is a violation

of rights secured appellants by the due process and

equal protection clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment

to the United States Constitution.”

The Supreme Court of South Carolina affirmed peti

tioners’ conviction of trespass in violation of Title 16-

Section 386, as amended, of the 1952 Code of Laws of

South Carolina, holding that appellants’ contention that

“arrest by the police officer at the instance of the store

manager, and the convictions of trespass that followed,

were in furtherance of an unlawful policy of racial dis

crimination and constituted state action in violation of

appellants’ right under the Fourteenth Amendment” had

been made, considered and rejected previously by the Court.

The cases relied upon by the Supreme Court of South

Carolina were City of Greenville v. Peterson, ----- S. C.

——, 122 S. E. (2d) 826 (Petition for Writ of Certiorari

10

No. 750 filed 30 U. S. L. Week 3274); City of Charleston

v. Mitchell, ------ S. C. ---- , 123 S. E. (2d) 512 (Petition

for Writ of Certiorari No. 846 filed 30 IT. S. L. Week 3324);

City of Columbia v. B arr,----- S. C. ----- , 123 S. E. (2d)

521 (Petition for Writ of Certiorari No. 847 filed 30 U. S. L.

Week 3324).

The Supreme Court of South Carolina reversed peti

tioner Bouie’s conviction for resisting arrest on the ground

that the “momentary delay” of petitioner in responding to

the officer’s command did not amount to “resistance.”

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE WRIT

I.

The D ecision Below Conflicts W ith Prior Decisions o f

This Court W hich Condemn the Use o f State Power to

Enforce Racial Segregation.

Petitioners were not served in Eckerd’s because they

were Negroes and the custom of the City of Columbia is

that Negroes may not he served at restaurants which also

cater to whites (R. 31). See Petition for Writ of Certiorari

in City of Columbia v. Barr, et at., No. 847 filed in this

Court 30 U. S. L. Week 3324. As the store manager put

it “all stores do the same thing” (R. 31). It is also apparent

that the arrests were made to support this discrimination.

On cross examination the arresting officer was asked:

Q. “Chief, isn’t it a fact that the only reason you

were called in from the Police Department to arrest

these two persons was because they were Negroes who

were asking for srvice (sic) in the food department in

Eckerd’s drug store, and the manager was directing

them out because they were Negroes'? Isn’t that cor-

11

rectf” A. “Why certainly, I would think that would

he the case” (B. 20, 21).

The trial court convicted petitioners on evidence plainly

indicating that race and race alone was the reason they

were ordered to leave the restaurant.

The Supreme Court of South Carolina recognized the

issue in this case to he whether police and judicial enforce

ment of Eckerd’s racial discrimination policy violated the

equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

" . . . the contention [is] that appellants’ arrest hy the

police officer at the instance of the store manager, and

the convictions of trespass that followed, were in fur

therance of an unlawful policy of racial discrimination

and constituted state action in violation of appellants’

rights under the Fourteenth Amendment” (infra, p.

12a).

It answered this question contrary to petitioners’ posi

tion hy relying upon cases, involving similar issues, which

are now pending before this Court, e.g. Columbia v. Barr,

----- g. C .----- 123 S. E. 2d 521, No. 847 October Term,

1961; City of Greenville v. Peterson, ----- S. C. ----- , 122

S. E. 2d 826 (No. 750, October Term, 1961); Charleston v.

Mitchell,----- S. C .------ , 123 S. E. 2d 512 (No. 846 October

Term, 1961).

But the decision is contrary to a growing body of prin

ciples declared by this Court. Where there is state action

by the police, Screws v. United States, 325 U. S. 91; Monroe

v. Pape, 365 U. S. 167; prosecutors, Napue v. Illinois, 360

U. S. 264, and judiciary, Shelly v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1,

14-18; Boynton v. Virginia, 364 U. S. 454, racial discrimina

tion supported by state authority violates the Fourteenth

Amendment. Civil Rights Cases, 109 U. S. 3, 17.

12

It is asserted, however, that the state is not enforcing

racial discrimination, hat is implementing a property right.

But to the extent that management was asserting a “prop

erty” right to enforce racial segregation according to the

custom of the City of Columbia, it becomes pertinent to

inquire just what that property right is. See Henkin,

“Shelley v. Kraemer: Notes for a Revised Opinion,” 110

U. of Penn. L. Rev. 473, 494-505.

The mere fact that “property” is involved does not settle

the matter, Shelly v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1, 22. “Dominion

over property springing from ownership is not absolute

and unqualified.” Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S. 60, 74;

United States v. Willow River Power Co., 324 U. S. 499,

510; Marsh v. Alabama, 326 U. S. 501, 506; cf. Munn v.

Illinois, 94 U. S. 113; Republic Aviation Corp. v. N. L. R. B.,

324 U. S. 793, 796, 802; Goldblatt v. Town of Hempstead,

30 U. S. L. Week 4343.

Eckerd’s is a commercial variety store open to the public

generally for the transaction of business, including the

sale of food and beverages in its restaurant. It does not

seek to keep everyone, or Negroes, or these petitioners

from coming upon the premises. The white public is invited

to use all the facilities of the store and Negroes are invited

to use all these facilities except the restaurant. The man

agement does not seek to exclude petitioners because of

an arbitrary caprice, but rather, follows the community

custom of Columbia which is, in turn, supported and

nourished by law.

The portion of the store from which petitioners are

excluded is not set aside for private or non-public use as

an office reserved for the management or lounge or private

restroom for employees. Petitioners did not seek to use

the restaurant for any function inappropriate to its normal

use. They merely sought food service. Therefore, it ap

pears that the property interest which the State protects

13

here, by arrest, prosecution, and criminal conviction, is

the claimed right to open the premises to the public gen

erally, including Negroes, for business purposes, including

the sale of food and beverages, while racially discriminating

against Negroes, as such, at one integral part of the facili

ties. While this may, indeed, be a property interest, the

question before this Court is whether the State may enforce

it without violating the Fourteenth Amendment. This prop

erty interest certainly may be taken away by the State

without violating the Fourteenth Amendment. Western

Turf Asso. v. Greenberg, 204 U. S. 359; Railway Mail Assn.

v. Corsi, 326 U. S. 88; Pickett v. Kuchan, 323 111. 138, 153

N. E. 667, 49 A. L. E. 499 (1926); People v. King, 110

N. Y. 419, 18 N. E. 245 (1888); Annotation 49 A. L. E. 505;

cf. District of Columbia v. John R. Thompson Co., 346

U. S. 100; Henkin, supra at p. 499 n. 52.

Many states make it a crime to engage in the racially

discriminatory use of private property which South Caro

lina enforces here. For the latest collection of such statutes,

see Konvitz, A Century of Civil Rights (1961), passim.

Indeed, Eckerd’s has sought to achieve in this case some

thing which the State itself could not permit it to do on

state property leased to it for business use. Burton v.

Wilmington Parking Authority, 365 U. S. 715, or require

or authorize it to do by positive legislation. See Mr.

Justice Stewart’s concurring opinion in Burton, supra.

Although it does not necessarily follow from the fact that

some states constitutionally may make racial discrimina

tion on private property criminal, that other states may

not enforce racial discrimination, it does become evident

that Eckerd’s property interest is hardly inalienable or

absolute.

Basic to the disposition of this case is that Eckerd’s is

a public establishment open to serve the public as a part

of the public life in the community. See Garner v. Louisiana,

14

368 U. S. 157, 176, Mr. Justice Douglas concurring. The

case involves no genuine claim that Eckerd’s right to “pri

vate” use of its property was interfered with by petitioners.

To uphold petitioners’ claims here affects only slightly the

entire range of what are called private property rights.

For if Eckerd’s is disabled by the Fourteenth Amendment

from enforcing by state action racial bias at its public

lunch counter, homeowners are hardly disabled from en

forcing their private rights even to implement racial preju

dices. See Henkin, supra at pp. 498-500. There is a con

stitutional right of privacy protected by the due process

clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. Mapp v. Ohio, 367

IT. S. 643, 6 L. ed. 2d 1081, 1080, 1103, 1104; see also Poe

v. Ullman, 367 U. S. 497, 6 L. ed. 2d 989, 1006, 1022-1026

(dissenting opinions). This Court has recognized the re

lationship between right of privacy and property interests.

Thornhill v. Alabama, 310 U. S. 88, 105-106; Breard v.

Alexandria, 341 IT. S. 622, 626, 638, 644. Only a very abso

lutist view of the property right to determine who may

come or stay on one’s property on racial grounds would

require that a unitary principle apply to the whole range

of property uses, public connections, dedications, and pri

vacy interests which may be at stake. Petitioners certainly

do not contend that the principles urged to prevent the

use of trespass laws to enforce racial discrimination in a

restaurant operated for profit as a public business would

prevent the state from enforcing a similar bias in a private

home or office where the right of privacy has its greatest

meaning and strength.1 As Mr. Justice Holmes stated in

Hudson County Water Co. v. McCarter, 209 IT. S. 349, 355:

/T h e right of privacy cannot be destroyed by resort to the

niceties of property law. Chapman v. United States, 365 U. S. 610,

617. “Rights of liberty and property, of privacy and voluntary

association, must be balanced, in close cases, against the right

not to have the state enforce discrimination . . . ” Henkin, “Shelley

v. Kraemer: Notes for a Revised Opinion,” 110 U. of Penn L

Rev. 473, 496, 490-505.

15

All rights tend to declare themselves absolute to their

logical extreme. Yet all in fact are limited by the

neighborhood of principles of policy which are other

than those on which the particular right is founded,

and which become strong enough to hold their own

when a certain point is reached.

Where a right of private property is asserted by a pro

prietor so narrowly as to claim state intervention only

in barring Negroes from a single portion of a public es

tablishment, and that restricted assertion of right collides

with the great immunities of the Fourteenth Amendment,

petitioners respectfully submit that the propery right is

no right at all.

Moreover, the assertion of racial prejudice here is not

“private” at all. The segregation here enforced is that

demanded by custom of the City of Columbia. While “cus

tom” is referred to in the Civil Rights Cases as one of the

forms of state authority within the prohibitions of the

Fourteenth Amendment, 109 U. S. 3, 17 (see also Mr.

Justice Douglas concurring in Garner v. Louisiana, 368

U. S. 157, 179, 181), Columbia’s custom exists in a context

of massive state support of racial segregation.2

2 See S. C. A. & J. R. 1952 (47) 2223, A. & J. R. 1954 (48) 1695

repealing S. C. Const. Art. 11, §5 (1895) (which required legis

lature to maintain free public schools). S. C. Code §§21-761 to 779

(regular school attendance) repealed by A. & J. R. 1955 (49) 85;

§21-2 (appropriations cut off to any school from which any pupil

transferred because of court order; §21-230(7) (local trustees may

or may not operate schools); §21-238 (1957 Supp.) (school offi

cials may sell or lease school property whenever they deem it

expedient) ; S. C. Code §40-452 (1952) (unlawful for cotton

textile manufacturer to permit different races to work together

in same room, use same exits, bathrooms, etc., $100 penalty and/or

imprisonment at hard labor up to 30 days; S. C. A. & J. R. 1956

16

Consequently, we have here state-nurtured and state-

enforced racial segregation in a public institution con

cerning which no property right may be asserted in the

face of the Fourteenth Amendment’s prohibition of state

enforced racial segregation. This state enforced segrega

tion conflicts with Fourteenth Amendment principles which

have been consistently asserted by this Court.

II.

The D ecision Below Conflicts With D ecisions o f This

Court Securing the Right o f Freedom of Expression

Under the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution

of the United States.

Petitioners were engaged in the exercise of free ex

pression by means of nonverbal requests for nondiscrim-

inatory food service which were implicit in their con

tinued remaining in the food department when refused

service. The fact that sit-in demonstrations are a form

of protest and expression was observed in Mr. Justice

Harlan’s concurrence in Garner v. Louisiana, supra. Peti

tioners’ expression (seeking service) was entirely appro

priate to the time and place at which it occurred. Peti

tioners did not shout, obstruct the conduct of business,

or engage in any expression which had that effect. There

p ° \ Park inv°lved in desegregation su it) ; S. C.

Stafp p J \ (Supp.) (providing for separate

btate Parks); §51-181 (separate recreational facilities in cities

with population m excess of 60,000); §5-19 (separate entrances at

circus); S. C. Code Ann. Tit. 58, §§714-720 (1952) (segregation

m travel facilities). On April 5, 1962, the City of Greenville,

bouth Carolina arrested and charged a Negro with the crime of

violating Sec 31.10. The Code of City of Greenville S. C. 1953.

Be Unlawful for Colored person to occupy Residence in White

Block (arrest and trial warrant No. 179, City v. Robinson). Cf

Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S. 60.

17

were no speeches, picket signs, handbills or other forms

of expression in the store which were possibly inappro

priate to the time and place. Rather petitioners merely

expressed themselves by offering to make purchases in a

place and at a time set aside for such transactions. Their

protest demonstration was a part of the “free trade in

ideas” (Abrams v. United States, 250 U. S. 616, 630,

Holmes, J., dissenting), and was within the range of lib

erties protected by the Fourteenth Amendment, even though

nonverbal. Stromberg v. California, 283 U. S. 359 (display

of red flag); Thornhill v. Alabama, 310 U. S. 88 (picketing);

West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnette, 319

U. S. 624, 633-624 (flag salute); N. A. A. C. P. v. Alabama,

357 U. S. 449 (freedom of association).

Petitioners do not urge that there is a Fourteenth Amend

ment right to free expression on private property in all

cases or circumstances without regard to the owner’s pri

vacy, and his use and arrangement of his property. This

is obviously not the law. In Breard v. Alexandria, 341 IT. S.

622 the Court balanced the “householder’s desire for pri

vacy and the publisher’s right to solicit on a door-to-door

basis. But cf. Martin v. Struthers, 319 IT. S. 141 where

different kinds of interests were involved with a correspond

ing difference in result.

The character of petitioners’ right to free expression is

not defined merely by reference to the fact that private

property rights are involved. The nature of the property

rights asserted and of the state’s participation through

its officers, its customs, and its creation of the property

interest, have all been discussed above in connection with

the state action issue as it related to racial discrimination.

Similar considerations should aid in resolving the free

expression question.

18

In Garner v. Louisiana, Mr. Justice Harlan, concurring,

found a protected area of free expression on private prop

erty on facts regarded as involving “the implied consent

of the management” for the sit-in demonstrators to remain

on the property. It is submitted that even absent the

owner’s consent for petitioners to remain on the premises

of this business establishment, a determination of their

free expression rights requires consideration of the totality

of circumstances respecting the owner’s use of the property

and the specific interest which state judicial action is sup

porting. Marsh v. Alabama, 326 U. S. 501.

In Marsh, swpra, this Court reversed trespass convictions

of Jehovah’s Witnesses who went upon the privately owned

streets of a company town to proselytize for their faith,

holding that the conviction violated the Fourteenth Amend

ment. In Republic Aviation Corp. v. N. L. R. B., 324 U. S.

793, the Court upheld a labor board ruling that lacking

special circumstances employer regulations forbidding all

union solicitation on company property constituted unfair

labor practices. See Thornhill v. Alabama, supra, involving

picketing on company-owned property; see also N. L. R. B.

v. American Pearl Button Co., 149 F. 2d 258 (8th Cir.

1945); and compare the cases mentioned above with N. L.

R. B. v. Fansteel Metal Corp., 306 U. S. 240, 252, con

demning an employee seizure of a plant. In People v.

Barisi, 193 Misc. 934, 83 N. Y. S. 2d 277, 279 (1948) the

Court held that picketing within Pennsylvania Railroad

Station was not a trespass; the owners opened it to the

public and their property rights were “circumscribed by

the constitutional rights of those who use it.” See also

Freeman v. Retail Clerks Union, Washington Superior

Court, 45 Lab. Eel. Ref. Man. 2334 (1959); and State of

Maryland v. Williams, Baltimore City Court, 44 Lab Eel

Ref. Man. 2357, 2361 (1959).

19

In the circumstances of this case the only apparent state

interest being subserved by this trespass prosecution, is

support of the property owner’s discrimination in con

formity to the State’s segregation custom and policy. This

is all that the property owner has sought.

Where free expression rights are involved, the question

for decision is whether the relevant expressions are “in

such circumstances and . . . of such a nature as to create a

clear and present danger that will bring about the sub

stantive evil” which the state has the right to prevent.

Schenck v. United States, 249 U. S. 47, 52. The only “sub

stantive evil” sought to be prevented by this trespass

prosecution is the elimination of racial discrimination and

the stifling of protest against it; but this is not an “evil”

within the State’s power to suppress because the Fourteenth

Amendment prohibits state support of racial discrimination.

The fact that the arrest and conviction were designed to

short circuit a bona fide protest is strengthened by the

necessity of the state court to make a strained and novel

interpretation of the statute in order to bring petitioners’

conduct within its ambit. Petitioners’ conviction for tres

pass rests on an interpretation which flies in the face of

the plain words of the statute, all prior applications, and

ignores the most recent legislative amendment to said

statute. The trespass statute prior to amendment read:

Every entry upon the lands of another after notice

from the owner or tenant prohibiting such entry shall

be a misdemeanor and be punished by a fine not to ex

ceed one hundred dollars or by imprisonment with

hard labor on the public works of the county for not

exceeding thirty days. When any owner or tenant of

any lands shall post a notice in four conspicuous places

on the borders of such land prohibiting entry thereon

and shall publish once a week for four consecutive

20

weeks such notice in any newspaper circulating in the

county in which such lands are situated, a proof of

the posting and of publishing of such notice within

twelve months prior to entry shall be deemed and taken

as notice conclusive against the person making entry

as aforesaid for the purpose of hunting or fishing on

such land. (Code of Laws, South Carolina, 1952.)

The amended statute under which petitioners’ convictions

were had added the language which is italicized:

Every entry upon the lands of another where any

horse, mule, cow, hog or any other livestock is pas

tured, or any other lands of another . . .

The Legislature obviously limited the statute to trespass

on land primarily used for farm purposes. Petitioners

have been able to find no cases under the instant criminal

statute or its predecessors in which the trespass punished

was not for entry on land (generally farm land) or some

adjunctive land such as on the road.3 See State v. Green,

35 S. C. 266; State v. Mays, 24 S. C. 190; State v. Tenney,

58 S. C. 215; State v. Hallback, 40 S. C. 298; State v. Gray,

76 S. C. 83 (all cases of trespass on land or specifically

farm land). The amendment was merely declaratory, mak

ing explicit on the face of the statute the prior applications.

The action of the court below in extending the statute to

business premises, is, therefore, completely novel and un

supported by prior cases or the recent amendment.

3 The only exceptions being sit-in convictions presently pending

before this Court, Columbia v. Barr et al., 123 S. E. 2d 521 (1961)

(Petition for Certiorari No. 847 filed 30 U. S. L. Week 3324) ;

Charleston v. Mitchell, et al., 123 S. E. 2d 512 (1961) (Petition

for Certiorari No. 846 filed 30 U. S. L. Week 3324), which were

decided subsequent to the events which led to petitioners’ arrest

and conviction.

21

Further, the statute in terms prohibits only going on

the land of another after being forbidden to do so. The

Supreme Court of South Carolina has now construed the

statute to prohibit also remaining on property when di

rected to leave the following lawful entry. In short, the

statute is now applied as if “remain” were substituted for

“enter.” There is no history to support this second novel

construction of the statute. No South Carolina case has

ever adopted such a construction.4 See Note 3, supra p. 20.

Subsequent to petitioners’ conviction the legislature of

the State of South Carolina enacted into law Section 16-

388 a trespass statute making criminal failing and refus

ing “to leave immediately upon being ordered or requested

to do so” the premises or place of business of another. See

Petition for Writ of Certiorari in Peterson, et al. v. City

of Greenville, No. 750 filed in this Court, 30 U. S. L. Week

3276.

There is no question but that petitioners and all Negroes

were welcome in Eekerd’s—apart from the restaurant

(R, 29). The restaurant is an integral part of the store

and can only be reached by “entry” into the store proper—

to which petitioners were admittedly invited (R. 29). Ab

sent the special expansive interpretation given Section 16-

386 by the Supreme Court of South Carolina, the case

would plainly fall within the principle of Thompson v. City

of Louisville, 362 U. S. 199, and would be a denial of due

4 As authority for this construction the South Carolina Courts

cite Shramek v. Walker, 152 S. C. 88, 149 S. E. 331, which was a

civil suit for trespass. But civil and criminal trespass have long

been distinguished, the latter requiring, at common law, special

circumstances such as breach of the peace. Bex v. Storr, 3 Burr.

1698. Cf. American Law Institute, Model Penal Code, Tentative

Draft No. 2, §206.53, Comment.

22

process of law as a conviction resting upon no evidence of

guilt. There was obviously no evidence that petitioners

entered the premises “after notice . . . prohibiting such

entry” and the conclusion that they did rests solely upon

the special construction of the law.

Under familiar principles the construction given a state’s

statute by its highest court determines its meaning. Peti

tioners submit, however, that this statute lias been judi

cially expanded to the extent that it does not give a fair and

effective warning of the acts it now prohibits. Because of

the expansive construction, the statute now reaches more

than its words fairly and effectively define, and therefore,

as applied it offends the principle that criminal laws must

give fair and effective notice of the acts they prohibit.

The due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment re

quires that criminal statutes be sufficiently explicit to in

form those who are subject to them what conduct on their

part will render them criminally liable. “All are entitled

to be informed as to what the State commands or forbids”,

Lanzetta v. New Jersey, 306 U. S. 451, 453, and cases cited

therein in note 2.

Construing and applying federal statutes this Court has

long adhered to the principle expressed in Pierce v. United

States, 314 U. S. 206, 311:

. . . judicial enlargement of a criminal act by interpre

tation is at war with a fundamental concept of the com

mon law that crimes must be defined with appropriate

definiteness. Cf. Lametta v. New Jersey, 306 U. S. 451,

and cases cited.

In Pierce, supra, the Court held a statute forbidding false

personation of an officer or employee of the United States

inapplicable to one who had impersonated an officer of the

T. V. A. Similarly in United States v. Cardiff, 344 U. S.

174, this Court held too vague for judicial enforcement a

criminal provision of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cos

metic Act which made criminal a refusal to permit entry

of inspection of business premises “as authorized by” an

other provision which, in turn, authorized certain officers

to enter and inspect “after first making request and obtain

ing permission of the owner.” The Court said in Cardiff,

at 344 U. S. 174, 176-177,

The vice of vagueness in criminal statutes is the treach

ery they conceal either in determining what persons are

included or what acts are prohibited. Words which are

vague and fluid (cf. United States v. L. Cohen Gro

cery Co., 255 U. S. 81) may be as much of a trap for

the innocent as the ancient laws of Caligula. We can

not sanction taking a man by the heels for refusing to

grant the permission which this Act on its face ap

parently gave him the right to withhold. That would be

making an act criminal without fair and effective no

tice. Cf. Herndon v. Lowry, 301 U. S. 242.

The Court applied similar principles in McBoyle v. United

States, 283 U. S. 25, 27; United States v. Weitzel, 246 U. S.

533, 543, and United States v. Wiltberger, 18 U. S. (5

Wheat.) 76, 96. Through these cases run a uniform appli

cation of the rule expresed by Chief Justice Marshall:

It would be dangerous, indeed, to carry the principle,

that a case which is within the reason or mischief of

a statute, is within its provisions, so far as to punish

a crime not enumerated in the statute, because it is of

equal atrocity, or of kindred character, with those

which are enumerated (id. 18 U. S. (5 Wheat.) at 96).

The cases discussed above involved federal statutes con

cerning which this Court applied a rule of construction

24

closely akin to the constitutionally required rule of fair

and effective notice. This close relationship is indicated by

the references to cases decided on constitutional grounds.

The Pierce opinion cited for comparison Lametta v. New

Jersey, supra, and “cases cited therein,” while Cardiff

mentions United States v. L. Cohen Grocery Co., 255 U. S.

81 and Herndon v. Lowry, 301 U. S. 242.

On its face the South Carolina trespass statute warns

against a single act, i.e., entry upon the land of another

“after” notice prohibiting such. “After” connotes a se

quence of events which by definition excludes going on or

entering property “before” being forbidden. The sense of

the statute in normal usage negates its applicability to peti

tioners’ act of going on the premises with permission and

later failing to leave when directed.

Petitioners do not contend for an unreasonable degree of

specificity in legislative drafting. Some state trespass laws

have recognized as distinct prohibited acts the act of going

upon property after being forbidden and the act of re

maining when directed to leave.5 South Carolina passed a

statute punishing those who remain after being directed

5 See for example the following state statutes which do ef

fectively differentiate between “entry” after being forbidden

and “remaining” after being forbidden. The wordings of the

statutes vary but all of them effectively distinguish the situation

where a person has gone on property after being forbidden to do

so, and the situation where a person is already on property and

refuses to depart after being directed to do so, and provide

separately for both situations: Code of Ala., Title 14, §426;

Compiled Laws of Alaska Ann. 1958, Cum. Supp. Yol. I ll ,

§65-5-112; Arkansas Code, §71,1803; Gen. Stat. of Conn. (1958

Rev.), §53-103; D. C. Code §22-3102 (Supp. VII, 1956); Florida

Code, §821.01; Rev. Code of Hawaii, §312-1; Illinois Code,

§38-565; Indiana Code, §10-4506; Mass. Code Ann. C. 266, §120;

Michigan Statutes Ann. 1954, Vol. 25, §28.820(1) ; Minnesota Stat

utes Ann. 1947, Vol. 40, §621.57; Mississippi Code, §2411; Nevada

Code, §207.200; Ohio Code, §2909.21; Oregon Code, §164.460; Code

of Virginia, 1960 Replacement Volume, §18.1-173; Wyoming Code,

§6-226.

25

to leave two months after petitioners’ conviction, Section

16-388, Code of Laws of South Carolina. See supra, p. 21.

Converting, by judicial construction, the common English

word “entry” into a word of art meaning “remain” or

“trespass” has transformed the statute from one which

fairly warns against one act into a law which fails to ap

prise those subject to it “in language that the common

world will understand, of what the law intends to do if a

certain line is passed” (McBoyle v. United States, 283

U. S. 27). Nor does common law usage of the word “entry”

support the proposition that it is synonymous with “tres

pass” or “remaining.” While “entry” in the sense of going

on and taking possession of land is familiar (Ballentine,

“Law Dictionary” (2d Ed. 1948), 436; “Black’s Law Dic

tionary” (4th Ed. 1951), 625), its use to mean remaining

on land and refusing to leave it when ordered off is novel.

Judicial construction often has cured criminal statutes

of the vice of vagueness, but this has been construction

which confines, not expands, statutory language. Compare

Chaplinsky v. New Hampshire, 315 U. S. 568, with Herndon

v. Lowry, supra.

At the time of their arrest, petitioners were engaged in

the exercise of free expression by verbal and nonverbal

requests for nondiscriminatory lunch counter service, im

plicit in their continued remaining at the lunch counter

when refused service.

If in the circumstances of this case free speech is to

be curtailed, the least one has a right to expect is reason

able notice in the statute under which convictions are ob

tained. Winters v. New York, 333 L. S. 507. To uphold

petitioners’ conviction by novel and enlarged construction

of this statute is to violate the principle that when freedom

of expression is involved conduct must be proscribed within

a statute “narrowly drawn to define and punish specific

26

conduct as constituting a clear and present danger to a

substantial interest of the State”, Cantwell v. Connecticut,

310 U. S. 296, 307, 308; Garner v. Louisiana, 368 U. S. 157,

185 (Mr. Justice Harlan concurring). If the Supreme

Court of South Carolina can affirm the convictions of these

petitioners by such a construction it has exacted obedience

to a rule or standard that is so ambiguous and fluid as

to be no rule or standard at all. Champlin Rev. Co. v.

Corporation Com. of Oklahoma, 286 U. S. 210. But when

free expression is involved, the standard of precision is

greater; the scope of construction must, consequently, be

less. If this is the case when a State court limits a statute

it must a fortiori be the case when a State court expands

the meaning of the plain language of a statute. Winters

v. New York, 333 U. S. 507, 512.

As construed and applied, the law in question no longer

informs one what is forbidden in fair terms, and no longer

warns against transgression. This failure offends the

standard of fairness expressed by the rule against expan

sive construction of criminal laws which is embodied in the

due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

27

CONCLUSION

W herefore , for the foregoing reasons petitioners re

spectfully pray that the Petition for Writ of Certiorari

be granted.

Respectfully submitted,

J ack Greenberg

Constance Baker Motley

J ames M. Nabrit, III

Michael Meltsner

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

Matthew J . P erry

L incoln C. J enkins, J r.

1107% Washington Street

Columbia, South Carolina

Attorneys for Petitioners

APPENDIX

APPENDIX

Opinion o f the Recorder’s Court

I n th e

RECORDER’S COURT OF THE CITY OF COLUMBIA

City of Columbia,

•v.—

S imon Bouie and T almadge J. Neal.

The Court: I ’m prepared to hand down an opinion. In

the ease of Stramack (?) v. Walker, 149 Southeastern, Mr.

Justice Cothran, who is one of the ablest members of the

Supreme Court of this State, wrote the opinion of the Court

and that was decided on August 27, 1929. This was a suit

for damages where an individual remained in a building

after having been ordered by the owner to depart. He

refused to leave the building and was forcibly ejected by

the owner. In this case Mr. Justice Cothran, speaking for

the Court, said: “The law is well settled as thus expressed

in our own case of State v. Lazarus, 1, Mills, Constitution

34: “The Prosecutor having business to transact with him,

had a right to enter his house but if he remained after

having been ordered to depart, might have been put out of

the house. The defendant using no more violence than was

necessary to accomplish this object and showing to the

satisfaction of the Court and the jury, that this was his

object.” Now, I might add that in Second Ruling Case

Law, 559, the law is stated very succinctly and very prop

erly : “It is a well settled principle that the occupant of any

house, store or other building, has the legal right to control

2a

Opinion of the Recorder’s Court

it and to admit whom he pleases to enter and remain there

and that he also has the right to expel from the room or

building anyone who abuses the privilege which has been

thus given to him. Therefore, while the entry by one person

on the premises of another may be lawful by reason of

express or implied invitation to enter, his failure to depart

on the request of the owner will make him a trespasser

and justify the owner in using reasonable force to eject

him.” That’s a quotation from Ruling Case Law and I

think that law is well settled in South Carolina and I might

say in the United States, and furthermore, under the case

which I stated some time ago during the early part of the

morning, the Circuit Court of Appeals has held that the

private owner of a business has a perfect right to control

it and to do business with anybody he pleases to do busi

ness with. That applies not only to Howard Johnson but

I think in the case involved, which is Eckerd’s, they’ve got

a perfect legal right to do business and transact business

with anybody they want to do business with, and if they

invite them to leave and request them to leave and if they

refuse to do it, then they have every right under the law

to use such force as may be necessary to eject them.

It is therefore the opinion of this Court that the defen

dants are guilty, and the fine of the Court against Simon

Bouie is $100.00 or 30 days, for trespassing, and I suspend

$24.50 of that, and on resisting arrest, the fine of the

Court is $100.00 or 30 days, of which amount the sum of

$24.50 is suspended, said fines to run consecutively.

The judgment of the Court is in the case of Talmadge

J. Neal, the fine of the Court is that he pay a fine of $100.00

or serve 30 days, provided that the sum of $24.50 is sus

pended.

3a

Order o f the Richland County Court

City of Columbia,

S imon B ouie and T almadge J. Neal.

These Appeals from the Recorder’s Court of The City

of Columbia were orally argued together before me and

taken under advisement. The facts are largely undisputed.

All of the Defendants are Negroes. Eckerd’s Drug Store

and Taylor Street Pharmacy are separate stores in The

City of Columbia. Besides filling prescriptions, each sells

drugs and sundries and has a section where lunch, light

snacks and soft drinks are served. Trade is with the gen

eral public in all the departments except the lunch depart

ment where only white people are served.

On one occasion, Bouie and Neal went into Eckerd’s and

on another day the other Defendants went into the Taylor

Street Pharmacy, sat down in the lunch department and

waited to be served. All said they intended to be arrested.

In each case, the manager of the store came up to them

with a peace officer and asked them to leave. They refused

to do so and were then placed under arrest and charged

with trespass and breach of the peace. Bouie, in addition,

was charged with resisting arrest. It is undenied that he

resisted.

Bouie and Neal were tried on March 25, 1960, and the

other Defendants on March 30, 1960, before The Honorable

John I. Rice, City Recorder of Columbia, without a jury;

trial by jury having been waived by all the Defendants.

4a

Order of the Richland County Court

All the Defendants were convicted and sentenced and

these appeals followed. Motions raising the constitutional

questions were timely made.

There are 16 grounds of Appeal in the Bouie and Neal

proceeding and 13 grounds of appeal in the proceeding

involving the other Defendants, raising the following ques

tions : (1) Did the State deny Defendants, who are Negroes,

due process of law and equal protection of the laws within

the Federal and State Constitutions either by using its

peace officers to arrest them or by charging them with

violating Secs. 16-386 (Criminal Trespass) and 15-909

(Breach of Peace) of the Code of Laws of South Carolina,

1952, as amended, when they refused to leave a lunch

counter when asked by the manager thereof to do so?

(Bouie and Neal Nos. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, and

15; other Defendants, Nos. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12

and 13.) (2) Was there any substantial evidence pointing

to the guilt of the Defendants? (Bouie and Neal, No. 8;

other Defendants, No. 7.)

Since Defendants did not argue Bouie and Neal’s Excep

tions 7, 9 and 16, I have considered them abandoned.

The State has not denied Defendants equal protection of

the laws or due process of law within the Federal or State

Constitutional provisions.

A lunch room is like a restaurant and not like an inn.

The difference between a restaurant and an inn is ex

plained in Alpaugh v. Wolverton, 36 S. E. (2d) 907 (Court

of Appeals of Virginia) as follows:

“The proprietor of a restaurant is not subject to the

same duties and responsibilities as those of an inn

keeper, nor is he entitled to the privileges of the latter.

28 A. Jr., Innkeepers, No. 120, p. 623; 43 C. J. S., Inn

keepers, No. 20, subsection b, p. 1169. His responsi

bilities and rights are more like those of a shopkeeper.

5a

Order of the Richland County Court

Davidson v. Chinese Republic Restaurant Co., 201

Mich. 389, 167 N. W. 967, 969, L. R. A. 1919 E, 704.

He is under no common-law duty to serve anyone who

applies to him. In the absence of statute, he may

accept some customers and reject others on purely per

sonal grounds. Nance v. Mayflower Tavern Inc., 106

Utah 517, 150 P. (2d) 773, 776; Nolle v. Iliggins, 95

Misc. 328, 158 N. Y. S. 867, 868.”

And the proprietor can choose his customers on the basis

of color without violating constitutional provisions. State

v. Clyburn, 101 S. E. (2d) 295, 247 N. C. 455; Williams v.

Howard Johnson’s Restaurant, 268 F. (2d) 845; Slack v.

Atlantic Whitetower, etc., 181 F. Sup. 124 (Dist. Court

Md.), 284 F. (2d) 746.

In the Williams case, supra, Judge Soper, speaking for

the Court of Appeals for The Fourth Circuit, said: “As an

instrument of local commerce, the restaurant is not subject

to the Constitution and statutory provisions above (Com

merce Clause and Civil Rights Acts of 1875), and is at

liberty to deal with such persons as it may select.”

And in Boynton v. Virginia, ----- U. S. ----- , 81 S. Ct.

182, 5 L. Ed. (2d) 206, The Supreme Court of The United

States took care to state:

“Because of some of the arguments made here it is

necessary to say a word about what we are not de

ciding. We are not holding that every time a bus

stops at a wholly independent roadside restaurant

the Interstate Commerce Act requires that restaurant

service be supplied in harmony with the provisions of

that Act. We decide only this case, on its facts, where

circumstances show that the terminal and restaurant

operate as an integral part of the bus carrier’s trans

portation service for interstate passengers.”

6a

Order of the Richland County Court

I have reviewed all of the eases cited by both the City

and the Defendants, and in addition have reviewed subse

quent cases of the Court of Appeals and The United States

Supreme Court, including the case of Burton v. Wilming

ton Parking Authority, handed down on April 17, 1961, and

find none applicable or controlling except the Williams and

Slack cases, supra.

The Defendants, under South Carolina Law, had no right

to remain in the stores after the manager asked them to

leave. Shramek v. Walker, 149 S. E. 331, 152 S. C. 88. As

the Court quoted the rule, “while the entry by one person

on the premises of another may be lawful, by reason of

express or implied invitation to enter, his failure to depart,

on the request of the owner, will make him a trespasser,

and justify the owner in using reasonable force to eject

him.”

If the manager could have ejected Defendants himself,

he could call upon officers of the law to eject them for him.

Since the Defendants refused to leave, they were crim

inal trespassers under Sec. 15-909 of The Code of Laws of

South Carolina, 1952, and their conviction was proper.

Shelly v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1, 92 L. Ed. 845, 68 S. Ct.

836, 3 A. L. R. (2d) 441, and Barrows v. Jackson, 346 U. S.

249, 97 L. Ed. 1586, 73 Supreme Court 1031 cited by the

Defendants are not in point. In both of these cases, there

had been a sale of real estate to a non-caucasian in violation

of restrictive covenants. In the Shelley case, the Court

held that the equity of court of the State could not be

used against the non-caucasian to enforce the covenant.

In the Barrows case, the court held that the covenant could

not be enforced by an action at law for damages against

the co-covenanter, who broke the covenant.

7a

Order of the Richland County Court

In both of these cases, there were willing sellers and

willing purchasers. The purchasers paid their money and

entered into possession. Having entered, they had a right

to remain.

In the cases before the Court, there were no two willing

parties to a contract. True, the Defendants wanted to buy,

but the storekeeper did not want to sell and the Defendants

had no right to remain after being asked to leave. A white

person would not have the right to remain after being

asked to leave either. In either case, a person would be a

trespasser. The Constitutions provide for equal rights,

not paramount rights.

I have only to pick up my current telephone directory

and look in the yellow pages to find at least four establish

ments listed under “Restaurants” that advertise that they

are for colored or for colored only.

To say that a white proprietor may not call upon a police

man to remove or arrest a Negro trespasser or a Negro

proprietor cannot call upon a policeman to remove or ar

rest a White trespasser would lead to confusion, lawless

ness and possible anarchy. Certainly, the Constitutions

intended no such result.

The fundamental fallacy in the argument of Defendants

is the classification of the stores and lunch counters as pub

lic places and the operations thereof as public carriers.

A person, whatever his color, enters a public place or

carrier as a matter of right. The same person, whatever

his color, enters a store or restaurant or lunch counter by

invitation.

That person’s right to remain in a public place depends

upon the law of the land, and in a public carrier upon such

law and such reasonable rules as the carrier may make, and,

8a

Order of the Richland County Court

under the Constitution, neither the law nor rules may dis

criminate upon the basis of color.

On the other hand, the same person has no right to enter

a store, a restaurant, or lunch counter unless and until in

vited, and may remain only so long as the invitation is

extended. Whether he enters or remains depends solely

upon the invitation of the storekeeper, who has a full choice

in the matter. The operator can trade with whom he wills,

or he can, at his own whim and pleasure, close up shop.

There is no question but that the Defendants are guilty.

They were asked to leave and they refused. They, there

upon, were trespassers and such constituted a breach of the

peace. In addition, Bouie admittedly resisted a lawful ar

rest.

The trespass statute (Section 16-386, as amended, Code

of Laws of South Carolina, 1952) is not restricted to “pas

ture or open hunting lands” as defendants argue. The stat

ute specifically says “any other lands”. In Webster’s New

International Dictionary, the definition of “land” in “Law”

is as follows:

“ (a) any ground, soil, or earth whatsoever, regarded

as the subject of ownership, as meadows, pastures,

woods, etc., and everything, annexed to it, whether by

nature, as trees, water, etc., or by man, as buildings,

fences, etc., extending indefinitely vertically upwards

and downwards, (b) An interest or estate in land;

loosely any tenement or hereditament.”

The statute thus applies everywhere and without discrim

ination as to color. There is no question but that it was de

signed to keep peace and order in the community.

Since Defendants had notice that neither store would

serve Negroes at their lunch counters, they were trespassers

9a

Order of the Richland County Court

ab initio. Aside from this, however, the law is that even

though a person enters property of another by invitation,

he becomes a trespasser after he has been asked to leave.

Shramek v. Walker, supra.

For the reasons herein stated, I am of the opinion that

the judgments and sentences of the Recorder should be sus

tained and the Appeals dismissed, and it is so Ordered.

s / J ohut W. Chews,

Judge, Richland County Court.

Columbia, S. C.,

April 28, 1961.

10a

Opinion o f the Supreme Court o f South Carolina

I n the

SUPREME COURT OF SOUTH CAROLINA

T he City oe Columbia,

Respondent,

S imon B ouie and T almadge J. Neal,

Appellants.

Appeal From Richland County

John W. Crews, County Judge

Filed February 13,1962

A eeirmed in P art ;

Reversed in P art

L egge, A. J . : The appellants Simon Bouie and Talmadge

J. Neal, Negro college students, were arrested on March

14, 1960, and charged with trespass (Code, 1952, Section

16-386 as amended) and breach of the peace (Code, 1952,

Section 15-909). Bouie was also charged with resisting

arrest. On March 25, 1960, they were tried before the

Recorder of the City of Columbia, without a jury. Both

were found guilty of trespass; Bouie guilty also of resisting

arrest. Bouie was sentenced to pay a fine of one hundred

($100.00) dollars or to imprisonment for thirty (30) days

on each charge, twenty-four and 50/100 ($24.50) of each

fine being suspended and the prison sentences to run con-

11a

Opinion of the Supreme Court of South Carolina

secutively. Neal was sentenced to pay a fine of one hundred

($100.00) dollars, of which twenty-four and 50/100 ($24.50)

was suspended, or to imprisonment for thirty (30) days.

On appeal to the Richland County Court the judgment of

the Recorder’s Court was affirmed by order dated April 28,

1961, from which this appeal comes.

Eckerd’s one of Columbia’s larger drugstores, in addi

tion to selling to the general public drugs, cosmetics and

other articles usually sold in drugstores, maintains a

luncheonette department. Its policy is not to serve Negroes

in that department.

On March 14, 1960, about noon, the appellants entered

this drugstore and sat down in a booth in the luncheonette

department for the purpose, according to their testimony,

of ordering food and being served. Neal testified that it

was his intention to be arrested; Bouie testified that he

knew of the store’s policy not to serve Negroes in that

department, and that it was his purpose also to be ar

rested “if it took that”. No employee of the store ap

proached them, and they continued to sit in the booth for

some fifteen minutes, each with an open book before him,

when the manager of the store came up, in company with

a police officer, told them that they would not be served,

and twice requested them to leave. Upon their ignoring

such request, the police officer asked them to leave, which

request brought no result other than the query “for what”

from Bouie. The police officer then told them to leave and

that they were under arrest. Thereupon Neal closed his

book and got up ; Bouie did not, and the officer thereupon

caught him by the arm and lifted him out of the seat.

Bouie’s book being still on the table, he was permitted to

get it; and the officer then seized him by the belt and pro

ceeded to march him out of the store, Bouie testified that

12a

Opinion of the Supreme Court of South Carolina

he made no resistance, but only said to the officer when

the latter had hold of his belt, “That’s all right, Sheriff,

I ’ll come on”. The officer testified that Bouie said: “Don’t

hold me, I ’m not going anywhere”, and that after they

had proceeded a few steps he “started pushing back and

said ‘Take your hands off me, you don’t have to hold me.’ ”

The appeal here is based upon four Exceptions of which

Nos. 3 and 4 present, in substance, the contention that ap

pellants’ arrest by the police officer at the instance of the

store manager, and the convictions of trespass that fol

lowed, were in furtherance of an unlawful policy of racial

discrimination and constituted state action in violation of

appellants’ rights under the Fourteenth Amendment. Iden

tical contention was made, considered, and rejected in City

of Greenville v. Peterson, filed November 10, 1961, -----

S. C. ----- , ----- S. E. (2d) ----- ; City of Charleston v.

Mitchell, filed December 13, 1961, —— 8. C. ----- , -----

S. E. (2d)----- and City of Columbia v. Barr, filed Decem

ber 14, 1961,-----S. C .------ , ----- S. E. (2d) ----- , in each

of which was involved a sit-down demonstration, similar

to that disclosed by the uncontradicted evidence here, at

a lunch counter in a place of business privately owned and

operated, as was Eckerd’s in the case at bar. Exceptions

3 and 4 are overruled.

Exceptions 1 and 2 purport to question the sufficiency