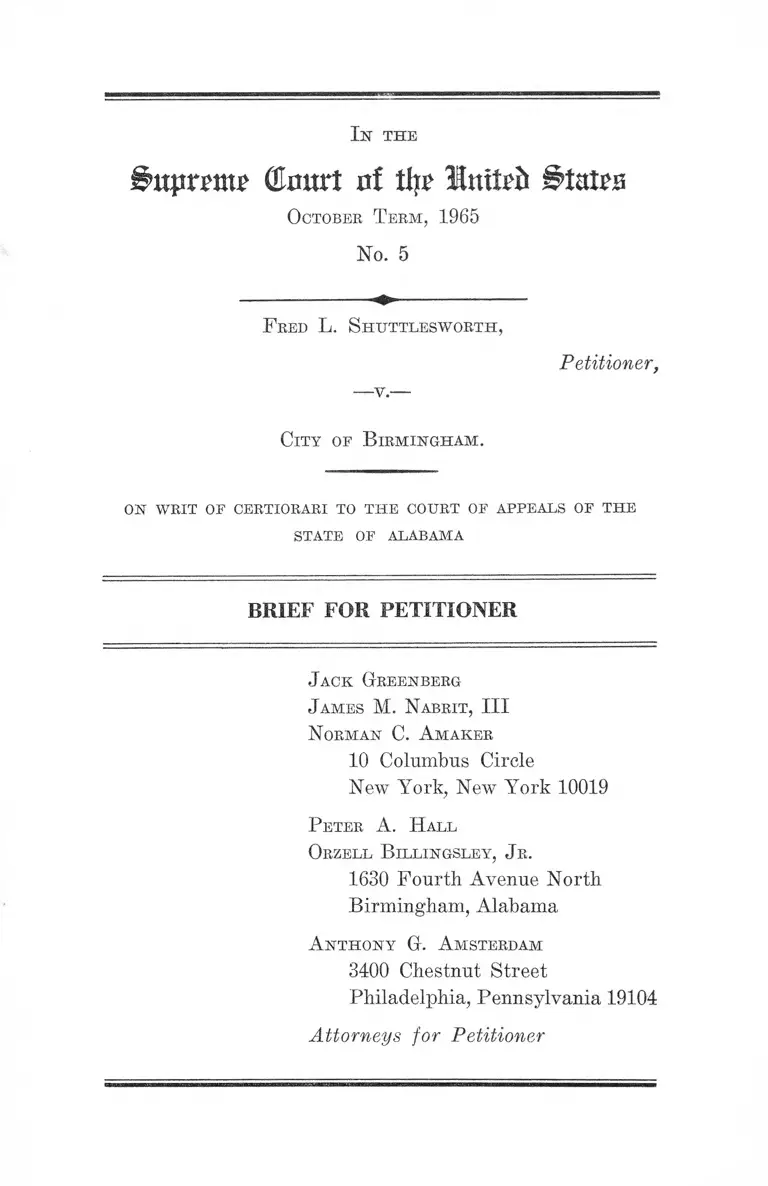

Shuttlesworth v Birmingham AL Brief for Petitioner

Public Court Documents

October 1, 1965

39 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Shuttlesworth v Birmingham AL Brief for Petitioner, 1965. 03ce7448-c49a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/7ba89197-cda5-4da5-8e34-c70a9749fe81/shuttlesworth-v-birmingham-al-brief-for-petitioner. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

I n' the

GJmtrt of % î tatTB

October T erm, 1965

No. 5

F red L. Shuttlesworth,

Petitioner,

City of B irmingham .

ON W R IT OF CERTIORARI TO T H E COURT OF APPEALS OF T H E

STATE OF ALABAM A

BRIEF FOR PETITIONER

Jack Greenberg

James M. N abrit, III

N orman C. A maker

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

.Peter A. H all

Orzell B illingsley, Jr.

1630 Fourth Avenue North

Birmingham, Alabama

A nthony G. A msterdam

3400 Chestnut Street

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104

Attorneys for Petitioner

I N D E X

Opinions Below .................................................................. 1

Jurisdiction ..... 2

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved ..... 2

Questions Presented ............................................... 3

Statement of the Case ........ 4

Summary of Argument ...................................................... 12

A rgument :

I. Since the Verdict Against Petitioner Was

General, His Conviction Must Be Reversed

if Any of the Charges Is Constitutionally

Invalid ................................ 13

II. On Its Face,, and as Applied to Petitioner’s

Conduct, Section 1142’s Proscription of

Standing or Loitering on a Sidewalk After

a Police Order to Move on Is Vague and

Overbroad in Violation of the First and

Fourteenth Amendments ................................ 14

A. The ordinance as written is vague and

overbroad ..... 14

B. The construction of §1142 by the Alabama

courts has not cured its objectionable

vagueness and overbreadth....................... 20

PAGE

PAGE

III. On Its Face, and as Applied to Petitioner’s

Conduct, Section 1142’s Proscription of

Standing, Loitering or Walking on a Side

walk so as to Obstruct Free Passage Thereon.

Is Vague and Overbroad in Violation of the

First and Fourteenth Amendments ...............

IV. Petitioner’s Conviction for Violation of

§1231 Is Supported by No Evidence .............

Conclusion ......................................................................................

Table of Cases

Anderson v. Albany, 321 F. 2d 649 (5th Cir. 1963) .......

Aptheker v. Secretary of State, 378 U. S. 500 (1964) ....

Baggett v. Bullitt, 377 U. S. 360 (1964) .... ..................

Bantam Books, Inc, v. Sullivan, 372 U. S. 58 (1963) ....

Barr v. City of Columbia, 378 U. S. 146 (1964) .......15,

Benson v. City of Norfolk, 163 Va. 1037, 177 S. E. 222

(1934) .... ..........................................................................

Bouie v. City of Columbia, 378 U. S. 347 (1964) ...........

Cantwell v. Connecticut, 310 U. S. 296 (1940) ........ .

Carlson v. California, 310 F. S. 106 (1940) ......... ..... 18,

City of Akron v. Effland, 112 Ohio App. 15, 174 N. E.

2d 285 (1960) ....... ...... ..................................... .............

City of Chariton v. Fitzsimmons, 87 Iowa 226, 54 N. W.

146 (1893) ........ ..................... .....................................

City of Portland v. Goodwin, 187 Ore. 409, 210 P. 2d

577 (1949) ............................... ....... ...... ...........................

City of St. Louis v. Gloner, 210 Mo. 502, 109 S. W. 30

(1908) ...............................................................................

29

29

31

16

24

17

17

30

26

23

15

25

26

27

26

26

City of Tacoma v. Roe, 190 Wash. 444, 68 P. 2d 1028

(1937) ............... ......... .............................-........................ 27

Commonwealth v. Carpenter, 325 Mass. 519, 91 N. E.

2d 666 (1950) ______ _____________ _____ -........ - ..... 18

Commonwealth v. Challis, 8 Pa. Super. 130 (1898) ....... 27

Cox v. Louisiana, 379 U. S. 536 (1965) ......... ..15,16,18,28

Cramp v. Board of Public Instruction, 368 U. S. 278

(1961) _____________________ _____ ____ _____________ 17

Dombrowski v. Pfister, 380 U. S. 479 (1965) ...............17, 24

Dominguez v. City and County of Denver, 147 Colo.

233, 363 P. 2d 661 (1961) .................. ........... ............... 26

Douglas v. Alabama, 380 U. S. 415.................................. 11

Edwards v. South Carolina, 372 TJ. S. 229 (1963) ....... 15

Ex parte Bodkin, 86 Cal. App. 2d 208, 194 P. 2d 588

(1948) .................. - ........ ...................... .. ........................ 27

Ex parte Mittelstaedt, 164 Tex. Grim. 115, 297 S. W.

2d 153 (1957) ..... .................... .......... .......... ................ - 26

Fields v. Fairfield, 375 TJ. S. 248 (1963) ..................... 30

Fields v. South Carolina, 375 U. S. 44 (1963) ............... 25

Garner v. Louisiana, 368 U. S. 157 (1961) ................. 16

Hague v. C. I. O., 307 U. S. 496 (1939) ............... . 15

Harris v. District of Columbia, 1.32 A. 2d 152 (M. C. A.

D. C. 1957), rev’d on other grounds, 251 F. 2d 913

(D. C. Cir. 1958) .......................................... .................. 26

Harris v. District of Columbia, 192 A. 2d 814 (C. A.

D. C. 1963) ...................... ......... ................................... 26

Headley v. Selkowitz, 171 So. 2d 368 (Fla. 1965) ..... . 26

Henry v. City of Rock Hill, 376 H. S. 776 (1964) ........... 25

Henry v. Mississippi, 379 IT. S. 443 (1965) ..... 11

I l l

PAGE

PAGE

In re Bell, 19 Cal. 2d 488, 122 P. 2d 22 (1942) ...............

In re Cregler, 56 Cal. 2d 308, 363 P. 2d 305, 14 Cal.

Rptr. 289 (1961) .................................. ...........................

In re Huddleson, 229 A. C. A. No. 3, 721, 40 Cal. Rptr.

581 (1964) .............................................. .......... ........... .

Kunz v. New York, 340 U. S. 290 (1951) ...................... 15,

Largent v. Texas, 318 U. S. 418 (1943) .................... ......

Lovell v. Griffin, 303 U. S. 444 (1938) ........ .................. 15,

Marsh v. Alabama, 326 U. S. 501 (1946) .................... .

Middlebrooks v. City of Birmingham, ------ Ala. App.

------ , 170 So. 2d 424 (1964), cert, denied, 170 So. 2d

424 (Ala. 1964) ........ ............... .................... ......... 21,26,

N.A.A.C.P. v. Button, 371 U. S. 415 (1963) ...............16,

Niemotko v. Maryland, 340 U. S. 268 (1951) ...... ........ 15,

People v. Bell, 306 N. Y. 110, 115 N. E. 2d 821 (1953) ..

People v. Diaz, 4 N. Y. 2d 469,151 N. E. 2d 871 (1958) ..

People v. Galpern, 259 N. Y. 279, 181 N. E. 572 (1932)

20, 21,

People v. Johnson, 6 N. Y. 2d 549, 161 N. E. 2d 9

(1959) .................... .................... ......................................

People v. Merolla, 9 N. Y. 2d 62, 172 N. E. 2d 541

(1961) ............... ...................................... ........... .............

Phifer v. City of Birmingham, 42 Ala. App. 282, 160

So. 2d 898 (1963), cert, denied, 160 So. 2d 902 (Ala.

1964) ....... ........................................................7,11, 20, 22,

Phillips v. Municipal Court, 24 Cal. App. 2d 453, 75

P. 2d 548 (1938) ..............................................................

25

26

27

25

15

23

15

27

29

25

26

26

25

26

27

30

26

V

Pinkerton v. Verberg, 78 Mich. 573, 44 N. W. 579

(1889) ...................... .................. ...................................... 29

Saia v. New York, 334 U. S. 558 (1948) ................ 15

Schneider v. State, 308 U. S. 147 (1939) ....................... 15

Shelton v. City of Birmingham, 42 Ala. App. 371, 165

So. 2d 912 (1964) .... ................... ..................... .....20,21,22

Shuttlesworth v. City of Birmingham, 42 Ala. App.

296, 161 So. 2d 796 (1964), cert, denied, 161 So.

2d 799 .......... ............. .......... ...... .... .......................... ....20,22

Smith v. California, 361 U. S. 147 (1959) ...................... 17

Smith v. City of Birmingham, 42 Ala. App. 467, 168

So. 2d 35 (1964) ......... ........ ....................... .................... 21

Soles v. City of Vidalia, 92 Ga. App. 839, 90 S. E. 2d

249 (1955) ....... ............................................................. 26

Speiser v. Randall, 357 U. S. 513 (1958) ....................... 24

State v. Caez, 81 N. J. Super. 315, 195 A. 2d 496

(1963) .................... ........ .... .................... ........................ 26

State v. Hunter, 106 N. C. 796, 11 S. E. 366 (1890) ....... 26

State v. Salerno, 27 N. J. 289, 142 A. 2d 636 (1958) .... 26

State v. Starr, 57 Ariz. 270, 113 P. 2d 356 (1941) ....... 26

State v. Sugarman, 126 Minn. 477, 148 N. W. 466

(1914) ....... ........................................ ......................... 27

State v. Taylor, 38 N. J. Super. 6, 118 A. 2d 36 (1955) 21

Staub v. Baxley, 355 U. S. 313 (1958) .......................15,23

Stromberg v. California, 283 U. S. 359 (1931) ..... 14

Taylor v. Louisiana, 370 U. S. 154 (1962) ................... 15,30

Territory of Hawaii v. Anduha, 48 F. 2d 171 (9th Cir.

1931) ................ ............ .................................................. 26, 28

Thistlewood v. Trial Magistrate for Ocean City, 236

Md. 548, 204 A. 2d 688 (1964) ....................................... 27

Thomas v. Collins, 323 U. S. 516 (1945) .......................... 14

PAGE

VI

Thompson v. City of Louisville, 362 U. S. 199 (1960)

15,18, 30

Thornhill v. Alabama, 310 U. S. 88 (1940) ...........16,17, 25

Tinsley v. City of Richmond, 202 Ya. 707, 119 S. E. 2d

488 (1961), app. dism’d, 368 U. S. 18 (1951) ....22, 26, 28, 29

Tot v. United States, 319 U. S. 463 (1943) -------- ------- 24

Tucker v. Texas, 326 U. S. 517 (1946) .......................... 15

United States v. National Dairy Prods. Co., 372 U. S.

29 (1963) ........................................................................17,29

Village of Deer Park v. Schuster, 16 Ohio Ops. 485,

30 Ohio L. Abs. 466 (Ct. Com. Pis. 1940) ............... 26

Whaley v. Cavanagh, 237 F. Supp. 900 (S. D. Cal.

1963), aff’d per curiam on opinion below, 341 F. 2d

295 (9th Cir. 1965) .......................................................... 27

Williams v. North Carolina, 317 U. S. 287 (1942) ..... . 14

Wright v. Georgia, 373 U. S. 284 (1963) ....................... 15

Statutes

Birmingham General City Code, §1142, as amended by

Ordinance No. 1436-F ................................ 2,10,11,12,13,

14,17,18,19, 20, 21,

22, 23, 24, 25, 27, 29

PAGE

Birmingham General City Code, §1231 .............3,10,11,13,

14, 20, 29, 30

28 United States Code, §1257(3) ...................................... 2

Other Authority

Note, 109 U. Pa. L. Rev. 67 (1960) 16

I n t h e

Bnptmt OInurt of tip United States

October T erm, 1965

No. 5

F red L. Shttttlesworth,

Petitioner,

City of B irmingham .

ON W R IT OF CERTIORARI TO T H E COURT OF APPEALS OF T H E

STATE OF ALABAM A

BRIEF FOR PETITIONER

Opinions Below

The orders of the Supreme Court of Alabama denying

the petition for writ of certiorari to the Court of Appeals

(R. 146) and denying a rehearing (E. 147) are reported at

276 Ala. 707, 161 So. 2d 799 (1964). The opinion of the

Court of Appeals (E. 137-41) is reported at 42 Ala. App.

296, 161 So. 2d 796 (1963). The order denying a rehearing

(E. 141) is noted at 42 Ala. App. 296, 161 So. 2d 796 (1964).

The judgment and sentences of the Tenth Judicial Circuit

Court of Alabama are unreported (E. 10-12). The judg

ment and sentences of the Eecorder’s Court of the City

of Birmingham are unreported (R. 2).

2

Jurisdiction

The final judgment of the Court of Appeals of Alabama,

which is the order denying a rehearing, was entered on

January 7, 1964 (E, 141). A petition for certiorari filed

in the Supreme Court of Alabama was denied on February

20, 1964 (E. 146) and an application for rehearing was

denied March 26, 1964 (E. 147). On June 19, 1964, by

order of Justice Black, the time within which to file a

petition for writ of certiorari was extended to August 23,

1964 (E. 148). The petition was filed August 21, 1964 and

was granted March 1, 1965 (E. 149).

The jurisdiction of this Court is invoked pursuant to 28

U. S. C. §1257(3), petitioner having asserted below, and

asserting here, deprivation of rights, privileges and im

munities secured by the Constitution of the United States.

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved

1. This case involves Section 1 of the Fourteenth Amend

ment to the Constitution of the United States.

2. This case also involves:

Section 1142 of the General City Code of B irming

ham as A mended by Ordinance N o. 1436-F:

Streets and Sidewalks to be Kept Open For Free Pas

sage.

Any person who shall obstruct any street or sidewalk

or part thereof in any manner not permitted by this

code or other ordinance of the City with any animal or

vehicle, or with boxes or barrels, glass, trash, rubbish

3

or display of wares, merchandise or sidewalk signs, or

other like things, so as to obstruct the free passage of

persons on such streets or sidewalks or any part there

of, or who shall assemble a crowd or hold a public meet

ing in any street without a permit, shall, on conviction,

be punished as provided in Section 4.

It shall be unlawful for any person or any number of

persons to so stand, loiter or walk upon any street or

sidewalk in the City as to obstruct free passage over,

on or along said street or sidewalk. It shall also be un

lawful for any person to stand or loiter upon any street

or sidewalk of the City after having been requested by

any police officer to move on.

Section 1231 of the General City Code of B irming

ham :

Obedience to Police.

It shall be unlawful for any person to refuse or fail

to comply with any lawful order, signal or direction

of a police officer.

Questions Presented

1. Whether, on its face and as applied to one who ques

tions a policeman’s order, an ordinance making it an of

fense to stand or loiter on any sidewalk in the city after

having been requested by any policeman to move on is

vague and overbroad in violation of the First and Four

teenth Amendments.

2. Whether, on its face and as applied to one who stands

conversing on a sidewalk within a group of ten or twelve

4

persons—the entire group occupying one half the side

walk—an ordinance making it an offense to so stand, loiter

or walk on any sidewalk in the city as to obstruct free pas

sage oyer, on or along the sidewalk is vague and over

broad in violation of the First and Fourteenth Amendments.

3. Whether, under an ordinance which has been con

strued as making it an offense to refuse or fail to comply

with an order of a policeman relating to vehicular traffic,

there is any evidence consistent with due process of law

to sustain petitioner’s conviction, where the only police

order shown by the prosecution is a policeman’s order

directed to a group of pedestrians standing on a sidewalk,

commanding them to disperse.

Statement of the Case

On April 4, 1962, the petitioner, Reverend Fred L. Shut-

tlesworth, was arrested by four or five police officers1 at

the corner of Second Avenue and 19th Street North in the

City of Birmingham, Alabama. This case challenges his

convictions for loitering and noncompliance with a police

order on that occasion, pursuant to which he has been sen

tenced to 180 days imprisonment at hard labor, and an ad

ditional 61 days imprisonment at hard labor in default of

1 Technically, Patrolman Byars made the arrest and denied that

other officers assisted him (R. 30). But Officers Hallman and Davis

testified that Byars beckoned them to the scene and that they

arrived prior to the arrest (R. 59, 64, 74). Officer Renshaw,

who had also come up behind Byars, regarded himself as having

assisted by his presence in the arrest (R. 48). Officer Allred was

a short distance off at the time (R. 66-67).

5

fine and costs (R. 10-11). The following statement of the

circumstances of his arrest is taken from the testimony of

the arresting officers unless otherwise indicated; where

based on uncontradicted testimony of defense witnesses,

that source is noted.

On April 4, 1962, the Negro citizens of Birmingham were

engaged in a boycott of the downtown department stores

(K. 89, 122: uncontradicted testimony of defense witness

Armstrong and of petitioner). Word of the boycott was

known to the police (R. 43-44, 63, 78), including Patrolman

Byars (R. 24-25). At about 10:30 a.m. Byars observed a

group of four or six persons, including petitioner, walking

south on the west sidewalk of 19th Street toward the inter

section of 19th Street and Second Avenue (R. 16, 25, 35).2

Newberry’s Department Store is located at the northwest

corner of that intersection (R. 17), having a front entrance

on the corner (R. 17, 26). Byars entered a rear entrance

of Newberry’s, went through the store to the front entrance,

and stood inside the entrance observing the corner (R. 16-17,

18, 26). On the corner, he saw a group of ten or twelve per

sons (R. 17, 27, 38, 138)3 “ all congregated in one area” (R.

17), “ [sjtanding and listening and talking” (R. 17). Peti

tioner Shuttlesworth was among them (R. 17) and seems

to have been at the center of the conversation (R. 38).

2 Byars conceded that the group was not obstructing traffic and

was not violating any ordinance at this time (R. 25-26).

3 When Officer Renshaw arrived after Byars had accosted the

group, Renshaw estimated that there were eight or ten or twelve

persons with petitioner (R. 40, 49). Officer Hallman, who seems

to have observed the group at about the same moment, estimated

that there were five or six persons with petitioner and petitioner’s

co-defendant below, Reverend James S. Phifer (R. 59), or five or

six in all (R. 60). Officer Allred guessed the size of the group

at the time as ten or fifteen or twenty (R. 71). Officer Davis

put it at ten or twelve (R. 74).

6

Byars observed the group “ for a minute to a minute and a

half while they stood” (R. 18; see R. 26). He then left the

store and told the group to move on and clear the sidewalk

(R. 18, 138). Some but not all of the group began to move

away (R. 18, 138). Byars repeated his command and peti

tioner asked: “ You mean to say we can’t stand here on

the sidewalk?” (R. 18; cf. R. 38). At this moment, motor

cycle patrolman Renshaw arrived on the scene and came up

behind Patrolman Byars (R. 41,47-48, 51). Officers Hallman

and Davis, on a motion from Byars, came over from the

southeast corner of the intersection (R. 59, 64, 74). Byars

“ said nothing in return. [He] . . . only hesitated again

for a short time and informed them for the third and last

time [he] . . . was informing them they would have to

move and clear the sidewalk or else they would be placed

under arrest for obstructing the sidewalk. . . . ” (R. 18). By

now, all persons save petitioner had dispersed (R. 28, 35,

60, 138-139). Petitioner repeated his inquiry whether the

officer meant that they could not stand in front of the store

(R. 18).4 Byars told petitioner he was under arrest (R. 18).

Petitioner said: “Well I will go into the store” (R. 18, 41,

139), and walked to Newberry’s, where Byars followed him

through the door and arrested him just inside (R. 18, 139).

Petitioner offered no resistance and gave “ [n]o trouble”

(R. 30; see R. 55).5 Byars estimated the time during which

4 Byars’ testimony is not consistent on what, if anything, peti

tioner said at this time. At another point, Byars testified that

petitioner’s second question was: “Do you mean to tell me we

can’t go into the store?” (R. 20). Officer Eenshaw testified that

at this stage of the conversation, petitioner said: “We are just

standing here on the sidewalk” (R. 41).

5 Byars then took petitioner to the west curb of 19th Street

just north of Second Avenue to await transportation to jail.

Reverend James S. Phifer, one of petitioner’s companions and

7

Ms three orders to disperse were given and petitioner ar

rested as one and one half minutes (E. 32).

There is considerable confusion in the officer’s testimony

as to the location of the group of ten or twelve persons

standing on the corner outside Newberry’s and as to how

much, if at all, pedestrian traffic was impeded by their

presence. Byars placed the group on the corner “ in the

western half of the western cross walk . . . ” (E. 17)6 but

later testified they were “ [j]ust east and north of the [east-

west 19th Street] cross walk on the sidewalk” (E. 21). Een-

shaw placed them “ at the curb on the 2nd Avenue side at

the cross walk that crosses over 2nd Avenue” (E. 42), i.e.,

at the north-south crosswalk. Concerning the density of

pedestrian traffic, Byars testified “ There was some people

moving back and forth” (E. 17). Traffic was “normal for a

Wednesday at that particular time of day” (E. 20); Byars

estimated that 75 to 100 pedestrians per minute were pass

ing through the intersection, in all four directions, on all

four corners (E. 30-31; see also E. 57). He said that: “ On

some occasions people who were walking in an easterly

direction on the north side of 2nd Avenue had to go into the

his co-defendant in the present trial, approached and began talking

to petitioner. Byars twice told him that he could not talk to

Shuttlesworth, who was a prisoner; and when Phifer continued

to talk to petitioner, Byars arrested Phifer as well (R. 19, 32-33).

Phifer’s conviction of loitering and noncompliance with a police

order after joint trial with petitioner below was reversed by the

Alabama Court of Appeals, which found the evidence insufficient

to sustain either charge. Phifer v. City of Birmingham, 42 Ala.

App. 282, 160 So. 2d 898 (1963), cert, denied, 160 So. 2d 902

(Ala. 1964).

6 When Byars says “ in the . . . cross walk” he means on the

sidewalk in front of the crosswalk. The record is clear that none

of the group were in the street at any time; Byars explicitly

testified that they were all on the sidewalk (R. 27).

8

street to get around the people who were standing there”

(R. 17). Byars saw some people step off the curb (R. 20)

into Second Avenue (R. 39), and said that “ Due to the peo

ple moving in an westerly direction along 2nd Avenue they

would have had to have waited until those people got by

or either elect to go into the street to pass the group of

people standing there” (R. 20; see R. 138). Again, the

persons standing on the corner “ were blocking half of the

sidewalk causing the people walking east [“ Along 2nd

Avenue” ] to go into the street around them” (R. 28). How

ever, on cross examination, Byars testified that the per

sons on the corner did not block the east-west crosswalk

at all (R. 22)7 and that they left more than half of the

north-south crosswalk free (R. 22). Officer Renshaw esti

mated that the group occupied “ about half” the sidewalk

(R. 41). They “ had the crosswalk [sic] approximately half

blocked” (R. 50). Actual disruption of pedestrian traffic

must have been slight, for Officer Hallman, who was as

signed to work traffic at the intersection (R. 61) and who

was standing on the southeast corner of Second Avenue and

19th Street North (R. 59), saw the group standing on the

northwest corner but took no note of them as a source of

concern prior to Patrolman Byars’ arrival on the scene

(R. 62-63).

Although Byars testified that he had read of prior arrests

of petitioner Shuttlesworth (R. 22-23) and had seen peti

tioner’s photograph and seen him on television (R. 23)—

and although Officer Renshaw conceded that petitioner was

a notorious person in Birmingham by reason of his civil

7 Yet Byars testified lie told the group to move on in order to

allow free passage for pedestrians east and west (R. 18).

9

rights activities (R. 45-46; see also R. 77-78)8—Byars in

sisted that he was not familiar with petitioner’s face at the

time of the arrest (R. 28, 29; cf. R. 16). Byars said he

“ didn’t pay particular notice to the race” of the persons in

the group on the corner (R. 27) , and at trial did not “ know

what color they were” (R. 36). He identified them as a group

because “ They were all standing and not moving” (R. 36).

Officer Renshaw acknowledged that the group was all Negro

(R. 49), and Officer Davis described them as “ a group of

colored people” (R. 73). The trial court permitted defense

testimony that, because of the boycott, there were few other

Negroes in the area at the time, making petitioner’s group

conspicuous (R. 89, 122: uncontradicted testimony of de

fense witness Armstrong and of petitioner). Other attempts

by petitioner to show that his arrest and prosecution were

racial harassment were disallowed by the trial court on

prosecutor’s objections (R. 115-116).

Petitioner’s version of the events of April 4, 1962, sup

ported by his testimony and that of his co-defendant Phifer

and four other witnesses, was entirely irreconcilable with

that of the arresting officers which the state courts credited.

Petitioner with his five companions was walking south on

19th Street; slowed at the intersection of Second Avenue

for a traffic light; was immediately accosted by Patrolman

Byars and ordered to move on (Patrolman Byars, however,

stationed himself directly in petitioner’s path so that peti

tioner could not continue in the direction in which he had

been walking) ; attempted to move on by going into New

berry’s; and was pursued and arrested (R. 80-84, 87-89, 90-

94, 100-104, 106-108, 111-112).

8 Renshaw admitted knowing petitioner by sight (R. 40) and

recognizing him on the morning of April 4 (R. 48).

10

April 5, 1962, petitioner was tried and convicted in the

Recorder’s Court of the City of Birmingham of loitering

and noncompliance with a police order, and was sentenced to

180 days at hard labor, $100 fine and costs (R. 1-2). He

appealed for trial de novo in the Circuit Court of the Tenth

Judicial District, and was there charged by complaint in

two counts: One, that he “ did stand, loiter or walk upon a

street or sidewalk within and among a group of other per

sons so as to obstruct free passage over, on or along said

street or sidewalk . . . or did while in said group stand or

loiter upon said street or sidewalk after having been re

quested by a police officer to move on, contrary to . . . Sec

tion 1142 of the General City Code . . . , as amended . . . ”

(R. 3 ); Two, that he “ did refuse to comply with a lawful

order, signal or direction of a police officer, contrary to

. . . Section 1231 of the General City Code . . . ” (R. 3).

By motion to quash and demurrers timely filed, petitioner

attacked these charges on the grounds that the ordinances

under which they were laid were unconstitutional on their

faces and as applied to his conduct, by force of the First

and Fourteenth Amendments to the Constitution and be

cause the charges and ordinances were vague and over

broad in contravention of those Amendments (R. 4-6). At

the conclusion of the prosecution’s case, he moved to exclude

the testimony and for judgment on the grounds that the

charges were supported by “absolutely no evidence” and

that the conduct for which he was prosecuted was pro

tected by the First and Fourteenth Amendments (R. 7).

The Circuit Court overruled all these objections, found the'

defendant “ guilty as charged in the Complaint” (R. 10),

sentenced him, to 180 days at hard labor and to another 61

days at hard labor in default of fine and costs, and over

ruled his timely motion for new trial (R. 8-9) renewing all

1 1

Ms federal contentions and claiming error in the exclu

sion of testimony intended to show that the prosecution was

racial harassment (R. 10-11). The Alabama Court of Ap

peals affirmed the conviction and sentence (R. 136-137),

expressly rejecting petitioner’s federal attack on the ordi

nances by reference to Phifer v. City of Birmingham, 42 Ala.

App. 282, 160 So. 2d 898 (1963), cert, denied, 160 So. 2d 902

(Ala. 1964),9 holding the evidence sufficient to support the

verdict, and rejecting petitioner’s claim of error in the ex

clusion of testimony (R. 139-141). Timely application for

rehearing was denied by that court (R. 141); the Alabama

Supreme Court denied timely applications for certiorari

and for rehearing (R. 146-147) preserving petitioner’s fed

eral contentions (R. 144-145).

9 In Phifer, the Alabama Court of Appeals sustained the over

ruling of a motion to quash and demurrers by petitioner Shuttles-

worth’s co-defendant below, these documents being identical to

those filed on behalf of Shuttlesworth. Phifer’s constitutional

attack on Section 1142, the loitering ordinance, was rejected on

the merits; Phifer’s challenge to Section 1231 was not reached,

because “While the demurrer in its caption is directed to the

complaint ‘and to each and every count thereof, separately and

severally,’ it is really interposed to the two counts of the com

plaint jointly.” 42 Ala. App. at ------ , 160 So. 2d at 900. What

ever the force under state law of this esoteric ruling that a

paper expressly captioned “several” is to be deemed “joint,” it is

clear that the ground is insufficient to bar this court’s review on

the merits of the attack on Section 1231. Any “objection which

is ample and timely to bring the alleged federal error to the

attention of the trial court and enable it to take appropriate

corrective action is sufficient to serve legitimate state interests,

and therefore sufficient to preserve the claim for review here.”

Douglas v. Alabama, 380 U. S. 415, 422, see Henry v. Mississippi,

379 U. S. 443 (1965). In any event, the matter is immaterial

because petitioner’s attack on Section 1142 is dispositive of the

case. See pp. 13-14 infra.

12

Summary of Argument

I. Petitioner having been charged by complaint with

three distinct offenses, and having been found “ guilty as

charged in the Complaint,” is entitled to have his convic

tion reversed by this Court if any one of the charges is

constitutionally invalid.

II. Birmingham Code §1142, insofar as it makes it un

lawful to stand or loiter on any sidewalk of the city after

having been requested by a police officer to move on, is

vague and overbroad and hence unconstitutional under the

First and Fourteenth Amendments. As written, the ordi

nance gives any policeman absolutely arbitrary power to

order a citizen—including any citizen who may be exercis

ing his rights of free expression to picket, address a crowd,

or distribute a handbill—off the streets; and subjects the

citizen to severe criminal penalties if he pauses some in

definite period of time to question the policeman’s order.

Construction of the section by the Alabama courts so as to

make unlawful only disobedience of a policeman’s order

addressed to one who loiters so as to obstruct free passage

on the sidewalks cannot validate petitioner’s conviction

because (A) this narrowing construction post-dated his

alleged violations and his conviction; (B) the Alabama deci

sions impermissibly throw the burden of proof on a defen

dant to disprove that he was loitering so as to obstruct

free passage; and (C) a prohibition of loitering so as to

obstruct free passage—lacking any requirement of mens

rea or of actual obstruction of pedestrians—is itself un

constitutionally vague and overbroad.

III. Birmingham Code §1142, insofar as it makes it un

lawful to so stand, loiter, or walk on any sidewalk in the

13

city as to obstruct free passage on the sidewalk, is simi

larly vague and overbroad,

IV. Birmingham Code §1231, making it unlawful to re

fuse to comply with a lawful police order, has been con

strued by the Alabama Court of Appeals as applying only

to police orders relating to vehicular traffic. Conviction of

petitioner under the ordinance for failing to obey a police

order commanding a group of pedestrians on a sidewalk

to move on entirely lacks evidentiary support.

A R G U M E N T

I.

Since the Verdict Against Petitioner Was General, His

Conviction Must Be Reversed if Any of the Charges Is

Constitutionally Invalid.

The two-count complaint against petitioner charged in its

first count that he did stand, loiter or walk on a street ox-

sidewalk in a group of persons so as to obstruct free pas

sage over the street or sidewalk, or did loiter on the street

or sidewalk within the group after a police request to move

on. This charge is framed upon the two disjunctive sen

tences of the second paragraph of Birmingham City Code

§1142, as amended, pp. 2-3 supra, making it unlawful

for any person or number of persons “ to so stand, loiter ox-

walk upon any street or sidewalk in the city as to obstruct

free passage over, on or along said street or sidewalk” and

making it “ also . . . unlawful for any person to stand or

loiter upon any street or sidewalk of the city after having

been requested by any police officer to move on.” In its

second count, the complaint charged that petitioner did

14

refuse to comply with a lawful police order, in violation of

Birmingham City Code §1231, making it unlawful “ to re

fuse or fail to comply with any lawful order, signal or

direction of a police officer.” Since petitioner was found by

the Circuit Court “ guilty as charged in the Complaint,”

familiar principles require that the conviction be reversed

if any of the three offenses described in sections 1142 and

1231 are constitutionally vulnerable. Stromberg v. Cali

fornia, 283 U. S. 359, 367-368 (1931); Williams v. North

Carolina, 317 U. S. 287, 291-293 (1942); Thomas v. Collins,

323 IT. S. 516, 529 (1945).

II.

On Its Face, and as Applied to Petitioner’s Conduct,

Section 1142’s Proscription of Standing or Loitering on

a Sidewalk After a Police Order to Move on Is Vague and

Overbroad in Violation of the First and Fourteenth

Amendments.

A. The ordinance as ivritten is vague and overbroad.

Understood as it is plainly written, Birmingham Code

§1142 prohibits any loitering or standing on a sidewalk

after a police order to move on. The word “ also” is used

to make clear that this is an offense distinct from obstruc

tive loitering. To be guilty of it, a defendant need not have

loitered so as to obstruct pedestrian traffic prior to the

policeman’s order, nor after the order. The order itself

is not required in express terms to be lawful. Compare

§1231, p. 3 supra. The circumstances under which an

order to move on may be made by a policeman are in no

way defined or restricted. The ordinance simply puts a

citizen’s right to be on the sidewalks of Birmingham in

the unfettered discretion of the police.

Such an ordinance is patently unconstitutional under the

decisions of this Court. Among the persons falling within

its broad and undifferentiated grant of regulatory power

to the police are classes of persons exercising their First-

Fourteenth Amendment freedoms of expression in many

classic forms: handbill distributors, soapbox speakers,

peaceful demonstrators, religious evangelists requesting

audience of passers-by. That such persons may not be

denied the use of the streets by order of the police in a

policeman’s unconfined discretion is settled. Lovell v. Grif

fin, 303 U. 8. 444 (1938); Kunz v. New York, 340 U. S. 290

(1951); Cox v. Louisiana, 379 U. S. 536 (1965); Cantwell

v. Connecticut, 310 U. S. 296 (1940). And see Hague v.

C. I. O., 307 U. S. 496 (1939); Schneider v. State, 308 U. S.

147 (1939) (Schneider’s case); Largent v. Texas, 318 U. S.

418 (1943); Marshy. Alabama, 326 U. S. 501 (1946); Tucker

v. Texas, 326 U. S. 517 (1946); Saia v. New York, 334 U. S.

558 (1948); Niemotko v. Maryland, 340 U. S. 268 (1951);

Staub v. Baxley, 355 U. S. 313 (1958).

So the ordinance cannot constitutionally mean what it

purports to say. It cannot constitute the police the censors

of the sidewalks in violation of the cited decisions. It can

not constrain a citizen to obey a police order whether law

ful or unlawful, because “ one cannot be punished for fail

ing to obey the command of an officer if that command is

itself violative of the Constitution.” Wright v. Georgia,

373 U. S. 284, 291-292 (1963). See Taylor v. Ijouisiana, 370

U. S. 154 (1962); Edwards v. South Carolina, 372 U. 8.

229 (1963); cf. Thompson v. City of Louisville, 362 U. S.

199, 206 (1960); Barr v. City of Columbia, 378 U. S. 146,

150 (1964).

But if the ordinance cannot condemn all of the conduct

which on its face it appears to condemn, what conduct is

16

in fact prohibited by it? When does it authorize an officer

to issue orders, and when does it oblige a citizen to obey

them? If it be assumed that the ordinance requires obedi

ence only to lawful orders, and that it empowers a police

man to command citizens to move on only when he can

constitutionally do so, the effect of the regulation is to make

the citizen guess under threat of criminal penalty the

boundaries of his constitutional freedom to use the streets.

That is, as one Circuit Court has aptly put it, “ a difficult

question which must necessarily be dependent upon the

facts of the particular case,” Anderson v. Albany, 321 F.

2d 649, 657 (5th Cir. 1963); see Cox v. Louisiana, 379 U. S.

536, 554-555 (1965), and an ordinance which makes this

uncertain constitutional boundary the line of criminality

is obnoxious to all of the objections which have caused this

Court to void numerous statutes and ordinances which en

croached overbroadly on constitutionally protected conduct.

First, by reason of the obscurity of the constitutional

boundary itself, the ordinance gives no fair notice, “ no

warning as to what may fairly be deemed to be within its

compass.” Mr. Justice Harlan, concurring, in Garner v.

Louisiana, 368 U. S. 157, 185, 207 (1961); see Note, 109

U. Pa. L. Eev. 67, 76 (1960), and authorities cited in foot

note 51. Second, the ordinance remains “ susceptible of

sweeping and improper application,” N.A.A.C.P. v. Button,

371 U. S. 415, 433 (1963), furnishing in its overbreadth a

convenient tool for “harsh and discriminatory enforcement

by prosecuting officials, against particular groups deemed

to merit their displeasure,” Thornhill v. Alabama, 310 IT. S.

88, 97-98 (1940), and inviting arbitrary, autocratic and

harassing uses by the police. “ It is enough that a vague

and broad statute lends itself to selective enforcement

against unpopular causes.” N.A.A.C.P. v. Button, supra,

17

at 435. Finally, the threat of serious penalties—here nearly

eight months at hard labor—for any citizen who, in the

service of an unpopular cause, guesses wrongly the bound

aries of his constitutional freedoms (or is unable to per

suade a state trial judge to discredit the testimony of police

men that he guessed them wrongly), serves effectively to

coerce the citizen to obey even lawless police orders and

surrender through fear his constitutional rights to the free

use of the streets. See Thornhill v. Alabama, supra, at

97-98; Smith v. California, 361 U. S. 147, 150-151 (1959);

Cramp v. Board of Public Instruction, 368 U. S. 278, 286-

288 (1961); Bantam Books, Inc. v. Sullivan, 372 U. S. 58,

66-70 (1963); Baggett v. Bullitt, 377 IT. S. 360, 378-379

(1964); Dombrowski v. Pfister, 380 U. S. 479, 494 (1965) ;

and see United States v. National Dairy Prods. Co., 372

IT. S. 29, 36 (1963) (dictum). Plainly an ordinance so

written is bad on its face.

Moreover, this ordinance is susceptible of the same criti

cisms in another of its operative elements. Section 1142

makes it unlawful to “ stand or loiter” on the street after

having been told to move on. In this case petitioner was

found guilty of standing or loitering on evidence that, dur

ing less than a minute and a half, he persisted in asking the

officer whether the officer seriously meant that he could not

stand on the sidewalk in front of Newberry’s. No scienter

or mens rea, no intention to disobey or flout the officer’s

order, was shown; apparently none is required by the ordi

nance as construed by the Alabama courts. Whatever ob

struction to pedestrians might at any time have existed was

now gone; all petitioner’s companions had dispersed; and,

with the explicit concerns of the officer’s initial order satis

fied, petitioner stood where he was for the ostensible pur

pose of inquiring what the officer commanded, and perhaps

18

of verbally contesting his authority to make the command.

The officer did not reply to petitioner’s question or other

wise explain himself; he merely repeated his command—•

whose justification had faded or was fading; and petitioner

repeated his question. If evidence of such conduct is con

stitutionally sufficient to support conviction under §1142,

see Thompson v. City of Louisville, 362 U. S. 199 (1960),

the ordinance has been construed in such a way as to jeop

ardize any citizen who pauses to question an officer’s order.

At some unascertainable point his delay in complying

causes him to “ stand or loiter” and thereby makes his con

duct criminal. Here again the vice of the ordinance is that

it cannot mean what it purportedly says, see Thompson v.

City of Louisville, supra, at 206, and no principle to limit

what it purportedly says sufficiently intelligible to accord

fair notice and assure non-arbitrary application appears.10

When this deficiency is coupled with the vagueness of the

ordinance as to the circumstances under which a policeman

may make an order to move on, §1142 becomes little more

than a snare. It is nigh impossible for the citizen to ascer

tain the propriety of the policeman’s command, and he who

stops to question may find himself a misdemeanant.11

10 Cf. Commonwealth v. Carpenter, 325 Mass. 519, 91 N. B. 2d

666 (1950), voiding an ordinance which made it unlawful to

“willfully and unreasonably saunter or loiter for more than seven

minutes after being directed by a police officer to move on.”

11 In Cox v. Louisiana, 379 U. S. 536, 551 (1965), this Court

said that a statute punishing one who “ fails or refuses to disperse

and move on” when ordered to do so by an officer would be suf

ficiently specific if the conditions under which the officer’s order

might issue were narrowly restricted. Here they are unrestricted,

as in Cox; and the language “stand or loiter,” construed without

a requirement of intent to resist the officer, is considerably more

vague than “fails or refuses to disperse.” See Carlson v. California,

310 U. S. 106, 112 (1940).

19

On the present record, the potential of §1142 for unfair,

arbitrary and discriminatory application has been fully re

alized. Had Newberry’s windows presented a fetching

Easter display, and had a crowd of attracted persons

paused to look, filling half the sidewalk for a minute and a

half, it is inconceivable that Patrolman Byars would have

commanded them to move on. Had such a command been

made, and—while the crowd was dispersing—had one such

window-shopper asked Byars did Byars really mean he

could not look in the window, it is inconceivable that he

would have been arrested and charged, and phantasma

goric that he would have been convicted and sentenced to

almost eight months at hard labor. Had a Newberry’s de

livery man blocked the same half a sidewalk for the same

ninety seconds, or had he stopped to complain to an officer

when told to move on, no sane mind could imagine that he

would be found in petitioner Shuttlesworth’s posture today.

Yet if Shuttlesworth was warned that his position was dif

ferent from that of the window-shopper or delivery man,

it was only because Shuttlesworth is a Negro and a “ no

torious” civil rights leader in Birmingham, Alabama. And

however convincing to a state court may be Patrolman

Byars’ protestations that he did not recognize Shuttlesworth

when he proceeded through Newberry’s to observe, com

mand and then arrest him, any non-racial explanation for

the ultimate result in this prosecution is delusive. The very

fact that, under this Court’s ordinary practice, Byars’ tes

timony must escape strict review here is the strongest rea

son for invalidation of the vague ordinance under which

such a conviction could occur.

20

B. The construction of §1142 by the Alabama courts has not

cured its objectionable vagueness and overbreadth.

Petitioner’s ease and that of his co-defendant below,

Reverend James S. Phifer, were the first involving the

ordinance to reach the Alabama appellate courts. In neither

case did the Alabama Court of Appeals attempt any limit

ing construction of §1142. Phifer v. City of Birmingham,

42 Ala. App. 282, 160 So. 2d 898 (1963), cert, denied, 160

So. 2d 902 (Ala. 1964) ;12 Shuttlesworth v. City of Birming

ham, 42 Ala. App. 296, 161 So. 2d 796 (1964), cert, denied,

161 So. 2d 799 (Ala.), R. 137-141. The appeal in Shelton

v. City of Birmingham, 42 Ala. App. 371, 165 So. 2d 912

(1964), involved Birmingham Code §1231, p. 3 supra

(noncompliance with a police order); affirming a civil rights

demonstrator’s conviction under that ordinance, the Court

of Appeals adopted the rule that “ the failure to comply

with a police officer’s order to ‘Move on,’ ‘can be justified

only where the circumstances show conclusively that the

police officer’s direction was purely arbitrary and was not

calculated in any way to promote the public order.’ ” 42

Ala. App. at ------ , 165 So. 2d at 913.13 Judge Cates dis

12 Phifer’s conviction was reversed for want of evidence that

he had loitered or stood on the sidewalk after being told to move

on. Since the record was clear that everyone save Shuttlesworth

had dispersed at Byars’ order, and that Byars himself did not

believe Phifer had failed to comply with his order, this decision

is uninformative as to the meaning of §1142. In sustaining the

ordinance against Phifer’s claim that it was facially unconstitu

tional, the Court of Appeals characterized it as a traffic regula

tion, but this characterization says nothing about the incidence

or operative elements of §1142. The cases cited by the court as

involving “similar” ordinances, 42 Ala. App. at —— , 160 So. 2d

at 900, in fact involve several different sorts of regulations.

13 The court quotes People v. Galpern, 259 N. Y. 279, 181 N. B.

572 (1932), and cites State v. Taylor, 38 N. J. Super. 6, 118

21

agreed on tins latter point. Smith v. City of Birmingham,

42 Ala. App. 467, 168 So. 2d 35 (1964), and Middlebrooks

v. City of Birmingham, —■— Ala. App. ------ , 170 So. 2d

424 (1964), cert, denied, 170 So. 2d 427 (Ala. 1964), applied

the rule of Shelton to Birmingham Code §1142, with Judge

Cates still objecting that that rule impermissibly required

a defendant “ to come into court and disprove the police

man’s case.” Middlebrooks v. City of Birmingham, supra,

------ - Ala. App. at ------ , n. 3, 170 So. 2d at 426 n. 3. In

the Smith opinion, the court in an extended footnote first

announced the view that §1142 was directed at loitering so

as to obstruct the streets or sidewalks; the implication of

the footnote, not altogether clear, is that the sort of order

envisioned by §1142, following which one may not stand or

loiter, is an order directed to an individual who is previ

ously in violation of the disjunctive provision of the ordi

nance prohibiting standing, loitering or walking “ so . . .

as to obstruct free passage” on a street or sidewalk. Smith

v. City of Birmingham, supra, 42 Ala. App. ------ at n. 1,

168 So. 2d at 36-37, n. I.14 The Middlebrooks opinion defin

itively adopted this view. Section 1142:

A. 2d 36 (1955), which also quotes Galpern, 38 N. J. Super, at

30, 118 A. 2d at 49, but is otherwise irrelevant. The facts in

Galpern, which sustain the conviction of a lawyer for congregating

with others on a sidewalk and refusing to move on when ordered

by police, evidence that the rule of the New York decision, adopted

by the Alabama Court of Appeals, leaves the police judgment to

issue a dispersal order virtually immune against judicial review.

14 The footnote is confusing because it quotes or summarizes de

cisions of the courts of other States—whether for purposes of

approval or of distinction is unclear—which rest on statutes dif

ferent from §1142 and differing among themselves. The holding

in the Smith case turns on construction of the term “sidewalk”

in §1142, and so is not helpful on the larger questions posed by

the ordinance.

. . . is directed at obstructing the free passage over,

on or along a street or sidewalk by the manner in

which a person accused stands, loiters or walks there

upon. Our decisions make it clear that the mere re

fusal to move on after a police officer’s requesting that

a person standing or loitering should do so is not

enough to support the offense.

That there must also be a showing of the accused’s

blocking free passage is the ratio decidendi of Phifer

v. City of Birmingham . . . and Shuttlesworth v. City

of Birmingham . . . In this respect, we distinguish our

reasoning from that employed in Tinsley v. City of

Richmond, 202 Ya. 707, 119 S. E. 2d 488. See Smith

v. City of Birmingham. . . .

The judges of this court in Shelton v. City of Birming

ham . . . divided two to one as to whether or not evi

dence of a policeman ordering a defendant to move on

under a similar ordinance was sufficient to make a

prima facie case. Regardless of the quantum of proof

required, the court in the instant case is again, as it

was in the Shelton case, unanimous in its conclusion

[affirming a civil rights demonstrator’s conviction]

(------Ala. App. a t------- , 170 So. 2d at 426).

Thus, as now viewed by the Alabama Court of Appeals,

the loitering-after-order provision of §1142 is violated only

when a defendant (1) stands, loiters or walks on the streets

or sidewalks so as to obstruct free passage, (2) is requested

by an officer to move on, (3) thereafter loiters or stands

on the street or sidewalk. At trial on the charge, the fact

that the policeman requested the defendant to move on

makes a prima facie case that the defendant was previously

standing, loitering or walking so as to obstruct the streets

23

or sidewalks, and the defendant can justify disobedience

of the order only if he can show that it was “purely arbi

trary and was not calculated in any way to promote the

public order.”

These decisions concededly narrow the sweeping scope

of §1142 as written. However, they are ineffective for

several reasons to give constitutional validity to petitioner’s

conviction.

First, the decisions post-date petitioner’s arrest and con

viction, and so cannot retrospectively validate the ordinance

as applied in his case. Bouie v. City of Columbia, 378 U. S.

347, 352-354 (1964). Petitioner took this sweeping regula

tion as he found it written; as written it was unconstitu

tional on its face; because unconstitutional on its face, he

was entitled to disobey it. Cf. Lovell v. Griffin, 303 U. S. 444

(1938); Largent v. Texas, 318 U. S. 418 (1943); Staub v.

Baxley, 355 IT. S. 313 (1958).

Second, the limitation of a citizen’s obligation to obey

a police order to circumstances where the citizen has been

loitering so as to obstruct free passage prior to the order

is an ineffective limitation, coupled as it is with the rule

that the fact of issuance of the order establishes prima facie

the circumstance of prior obstructive loitering. The effect

of the “prima facie” rule is to require the citizen who dis

obeys a police order to prove at his trial that he was not

loitering so as to obstruct free passage prior to the order.

That requirement in effect erases prior loitering as an

operative element of the charge, for the city need not

prove it at the trial. And it can hardly be supposed that

the issuance of a police order has a sufficient rational ten

dency to show the order’s justification to permit Alabama

constitutionally to shift the burden of proof of non-justifica

24

tion to the defendant. Dombrowshi v. Pfister, 380 U. S.

479, 494-496 (1965); see Tot v. United States, 319 U. S.

463, 469 (1943). What is at issue here is the method of

litigation not merely of an element of the charge of loitering,

but of a defendant’s First-Fourteenth Amendment defense

to that charge.15 On such an issue, the State may not con

sistently with those Amendments shift the burden of proof

to the accused; Speiser v. Randall, 357 U. S. 513 (1958),

is squarely dispositive. Indeed, §1142 presents a far

stronger case of unconstitutional burden-shifting than

Speiser. For the defendant cannot fairly be required to

disprove the policeman’s justification for an order at the

trial unless the defendant be given some opportunity to in

quire concerning the basis of the order at the time it is

issued. But the vagueness of the prohibition that the de

fendant “ stand or loiter” after the order, see pp. 2-3 supra,

makes any pause for purposes of inquiry impermissibly

hazardous.

Finally, even if §1142, as applicable in petitioner’s case,

clearly precluded conviction except on proof that the peti

tioner had stood, loitered or walked on the sidewalk so

as to obstruct free passage, and had then wilfully refused

15 Although the petitioner’s version of the facts surrounding his

arrest was that he was merely walking on the street when accosted

by Patrolman Byars, the version upon which the State of Alabama

relies to support his conviction is that petitioner was addressing

a group of persons on a street corner. That this is activity pro

tected by the First and Fourteenth Amendments is hardly dis

putable. In any event, the ordinance in its normal application

clearly applies to many sorts of First-Fourteenth Amendment

activity, see p. 15 supra; and, where this is the case, peti

tioner need not show that his own conduct was protected to chal

lenge the ordinance for overbreadth. Thornhill v. Alabama, 310

U. S. 88 (1940); Aptheker v. Secretary of State, 378 U. S. 500

(1964).

25

to obey a policeman’s order to move on, the ordinance would

remain void for overbreadtli. The point was decided under

a virtually identical ordinance in In Be Bell, 19 Cal. 2d 488,

122 P. 2d 22 (1942) (per Mr. Justice Traynor),16 upon au

thority of this Court’s decisions in Thornhill v. Alabama,

310 U. S. 88 (1940), and Carlson v. California, 310 U. S. 106

(1940). Justice Traynor reasoned— rightly, petitioner be

lieves—that this “ sweeping prohibition . . . would apply

equally against peaceful pickets, shoppers engrossed in a

window display, invalids in wheelchairs, acquaintances who

stand engaged in conversation.” 19 Cal. 2d at 497, 122 P.

2d at 28.17 The proscription of standing, loitering, or walk

ing on any sidewalk encompasses all these classes of per

sons, together with others—the peaceful demonstrators in

Fields v. South Carolina, 375 U. S. 44 (1963), and Henry

v. City of Bock Hill, 376 U. S. 776 (1964); the orators in

Kuns v. New York, 340 U. S. 290 (1951), and Niemotko v.

Maryland, 340 U. S. 268 (1951)—who exercise their First-

Fourteenth Amendment freedoms on the public sidewalks.

It is hardly debatable that an interdiction in even the nar

rowest of these terms, an interdiction of “ loitering” sim-

16 The ordinance in Bell was broader in one aspect than §1142,

making it unlawful “ to loiter, stand, or sit upon any public

highway, alley, sidewalk or crosswalk so as to in any manner

hinder or obstruct the free passage therein or thereon of persons

or vehicles passing or attempting to pass along the same, or

so as to in any manner annoy or molest persons passing along

the same.” But Justice Traynor’s opinion makes clear that the

California Supreme Court found the provision overbroad in its

“obstruct” aspect independently of its “molest” aspect. 19 Cal.

2d at 496, 122 P. 2d at 27-28.

17 That these applications are not fantastic imaginings—at least

where citizens on the streets make themselves personally obnoxious

to officers—is evidenced by the record in People v. Galpern, note

13, supra. The constitutionality of the statute as applied in that

case was not before the court.

26

pliciter, would be overbroad and hence unconstitutional.18

And the qualifications that the loitering, or standing or

walking, constitute “blocking free passage,” Middlebroohs

18 Every court except the Supreme Court of Virginia which has

considered the constitutionality of a proscription of loitering

simpliciter has held such a proscription void for overbreadth and

vagueness. Territory of Hawaii v. Anduha, 48 F. 2d 171 (9th Cir.

1931) ; Soles v. City of Vidalia, 92 Ga. App. 839, 90 S. E. 2d 249

(1955); State v. Caez, 81 N. J. Super. 315, 195 A. 2d 496 (1963);

City of St. Louis v. Gloner, 210 Mo. 502, 109 S. W. 30 (1908) ;

People v. Diaz, 4 N. Y. 2d 469, 151 N. E. 2d 871 (1958) ; City of

Akron v. Effland, 112 Ohio App. 15, 174 N. E. 2d 285 (1960);

Ex parte Mittelstaedet, 164 Tex. Crim. 115, 297 S. W. 2d 153

(1957) ; cf. State v. Hunter, 106 N. C. 796, 11 S. E. 366 (1890);

Village of Deer Park v. Schuster, 16 Ohio Ops. 485, 30 Ohio L.

Abs. 466 (C. Com. Pis. 1940). Contra: Benson v. City of Norfolk,

163 Va. 1037, 177 S. E. 222 (1934) ; Tinsley v. City of Richmond,

202 Va. 707, 119 S. E. 2d 488 (1961), app. dism’d, 368 U. S. 18

(1961).

State courts have sustained certain limited classes of regula

tions prohibiting loitering, standing or wandering on the streets:

(A ) Prohibitions of loitering at late hours or under suspicious

circumstances and failing to give a good account of oneself:

Dominguez v. City and County of Denver, 147 Colo. 233, 363

P. 2d 661 (1961) ; City of Portland v. Goodwin, 187 Ore. 409,

210 P. 2d 577 (1949). But such regulations are construed to

require overt suspicious conduct, ibid.; Harris v. District of

Columbia, 132 A. 2d 152, 154 (M. C. A. D. C. 1957), rev’d on

other grounds, 251 E. 2d 913 (D. C. Cir. 1958); Harris v. District

of Columbia, 192 A. 2d 814 (C. A. D. C. 1963); State v. Salerno,

27 N. J. 289, 296, 142 A. 2d 636, 639 (1958) (dictum); absent

such a limitation, they are unconstitutional, Headley v. Selkowitz,

171 So. 2d 368 (Fla. 1965).

(B) Prohibitions of loitering by specified classes of persons

(known thieves, pickpockets, etc.) often for specific illegal pur

poses : Harris v. District of Columbia, supra, in 132 A. 2d 152; In re

Cregler, 56 Cal. 2d 308, 363 P. 2d 305, 14 Cal. Rptr. 289 (1961).

These are the classical “vagrancy” loitering regulations.

(C) Prohibitions of loitering in certain specified places whose

nature suggests a specific illicit purpose of the loiterer: schools,

State v. Starr, 57 Ariz. 270, 113 P. 2d 356 (1941); Phillips v.

Municipal Court, 24 Cal. App. 2d 453, 75 P. 2d 548 (1938); People

v. Johnson, 6 N. Y. 2d 549, 161 N. E. 2d 9 (1959) ; railroad toilets

or platforms, People v. Bell, 306 N. Y. 110, 115 N. E. 2d 821

2 7

v. City of Birmingham, supra, does not sufficiently narrow

the interdiction. This qualification does not require any

purpose to obstruct, or any knowledge that free passage

is obstructed, merely that “ free passage” be blocked.* 19

What constitutes “ free passage” remains unclear, and thus

is left at the risk of the defendant, the whim of the police

man (whom the defendant may not question), the arbitrary

determination of a magistrate or trial court. No use of the

(1953); waterfront docks and warehouses, People v. Merolla, 9

N. Y. 2d 62, 172 N. B. 2d 541 (1961). Such regulations are

regularly construed to forbid only loitering for the specific illicit

purpose. Ibid.; In re Huddleson, 229 A. C. A. No. 3, 721, 40

Cal. Rptr. 581 (1964).

(D) Prohibitions of presence on the streets by specified classes

of persons (ordinarily minors) at specified times: Thistlewood

v. Trial Magistrate for Ocean City, 236 Md. 548, 204 A. 2d 688

(1964). These are the classical curfew regulations.

(E) Prohibitions of actual obstruction of streets or sidewalks

by loitering or standing: Ex parte Bodkin, 86 Cal. App. 2d 208,

212, 194 P. 2d 588, 591-592 (1948); City of Chariton v. Fitz

simmons, 87 Iowa 226, 229-230, 54 N. W. 146, 147 (1893); State

v. Sugarman, 126 Minn. 477, 479, 148 N. W. 466, 468 (1914);

Commonwealth v. Challis, 8 Pa. Super. 130, 132 (1898); City

of Tacoma v. Roe, 190 Wash. 444, 445, 68 P. 2d 1028, 1029 (1937).

At the cited pages the respective courts construe these regulations

as requiring actual obstruction of persons attempting to use the

sidewalks, not mere loitering in such a manner as might obstruct

hypothetical users of the sidewalks. And see Whaley v. Cavanagh,

237 F. Supp. 900 (S. D. Cal. 1963) aff’d per curiam on opinion

below, 341 F. 2d 295 (9th Cir. 1965), where the facial constitu

tionality of the regulation was not challenged and actual ob

struction of pedestrians was found.

19 On this ground, the decisions in paragraph (B) of the pre

ceding footnote are distinguishable. The Alabama Court of Ap

peals in Middlebroohs apparently meant to justify the issuance

of a police order under §1142 whenever, in the language of the

first sentence of the second paragraph of that section, “any person

or number of persons . . . so stand, loiter or walk upon any street

or sidewalk in the City as to obstruct free passage over, on or

along said street or sidewalk.” (Emphasis added.)

2 8

sidewalks that can be imagined fails in some measure to

obstruct free passage-—even though no pedestrian in fact

be jjassing or impeded. The window-shopper, the delivery

man, the peaceful picket, the peaceful demonstrator, the

pedestrian who kneels to tie a shoe-lace, all obstruct free

passage.

It is almost needless to say that such an act cannot

be enforced, and that no attempt will be made to en

force it, indiscriminately. It may be enforced against

those poor hapless ones who are unable to assert or

protect their rights, but as to all others it will remain a

dead letter. It may be enforced to suppress one class

of idlers in order to make a place more attractive to

idlers of a more desirable class . . . ,20

or, as here, to suppress the members of an unpopular race.

If the City of Birmingham wishes to prohibit the actual

obstruction of pedestrians by standing, loitering or walk

ing on a sidewalk with a purpose to obstruct it, the City

may do so in those narrow terms. But a prohibition of all

standing, loitering or walking in such a manner as to ob

struct free passage sweeps too broadly; and disobedience

of a police order justifiable in those vague terms may not

constitutionally be punished. Cox v. Louisiana, supra, 379

U. S. at 551.21

20 Territory of Hawaii v. Anduha, 48 F. 2d 171, 173 (9th Cir.

1931).

21 Tinsley v. City of Richmond, 368 U. S. 18 (1961), is not

apposite in this regard. Nowhere in the Virginia courts or in her

jurisdictional statement in this Court did Tinsley invoke the

First Amendment, either in her own behalf or as a ground for

general invalidity of the ordinance there involved. Nor, on the

29

III.

On Its Face, and as Applied to Petitioner’s Conduct,

Section 1142’s Proscription of Standing, Loitering or

Walking on a Sidewalk so as to Obstruct Free Passage

Thereon Is Vague and Overbroad in Violation of the

First and Fourteenth Amendments.

For the reasons stated in the preceding paragraph, that

portion of Birmingham Code §1142 which purports to make

it unlawful “ for any person or any number of persons to

so stand, loiter or walk upon any . . . sidewalk in the City

as to obstruct free passage over, on or along said . . . side

walk” (emphasis added) is too vague and overbroad to meet

First-Fourteenth Amendment demands.

IV.

Petitioner’s Conviction for Violation of §1231 Is Sup

ported by No Evidence.

If construed as broadly as it is written, Birmingham Code

§1231, making it “ unlawful for any person to refuse or

fail to comply with any lawful order, signal or direction of

a police officer,” would be objectionable for the reasons

stated at pp. 14-15 supra. The Alabama Court of Appeals,

facts of Tinsley, was any colorable First Amendment claim pre

sented. Compare note 15 supra. Tinsley put her contentions simply

on a right of personal liberty to move about the streets, a right

of the sort given expression in Pinkerton v. Verb erg, 78 Mich. 573,

44 N. W. 579 (1889), quoted in her jurisdictional statement at

p. 9, n. 4. But it is settled that the standards of permissible

vagueness are uniquely stringent where a challenged regulation

touches the freedoms of expression protected by the First Amend

ment as incorporated in the Fourteenth. Compare N.A.A.C.P. v.

Button, 371 U. S. 415, 432 (1963), and authorities cited, with

' United States v. National Dairy Prods. Co., 372 U. S. 29, 36 (1963).

30

however, has put a quite narrow construction on the sec

tion. Reversing the conviction of petitioner’s co-defendant

below, that court said of §1231:

. . . This section appears in the chapter regulating

vehicular traffic, and provides for the enforcement of

the orders of the officers of the police department in

directing such traffic. There is no suggestion in the

evidence that the defendant violated any traffic regula

tion of the city by his refusal to move away from Shut-

tlesworth when ordered to do so. (Phifer v. City of

Birmingham, 42 Ala. App. 282, 160 So. 2d 898, 901

(1963), cert, denied, 160 So. 2d 902 (Ala. 1964).)

Nor is there any evidence in the present case that peti

tioner Shuttlesworth violated any vehicular traffic regula

tion. Thus—unless the Alabama Court of Appeals is per

mitted, Alice-like and in blatant violation of due process of

law—to change the meaning of the State’s penal statutes

case by case, petitioner’s conviction under §1231 is entirely

lacking in evidentiary support. Thompson v. City of Louis

ville, 362 U. S. 199 (1960); Garner v. Louisiana, 368 U. S.

157 (1961); Taylor v. Louisiana, 370 U. S. 154 (1962);

Fields v. Fairfield, 375 U. S. 248 (1963); Barr v. City of

Columbia, 378 U. S. 146 (1964).

31

CONCLUSION

The judgment of the Alabama Court of Appeals affirm

ing petitioner’s conviction should be reversed.

Respectfully submitted,

Jack Greenberg

J ames M. N abrit, III

N orman C. A maker

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

P eter A. H all

Orzell B illingsley, Jr.

1630 Fourth Avenue North

Birmingham, Alabama

A nthony G. A msterdam

3400 Chestnut Street

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104

Attorneys for Petitioner

" '■ b D * 38