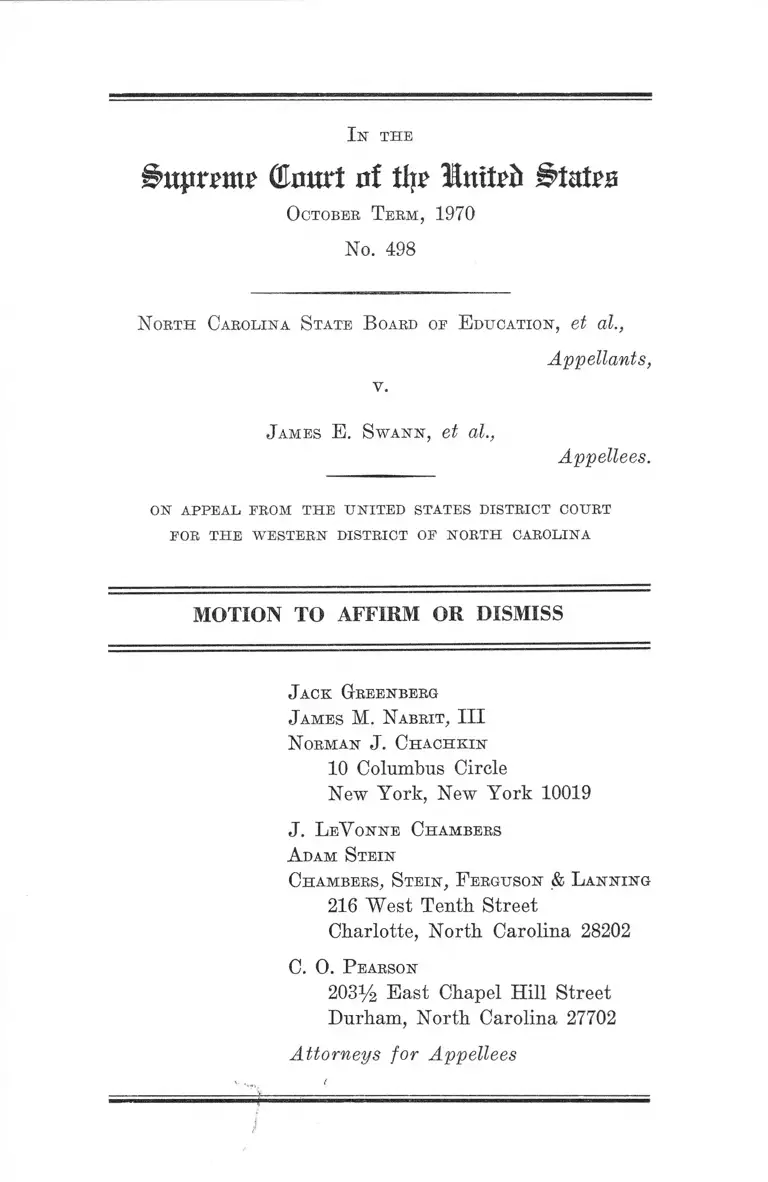

North Carolina State Board of Education v. Swann Motion to Affirm or Dismiss

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1970

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. North Carolina State Board of Education v. Swann Motion to Affirm or Dismiss, 1970. e1d714ba-bf9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/7bb12756-e108-4305-8e13-fc5eee128faf/north-carolina-state-board-of-education-v-swann-motion-to-affirm-or-dismiss. Accessed January 27, 2026.

Copied!

I n t h e

(ftmtrt uf thv Imtpfc States

Octobee Teem, 1970

No. 498

North Carolina State B oard of E ducation, et al.,

Appellants,

v.

James E. Swann , et al.,

Appellees.

ON A PPE A L FROM T H E U N IT E D STATES D ISTR IC T COURT

FOR T H E W E STE R N D ISTRICT OF N O R T H CAROLINA

MOTION TO AFFIRM OR DISMISS

Jack Greenberg

James M. Nabrit, III

Norman J. Chachkin

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

J. L eV onne Chambers

A dam Stein

Chambers, Stein, F erguson & Lanning

216 West Tenth Street

Charlotte, North Carolina 28202

C. O. Pearson

203% East Chapel Hill Street

Durham, North Carolina 27702

Attorneys for Appellees

I N D E X

Opinions B elow ............... 1

Jurisdiction ........................ 2

Questions Presented............................................................ 2

Statement ................................... 3

Introduction ............... 3

Proceedings during 1969-70 before a Single Dis

trict Judge .... 4

Obstruction of the District Court Orders; Conven

ing of Three-Judge Court.......................................... 6

A rgument—

I. The Case Presents No Substantial Questions

Not Previously Decided by This C ourt........... 11

A. This Court Decided in 1809 in United

States v. Peters That State Legislatures

Could Not Validly Annul Federal Court

Judgments ...................................................... 11

B. This Court Decided in Green v. County

School Board of New Kent County That

School Boards Must Take Affirmative

Action to Disestablish Dual Segregated

School Systems .............................................. 16

II. The Appeal Should Be Dismissed Because

the Case Was Not Required to Be Heard by

a Three-Judge Court .......................................... 17

PAGE

11

PAGE

A. The Case Involved Primarily a Supremacy

Clause Issue and Thus no Three-Judge

Court Was Required Under the Doctrine

of Swift & Co. v. Wickham ........................... 17

B. The Anti-Bussing Law Is So Obviously

Unconstitutional That no Three-Judge

Court Was Required........................... 18

Conclusion ........... 19

Table op A uthobities

Cases:

Bailey v. Patterson, 369 U.S. 31 (1962).....................3,10,18

Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U.S. 294 (1955) 12

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954) 12,19

Brown v. South Carolina State Board of Education,

296 P. Supp. 199 (D. S.C. 1968), judgment affirmed,

393 U.S. 222 (1968)............................. ............ ............... 13

Bryant v. State Board of Assessment, 293 F. Supp.

1379 (E.D. N.C. 1968).................................................... 15

Bush v. Orleans Parish School Board, 194 F. Supp. 182

(E.D. La. 1961), judgment affirmed, sub nom. Tug-

well v. Bush, 367 U.S. 907 (1961) and G-remillion v.

United States, 368 U.S. 11 (1961)....................... ........ 13

Bush v. Orleans Parish School Board, 191 F. Supp.

871 (E.D. La. 1961), judgment affirmed, sub nom.

Legislature of Louisiana v. United States, 367 U.S.

907 (1961) and Denny v. Bush, 367 U.S. 908 (1961).... 13

Bush v. Orleans Parish School Board, 190 F. Supp. 861

(E.D. La. 1960), judgment affirmed, New Orleans v.

Bush, 366 U.S. 212 (1961) 12

I l l

Bush v. Orleans Parish School Board, 188 P. Supp. 916

(E.D. La. 1960), stay denied sub nom. United States

y. Louisiana, 364 U.S. 500 (1960), judgment affirmed,

365 U.S. 569 (1961)....................................... ..... .......... 12,14

Bush v. Orleans Parish School Board, 187 P. Supp. 42

(E.D. La. 1960), stay denied, 364 U.S. 803, judgment

affirmed, Orleans Parish School Board v. Bush, 365

U.S. 569 (1961)................................................................ 12,14

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 LT.S. 1 (1958)........................... ...12,16

Ex parte Poresky, 290 U.S. 30 (1933)............................... 18

Faubus v. United States, 254 F.2d 797 (8th Cir. 1958),

cert, denied, 358 U.S. 829 .............................................. 15

Godwin v. Johnston County Board of Education, 301

P. Supp. 339 (E.D. N.C. 1969)...................................... 15

Green v. County School Board of New Kent County,

391 U.S. 430 (1968)........................................................ 16,18

Hall v. St. Helena Parish School Board, 197 P. Supp.

649 (E.D. La. 1961), judgment affirmed, 368 U.S. 515

(1961) .... .............. ................. ............. ............... ............. 13

Harvest v. Board of Public Instruction of Manatee

County, 312 P. Supp. 269 (M.D. Pla. 1970)............... 15

Lee v. Macon County Board of Education, 267 P. Supp.

458 (M.D. Ala. 1967), affirmed sub nom. Wallace v.

United States, 389 U.S. 215 (1967)..........................13,15

Louisiana Education Commission for Needy Children

v. U. S. District Court, 390 U.S. 939 (1968)............... 13

PAGE

Marbury v. Madison, (US) 1 Cranch 137.........

Meredith v. Pair, 328 F.2d 586 (5th Cir. 1962)

16

15

IV

PAGE

Mitchell v. Donovan, 398 U.S. 427 (1970)....................... 10

Moore v. Charlotte-Meeldenburg Board of Education,

No. 444, O.T. 1970 ....... .................................................. 3

Moore v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education,

312 E. Supp. 503 (W.D. N.C. 1970)............................ 1,8

Poindexter v. Louisiana Financial Assistance Commis

sion, 275 F. Supp. 833 (E.D. La. 1967), judgment af

firmed, 389 U.S. 571 (1968).......................................... 13

Poindexter v. Louisiana Financial Assistance Commis

sion, 296 F. Supp. 686 (E.D. La. 1968), judgment

affirmed, sub nom. Louisiana Education Commission

for Needy Children v. Poindexter, 393 U.S. 17 (1968) 13

Rockefeller v. Catholic Medical Center, 397 U.S. 820

(1970) ................................................................................ 10

Sterling v. Constantin, 287 U.S. 378 (1932)................... 15

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education,

312 F. Supp. 503 (W.D. N.C. 1970)....................... ....... 1

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education,

No. 281, O.T. 1970 ........................................................ 3,4, 5

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education,

243 F. Supp. 667 (W.D. N.C. 1965), affirmed, 369

F.2d 29 (4th Cir. 1966); 300 F. Supp. 1358 (1969);

300 F. Supp. 1381 (1969); 306 F. Supp. 1291 (1969);

306 F. Supp. 1299 (1969); 306 F. Supp. 1301 (1969);

306 F. Supp. 1306 (1969) ; 311 F. Supp. 265 (1970).... 4

Swift & Co. v. Wickham, 382 U.S. I l l (1965)...........3,10,17

Thomason v. Cooper, 254 F.2d 808 (8th Cir. 1958)....... 15

Turner v. Memphis, 369 U.S. 350 (1962)....................... 18

United States v. Peters, (US) 5 Cranch 115, 3 L.Ed. 53 11

United States v. Wallace, 222 F. Supp. 485 (M.D. Ala.

1963) 15

V

Statutes: p a g e

Constitution of the U. S., Article VI, Supremacy Clause

2,10

28 U.S.C. §1253 .............................................................. 2, 4,17

28 U.S.C. §2281 .................................................... ....... 5,10,17

28 U.S.C. §2283 ....... 14

28 U.S.C. §2284 .................................................................. 5

N.C. Gen. Stat. §115-176.1 .............................2, 3, 7,10,11,16

Other Authorities :

1A Moore’s Federal Practice............................................ 14

Rule 16, Rules of the Supreme Court of the United

States ............................................................................... 1

I n th e

Bnpnmt (Emtrt of % lotted States

October Term, 1970

No. 498

North Carolina State B oard of E ducation, et al.,

Appellants,

v.

James E. Swann, et al.,

Appellees.

o n a p p e a l f r o m t h e u n i t e d s t a t e s d i s t r i c t c o u r t

FOR T H E W ESTERN D ISTRICT OF N O R T H CAROLINA

MOTION TO AFFIRM OR DISMISS

Appellees, pursuant to Rule 16 of the Rules of the Su

preme Court of the United States, move that the final judg

ment and decree of the district court be affirmed on the

ground that it is manifest that the questions are so unsub

stantial as not to warrant further argument, or, in the

alternative, to dismiss the appeal herein on the ground

that it is not within the jurisdiction of the Court.

Opinions Below

The opinion of the three-judge district court is reported

as Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education

(also Moore v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Educa

tion), 312 F. Supp. 503 (W.D. N.C. 1970).

2

Jurisdiction

Appellees submit that the Court does not have juris

diction of a direct appeal pursuant to 28 U.S.C. §1253

because the case is not a “ civil action, suit or proceeding

required by any Act of Congress to be heard and deter

mined by a district court of three judges” (emphasis

added). Appellees’ argument in support of the contention

that a three-judge court was not required appears infra

in Argument II.

Questions Presented

1. Whether the judgment below may be affirmed on the

ground that N.C. Glen. Stat. §115-176.1 was an unconsti

tutional legislative attempt to nullify rights of the appel

lees under a prior judgment of a United States District

Court, and that the state statute thus violates the Suprem

acy Clause of Article VI of the Constitution of the United

States.

2. Whether the court below was correct in determining

that portions of N.C. Gen. Stat. §115-176.1, known as the

anti-bussing law, are unconstitutional because they inter

fere with a school board’s performance of its affirmative

constitutional duty under the equal protection clause of

the Fourteenth Amendment to eliminate racial segregation

in the public schools.

3. Whether the appeal should be dismissed on the ground

that no direct appeal from the district court is provided

where the case was not one required to be heard by a dis

trict court of three judges since:

(a) the case involves an issue under the Supremacy

Clause (the conflict of a state law with a prior federal

3

court order) and thus no three-judge court is required

under the doctrine of Swift <& Co. v. Wickham, 382 U.S.

I l l (1965); and

(b) numerous prior decisions of this Court make it plain

that the statute is unconstitutional and thus no three-judge

court is required under the doctrine of Bailey v. Patterson,

369 U.S. 31 (1962).

Statement

Introduction

This is a direct appeal by the North Carolina State Board

of Education and a group of state officials1 from the order

of a three-judge district court ruling that a portion of

N.C. Ben. Stat. §115-176.1, known as the anti-bussing law,

was unconstitutional because it interfered with the affirma

tive duty of local school boards under the Fourteenth

Amendment to desegregate the public schools. A companion

appeal involving the same judgment is also pending here

as No. 444, O.T. 1970, sub nom. Moore v. Charlotte-Mecklen

burg Board of Education. The proceeding in the three-

judge court was an ancillary proceeding connected with the

school desegregation case involving Charlotte-Mecklenburg

which is also now pending here as Swann v. Charlotte-Meck

lenburg Board of Education, O.T. 1970, No. 281, certiorari

granted June 29, 1970.

This direct appeal is in an unusual posture in that it

has been scheduled for argument and briefing, prior to any

action by the Court on the Jurisdictional Statement. (Order

of the Chief Justice herein dated August 31, 1970.) Not

1 Appellants herein include the State Superintendent of Public

Instruction, the Governor of North Carolina, the Controller of the

State Board of Education, and a judge of the Superior Court of

Mecklenburg County who issued an order allegedly interfering with

the federal court desegregation orders.

4

withstanding this action, appellees believe it appropriate

to file this response to the Jurisdictional Statement because

we believe the case involves no substantial issues not pre

viously decided by the Court and because we doubt that

the necessary jurisdictional requisites for direct appeal are

present under 28 U.S.C. §1253.

Proceedings during 1969-70 before a Single District Judge

The school desegregation case brought by Negro pupils

and parents against the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of

Education was commenced in 1965 and there has been ex

tensive litigation ever since which has culminated in the

Swann case now pending in this Court. A full statement

of the history of the proceedings from 1965 to date is

contained in Petitioners’ Brief in Swann, No. 281, O.T.

1970. The case has resulted in numerous reported deci

sions which are cited in the note below.2

On April 23, 1969, after a plenary hearing, the district

judg'e rendered a decision and order finding that the school

system was still unlawfully segregated and directing that

that defendants file a plan for complete desegregation of

the system {Swann, swpra, 300 P. Supp. 1358). The court

specifically directed that the school board consider altering

attendance areas, pairing or consolidation of schools, trans

portation or bussing of students and any other method

which would effectuate a racially unitary system. Exten

sive litigation ensued as the board submitted a series of

proposals and the court rejected them as unsatisfactory to

disestablish the segregated system. In the midst of this

2 See, e.g., Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education,

243 F. Supp. 667 (W.D. N.C. 1965), affirmed, 369 F.2d 29 (4th

Cir. 1966); 300 P. Supp. 1358 (1969); 300 P. Supp. 1381 (1969) ;

306 P. Supp.1291 (1969); 306 F. Supp.1299 (1969); 306 P. Supp.

1301 (1969); 306 P. Supp. 1306 (1969) ; 311 P. Supp. 265 (1970)..

5

litigation about the remedy to implement the April 23 deci

sion, the North Carolina legislature enacted the anti-bussing

bill proposed by a member of the Mecklenburg delegation.

The measure which was ratified July 2, 1969, included the

following two sentences (later held unconstitutional):

No student shall be assigned or compelled to attend

any school on account of race, creed, color or national

origin, or for the purpose of creating a balance or

ratio of race, religion or national origin. Involuntary

bussing of students in contravention of this Article is

prohibited, and public funds shall not be used for any

such bussing.

Plaintiffs in the Swann case promptly obtained leave to

file a supplemental complaint which sought injunctive and

declaratory relief against the above-quoted portion of the

anti-bussing law; they asked that a three-judge court be

convened pursuant to 28 U.S.C. §§2281 and 2284 (App.

No. 281, pp. 460a-479a). However, no three-judge court

was convened at that time and the court took no action

on the requests for relief because the school board thought

that the anti-bussing law did not interfere with the school

board’s proposed plan to bus about 4,000 black children

to white suburban schools (306 F. Supp. at 1295).

After further hearings to consider the board’s further

proposals during the fall of 1969 and the operation of the

interim plan (which involved bussing black children to

formerly white schools), the district court finally directed

that a plan be prepared by the court’s expert consultant.

The court consultant’s plan was ordered into effect in an

order entered February 5, 1970, reported at 311 F. Supp.

265. The February 5 order provides for the alteration of

some school attendance areas, the creation of certain “ satel

lite” or non-contiguous zones from which pupils would be

transported to school, the pairing and clustering of certain

6

schools with the alteration of grade structures, and trans

portation for pupils who live more than walking distance

(as determined by the board) from the school to which

they are assigned. The pairing and clustering of 10 black

and 24 white elementary schools will result in pupils of

both races being transported to schools which were for

merly segregated. The district court made extensive sup

plemental findings about the amount of transportation re

quired and its relation to the large school bus transportation

system which was already in operation in the community

(App. No. 281, p. 1198a).

Obstruction of the District Court Orders; Convening of

Three-Judge Court

Following the order of February 5, 1970, numerous citi

zens, under the banner of “ Concerned Parents Association,”

held meetings to protest the order, vowing to defy, delay,

obstruct and in any way prevent its implementation. On

January 30, 1970, they filed a proceeding in the Mecklen

burg County Superior Court (Harris v. Self) and obtained

an ex parte temporary restraining order, purportedly pre

venting the superintendent from paying the fees and ex

penses of the corrrt consultant as directed on December 2,

1969. They filed an amended complaint on February 12,

1970, in the Mecklenburg County Superior Court and ob

tained an amended temporary restraining order which en

joined the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education from

expending any money for the purpose of purchasing or

renting any motor vehicle or operating or maintaining such

for the purpose of involuntarily transporting students in

the Charlotte-Mecklenburg school system from one school

to another and from one district to another. The order

entered by the Mecklenburg Superior Court on January 30,

1970, was modified to permit payment of the court con

sultant on approval of the Board of Education.

7

On February 11, 1970, Governor Robert W. Scott issued

a public statement to the effect that North Carolina General

Statute §115-176.1 prohibited the involuntary bussing of

students, that he had taken an oath to uphold the laws of

the State of North Carolina, and that he was directing all

officials to enforce this statute. On February 12, 1970,

Governor Scott instructed the Director of the Department

of Administration that “use of public funds for providing

bus transportation shall be strictly in accordance with the

appropriations made by the 1969 General Assembly, and

for no other purpose. No authorization will be given for

use of any other funds to provide bussing to achieve school

attendance for the purpose of creating a balance or ratio,

religion or national origins” (sic.). Copies of the letter

were forwarded to Dr. A. Craig Phillips, the Superin

tendent of Public Instruction; Dr. Dallas Herring, Chair

man of the State Board of Education; Mr. A. C. Davis,

the Controller of the State Board of Education; and Mr.

Tom White, Chairman of the State Advisory Budget Com

mission. Shortly thereafter, Dr. A. Craig Phillips issued

a similar statement and further advised that he was op

posed to bussing. On February 23, 1970, he wrote to Dr.

William S. Self, Superintendent of the Charlotte-Mecklen-

burg Schools and advised, “ No additional State funds will

be allocated to the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Educa

tion to provide bussing of students for the purpose of

creating a balance or ratio of students in the schools.”

On the same date, Mr. A. C. Davis directed a memorandum

to the superintendent of each local school system in the

State advising that the General Assembly had appro

priated funds for the operation of 9,510' buses during the

1969-70 school year and 9,635 buses during the 1970-71

school year. The memorandum advised that approximately

9,443 buses were presently in use and that, “The appro

priation does not include funds for the transportation of

8

thousands of additional students and the operating costs

of hundreds of additional buses which might be made neces

sary by the reorganization of schools. No additional State

funds will be allocated to school administrative units to

provide bussing of students for the purpose of creating

a balance or ratio of students in schools.”

On February 13, 1970, plaintiffs moved the court (App.

No. 281, p. 840a) to add as additional parties-defendant the

Governor of the State; Mr. A. C. Davis, Controller of the

State Board of Education; the Honorable William K.

McLean, the Superior Court Judge who issued the tem

porary restraining order, each plaintiff in the Superior

Court proceeding and their attorney. Plaintiffs also asked

the court to add as additional parties-defendant the Honor

able James Carson who initially proposed the statute here

in question and who had made several public statements

of his intention to file a proceeding in the state court to

enjoin the school board from complying with the Feb

ruary 5, 1970, order of the court. Plaintiffs further sought

an injunction against the enforcement of the state court

restraining order as modified on February 12, 1970, and

to enjoin the defendants from further interference with

the implementation of the orders of the district court.

On February 20, 1970, the resident district judge entered

an order reciting the various events and requesting that

the Chief Judge of the Circuit designate a three-judge

district court (App. No. 281, p. 845a). A three-judge court

was designated on February 24, 1970, and additional par

ties were added by order of February 25, 1970 (App. No.

281, p. 901a).

Meanwhile, on Sunday night, February 22, 1970, approxi

mately 50 adults on behalf of themselves and their children

filed another proceeding (Moore v. Gharlotte-Mecklenburg

Board of Education) in the Mecklenburg County Superior

9

Court seeking to restrain desegregation of the Charlotte-

Mecklenburg schools as directed by the district court. At

10:16 p.m. on that Sunday night, the Honorable Frank

Snepp issued an ex parte temporary restraining order en

joining the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education and

its Superintendent

from instituting or implementing or putting* into oper

ation or effect, or expending any public funds upon,

any plan or program under which children in the City

of Charlotte or Mecklenburg County are denied access

to any Charlotte-Mecklenburg public school because

of their race or color or are compelled to attend any

prescribed Charlotte-Mecklenburg public school be

cause of their race or color.

On Thursday, February 26, 1970, the board removed the

Moore case to the United States District Court. At a spe

cial meeting of the board on Friday, February 27, 1970,

the board chose to comply with the order of the state court

rather than the orders of the federal district court. The

Superintendent announced that all planning and activities

then underway for implementation of the district court’s

order of February 5, 1970, were terminated. On the same

date, plaintiffs moved the court to add the plaintiffs in

the Moore case, their lawyers and the Honorable Frank

Snepp as additional parties-defendant in this case. Plain

tiffs further sought an order enjoining the enforcement of

the state court order and enjoining any further efforts by

all of the defendants from taking steps which would prevent

or inhibit the implementation of the orders of the district

court. Plaintiffs also sought an order finding all members

of the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education and its

Superintendent in contempt and imposing a fine or im

prisonment for each day that the defendants failed to

comply with the court’s orders.

10

The district court on March 6, 1970, entered an order

decreeing that the order by Superior Court Judge Snepp

in the Moore case “is hereby suspended and held in abeyance

and of no force and effect pending the final determination

by a three-judge court or by the Supreme Court of the

issues which will be presented to the three-judge court on

March 24, 1970” (App. No. 281, pp. 925a-927a). The three-

judge court eventually ruled in an opinion dated April 28,

1970, that the challenged portions of the anti-bussing law

were unconstitutional in violation of the equal protection

clause of the Fourteenth Amendment and the Supremacy

Clause of Article VI of the Constitution (312 F. Supp.

503, 510). The initial opinion denied injunctive relief and

granted only a declaratory judgment. However, this por

tion of the original opinion was withdrawn3 and the court

enjoined all of the parties in the Swarm and Moore cases

from “ enforcing, or seeking the enforcement of” the uncon

stitutional portion of N.C. Gen. Stat. 115-176.1.

Although plaintiffs Swann, et al. originally sought a

three-judge court, they subsequently urged upon the dis

trict court that it was empowered to act on the matter as

a single judge and that a three-judge court was not re

quired by 28 U.S.C. §2281 because of the doctrine of Sivift

<& Co. v. Wickham, 382 U.S. I l l (1965), and Bailey v. Pat

terson, 369 U.S. 31 (1962). The three-judge court rejected

these arguments that a three-judge court was not required.4

(312 F. Supp. 503, 507.)

3 The three-judge court determined to grant an injunction rather

than merely a declaratory judgment after taking note of this

Court’s decisions in Rockefeller v. Catholic Medical Center, 397

U.S. 820 (1970), and Mitchell v. Donovan, 398 U.S. 427 (1970).

4 The court below said that it rejected “plaintiffs’ attack upon

our jurisdiction” (312 F. Supp. at 507). However, plaintiffs, by

a brief filed in the trial court sought to make clear that their argu

ment that a single judge might properly have disposed of the case

was not a denial that the three-judge district court had jurisdiction

over the matter, but only an argument that three judges were not

required to decide the case under 28 U.S.C. §2281.

11

A R G U M E N T

It

The Case Presents No Substantial Questions Not Pre

viously Decided by This Court.

A. This Court Decided in 1809 in United Stales v. Peters

That State Legislatures Could Not Validly Annul Fed

eral Court Judgments

It is manifest that the challenged provisions of the -anti

bussing- law, which forbid the consideration of race in the

assignment of pupils, and forbid their being “involuntarily

bussed” attempt to nullify the April 23, 1969, order of the

United States District Court requiring the desegregation

of the public schools in the Charlotte-Mecklenburg system.

The anti-bussing law is a bald attempt to legislatively re

peal the judgment of a court of the United States deciding

rights of litigants under the Constitution and laws of the

United States. The district court order required, inter alia,

the implementation of plans to reassign pupils so as to

eliminate racially segregated schools and the consideration

of the use of transportation facilities to effect that purpose.

The effect of N.C. Gen. Stat. §115-176.1 is to forbid the

school board from engaging in affirmative steps to bring

about racial integration of the schools and eliminate the

dual system established under the compulsion of state segre

gation laws.

This Court unanimously rejected such an assertion of

state power to set aside a federal court decree in an historic

opinion by Chief Justice John Marshall delivered on Feb

ruary 20, 1809, and such assertions have been emphatically

rejected ever since. In United States v. Peters, (US) 5

Cranch 115, 136, 3 L.Ed. 53, 59, it was stated:

12

If the legislatures of the several states may, at will,

annul the judgments of the courts of the United States,

and destroy the rights acquired under those judgments,

the constitution itself becomes a solemn mockery, and

the nation is deprived of the means of enforcing its

laws by the instrumentality of its own tribunals. So

fatal a result must be deprecated by all; and the people

of Pennsylvania, not less than the citizens of every

other state, must feel a deep interest in resisting prin

ciples so destructive of the Union, and in averting

consequences so fatal to themselves.

In recent years there have been a number of attempts

by state officials to nullify decrees of the federal courts

requiring implementation of this Court’s decisions in Brown

v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954), and Brown v.

Board of Education, 349 U.S. 294 (1955). The most serious

such attempt prompted a unanimous opinion of all the

Justices of the Court in 1958 in Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S.

1, 18 (1958) : “No state legislator or executive or judicial

officer can war against the Constitution without violating

his undertaking to support it.”

Ever since Cooper v. Aaron, the Court has disposed of

similar contentions in per curiam decisions nullifying ef

forts at legislative interposition and nullification of deseg

regation decrees of the lower federal courts. Bush v. Or

leans Parish School Board, 187 F. Supp. 42 (E.D. La.

1960; three-judge court), stay denied, 364 U.S. 803, judg

ment affirmed, Orleans Parish School Board v. Bush, 365

U.S. 569 (1961); Bush v. Orleans Parish School Board,

188 F. Supp. 916 (E.D. La. 1960; three-judge court), stay

denied, sub nom. United States v. Louisiana, 364 U.S. 500

(1960), judgment affirmed, 365 U.S. 569 (1961); Bush v.

Orleans Parish School Board, 190 F. Supp. 861 (E.D. La.

I960; three-judge court), judgment affirmed, New Orleans

13

v. Bush, 366 U.S. 212 (1961); Bush v. Orleans Parish School

Board, 191 F. Supp. 871 (E.D. La. 1961; three-judge court),

judgment affirmed, sub nom. Legislature of Louisana v.

United States, 367 U.S. 907 (1961) and Benny v. Bush,

367 U.S. 908 (1961); Bush v. Orleans Parish School Board,

194 F. Supp. 182 (E.D. La. 1961; three-judge court), judg

ment affirmed, sub nom. Tug well v. Bush, 367 U.S. 907

(1961) and Gremillion v. United States, 368 U.S. 11 (1961);

Lee v. Macon County Board of Education, 267 F. Supp. 458

(M.D. Ala. 1967; three-judge court), affirmed, sub nom.

Wallace v. United States, 389 U.S. 215 (1967); Hall v.

St. Helena Parish School Board, 197 F. Supp. 649 (E.D.

La. 1961; three-judge court), judgment affirmed, 368 U.S.

515 (1961); Poindexter v. Louisiana Financial Assistance

Commission, 275 F. Supp. 833 (E.D. La, 1967; three-judge

court), judgment affirmed, 389 U.S. 571 (1968); Poindexter

v. Louisiana Financial Assistance Commission, 296 F. Supp.

686 (E.D. La. 1968; three-judge court), judgment affirmed,

sub nom. Louisiana Education Commission for Needy Chil

dren v. Poindexter, 393 U.S. 17 (1968); Louisiana Educa

tion Commission for Needy Children v. U. S. District Court,

390 U.S. 939 (1968) (prohibition denied); Brown v. South

Carolina State Board of Education, 296 F. Supp. 199 (D.

S.C. 1968; three-judge court), judgment affirmed, 393 U.S.

222 (1968).

The decisions of the district court in this case to require

the further desegregation of the schools and to require

the use of bussing and other techniques were of course not

final until appropriate appeals were exhausted. But rather

than resorting to appeals in due course, the state officials

in North Carolina engaged in discreditable attempts to

review and nullify the judgments of the district court by

resort to state legislative, executive and judicial actions.

These assertions of power were sought to be justified by

arguments that decisions of the district court need not be

14

obeyed and were not lawful until upheld by this Court.

Such a premise must be emphatically rejected, as it was

in the Bush case:

From the fact that the Supreme Court of the United

States rather than any state authority is the ultimate

judge of constitutionality, another consequence of equal

importance results. It is that the jurisdiction of the

lower federal courts and the correctness of their deci

sions on constitutional questions cannot be reviewed

by the state governments. Indeed, since the appeal

from their rulings lies to the Supreme Court of the

United States, as the only authoritative constitutional

tribunal, neither the executive, nor the legislature, nor

even the courts of the state, have any competence in

the matter. It necessarily follows that, pending re

view by the Supreme Court, the decisions of the sub

ordinate federal courts on constitutional questions

have the authority of the supreme law of the land

and must be obeyed. Assuredly, this is a great power,

but a necessary one. See United States v. Peters,

supra, 5 Cranch 135, 136, 9 U.S. 135, 136. (Bush v.

Orleans Parish School Board, 188 F. Supp. 916, 925

(E.D. La. I960).)

The power of the federal district court to stay state

court proceedings where necessary to “ protect or effectuate

its judgments” against threatened relitigation in state

courts is conferred by 28 U.S.C. §2283. See 1A Moore’s

Federal Practice, 2319-2320, 2614-2616. Such orders re

straining conflicting state court proceedings have been is

sued in a number of school desegregation cases. Bush v.

Orleans Parish School Board, 187 F. Supp. 42 (E.D. La.

I960; three-judge court), affirmed, 365 U.S. 569 (1961)

(both the litigants and state judge were enjoined in Bush) •

15

Thomason v. Cooper, 254 F.2d 808 (8th Cir. 1958); Mere

dith v. Fair, 328 F.2d 586 (5th Cir. 1962; en banc).

Nor does it matter that one of the state officers involved

is the Governor of the State, for governors are in no dif

ferent position than other state officials in terms of their

duty to obey federal court judgments. Sterling v. Constan

tin, 287 U.S. 378, 393 (1932); Faubus v. United States, 254

F.2d 797 (8th Cir. 1958), cert. den. 358 U.S. 829; Meredith

v. Fair, 328 F.2d 586 (5th Cir. 1962); United States v.

Wallace, 222 F. Supp. 485 (M.D. Ala. 1963); Harvest v.

Board of Public Instruction of Manatee County, 312 F.

Supp. 269 (M.D. Fla. 1970).

The appellants’ argument that the State Board o f Ed

ucation, Superintendent of Public Instruction and other

state officers are not properly named as defendants is

plainly without merit for it was undisputed that they

threatened to interfere with implementation of the de

segregation order in Charlotte in reliance upon the anti

bussing law. Furthermore, these state officials share the

affirmative duty to bring about desegregation of the schools

with local officials. Godwin v. Johnston County Board of

Education, 301 F. Supp. 339 (E.D. N.C. 1969); Bryant v.

State Board of Assessment, 293 F. Supp. 1379 (E.D. N.C.

1968; three-judge court); cf. Lee v. Macon County Board

of Education, 267 F. Supp. 458 (M.D. Ala. 1967; three-judge

court), affirmed, sub nom. Wallace v. United States, 389

U.S. 215 (1967) (a state-wide school desegregation suit).

The anti-bussing law stands on no different footing than

the previous attempts to nullify the desegregation orders

of federal courts revealed in the cases cited above. The

efforts of state executive, legislative and judicial officers

to annul the judgments of the United States District Court

for the Western District of North Carolina in the Char-

lotte-Mecklenburg school case must be emphatically re

16

pudiated. As this Court made clear in Cooper v. Aaron,

358 U.S. 1, 17-19, it has been clearly settled law since

Marbury v. Madison (US) 1 Cranch 137, 177 that the

“ federal judiciary is supreme in the exposition of the law

of the Constitution.” The efforts of state officers in this

case to nullify the desegregation decrees merit no serious

consideration by this Court. Those actions were plainly

blameworthy and discreditable, and the district court was,

if anything, too mild in not issuing contempt citations or

condemning the obstructions of its orders in more explicit

terms. Although the cause has been set for oral argument

in this Court, we suggest that the case does not merit

such further consideration.

B. This Court Decided in Green v. County School Board of

New Kent County That School Boards Must Take Affirma

tive Action to Disestablish Dual Segregated School Systems

Section 115-176.1 is an attempt to prevent North Caro

lina school boards from performing their constitutional

duty to desegregate the public schools. Under Green v.

County School Board of New Kent County, 391 U.S. 430,

437-438 (1968), the school boards throughout the State of

North Carolina are “charged with the affirmative duty to

take whatever steps might be necessary to convert to a

unitary system in which racial discrimination would be

eliminated root and branch.” It is entirely obvious, that

as the court below held, school boards cannot effectively

eliminate racial segregation of pupils without considering

the race of pupils when planning new assignments. It is

also obvious that they must use the conventional tools of

school administration, including school bus systems, to

convert to unitary nonsegregated systems. Section 115-

176.1 attempts to severely disable North Carolina school

officials in dealing with state imposed racial segregation.

As the court below wrote:

17

A flat prohibition against assignment by race would,

as a practical matter, prevent school boards from

altering existing dual systems. Consequently, the stat

ute clearly contravenes the Supreme Court’s direction

that boards must take steps adequate to abolish dual

systems. (312 F. Supp. 503, 509-510.)

The decision of the district court holding that the anti

bussing law violates the equal protection clause is plainly

correct for the reasons stated in the opinion below (312

F. Supp. 503, 507-510). The judgment below should be

summarily affirmed.

II.

The Appeal Should Be Dismissed Because the Case

Was Not Required to Be Heard by a Three-Judge Court.

A. The Case Involved Primarily a Supremacy Clause Issue

and Thus no Three-Judge Court Was Required Under the

Doctrine of Swift & Co. v. Wickham

It is submitted that the Court does not have jurisdiction

of a direct appeal pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 1253 because

the case is not one required by any Act of Congress to be

heard by a three-judge district courts Jn Swift d Co. v.

Wickham, 382 U.S. 111 (1965)t|ftie"' Court held that 28

U.S.C. section 2281 did not require that a three-judge

court be convened to decide a claim based on the Su

premacy Clause of the Constitution that a state law was

invalid because it conflicted with an Act of Congress. We

think that there is no sound reason not to apply the Swift

doctrine and reach the same result in a case such as this

where a state law is alleged to be invalid under the Su

premacy Clause because it conflicts with the judgment of

a court of the United States. We believe that the same

considerations relating to the efficient operation of the

18

lower federal courts which were held dispositive in cases

where a state statute must be compared for conflict with

a federal statute apply equally where the comparison must

be made between the statute and the decrees of a federal

court.

In the circumstances of the Charlotte case a federal dis

trict judge was faced with a series of orders by state

judges purporting to rely upon a newly enacted state law

to forbid that which the district judge’s decisions had com

manded to be done. Similarly, state executive officers, de

fendants in the case, threatened to defy the federal court

orders in reliance upon the state law. In such a situation

the power of the single federal district judge to protect

his own orders should be entirely clear. There should be

no need to resort to a three-judge court to put down bla

tant defiance of a district judge’s orders by state officials.

B. The Anti-Bussing Law Is So Obviously Unconstitutional

That no Three-Judge Court Was Required

In Bailey v. Patterson, 369 U.S. 31, 33 (1962), this Court

held that when “prior decisions make frivolous any claim

that a state statute on its face is not unconstitutional.”

See also Turner v. Memphis, 369 U.S. 350, 353 (1962); cf.

Ex parte Poresky, 290 U.S. 30 (1933). We believe that

these principles apply in this case. For the reasons stated

by the court below in its opinion the challenged portions

of the ahti-bussing law are plainly in conflict with this

Court’s decision in Green v. County School Board of New

Kent County, 391 U.S. 430 (1968). This conflict was open

and obvious. Indeed, it was plainly intended. The state

legislature sought to insulate a freedom of choice basis

for desegregation from federal court attack notwithstand

ing this Court’s decision that free choice plans may be

constitutionally inadequate. The legislature openly sought

to prevent the school board from taking effective action

19

to disestablish the dual system. A three-judge court should

not be required to deal with such a patent evasion of the

Brown decision after sixteen years of such experimenta

tion with disobedience. Efforts to obstruct Brown should

be dealt with in the most efficient manner possible with

out the necessity of convening three-judge courts.

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons it is respectfully submitted

that the judgment below should be affirmed, or, in the al

ternative, that the appeal should be dismissed.

Jack Greenberg

James M. Nabrit, III

N orman J. Chachkxn

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

J. L eV onne Chambers

A dam Stein

Chambers, Stein, Ferguson & Lanning

216 West Tenth Street

Charlotte, North Carolina 28202

C. 0. Pearson

203% East Chapel Hill Street

Durham, North Carolina 27702

Attorneys for Appellees

MEILEN PRESS INC. — N, Y. C. •< !£> 219