Wolfe v. North Carolina Brief on the Merits

Public Court Documents

October 5, 1959

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Wolfe v. North Carolina Brief on the Merits, 1959. 5000986c-c99a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/7bbf1a52-250c-4e82-bff3-cb2cc9da6b37/wolfe-v-north-carolina-brief-on-the-merits. Accessed February 15, 2026.

Copied!

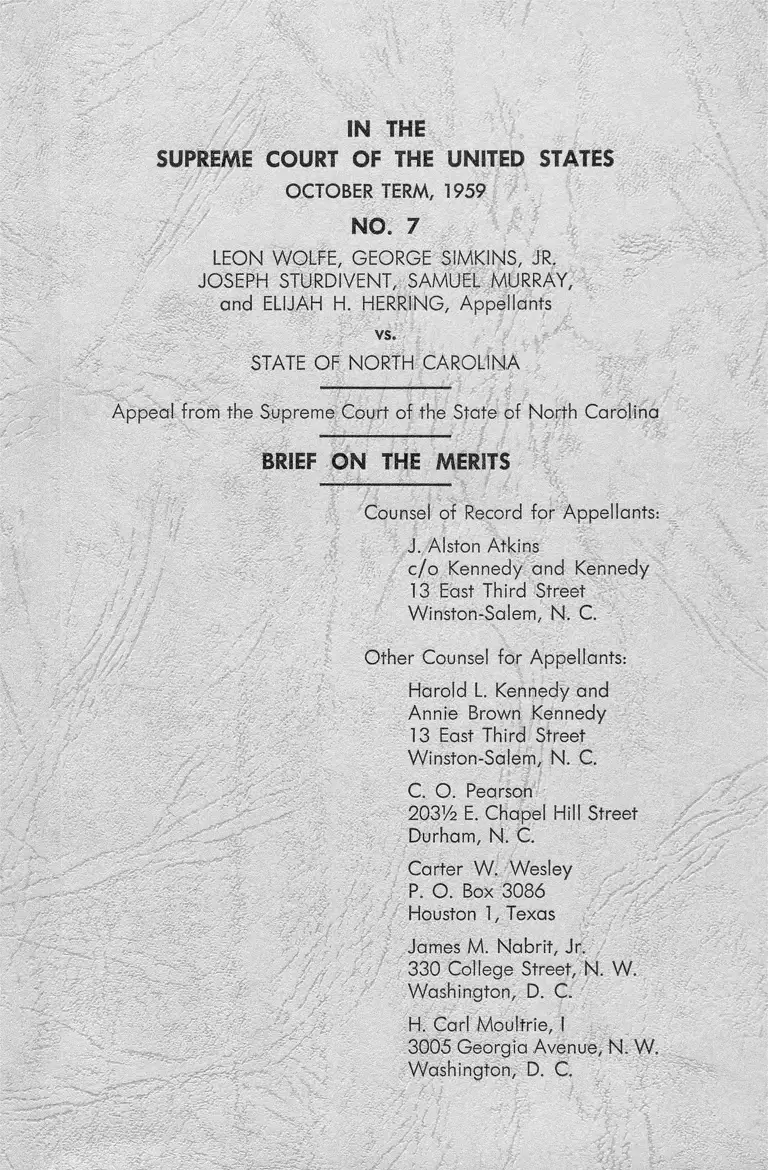

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

OCTOBER TERM, 1959

NO. 7

LEON W OLFE, GEORGE S IM KIN S, JR.

JOSEPH STURD IVEN T, SAMUEL MURRAY,

and ELIJAH H. HERRING, Appellants

vs.

STA TE OF NORTH CAROLINA

Appeal from the Supreme Court of the State of North Carolina

BRIEF ON THE MERITS

Counsel of Record for Appellants:

J. Alston Atkins

c/o Kennedy and Kennedy

13 East Third Street

Winston-Salem, N. C.

Other Counsel for Appellants:

Harold L. Kennedy and

Annie Brown Kennedy

13 East Third Street

Winston-Salem, N. C.

C. O. Pearson

20372 E. Chapel H ill Street

Durham, N. C.

Carter W . Wesley

P. O. Box 3086

Houston 1, Texas

James M. Nabrit, Jr.

330 College Street, N. W.

Washington, D. C.

H. Carl Moultrie, I

3005 Georgia Avenue, N. W.

Washington, D. C,

INDEX

Pages

Opinions in Court Below ........................................................ 1

Grounds of Jurisdiction ............................................. -........... 1- 2

State Statute Involved ............................................................. 2

Provisions of U. S. Constitution Involved ............................ 3

Questions Presented by Th is Appeal:

The Supremacy Clause Questions .............................. 3- 4

The Fourteenth Amendment Questions:

Under the Equal Protection Clause .................. 4- 5

Under the Due Process Clause ............................ 5

The Question of Judicial Notice................................... 5- 6

Statement of the Case ........................................................ .- 6-16

Summary of Argument:

On the Question of Jurisdiction ................................... 16-17

On the Merits:

Under the Supremacy C lause.............................. 18

Under the Fourteenth Amendment.................... 18-19

The Question of Judicial Notice ................................... 19

Argument I, The Question of Jurisdiction:

Raising of Federal Questions Be low ..........-................ 19-25

Actions of Courts Below on Federal Questions......... 25-26

Jurisdiction of U. S. Supreme Court:

Regarding Federal Questions in Pleadings...... 26-28

To Examine Record for Racial Discrimination .. 28-29

To Determine Validity of State Statute ........... 29

To Determine Equal Protection

Other Than Racial ................................................. 30

To Determine Questions of Due Process........... 30-32

Pages

To Determine Effect of Agreement

with United States ............................... ................. 32

To Protect Judgments of Federal Courts ......... 32-34

As Determined in Frank v Maryland ...... -........ 35-36

Since State Court Considered "The Merits" .... 36

As Determined in Irvin v Dowd ......................... 36-37

Legal Meaning of "The Merits" ......................... 37-38

Argument II, The Case on the Merits:

The Supremacy Clause Questions.-

(1) Does the State policy of making Gillespie

Park Golf Course "a private club for members

and invited guests only" collide unconstitutionally

with the policy of Federal law that this facility

must provide "the greatest degree of public use

fulness"? Is the State's criminal trespass statute

unconstitutional as applied in this case, because

it seeks to implement such a State policy that is in

direct conflict with Federal law? .............................. 38-41

(2) Can the State constitutionally avoid or vitiate

the agreement made with the United States by its

agencies, City of Greensboro and Greensboro

City Board of Education, that during its useful life

this golf course would be operated "fo r the use

and benefit of the public" and would not "be

leased, sold, donated, or otherwise disposed of

to a private individual or corporation, or quasi

public corporation"? Is the State's criminal tres

pass statute unconstitutional as applied in this

case, because it seeks to implement avoidance by

the State's agencies of their agreement with the

United States that this golf course would be thus

operated? ...................................................................... 41-43

(3) Can the State constitutionally make a crime

out of identical acts and conduct which the Fed-

ii

Pages

erai Courts have held to be protected by the

Constitution of the United States, and make law

ful acts of the State's agencies which the Federal

Courts have held to have been "unlaw fully" com

mitted against the "constitutional rights" of the

appellants? Is the State's criminal trespass statute

unconstitutional as applied in this case, because

it renders ineffectual the judgments of the United

States Courts? ............................ ............................... . 43-50

The State was constitutionally a party to the

Federal Court proceedings ................... ................. 46-48

Question of offering the Federal Court records

in evidence ..................................................... ............. 48-50

The Fourteenth Amendment Questions:

The "Equal Protection of the Laws" Questions:

(1) Does the record show racial discrimination

against appellants in the use of Gillespie Park

Golf Course (a) by the "facts" in the "published

opinion" of the Federal Court, which the State

Supreme Court said were known to the state

courts? or (b) by the Declaratory Judgment of the

Federal Court, which was alleged verbatim in the

Motion to Set Aside the Verdict and which was

not denied or controverted by the appellee State

in any way? or (c) within the "ru le of exclusion"

established by the decisions of this Court? Is the

State's criminal trespass statute unconstitutional

as applied in this case, because it seeks to imple

ment and make good racial discrimination?........ 50-55

(2) Does the "lack of standards in the license-issu

ing practice" for playing on Gillespie Park Golf

Course constitute "a denial of equal protection"

without regard to racial discrimination, within the

meaning of the decisions of this Court? Is the

State's criminal trespass statute unconstitutional

iii

Pages

as applied in this case, because it seeks to make

lawful such "lack of standards"? ............................ 55-59

The "Due Process of Law" Questions ....................... 59-71

(1) Do the State rules in this case which closed

the mouths to the truth of certain key witnesses

violate the justice and fundamental fairness which

the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amend

ment commands of the States in criminal prosecu

tions? Is the State's criminal trespass statute un

constitutional as applied in this case, because

it seeks to implement and make lawful such im

pediments to the discovery of truth? .................... 60-65

(2) The Supreme Court of North Carolina having

for the very first time held in this case that this

criminal trespass statute applies also to public

lands, and not just to lands "privately held," does

the judgment in this case send each of the appel

lants "to jail for a crime he could not with reas

onable certainty know he was committing"? ...... 65-67

(3) Do the multiple criminal proceedings against

appellants in this case reach the areas which the

Due Process Clause forb ids?................... ................. 67-71

Argument III, The Question of Judicial Notice.................. 72-79

Documents Representing Federal

Court Proceedings ........... ...... ........................................ 72-73

Documents Which Represent Federal Law ................ 73-74

Judicial Notice in Applications of

Federal Law ............................................................ 75

Judicial Notice of Public Documents ......................... 75-76

Principles and Philosophy of Judicial Notice ......... 76-77

Conclusion ................................................................................. 77-79

Appendixes ............................................................................... 80-98

iv

TABLE OF CASES

Allied Stores etc. v Bowers,__US__ , 3 L ed 2d 480 .... 27, 36

36

Angel v Buliington, 330 US 183 ................................................. 34

Ashcraft v Tennessee, 322 US 143 .......................... ................. 28

Aycock v Richardson, 247 NC 234 ........... ............................... 50

Bartkus v Illinois, — US— , 3 L ed 2d 684 ................................ 59

Bell v Hood, 327 US 678 ............................................................. 38

Bibb v Navajo Freight Lines,__US__ , 3 L ed 2d 1003 ......... 12

Bland Lumber Co. v National Labor Relations Board,

177 Fed 2d 555 ...................................................................... 32

Bonham v Craig, 80 NC 224 ..................................................... 25

Bowles v United States, 319 US 33 .................................. 75, 77

Brock v North Carolina, 344 US 424 ............................ 5, 31, 67,

70, 71

Brown v Board of Education, 344 US 1 ................................... 72

Brown v Western Ry of Alabama, 338 US 294 ............. 27, 36

Capital Service, Inc. v National Labor Relations Board,

347 US 501 ................................................................................ 32

City of Greensboro v Simkins, 246 Fed 2d 425 .................. 6, 9

Clearfield Trust Co. v United States, 318 US 363 ............. .... 40

Cooper v Aaron, 358 US 1 ..................................... . 45, 46, 47

Eubanks v Louisiana, 356 US 584 ............................................. 51

Frank v Maryland, US— , 3 L ed 2d 877 .................... 35, 36

Garner v Teamsters etc., 346 US 485 .............................. 48, 74

Haley v Ohio, 332 US 596 ........................ ................................ 43

Hawkins v United States, US— , 3 L ed 2d 125 ........ 60, 65

Pages

Hernandez v Texas, 347 US 475 ....................................... 4, 51

Hoag v New Jersey, 356 US 464 ........................ ........ 5, 31, 67

Irvin v Dowd, _ U S _ , 3 L ed 2d 900 ....................... 36, 37, 73

Ivanhoe Irrigation Dist. v McCracken, 357 US 275 ___ 40, 41

Jackson v Carter O il Co., 179 Fed 2d 524 ........................... 32

Jacksonville Blow Pipe Co. v Reconstruction Finance

Corp., 244 Fed 2d 394 ........................................ ................. 32

Leiter Minerals, Inc. v United States, 352 US 220 ............ ..... 32

L illy v Grand Trunk Western R. R. Co., 317 US 481 .... 40, 75

Local 24 etc. v O live r,__US__ , 3 L ed 2d 3 1 2 .................... 41

Mangum v Atlantic Coast Line Ry. Co., 188 NC 689 .......... 74

Marsh v Alabama, 326 US 501 ..... 29

Mason v Commissioners of Moore, 229 NC 626 ___________ 50

M iller v Arkansas, 352 US 187 ................................. ........ 40, 41

NAACP v Alabama, 357 US 449 ................. ........... ................. 66

Napue v Illin o is ,__US__ , 3 L ed 2d 1217 ..................... 11, 28

Niemotko v Maryland, 340 US 268 ...... ........... 5, 28, 30, 55,

56, 57, 58, 59, 66

Parker v Brown, 317 US 341 ........ ..... ........................ ...... ....... 76

Pocahontas Terminal Corp. v Portland Bldg. & Const.

Trades Council, 93 Fed Supp 2 1 7 .................... ......... 73, 74

Public Utilities Commission v United States, 355 US 534 ___ 47

Raley v O h io ,__US__ , 3 L ed 2d 1344 ____________ 3, 4, 59

Schulte v Gangi, 328 US 1 0 8 ..................................... ................ 76

Scull v V irg in ia ,__US__ , 3 L ed 2d 865 .................. 5, 31, 65

Shelley v Kraemer, 334 US 1 ................................................ . 58

vi

Pages

Pages

Simkins et ai. v City of Greensboro, et a!.,

149 Fed Supp 562 .........— .................... 9, 11, 12, 13, 14,

15, 18, 20, 21, 22,

23, 24, 30, 32, 43,

44, 46, 49, 51, 52,

54, 61, 67, 77, 78

Southern Pacific Company v Steward, 245 US 359 ----- 42, 74

State v Best, 111 NC 638 --------- ---- —........— .................. -...... 35

State v Clyburn, 247 NC 455 -------------------------- —- 5, 65, 66

State v Cooke et al., 246 NC 518 ............. .................. 1, 9, 10,

68, 70

State v Cooke et ai., 248 NC 485 ....... ........... -....................... 1

State v Council, 129 NC 371 (511) ..................................... 2, 50

State v Godwin, 5 Iredell (NC) 401 ................... -.......- ........... 35

State v Smith, 129 NC 546 ........................................................ 69

State v W illiam s, 151 NC 660 .....................................-............. 69

Staub v City of Baxley, 355 US 313 .....-..................... ---- 26, 36

Thomason v Cooper, 254 Fed 2d 808 - .....—.................. 33, 47

Tomkins v Missouri, 323 US 485 ....................................-........... 25

United States v County of Allegheny, 322 US 174 ....... . 42, 43

United States v John J. Felin Co., 334 US 624 ...........—........ 73

United States v Reynolds, 345 US 1 — .......................... 60, 65

W ells v United States, 318 US 257 ...... .....................- ........— 72

W illiam s v Georgia, 349 US 375 ...........................................— 50

W olf v Colorado, 338 US 25 ------------ ------- —......... -........ 59, 65

Zahn v Transamerica Corporation, 162 Fed 2d 36 ............. 75

vii

C O N STITUTIO N OF UN ITED STA TES

Pages

Article VI, Paragraph 2 ................................ 3, 17, 18, 19, 20,

38-50, 73, 74, 77

Fourteenth Amendment................................... 3, 17, 18, 20, 22,

44, 45, 50-71, 78

FEDERAL S TA TU TES

28 USC 1257 (2) ...................................................... 2, 17, 38, 77

28 USC 2103 ................................................... 2, 17, 38, 77

28 USC 2201 ........................................................................... 47, 74

28 USC 2283 ..................................... ..................................... 32, 33

53 Stat 927, Chap 252 ................... ............................... 6, 38, 39

W PA RULES AND REGULATIONS

Manual of Rules and Regulations, Library of Congress

Book HD 3881 .A58 ........................................................ 3, 39

GENERAL STA TU TES OF NO RTH CAROLINA (1953)

Section 1-159 .................................................................................. 25

Section 7-64 .......................... .............................. ..................... 69

Section 14-134 ...................................................... 2, 4, 5, 10, 12,

17, 18, 19, 24, 31,

38, 44, 47, 51, 77, 78

TEX TS

By-Laws, Gillespie Park Golf Club, Inc ............................ 58, 59

Certificate of Clerk, Supreme Court of North Carolina .. 2, 50

"Evidence-Cases and Materials"—Morgan, Maguire and

Weinstein (1957)

57 Harvard Law Review—"Judicial Notice"

76

76

2 Stanford Law Review—"Sense and Nonsense About

Pages

Judicial Notice" ...................................................................... 76

"The North Carolina Guide"—Robinson (1955) .................... 52

APPENDIXES

1 (a), 1(b) and 1 (c) ................................................. 6, 7, 42, 52

2 (a), 2 (b), 2 (c), 2 (d), 2 (e) and 2 (f) ............................ 16, 53

2 (g) ........................................................................... 8, 16, 53, 55

3 (a), 3 (b), 3 (c), 3 (d), 3 (e), 3 (f),

3 (g), 3 (h), 3 (i) ............................................ 39, 40, 41, 52

4 (a) and 4 (b) — ............................... .......... -...................... 49, 77

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF TH E UN ITED STA TES

October Term, 1959

No. 7

Leon Wolfe, George Simkins, Jr.,

Joseph Sturdivent, Samuel Murray, and Elijah H. Herring

Appellants

v

State of North Carolina

Appeal from the Supreme Court of the State of North Carolina

BRIEF ON THE MERITS

This Court having, on January 12, 1959, entered an order

postponing further consideration of the question of jurisdic

tion to the hearing of the case on the merits (R 140), appel

lants file this Brief on the Merits pursuant to Rules 40 and 41

of the Revised Rules of this Court.

(a) Opinions in the Court Below

The Opinion of the Supreme Court of North Carolina de

livered upon rendering the judgment here appealed from is

reported in State v Cooke et al., 248 NC 485, 103 SE 2d 846.

(R 107) That Court's Opinion upon a former trial upon another

set of warrants charging the identical trespass upon the munici

pal Gillespie Park Golf Course is reported in State v Cooke et

al., 246 NC 518, 98 SE 2d 885. (Page 55 of Appellants' State

ment as to Jurisdiction)

(b) Grounds of Jurisdiction

This is a criminal prosecution commenced in the Munici

pal-County Court of Greensboro, North Carolina, alleging a

1

simple trespass by appellants upon the municipal Gillespie

Park Golf Course. The warrants were issued under Section 14-

134 of the General Statutes of North Carolina (1953), which

appellants contend is unconstitutional under the Federal Con

stitution as upheld and construed and applied in this case.

The Judgment of the Supreme Court of North Carolina

appealed from was entered on June 4, 1958. (R 118) The

sentence involved is 15 days in jail for each of appellants.

(R 26-27)

No Petition for Rehearing in a criminal case is permitted

in the Supreme Court of North Carolina. State v Council, 129

NC 371 (511), 39 SE 814. See also the Certificate of the Clerk

of that Court. (R 139) Notice of Appeal to this Court was filed

in the Supreme Court of North Carolina on August 27, 1958.

(R 132) Appellants filed the Record and their Statement as to

Jurisdiction and docketed the case in this Court on October

22, 1958, becoming No. 466 of the October Term, 1958.

Appellants believe that this Court has jurisdiction of this

appeal under 28 USC 1257 (2). However, appellants have

prayed in their Statement as to Jurisdiction and also in their

Brief Opposing the Motion to Dismiss, and here renew that

prayer, that if they should be mistaken in this belief, then that

the appeal papers be treated as a Petition for Certiorari under

28 USC 2103 and that such Petition be granted.

(c) State Statute Involved

The validity under the Constitution of the United States

of Section 14-134 of the General Statutes of North Carolina

(1953), as upheld and construed and applied by the State

Courts to convict the appellants, is drawn in question upon

this appeal, the Supreme Court of North Carolina having

necessarily sustained said Statute's validity, said section read

ing:

" I f any person, after being forbidden to do so, shall

go or enter upon the lands of another without a license

therefor, he shall be guilty of a misdemeanor and on con

viction shall be fined not exceeding fifty dollars or im

prisoned not more than thirty days."

(c) Provisions of U. S. Constitution Involved

The provisions of the Constitution of the United States

which appellants contend are offended by the above-quoted

State statute, as upheld and construed and applied in this

case, are the following:

Article VI, Second Paragraph

"Th is Constitution, and the Laws of the United States

which shall be made in Pursuance thereof; and all Jreaties

made, or which shall be made, under the Authority of the

United States, shall be the supreme Law of the Land; and

the Judges in every State shall be bound thereby, any

Thing in the Constitution or Laws of any State to the Con

trary notwithstanding."

Fourteenth Amendment, Section 1

"A ll persons born or naturalized in the United States,

and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the

United States and of the State wherein they reside. No

State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge

the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United

States; nor shall any State deprive any person of life,

liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny

to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection

of the laws."

(d) Questions Presented by This Appeal

1. TH E SUPREMACY CLAUSE Q UESTIO N S

Is the State's criminal trespass statute (GS 14-134) uncon

stitutional "as applied"* in this case because:

(1) It seeks to implement the State's policy of making

Gillespie Park Golf Course "a private club" (R 44, 75) in direct

conflict with the policy of Federal law that this facility must

provide "the greatest degree of public usefulness" (Manual of

Rules and Regulations of W.P.A., Vol. II, Chap. 5, Page 1,

Library of Congress Book No. HD 3881.A58)?

*(See Raley v Ohio,___US___ 3 L ed 2d 1344, 1 3 5 3 ,____S C t__)

3

(2) It seeks to implement the State's effort to render in

effectual the agreement made by the State's agencies, City of

Greensboro and Greensboro City Board of Education, with the

United States, that during the useful life of this golf course it

would be operated "fo r the use and benefit of the public" and

would not "be leased, sold, donated, or otherwise disposed of

to a private individual or corporation, or quasi-public corpora

tion"? (See Fact No. 4, infra, and Appendixes 1(a), 1(b), and

1(c), Pages 80-82.)

(3) It seeks to implement the State's effort to make a crime

of identical acts and conduct which Federal Courts held

to be protected by the Constitution of the United States, and

make lawful acts of the State's agencies which the Federal

Courts have held to have been "unlaw fully" committed against

the "constitutional rights" of the appellants? (R 92)

II. TH E FO URTEEN TH AM ENDM ENT Q UESTIO N S

Is the State's criminal trespass statute (GS 14-134) uncon

stitutional "as applied"* in this case:

A. Under the Equal Protection Clause:

(1) Because it seeks to implement and make good the

practice of racial discrimination against appellants by the

State's agencies, as shown:

(a) By the "facts" in the "published opinion" of the United

States District Court for the Middle District of North Carolina,

which the Supreme Court of North Carolina said in its opinion

in this case were before the State courts (R 115)? (b) By the

Declaratory Judgment which was alleged verbatim in the Mo

tion To Set Aside the Verdict (R 92) and which allegation was

not controverted by the appellee State in any way? (c) Within

the "ru le of exclusion" established by the decisions of this Court

(e.g. Hernandez v Texas, 347 US 475, 480, 98 L ed 866, 871,

74 S Ct 667)?

(2) Because a "lack of standards" in the permission-grant

ing authority to play Gillespie Park Golf Course constitutes

*(See Raley v Ohio,— US__ , 3 L ed 2d 1344, 1353, S Ct )

4

"a denial of equal protection" without regard to racial dis

crimination, within the meaning of such cases as Niemotko v

Maryland, 340 US 268, 273, 95 L ed 267, 271, 71 S Ct 325?

B. Under the Due Process Clause:

(1) Because it seeks to implement a denial of due process

to appellants in this case:

(a) In that the State rules which closed the mouths to the

truth of certain key witnesses in this case violate the standards

of justice and fundamental fairness which the Due Process

Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment requires of States in

criminal prosecutions?

(b) In that the Supreme Court of North Carolina for the

very first time held in this case that this criminal trespass stat

ute (GS 14-134) applies also to public lands, and not just to

lands "privately held" (State v Clyburn, 247 NC 455, 458, 101

SE 2d 295), and the judgment here thus sends each of the

appellants "to jail for a crime he could not with reasonable

certainty know he was committing" (Scull v Virginia,— US

___, 3 L ed 2d 865, 871, 79 S Ct 838)?

(c) In that the multiple criminal proceedings against appel

lants in this case reach areas which the Due Process Clause

forbids, such as "fundamental unfairness" or "unduly harassing

an accused" (Hoag v New Jersey, 356 US 464, 467, 2 L ed 2d

913, 917, 78 S Ct 829), or "merely in order to allow a prose

cutor who has been incompetent or casual or even ineffective

to see if he cannot do better a second time" (Concurring Opin

ion in Brock v North Carolina, 344 US 424, 429, 97 L ed 456,

460, 73 S Ct 349)?

III. TH E Q UESTIO N OF JUDICIAL NOTICE

Insofar as this question should become important in this

case, appellants believe that it may cut across both the Ques

tion of Jurisdiction and the Case on the Merits. Therefore,

this Question of Judicial Notice is given separate treatment.

The Question Is: What documents or facts which may be

come germane to a decision of this case come within the prin

5

ciples under which this Court w ill take judicial notice of such

documents and facts?

STA TEM EN T OF THE CASE

Linder the Federal Emergency Relief Appropriation Act of

1939, 53 Stat 927, Ch 252, the appellee's agencies, City of

Greensboro and Greensboro City Board of Education, made

application for a WPA grant to build the golf course involved

in this case. The grant of 65 per cent of the cost was made and

the golf course was built, later becoming known as Gillespie

Park Golf Course. (See Appendix 1 (a), Page 80 and Fact No.

4, infra, Page 13.)

As required by said Federal Act and its authorized regula

tions, appellee's said agencies agreed with the United States

(1) that the golf course would be a public course, (2) that the

City of Greensboro would maintain and operate the golf

course during its useful life for the benefit of the public, and

(3) that during the useful life of the golf course it would not be

leased or otherwise disposed of to a private individual or

corporation or to a quasi-public corporation. (See Fact No. 4

infra, Page 13.)

Appellee State's agency, City of Greensboro, describes

the agreement with the United States Government on Pages

4, 7 and 8 of its "B rie f and Appendix" on appeal to the United

States Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit (No. 7450 on the

Docket of that Court, filed May 14, 1957) and photographic

reproductions of those pages are attached hereto as Appendix

1 (a), Appendix 1 (b), and Appendix 1 (c), respectively. The

District Court's Finding of Fact No. 20 and Conclusion of Law

No. 3, complained of by City of Greensboro on said pages,

but affirmed by the Court of Appeals, read as follows (See

pages 71, 76 of Appellants' Statement as to Jurisdiction.):

Finding of Fact No. 20: "On the 15th day of February,

1940, the defendant City of Greensboro and the defendant

Greensboro City Board of Education entered into an agree

ment with the Government of the United States for the con

struction of a golf course on land, part of which was owned by

the City of Greensboro and part by the Greensboro City Board

6

of Education, under which agreement the United States Gov

ernment provided 65% of the cost of constructing said golf

course. That in order to induce the United States Government

to provide 65% of the cost, the defendants City of Greens

boro and Greensboro City Board of Education agreed with the

United States Government that (1) this golf course was 'for

the use or benefit of the public.' (2) that the City of Greens

boro would maintain and operate said golf course for the use

and benefit of the public during the useful life of said golf

course and (3) that said golf course would not 'be leased,

sold, donated, or otherwise disposed of to a private individual

or corporation, or quasi-public corporation, during the useful

life of' said golf course. Said golf course became known as

the Gillespie Park Golf Course and is the golf course involved

in this action."

Conclusion of Law No. 3: "The said agreement between

the City of Greensboro, the Greensboro City Board of Educa

tion, and the United States Government imposed a duty upon

the defendants in this case to maintain and operate the Gil

lespie Park Golf Course during its useful life fo r the benefit of

public, including the Negro public, and that duty could not be

voided by the execution of the leases involved in this case."

The Greensboro City Board of Education leased its in

terests to the City of Greensboro, and from the time the golf

course was first opened until 1949 the City operated it ex

clusively for white citizens. (See Appendix 1 (a), Page 80, and

Fact No. 2 infra, Page 13.)

When Negro citizens of Greensboro in 1949 became insis

tent upon their right to use the golf course, they were formally

denied such right by resolutions of the Greensboro City Parks

and Recreation Commission and the Greensboro City Council.

(See infra, Page 61.) Thereupon, the Chairman of the City

Parks and Recreation Commission, John R. Hughes, became

the chief promoter of the organization of Gillespie Park Golf

Club, Inc., and the prime negotiator of leases of the golf course

from appellee's agencies, City of Greensboro and Greensboro

City Board of Education to Gillespie Park Golf Club, Inc.

(See infra, Page 62.) When City of Greensboro finally termi-

7

noted the leases, the City Council passed a resolution which

recited: "Whereas, The Gillespie Park Golf Club, Inc., was

created a non-profit, non-stock corporation and no person,

other than the City, has invested any funds in the corporation

or in the Golf Course and its equipment, and the Golf Club

has operated solely on funds derived from the use of the Golf

Course." (See Appendix 2 (g), Page 89.)

Subsequent to the making of the leases, the City of

Greensboro built nine additional holes to the golf course,

"which it had reserved the right to do under the lease," (See

Appendix 1 (a), Page 80.) Apparently in an effort to comply

with the "separate but equal" doctrine, the city built the 9-hole

Nocho Park Golf Course for Negroes. (See Fact No. 3 infra,

Page 13.)

On December 7, 1955, appellants sought permission to

play Gillespie Park Golf Course by paying greens fees, as

others were allowed, but were denied on the ground that " it

was a private club for members and invited guests only" (R 44).

Appellants placed the greens fees on the table and played

without permission of the Assistant Golf Pro in charge. (See

Facts No. 8 and No. 7 infra, Page 14.)

Appellants' conduct was entirely peaceful.—-See testimony

of State's witnesses: Deputy Sheriff Darby (R 49), Assistant Golf

Pro Bass (R 43), and Golf Pro Edwards (R 45). Appellants were

arrested upon warrants in Greensboro Municipal-County Court,

charging criminal trespass under said statute, GS 14-134.

The warrants alleged a trespass upon property of "G ille s

pie Park Golf Course." Appellants were tried and convicted.

Upon appeal to and trial de novo in the Superior Court of

Guilford County, the proof showed the name of the corpora

tion to be "Gillespie Park Golf Club, Inc.," instead of as set out

in the warrants, and amendment of the warrants accordingly

was allowed by the trial court. Appellants were convicted and

sentenced to 30 days in jail.

On appeal, the Supreme Court of North Carolina on its

own motion found a "fatal variance" between the name of the

corporation as alleged in the warrants and the name as shown

8

in the proof and amended warrants. Judgment was for this

reason arrested by the State Supreme Court. 246 NC 518.

While the case upon the first set of warrants was pending

on appeal in the Supreme Court of North Carolina, appellants

brought suit in the United States District Court for the Middle

District of North Carolina against appellee's agencies, City of

Greensboro, Greensboro City Board of Education, and Gilles

pie Park Golf Club, Inc. (Civil Case No. 1058), seeking a dec

laration of the rights of the parties under the Federal Constitu

tion with regard to the acts of appellants in playing golf on

said golf course, for which they had been convicted and sen

tenced in the State court. (See Motion to Quash, R 32-33, and

the Motion to Set Aside the Verdict, R 92)

After trial of the issues appellants prevailed, and the

Federal District Court filed its Opinion, Findings of Fact, Con

clusions of Law, and Declaratory Judgment, (See Pages 67-79,

appellants' Statement as to Jurisdiction), which Judgment de

clared that appellee's said agencies had " . . . unlawfully de

nied the plaintiffs as residents of the City of Greensboro, North

Carolina, the privileges of using the Gillespie Park Golf Course,

and that this was done solely because of the race and color of

the plaintiffs, and constitutes a denial of their constitutional

rights . . (R 92) The Opinion of the Federal District Court is

reported in Simkins et al. v City of Greensboro et al., 149 Fed

Supp 562. The Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit affirmed

in City of Greensboro et al. v Simkins et al., 246 Fed 2d 425.

Certiorari was not sought in this Court.

After said affirmance by the Court of Appeals, appellee

State caused indictments to be issued against appellants in the

Superior Court of Guilford County, charging the same alleged

trespass for the same alleged acts of playing golf. (R 36-42)

When the indictments were called for trial on December 2,

1957, the appellee State took a Nol Pros with leave in all of

the indictments. (R 43)

On the same day, December 2, 1957, appellee State

caused appellants to be arrested upon a second set of warrants

in the Greensboro Municipal-County Court, charging the same

alleged trespass for the same acts of playing golf. (R 2-25)

9

These are the warrants upon which the appellants stand

convicted and sentenced to 15 days in jail in this case.

Four of the warrants (R 2, 7, 10, 14) alleged the name of

corporation to be "Gillespie Park Club, Inc./' and only two of

the warrants (R 18, 22) alleged the name to be "Gillespie Park

Golf Club, Inc." But this "fatal variance" which the Supreme

Court of North Carolina noticed of its own motion in its first

opinion (246 NC 518), was not noticed at all in the State Su

preme Court's opinion directly involved on this appeal. (107-

118)

In apt time appellants filed in the Municipal-County Court

a Motion to Quash the warrants, alleging that they were

"Negro citizens of Greensboro," and "that GS 14-134 is here

by being unconstitutionally applied to these defendants on the

following grounds/'—setting out at some length appellants' con

tentions of violations of their rights under the Supremacy

Clause and the 14th Amendment of the Constitution of the

United States. (R 32-36) The motion was denied and appellants

were tried and convicted. (See R 108)

Upon appeal to and trial de novo in the Superior Court

of Guilford County, appellants in apt time renewed their

Motion to Quash, which was denied. (See R 108)

During their voir dire examinations, those members of the

Jury who had played on Gillespie Park Golf Course "stated

very frankly and freely in open court that they had played on

this course without any requirements except the payment of

greens fees." (R 93)

During the trial appellants sought on cross-examination of

appellee's witnesses to show the practice of racial discrimina

tion against Negroes in the operation of Gillespie Park Golf

Course, but appellee State's objection was sustained to this

type of question "as being immaterial." (R 45, 48)

Although John R. Hughes, President of Gillespie Park

Golf Club, Inc., was present in court, appellee State rested its

case without calling him as a witness. (R 50) When appellants

sought to call him as an adverse witness, this request was de

nied. (R 72) Appellants then put the witness Hughes on the

10

stand and sought to prove his testimony before the United

States District Court for the Middle District of North Carolina

in the Simkins Case, supra. But Mr. Hughes said: " I did not

testify for my association in the case of Simkins and others

against City of Greensboro, Board of Education and Gillespie

Park Golf Club, Inc."

Then counsel for appellants in the trial court said: "Q . Mr.

Hughes, I hold in my hand a document purporting to be a

transcript of the testimony in the case." (R 78) The objection of

appellee State was sustained, and the mouth of the president

of appellee's agency, whose employees were the prosecuting

witnesses in this case, was closed against the truth which was

elicited from him in the Federal District Court. That was in the

presence of the Jury.

When the Jury had retired, the following took place, as

appears on Page 79 of the Record:

"In the Absence of the Jury, Mr. John R. Hughes made the

following statement to the Court:

"M r. Hughes: If your Honor please, I would like to ask the

Reporter to read the question and answer which I gave in my

testimony, so that we may get the record straight.

"Question Read by Reporter as follows: 'Mr. Hughes, did

you testify for your Association in the case of Simkins and

others against the City of Greensboro, Board of Education, and

Gillespie Park Golf Club, Inc.?'

"M r. Hughes: In order that there may be no misunder

standing, I did testify in that case, but I was called as an ad

verse witness for the plaintiffs.

"Court: Do you wish to call Mr. Hughes back to the

stand?

’"M r. Marsh: No, your Honor."

Appellants were found guilty. Before they were sentenced

1 Under Napue v Illino is,___US___ 3 L ed 2d 1217, 1221____ S Ct___

it would appear that appellee's Solicitor in charge of the prosecution

had '"the responsibility and duty to correct'" the wrong impression which

the witness Hughes had given to the Jury.

11

appellants filed a Motion to Set Aside the Verdict (R 91-97), by

reference making certain allegations of the Motion to Quash

a part of the Motion to Set Aside the Verdict (R 91), including

the allegation (R 32) "that GS 14-134 is hereby being uncon

stitutionally applied to these defendants," for the reasons

under the Supremacy Clause and the 14th Amendment set out

in the Motion to Quash.

Appellants also set out verbatim in the Motion to Set

Aside the Verdict the Declaratory Judgment and Findings of

Fact No. 33 and No. 30 of the Federal District Court in the

Simkins Case, supra, (R 82, 94, 95-96), and in some detail

alleged violations of the Supremacy Clause and the 14th

Amendment under the facts and circumstances of the case. The

Motion to Set Aside the Verdict was denied. (R 97) On appeal

the Supreme Court of North Carolina upheld the trial court's

denial of the Motion to Quash (R 110) and of the Motion to

Set Aside the Verdict (R 118), and found "N o E rro r" in any of

the actions of the trial court. (R 118)

With reference to the Federal Court proceedings in the

Simkins Case, the Supreme Court of North Carolina said in its

Opinion in this case: "O ur knowledge of the facts in that case

is limited to what appears in the published opinion." (R 115)

2Pertinent "Facts" in said "published Opinion" follow, being

numbered for identification:

2The consideration which this Court gives to "facts" set out in the

Opinion of a United States District Court is indicated by the following

quotation from the case of Bibb v Navajo Freight Lines,___ US____, 3

L ed 2d 1003, 1007,___ S Ct___ :

"Illin o is introduced evidence seeking to establish that

contour mudguards had a decided safety factor in that they

prevented the throwing of debris into the faces of drivers of

passing cars and into the windshields of a following vehicle.

But the District Court in its opinion stated that it was 'con

clusively shown that the contour mud flap possesses no ad

vantages over the conventional or straight mud flap previously

required in Illino is and presently required in most of the states,'

(159 F Supp., at 388) and that 'there is rather convincing

testimony that use of the contour flap creates hazards pre

viously unknown to those using the highways.' Id. 159 F Supp

at 390 ." (Emphasis added.)

12

"Facts" in Federal District Court's Opinion

Fact No. 1—"The City of Greensboro and the Greensboro

City Board of Education concede that they cannot own and

operate the Gillespie Park Golf Course for the public and ex

clude the plaintiffs and other Negro citizens of Greensboro

from these privileges on account of their color." (149 Fed Supp

563).

Fact No. 2—"Although the golf course has been available

to the public for many years, whether by design or otherwise,

Negroes have been denied the enjoyment of the privilege."

(149 Fed Supp 563).

Fact No. 3—"The City of Greensboro, before Brown v

Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483, 74 S. Ct. 686, 98 L. Ed. 256,

in an effort to comply with Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U. S. 537,

16 S. Ct. 1138, 41 L. Ed. 256, erected in the City of Greens

boro a nine hole golf course for Negroes, known as Nocho

Park Golf Course, but it cannot be deemed the equivalent of

an 18 hole golf course like Gillespie Park course which was

restricted to white people." (149 Fed Supp 563).

Fact No. 4—"The Board of Education leased the land it

did not need for school purposes at the time to the City of

Greensboro. Through Works Progress Administration, which

furnished 65% of the cost, the City of Greensboro built the

last nine holes and agreed not to sell or lease for private use

this public property during its life of usefulness." (149 Fed

Supp 563).

Fact No. 5—"Some of the Negro citizens applied to the

City authorities for permission to play on the Gillespie Park

Course in 1949 and, because of opposition on the part of local

citizens against Negroes playing on the course, after some

negotiation, the City of Greensboro and City Board of Educa

tion entered into a lease contract whereby the entire golf

course was leased to Gillespie Park Golf Club, a non-profit

corporation which was organized solely fo r the purpose of tak

ing the lease and maintaining and operating the course as a

public golf course. G.S. N.C. Sec. 55-11." (149 Fed Supp 563)

Fact No. 6—"It is true the directors met with a quorum at

13

first and fixed $60 for annual membership which permitted

them to play without paying additional fees; also authorized

$1 membership who would pay $1.25 greens fees on holidays

and week-ends, and 750 on other days." (149 Fed Supp 563)

Fact No. 7—"The records of the corporation do not dis

close sufficient data to show if rules were really established

and enforced in respect to membership. The evidence does

clearly show that white people were allowed to play by paying

the greens fees without any questions and without being mem

bers. When Negroes asked to play, they were told they would

have to be members before they could play and it clearly

appears that there was no intention of permitting a Negro to

be a member or to allow him to play, solely because of his

being a Negro." (149 Fed Supp 563)

Fact No. 8—"The six plaintiffs presented themselves at the

desk of the man in charge of the golf course and laid down

750 each and asked to play, the first named plaintiff being a

dentist practicing his profession in Greensboro. But they were

not given permission to play. They insisted on their right to

play and played three holes. While playing the third hole, the

manager came and ordered them to leave and they refused to

go unless an officer arrested them. Whereupon the manager

swore out a warrant charging each with trespass upon which

they were tried, convicted and sentenced to 30 days in jail,

the statutory limit, from which an appeal is pending in the

Supreme Court of North Carolina." (149 Fed Supp 563).

Fact No. 9—"The Negroes have not only been denied the

privilege of the golf course but there is no intention on the part

of the defendants to permit them to do so unless they are com

pelled by order of court." (149 Fed Supp 563).

Fact No. 10—"The brief filed by the City of Greensboro

contains this significant statement in its statement of facts: 'In

December, 1955, six of ten plaintiffs in this action were denied

the use of Gillespie Park Golf Course by employees of Gilles

pie Park Golf Club, Inc. That same month the City Council in

structed the City Manager to proceed forthwith to receive bids

for the sale of Gillespie Park Course and upon such sale to

close the Nocho Park course. The land upon which the latter

14

is situated is to be used for governmental purposes and is not

to be soid/ The facts show that the city is still 'in the saddle'

so far as real control of the park is concerned and that the so-

called lease can be disregarded if and when the City decides

to do it. It also lends powerful weight to the inference that the

lease was resorted to in the first instance to evade the city's

duty not to discriminate against any of its citizens in the enjoy

ment in the use of the park." (149 Fed Supp 565).

Fact No. 11—"This golf club permits white people to play

without being members, or otherwise, except it requires the

prepayment of greens fees. The plaintiffs here paid their fees,

were forced off the course by being arrested for trespass.

Everybody knows this was done because the plaintiffs were

Negroes and for no other reason. This court cannot ignore it."

(149 Fed Supp 565).

Fact No. 12—"A decree will be entered declaring that

these plaintiffs have been denied on account of their color

equal privileges to use the golf course owned by the City

Board of Education and the City of Greensboro and operated

by the Gillespie Park Golf Club, and permanently restraining

the defendants from discriminating against plaintiffs and other

members of their race on account of color, so Song as the golf

course is owned by these agencies and operated for the

pleasure and health of the public, their agents, lessees, serv

ants and employees. The court invited counsel for the respec

tive parties to confer and to suggest to the court the best

practical way to make effective the decree, in the event the

plaintiffs prevailed. The final decree will be deferred a short

time to get the result of this conference." (149 Fed Supp 565).

Matters of Common or General Knowledge

There are some matters of common or general knowledge

in this case. They include the policy of racial exclusion of

Negroes from this golf course over the years of its operation,

as stated by Judge Hayes in Fact No. 2 and also in Fact No. 11,

supra, when he said of the exclusion of appellants: "Everybody

knows this was done because the plaintiffs [appellants here]

were Negroes and for no other reason. This court cannot ig

15

nore it." They also include the continued "in-the-saddle" con

nection with the golf course of appellee's State agency, City of

Greensboro, as stated by Judge Hayes in Fact No. 10, supra.

As substantiating matters of common or general knowl

edge pertinent to the issues involved in this case, appellants

attach hereto photographic reproductions of newspaper clip

pings, marked Appendixes 2 (a) to 2 (f) inclusive, and a photo

graphic reproduction of Page 190 of Minute Book No. 31 of

the Minutes of the City Council of the City of Greensboro,

North Carolina, marked Appendix 2 (g).

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

The following is a Summary of the Argument for appel

lants:

A. ON THE Q UESTIO N OF JURISDICTION

Appellants contend that Federal Questions involved were

raised in written Motions to Quash and to Set Aside the Ver

dict before the trial court; that appellee State did not answer

to deny or controvert any of the allegations of these Motions;

that under both State and Federal law these allegations should

have been taken as true; that the trial court denied these Mo

tions and this denial was sustained by the Supreme Court of

North Carolina.

Appellants contend that the Opinion of the Supreme

Court of North Carolina in this case shows that the Motions

which raised Federal Questions were denied on the merits, and

not on any ground of local procedure or practice. In this con

nection appellants contend that the Opinion of the Supreme

Court of North Carolina said in so many words that the State

Court was "considering the merits" of the case.

Appellants contend that, since Federal Questions were

raised in pleadings, under the decisions of this Court this

Court w ill decide for itself whether these Federal Questions

were well taken and this Court is not concluded by what the

State courts have decided with regard to these pleadings.

Appellants also contend that the North Carolina Supreme

16

Court's Opinion and judgment themselves deny to appellants

Federal constitutional rights, and that this denial could not be

called to the attention of the Supreme Court of North Carolina,

because no petition for rehearing is permitted in a criminal

case in that court.

Appellants contend that this Court has jurisdiction on ap

peal under 28 USC 1257 (2), because the written Motions be

fore the State courts alleged that the North Carolina criminal

trespass statute which is involved (GS 14-134), as construed

and applied in this case, violates the Supremacy Clause and

the 14th Amendment of the Constitution of the United States,

and that the decisions of the State courts were necessarily in

favor of the validity of this criminal trespass statute as con

strued and applied in this case.

Appellants contend that this Court has jurisdiction (1) to

examine the record to determine for itself whether racial dis

crimination in the use of the public golf course involved is

shown within the meaning of the decisions of this Court; (2) to

determine whether the record shows a denial of equal protec

tion without regard to racial discrimination,- (3) to determine

whether the fundamental fairness required by the Due Process

Clause has been denied to appellants in the trial of this case,-

(4) to determine whether or not the State Supreme Court's

judgment violates the agreement made by the State's agencies

with the United States covering the use of this golf course, or

whether the policy of the State law and the State court's

judgment collide with Federal law and regulations concerning

this golf course,- (5) to protect and effectuate the Declaratory

Judgment of the Federal Courts with regard to this golf course.

Appellants also point to the sim ilarity between the instant

case on the Question of Jurisdiction on appeal and certain

recent decisions of this Court taking jurisdiction on appeal.

However, appellants have prayed that, if they should be

mistaken in their belief that this Court has jurisdiction on ap

peal under 28 USC 1257 (2), that then the appeal papers be

treated as a Petition for Certiorari and that such Petition be

granted under 28 USC 2103.

17

B. ON TH E M ERITS

(1) Under the Supremacy Clause:

Appellants contend that the State's criminal trespass sta

tute (GS 14-134), as applied in this case, and the State Su

preme Court's judgment enforcing said statute violate the Su

premacy Clause in three particulars:

(a) They implement a policy which made Gillespie Park

Golf Course "a private club for members and invited guests

only," directly in conflict with an applicable Federal statute

and its supporting regulations which require that this golf

course "offer the greatest degree of public usefulness."

(b) They implement a policy violating an agreement by

the State's agencies with the United States that this golf

course would be operated for the benefit of the public and

would not "be leased, sold, donated, or otherwise disposed of

to a private individual or corporation, or quasi-public corpora

tion" during the useful life of said golf course.

(c) They implement a policy directly in conflict with a

Federal District Court's Declaratory Judgment in Simkins et

al. v City of Greensboro et al., 149 Fed Supp 562, as affirmed

by the Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit.

(2) Under the Fourteenth Amendment:

(a) Denial of Equal Protection.

Appellants contend that they have been denied the equal

protection of the laws in this case because (1) They were de

nied the use of Gillespie Park Golf Course because of race or

color, and (2) The record shows a denial of equal protection

because of a "lack of standards" in the permission-granting

authority for use of the golf course.

(b) Denial of Due Process of Law.

Appellants contend that they have been denied due proc

ess of law in this case in that (1) In the trial of this case the

State closed the mouths of certain key witnesses to the truth,

so that evidence material to appellants' defense was suppres

sed by the State's rules of evidence. (2) The Supreme Court

18

of North Carolina in this case for the first time held the crimi

nal trespass statute applied to the public lands of this golf

course, and not just to lands "privately held," as the State Su

preme Court had theretofore always held, and that appellants

therefore could not know "with reasonable certainty" that

they were violating this statute by playing on this public golf

course. (3) In this case three original, successive criminal pro

ceedings have been prosecuted by the State against appellants

in such a way as to amount to fundamental unfairness as for

bidden by the Due Process Clause of the 14th Amendment.

C. TH E Q UESTIO N OF JUDICIAL NOTICE

Appellants treat the question of Judicial Notice separately

because, insofar as this question may become important in this

case, appellants believe that it may cut across both the Ques

tion of Jurisdiction and The Case on the Merits.

Appellants take the position that the decisions of this

Court on the Question of Judicial Notice, as well as the reason

able bases of judicial notice, would require that judicial notice

be taken of any necessary documents or facts which were not

before the State courts as a matter of uncontroverted pleading

or otherwise.

ARGUMENT I

The Question of Jurisdiction

(a) Raising of Federal Questions Below—

The Federal questions were first raised by appellants in

the trial court by a Motion to Quash the warrants (R 32), and

then by a Motion to Set Aside the Verdict (R 91), the latter in

corporating certain allegations of the former by reference.

In both motions it was alleged that the North Carolina

criminal trespass statute (GS 14-134), under which appellants

stand convicted, was "being unconstitutionally applied" to ap

pellants in that, among other things:

"The State of North Carolina in this prosecution is, con

trary to the Supremacy Clause of the United States Constitu

19

tion, attempting to make a crime out of specific acts and,con

duct which both the United States District Court for the Middle

District of North Carolina and the United States Court of Ap

peals for the Fourth Circuit have specifically held to be pro

tected by the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the

United States." (R 32, 92)

Both motions also alleged:

"To permit this prosecution to proceed would be in effect

to nullify and render ineffectual the judgment and decree of

the United States Courts, contrary to the Supremacy Clause of

the United States Constitution and such prosecution would

violate the rights of these defendants and laws of the United

States, including the Fourteenth Amendment." (R 34, 92)

Both motions further alleged:

"Based upon the specific facts and conduct alleged by

the State to be a crime in this case, these defendants brought

Civil Action No. 1058 in the United States District Court for

the Middle District of North Carolina, praying for a declara

tory judgment and a decree enjoining the prosecution witnes-

es and the city of Greensboro and the Greensboro City Board

of Education from interfering with the defendants and all other

Negroes similarly situated from playing golf on the Gillespie

Park Golf Course.

"A full hearing was held before United States District

Judge Johnson J. Hayes, who on April 24, 1957, found specif

ically that the prosecuting witnesses and the City of Greens

boro had refused to permit these defendants to play golf

'primarily because of their color' (Finding of Fact No. 33), and

concluded as a matter of law that these defendants 'and other

Negroes similarly situated cannot be denied on account of

race, the equal privileges to the park, notwithstanding the

lease.' " (R 33, 92)

Both motions further alleged:

"These defendants have subpoenaed the Clerk of the

United States District Court for the Middle District of North

Carolina to bring to this trial the full record and judgment roll

20

in said case and respectfully request an opportunity to offer

this evidence upon the hearing of this motion.

"Defendants respectfully urge the Court to receive and

consider the record and judgment roll in the Federal case and

after such consideration to estop the State and the prosecuting

witnesses from proceeding further with this prosecution." (R

33, 92)

Both motions alleged the former trial upon the first set of

warrants and the indictments in the Superior Court, and al

leged that the trial upon the second set of warrants amounted

to double jeopardy in violation of the Federal Constitution.

(R 34-35, 92)

The Motion to Set Aside the Verdict alleged:

"That the Supremacy Clause (Article VI) of the Constitu

tion of the United States requires this Court to give effect to

and to enforce the judgments of the United States Courts cover

ing the subject matter of this prosecution, particularly the

'Decree and Injunction' of the United States District Court for

the Middle District of North Carolina, in Civil Case No. 1058,

in which these defendants were plaintiffs and Gillespie Park

Golf Club, Inc., was one of the defendants, covering the identi

cal acts and conduct charged by the State to be a crime of

trespass in this case, said 'Decree and Injunction' reading in

part as follows:

" 'It is now ordered, adjudged and decreed that defend

ants HAVE UNLAW FULLY DENIED THE PLAINTIFFS as residents

of the City of Greensboro, North Carolina, the privileges of

using the Gillespie Park Golf Course, AND TH A T TH IS W A S

DONE SOLELY BECAUSE OF TH E RACE AND COLOR OF THE

PLAINTIFFS, and constitutes a denial of their constitutional

rights, and unless restrained will continue to deny plaintiffs and

others similiarly situated.' (Emphasis added.)

"That the State of North Carolina and its jury in this case

undertake to find to be criminal the identical acts and con

duct whch said 'Decree and Injunction' holds to be protected

by the Constitution of the United States, and further undertake

to find to have been lawfully done, that which said 'Decree

21

and Injunction' holds was 'unlawfully' done, and that to permit

said verdict to stand and to punish these defendants on the

basis of said verdict would nullify and render ineffectual the

rights of these defendants which said 'decree and injunction'

holds to be guaranteed and protected by the Constitution and

laws of the United States, including the due process and equal

protection clauses of the 14th Amendment." (R 92)

Said Motion to Set Aside the Verdict quoted Fact No.. 11,

supra, page 15, from the Opinion of Judge Hayes, and follow

ed with this request of the trial Court:

"Defendants respectfully request this Court to take judicial

notice of this matter of common knowledge pertaining to this

public golf course owned and operated by their agency by the

City of Greensboro and the Greensboro City Board of Educa

tion. That this matter of common knowledge about the Gilles

pie Park Golf Course was spoken truly and not idly by Judge

Hayes when he wrote that 'everybody knows' it, was shown by

Jurors in this case in their answers to questions touching their

qualifications. Those who had played on Gillespie Park Golf

Course stated very frankly and freely in open court that they

had played on this course without any requirements except the

payment of greens fees. Defendants respectfully suggest that,

if any confirmation of Judge Hayes' statement that this was

common knowledge which 'everybody knows' is necessary it

is found in these statements of the Jurors in this case." (R 93)

The Motion to Set Aside the Verdict also alleged:

"Defendants respectfully suggest to the Court that to per

mit this verdict to stand under these circumstances would vio

late the rights of these defendants under the Constitution and

laws of the United States, including the due process and equal

protection clauses of the 14th Amendment." (R 93)

The Motion to Set Aside the Verdict also alleged:

"That said 'Decree and Injunction' of the United States

District Court for the Middle District of North Carolina begins

as follows: 'This cause coming on for hearing and the Court

having heard the evidence and argument of counsel and care

fully considered the same and the briefs filed, and having

22

made the findings of fact and conclusions of law which appear

of record/

"Defendants respectfully suggest to the Court that this

reference in said 'Decree and Injunction' to the findings of

fact and conclusions of law which appear of record makes

them a part of the 'Decree and Injunction' just as if written

out therein in fu ll; and for this reason and also because said

findings of fact and conclusions of law are a part of the record

and judgment roll in said case in the United States District

Court fo r the Middle District of North Carolina covering the

identical acts and conduct which said verdict seeks to make a

crime, the Supremacy Clause of the Constitution of the United

States lays a duty upon this Court to respect and give effect

to said findings of fact and conclusions of law, and especially

to Finding of Fact 33, which reads as follows:

" 'White citizens of Greensboro are given the privilege of

becoming permanent members by paying $60.00 per year

without greens fees and others not permanent members by pay

ing $1.00 per year and greens fees of $.75, except on holidays

and weekends, when it is more. On days other than holidays

and weekends when greens fees are $1.25 white citizens are

permitted to play without being members by paying the fees

above set forth and without paying the extra $1.00 and without

any questions being put to them. When the plaintiffs applied

to be given the same privilege they were refused on the

ground that they were not members but primarily because of

their color. Plaintiffs laid the greens fees on the table in the

club house, went out to play and after they had gotten to the

3rd hole the 'pro' in charge of the golf course ordered them

off and they insisted they had a right to play and would not

get off unless they were arrested by an officer, whereupon the

'pro' had them arrested and they were tried and convicted and

sentenced to imprisonment for a period of 30 days, which is the

maximum under the law for the State of North Carolina for

trespassing.'" (R 93-94)

The Motion to Set Aside the Verdict also alleged:

"That the evidence in this case and the instructions of the

Court to the Jury show that the land on which Gillespie Park

23

Golf Course is situated is public and not private property,

whereas GS 14-134, which is the North Carolina statute under

which the warrants were drawn in this case, is meant to cover

private property and not public property." (R 95)

"Defendants respectfully suggest to the Court that this

statute was never intended to apply to public lands or public

property, but was and is intended to apply solely and only to

private property, and that the lands and property and the pos

session alleged to have been invaded in this case was public

lands and property and the possession of an agency of the

City of Greensboro and the Greensboro City Board of Educa

tion, which held the title to said lands and property. In this

connection defendants respectfully call the Court's attention

to Finding of Fact No. 30 in said case in the United States

District Court for the Middle District of North Carolina:

" 'That the leases in this case undertook to turn over to a

corporation having no assets or income highly valuable in

come-producing property belonging to the City and the school

board, the chief officer and promoter of said corporation be

ing an official of the city, and the city having no prospect of

getting anything from said leases except out of the income

which the leased property was already bringing in, and with

the City reserving the right to put into the property further in

vestments from other sources than said income and that under

these circumstances said corporation was in fact an agency of

the City and the school board for the continued maintenance

and operation of the golf course for the convenience of the

citizens of Greensboro.' " (R 95-96)

The Motion to Set Aside the Verdict also alleged:

"Defendants further suggest to the Court that as citizens

and taxpayers of the City of Greensboro, these defendants

along with all other such citizens and taxpayers did have a

license to go upon said lands upon which said Golf Course

was situated, and that there is no evidence whatsoever in this

case that these defendants were 'without a license' to go upon

or to remain upon said lands, and that the absence of such a

license is an indispensable ingredient of the trespass establish

ed by GS 14-134." (R 96)

24

THE APPELLEE STA TE DID NO T ANSW ER OR DENY OR

CONTROVERT THE MOTION TO QUASH OR THE MOTION

TO SET ASIDE THE VERDICT, OR ANY OF THE ALLEGATIONS

CONTAINED IN EITHER MOTION.

The rule of pleading in North Carolina, both by statute

and also by decisions, is that where the allegations of a plead

ing are not answered or denied, the facts alleged must be

taken as true. GS 1-159. Bonham v Craig, 80 NC 224, 227.

Immediately after Section 1-159 of the official edition of

the General Statutes of North Carolina (1953) is the follow

ing: "Editor's Note.—The rule established by this section dis

posed of the necessity of submitting to the jury matters which

the law deems as admitted in the absence of denial."

The same rule applies in the decisions of this Court as to

allegations concerning Federal rights, which are not answered

or denied. Tomkins v Missouri, 323 US 485, 89 L ed 407, 65 S

Ct 370.

(b) Actions of Courts Below on Motions to Quash and to

Set Aside the Verdict—

The trial Court denied the Motion to Quash, the North

Carolina Supreme Court putting it this way: "Before pleading

to the merits in the Superior Court, defendants renewed their

motions to quash as originally made in the Municipal-County

Court. The motions made in apt time were overruled by the

court." (R 108)

In sustaining this action of the trial Court, the Supreme

Court of North Carolina said: "Since none of the reasons nor

all combined sufficed to sustain the motion to quash, the court

correctly overruled the motion and put defendants on trial for

the offense with which they were charged." (R 110)—(Emphasis

added.) It is clear to appellants that since the allegations of

the Motion to Quash were not answered or denied and thus

must be taken as true, the decision of the North Carolina Su

preme Court amounts to a holding that the motion did not

contain allegations sufficient to constitute a defense, under the

Constitution and laws of the United States, to the criminal tres

pass prosecution.

25

As to the Motion to Set Aside the Verdict, this too was

denied by the trial Court (R 97), and in sustaining this action

the Supreme Court of North Carolina said: "Defendants were

not, as a matter of right, entitled to have the verdict set aside."

(R 118) Since the allegations of the Motion to Set Aside the

Verdict were not answered or denied, it is likewise clear to

appellants that this action of the North Carolina Supreme

Court amounts to a holding that the motion did not contain

allegations sufficient to constitute a defense, under the Consti

tution and laws of the United States, to the criminal trespass

prosecution.

With regard to the question of Double Jeopardy, the Su

preme Court of North Carolina said: " It is manifest there is

here no double jeopardy." Appellants believe that this is a

clear decision of this question on the merits.

(c) Decisions of this Court Regarding Federal Questions

Raised in Pleadings—

The general rule was restated in the case of Staub v City

of Baxley, 355 US 313, 318, 2 L ed 2d 302, 309, 78 S Ct 277:

'"Whether a pleading sets up a sufficient right of action

or defense, grounded on the Constitution or a law of the

United States, is necessarily a question of federal law;

and where a case coming from a state court presents that

question, this Court must determine for itself the suffi

ciency of the allegations displaying the right or defense,

and is not concluded by the view taken of them by the

state court.' First Nat. Bank v Anderson, 269 US 341, 346,

70 L ed 295, 302, 46 S Ct 135, and cases cited. See also

Schuylkill Trust Co. v Pennsylvania, 296 US 113, 122, 123,

80 L ed 91, 98, 56 S Ct 31, and Lovell v G riffin, 303 US

444, 450, 82, L ed 949, 952, 58 S Ct 666. As Mr. Justice

Holmes said in Davis v Wechsler, 263 US 22, 24, 68 L

ed 143, 145, 44 S Ct 13, 'Whatever springes the State

may set for those who are endeavoring to assert rights

that the State confers, the assertion of federal rights,

when plainly and reasonably made, is not to be defeated

under the name of local practice.' Whether the constitu

tional rights asserted by the appellant were ' . . . given

26

due recognition by the [Court of Appeals] is a question as

to which the [appellant is] entitled to invoke our judg

ment, and this [she has] done in the appropriate way. It

therefore is within our province to inquire not only

whether the right was denied in express terms, but also

whether it was denied in substance and effect, as by put

ting forward non-federal grounds of decision that were

without any fa ir or substantial support . . . [for] if non-

federal grounds, plainly untenable, may be thus put fo r

ward successfully, our power to review easily may be

avoided/ Ward v Love County, 253 US 17, 22, 64 L ed

751, 758, 40 S Ct 419, and cases cited."

See also Allied Stores of Ohio v Bowers, ------US------ ,3 L ed

2d 480, 483, 79 S Ct 437, where it is stated that this principle

now " is settled."

In Brown v Western Railway of Alabama, 338 US 294,

295, 296, 94 L ed 100, 102, 103, 70 S Ct 105, a demurrer was

sustained to a complaint asserting Federal rights, and the

cause dismissed by the state courts. On certiorari, this Court

said of the conclusions of the Georgia Court of Appeals re

garding the complaint:

"The court reached the foregoing conclusions by follow

ing a Georgia rule of practice to construe pleading al

legations 'most strongly against the pleader.' "

" It is contended that this construction of the complaint

is binding on us. The argument is that while state courts

are without power to detract from 'substantive rights'

granted by Congress in FELA cases, they are free to fo l

low their own rules of 'practice' and 'procedure.' To what

extent rules of practice and procedure may themselves dig

into 'substantive rights' is a troublesome question at best

as is shown in the very case on which respondent relies.

Central Vermont R. Co. v. White, 238 US 507, 59 L ed

1433, 35 S Ct 865, Ann Cas 1916B 252, 9 NCCA 265.

Other cases in this Court point up the impossibility of lay

ing down a precise rule to distinguish 'substance' from

'procedure.' Fortunately, we need not attempt to do so.

A long series of cases previously decided, from which we

27

see no reason to depart, makes it our duty to construe

the allegations of this complaint ourselves in order to

determine whether petitioner has been denied a right of

trial granted him by Congress. This federal right cannot

be defeated by the forms of local practice . . . And we

cannot accept as final a state court's interpretation of al

legations in a complaint asserting it."

"Second. We hold that the allegations of the complaint

do set forth a cause of action which should not have been

dismissed."

(d) Jurisdiction to Examine th e Record to Determine

Whether or Not It Shows Racial Discrimination in This Case—

The appellee made quite a point in its Motion to Dismiss

that "The Question of Racial Discrimination in the Use of the

Golf Course Was Not Involved in This Case."

The jurisdiction of this Court to make such an examina

tion of the record in connection with appellants' assertion of

this Federal right seems to be well established. In Niemotko v

Maryland, 340 US 268, 271, 95 L ed 267, 270, 71 S Ct 325,

this Court said:

"In cases in which there is a claim of denial of rights

under the Federal Constitution, this Court is not bound by

the conclusions of lower courts, but will reexamine the

evidentiary basis on which those conclusions are found

ed."3