Abrams v. Johnson Brief for Appellants

Public Court Documents

September 8, 1994

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Abrams v. Johnson Brief for Appellants, 1994. dc501ac0-ab9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/7bda3217-1597-4df7-ac4c-9d05af421a21/abrams-v-johnson-brief-for-appellants. Accessed February 25, 2026.

Copied!

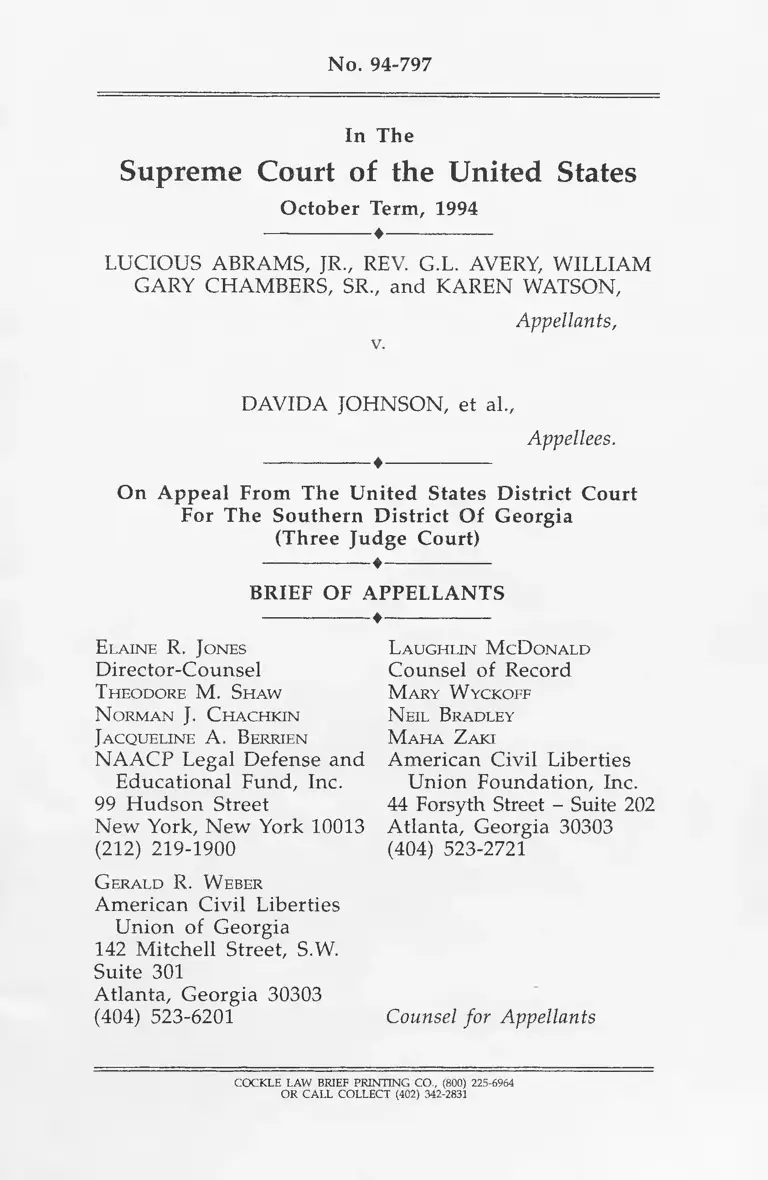

No. 94-797

In The

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1994

-----------------♦ -----------------

LUCIOUS ABRAMS, JR., REV. G.L. AVERY, WILLIAM

GARY CHAMBERS, SR., and KAREN WATSON,

Appellants,

v.

DAVID A JOHNSON, et al.,

♦

Appellees.

On Appeal From The United States District Court

For The Southern District Of Georgia

(Three Judge Court)

----------------- ♦ -----------------

BRIEF OF APPELLANTS

-----------------♦ -----------------

E la in e R. J o n es

Director-Counsel

T h eo d o r e M. S haw

N o rm a n J . C h a c h k in

J a c q u elin e A. B er r ien

NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10013

(212) 219-1900

G era ld R. W eber

American Civil Liberties

Union of Georgia

142 Mitchell Street, S.W.

Suite 301

Atlanta, Georgia 30303

(404) 523-6201

L a u g h lin M cD o n a ld

Counsel of Record

M a ry W yck o ff

N eil B ra dley

M a h a Z aki

American Civil Liberties

Union Foundation, Inc.

44 Forsyth Street - Suite 202

Atlanta, Georgia 30303

(404) 523-2721

Counsel for Appellants

COCKLE LAW BRIEF PRINTING CO., (800) 225-6964

OR CALL COLLECT (402) 342-2831

1

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

1. Whether plaintiffs, who suffered no dilution of

their voting strength or other "individual harm/' have

standing to challenge Georgia's congressional redistrict

ing, or are entitled to any remedy?

2. Whether plaintiffs satisfied the threshold test of

Shaw v. Reno of proving that Georgia's Eleventh Congres

sional District was so bizarre or irrational on its face that

it could only be understood as an effort to segregate

voters into separate districts on the basis of race?

3. Whether the three judge court erred in holding

that the racial community of interest shared by black

citizens in Georgia was barred from constitutional recog

nition, and that the consideration of race as a substantial

or motivating factor in congressional redistricting, with

out regard to district shape, automatically triggers strict

constitutional scrutiny?

4. Whether the court below erred in reviewing the

objection of the Attorney General under Section 5 of the

Voting Rights Act, 42 U.S.C. § 1973c, to the state's pro

posed congressional redistricting and in concluding that

the objection was improper, and that as a consequence the

state did not have a compelling interest in complying

with the objection?

5. Whether the lower court erred in ruling that the

state did not have a compelling interest in complying

with Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act, 42 U.S.C. § 1973,

or in remedying the effects of past discrimination in

congressional redistricting?

11

QUESTIONS PRESENTED - Continued

6. Whether, assuming a compelling or other requi

site state interest, the lower court erred in holding that

the state's plan was not narrowly tailored?

Ill

PARTIES TO THE PROCEEDING

The appellants are Lucious Abrams, Jr., Rev. G.L.

Avery, William Gary Chambers, Sr., and Karen Watson.

The appellees are Davida Johnson, Pam Burke, Henry

Zittrouer, George L. DeLoach, and George Seaton. The

defendants below were Zell Miller, Governor of Georgia,

Pierre Howard, Lieutenant Governor of Georgia, Thomas

Murphy, Speaker of the House of Representatives of

Georgia, and Max Cleland, Secretary of State of Georgia.

The United States of America was a defendant intervenor.

IV

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Questions Presented............... i

Parties to the Proceeding............. iii

Table of Authorities .......................................................... vi

Opinions Below ................. .............................................. 1

Jurisdiction.......................................................................... 1

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved. . . 2

Statement of the Case .................. 2

A. The Proceedings Below .................................... 2

B. Racial Discrimination and Bloc Voting in

G eorgia................................................................ 4

C. Discrim ination in Prior Congressional

Redistricting............................................ 10

1. The 1971 Plan .......................................... 10

2. The 1981 P la n ........................................... 11

D. 1991 Congressional Redistricting................. 13

1. The First P la n ..................... . ................ . . 16

2. The Second Plan....................................... 17

3. The Third P la n ......................................... 18

E. The Decision of the District Court.............. 23

Summary of Argument................. 29

Argument..................................... 30

I. Georgia's Congressional Redistricting Is not

Subject to Strict Scrutiny......................................... 30

A. The Eleventh District Is not Bizarre............. 36

V

TABLE OF CONTENTS - Continued

Page

B. Race Was not the Sole Motivating Factor.. 38

C. The Absence of H arm ...................................... 38

II. The Eleventh District Would Survive Strict Scru

tiny ......................................................... 42

A. The State's Interest Is Compelling.................. 42

B. The Eleventh District Is Narrowly Tailored .. 45

III. The Court Below Erred in Judicially Reviewing the

Section 5 Objection of the Attorney General . . . . . 46

IV. Plaintiffs Lack Standing.......................................... 48

Conclusion.................... ... .................................................... 50

Appendix...................................................................... .App. 1

VI

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Page

C a se s :

Allen v. State Board of Elections, 393 U.S. 544

(1969)....................................... ................................... 47

Allen v. Wright, 468 U.S. 737 (1984)............................. 49

Beer v. United States, 425 U.S. 130 (1976)............. 34, 43

Burton v. Sheheen, 793 F.2d 1329 (D.S.C. 1992).......... 37

Busbee v. Smith, 549 F.Supp. 494 (D.D.C. 1982),

aff'd 459 U.S. 1166 (1983) . . . . . . . 10, 11, 12, 13, 18, 26

Cane v. Worcester County, Maryland, 35 F.3d 921

(4th Cir. 1994).................................................................... 37

City of Richmond v. J.A. Croson, Co., 488 U.S. 469

(1989) ......................................................................41, 43, 44

City of Rome v. United States, 446 U.S. 156 (1980) . . . . 45

Clark v. Calhoun County, 21 F.3d 92 (5th Cir. 1994) . . . . 36

Concerned Citizens Committee v. Laurens County,

Georgia, Civ. No. CV392-033 (Sept. 8, 1994)........... 25

Davis v. Bandemer, 478 U.S. 109 (1986)................. 34, 39

Diamond v. Charles, 476 U.S. 54 (1986) ....................... 49

Fullilove v. Klutznick, 448 U.S. 448 (1980)................... 43

Gaffney v. Cummings, 412 U.S. 735 (1973)............. 31, 34

Georgia v. United States, 411 U.S. 526 (1973)............. 28

Gingles v. Edmisten, 590 F.Supp. 345 (E.D.N.C.

1984)............................... ...................................................... 41

Harris v. Bell, 562 F.2d 772 (D.C.Cir. 1977)................. 47

Holder v. Hall, 114 S.Ct. 2581 (1994)............................. 36

Johnson v. De Grandy, 114 S.Ct. 2647 (1994)..........45, 46

Karcher v. Daggett, 462 U.S. 725 (1983)....................... 46

vii

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES - Continued

Page

Katzenbach v. Morgan, 384 U.S. 641 (1966)................. 41

Lujan v. Defenders of Wildlife, 112 S.Ct. 2130

(1992).......................................................................... .. .48, 49

McDaniel v. Sanchez, 452 U.S. 130 (1981)..................... 47

Metro Broadcasting, Inc. v. F.C.C., 497 U.S. 547

(1990)............................................................................. 42. 43

Mobile v. Bolden, 446 U.S. 55 (1980)............................. 34

Morris v. Gressette, 432 U.S. 491 (1977)....................... 47

Perkins v. Matthews, 400 U.S. 379 (1971)..................... 46

Presley v. Etowah County Commission, 112 S.Ct.

820 (1992).................................................................... 43

Regents of the University of California v. Bakke,

438 U.S. 265 (1978).................................. 41

Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U.S. 533 (1964).......................... 32

Rogers v. Lodge, 458 U.S. 613 (1982)............................. 35

Shaw v. Hunt, 861 F.Supp. 408 (E.D.N.C. 1994)............. 44

Shaw v. Reno, 113 S.Ct. 2826 (1993).............................. passim

South Carolina v. Katzenbach, 383 U.S. 301 (1966)

.............................................................. ....................42, 44, 47

SRAC v. Theodore, 113 S.Ct. 2954 (1992)................. . . 37

Thornburg v. Gingles, 478 U.S. 30 (1986).... 14, 35, 41, 44

United Jewish Organizations of Williamsburg, Inc.

v. Carey, 430 U.S. 144 (1977)................... 32, 33, 34, 43

United States v. Board of Supervisors of Warren

County, Mississippi, 429 U.S. 642 (1977).......... 47

United States v. Paradise, 480 U.S. 149 (1987)............ 45

V l l l

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES - Continued

Page

Voinovich v. Quilter, 113 S.Ct 1149 (1993)................... 32

Warth v. Seldin, 422 U.S. 490 (1975). ......................... 49

Wilson v. Eu, 823 P.2d 545 (Cal. 1992)...................... . . 37

Wesberry v. Sanders, 376 U.S. 1 (1964)..................... . . 10

Wygant v. Board of Education, 476 U.S. 276 (1986)

. ...............................................................................41, 44, 45

C o n stitu tio n a l P r o v isio n s :

Article III, Section I of the Constitution of the

United States.......................... ......................................... 47

Fourteenth Amendment of the Constitution of the

United States............................................................ 2, 3, 31

S tatutes a n d R eg u la tio n s:

28 U.S.C. § 1253........................ ............................................. 2

Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act, 42 U.S.C. § 1973

........................................................... .......................2, 6, 35, 44

Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act, 42 U.S.C.

§ 1973c............................................................................ passim

28 C.F.R. § 51.29.............................................. - ................. 28

O th er A u th o r ities :

Aleinkoff and Issacharoff, "Race and Redistrict

ing: Drawing Constitutional Lines After Shaw v.

Reno," 92 Mich.L.Rev. 588 (1993).............................. 33

Barone and Ujifusa, The Almanac of American

Politics (1984).............................................................. 13, 40

IX

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES - Continued

Page

Barone, Ujifusa, and Matthews, The Almanac of

American Politics (1974)................................................. 11

Bositis, Redistricting and Representation: The Cre

ation of Majority-Minority Districts in the

South, The Evolving Party System and Some

Observations on the New Political Order (Joint

Center for Political and Economic Studies, 1995)

(forthcoming)........................................................................40

Dixon, "Fair Criteria and Procedure for Establish

ing Legislative Districts" in Representation and

Redistricting Issues (Grofman, Lijphart, McKay,

& Scarrow eds. 1982)............................................ 34

Grofman, "Criteria for Districting: A Social Sci

ence Perspective," 33 U.C.L.A.L.Rev. 77 (1985) . . . . 37

Pildes and Niemi, "Expressive Harms, 'Bizarre

District,' and Voting Rights: Evaluating Elec

tion-District Appearances after Shaw v. Reno,"

92 Mich.L.Rev. 483 (1993).................................... 33

S.Rep. No. 417, 97th Cong., 2d Sess. (1982). ................ 40

Voting Rights Act: Hearings Before the Subcomm.

on the Constitution of the Senate Comm, on the

Judiciary, 97th Cong., 2d Sess. (1982)...................... 40

No. 94-797

------- ---------

In The

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1994

............. ..... 4---------------

LUCIOUS ABRAMS, JR., REV. G. L. AVERY, WILLIAM

GARY CHAMBERS, SR., and KAREN WATSON,

Appellants,

v.

DAVIDA JOHNSON, et al„

Appellees.

-----------------♦ --------------- -

On Appeal From The United States District Court

For The Southern District Of Georgia

(Three Judge Court)

------------------------------- 4 . --------------------------------

BRIEF OF APPELLANTS

--------------- 4---------------

OPINIONS BELOW

The September 12, 1994 opinion of the three judge

court for the Southern District of Georgia (J.S.App. 1-102)

holding Georgia's Eleventh Congressional District uncon

stitutional is reported at 864 F.Supp. 1354. The June 14,

1994 order of the court denying the motion to dismiss for

lack of standing is unreported and appears at J.S.App. 103.

JURISDICTION

The opinion and order of the three judge district

court was entered on September 12, 1994. Appellants

1

2

filed their notice of appeal on September 14, 1994,

J.S.App. 112. Probable jurisdiction was noted on January

6, 1995. 63 U.S.L.W. 3499. The jurisdiction of this Court is

invoked under 28 U.S.C. § 1253.

CONSTITUTIONAL AND STATUTORY

PROVISIONS INVOLVED

The constitutional and statutory provisions involved

in the case are the equal protection clause of the Four

teenth Amendment of the Constitution of the United

States, and Sections 2 and 5 of the Voting Rights Act, 42

U.S.C. §§ 1973 and 1973c, the pertinent texts of which are

set out at J.S.App. 115-18.

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

A. The Proceedings Below.

Appellees, plaintiffs below, are white residents of

Georgia who challenged the state's 1990 congressional

redistricting on constitutional grounds. One of the plain

tiffs, George L. DeLoach, was an unsuccessful candidate

in the 1992 Democratic primary for the Eleventh Congres

sional District. Substitute Joint Submission of the Parties,

Exhibit A, Stipulations 44, 47 (hereinafter "Stip.");1 Trial

Transcript, Volume I, p. 5 (hereinafter "T.Vol.");

T.Vol.VI,53. The defendants below were Zell Miller, Gov

ernor of Georgia, Pierre Howard, Lieutenant Governor of

Georgia, Thomas Murphy, Speaker of the House of Repre

sentatives of Georgia, and Max Cleland, Secretary of State

1 The parties agreed as to the accuracy and m ateriality of

Stips. 1-73, and as to the accuracy but not the m ateriality of

Stips. 74-242.

3

of Georgia. Appellants, who were defendant intervenors

below (hereinafter "Abrams intervenors"), are a group of

black and white registered voters and residents of Geor

gia's Eleventh Congressional District. J.A. 2. The United

States of America was also a defendant intervenor.

Appellees brought this action on January 13, 1994,

alleging that "there is no explanation for the configura

tion of the Eleventh Congressional District except as an

expression of racial gerrymandering" in violation of Shaw

v. Reno, 113 S.Ct. 2826 (1993). Complaint, f 1. Plaintiffs

sought a declaration that the existing plan was uncon

stitutional, and an injunction requiring the state "to pre

pare a new redistricting plan." Complaint, p. 13.

The Abrams intervenors filed a motion to dismiss the

complaint because plaintiffs lacked standing. That motion

was denied without a hearing. J.S.App. 103, 111. Appel

lees filed a motion for a preliminary injunction seeking to

enjoin the state's congressional elections. Following a

hearing, the three judge court unanimously denied the

motion. J.A. 3. After trial on the merits a majority of the

district court held that the Eleventh District violated the

equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment

and permanently enjoined further elections in the district.

Circuit Judge Edmondson dissented. J.S.App. 1, 91-2.

Defendants Miller, Howard, and Cleland (hereinafter

"the state appellants"), the Abrams intervenors, and the

United States filed notices of appeal. J.A. 7-8. This Court

granted a stay upon separate applications of all appel

lants on September 23, 1994. The Abrams intervenors

filed a jurisdictional statement on November 2, 1994, and

the Court noted probable jurisdiction.

4

B. Racial Discrimination and Bloc Voting in Geor

gia.

Georgia has a long and continuing history of discrim

ination against blacks in all areas of life, particularly in

the electoral process and in congressional redistricting.

That history was so well documented the district court

ruled that evidence of discrimination "against black peo

ple in the State of Georgia need not be presented for

purposes of this case." J.S.App. 119; T.Vol.V,142. The

court took judicial notice that:

No one can deny that state and local govern

ments of Georgia in the past utilized wide

spread, pervasive practices to segregate the

races which had the effect of repressing black

citizens, individually and as a group.

. . . . By law, public schools and public housing

were segregated according to race. Public recre

ational facilities were segregated. Miscegenation

was prohibited. Ordinances required segrega

tion in public transportation, restaurants, hotels,

restrooms, theaters, and other such facilities,

even drinking fountains.

. . . . Public services were allocated along racial

lines. . . . In public employment, black workers

were often paid less than white workers for the

same job. In addition, methods of jury selection

were developed to exclude black people from

jury service.

Georgia's history on voting rights includes

discrimination against black citizens. From the

state's first Constitution - which barred blacks

from voting altogether - through recent times, the

state has employed various means of destroying

or diluting black voting strength. For example,

5

literacy tests (enacted as late as 1958) and prop

erty requirements were early means of exclud

ing large numbers of blacks from the voting

process. Also, white primaries unconstitu

tionally prevented blacks from voting in pri

mary elections at the state and county level.

Even after black citizens were provided

access to voting, the state used various means to

minimize their voting power. For example, until

1962 the county unit system was used to under

mine the voting strength of counties with large

black populations. Congressional districts have

been drawn in the past to discriminate against

black citizens by minimizing their voting poten

tial. State plans discriminated by packing an

excessive number of black citizens into a single

district or splitting large and contiguous groups

of black citizens between multiple districts.

j.S.App. 119-20 (emphasis added).2

A continuing pattern of racial discrimination in vot

ing in the state was so self-evident that the court refused

to accept as exhibits 17 consent decrees offered by the

Abrams intervenors entered between 1977 and 1993 in

Section 2 challenges brought against jurisdictions located

in whole or in part within the Eleventh District. The court

2 This history and its continuing effects are set out in

greater detail in the stipulations of the parties. See, e.g., Stips. 5

(whites registered in 1992 at 70.2% of voting age population;

blacks at 59.8% ), 76-103 (detailing the history of discrimination

in voting), 104-129 (describing segregation in educational insti

tutions), 130-134 (noting other forms of racial discrim ination),

135-55 (stipulating to racial disparities in income, education,

unem ploym ent, and poverty status). J.A. 9-33.

6

ruled that the decrees showed "a pattern of racial dis

crimination in Voting Rights that we have already taken

judicial notice of." T.Vol.VI,207.

While the decrees themselves were disallowed as

exhibits, the parties stipulated that "voting rights litiga

tion against the jurisdiction [located in whole or in part in

the present Eleventh District] resulted in changes in the

challenged electoral system(s) and/or judicial findings of

racial bloc voting" in Baldwin County, Milledgeviile,

Burke County, Effingham County, Butts County, Greene

County, Henry County, Jefferson County, Jenkins County,

Putnam County, Richmond County, Augusta, Screven

County, Twiggs County, Wilkes County, Waynesboro, and

Warrenton. Stip. 103.3 Courts have also made findings of

racial bloc voting in Bleckley, Carroll, Colquitt, DeKalb,

Dougherty, and Fulton Counties. Stip. 102.

The experts who testified were in agreement that

voting in Georgia is racially polarized. Dr. Allan Licht-

man, an expert for the United States, examined more than

300 elections spanning an approximately 20-year period.

T.Vol.V,200. He used the standard statistical techniques of

ecological regression and extreme case analysis, and

examined four sets, or levels, of black/white contests: (1)

county level contests throughout the state; (2) county

level contests within the Eleventh and Second Districts;

(3) six statewide elections partitioned within the bound

aries of the Eleventh and Second Districts; and, (4) the

3 The court also refused on sim ilar grounds of redundancy

to accept as exh ib its com pilations of Section 2 challenges

brought betw een 1974 and 1990 to at-large elections in 40 cities

and 57 counties throughout the state. T.Vol.VI,207.

7

1992 Eleventh and Second District elections. DOJ Exs. 24,

41; T.Vol.V,199.

As for level one, Dr. Lichtman's analysis showed

"strong" patterns of racial bloc voting, with blacks and

whites voting "overwhelmingly" for candidates of their

own race. DOJ Ex. 24, at 7-8. Level two and three analysis

also showed "strong" patterns of racial bloc voting. Id. at

8-9; T.Vol.V,202-03. In five of the six statewide contests in

the Eleventh District, at least 89% of blacks voted for

black candidates, and at least 74% of whites voted for

white candidates. DOJ Ex. 24, at 9. The exception to the

pattern was the 1992 Democratic primary for labor com

missioner in which the black candidate got 45% of the

white vote, and 96% of the black vote. In the ensuing

primary runoff the black candidate got only 26% of the

white vote, and 92% of the black vote. Id. at 14.

The 1992 primary and runoff in the Eleventh District

were also racially polarized. In the primary, which

involved one white and four black candidates, the white

candidate, DeLoach, was the first choice among whites

with 45% of the white vote. Cynthia McKinney, who was

the leading vote getter over all, was second among whites

with 20% of the white vote. Id. at 17; J.A. 22. In the runoff,

whites increased their support of DeLoach to 77%.

McKinney's white vote support increased to just 23%. Id.

Dr. Lichtman found voting patterns to be different in

statewide non-partisan judicial elections in which

appointed blacks ran as incumbents. He included these

contests in his report but treated them as having "mini

mal relevance." T.Vol.V7,228.

Dr. Lichtman also testified that blacks have a lower

socio-economic status than whites which was a barrier to

8

blacks' participation in the political process. T.Vol.V,206.

In the 1988 and 1992 presidential elections, black turnout

was 14-15% lower than white turnout. Id. at 208. In the

1992 elections in the Eleventh District, blacks were 51.5%

of all voters in the primary, but only 46-47% of voters in

the runoff. Id. at 212-13.

The state's expert, Dr. Joseph Katz, performed an

independent homogeneous precinct analysis to estimate

"average racial voting patterns." D.Ex.170; T.Vol.V,48,81.

He agreed that "[w]hites tend to vote for white candi

dates and blacks tend to vote for black candidates."

T.Vol.V,84. He concluded that whites vote for white can

didates in the range of 71-73%. Id. He did not believe a

black candidate had an even (50%) chance to win until a

district contained at least 50% of black registered voters.

Id. at 84-5. Dr. Katz also found judicial elections to be

"materially different" and that it would be "inappropri

ate" to use them in determining voting patterns in con

gressional elections. T.Vol.V,74,83.

The plaintiffs' expert, Dr. Ronald Weber, agreed there

was "some evidence" of racial polarization in voting.

T.Vol.IV,259. Taking into account judicial elections involv

ing appointed black incumbents, he did not think the

racial bloc voting was "very strong." Id. at 324.

In addition to these judicial findings and expert opin

ions, Representative Tyrone Brooks testified that

"[rjacially polarized voting in this state is a reality, and

we cannot run from that." T.Vol.IV,228. Lt. Governor

Howard testified that "there are still a lot of white voters

in Georgia, I'm sure, who won't vote for a black candi

date, and I'm sure that there are a lot of black [voters]

who won't vote for a white candidate." T.Vol.IV,220.

9

Intervenor Lucious Abrams, a Burke County farmer

who has worked in a number of local political campaigns,

testified that "a black will not win out of a majority white

district." T.Vol.VI,57. Kathleen Wilde, a former ACLU

staff attorney with extensive experience in voting rights

litigation in Georgia who was called as a witness by the

plaintiffs, said that "[rjacial polarization is sufficiently

• strong throughout the state that majority white districts

have historically elected white candidates, both state

wide and in districting systems." T.Vol.IV,106.

Of the 40 black members of the Georgia general

assembly, only one was elected from a majority white

district. T.Vol.IV,236; J.A. 26-7. Of the 31 black members

of the house, 26 were elected from districts that wrere 60%

or more black. Of the nine black members of the senate,

eight were elected from districts that were 60% or more

black. Abrams Exs. 23-4; T.Vol.VI,208; DO} Ex. 57;

T.Vol.VI,204. While only one black was elected from a

majority white district, whites won in 16 (29%) of the 55

majority black house and senate districts. J.A. 26-7.

With the exception of judicial elections in which

blacks were first appointed and ran as incumbents, no

black has ever been elected to a statewide office in Geor

gia. T.Vol.VI,77. No black, other than Andrew Young, has

ever been elected to Congress from Georgia from a major

ity white district. Stip. 241.

10

C. Discrimination in Prior Congressional Redis

tricting.4

Georgia's 1931 congressional reapportionment was

invalidated in Wesberry v. Sanders, 376 U.S. 1 (1964), on

one person, one vote grounds. The redistricting which

followed based on the 1970 census was the first congres

sional redistricting in the state subject to Section 5 review.

1. The 1971 Plan.

The plan initially passed by the state in 1971 discrim

inated in three distinct ways. First, it divided the concen

tration of black population in the metropolitan Atlanta

area into the Fourth, Fifth, and Sixth Districts to insure

that the Fifth would be majority white. Stips. 170, 173,

180; Basbee v. Smith, supra, 549 F.Supp. at 500. Second, it

moved the residences of blacks who were recognizable

potential candidates from the Fifth to the Sixth District,

i.e., Atlanta Vice-Mayor Maynard Jackson and Andrew

Young, who had run for the Fifth District in 1970. Stips.

172, 180; Busbee v. Smith, supra, 549 F.Supp. at 500. Third,

it included in the Fifth District the residences of whites

who were recognizable potential candidates. Stip. 172;

Busbee v. Smith, supra.

Blacks in the house and senate proposed alternative

plans during the 1971 redistricting process which

increased the minority percentage in the Fifth District.

4 The description of the 1971 and 1981 redistricting pro

cesses is taken, except where otherwise noted, from the findings

of the court in Busbee v. Sm ith, 549 F.Supp. 494, 500 (D.D.C.

1982), aff'd, 459 U.S. 1166 (1983), and the stipulations of the

parties.

11

Although these plans were supported by the black mem

bers, they were overwhelmingly rejected by the white

majority. Stips. 175-78.

The state submitted its plan for preclearance, but the

Attorney General objected. He was unable to conclude

"that these new boundaries will not have a discrimina

tory racial effect on voting by minimizing or diluting

black voting strength in the Atlanta area." Stip. 179. The

state drew another plan increasing the percentage of

blacks in the Fifth District to 44%, and the plan was

precleared. Stip. 181; Barone, Ujifusa, and Matthews, The

Almanac of American Politics 232 (1974).

2. The 1981 Plan.

The state's 1981 congressional plan was also the

product of intentional discrimination. Based on the 1980

census, the 1971 plan was malapportioned. Stip. 187. All

of the districts were majority white, with the exception of

the Fifth which was 50.3% black based upon total popula

tion. Busbee v. Smith, supra, 549 F.Supp. at 498.

The new plan drawn in 1982 maintained white major

ities in nine of the ten districts and increased the black

population in the Fifth to 57.3%. Stip. 188. While blacks

were a slight majority (52%) of the voting age population

("VAP") in the Fifth District, they were a minority (46%)

of registered voters. Stip. 189. The plan, as did the 1971

plan, split the concentrated black population in the met

ropolitan Atlanta area into three districts, the Fourth,

Fifth, and Sixth, to minimize minority voting strength.

Stips. 190-91, 195, 206, 234-35; Busbee v. Smith, supra, 549

F.Supp. at 515.

12

The state submitted the plan for Section 5 pre

clearance and the Attorney General objected. Stip. 183.

The state then filed a declaratory judgment action in the

district court for the District of Columbia, which also

denied preclearance. Stip. 186.

The senate, over the objections of some of its mem

bers, had passed a congressional plan containing a 69%

majority black Fifth District. Stip. 215. Those who objec

ted claimed the plan would divide congressional districts

into "black and white" and "bring out resegregation,"

Busbee v. Smith, supra, 549 F.Supp. at 507, and "might

allow the black community an opportunity to elect a

candidate of its choice to the United States Congress."

Stip. 213; Busbee v. Smith, supra, 549 F.Supp. at 506.

The house leadership rejected the senate's proposed

Fifth District. Stips. 216-18. Joe Mack Wilson, chair of the

house reapportionment committee and the person who

played the instrumental role in congressional redistrict

ing, explained to his colleagues that "I don't want to

draw nigger districts." Busbee v. Smith, supra, 549 F.Supp.

at 501; Stip. 199. He generally opposed legislation of

benefit to blacks, which he referred to as "nigger legisla

tion." Stip. 199; Busbee v. Smith, supra, 549 F.Supp. at 500.

Speaker Murphy was also opposed to the senate's

Fifth District because he felt "we were gerrymandering a

district to create a black district where a black would

certainly be elected." Busbee v. Smith, supra, 549 F.Supp. at

509-10. The speaker "refused to appoint black persons to

the conference committee [to resolve the dispute between

the house and senate] solely because they might support

a plan which would allow black voters, in one district, an

13

opportunity to elect a candidate of their choice." Stip.

220; Busbee v. Smith, supra, 549 F.Supp. at 510.

The District of Columbia court concluded - on the

basis of "overt racial statements, the conscious minimiz

ing of black voting strength, historical discrimination and

the absence of a legitimate non-racial reason for adoption

of the plan" - that the state's submission had a discrimi

natory purpose in violation of Section 5. Busbee v. Smith,

supra, 549 F.Supp. at 517. The state submitted a remedial

plan to the court which increased the black VAP in the

Fifth District to 60%, and the plan was precleared. Stip.

238; Barone and Ujifusa, The Almanac of American Politics

289 (1984).

D. 1991 Congressional Redistricting.

Based on the 1990 census African-Americans are 27%

of the total population and 24.6% of VAP in Georgia. J.A.

9. As a result of the census, the state's congressional

delegation increased from ten to 11 members. J.S.App. 5.

Prior to the beginning of the 1990s redistricting pro

cess, and prior to any involvement by the Department of

Justice, state officials agreed upon a goal of increasing the

number of majority black congressional districts from one

to two. T.Vol.II,37-8,69,123. The establishment of that goal

was due to a great extent to the increased number of

blacks serving in the general assembly and their advo

cacy of increasing the number of majority-minority con

gressional districts. T.Vol.II,124.

Members of the legislative black caucus, led by Rep

resentatives Brooks, McKinney, and John White, origi

nated and advocated the idea of creating not two but

14

three m ajo rity -m in o rity congressional d istricts.

T.Vol.IV,101,247-48. A similar position was advocated by

black senators on the floor of the senate. T.Vol.111,234-35.

They reasoned that because of racial bloc voting three

majority-minority districts were needed to provide blacks

with equal electoral opportunities roughly in keeping

with the black percentage of the state's population.

T.Vol.IV,228.

Ms. Wilde, at that time on the staff of the ACLU,

prepared a plan for the black caucus which contained

three majority-minority districts. J.A. 60-1; T.Vol.IV,101.

Her intent in preparing the plan was to comply with the

geographic compactness standard of Thornburg v. Gingles,

478 U.S. 30 (1986), and to demonstrate that a roughly

proportional number of majority black districts could be

drawn, not to maximize black voting strength in the sense

of creating the greatest possible number of majority-

minority districts. T.Vol.IV,71-2. In drawing her plan she

followed precinct lines, the state's traditional redistrict

ing building blocks. T.Vol.IV,83.

Ms. Wilde's plan was entered on the state's computer

and was officially named MCKINNEY.BMCCONGRESS

after Representative McKinney, the plan's principal spon

sor and a member of the house reapportionment commit

tee. The plan was also referred to as the Black Max or

Max plan. J.A. 60-1; J.S.App. 99 n.5; T.Vol.11,30-1. The

NAACP, the Georgia Association of Black Elected Offi

cials, Concerned Black Clergy, and the Southern Christian

Leadership Conference endorsed the McKinney-black

caucus plan. T.Vol.IV,86,230,233.

Lt. Governor Pierre Howard, who is white and is the

president of the senate, also supported the concept of

15

three majority black congressional districts. He advised

Senator Eugene Walker, the black chair of the senate

reapportionment committee, that "I was willing to try to

do the right thing about creating three districts."

T.Vol.IV,205. He denied that in taking such a position he

was acting under pressure from the Department of Jus

tice. Id. at 206. He did not, however, support the inclusion

of portions of Savannah in the Eleventh District. Id.

Redistricting began during the 1991 legislative ses

sion. Stip. 7. Both houses adopted redistricting guidelines

which included: complying with one person, one vote;

using single member districts only; drawing districts that

were contiguous; avoiding the dilution of minority voting

strength; maintaining the integrity of political subdivi

sions where possible; protecting incumbents; and, pre

serving the core of existing districts. J.S.App. 5; J.A. 65-77.

Compactness was not a redistricting criteria.

The guidelines were designed to "maximize public

input before and after the committee's redistricting plans

have been made." J.A. 65,72. The public was provided

access to all the committees' documents and records,

including all data bases used in redistricting. Proposed

redistricting plans could be presented to the committees

by any individual or organization. All proposed plans,

including those prepared by legislators, were required to

be race-conscious, i.e., to show "the minority population

for each proposed district." J.A. 68,74.

Public hearings were held throughout the state in

April, May, and August of 1991. At the first public hear

ing in April, the chairman of the Georgia Republican

Party submitted a plan creating a majority black district

extending from south DeKalb County to Augusta. J.A. 82;

16

T.Vol. 11,153. The plan was entered on the state's computer

as LINDA.TEMPLATE. LINDA.TEMPLATE became the

model for the Eleventh District. T.Vol.11,16,20,153-54.

A special session of the general assembly was held

from August 19 to September 5, 1991 for the purpose of

redistricting. A great many congressional plans were pro

posed and introduced during the public hearings, the

work sessions of the redistricting committees, and the

special session of the legislature. All the proposed plans

included between one and three majority black districts.

J.A. 13. Representative Brooks introduced the McKinney-

black caucus plan in the house in committee and offered

it as an amendment on the floor but the plan was never

adopted. T.Vol.IV,230; J.S.App. 99 n.5.

1. The First Plan.

The state submitted its first congressional redistrict

ing plan to the Department of Justice under Section 5 on

October 1, 1991. The plan contained two majority-minor

ity districts (the Fifth - 57.8% black VAP - and the Elev

enth - 56.6% black VAP), and a third district (the Second)

with 35.4% black VAP. J.S.App. 12 n.5; J.A. 14-5. The

Eleventh District in the first plan was modeled "almost

exactly" after LINDA.TEMPLATE. T.Vol.II,20,153-54; J.A.

82.

The Attorney General objected to the state's plan by

letter dated January 21, 1992, on the grounds that: "elec

tions in the State of Georgia are characterized by a pat

tern of racially polarized voting;" "the Georgia legislative

leadership was predisposed to limit black voting poten

tial to two black majority districts;" the leadership did

not make a good faith attempt to "recognize the black

17

voting potential of the large concentration of minorities

in southwest Georgia;" and, the state had provided only

pretextual reasons for failing to include in the Eleventh

District the minority population in Baldwin County. J.A.

99,105-07.

2. The Second Plan.

After the Section 5 objection, the reapportionment

committees and the general assembly considered

numerous other plans. J.A. 17. The senate passed a plan,

REDRAW.SREDRAW2, containing three majority black

districts and in which the black VAP in the Eleventh

District was increased from 56.6% to 58.7%. The Eleventh

District included concentrations of black population in

south Dekalb County, Augusta, and Savannah. J.A. 62,98.

The conference committee rejected the senate's plan.

T.Vol.III,212-13,234.

The state enacted a second plan and submitted it for

preclearance, again containing two majority black dis

tricts (the Fifth - 57.5% black VAP - and the Eleventh -

58% black VAP) and a third district (the Second) with 45%

black VAP. J.S.App. 17 n.9; J.A. 17-8,54. Once again, the

Eleventh District was modeled on LINDA.TEMPLATE,

and included minority population from Baldwin County.

T.Vol.II,153-54; J.A. 82.

The Attorney General objected to the second plan on

March 20, 1992 on the grounds that: the state remained

"predisposed to limit black voting potential to two black

majority voting age population districts;" "alternatives

including one adopted by the Senate included a large

number of black voters from Screven, Effingham and

Chatham Counties in the 11th Congressional District;"

18

and, the state had provided "no legitimate reason" for its

failure to include in a majority black congressional dis

trict the second largest concentration of blacks in the

state. J.A. 120,124-26.

The state made the decision not to seek judicial pre

clearance of its plans from the district court for the Dis

trict of Columbia. j.A. 21. Mark Cohen, the state's chief

legal advisor during redistricting, recommended against

seeking judicial preclearance because he felt the chances

of winning approval "were very much harmed by the

Busbee case, that we were in a similar situation because of

the Senate's action." T.Vol.V,6. Representative Bob

Hanner, chair of the house reapportionment committee,

opposed filing a lawsuit because he felt the state should

conduct its own redistricting and that the plan passed by

the senate (REDRAW.SREDRAW2) would cause the court

to reject the first and second plans. T.Vol.III,246,262.

Speaker Murphy expressed similar reasons for not seek

ing judicial preclearance. T.Vol.II,63,80,99.

3. The Third Plan.

The state submitted a third plan to the Attorney

General, which is the subject of this litigation, containing

three majority black districts (the Fifth - 57.5% black VAP,

the Eleventh - 60.4% black VAP, and the Second - 52.3%

black VAP) on April 1, 1992. J.A. 19-20,51-2. The plan

maintained the south DeKalb to Augusta core of the

Eleventh District similar to that in the first and second

plans. It also incorporated features of the senate plan

(REDRAW.SREDRAW2) in that it included portions of

Savannah in the Eleventh District. J.S.App. 93 n.l. The

plan was similar to the McKinney-black caucus plan in

19

that it contained three majority black districts, but as

Judge Edmondson found it was "significantly different in

shape in many ways." J.S.App. 99 n.5, 192. The submis

sion was precleared on April 2, 1992. J.S.App. 23.

The Eleventh District is not a regular geometric form,

but neither are any of the state's other congressional

districts. Prior plans had irregular districts, such as the

Eighth District under the 1980 plan. J.A. 80; T.Vol.II,84;

T.Vol.VI,70. Under the 1992 plan the Eighth District goes

from the suburbs of Atlanta all the way to the Florida

line. T.Vol.III,268. In addition, as Judge Edmondson

found, the Eleventh is far more regular looking in shape

than other congressional districts that have been chal

lenged in the wake of Shaw v. Reno, supra, such as the

Twelfth in North Carolina and the Z-shaped Fourth in

Louisiana. J.S.App. 99-100.

Plaintiffs' own expert testified that, based upon

quantitative measures, "the Eleventh District scored

above traditional cutoffs for compactness," J.S.App. 101

n.6, and that if a district is above the cutoff, "you proba

bly don't need to worry about these issues [of compact

ness]", T.Vol.IV,276-279, "you don't look." Id. at 286. He

also agreed that "geographical compactness" is "such a

hazy and ill-defined concept that it seems impossible to

apply it in any rigorous sense in matters of law."

T.Vol.IV,282.

Judge Edmondson found that social science measures

for compactness "show the Eleventh District is not

bizarre or highly irregular." J.S.App. 100. While not

endorsing the reliability of the measures, he concluded

that "[according to perimeter scoring, the Eleventh is

20

more compact than approximately forty-six other con

gressional districts in the country." Id.; T.Vol.111,179-80.

Under "dispersion measurements, the Eleventh is more

compact than about twenty-nine other districts." Id.

Creating a majority black Eleventh District and com

plying with the Attorney General's Section 5 objections

were admittedly significant factors in the state's adoption

of its final plan, but they were not the only significant

factors. While it did not discuss them in any detail, the

majority noted that the general assembly "was concerned

with passing redistricting legislation affecting all Geor

gians, and contended with numerous factors racial, politi

cal, economic, and personal." J.S.App. 26. The state's

"submissions reflected many influences." Id.

In compliance with the state's guidelines, the Elev

enth District substantially follows traditional political

boundaries. Seventy-one percent of the district's line fol

lows state, county, and municipal boundaries, a greater

percentage than in five other districts in the state.

J.S.App. 98; T.Vol.V,109. Again following the redistricting

guidelines, 87% of the area within the Eleventh District is

composed of intact counties, a greater percentage than in

seven other districts. J.S.App. 98. The majority (94%)

white Sixth District contains no intact counties. J.A. 20,27.

Partisan politics played an important role in the con

figuration of district lines. J.S.App. 95 n.2. In general,

Republicans favored a plan which would increase the

number of districts in which Republicans might control

the outcome of elections by increasing the number of

majority black districts. T.Vol.II,67-8.

21

Partisan political concerns and the purely personal

preferences of individual legislators dictated the con

struction of district lines in many ways. Speaker Murphy,

an ardent Democrat, advised the chairman of the house

reapportionment committee that he (Murphy) would not

support any plan that included Harrelson County, Mur

phy's county of residence, in the Sixth Congressional

District. The reason the speaker did not want Harrelson

County to be included in the Sixth District had nothing to

do with race but was based on the fact that the district

was represented by Republican Newt G ingrich.

T.Vol.II,73,75,77. According to Speaker Murphy, "Con

gressman Gingrich and I never got along. We didn't talk.

We didn't like each other and I just wanted out of his

district." T.Vol.II,77. As a result, "all the counties got split

in the Sixth." T.Vol.III,729.

Speaker Murphy intervened in congressional redis-

tricting on other occasions, none of which were related to

race. After the second objection by the Attorney General,

he helped move precinct lines in DeKalb County as a

personal favor to the lieutenant governor. The lieutenant

governor wanted to make sure the county of then Senator

Don Johnson was in the Tenth District, a district in which

Johnson could presumably win. On another occasion,

Speaker Murphy helped move precinct lines in Gwinnett

County at the request of a house colleague. T.Vol.II,78-9.

Other non-racial factors not discussed by the major

ity drove congressional redistricting and contributed to

the shape of the Eleventh District. The state made a

political decision to keep several rural majority white

counties in the Eleventh District intact, even though it

resulted in drawing more irregular lines elsewhere in the

district, i.e., making "them a little bit more crooked and

22

maybe not follow the major thoroughfare all the way

through," in urban areas such as Augusta and Savannah.

T.Vol.1,29-30,143-44.

The shape of the Eleventh District was drawn in an

irregular manner near the eastern border of DeKalb

County to accommodate the request of the chair of the

senate reapportionment committee that the majority

white precinct in which his son lived be included in the

district. T.Vol.11,187,202. Perhaps the most irregular part

of the Eleventh District is in western DeKalb County.

However, the irregularity is a function of the fact that the

line follows the boundary of the city of Atlanta.

T.Vol.11,197. At its narrowest point in DeKalb County, the

Eleventh District is constricted on one side by the tradi

tional boundaries of a major highway and on the other by

the city limits of Avondale Estates. T.Vol.II,199-200.

In Richmond County, the Eleventh District substan

tially follows precinct lines, municipal boundaries, and

major roadways. T.Vol.II,224. As Judge Edmondson

found, "the Eleventh makes curious turns in some

areas . . . [b]ut, in these areas most of the lines follow

existing city boundaries or major highways and roads."

J.S.App. 98.

Part of the Eleventh District was drawn into Butts

and Henry Counties, rather than in Newton and Rockdale

Counties, for purely political reasons to get the votes of

certain legislators. T.Vol.II,206-09. The portion of the

Eleventh District in Henry County is narrow because the

state made the non-racial decision to follow precinct

lines. T.Vol.1,207-09.

The district is narrow in Chatham County because a

local white representative, Sonny Dixon, wanted it drawn

23

"by the narrowest means possible," T.Vol.IV,174, to keep

as much of the county in the First District as possible,

especially all of Port Wentworth, Garden City, the Garden

City marine shipping terminal, and several industrial

plants north of Savannah. T.Vol.IV,172-78. Even then, as

Representative Dixon explained, the line "was not arbi

trarily selected" but follows "my State House District," as

well as the city of Savannah boundary. T.Vol.IV,177,178

("[w]e tried to use common lines between State House

Senate and congressional plans").

The Eleventh is narrow in Effingham County for

virtually the same reason, i.e., a local white representative

wanted to keep as much of the county out of the Eleventh

as possible. J.S.App. 44 n.25; T.Vol.1,107-09. "Politics"

influenced the decision about where to draw district lines

in Baldwin County as well. T.Vol.III,265.

According to Speaker Murphy, redistricting is "vastly

different" from other matters that come before the gen

eral assembly because "it's not just a one-issue thing.

There's hundreds of issues because there are hundreds of

people wanting their property and their county in a dif

ferent district." T.Vol.II,92-3.

E. The Decision of the District Court.

The majority found that "the plaintiffs suffered no

individual harm; the 1992 congressional redistricting

plans had no adverse consequences for these white

voters." J.S.App. 31. The record is also devoid of evidence

of harm to anyone else, or to any interest identified by

the Court in Shaw, i.e., increasing racial bloc voting or

depriving voters of effective representation. See 113 S.Ct.

24

at 2827-28. A parade of witnesses testified that the Elev

enth D istrict has not increased racial tension,

T.Vol.VI,45,120, caused segregation, T.Vol.IV,104,242,

T.Vol.VI,47,58, imposed a racial stigma, T.Vol.IV,104,240,

T .V ol.V I,38, deprived anyone of representation,

T.Vol.VI,36,56,117, caused harm, T.Vol.Ill,268, and is not a

guaranteed black seat. T.Vol.IV,106,239, T.Vol.VI,57,125.

The court acknowledged that "[ujnder the Supreme

Court's most recent pronouncements, this lack of con

crete, individual harm would deny them standing to

sue." J.S.App. 31. Nonetheless, in the majority's view

"Shaw v. Reno's expanded notion of harm liberalizes the

standing requirement." J.S.App. 33. In its order denying

the Abrams interveners' motion to dismiss for lack of

standing, the court ruled that it was not even necessary

for a plaintiff to reside in an irregularly shaped district to

have standing to challenge it. J.S.App. 104-09. The harm

suffered by plaintiffs was "systemic," and flowed simply

from the existence of a district which the majority

deemed was irregularly shaped. J.S.App. 32. For that

reason, a "regularly shaped" district, even though drawn

for reasons of race, could not confer standing. J.S.App. 32

and n.17 ("a compact majority-black voting district could

not be challenged as a racial 'gerrymander' "); J.S.App. 42

n.24 ("a bizarre district shape is indeed a 'threshold' for

purposes of standing").

While a bizarre shape was a requirement for stand

ing, the majority held that "[t]he shape of the district is

not a 'threshold' inquiry preceding an exploration of the

motives of the legislature." J.S.App. 30. Strict constitu

tional scrutiny was required where it is "shown that race

was the substantial or motivating consideration in creation

of the district in question." J.S.App. 36 (footnote omitted).

25

Thus, the majority held that the consideration of race in

redistricting was not sufficiently harmful to confer stand

ing, but it was sufficiently harmful to trigger strict scru

tiny.

Elsewhere in its opinion the majority held that any

consideration of race in redistricting was constitutionally

prohibited. Taking into account "the racial community of

interest shared by black citizens in Georgia . . . is barred

from constitutional recognition." J.S.App. 45. Despite its

extensive judicial notice of past discrimination and its

continuing effects in Georgia, J.S.App. 119, the court held

that "fa] voting district . . . that is configured to cater

to . . . 'black7 concerns is simply a race-based voting

district. It is based on superficial, racially founded gener

alizations," and "trafficks in racial stereotypes." J.S.App.

46. During the cross-examination of plaintiffs' expert,

however, who admitted that he had taken race into

account in drawing redistricting plans containing odd

shapes as a consultant in other voting cases, Judge Bowen

admonished the witness that "we've all done districting

on account of race. There is no reason to be embarrassed

about that." T.Vol.III,164.5

Race was a substantial factor in the construction of

the state's Ninth Congressional District. The Ninth,

which is approximately 95% white, J.A. 20, was created

5 Indeed, during a recess in the trial, Judge Bowen met with

attorneys in another voting case "to re-draw Laurens County."

T.Vol.V,141. He drew a court ordered plan intentionally creating

two m ajority black districts. Concerned Citizens Committee v. Lau

rens County, Georgia, Civ. No. CV392-033 (Sept. 8, 1994). A copy

of the order is reproduced in the appendix hereto at App. 1. One

of the m ajority black districts was divided by a river and was

"contiguous" only by virtue of an auto and foot bridge. App. 7.

26

during the 1980 redistricting process to preserve in one

district the distinctive white community in the mountain

area of the state. T.Vol.11,254-55; Busbee v. Smith, supra, 549

F.Supp. at 499, 517 (the state "placed cohesive white

communities throughout the state of Georgia into single

Congressional districts . . . [f]or example, the so-called

'mountain counties' of North Georgia"). The district was

again drawn as a majority white district during the 1990

redistricting process, and for the same reasons as in 1980.

Tr.Prelim.Injun. 126-28. Despite the fact that race was a

substantial or motivating factor in its construction, the

majority did not hold that the Ninth, like the Eleventh,

was constitutionally suspect or should be subjected to

strict scrutiny.

The majority held that the Eleventh District was

racially gerrymandered and stressed that it used narrow

"land bridges" to DeKalb, Richmond and Chatham Coun

ties to link centers of population. J.S.App. 43. Land

bridges, which are narrow corridors that may or may not

contain population, are not unique to the Eleventh Dis

trict, nor to the 1990 redistricting process. As Judge

Edmondson found, land bridges are used in the current

Seventh District, and were used in the 1970 congressional

redistricting plan. J.S.App. 98-9. The current Eighth Dis

trict also includes a land bridge. T.Vol.III,268. Moreover,

as the majority found, the land bridge to Chatham

County through Effingham was drawn in a narrow man

ner for non-racial reasons, i.e., "the representative from

that area succeeded in narrowing the bridge . . . by

keeping as much of the resident population within the

adjacent First Congressional District as possible."

J.S.App. 44 n.25.

In the majority's view, additional evidence of an

improper racial motive in the construction of the district

27

included simply the fact that the district was majority

black: "[ojther observations shed light on the racial

manipulations behind the Eleventh, most notably the

simple one that the total black population of Georgia is

26.96%, while within the Eleventh it is 64.07%." J.S.App.

48. The court did not find a similar racial motive in the

construction of congressional districts in which whites

exceeded their percentage of the state's population.

Although it acknowledged that "decisions of the

Attorney General are not reviewable by this Court,"

J.S.App. 63 n.32, the majority nonetheless directly

reviewed the Section 5 determination of the Attorney

General and held that it was "improper . . . because it

compelled legislative efforts not reasonably necessary/

narrowly tailored to the written dictates of the VRA."

J.S.App. 63. According to the majority, "DOJ stretched the

VRA farther than intended by Congress or allowed by the

Constitution." J.S.App. 65; 66 ("DOJ clearly disregarded"

applicable Voting Rights Act regulations); 26 (the Attor

ney General's "reading of the Voting Rights Act" was

"m isguided"). Because the Attorney General was

"wrong" in his interpretation of Section 5, the state had

"no compelling interest" in complying with the objection.

J.S.App. 62.6 The majority also held that "Georgia's cur

rent redistricting plan exceeds what is reasonably neces

sary to avoid retrogression under Section 5." J.S.App. 68.

The majority was highly critical of the role played by

black legislators in the redistricting process, whom it

6 The m ajority further held that a compelling state interest

in rem edying prior discrim ination in voting "does not exist

independent of the Voting Rights A ct." J.S.App. 56; 57 ("[a]ny

independent state interest in the remedial revision of voting

laws is subsum ed within that broad federal legislation").

28

castigated as "partisan 'informants' " and "secret agents,"

as well as the ACLU in providing information to the

Attorney General and proposing alternative redistricting

plans on behalf of minority and civil rights groups.

J.S.App. 24, 27. The chair of the house reapportionment

committee, however, denied that there was anything

improper about the ACLU assisting or being an effective

advocate for the black caucus. T.Vol.Ill,271-72. The regu

lations promulgated by the Attorney General for the

administration of Section 5, which have been held consti

tutional, Georgia v. United States, 411 U.S. 526, 536 (1973),

permit, and indeed encourage, comments from interested

third parties. 28 C.F.R. § 51.29.

Some black legislators and the ACLU urged the

Attorney General to object to the plan that was pre

cleared, T.Vol.IV,103, while as Judge Edmondson found,

the adopted plan "is significantly different in shape in

many ways" from the plan proposed by the ACLU.

J.S.App. 99 n.5; T.Vol.IV,107. Far from showing that the

ACLU or "partisan 'informants' " and "secret agents"

dominated the Attorney General and the preclearance/

redistricting process, the plan adopted by the state

showed, according to Judge Edmondson, "consideration

of other matters beyond race, including traditional dis

tricting factors (such as keeping political subdivisions

intact) and the usual political process of compromise and

trades for a variety of nonracial reasons." J.S.App. 99 n.5.

The majority also concluded that the Eleventh Dis

trict was not narrowly tailored because it contained a

larger concentration of minority voters than reasonably

necessary to give blacks a realistic opportunity to elect

candidates of their choice. J.S.App. 88-9. The court con

ceded that "some degree of vote polarization exists," but

that "[ejxact levels are unknowable." J.S.App. 83.

29

In his dissenting opinion, Judge Edmondson held

that Shaw v. Reno, supra, 113 S.Ct. at 2832, is narrow and

applies only to "a reapportionment scheme so irrational

on its face that it can be understood only as an effort to

segregate voters into separate voting districts because of

their race." J.S.App. 97. In concluding that the Eleventh

District was not bizarrely shaped, he found, inter alia,

that: "[t]he size of the district is not particularly notewor

thy;" "[t]he district's . . . miles of borders is not distinc

tive;" the district "shows considerable respect for existing

political boundaries;" "eighty-three percent of the Elev

enth's area comes from whole counties. In comparison,

the average among the State's other districts is sixty-two

and one-half percent;" "Georgia's congressional districts

have no tradition of being neat, geometric shapes;" areas

in other Georgia congressional districts "look - as irregu

lar or - much more irregular;" and, "[qualitative mea

surements for compactness . . . show the Eleventh District

is not bizarre or highly irregular." J.S.App. 97-100.

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

Shaw v. Reno is a narrow decision and subjects to

strict scrutiny only those districts which are bizarre in

shape, are race conscious, and segregate or harm voters.

The Court has recognized that in the redistricting process

race may be taken into account along with other factors.

The Eleventh District is not bizarre in shape com

pared with the district in Shaw or with other congres

sional districts. Race was not the sole factor in the

construction of the Eleventh District. Numerous factors

drove the redistricting process, such as following political

boundaries, protecting incumbents, and accommodating

a variety of economic, personal, and political interests.

30

No persons were harmed by the state's redistricting.

There was no evidence that anyone was unfairly stereo

typed, that patterns of racial bloc voting were exacer

bated , that anyone was deprived of e ffectiv e

representation, or that the voting strength of anyone was

diluted. The majority black districts are in fact the most

racially integrated districts in the state.

Although strict scrutiny is not applicable, the Elev

enth District would be constitutional if it were. In adopt

ing its plan the state had a compelling interest in

complying with the Voting Rights Act. The plan is not a

racial quota, makes no greater use of race than necessary,

is limited in duration, and does not harm third parties.

The lower court erred in judicially reviewing the

Attorney General's Section 5 objection and concluding

that it was improper. While a local court may judicially

decide coverage, only the District of Columbia court may

determine if a voting change violates Section 5.

The plaintiffs were not harmed by the state's redis

tricting. In the absence of individualized harm, plaintiffs

lack standing.

ARGUMENT

I. Georgia's Congressional Redistricting Is not Subject

to Strict Scrutiny

The court below held that strict constitutional scru

tiny was required where it is "shown that race was the

substantial or motivating consideration in creation of the

district in question." J.S.App. 36. It also held that any

consideration of race in redistricting was constitutionally

prohibited. Taking into account "the racial community of

interest shared by black citizens in Georgia . . . is barred

31

from constitutional recognition." J.S.App. 45. The deci

sion of the district court is contrary to Shaw v. R eno and

other decisions of this Court.

S haw held that "a reapportionment scheme so irra

tional on its face that it can be understood only as an

effort to segregate voters into separate voting districts

because of their race, and that the separation lacks suffi

cient justification," is subject to strict scrutiny under the

equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

113 S.Ct. at 2832. To establish a claim and invoke strict

scrutiny under S h aw , therefore, a plaintiff must establish

three elements: (1) the challenged plan must be "bizarre"

or "irrational" on its face, 113 S.Ct. at 2825, 2832, and not

merely "somewhat irregular," id. at 2826; (2) the plan

must be "unexplainable on grounds other than race," id.

at 2825; and, (3) the "only" possible explanation for the

plan must be a purpose to "segregate" the races for

purposes of voting. Id. at 2832. Stated succinctly, the

conjunction of bizarre shape, race consciousness, and

harm are the essential predicates for a claim under Shaw .

S haw repeatedly stated that it concerned only district

ing plans that were "bizarre," 113 S.Ct. at 2818, 2825-26,

2831, 2843, 2845, 2848, facially "irrational," id. at 2818,

2829, 2832, 2842, "highly irregular," id. at 2826, 2829,

"extremely irregular," id. at 2824, "dramatically irregu

lar," id. at 2820, or "tortured." Id. at 2827. By its terms the

decision applies only to the "rare" and "exceptional

cases." Id. at 2825-26.

Moreover, the Court did not indicate that bizarre

shape a lon e raised constitutional concerns or triggered

strict scrutiny. It expressly reaffirmed that "compactness"

was not "constitutionally required." 113 S.Ct, at 2827. See

G affn ey v. C u m m in g s, 412 U.S. 735, 752 n.18 (1973). A

32

contrary rule would radically transform federal-state

relations in reapportionment by subordinating all state

interests to an overriding federal requirement of com

pactness. Cf. V o in ov ich v. Q u ilter , 113 S.Ct. 1149, 1157

(1993) ("it is the domain of the states, and not the federal

courts, to conduct apportionment in the first place").

Elevating concerns about mere physical geography to

constitutional status would also undermine the Court's

oft-repeated admonition that "[legislators represent peo

ple, not trees or acres." R ey n o ld s v. S im s, 377 U.S. 533, 562

(1964).

Nor does S haw condemn the consideration of race in

redistricting p er se as the lower court erroneously held.

According to S haw , "race-conscious redistricting is not

always unconstitutional." 113 S.Ct. at 2824, 2826 ("race

consciousness does not lead inevitably to impermissible

race discrimination"). The Court expressed "no view as to

whether 'the intentional creation of majority-minority

districts, without more' always gives rise to an equal

protection claim." 113 S.Ct. at 2828.

S haw did not overrule U nited Jew ish O rgan ization s o f

W illiam sbu rg , Inc. v. C arey , 430 U.S. 144, 165 (1977), which

upheld without subjecting to strict scrutiny a state's legis

lative redistricting plan that "deliberately used race in a

purposeful manner" to create majority-minority districts.

The Court found no constitutional violation because there

was no dilution of the plaintiffs' voting strength. Id. at

165-66 (White, J. joined by Stevens, J. and Rehnquist, J.);

id. at 179-80 (Stewart, J., concurring, joined by Powell, J.).

S haw distinguished U JO on the grounds that the

plaintiffs in U JO "did not allege that the plan, on its face,

was so highly irregular that it rationally could be under

stood only as an effort to segregate voters by race." 113

33

S.Ct. at 2829. Thus, in its discussion of UJO, Shaw under

scores that the consideration of race in redistricting is

constitutionally suspect only in the context of bizarre

district shape and harm to voters.7

The decision of the district court that race "is barred

from constitutional recognition" in redistricting, J.S.App.

45, ignores both the reality and purpose of redistricting.

Shaw recognized that:

redistricting differs from other kinds of state

decisionmaking in that the legislature always is

aware of race when it draws district lines, just as

it is aware of age, economic status, religion and

political persuasion, and a variety of other

demographic factors.

113 S.Ct. at 2826.® This Court has consistently recognized

that "[district lines are rarely neutral phenomena," and

7 Com m entators have agreed that "Shaw is best read as an

exceptional doctrine for aberrational contexts rather than as a

prelude to a sw eeping constitutional condemnation of race

conscious redistricting." Pildes and Niemi, "Expressive Harms,

'B izarre D is tr ic t / and V oting R ights: E valu ating Election-

District Appearances after Shaw v. Reno," 92 Mich.L.Rev. 483,

495 (1993). According to Pildes and Niemi, the unique harm

com m unicated by a bizarre district is "the social impression that

race consciousness has overridden all other, traditionally rele

vant redistricting values." Id. at 526. Non-bizarrely shaped dis

tric ts , in clu d in g those w hich are race conscious, do not

com m unicate such concerns. Id. at 519. A leinkoff and Issa-

charoff reach a sim ilar conclusion in "Race and Redistricting:

D ra w in g C o n s t itu t io n a l L in es A fte r Shaw v. R en o," 92

Mich.L.Rev. 588, 613-14, 644 (1993).

8 The state's chief demographer, who has drawn hundreds

of redistricting plans at the congressional, state, and local levels

over the past two decades, candidly acknowledged that she had

"never drawn a redistricting plan . . . that didn't take race into

a c c o u n t ," and th a t " i f ta k in g race in to a cco u n t w ere

34

that "[t]he reality is that districting inevitably has and is

intended to have substantial political consequences." G af

fn e y v. C u m m in g s, su p ra , 412 U.S. at 752-53. Legislators

"necessarily make judgments about the probability that

the members of certain identifiable groups, whether

racial, ethnic, economic, or religious, will vote in the

same way." M o b ile v. B o ld en , 446 U.S. 55, 87 (1980)

(Stevens, J., concurring in the judgment). S ee U JO , su pra,

430 U.S. at 176 n.4 ("[i]t would be naive to suppose that

racial considerations do not enter into apportionment

decisions") (Brennan, J., concurring); B eer v. U n ited S tates,

425 U.S. 130, 144 (1976) ("lawmakers are quite aware that

the districts they create will have a white or a black

majority; and with each new district comes the unavoid

able choice as to the racial composition of the district")

(White, J., dissenting); D avis v. B an d em er, 478 U.S. 109, 147

(1986) (O'Connor, J., concurring in the judgment) (one of

the essential purposes of redistricting is to "reconcile the

competing claims of political, religious, ethnic, racial,

occupational and socioeconomic groups").9

unlawful . . . there is not a redistricting plan in the State of

Georgia that would be valid ." T.Vol.11,265.

9 Robert G. Dixon, Jr., a leading scholar of reapportion

ment, has w ritten: "[W jhether or not nonpopulation factors are

expressly taken into account in shaping political districts, they

are inevitably everpresent and operative. They influence all

election outcom es in all sets of districts. The key concept to

grasp is that there are no neutral lines for legislative districts . . .

every line drawn aligns partisans and interest blocs in a particu

lar way different from the alignm ent that would result from

putting the line in some other p lace." "Fair Criteria and Pro

cedure for Establishing Legislative D istricts" 7-8, in Representa

tion and R edistricting Issues (Grofm an, Lijphart, McKay, &

Scarrow eds. 1982).

35

Because race is inherent in redistricting, Shaw repeat

edly stressed that it must be the "only" factor driving the

process to trigger strict scrutiny. 113 S.Ct. at 2824. See,

e .g ., id. at 2824 (classification "solely on the basis of

race"); id. at 2825 (action "unexplainable on grounds

other than race"); id. at 2826 ("anything other than an

effort" to segregate voters); id. at 2827 ("created solely"

on the basis of race); id. at 2828 ("cannot be understood as

anything other than an effort to separate voters").

To be sure, a minority in a district may always chal

lenge a redistricting plan on statutory or constitutional

grounds if its voting strength has been diluted. In such a

challenge the plaintiffs would have the burden of proving

that the plan was purposefully discriminatory, R ogers v.

L odge, 458 U.S. 613 (1982), or had a discriminatory result.

T horn bu rg v. G in g les , su pra. But that is far different from

holding, as did the lower court, that in the absence of

proof of a discriminatory purpose or result a plan is

unconstitutional simply because race was a factor in

redistricting.

In T h orn bu rg v. G in g les, su p ra , 478 U.S. at 50, the

Court held that in proving a violation of Section 2, race

m ust be taken into account in proposing an alternative

redistricting plan to show that a minority could constitute

a majority in a single member district. It would be irra

tional, and would amount to repeal of Section 2, to hold

that a plan drawn to comply with G in gles was itself an

unconstitutional racial gerrymander because it took race

36

into account in showing that a minority was geograph

ically compact.10

A. The Eleventh District Is not Bizarre. District 11 is

not bizarre or irrational on its face. Although Shaw did