Dillard v. Crenshaw County, AL Brief for Plaintiffs-Appellees John Dillard

Public Court Documents

April 3, 1987

This item is featured in:

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Dillard v. Crenshaw County, AL Brief for Plaintiffs-Appellees John Dillard, 1987. beb800d7-af9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/7bde1e1d-6e8d-4d20-8590-05600bcb746f/dillard-v-crenshaw-county-al-brief-for-plaintiffs-appellees-john-dillard. Accessed January 31, 2026.

Copied!

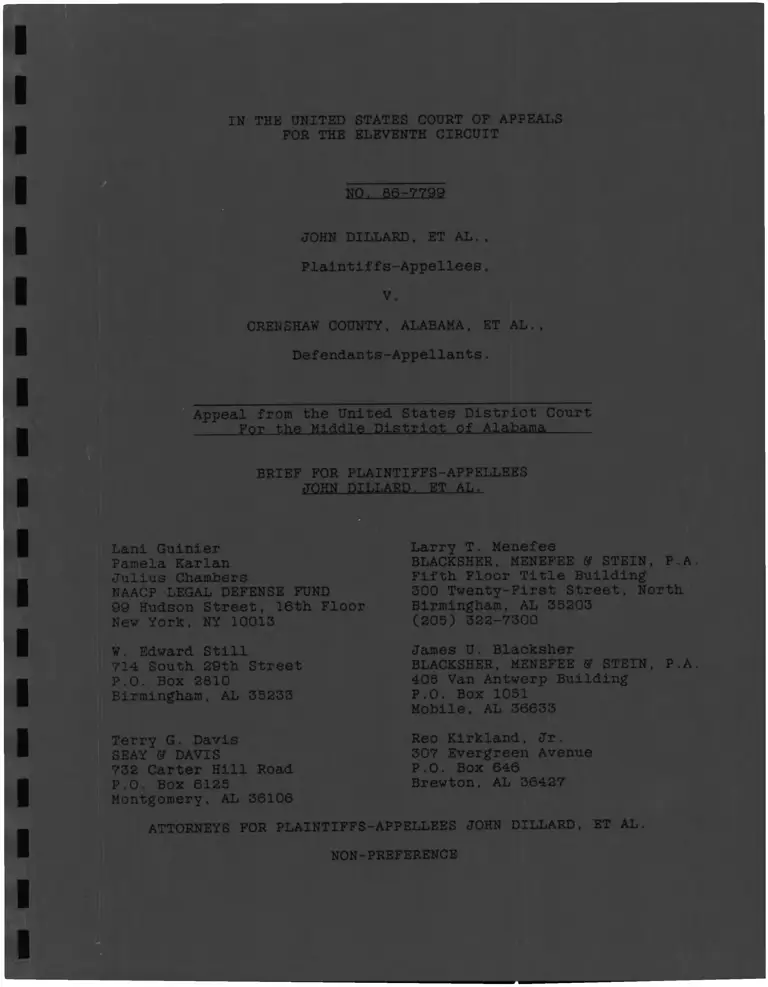

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALSFOR THE ELEVENTH CIRCUIT

NO. 86-7799

JOHN DILLARD, ET AL.,

Plaintiffs-Appellees,

V.

CRENSHAW COUNTY, ALABAMA, ET AL.,

Defendants-Appellants.

Appeal from the United States District Court

_____For the Middle District of Alabama_____

BRIEF FOR PLAINTIFFS-APPELLEES

JOHN DILLARD. ET AL■

Lani Guinier

Pamela KarlanJulius ChambersNAACP LEGAL DEFENSE FUND

99 Hudson Street, 16th Floor

New York, NY 10013

W. Edward Still 714 South 29th Street

P.O. Box 2810 Birmingham, AL 35233

Larry T. MenefeeBLACKSHER, MENEFEE & STEIN, P.A.

Fifth Floor Title Building 300 Twenty-First Street, North

Birmingham, AL 35203

(205) 322-7300

James U. Blacksher

BLACKSHER, MENEFEE & STEIN, P.A.

405 Van Antwerp Building

P.O. Box 1051

Mobile, AL 36633

Terry G. Davis

SEAY & DAVIS 732 Carter Hill Road

P.O. Box 6125 Montgomery, AL 36106

Reo Kirkland, Jr.

307 Evergreen Avenue

P.O. Box 646 Brewton, AL 36427

ATTORNEYS FOR PLAINTIFFS-APPELLEES JOHN DILLARD. ET AL.

NON-PREFERENCE

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE ELEVENTH CIRCUIT

NO, 86-7799

JOHN DILLARD, ET AL.,

Plaintiffs-Appellees,

V.

CRENSHAW COUNTY, ALABAMA, ET AL.,

Defendants-Appellants.

Appeal from the United States District Court

-----Eor the Middle District of Alabama_____

BRIEF FOR PLAINTIFFS-APPELLEES JOHN DILLARD. ET AL.

Lani Guinier

Pamela Karlan

Julius Chambers

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE FUND

99 Hudson Street, 16th Floor

New York, NY 10013

W. Edward Still

714 South 29th Street

P.O. Box 2810

Birmingham, AL 35233

Larry T. Menefee BLACKSHER, MENEFEE & STEIN, P.A

Fifth Floor Title Building

300 Twenty-First Street, North

Birmingham, AL 35203

(205) 322-7300

James U. Blacksher

BLACKSHER, MENEFEE & STEIN, P.A405 Van Antwerp Building

P.O. Box 1051

Mobile, AL 36633

Reo Kirkland, Jr.

307 Evergreen Avenue

P.O. Box 646

Brewton, AL 36427

Terry G. Davis

SEAY & DAVIS

732 Carter Hill Road

P.O. Box 6125

Montgomery, AL 36106

ATTORNEYS FOR PLAINTIFFS-APPELLEES JOHN DILLARD, ET AL.

NON-PREFERENCE

CERTIFICATE OF INTERESTED PARTIES

Pursuant to Rule 22(f)(3), the undersigned counsel of

record for appellees certifies that the following listed parties

have an interest in the outcome of this case. These

representations are made in order that the Judges of this Court

may evaluate possible disqualification or recusal pursuant to

Rule 22(f)(3).

Defendants: Calhoun County, Alabama; Arthur Murray,

Probate Judge; Roy Snead, Sheriff; Forrest Dobbins, Circuit

Clerk; Gerald Wilkerson and Clarence Page, past members of the

County Commission; Charles Fuller, James Dunn, Mike Rogers,

Donald Curry, Ralph Johnson, members of the County Commission of

Calhoun County; Leon Bradley, Chairman-Elect of the County

Commission.

Herbert D. Jones, Jr. and H. R. Burnham, Attorneys for

Calhoun County, Alabama, et al., members of the firm of Burnham,

Klinefelter, Halsey, Jones S’ Cater, P.C., of Anniston, Alabama.

Plaintiffs: Earwen Ferrell, Ralph Bradford and Clarence

J. Jairrels, individually and as representatives of a plaintiff

class of all black citizens of Calhoun County, Alabama.

Counsel for the Plaintiffs-Appellees: Larry T. Menefee,

James U. Blacksher of Blacksher, Menefee S’ Stein, P.A.; Edward

Still, Birmingham, Alabama; Terry Davis, Seay S’ Davis,

Montgomery, Alabama; Reo Kirkland, Brewton, Alabama; Julius

Lavonne Chambers, Lani Guinier and Pamela Karlan of the NAACP

Legal Defense and Educational Fund, New York City.

Trial Judge in this case was the Honorable Myron C.

Thompson of the United States District Court for the Middle

District of Alabama.

BLACKSHER, MENEFEE 5? STEIN, P.A.

Fifth Floor Title Building

300 Twenty-First Street North Birmingham, AL 35203

ATTORNEYS FOR PLAINTIFFS-APPELLEES JOHN DILLARD, ET AL.

ii

STATEMENT REGARDING PREFERENCE

This case is not entitled to a preference.

STATEMENT REGARDING ORAL ARGUMENT

Solely because of the somewhat complicated procedural

history of this case, Plaintiffs-Appellees believe oral argument

would be of assistance to the court.

iii

TABLE OF CONTENTS

CERTIFICATE OF INTERESTED PERSONS ....................... i-ii

STATEMENT REGARDING PREFERENCE .......................... iii

STATEMENT REGARDING ORAL ARGUMENT ....................... H i

TABLE OF CONTENTS........................................ iv-v

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES..................................... vi-viii

STATEMENT OF THE ISSUES ................................. 1

STATEMENT OF THE CASE.................................... 2-12

A. Course of Proceedings and Dispositions inthe Court Below................................. 2-3

B. Statement of the Facts.......................... 3-11

C. Statement of the Standard or Scope of Review..... 11-12

SUMMARY OF THE ARGUMENT.................................. 12-15

STATEMENT OF JURISDICTION................................ 15

ARGUMENT................................................. 15-35

I. the DISTRICT COURT PROPERLY REJECTED THE AT-LARGE

CHAIR POSITION PROPOSED BY CALHOUN COUNTY ...... 15-29

A. The Proper Standard of Review............. 17-19

B. The District Court Followed the Correct

Procedure for Developing a Court-Ordered Redistricting Plan......................... 19-20

C. The Proposed At-Large Chair Position Was

Actually Inconsistent with State Policy, and the District Court Did Not Abuse Its

Equitable Powers By Rejecting It........... 21-25

PAGE t S]

iv

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PAGE(S)

D. The District Court Correctly Held That the

County's Proposal Failed to Remedy Fully the

Violation of Section 2.................... 25-28

E. The District Court Correctly Found From the

Totality of Evidence That Calhoun County's

Proposed At-large Chair Would Itself Violate

Section 2's Results Test.................. 28-29

II. THIS COURT SHOULD REJECT THE E£R NUMERICAL RULE

PROPOSED BY THE DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE.......... 29-35

CONCLUSION............................................... 35-36

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE.................................... 37

v

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

CASES:

Chapman v, Meier,420 U.S. 1 (1976)..................................... 20

Clark v. Marengo County. Nos. 85-7634 and 86-7703

(11th Cir., Jan. 27, 1987) (unpublished).......... 24-25

Connor v. Finch.

431 U.S. 407 (1977).............................. 20, 21

Dillard v. Crenshaw County.640 F.Supp. 1347 (M.D. Ala. 1986)................ 4

Dillard v, Crenshaw County.649 F.Supp. 289 (M.D. Ala. 1986)................. passim

Edge y. .Sumter County School District,775 F. 2d 1509 (11th Cir. 1985)................... 20, 28

Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co..

424 U.S. 794 (1976)............................. 17

Fullllove y , Klutsnlck,448 U.S. 448 (1980).............................. 17

Gomllllon v, Llghtfoot,364 U.S. 359 (1960).............................. 30

Green v. County School Bd. of New Kent County.391 U.S. 430 (1968).............................. 16

Louisiana v. United States.380 U.S. 145 (1965).............................. 15

McDaniel v. Sanchez.452 U.S. 130 (1981).............................. 19

Paige v. Gray-538 F. 2d 1108 (5th Cir. 1976).................... 20

PAGE(S)

vi

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

CASES:

Rogers v. Lodge.

458 U.S. 613 (1982)............................. 18, 31

Roman v. Slncock.

377 U.S. 695 (1964)............................. 20

Swann v,_Charlotte-Meoklenburg Bd. of Education.402 U.S. 1 (1971)............................... 17-18

Thornburg v. Gingles.

478 U.S. ___, 92 L .Ed.2d 25, 106 S.Ct. 2752

dose)........................................... ii, i6,

18, 30-34

United States v. Paradise.

107 S.Ct. 1053 (1987)............................ 17-18

Unham v. Seamon.

456 U.S. 37 (1982).............................. 12

White v, Regester,

412 U.S. 755 (1973)............................. 18, 31

Knight v. City of Houston.

806 F. 2d 635 (5th Cir. 1986)..................... 28

STATUTES AND RULES:

28 U.S.C. sec. 1291.................................... 15

Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965,

as amended, 42 U.S.C. section 1973............... passim

Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965,

42 U.S.C. section 1973o.......................... 19

Ala. Code sec. 11-3-11 (1975)......................... 22

Ala. Code sec. 11-3-20 (Supp. 1986)................... 13

No. 420, 1939 Local Acts of Alabama, Reg. Sess........ 3-4

PAGE(S)

vii

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

STATUTES AND RULES:

Rule 52, F.R.C.P...................................... 11

Rule 65, F.R.C.P...................................... 4

OTHER AUTHORITIES:

H.R.Rep.No. 97-227 (1982)............................. 26-27

S.Rep. NO.97-417 (1982)............................... 16, 18, 20,

26, 28-33Carney, J. , Nation Cl Change: The AmericanDemocratic System (1972).............................. 22

Cummings, Jr., M., and Wise, D., Democracy Under Pressure (1977)....................................... 22

Dye, T., Greene, L., Parthemos, G., Governing

the American Democracy (1980)......................... 22

Watson, R., and Fitzgerald, M., Promise and

Eerformance el American Government (3d ed. 1978)...... 22

U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, The Voting Rights

Act: Ten Years After (1975)............................ 26

NOTE TO CITATIONS

Brief of the Appellants Calhoun County, et al. App.Br. p. ___

Brief of United States As Amicus Curiae U.S. Br. p. ___

Brief of United States in United States v. U.S. Marengo

Marengo County Commission , No. 86-7703, Br. p. ___Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit

PAGE(S)

viii

STATEMENT OF THE ISSUES

1. Whether the district court abused its equitable

discretion by rejecting for inclusion in its court-ordered plan

to remedy an existing Section 2 violation Calhoun County's

proposal for an at-large elected chairperson.

2. Whether the district court made clearly erroneous

findings of fact when it determined, based on the totality of

circumstances in Calhoun County, that the proposed at-large chair

position would result in dilution of black voting strength, in

violation of Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act?

1

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

A. Course of Proceedings and Dispositions In the Court Below

Appellees adopt the statement of the Course of

Proceedings Below as contained in Appellant's Brief, pp. 2-5.

Appellees, however, add the following portion of the

Stipulation entered into by the parties:

STIPULATION

The parties Plaintiff and Defendant in Calhoun, Etowah,

Talladega and Lawrence Counties stipulate as follows:

1. The Defendants stipulate that the present

over-all form of county government, which includes

election of associate commissioners and a commission chairman at-large, currently results in dilution of

black voting strength in violation of Section 2 of the

Voting Rights Act of 1965, as amended, 42 U.S.C.

section 1973. Defendants further stipulate that a

different form of government must be instituted to

redress this violation. Defendants do not admit or

stipulate, however, that the at-large election of a

county commission chairman, in and of itself,

necessarily is violative of Section 2 or any other

law.

2. The Defendants reserve the right to demonstrate

that the present Section 2 violation can adequately be

remedied and black citizens afforded full and equal

access to the political process by remedial election plans that may contain a chair, administrator or county

executive elected at-large by voters of the entire

county.

Any such remedial plan presented by the Defendants

shall be considered and evaluated by the Court without

any presumption against the inclusion of a chairman

2

elected at-large simply because the present systems, stipulated herein to be violative of the Voting Rights

Act, contain a chairman elected at-large. In other

words, the fact that the present form of government has

as one component a chairman elected at-large shall not,

in and of ifself, constitute a basis for rejecting or

accepting a proposed remedial plan which includes a chairman elected at-large.

Nothing in this paragraph or stipulation shall be

construed to change the allocation of the burden of

proof at the remedy stage of this litigation under

applicable law or procedure, and nothing in this

paragraph or stipulation shall be understood to allow

or require the Court, at the remedy stage, to deviate

from applicable law or procedure regarding deference,

if any, which must be given a remedial plan submitted by the Defendants.

3. It is understood that the Plaintiffs reserve

the right, and intend, to present evidence of the

dilutive effect of at-large voting with respect to all

positions, including associate commissioner positions

as well as the chairman position, when challenging any

remedial plan submitted by the Defendants which

includes as a component a chairman elected by the voters of the county at-large.

R. 6-201-1-2.

B. Statement of the Facts

Calhoun County has, since 1939, been governed by a

three-member county commission elected at large. Local Act No.

420 of the 1939 Regular Session of the Alabama Legislature

divided Calhoun County into two residency districts, provided for

the election of all three commissioners at large, and provided

that the commission member without any residency requirement

should be denominated the "chairman". The salary of the chairman

was twice that of the other two commissioners. There was no

3

further distinction whatsoever made between the duties and

responsibilities of the three members of the commission. The Act

provided that:

There is hereby conferred upon said County Commission

all the jurisdiction and powers which are how [sic] or

may hereafter be vested by law in courts of County

Commissioners, Boards of Revenue, or other like

governing bodies of the several counties of this state.

1No. 420, section 2, 1939 Local Acts of Alabama, Regular Session.

2In its opinion on plaintiffs' Motion for Preliminary Injunction,

the district court found that the State of Alabama had maintained

a policy of systematically discriminating against black citizens

and their right to vote by the utilization of at-large elections

with numbered posts. 640 F. Supp. at 1360-61. The court also

found that the results of this invidious discrimination are

manifest today in the racially polarized voting and lack of

success of candidates supported by the black communities. Id.

Pursuant to the provisions of Rule 65 Fed.R.Civ.P.. the district

court in its opinion of October 21 relied upon evidence submitted

3

at the hearing on preliminary injunction. It found that

1

A copy of the Act is attached as an appendix to this

brief.

2 Dillardsy ,_Crenshaw County. 640 F.Supp. 1347 (m .d . Ala.1986) (Dillard I).

3

Dillard v.__Crenshaw County. 649 F. Supp. 289, 294 (M.D.

Ala. 1986) (Dillard II).

4

historic discrimination in all areas of the economic and social

life of

Alabama blacks, including ... education, employment and health services . . . has resulted in a lower

socio-economic status for Alabama blacks as a group than for whites, and this lower status has not only

given rise to special group interests for blacks, it

has depressed the level of black participation and

thereby hindered the ability of blacks to participate

effectively in the political process and to elect

representatives of their choice to the associate and

chairperson positions on county commissions in Calhoun,

Lawrence, and Pickens Counties.

649 F. Supp. at 295.

The parties stipulated that the

present over-all form of county government, which

includes election of associate commissioners and the commission chairman at large, currently results in

dilution of black voting strength in violation of Section 2.

R. 6-201-1, ei seq. Calhoun County reserved the right to

demonstrate that the retention of one at-large seat would not

have a discriminatory purpose or effect and would remedy the

existing Section 2 violation. Id.

At the hearing on remedy issues, plaintiffs presented a

survey of Alabama county governments. Though many Alabama county

commissions have been chaired by the probate judge, Calhoun

County has not been part of that tradition. Only four counties

use the mixed system proposed by Calhoun County of commissioners

elected from single-member districts and the chairman elected at

5

4

large. R. 10-22. However, sixteen counties have commissioners

elected from single-member districts and choose their chair from

5

among the county commissioners. R. 10-23.

The plaintiffs also presented testimony from Dr. Gordon

Henderson, a political scientist with extensive experience

analyzing racial voting patterns. Dr. Henderson testified that

Calhoun County elections showed a clear pattern of racially

polarized voting, with very few whites willing to vote for black

6

candidates. R. 10-208-09. Dr. Henderson also presented

overwhelming and uncontradicted evidence of the disadvantaged

7

socio-economic status of blacks in Calhoun County. There was no

contradictory evidence offered by the defendants. Dr. Henderson

concluded on the basis of his study that an at-large election for

the position of chair of the Calhoun County commission results in

the dilution of black voting strength. Dr. Henderson went on to

4

However, none of defendants' witnesses, not even former

state senator Donald Stewart, was aware there were other counties

in the state that had the form of government requested by Calhoun

County. R. 11-289.

5

Three other counties are scheduled to change to this form

in the near future. R. 10-23

6 Dr. Henderson utilized a statistical technique known as

bivariate regression analysis and a technique known as "extreme

case" or homogeneous case analysis. Thornburg v. Gingles. 478

U.S. ___, 106 S.Ct. 2752, 2768 (1986).

7 Plaintiffs' Ex. 2, an extensive affidavit by Dr. Henderson,

was admitted into evidence. His testimony is found at R.

10-170-76 and is summarized by the appellant's brief at pp.

8- 1 0 .

6

explain that it was unlikely that the candidate favored by the

black community would have a chance of winning, and, as a

consequence, black voting strength would be diluted,

representational strength would be lessened and there would be a

negative influence on the political socialization of the black

community. R. 10-213-15. No contradictory testimony was offered

in rebuttal.

Plaintiffs and defendant Calhoun County both offered

several lay witnesses who expressed their personal opinions about

at-large elections, opportunities for black citizens to

participate in the political life of Calhoun County, and the

desirability or not of having a chair elected at large. The

testimony was conflicting on this latter point; the witnesses

called by the plaintiffs opposed the at-large elected chair, and

the witnesses called by the defendants favored the at-large

elected chair. Nevertheless, even the witnesses called by the

defendants agreed generally that voting in Calhoun County was

8

racially polarized, that a black citizen would have less

opportunity than a white citizen to be elected to an at-large

8

Donald Stewart, R. 11-290; Willie Snow, R. 11-303; Hansler

Bealyer, R. 11-329; William Trammell, R. 31-338; Theodore Fox, R.

11-349; N. Q. Reynolds, R. 11-356; Chester Weeks, R. 11-368.

7

position, and that a district election plan was necessary to

10

provide blacks representation. Some of the defense witnesses

favored the at-large elected chair because of their favorable

experience dealing with a council-manager form of city government

in Anniston. Other defense witnesses indicated that their

preference for an at-large chair was tied to their favorable

comparison of the incumbent chairman of the county commission

12with his predecessors, who were not viewed favorably.

The only description of the duties of the chairman of

the county commission came through the testimony of the present

county administrator and treasurer, Hr. Ken Joiner. He said the

incumbent chairman presided at the commission meetings, responded

to citizens' complaints, represented the county at the

governmental committee meetings, met with industrial prospects,

met with the state legislators, and acted as liaison with local

military installations. R. 11-370-372. However, Mr. Joiner also

described his own duties as following legislative trends,

9

9

Willie Snow, R. 11-303; Hensler Bealyer, R. 11-330, n. 11; William Trammell, R. 11-339; Theodore Fox, R. 11-349; R. Q. Reynolds, 11-356.

10

Willie Snow, R. 11-302; Hansler Bealyer, R. 11-332;William Trammell, R. 11-340; N. Q. Reynolds, R. 11-356.

11

Donald Stewart, R. 11-291; Hansler Bealyer, R. 11-325.

12

Donald Stewart, R. 11-295; Willie Snow, R. 11-301, 305-06,

James Dunn, R. 11-316, 319-320; Hansler Bealyer, R. 11-327, N. Q . Reynolds, R. 11-3551.

8

ensuring compliance with employment laws, dealing with the public

on a daily basis and "administering the things that I have just

gone over that the chairman currently does". R. 11-372. He did

not identify any duties that are "unique" to the chairman's

office.

The district court found that the majority vote

requirement is an "insurmountable" barrier to the ability of

black voters to elect candidates as chair of the commission. The

court found that the black community of Calhoun County was

"politicaly cohesive and geographically insular" and that

racially polarized voting is severe and persistent" and would

result "in the defeat of any black candidates who ran for" the

chairperson position. 649 F. Supp. at 295. The court found that

candidates had encouraged voting along racial lines by appealing

to racial prejudice which "effectively wiped out any realistic

opportunity for blacks to elect a candidate of their choice."

IsL. Taking into account the totality of circumstances, the

district court found that the requirement of at-large elections

for associate commissioners and chairpersons, "together and

separately, violate section 2. Each of these requirements, in

conjunction with the social, political, economic, and geographic

conditions described above, has effectively denied the black

citizens of each county an equal opportunity to participate in

the political process and to elect candidates of their choice.

9

... [Tlhis court would have to shut its eyes to reality, past and

present, to find otherwise." Id. The court found that any

effective cure for the Section 2 violation by the existing plans

would have to include the chairperson position and that the

submitted plan violated Section 2 under the results test. 649 F.

Supp. at 295-96.

The district court rejected the argument that the chair

position ought to be elected at large because it is a

"single-position" office with "unique" duties, like a probate

judge, sheriff or district attorney. 649 F.Supp. at 296. It

found as a matter of fact that the proposed remedy with an

at-large elected chair possessing additional administrative

duties

fundamentally alters the form of government for the county in a way that is unprecedented elsewhere in

Alabama. It would also dilute black voting strength by

depriving the other commissioners of the practical

political powers the commissioners normally enjoy.Just at the time that the Voting Rights Act affords

blacks an equal opportunity to elect candidates of

their choice to the county commission, persons they are

able to elect would end up with less practical

political influence than that of their previously

at-large elected counterparts. Important day-to-day

political power would be transferred to a single

person, who would be elected by the very at-large

majority system that this court has declared unlawful

because it impermissibly dilutes black voting strength.

649 F. Supp. at 296. The court rejected the analogy to a

mayor-council form of city government, where the executive and

legislative functions are almost entirely separated. Instead the

10

court reasoned that the county commission form of government was

most like a city commission or school board where "the

commissioners exercise both executive and legislative powers."

M. The court found it was "significant that there is no

compelling state policy" for the chairperson-administrative

position sought by Calhoun County, and that Calhoun County had

failed to advance reasons why a system utilized by most other

Alabama counties would not be satisfactory, "particularly at a

time when it appears that elections will finally have become

racially fair." 649 F.Supp. at 296-97. The court found that the

chairperson position with enhanced administrative

responsibilities would be an office "completely beyond the reach

of the counties' black citizens and thus reserved exclusively for

the white citizens" and refused to approve such a proposed

remedy. 649 F. Supp. at 297.

C. Statement of the Standard or Scope of Review

The findings of the district court that the at-large

elected chair position would hinder "the ability of black

citizens to participate effectively in the political process and

to elect representatives of their choice . . .", (op. p. 91),

must be reviewed under the clearly erroneous standard of Rule 52,

Fed.R .Civ.P.: Thornburg v.__Glngles, 106 S. Ct. 2752, 2781

11

(1986).

13

The district court was to determine a remedy and had

available traditional equitable powers. The exercise of that

power is reviewed under an abuse of discretion standard. Upham

__Seamon. 456 U.S. 37 (1982).

SUMMARY OF THE ARGUMENT

The district court's task was to fashion an appropriate

remedy for racial vote dilution caused by the at-large scheme for

electing all members of the Calhoun County Commission, which the

parties stipulated violated Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act.

The Alabama Legislature failed to adopt a remedial

election plan for Calhoun County, which was operating under a

1939 local act. Accordingly, the district court invited the

incumbent Calhoun County commissioners to propose a plan that

would be incorporated in a court-ordered remedy. The incumbents

proposed and the plaintiffs agreed to the use of five

single-member district commissioners, one of which would be

elected from a black majority district. The only disagreement

between the parties, and the only issue presented in this appeal,

is whether the district court properly refused to adopt a sixth

seat, an at-large elected chair of the commission, as

13

Contrast U.S.Br. p.5 urging legal error standard of review

Wltil U.S. Marengo Br. p.12 urging clearly erroneous standard of review.

12

Under existing state law, all members of the county

commission share legislative, executive and certain judicial

functions. The only specified duty of the chairperson is to

preside at commission meetings. Ala. Code section 11-3-20 (Supp.

1986). Calhoun County's written remedial proposal does not

specify any further duties or powers for the at-large chair.

However, in arguments to the district court and in this Court, it

contends that the at-large chair should exercise extensive

executive powers that would not be shared with the single-member

district commissioners. These unspecified executive powers are

apparently modeled after those exercised by the incumbent

chairman through informal arrangements with the other incumbent

commissioners. The new chairperson, as presented by Calhoun

County's brief, would become a powerful chief executive for the

county. The district court properly refused to accept Calhoun

County's invitation to disturb in such a radical fashion the

existing form of county government, particularly when it would

operate to diminish the electoral influence of black citizens.

Because the at-large chair position proposed by the

defendant incumbents is actually at odds with the state law

governing the form of government for Calhoun County, the district

court did not abuse its discretion in ruling that there was no

compelling state policy justifying departure from the general

additionally proposed by the incumbent commissioners.

13

equitable principle preferring only single-member districts in

court-ordered remedies.

Neither did the district court abuse its discretion by

rejecting the at-large chair proposal on the ground that it would

diminish the political strength of the person elected from the

black majority district and would deny black citizens an equal

opportunity to participate in the political processes influencing

the executive functions proposed for the new chair position. The

district court properly concluded that such a plan would fail to

satisfy the sweeping remedial objectives of Section 2 of the

Voting Rights Act.

Finally, the district court conducted an independent

factual assessment of the proposed at-large chair position

utilizing the evidentiary factors provided by Congress for

determining whether an electoral structure fails the results test

of Section 2. These findings were based on virtually

uncontradicted evidence and are not clearly erroneous.

The U. S. Department of Justice has filed an amicus

brief which fails entirely to discuss the local circumstances of

politics in Calhoun County and, instead, urges this Court to

erect a mechanical per se rule. This rule would absolutely

require district courts to accept in their court-ordered remedial

plans proposals by local jurisdictions which offer blacks

something close to numerical proportional representation, without

14

regard, to the relative political influence of the black and white

representatives and. without regard, to the ability of black

citizens equally to influence all levels of local government.

The Department's radical new rule would literally read the Equal

Participation Clause out of Section 2. And it would directly

contravene the directives of Congress and the Supreme Court that

federal courts always conduct a sensitive appraisal of political

realities and the totality of circumstances in each jurisdiction

to determine whether black citizens were being afforded equal

access to the political process. This Court should reject the

Department's regressive adventurism in the strongest possible

terms.

STATEMENT OF JURISDICTION

This court has jurisdiction of this appeal under 28

U.S.C. section 1291.

ARGUMENT

I. THE DISTRICT COURT PROPERLY REJECTED THE AT-LARGE

CHAIR POSITION PROPOSED BY CALHOUN COUNTY

A district court faced with a violation of the Voting

Rights Act "has not merely the power but [also] the duty to

render a decree which will so far as possible eliminate the

discriminatory effects of the past as well as bar like

discrimination in the future." Louisiana v. United States. 380

15

U.S. 145, 154 (1965). The Act was Intended "to create a set of

mechanisms for dealing with continued voting discrimination, not

step by step, but comprehensively and finally." S.Rep.No.

14

97-417, p .5 (1982). Thus, when a jurisdiction that is found to

have violated the Act submits a proposed remedy, it bears the

burden of"com[ing] forward with a plan that promises

realistically to work, and promises realistically to work now.11

Green v,__School Board of New Kent County. 391 U.S. 430, 439

(1968); £££ S.Rep.No. 97-417, p.31, n.121 (1982) (relying on

Green to illustrate the scope of the remedial obligation in

Section 2 cases). And in imposing a remedy, the district court

"should exercise its traditional equitable powers so that it

completely remedies the prior dilution of minority voting

strength and fully provides equal opportunity for minority

citizens to participate and to elect candidates of their

choice." Id. at 31. In this case, the district court properly

rejected Calhoun County's proposal for one full-time

commissioner, with enhanced executive powers, elected at large in

addition to five commissioners elected from single-member

districts. Moreover, the district court properly ordered the

14

The Supreme Court has characterized the Senate Report as

an "authoritative source" for determining Congress' purpose in

enacting the 1982 amendments to the Act, which firmly established

the results test of section 2. Thornburg Gingles. 478 U.S.__, 92 L .Ed.2d 25, 42 n.7, 106 S.Ct. 2752, 2763 n.7.

16

A • The Proper Standard, of Review

Recently, in United States v. Paradise. 107 S.Ct. 1053

(1987), the Supreme Court discussed the standard to be used in

reviewing a district court's use of its equitable powers to

remedy entrenched, intentional discrimination. The Court's

observations are particularly salient to this case because they

came in the course of affirming a remedial order entered by the

same district court whose actions are being challenged here.

Justice Brennan's plurality opinion stated:

"Once a right and a violation have been shown, the

scope of a district court's equitable powers to remedy

past wrongs is broad, for breadth and flexibility are

inherent in equitable remedies." Swann v.

Charlotte-Mecklenbeurg Bd. of Education. 402 u.s. l, 15 (1971).

Nor have we in all situations "required remedial

plans to be limited to the least restrictive means of

implementation. We have recognized that the choice of remedies to redress racial discrimination is 'a balancing process left, within appropriate

constitutional or statutory limits, to the sound discretion of the trial court.' Fullllove fv.

KlhtznlCfc, 448 U.S. 448, 508 (1980)] (Powell, J.,

concurring) (quoting Eranks v,__Bowman TransportationCo,, 424 U.S. at 794 (Powell, J., concurring in part and dissenting in part) ). . . .

The district court has first-hand experience with the parties and is best qualified to deal with the

"flinty, intractable realities of . . . implementation

of constitutional commands. Swann. supra. at 6. . . .

His proximate position and broad equitable powers

mandate substantial respect for [his] judgment.

rotation of the chair of the commission.

107 S.Ct. at 1073.

17

Similarly, Justice Stevens' opinion concurring in the

judgment relied on Swann's statements that “[t]he essence of

equity jurisdiction has been the power of the Chancellor to do

equity and to mould each decree to the necessities of the

particular case," 402 U.S. at 15, and that "a district court's

remedial decree is to be judged by its effectiveness," id- at 25,

to support the conclusion that the petitioners in Paradise had

not shown that the district court's remedial order was

unreasonable. 107 S.Ct. at 1077.

Paradise makes clear that a reviewing court must accord

substantial deference to the decisions of a district court

regarding the necessary components of a remedial decree in civil

rights cases. Deference is particularly appropriate in cases

under Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act in light of the

"searching practical evaluation" of the "past and present

reality, political and otherwise" the Act requires. S.Rep.No.

97-417, p .30 (1982), and White v. Regester. 412 U.S. 755, 770

(1973); £££ Thornburg v. Gingles. 478 U.S. , , 92 L.Ed.2d

25, 106 S.Ct. at 2781 (1986). Finding a violation of the Voting

Rights Act involves an "'intensely local appraisal of the design

and impact' of the contested electoral mechanisms," id- at __, 92

L.Ed.2d at 65, 106 S.Ct. at 2781 (quoting Rogers v.Lodge. 458

U.S. 613, 622 (1982)); tailoring a remedy requires no less

intense an appraisal of the design and impact of the proposed

18

remedy.

B. The District Court Followed the Correct Procedure for

Developing a Court-Ordered Redlstrlctlng Plan______

The Alabama Legislature has not acted to replace the

1939 local act governing the election of Calhoun County

Commissioners, which violates Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act.

Accordingly, it was necessary for the district court to fashion

its own remedial plan. In doing so, it followed all the

directions given by the Supreme Court for developing

court-ordered redistricting schemes. First, it deferred to the

incumbent county commissioners, giving them the first opportunity

to propose a remedy, and witholding judicial review of it until

the Section 5 preclearance process had been completed. McDaniel

V- Sanchez. 452 U.S. 130 (1981). The U.S. Attorney General

precleared Calhoun County's plan, 649 F.Supp. at 292, leaving the

district court with the duty of reviewing it for compliance with

the following additional standards for court-ordered plans:

(1) The General Equitable Standard. The Supreme Court«

has instructed district courts fashioning redistricting plans to

defer to legitimate state policy where possible, but to prefer

single-member districts over at-large seats, to minimize

population deviations among districts, and to avoid any taint of

arbitrariness or discrimination. Connor v. Finch. 431 U.S. 407,

19

414-15 (1977), citing Chapman v . Meier. 420 U.S. 1, 26-27

(1976); Roman V,__Slncock. 377 U.S. 695, 710 (1964); Paige v.

Gray. 538 F.2d 1108, 1111-12 (5th Cir. 1976). A district court

cannot justify deviation from these requirements when there is an

alternative plan available that more nearly satisifies them.

Connor v. Finch, supra. 431 U.S. at 420.

(2) The Section 2 Remedial Standard. Where the

existing election scheme violates Section 2, the district court

must ensure that its injunction "completely remedies the prior

dilution of minority voting strength and fully provides equal

opportunity for minority citizens to participate and to elect

candidates of their choice." S.Rep.No. 97-417, p.31 (1982).

(3) The Section 2 Results Standard. No matter what

statutory or constitutional infirmity affords the basis for

striking down the existing election scheme, the district court

must ensure that the remedy it approves does not itself violate

Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act by diluting black voting

strength either in its purpose or results. Edge y. Sumter County

School District. 775 F.2d 1509, 1510 (11th Cir. 1985).

The district court properly concluded that Calhoun

County's proposed sixth commissioner elected at large failed to

meet any of the standards for a court-ordered remedy.

20

C. The Proposed At-large Chair Position Was Actually

Inconsistent with State Policy, and the District

Court Did Not Abuse Its Equitable Powers By Rejecting It. __________________________ __

Calhoun County was unable to point to compelling state

policy that would justify deviation from the exclusive use of

single-member districts in a court-ordered remedial plan. It

urged the court to create a chief executive for the county who

would be elected at large and would either serve as a sixth

voting member of the commission, as a sixth but nonvoting member

of the commission, or strictly as an executive removed from the

commission. 649 F.Supp. at 296. The written proposal did not

specify what powers and duties the chair would have, but

appellants' arguments here and in the trial court contemplate

that the chairperson will be less like another county

commissioner and more like a single-position executive with

powers none of the other commissioners possess. E.g., see

Appellants' Brief at 19-20. Whatever merit appellants might find

in such a governmental arrangement, it is not one that is

provided by Alabama law. More specifically, appellants cannot

point to authorization for a single, powerful, and elected

executive in the local law governing Calhoun County.

An essential feature of any commission form of

21

15government is shared legislative and administrative duties. The

general state law in Alabama for counties provides a commission

form of government that combines legislative, judicial and

administrative powers to be exercised by all of the

commissioners. Alabama Code Sec. 11-3-11 (1975). This is also

true for Alabama municipalities that adopt a commission form of

government. Alabama Code Secs.11-44-23, 84 and 135 (1975). There

is nothing to the contrary in the 1939 Calhoun County statute.

Calhoun County asked the court to approve a chairman whose powers

were limited only by the political skills of the Incumbent, a

form of government that does not exist anywhere else in Alabama.

The district court properly found that "[t]his proposal

fundamentally alters the form of government for the county in a

way that is unprecedented elsewhere in Alabama." 649 F.Supp. at

296.

The district court did not rule that the county

15

Shared executive/administrative and legislative duties are

inherent in a commission form of government. Standard text books

all agree on this point. R. Watson and M. Fitzgerald, Promise

and Performance of American Government 655-56 (3d ed., 1978)

("commissioners perform both legislative and executive

functions"); T. Dye, L. Greene, G. Parthemos, Governing the American Democracy 538-39 (1980) ("The commission form of city

government combines legislative and executive powers in a small

body, usually about five members"); J. Carney, Nation of Change: The American Democratic System 444 (1972) ("Commission Plan. Here

the power, both executive and legislative, is concentrated in a

policy-making commission."); M. Cummings, Jr., and D. Wise,

Democracy Under Pressure 641-42 (1977) ("The commissioners make

policy as a city council, but they also run the city departments

as administrators").

22

commission elected under the court-ordered plan would be barred

from appointing an executive officer to take responsibility for

day-to-day administration of county business. In fact, the new

commission will continue to operate as provided by the 1939 local

act in all respects save the number of commissioners and the

manner of their election. The new commission may choose to keep

the existing county administrator's position and/or assign more

or fewer executive functions to the commission chairperson. All

the disrict court held was that selection of the chair by an

at-large election method which dilutes black voting strength is

not supported by overriding state policy.

The evidence before the court showed that Calhoun

County was requesting a form of government unusual for Alabama.

Only four counties of the sixty-seven in Alabama had a mixed plan

with commissioners elected from districts and a chairman elected

at-large, and they were established by special local legislation

which the Legislature has chosen not to provide for Calhoun

County. While a number of Alabama counties use the general state

law providing for the Probate Judge to serve as chairman, that

has not been true in Calhoun County nor in most other larger

Alabama counties. In any event, as the United States argues in

United States v,__Dallas County Commission. CA No. 78-0578-BH

(S.D.Ala.):

While the probate judge is the county's chief

executive officer, the position of probate judge is

23

totally separate and distinct from the position of chairman of the county commission. The chairman,

ex-officio, does not exercise any executive duties or

administrative responsibilities involving county

commission affairs different in kind from those

performed by other county commissioners. As chairman,

ex-officio, of the county commission the chairman

(probate judge) votes only to break tie votes and

presides over meetings of the county commission.

Response of Plaintiff United States of America To Proposed

Election Plan, filed Mar. 24, 1987 (footnote omitted). In fact,

the trend is toward the practice in sixteen counties presently of

the county commissioners choosing the chair from among

themselves. Adhering to Supreme Court guidance for court-ordered

plans, the district judge correctly held that appellants had

failed to demonstrate a compelling state policy for their

proposed at-large chair or reasons why the less discriminatory

alternatives used in other counties would not operate

satisfactorily in Calhoun County as well. 649 F.Supp. at 296-97.

His findings concerning governing state policies are not clearly

erroneous, and his refusal to add an at-large executive and/or

legislative position to the new commission was not an abuse of

discretion.

A virtually identical situation was confronted by this

Court in Clark v. Marengo County. Nos. 85-7634 and 86-7703 (11th

Cir., Jan. 27, 1987) (unpublished). As remedies for at-large

election systems for the Marengo County Commission and Board of

Education found to violate Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act,

defendants submitted plans which proposed that each government

24

have an at-large elected president or chair in addition to

single-member districts. Judge Hand of the Southern District of

Alabama rejected these proposals for lack of a compelling state

reason and installed his own plan composed exclusively of

single-member districts. This court affirmed. In all relevant

respects, this case is indistinguishable from Marengo County, in

which the U.S. urged affirmance. U.S. Marengo Br.

D. The District Court Correctly Held That the County's

Proposal Failed to Remedy Fully the Violation of Section 2_________________________________________ __

The district court found that appellant's plan would do

more than simply alter the method by which the county's

government was elected: it would also fundamentally alter the way

in which the county's government operates, by usurping the powers

traditionally vested in the county commission and concentrating

them instead in a single official elected at large— the

commission chair. 649 F.Supp. at 296. In light of this finding,

the court correctly concluded that, far from curing the violation

of Section 2, the new plan would itself deny black citizens an

equal ability to participate in the political process.

The ideal of equal participation expressed in the

Voting Rights Act embodies more than being able to enter the

voting booth and cast a ballot. Put simply, "[t]he Voting Rights

Act was designed to enable minority citizens to gain access to

25

the political process and to. gain the Influence that

participation brings.“ U. S. Commission on Civil Rights, The

Stating Rights Act: Ten Years After 8 (1975) (emphasis added); see

also S.Rep.No. 97-417, p .33 (1982). Thus, the evil the Act

targets is not merely the exclusion of minorities from the voting

booth. Rather, it is the exclusion of minorities from the

process of government itself. See H.R.Rep.No. 97-227, p.14

(1982).

This exclusion can occur even when minority voters are

able to elect some government officials. When the Civil Rights

Commission surveyed the first decade of the Voting Rights Act, it

noted the presence of barriers beyond election itself to

effective minority political participation:

Not all the problems which a minority candidate

faces are those of qualifying as a candidate, running

an effective campaign, and receiving fair treatment on election day. . . . Some minorities who have been

elected have found that lack of cooperation from other

officials limits their effectiveness. And in some

places the prospect of minority success has led

communities or States to abolish the office that the minority candidate had a chance to win.

In some instances minorities have been elected to office only to find that the powers and

responsibilities of the office have been reduced, either formally or in practice.

U. S. Commission on Civl Rights, The Voting Rights Act: Ten Years

After 165-66, (1975); q £_. H.R.Rep.No. 97-227, p.ll (1982)

("electoral gains by minorities since 1965 have not . . .

26

render ted] them immune to attempts by opponents of equality to

diminish their political influence"). A remedy that dismantles

some road blocks to the election of a candidate preferred by the

black community only to re-erect them at the post-election phase

of the political process is no remedy at all.

Calhoun County's proposed "remedy" is a paradigmatic

example of the phenomenon identified by the Civil Rights

Commission: "Just at the time that the Voting Rights Act affords

blacks an equal opportunity to elect candidates of their choice

to the county commission, the persons they are able to elect

would end up with less practical political influence than that of

their previously at-large elected counterparts." 649 F.Supp. at

296. Thus, the district court would have shirked its obligation

to make certain that the scope of the remedy is commensurate with

the extent of the violation had it allowed Calhoun County to

continue to exclude blacks from effective participation in the

governance of their county by approving the unprecedented

creation of an office completely beyond their political reach.

In contrast to the proposal advanced by appellant, the

plan adopted by the district court fully cures the violation of

section 2. It both gives black voters a realistic chance to elect

a commissioner of their choice and gives that commissioner equal

practical political power. The remedy ordered by the district

court provides some protection against the danger that the locus

27

of political discrimination against the black citizens of Calhoun

County will simply shift from the voting booth to the commission

chamber by creating a structure within which each commissioner is

given a meaningful role in the governance of the county and thus

£aoh voter can "participate meaningfully" in the political

process. S.Rep.No. 97-417, p.33 (1982). On this basis, this

Court should affirm the district court's remedial order in its

entirety.

E. The District Court Correctly Found From the Totality

of Evidence That Calhoun County's Proposed At-large Chair Would Itself Violate Section 2's Results Test

The district court followed this Court's instruction in

M g e v,— Sumter County School District. 775 F.2d 1509 (nth Cir.

1985) (per curiam). to determine whether the court-ordered plan,

on its own merits, complies with Section 2. Accord Wright v.

City of Houston. 806 F.2d 635 (5th Cir. 1986). Using the

evidentiary factors listed in the Senate Report, the district

court analyzed results of the the proposed at-large chair

position and entered specific findings on each factor. 649 F.

Supp. at 294-95.

The court found that six of the seven primary factors

listed by the Senate Report were present in Calhoun County. The

court found: 1) a history of racial discrimination affecting the

28

right to vote; 2) a history of discrimination in education,

employment and health which affect blacks' current ability to

participate in the political process; 3) a historical use of

electoral devices which enhance the opportunity for

discrimination; 4) the existence of a politically cohesive black

community; 5) persistent racially polarized voting; 6) politial

campaigns characterized by appeals to racial prejudice; 7) and

the absense of successful black candidates. Id. The district

court was "convinced from the above circumstances that ... the

current requirement for at-large associate commissioners and the

requirement for an at-large chairperson commissioner, together

and separately, violate section 2." 649 F.Supp. at 295. There is

virtually no contradictory evidence in the record, and these

findings are not clearly erroneous. They provide a separate and

independent basis for affirming the judgment.

II. THIS court should REJECT THE EER £E numerical rulePROPOSED BY THE DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE.

The United States has filed a brief amicus curiae

asking this Court to adopt a per se rule: a districting scheme

proposed by a jurisdiciton found to have violated the Voting

Rights Act must be approved if it permits minorities to elect

representatives in proportion to their presence in the

popoulation, regardless of their actual relative political

29

influence. See, U. S. Br. at 8 ("For example, in a county where

blacks constitute 20% of the population, a plan that promises to

give blacks an opportunity to elect one of five representatives

GCnll net violate section 2.") (emphasis added). Under this

theory, courts would lack the power to search behind the

mathematics of the plan to assure that the actual political

processes are equally open to black voters or to assure that the

remedy fully remedies the violation of Section 2. The

Government's proposal would essentially limit the Voting Rights

Act to curing simple-minded, but not sophisticated, forms of

discrimination, q£. Gomllllon v. Llghtfoot. 364 U.S. 359 (1960),

by reading out of Section 2 altogether the "Equal Participation

Clause." It thus runs afoul of Congress' intention to remedy a

"century of obstruction," "counter the perpetuation of 95 years

of pervasive voting discrimination, not step by step, but

comprehensively and finally." S.Rep.No. 97-417, p.5 (1982).

The very language of Section 2 directs courts to

consider "the totality of circumstances in deciding whether a

challenged scheme violates the Act. Section 2(b), 42 U.S.C.

16

A results claim is established where the 'totality of the

circumstances' reveals that 'because of the challenged practice

or structure plaintiffs do not have an equal opportunity to

participate in the political processes and to elect candidates of their choice.'" 649 F.Supp. at 293, quoting 42 U.S.C. section

1973(b) and Thornburg y,__Glngles. 106 S.Ct. at 2763 (emphasis

added). The Justice Department's amicus brief assidiously avoids any mention of the Equal Participation Clause.

30

section 1973(b). The Supreme Court and Congress have explained

the contours of this inquiry. £.£., see S.Rep.No. 97-417, p.30

(1982) (the Act requires a "searching practical evaluation" of

the "past and present reality, political and otherwise") (quoting

Hhlte v, Regester, 412 u.S. 755, 770 (1973)); Thornburg v.

Glngles. 478 U.S. , _, 92 L.Ed.2d 25, 65, 106 S.Ct. 2752, 2781

(1986) (the Act demands an "'intensely local appraisal of the

design and impact' of the contested electoral mechanisms")

17(quoting Rogers v,__Lodge, 458 U.S. 613, 622 (1982) ). Adoption

of an£ per se rule would thus fly in the teeth of a longstanding

congressional and judicial policy to the contrary.

The interest claimed to justify the amicus brief is

"the Attorney General's responsibility to enforce Section 2 of

the Voting Rights Act." U.S.Br. at 1. It is particularly

disturbing to plaintiffs that the Attorney General has selected

this case, which even defendants agree presents an intensely

factual question about the dynamics of local political processes,

in which to advance a novel, mechanistic, per se rule designed

not to assure full participation for blacks but to prevent

federal courts from inquiring into the question of effective

17

Indeed, contrary to what it advocates in this case,the

United States took the position in the Supreme Court that the

determination whether an electoral procedure violates Section 2

"requires delicate judgments that can hardly be reached or

reviewed by any mechanical standard." Brief of the United States

as Amicus Curiae 6, Thornburg v. Gingles. 478 U.S.__ (1986).

31

participation at all.

A per Sfi rule resting on the presence or absence of

proportional representation is particularly inappropriate. The

Act explicitly provides that “[t]he extent to which members of a

protected class have been elected to office in the State or

political subdivision is one circumstance which may be

considered," Section 2(b) (emphasis added), as part of its

disclaimer of any Intention to make proportional representation

the touchstone of a Section 2 analysis. Thus, the Act refuses to

set a numerical upper boundary on the number of candidates that

18

the white majority can elect. The United States, however, seeks

in essence to impose precisely this kind of mechanical upper

boundary on the rights of "members of the class of citizens

protected" by the Act, surely a perverse result. And it seeks to

do so regardless of the particular facts, circumstances, and

history of the jurisdiction involved.

This is not the first time that the United States has

advanced this contention. In Thornburg v, Glngles. it argued

that a Section 2 challenge necessarily must fail when black

18

The simple fact, for example, that a community that is 20% black consistently elects 5 white council members does not

establish a violation of Section 2, absent a showing that the

electoral scheme "interacts with social and historical conditions to cause an inequality in the opportunities enjoyed by black and

white voters to elect their preferred representatives." Glngles.

478 U.S. at __ 92 L.Ed.2d at 44, 106 S.Ct. at 2764-65.

32

candidates are elected "in numbers as great as or greater than

the approximate black proportion of the population." Brief of

the United States as Amicus Curiae 25, Thornburg v. Gingles. 47819

— (1986). The Supreme Court unanimously rejected the

United States' position. Justice Brennan, writing for the Court,

acknowledged that the extent of minority political success is "a

pertinent factor" in assessing the legality of a districting

scheme. Gingles, 478 U.S. at __ ,92 L.Ed.2d at 62, 106 S.Ct. at

2779. But, he continued:

[T]he Senate Report expressly states that "the election

of a few minority candidates does not 'necessarily

foreclose the possibility of dilution of the black

vote,'" noting that if it did, "the possibility exists

that the majority citizens might evade [section 2] by manipulating the election of a 'safe' minority

candidate." The Senate Committee decided, instead, to "'require an independent consideration of the

record.'". . . Thus, the language of section 2 and its

legislative history plainly demonstrate that proof that

some minority candidates have been elected does not foreclose a section 2 claim.

(internal citations omitted); see also S.Rep.No. 97-417, p.299

(1982). Similarly, Justice O'Connor, in an opinion concurring in

the judgment and joined by the three other Justices who did not

join the Court's opinion, stated: "I do not propose that

19

According to the Court's characterization of this

position, "[essentially, appellants and the United States argue

that if a racial minority gains proportional or nearly

proportional representation in a single election, that fact alone

precludes, as a matter of law, finding a section 2 violation."

Glngles, 478 U.S. at __, 92 L.Ed.2d at 62, 106 S.Ct. at 2779.

33

consistent and virtually proportional minority electoral success

should always, as a matter of law, bar finding a section 2

violation." Singles, 478 U.s. at _, 92 L.Ed.2d at 81, 106 S.Ct.

at 2795.

The Court reached this result in Glngles despite the

fact that black voters in each of the challenged districts had

actually elected some candidates of their choice. In this case,

the Department seeks to immunize a plan from attack merely

because it offers the potential that black voters will be able to

elect one member of an emasculated commission that will be denied

the full powers granted the commission from which blacks were

excluded. The Supreme Court has directed the application of a

standard of review that "preserves the benefit of the trial

court's particular familiarity with the indigenous political

reality . . . ." Glngles. 478 U.S. at __, 92 L.Ed.2d at 65, 106

S.Ct. at 2782. In this case, the district court found that the

county's proposal offered black citizens an empty promise and

denied them equal participation in the political process. An

at-large elected member would increase the voting membership of

the county commission, would

participate as a member of the commission, and would

exercise enhanced powers enjoyed by no other member of

the commission. To that extent, the members elected by

a racially fair district election method would have

their voting strength and Influence diluted.

649 F.Supp. at 296 (emphasis added). Essentially, the district

34

court found that the county's plan would assure the retention of

all political power by the white majority and any commissioner

elected by black voters would be "safe" because he or she would

be powerless.

The Justice Department boldly asserts the legal

irrelevance of the district court's finding of fact that the

proposed at-large chair would devalue the black representative's

political Influence. "While black voters may have little

influence over the performance of [the at-large chairperson's]

duties, that is the result of it being a single-person job and

not the result of the at-large election structure." U.S. Br. at

11. The Attorney General says all that matters is arithmetic. He

says the district court was limited to counting the chair as a

sixth legislator, ignoring its executive powers, and since

Calhoun County has a 17.6% black population and 15.9% black

voting age population, a 16.7% black share of the commission

should be legally sufficient and 20% too much. Id. The amicus

brief makes no attempt to square this simple-minded rule with the

equal participation language of Section 2 or with the

congressional directive to explore all the local political

realities.

CONCLUSION

The district court's remedial order should be affirmed

35

in its entirety.

Respectfully submitted this day of April, 1987.

BLACKSHER, MENEFEE & STEIN, P.A.

Fifth Floor, Title Building

300 Twenty-First Street, North

Birmingham, AL 35203

(205) 322-7300

405 Van Antwerp Building

P. 0. Box 1051

Mobile, AL 36633

(205) 433-2000

BY ' J g A S u t s i r t , U U L tL P d e £ j LARRY MENEfEE

Terry Davis

SEAY S DAVIS

732 Carter Hill Road P. 0. Box 6215

Montgomery, AL 36106

(205) 834-2000

Julius L. Chambers

Pamela S. Karlan Lani Guinier

99 Hudson Street

16th Floor

New York, New York 10013

(212) 219-1900

¥. Edward Still

714 South 29th Street

Birmingham, AL 35233-2810

(205) 322-6631

Reo Kirkland, Jr.

307 Evergreen Avenue

P. 0. Box 646

Brewton, AL 36427

(205) 867-5711

36

Attorneys for Plaintiffs

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I do hereby certify that on this day of April, 1987,

a copy of the foregoing BRIEF FOR PLAINTIFFS-APPELLEES JOHN

DILLARD, ET AL. was served upon the following counsel of record:

Herbert D. Jones, Jr., Esq.

BURNHAM, KLINEFELTER, HALSEY,5? CATER

P. 0. Box 1618

Anniston, AL 36202 (205) 237-8515

(Calhoun County)

William Bradford Reynolds, Esq.

Assistant Attorney General

Jessica Dunsay Silver, Esq.

Irving Gornstein, Esq.

Department of Justice

Washington, D.C. 20530

by depositing same in the United States, mail postage prepaid.

37

A P P E N D I X A

Sheriff, the salary of which Deputy Sheriff shall be set by the Court of County Commissioners of Cleburne County, Alabama, and shall be payable in equal monthly installments out of the General Fund of said Cleburne County, provided however, the salary of said Deputy Sheriff shall not exceed $1 ,200.00 per year.

Section Two: On the first day of each month a statement ofthe name and amount due said Deputy Sheriff shall be furnished the Court of County Commissioners of said County by the Sheriff of said County, and it shall be the duty of the Court of County Commissioners to order a warrant drawn upon the General Fund of said County in favor of said Deputy Sheriff for the amount of the month’s salary.Section Three: All laws and parts of laws in conflict herein are expressly repealed and this Act shall be of force and effect from and after its approval by the Governor.Approved September 13, 11)31).

No. 395) (H. 730— Flowers and McGowin

AN ACT

T o provide for the manner of electing the members of the Butler County

Board of Education, and to specify the Districts from which they must

he elected.

Be it Enacted by the Legislature:

Section 1. There shall be elected by the voters of the County five (5) members of the Butler County Board of Education. One member shall be elected from each Commissioners District and shall be a bona fide resident of the District from which he is elected. There shall be one member of the Board elected from the County at large, and may reside in any part of the County..Section 2. The present members of the Board of Education shall hold office until the expiration of their respective terms, and until their successors shall have been elected and qualified.Section 3. All laws and parts of laws in conflict herewith are hereby repealed.

Section 4. This Act shall become effective immediately upon its passage and approval by the Governor.Approved September 13, 1939.

No. 420) (S. 387— Booth

/ AN ACT

v To create and establish a board to be known as the County Commission

for Calhoun County, Alabama in the place of the board of Revenue in

and for Calhoun County, Alabama, now existing in said County, and

253

)y the

i bain a,

of the

-r, the

r year,

lent of

nished

Sheriff

bounty

! Fund

unt of

herein

effect

County

■:y must

eounty

i. One

ct and

dected.

County

acation

is, and

ith are

c upon

-Booth

[mission

•enue in

ity, and

abolishing said board of revenue of Calhoun County; and dividing the

said County of Calhoun into two districts and providing for the election

of a member of said county commission from each district by vote of the

qualified electors of the entire county; and for the election of a chairman

of said county commission; defining the jurisdiction of said county com

mission, and their compensation, and conferring upon said county com

mission all the jurisdiction, powers and authority granted by law to

courts of county commissioners, boards of revenue or other governing

bodies of like kind and authority in the State of Alabama; providing for

the election of the successors of said commission; for the appointment

of a secretary of said commission and fixing his salary, and providing for

a date when said commission shall take office.

Be it Enacted by the Legislature of Alabama:

Section 1. There is hereby created and established in and for Calhoun County, Alabama, from and after the first day of January, 1943, a board to be known as the County Commission of Calhoun County, Alabama, to be composed of three members, one of whom shall be chairman of said Board, and all of whom shall be qualified voters of said County.

Section 2. 1 he Board of Revenue of Calhoun County as nowconstituted is hereby abolished to take effect upon the first day of January, 1943, and there is hereby conferred upon said County

Commission all the jurisdiction and powers which are how or may hereafter be vested by law in courts of county commissioners, board of revenue, or other like governing bodies of the several counties of this State.

Section 3. For the purpose of this act said county of Calhoun is hereby divided into two districts, numbered one, to be known as the Northern District of Calhoun County, and numbered two to be known as the Southern District of Calhoun County. District Number One shall embrace the following precincts of Calhoun County as now constituted, viz; 1, 2, 3, (i, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 16 19, 22, 23 and 24. District Number Two shall embrace the’follow- mg precincts of said County as now constituted, viz - 4 5 12 13 14, 15, 17, 18, 20 and 21.

Section 4. The members of the Board of Revenue of Calhoun County as now constituted, who are qualified and serving as members of said Board, shall continue to hold office as members of said Board of Revenue of Calhoun County until the first day of Jan-

: lllc Chairman of the present Board of Revenue shall be the Chairman of the Board of Revenue as now constituted until January 1st, 1943, and shall hold office as Chairman of said Board until said tune, it being the intention of this section that all mem.- bers of the Board of Revenue as now constituted shall remain in office with all authority and power and at same salaries now fixed by law until January 1st, 1943.

i.woeCtl°,n 5‘ T,hat at the 8cneral election to be held in November 1942, and each four years thereafter, three members of the said

W i

• A*:-.

m

m

County Commission shall be elected by the qualified electors of Calhoun County. One member shall be elected from each the nonhern and southern districts as herein created, and sha be a

resident of said district from winch he is elected, and shall be qualified elector of said county and district and shaH be edecte tho minified electors of the entire county, and shall lie a res ,n2 qialifi«d elector of saio! county. The chairman shall be

elected by Ihc qualified voters of the county, and shall be a qu.

t ied elector of said county. Each n,ember of said * “ " '-.(v over twenty one years of age, and of good moral character. The sa d members so elected shall hold office for a term of four years from and after the first day of January after their election

Vacancies in office shall be filled by appointment of the gmernor Ind any person appointed to fill a vacancy shall hold office for the ^nexp^ed term an?d until his successor shall be elected as herein

nrovided Any person appointed to fill a vacancy shall <

Sm c qualifications as to residence and character as required of

^Vectkm C^The'members of said county commission, except the

chairman shall receive as compensation an annual salary of tw hundred dollars, payable in twelve monthly installments °f on

hundred dollars each. The Chairman of said commission shall fecet" au luual satry of twenty four hundred dollars, payable

in twelve monthly installments of two hundred dollars each A o" slid salaries being payable out of the county tr-sury of sand county as provided by law for payment of salaries out of the fui

°f SectioT^' Said county commission shall elect ̂ secretarŷ

said commission, who shall keep the minutes andwork of said commission. The salary of said secretary e fixed

by the commission at a sum not less than six hundred dollars per

annum, payable monthly out of the county treasury.Section 8. All laws, general or special, in conflict with the provisions of this Act be, and the same are hereby expressly re

pealed.Approved September 13, 1939.

254

No. 421)

AN ACT

To Fstabli'h the Office of Road Engineer in and for the County of Cal

houn; T o Prescribe his Qualifications and Duties and Fix his salary a

Provide for the Method of his Election and Appointment.

Be it Enacted by the Legislature of Alabama: