Heyward v. Public Housing Administration Joint Appendix

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1953

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Heyward v. Public Housing Administration Joint Appendix, 1953. 6c5c1f24-b89a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/7bf4f29d-6632-4463-b83f-d24a41b7dd99/heyward-v-public-housing-administration-joint-appendix. Accessed February 20, 2026.

Copied!

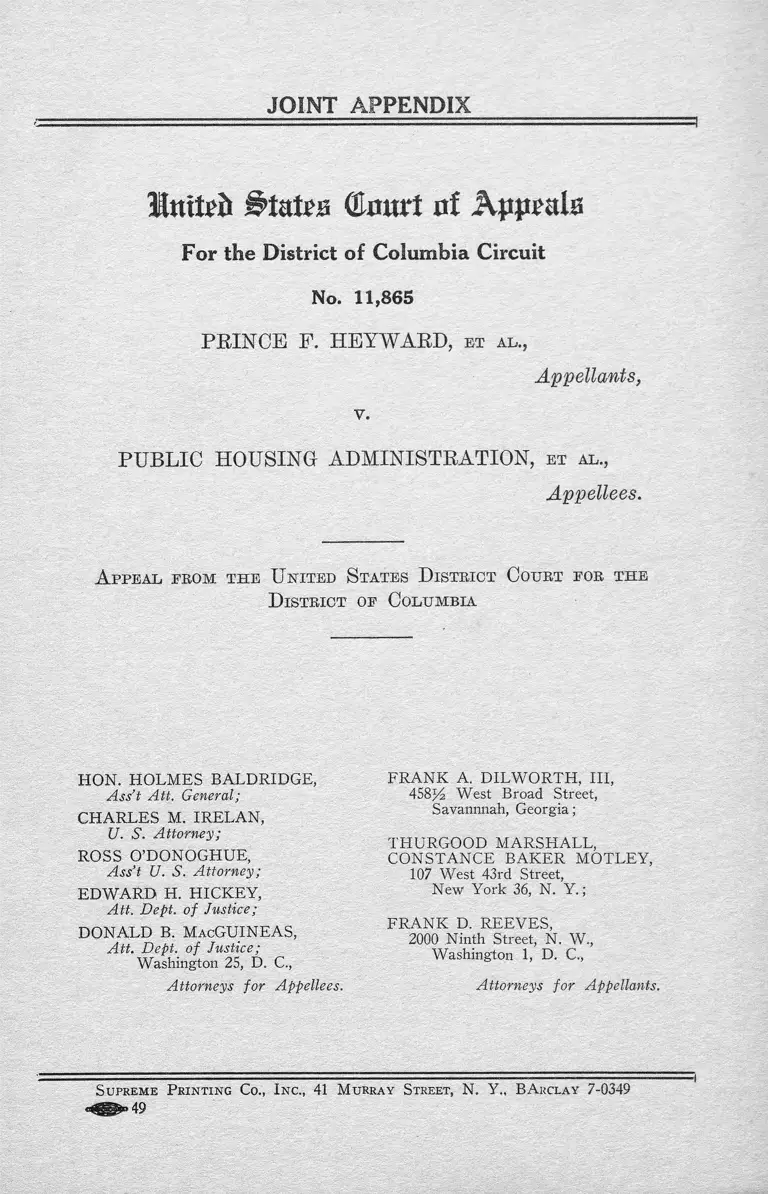

JOINT APPENDIX

Itu ttb t&mvt of Appeals

For the District of Columbia Circuit

No. 11,865

PRINCE F. HEYWARD, et al.,

Appellants,

y.

PUBLIC HOUSING ADMINISTRATION, et al.,

Appellees.

A ppeal fbom the U nited States District Court fob the

District of Columbia

HON. HOLMES BALDRIDGE,

Ass’t A tt. General;

CHARLES M. IRELAN,

U. S. Attorney;

ROSS O’DONOGHUE,

Ass’t U. S. Attorney;

EDWARD H. HICKEY,

Alt. Dept, of Justice;

DONALD B. MacGUINEAS,

A it. Dept, of Justice;

Washington 25, D. C.,

Attorneys for Appellees.

FRANK A. DILWORTH, III,

458% West Broad Street,

Savannnah, Georgia;

THURGOOD MARSHALL,

CONSTANCE BAKER MOTLEY,

107 West 43rd Street,

New York 36, N. Y.;

FRANK D. REEVES,

2000 Ninth Street, N, W.,

Washington 1, D. C,,

Attorneys for Appellants.

S upreme P rinting Co., I nc., 41 Murray Street, N. Y. BArclay 7-0349

APPENDIX

PAGE

O rder.............................................................................................. 1

Opinion.................................... 2

Complaint...................................................................................... 4

Defendants’ Motion For Summary Judgment...................... 15

Affidavit of John T. E gan ............................................................. 18

Exhibit 1 ............................................................................ 26

Exhibit 2 .......................................................... 33

Exhibit 3 .............................................................................. 34

Exhibit 4 .............................................................................. 35

Exhibit 5 .............................................................................. 50

Exhibit 6 .............................................................................. 60

Exhibit 7 ............................................................................... 62

Excerpt From Transcript of Hearing on Motion For Summary

Judgment ............................................. 63

1

JOINT APPENDIX

Order

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

F or the D istrict of Columbia

Civil Action No. 3991—52

(Filed April 28, 1953)

--------- o---------

H eyward, et al.,

v.

Plaintiffs,

H ousing a n d H ome F inance Agency, et al.,

Defendants.

-o

This cause having come on to he heard on defendants’

motion for summary judgment, and it appearing that there

is no genuine issue as to any material fact and that the

defendants are entitled to a judgment as a matter of law

in that the complaint fails to state a claim upon which

relief can he granted, it is this 28th day of April, 1953

Ordered, th a t defendants’ motion for summary judg

ment is hereby granted and the com plaint is hereby dis

missed.

Alexander H oltzoff,

District Judge.

2

Opinion

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

F ob the District1 oe Columbia

Civil Action No. 3991—52

(Filed May 8, 1953)

----------------o---------- -----

H eyward, et al.,

v.

Plaintiffs,

H ousing and H ome F inance Agency, et al.,

Defendants.

-o

The Court: This is an action to restrain the Commis

sioner of the Public Housing1 Administration from advanc

ing any funds under the United States Housing Act of 1937,

as amended, and otherwise participating, in the construc

tion and operation of certain housing projects in the City

of Savannah, Georgia.

These projects are being constructed and will be

operated by local authorities with the aid of Federal Funds.

The basis of the action is that it has been officially

announced that the project referred to in the complaint

will be open only to white residents. The plaintiffs are

people of the colored race who contend that such a limita

tion is a violation of their Constitutional rights.

The Court has grave doubt whether this action lies in

the light of the doctrine enunciated in the case of Massa

chusetts v. Mellon, 262 U. S. 447, but assuming, arguendo,

that the action may be maintained, the Court is of the

opinion that no violation of law or Constitutional rights

on the part of the defendants has been shown.

3

Opinion

I t appears from the affidavit submitted in support of the

defendants’ motion for a summary judgment that there

are several projects that have been or are being con

structed in the City of Savannah under the Housing Act,

some of which are limited to white residents and others to

colored residents, and that a greater number of accom

modations has been set aside for colored residents. In

other words, we have no situation here where colored people

are being deprived of opportunities or accommodations

furnished by the Federal Government that are accorded to

people of the white race. Accommodations are being ac

corded to people of both races.

Under the so-called “ separate but equal” doctrine,

which is still the law under the Supreme Court decisions,

it is entirely proper and does not constitute a violation

of Constitutional rights for the Federal Government to

require people of the white and colored races to use separate

facilities, provided equal facilities are furnished to each.

There is another aspect of this matter which the Court

considers of importance. The Congress has conferred

discretionary authority on the administrative agency to

determine for what projects Federal funds shall be used.

There are very few limitations in the statute on the power

of the administrator, and there is no limitation as to racial

segregation.

The Congress has a right to appropriate money for such

purposes as it chooses under the General Welfare clause

of Article I, Section 8, of the Constitution. It has a right

to appropriate money for purpose “ A” but not for pur

pose “ B ”, so long as purpose “ A ” is a public purpose.

Under the circumstances, the Court is of the opinion

that the plaintiffs have no cause of action and the defend

ants’ motion for summary judgment is granted.

(Thereupon, the above entitled matter was concluded.)

Alexander H oltzoef,

District Judge.

4

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

F ob the D istrict of Columbia

Civil Action No............

-------------------o-------------------

1. P rince F . H eyward

230 Reynolds Street

Savannah, Georgia

2. E rsaline. Small,

650 E. Oglethorpe Avenue

Savannah, Georgia

3. W illiam Mitchell

226 Arnold Street

Savannah, Georgia

4. W illiam Golden

230 Arnold Street

Savannah, Georgia

5. Mike Maustipher

656 E. Oglethorpe Avenue

Savannah, Georgia

6. W illis H olmes

321 E. Boundary Street

Savannah, Georgia

7. Alonzo Sterling

158 E. Boundary Street

Savannah, Georgia

8. Martha Singleton

156 E. Boundary Street

Savannah, Georgia

9. I rene Chisholm

623 E. Oglethorpe Avenue

Savannah, Georgia

Complaint

5

Complaint

10. J ohn F uller

170 E. Boundary Street

Savannah, Georgia

11. Benjamin E. S immons

647 E. Jackson Street

Savannah, Georgia

12. J ames Young

636 Wheaton Street

Savannah, Georgia

13. Ola Blake

214 Reynolds Street

Savannah, Georgia

Plaintiffs,

v.

1. H ousing and H ome F inance Agency

Serve:

Raymond M. F oley, Administrator

Normandy Building-

1626 K Street, N. W.

Washington 25, D. C.

2. Raymond M. F oley, Administrator

H ousing and H ome F inance Agency

Normandy Building

1626 K Street, N. W.

Washington 25, D. C.

3. P ublic H ousing Administration,

body corporate,

Serve:

J ohn T. E gan, Commissioner

Longfellow Building

1201 Connecticut Avenue, N. W.

Washington 25, D. C.

4. J ohn T. E gan, Commissioner

P ublic H ousing Administration

Longfellow Building

1201 Connecticut Avenue, N. W.

Washington 25, D. C.

Defendants

6

1. The jurisdiction of this court is involved pursuant

to Title 28, United States Code, Section 1331, this being a

suit which arises under the Constitution and laws of the

United States, that is, the Fifth Amendment to the Con

stitution of the United States and Title 42, United States

Code, Sections 1401-1433, as amended (Housing* Act of

1937 as amended by the Housing Act of 1949), and Title 8,

United States Code, Sections 41 and 42, wherein the mat

ter in controversy as to each of the plaintiffs exceeds Three

Thousand Dollars ($3,000) exclusive of interests and costs.

2. This is a proceeding for a temporary and permanent

injunction enjoining the Housing and Home Finance

Agency, the Administrator of the Housing and Home

Finance Agency, the Public Housing Administration and

the Commissioner of the Public Housing Administration

from giving federal financial assistance and/or other federal

assistance to the Housing Authority of Savannah, Georgia,

for the construction and/or operation of a public low-rent

housing project, pursuant to the provisions of the Housing

Act of 1937 as amended by the Housing Act of 1949, from

which the plaintiffs, although otherwise qualified for admis

sion, will be excluded and denied consideration for admis

sion and/or admission solely because of their race and color,

in violation of the Constitution and laws of the United

States.

3. This is a proceeding for a declaratory judgment

pursuant to Title 28, United States Code, Section 2201, for

the purpose of determining a question in actual controversy

between the parties, i.e., whether the defendants and each

of them can give federal financial assistance and/or other

federal assistance to the Housing Authority of Savannah,

Georgia, for the construction and/or operation of a public

low-rent housing project pursuant to the provisions of the

Housing Act of 1937, as amended by the Housing Act of

Complaint

7

1949, from which the plaintiffs will he excluded from con

sideration for admission and/or denied admission, although

otherwise meeting the qualifications for such consideration

and admission established by law, solely because of their

race and color, without violating any rights secured to

the plaintiffs and each of them, individually by the Consti

tution and laws of the United States, particuarly the Fifth

Amendment to the Constitution of the United States, and

Title 42, United States Code, Sections 1401-1431, and Title

8, United States Code, Sections 41 and 42, and without

violating the public policy of the United States.

4. This is a class action pursuant to Rule 23(a) of the

Federal Rules of Civil Procedure brought by the plaintiffs

on behalf of themselves and on behalf of other persons

similarly situated, that is, Negro citizens of the United

States and of the State of Georgia who are residents of

the City of Savannah, Georgia, and who reside on a site

in the City of Savannah, Georgia, commonly known as the

“ Old Fort Area”, which has been condemned by or on

behalf of the Housing Authority of Savannah, Georgia, a

public agency, for the purpose of constructing thereon a

low-rent public housing project to be known as the Fred

Wessels Homes (designated by defendants as GA-2-4) pur

suant to the provisions of the Housing Act of 1937, as

amended by the Housing Act of 1949, and who will be dis

placed from said site by reason of the construction of said

project and who will, in accordance with the announced

policy, program, and plan of the Housing Authority of

Savannah, Georgia, which has been approved by these

defendants consistent with their policy and practice of

furnishing financial assistance to local public agencies for

the provision of racially segregated low-rent housing

projects, be denied consideration for admission and/or

admission to said project, although they meet all of the

Complaint

8

Complaint

requirements established by law for such consideration

and admission to said bousing project solely because of

their race and color. Said persons constitute a class too

numerous to be brought individually before the court but

there are common questions of law and fact involved herein,

common grievances arising out of common wrongs, and

common relief sought for the entire class as well as special

relief for the plaintiffs. The interests of said class are

fairly and adequately represented by the plaintiffs herein.

5. Each of the plaintiffs is an adult Negro citizen in the

United States and of the State of Georgia, Each of the

plaintiffs resides in the City of Savannah, Georgia, on a site

commonly known as the “ Old Fort Area” . Each of the

plaintiffs will be displaced from such site by reason of the

fact that the said site has been condemned by or on behalf

of the Housing Authority of Savannah, Georgia, a public

agency, for the purpose of constructing thereon a low-rent

housing project pursuant to the provisions of the Housing

Act of 1937, as amended by the Housing Act of 1949. Each

of the plaintiffs meets the requirements established by law

for consideration and admission to the said low-rent public

housing project. Each of the plaintiffs is entitled by Title

42, United States Code, Section 1410(g) to a preference for

consideration and admission to any public low-rent, housing

project built in the City of Savannah, Georgia, pursuant to

the provisions of the Housing Act of 1937 as amended by

the Housing Act of 1949, by reason of the fact that his or

her family will be displaced from a site on which a low-

rent public housing project will be built.

6. The defendant, Housing and Home Finance Agency

is an agency of the United States Government established

pursuant to Reorganization Plan No. 3, effective July 27,

1947 (Title 5, United States Code, Section 133 (y-16)’

which consists of three constituent agencies, one of which

9

is the defendant Public Housing* Administration. The

Housing* and Home Finance Agency is headed by an Admin

istrator, defendant Raymond M. Foley, who is responsible

for the “ general supervision and coordination of the func

tions of the constituent agencies of the Housing and Home

Finance Agency” (Reorganization Plan No. 3, 1947, Sec

tion 5(b)).

7. Defendant Public Housing Administration, a con-

stitutent agency of the Housing and Home Finance Agency,

under the supervision of defendant Administrator Ray

mond M. Foley, pursuant to Reorganization Plan No. 3,

effective July 27, 1947 (Title 5, Section 133 (y-16), is a

corporate agency and instrumentality of the United States

Government. The Public Housing* Administration is headed

by a Commissioner, defendant John T. Egan. The de

fendant Public Housing Administration administers the

Housing Act of 1937, as amended by the Housing Act of

1949 (Title 42, United States Code, Section 1401-1433).

8. The Housing Act of 1937, as amended by the Housing

Act of 1949, provides for federal financial assistance in the

form of grants, loans, and annual contributions to local

public housing agencies for the construction and/or opera

tion of public low-rent housing projects built pursuant to

the provisions and in accordance with the purposes of the

Housing Act of 1937, as amended by the Housing Act of

1949.

9. Pursuant to the provisions of the Housing Act of

1937, as amended by the Housing Act of 1949, the defendant

Public Housing Administration has entered into a con

tract with the Housing Authority of Savannah, Georgia,

pursuant to the provisions of which the Public Housing

Administration and the Commissioner of the Public Hous

ing Administration, with the approval of the other de

Complaint

10

fendants, have agreed to give federal financial assistance

to the Housing Authority of Savannah, Georgia, for the

construction and/or operation of a public low-rent housing

project to be constructed and maintained by the Housing

Authority of Savannah, Georgia, pursuant to the provisions

of the Housing Act of 1937, as amended by the Housing Act

of 1949. Said public low-rent housing project will be known

as the Fred Wessels Homes and has been designated by

defendant Public Housing Administration and the de

fendant Commissioner of the Public Housing Adminis

tration as GA—2-4. Said project will be constructed on a

site in the City of Savannah, Georgia, commonly known as

the “ Old Fort Area”, on which the plaintiffs reside and

from which they will be displaced by reason of such con

struction. The Housing Authority of Savannah, Georgia,

has condemned the site and has acquired title thereto and

has proceeded to demolish the buildings thereon for the

purpose of constructing thereon said public low-cost hous

ing project.

10. The Housing Authority of Savannah, Georgia, has,

as a prerequisite to the securing of the agreement for fed

eral financial assistance from the defendant Public Housing

Administration and the defendant Commissioner of the

Public Housing Administration, submitted to said de

fendants a plan and program for the approval of said

defendants. Said plan and program describes the site

on which the project would be built in terms of its present

racial characteristics and specifies that occupancy of the

said project to be built thereon would be limited to white

families.

11. Said plan and program, specifying that the occu

pancy of the said project would be limited to white families,

has been approved by the defendant Public Housing Ad

Complaint

11

ministration and the defendant Commissioner of the Public

Housing Administration. Said plan and program was ap

proved by the defendant Public Housing Administration

and the defendant John T. Egan with the knowledge, con

sent, and approval of the other defendants. Pursuant to

said approval, the defendant Public Housing- Administra

tion and the defendant Commissioner of the Public Housing

Administration entered into said contract for the provision

of federal financial assistance to the Housing Authority of

the City of Savannah, Georgia, for the construction and/or

operation of the said project.

12. The Housing Authority of the City of Savannah,

Georgia, has specifically announced that, in accordance with

its policy, occupancy of said low-rent public housing proj

ect will be limited to white occupancy. Thus, the plaintiffs,

who are Negroes, will not be considered for admission

and/or admitted thereto solely because of their race or

color. The defendant Public Housing Administration, and

the other defendants have specific knowledge of this an

nounced policy and have approved said policy and have

approved the plan and program specifically indicating

this policy and have agreed to give federal financial assis

tance to construct and/or operate the project where said

policy, plan, and program will be put into effect in violation

of the right conferred upon the plaintiffs and each of them

to a preference for consideration and admission to any

public low-rent housing project in the City of Savannah,

Georgia, built pursuant to the Housing Act of 1937 as

amended by the Housing Act of 1949, as persons displaced

from the site, and in violation of the rights secured to the

plaintiffs and each of them individually by the Fifth Amend

ment to the Constitution of the United States and in viola

tion of the duty imposed upon the defendants by the

Housing Act of 1937, as amended by the Housing Act of

Complaint

12

1949, and in violation of rights secured to the plaintiffs

and each of them individually by Title 8, United States

Code, Sections 41 and 42, and in violation of the public

policy of the United States.

13. The plaintiffs herein will be denied consideration

for and/or housing, for which they are otherwise qualified,

by the Housing Authority of Savannah, Georgia, with the

aid, support, and financial assistance of the defendants

herein solely because of their race and color, unless such

injury and violation of rights is enjoined by this court.

14. The plaintiffs, and each of them, will suffer irrepar

able injury, for which there is no adequate remedy at law,

by the violation of these rights by the defendants herein

unless injunctive relief is granted by this court.

15. Each of the defendants is under a duty to discharge

his or its duties in conformity with the laws, Constitution,

and public policy of the United States.

W hebh fo k e , plaintiffs respectfully pray this court that

upon the filing of this complaint, as may appear1 proper

and convenient to the court, the court advance this cause

on the docket and order a speedy hearing of this action

according to the law and that this court, upon said hearing,

1. Adjudge, decree and declare the rights and other

legal relations of the parties to the subject matter here in

controversy in order that said declaration shall have the

force and effect of a final judgment;

2. Enter a final judgment or decree declaring (a) that

the defendants and each of them cannot give federal finan

cial assistance or other federal assistance to the Housing

Authority of Savannah, Georgia, for the construction

Complaint

13

and/or operation of a public low-rent bousing’ project pur

suant to the provisions of the Housing Act of 1937, as

amended by the Housing Act of 1949, from which the plain

tiffs and other qualified Negroes similarly situated will be

excluded and denied consideration for admission and/or

admission solely because of their race and color in violation

of the Constitution, laws, and public policy of the United

States; (b) that the plaintiffs and all other Negroes simi

larly situated cannot be denied consideration for admission

and/or admission to the Fred Wessels Homes or any other

federally-aided housing project solely because of their

race and color; (c) that the plaintiffs and all other Negroes

similarly situated must be considered for admission and/or

admitted to the Fred Wessels Homes or any other feder

ally-aided housing project; (d) that the preference for

admission to the Fred Wessels Homes or any other fed

erally-aided low-rent housing project in the City of Savan

nah, Georgia, conferred on plaintiff's and all other Negroes

similarly situated by Section 1410(g) of Title 42, United

States Code, may not be qualified or limited by race or

color.

3. Issue a temporary injunction restraining and en

joining the defendants and each of them, their ag’ents,

representatives, and successors in office from giving fed

eral financial assistance and/or other federal assistance

to the Housing Authority of Savannah, Georgia, for the

construction and/or operation of a public low-rent hous

ing project pursuant to the provisions of the Housing Act

of 1937, as amended by the Housing Act of 1949, from which

the plaintiffs and other Negroes similarly situated will be

excluded and denied consideration for admission and/or

admission solely because of their race and color.

4. Issue a permanent injunction restraining and en

joining the defendants and each of them, their agents, rep

Complaint

14

resentatives, and successors in office from giving federal

financial assistance and/or other federal assistance to the

Housing Authority of Savannah, Georgia, for the con

struction and/or operation of a public low-rent housing-

project pursuant to the provisions of the Housing Act of

1937, as amended by the Housing Act of 1949, from which

the plaintiffs and other Negroes similarly situated will be

excluded and denied consideration for admission and/or

admission solely because of their race and color.

5. And for such other and further relief as to the Court

shall seem just and proper.

T hubgood Mabshall,

Constance Bakes Motley,

20 West 40th Street,

New York 18, New York;

J ulius T. W illiams,

719% West Broad Street,

Savannah, Georgia;

F bank I). B eeves,

1901 Eleventh Street, N. W.,

Washington 1, I). C.,

Attorneys for Plaintiffs.

Complaint

15

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

Defendants’ Motion for Summary Judgment

F ob, the Distbict oe Columbia

Civil Action No. 3991-52

--------- o---------------—

H eywabd, et al.,

Plaintiffs,

v.

H ousing and H ome F inance A gency, et al.,

Defendants.

■o

Now come defendants, by their attorneys, and move the

Court for summary judgment of dismissal of the complaint

on the ground that there is no genuine issue as to any

material fact and that defendants are entitled to a judg

ment as a matter of law for the following reasons:

1. This Court has no jurisdiction over defendant Hous

ing and Home Finance Agency, which is an agency in the

Executive Branch of the Government not subject to suit.

2. The complaint fails to state a claim upon which

relief can be granted.

3. There is no case or controversy between plaintiffs

and defendants with respect to any actual, adverse issue

involving the parties’ legal rights or obligations.

4. The action is premature in that plaintiffs are not

threatened with any immediate irreparable injury. The

injury of which plaintiffs complain is that they will be

16

excluded from occupancy, solely because of their race and

color, of a low-rent housing project, Project GA-2-4 (known

as ‘‘Fred Wessels Homes” ), now under construction by the

Housing Authority of Savannah, Georgia. This project

will not be ready for occupancy until approximately March,

1954. Accordingly, plaintiffs cannot suffer any injury at

this time.

5. Plaintiffs are not, and will not be, denied any prefer

ence in occupancy of low-rent housing projects to which

they may be entitled by virtue of 42 U. S. C. 1410(g).

Plaintiffs, as persons displaced from the site of Project

GA-2-4 and as members of low-income families which are

eligible applicants for occupancy, are being- given and will

be given preference, to the extent provided by law, in occu

pancy of low-rent housing projects in Savannah owned

and operated by the Housing Authority of Savannah.

6. Defendants have not taken, and are not threatening

to take any action which will deprive plaintiffs of their

asserted right to preference in occupancy of any of the

low-rent housing projects in Savannah owned and operated

by the Housing Authority of Savannah, Georgia. Defend

ants do not impose any restrictions upon the occupancy of

said projects on the basis of applicants’ race or color.

Any such restrictions in occupancy on the basis of race or

color are imposed solely by the Housing Authority of

Savannah. Hence, plaintiffs ’ complaint is against the acts

of the Housing Authority of Savannah, not against any

acts performed or threatened by defendants.

7. There is no actual controversy between plaintiffs

and defendants as to plaintiffs’ alleged right to have

Project GA-2-4 rented on a racially non-segregated basis.

Defendants have taken and now take no position as to

whether plaintiffs do or do not have such alleged right.

Defendants’ Motion for Summary Judgment

17

8. Plaintiffs have no legal interest in the expenditure

of Federal funds for Project GA-2-4 and hence have ho

standing to sue to enjoin such expenditure.

9. The relief sought by plaintiffs, to enjoin defendants

from giving any Federal financial assistance to the Housing

Authority of Savannah for the construction of a low-rent

housing project from which plaintiffs will be excluded

solely on the basis of their race or color would be futile.

The granting of such relief would not open Project GA-2-4

to occupancy by the plaintiffs; on the contrary, it would

merely prevent the construction of said project and thereby

deprive other low-income families in addition to plaintiffs

of an opportunity to obtain such housing without affording

any benefit to plaintiffs.

10. There is a lack of an indispensable party—the Hous

ing Authority of Savannah, which prescribes the policies

of occupancy of this project on the basis of race and color.

This Housing Authority is a municipal corporation of the

State of Georgia, is not joined as a defendant in this action,

and is not subject to suit within the jurisdiction of this

Court.

H olmes Baliridge,

Assistant Attorney General;

Charles M. I relan,

United States Attorney;

Ross 0 ’Donoghtje,

Assistant United States Attorney;

E dward H. H ickey,

Attorney, Department of Justice;

Donald B. MacGuineas,

Attorney, Department of Justice,

Attorneys for Defendants.

Defendants’ Motion for Summary Judgment

18

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

F or the District1 of Columbia

Civil Action No. 3991-52

Affidavit of John T. Egan in Support of Defendants’

Motion for Summary Judgment

--------- o----------

H eyward, et al.,

v.

Plaintiffs,

H ousing and H ome F inance Agency,

Defendants.

-------------------o-------------------

District of Columbia )

City of W ashington ^

J ohn T. E gan, being first duly sworn deposes and states:

1. I am the Commissioner of the Public Housing Ad

ministration, which is an agency within the executive depart

ment of the Federal Government and a constitutent agency

of the Housing and Home Finance Agency, an independent

agency in the executive branch of the Federal Government.

2. As Commissioner of the Public Housing Administra

tion I am vested with the function of administering the

low-rent housing program of the Federal Government pro

vided by the Housing Act of 1937, as amended by the Hous

ing Act of 1949 (42 U. S. C. 1401-33).

3. Under the low-rent housing program, low-rent hous

ing projects to provide dwellings within the financial reach

19

of families of low income are constructed, owned and

operated by a State, county or municipal public housing

agency, referred to in this affidavit as a “ local authority.”

The function of the Public Housing Administration is to

provide financial assistance to the local authorities in the

development and administration by them of low-rent hous

ing projects.

4. Such financial assistance may take the form of (1)

loans to local authorities pursuant to 42 U. S. C. 1409,

(2) annual contributions to local authorities to assist in

achieving and maintaining the low-rent character of their

housing projects pursuant to 42 U. S. C. 1410, (3) capital

grants to local authorities to assure the low-rent character

of their projects pursuant to 42 U. S. C. 1411.

5. (a) Where a development plan for low-rent housing

projects is submitted by the local authority to the Public

Housing Administration for financial assistance which in

volves the use of slum sites with consequent displacement

of site occupants, the regulations of the Public Housing

Administration require the local authority to demonstrate

to the satisfaction of the Public Housing Administration

that relocation of site occupants is feasible by showing that

with respect to displaced families apparently eligible for

public low-rent housing, such families can be offered dwell

ings in low-rent housing projects at the time of displace

ment or that they can reasonably be expected to find

temporary dwelling accommodations of some kind and

later be accommodated in low-rent housing projects (Low-

Rent Housing Manual, Section 213.2, a copy of which is

attached to this affidavit as Exhibit 1).

(b) The regulations of the Public Housing Adminis

tration further require that programs for the development

of low-rent housing must reflect equitable provision for eli

Affidavit of John T. Egan

20

gible families of all races determined on the approximate

volume and urgency of their respective needs for such hous

ing (Low-Bent Housing Manual, Section 102.1, a copy of

which is attached to this affidavit as Exhibit 2).

(c) The regulations further require that sites for pub

lic housing projects shall be selected in such manner as to

make possible the application of the policies on racial equity

in tenant selection referred to above; that the number of

dwelling units which are developed for racial minority

occupancy shall not be less than the number of units de

stroyed which are in racial minority occupancy; that the

selection of sites should not result in a material reduction

in the land area in the locality available to racial minority

families; that every effort be made to avoid the selection

of sites which will result in the displacement of minority

group populations; and that the use of congested slum

sites occupied predominantly by racial minority groups

should be made only where the local authority can demon

strate that relocation of site occupants in accordance with

regulations of the Public Housing Administration is feasi

ble (Low-Bent Housing Manual, Section 208.8, a copy of

which is attached to this affidavit as Exhibit 3).

6. While, as stated above, the Public Housing Adminis

tration requires the development programs of local au

thorities to make equitable provision for eligible families

of all races, the policy of the Public Housing Administra

tion with respect to whether or not a particular low-rent

housing project shall be operated by the local authority on

a racially segregated or non-segregated basis is that the

determination of that question is entirely one for the local

authority. The Public Housing Administration has not

and would not interpose any objection to a determination

by a local authority to operate such a project on a racially

non-segregated basis.

Affidavit of John T. Egan

21

7. Low-rent housing projects in the City of Savannah,

Georgia, for which financial assistance is provided by the

Public Housing Administration are constructed, owned and

operated by the Housing Authority of Savannah, a munici

pal corporation organized under the Housing Authorities

Law of the State of Georgia (Act Number 411 of the Laws

of 1937, as amended). At the present time five low-rent

housing projects have been completed and are being oper

ated by the Housing Authority of Savannah. These are

Projects GA-2-1, with 176 dwelling units for Negroes,

GA-2-2 with 480 dwelling units for Negroes; GA-2-3, with

314 dwelling units for whites; GA-2-5, with 127 dwelling

units for Negroes; and GA-2-6, with 86 dwelling units for

whites.

8. The status of the low-rent housing project specifi

cally referred to in the complaint in this action, No. GA-2-4

(known as Fred Wessels Homes) is as follows:

(a) On September 22, 1949, the Housing Authority of

Savannah filed with the Public Housing Administration an

application for a program reservation for four projects

totaling 800 low-rent dwelling units, consisting of Projects

GA-2-5 and GA-2-6 (referred to above), GA-2-4 to contain

250 dwelling units for wdiites, and GA-2-7 to contain 337

dwelling units for Negroes, together with an application

for a preliminary loan necessary to inaugurate such a hous

ing program. On November 8, 1949, and again on October

1, 1951, the Public Housing Administration issued such

program reservation for these 800 dwelling units in accord

ance with the application submitted by the Housing Au

thority of Savannah.

(b) On September 12, 1950, the Housing Authority of

Savannah and the Public Housing Administration entered

into a preliminary loan contract (a copy of which is attached

to this affidavit as Exhibit 4) under which the Public Hous

Affidavit of John T. Egan

22

ing Administration agreed to loan to the Housing Authority

of Savannah not to exceed $210,000 for use in making pre

liminary surveys and planning for low-rent housing proj

ects. On March 19,1952, the Housing Authority of Savannah

and the Public Housing Administration entered into an an

nual contributions contract under which the Public Housing-

Administration agreed to lend to the Housing Authority

of Savannah $2,292,000, bearing interest at 2%% per an

num, to cover the estimated development cost of said

project and agreed to make annual contributions to the

Housing Authority of Savannah to provide funds necessary

to meet the annual payments of interest and amortization

of principal of the funds borrowed by the Housing Au

thority of Savannah for the development of that project.

A copy of Part One of said annual contributions contract

is attached to this affidavit as Exhibit 5. A copy of Part

Two of said annual contributions contract is attached to

this affidavit as Exhibit 6. On July 24, 1952, the Housing

Authority of Savannah and the Public Housing Administra

tion entered into Amendatory Agreement No. 1 to said

annual contributions contract by which the principal amount

of the Public Housing Administration loan was changed

from $2,292,000 to $2,792,000. A copy of said Amendatory

Agreement No. 1 is attached to this affidavit as Exhibit 7.

(c) On May 20, 1952, the Housing Authority of Savan

nah entered into a contract with the Byck-Worrell Con

struction Company of Savannah for the construction of

Project G-A-2-4, with a construction period of 460 days

after the issuance of a notice to proceed. Work under this

contract has, however, been delayed because of difficulty in

obtaining the approval of the City Council of Savannah to

the lay-out of the project. At the present time the only

work done consists of work in connection with the assem

bling and clearing of the site. Revised drawings were

submitted to the contractor on November 6, 1952, for a new

Affidavit of John T. Egan

23

cost estimate. Such estimate has not yet been received;

and upon its receipt, it must be approved by the Public

Housing Administration. Assuming such estimate is ap

proved by December 15, 1952 (the earliest date likely), it

is estimated that, based on a construction period of 460

days, Project GA-2-4 will not be completed and available

for occupancy until the latter part of March, 1954.

(d) Up to the present the Public Housing Administra

tion has advanced to the Housing Authority of Savannah

under the annual contributions contract the sum of $939,567.

9. (a) As appears from the preceding paragraphs of

this affidavit, the low-rent housing program of the Housing

Authority of Savannah, including projects completed and

planned, consists of the following:

Affidavit of John T. Egan

Dwelling Units Dwelling Units

Project No. for Whites for Negroes

GA-2-1 176

GA-2-2 480

GA-2-3 314

GA-2-4 250

GA-2-5 127

GA-2-6 86

GA-2-7 337

Totals 650 1,120

Percentage of

Total 36.7% 63.3%

(b) The percentage distribution of low-rent housing

required to achieve racial equity, based on the volume of

substandard housing as estimated by the Director of the

Atlanta Field Office of the Public Housing Administration

on the basis of a 1950' census of housing prepared by the

24

Bureau of Census, Department of Commerce, is white

33.7%, Negro 66.3%. I am informed by the Director of the

Atlanta Field Office of the Pulbic Housing Administration

that the Housing Authority of Savannah contemplates sub

mitting an application for another low-rent housing project

(in addition to the seven projects listed above) to consist

of 800 dwelling units for Negro occupancy.

10. I am informed by the Housing Authority of Savan

nah that the occupants of the site of Project GA-2-4 were

78% Negroes and 22% whites. The seven low-rent housing-

projects in Savannah listed above (and in addition the

eighth project contemplated by the Housing Authority of

Savannah, in the event it is constructed) are, or when con

structed will be, available for occupancy by low-income

families displaced from the site of the Project GrA-2-4 who

are otherwise eligible for occupancy of such projects, in

the relative preferences prescribed by 42 U. S. C. 1410(g).

11. In view of the policy of the Public Housing Admin

istration set forth in paragraph 6 of this affidavit to leave

to the determination of the Housing Authority of Savannah

the question as to whether Project GA-2-4 shall be operated

by that Authority on a racially segregated or non-segre-

gated basis, it is my opinion that no real dispute exists

between the plaintiffs and the defendants in this action as

to whether or not the plaintiffs have any legal right to have

said project operated on a non-segregated basis.

12. In my opinion, the issuance of any order by this

Court prohibiting the Public Housing Administration from

rendering financial assistance to the Housing Authority

of Savannah in the construction and operation of Project

GA-2-4 will not provide any additional low-rent housing

accommodations to plaintiffs. The only effect of such an

order would be to prevent construction of Project GA-2-4

Affidavit of John T. Egan

Affidavit of John T. Egan

and thereby reduce the number of low-rent dwelling units

available in Savannah for other low-income persons eligi

ble for occupancy of such projects.

J ohn T. E gan

Commissioner of Public Housing

Administration

City of W ashington 1 *District of Columbia j

Subscribed and sworn to before me this day

of

Notary Public

26

HHFA

PHA

5-15-51 LOW-RENT HOUSING MANUAL 213.2

Relocation of Site Occupants

1. Introduction

a. If a Local Authority proposes to use a slum site, in

order that displacement of site occupants will not result

in undue hardship to such occupants, the Local Authority

shall:

(1) As a condition to preliminary approval of the site

demonstrate to the satisfaction of the PHA (in

accordance with paragraph 2 below) that relocation

of site occupants is feasible;

(2) As a condition to approval of the Development

Program establish a plan satisfactory to the PHA

for relocating site occupants; and

(3) In the Annual Contributions Contract agree to

carry out the relocation plans set forth in the

Development Program.

Proposals for use of slum sites involving the displace

ment of minority groups will be subject to careful scrutiny

by the PHA, because such groups are often seriously re

stricted as to the neighborhoods in which they can find other

dwellings.

b. Suggested procedures for setting up and staffing a

Housing Advisory Office and for effecting the removal of

site occupants will be contained in a Low-Rent Housing

Bulletin.

Exhibit 1

N ote: This Section supersedes Section 213.2, dated 10-

13-50. The entire release has been revised.

27

2. Demonstration of Feasibility'

a. To demonstrate the feasibility of relocation the

Local Authority must show:

(1) A reasonably sound estimate of the number of

families to be displaced from the site, including

appropriate data as to income and race;

(2) The approximate time of displacement, particu

larly when demolition and rebuilding is to be car

ried out in stages;

(3) With respect to families apparently eligible for

public low-rent housing, that such families can

be offered dwellings in low-rent housing projects

at the time of displacement or that they can

reasonably be expected to find temporary dwelling

accommodations of some kind and later be accom

modated in low-rent housing projects;

(4) With respect to families not eligible for public

low-rent housing, that they can reasonably be ex

pected to find dwelling accommodations no worse

than those on the site and at rents within their

financial means.

b. The demonstration of feasibility must recognize any

restrictions in the supply of housing for minority group

families.

c. The demonstration must recognize the demands of

any other relocation which will take place in the community,

particularly any slum clearance assisted under Title I of

the Housing Act of 1949.

d. The demonstration shall be made in the form of

Item 223 of the Development Program and must be sub

mitted before the PHA will give tentative approval of the

site (see Manual Section 208.1).

Exhibit 1

Exhibit 1

3. Relocation Plan

a. The Local Authority shall prepare a relocation plan

with respect to assisting- the occupants of the site to find

other quarters. Such plan shall include the proposals which

the Local Authority considers necessary for the provision

for personnel to handle relocation, an office at the site or

elsewhere at which families may obtain information, survey

of site occupants to determine individual family rehousing

needs and problems, notification to families of the avail

ability of advice and assistance in finding other quarters,

arrangements for obtaining information on vacancies, in

spection of any vacanies to which families not eligible for

public low-rent housing are to be referred, arrangements

for obtaining the cooperation of other community agencies,

arrangements for coordinating the relocation activities

of the Local Authority with those of any other local agency

which is engaged in a relocation program (see paragraph 5

below), and any other actions deemed necessary by the

Local Authority. As part of the relocation plan the Local

Authority shall include in the Development Program an

estimate of the cost of the services described in this para

graph.

b. If the Local Authority believes it will be necessary

to extend any direct financial assistance to site occupants

(see paragraph 4, below), there shall also be included an

estimate of the number of cases for which such assistance

will be necessary and an estimate of the aggregate cost of

such assistance.

c. The relocation plan shall be prepared in the form

of Item 224 of the Development Program and shall be sub

mitted with the final Development Program.

29

4. Direct Financial Assistance to Site Occupants

a. The Local Authority may furnish direct financial

assistance to site occupants who are to he displaced if after

exhausting all other reasonable means it appears that, in

the determination of the Local Authority, legal eviction

will otherwise be necessary to secure the removal of certain

site occupants and the attendant expense in attorney’s fee

and court costs incident to eviction proceedings, together

with other costs incident to delay in the project while

waiting to secure eviction, will in the aggregate equal or

exceed the aggregate of the proposed financial assistance.

Such financial assistance to any site occupant shall not,

without approval of PHA, exceed a reasonable amount for

moving expenses plus a reasonable amount for the first

month’s rent in appropriate quarters.

b. If, after approval of the Development Program, the

Local Authority finds it necessary to furnish any other type

of financial assistance in specific cases beyond that author

ized by paragraph 4a, above, or to expend for all cases

more than the total sum provided for direct assistance in

the relocation plan, it should address a letter to the PHA

Field Office Director stating the type of assistance to be

given, the approximate number of cases which will re

ceive such assistance, the cost thereof, full justification as

to the necessity (in terms of savings in attorneys fees,

court costs and other costs incident to delay), and, if

required, a revised Development Cost Budget. The PHA

Field Office Director will notify the Local Authority by

letter of approval or disapproval of the request.

c. No expenditures for rehabilitation, improvement, or

decoration of privately owned property can in any event

be approved as a part of the development cost.

Exhibit 1

30

5. Coordination With Other Agencies Engaged

in Relocation

a. If slum clearance under an urban redevelopment

program or any other program, such as a highway project,

is being undertaken by other agencies in the community;

the Local Authority should pay very careful attention to

coordinating its relocation activities with those of such

other agencies. This will help to avoid duplication of

effort in conducting surveys and obtaining vacancy listings,

will result in less hardship to families by avoiding duplicate

referrals to the same dwelling, and will promote better

understanding of and sympathy for the program among the

families being displaced as well as the community at large.

b. The local agencies involved should together consider

this problem and decide that either:

(1) Each agency should do its own relocation work,

depending on close liaison between the personnel

of each agency to achieve the necessary coordina

tion, or

(2) All relocation work should be done by one of the

agencies involved, or

(3) A centralized relocation agency should be created

for this purpose.

If another agency is to do the work for the Local

Authority, the Local Authority should retain sufficient

control to insure coordination with site acquisition and con

struction and compliance with Local Authority relocation

policy. The Local Authority must, in any event, maintain

complete responsibility for determining eligibility and pref

erence rights of families to be admitted to public housing.

c. If the work is to be done for the Local Authority

by another agency, the Local Authority may reimburse

Exhibit 1

31

such agency for reasonable costs attributable to the reloca

tion performed for the Local Authority. A firm maximum

cost should be agreed to in advance to insure that the De

velopment Cost Budget is not exceeded. If the Local

Authority does relocation work for another agency it must

obtain adequate reimbursement to insure that costs of such

relocation are not charged to PHA-aided projects.

6. Record of Families Displaced

a. The Local Authority shall make and preserve a

record of the families displaced by the development of the

project. This information should be obtained at the time

of the survey of site occupants referred to in paragraph 3,

above.

b. This record is established for use in determining

which families, among eligible applicants for admission to

any Federally aided low-rent housing, are entitled to

receive preference in tenant selection as displaced site

occupants. The permanent record of site occupants shall

contain the following information:

(1) Name of the head of the family;

(2) Site address of the family;

(3) Veteran or service status;

(4) Information on s or vice-con ne et e d disability or

death;

(5) Date the family moved from the site.

c. The address of the place to which the family moved

should also be recorded and made a part of the permanent

record when made possible by the site occupant.

d. Site occupants shall be informed that, if they apply

for admission to a Federally aided low-rent project and if

Exhibit 1

32

they are found to be eligible, they will be entitled as site

occupants to receive preferential consideration as units

become available for occupancy. In connection with this,

site occupants should be encouraged to keep the Local

Authority advised of their whereabouts. Specific informa

tion concerning the preference rating of eligible site occu

pants will be covered in another Section.

7. Contract Provisions

a. The Annual Contributions Contract will provide that

the Local Authority (1) shall undertake all steps necessary

to carry out the relocation plan described in the Develop

ment Program, and (2) may pay as part of the development

cost the expense thereof except that no costs of direct

financial assistance to site occupants shall be included in

Development Cost other than those approved by the PHA.

The contract will not obligate the Local Authority to find

new quarters for every family, nor will the contract estab

lish any third-party rights on the part of site occupants.

b. The contract will also require that the Local Author

ity shall make and preserve the record of the families dis

placed, referred to in paragraph 6, above.

Exhibit 1

33

HHFA

PHA

2-21-51 102.1

Exhibit 2

LOW-RENT HOUSING! MANUAL

Racial Policy

The following general statement of racial policy shall

be applicable to all low-rent housing projects developed

and operated under the United States Housing Act of 1937,

as amended:

1. Programs for the development of low-rent housing,

in order to he eligible for PHA assistance, must re

flect equitable provision for eligible families of all

races determined on the approximate volume and

urgency of their respective needs for such housing.

2. While the selection of tenants and the assigning of

dwelling units are primarily matters for local deter

mination, urgency of need and the preferences pre

scribed in the Housing Act of 1949 are the basic

statutory standards for the selection of tenants.

34

HHFA

PHA

3-27-52 208.8

Exhibit 3

LOW-RENT HOUSING MANUAL

Site Selection Policies in Relation to Problems of Minorities

1. Purpose. This Section sets forth PHA policies gov

erning the selection of sites in relation to problems of

minorities.

2. Policies. The following policies should be followed

in the selection of sites for public housing projects:

a. Sites for public housing projects shall be selected in

such manner as to make possible the application of

the policies on racial equity in tenant selection out

lined in Section 102.1, Racial Policy.

b. The number of dwelling units in local program which

are developed for racial minority occupancy shall

not be less than the number of units destroyed which

are in racial minority ocupancy.

c. The selection of sites for public housing should not

result in a material reduction of the land area in the

locality which is available to racial minority families.

d. Every effort should be made to avoid the selection of

sites which will result in the displacement of minority

group populations.

e. Use of congested slum sites which are occupied pre

dominantly by racial minority groups should be made

only where it is possible to comply with the provi

sions of Section 213.2, Relocation of Site Occupants.

35

PHA-1926

Rev. 2-24-50

PRELIMINARY LOAN CONTRACT

This Agreement entered into this 12th day of Septem

ber, 1950, by and between Housing Authority of Savannah

(herein called the “ Loca.l Authority” ) and the Public Hous

ing Administration (herein called “ PHA” ), witnesseth:

In consideration of the mutual covenants hereinafter

set forth, the parties hereto do agree as follows:

1. The Local Authority certifies that it is a body cor

porate and politic, duly created and organized pursuant to

and in accordance with the provisions of The “ Housing

Authorities Law” of the State of Georgia and laws amenda

tory thereof and supplemental thereto, and that it is author

ized to purchase and acquire land, to clear buildings there

from, to develop, construct, maintain and operate low-rent

housing and slum-clearance projects for the purpose of

providing decent, safe and sanitary dwellings for families

of low income, to borrow money for such purposes, and to

issue its bonds or other evidences of indebtedness, and in

connection with the foregoing to take all such other action

as is provided for herein.

2. The Local Authority proposes to develop low-rent

housing projects with financial assistance from the PHA

pursuant to the United States Housing Act of 1937, as

amended (herein called the “ Act” ). In connection there

with, the Local Authority proposes to undertake prelimin

ary surveys and planning necessary for the preparation and

submission of Development Programs for each of such pro

jects serving as the basis for applications to the PHA for

Annual Contributions Contracts.

Exhibit 4

36

3. The PHA has issued to the Local Authority its

Program Reservation No. Ga-2-A for a total of 800 units of

low-rent housing, which Program Reservation is not a legal

obligation or commitment on the part of the PHA, and

which the PHA intends to cancel unless Development Pro

grams satisfactory to the PHA for 500 of such units are

submitted by the Local Authority on or before November

30, 1950, or unless satisfactory Development Program for

300 additional units are submitted on or before November

30, 1951.

4. The Local Authority, pursuant to the provisions of

the Act, has applied to the PHA for a preliminary loan to

meet the cost of preliminary surveys and planning of the

low-rent housing projects to be developed pursuant to such

Program Reservation and located in the City of Savannah,

Georgia. The Council of the Mayor and Aldermen of the

City of Savannah, Georgia (the governing body of the City

of Savannah, Georgia) has by its resolution duly adopted

on the 14 day of July, 1950, approved the application of the

Local Authority for such preliminary loan.

5. The Local Authority has demonstrated to the satis

faction of the PHA that there is a need for the low-rent

housing covered by said Program Reservation which need

is not being met by private enterprise.

6. Subject to the provisions hereinafter set forth, the

PHA hereby agrees to loan to the Local Authority, for use

in preliminary surveys and planning for low-rent housing

projects to be developed pursuant to the aforesaid Pro

gram Reservation a sum not in excess of $210,000. Of such

amount, the sum of $30,000 will be advanced immediately

after the execution of this agreement for use only for eli

gible costs of such preliminary surveys and planning. As a

condition to such immediate advance, the Local Authority

Exhibit 4

37

hereby certifies that, in respect to such proposed projects,

it has complied with the provisions relating to the payment

of prevailing salaries and wages contained in Section 16(2)

of the Act.

7. The PHA shall not he obligated to make any further

advances hereunder in the event of any one of the following

conditions:

(a) if the Local Authority and the Council of the Mayor

and Aldermen of the City of Savannah, Georgia

(the governing body of the City of Savannah,

Georgia) have not, at the time of the request for

such further advances, entered into a Cooperation

Agreement satisfactory to the PHA providing for

the local cooperation required by the PHA pur

suant to the Act; or

(b) if the requisition of the Local Authority therefor

is not accompanied by a signed Certificate of Pur

poses in form and detail satisfactory to the PHA,

showing the use of such funds already expended

and the proposed use of any balance of funds re

maining and. of the additional funds requested, and

demonstrating the need at the time for the addi

tional funds, and by such other documents and data

as may be requested by the PHA; or

(c) if the Local Authority has not furnished a cer

tificate prior to each advance that it has complied

with the provisions relating to the payment of pre

vailing salaries and wages contained in Section

16(2) of the Act; or

(d) if the Local Authority has not complied with all the

provisions in this Contract; or

Exhibit 4

38

(e) if any legal question affecting this Contract, or

affecting the power of the Local Authority to enter

into an Annual Contributions Contract has not

been disposed of to the satisfaction of PHA.

8. Every advance shall be evidenced by a preliminary

loan note in principal amount equal to the amount of such

advance. Principal and interest shall be payable on demand

and shall in any event become due and payable, without

demand, forty years from the date of this Contract. The

note shall be in such form and secured in such manner as

shall be satisfactory to the PHA, and shall bear interest

from the date of the advance at the rate of two and one-

half per centum (2%%) per year.

9. The cost of the aforesaid preliminary surveys and

planning shall be deemed to be a part of the total develop

ment cost of low-rent housing projects which are developed

pursuant to the aforesaid Program Reservation and for

which Annual Contributions Contracts are entered into by

the PHA and the Local Authority. After the date on which

the first advance on any Annual Contributions Contract is

received by the Local Authority, no disbursements shall be

made from the Preliminary Loan Fund in payment for

services rendered or material furnished after such date in

respect to the project or projects covered by such Annual

Contributions Contract. The Local Authority shall apply

to the payment of the principal of and interest on said pre

liminary loan notes the following funds in the following

manner:

(a) Moneys becoming available for the development

of the first project or projects for which a single

Annual Contributions Contract is entered into

shall be applied to the payment of said preliminary

loan notes in amounts equal to (i) the full cost of

Exhibit 4

39

all preliminary housing surveys made by the Local

Authority, and (ii) all costs of planning such first

project or projects which have been paid from the

Preliminary Loan Fund;

(b) Moneys becoming available for the development of

subsequent projects for which Annual Contribu

tions Contracts are entered into shall be applied

to the payment of said preliminary loan notes in

amounts equal to all costs of planning such later

project or projects which have been paid from the

Preliminary Loan Fund;

(c) All moneys remaining in the hands of the Local

Authority out of the funds advanced by the PH A

hereunder at the time when all the projects to be

developed pursuant to the aforesaid Program Res

ervation have been covered by Annual Contribu

tions Contracts shall be immediately paid over to

the PHA in whole or partial payment of the pre

liminary loan notes then held by the PHA; and

(d) Moneys becoming available from any other sources

for the development of any projects for which pre

liminary surveys and plans are made with the aid

of loan funds provided under this Contract shall

be applied to the payment of any unpaid balance

of said preliminary loan notes.

10. The Local Authority shall enter into a Preliminary

Loan Depositary Agreement, which shall be in a form ap

proved by the PHA, and with a bank (which shall be and

continue to be a member of the Federal Deposit Insurance

Corporation.) selected as the depositary by the Local

Authority. The entire proceeds of every advance made pur

suant to this Contract shall be deposited in the Preliminary

Loan Fund at the time such advance is made, unless the

Exhibit 4

40

PHA shall consent in writing to the deposit of such pro

ceeds in some other account. If the PHA finds that one

or more of the following conditions has or have occurred:

(a) the depositary is no longer a member of the Federal

Deposit Insurance Corporation; (b) the depositary has de

faulted in the performance of any of its obligations under

the Preliminary Loan Depositary Agreement; (c) the PHA

for any reason deems the funds deposited by the Local

Authority with the depositary to be unsafe or insecure, then

the PHA may require the Local Authority to withdraw all

its funds immediately from such depositary and to enter

into a Preliminary Loan Depositary Agreement, and to

deposit such funds, with a new depositary (which shall be

a member of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation).

The PHA may exercise its powers under the provisions of

the Preliminary Loan Depositary Agreement to suspend

withdrawals by the Local Authority, and may itself make

withdrawals from the Preliminary Loan Fund, if the Local

Authority shall default in the performance or observance

of any of the agreements on the part of the Local Authority

contained in this Preliminary Loan Contract; but after sus

pending withdrawals by the Local Authority or itself with

drawing such funds, the PHA shall use the funds, as far as

possible, to pay any obligations theretofore validly incurred

by the Local Authority under the provisions of this Con

tract,. In the event that the PHA cancels or reduces the

Program Reservation for any cause without there being

a default by the Local Authority under this Contract, the

PHA may exercise its powers under the provisions of the

Preliminary Loan Depositary Agreement to suspend with

drawals by the Local Authority; and in that event the PHA

at the end of sixty (60) days after sending the notice sus

pending withdrawals (copy of which notice shall at the same

time be sent to the Local Authority), may itself withdraw

the funds then remaining and apply the same to the payment

Exhibit 4

41

of the Preliminary Loan Note. In said notice suspending

withdrawals, the PHA shall authorize the depositary, dur

ing such sixty day period, to continue to honor any check or

order drawn by the Local Authority upon the Preliminary

Loan Fund, if .such check or order shall contain a certificate

executed by a person authorized on behalf of the Local

Authority to sign checks or orders upon such Preliminary

Loan Fund, reading as follows:

“ This is to certify that (1) I am the duly ap

pointed, qualified and acting officer of the Housing

Authority of Savannah authorized to sign the check

[order] to which this certificate relates and to execute

this certificate; (2) the said check [order] is drawn

to pay an obligation validly incurred by the Hous

ing Authority of Savannah under the terms of the

Preliminary Loan Contract dated the 12 day of Sep

tember, 1950 between the Public Housing Adminis

tration and the Housing Authority of Savannah; and

(3) .said obligation was incurred in good faith prior

to the date of the written notice by the Public Hous

ing Administration to the Preliminary Loan De

positary bank suspending, withdrawals by the Hous

ing Authority of Savannah from the Preliminary

Loan Fund.”

11. The Local Authority shall expeditiously and economi

cally complete the preliminary surveys and planning, sub

mit Development Programs, and take such other actions as

are prequisite to the execution of Annual Contributions

Contracts for the projects to be developed pursuant to the

aforesaid Program Reservation. Promptly after receipt

of the initial advance of funds under this Contract, the

Local Authority shall obtain from financially sound insur

ance companies, and thereafter maintain in force, the fol

lowing insurance: (a) fidelity bonds covering all persons

Exhibit 4

42

who will handle or disburse any of the funds made available

under this Contract; (b) workmen’s compensation; (c)

automobile insurance (including comprehensive fire and

theft, liability for bodily injury and property damage);

(d) public liability; and (e) fire and extended coverage in

surance on furniture and fixtures. The Local Authority

shall promptly furnish the PHA with certified copies of

such policies and bonds.

12. The Local Authority will not undertake preliminary

housing surveys covering housing and economic conditions

except after mutual agreement between the Local Authority

and the PHA as to the type, extent, methods, and proposed

costs of such surveys.

13. The Local Authority shall by contract, in a form

prescribed or approved by the PHA, provide qualified archi

tectural and engineering services necessary for each low-

rent housing project to be developed pursuant to the afore

said Program Reservation, including preparation of ma

terials necessary for Development Programs. Such con

tracts shall further provide that, in the event of the execu

tion of an Annual Contributions Contract covering any

such project, the architects and engineers shall furnish

the architectural and engineering services necessary for

the completion of the project. Such contracts shall fur

ther provide that the Local Authority may at any time

abandon the construction of the project or any substantial

part thereof, or may, for cause, abandon all or any sub

stantial part of the architect’s services, and that in either

such event, the contract shall be modified or terminated,

and payment for the services of the architect theretofore

rendered shall be made in a manner to be set forth in such

contract. The PHA shall furnish schedules of reasonable

maximum fees, which fees shall not be exceeded without

PHA concurrence. Architects shall be required by the

Exhibit 4

43

Local Authority to be responsible for compliance of plans

and specifications with applicable local laws and regula

tions.

14. The Local Authority shall by contract, in a form

prescribed or approved by the PHA, provide qualified

services for obtaining land surveys, title information, and

appraisals necessary for each low-rent housing project

to be developed pursuant to the aforesaid Program Reser

vation. Specific parcel-by-parcel appraisals shall not be

made prior to the tentative approval by the PITA of a

project site and the General Scheme of the project. All

appraisals shall be held strictly confidential, and in no case

shall persons who have made such appraisals be employed

to negotiate options. The Local Authority may by con

tract, in a form prescribed or approved by the PHA, pro

vide qualified services for the negotiation of options before

execution of an Annual Contributions Contract. No part

of any funds made available to the Local Authority under

this Preliminary Loan Contract shall be used either to

acquire land or to make any payments (other than nominal

payments of one dollar per option) as consideration for

options, nor shall irrevocable commitments to acquire land

be made before the execution of an Annual Contributions

Contract.

15. No part of any funds made available to the Local

Authority under this Preliminary Loan Contract shall be

used for any purposes except for making preliminary sur

veys and planning for low-rent housing projects to be

developed pursuant to the aforesaid Program Reservation.

No part of such funds shall be used to make payments for

any materials or services purchased or contracted for by

the Local Authority prior to the date of the Preliminary

Loan Contract without the prior approval of the PHA as

to the eligibility and amount of such payments. No part

Exhibit 4

44

of any funds made available under this Preliminary Loan

Contract subsequent to the initial advance shall be used

for the payment of any items not covered by a Certificate

of Purposes as provided in Section 7 (b) hereof.

16. The preliminary surveys and planning carried out

by the Local Authority pursuant to this Preliminary Loan

Contract shall be limited to low-rent housing projects, (a)

which will comply with the cost limitations of Section 15(5)

of the Act, (b) in connection with which the equivalent

elimination provisions of Section 10(a) of the Act will be

complied with, and (c) which will comply with all other

applicable provisions of the Act.

17. The Local Authority, in connection with any low-

rent housing project to be developed pursuant to the afore

said Program Reservation, agrees as follows:

(a) The Local Authority will itself pay, and in all

contracts entered into by it shall require that there

shall be paid, to all architects, technical engineers,

draftsmen, and technicians employed in prelimi

nary surveys and planning or in the development

of such projects, and to all maintenance laborers

and mechanics employed in the administration of

such projects, not less than the salaries or wages

prevailing in the locality of such project, as such

prevailing salaries or wages are determined or

adopted (subsequent to determination under ap

plicable State or local law) by the P H A ;

(b) The Local Authority will itself pay, and in all

contracts entered into by it shall require that

there shall be paid, to all laborers and mechanics

employed in preliminary surveys and planning or

in the development of such projects, not less than

the wages prevailing in the locality of such project,

Exhibit 4

45

as predetermined either (i) by the Secretary of

Labor pursuant to the Davis-Baeon Act (49 Stat.

1011), or (ii) under applicable State laws, which

ever wages are the higher;

(c) The Local Authority will require that architects,

technical engineers, draftsmen, technicians, labor

ers and mechanics, employed in the preliminary

surveys and planning and in the development of

such projects shall not be permitted to work