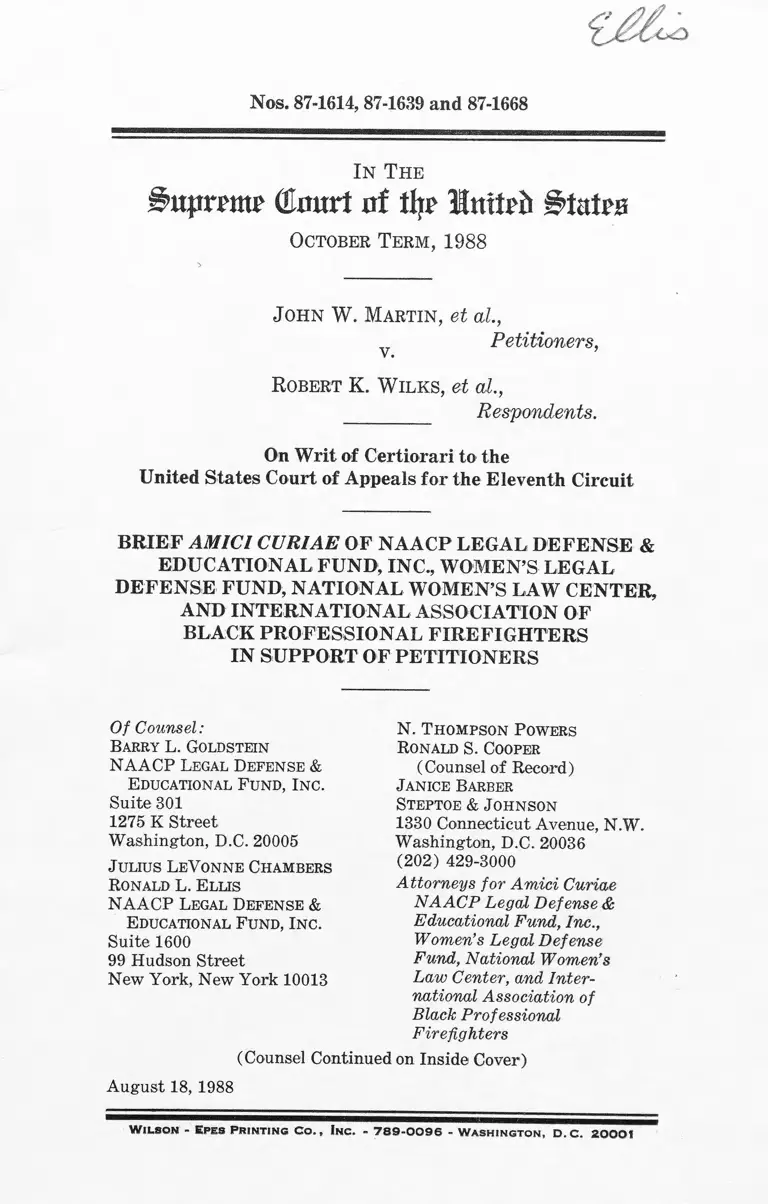

Martin v Wilks Brief Amicus Curiae in Support of Petitioners

Public Court Documents

August 18, 1988

32 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Martin v Wilks Brief Amicus Curiae in Support of Petitioners, 1988. d2826c1a-bd9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/7bf92e24-3f10-446c-8c39-af213013cd72/martin-v-wilks-brief-amicus-curiae-in-support-of-petitioners. Accessed February 17, 2026.

Copied!

Nos. 87-1614, 87-1639 and 87-1668

In T he

dmtri nf tty llnitTfr l^tate

October T erm , 1988

J ohn W . Martin , et al.,

Petitioners,

R obert K. W ilk s , et al.,

_________ Respondents.

On Writ of Certiorari to the

United States Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit

BRIEF AMICI CURIAE OF NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE &

EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC., WOMEN’S LEGAL

DEFENSE FUND, NATIONAL WOMEN’S LAW CENTER,

AND INTERNATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF

BLACK PROFESSIONAL FIREFIGHTERS

IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONERS

Of Counsel:

Barry L. Goldstein

NAACP Legal Defense &

Educational Fund, Inc .

Suite 301

1275 K Street

Washington, D.C. 20005

Julius LeVonne Chambers

Ronald L. Ellis

NAACP Legal Defense &

Educational Fund, Inc.

Suite 1600

99 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10013

N. T hompson Powers

Ronald S. Cooper

(Counsel of Record)

Janice Barber

Steptoe & Johnson

1330 Connecticut Avenue, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20036

(202) 429-3000

Attorneys for Amici Curiae

NAACP Legal Defense &

Educational Fund, Inc.,

Women’s Legal Defense

Fund, National Women’s

Law Center, and Inter

national Association of

Black Professional

Firefighters

(Counsel Continued on Inside Cover)

August 18, 1988

W ilson - Epes Printing Co . , In c . - 7 8 9 -0 0 9 6 - W a s h in g t o n , D .C . 2 0 0 0 1

Of Counsel:

Claudia W ithers

W omen ’s Legal Defense Fund

2000 P Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20036

Marcia D. Greenberger

Brenda Smith

National W omen ’s Law Center

Suite 100

1616 P Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20036

W illiam C. McNeill, III

Eva Jefferson Paterson

301 Mission Street

Suite 400

San Francisco, California 94105

Attorneys for International

Association of Black

Professional Firefighters

TABLE OF CONTENTS

INTEREST OF THE AMICI CURIAE___ ________ __ 1

STATEMENT ............ — ......................................... ............ 6

ARGUMENT_________ ___ ___________ __ ______ _______ 10

I. THE DECISION BELOW WILL FRUSTRATE

THE GOALS OF TITLE VII AND IMPAIR

EFFICIENT OPERATION OF THE JUDI

CIAL SYSTEM ................................................ ........ 11

A. The Decision Below Undermines Incentives

to Settle Title VII Litigation...... ......... .......... . 14

B. The Decision Below Would Produce Repeti

tive, Duplicative Litigation ____________ __ _ 15

II. REQUIRING INTERVENTION IS THE ONLY

PRACTICAL MEANS TO ACCOMMODATE

THE INTERESTS OF THIRD PARTIES

WHILE PRESERVING THE VIABILITY OF

THE CONSENT DECREE PROCESS............... 19

Page

TABLE OF AU TH ORITIES-________________________ ii

CONCLUSION 28

11

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

CASES: Page

Alexander v. Bahou, 86 F.R.D. 194 (N.D.N.Y.

1980) ____________ 13

Alexander v. Gardner-Denver Co., 415 U.S. 36

(1974) ________ 12

Bergh v. Washington, 535 F.2d 505 (9th Cir.),

cert, denied, 429 U.S. 921 (1976) ........................ 17

Brown v. Felsen, 442 U.S. 127 (1979)..................... 19

Culbreath v. Dukakis, 630 F.2d 15 (1st Cir. 1980).. 9

Dennison v. Los Angeles Department of Water &

Poiver, 658 F.2d 694 (9th Cir. 1981).................... 9, 17

Detroit Police Officers Association v. Young, 824

F.2d 512 (6th Cir. 1987)_____________ ____ ___ _ 19

Eggleston v. Chicago Journeymen Plumbers, 657

F.2d 890 (7th Cir. 1981), cert, denied, 455 U.S.

1017 (1982) ______ _________ __ ________________ 20

English v. Seaboard Coast Line Railroad, 465 F.2d

43 (5th Cir. 1972)_______ __________________ _ 16

Ford Motor Co. v. EEOC, 458 U.S. 219 (1982).... 12

Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co., 424 U.S.

747 (1976 )_________________________ _______ _ 11

Goins v. Bethlehem Steel Corp., 657 F.2d 62 (4th

Cir. 1981), cert, denied, 455 U.S. 940 (1982).... 9, 17

Grubb v. Public Utility Commission, 281 U.S. 470

(1930) _______ ____ _____ __ _______ ____________ 19

Hansberry v. Lee, 311 U.S. 32 (1940) _______ ___ 22

Henson v. East Lincoln Township, 814 F.2d 410

(7th Cir. 1987), cert, granted, 108 S. Ct. 691

(1988) _____________ __ _________ _____ ________ 21

International Brotherhood of Teamsters v. United

States, 431 U.S. 324 (1977) ................... ............... 11, 12

Johnson v. Transportation Agency, Santa Clara

County, 107 S. Ct. 1442 (1987)............................. 14

Kelly v. Kosuga, 358 U.S. 516 (1959)....... ........ 13

Kirkland v. New York State Department of Cor

rectional Services, 520 F.2d 420 (2d Cir. 1975),

cert, denied, 429 U.S. 823 (1976)............... .......... 16

I l l

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES— Continued

Page

Kline v. Coldwell, Banker & Co., 508 F.2d 226

(9th Cir. 1974), cert, denied, 421 U.S. 963

(1975) ...... ................ ............... ....... ........................... 22

Kremer v. Chemical Construction Corp., 456 U.S.

461 (1982) .... ..................... ......... ......... ......... .......... 19

LaMar v. H&B Novelty & Loan Co., 489 F.2d 461

(9th Cir. 1978).......................................... ........... . 22

Local 28, Sheet Metal Workers v. EEOC, 478 U.S.

421 (1986) _______ ____________________________ 7

Local 93, Firefighters v. City of Cleveland, 106

S. Ct. 3063 (1986) ................... .................. ........ 11

Marcera v. Chinlund, 595 F.2d 1231, 1238 (2d

Cir.), vacated on other grounds sub. nom.

Lombard v. Marcera, 442 U.S. 915 (1979)........ 21

Marino v. Ortiz, 806 F.2d 1144 (2d Cir. 1986),

aff’d, 108 S. Ct. 586 (1988 )__ _________________ 9

Mudd v. Basse, 68 F.R.D. 522 (N.D. Ind. 1975),

aff’d mem., 582 F.2d 1283 (7th Cir. 1978), cert.

denied, 439 U.S. 1078 (1979) __________________ 22

Nevada v. United States, 463 U.S. 110 (1983).... 18

New York State Association for Retarded Chil

dren v. Carey, 438 F. Supp. 440 (E.D.N.Y.

1977) _____ _______ _______ ____ ______ ______ _____ 23

O’Burn v. Shapp, 70 F.R.D. 549 (E.D. Pa.), aff’d

mem., 546 F.2d 417 (3d Cir. 1976), cert, denied,

430 U.S. 968 (1977) ___________________________ 17

Paxman v. Campbell, 612 F.2d 848 (4th Cir.

1980) (en banc), cert, denied, 449 U.S. 1129

(1981) ........ ........ ............................. ........... ........... . 21

Romain v. Kuret, 772 F.2d 281 (6th Cir. 1985).... 20

Spangler v. Pasadena City Board of Education,

611 F.2d 1239 (9th Cir. 1979)...... ....................... 13

Stotts v. Memphis Fire Department, 679 F.2d 541

(6th Cir. 1982), rev’d on other grounds sub nom.

Firefighters Local Union No. 17 8 U v. Stotts,

467 U.S. 561 (1984) _______ ______ ____________ 17

Striff v. Mason, 849 F.2d 240 (6th Cir. 1988).... 9

IV

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES— Continued

Page

Thaggard v. City of Jackson, 687 F.2d 66 (5th

Cir. 1982), cert, denied, 464 U.S. 900 (1983).... 9,17

Thompson v. Board of Education, 709 F.2d 1200

(6th Cir. 1983) ........................ ............................... 21

United States v. Allegheny-Ludlum Industries,

517 F.2d 826 (5th Cir. 1975), cert, denied, 425

U.S. 944 (1976) ............. ........................................ 12

United States v. City of Miami, 664 F.2d 435 (5th

Cir. 1981) (en b a n c)............... ..... ................ ......... . 13

United States v. City of Philadelphia, 499 F.

Supp. 1196 (E.D. Pa. 1980) ...... ............................ 13

United States v. Paradise, 480 U.S. 149 (1987).... 7

United Steelworkers v. Weber, 443 U.S. 193

(1979) .................. .......... ............................. .......... 11, 14, 17

Way v. Mueller Brass Co., 840 F.2d 303 (5th Cir.

1988)....... ............. ...... .......................... ........ .............. 20

Weiner v. Bank of King of Prussia, 358 F. Supp.

684 (E.D. Pa. 1973).......................................... ...... 22

Williams v. City of New Orleans, 543 F. Supp. 662

(E.D. La. ) ,r e v ’d, 694 F.2d 987 (5th Cir. 1982).. 13

Williams v. City of New Orleans, 694 F.2d 987 (5th

Cir. 1982)................................................................... . 13

W.R. Grace & Co. v. Local 759, International

Union of the United Rubber, Cork, Linoleum &

Plastic Workers of America, 461 U.S. 757

(1983) _____ ______ ______ __ ______________ ___ _ 11

MISCELLANEOUS:

1987 Annual Report o f the Director of the Ad

ministrative Office of the United States Courts.. 12

Note, Certification of Defendant Classes Under

Ride 2 3 (b )(2 ), 1984 Colum. L. Rev. 1371........... 21,22

Schwarzschild, Public Law by Private Bargain:

Title VII Consent Decrees and the Fairness of

Negotiated Institutional Reform, 1984 Duke L.

Rev. 887 12

V

Page

Williams, Some Defendants Have Class: Reflec

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES— Continued

tions on the GAP Securities Litigation, 89 F.R.D.

287 (1981) ______ _____________ ______ __________ 22

18 C. Wright, A. Miller, & E. Cooper, Federal

Practice & Procedure, § 4451 (1981) .................. 18

7A C. Wright, A. Miller & M. Kane, Federal Prac

tice & Procedure, § 1770 (1986) ....... ......... ....... 22

Wolfson, Defendant Class Actions, 88 Ohio St.

L.J. 459 (1977 )...................... .................................. 22

In The

dkmxt nt tl}i> luitrxi g»tate

October Term, 1988

Nos. 87-1614, 87-1639 and 87-1668

John W. Martin, et al,

Petitioners,

v.

Robert K. W ilks, et al.,

Respondents.

On Writ of Certiorari to the

United States Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit

BRIEF AMICI CURIAE OF NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE &

EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC., WOMEN’S LEGAL

DEFENSE FUND, NATIONAL WOMEN’S LAW CENTER,

AND INTERNATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF

BLACK PROFESSIONAL FIREFIGHTERS

IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONERS

This brief in support of petitioners is submitted with

the written consent of counsel to all parties filed with the

Clerk of the Court.

INTEREST OF THE AMICI CURIAE

The NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund,

Inc., ( “ LDF” ) is a non-profit corporation whose prin

2

cipal purpose is to secure the civil and constitutional

rights of black persons through litigation and education.

For more than forty years, its attorneys have repre

sented parties in thousands of civil rights cases, includ

ing many significant employment discrimination cases.

See, e.g., Bazemore v. Friday, 478 U.S. 385 (1986) ;

Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405 (1975);

Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424 (1971).

The issue presented here is particularly important to

the LDF’s litigation efforts. First, the LDF has litigated

many complex class action employment cases, and, with

few exceptions, has entered into consent decrees that

have contained the final remedies for the plaintiff class.

For example, after trial and review by the court of ap

peals and this Court, the LDF entered into consent de

crees that resolved both the Griggs and Albemarle Paper

cases. If consent decrees in fair employment cases may

routinely be challenged by collateral attack as the court

below permitted in this case, the LDF will be unable to

rely on the use of such decrees to secure fair employment

remedies.

Second, the decision below threatens severely to under

cut the ability of the LDF and other civil rights groups

to bring fair employment actions. The LDF litigates

claims on minority employees’ behalf on a pro bono basis,

and resources available to fund that litigation are lim

ited. Settlement of cases is therefore an essential means

of maximizing the LDF’s effectiveness, allowing it to

provide services to more employees and other civil ̂ rights

plaintiffs. If the LDF is forced to litigate every case to

conclusion or to face the repeated challenges to consent

decrees that the decision below promises, its effectiveness

clearly will be diluted. Without the incentives to settle

ment that are jeopardized by the decision below, many of

the important fair employment gains of the last two

decades could not have been achieved.

3

Third, the LDF has repeatedly represented plaintiffs

challenging civil rights violations in the City of Birming

ham. That litigation has vindicated the right to demon

strate against racial discrimination,1 the right to inte

grated transportation,2 * the right to equal educational op

portunity,8 the right to non-diseriminatory zoning,4 the

right to fair employment,5 6 and the right to a nondis-

criminatory statute governing the personnel system.11'

Having spent four decades challenging discriminatory

practices in Birmingham, it is important for the LDF to

support the effective action taken by Birmingham to rem

edy the continuing effects of an unfortunate history of

racial discrimination.

* * * *

The Women’s Legal Defense Fund ( “ WLDF” ) is a

non-profit, tax-exempt membership organization, founded

in 1971 to provide pro bono legal assistance to individuals

who have been discriminated against on the basis of sex.

WLDF devotes a major portion of its resources to

combatting sex discrimination in employment through

pro bono litigation of significant employment discrimina

tion cases, operation of an employment discrimination

counseling program, public education, and advocacy be

fore the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission and

1 Shuttle-worth v. City of Birmingham, 394 U.S. 147 (1969);

Walker v. Birmingham, 388 U.S. 307 (1967).

2 Bowman v. Birmingham Transit Co., 280 F.2d 531 (5th Cir.

1960).

8 Armstrong v. Board of Education, 333 F.2d 47 (5th Cir. 1964).

4 City of Birmingham v. Monk, 185 F.2d 859 (5th Cir. 1950),

cert, denied, 341 U.S. 940 (1951).

5 James v. Stockham Valves & Fittings, Inc., 559 F.2d 310 (5th

Cir. 1977), cert, denied, 434 U.S. 1034 (1978); Pettway v. America?i

Cast Iron Pipe Co., 494 F.2d 211 (5th Cir. 1974).

6 Woods v. Florence, No. CY 82-PT-2272-S (N.D. Ala. Jan. 31,

1988).

4

other federal and local agencies that are charged with

enforcement of equal opportunity laws.

WLDF has represented numerous plaintiffs in employ

ment discrimination actions brought pursuant to Title

VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, and thus recognizes

the importance of resolving such cases without resort to

extended litigation. For example, in 1987 WLDF resolved

LaPlace v. Ridgeivells Caterers, a case in which it pro

vided pro bono representation to more than 500 wait

resses who alleged occupational segregation and sex-based

wage discrimination. As a result of the settlement ob

tained in that case, men and women will be assigned to

jobs and paid without regard to sex, and a class of wait

resses will be provided back-pay.

Consent decrees have been relied on as an effective

means of resolving complex litigation in ways that benefit

employers and employees. A decision by this Court in

creasing the vulnerability of consent decrees would under

mine the enforcement of Title VII and negate the em

ployment gains achieved by women and people of color

in this country.

* * * *

The National Women’s Law Center ( “ NWLC” ) is a

non-profit legal advocacy organization dedicated to the

advancement and protection of women’s rights and the

corresponding elimination of sex discrimination from all

facets of American life. Since 1972, the Center has

worked to secure equal opportunity in the workplace

through the full enforcement of Title VII of the Civil

Rights Act of 1964, as amended, and other civil rights

statutes, and through the implementation of effective

remedies for long-standing discrimination against women

and minorities.7

7 NWLC has participated as an amicus curiae in Title VII cases

before the Supreme Court, including Johnson v. Transportation

Agency, Santa Clara County California, 107 S. Ct. 1442 (1987);

5

Consent decrees have proven to be one of the most ef

fective remedies for the eradication of discrimination

against women and minorities. The issue presented in

this case, the ability of third parties to attack consent

decrees collaterally, is therefore of critical importance to

the National Women’s Law Center and other civil rights

organizations who view consent decrees as an effective

and indeed desired method of resolving complex cases in

volving violations of civil rights. NWLC is currently rep

resenting parties to several consent decrees resolving long

standing discrimination claims, and has seen firsthand

the major advances in the elimination of discrimination

resulting from these decrees.® Absent the entry of consent

decrees in these cases it is certain that both sides would

have expended a great deal more time and resources,

thereby diluting their overall litigation and enforcement

efforts in these areas. It is also certain that the rights

and responsibilities of the parties would have been re

solved much less expeditiously. A ruling by this Court,

like that entered by the court below, allowing collateral

attacks on consent decrees would diminish the efficacy of

consent decrees as a method of promoting the resolution 8

Hishon v. King & Spaulding, 467 U.S. 69 (1984); Hopkins v. Price

Waterhouse, 825 F.2d 458 (D.C. 1987), cert, granted, 108 S. Ct, 1106

(1988).

8 See Haffer v. Temple University, No. 80-1362 (E.D. Pa. June 13,

1988) (order tentatively approving proposed settlement in class

action sex-discrimination challenge of intercollegiate athletic pro

gram) ; Adams v. Califano, No. 3095-70, WEAL v. Califano, No. 74-

1720 (D.D.C. Dec. 29, 1977) (consent decree resolving Department

of Labor and Department of Education’s obligations for enforce

ment of Title IX and Executive Order 11246), dismissed sub nom.

Adams v. Bennett, 675 F. Supp. 668 (D.D.C. 1987), appeal docketed,

WEAL v. Bennett, No. 88-5065 (D.C. Cir. Mar. 3, 1988); Advocates

for Women v. Marshall, No. 76-0862, Women Working in Construc

tion v. Marshall, No. 76-527 (D.D.C. Dec. 5, 1978) (consent decree

requiring federal construction contractors to take specific affirma

tive action steps for women, including goals and timetables).

6

of complex cases and would discourage organizations and

individuals represented by NWLC from entering into

consent decrees.

The ruling below significantly impedes the ability of

NWLC and other public interest groups to litigate fair

employment actions. Our work is done on a pro bono

basis. The extent to which we are able to bring cases is

directly related to our ability to resolve others. Settle

ment of these cases through consent decrees is, therefore,

essential to our efforts to assist other women in securing

and enforcing their rights'.

* * -X- *

The International Association of Black Professional

Firefighters was founded in Hartford, Connecticut, in

October 1970. The Association promotes interracial prog

ress throughout fire departments in the United States

by advocating the promotion and hiring of black fire

fighters. Many of the local chapters of the Association

are actively involved in the enforcement of consent de

crees aimed at full desegregation of the fire service. Ac

cordingly, the continued viability of consent decrees for

resolution of fair employment disputes is of significant

concern to the Association.

STATEMENT

Amici adopt the statement of facts set forth in the

brief of Petitioners Martin, et al. Amici limit their fac

tual statement to the uncontested facts that are partic

ularly significant to their position in this brief.

The employment practices of the City of Birmingham

were the subject of contentious litigation for more than

eight years prior to the filing of the first of these actions

in 1982. The federal government, the NAACP, and

classes of minority applicants and employees alleged dis

crimination in virtually every branch of city employment

and demanded a reversal of the city’s long and infamous

7

history of racial discrimination.9 10 Their claims— and the

two resulting trials— were the subject of prominent and

continuous press coverage that made the case notorious in

the community.19

Respondents do not dispute that they had actual knowl

edge of the litigation from its early stages in 1974. In

deed, the Eleventh Circuit determined that respondents

“knew at an early stage in the proceedings that their

rights could be adversely affected” if petitioners pre

vailed. United States v. Jefferson County, 720 F.2d 1511,

1516 (11th Cir. 1983). Members of the Birmingham

Firefighters Association (“BFA” ) continually monitored

the case and consulted with the Personnel Board regard

ing the litigation’s impact on the interests of non

minority employees. Joint Appendix (“J.A.” ) 772-73.

Those contacts with parties to the case were maintained

throughout the course of the litigation. Id. at 773.

In May 1981, the parties negotiated consent decrees

designed to resolve all outstanding claims of discrimina

tion on the basis of race or sex. As an element of those

decrees, the parties established a process for providing

notice to all interested persons. Appendix to the Petitions

9 That history is recounted in the brief of petitioners Martin,

et al. Amici submit that the facts of this case are no less extreme

than those that this Court found to warrant extraordinary court-

ordered relief in Local 28, Sheet Metal Workers v. EEOC, 478 U.S.

421 (1986), and United States v. Paradise, 480 U.S. 149 (1987).

10 See, e.g., Birmingham News, Jan. 4, 1974, at 1; id. May 27, 1975,

at 1; id. Dec. 20, 1976, at 14; id. Dec. 21, 1976, at 43; id. Jan. 10,

1977, at 1; Birmingham Post-Herald, May 9, 1980, at 1. The first

trial, held in 1976, involved the legality of exams given applicants

for the police and fire departments. It resulted in a judgment for

plaintiffs that was affirmed by the Fifth Circuit. Ensley Branch of

the NAACP v. Seibels, 14 Fair Empl. Prac. Cases (BNA) 670 (N.D.

Ala. 1977), aff’d, 616 F.2d 812 (5th Cir.), cert, denied, 449 U.S. 1061

(1980). The 1979 trial, involving other hiring and promotional

practices, did not produce a judgment prior to entry of the consent

decrees.

8

for Certiorari (“ Pet. App.” ) 146a-47a; J.A. 697. That

process provided nearly two months’ notice of the sched

uled fairness hearing and advised interested parties of

their right to object to the decrees. Pet. App. 146a-47a.

Notices were published in two local newspapers and also

served by mail on class members. Id. at 146a.

Following this notice process, the district court held

a fairness hearing at which it received oral and written

testimony and considered the objections of a number of

persons to the terms or legality of the consent decrees.

J.A. 727. Several non-minority employees, as well as

representatives of the BFA, appeared at the fairness

hearing to present their objections. Pet. App. 238a-39a.

They asserted that the court could not approve a settle

ment providing “ for affirmative relief for blacks and

females which [would] adversely discriminate against

whites and males without a judicial finding of actual dis

crimination.” J.A. 704.11

The district court gave all objectors a full opportunity

to present their claims and to submit relevant evidence.

Id. at 727-28, 770. It then considered and rejected those

objections in a careful and thorough opinion. Pet. App.

236a.

A scant eight months later respondents filed the first

of these reverse discrimination actions in reaction to the

very first fire department promotion made pursuant to

the consent decree. The complaint in that case, Bennett

v. Arrington, alleged that the city and the personnel

board, acting pursuant to the consent decrees, were im

permissibly certifying candidates and making promo

tions on the basis of race. Id. at 113a. It alleged that

11 According to the objectors, such discrimination would consti

tute a violation of Title VII, 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-2(j). J.A. 705, 711-

12. The objectors further argued that the provisions of the decrees

specifying goals based on race and sex “constitute state actions

which deny equal protection of law,” and that for that reason the

court should withhold its approval. J.A. 780.

9

race- or sex-conscious decisions were illegal and the con

sent decree was “ void on its face.” Id. at 113a-115a.12 *

Respondents subsequently filed two additional complaints,

both challenging actions taken by the city in compliance

with the consent decree. J.A. 93, 130. Those com

plaints essentially constituted a restatement of objections

considered at the fairness hearing, and the district court

held that respondents were precluded from challenging

the validity of the consent decree. Pet, App. 106a.18

The United States Court of Appeals for the Eleventh

Circuit reversed in a sharp departure from the position

uniformly adopted by other courts of appeals,14 The

court below authorized collateral attacks on the consent

decrees, adopting a broad rule that is completely unjusti

fied by the facts of this case. Indeed, the sweeping effect

of the Eleventh Circuit’s holding is underscored because

respondents had actual notice of the pendency of the pro

12 The Bennett plaintiffs further alleged that the race- and sex

conscious provisions of the decree conflicted with various state and

local authorities, including Title VII and 42 U.S.C. § 1981, as well as

the fifth and fourteenth amendments. Pet. App. 113a.

is while declining to permit respondents to relitigate the validity

of the consent decree, Judge Pointer nevertheless expressly reaf

firmed his earlier ruling that the decree “ is a proper remedial device,

designed to overcome the effects of prior, illegal discrimination by

the City of Birmingham.” Pet. App. at 106a. Having thus addressed

the issue of the decree’s validity, the court then ruled on the merits

of respondents’ reverse discrimination claims, rejecting them for

failure to prove discriminatory intent. Id. at 107a. As petitioners

Martin, et al., demonstrate in their brief, that decision fully and

correctly disposed of the merits of respondents’ claims.

14 See, e.g., Striff v. Mason, 849 F.2d 240 (6th Cir. 1988); Marino

v. Ortiz, 806 F.2d 1144 (2d Cir. 1986), aff’d, 108 S. Ct. 586 (1988) ;

Thaggard v. City of Jackson, 687 F.2d 66 (5th Cir. 1982), cert,

denied sub nom. Ashley v. City of Jackson, 464 U.S. 900 (1983);

Dennison v. Los Angeles Department of Water & Power, 658 F.2d

694 (9th Cir. 1981) ; Goins v. Bethlehem Steel Corp., 657 F.2d 62

(4th Cir. 1981), cert, denied, 455 U.S. 940 (1982) ; see also Culbreath

v. Dukakis, 630 F.2d 15 (1st Cir. 1980).

10

ceeding, had opportunities to participate in it, and had

their views represented at the fairness hearing by in

dividuals pressing legal contentions virtually identical to

those raised in respondents’ subsequent suits.15

ARGUMENT

Since the enactment of Title VII in 1964, consent de

crees have played a central role in the resolution of fair

employment disputes. To the benefit of both litigants

and the federal courts, consent decrees have provided a

vehicle for terminating disputes without extended litiga

tion, enabling the parties to develop productive working

relationships under cooperatively designed guidelines.

The decision below authorizes collateral attacks on con

sent decrees by persons who knew of the proceedings,

who had a timely opportunity to intervene, whose inter

ests were protected by a fairness hearing, and whose

position was considered by the decree court. If collateral

attacks were permitted in such circumstances, consent

decrees would no longer be the end to Title VII litiga

tion, but the beginning of a protracted process in which

the parties could be compelled to litigate every employ

ment action taken under the decree. That result would

nullify the multiple benefits of consent decrees and

thrust onerous burdens upon the courts because parties

would reject decrees as an alternative to continued liti

gation.

The adverse impact of the Eleventh Circuit’s rule

would not be limited to the Weber-type relief approved in

15 In addition to the opportunity to present their views at the

fairness hearing, respondents undoubtedly could have sought timely

intervention as parties, Instead, they waited until after the fairness

hearing to make such a request. J.A. 774. The Eleventh Circuit

affirmed Judge Pointer’s rejection of this eleventh-hour request as

untimely. Jefferson County, 720 F.2d at 1516.

11

this case.16 It would extend to cases involving Franks-

type relief providing constructive seniority17 18 and to more

comprehensive modification of an entire seniority system

under the standards set forth in Teamsters™ both of

which would necessarily affect non-party employees. Un

der the Eleventh Circuit’s rationale, non-minority em

ployees who judged themselves to be adversely affected

by any of these established Title VII remedies could

bring collateral actions challenging the decree.

The facts of this case neither justify nor compel these

adverse results. Rule 24 of the Federal Rules o f Civil

Procedure provides a fair and adequate means for non-

parties to protect their interests in ongoing litigation

without compromising the interests of the parties or un

duly burdening the court. When non-parties know of the

ongoing litigation and of the potential adverse effect of a

proposed consent decree, it is reasonable to assign them

the burden of intervening or appearing at the fairness

hearing and presenting all their challenges to the decree.

Both fundamental principles of finality and important

policies of fair employment litigation require that in

these circumstances collateral attacks on the consent de

cree be barred.

I. THE DECISION BELOW WILL FRUSTRATE THE

GOALS OF TITLE VII AND IMPAIR EFFICIENT

OPERATION OF THE JUDICIAL SYSTEM

This Court has consistently emphasized that voluntary

settlement of employment discrimination claims is a pri

mary objective of Title VII. Local 93, Firefighters v.

City of Cleveland, 106 S. C't. 3063, 3076 (1986); W.R.

16 See United Steelworkers v. Weber, 443 U.S. 193 (1979).

17 See Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co., 424 U.S. 747 (1976).

18 See International Brotherhood of Teamsters v. United States,

431 U.S. 324 (1977).

12

Grace & Co. v. Local 759, International Union of the

United Rubber, Cork, Linoleum & Plastic Workers of

America, 461 U.S. 757, 770-71 (1983); Ford Motor Co.

v. EEOC, 458 U.S. 219, 228 (1982) ; Alexander v. Gard-

ner-Denver Co., 415 U.S. 36, 44 (1974). Congress

strongly encouraged employers “ to self-examine and self-

evaluate their employment practices” and voluntarily to

cease practices that perpetuate discrimination. Interna

tional Brotherhood of Teamsters, 431 U.S. at 364 (quot

ing Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405, 417-18

(1975)).

Consent decrees are an important vehicle for achieving

these statutory goals. Today, an employment discrimina

tion action brought against a state or local government

or a large private employer is far more likely to be re

solved by consent decree than litigated to judgment.10 * * * * * * * *

Because of the high volume of Title VII litigation,120 a

negotiated resolution serves the interests of the courts

and the public, as well as the parties. Consent decrees

remove complex, multiple party cases from the courts’

trial dockets, freeing judicial resources that would other

wise be consumed by difficult procedural and legal is

sues.'21

The incentives to settlement of large-scale Title VII

actions are considerable. Parties are relieved of the high

costs, risks, and unavoidable delays of litigating such

cases to conclusion. They can cooperate in restructuring

10 See Schwarzschild, Public Law by Private Bargain: Title VII

Consent Decrees and the Fairness of Negotiated Institutional Re

form, 1984 Duke L. Rev. 887, 894 ( “ Title VII Consent Decrees” ).

2d In 1987, for example, the number of private plaintiff fair em

ployment cases pending- in the federal courts exceeded 10,000 cases.

1987 Annual Report of the Director of the Administrative Office

of the United States Courts at 116.

21 See, e.g., United States v. Allegheny-Ludlum Industries, 517

F.2d 826, 851 n.28 (5th Cir. 1975), cert, denied, 425 U.S. 944 (1976).

13

their employment relationship by choosing detailed, feas

ible solutions that are closely tailored to their specific

businesses and communities. When remedies are chosen

by the parties— rather than imposed by the court on the

losing party— normal working relationships can be re

sumed more quickly.132

Most important, both parties to the decree are ensured

of a final disposition of their dispute, approved and en

forced by the federal courts.® The parties obtain the

court’s judgment that their agreement “ ‘represents a

reasonable factual and legal determination based on the

facts of record. . . . If the decree also affects third par

ties, the court must be satisfied that the effect on them

is neither unreasonable nor proscribed.’ ” Williams v.

City of New Orleans, 694 F.2d 987, 991 (5th Cir. 1982)

(emphasis deleted) (quoting United States v. City of

Miami, 664 F.2d 435, 441 (5th Cir. 1981) (en banc)).22 23 24

Indeed, recent decisions of this Court require a judicial

22 Consent decrees thus allow the court to enter remedies that

correct past discrimination and then restore to the parties the

freedom to restructure their relationship under the terms of the

decree. See Spangler v. Pasadena City Board of Education, 611

F.2d 1239, 1242 (9th Cir. 1979) (Kennedy, J., concurring).

23 See, e.g., United States v. City of Miami, 664 F.2d 435, 441

(5th Cir. 1981) (en banc) (district court’s task before approving

Title VII consent decree is to determine that the decree is not

unlawful, unconstitutional, contrary to public policy, or unreason

able) ; United States v. City of Philadelphia, 499 F. Supp. 1196, 1199

(E.D. Pa. 1980) (sam e); Alexander v. Bahou, 86 F.R.D. 194, 198

(N.D.N.Y. 1980) (before approving Title VII consent decree, dis

trict court must be assured that its terms are not unlawful, unrea

sonable, or inequitable). Cf. Kelly v. Kosuga, 358 U.S. 516, 520

(1959) (court will not enforce a contract that violates the law).

24 p^r example, in the decision on review in Williams, the district

judge had declined to approve the consent decree because of its

potential impact on non-parties. Williams v. City of New Orleans,

543 F. Supp. 662 (E.D. La.), rev’d, 694 F.2d 987 (5th Cir. 1982).

14

determination of the impact of affirmative action relief

on third parties before such remedies may be approved.* 05

As the present case demonstrates, consent decree pro

cedures have evolved to provide substantial protection

for the interests of affected third parties. A fairness

hearing scheduled after reasonable notice to interested

persons provides a convenient and inexpensive forum for

those potentially affected by a decree. Such proceedings

assure that the decree may be considered, not just in the

abstract, but in terms of its actual operation.

Finally, consent decrees commonly provide for reten

tion of jurisdiction by the decree court to enforce, in

terpret, and monitor compliance with the decree. Judicial

efficiency is served because a forum familiar with the

decree and its factual background is available for reso

lution of future disputes. This feature also serves the

interests of parties by minimizing any possibility of in

consistent interpretations.

A. The Decision Below Undermines Incentives to Settle

Title VII Litigation

The decision below will inevitably frustrate incen

tives to settlement, resulting in a much larger volume

of litigation. Moreover, because this case presents an ex

treme example of litigants who deliberately declined an

opportunity to litigate in order to pursue an attack on

the decree in another proceeding, the endorsement of

their tactic by the court below necessarily endorses all

collateral attacks on consent decrees.

Under the decision below, the decree can be subjected

to seriatim attacks challenging its terms and legality.

As a result, a consent decree becomes the beginning of

litigation, rather than the end. If the rule adopted below

25 See Johnson v. Transportation Agency, Santa Clara County, 107

S. Ct. 1442, 1445 (1987); United Steelworkers v. Weber, 443 U.S.

193, 208 (1979).

15

were allowed to stand, approval of a consent decree would

initiate a protracted process that would involve the fed

eral courts in perpetual scrutiny of the employment prac

tices of local governments and private employers.

The broad rule adopted below deprives parties of much

of the benefit of resolving their disputes through consent

decrees, and it consequently creates a strong disincentive

to their use. The employer’s motivation to negotiate a

settlement would be substantially reduced because imple

mentation of the consent decree could continually force

the employer back into court to defend the decree.21'

Without some assurance of finality, the employer’s only

alternative might be to continue the litigation.

Plaintiffs are equally unlikely to consider a consent

decree an attractive alternative under the rule adopted

by the court below. For many plaintiffs who negotiate

consent decrees, a share of prospective opportunities for

employment and promotion is a critical element of the

overall bargain. Other claims, for back pay or specific

relief, may have been adjusted in negotiations in light

of the prospective relief. The prospect of collateral at

tacks on the decree, however, would make it impossible

for plaintiffs to be confident of retaining the benefits of

the bargain, even after the decree court’s approval. If

plaintiffs’ hard-earned rights to employment or promotion

stand to be undone when challenged by fellow employees,

they will be much less willing to compromise any claims

in a settlement.

B. The Decision Below Would Produce Repetitive,

Duplicative Litigation

In addition to raising virtually insurmountable ob

stacles to settlement of Title VII cases, the decision below

implicates broader issues of comity and judicial efficiency. 38

38 The employer might also be compelled to litigate its liability

under Title VII—the specific judgment it sought to avoid in

settling the case.

16

The Eleventh Circuit’s rule permitting collateral attacks

on consent decrees could result in the imposition of a

tremendous burden of unnecessary, duplicative litiga

tion.27 Under the decision below, any employee who de

clined to participate in the consent decree litigation but

claims an adverse effect due to the operation of the decree

could bring a separate lawsuit against the employer.28

Actions by even a small number of the employees af

fected by the operation of existing consent decrees would

not only unduly burden the parties, but would severely

tax judicial resources.

Moreover, nothing in the Eleventh Circuit’s decision

would limit this proliferation of litigation to the original

decree court. Instead, non-parties could simply sit back

and observe the principal litigation and, if it appeared

that the judge were inclined to approve the decree, choose

to refrain from participating directly in the action.29 By

27 These procedural, jurisdictional, and practical problems may

explain why this Court has never required Rule 19 joinder of

affected third parties. Accordingly, the lower courts have consist

ently proceeded on the assumption that non-minority employees are

not indispensable parties to Title VII actions. See, e.g., Kirkland v.

New York State Department of Correctional Services, 520 F.2d 420,

424 (2d Cir. 1975), cert, denied, 429 U.S. 823 (1976); English v.

Seaboard Coast Line Railroad, 465 F.2d 43, 46 (5th Cir. 1972) (it

is clear that Rule 19(a) does not require joinder of white employees

in every case in which their interests may be adversely affected).

28 The litigation history of the instant cases demonstrates that

this scenario is not unrealistically alarmist. Following entry of the

consent decrees, virtually every attempt by the City of Birmingham

to effect promotions pursuant to the decrees has prompted the filing

of discrimination charges with the EEOC. The fact that five sepa

rate reverse discrimination lawsuits involving 41 plaintiffs challeng

ing promotions made under the consent decrees have been brought

to date is compelling evidence that a rule permitting collateral

attacks engenders costly, repetitive litigation.

29 An inevitable consequence of this option is that the efficiency

of the consent decree process itself would be undermined. With such

a strong disincentive for interested parties to intervene, courts and

17

this strategy, non-parties could knowingly avoid having

their interests affected in the principal litigation in an

attempt to secure a more sympathetic forum.

The availability of a different forum or judge also

compounds the possibility that the separate actions would

result in judgments that conflict with a preexisting con

sent decree. Conflicting judgments could place employers

in the untenable position of being subject to contempt of

court citation for complying with either (or neither)

judgment.80 In this context conflicting judgments also

implicate well-established notions of comity because they

arise when one district court is asked to review another

court’s approval of a consent decree.131

Respondents’ conduct here exemplifies a form of claim

splitting that plainly could engender conflicting judgments

and impair judicial efficiency. They allowed the union to

stand as their surrogate at the fairness hearing but de- * 81

the parties will be handicapped in fashioning the decree in the first

instance for lack of input from all those whose interests may be

affected.

30 The problem of conflicting orders is dramatically illustrated by

the record in this case. See J.A. 208. The potential for imposition

of conflicting obligations is frequently recognized as a possible

result of permitting collateral attacks on consent decrees. See, e.g.,

Thaggard, 687 F.2d at 68; Stotts v. Memphis Fire Department, 679

F.2d 541, 559 (6th Cir. 1982), rev’d on other grounds sub nom. Fire

fighters Local Union No. 1784 v. Stotts, 467 U.S. 561 (1984) ;

Dennison, 658 F.2d at 695; O’Burn v. Shapp, 70 F.R.D. 549, 552

(E.D. Pa.), aff’dmem., 546 F.2d 417 (3d Cir. 1976), cert, denied, 430

U.S. 968 (1977); see also United Steelworkers v. Weber, 443 U.S.

193, 209-10 (1979) (Blackmun, J., concurring).

81 See, e.g., Goins, 657 F.2d at 64 (collateral attack on a consent

decree deemed an “ attempt to ‘appeal from one district judge to

another,’ ” which is barred by comity) (quoting Ellicott Machine

Corp. v. Modern Welding Co., 502 F.2d 178, 181 (4th Cir. 1974));

cf. Bergh v. Washington, 535 F.2d 505, 507 (9th Cir.), cert, denied,

429 U.S. 921 (1976) (comity considerations require judicial re

straint where requested relief would conflict with prior judgment).

18

dined the opportunity formally to participate in that pro

ceeding. When the union’s objections were rejected by

the decree court, respondents sought to present the very

same challenge to the decrees to a different judge.812

They vigorously opposed efforts to consolidate the reverse

discrimination lawsuits in a single action before Judge

Pointer. See J.A. 147, 196, 208. Such use of claim split

ting as a vehicle for forum shopping would be inevitable

if consent decrees were held subject to attack in separate

proceedings.

The claim splitting endorsed by the decision below also

offends basic principles of finality of judgments. While

the doctrine of res judicata is not applicable to the pres

ent case in a technical sense,®3 it is worth noting that the

doctrine

ensures “ the very object for which civil courts have

been established, which is to secure the peace and

repose of society by the settlement of matters cap

able of judicial determination. Its enforcement is

essential to the maintenance of social order; for, the

aid of judicial tribunals would not be invoked for

the vindication of rights of person and property, if

. . . conclusiveness did not attend the judgments of

such tribunals.”

Nevada v. United States, 463 U.S. 110, 129 (1983) (quot

ing Southern Pacific Railroad v. United States, 168 U.S.

1, 49 (1897)). To achieve that objective, the doctrine

extends both to claims actually raised and determined 32 33

32 Disappointed employees seeking to redress perceived violations

of their rights can be expected to make every effort to avoid

appearing before the judge that entered the decree; that judge has

already decided that the decree is fair and lawful. Respondents

made just such an effort here.

33 In order for res judicata to apply, the previous litigation must

have been between the same parties or their privies, or the party

being estopped must have had control over the prior litigation. See

18 C. Wright, A. Miller, & E. Cooper, Federal Practice & Procedure

§ 4451 (1981).

19

mid to claims that the parties could have litigated.

Brown v. Felsen, 442 U.S. 127, 131 (1979). Respondents

should not be “ at liberty to prosecute [a] right by piece

meal . . . presenting a part only of the available grounds

and reserving others for another suit.” Grubb v. Public

Utilities Commission, 281 U.S. 470, 479 (1930).84

Shorn of their verbiage, respondents’ complaints seek

merely to relitigate Judge Pointer’s determination that

the consent decrees are valid.135 Having had the opportu

nity to seek timely intervention and fully to present

their claims to the court at the fairness hearing— and

after the very same claims were actually considered by

the district court.— respondents should not now be per

mitted to wage a full scale collateral attack on the con

sent decrees.

II. REQUIRING INTERVENTION IS THE ONLY PRAC

TICAL MEANS TO' ACCOMMODATE THE INTER

ESTS OF THIRD PARTIES WHILE PRESERVING

THE VIABILITY OF THE CONSENT DECREE

PROCESS

A rule barring collateral attacks by persons who make

a knowing decision to forego formal participation in the

original consent decree adjudication is the only practical

means of accommodating both societal interests served by

Title VII consent decrees and individual opportunities to

be heard. Congress provided a framework for that bal- * 35

84 This Court has confirmed the importance of conformity to res

judicata principles in resolving fair employment claims. Kremer

v. Chemical Construction Corp., 456 U.S. 461 (1982) ; see also

Detroit Police Officers Association v. Young, 824 F.2d 512 (6th

Cir. 1987).

35 The first two complaints filed by respondents, in the Bennett

and Birmingham Association of City Employees cases, literally chal

lenged the validity of the decree. Pet. App. 110a; J.A. 93. While

the subsequent Wilks complaint avoided an express attack on the

decree, that artful pleading does not alter the fact that the com

plaint’s essential thrust is a full-scale attack on the decree. J.A. 130.

20

ancing of competing interests in Rule 24 of the Federal

Rules of Civil Procedure, which allows the entrance of

non-parties into actions in which their interests may be

substantially “ impaired or impeded” in their absence.

See Fed. R. Civ. P. 24 (a ) (2 ) . Rule 24 provides for

orderly disposition of non-parties’ claims in a single pro

ceeding, authorizing interested persons with knowledge

of the litigation and its potential effect on them to secure

a hearing.

Compulsory joinder of all non-minority employees pur

suant to Rule 19(a) of the Federal Rules of Civil Proce

dure is not a practical alternative to Rule 24 interven

tion because it creates insurmountable procedural difficul

ties. The first, of these involves statutory requirements

of Title VII. Non-minority employees may contend that

they cannot properly be joined as defendants because they

are not proper respondents under Title VII and thus

could not be subject to an Equal Employment Opportu

nity Commission ( “ EEOC” ) charge.®8 Similarly, non-

minority employees may not be subject to joinder as

plaintiffs, since they will not, in most cases, have filed

their own Title VII charges and will be unable to proceed

within the scope of the charges upon which the litigation

is based.* 87

In addition, requiring mandatory joinder would prove

unfair to both existing parties and potentially interested

third parties. It would place on the existing parties the

onus of determining who might be interested in the judg

38 Title VII limits the defendants subject to charges to. employers,

labor unions, agencies, and joint apprenticeships. 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-

5(b). The filing of a charge with the EEOC is a jurisdictional re

quirement. See 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(f) (1 ) ; Way v. Mueller Brass,

840 F.2d 303, 307 (5th Cir. 1988); Romain v. Kuret, 772 F.2d 281,

283 (6th Cir. 1985) ; Eggleston v. Chicago Journeymen Plumbers,

657 F.2d 890, 905 (7th Cir. 1981), cert, denied, 455 U.S. 1017 (1982).

87 Non-minority employees could not become members of the

existing plaintiff classes because their claims would be legally and

factually distinct from those typical of the classes. See Fed. R.

Civ. P. 23(a)(2 ).

21

ment, despite the potential parties’ superior knowledge

of their own interests. Without full understanding of

those interests, existing parties might choose to draw

broad groups of conceivably interested persons into the

litigation, encumbering already complex proceedings with

out enhancing third parties’ opportunities to be heard.

In the case of large employers, the costs to both parties

and the courts of litigating Title VII claims could rise

exponentially.

The difficulties inherent in broadly expanding Title VII

actions by joining all potentially interested parties could

not be avoided by attempting to name a defendant class

of non-minority employees. At the outset, it is currently

unclear whether Rule 2 3 (b ) (2 )— the class action pro

vision applicable in Title VII cases— even permits a de

fendant class. This Court granted certiorari in Henson

v. East Lincoln Township, 814 F.2d 410 (7th Cir. 1987),

cert, granted, 108 S. Ct. 691 (1988), to resolve precisely

that question.818

Beyond this, attempted invocation of class action mech

anisms would require the district courts to deal with a

tangle of procedural difficulties, including (1) determina

tion of the scope of the defendant class; (2) identification

of a representative who would be “ typical” of the pos

sibly thousands of employees involved; (3) investigation

of the representative’s ability to represent the class fairly

and adequately; and (4) selection of a competent attor

ney for the defendant class.38 39 Moreover, certification of

38 In Henson, the Seventh Circuit held that Rule 23(b)(2) did

not authorize defendant class actions. 814 F.2d at 417. Accord

Thompson v. Board of Education, 709 F.2d 1200, 1203-04 (6th Cir.

1983); Paxman v. Campbell, 612 F.2d 848, 854 (1980) (en banc),

cert, denied, 449 U.S. 1129 (1981). But see Marcera v. Chinlund,

595 F.2d 1231, 1238 (2d Cir.), vacated on other grounds sub nom.

Lombard v. Marcera, 442 U.S. 915 (1979).

39 See generally Note, Certification of Defendant Classes Under

Ride 23(b)(2), 1984 Colum. L. Rev. 1371, 1384-89 ( “Certifica

22

the defendant class might be denied on standing grounds

if plaintiffs could not demonstrate that their interests

were adverse to those of all proposed class members.40

Substantial questions of fairness to third parties also

arise, because the named representative—-despite a poten

tial lack of personal interest in the implementation of the

decree— would be forced to retain appropriate counsel,

assume responsibility for costs, and accept the obligation

of properly representing the class.41 In addition, these

obligations, to the class may make the representative un

able or unwilling to settle, burdening the court with liti

gation that might otherwise be concluded through negoti

ation. Rather than providing a procedural panacea, ad

dition of a defendant class to ongoing Title VII litigation

would only compound its complexity.

Given the massive practical difficulties that would be

created by requiring mandatory joinder under Rule 19,

Rule 24 is clearly the superior procedural mechanism for

tion” ). The adequacy of the representative would be a critical

issue that would determine the binding effect of any judgment on

the unnamed class members. See Hansberry v. Lee, 311 U.S. 32,

44-45 (1940) ; see also Wolfson, Defendant Class Actions, 38 Ohio

St. L. J. 459, 477 (1977).

40 See 7A C. Wright, A. Miller, & M. Kane, Federal Practice &

Procedure § 1770 at 403 (1986) ; Certification, 84 Colum. L. Rev. at

1375; see also LaMar v. H.&B. Novelty & Loan Co., 489 F.2d

461, 467 (9th Cir. 1973); Mudd v. Busse, 68 F.R.D. 522, 527 (N.D.

Ind. 1975), cuff’d mem., 582 F.2d 1283 (7th Cir. 1978), cert, denied,

439 U.S. 1078 (1979); Weiner v. Bank of King of Prussia, 358

F. Supp. 684, 690 (E.D. Pa. 1973).

41 See Wolfson, Defendant Class Actions, 38 Ohio St. L. J. 459,

464 (1977). Faced with the high costs of defending such litigation,

the involuntary class representative might well claim a violation of

his due process rights, adding a further complication to the litiga

tion. See Williams, Some Defendants Have Class: Reflections on

the GAP Securities Litigation, 89 F.R.D. 287, 293 (1981); see also

Kline v. Coldwell, Banker & Co., 508 F.2d 226, 235 (9th Cir. 1974),

cert, denied, 421 U.S. 963 (1975).

23

resolving the claims of informed third parties.42 While

both rules provide a means of involving non-parties in

litigation that may affect them, Rule 24, with its volun

tary component, is better able to deal with cases in which

the person has notice of the action and can decide whether

his interests warrant participation in the action.

Moreover, respondents here had an additional option

to participate, short of formal intervention, by appearing

at the fairness hearing. That hearing, held after

community-wide notice of the opportunity to appear and

participate, provided respondents with an effective means

of raising all their challenges to the decrees’ factual

foundation, terms, and design, including any alleged

trammeling effect arising from the decrees. As the trans

cript of that hearing amply demonstrates, the district

court was scrupulous in providing all interested persons

the opportunity to be heard. J.A. at 727. Respondents,

who declined formally to participate in that proceeding,

cannot establish any procedural or equitable right to an

additional opportunity to assert their claims.

CONCLUSION

The lule of law adopted by the court below undermines

strong statutory policies encouraging voluntary settle

ment of Title VII actions and ignores fundamental poli

cies favoring finality of decrees and judgments. This

Court should reject the broad rule adopted below and re

quire employees with knowledge of ongoing Title VII liti

gation against their employers to take the initiative in

protecting their own interests. Neither the Federal Rules

42 Neither the text nor the legislative history of these rules re

quires a preference for mandatory Rule 19 joinder over voluntary

Rule 24 intervention. See Fed. R. Civ. P. 24 advisory committee

note (1966 Amendment); see also New York State Association for

Retarded Children v. Carey, 438 F. Supp. 440, 445 (E.D.N.Y. 1977)

(the only difference between intervention under Rule 24 and joinder

under Rule 19 “ is which party initiates the addition of a new party

to the case” ).

24

of Civil Procedure nor the Constitution grants individuals

such as respondents the right to waive formal participa

tion in ongoing proceedings and then relitigate identical

issues in their chosen forum. Accordingly, where the

non-parties to a consent decree have knowledge of the

proceeding and a timely opportunity to intervene but

choose not to do so, they should be precluded from at

tacking the terms or legality of the consent decree in a

subsequent collateral proceeding.

Of Counsel:

Barry L. Goldstein

NAACP Legal Defense &

Educational Fund, Inc.

Suite 301

1275 K Street

Washington, D.C. 20005

Julius LeVonne Chambers

Ronald L. Ellis

NAACP Legal Defense &

Educational Fund, Inc .

Suite 1600

99 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10013

Claudia W ithers

W omen ’s Legal Defense Fund

2000 P Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20036

Marcia D. Greenberger

Brenda Smith

National W omen ’s Law Center

Suite 100

1616 P Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20036

William C. McNeill, III

Eva Jefferson Paterson

301 Mission Street

Suite 400

San Francisco, California 94105

Attorneys for International

Association of Black

Professional Firefighters

Respectfully submitted,

N. T hompson Powers

Ronald S. Cooper

(Counsel of Record)

Janice Barber

Steptoe & Johnson

1330 Connecticut Avenue, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20036

(202) 429-3000

Attorneys for Amici Curiae

NAACP Legal Defense &

EducoMonal Fund, Inc.,

Women’s Legal Defense

Fund, National Women’s

Law Center, and Inter

national Association of

Black Professional

Firefighters

August 18, 1988