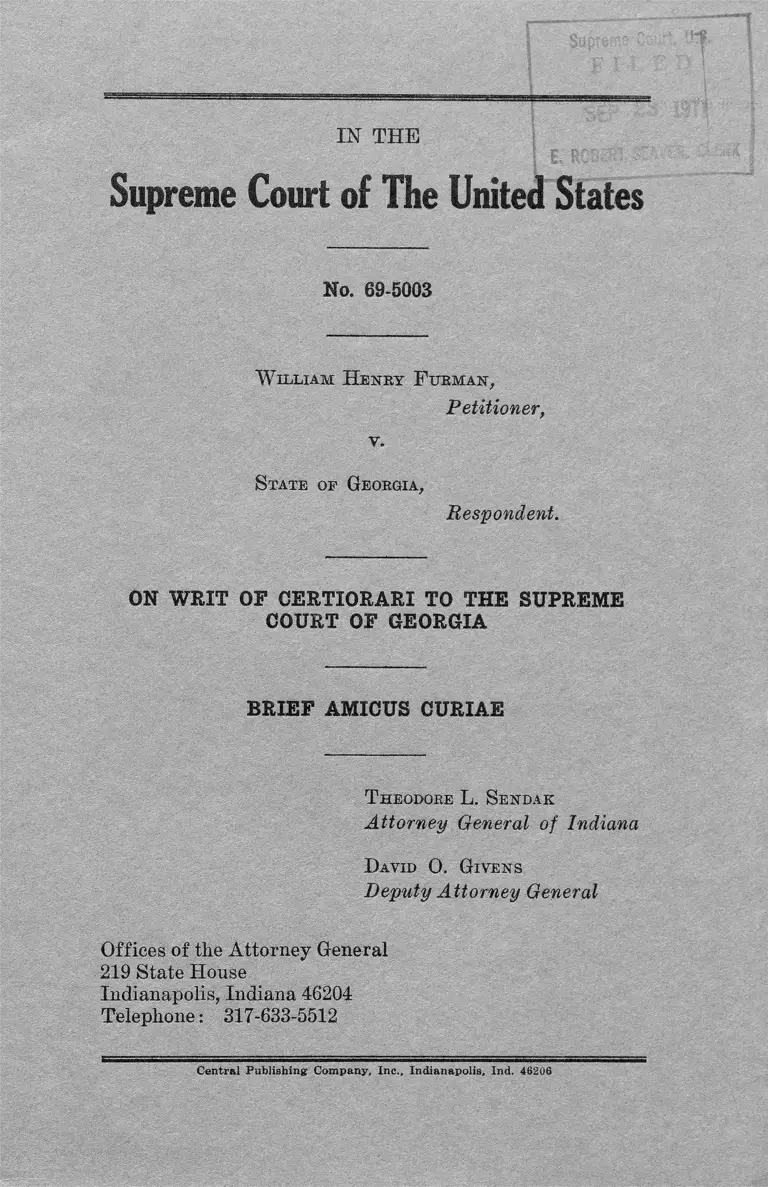

Furman v. Georgia Brief Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

September 23, 1971

This item is featured in:

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Furman v. Georgia Brief Amicus Curiae, 1971. 78e6d78a-b29a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/7c1b0b2f-2241-4ddc-bef8-fda7514f1ce5/furman-v-georgia-brief-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 14, 2026.

Copied!

IN THE

Supreme Court of The United States

No. 69-5003

W illiam H usky F urman,

Petitioner,

v .

State op Georgia,

Respondent.

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE SUPREME

COURT OF GEORGIA

BRIEF AMICUS CURIAE

T heodore L. S endak

Attorney General of Indiana

David O. Givens

Deputy Attorney General

Offices of the Attorney General

219 State House

Indianapolis, Indiana 46204

Telephone: 317-633-5512

C entral Publish ing Company, Inc., Indianapolis, Ind. 46206

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Table of Authorities ...................................................... ii

Question presented for review......... ............................ 2

Statement of the case .................................................... 2

Summary of the argum ent.................................. 2

Argument ............................................... 4

Conclusion ................................................. 15

i

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases: Page

Adams v. State (1971), 271 NE 2d 425 .................... 8

Bailey v. United States (1934), 74 F. 2d 451......... . 7

Robinson v. California (1962), 370 U.S. 660 ........... 4

Troy v. Dulles (1958), 356 U.S. 86 ..........................3, 5,6

Weems v. United States (1910), 217 U.S. 349 ............. 8

Miscellaneous:

Barshay, Sr. Schol. 71:6 .............................. 15

Gerstein, J. Crim. L. 51:252 (1961) ......................... 10

Harvard Law Review, 79:635 (1966) ........................ 8,9

Parry, History of Torture in England 9 (1934) ......... 5

Royal Commission on Capital Punishment, Report 18,

note 15 ....................................................................... 13

Sendak, Vital Speeches of the Day, July 1, 1971 . .11,12,13

Sherman, 14 Crim and Delinquency 73, (1968) ......... 5

William & Mary, Sess 2, Ch. 2 ..................................... 4

United States Constitution:

Fifth Amendment ................................................... Passim

Eighth Amendment ............................................... Passim

Fourteenth Amendment ................ Passim

Indiana Constitution:

Article I, Section 16 .................................................... 1

Indiana Statutes:

IC 1971 35-1-46-9 et. seq. (Burns’ Section 9-2236 et.

seq.) ................................................ 2

ii

IN THE

Supreme Court of The United States

No. 69-5003

W illiam H enry F urman,

Petitioner,

v.

State oe Georgia,

Respondent.

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE SUPREME

COURT OF GEORGIA

BRIEF AMICUS CURIAE

The interest of the State of Indiana is in the preserva

tion of the Indiana Constitution and statutes that are

directly analogous to those in question. In the Bill of

Rights of the Indiana Constitution, at Section 16, it is pro

vided that:

“ Excessive bail shall not .be required. Excessive fines

shall not be imposed. Gruel and unusual punishments

1

2

shall not he inflicted. All penalties shall he propor

tioned to the nature of the offense.” (My emphasis.)

Indiana statutes, IC 1971, 35-1-46-9, as found in Bums’

(1956 Repl.) Section 9-2236 et. seq. provide for the death

penalty by electrocution.

QUESTION PRESENTED FOR REVIEW

Whether Georgia’s statute allowing the death penalty

for a conviction of. first, degree murder constitutes cruel

and unusual punishment in violation of the Eighth and

Fourteenth Amendments to the United States Constitu

tion.

■ STATEMENT OF THE CASE

The Statement of the Case contained in the Brief of

Respondent is accurate and concise and is referred to here.

; y . v /; ;; . . - : / ■' »

SUMMARY OF THE ARGUMENT

Capital punishment is not “ cruel and unusual punish

ment’’ in violation of the Eighth Amendment. The framers

of the Bill of Rights had in mind the abolishment of other

penalties such as those attributed to the infamous English

Court of Star Chamber.

The Fifth Amendment, which was ratified at the same

time as the Eighth Amendment, only requires that due

process be observed in assessing the ultimate penalty. The

intent of the framers is to be found in the explicit language

of the Fifth Amendment and not in the nebulous “ cruel

and unusual punishment” phrase contained in the Eighth

Amendment; which has until this day defied precise def

inition.

3

Petitioners argue that the “ cruel and unusual punish

ment” clause should be viewed from the ‘! evolving

standards of decency that mark the progress of a maturing

society.” 1 In their view, a majority of the population is.

opposed to capital punishment and, because of this, the

penalty is no longer acceptable. Yet at the same time, they

argue that neither legislation nor constitutional amend

ment is an effective means for changing the law because

public feeling is not strong enough to compel change,

either in Congress or the state legislatures. By this reason

ing, they attempt to justify: change in the law through

judicial action rather than by proper legislation or consti

tutional amendment.

Capital punishment is a deterrent to future crime. It'

is argued by opponents that statistical evidence refutes1

this reasonable conclusion. However, the statistics which

form the basis of the petitioner’s argument omit all the

essential subjective variables and are therefore of limited

value. This issue is far too important to be decided ex

clusively by bare statistics'.

Capital punishment was contemplated by the framers

of the Bill of Rights and the concept was re-affirmed in

1869 when the authors of the Fourteenth Amendment

borrowed the explicit language of the Fifth Amendment

which allows the death penalty provided due process, has)

been, observed. ... .

1 Trop v. Dulles (1958), 356 U.S. 86, 101

ARGUMENT

The issue involves a question of whether capital punish

ment is in violation of the “ cruel and unusual punish

ment” clause of the U. S. Constitution, Eighth Amend

ment. This amendment provides that:

“ Excessive bail shall not be required, nor excessive

fines imposed, nor cruel and unusual punishments in

flicted. ’ ’

The Fifth Amendment of the Constitution of the United

States included capital punishment in its scope. Histori

cally the Fifth and Eighth Amendments were ratified to

gether as part of the Bill of Eights. The Fifth Amend

ment states in part, that:

“ No person shall . . . be deprived of life, liberty, or

property, without due process of law; . . . ”

This same language appears again in the Fourteenth

Amendment of the United States Constitution, which

states, in part, that:

“ . . . nor shall any state deprive any person of life,

liberty, or property, without due process of law; . . .”2

The Eighth Amendment was adopted as part of the Bill

of Rights in 1791. This wording initially appeared in the

Act of Parliament of 1688,3 to abolish the atrocities of

the English .Court of the Star Chamber. In that

“ judicial” body, confessions were extracted in open court

2 Robinson v. California (1962), 370 US 660

3 William and Mary, Sess. 2, ch. 2 at 192 (1869)

4

5

through various diabolical means, and the punishments

that were meted out included the loss of ears for perjurers,

face branding and nose splitting for forgers and con

spirators, and whipping for those guilty.of “ unnatural”

offenses.4 The adoption of the Eighth Amendment ver

batim from the 1688 Act of Parliament, with no reported

controversy, would suggest that it was intended to apply

to the kinds of medieval torture described above.5

Courts which have heard questions of “ cruel and un

usual punishment” have refused to follow the inflexible

theory that cruel and unusual punishment must be de

termined by the same standards that were in effect at the

time of the drafting of the Bill of Rights. They have con

tinually applied a less rigid standard of “ a developing

and maturing society.” Opponents of capital punishment

have ignored this judicial test and have erroneously

stated that our society has progressed to the point that

capital punishment is no longer acceptable. Chief Justice

Warren, in the majority opinion in Trop v. Dulles

(1958), 356 U.S. 86, 100, explained that:

“ The exact scope of the constitutional phrase ‘.cruel

and unusual’ has not been detailed by this court. But

the basic policy reflected in these words is firmly es

tablished in the Anglo-American tradition of criminal

justice. The phrase in our Constitution was taken

directly from the English Declaration of Rights of

1688, and the principle it represents can be traced

back to the Magna Carta. The basic concept under

lying the Eighth Amendment is nothing less than the

dignity of man. While the state has the power to pun

ish, the Amendment stands to assure that this power

be exercised within the limits of civilized standards.”

4 Parry, “The History of Torture in England,” 9 (1934)" '

5 Sherman, “----Nor Cruel and Unusual Punishments In

flicted,” 14 Crime and Delinquency 73, (1968)

6

Indeed, in the same decision, Trop v. Dulles, supra,

Chief Justice Warren expressly recognized the necessity

of the retention of capital punishment where the offense

requires its imposition. He stated that:

“Fines, imprisonment and even execution may be im

posed depending upon the enormity of the crime, but

any technique outside the bounds of these traditional

penalties is constitutionally suspect . . . The Amend

ment must draw its meaning from the evolving

standards of decency that mark the progress of a

maturing society.” (My emphasis.)

It must be emphasized that although Chief Justice

Warren recognized the flexible standard of contemporary

society, he did not find that capital punishment was un

constitutional when the facts of the case showed that the

death penalty was proportionate to the severity of the

crime. In the case presently being considered, the death

penalty was imposed as a just and proportionate punish

ment for a cold-blooded and wanton murder.

Opponents have never presented sufficient evidence to

show that opposition to the death penalty is, indeed, as

widespread as they would have us believe. Chief Justice

Warren, in Trop v. Dulles, supra, at 99, further stated

that:

“ Whatever the arguments may be against capital

punishment, both on moral grounds and in terms of

accomplishing the purposes of punishment—and they

are forceful—the death penalty has been employed

throughout our history, and, in a day when it is still

widely accepted, it cannot be said to violate the con

stitutional concept of cruelty.” (My emphasis.)

At this point, opponents introduce numerous polls to

show that a certain percent of the population is opposed

7

to capital punishment. Without going into the myriad of

problems inherent in these polls and the accuracy of their

findings, one point remains a mystery. If the anticapital

punishment advocates are so sure of public opinion, why

are they not willing to submit this question to the voters

in a referendum; or why do they feel that state and

federal legislators are not sufficiently in tune to realize the

alleged feeling against this punishment! The fallacy in

the reasoning of the opponents is quite obvious. They con

tinually talk of the ‘great movement’ to abolish the death

penalty. They say that since the citizens of the United

States are against this punishment, it no longer meets

the “ standards of decency that mark the progress of a

maturing society.” At the same time, they state that this

change must be initiated through the courts as public

opinion is not sufficiently strong to influence this

change through legislation. Obviously, one of their con

clusions is erroneous, and they are asking the Court to

usurp this legislative function. The fixing of penalties for

crimes has always been a legislative function, and courts

should intervene only when the legislative discretion is

violated.

In Bailey v. U.S. (1934), 74 P. 2d 451, the opinion of

the 10th Circuit Court of Appeals stated that:

“ The fixing of penalties for crimes is a legislative

function. What constitutes an adequate penalty is a

matter of legislative judgment and discretion, and the

courts will not intervene therewith unless the penalty

prescribed is clearly and manifestly cruel and un

usual.”

(A reading of cases in this area fails to develop an ade

quate definition of “ cruel and unusual.” Also, the courts

which have considered whether there is a difference be

8

tween “ cruel” and “ unusual” have not arrived at a pre

cise distinction between the two terms.)

The dissenting opinion of Mr. Justice White in Weems

v. U.S. (1910), 217 U.S. 349, stated that:

“ This interpretation curtails the legislative power of

Congress to define and punish crime by asserting a

right of judicial supervision over the exertion of that

power, in disregard of the distinction between the

legislative and judicial departments of Government.”

In Adams v. State (1971), 271 NE 2d 425, the Indiana

Supreme Court viewed its function as follows:

“ We feel the question in our jurisdiction hardly needs

to be discussed, since precedent and authority have

determined the question against the position taken

by the appellant; and although a judge may personally

not approve the punishment fixed by the legislature

for some crimes, it is not the judge’s privilege, be

cause he does not agree with the legislative policy,

to attempt to nullify legislative enactment. We would

be violating our oaths and stepping outside our juris

dictional function to do so.”

The entire argument of the desirability of legislative

change or judicial decision was summarized in 79 Harvard

Law Review 635, 639 (1966):

“ In light of these difficulties and the uniform au

thority sustaining capital punishment, to hold that

it is a method of punishment wholly prohibited by

the eighth amendment would be to confuse possible

legislative desirability with constitutional require

ments.”

The desire of some advocates for social change should

not be confused with the desire of the entire nation for

a constitutional amendment. How can capital punishment

9

be abolished by a judicial tribunal, albeit the United

States Supreme Court, without, in effect, amending the

Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments? Since the death pen

alty is not cruel and unusual, any change ought to be

sought through legislation or by a constitutional amend

ment.

There are several reasons for the privacy, not secrecy,

of legal executions in the United States. An execution has

a deterrent effect only to the degree that a person con

templating the crime has knowledge of the penalty at

tached to the crime committed. In this day and age, this

knowledge is not acquired by means of public executions.

Are the opponents so naive as to think the potential crim

inal is unaware of the death penalty unless he is re

minded by a public execution?

The privacy of executions is evidence that as a develop

ing and maturing society, we are simply insuring the

dignity of man. There is no reason to put the families of

those sentenced to execution through the traumatic experi

ence of a public display since the deterrent effect is the

knowledge that the death penalty is imposed. Any reason

able person dislikes confinement but this attitude does

not buttress the conclusion that he is against imprison

ment for crime or that he wishes to abolish sentences of

incarceration.

It is well to remind ourselves of the purpose of legal

punishment itself. “ Punishment is ordinarily justified

under a utilitarian theory as being necessary for the

achievement of a long-range benefit.”6 The long range

benefit discussed in relation to punishment is its deterrent

effect, which is often defined as the preventive effect

6 Harvard Law Review, 79:635 (1965-66)

10

which actual or threatened punishment of offenders has

upon potential offenders. This principle has always in

fluenced our penal codes and is largely responsible for

the lawful and justified use of capital punishment.

Bichard M. Gerstein, State Attorney for Dade County,

Miami, Florida, stated that:

“ As do many members of our profession, I take the

position that deterrence is necessary for the mainte

nance of the legal system and the preservation of

society, as clearly stated by Sir John Salmond:

‘ Punishment is before all things deterrent, and

the chief end of the law of crime is to make the

evil doer an example and a warning to all who

are likeminded with him.’ ” 7

The deterrent effect of the death penalty is a vital con

sideration in discussing the necessity of its retention. The

basic question to be considered here is the deterrent effect

on potential offenders. In other words, does the knowl

edge that he may be executed have a discernible influence

on the potential murderer’s decision to commit the murder

or the felony that leads to the murder. It is the contention

of a vast majority of prosecutors that the deterrent effect

of capital punishment is significant. Forgetting for the

moment the wealth of evidence available to substantiate

its deterrent effect, we should rely more on the prac

titioner instead of the academic reformer. We should be

lieve the person who deals with the accused murderer in

the real-life situation, rather than the person who has an

alyzed what he would or should have done in a clinical

psychological vacuum.

7 Gerstein, J. Crim. L. 51:252 (1961)

11

Vital Speeches of the Day recently carried the following

pertinent observations from a presentation on law enforce

ment :

“ The propaganda drive to abolish capital punishment

appears to be a geared part of a general drive

toward leniency in the treatment of criminals in our

society. Such leniency has, in my opinion, had un

deniable psychological impact on potential murderers,

and has contributed to the upward spiral of the crime

rate. There is a striking over-all correlation between

the recent decline in the use of the death penalty and

the rise in violent crime. Such crime has increased

by geometric proportions.

In the first three years of the last decade, the number

of executions in the United States was by present

. standards relatively high. Fifty-six persons were exe

cuted in 1960; 42 in 1961; and 47 in 1962. During these

same three years the number of people who died

violently at the hands of criminals actually declined

and the murder rate per 100,000 of population also

declined.

Beginning in 1963, however, there was a drop in the

number of legal executions, and the graph line of

violent crime simultaneously began moving up instead

of down. In the following years the number of legal

executions has decreased dramatically from one year

to the next, until in 1968 there was none at all. But

each of those years has seen murders increase sharply

both in absolute numbers and as a percentage of popu

lation.

In 1964, for example, the number of legal executions

dropped to 15. Yet the number of violent deaths

moved up from 8,500 to 9,250, and the murder rate

per 100,000 went up from 4.5 to 4.8. In 1965, the num

ber of legal executions dropped to seven, while the

number of violent deaths increased to 9,850, and the

murder rate went to 5.1. Similar decreases in legal

12

executions have occurred in the following years ac

companied by similar increases in the murder rate.

In 1968, with no legal executions at all, the total

number who died through criminal violence reached

13,650, while the murder rate climbed to 6.8 per

100,000.

The movement in these figures, with murders increas

ing as the deterrence of the death penalty diminished,

confirms the verdict of ordinary logic: That a relaxa

tion in the severity and certainty of punishment leads

only to an increase in crime.

These remarks concern the deterrent effect of the

death penalty on those who might commit murder but

do not. That is a negative phenomenon which can be

inferred both from the record and the assessment of

common sense. The repeal of the death penalty would

not repeal human nature. To these truisms we may

add the fact that there are numerous cases on record

in which criminals have escaped the capital penalty

for previous murders and gone on to commit

others . . .

Is a course of action humanitarian which actually en

courages a vast and continuing increase in the number

of people killed and maimed and otherwise brutal

ized? There have been many sentimental journeys into

the psychological realm of the criminals who are to

be executed; I think there should be more sympathetic

concern expressed for the thousands of innocent vic

tims of those criminals.

Opponents of the death penalty may rejoice that in

1968 there were 47 fewer murderers executed in this

country than was the case in 1962; but, do they say

anything of the fact that some 5,150 more innocent

persons died by criminal violence in 1968 than was

the case in 1962?

In the question of human suffering, this is a stagger

ing loss of more than 5,000 individual innocent lives.

13

What about the human rights and civil rights of the

individual victim? Are not those 5,000 persons en

titled to the dignity and sacredness of life! Is that

a result of which humanitarians can be proud? I think,

not.

Only misguided emotionalism., and not facts, dispute

the truth that the death penalty is a deterrent to

capital crime.

Individuals must be held responsible for their indi

vidual actions if a free society is to endure.”8

Additionally, the Royal Commission on Capital Punish

ment made the following finding in relation to deterrence

and. the abolition of capital punishment:

“ The general conclusion which we reach, after care

ful review of all the evidence we have been able to

obtain as to the deterrent effect of capital punish

ment, may be stated as follows. Prima facie the pen

alty of death is likely to have stronger effect as a de

terrent to normal beings than any other form of

punishment and there is some evidence (though no

convincing statistical evidence) that this is in fact

so.” (My emphasis.)9

The statistics used to minimize the deterrent effect of

capital punishment categorically omit the essential vari

ables that would have, otherwise, given these statistics

some meaning. One of the most glaring omissions from

the statistical standpoint is the input of common sense.

If the death penalty is no more of a deterrent than life

imprisonment, as the opponents would have us believe,

8 Sendak, Vital Speeches of the Day, Vol. 38, No. 18, page

574, (July 1, 1971)

9 Royal Commission on Capita] Punishment, Report 18, note

15 at page 24.

14

why do convicted murderers exhaust all legal barriers in

attempting to get a death sentence commuted to life im

prisonment! They want us to believe that at the time just

prior to and during the act, the criminal sees no dis

cernible difference between life and death, but upon ap

prehension, he suddenly feels the importance of life

imprisonment. It is the contention of this Amicus Curiae

that deductive, reasoning leads to the conclusion that in

view of the importance of life imprisonment over the

death penalty to those who are awaiting execution, this

same importance must, either' consciously or sub

consciously, be in the mind of the potential slayer as he

is preparing to perpetrate his crime. It is, therefore, a

deterrent.. ; _

Further evidence of the unreliable nature of the op

ponents’ statistics on the deterrent effect of the death

penalty is that none of their statistics shows the number

of persons who were aware that they could be put to death

for their act, and for that reason decided not to perpetrate

the crime. Their statistics only show the failure, i.e. the

persons who were not deterred and actually committed

the crime. No one can reduce to cold, impersonal, statisticaj..

columns: the number: of persons who have refrained from:

murder because of Tear of the death penalty. There is’nd

way to : gauge this most essential variable. Judge Hyman

Barshay had this fact in mind when he made the follow

ing observation:

“ The death penalty is a warning, just like h light-

v.: house throwing.its. beam.out ,to. ,sea. .We hear abqut

the shipwrecks, but we do not hear aboyl jj*ei. ships'

15

that the lighthouse guides safely on their way. We

do not have proof of the number of ships it saves, but

we do not tear the lighthouse down.”10

CONCLUSION

Capital punishment is not in violation of the United

States Constitution. Attackers of the death penalty rely

on the ambiguous and elusive “ cruel and unusual punish

ment” clause of the Eighth. Amendment in the attempt

to have it declared unconstitutional. These attackers ig

nore the explicit language of the contemporaneous Fifth,

and Fourteenth, Amendments that recognize capital pun

ishment provided due process is observed.

Those who wish to abolish capital punishment say, with

out proof, that it is now offensive to the general popula

tion. If and when the voice of the people is strongly

against capital punishment, their representatives in

Congress and the legislature will change the laws and

amend the Constitution to abolish it. There have been,

to date, twenty-six amendments to the United States

Constitution which clearly shows that there is no necessity

for the Judiciary to take over that procedure instead of

utilizing the prescribed procedures for constitutional

amendment.

Opponents of capital punishment document their case

with statistics which are intended to show that there is

no deterrent effect in the death penalty. But strong sta

tistics also buttress support of capital punishment. Capital

punishment is, in fact a deterrent and is not in violation

of the United States Constitution.

10 Sr. Schol., Capital Punishment: Pro and Con. 71:6.

Therefore, the decision of the Georgia Supreme Court

upholding the constitutionality of capital punishment for

conviction of first degree murder should he affirmed.

Respectfully submitted,

T heodore L. S en d a k

Attorney General of Indiana

D avid 0 . Giv e n s

Deputy Attorney General

Offices of the Attorney General

219 State House

Indianapolis, Indiana 46204

Telephone: 317-633-5512

\

EDC? 6 l 6 / S p r i n g , 1978 Huffm an

S tudy- Q u e s t io n s f o r C l i e n t - C e n te r e d T h erap y

1 . Do you b e l i e v e t h a t m ost c l i e n t s have th e c a p a c i ty to u n d e rs ta n d

and r e s o l v e t h e i r own p ro b lem s w ith o u t d i r e c t i v e ty p e s o f

i n t e r v e n t i o n by th e c o u n s e lo r ? Why o r why n o t?

2 . What p ro b lem s do you s e e f o r th e c o u n s e lo r who o n ly s u p e r f i c i a l l y

a c c e p t s th e key c o n c e p ts and p h ilo s o p h y o f th e c l i e n t - c e n t e r e d

a p p ro a c h ? Can a c o u n s e lo r who d o e s n 't f u l l y em brace t h a t p h i l o

so p h y r e a l l y be e l l e n t - c e n t e r e d ?

3 . Do you t h i n k t h a t th e c l i e n t - c o u n s e l o r r e l a t i o n s h i p o f th e

c l i e n t - c e n t e r e d m odel i s s u f f i c i e n t to e f f e c t b e h a v io r and

p e r s o n a l i t y c h a n g e s i n th e c l i e n t ? Why o r why n o t?

k . I n i t s s t r e s s on th e a c t i v e r o l e o f th e c l i e n t , do you se e th e

a p p ro a c h a s r e l o c a t i n g th e c o u n s e lo r to a p a s s iv e r o l e ? E x p la in .

5 . Do you b e l i e v e t h a t m in im iz in g te c h n iq u e s and s t r e s s i n s c l i e n t -

c o u n s e lo r r e l a t i o n s h i p s a r e s t r e n g t h s o r w e ak n e sse s in th e

a p p ro a c h ? E x p la in .

6 . W hat, i n you v iew , a r e th e m a jo r s t r e n g t h s and w e ak n e sses o f

th e c l i e n t - c e n t e r e d a p p ra c h ? E x p la in .

7 . R o v ers a d v o c a te s a p h e n o m e n o lo g ic a l a p p ro a c h n o t o n ly to

h c o u n s e l in g b u t a l s o to r e s e a r c h . Can "p h e n o m e n o lo g ic a l

kn o w led g e" be a c c e p ta b l e a s s c i e n t i f i c d a ta ? Why o r why n o t?

. P r a c t i c a l a p p l i c a t i o n s - you sh o u ld be a b le t o : a ) i d e n t i f y

i n c o n g r u i t i e s o r i n c o n s i s t e n c i e s i n what t h e c l i e n t s a y s o r

does ( v e r b a l s and n o n - v e r b a l s ) and , b) u n d e r s t a n d t h e c l i e n t ' s

i n t e r n a l f r ame o f r e f e r e n c e .

8