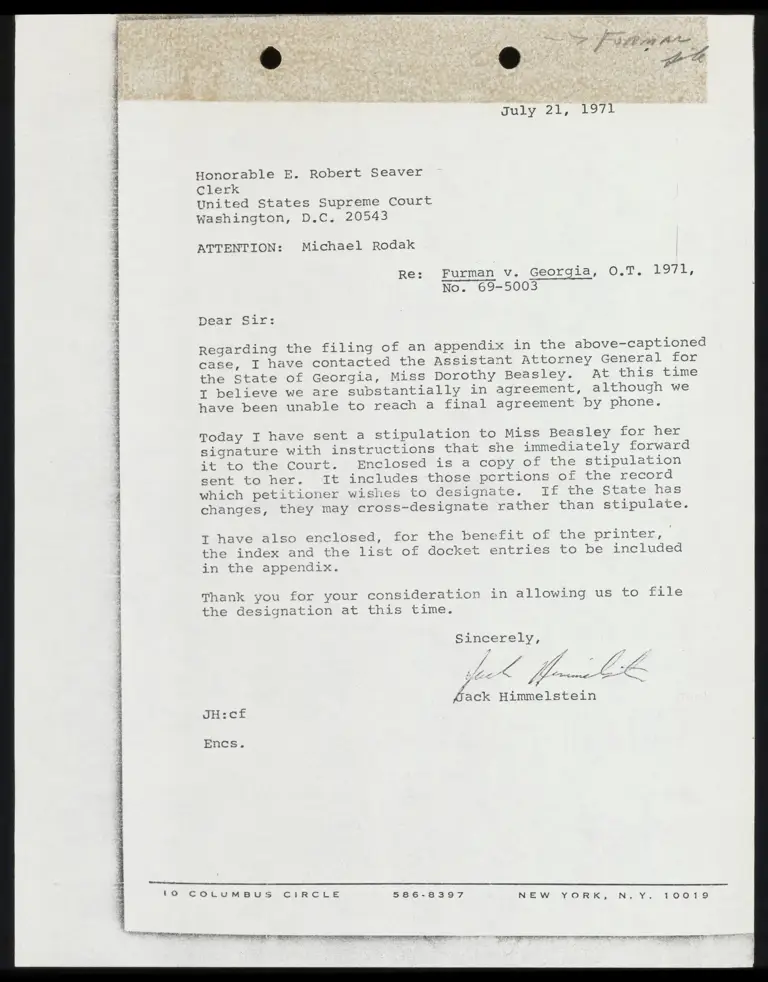

Correspondence from Himmelstein to Clerk Re Filing Appendix

Correspondence

July 21, 1971

1 page

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Furman v. Georgia Hardbacks. Correspondence from Himmelstein to Clerk Re Filing Appendix, 1971. e45fb9f1-b425-f011-8c4d-0022482c18b0. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/7ca35808-2eee-420a-b7e0-39efb59b4b42/correspondence-from-himmelstein-to-clerk-re-filing-appendix. Accessed February 20, 2026.

Copied!

2

: a pv pas #1 a 29

a

4 »

5

{ ) 7%

: 4

»

|

A hs

|

i July 21, 1971

3 Honorable E. Robert Seaver

3 Clerk

3 United States Supreme Court

3 washington, D.C. 20543

ATTENTION: Michael Rodak

: Re: Furman v. Georgia, 0.T. 1971,

] No. 69-5003

§ Dear Sir:

:

2 Regarding the filing of an appendix in the above-captioned

: case, I have contacted the Assistant Attorney General for

: the State of Georgia, Miss Dorothy Beasley. At this time

T believe we are substantially in agreement, although we

have been unable to reach a final agreement by phone.

Today I have sent a stipulation to Miss Beasley for her

signature with instructions that she immediately forward

! it to the Court. Enclosed is a copy of the stipulation

: sent to her. It includes those pcrtions of the record

4 which petitioner wishes to designate. if the State has

: changes, they may cross-designate rather than stipulate.

: T have also enclosed, for the benefit of the printer,

: the index and the list of docket entries to be included

; in the appendix.

Thank you for your consideration in allowing us to file

the designation at this time.

4

Sil TN / ~

=

Vib -

J

4

/

Jack Himmelstein

JH:cf

i Encs.

]

53

i 10. 3 COLUMBUS CIRCLE 586-8397 NEW YORK, N.Y. 100169

FE EM BIO Ye mar ee Gates Gahan gus str Lr.

I ME wssmmn —___ DMR ASA N——————— wm I IITII_;—__—