Ingram Equipment Company, Inc. McGinnis Brief Amici Curiae in Support of Plaintiff-Appellee

Public Court Documents

April 20, 1990

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Ingram Equipment Company, Inc. McGinnis Brief Amici Curiae in Support of Plaintiff-Appellee, 1990. e00206c8-b89a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/7ca36be3-fa74-4052-8cfd-6bb893905f16/ingram-equipment-company-inc-mcginnis-brief-amici-curiae-in-support-of-plaintiff-appellee. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

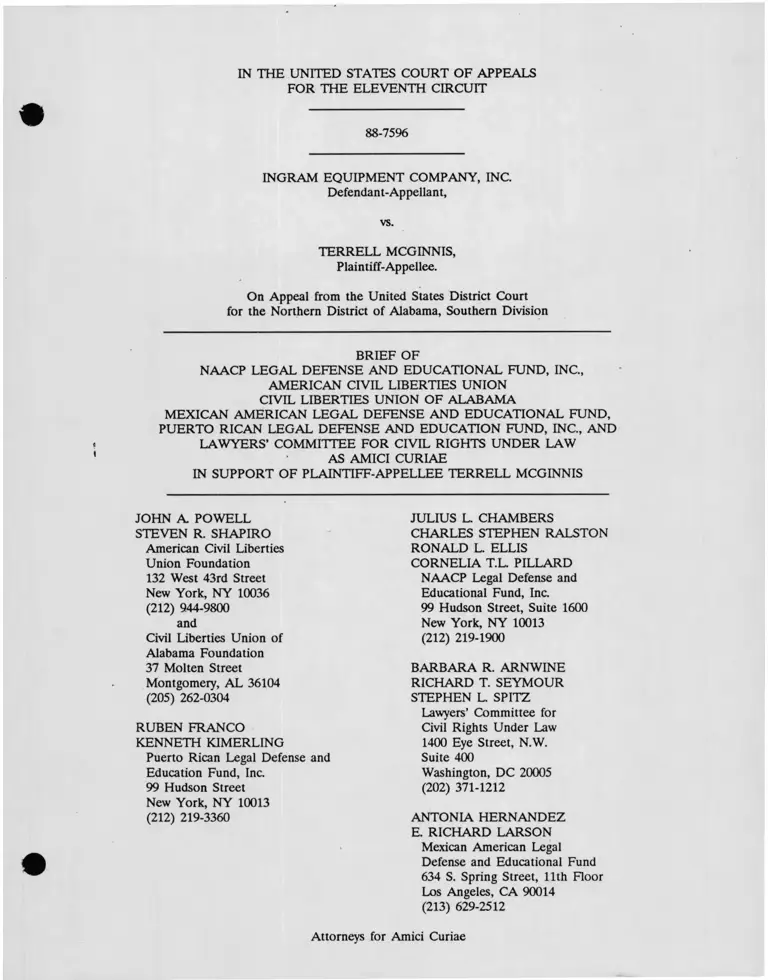

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE ELEVENTH CIRCUIT

88-7596

INGRAM EQUIPMENT COMPANY, INC.

Defendant-Appellant,

vs.

TERRELL MCGINNIS,

Plaintiff-Appellee.

On Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Northern District of Alabama, Southern Division

BRIEF OF

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC.,

AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION

CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION OF ALABAMA

MEXICAN AMERICAN LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND,

PUERTO RICAN LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATION FUND, INC., AND

LAWYERS’ COMMITTEE FOR CIVIL RIGHTS UNDER LAW

AS AMICI CURIAE

IN SUPPORT OF PLAINTIFF-APPELLEE TERRELL MCGINNIS

JOHN A POWELL

STEVEN R. SHAPIRO

American Civil Liberties

Union Foundation

132 West 43rd Street

New York, NY 10036

(212) 944-9800

and

Civil Liberties Union of

Alabama Foundation

37 Molten Street

Montgomery, AL 36104

(205) 262-0304

RUBEN FRANCO

KENNETH KIMERLING

Puerto Rican Legal Defense and

Education Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street

New York, NY 10013

(212) 219-3360

JULIUS L. CHAMBERS

CHARLES STEPHEN RALSTON

RONALD L. ELLIS

CORNELIA T.L. PILLARD

NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street, Suite 1600

New York, NY 10013

(212) 219-1900

BARBARA R. ARNWINE

RICHARD T. SEYMOUR

STEPHEN L. SPITZ

Lawyers’ Committee for

Civil Rights Under Law

1400 Eye Street, N.W.

Suite 400

Washington, DC 20005

(202) 371-1212

ANTONIA HERNANDEZ

E. RICHARD LARSON

Mexican American Legal

Defense and Educational Fund

634 S. Spring Street, 11th Floor

Los Angeles, CA 90014

(213) 629-2512

Attorneys for Amici Curiae

TABLE OF CONTENTS

TABLE OF A U TH O RITIES................................................................................................. ii

ISSUE P R E S E N T E D .............................................................................................................. vi

INTERESTS OF A M IC I...................................................................................................... vii

STATEMENT OF THE CASE ......................................................................................... 1

Statement of the F a c ts .............................................................................................. 1

Course of Proceedings in the District Court and Court of Appeals ............. 3

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT ......................................................................................... 6

ARGUMENT ........................................................................................................................ 7

I. INGRAM’S DISCHARGE OF MR. MCGINNIS ON THE BASIS OF

RACE VIOLATES 42 U.S.C. § 1981............................................... 7

A. The Supreme Court’s Decision in Patterson v. McLean Credit Union

Does Not Preclude Mr. McGinnis’ Section 1981 Discharge Claim . . . 8

B. Ingram’s Racially Motivated Discharge of Mr. McGinnis Violated His

Right to "Make and Enforce Contracts" Free From Racial

Discrimination................................................................................................. 14

C. Congress Intended Section 1981 To Prohibit Racially Discriminatory

Contract T erm ination .................................................................................... 19

CONCLUSION ...................................................................................................................... 20

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES-

CASES

Anderson v. Bessemer City.

470 U.S. 564 (1985) ................................................................................................... 1

Asare v. Svms. Inc..

51 Empl. Prac. Dec. (CCH) (E.D.N.Y. 1989)....................................................... 15

Baylor v. Jefferson Ctv. Bd. of Ed..

733 F.2d 1527 (11th Cir. 1 9 8 4 )............................................................................... 1

Birdwhistle v. Kansas Power and Light Co..

723 F. Supp. 570 (D. Kan. 1989) ......................................................................... 19

Black v. Akron.

831 F.2d 131 (6th Cir. 1987) ............................................................................... 9

Carroll v. Elliott Personnel Services.

51 Fair Empl. Prac. Cas. 1173 (BNA) ............................................................... 14

Comeaux v. Uniroval Chemical Corp..

849 F.2d 191 (5th Cir. 1988) ............................................................................... 9

Edwards v. Jewish Hosp. of St. Louis.

855 F.2d 1345 (8th Cir. 1988) ............................................................................... 9

Foster v. Atchison. Topeka and Santa Fe Railway Co..

1990 U.S.Dist. LEXIS 1338 (D. Kan. Jan. 11, 1990) (attached) .................. 15

Gairola v. Commonwealth of Virginia Dept, of Gen’l Svcs.,

753 F.2d 1281 (4th Cir. 1985) .......................... ................................................... 9

Gamboa v. Washington.

716 F. Supp. 353 (N.D.I11. 1989) ......................................................................... 15

Goodman v. Lukens Steel Co..

482 U.S. 656 (1987) ................................................................................................. 10, 18

Hall v. County of Cook.

719 F. Supp. 721 (N.D.I11. 1989) ......................................................................... 15

li

Hicks v. Brown Group, Inc.,

Civil Action Nos. 88-2769/2817, slip op.

(8th Cir, April 16, 1990) (attached).............................' ................... 11, 12, 13, 15, 20

Jackson v. Albuquerque.

890 F.2d 225 (10th Cir. 1990) ............................................................................... 11

Jett v. Dallas Independent School District.

491 U .S .___, 105 L. Ed. 2d 598 (1989) ............................................................ 9

Johnson v. Railway Express Agency.

421 U.S. 454 (1975) ................................................................................................. 10

Jones v. Pepsi-Cola General Bottlers. Inc..

1989 U.S.Dist. LEXIS 10307

(W.D.Mo. August 29, 1989) (attached) ............................................................... 16

Kelley v. TKY Refractories Co..

860 F.2d 1188 (3d Cir. 1988) ................................................................................. 9

Lavender v. V & B Transmissions and Auto Repair. 1990 U.S.

App. LEXIS 4975 (5th Cir. April 6, 1990) (attached) ....................................... 12, 13

Lytle v. Household Manufacturing. Inc..

58 U.S.L.W. 4341 (Mar. 20, 1990) .................................................................... 9, 10

Malhotra v. Cotter & Co..

885 F.2d 1305 (7th Cir. 1989) ............................................................................... 14, 16

McDonald v. Santa Fe Trail Transportation Co..

427 U.S. 273 (1976) ................................................................................................. 10

McGinnis v. Ingram Equipment Co..

888 F.2d 109 (11th Cir. 1989) ............................................................................... 4, 5

McGinnis v. Ingram Equipment Co.,

685 F. Supp. 224 (N.D. Ala. 1988) ....................................................................... passim

Meade v. Merchants Fast Motorline. Inc..

820 F.2d 1124 (10th Cir. 1 9 8 7 )........... 9

Overby v. Chevron USA. Inc.,

884 F.2d 470 (9th Cir. 1989) ................................................................................. 12, 13

Padilla v. United Air Lines.

716 F. Supp. 485 (D. Colo. 1989) ....................................................................... 14, 16

Patterson v. McLean Credit Union.

491 U .S .___, 105 L. Ed. 2d 132 (1 9 8 9 )............................................................... passim

Patterson v. McLean Credit Union.

805 F.2d 1143 (4th Cir. 1986) ............................................................................... 9

Ramseur v. Chase Manhattan Bank.

865 F.2d 460 (2d Cir. 1989) ................................................................................. 9

Rick Nolan’s Auto Body Shop, Inc, v.

Allstate Insurance Co..

718 F. Supp. 721 (N.D.I11. 1989) ......................................................................... 16

Rowlett v. Annheuser-Busch. Inc..

832 F.2d 194 (1st Cir. 1987) ................................................................................. 9

Sengupta v. Morrison-Knudsen Co.. Inc..

804 F.2d 1072 (9th Cir. 1986) ............................................................................... 9

Sherman v. Burke Contracting. Inc..

891 F.2d 1527 (11th Cir. 1990)............................................................................ 6, 12, 13

St. Francis College v. Al-Khazraii.

481 U.S. 604 (1987) ................................................................................................. 10

Teamsters v. United States.

431 U.S. 324 (1977) ................................................................................................. 17

Vance v. Southern Bell Tel, and Tel. Co.,

863 F.2d 1503 (11th Cir. 1989) ............................................................................ 9

Yarbrough v. Tower Oldsmobile, Inc..

789 F.2d 508 (7th Cir. 1986) ................................................................................. 9

Zaklama v. Mt. Sinai Medical Center.

842 F.2d 291 (11th Cir. 1988) ............................................................................... 9

IV

STATUTES

Fed. R. Civ. P. 52(a) ................................................................................................... 1

42 U.S.C. § 1981 ........................................................................................................... passim

42 U.S.C. § 2000e et seg. (Title VII) ....................................................................... 3, 12

MISCELLANEOUS

Analysis by NAACP Legal Defense Fund on Impact of Supreme

Court’s Decision in Patterson v. McLean Credit Union,

Daily Labor Report (BNA) No. 223,

(November 21, 1989) (attached) ......................................................................... 11

Eisenberg & Schwab, The Importance of Section 1981.

73 Cornell L. Rev. 596 (1988) .............................................................................. 11

Report of the Joint Committee on Reconstruction,

39th Cong., 1st Sess. (1865) ............. ................................................................... 19

v

STATUTES

Fed. R. Civ. P. 52(a) ................................................................................................... 1

42 U.S.C. § 1981 ........................................................................................................... passim

42 U.S.C. § 2000e et seg. (Title VII) ....................................................................... 3, 12

MISCELLANEOUS

Analysis by NAACP Legal Defense Fund on Impact of Supreme

Court’s Decision in Patterson v. McLean Credit Union,

Daily Labor Report (BNA) No. 223,

(November 21, 1989) (attached) ......................................................................... 11

Eisenberg & Schwab, The Importance of Section 1981.

73 Cornell L. Rev. 596 (1988) ............................................................................... 11

Report of the Joint Committee on Reconstruction,

39th Cong., 1st Sess. (1865) ................................................................................. 19

v

ISSUE PRESENTED

Whether Ingram Equipment Company’s discharge of Terrell McGinnis on the basis

of his race violated 42 U.S.C. § 1981.

vi

INTERESTS OF AMICI

The NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc., is a non-profit corporation

formed to assist blacks to secure their constitutional and civil rights by means of litigation.

For many years, attorneys of the Legal Defense Fund have represented parties in litigation

before the United States Supreme Court and the federal courts of appeals and district

courts involving a variety of race discrimination and remedial issues, including questions

involving the proper scope of 42 U.S.C. § 1981 and other federal civil rights laws. The

Legal Defense Fund represented the plaintiff in Patterson v. McLean Credit Union, the

most recent decision of the United States Supreme Court interpreting section 1981. The

Legal Defense Fund believes that its experience in this area of litigation and the research

it has done will assist the Court in this case.

The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) is a nationwide, nonprofit, nonpartisan

organization with over 275,000 members dedicated to the principles of liberty and equality

embodied in the Constitution and our nation’s civil rights laws. The Civil Liberties Union

of Alabama is a state-wide affiliate of the ACLU. The ACLU and its affiliates have

frequently challenged acts of racial discrimination by relying on 42 U.S.C. §1981. Any

decision by this Court addressing the scope of §1981 thus directly affects the ongoing work

and central concerns of the ACLU.

The Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc. (MALDEF),

established in 1967, is a national civil rights organization. Its principal objective is to

secure, through litigation and education, the civil rights of Hispanics living in the United

States. In order to increase equal employment opportunities for Hispanics, MALDEF is

vii

currently pursuing nearly fifty employment discrimination cases. Since many of these cases

include claims under 42 U.S.C. §1981, the judicial construction of this important civil rights

statute will certainly affect the fair employment rights of Hispanics.

The Puerto Rican Legal Defense and Education Fund, Inc. is a national civil rights

organization established in 1972. Its principal objective is to secure, through litigation and

education, the civil rights of Puerto Ricans and other Latinos living in the United States.

Because of the continued discrimination suffered by Puerto Ricans and other Latinos in

contractual relationships, particularly in employment, Puerto Ricans and other Latinos

continue to place extensive reliance on the Civil Rights Act of 1866 to vindicate their civil

rights.

The Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law is a nonprofit organization

established in 1963 at the request of the President of the United States to involve leading

members of the bar throughout the country in the national effort to insure civil rights to

all Americans. For the past 27 years, it has represented, and assisted other lawyers in

representing, numerous persons in administrative proceedings and lawsuits under Title VII

and 42 U.S.C. § 1981 throughout the country, including before the Court of Appeals for

the Eleventh Circuit. The Lawyers’ Committee has also represented parties and

participated as an amicus in many § 1981 cases before the Supreme Court and the Courts

of Appeals, including Patterson v. McLean Credit Union.

The parties have consented to the filing of this brief and letters of consent are filed

herewith.

vm

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

This case is before the Court for rehearing en banc of the panel’s decision to vacate

and remand Mr. McGinnis’ section 1981 damages award in light of Patterson v. McLean

Credit Union. The parties disagree whether the district court made clearly erroneous

findings of fact, whether Patterson should be applied to this case, and whether, if applied,

Patterson bars plaintiffs claims of discriminatory terms of employment, denial of

promotion, demotion, and discharge. Amici address here only the question whether, if

applied, Patterson precludes Mr. McGinnis from recovering for his discriminatory

discharge. We conclude that it does not.1

Statement of the Facts

H.D. Ingram, manager and owner of Ingram Equipment Company ("Ingram," "the

Company"), harshly mistreated his only black employee, Terrell McGinnis, on the basis of

his race for four and a half years, and then fired Mr. McGinnis on racial grounds. Mr.

McGinnis "suffered many more racial indignities at the hands of the Company than any

one citizen should be called upon to bear in a lifetime." McGinnis v. Ingram Equipment

Co.. 685 F. Supp. 224, 228 (N.D. Ala. 1988).2

^In presenting this question, amici do not endorse the panel majority’s decision that

Ingram has not waived defenses based on Patterson, nor do we express any opinion on

Mr. McGinnis’ other section 1981 claims.

2This Court must accept the facts as found by the district court unless they are shown

to be clearly erroneous. Fed. R. Civ. P. 52(a); Anderson v. Bessemer City. 470 U.S. 564

(1985); Bavlor v. Jefferson Ctv. Bd. of Ed.. 733 F.2d 1527, 1532 (11th Cir. 1984). Ingram

argues that the district court’s findings of fact should be reversed, but its analysis of the

findings in light of the record evidence at best shows that the factual issues were disputed

at trial, not that the findings are erroneous or unsupported by the evidence that the

1

Mr. McGinnis was hired as a mechanic helper for the Company, which refurbishes

and sells garbage trucks, but because Mr. McGinnis is black, Ingram used him as a "janitor

and general flunky." Id- at 225. Mr. Ingram repeatedly called Mr. McGinnis "nigger," or

"black s-o-b." Id. at 225-26. When he found fault with Mr. McGinnis, he often lashed out

violently, brutally kicking Mr. McGinnis to the point where the pain and swelling required

medical attention, and threatening him with a gun. Id. at 226. Although the Company

expanded quickly and many people were hired during Mr. McGinnis’ tenure there, Ingram

refused to consider black applicants for employment. Id. at 227?

In March of 1986, when Mr. McGinnis returned late from making an unavoidably

delayed delivery of some equipment, Mr. Ingram accosted him and pointed a gun to his

head, using racial epithets and threatening Mr. McGinnis until he threw up his hands in

fear and said "Yes sir, yes sir." Id. at 226. When Mr. Ingram asked him to run another

errand a couple of days later, Mr. McGinnis protested that he was hired as a mechanic

helper rather than a truck driver, but performed as Mr. Ingram directed him. Id at 226.

Upon Mr. McGinnis’ return from the errand, Ingram suspended him for having displayed

a "bad attitude" and ostensibly abusing the company truck. Id. at 226-27. Two days later,

when Mr. McGinnis came back to work after the suspension, Ingram fired him for the

district judge credited. See infra note 3.

■^Testimony at trial showed that Ingram hired Mr. McGinnis because Mr. Ingram

believed that if he had a black employee, the Company would be more likely to be

perceived as an equal opportunity employer eligible for contracts with the City of

Birmingham. (Tr. 40-41, 43).

2

same reasons. Id. at 227. Mr. Ingram then fabricated false "Report[s] of Work Incidents"

and placed them in Mr. McGinnis’ personnel file. Id. But for Ingram’s discrimination,

Mr. McGinnis would have remained shop foreman at the company. ]&*

Course of Proceedings in the District Court and Court of Appeals

Plaintiff sued under 42 U.S.C. § 1981 (section 1981) and 42 U.S.C. § 2000e et seq.

(Title VII). The district court held Ingram liable under section 1981 for discrimination in

the terms and conditions of Mr. McGinnis’ employment, and for discriminatory discharge.

Id. at 224, 227, 228. The court awarded $156,164.41 in damages, and permanently

enjoined Ingram from discriminating. The court dismissed the Title VII claim because the

statute does not apply to businesses such as Ingram which do not employ at least fifteen

workers. Id. at 224 n.l.

4 Notwithstanding defendant’s challenge to the district court’s factual findings,

defendant concedes that there was testimony that Mr. Ingram "called him nigger twice on

the day McGinnis was discharged." Appellant’s En Banc Brief at 9. Defendant purports

to explain this away by stating that it was said "in anger over the circumstances that had

just occurred," and protests that all other times Mr. Ingram called Mr. McGinnis "nigger"

were behind Mr. McGinnis’ back. Id. Defendant also challenges the district court’s

finding that Mr. McGinnis alone had to clean the bathrooms. Defendant admits, however,

that Mr. McGinnis "may have cleaned the restroom more" than other employees, but

insists that others, too, had to clean them on occasion. Id. at 7. Defendant contends that

the judge’s findings with respect to Mr. Ingram’s use of a gun are erroneous as well, yet

concedes that "[t]he trial testimony was that the gun was pulled on one occasion." Id at

8.

The differences that defendant points to are conflicts in testimony that the district

judge resolved in plaintiffs favor, and which this Court cannot now disturb. Even if

defendant’s view of the facts were relevant at this stage, however, Ingram’s version would

nonetheless support the district court’s conclusion that the company discriminated. It is

hardly a material distinction whether Ingram called Mr. McGinnis racist names and pointed

a loaded gun at him few times or many, and whether white employees on occasion also

performed some of the menial tasks that were routinely assigned to Mr. McGinnis.

3

Ingram appealed, attacking the district court’s factual findings of discrimination, and

arguing that the district court had "impermissibly interjected itself into the proceedings in

favor of McGinnis." Appellant’s Initial Brief, at 9 (Statement of the Issues). At oral

argument of the appeal, Ingram for the first time urged the Court to reverse on the basis

of the decision of the United States Supreme Court in Patterson v. McLean Credit Union,

491 U .S .___, 105 L. Ed. 2d 132 (1989).

In Patterson, the Supreme Court held that 42 U.S.C. § 1981 did not apply to a claim

of racial harassment on the job. 105 L. Ed. 2d at 151-53. The Court confirmed, however,

that racial discrimination in the formation of contracts is still actionable under section

1981, jd. at 150-151, and that discrimination in certain promotions remains actionable as

well. Id. at 156. The opinion did not address whether section 1981 continues to prohibit

discriminatory termination of a contract.

After oral argument, the appellate panel requested further briefing in light of

Patterson, and reversed the district court’s decision and remanded the case for further

analysis pursuant to Patterson. McGinnis v. Ingram Equipment Co.. 888 F.2d 109, 111

(11th Cir. 1989) (per curiam). The majority held that although Ingram had not raised its

defense based on Patterson until oral argument, it was not too late because the defense

was jurisdictional and therefore not subject to waiver. Id. The majority suggested that

[bjecause claims of harassment and discriminatory work conditions are no

longer actionable under section 1981, the district court should have the

opportunity to reconsider its judgment and award of damages. . . . In

particular, the district judge should determine whether any promotion

opportunity "rises to the level of an opportunity for a new and distinct relation

between the employer and the employee. . . ."

4

Id- The panel opinion did not comment on the portion of the district court’s award that

was based on its finding of discriminatory discharge.

Judge Cox, in dissent, contended that Patterson should not be applied to this case

because section 1981 is not a jurisdictional statute and the Patterson decision construing

it did not involve jurisdictional issues. Any potential defense based on the scope of

section 1981 arises under Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 12(b)(6), and therefore was

waived when it was not preserved in the district court nor properly raised in the court of

appeals. Id. at 111-12.

Mr. McGinnis suggested rehearing en banc. The full Court granted rehearing on

February 6, 1990.

5

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

Ingram Equipment Company’s discriminatory termination of Mr. McGinnis’

employment contract violated his right under 42 U.S.C. § 1981 "to make and enforce

contracts" on racially neutral terms, because by firing Mr. McGinnis, Ingram refused on

racial grounds to engage in a contractual relationship with him. The district court’s award

of damages to Mr. McGinnis for racially discriminatory discharge should be affirmed

notwithstanding the decision of the Supreme Court in Patterson v. McLean Credit Union.

105 L. Ed. 2d 132 (1989). Patterson did not address whether section 1981 prohibits

discriminatory discharge, and the decision in Sherman v. Burke Contracting. Inc.. 891 F.2d

1527, 1534 (11th Cir. 1990) (per curiam), construing Patterson as barring all claims "based

on post-contractual events," including discharge claims, is erroneous and should be

reversed. Affording no section 1981 rights to employees discharged on racial grounds,

in contrast to applicants turned away at the outset for the same reasons, would be

anomalous and would permit subversion of all section 1981 contract rights. The Supreme

Court in Patterson explicitly held that employers are barred by section 1981 from

discriminating in hiring: if they may lawfully fire employees because of race, they can

discriminate in hiring merely by hiring all qualified applicants and then discharging their

black employees. The section 1981 right to "make" contracts should be interpreted as a

right to have a contractual relationship, not merely to enter into one. The 1866 Congress

that enacted section 1981 clearly intended the law to be so construed, and any other

reading of section 1981 would produce illogical and unjust results.

6

ARGUMENT

I. INGRAM’S DISCHARGE OF MR. MCGINNIS ON THE

BASIS OF RACE VIOLATES 42 U.S.C. § 1981

The district court found that Ingram fired Mr. McGinnis for racially discriminatory

reasons, and rejected Ingram’s work-related defense as pretextual. On the basis of the

district court’s finding that Ingram fired Mr. McGinnis for discriminatory reasons, that

court’s decision with respect to Mr. McGinnis’ discharge should be affirmed. Immediately

preceding Mr. McGinnis’ discharge, Mr. Ingram repeatedly used racial slurs and

threatened Mr. McGinnis with a gun. When Mr. McGinnis protested Mr. Ingram’s

directions that he run errands on the ground that he was hired to work as a mechanic,

Mr. Ingram accused Mr. McGinnis of insubordination, suspended him for two days, and

then fired him. Ingram placed fraudulent Reports of negative work performance in Mr.

McGinnis’ personnel file in an attempt to justify the discharge. 685 F. Supp. at 227.

Ingram replaced Mr. McGinnis with a white male. In the absence of racial discrimination,

Mr. McGinnis would have continued to work as shop foreman for Ingram.

Ingram’s conduct violates section 1981 as that statute has long been interpreted prior

to Patterson.-* Patterson did not address section 1981’s applicability to claims of racially

Section 1981 states:

All persons within the jurisdiction of the United States shall have the same

right in every State and Territory to make and enforce contracts, to sue, be

parties, give evidence, and to the full and equal benefit of all laws and

proceedings for the security of persons and property as is enjoyed by white

citizens, and shall be subject to like punishment, pains, penalties, taxes, licenses,

and exactions of every kind, and to no other.

7

motivated discharge. Because section 1981 is properly construed according to its language,

logic, purpose, and history as prohibiting discriminatory discharge, the district court’s

discharge holding should stand.

A. The Supreme Court’s Decision in Patterson v. McLean Credit

Union Does Not Preclude Mr. McGinnis’ Section 1981 Discharge

Claim

The Supreme Court and courts of appeals have consistently interpreted section 1981

to prohibit termination of a contract on the basis of race. This aspect of section 1981’s

coverage was not before the Supreme Court in Patterson, and the Patterson decision did

not disturb it. The Supreme Court in Patterson decided only that section 1981 does not

prohibit harassment on the basis of race. No claim of discriminatory discharge was before

the Supreme Court.6

In affirming the decision of the Fourth Circuit with respect to racial harassment

claims, the Supreme Court never questioned the common-sense distinction the Circuit

court drew between termination and harassment claims. The court of appeals contrasted

"[c]laims of racially discriminatory hiring, firing, and promotion," with racial harassment

claims on the ground that the former "go to the very existence and nature of the

employment contract and thus fall easily within § 1981’s protection." Patterson v. McLean

6Justice Brennan, in his separate opinion in Patterson, asserted that the 39th Congress

intended section 1981 "to go beyond protecting the freedmen from refusals to contract . . .

and from discriminatory decisions to discharge" to reach racial harassment as well. 105

L. Ed. 2d at 169. Although the majority expressly disagreed with Brennan’s view regarding

harassment, it conspicuously avoided any comment about discharges.

8

Credit Union, 805 F.2d 1143, 1145 (4th Cir. 1986). On the basis of the Fourth Circuit’s

reasoning in Patterson, this Court in Vance v. Southern Bell Tel, and Tel. Co.. 863 F.2d

1503 (11th Cir. 1989), confirmed that a constructive discharge "impair[ed] [plaintiffs]

ability to make and enforce her employment contract," and was therefore actionable under

section 1981. Id. at 1509 n. 3.7

The Supreme Court has subsequently verified that its decision in Patterson does not

bar section 1981 claims of discriminatory contract termination. A week after the Court

decided Patterson, it "assumefd], without deciding," that an employee’s section 1981 rights

were violated by his removal from his job for allegedly racial reasons. Jett v. Dallas

Independent School District. 491 U .S .___, 105 L. Ed. 2d 598, 611 (1989). The Patterson

majority joined the opinion in Jett. Nine months later, in a unanimous decision in Lytle

v. Household Manufacturing. Inc., 58 U.S.L.W. 4341 (Mar. 20, 1990), the Court stated that

Patterson had not foreclosed discriminatory discharge claims, and remanded the case to

give the Fourth Circuit an opportunity to consider the issue. Id. at 4343, n. 3 (majority

opinion); id. at 4344 (opinion of O’Connor, J., concurring) (commenting that "the question

7Prior to Patterson, the Courts of Appeals, including this Court, were unanimous in

the view that section 1981 forbids racially motivated contract termination. See, e.g.,

Zaklama v. Mt. Sinai Medical Center, 842 F.2d 291, 293 and n. 1 (11th Cir. 1988); see,

also. Rowlett v. Annheuser-Busch, Inc.. 832 F.2d 194 (1st Cir. 1987); Ramseur v. Chase

Manhattan Bank, 865 F.2d 460 (2d Cir. 1989); Kelley v. TKY Refractories Co.. 860 F.2d

1188 (3d Cir. 1988); Gairola v. Commonwealth of Virginia Dept, of Gen’l Svcs., 753 F.2d

1281 (4th Cir. 1985); Comeaux v. Uniroyal Chemical Corp., 849 F.2d 191 (5th Cir. 1988);

Black v. Akron, 831 F.2d 131 (6th Cir. 1987); Yarbrough v. Tower Oldsmobile, Inc., 789

F.2d 508 (7th Cir. 1986); Edwards v. Jewish Hosp. of St, Louis. 855 F.2d 1345 (8th Cir.

1988); Sengupta v. Morrison-Knudsen Co., Inc., 804 F.2d 1072 (9th Cir. 1986); Meade v.

Merchants Fast Motorline. Inc.. 820 F.2d 1124 (10th Cir. 1987).

9

whether petitioner has stated a valid claim under § 1981 remains open").

Prior to Patterson, the Supreme Court had consistently applied section 1981 to

prohibit racially motivated contract termination. In Johnson v. Railway Express Agency.

421 U.S. 454, 459-60 (1975), the Court upheld the right of a black railway driver to sue

o

his former employer for race discrimination, including discharge on the basis of race. In

McDonald v. Santa Fe Trail Transportation Co.. 427 U.S. 273, 275 (1976), the Court

applied section 1981 to white workers’ claims that their discharge for theft was motivated

by racial discrimination. In St. Francis College v. Al-Khazraii. 481 U.S. 604, 606 (1987),

a unanimous Court held that an Arab college professor could sue under section 1981 for

having been denied tenure and forced out of his job. And in Goodman v. Lukens Steel

Co.. 482 U.S. 656, 659-60 (1987), the Court upheld application of a two-year statute of

limitations to section 1981 challenges to discriminatory employment practices, including

discharges. In the absence of a holding from the Supreme Court that discriminatory

discharge claims are no longer covered, this Court should not ignore the long line of

Supreme Court precedent on the most important right section 1981 confers.9 Patterson’s

o

The Court in Johnson commented that section 1981 is not coextensive with title VII

insofar as title VII is applicable only to certain employers, and section 1981 does not

provide for assistance with such matters as investigation and conciliation of claims. Id. at

460. Patterson clearly reversed Johnson to the extent that harassment claims, while

actionable under title VII, can no longer be brought under section 1981. Except as

specifically reversed by Patterson, however, Johnson remains the law.

9 Although section 1981 prohibits discrimination in the making and enforcement of all

kinds of contracts, and bans discrimination in other areas as well, the statute is most

frequently used in the employment context to redress discriminatory discharge. See

generally Eisenberg & Schwab, The Importance of Section 1981. 73 Cornell L. Rev. 596,

599-601 (1988), cited in Hicks, slip op. at 15. Among section 1981 claims dismissed by

10

own emphasis on the weight of stare decisis requires as much. See Patterson. 105 L. Ed.

2d at 147-50.

Since the Supreme Court’s decision in Patterson, the courts of appeals have divided

over whether the Supreme Court’s reasoning in that case should be extended to bar

section 1981 claims of discriminatory discharge. The Eighth Circuit is the only appellate

court to have analyzed the issue in detail. In Hicks v. Brown Group. Inc.. Civil Action

Nos. 88-2769/2817, slip op. (8th Cir, April 16, 1990) (attached), a reverse discrimination

case brought by a discharged white employee, the court held that section 1981 still covers

discriminatory contract termination. In light of the scope and purpose of Patterson, as

well as the language and logic of the statute and the Congressional intent behind it, the

Eighth Circuit rejected the argument that Patterson precludes section 1981 claims of

discriminatory discharge/0

The court in Hicks decided that Patterson’s reasoning does not apply to discharge

claims: "postformation discharge continues to be actionable under the right to make

contracts when it totally deprives the victim of the fundamental benefit the right to make

contracts was intended to secure -- the contractual relationship itself." Id- at 19.

lower courts since Patterson, the largest category is claims of discriminatory discharge. See

Analysis by NAACP Legal Defense Fund on Impact of Supreme Court’s Decision in

Patterson v. McLean Credit Union. Daily Labor Report (BNA) No. 223, at D-2

(November 21, 1989) (attached).

10 See also Jackson v. Albuquerque. 890 F.2d 225, 236 n. 15 (10th Cir. 1990)

(holding that the decision in Patterson ”do[es] not affect either the analysis or the outcome

of this [section 1981 discriminatory discharge] case").

11

Discharge is thus distinct from harassment, which Patterson held is not actionable, because

"[a]n employee who is harassed still receives the fundamental benefit of his or her

employment contract," whereas discharge "completely deprives the employee of his or her

employment, the very essence of the right to make employment contracts." Id- at 16-

11.11 Hicks is by far the most extensive and well reasoned opinion on the application of

section 1981 to discharges after Patterson, and offers substantial guidance to this Court.

Some Circuit courts prior to Hicks, however, including a panel of this Court, read

Patterson broadly to bar discharge claims. See Sherman v. Burke Contracting. Inc,. 891

F.2d 1527 (11th Cir. 1990) (per curiam): Lavender v. V & B Transmissions and Auto

Repair. 1990 U.S. App. LEXIS 4975 (5th Cir. April 6, 1990) (attached) ; Overby v.

Chevron USA. Inc.. 884 F.2d 470 (9th Cir. 1989). These holdings depend exclusively on

the dictum in Patterson that the right to make contracts "extends only to the formation

of a contract, but not to problems that may arise later from the conditions of continuing

employment." 105 L. Ed. 2d at 150. In Sherman, a panel of this Court raised the

discharge issue sua sponte. without benefit of briefing or argument on the point. It

determined that after Patterson, "suits based on post-contractual events cannot be brought

under section 1981," 891 F.2d at 1534, and accordingly concluded that the plaintiffs claim

of retaliatory discharge was no longer covered. To the extent that the panel in Sherman

11 Hicks correctly points out that application of section 1981 to discriminatory

discharge will not undermine the Title VII procedures for mediation and conciliation,

which were a major concern of the Supreme Court in Patterson. See 105 L. Ed. 2d at

154 and n.4. Procedures for conciliation are helpful in the context of an ongoing

employment relationship in a way that they cannot be after discharge, where "there is no

longer an employment relationship to salvage." Hicks, slip op. at 20.

12

read Patterson broadly to preclude all section 1981 claims based on conduct occurring

after the formation of an initial contract between the parties — including Mr. McGinnis’

claim that Ingram fired him because he is black — it was wrongly decided and should be

reversed.72

Contrary to Sherman’s analysis, the Supreme Court did not hold that everything that

happens after the contract-formation stage is not actionable. For example, the Supreme

Court remanded Patterson on the ground that some discriminatory promotion denials

remain actionable under section 1981 even though denial of promotion, like termination,

occurs after the employment contract is formed. Both discriminatory refusal to promote

and discriminatory termination relate to the making of a contract, which Patterson held

is still covered by section 1981, 105 L.Ed.2d. at 150, rather than to the "conditions of

continuing employment" that Patterson held are no longer covered. Id. at 150-51. As the

continued vitality of some section 1981 discriminatory-promotion claims shows, see.

12 The Fifth and Ninth Circuits relied on the same rationale invoked in Sherman

to hold that section 1981 no longer covers contract termination. In Lavender, the Fifth

Circuit affirmed the district court’s dismissal of the section 1981 claims of two white males

who alleged that the defendant, a minority-owned business, discharged them on the basis

of their race. The court concluded that "[b]ecause the contract here was already

established, the termination amounted to postformation conduct. As such, it is not

actionable under section 1981." 1990 U.S. App. Lexis 4975, at *9.

The plaintiff in Overby contended that he was fired for refusing to allow his

employer to search his person and wallet where the search was allegedly in retaliation

against plaintiff for having questioned corporate practices on issues of race and employee

privacy. The court affirmed the dismissal of plaintiffs "opaque" section 1981 claim on the

ground that "Overby does not claim that Chevron prevented him from entering into a

contract. . . . Rather, he complains of post formation conduct: retaliatory discharge.

Overby’s right ’to make’ a contract is therefore not implicated." 884 F.2d at 473.

13

Malhotra v. Cotter & Co., 885 F.2d 1305, 1311 (7th Cir. 1989), Patterson does not

immunize defendants from section 1981 discrimination claims merely because one contract

has been formed.

B. Ingram’s Racially Motivated Discharge of Mr. McGinnis Violated

His Right to "Make and Enforce Contracts" Free From Racial

Discrimination

The section 1981 right "to make and enforce" contracts on racially neutral terms

includes a right to be free from discriminatory discharge. Discriminatory termination of

a contract relates to the employer’s willingness to engage in or "make" contracts, rather

than to the conditions of continuing employment. Consistent with this reasoning, several

t

courts have held that Patterson does not affect sectiofi 1981’s prohibition on racially

motivated discharge. The Eighth Circuit in Hicks held that "protection from racially

motivated deprivations of contracts is essential to the full enjoyment of the right to make

contracts." Slip op. at 16. In Carroll v. Elliott Personnel Services. 51 Fair Empl. Prac.

Cas. 1173 (BNA) (D. Md. 1989), the court denied defendant’s motion to dismiss plaintiffs

claim of discriminatory discharge because the "claim of racially discriminatory firing went

to the very existence and nature of an employment contract and thus fell easily within §

1981’s protection." In Padilla v. United Air Lines. 716 F. Supp. 485, 490 (D. Colo. 1989),

the court similarly held in light of Patterson that "termination is part of the making of a

contract. A person who is terminated because of his race, like one who was denied an

employment contract because of his race, is without a job. Termination affects the

existence of the contract, not merely the terms of its performance." In Asare v. Svms,

14

Inc.. 51 Empl. Prac. Dec. (CCH) H 39,437 (E.D.N.Y. 1989), the court sustained a claim

of racially motivated termination, explaining that:

During section 1981’s long history it has never been seriously contended that

its prohibition against racially discriminatory employment practices does not

embrace racially motivated dismissals such as those alleged here. . . . This is

because claims of racially motivated discharge go to the very existence of the

employment contract . . . and thus fall naturally within the statute’s protection

of the right to contract.

Id. at 39,438 (citations om itted)/5

Termination is akin to refusal to contract, because, where work is available, the

discharge of an employee is legally indistinguishable from a refusal to continue to employ

him. If a black mechanic helper who had never worked at Ingram applied to work there

in March, 1986 on the day Mr, McGinnis was discharged, and was turned away because

I

Ingram discriminates against blacks, he would have a section 1981 claim for discriminatory

refusal to hire. If Mr. McGinnis himself upon his discharge asked to be rehired, and were

rejected on racial grounds, he would by the same token have a section 1981 claim of

discriminatory refusal to hire. See Jones v. Pepsi-Cola General Bottlers. Inc.. 1989

U.S.Dist. LEXIS 10307 (W.D.Mo. August 29, 1989) (attached) (stating that, where plaintiff

requests a new job upon his discharge, defendant violates section 1981 "in refusing on the

u See also. Foster v. Atchison. Topeka and Santa Fe Railway Co.. 1990

U.S.Dist. LEXIS 1338 (D. Kan. Jan. 11, 1990) (attached) ; Gamboa v. Washington. 716

F. Supp. 353, 358, 359 (N.D.I11. 1989) (plaintiff who alleged he was "transferred, demoted

and disciplined because he is Hispanic" could sue under section 1981, while he "cannot

recover for discipline or harassment not amounting to a demotion or a constructive

discharge"). But see e.g.. Hall v. County of Cook. 719 F. Supp. 721, 723 (N.D.I11. 1989)

(dismissing plaintiffs claim of discriminatory contract termination on the ground that,

under Patterson, "once an individual has secured employment, the statute’s protection of

the right to make a contract is at an end").

15

basis of race to make a new contract"); cf. Malhotra v. Cotter, 885 F.2d 1305, 1311 (7th

Cir. 1989) (interpreting section 1981 to cover all promotions where a stranger to the firm

would be eligible for the position at issue in order to avoid anomaly of stranger who is not

hired having greater rights than employee who is denied promotion to same position)/'*

Firing on the basis of race constitutes a refusal from that time forward to engage in

contractual relations with that particular employee. Thus, when an employer ends an

employment contract, it also constructively refuses to enter into another employment

contract with that employee. Cf. Padilla. 716 F. Supp. at 490 n.4 (noting that employer’s

assignment of "Ineligible for Rehire" status to terminated employee was actionable

discrimination in the "making of contracts").

t

The district court found not only that Ingram specifically refused on the basis of Mr.

McGinnis’ race to continue to engage in a contractual relationship with him, but also that

Ingram had a policy of refusing to make employment contracts with blacks. Thus, it is

clear from the court’s opinion that Ingram would not have re-contracted with Mr.

McGinnis on racially neutral terms. The fact that Mr. McGinnis did not make a futile

request to be re-hired after he was fired for overtly racist reasons does not negate the fact

14 But see Rick Nolan’s Auto Body Shop. Inc, v. Allstate Insurance Co.. 718 F.

Supp. 721, 722 (N.D.I11. 1989), in which the court rejected as "disingenuous" the allegation

that defendant violated section 1981 in refusing to re-contract with plaintiff after

termination of prior contract. The court interpreted section 1981 to prohibit discrimination

only once, in the formation of the first contract between a given set of parties. Even if

those parties conclude their first contract and later initiate another, under the holding in

this case the second contract, and any subsequent ones, would not be subject to section

1981 scrutiny even for formation-stage discrimination, the precise discrimination that

Patterson held was covered by section 1981.

16

that a discriminatory discharge amounts to a refusal to enter into a racially neutral

contract of employment. Cf. Teamsters v. United States. 431 U.S. 324, 363-64 (1977)

(holding that plaintiffs claiming discriminatory denial of transfers and promotions need not

have actually applied for the positions at issue if discriminatory practices deterred them

from doing so).ls

Construing section 1981 to bar discharge claims would completely undermine the

contracts clause of section 1981. An employer unwilling to have members of a certain

race or ethnic group in its work force could subvert section 1981 not by refusing to hire,

which would leave the employer vulnerable to section 1981 claims, but by hiring and then

firing the unwanted employees. Similarly, if a new manager who had a policy against

employing members of racial minorities entered a company that had minority staff

members, the new manager could fire them all on racial grounds with impunity. In order

to protect section 1981 rights "to make and enforce contracts," section 1981 must be

construed to cover all racially motivated refusals of race to contract, regardless of the

particular means through which they are achieved.

n Ingram’s discharge of Mr. McGinnis also violates his section 1981 right to

make contracts free from discrimination because it resulted from the discriminatory terms

of the parties’ initial contract. Although Mr. Ingram hired Mr. McGinnis as a mechanic

helper, he consistently treated him as a menial laborer, assigning him the dirtiest and most

degrading tasks. It was Mr. Ingram’s insistence that Mr. McGinnis perform in the

degraded role that Mr. Ingram hired him, Ingram’s apparent dissatisfaction with that

performance, and McGinnis’ protest against the work he was improperly assigned that led

to Mr. McGinnis’ discharge. Where, as here, "the employer, at the time of the formation

of the contract, in fact intentionally refused to enter into a contract with the employee on

racially neutral terms," Patterson. 105 L. Ed. 2d at 155, the employer has violated section

1981.

17

Mr. McGinnis’s discharge also violated his right to enforce his employment contract,

because Mr. Ingram fired him for attempting to enforce his contractual right to work as

a mechanic — the job for which he was hired - rather than as a driver and general flunky

to run every errand and clean any mess at Mr. Ingram’s bidding. See 685 F. Supp. at 226.

As the Supreme Court reaffirmed in Patterson, the section 1981 right to enforce contracts

is impaired by even "wholly private efforts" to "obstruct nonjudicial methods of adjudicating

disputes about the binding force of obligations." 105 L. Ed. 2d at 151, (emphasis in

original deleted), citing with approval Goodman v. Lukens Steel Co.. 482 U.S. 656. Mr.

McGinnis had a dispute with Mr. Ingram regarding the binding force of Mr. McGinnis’

employment contract to work for Ingram as a mechanic helper. He attempted to enforce

the terms of his employment contract through the only "nonjudicial method" available to

him: informal, one-on-one negotiation with his employer/6 Yet his initial effort to raise

the issue of the scope of his job description met with retaliatory suspension and discharge.

685 F. Supp. at 226-27. Retaliation against an employee for attempting to enforce his

contract rights, whether through a union as in Goodman or without the assistance of a

formal representative, as in this case, violates section 1981 as construed in Patterson/ 7

10 Mr. McGinnis was not represented by any labor union, nor was his dispute

with Ingram within the jurisdiction of the EEOC or other formal, non-judicial body.

17 See Birdwhistle v. Kansas Power and Light Co.. 723 F. Supp. 570, 575 (D.

Kan. 1989) (holding that "discharge is directly related to contract enforcement and thus

is still actionable under section 1981 in light of Patterson"!.

18

C. Congress Intended Section 1981 To Prohibit Racially

Discriminatory Contract Termination

The legislative history of section 1981 makes clear that Congress intended the law

to prohibit racially motivated discharge. Section 1981 was passed during Reconstruction,

when plantation owners who employed freed slaves attempted to reintroduce slavery in

practice by ignoring the contract rights of their new employees. The hearings of the Joint

Committee on Reconstruction, which investigated conditions in the South and provided the

factual foundations for section 1981, were replete with references to discriminatory

discharges of black workers. For example, when plantation owners determined they no

longer had use for their black workers, they drove them off the plantations by the

thousands without paying them. See Report of the Joint Committee on Reconstruction,

39th Cong., 1st Sess. (1865), pt. ii, at 52, 188, 222, 225, 226, 228; pt. iii, at 142, 173-74; pt.

iv, at 64, 66, 68. Such illegal firing often bore more harshly on the freed slaves than

imposition of unequal employment terms on workers when they were hired. Congress was

aware of that particular hardship, and enacted the Civil Rights Act of 1866 to redress it.

Id- See Hicks, slip op. at 23-37 (extensively discussing legislative background of section

1981). As the Supreme Court itself stated in Patterson:

Neither our words nor our decisions should be read as signaling one inch of

retreat from Congress’ policy to forbid discrimination in the private, as well as

the public sphere.

This Court should not negate Congress’ clear intent that section 1981 extend to claims of

racially motivated discharges, nor should it stray from the long history of application of the

statute to reach a result that is at odds with the Supreme Court’s own admonition.

19

CONCLUSION

For the reasons stated in the foregoing Brief of Amici Curiae, this Court should

affirm the district court’s holding that Ingram discharged Mr. McGinnis on the basis of his

race in violation of 42 U.S.C. § 1981.

Respectfully submitted,

CORNELIA T.L. PILLARD

NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street

Suite 1600

New York, NY 10013

(212) 219-1900

Attorneys for Amicus Curiae

NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc.

JOHN A. POWELL

STEVEN R. SHAPIRO

American Civil Liberties

Union Foundation

132 West 43rd Street

New York, NY 10036

(212) 944-9800

Attorneys for Amici Curiae

American Civil Liberties Union

and Civil Liberties Union of

Alabama

20

ANTONIA HERNANDEZ

E. RICHARD LARSON

Mexican American Legal Defense

and Educational Fund

634 South Spring Street

11th Floor

Los Angeles, CA 90014

Attorneys for Amicus Curiae

Mexican American Legal Defense

and Educational Fund

RUBEN FRANCO

KENNETH KIMERLING

Puerto Rican Legal Defense and

Education Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street

Suite 1400

New York, NY 10013

Attorneys for Amicus Curiae

Puerto Rican Legal Defense

and Education Fund, Inc.

BARBARA R. ARNWINE

RICHARD T. SEYMOUR

STEPHEN L. SPITZ

Lawyers’ Committee for

Civil Rights Under Law

1400 Eye Street, N.W.

Suite 400

Washington, DC 20005

(202) 371-1212

Attorneys for Amicus Curiae

Lawyers’ Committee for

Civil Rights Under Law

Dated: New York, New York

April 20, 1990

21

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

This will certify that I have this date served counsel

for both parties in this action with true and correct copies of

the foregoing Brief of NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund,

Inc., American Civil Liberties Union, Civil Liberties Union of

Alabama, Mexican American Legal Defense and Education Fund,

Puerto Rican Legal Defense and Education Fund, Inc., and Lawyers'

Committee for Civil Rights Under Law as Amici Curiae In Support

of Plaintiff-Appellee Terrell McGinnis, by placing the copies in

New York, First Class postage thereon

follows: &

& Childs

day of April, 1990 at New York, New

the U.S. Mail at New York,

fully prepaid addressed as

A. Eric Johnston, Esq.

Hayes D. Brown

Seier, Johnston and Trippe

2100 Southbridge Parkway

Suite 376

Birmingham, AL 35209

Mr. Robert L. Wiggins. Jr.

Gordon, Silberman, Wiggins

Suite Two

100 Washington Street

Huntsville, Alabama 35801

Executed this

York.

UNPUBLISHED SLIP OPINIONS

United States Court of Appeals

F O R T H E E I G H T H C I R C U I T

NOS. 88—2769/2817

Kenneth G. Hicks,

Appellee/cross-appellant,

v.

Brown Group, Inc., d/b/a Brown Shoe Company, Inc.,

Appellant/cross-appellee.

*

*

★

* Appeals from the United States

* District Court for the* Eastern District of Missouri

*

*

*

Submitted: September 13, 1989

Filed: April 16, 1990

Before McMILLIAN, Circuit Judge, HEANEY, Senior Circuit Judge

and FAGG, Circuit Judge.

McMILLIAN, C i rcu it Judge.

Brown Group, Inc., d/b/a Brown shoe Company, Inc. (Brown

Group) , appeals from a final judgment entered by the United States

District court’ for the Eastern District of Missouri upon a jury

verdict finding that it violated 42 U.S.C. § 1981 (1982) (Section

1981) , by discharging Kenneth G. Hicks (Hicks) on the basis

race. The jury found that Hicks was entitled to no actual damages,

but awarded him $10,000 in punitive damages on the ground that

Brown Group's action was willful. The district court modified the

actual damages to $1.00 and awarded Hicks attorneys' fees and

’The Honorable David D. Noce, United st£ * s * * £ * “ £ * 5o? District of Missouri, to whom the matter was rererrea

trial and entry of judgment by consent of the parties pursuan

28 U.S.C. § 636(c) (1982 & Supp. V 1987).

costs. On appeal, Brown— Group raises four major issues for

reversal: (1) the judgment cannot stand because discriminatory dis

charge is not cognizable under Section 1981; (2) the district court

erred in denying its motion for a judgment notwithstanding the

verdict (JNOV) because the jury's finding of discrimination was

clearly erroneous and not supported by sufficient evidence; (3) the

district court erred in submitting jury instructions and special

interrogatories which permitted the jury to find a Section 1981

violation without proof of intentional discrimination; and (4) the

district court erred in denying its motion for a JNOV on the

punitive damages award. Brown Group also claims that the punitive

damage award was not supported by sufficient evidence. On cross

appeal, Hicks alleges that the district court erred in denying his

post-trial motion for reinstatement and related equitable relief

after he had successfully proven that he would not have been

discharged except for his race. For the reasons discussed below,

we affirm the judgment of the district court.

h

I. Facts

Brown Group is a New York corporation engaged in the business

of manufacturing and selling shoes.2 In the early 1970s, Brown

Group owned and operated approximately 35 manufacturing plants

located in Missouri, Illinois, Tennessee, Kentucky and Arkansas.

Until the early 1980s, Brown Group's warehouse facilities and raw

materials terminals were located in St. Louis. Because of

declining sales caused by foreign competition, Brown Group was

forced to gradually close ten of its northernmost factories by

1982.

In 1982, Brown Group relocated its raw materials terminal from

St. Louis to Benton, Missouri (Benton terminal) in order to better

Brown

zBrown Group is well known for its production of the "Buster

" line of children's shoes.

- 2 -

".-

I??

w

•

service its southern factories.3 Because of delivery delays and

operational problems at the Benton terminal, Brown Group decided

to hire CMR Parcel Service, an outside trucking company, to presort

raw materials and take over some of the delivery routes. As a

result, the amount of work at the Benton terminal decreased

significantly. Brown Group decided that the loss of work required

a reduction of force at the Benton terminal. Neil Page, Brown

Group's assistant director of distribution, directed Rich Williams,

the Benton terminal superintendent, to decrease the number of

hourly union employees by five, from 17 to 12, and reduce the

supervisory staff by one, from three to two. Page gave Williams

no guidelines concerning who should be terminated or what factors

should be considered in making the decision. This action arises

from Brown Group's decision to terminate Hicks, a 51-year-old white

male supervisor, and retain Alvin Chester, a 36-year-old black male

supervisor.4

Hicks started working for Brown Group in February 1948 as a

16-year-old. He worked for Brown Group for 34 years, until he was

discharged at age 51 in 1982. Hicks began working as an order

clerk in the finished goods warehouse, and held that position for

25 years. On December 4, 1972, Hicks was promoted to a foreman

position at the Gustine Avenue warehouse in St. Louis. While at

Gustine Avenue, Hicks supervised every department in the warehouse,

overseeing the filling and packing of finished good orders.

Between late 1977 and May 1980, Hicks held the evening utility

3The Benton terminal is designed to increase efficiency and

facilitate distribution. Drivers transport raw materials from the

Benton terminal to Brown Group factories, and transport finished

goods -from the factories back to Benton. Finished goods are not

warehoused at the Benton terminal.

4The third supervisor was Robert Carbrey, a white male

approximately 55 years of age. Carbrey was the assistant terminal

superintendent at Benton and had more responsibility than Hicks and

Chester. He was not a candidate for discharge. Hicks does not

challenge the retention of Carbrey.

- 3 -

foreman position at the austine Avenue warehouse, where e

in for 15 to 20 other foremen who were absent from work

illness, vacation, or personal reasons. During this peno '

obtained experience supervising the manufacturing or « « material

dock m May 1980, the Gustine Avenue warehouse closed, and the

raw material! dock was moved to the Chouteau Avenue warehouse m

St. Louis.

in June 1980 Hicks was assigned to supervise the evening shift

on the raw materials dock at the Chouteau Avenue warehouse. When

Hicks began working this new position, he was briefly traine y

Alvin Chester, who held the evening supervisor position at th

Chouteau Avenue warehouse prior to Hicks' arrival After Hick

was trained, Chester was assigned to supervise the day shift,

the Chouteau Avenue warehouse closed, Hicks was assigned to

supervise the evening shift at the Benton terminal. Chester, who

began working at the Benton terminal about a month and a half

before Hicks/ briefly trained Hicks and again transferred

day shift when Hicks took over the evening shift.

in July 1968 Chester began working on the raw materials dock

as an hourly union employee at Brown Group's Gravois

facturin, plant in St. Louis. He was promoted to dock foreman in 5 * 7

5The parties dispute how hii/with the

Chouteau. Hicks testlfie about eight hours over a two

5 S & p 2 i o ^ eSCh^tePrr t?stTAed that he trained Hicks for two to

three weeks.

‘Chester did not begin working at the B-nt°" ^ i n a l j n t i l

w t-7 1 0 0 1 hpcause he obtained company approval

needed'hernia operation before transferring to Benton.

71he parties v^thVim

fo? “ r \h?ee daVsf^erefs Chester testified that he trained

Hicks over a two week period.

- 4 -

January 1973,8 where he supervised four or five employees. When

the Gravois Avenue plant closed in 1975, Chester was transferred

to the Gustine Avenue warehouse, where he supervised between eight

and ten employees on the raw materials dock. When the Gustine

Avenue warehouse closed in 1980, Chester was assigned to the

Chouteau Avenue warehouse, where he supervised operations on the

raw materials dock until the facility closed in April 1982.

Chester was transferred to the Benton terminal in April 1982.9

Rich Williams, the Benton terminal superintendent, made the

decision to terminate Hicks and retain Chester. At the time he was

terminated, Hicks had worked for Brown Group for more than 34

years, the last nine and a half years as a supervisor. At the time

Chester was retained, he had 14 years service for Brown Group, and

about the same supervisory experience as Hicks.10 Williams testi

fied that he decided to retain Chester because Chester was better

qualified to supervise the raw material operation at the Benton

terminal. Hicks claimed that Chester was retained because he was

black, and that he (Hicks) was terminated in violation of a company

policy to make employment decisions based on seniority.

Williams notified his supervisor, Neil Page, that he had

decided to terminate Hicks, and Page agreed with the decision. On

June 28, 1982, Hicks was summoned to Brown Group's corporate

offices for a meeting with Page and Williams. Page informed Hicks

that he was chosen to be terminated as a result of the changes in

gAlthough Brown Group claims that Chester has been a full-

fledged supervisor since January 1973, Chester's performance

evaluations listed his position as "Assistant Supervisor" as

recently as September 1978.

’Chester was promoted to the position of terminal

superintendent at Benton in 1985.

10Hicks had been a supervisor about one month longer than

Chester. Hicks was promoted to supervisor in December 1972,

followed by Chester in January 1973.

- 5 -

operation at the Benton terminal. Page told Hicks that Chester was

being retained because he had more experience on the raw materials

dock, knew more about the Benton terminal operation, and was better

able to handle the job.

After his June 28, 1982 meeting with Page and Williams in

Clayton, Hicks returned that same afternoon to the Benton terminal

to gather his personal belongings and say good-bye to his co

workers on the night shift. While he was at the terminal, Hicks

asked Williams whether he had been terminated because he was white

and Chester was black. Hicks testified that although Williams

heard and understood his question, Williams did not deny that race

was a consideration, instead replying "Ken, you said that> not me."

Hicks did not understand this response, so he asked Williams a

second time whether race made a difference. Hicks testified that

Williams looked at him with a side smirk, and said, "Again, you

said that, not me."11 After Hicks' termination, Williams trans

ferred Chester to the evening shift, and Page ordered that Chester

be given a $25.00 raise. Brown Group did not hire another

supervisor to replace Hicks.

Hicks exhausted his administrative remedies and filed suit in

federal district court, alleging that Brown Group's decision to

discharge him violated Section 1981 and the Age Discrimination in

Employment Act, 29 U.S.C. §§ 621-634 (1982 & Supp. V 1987). The

case was tried before a jury on October 3-5, 1988. The jury

11Williams admitted that he had a conversation with Hicks on

the afternoon of June 28, 1982, but testified he told Hicks that

race was not a factor in his termination. Williams testified that

he answered Hicks's question directly the first time Hicks asked

it, and that he did not smirk at Hicks. Brown Group argued to the

jury that Hicks's description of this conversation was inconsistent

and had been embellished over time. The jury evidently chose to

reject Brown Group's contention that Hicks' testimony on this

incident was fabricated or inconsistent.

- 6 -

rejected Hicks' age discrimination claim,12 Special Interrogatories

Nos. 1-3, but found that Brown Group had intentionally discrimi

nated against Hicks on the basis of his race "in that his race was

a discernible or motivating factor in his termination from employ

ment," Special Interrogatory No. 7. The jury also found that Brown

Group "intentionally discriminated against . . . Hicks on account

of his race in that his race was a determining factor in his

termination from employment," Special Interrogatory No. 5. The

jury found that Hicks was entitled to no compensatory damages, but

awarded him $10,000 in punitive damages after finding that Brown

Group "acted out of evil motive or intent, or acted with callous

indifference to [Hicks'] federally protected rights," Special

Interrogatory No. 8. Finally, in response to Special Interrogatory

No. 10, the jury found that Brown Group would have terminated Hicks

even if his race or age had "not been a discernible or motivating

factor or a determining factor in the decision to terminate." The

jury was not requested to consider the question of nominal damages.

After modifying the jury verdict through a grant of additur

in the amount of $1.00 nominal damages, the district court enforced

the jury verdict by awarding Hicks $10,000 in punitive damages.

Brown Group's motion for a JNOV and Hicks' motion for post-trial

equitable relief were denied. The district court subsequently

awarded Hicks $18,562.50 in attorneys' fees and $2,189.00 in costs.

This timely appeal and cross-appeal followed. After the United

States Supreme Court decision in Patterson v._McLean Credit Union,

491 U.S. ___, 109 S. Ct. 2363 (1989), this court granted leave for

the parties to file supplemental briefs.

12Hicks has not cross-appealed the jury verdict on the age

discrimination claim.

- 7 -

-U-r—Section 1981

The threshold question we must address in this reverse race

discrimination case is whether racially discriminatory discharge

is actionable under Section 1981. Section 1981 provides as

follows:

All persons within the jurisdiction of the

United States shall have the same rl9ht ^ every State and Territory to make and enforc

contracts, to sue, be parties, _ “ aSs and to the full and equal benefit of all laws and proceedings for the security of persons

and property as is enjoyed by white and Pshall be subject to like Pu^ h m e n t ^

pains, penalties, taxes 1.̂ ê . s ' and eXaC tions of every kind, and to no other.

42 U.S.C. § 1981.

in n,tt.rsnn V. Morgan Credit Union, 109 S. Ct. 2363 (1989)

(Patterson), the United States Supreme Court limited the scope o

Section 1981. The Court interpreted the meaning and scope of the

rights "to make and enforce contracts," and held that neither right

extended to prohibit racial harassment in the employment relation

ship. Id. at 2373-74. The Patterson decision did not addre

whether discriminatory discharge falls within the ambit of the

rights to make and enforce contracts. Based on our examination o

the nature of discharge and our interpretation of Section 1981 as

well as the legislative history of Section 1981, we conclude that

a claim for discriminatory discharge continues to be cognizable

under Section 1981.

A.

We must first determine whether a fair reading of Patterspn

requires us to find that discriminatory discharge is no longer

actionable under Section 1981. A careful analysis of Patterson

- 8 -

demonstrates that discharge was not at issue or discussed, and

nothing in that opinion requires us to overrule the numerous and

long—settled cases in this circuit which hold that discriminatory

discharge is actionable under Section 1981. See, e.g. , Estes—y_*_

Dick Smith Ford. 856 F.2d 1097, 1100-01 (8th Cir. 1988); Williams

v. Trans World Airlines. Inc.. 660 F.2d 1267, 1268 (8th Cir. 1981);

Person v. J.S. Alberici Constr. Co., 640 F.2d 916, 918-19 (8th Cir.

1981).

We first examine the facts and procedural history of Patterson

in order to better understand its analysis of the rights to make

and enforce contracts. In Patterson, the plaintiff was a black

woman who was employed as a teller and file coordinator for ten

years before being laid off. She brought an action in the United

States District Court for the Middle District of North Carolina,

alleging that her employer had harassed her, failed to promote her,

and discharged her because of her race in violation of Section

1981.13 109 S. Ct. at 2368-69. The district court submitted the

Section 1981 discharge and promotion claims to the jury, which

returned a verdict for the employer. The district court .deter

mined that Patterson's claim for racial harassment was not

actionable under Section 1981, and granted a directed verdict in

favor of the employer.

On appeal,14 the Fourth Circuit affirmed. Patterson v. McLean

13The plaintiff also raised a pendent state law claim for the

intentional infliction of emotional distress. The district court

granted a directed verdict for the employer on this issue, and the

Fourth Circuit affirmed. See Patterson v. McLean Credit Union, 805

F.2d 1143, 1146 (4th Cir. 1986).

uThe plaintiff appealed the district court's award of directed

verdicts in favor of the employer on the Section 1981 racial

harassment claim and the pendent state law claim for intentional

infliction of emotional distress. Patterson_v.— McLean Credit

Union. 805 F.2d 1143, 1145-46 (4th Cir. 1986). The plaintiff also

appealed the exclusion of proffered testimony by two witnesses, one

in support of her harassment claim and the other in support of her

- 9 -

rrgdit Union. 805 F.2d 1143-(4th Cir. 1986). The court held that

racial harassment was not cognizable under Section 1981, but noted

that evidence of racial harassment may implicate the terms and

conditions of employment under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act

of 1964, 42 U.S.C. § 2000e (1982), or be probative of the discrimi

natory intent required to prove a Section 1981 violation. Id. at

1145. In discussing its ruling on the harassment claim, the Fourth

Circuit expressly noted that a claim of discriminatory discharge

goes to the very essence of the employment contract, and thus falls

easily within Section 1981's protection. Id.

The Supreme Court granted certiorari, see 484 U.S. at 814

(1987), to decide two questions: (1) whether Patterson's racial

harassment claim was actionable under Section 1981, and (2) whether

a jury instruction requiring her to prove that she was better

qualified to establish her Section 1981 promotion claim was erro

neous. Patterson. 109 S.Ct. at 2369. After initial oral

argument, the Court requested the parties to brief and argue

whether or not the Court should reconsider the interpretation of

Section 1981 adopted in Runyon v. McCrary, 427 U.S. 160 (1976)

(Runyon), which held that Section 1981 prohibited discrimination

in the making and enforcement of private contracts. See 485 U.S.

at 617 (1988).

The Court unanimously agreed that Runyon should not be over

ruled. Justice Kennedy, writing for a 5-4 majority, held that

Runvon should not be overruled because no special justification was

shown to warrant departure from the principle of stare decisis, the

decision had not proved unworkable, and "Runyon [was] entirely

consistent with our society's deep commitment to the eradication

promotion claim. Id. at 1147. Finally, ^^vre'^that sheaDDealed a jury instruction which required her to prove that sn was more qualified than the person promoted in order to prevaj

her Section 1981 promotion claim. Id. The plaint .appeal the jury verdict rejecting her Section 1981 discharge claim.

- 1 0 -

of discrimination based on a person's race or the color of his or

her skin." Patterson. 109 s. Ct. at 2371. The Court then

considered whether Patterson's racial harassment and failure to

promote claims fell within either of the two enumerated contract

rights protected by Section 1981. The Court noted that the most

obvious feature of Section 1981 is that it forbids discrimination

only in the making and enforcement of contracts, and that it could

not be construed as a general proscription of racial discrimination

in all aspects of contract relations. Id. at 2372.