McKinnie v. Tennessee Petition for Writ of Certiorari

Public Court Documents

October 7, 1963

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. McKinnie v. Tennessee Petition for Writ of Certiorari, 1963. c37b98a2-bc9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/7cbe4619-e643-40e0-bbf9-3c796d9628a6/mckinnie-v-tennessee-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari. Accessed February 17, 2026.

Copied!

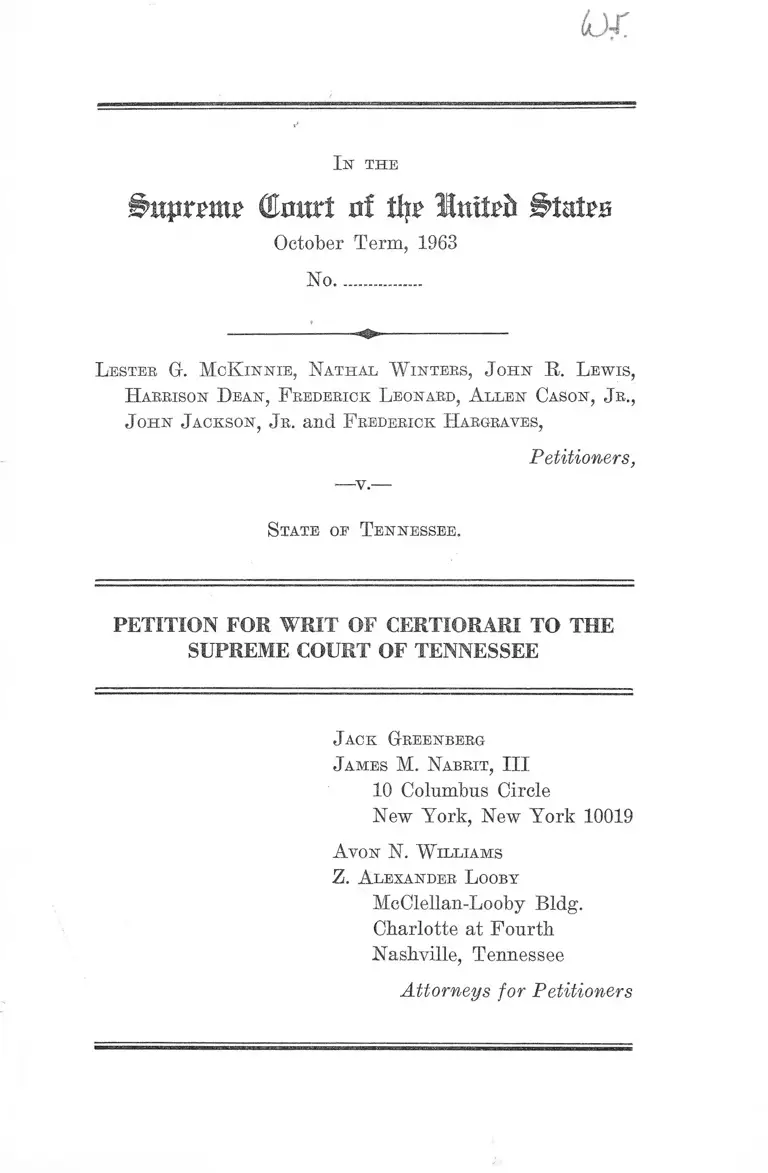

I n th e

ûprrutr Court of % Imtrft B u U b

October Term, 1963

No................

L ester G. McK innie, Nathal W inters, J ohn R. L ewis,

H arrison Dean, F rederick L eonard, A llen Cason, Jr.,

J ohn J ackson, Jr. and F rederick Hargraves,

Petitioners,

State oe T ennessee.

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

SUPREME COURT OF TENNESSEE

J ack Greenberg

James M. Nabrit, III

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

A von N. W illiams

Z. A lexander L ooby

McClellan-Looby Bldg.

Charlotte at Fourth

Nashville, Tennessee

Attorneys for Petitioners

I N D E X

Citation to Opinion Below ........_....... ...... ................ . 1

Jurisdiction ............ ................................ ....... ................... 1

Questions Presented ____________ __ ________________ 2

Statutory and Constitutional Provisions Involved .... 3

Statement ............................ ................. .................... ..... . 4

How the Federal Questions Were Raised and Decided

Below.............................................................................. 9

Reasons for Granting the Writ ............ .................... . 13

I. Petitioners’ Convictions Offend the Fourteenth

Amendment to the United States Constitution

in That They Constitute State Enforcement of

Racial Discrimination ......... ...... .......... .... ...... ....... 13

A. The State of Tennessee Has by Statute Per

mitted and Encouraged Racial Segregation in

Restaurants ....................... .................... ..... ..... 13

B. The State of Tennessee by Arrest and Crim

inal Conviction of Petitioners Deprived Them

of Equal Protection of the Laws ........... ...... 15

II. These Convictions Deny Due Process of Law Be

cause Based on No Evidence of the Essential

Elements of the Crime of Unlawful Conspiracy .. 18

PAGE

11

III. Petitioners Were Denied Due Process in That

Their Convictions Were Affirmed on a Ground

Not Litigated in the Trial Court ............. ............ 23

IV. Petitioners Were Denied Due Process in Violation

of the Fourteenth Amendment When the Trial

Judge Instructed the Jury That Petitioners Were

Charged With Violation of a Statute When (a)

Petitioners Had Not in Fact Been Indicted for

Violation of the Statute and (b) It Was Not

Even a Criminal Statute ........................ ............ 25

V. Petitioners Were Denied a Fair and Impartially

Constituted Jury Contrary to Due Process of Law

and Equal Protection of the Laws Secured by the

Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Con

PAGE

stitution ............ 28

Conclusion ...................................... 30

A ppendix.............. la

Opinion of Supreme Court of Tennessee ________ la

Judgment .......... -.............-................................. ....... 14a

Opinion on Petition to Rehear............. .................... 16a

Judgment on Petition to Rehear ------------- ------- 18a

Table of Cases

Aldridge v. United States, 283 U. S. 308 ............. ....... 29, 30

Aymett v. State, 310 S. W. 2d 460 ......... .................... 19

Barr v. City of Columbia, No. 9, October Term, 1963 .. 15

Bell v. Maryland, No. 12, October Term, 1963 ......... 15

Bouie v. City of Columbia, No. 10, October Term, 1963 15

Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S. 60 ________________ 16

Burton v. Wilmington Parking Authority, 365 U. S.

715 .................................................... ........... ................ 14,16

Cantwell v. Connecticut, 310 U. S. 296 ......................... 22

Cline v. State, 319 S. W. 2d 227 ........ 19

Cole y. Arkansas, 333 IT. S. 196 ......... 24

DeJonge v. Oregon, 299 IT. S. 353 .......... ...................... 26

Delaney v. State, 164 Tenn. 432 _____ 19

Garner v. Louisiana, 368 IT. S. 157 ............... 22

Glasser v. United States, 315 U. S. 60 ..... 29

Griffin v. Maryland, No. 6, October Term, 1963 ______ 15

Kelley v. Board of Education, 270 F. 2d 209 (6th Cir.

1959) .............................................................................. 16

Lasater v. State, 68 Tenn. 584 (1877) ____ ____ _____ 14

Lombard v. Louisiana, 373 U. S. 267 .............................. 15

Peterson v. City of Greenville, 373 TJ. S. 244 ..............14,15

Robinson v. Florida, No. 6, October Term, 1963 .......... 15

Roy v. Brittain, 201 Tenn. 140, 297 S. W. 2d 72 ....... 16

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1 _____________ ______ 16,17

Smith v. State, 205 Tenn. 502 .......... ................. ........ 19

Smith v. Texas, 311 U. S. 128______________________ 29

State of Delaware v. Brown, 195 A. 2d 379 (1963) .... 17

Stromberg v. California, 283 U. S. 359 .......... ...........26, 27

Taylor v. Louisiana, 370 U. S. 154......... ....................... 22

Terminiello v. Chicago, 337 U. S. 1 .................. ........ .26, 27

Ill

PAGE

IV

PAGE

Thiel v. Southern Pac. Co., 328 U. S. 218 ....... ............... 29

Thompson v. Louisville, 362 IT. S. 199 .......................... 22

Trustee of Monroe Ave. Church of Christ v. Perkins,

334 U. S. 813 ___________ __ _______ __________ ___ 16

Turner v. Memphis, 369 U. S. 350 (1962) ...... ....... ........ 14

Winters v. New York, 333 U. S. 507 __ __________ ___ 22

Statutes:

Constitution of Tennessee, Article 1, Section 9 ......... 11

Constitution of Tennessee, Article 11, Section 12 ........ 16

T. C. A. §39-1101-(7) ___ __________

T. C. A. §§41-303, 41-1217 __________

T. C. A. §§49-3701, 3702, 3703, 3704

T. C. A. §§53-2120, 53-2121 _______

T. C. A. §§58-1021, 58-1412 _______ _

T. C. A. §62-710 .............. ................2,

T. C. A. §62-711 ................................

T. C. A. §62-715 ......... ....... ...........

T. C. A. §§65-1704-1709 .............. .......

T. C. A. §§65-1314-1315.....................

Title 28, IT. S. C. §1257(3) ...............

....2, 5,10,18, 25, 26, 27

........................... 16

............ ....... 16

__________ _____ 14

........................... - 16

10,14,17, 23, 25, 26, 27

3, 5, 9,10,18, 25, 26, 27

...................... ...... 16

........................... 16

............. ............... 16

............................ 1

In the

Bnpnmz (Emtrt af tit? lmt?d l̂ tatpis

October Term, 1963

No................

L ester G. McK innie, Nathal W inters, J ohn R. L ewis,

H abbison Dean, F rederick Leonabd, A llen Cason, Jb.,

J ohn Jackson, Jb. and F redebick Hargraves,

Petitioners,

State oe T ennessee.

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

SUPREME COURT OF TENNESSEE

Petitioners pray that a writ of certiorari issue to review

the judgment of the Supreme Court of Tennessee entered

in the above-entitled cases on January 8, 1964.

Citation to Opinion Below

The opinion of the Supreme Court of Tennessee is not

yet reported and is set forth in the appendix hereto, infra

pp. l-13a with the opinion on Petition to Rehear at pp. 16-

17a.

Jurisdiction

The judgment of the Supreme Court of Tennessee was

entered on January 8, 1964 (App. p. 15a). Petition for

rehearing was denied March 5, 1964 (App. p. 18a).

2

Jurisdiction of this Court is invoked pursuant to Title 28,

U. S. C., Section 1257(3), petitioners having alleged below,

and alleging here, deprivation of rights, privileges, and

immunities secured by the Constitution of the United States.

Questions Presented

Whether petitioners, Negro college students, were denied

rights protected by the due process and equal protection

clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States

Constitution:

1. By arrest and conviction for unlawful conspiracy

after peacefully protesting against racial segregation in a

“white” restaurant where they were denied entrance and

service solely because they were Negroes and where racial

segregation was permitted and encouraged by state statute.

2. By the use of state police officials to arrest and state

courts to convict petitioners for unlawful conspiracy for

the distinct purpose of enforcing the racially discrimina

tory practices of a restaurant owner.

3. By conviction on a record devoid of any evidence of

the essential elements of unlawful conspiracy.

4. By affirmance of their convictions in the Supreme

Court of Tennessee on a ground not litigated in the trial

court thereby denying them an appeal which considered

the case as it was tried.

5. By the trial judge in twice instructing the jury that

petitioners were charged with violating a law under which

they had not been indicted and which was not even a crim

inal statute.

6. By trial by an all white jury whose admitted per

sonal practice, custom, philosophy and belief in racial seg

regation precluded petitioners’ having a fair and impartial

3

jury of their peers, and by the trial judge’s refusal to dis

miss jurors challenged by petitioners for good cause.

Statutory and Constitutional

Provisions involved

This case involves Section 1 of the Fourteenth Amend

ment of the Constitution of the United States and the fol

lowing sections of the Code of the State of Tennessee:

39-1101. “Conspiracy” defined.—The crime of con

spiracy may be committed by any two (2) or more

persons conspiring: . . . (7) to commit any act in

jurious to public health, public morals, trade, or com

merce . . .

62-710. Right of owners to exclude persons from

places of public accommodation.—The rule of the com

mon law giving a right of action to any person excluded

from any hotel, or public means of transportation, or

place of amusement, is abrogated; and no keeper of any

hotel, or public house, or carrier of passengers for

hire (except railways, street, interurban, and commer

cial) or conductors, drivers, or employees of such car

rier or keeper, shall be bound, or under any obligation

to entertain, carry, or admit any person whom he shall,

for any reason whatever, choose not to entertain, carry,

or admit to his house, hotel, vehicle, or means of trans

portation, or place of amusement; nor shall any right

exist in favor of any such person so refused admission;

the right of such keepers of hotels and public houses,

carriers of passengers, and keepers of places of amuse

ment and their employees to control the access and ad

mission or exclusion of persons to or from their public

houses, means of transportation, and places of amuse

ment, to be as complete as that of any private person

4

over his private house, vehicle, or private theater, or

places of amusement for his family.

62-711. Penalty for riotous conduct.—A right is

given to any keeper of any hotel, inn, theater, or public

house, common carrier, or restaurant against any per

son guilty of turbulent or riotous conduct within or

about the same, and any person found guilty of so

doing may be indicted and fined not less than one hun

dred dollars ($100), and the offenders shall be liable

to a forfeiture of not more than five hundred dollars

($500), and the owner or persons so offended against

may sue in his own name for the same.

Statement

These are eight sit-in convictions arising out of a single

trial in Nashville, Tennessee.1 Petitioners, all Negroes,

were arrested between 12:30 and 1:00 P.M. at the Burras

and Webber Cafeteria2 (B.E. 765) and charged under a

grand jury indictment3 (ft. 9-13) alleging that they:

On the 21st day of October, 1962, and prior to the find

ing of this presentment, with force and arms in the

1 A single record and transcript of testimony exists for all eight

petitioners and a single opinion, affirming the convictions, was

written by the Supreme Court of Tennessee (App. pp. l-13a).

Reference to the Technical Record will be designated (R. — ),

and to the Bill of Exceptions (B.E. — ).

2 Burrus and Webber Cafeteria will hereafter be referred to as

B. & W.

3 Petitioners were arrested without warrants by Nashville police

officers and originally charged with violating City Code Chapter 26,

Section 59 (state law regarding sit-ins) (B.E. 885). Eater, on

the same day, warrants were issued charging them with unlawful

conspiracy. The grand jury presentment was made on December

12, 1962 (R. 8).

5

County aforesaid, unlawfully, willfully, knowingly, de

liberately and intentionally did unite, combine, con

spire, agree and confederate between and among them

selves, to violate Code Section 39-1101-(7) and Code

Section 62-711, and unlawfully to commit acts injurious

to the restaurant business, trade and commerce of Bur

ras and Webber Cafeteria, Inc., a corporation located

at 226 Sixth Avenue, North, Nashville, Davidson

County, Tennesee (R. 9).

After trial and conviction in the County Court of David

son County, Tennessee, petitioners were sentenced to ninety

(90) days in jail and fifty dollars ($50.00) fine4 (R. 39, 40).

Appeals were taken to the Supreme Court of Tennessee

which affirmed the convictions (R. 54). It is from this

affirmance that this petition for writ of certiorari is brought.

Around noon on October 21,1962, eight young Negro men,

all college students, quietly entered the front door5 of the

B. & W. Cafeteria (B.E. 766). Two swinging doors on the

sidewalk opened on the vestibule (B.E. 767), six feet by four

feet in size (B.E. 1070).6 Another set of swinging doors led

into the dining room (B.E. 767).

As petitioners approached the second doors, they were

met by Otis Williams, the doorman (B.E. 1071), and told,

“We don’t serve colored people in here. I want to be nice

to you but we don’t serve ’em . . . and you can’t come in”

4 The jury recommended a fine of less than fifty dollars ($50.00)

(R. 38), but the trial judge later imposed the severer sentence.

5 The cafeteria had a front entrance and a back entrance (B.E.

825).

6 Estimates on the size of the vestibule varied from four feet by

four feet (B.E. 767) to twelve feet by twelve feet (B.E. 903),

though Otis Williams, the doorman at B. & W. testified that he

measured it as six feet by four feet (B.E. 1070).

6

(B.E. 1071).7 Petitioners remained standing in the vestibule

for approximately “20 or 25 minutes” when they were ar

rested (B.E. 772). They committed no act other than at

tempting to walk through the swinging doors into the

cafeteria (B.E. 771, 1098). People were walking in front of

the cafeteria, and estimates of the number of people who

stood by or near the outside door of the vestibule varied

from three or four to seventy-five or one hundred (B.E.

780, 787, 808, 828, 918-919, 956). It was not established how

many, if any, of those standing outside desired to en

ter the B. & W. or were just curious observers. No wit

ness testified that they were prevented either from entering

or leaving the cafeteria (B.E. 782-792, 809-810, 841, 892-

895, 919-923, 933, 948-949, 960, 1000, 1005, 1025, 1032-1033,

1039), nor was there evidence of any turbulent, riotous or

disorderly conduct, by petitioners or others, either inside

or outside the cafeteria.

W. W. Carrier, Manager of B. & W., informed of peti

tioners’ presence, entered the vestibule (B.E. 766) and testi

fied that he “discovered a large gathering of people8 . . .

on the outside and eight young Negroes were in the vesti

bule in between the two doors” (B.E. 766). Carrier did not

speak to petitioners (B.E. 771). He called the police and

went outside to wait for them (B.E. 771). He testified:

7 Williams, a 64 year old man weighing only 140 pounds, held

the door and kept petitioners out while allowing white patrons

in the vestibule to enter the cafeteria, one at a time, through a

“ crack in the door” (B.E. 1070-1071, 1078-1080). He stated he

was hired to keep Negro patrons out (B.E. 1088) and was ordered

to lock the doors if Negroes came (B.E. 1097). When petitioners

arrived, Williams “ caught the door going into the cafeteria and

stopped them there, and the white people, too . . . ” (B.E. 1065).

8 Carrier did not estimate the number of people.

7

Q. As you attempted to pass through the vestibule,

what, if anything, occurred?

A. Well, actually nothing, sir. The—the young men

were standing in position, and it was just a matter of

my easing through the crowd (B.E. 772).

Petitioners informed him that they were seeking service

(B.E. 775), but Carrier refused because they were Negroes®

(B.E. 776). At no time did he order petitioners to leave.9 10

His sole comment was to request that they move back and

let a lady get out (B.E. 773) which petitioners did (B.E.

773). He admitted that persons were able to get in and out

of the cafeteria.11

Several patrons of B. & W. testified that the doorman

was holding the door so the petitioners could not enter,

thus causing the congestion (B.E. 785, 893).12 All entered

9 On cross-examination Carrier stated:

“ Q. You have the facilities to serve them!

A. We do have.

Q. Was your place of business crowded at the time?

A. It was beginning to be crowded, sir.

Q. Now, the only reason that you didn’t serve them was that

they were Negroes and not white, wasn’t it?

A. Yes, sir.

Q. And the same boys, seeking service would have been all

right if they were white?

A. Yes, sir” (B.E. 776-777).

10 Carrier testified he did not swear out warrants against peti

tioners and had no idea how his name appeared on them as prose

cutor (B.E. 823).

11 “ Q. What occurred to those persons in their attempt to gain

access to the cafeteria and leave?

A. Well, it was a little crowded . . . ” (B.E. 770).

12 Charles Edwards stated:

“ Q. If the doorman hadn’t blocked the door, they would have

gone in the place, so that ingress and egress would have

been free? Wouldn’t it?

A. I suppose so, if he had wanted Negroes in, too.

Q. Yes, sir, the doorman was blocking them so that they

couldn’t get in?

the cafeteria though a few spoke of having to “ elbow” or

“push” their way through (B.E. 814, 933). Most entered

without any difficulty at all.13

Two witnesses testified that petitioners were “pushing

and shoving” in the vestibule (B.E. 900-901, 977). How

ever, they admitted that petitioners used no bad language

and committed no disorderly act (B.E. 977). One witness

testified that as she approached the restaurant she heard

someone say, “When we get there, just keep pushing, don’t

stop. Just keep on pushing,” that she looked around and

saw a group of Negroes who passed her on the street and

entered the restaurant (R. 971, 987-990). No evidence,

however, was offered to prove that petitioners agreed or

conspired to block the entrance of B. & W.

A. The doorman was holding the door and the Negroes were

blocking the vestibule so they couldn’t get in there.

Q. . . . The doorman was the one who was blocking the door

and keeping people out? Wasn’t he?

A. He was holding the Negroes out and as a result, they

had the vestibule blocked and the other people couldn’t

get by.”

13 Mrs. Charles Edwards testified that she “ just went right in”

(B.E. 799). Mickey Lee Martin testified:

“ Q. You had no trouble getting in?

A. No, sir.

Q. Did you have to ask them to let you in ?

A. Sir?

Q. Did you have to ask these colored boys to let you in?

A. Yes, sir.

Q. And did they let you in ?

A. Yes, sir, they let me in” (B.E. 882).

Patrolman Pyburn went to the B. & W. and testified that peti

tioners were standing four on either side of the vestibule and that

“a person medium sized could get in” (B.E. 1030-1031).

9

How the Federal Questions Were Raised

and Decided Below

After motions to remand the cases from the County

Court of Davidson County, Tennessee to the Court of Gen

eral Sessions were denied on January 4, 1963 (E. 22), peti

tioners, on January 10, 1963, filed a motion to quash the

grand jury presentment and to dismiss alleging that (1) the

State of Tennessee, through its judicial officers, was en

forcing a policy of racial discrimination contrary to the

Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution ;

(2) the State was forbidden by the Fourteenth Amendment

from prosecuting defendants under T. C. A. §62-711; (3)

the acts charged constituted no crime; (4) the presentment

neither alleged nor showed defendants conspired to do an

unlawful act or an unlawful act by unlawful means; and

(5) the rights exercised by petitioners were protected by

the due process and equal protection clauses of the Four

teenth Amendment to the United States Constitution. Janu

ary 15, 1963, motion to quash and to dismiss overruled

(E. 27).

January 30, 1963, defendants filed motion to quash the

presentment or, in the alternative, to require the State to

make an election as to which of the state statutes alleged

in the indictment to prosecute the defendants under (E. 28).

February 1, 1963, motion overruled and defendants ex

cepted (R. 29). Upon arraignment on March 5, 1963, defen

dants entered pleas of not guilty (E. 30). Defendants

were convicted in the County Court of Davidson County,

Tennessee on March 9,1963 (E. 38). The jury recommended

a fine of less than fifty dollars ($50.00). March 19, 1963, the

court entered judgment and sentenced defendants to fifty

dollar ($50.00) fines and ninety (90) days in the County

Workhouse (E. 39, 40).

10

April 18, 1963, petitioners filed motions for new trial on

the grounds that: (1) the court erred in overruling defen

dants’ motions to remand the cases to the Court of General

Sessions; (2) the court erred in overruling defendants’ mo

tion to quash the presentment and to dismiss the action;

(3) the court erred in overruling defendants’ motion to

quash the presentment or, in the alternative, to require the

State to make an election as to which of the state statutes

alleged in the indictment to prosecute the defendants under;

(4) the statutes under which defendants were arrested,

tried and convicted were unconstitutional because they

failed to warn defendants of the conduct proscribed and

contained no standards upon which a judicial determination

of guilt could be made, contrary to the due process clause

of the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Con

stitution; (5) T. C. A. §62-710, one of the statutes under

which defendants were charged, is not a criminal statute

and conviction thereunder denied due process secured by

the Fourteenth Amendment; (6) T. C. A. §§39-1101-(7),

62-710 and 62-711 were unconstitutionally applied to peti

tioners’ conduct because used to enforce racial segregation

in facilities licensed by the State, open to the public, and

invested with a public interest, contrary to the due process

and equal protection clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment

to the United States Constitution; (7) the arrest, trial and

conviction of defendants were for the sole purpose of en

forcing the discriminatory practices of a restaurant owner

contrary to the due process and equal protection clauses of

the Fourteenth Amendment; (8) there was no evidence that

defendants committed any act either a breach of the peace,

injurious to the trade or commerce or turbulent and riotous;

(9) prosecution of defendants denied them the right of

free assembly and protest guaranteed by the First and

Fourteenth Amendments to the United States Constitution;

(10) defendants were tried and convicted by a jury from

11

which all Negro veniremen were deliberately and systemati

cally challenged by the State, depriving them of a fair

and impartial jury in violation of Article 1, Section 9 of

the Constitution of the State of Tennessee and the equal

protection and due process clauses of the Fourteenth

Amendment to the Constitution of the United States; (11)

the court erred in holding certain white jurors competent

who admitted a prejudiced attitude toward defendants con

trary to Article 1, Section 9 of the Constitution of Ten

nessee and the due process and equal protection clauses of

the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitu

tion ; (12) there was no evidence of guilt of the offense

charged in the presentment; (13) the evidence preponder

ated in favor of defendants’ innocence; (14) the court’s

judgment and sentence were contrary to the jury verdict

and deprived defendants of rights secured by the due proc

ess clause of the Fourteenth Amendment; (15) the court

erred in denying certain instructions to the jury requested

by defendants contrary to the equal protection and due

process clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment to the United

State Constitution (R. 41-50).

Motion for new trial was overruled May 10, 1963 (R. 53).

Defendants excepted and “prayed an appeal in the nature

of a writ of error” to the Supreme Court of Tennessee (R.

54). Bill of Exceptions to the County Court order over

ruling motion for new trial filed May 31, 1963 (R. 63).

On appeal to the Supreme Court of Tennessee the convic

tions were affirmed. The Court held that:

These defendants physically blocked the entrance to

the B&W Cafeteria by placing themselves in the small

vestibule so as to prevent people from entering or leav

ing ; and that entrance to and exit from the restaurant

was not possible without squeezing and worming

through the wall of flesh created by the defendants’

12

presence and position. The evidence likewise shows

that in blocking this entrance the defendants were

pushing and shoving to some extent in an effort to

enter this restaurant, but were prevented from doing

so because the doorman kept the inner door closed to

them.

It further held that:

While the request for admittance by the defendants

was not criminal in the first instance, and while for the

sake of argument, we may even assume that they had

a right to go on the premises of the restaurant, the

method they employed to effect their admittance was

clearly unlawful.

The Court stated that the dispositive question on appeal

was whether or not the evidence showed that defendants

used unlawful means; blocked the doorway of B. & W .;

concluded that they did.

Petition for rehearing filed and denied March 5, 1964

(App. 16, 17a).

13

Reasons for Granting the Writ

The decision below conflicts with applicable decisions of

this Court on important constitutional issues.

I.

Petitioners’ Convictions Offend the Fourteenth

Amendment to the United States Constitution in That

They Constitute State Enforcement o f Racial Discrimi

nation.

A. The State of Tennessee Has by Statute Permitted and

Encouraged Racial Segregation in Restaurants.

The undisputed and sole basis for petitioners’ arrest

and conviction was racial discrimination. At the time of

arrest, petitioners were seeking service at B. & W., a white

restaurant in the City of Nashville, Tennessee. When re

fused entrance to the B. & W., they quietly remained in the

vestibule until arrested. They were jailed and originally

charged with violation of the “ state law regarding sit-ins”

(B.E. 765). Later, the Davidson County grand jury re

turned a presentment charging petitioners with unlawful

conspiracy to injure trade or commerce by attempting to

compel white restaurateurs, including the owners of B. & W.,

to serve Negroes contrary to their policy of racial segre

gation.14

14 The presentment alleged, inter alia, that:

. . . Under the provisions of §62-710 of the Code of Tenn., the

owner of said cafeteria reserved the right not to admit and to

exclude from said cafeteria any person the owner, for any reason

whatsoever, chose not to admit or serve in said cafeteria.

Among the rules established by the owner of said B. & W. was

one that they would serve food only to persons of Caucasian

descent, or white persons, and not to serve food to persons of

African descent, or colored persons, and said B. & W. Cafeteria

was known to the general public as a cafeteria and dining place,

privately owned, serving food only to white persons.

14

The manager and the doorman15 of B. & W. stated peti

tioners were refused service solely because they were

Negroes (B.E. 776-777). In his charge the trial judge ex

pressly instructed the jury to convict if it found petition

ers conspired to violate, inter alia, T. C. A. §62-710, pro

viding that a restaurateur may exclude persons for “any

reason whatsoever,” including race. Lasater v. State, 68

Tenn.584 (1877).16

It is patently clear from these facts that the purpose of

petitioners’ arrest and conviction was to enforce racial

discrimination which was permitted and, indeed, encouraged

by T. C. A. §62-710. It is equally clear that such state

sanction of racial discrimination conflicts with the Four

teenth Amendment. Burton v. Wilmington Parking Au

thority, 365 U. S. 715 (Stewart, J., concurring). (When a

state law sanctions racial discrimination in restaurants,

the 14th Amendment is invoked.)

In Peterson v. City of Greenville, 373 U. S. 244, this

Court reversed trespass convictions where state law re

quired a restaurant owner to discriminate and stated:

15 Indeed, the doorman was expressly hired for the purpose of

keeping Negroes out. (B.E. 1088).

16 In 1875, the State of Tennessee repealed its Common Law

innkeeper rule requiring innkeepers to serve all on an equal

basis and passed T. C. A. §62-710 permitting them to discriminate.

And see Turner v. Memphis, 369 U. S. 350 (1962). There a

restaurant owner set up as a defense to an action brought to

enjoin racial segregation in the Dobbs House Restaurant in the

City of Memphis T. C. A. §§53-2120, 53-2121, which authorized

the Division of Hotel and Restaurant Inspection of the State De

partment of Conservation to issue “such rules and regulations . . .

as may be necessary pertaining to the safety or sanitation of

hotels and restaurants . . . ” The Inspection Division passed a

regulation providing that “restaurants catering to both white and

Negro patrons” should be arranged so that each race is properly

segregated (Regulation No. R -18(L )). Dobbs House later amended

its answer to include a defense based on T. C. A. §62-710 as jus

tification for its discrimination.

15

When the State has commanded a particular result, it

has saved to itself the power to determine that result

and thereby “ to a significant extent” has “become in

volved” in it, and, in fact, has removed that decision

from the sphere of private choice (373 U. S. at 248).

When the state passes a law, as here, permitting and

encouraging persons to discriminate against other persons

because of race, and the state’s judicial processes are em

ployed to enforce that same discrimination, such a “palpable

violation of the Fourteenth Amendment cannot be saved by

attempting to separate the mental urges of the discrim

inator” (Peterson, supra at 248).

In Lombard v. Louisiana, 373 U. S. 267, there was no

segregation provision but certain city officials had made

pronouncements regarding segregation in restaurant facili

ties. This Court found this constituted state compulsion of

racial discrimination and reversed trespass convictions.

The state’s involvement here is much stronger than, or at

most equal to, that in Lombard. Indeed, existence of a state

statute permitting and encouraging restaurateurs to dis

criminate brings this case within the prohibition of Peter

son.

B. The State of Tennessee by Arrest and Criminal

Conviction of Petitioners Deprived Them of

Equal Protection of the Laws.

The issues presented by this petition are almost identical

to those presented in the “ Sit-in” cases now pending before

this Court in Barr v. City of Columbia, No. 9, October

Term, 1963; Bouie v. City of Columbia, No. 10, October

Term, 1963; Bell v. Maryland, No. 12, October Term, 1963;

Robinson v. Florida, No. 60, October Term, 1963; and

Griffin v. Maryland, No. 6, October Term, 1963. Here, as

16

in. those cases, the question presented is whether a state

may enforce, by arrest and criminal conviction, racial dis

crimination in public accommodations, particularly where,

as here, the state has been significantly involved in the

acts of discrimination. That petitioners were in a cafeteria

vestibule and not at a lunch counter, and charged with

unlawful conspiracy rather than trespass, does not ma

terially change the issues involved. As the questions pre

sented are identical with, or similar to, issues now pending

before this Court in other cases where certiorari has been

granted, review of this petition is manifestly appropriate.

Compare Trustee of Monroe Ave. Church of Christ v.

Perkins, 334 U. S. 813, with Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1.

There is no question but that the State of Tennessee, by

arrest and criminal conviction, has “ place [d] its authority

behind discriminatory treatment based on race.” Burton

v. Wilmington Parking Authority, 365 U. S. 715 (Frank

furter, J., dissenting). No question exists but that this

constitutes state action forbidden by the Fourteenth

Amendment. Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1; Buchanan

v. Warley, 245 U. S. 60. State action is further involved

here because the State of Tennessee has fostered and but

tressed racial segregation by state law,17 custom and tradi

tion and has thereby significantly contributed to and sup

ported the racial discrimination practiced by B. & W.

17 In Tennessee, Negroes and whites have been prohibited from

studying together (Art. 11, Const, of Tenn., §12; T. C. A. §§49-3701

(held unconstitutional in Boy v. Brittain, 201 Tenn. 140, 297

S. W. 2d 72), 3702, 3703, 3704 (invalidated in Kelley v. Board

of Education, 270 F. 2d 209 (6th Cir. 1959) ; going to prison

together (T. C. A. §§41-303, 41-1217) ; marrying one another

(T. C. A. §§49-3704, 36-402) ; riding streetcars together (T. C. A.

§§65-1704-1709) ; or trains (T. C. A. §§65-1314-1315) ; using the

same washhouses in coal mines (T. C. A. §§58-1021, 58-1412).

Moreover, Tennessee law expressly permits hotels to provide sepa

rate accommodations for Negroes and whites (T. C. A. §62-715).

17

Moreover, in addition to this, the State of Tennessee has

refused to protect petitioners’ primary right to equality

against the narrow, less significant property claim of res

taurant owners and has actively endorsed and supported

restaurateurs’ “ right to discriminate” by statute as well

as by use of the state judicial process. Such palpable use

of state power to enforce inequality far exceeds the thresh

old required to invoke the Fourteenth Amendment’s limi

tations. Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. I.18

In summary, the evidence leads to the inescapable con

clusion that these convictions are no less or more than

state enforcement of racial discrimination. The grand jury

presentment charging defendants with unlawful conspiracy

expressly recognized and relied upon T. C. A. §62-710 as

authorizing B. & W.’s racial discrimination as did the trial

judge in his instructions to the jury. This, added to the

use of police officials to arrest and state courts to crimi

nally punish petitioners solely to enforce a racial exclu

sion policy sanctioned by the state, in a restaurant licensed

by the State and open to the public, is such overwhelming

state participation in racial discrimination as to be clearly

prohibited by the Fourteenth Amendment to the Consti

tution of the United States.

18 In State of Delaware v. Brown, 195 A. 2d 379 (1963), the

Supreme Court of Delaware reversed trespass convictions against

Negroes who refused to leave a restaurant after being requested

to leave solely because of race and held that:

“ . . . Judicial action by the State to prosecute and convict

defendant for trespass would constitute an encouragement of

the actions of the proprietor in excluding defendant upon

racially discriminatory grounds. This the State cannot do.

As we have previously held, the owner or proprietor of a place

of public accommodation, with the exceptions noted, may not

be compelled by the State to accept patrons who are per

sonally offensive to him or his customers. It is equally true,

therefore, that the State may not compel the Negro patron

to leave the place of public accommodation. To do so would

place the weight of state power behind the discriminatory

action of the owner or proprietor.”

18

II.

These Convictions Deny Dae Process o f Law Because

Based on No Evidence o f the Essential Elements o f the

Crime o f Unlawful Conspiracy.

The indictment under which petitioners ~were charged

alleged that they:

. . . with force and arms, unlawfully, willfully, know

ingly, deliberately and intentionally, did unite, com

bine, conspire, agree and confederate between and

among themselves, to violate Code Section 39-1101-(7)

and Code Section 62-711, and unlawfully to commit

acts injurious to the restaurant business, trade or com

merce of Burrus and Webber . . .

In its opinion the Supreme Court of Tennessee stated:

Section 39-1101, T. C. A., makes it a misdemeanor for

two or more persons to conspire to do an unlawful

act. In order for the offense to be indictable, it must

be committed manu forti—in a manner which amounts

to a breach of the peace or in a manner which would

necessarily lead to a breach of the peace (App. 4a).

The court further stated that:

. . . Conspiracy may be inferred from the nature of

the acts done, the relation of the parties, the interest

of the alleged conspirators, and other circumstances;

and that such a conspiracy consists of a combination

between two or more persons for the purpose of ac

complishing a criminal or unlawful act, or an object,

which although not criminal or unlawful in itself, is

pursued by unlawful means, or the combination of two

19

or more persons to do something unlawful, either as

a means or as an ultimate end.10

At the time of arrest, petitioners were merely seeking

service at B. & W. in a peaceful manner. Of the numerous

witnesses at trial, not one testified to being unable to enter

or leave the cafeteria, nor did they see any other person

who was prevented from entering or leaving B. & W. while

petitioners were present. Most testified that they “had no

trouble getting in” (B.E. 888, 892, 1030-1031, 1038). No

witness testified that petitioners committed any disorderly

act or acts which constituted a breach of the peace. They

used no bad language and did not force themselves past

the doorman who held the door. Although petitioners were

told “we don’t serve colored people in here” and “you can’t

come in” (B.E. 1071), no one asked them to leave the

vestibule where they remained until they were arrested.

Two witnesses testified that petitioners were “pushing”

and “ shoving” (B.E. 917, 977). However, it was not es

tablished whether this pushing and shoving resulted from

the natural congestion in the vestibule caused by the door

man’s blocking the door or by petitioners’ actions alone.

Moreover, a few white patrons stated that they “pushed”

inside the vestibule . . . One man testified that he “kind

a pushed” his way in (B.E. 845) and another testified that

he “push[ed] my way through with my boy . . . I did

a little pushing” (B.E. 933).

is pior construction of Tennessee conspiracy statute see: Delaney

v. State, 164 Tenn. 432 (Persons must unite and agree to pursue

an unlawful enterprise) ; Aymett v. State, 310 S. W. 2d 460; Cline

v. State, 319 S. W. 2d 227 (gist of conspiracy is agreement to effect

unlawful end, but, before offense is complete, party to conspiracy

must commit some ‘overt act’. But cf. Smith v. State, 205 Tenn.

502 (overt act not required).

20

Petitioners were not “ugly” or “disrespectful” but were,

as one witness testified, “ just there” 20 (B.E. 799-800). No

witness testified that violence occurred or was even re

motely threatened. No rude remarks or gestures were

made either by petitioners or by any white persons in or

around B. & W.

More importantly, not a mite of proof was offered to

establish that petitioners conspired or agreed to obstruct

the passageway at B. & W. As already stated, not one wit

ness was prevented from entering or saw anyone else pre

vented from entering B. & W.,21 so clearly the passageway

was not blocked. And to the extent that it was congested,

this stemmed from the doorman’s barring the door.

20 One woman, however, testified that a defendant “ embarrassed”

and “humiliated” her (B.E. 976) because he allegedly called her

a “hypocrite.” On cross-examination she stated that the defendant

had said of all the people in the restaurant:

“Look at them sitting in there, supposed to be Christians, just

come from church, but they are just a bunch of hypocrites”

(B.E. 917).

21 Indeed, Patrolman Pyburn stated that when he arrived at

B. & W. four of the petitioners were standing on either side of the

door and there was ample room for him to enter (B.E. 1029).

Policeman Moran testified:

“ Q. When you arrived at B. & W. restaurant, what did you

do ?

A. We went over to the restaurant and seen four boys

standing on either side of the restaurant and I turned

around and went back to the car and called for our

superior officer” (B.E. 1024).

Moran further testified on cross-examination:

“ Q. And you went into the vestibule there? And you had

plenty of room to go in?

A. Yes, sir, but it was kind of hard to do without hitting

one of these boys with the door.

* * * * *

Q. Yes, what I mean is— you were able to get through it?

A. Oh, I could get through it, yes” (B.E. 1038).

21

There was no direct evidence of an agreement by peti

tioners to do anything. The only agreement reasonably

inferable from their conduct is that they agreed to go to

the restaurant and seek service—admittedly lawful con

duct.22 As there was no blocking of the doorway, there is

no basis for inferring an agreement to block the door. In

deed there is no indication that petitioners knew1 or could

have known that a doorman had been hired to keep them

out and would bar entrance to the door upon their arrival,

thus causing the congestion. The evidence utterly fails to

support the Supreme Court of Tennessee’s conclusion that

they employed unlawful means by obstructing the passage

way. Nor is argument required to show that the evidence

fails to support any finding of conduct either “ riotous,”

“ turbulent,” or likely to cause a “breach of the peace.” Yet

the Supreme Court of Tennessee found that there was suf

ficient proof of conduct “having the nature of a riot or

disturbance of the peace so as to warrant conviction” (App.

6a).

Not only, therefore, was there no evidence that peti

tioners conspired to commit an unlawful act, the record

solidly refutes the Supreme Court of Tennessee’s conclu

sion that the means employed were unlawful.

This case is not materially different from the ordinary

sit-in cases, where Negroes have been convicted for tres

pass after remaining at lunch counters when requested to

leave by restaurant owners, solely because of race. No

constitutional difference exists between sitting quietly on

22 The Supreme Court of Tennessee stated:

While the request for admittance by the defendants was not

criminal in the first instance, and while for the sake of argu

ment, we may even assume that they had a right to go on

the premises, the method they employed to effect their ad

mittance was clearly unlawful.

22

a lunch stool and standing quietly in a vestibule to protest

racial discrimination. This Court has found no problem

in reversing sit-in convictions based on no more evidence

than the Negroes’ “mere presence” at white restaurants.

Garner v. Louisiana, 368 U. S. 157. Here as in Garner,

the petitioners were not ordered to leave by the restau

rateur or his employees.

It has been recognized that a Negro sitting at a lunch

counter in a southern state to protect racial segregation is

engaged in a type of expression protected by the Four

teenth Amendment. Garner v. Louisiana, supra (Mr. Jus

tice Harlan, concurring). If, therefore, petitioners’ conduct

is construed to constitute an unlawful conspiracy, then the

statute under which they were charged and convicted is

unconstitutionally vague in that it failed to warn peti

tioners that it was unlawful to quietly remain in a cafeteria

vestibule and because, if so construed, it limits petitioners’

right of free expression. Garner v. Louisiana, supra;

Cantwell v. Connecticut, 310 U. S. 296; Winters v. New

York, 333 U. S. 507, 509.

Since the State offered no evidence of an agreement or

combination to commit any act, or of the commission of

any acts other than peaceably seeking equal food service

as Negroes in a restaurant licensed and regulated by the

State, open to the public and invested with the public in

terest, which acts the State is constitutionally proscribed

by the Fourteenth Amendment from declaring unlawful or

prohibiting through the exercise of State power, these con

victions rest on no evidence whatever and therefore deny

petitioners due process of law. Taylor v. Louisiana, 370

U. S. 154; Thompson v. Louisville, 362 U. S. 199.

III.

Petitioners Were Denied Due Process in That Their

Convictions Were Affirmed ©n a Ground Not Litigated

in the Trial Court.

The petitioners were tried and convicted under a grand

jury presentment which was drawn on the theory that the

B. & W. Cafeteria was legally entitled under Tennessee

law (§62-710) to exclude petitioners because of their race

(R. 10). The trial judge read the presentment and also

§62-710 to the jury (B.E. 1104-1107; 1110), and refused a

requested instruction that the cafeteria had no legal right

to exclude persons because of race (B.E. 1126).

However, the Tennessee Supreme Court purported to de

cide the case on the assumption “ for the sake of argument

that discrimination based on race by a facility such as this

cafeteria does violate the due process and equal protec

tion clauses” (App. 5a-6a). The court asserted that the

only question, given this assumption, was whether the

method that petitioners adopted was illegal (App. 6a). The

Supreme Court of Tennessee disposed of the claimed trial

error in refusing an instruction that the cafeteria had no

legal right to refuse service on the basis of race by saying

(App. 10a):

As we have heretofore said, this question is not the

issue in this case, and was not the basis of the indict

ment and conviction. Even if we assume that the

owner of the cafeteria had no right to exclude these

defendants, this does not excuse their conduct in block

ing this narrow passageway.

The fallacy of this reasoning is that the case was not

submitted to the jury on this basis. The jury received the

case on the theory that the petitioners had lawfully been

24

excluded from the B. & W. Cafeteria because of their race.

Thus, the affirmance of the conviction was based on a

theory directly contrary to that under which the petitioners

were charged and the case went to the jury. As this Court

said in Cole v. Arkansas, 333 U. S. 196, 201:

[If a state] provides for an appeal to the State Su

preme Court and on that appeal considers questions

raised under the Federal Constitution, the proceedings

in that court are a part of the process of law under

which the petitioners’ convictions must stand or fall.

Here, as in Cole, the State Supreme Court did not affirm

the “ conviction on the basis of the trial petitioners were

afforded.” The affirmance was on a theory directly con

trary to that under which the jury was instructed.

It is obvious that the jury might have reached a different

result if it had been instructed that the B. & W. Cafeteria

had no legal right to exclude petitioners because of race

and violated their rights when it did so. Further, the jury

was never instructed to consider the issue which the State

Supreme Court did decide, that is, whether petitioners’

method of seeming to vindicate their (assumed) right to

enter the cafeteria was unlawful. Thus, the conviction

clearly must be reversed under the holding of Cole v.

Arkansas, supra, at 202:

To conform to due process of law, petitioners were

entitled to have the validity of their convictions ap

praised on consideration of the case as it was tried

and as the issues were determined in the trial court.

It is submitted that the Tennessee Supreme Court’s dis

position of the petitioners’ appeal on grounds not con

sidered at the trial denied them due process.

25

IY .

Petitioners Were Denied Due Process in Violation o f

the Fourteenth Amendment When the Trial Judge In

structed the Jury That Petitioners Were Charged With

Violation o f a Statute When (a) Petitioners Had Not

in Fact Been Indicted for Violation o f the Statute and

(b ) It Was Not Even a Criminal Statute.

Petitioners were indicted for violating Section 39-1101(7)

and Section 62-711 of the Code of Tennessee. In his in

structions, however, the trial judge told the jury that peti

tioners were charged not only with violation of §39-1101(7)

and §62-711, but also that they were charged with a viola

tion of §62-710 (B.E. 1110-1111; 1116). Section 62-710,

which is not a criminal law at all, merely abrogates the

common law responsibility of innkeepers and other keep

ers of public places to serve all comers and gives them the

right to control the admission or exclusion of persons in

such places. It had been mentioned in the indictment, but

there was no indication that petitioners were charged with

violating it. But, after reading all three laws to the jury

the trial judge on two separate occasions told the jury

that the defendants were charged with violating §62-710

(B.E. 1110; 1116).23 Petitioners’ motion for new trial

23 The trial judge told the jury (B.E. 1110-1111) :

You will note from the language of the presentment that

the defendants are charged with the offense of unlawful con

spiracy to violate Code Section 39-1101(7), Code Sections

62-710 and 62-711, in that they did unlawfully commit acts

injurious to the restaurant business, trade and commerce of

Burrus & Webber Cafeteria, Inc., a corporation, located at

226 6th Avenue North, Nashville, Davidson County, Tennessee.

And also at B.E. 1116-1117 he said:

. . . If you find and believe beyond a reasonable doubt that

the said defendants unlawfully, wilfully, knowingly, deliber-

26

urging this as a denial of due process was overruled (E.

42-43).

The action of the trial judge in twice instructing the

jury that they could convict petitioners upon a charge not

made or even capable of being made, clearly violated peti

tioners’ rights to due process of law. In Stromberg v.

California, 283 U. S. 359, a conviction based on a general

verdict under a state statute was set aside because one

part of a statute submitted to the jury was unconstitu

tional. In Terminiello v. Chicago, 337 U. S. 1, the court in

instructing the jury about a city ordinance did so with a

theory which permitted conviction on an unconstitutional

basis.

Here, the statute which petitioners were alleged to have

violated is not even a statute under which one may be

criminally punished. Moreover, petitioners were never

charged with its violation. In DeJonge v. Oregon, 299 TJ. S.

353, 362, this court said: “ Conviction upon a charge not

made would be sheer denial of due process.”

The Supreme Court of Tennessee attempted to explain

away the manifest error of the trial judge by correctly

characterizing Section 62-710 as a civil statute abrogating

the common law, but this in no sense can be taken as a

ately, and intentionally did unite, combine, conspire, agree and

confederate between and among themselves, to violate Ten

nessee Code Section 39-1101-(7) and Code Sections 62-710 and

62-711, and unlawfully to commit acts injurious to the res

taurant business, trade and commerce of Burrus and Webber

Cafeteria, Inc., a corporation, located at 226 6th Avenue

North, Nashville, Davidson County, Tennessee, as charged in

the presentment, then it would be your duty to convict the

defendants; provided, that they, or one of them, did, in pur

suance of said agreement, or conspiracy, do some overt act

to effect the object of the agreement; that is, if you find that

said agreements and acts in the furtherance of said objective

were done in Davidson County, Tennessee.

27

cure of the fundamental evil involved here. By interject

ing provisions of law which not only confused the jury,

and which may have provided a basis for conviction not

present in Section 39-1101(7) and Section 62-711, the con

duct of the trial judge placed petitioners in jeopardy of

conviction upon a charge never made, under a law incapa

ble of sustaining a conviction, and for conduct not even

made criminal by state law. The Tennessee Supreme Court

acknowledged that this was error, but deemed it harmless

(App. 9a). The Court’s description of what occurred,

focused merely on the fact that the trial judge read §62-710

to the jury. But petitioners’ objection was that the judge

twice told the jury that they were charged with violating

§62-710, when this was not the case. Obviously this incor

rect instruction about what was charged may well have

affected the verdict and cannot be regarded as harmless.

Indeed it is difficult to conceive any more harmful instruc

tion than an incorrect statement of the crime charged.

The State Supreme Court’s statement that “ there were

no questions raised following the charge about the pro

priety of reading it [§62-710]” misses the mark on several

counts. First, the petitioners sought and were refused an

instruction contrary to the one given to the effect that not

withstanding §62-710, the restaurant had no right to ex

clude them (B.E. 1126). Secondly, they did object, by mo

tion for new trial to the reading of this statute (R. 42-43).

Thirdly, they also objected, on due process grounds, to the

trial judge’s misstatement of the offense charged, in the

motion for new trial (R. 43). Finally, there is nothing in

the opinion below to indicate that this objection came too

late. The stated ground of decision below was “harmless

error” and not any theory that the objection was not timely.

In any event there were no objections made to the instruc

tions given in Stromberg and Terminiello, supra.

V.

Petitioners Were Denied a Fair and Impartially Con

stituted Jury Contrary to Due Process of Law and Equal

Protection of the Laws Secured by the Fourteenth

Amendment to the United States Constitution.

Almost without exception, the white veniremen, including

some of the twelve persons who tried and convicted peti

tioners, upon extensive examination by petitioners’ coun

sel during voir dire, admitted a firm and life-long practice,

custom, philosophy and belief in racial segregation. Most

of the veniremen expressed belief that a restaurant owner

had a right to exclude anybody, including Negroes, from

his place of business.

Despite this fact, the trial judge in every instance over

ruled petitioners’ challenges for good cause and held cer

tain white jurors competent. For instance, Herbert Amick

was held competent by the trial court over petitioners’ chal

lenge after testifying:

Q. But you think that a business open to the public

should be allowed to exclude Negroes?

A. If they so desire, yes.

Q. A restaurant business, then specifically,—in par

ticular? And having that opinion where in the indict

ment in this case charges that the B & W Cafeteria

had had such a rule, and that these defendants went

there and sought service, knowing that the B & W

had such a rule and then you would start out with a

prejudiced attitude toward these defendants?

A. Well, I would—

Q. By reason of your belief?

A. I would believe the B & W would be right in this

case on their position.

29

Q. And yon would start—what I am saying, though

is you would start out in this case with a prejudiced

attitude toward the defendants, wouldn’t you!

A. In this particular case, I imagine I would (B.E.

452-453).

Similarly, the trial court held competent other jurors,

over petitioners’ objections for cause, who testified that

their entire lives and all their personal associations had

been on a segregated basis without any contact with

Negroes on a basis of equality (B.E. 665-669, 756, 759).

In the case at bar, where the very issue to be tried was

the right of a restaurateur to exclude persons on the basis

of race, the trial judge’s failure to exclude these jurors

with admittedly preconceived notions against Negroes and

in favor of B. & W.’s practice of racial segregation, was

highly prejudicial and denied petitioners’ right to trial by

a fair and impartial jury.

This Court has repeatedly recognized that “ the Ameri

can tradition of trial by jury, considered in connection

with either criminal or civil proceedings, necessarily con

templates an impartial jury drawn from a cross-section of

the community.” Smith v. Texas, 311 U. S. 128, 130;

Glasser v. United States, 315 U. S. 60, 85; Thiel v. South

ern Pacific Co., 328 U. S. 218, 220. This Court has also rec

ognized that racial prejudice is a valid ground for disquali

fication of a juror, Aldridge v. United States, 283 U. S.

308. In Aldridge it was said:

. . . [T]he question is not as to the civil privileges

of the Negro, or as to the dominant sentiment of the

community and the general absence of any disqualify

ing prejudice, but as to the bias of the particular

jurors who are to try the accused. If in fact, sharing

the general sentiment . . . one of them was shown to

30

entertain a prejudice which would preclude his ren

dering a fair verdict, a gross injustice would he per

petrated in allowing him to sit (283 U. S. at 314).

It is clear that the jurors described above and declared

competent by the trial court were incapable, by virtue of

their segregationist beliefs, to render petitioners a fair

and impartial verdict and that their presence as jurors

prejudiced petitioners’ right to an unbiased trial. Such

action denied due process as well as equal protection of

the laws. The test established in Aldridge, supra, is more

than met here.

CONCLUSION

Wherefore, it is respectfully submitted that the petition

for certiorari should be granted.

Respectfully submitted,

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. Nabrit, III

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

A von N. W illiams

Z. A lexander L ooby

McClellan-Looby Bldg.

Charlotte at Fourth

Nashville, Tennessee

Attorneys for Petitioners

APPENDIX

APPENDIX

Davidson Criminal

H on. J ohn L. Draper, Judge

Lester G. McK innie, Nathal W inters, J ohn R. L ewis,

H arrison D ean, F rederick L eonard, A llen Cason, Jr.,

J ohn Jackson, J r., and F rederick Hargraves,

State of T ennessee.

For Plaintiffs in Error:

Looby & Williams

Nashville, Tennessee

For the State:

Thomas E. Fox

Assistant Attorney General

Opinion

The plaintiffs in error were convicted of conspiring to

injure the business of the B & W Cafeteria by blocking

the entrance thereto in the event they were denied entrance

to and service in said cafeteria. The jury recommended a

line of less than $50.00. The trial judge sentenced each of

these defendants to ninety days in the Davidson County

workhouse and lined each of them $50.00. An appeal was

seasonably perfected, able briefs filed, and oral arguments

were heard, and, after a thorough study of the record and

applicable authorities, we now have the matter for dis

position.

2a

The indictment alleges a violation of two sections of the

Tennessee Code, §39-1101 (7), T. C. A., and §62-711,

T. C. A. The pertinent part of §39-1101, T. C. A., is as

follows:

“The crime of conspiracy may he committed by any

two (2) or more persons conspiring: . . . (7) to com

mit any act injurious to public health, public morals,

trade, or commerce . . . ”

Section 62-711, T. C. A., provides, in part, that “any

person guilty of turbulent or riotous conduct within or

about” any hotel, inn, restaurant, etc., is subject to in

dictment and a fine of not less than $100.00. Section 62-710,

T. C. A., was also mentioned in the indictment and the

trial court’s charge, but the defendants were not charged

with violating this Section of the Code; nor could they

have been so charged since this Section does not purport

to define an indictable offense. It was mentioned merely

to indicate that the B & W Cafeteria was permitted, by

statute, to refuse admittance to any person whom it did

not desire to serve.

There are thirteen assignments of error. They will not

be taken up seriatim, but all of them will be treated and

answered in the course of this opinion.

At about 12:20, P.M., Sunday, October 21, 1962, just

after many church services had ended, and at a time when

the patrons of the B & W Cafeteria were arriving for

lunch, the defendants appeared at the entrance of the

cafeteria which is located on Sixth Avenue, in the heart

of Nashville, Tennessee. When they arrived, they were

informed by the doorman that the cafeteria did not serve

colored people and that they could not enter. Despite this,

Opinion

3a,

the defendants remained at the entrance to the cafeteria

and insisted that, “We are coming in and are going to

eat when we git in.”

The defendants were asked in a polite way to move

along and to refrain from making any trouble. At this

time, they had entered a vestibule to the cafeteria, the

size of which is estimated as being from four feet by four

feet to six feet by six feet and four inches. The defendants

were in the vestibule, but were not permitted to enter the

main part of the restaurant. After the defendants refused

to remove themselves from the vestibule and after the acts

hereinafter set forth had been committed, the police were

called and they escorted the defendants away.

In considering the evidence hereinafter briefly summa

rized, we must remember that, in this State, fact deter

minations and reasonable inferences to be drawn therefrom

are for the trier of facts, in this case the jury. On a review

of a judgment of conviction, if there is material evidence

to support the judgment, the defendants are presumed to

be guilty and this Court will not reconsider the question

of whether or not the evidence shows that they are guilty

beyond a reasonable doubt; but will consider only the

question of whether the evidence preponderates against

their guilt and in favor of their innocence. Smith and

Reynolds v. State, 205 Tenn., 502, 327 S. W. 2d, 308 (1959),

certiorari denied by the Supreme Court of the United

States, 361 U. S., 930, 80 S. Ct,, 372, 4 L. Ed. 2d, 354

(1960).

The record clearly shows that these defendants physi

cally blocked the entrance to the B & W Cafeteria by

placing themselves in this small vestibule so as to prevent

people from entering or leaving; and that entrance to and

exit from the restaurant was not possible without squeezing

Opinion

4a

and worming through the wall of flesh created by the

defendants’ presence and position. The evidence likewise

shows that in blocking this entrance, the defendants were

pushing and shoving to some extent in an effort to enter

this restaurant, but were prevented from doing so because

the doorman kept the inner door closed to them. For

example, one of the State’s witnesses testified about the

situation as follows:

“ Well, it was still blocked and people inside couldn’t

get out. And you could see the crowd outside—wasn’t

coming in. And it just seemed like an awfully long

time till the—under the circumstances—it wasn’t too

long—while that state of confusion existed. . . . ”

A number of other witnesses testified to this state of

facts and as to things they heard while they were trying

to get in or out of the restaurant. Probably under the

record, one or two white people did squeeze their way

either in or out while all of this was going on, but never

theless these defendants refused to vacate the vestibule

until they were peacefully escorted away by the police.

The record clearly shows that after the vestibule was

cleared, the people inside the restaurant were able to go

out and the people outside the restaurant were able to

enter. There is also proof that there were as many as

seventy-five people on the outside attempting or wanting

to get in while these defendants were in the vestibule.

Section 39-1101, T. C. A., makes it a misdemeanor for

two or more persons to conspire to do an unlawful act.

In order for the offense to be indictable, it must be com

mitted mcmu forti—in a manner which amounts to a breach

of the peace or in a manner which would necessarily lead

Opinion

5a

to a breach of the peace. The charge here, as it is clearly

set forth in the indictment, is that the defendants crowded

into this small vestibule and through their actions, as de

tailed above, committed an act injurious to trade and com

merce. When two or more persons conspire to commit

an act such as this, §39-1101, T. C. A., provides that they

shall be guilty of a conspiracy. Section 62-711, T. C. A.,

in part provides that when a person is guilty of turbulent

or riotous conduct within or about restaurants, hotels, etc.,

he may be indicted and fined not less than $100.00. One

of the questions raised by the defendants is whether the

indictment in this case sufficiently describes the offense to

meet the requirements of §40-1802, T. C. A., which provides

that the indictment must state the facts in ordinary and

concise language so as to enable a person of common un

derstanding to know what was intended, etc. Clearly, the

indictment in this case, which consists of over a legal page

in 10 point type, informs each of the defendants of the

conduct for which he has been indicted, and the statutes

which the State contends that such conduct has violated.

The defendants through various motions and throughout

the trial attempted to say that this prosecution was brought

for the purpose of enforcing a rule of segregation or racial

exclusion in facilities licensed by the State, open to the

public, and vested with public interest; and that such a

prosecution is contrary to the due process and equal pro

tection clauses of the 14th Amendment to the Constitution

of the United States. From a very careful examination

and reading of the record, the indictment, and the charge

of the court, we certainly feel that such questions are

not determinative of this prosecution. We can assume for

the sake of argument that discrimination based on race

by a facility such as this cafeteria does violate the due

Opinion

6a

process and equal protection clauses, but these questions

are not presented here. A careful reading of this record

shows that the only question is whether or not these de

fendants were attempting, in an illegal manner, to correct

what they deemed to be an unconstitutional practice on the

part of this cafeteria; and, if the method which these de

fendants adopted was illegal, whether it constitutes a mis

demeanor under the Sections of the Code under which they

were indicted.

This Court long ago in State v. Lasaler, 68 Tenn., 584

(1877), held that an indictment under §62-711, T. C. A.,

was good and that the act was constitutional. In that case,

a judgment quashing the indictment was reversed where

the indictment alleged that the defendant had been guilty

of turbulent and riotous conduct within and about a hotel

by quarreling, committing assaults and batteries, breaches

of the peace, loud noises, and trespass upon a hotel. It

seems to us that there is sufficient proof in the instant case,

which the jury apparently believed, to warrant the con

viction under this Section. The word “ riotous” is defined

by Webster’s New World Dictionary as “having the nature

of a riot or disturbance of the peace.” The conduct of the

defendants certainly meets this definition. Nowhere in this

record is it insisted that there was not a prior agreement

to engage in such conduct if entrance to this restaurant

was denied. In Smith and Reynolds v. State, supra, this

Court had occasion to define a criminal conspiracy. This

definition seems to meet the situation here. We likewise

held in the Smith and Reynolds case that a conspiracy

may be inferred from the nature of the acts done, the

relation of the parties, the interest of the alleged con

spirators, and other circumstances; and that such a

conspiracy consists of a combination between two or more

Opinion

Opinion

persons for the purpose of accomplishing a criminal or

unlawful act, or an object, which although not criminal

or unlawful in itself, is pursued by unlawful means, or the

combination of two or more persons to do something un

lawful, either as a means or as an ultimate end. While

the request for admittance by the defendants was not crim

inal in the first instance, and while for the sake of argu

ment, we may even assume that they had a right to go on

the premises of the restaurant, the method they employed

to effect their admittance was clearly unlawful.

It is very earnestly and ably argued by counsel for the

defendants that to prevent the defendants from acting as

alleged in the indictment would constitute a denial of

freedom of speech in contravention of the 1st Amendment

to the Federal Constitution as made applicable to the

States through the 14th Amendment. Of course, in this

country, a person has a right to speak freely and a denial

of this right offends our heritage of freedom. The indi

vidual must feel free to speak his mind; the press must

be free to publish its opinion; and the movies must be

free to express their views. There are literally hundreds

of different agencies to whom freedom of expression is

guaranteed. But around such freedoms there must be cer

tain safeguards for the protection of society and when

these safeguards are violated, the violator is subject to

civil or criminal sanctions or both. Thus one cannot be

allowed to recklessly shout “ fire” in a crowded theatre.

In crowding into this narrow vestibule and effectively

blocking the entrance to this restaurant, the defendants

interfered with the right of other individuals to come and

go in the furtherance of trade and commerce and in so

doing they violated the Sections of the Code hereinbefore

set forth. See Feiner v. New York, 340 IT. S., 315, 71 S. Ct.,

303, 95 L. Ed., 295 (1951).

8a

Had this been a labor dispute, the actions of the de

fendants would clearly be beyond that of peaceful picket

ing, which does not include in its definition any form of

physical obstruction or interference with business. It is

well established that labor has the right to peacefully

picket and thereby express its views on the subjects in

volved in a labor dispute. But the picketing must be

peaceful. When it goes beyond the peaceful stage and

involves force, violence, threats, terror, intimidation, coer

cion and other things of like kind, it cannot be tolerated

and those persons guilty of such acts are subject to state

and federal laws. By analogy, if the conduct of the defen

dants here transcended the bounds of peaceful picketing,

they would, under the evidence in this record, be guilty of

acts injurious to trade. We think that their conduct clearly

goes beyond the bounds of peaceful demonstration and

picketing.

It is very forcefully insisted that the two Sections of

the Code under which this indictment was laid should have

been declared unconstitutional because they do not clearly

and sufficiently define the offense charged against the de

fendants. In all the years that these Code Sections have

been the law in this State, this question has not been

raised as far as we can determine. As far as we know,

there is no criminal statute which describes every specific

kind of violation that might be indictable under it; but

so long as the statute generally states, as these statutes

do, what is prohibited, their constitutionality cannot be

challenged for indefiniteness. We think that the statutes

now under consideration clearly set forth the offense in

tended and that the indictment framed thereunder clearly