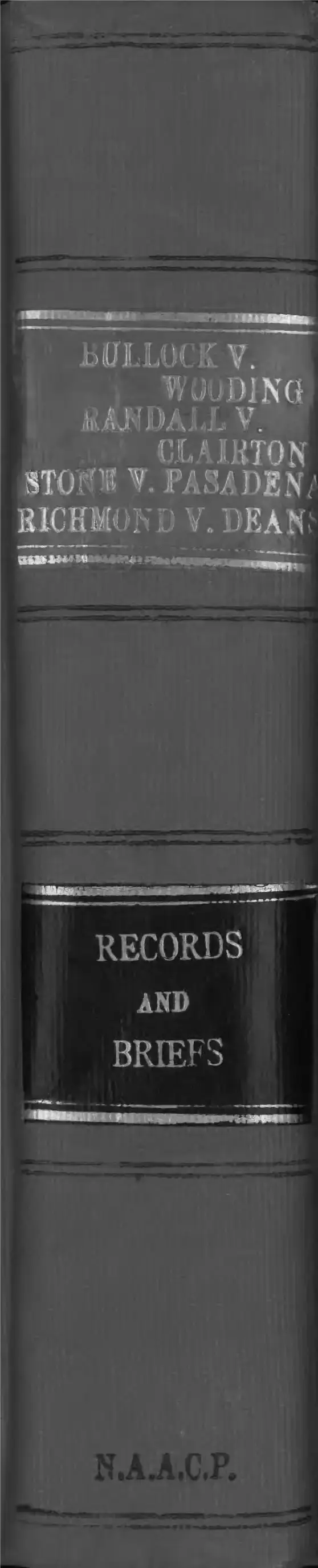

Bullock v. Wooding, Randall v. Clairton, Stone v. Pasadena, and Richmond v. Deans Records and Briefs

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1929 - January 1, 1939

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Bullock v. Wooding, Randall v. Clairton, Stone v. Pasadena, and Richmond v. Deans Records and Briefs, 1929. f69c68e0-c99a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/7cd90aaa-5926-4ca2-bb01-f281f2135c0a/bullock-v-wooding-randall-v-clairton-stone-v-pasadena-and-richmond-v-deans-records-and-briefs. Accessed February 03, 2026.

Copied!

JdO'LLOCK V.

W UODINQ

iSiiiJ'IJDAj: ,A V.

OF/J.RTON

STOr'M FA Si DEN 1

R I C H I E V . DEAN

RECORDS

AND

BRIEFS

£frw Iferawj Stuprme (Enurt

ALLIE BULLOCK,

Prosecutrix,

vs.

J. ARTHUR WOODING, Clerk of the City

of Long Branch, New Jersey, and the

CITY OF LONG BRAN CH / County of

Monmouth, New Jersey,

Defendants.

On

Certiorari.

STATE OF CASE.

\

UPPERMAN AND YANCEY,

Attorneys for Prosecutrix.

ROBERT S. HARTGROVE,

Of Counsel for Prosecutrix.

LEO J. WARWICK,

Attorney for Defendants.

Arthur W. Cross, Inc., Law Printers, 71-73 Clinton Street, Newark, N. J.

INDEX

PAGE

Petition ........................................................ 1

Exhibit 1, Ordinance Annexed to Petition 8

Registration Card Annexed to Petition. . 12

Affidavit of Allie Bullock Annexed to

Petition .................................................... 13

Affidavit of Harry Friedman Annexed to

Petition ..................... 14

Notice of Application..................................... 15

Stipulation of Continuance............................. 17

Writ of Certiorari............................................ 18

Allocatur ...................................................... 19

Return to W rit................................................ 20

Ordinance Annexed to Return................... 21

Amended Ordinance Annexed to Return 25

Registration Card Annexed to Return. . . 29

Reasons ........................................ 30

Affidavit of Stenographer............................... 34

Testimony ........................................................ 35

Certificate of Supreme Court Commissioner 102

W itnesses pok P ro secu trix .

J. Arthur Wooding,

D irect ................................................ 36

Cross ................................................ 64

Re-direct .......................................... 71

Re-cross ............................................ 76

11

PAGE

Virginia Audrey Flowers,

D irect ................................................. 62

Cross ................................................ 63

Mrs. Anna Mumby,

D irect................................................ 81

Cross ................................................ 83

Mrs. Allie Bullock,

D irect................................................ 86

Cross ............. 88

Reverend Lester Kendall Jackson,

Direct ......................... 93

Cross ................................................ 95

Re-direct ........................................... 97

Jeanette Sample,

D irect................................................ 97

Cross ................................................ 99

Dr. Julius C. McKelvie,

Direct ................................................ 100

Cross ................................................ 102

E x h ib it s .

A dm itted P rin ted

at P age at Page

P-1—Ordinance, June 6, 1933............ 37 37

P-2—Amended Ordinance, June

7, 1938 ....................................... 37 40

P-3—Application of Harold Fried

man 60 60

Petition.

dkxrm] Buynnw Okurt

J. A r t h u r W ooding , Clerk of the

City of Long Branch, New

Jersey, and the C it y of L ong

B r a n c h , New Jersey,

A ll ie B u l l o c k ,

vs.

Prosecutrix,

Defendants.

On Certiorari.

Petition.

10

To the Honorable Thomas J. Brogan, Chief

Justice of the New Jersey Supreme Court:

The petition of Allie Bullock respectfully shows

unto Your Honor that:

1. She is a citizen of the City of Long Branch,

a resident of the City of Long Branch, County of

Monmouth and State of New Jersey, and has re

sided in said City of Long Branch and at number

439 Hendrickson Avenue for the past thirteen

years.

2. The said prosecutrix is a Negro and a mem

ber of the Colored race.

3. Prosecutrix’ husband, William L. Bullock,

with whom prosecutrix resides and at all times

hereinafter mentioned, is a property owner and a

taxpayer in the said City of Long Branch. 4

4. On June 7, 1938, the Board of Commission

ers of the said City of Long Branch passed an 40

30

2

ordinance to amend an ordinance entitled, “ An

Ordinance providing for the maintenance and

regulation of bathing beaches in the City of Long-

Branch and authorizing the imposition by the

Board of Commissioners of the City of Long

Branch or their duly authorized agent of fees

10 for the use of said beaches, ’ ’ passed June 6, 1933.

5. A certified copy of the ordinance as

amended and as to which prosecutrix complains,

is annexed to this petition and made a part

thereof.

6. Under the operation and exercise of the said

amended ordinance the said City Commissioners

of the said City of Long Branch and/or the City

20 Clerk of the said City divided that portion of the

beach front of the Atlantic Ocean, embraced

within the said limits of the said city and oper

ated by it, into four segments or parts for bath

ing facilities, said segments or parts being dis

tinctly marked and distinguished as Beach No. 1,

Beach No. 2, Beach No. 3 and Beach No. 4.

7. On Sunday, July 17, 1938, at about 1:45

o ’clock in the afternoon of that day prosecutrix

30 in the City Hall of Long Branch made application

to the City Clerk for the registration of her name

and for a badge for the purpose of using the bath

ing facilities at the Long Branch Beach. At the

time that the prosecutrix made the application as

aforesaid, she was given a registration card, a

copy of which is hereto annexed and made a part

of this petition. After the execution of the said

registration card she tendered to the said City

Clerk, J. Arthur Wooding, a fee of one dollar

40 ($1.00) as required by the said amended ordi-

Petition.

3

nance, requesting of him at the same time that

she be given a badge for bathing facilities for

Beach No. 1. After making the request as afore

said the said City Clerk refused to receive your

petitioner’s application and the one dollar ($1,00)

as tendered to him and as aforesaid, and also re

fused to issue to her a badge or permit for Beach

No. 1.

8. At the time that the said J. Arthur Wood

ing, Clerk as aforesaid, refused to accept the ap

plication of prosecutrix and as above set forth,

he stated to her that he had received orders and

directions from the Mayor of the City of Long

Branch that no badges or permits should be is

sued to Colored people for any of the beaches as

aforesaid except Beach No. 3.

9. After prosecutrix had made application for

a badge for use of Beach No. 1 and as aforesaid

the said City Clerk of Long Branch issued beach

badges for bathing facilities to many other per

sons and of the White race for use of Beach No. 1

and for use of Beach No. 2 and Beach No. 4.

10. The residence of prosecutrix and as afore

said is so geographically situated that it is closer

to Beach No. 1 for which she had applied for bath

ing facilities as aforesaid than to Beach No. 3.

11. At various times since the enactment and

adoption of the said amended ordinance the said

City Clerk of Long Branch, acting under the guise

and pretense of preventing congestion upon the

said beaches, has refused to sell to persons of the

Colored race badges or permits for any of the

beaches except Beach No. 3. At the time that

Petition.

10

20

30

40

4

these refusals were made and as aforesaid there

were no congestions upon any of the beaches and

the said City Clerk at these times was selling

badges for Beaches Numbers 1, 2 and 4 exclu

sively to members of the White race.

10 12. The said City Hall of the said City of Long

Branch where the badges or permits are issued

to patrons, is located at a distance of one mile

from the said beaches of Long Branch.

13. The prosecutrix has been informed and

verily believes that the purpose of the amended

ordinance as above set forth, and the practice

thereunder, are to restrict, segregate and forbid

the use of any of the said beaches under consider-

20 ation by members of the Colored race except

Beach No. 3 and as above set forth.

14. Prosecutrix is informed and verily be

lieves that, as a resident and citizen of the said

City of Long Branch, and as above set forth, she

is interested in the conditions created by the said

amended ordinance, and that she is entitled to

any and all equal rights, advantages and privi

leges of any citizen of the said City of Long

30 Branch or of the State of New Jersey, irrespec

tive of color or race.

15. Prosecutrix is informed and verily believes

that the enactment of the aforesaid amended ordi

nance, and the acts of the said Clerk of the City

of Long Branch as above set forth, are illegal,

void and are and were in excess of jurisdiction in

that:

(a) The said amended ordinance was not

40 legislation for the common good, interest,

health or safety of the community of the said

City of Long Branch.

Petition.

(b) The said amended ordinance was leg

islation for the benefit of a class.

(c) The said amended ordinance was an

attempt to legislate as to the private rights

of the prosecutrix and by the Citv of Long

Branch as to the use of the public beaches

of the City of Long Branch and the waters

of the Atlantic Ocean, notwithstanding such

rights should be determined and can be deter

mined only by judicial proceedings under

public statute.

(d) The said amended ordinance is an at

tempt by legislation to abate a public nuis

ance, and also an attempt to provide a sum

mary proceedings, in the nature of a criminal

proceedings, to try and adjudicate what would

otherwise be an indictable offense, and thus

deprive the prosecutrix of her right to indict

ment and trial by jury.

(e) The said amended ordinance is in con

flict with the general laws of the State of

New Jersey.

(f) The said amended ordinance is in con

flict with the Civil Rights Act of the State of

New Jersey in it denies to the prosecutrix

and other members of the Colored race, as

well as all persons within the jurisdiction of

the State of New Jersey, the full and equal

accommodations, advantages, facilities and

privileges to the public beaches of the City

of Long Branch, and the public bath houses

thereon.

(g) The said amended ordinance intro

duces a policy contrary to and at variance

with the public policy of the State of New

Jersey.

5

Petition.

10

20

30

40

10

20

30

40

6

(h) The said amended ordinance is a dele

gation of the legislative powers of the gov

erning bodies of the municipality to an agent

thereof.

(i) The said amended ordinance, as a

revenue measure, is discriminatory and illu

sory.

(j) The said amended ordinance, as a rev

enue measure, is detrimental to the financial

welfare of the said City of Long Branch.

(k) The said amended ordinance, as a rev

enue measure, is an unlawful delegation of

the taxing power of the governing body of

the City of Long Branch to the City Clerk

or an agent thereof.

(l) The said amended ordinance is unrea

sonable, arbitrary, uncertain and indefinite

in its terms, operation and exercise.

(m) The said amended ordinance vests in

a municipal agent, to wit, the City Clerk,

powers arbitrary and oppressive, and a dis

cretion to prevent private citizens of the City

of Long Branch, State of New Jersey, from

the use of the beach and the waters of the

Atlantic Ocean.

(n) The said amended ordinance gives no

right of appeal from the exercise of the arbi

trary or discretionary powers by the said

City Clerk of Long Branch.

(o) The said amended ordinance provides

no procedure for the prosecutrix or any ap

plicant to obtain a badge or permit for the

use of the bathing facilities and access to the

said beaches.

Petition.

7

(p) The said amended ordinance is viola

tive of the rights of the prosecutrix as set

forth by the Constitution of the State of New

Jersey, and the Fourteenth Amendment to

the Constitution of the United States of

America.

(q) The said amended ordinance is vio

lative of the Laws of the State of New Jer

sey, to wit, the so-called Home Rule Act, as to

the penalty which it seeks to impose upon the

prosecutrix or any other person violating any

of the terms of the said amended ordinance.

W h erefo re , the premises considered, the prose

cutrix, Allie Bullock, prays that a rule issue out

of the Supreme Court of New Jersey directing

and commanding J. Arthur Wooding, City Clerk

of the City of Long Branch, to show cause why

a writ of certiorari should not issue out of the

said Supreme Court of New Jersey to test the

legality of the said amended ordinance as above

set forth and the acts thereunder of the said City

Clerk of the said City of Long Branch and as

above set forth.

And that the said prosecutrix might have any

and all other relief that might be legal and just.

And the said prosecutrix will ever pray, &c.

A llie B u l l o c k ,

Prosecutrix.

W alter J. U p p e r m a n ,

R oger M. Y a x l e y ,

Attorneys for Prosecutrix.

R obert S. H artgrove,

Of Counsel for Prosecutrix.

Petition.

10

20

30

40

8

I , J. A r t h u r W ooding do certify that the fol

lowing is a true copy of Ordinance passed June

7th, 1938.

J. A r t h u r W ooding ,

(Seal) City Clerk.

10

A n O rd in a n c e to amend an ordinance entitled:

“ An Ordinance providing for the maintenance

and regulation of bathing beaches in the City of

Long Branch and authorizing the imposition

by the Board of Commissioners of the City of

Long Branch or their duly authorized agent of

fees for the use of said beaches,” passed June 6,

1933.

20 The Board of Commissioners of the City of

Long Branch Do O rdain :

Section 1. That Section 2 of the above entitled

ordinance be and the same is hereby amended so

that it supersedes the present Section 2 in said

ordinance and shall read as follows:

Section 2. For the government, use and opera

tion of said public beaches the following rules and

regulations shall be in force and effect and the

fees hereinafter provided for shall be imposed and

charged:

1. All persons desiring the use of the bathing-

facilities and access to said beaches shall register

in the City Clerk’s Office, City Hall, and upon

paying the fee or charge as hereinafter provided,

shall receive from the City Clerk a badge, check or

other insignia which shall be worn by the regis

trant when required, or shall be shown at the re-

quest of any officer or employee of the City of

Exhibit 1 Annexed to Petition.

9

Long Branch. A11 badges, checks or other in

signia and all written evidence of the right to use

said beaches shall not be transferable.

2. For the purpose of avoiding congestion on

any of said beaches, and for a proper distribution

of patrons, and for the better protection and

safety of patrons on said beaches, the City Clerk

is authorized and directed to issue badges, checks

or other insignia of distinctive design or color for

the use of each of the respective beaches.

3. The said fees hereinafter provided for shall

entitle said registrant to said use for a period of

not less than ten weeks beginning not before June

15th and ending not later than October 1st, of each

year, as the period for use shall be from time to

time determined by the Director of the Depart

ment of Parks and Public Property, subject, how

ever, to the direction of the Board of Commis

sioners of the City of Long Branch.

4. All permits, licenses or other rights and

privileges to use said bathing facilities shall be

subject to such regulations as are now in force or

which may hereafter be made during the period

covered by such permit.

5. The Board of Commissioners may by reso

lution adopt such additional rules and regulations

for the .government, use and policing of such

beaches and places of recreation not inconsistent

with the provisions of this ordinance.

6. F e e s : There shall be charged for the use

of the bathing facilities and access to said recrea

tional grounds the following fees:

Exhibit 1 Annexed to Petition.

10

20

30

40

10

Exhibit 1 Annexed to Petition.

Bona fide residents of the City of Long

Branch per season.....................................$ 1.00

Guests of residents (not more than two

guests per day) for each guest, plus a de

posit of 50c per badge.......................................50

10 Non-residents, seasonal perm it.................... 3.00

Where bathing house facilities are provided

bath house for not more than five persons,

per season .................................................. 25.00

Section 2: That Section 4 of the above entitled

ordinance be and the same is hereby amended so

that it supersedes the present Section 4 of said

ordinance, and shall read as follows:

20 Section 4: All persons residing in a charitable

institution or institutions in the City of Long

Branch shall be entitled to enter upon that part of

the bathing beaches in this ordinance described

or in the waters adjacent thereto, as shall be from

time to time designated by the Director of the De

partment of Parks and Public Property of the

City of Long Branch for that purpose without

charge.

The City of Long Branch shall comply with all

30 the laws regarding the safety of bathers and shall

provide all such safety devices for bathers as are

required by the laws of New Jersey and particu

larly shall keep and observe all the provisions of

Chapter 174 of the Acts of the Legislature of the

State of New Jersey for the year 1900, and upon

the failure to do so the Director of the Depart

ment of Parks and Public Property may close

said beaches or any part thereof and the Director

of the Department of Parks and Public Property

40 may at any and all times close said beaches and

11

forbid bathing thereon because of storm or condi

tions of the beaches or ocean which may be deemed

dangerous for bathers.

All expenses and costs to the City of Long

Branch in carrying out the terms of this ordinance

shall be paid from the appropriations made in the

budget of the City of Long Branch, for the cur

rent year for this purpose.

All fees and income from the operation of said

beaches shall be collected by the City Clerk and

transmitted to the Treasurer of the City of Long

Branch to become the property of the City of

Long Branch. All matters relating to the use and

administration of said beaches are hereby com

mitted to the Director of the Department of Parks

and Public Property subject, however, to the pro

visions of this ordinance and such rules and regu

lations as may hereafter be duly adopted by the

Board of Commissioners of the City of Long

Branch.

All persons violating any provisions of this

ordinance shall upon conviction before the Re

corder or other officer having jurisdiction forfeit

and pay a tine not exceeding $50.00 for each of

fence and in default of payment of such fine shall

be imprisoned in the County Jail for a term not

exceeding 30 days in the discretion of the Re

corder or Police Magistrate.

Introduced May 24, 1938.

Passed June 7, 1938.

A lto n V . E vans

W alto n S h e r m a n

F r a n k A . B razo

Commissioners.

Attest:

J. A r t h u r W ooding,

City Clerk.

Exhibit 1 Annexed to Petition.

10

20

30

40

12

Registration Card Annexed to Petition.

P u b lic N otice

The foregoing ordinance was finally passed by

the Board of Commissioners of the City of Long

Branch, New Jersey, on the seventh day of June,

1938.

Dated Long Branch, N. J., June 7, 1938.

J. A r t h u r W ooding,

City Clerk.

Registration Card Annexed to Petition.

B a t h in g R egistration R esiden t

20 C it y of L ong B r a n c h

NEW JERSEY

Badge No....................... Date.................................

Name ..........................................................................

Address ......................................................................

In accordance with an ordinance of the City of

Long Branch regulating the use of the bathing

beaches of the City of Long Branch by bathers, I

represent that I am a bona fide resident of the

3 0 City of Long Branch, and I herewith make appli

cation for bathing privileges for the season of

1938, and herewith pay the fee of One Dollar

($1.00) for the same. I agree to abide by the

rules and regulations set forth in the said ordi

nance and assume all risks incident thereto.

Signature of Applicant.

40

13

S tate of N e w J ersey , 1

7 SS. I

C o u n t y of M o n m o u t h , ^

A llie B u l l o c k , residing at 439 Hendrickson

Avenue, in the City of Long Branch, county and

state aforesaid, being duly sworn upon her oath, jq

deposes and says:

1. I am the prosecutrix named in the foregoing

^petition and am a citizen of the City of Long

Branch, State of New Jersey, having resided in

the said City of Long Branch for thirteen years

last past.

2. I have read the contents of the said fore

going petition and as to the matters and facts 20

therein set forth, I swear the same to be true just

as fully and to the same extent as if the same

were herein set forth; and as to the matters and

facts therein set forth upon information and be

lief, I believe the same to be true just as fully and

to the same extent as if they were herein set forth.

A llie B u l l o c k .

Subscribed and sworn to before me )

this 20th day of August, 1938. ̂ ^

I rvin g R. W ebster ,

Notary Public of New Jersey.

My Commission Expires April 15, 1942.

Affidavit of Allie Bullock Annexed to Petition.

40

14

S tate of N e w J eesey ,

C o u n t y of M o n m o u t h .

H arky F r ie d m a n , of full age, being duly sworn

according to law upon his oath deposes and says:

10

1. He is a resident of the City of Long Branch,

residing at No. 156 Union Avenue, Long Branch,

New Jersey, and is a member of the Caucasian or

White race. *

2. On Sunday, July 17th, 1938, at about 1:50

o ’clock in the afternoon of that day he appeared

at the office of the Clerk of the City of Long

Branch, registered, tendered a fee of One Dollar

2o and asked for a badge for Beach No. 4. He was

given a badge for Bathing Beach No. 4, and re

turned about one half hour later and exchanged

said badge for a badge for Beach No. 1, known as

the North Long Branch Beach.

3. Deponent further says that his place of

residence geographically is situated at a greater

distance from Beach No. 1, known as the North

Long Branch Beach, than the home of Allie Bul-

lock who resides at No. 439 Hendrickson Avenue.

H arry F r ie d m a n .

Subscribed and sworn to before me J

this 20th day of August, 1938. j

I rving R. W ebster ,

Notary Public of New Jersey.

My Commission Expires April 15, 1942.

Affidavit of Harry Friedman Annexed to Petition.

40

15

Notice of Application.

NEW JERSEY SUPREME COURT.

J. A r t h u r W ooding, Clerk of the

City of Long Branch, New

Jersey, and the C it y or L ong

B r a n c h , New Jersey,

A llie B u l l o c k ,

vs.

Prosecutrix,

Defendants.

On Certiorari.

Notice of

Application.

On Petition. 10

To the City Commissioners of Long Branch,

J. Arthur Wooding, City Clerk of Long 20

Branch, Leo J. Warwick, City Solicitor of

Long Branch.

P lease ta k e n o tice that on Monday the 29th

day of August, 1938, at ten o ’clock in the forenoon

of that day (daylight saving time) or as soon

thereafter as counsel can he heard, I shall apply

to the Honorable Joseph B. Perskie, Justice of

the Supreme Court of New Jersey, at his Cham-

bers located in the City of Atlantic City, New

Jersey, for a writ of certiorari to review an ordi

nance passed by the City Commissioners of the

City of Long Branch, in the State of New Jersey,

on the 7th day of June, 1938, entitled “ An Ordi

nance to amend an ordinance entitled: ‘ An

Ordinance providing for the maintenance and

regulation of bathing beaches in the City of Long-

Branch and authorizing the imposition by the

Board of Commissioners of the City of Long

Sirs:

40

16

Notice of Application.

Branch or their duly authorized agent of fees for

the use of said beaches,’ ” passed June 6, 1933,

and also the acts of the City Clerk of the said City

of Long Branch under the said ordinance as

amended.

10 A nd ta k e n o tice fu r t h e r that annexed to this

notice and made a part thereof are exact copies

of the petition and affidavits and exhibits thereto

annexed upon which the application as aforesaid

will be made.

Yours truly, &c.,

W alte r J. U pp e r m a n

and

20 R oger M. Y a n c e y ,

Attorneys for Prosecutrix.

R obert S. H artgrove,

Counsel for Prosecutrix.

30

40

17

NEW JERSEY SUPREME COURT.

Stipulation of Continuance.

J. A r t h u r W ooding , Clerk of the

City of Long Branch, New

Jersey, and the C it y of L ong

B r a n c h , New Jersey,

A llie B u l l o c k ,

vs.

Prosecutrix,

Defendants.

On Certiorari.

Stipulation of

Continuance.

On Petition. 10

It is hereby stipulated by and between the At

torneys for the respective parties herein that the 20

application for a rule to show cause why a writ

of certiorari should not be issued herein, which

application was originally returnable on August

29tli, 1938, before the Honorable Joseph B. Per-

skie, a Justice of the New Jersey Supreme Court,

at his chambers, Guarantee Trust Building, At

lantic City, and continued until September 17,

1938, be and the same is hereby further continued

until Saturday, October 1, 1938, before said Jus

tice, at the aforesaid chambers, at the hour of 3 0

11 o ’clock in the forenoon.

It is further stipulated that the prosecutrix

may present her aforesaid application on the con-

40

18

tinued date as if same were moved on the original

return date, August 29th, 1938.

Dated: September 16, 1938.

U p p e r m a n & Y a n c e y ,

Attorneys for Prosecutrix,

Allie Bullock.

L eo J. W a r w ic k ,

Attorney for J. Arthur Wooding,

Clerk of the City of Long

Branch, New Jersey, and the

City of Long Branch, New

Jersey.

Writ of Certiorari.

20

Writ of Certiorari.

N e w J ersey , ss. : T h e S tate of N e w J ersey to

J . A r t h u r W ooding, C le rk

of t h e C it y of L ong B r a n c h ,

(L . S .) N e w J ersey , an d T h e C it y

of L ong B r a n c h , C o u n t y of

M o n m o u t h — G reetin g :

We being willing, for certain reasons, to be cer

tified of a certain municipal ordinance, to wit,

An Ordinance to amend an ordinance entitled:

“ An Ordinance providing far the maintenance

and regulation of bathing beaches in the City of

Long Branch and authorizing the imposition by

the Board of Commissioners of the City of Long

Branch or their duly authorized agent of fees for

the use of said beaches,” passed June 6, 1933,

introduced at a meeting of the City Commission

ers of the said City of Long Branch on the 24th

day of May, 1938 and passed June 7, 1933, and

the decision of the City Clerk of the said City of

40

19

Long Brandi acting thereunder on the 17th day

of July, 1938 in rejecting the application of Allie

Bullock for a permit or license to use the bathing

facilities of Beach No. 1 in the said City of Long

Branch, do command you that you certify and

send under your seal, to our Justices of our Su

preme Court of Judicature, at Trenton, on the

21st day of October, 1938, the said municipal Ordi

nance and the said decision of the said City Clerk

of Long Branch above mentioned, together with

all things touching and concerning the same, as

fully and completely as they remain before you,

together with this our writ, that we may cause

to be done thereupon what of right and justice

and according to the laws of the State of New

Jersey ought to be done.

W it n e ss , T h o m as J. B rogan , Esquire, Chief

Justice of our Supreme Court, at Trenton, this

3rd day of October in the year of our Lord One

Thousand Nine Hundred and Thirty-eight.

F red L. B loodgood,

Clerk.

W alter J. U p p e r m a n ,

B oger M . Y a n c e y ,

Attorneys for Prosecutrix.

B obert S. H artgrove,

Of Counsel for Prosecutrix.

Writ of Certiorari.

Allocatur.

The Writ of Certiorari is allowed.

Depositions may be taken by either party upon

five (5) days’ notice.

J oseph B . P e r sk ie ,

Justice.

10

20

30

40

20

Return to Writ.

NEW JERSEY SUPREME COURT.

A llie B u l l o c k ,

Prosecutrix,

vs.

J. A r t h u r W ooding, Clerk of the

City of Long Branch, New

Jersey, and the C it y of L ong

B r a n c h , County of Monmouth,

Defendants. I, 2

I , J. A r t h u r W ooding , Clerk of the City of

2 Q Long Branch, do hereby send to the Supreme

Court of the State of New Jersey,

1. The Ordinance entitled: “ An Ordinance

providing for the maintenance and regulation of

bathing beaches in the City of Long Branch and

authorizing the imposition by the Board of Com

missioners of the City of Long Branch, or their

duly authorized agents, of fees for the use of said

beaches.” Passed June 6, 1933.

2. An Ordinance to amend an Ordinance en

titled: “ An Ordinance providing for the mainten

ance and regulation of bathing beaches in the City

of Long Branch and authorizing the imposition

by the Board of Commissioners of the City of

Long Branch, or their duly authorized agents, of

fees for the use of said beaches.” Passed June 7,

1938. Together with all papers and things touch

ing and concerning the same, as by the writ of

certiorari sealed the third day of October, 1938

before Honorable Thomas J. Brogan, Chief Jus

tice of the Supreme Court, I am commanded to do.

30

On Certiorari.

Return of Writ.

21

I certify that I am the Clerk of the City of Lon"

Branch in the County of Monmouth and State of

New Jersey, and that the following are true copies

of Ordinances passed by the Board of Commis

sioners of the City of Long Branch relating to the

regulation of bathing beaches, form of application

for bathing privileges, and that together they con- ̂0

stitute the entire record of the proceedings in the

above entitled action.

Signed this twentieth day of October, one thou

sand nine hundred and thirty-eight, and sealed

with the seal of the City of Long Branch, County

of Monmouth, State of New Jersey.

J. A r t h u r W ooding ,

City Clerk of the Citv of Long Branch.

20

Ordinance, June 6, 1933.

Ordinance Annexed to Return.

A n O rd in an ce providing for the maintenance and

regulation of bathing beaches in the City of

Long Branch and authorizing the imposition by

the Board of Commissioners of the City of

Long Branch or their duly authorized agent of

fees for the use of such beaches. 30

The Board of Commissioners of the City of

Long Branch do ordain:

1. That so much of the lands and premises ly

ing east of Ocean Avenue as are now or shall be

hereafter owned by the City of Long Branch and

not used for any other purpose, or over which the

City of Long Branch may, by consent of the own

ers, or otherwise have control for the purpose, 40

22

shall be maintained and operated as public beaches

by the City of Long Branch so that they may be

used for bathing and recreation.

2. There shall be charged for the use of the

bathing facilities and access to the said recrea-

10 tional grounds the sum, of $1.00 for each person,

which said fee shall entitle the said person to the

use of any part of the said premises for recrea

tional and bathing purposes for a period not less

than twelve weeks beginning not before June first

and ending not later than October first in each

year, as the period for use of said beach or bath

ing ground shall be from time to time determined

by the Director of the Department of Parks and

Public Property, subject to the direction of the

20 Board of Commissioners of the City of Long-

Branch, provided, however, if any person or per

sons shall desire the use of the grounds, in the

ordinance set forth, for one day only, he or she

shall pay the sum of Fifty Cents. Every person

registered and paying therefor shall receive a

badge, check or other insignia which shall be worn

by the registrant when required, or shall be shown

at the request of any officer or employee of the

City of Long Branch having jurisdiction.

30

3. All children of the age of twelve years or

under shall be admitted to the said beaches and

bathing privileges without charge, provided, how

ever, that the Director of the Department of

Parks and Public Property, or his duly author

ized representative shall make reasonable regula

tions for the care of said children and may in his

discretion not permit any such child to enter upon

such beaches or in the waters adjacent to the

40 beaches unless he or she is accompanied by a com

petent person of mature age.

Ordinance, June 6, 1933.

23

4. All persons residing in a charitable insti

tution or institutions in the City of Long Branch,

shall be entitled to enter upon that part of the

bathing beaches in this ordinance described or in

the waters adjacent thereto, as shall be from time

to time designated by the Director of the Depart

ment of Parks and Public Property of the City

of Long Branch for that purpose without charge.

The City of Long Branch shall comply with all

the laws regarding the safety of bathers and shall

provide all such safety devices for bathers as are

required by the laws of New Jersey and particu

larly shall keep and observe all the provisions of

Chapter 174 of the Acts of the Legislature of the

State of New Jersey for the year 1900, and upon

the failure to do so the Director of the Depart

ment of Parks and Public Property may close said

beaches or any part thereof and the Director of

the Department of Parks and Public Property

may at any and all times close said beaches and

forbid bathing thereon because of storm or con

ditions of the beaches or ocean which may be

deemed dangerous for bathers.

All expenses and costs to the City of Long

Branch in carrying out the terms of this ordi

nance shall be paid from the appropriations made

in the budget of the City of Long Branch for the

current year for this purpose.

All fees and income from the operation of said

beaches shall be collected by the Director of the

Department of Parks and Public Property or his

duly authorized agent and transmitted to the

Treasurer of the City of Long Branch at the end

of each day, to become the property of the City

of Long Branch. All matters relating to the use

and administration of said beaches are hereby

committed to the Director of the Department of

Ordinance, June 6, 1933.

10

20

30

40

24

Parks and Public Property, subject, however, to

the control at all times by the Board of Commis

sioners of the City of Long Branch.

Ordinance, June 6, 1933.

10

Introduced May 13, 1933.

Passed June 6, 1933.

J . W il l ia m J ones

D orm an M cF addin

W alto n S h e r m a n

W il l ia m I. R osenfeld ,

Commisioners.

Attest:

F r a n k A. B razo ,

City Clerk.

20

P ublic N otice

The foregoing ordinance was finally passed by

the Board of Commissioners of the City of Long

Branch, New Jersey, on the sixth day of June,

1933.

D a t e d : Long Branch, N. J., June 7, 1933.

F r a n k A. B razo ,

City Clerk.

134 (Thurs.)

40

25

A n O rd in an ce to amend an ordinance entitled:

“ An Ordinance providing for the maintenance

and regulation of bathing beaches in the City of

Long Branch and authorizing the imposition

by the Board of Commissioners of the City of

Long Branch or their duly authorized agent of

fees for the use of said beaches,” passed June 6,

1933.

The Board of Commissioners of the City of

Long Branch Do O r d a in :

Section 1. That Section 2 of the above entitled

ordinance be and the same is hereby amended so

that it supersedes the present Section 2 in said

ordinance and shall read as follows:

Section 2. For the government, use and opera

tion of said public beaches the following rules and

regulations shall be in force and effect and the

fees hereinafter provided for shall be imposed and

charged:

1. All persons desiring the use of the bathing

facilities and access to said beaches shall register

in the City Clerk’s Office, City Hall, and upon

paying the fee or charge as hereinafter provided,

shall receive from the City Clerk a badge, check or

other insignia which shall be worn by the regis

trant when required, or shall be shown at the re

quest of any officer or employee of the City of

Long Branch. All badges, checks or other in

signia and all written evidence of the right to use

said beaches shall not be transferable. 2

2. For the purpose of avoiding congestion on

any of said beaches, and for a proper distribution

Amended Ordinance Annexed to Return.

10

20

30

40

26

of patrons, and for the better protection and

safety of patrons on said beaches, the City Clerk

is authorized and directed to issue badges, checks

or other insignia of distinctive design or color for

the use of each of the respective beaches.

10 3. The said fees hereinafter provided for shall

entitle said registrant to said use for a period of

not less than ten weeks beginning not before June

15th and ending not later than October 1st, of each

year, as the period for use shall be from time to

time determined by the Director of the Depart

ment of Parks and Public Property, subject, how

ever, to the direction of the Board of Commis

sioners of the City of Long Branch.

20 4. All permits, licenses or other rights and

privileges to use said bathing facilities shall be

subject to such regulations as are now in force or

which may hereafter be made during the period

covered by such permit.

5. The Board of Commissioners may by reso

lution adopt such additional rules and regulations

for the government, use and policing of such

beaches and places of recreation not inconsistent

gQ with the provisions of this ordinance.

6. F e e s : There shall be charged for the use

of the bathing facilities and access to said recrea

tional grounds the following fees:

Bona fide residents of the City of Long

Branch per season.....................................$ 1.00

Guests of residents (not more than two

guests per day) for each guest, plus a de

posit of 50c per badge

Amended Ordinance, June 7, 1938.

40 .50

27

Amended Ordinance, June 7, 1938.

Non-residents, seasonal perm it................... 3.00

Where bathing house facilities are provided

bath house for not more than five persons,

per season .................................................. 25.00

Section 2: That Section 4 of the above entitled ^g

ordinance be and the same is hereby amended so

that it supersedes the present Section 4 of said

ordinance, and shall read as follows:

Section 4: All persons residing in a charitable

institution or institutions in the City of Long

Branch shall be entitled to enter upon that part of

the bathing beaches in this ordinance described

or in the waters adjacent thereto, as shall be from

time to time designated by the Director of the De- gQ

partment of Parks and Public Property of the

City of Long Branch for that purpose without

charge.

The City of Long Branch shall comply with all

the laws regarding the safety of bathers and shall

provide all such safety devices for bathers as are

required by the laws of New Jersey and particu

larly shall keep and observe all the provisions of

Chapter 174 of the Acts of the Legislature of the

State of New Jersey for the year 1900, and upon

the failure to do so the Director of the Depart

ment of Parks and Public Property may close

said beaches or any part thereof and the Director

of the Department of Parks and Public Property

may at any and all times close said beaches and

forbid bathing thereon because of storm or condi

tions of the beaches or ocean which may be deemed

dangerous for bathers.

All expenses and costs to the City of Long

Branch in carrying out the terms of this ordinance

shall be paid from the appropriations made in the

28

Amended Ordinance, June 7, 1938.

budget of the City of Long Branch, for the cur

rent year for this purpose.

All fees and income from the operation of said

beaches shall be collected by the City Clerk and

transmitted to the Treasurer of the City of Long

Branch to become the property of the City ol

10 Long Branch. All matters relating to the use and

administration of said beaches are hereby com

mitted to the Director of the Department of Parks

and Public Property subject, however, to the pro

visions of this ordinance and such rules and regu

lations as may hereafter be duly adopted by the

Board of Commissioners of the City of Long

Branch.

All persons violating any provisions of this

ordinance shall upon conviction before the Re-

corder or other officer having jurisdiction forfeit

and pay a fine not exceeding $50.00 for each of

fence and in default of payment of such fine shall

be imprisoned in the County Jail for a term not

exceeding 30 days in the discretion of the Re

corder or Police Magistrate.

Introduced May 24, 1938.

Passed June 7,1938.

30

Attest:

J. A r t h u r W ooding,

City Clerk.

A l t o n V . E vans

W alto n S h e r m a n

F r a n k A . B razo

Commissioners.

40

29

Registration Card Annexed to Return.

P u b lic N otice

The foregoing ordinance was finally passed by

the Board of Commissioners of the City of Long

Branch, New Jersey, on the seventh day of June,

1938.

Dated Long Branch, N. J., June 7, 1938.

J. A r t h u r W ooding,

City Clerk.

Registration Card Annexed to Return.

B a t h in g R egistration R esiden t

C ity of L ong B r a n c h

n e w jersey

Badge No....................... Date.................................

Name .........................................................................

Address .......................................... ..........................

In accordance with an ordinance of the City of

Long Branch regulating the use of the bathing

beaches of the City of Long Branch by bathers, I

represent that I am a bona fide resident of the 6

City of Long Branch, and I herewith make appli

cation for bathing privileges for the season of

1938, and herewith pay the fee of One Dollar

($1.00) for the same. I agree to abide by the

rules and regulations set forth in the said ordi

nance and assume all risks incident thereto.

Signature of Applicant.

40

30

Reasons.

NEW JERSEY SUPREME COURT.

10

J. A r t h u r W ooding, Clerk of the

City of Long Branch, New

Jersey, and the C it y of L ong

B r a n c h , New Jersey,

A llie B u l l o c k ,

Prosecutrix,

vs.

Defendants.

On Certiorari.

Reasons.

The said prosecutrix, by her attorneys, comes

and prays that “ An Ordinance to amend an ordi

nance entitled: ‘ An Ordinance providing for the

maintenance and regulation of bathing beaches in

the City of Long Branch and authorizing the im

position by the Board of Commissioners of the

City of Long Branch or their duly authorized

agents of fees for the use of the said beaches,

passed June 6, 1933’ enacted and passed by

the Board of Commissioners of the City of Long

Branch, New Jersey, on the 7th day of June, 1938,

be declared null and void, and for nothing holden,

1. That the said amended ordinance of the

said City of Long Branch upon which the City

Clerk of the said City of Long Branch relied in

rejecting the application of the prosecutrix for a

permit or license to use the bathing facilities of'

Beach No. 1 of the said City of Long Branch is

unconstitutional and violative of both the state

and the federal constitutions in that:

(a) It is discriminatory.

30 for the following reasons, to wit:

40

31

(b) The said amended ordinance was not

legislation for the common good, interest,

health or safety of the community of the said

City of Long Branch.

(c) The said amended ordinance was

legislation for the benefit of a class.

(d) The said amended ordinance was an

attempt to legislate as to the private rights

of the prosecutrix and by the City of Long

Branch as to the use of the public beaches

of the City of Long Branch and the waters of

the Atlantic Ocean, notwithstanding such

rights should be determined and can be de

termined only by judicial proceedings under

public statute.

(e) The said amended ordinance is an at

tempt by legislation to abate a public nuis

ance, and also an attempt to provide a sum

mary proceedings, in the nature of a criminal

proceedings, to try and adjudicate what would

otherwise be an indictable offense, and thus

deprive the prosecutrix of her right to indict

ment and trial by jury.

(f) The said amended ordinance is in con

flict with the spirit and letter of the general

laws of the State of New Jersey.

(g) The said amended ordinance in oper

ation and effect is in conflict with the Civil

Rights Act of the State of New Jersey in that

it denies to the prosecutrix and other mem

bers of the colored race, as well as all persons

within the jurisdiction of the State of New

Jersey, the full and equal accommodations,

advantages, facilities and privileges to the

Reasons.

10

20

30

40

Reasons.

public beaches of the City of Long Branch,

and the public bath houses thereon.

(h) The said amended ordinance intro

duces a policy contrary to and at variance

with the public policy of the State of New

Jersey.

(i) The said amended ordinance is an un

warranted and unlawful delegation of the

legislative powers of the governing bodies of

the municipality to an agent thereof.

(j) The said amended ordinance, as a rev

enue measure, is discriminatory and illusory.

(k) The said amended ordinance, as a

revenue measure, is detrimental to the finan

cial welfare of the said City of Long Branch.

(l) The said amended ordinance, as a

revenue measure, is an unlawful delegation of

the taxing power of the governing body of the

City of Long Branch to the City Clerk or an

agent thereof.

(m) The said amended ordinance is un

reasonable, arbitrary, uncertain and indefin

ite in its terms, operation and exercise.

(n) The said amended ordinance vests in

a municipal agent, to wit, the City Clerk,

powers arbitrary and oppressive, and a dis

cretion to prevent private citizens of the City

of Long Branch, State of New Jersey, from

the use of the beach and the waters of the

Atlantic Ocean.

(o) The said amended ordinance gives no

right of appeal from the exercise of the arbi

trary or discretionary powers by the said City

Clerk of Long Branch.

33

(p) The said amended ordinance provides

no procedure for the prosecutrix or any ap

plicant to obtain a badge or permit for the

use of the bathing facilities and access to the

said beaches.

(q) The said amended ordinance is viola

tive of the Laws of the State of New Jersey,

to wit, the so-called Home Rule Act, as to the

penalty which it seeks to impose upon the

prosecutrix or any other person violating

any of the terms of the said amended ordi

nance.

(r) The said amended ordinance is in

divers other respects illegal, unjust and op

pressive and should be set aside and be for

nothing holden.

W alter J. U p p e r m a n ,

R oger M . Y a n c e y ,

Attorneys for Prosecutrix.

R obert S. H artgrove,

Counsel for Prosecutrix.

Reasons.

30

20

30

40

34

Affidavit of Stenographer.

NEW JERSEY SUPREME COURT.

10

A l l ie B u l l o c k ,

Prosecutrix,

vs.

J. A r t h u r W ooding, Clerk of the

City of Long Branch and the

C it y oe L ong B r a n c h , New

Jersey,

Defendants.

On Certiorari.

Affidavit of

Stenographer.

20

S tate of N ew J ersey ,

C o u n t y of M o n m o u t h .

ss.:

M yrtle E. H o yt , of full age, being duly sworn

according to law, upon her oath deposes and says:

That she will carefully, faithfully and impartially

take stenographically and reproduce in manu

script or typewriting the testimony given in the

above entitled cause.

M yrtle E. H o yt .

30 Subscribed and sworn to before me |

this 21st day of November, 1938. ^

J u l iu s J . G olden ,

Master in Chancery of New Jersey.

40

35

Testimony.

NEW JERSEY SUPREME COURT.

A ll ie B u l lo c k ,

Prosecutrix,

vs.

J. A r t h u r W ooding, Clerk of the

City of Long Branch and the

C it y of L ong B r a n c h , New

Jersey,

Defendants.

Transcript of testimony taken before Julius J.

G olden , a Supreme Court Commissioner of New 2 0

Jersey, at his offices, at 190 Broadway, Long

Branch, N. J., on Monday, November 21st, 1938

at 10:00 o ’clock A. M.

By consent of all counsel, this testimony was

taken down stenographically, by questions and an

swers, by Myrtle E. Hoyt, a stenographer, who

was first duly sworn to take such evidence care

fully, faithfully and impartially, and to make a

true and correct transcript thereof.

Appearances: ^

W alter J. U pp e r m a n and R oger M. Y a n c e y ,

Esqs., for the Prosecutrix.

L eo J. W a r w ic k , E sq., for J. Arthur Wood

ing and the City of Long Branch.

10

On Certiorari.

Testimony.

40

36

J. Arthur Wooding, for Prosecutrix—Direct.

J. Arthur W ooding, called as a witness on be

half of the prosecutrix, being first duly sworn

testified as follows:

Direct examination hy Mr. Yancey:

10 Q- What is your name? A. J. Arthur Wood

ing.

Q. What is your official capacity? A. City

Clerk of the City of Long Branch.

Q. How long have you been the City Clerk? A.

Since May 19, 1936.

Q. And were you the Clerk of the City of Long

Branch on or about the 7th day of June, 1938? A.

Yes, sir.

Q. On that day the Board of Commissioners

20 passed an ordinance to amend an ordinance pro

viding for the maintenance and regulation of

bathing beaches in the City of Long Branch and

authorizing the imposition by the Board of Com

missioners of the City of Long Branch or their

duly authorized agent of fees for the use of said

beaches? A. Yes, sir.

Q. Were you the Clerk of the City of Long

Branch on or about July 17th, 1938? A. Yes.

Q. And in the same capacity at the present

2 Q time? A. Yes, sir.

Q. As such Clerk of the said City of Long

Branch, you have direct supervision and control

of the issuance of the licenses or passes upon the

beaches of the city? A. At that time?

Q. At that time. A. Yes.

Q. You did have that control on the sixteenth

day of July? A. That is right.

Q. Do you have the total registrations with

you on that date? A. I have.

Q. Let us have them. Can you give them to us ?

A. Just the figures of that date?

40

37

Q. Yes, the figures of that date.

(After off-the-record discussion.)

Mr. Yancey: I now offer the original or

dinance and the amended ordinance in evi

dence. (The original ordinance and the

amended ordinance referred to were re- 10

spectively marked Exhibit P-1 and P-2.)

The original ordinance referred to reads

as follows:

“ A x ordinance providing for the main

tenance and regulation of bathing beaches

in the City of Long Branch and authoriz

ing the imposition by the Board of Com

missioners of the City of Long Branch or

their duly authorized agent of fees for the 20

use of such beaches.

The Board of Commissioners of the City

of Long Branch do ordain:

1. That so much of the lands and prem

ises lying east of Ocean Avenue as are

now or shall be hereafter owned by the

City of Long Branch and not used for any

other purpose, or over which the City may,

by consent of the owners, or otherwise, 30

have control for the purpose, shall be

maintained and operated as public beaches

by the City of Long Branch so that they

may be used for bathing and recreation.

2. There shall be charged for the use of

the bathing facilities and access to the said

recreational grounds the sum of $1.00 for

each person, which said fee shall entitle

the said person to the use of any part of

the said premises for recreational and ^

Exhibit P-1, Original Ordinance.

bathing purposes for a period not less than

twelve weeks beginning not before June

first and ending not later than October

first in each year, and the period for the

use of said beach and bathing ground shall

be from time to time determined by the

Director of the Department of Parks and

Public Property, subject to the direction of

the Board of Commissioners of the City of

Long Branch, provided, however, if any

person or persons shall desire the use of

the grounds, in the ordinance set forth,

for one day only, he or she shall pay the

sum of Fifty Cents. Every person regis

tered and paying therefor shall receive a

badge, check or other insignia which shall

be worn by the registrant when required,

or shall be shown at the request of any

officer or employee of the City of Long

Branch having jurisdiction.

3. All children of the age of twelve

years or under shall be admitted to the said

beaches and bathing privileges without

charge, provided, however, that the Direc

tor of the Department of Parks and Pub

lic Property, or his duly authorized repre

sentative shall make reasonable regulations

for the care of said children and may in

his discretion not permit any such child to

enter upon such beaches or in the waters

adjacent to the beaches unless he or she is

accompanied by a competent person of ma

ture age.

L All persons residing in a charitable

institution or institutions in the City of

Long Branch, shall be entitled to enter

Exhibit P-1, Original Ordinance.

39

upon that part of the bathing beaches in

this ordinance described or in the waters

adjacent thereto, as shall be from time to

time designated by the Director of the De

partment of Parks and Public Property of

the City of Long Branch for that purpose

without charge.

The City of Long Branch shall comply

with all the laws regarding the safety of

bathers and shall provide all such safety

devices for bathers as are required by the

laws of New Jersey and particularly shall

keep and observe all the provisions of

Chapter 174 of the Acts of the Legislature

of the State of New Jersey for the year

1900, and upon the failure to do so the Di

rector of the Department of Parks and

Piiblic Property may close said beaches or

any part thereof and the Director of the

Department of Parks and Public Property

may at any time and all times close said

beaches and forbid bathing thereon because

of storm or conditions of the beaches or

ocean which may be deemed dangerous for

bathers.

All expenses and costs to the City of

Long Branch in carrying out the terms of

this ordinance shall be paid from the ap

propriations made in the budget of the

City of Long Branch for the current year

for this purpose.

All fees and income from the operation

of said beaches shall be collected by the

Director of the Department of Parks and

Public Property or his duly authorized

agent and transmitted to the Treasurer of

the City of Long Branch at the end of each

Exhibit P-1, Original Ordinance.

10

20

30

40

\

day, to become the property of the City of

Long Branch. All matters relating to the

use and administration of said beaches are

hereby committed to the Director of the

Department of Parks and Public Property,

subject, however to the control at all times

by the Board of Commissioners of the City

of Long Branch.

Introduced May 13, 1933.

Passed June 6, 1933.

J . W il l ia m J ones ,

D orm an M cF ad d in ,

W alto n S h e r m a n ,

W il l ia m I. R oseneeld ,

Commissioners.

Attest:

F r a n k A. B razo ,

City Clerk.

Exhibit P-2, Amended, Ordinance.

P ublic N o tice .

The foregoing ordinance was finally

passed by the Board of Commissioners of

the City of Long Branch, New Jersey, on

the sixth day of June, 1933.

Dated: Long Branch, N. J., June 7, 1933.

F r a n k A. B razo ,

City Clerk.” '

The amended ordinance referred to reads

as follows:

A n O rdinance to amend an ordinance

entitled: ‘ An Ordinance providing for the

41

maintenance and regulation of bathing

beaches in the City of Long Branch and

authorizing the imposition by the Board of

Commissioners of the City of Long Branch

or their duly authorized agent of fees for

the use of said beaches,’ passed June 6,

1933.

The Board of Commissioners of the City

of Long Branch do okdain :

Section 1. That Section 2 of the above

entitled ordinance be and the same is here

by amended so that it supersedes the pres

ent Section 2 in said ordinance and shall

read as follows:

Section 2. For the government, use and

operation of said public beaches the fol

lowing rules and regulations shall be in

force and effect and the fees hereinafter

provided for shall be imposed and charged:

1. All persons desiring the use of the

bathing facilities and access to said beaches

shall register in the City Clei’k ’s Office,

City Hall, and upon paying the fee or

charge as hereinafter provided, shall re

ceive from the City Clerk a badge, check or

other insignia which shall be worn by the

registrant when required, or shall be shown

at the request of any officer or employee of

the City of Long Branch. All badges,

checks or other insignia and all written evi

dence of the right to use said beaches shall

not be transferable.

2. For the purpose of avoiding conges

tion on any of said beaches, and for a

proper distribution of patrons, and for the

Exhibit P-2, Amended Ordinance.

10

20

30

40

42

better protection and safety of patrons on

said beaches, the City Clerk is authorized

and directed to issue badges, checks or

other insignia of distinctive design or color

for the use of each of the respective

beaches.

10

3. The said fees hereinafter provided

for shall entitle said registrant to said use

for a period of not less than ten weeks be

ginning not before June 15th and ending

not later than October 1st, of each year, as

the period for use shall be from time to

time determined by the Director of the De

partment of Parks and Public Property,

subject, however, to the direction of the

20 Board of Commissioners of the City of

Long Branch.

4. All permits, licenses or other rights

and privileges to use said bathing facilities

shall be subject to such regulations as are

now in force or which may hereafter be

made during the period covered by such

permit.

5. The Board of Commissioners may by

resolution adopt such additional rules and

regulations for the government, use and

policing of such beaches and places of rec

reation not inconsistent with the provisions

of this ordinance.

6. F e e s : There shall be charged for

the use of the bathing facilities and access

to said recreational grounds the following-

fees :

Exhibit P-2, Amended Ordinance.

40

43

Exhibit P-2, Amended Ordinance.

Bona fide residents of the City of

Long Branch per season..............$ 1.00

Guests of residents (not more than

two guests per day) for each

guest, plus a deposit of 50 ̂ per

badge .......................................................50

Non-residents, seasonal permit....... 3.00 10

Where bathing house facilities are

provided bath house for not

more than five persons, per sea

son .................................................. 25.00

Section 2: That Section 4 of the above

entitled ordinance be and the same is here

by amended so that it supersedes the pres

ent Section 4 of said ordinance, and shall

read as follows: 2 q

Section 4: All persons residing in char

itable institution or institutions in the City

of Long Branch shall be entitled to enter

upon that part of the bathing beaches in

this ordinance described or in the waters

adjacent thereto, as shall be from time to

time designated by the Director of the De

partment of Parks and Public Property of

the City of Long Branch for that purpose

without charge. 30

The City of Long Branch shall comply

with all the laws regarding the safety of

bathers and shall provide all such safety

devices for bathers as are required by the

laws of New Jersey and particularly shall

keep and observe all the provisions of Chap

ter 174 of the Acts of the Legislature of

the State of New Jersey for the year 1900,

and upon the failure to do so the Director

40

of the Department of Parks and Public

Property may close said beaches or any

part thereof and the Director of the De

partment of Parks and Public Property

may at any and all times close said beaches

and forbid bathing thereon because of

storm or conditions of the beaches or ocean

which may be deemed dangerous for bath

ers.

All expenses and costs to the City of

Long Branch in carrying out the terms of

this ordinance shall be paid from the ap

propriations made in the budget of the City

of Long Branch, for the current year for

this purpose.

All fees and income from the operation

of said beaches shall be collected by the

City Clerk and transmitted to the Treas

urer of the City of Long Branch to be

come the property of the City of Long

Branch. All matters relating to the use

and administration of said beaches are

hereby committed to the Director of the

Department of Parks and Public Property

subject, however, to the provisions of this

ordinance and such rules and regulations

as may hereafter be duly adopted by the

Board of Commissioners of the City of

Long Branch.

All persons violating any provisions of

this ordinance shall upon conviction be

fore the Recorder or other officer having

jurisdiction forfeit and pay a fine not ex

ceeding $50.00 for each offence and in de

fault of payment of such fine shall be im

prisoned in the County Jail for a term not

Exhibit P-2i Amended Ordinance.

45

exceeding 30 days in the discretion of the

Recorder or Police Magistrate.

J. Arthur Wooding, for Prosecutrix— Direct.

Introduced May 24, 1938.

Passed June 7, 1938.

A lt o n V . E va n s ,

W alto n S h e r m a n ,

F r a n k A . B razo ,

Commissioners.

Attest:

10

J. A r t h u r W ooding,

City Clerk.

P u b lic N o tic e .

A\)

The foregoing ordinance was finally

passed by the Board of Commissioners of

the City of Long Branch, New Jersey, on

the seventh day of June, 1938.

Dated: Long Branch, N. J., June 7, 1938.

J. A r t h u r W ooding ,

City Clerk.”

Q. Now, Mr. Wooding, what was the total

registration on the 16th day of July, 1938? A. 30

On July 16th there was a registration of 678.

Q. 67.8? A. Yes.

Q. And what was the total registration on the

17th day of July, 1938?

Mr. Warwick: At the completion of the

day?

Mr. Yancey: Yes.

A. 296.

40

46

Mr. Warwick: That is the total regis

tration on the cards sold on that day?

The Witness: Yes.

Q. Referring to your record again, Mr. Clerk,

will you kindly tell us the registration on the 21st

10 day of July, 1938? A. On the 21st day of July?

Q. Yes, of 1938. A. 22.

Q. 22? A. Yes, sir.

Q. Referring again to the records, how about

the 24th day of July! A. Nothing.

Q. Referring to your records, how about the

14th day of August, 1938? A. 60.

Q. 60? A. 60.

Q. And how about the 17th day of August, 1938?

A. 27.

20 Q. 27? A. Yes.

Q. Now, Mr. Wooding, have you any way of

telling the total registrations or sales allowed for

each beach on these dates? The dates I have just

asked you. A. No, sir.

Q. As a matter of fact, under this ordinance, the

beach is divided into how many sections? A.

Four beaches.

Q. How are they designated? A. 1, 2, 3 and

4.

30 Q- You have no way of telling what was sold

for these different beaches? A. Yes, sir.

Q. Suppose you give us the number sold to the

beaches. Now, in respect to the 16th day of July?

A. What is your question?

Q. What was the total sold to Beach No. 1? A.

436 for the 16th day of July.

Q. How about Beach No. 2? A. 45.

Q. No. 3? A. 14.

Q. 14? A. Yes.

40 Q. No. 4? A. 178.

J, Arthur Wooding, for Prosecutrix— Direct.

47

Q. How about July 17th? A. Now, you are

going to find a discrepancy of five on this date.

There were three guest tags sold and during the

first part of the sales there was no record kept of

what beaches the guests went to and the same is

true as to non-residents. There were 2 non-resi

dents sold and 3 guests which would bring the

total to 678.

Q. All right. On the 17th day of July for

Beach No. 1? A. For Beach No. 1 there were

179.

Q. Beach No. 2? A. 18.

Q. Beach 3? A. 14.

Q. Beach 4? A. 67, and also on that day there

were 15 guest tags and 3 non-residents making a

total of 296.

Q. How about the 21st of July, same year? A.

Beach 1—12, nothing for Beach 2 and 3 and 9 for

Beach 4, 1 non-resident, making a total of 22.

Q. All right. On July 24th? A. Nothing sold

for any beaches.

Q. No tags sold? A. No tags.

Q. Then on the 14th day of August? A. Beach

1—21, Beach 2—2, Beach No. 3—3, Beach No. 4—

5, and 29 guests making a total of 60.

Q. On the 17th day of August? A. Beach No.

1—6, Beach 2—none, Beach 3—4, Beach 4—14,

and 3 guests making a total of 27.

Q. Now, we notice Mr. Wooding that on the

24th of July no tags were sold? A. That is right.

Q. Do I understand no persons applied at all

for use of the beaches on that day? A. I believe

that there was a terrible rain storm on that day.

Q. Were there any tags refunded on that day?

A. No refunds or anything.

Q. Were there any refunds on the 23rd day of

July of 1938? A. None.

J. Arthur Wooding, for Prosecutrix— Direct.

10

20

30

40

48

Q. On the 24th? A. None.

Q. On the 25th? A. Two.

Q. On what beaches were they bought, or shall

I say refunded? A. I can tell you if you will

give me a few minutes.

Q. You said two refunds? A. Yes, there were

10 2 refunds on that day. Oh! There is a mistake. I

read 2 for 2 persons instead of $2.00. It should

he 4. There is a refund of $2.00 on 4 tags.

Q. Will you give me the beach numbers? A.

The records show that there were 4 refunds. I

am sorry that I cannot tell you for what beaches

the tags were issued. The tags are not marked.

We did not start to mark them until August some

time.

Q. These tags that I am asking you about, are

20 they the season tags on the refunds? A. No,

they are daily or guest tags for the day.

Q. I see. Then there were no refunds up to

the present time with respect to the season tags?

A. Yes, I believe so. On the 16th day of July we

gave a refund. Do you want to know what that

is?

Q. Yes. A. We gave a refund of $7.00 on 7

tags.

Q. Were they season tags? A. Yes, sir.

Q. What beaches were they for? A. They

were all for Beach No. 3.

Q. Who were they refunded to ? A. I think to

Peter J. Donnelly of 113 Liberty Street, Alfredo

Rodriquez, Rex Hotel, 82 Ocean Avenue, Rita Jef

ferson of 194 Belmont Avenue, Charles H. Dicker-

son of 72 Oakhill Avenue, Rosalie Gel, or Gee, of

171 Belmont Avenue, Susie Farmer of 194 Bel

mont Avenue and Richard Gee of 171 Belmont

Avenue.

J. Arthur Wooding, for Prosecutrix— Direct.

49

Q. Now, let me see. Do you know why they

were refunded? A. Yes, I think I do. They were

not satisfied with the beach and they said it was

misrepresented.

Q. Misrepresented? What was misrepre

sented? A. That they wanted tags for another

beach and they were given this beach.

Q. This was Beach No. 3? A. Yes, and they

said that they would not bathe at Beach No. 3 and

to satisfy them they asked for their money back

and I gave them their money back.

Q. Do you recall whether or not they asked for

tags for another beach? A. They might have. I

don’t recall. I don’t remember any of these

people.

Q. Did they come singly or in a body? A. In

a body, but I only gave the money to one party.

Q. Who did you give the money to? A. I don’t

know whether I remember, but I do remember that

I paid it to one person.

Q. Was it a lady by the name of Mrs. Anna

Mumby? A. I don’t recall the name, but I might

recognize her if I saw her.

Q. Did you see her this morning? A. I am not

sure.

Q. But you do think you would recognize her?

A. I might. I am not sure. That was a very

busy day.

Q. But you do remember that they did come in

in a body and claimed and alleged misrepresen

tation of the condition of the beach? A. Not the

condition of the beach, but that they did not want

to go to Beach 3. They were sold tags for

Beach No. 3 and they wanted their money back.

Q. Before they purchased the tags, were they

told that they were getting tags for Beach No. 3?

A. I did not sell them the tags. I was not selling

that day.

J. Arthur Wooding, for Prosecutrix— Direct.

10

20

30

40

50

Q. When they came back for the money, at that

time they did not ask, or you don’t recall being

asked, for tags for Beach 1, 2 or 4? A. I would

not say. I can’t remember.

Q. Referring to your previous testimony re

garding the parties who came in that group, is

10 this the lady you refunded the money to? A. I

have seen her before, but I am not sure.

Q. All this took place on the 16th day of July?

A. That is right.

Q. Plow about the refunds on July 26th? A. I

think we started on July 25th and there were two

and nothing on the 26th of July.

Q. On the 27th? A. Nothing on the 27th.

Q. The 28th? A. There was one on the 28th.

Q. Prom what beach was that? A. Just a min-

20 ute, let me see. Yes, one.

Q. On Beach No. 1? A. Yes. Again that was

a guest tag and not a season one.

Q. Now, how about July 29th? A. There was

none.

Q. And on the 30th? A. One.

Q. What beach was it for? Was it a guest tag

or a season tag? A. A guest tag.