Rogers v Loether Brief for Petitioner

Public Court Documents

October 1, 1973

67 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Rogers v Loether Brief for Petitioner, 1973. 6bd85ec9-c29a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/7ce3756d-f0b1-45c8-bf90-8484b2e17d0a/rogers-v-loether-brief-for-petitioner. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

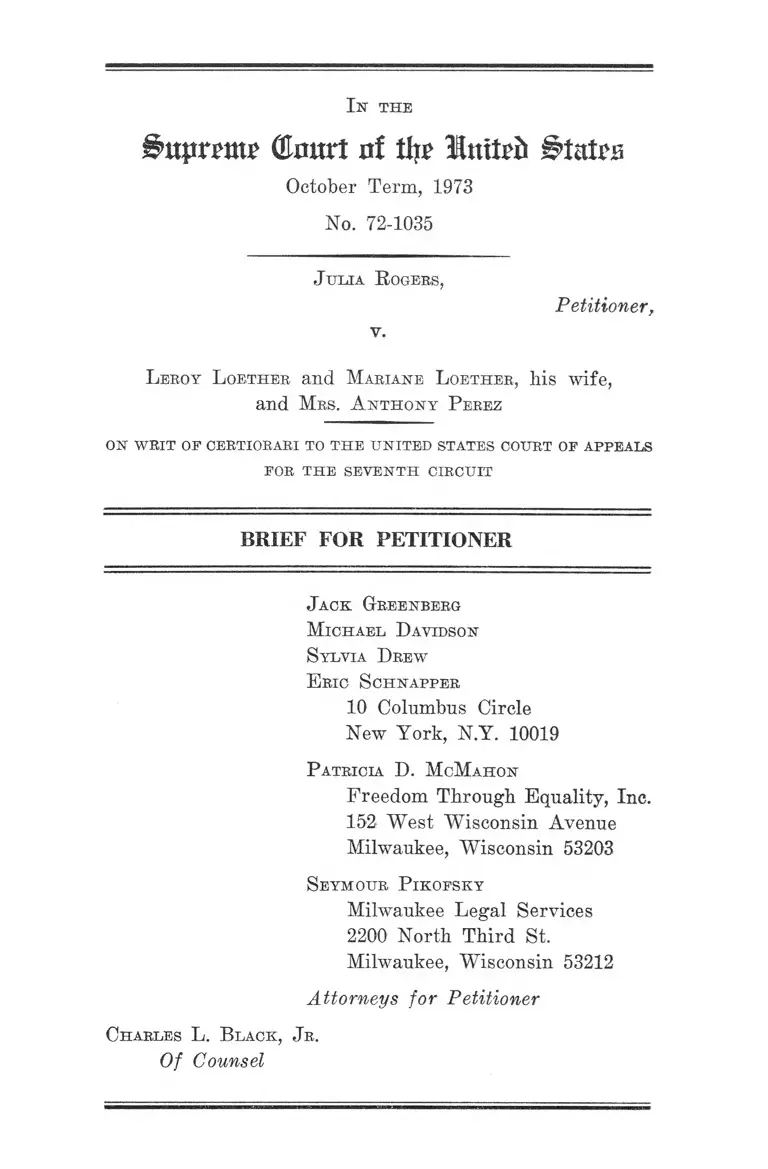

I n t h e

(tart nf ttjr luitrti ^tatra

October Term, 1973

No. 72-1035

J u lia R o g e r s ,

v.

Petitioner,

L eroy L oether and M ariane L oether, h is wife,

and M rs. A n t h o n y P eree

o n w r i t o p c e r t i o r a r i t o t h e u n i t e d s t a t e s c o u r t o f a p p e a l s

FOR T H E SE V E N T H CIRCU IT

BRIEF FOR PETITIONER

J ack Greenberg

M ichael D avidson

S ylvia D rew

E ric S chnapper

10 Columbus Circle

New York, N.Y. 10019

P atricia D . M cM ahon

Freedom Through Equality, Inc.

152 West Wisconsin Avenue

Milwaukee, Wisconsin 53203

S eym our P ik o fsk y

Milwaukee Legal Services

2200 North Third St.

Milwaukee, Wisconsin 53212

Attorneys for Petitioner

Charles L. B lack , J r .

Of Counsel

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Opinions B elow ..... ....... .......... - ................. ............. ......... 1

Jurisdiction ........................... 2

Question Presented.....................— ............................. —. 2

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved....... 2

Statement of the Case ...................................................... 4

Summary of Argum ent........... ................... 6

I. Title V III Provides That All Issues Shall Be Tried

By a Judge Without a Jury ............ ....... .............. 9

a. Statutory Language .............................................. 9

b. Legislative History .............................................. 15

c. Constitutional Consideration ...........................— 19

II. The Seventh Amendment Does Not Require Jury

Trials in Actions Arising Under Title V I I I ........... 27

a. The Rights Protected by Title V III Were

Unknown At Common L aw .................................. 27

b. The Relief Available in a Title VIII Case Is

Part of a Single Integrated Equitable Remedy 36

c. A Court of Equity Could Constitutionally

Award Legal Relief in This C ase...................... 39

PAGE

Conclusion 50

T able of A uthorities

Cases: page

Aladdin Mfg. Co. v. Mantle Lamp Co. of America, 116

F.2d 708 (7th Cir. 1941) ................................................. 41

Alexander v. Hillman, 296 U.S. 222 (1935) ................... 37

Allgeyer v. Louisiana, 165 U.S. 578 (1897) ................... 30

Alpaugh v. Wolverton, 184 Ya. 943, 36 8 .E. 2d 906

(1946) ................ 34

Alsberg v. Lucerne Hotel Co., 46 Misc. 617, 92 N.Y.S.

851 (1905) ................................... 30

Anthony v. Brooks, 67 LRRM 2897 (N.D. Ga. 1967) .... 15

Aqnilines Inc. v. N.L.R.B., 87 F.2d 146 (5th Cir. 1936) .. 28

Banks v. Chicago Grain Trimmers Association, 390

U.S. 459 ........... 12

Banks v. Local 136, I.B.E.W., C.A. Ho. 67-598 (N.D.

Ala., order dated January 25, 1968) .......................... 15

Beacon Theatres v. Westover, 359 U.S. 509 (1959) 8-9-10,46

Beall v. Drane. 25 Ga. 430 (1857) ................. 31

Bean v. Patterson, 122 TJ.S. 496 (1887) ....... 30

Birdsall v. Coolidge, 93 TJ.S. 64 (1877) ........................... 41

Bloom v. Illinois, 391 U.S. 194 (1968) ........................... 18

Booth v. Illinois, 184 U.S. 425 (1902) ............................... 30

Brady v. T.W.A., Inc., 196 F. Supp. 504 (D. Bel.

1961) ......... 29,41

Bridges v. Mendota Apartments, No. 898-H (D.C. Com

mission on Human Rights), EOH 17,505 (1972) .... 14

Brown Shoe Co. v. Hunt, 103 Iowa 586, 72 N.W. 765

(1897) ....... ...... .......... .............................. .................... . 35

Bryson v. Bramlett, 204 Tenn. 347, 321 S.W.2d 555

(1958) ...................................... 40

Burkhardt v. Lofton, 63 Cal. App.2d 230, 146 P.2d 720

(1944) ............................. 31

Busby v. Mitchell, 29 S.C. 447, 7 S.E. 618 (1888) ....... 40

11

1X1

Calye’s Case [1584], 8 Co. 322, 77 Eng-. Rep. 520

(K.B.) ............................ .— ............................................. 35

Camp v. Boyd, 229 U.S. 530 (1913) .............................. 40

Cates v. Allen, 149 U.S. 451 (1893) .... - ...... ........... - ..... 45

Chandler v. Zeigler, 88 Col. 1, 291 P. 822 (1930) .......... . 31

Cheatwood v. South Central Bell Tel. & Tel. Co., 303

F.2d 754 (M.D. Ala. 1959) - ................................... 14,39

Clieff v. Schnackenberg, 384 U.S. 373 (1966) ............... 18

Christie v. York Corp., 1 D.L.R. 81 (1940) ........ .......... 35

City of Independence v. Richardson, 117 Kan. 656,

232 P. 1044 (1925) ................ .......................................... 34

Civil Rights Cases, 109 U.S. 3 (1883) ..................... -.... 32, 35

Clark v. Wooster, 119 U.S. 322 (1886) ........................... 40

Coca-Cola Co. v. Dixi-Cola Laboratories, 155 F.2d 59,

64 (4th Cir.) ............................ — -.............................. 41

Colburn v. Simms [1843], 2 Hare 543, 67 Eng. Rep.

224 (Ch.) ......... ....... ...................... ...........................-....... 40

Connecticut v. Seale (No. 15844, Dist. Ct. New Haven) 26

Constantine v. Imperial Hotels Ltd., 1 K.B. 693 (1944) 35

Cornish v. O’Donoghue, 30 F.2d 983 (D.C. Cir. 1929) .... 31

Corrigan v. Buckley, 299 F. 899 (D.C. Cir. 1924) ....... 30

Corrigan v. Buckley, 271 U.S. 323 (1926) ....................... 32

Cox v. Babcock and Wilcox Company, 471 F.2d 13 (4th

Cir. 1972) ......... ......... ................ ........................... ............ 16

Creedon v. Arielly, 8 F.R.D. 265 (W.D. N.Y. 1948) ....... 29

Culpepper v. Reynolds Metals Co., 296 F. Supp. 1232

(N.D. Ga. 1968) .................................................... -.15, 29, 38

PAGE

Dairy Queen v. Wood, 369 U.S. 469 (1962) ...................46-47

Dansey v. Richardson [1854], 3 E. &B. 144 (Q.B.) ....... 34

Day v. Woodworth, 54 U.S. (13 How.) 363 (1852) ....... 41

Denton v. Stewart, 1 Cox Ch. 258, 29 Eng. Rep. 1156

(Ch. 1786) ......................................................................... 42

DeWolf v. Ford, 193 N.Y. 397, 86 N.E. 527 (1908) ....... 35

IV

Dorsey v. Stuyvesant Town. Corp., 299 N.Y. 512, 87

N.E.2d 541 (1949) ............................................................ 30

Edwards v. Elliott, 88 U.S. 532 (1874) ........................... 14

Fay v. Pacific Improvements Co., 93 Cal. 253, 26 P.

1099 (1891) ................... 34

Fell v. Knight [1841], 8 M. & W. 269 (Q.B.) ............... 33

Fleming v. Peavy Wilson Lumber Co., 38 F. Supp. 1001

(W.D. La. 1941) ........................ 39

Franklin v. Evans, 55 O.L.R. 349 (1924) ....................... 35

Fraser v. McGibbon, 10 Ont. W.R. 54 (1907) ............... 35

Gabrielson v. Hogan, 298 F. 722 (8th Cir. 1924) ........... 42

Glillin v. Federal Paper Board Co., Inc., 52 F.R.D. 383

(D. Conn. 1970) ................... 14

Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co. v. Altamont Springs

Hotel, 206 Ky. 494, 267 S.W. 55 (1925) ................... 34

Gormely v. Clark, 134 U.S. 338 (1890) .......................... 40

Gulbenkian v. Gulbenkian, 147 F.2d 173 (2d Cir. 1945) 42

Hale v. Allinsor, 188 U.S. 56 (1903) ............................... 45

Harkless v. Sweeny Independent School Dist., 427 F.2d

319 (5th Cir. 1970) ..................... ..................................... 39

Hayes v. Seaboard Coast Line R.R. Co., 46 F.R.D. 49

(S.D. Ga. 1960) ................... .......... .........................14-15,38

Heirn v. Bridault, 37 Miss. 209 (1859) ........................... 31

Hines v. Imperial Naval Store Co., 101 Miss. 802, 58

So. 650 (1911) .................................................................. 41

Hipp v. Babin, 60 U.S. 19 (1857) ..... ............................. 44

Horner v. Harvey, 3 N.Mex. 307, 5 P. 329 (1885) ....... 35

Hundley v. Milner Hotel Management Co., 114 F. Supp.

206 (W.D. Ky. 1953) ...................................................... 34

PAGE

40

I.H.P. Corp. v. 210 Central Park South. Corp., 228

N.Y.S.2d 883, 16 A.D.2d 461 (1962) ...........................

Imperial Shale Brick Co. v. Jewett, 169 N.Y. 143, 62

N.E. 167 (1901) .... ............... ............. ............................

In Be Consolidated Properties, No. 228 (Ohio Civil

Bights Commission), EQH If 17,506 (1972) ...............

International Bankers Life Ins. Co. v. Holloway, 368

S.W.2d 567 (Tex. 1963) ..................................................

Jackson v. Concord Company, 45 N.J. 113, 253 A.2d

793 (1969) ....... ............. ............... .......... ..........................

Jacoby v. Wiggins, No. II-1582 (Pa. Human Belations

Commission), EOH If 17,502 (1972) .... ......... ............

Johnson v. Georgia Highway Express, 417 F.2d 1122

(5th Cir. 1969) ......................... .......... .........................14,

Johnson v. Georgia Highway Express, 47 P.B.D. 327

(N.D. Ga. 1968) ............. ................................................

Jones v. Clifton, 101 U.S. 225 (1880) ..........................

Jones v. Mayer Co., 392 IT.S. 409 (1968) .................... 33,

Karns v. Allen, 135 Wis. 48, 115 N.W. 357 (1908) .......

Katchen v. Landy, 382 U.S. 323 (1966)..... ......... ....... 9, 48,

Keller Products, Inc. v. Bubber Linings Corp., 213

F.2d 382 (7th Cir. 1954) ......... ....................... ........... ..41-

Keltner v. Harris, 196 S.W. 1 (Mo. 1971) ...................

Kennedy v. Lakso Co., 414 F.2d 1249 (3d Cir. 1969) ....

Kisten v. Hildebrand, 48 Ky. 72 (1848) ...... ............ .......

Koehler v. Bowland, 275 Mo. 573, 205 S.W. 217 (1918)

Lawton v. Nightingale, 345 F. Supp. 683 (N.D. Ohio,

1972) .................................................................................

Le Blanc v. Southern Bell Telephone & Telegraph Co.,

333 F. Supp. 602 (E.D. La. 1971) .................. ............

Lea v. Cone Mills, C.A. No. C176-D-66 (N.D. N.C.

order dated March 25, 1968) ..........................................

40

14

41

14

14

38

14

30

36

40

50

-42

30

41

35

30

24

37

15

V I

Livingston v. Woodworth, 56 U.S. (15 How.) 546

(1854) ............................................................................... 40

Lord v. Malakoff, No. H-71-0062 (Md. Commission on

Human Relations), EOH If 17,503 (1972) ................... 14

Los Angeles Investment Co. v. Gary, 181 Cal. 680, 186

P. 596 (1919) ................... ................................................. 31

Lowry v. Whitaker Cable Corporation, 348 F. Supp.

202 (W.D. Mo. 1972) ......... 14

Lnria v. United States, 231 U.S. 9 (1913) ....................... 29

McElrath v. United States, 102 U.S. 426 (1880) ........... 29

Malat v. Riddell, 383 U.S. 569 (1966) .......................... 12

Marbury v. Madison, 1 Cranch (U.S.) 137 (1803) ...... 47

Marr v. Rife, Civ. No. 70-218 (S.D. Ohio, opinion dated

August 31, 1972) .......... 31

Middletown Bank v. Russ, 3 Conn. 135 (1819) ............... 40

Mitchell v. De Mario Jewelry, 361 U.S. 288 (1960) ____ 48

Mobile v. Kimball, 102 U.S. 691 (1881) ....................... 40

Moore v. Dempsey, 261 U.S. 86 (1923) ........................ 26

Moss v. Lane Company, 50 F.R.D. 122 (W.D. Va.

1970) .......... .................... 14

Moss v. Lane Company. 471 F.2d 853 (4th Cir. 1973) .... 16

Newman v. Piggie Park, 390 U.S. 400 (1968) .............. 37

N.L.R.B. v. Jones & Laughlin Steel Corp., 301 U.S. 1

(1937) ....... 13-14,28

Northwest Airlines, Inc. v. Airline Pilots Assn., Inti.,

373 F.2d 136 (8th Cir. 1967) ...................................... 29

Oceanic Steam Navigation Co. v. Stranahon, 214 U.S.

320 (1909) ........................................ 29

Ochoa v. American Oil Co., 338 F. Supp. 914 (S.D. Tex.

1972) ......... 14

Osage Oil & Refining Co. v. Chandler, 287 F. 848 (2d

Cir. 1923)

PAGE

30

V ll

Parker v. Dee, 2 Ch. Cas. 200, 22 Eng. Rep. 910 (Ch.

1674) ................................................................................. 40

Parker v. Flint, 12 Mod. Rep. 254 (1699) ....................... 35

Parmalee v. Morris, 218 Mich. 625, 188 N.W. 330

(1922) ............................................................................... 31

Parsons v. Bedford, 28 U.S. (3 Pet.) 433 (1830) ....... 27

Passavant v. United States, 148 U.S. 214 (1893) ....... 29

Pease v. Rathbun-Jones Engineering Co., 243 U.S. 273

(1917) ............................................................................... 40

People ex rel. Gaskill v. Forest Home Cemetery Co.,

258 111. 36, 101 N.E. 219 (1913) ................................... 30

Porter v. Warner Holding Co., 328 U.S. 395 (1946) .... 39

Queensborough Land Co. v. Cazeaux, 136 La. 724, 67

So. 641 (1915) ..... 31

Randolph Laboratories, Inc. v. Specialties Develop

ment Corp., 213 F.2d 873 (3d Cir. 1954) ................... 41

Rathbone v. Warren, 10 N.Y. 587 (1813) ....................... 40

Regina v. Rymer [1877], 2 Q.B.D. 136 ........................... 33

Rex v. Ivens [1835], 7 C. & P. 213, 173 Eng. Rep. 94

(N.P.) ........... 33-34

Rex v. Luellin [1700], 12 Mod.L.Rep. 445, 88 Eng. Rep.

141 (K.B.) .................... 33,35

Roberts v. Case Hotel Co., 106 Misc. 481. 175 N.Y.S.

123 (Sup. Ct. App. Term 1919) .................................. 35

Robins v. Grey [1895], 2 Q.B. 501 ........ .......................... 33

Robinson v. Lorillard Corporation, 444 F.2d 791 (4th

Cir. 1971) .................... ........... ........................................ 14

Robinson v. Pauley, No. H 29-72 (W. Va. Human

Rights Commission), EOH [[17,504 (1972) ............... 14

Rogers v. Clarence Hotel, 2 W.W.R. 545 (1940) .... ...... 35

Root v. Railway Co., 105 U.S. 189 (1882) ...................... 41

PAGE

V l l l

Ross v. Bernhard, 396 U.S. 531 (1970) .......................... 45-46

Rutland Marble Co. v. Ripley, 77 U.S. (10 Wall.)

339 (1870) ...... ............ ...................................................... 38

Scott v. Neely, 140 U.S. 106 (1891) .............................. 45

Sealey v. Tandy [1902], 1 K.B. 296 ................................... 34

Sexton v. Wheaton, 21 U.S. (8 Wheat.) 229 (1824) ....... 30

Seymour v. McCormick, 57 U.S. (16 How.) 480 (1853 ) 41

Shearer v. Porter, 155 F.2d 77 (8th Cir. 1946) ........... 42

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1 (1948) .......................... 31

Shepherd v. Florida, 341 U.S. 50 (1951) ....................... 26

Shorter v. Shelton, 183 Ya. 819, 33 S.E.2d 643 (1945) .... 34

Smith v. Hampton Training School for Nurses, 360

F.2d 577 (4th Cir. 1966) .............................................. 39

State v. Hicks, 174 N.C. 802, 93 S.E. 964 (1917) ........ . 35

State v. Steele, 106 N.C. 766, 11 S.E. 478 (1890) ____ 35

Stewart v. Griffith, 217 U.S. 323 (1910) ........................... 38

Stockton v. Russell, 54 F. 224, 228 (5th Cir. 1892) ....... 39

Swofford v. B. & W. Inc., 336 F.2d 406 (5th Cir.), cert.

denied 379 U.S. 962 (1964) ........................................... 41

Swoll v. Oliver, 61 Ga. 248 (1878) .................................. 31

Taylor v. Ford Motor Co., 2 F.2d 473 (N.D. 111. 1924) 41

Thompson v. Lacy [1820], 3 B. & Aid. 283, 106 Eng.

Rep. 667 (K.B.) .............................................................. 33-34

Tilghman v. Proctor, 125 U.S. 136 (1888) ....................... 41

Trafficante v. Metropolitan Life Insurance Co., 409

U.S. 205 (1972) ....................... ......................................... 36

Trop v. Dulles, 356 U.S. 86 (1958) .... .............................. 27

Union Oil Co. v. Reconstruction Oil Co., 20 Cal. App.2d

170, 66 P.2d 1215 (1937) ................................................ 41

United Cooperative Realty Co. v. Hawkins, 269 Ky.

563, 108 S.W.2d 507 (1937)

PAGE

31

IX

United States v. Ambac Industries, 15 F.R. Serv. 2d

PAGE

607 (D. Mass. 1971) ...................................................... 14

United States v. Barnett, 376 U.S. 681 (1964) ............... 25

United States v. Cooper Corporation, 312 U.S. 600

(1941) ...... 11

United States v. Debs, 64 F. 724 (N.D. 111. 1894) ....... 39

United States v. Di Re, 332 U.S. 581 (1948) .............. 27,49

Welby v. John Duke, of Rutland [1773], 2 Brown C. &

P. 39, 1 English Reports 778 (K.B.) ........................... 44

White v. White, 108 W. Va. 128, 150 S.E. 531 (1929) .... 31

Whitchurch v. Golding, 2 P. Wms. 541, 24 Eng. Rep.

852 (Ch. 1729) .... 40

Whitehead v. Shattuck, 138 U.S. 146 (1891) ................... 44

Wickwire v. Reinecke, 275 U.S. 101 (1929) ................... 29

Willard v. Taylor, 75 U.S. (8 Wal.) 557 (1870) ........... 38

William Whitman Co. v. Universal Oil Products Co.,

125 F. Supp. 137 (D. Del. 1954) ................................... 41

Williams v. Joyce, 4 Ore. App. 482, 479 P.2d 513

(1971) ........................ 14

Williams v. Travenol Laboratories, 344 F. Supp. 163

(N.D. Miss. 1972) .......................................................... 14

Wirtz v. Wheaton Glass Co., 253 F. Supp. 93 (D. N.J.

1966) ................................................................................. 29

Wyatt v. Adair, 215 Ala. 363, 110 So. 801 (1926) ....... 30

Yakus v. United States, 321 U.S. 414 (1944) ............... 39

Statutes:

7 U.S.C. § 135g(b) ..... 12,13

7 U.S.C. § 136k ................ ........... ................................. 13

7 U.S.C. § 1595 ............................................................. 13

9 U.S.C. § 4 ................................................................. 11,13

X

11 U.S.C. § 42 ...............................................................11,13

18 U.S.C. § 3691 .............................................................. 13

18 U.S.C. § 3692 ............................................................. 13

19 U.S.C. § 1305 ....... ................................ ..................... 13

21 U.S.C. § 334(b) .......................................................... 13

21 U.S.C. § 882 ................................................. .............. 13

21 U.S.C. § 1049 .............................................................. 13

25 U.S.C. § 1302 .............................................................. 13

28 U.S.C. § 384 ................................................................ 45

28 U.S.C. § 959 ............. .................................................. 13

28 U.S.C. §1254(1) .... ................................................... 2

28 U.S.C. § 1343 ................................ ................. ........... 21

28 U.S.C. § 1861 .............................................................. 21

28 U.S.C. § 1866 ............... ....................... ....................... 12

28 U.S.C. § 1872 .............................................................. 13

28 U.S.C. § 1873 ........................ ....... ............................. 13

28 U.S.C. § 1874 ........................................ ..... ............... i i

28 U.S.C. § 2402 .............................................................. 13

29 U.S.C. § 151 ................................................................ 28

39 U.S.C. § 840 ............................................................... 13

42 U.S.C. § 1971 .......... ................................................... 21

42 U.S.C. § 19731 ...... ........................................... ......... 23

42 U.S.C. § 1975 .............................................................. 21

42 U.S.C. § 1982 ............................................................. 33

PAGE

XI

42 U.S.C. § 1983 .............................................................. 24

42 U.S.C. §1995 ............................................ 13,17,21-22

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5 ......................... ................ ............. 23

42 U.S.C. § 2000e(f) .................. ............. ..................... 14

42 U.S.C. § 2000.li ........................................... ................ 23

42 U.S.C. § 3604(a) ................................ .......... ............ 2

42 U.S.C. § 3610 ............................................................11,13

42 U.S.C. § 3612 ................................................ 3,10,11, 36

42 U.S.C. § 3614 ........................................ ............... 36, 50

42 U.S.C. § 3615 ....... ...................................................... 13

46 U.S.C. § 688 ............................................................... 13

48 U.S.C. §413 ............................................... ................ 13

Emergency Price Control Act of 1942 ......... ............. 29

Jury Selection and Service Act of 1968 ...................... 12

Alaska Statutes, Title 18, § 22.10.020(c) ...................... . 13

Ark. Stat. Ann. 671-1801 (Suppl. 1961) ..................... . 36

California Civil Code § 35738(3) .................................. 13

G-enueral Statutes of Connecticut, § 53-36 ................ . 13

Del. Code Ann., tit. 24, § 1501 (1953) ........................... 36

Del. Code Anno., § 4605(e) ............................................ 13

Fla. Stat. Ann. §509.092 (1961) ...................... ........... 36

Hawaii Eev. Stat. § 515-13(b) ( 7 ) .................................. 13

Ind. Code § 22-9-6(k) ( i ) .................................................. 13

Iowa Code § 105A.9(12).......................................... ....... 13

PAGE

Kan. Stat. Anno. § 44-1019 .......................................... 13

Ky. Key. Stat, § 344.230 .......................................... ....... 13

Anno. Code Md. Article 49B, § 14(e) .......................... 13

Anno. Laws of Mass., Ch. 151 B, § 5 ........................... 13

Minn. Statutes, §363.071(2) .................. ....................... 13

Miss. Code Ann. § 2046.5 (1959).......................... .......... 36

N.H. Key. Stat. Anno. § 354-A :9 .................................. 13

N. J. Stat. Anno. § 10:5-17...................... ........ ............... 13

New Mex. Stat. Anno. § 4-33-10 E ................................ 13

N.Y. Executive Law § 297(4) (c) .......................... ........ 13

Ohio Kev. Code Anno., § 4112.05(g) .......................... 13

Ore. Kev. Stat. § 659-010-.110 ....................................... 14

Pa. Stat. Anno., Title 43, Ch. 17, § 959 ....................... 13

General Laws of R.I. § 34-7-5( L ) ...................... ....... . 13

S.D. Human Relations Act of 1972, L. 1972, S.B. I l l ,

§11(12) ......................................................................... 13

Tenn. Code Ann. § 62-710 (1955) .............................. . 36

Wash. Kev. Code § 49.60.225 .......................................... 13

W. Va. Code, § 5-11-10........... 13

Wise. Stat. Anno. § 101.60.............................................. 13

Other Authorities:

Federal Rules of Civil Procedure.......................6, 8,16,40

H.K. 1507, 75th Cong. 2d Sess..................................... 20

H.R. 4453, 81st Cong. 2d Sess...................................... 20

XIX

PAGE

X l l l

PAGE

H.R. 14765 89th Cong. 2d Sess. 12

S. 1358, 90th Cong. 1st Sess. 18

S. 3296, 89th Cong. 2d Sess. 15

Hearings Before a Subcommittee of the House Judi

ciary Committee, 89th Cong., 2d Sess. (1966) ....12,17-18

Hearings on S. 3296 before the Subcommittee on Con

stitutional Rights of the Senate Judiciary Com

mittee, 89th Cong., 2d Sess. (1966) ....... ............16-17-18

Hearing Before a Subcommittee of the Senate Bank

ing and Currency Committee, 90th Cong., 1st Sess.

(1967) ............................................................. ....... ..... 33

Hearings Before the Subcommittee on Housing and

Urban Affairs of the Senate Banking and Cur

rency Committee, 90th Cong., 1st Sess. (1967) ....18,49

82 Cong. Rec................................................................. 20

83 Cong. Rec............ 21

96 Cong. Rec................. 20-21

102 Cong. Rec................................................................21-22

103 Cong. Rec..........................................................21-22,26

106 Cong. Rec........................................... 23

110 Cong. Rec.................... 23

111 Cong. Rec............................................................. 24

112 Cong. Rec.... ............................................................ 15

114 Cong. Rec......................................... 32

118 Cong. Rec................................................................. 24

Halsburg, Laws of England (2d ed. 1935) ...........33-34-35

xiy

James, Civil Procedure (1965)...................................... 40

Moore’s Federal Practice ........... ............................. 9,12,16

Pomeroy, Equity Jurisprudence (5th ed. 1941) -37,40,42

Story on Bailments (4th ed. 1866) .............................. 35

Story, Equity Jurisprudence (14th ed. 1918) ........... 40

Garry, “Attacking Racism in Court Before Trial,”

Ginger, Minimizing Racism in Jury Trials (1969) 26

Hartman, “Racial and Religious Discrimination by

Innkeepers in the U.S.A.” 12 Mod. L. Rev. 449

(1950) ........................................................................... 35

Developments in the Law, Employment Discrimina

tion and Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964,

84 Harv. L. Rev. 1109... 25

Comment, The Right to Jury Trial Under Title VII

of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 37 U. Chi. L. Rev.

167 ................................................................................. 25

Note, The Right to Nonjury Trial, 74 Harv. L. Rev.

1176 (1961) - .... .......................... 25

Note, Jones v. Mayer: The Thirteenth Amendment

and the Federal Anti-Discrimination Laws, 69

Colum. L. Rev. 1019 .......... 25

Note, Hotel Law in Virginia, 38 Va. L. Rev. 815

(1952) ............ 35

Note, An Innkeeper’s ‘Right’ to Discriminate, 15

U. Fla. L. Rev. 109 (1962)

PAGE

35

I n the

(tart of % lotted States

October Term, 1973

No. 72-1035

J ulia R o g e r s ,

v.

Petitioner,

L eroy L oether and M ariane L oether, his wife,

and M rs. A n th o n y P erez

ON W R IT OF CERTIORARI TO T H E U N IT E D STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR T H E SE V E N TH CIRCUIT

BRIEF FOR PETITIONER

Opinions Below

The opinion of the District Court denying the demand

for jury trial is reported at 312 P. Supp. 1008, and is set

out in the Appendix (23a-28a). The opinion of the Dis

trict Court awarding punitive damages is unreported, and

is set out in the Appendix (47a-51a). The opinion of

the Court of Appeals is reported at 467 F.2d 1110, and is

set out in the Appendix (53a-73a).

2

Jurisdiction

The Court of Appeals entered judgment on September

29, 1972. On December 14, 1972, Mr. Justice Rehn-

quist extended tbe time for filing tbis petition to January

27, 1973. Tbe petition was filed on January 26, 1973, and

was granted on June 11, 1973. Jurisdiction of this Court is

invoked under 28 U.S.C. § 1254(1).

Question Presented

Whether Title V III of the 1968 Civil Rights Act or the

Seventh Amendment provide a right to jury trial to a

landlord in a civil action alleging that he refused to rent

an apartment to plaintiff because of her race and seeking

an injunction and punitive damages.

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved

1. United States Constitution, Amendment VII provides:

In suits at common law, where the value in contro

versy shall exceed twenty dollars, the right of trial

by jury shall be preserved, and no fact tried by a

jury, shall be otherwise reexamined in any Court of

the United States, than according to rules of the com

mon law.

2. Section 804(a) of the Civil Rights Act of 1968, 42

U.S.C. § 3604(a) provides :

As made applicable by section 803 and except as

exempted by sections 803(b) and 807, it shall be un

lawful—

(a) To refuse to sell or rent after the making of a

bona fide offer, or to refuse to negotiate for the sale

3

or rental of, or otherwise make unavailable or deny,

a dwelling to any person because of race, color, re

ligion, or national origin.

3. Section 812 of the Civil Rights Act of 1968, 42 U.S.C.

§ 3612, provides:

(a) The rights granted by sections 803, 804, 805,

and 806 may be enforced by civil actions in appropriate

United States district courts without regard to the

amount in controversy and in appropriate State or

local courts of general jurisdiction. A civil action

shall be commenced within one hundred and eighty

days after the alleged discriminatory housing practice

occurred: Provided, however, That the court shall

continue such civil case brought pursuant to this sec

tion or section 810(d) from time to time before bring

ing it to trial if the court believes that the conciliation

efforts of the Secretary or a State or local agency are

likely to result in satisfactory settlement of the dis

criminatory housing practice complained of in the com

plaint made to the Secretary or to the local or State

agency and which practice forms the basis for the

action in court: And provided, however, That any sale,

encumbrance, or rental consummated prior to the issu

ance of any court order issued under the authority of

this Act, and involving a bona fide purchaser, en

cumbrancer, or tenant without actual notice of the

existence of the filing of a complaint or civil action

under the provisions of this Act shall not be affected.

(b) Upon application by the plaintiff and in such

circumstances as the court may deem just, a court of

the United States in which a civil action under this

section has been brought may appoint an attorney for

the plaintiff and may authorize the commencement of

4

a civil action upon proper showing without the pay

ment of fees, costs, or security. A court of a State

or subdivision thereof may do likewise to the extent

not inconsistent with the law or procedures of the State

or subdivision.

(c) The court may grant as relief, as it deems ap

propriate, any permanent or temporary injunction,

temporary restraining order, or other order, and may

award to the plaintiff actual damages and not more

than $1,000 punitive damages, together with court costs

and reasonable attorney fees in the case of a prevail

ing plaintiff: Provided, That the said plaintiff in

the opinion of the court is not financially able to as

sume said attorney’s fees.

Statement of the Case

On November 7, 1969, plaintiff Julia Rogers commenced

this action in United States District Court for the Eastern

District of Wisconsin against Leroy and Mary Loether,

white owners of an apartment in Milwaukee, and their

agent Mrs. Anthony Perez. The complaint alleged the de

fendants had violated Section 804 of the Civil Rights Act

of 1968 by refusing to rent an apartment to Mrs. Rogers

because she is black. Plaintiff requested injunctive relief

and $1000 punitive damages hut neither alleged nor sought

actual damages (2a-6a). Jurisdiction of the District

Court was based on Section 812 of the Act. After an

evidentiary hearing on November 20, 1969, the court issued

a preliminary injunction forbidding rental of the apart

ment pending final determination of the action (16a-17a).

Defendants answered and demanded a jury trial of issues

of fact.

5

Subsequent to the granting of the preliminary injunction,

and at the urging of the District Court, repeated efforts

were made to settle this matter by arranging for the plain

tiff to move into the apartment at issue. Defendant Leroy

Loether, however, adamantly refused to rent it to her.

Finally, in April of 1970, five months after commencing

this action, plaintiff was forced to lease a different apart

ment, and consented to the lifting of the preliminary injunc

tion (47a).

On May 19, 1970, the District Court issued its opinion

and order denying defendants’ request for a jury trial

(23a-28a). The District Court concluded that Title V III of

the Civil Bights Act of 1968 authorized the trial judge

rather than a jury to assess damages, and that the court

could exercise this equitable power consistent with the com

mands of the Seventh Amendment. The District Court

awarded $250 in punitive damages, but no costs, attorneys

fees, or actual damages (47a-51a).

The Seventh Circuit reversed, holding that defendants’

jury trial demand should have been granted. The court’s

opinion centered on its conclusion that an action to enforce

Title V III of the Civil Rights Act of 1968 is “ in the nature

of a suit at common law” .

The court’s extended constitutional analysis culminated

in statutory interpretation. It found the district court’s

statutory analysis “persuasive but not compelling” and

concluded that the statute “ implies, without expressly

stating, that a jury’s participation is appropriate” when

damages are sought. In the end the court viewed as

“ controlling” a canon of construction requiring the inter

pretation of statutes to avoid “grave doubts” of unconsti

tutionality and concluded that Title V III of the Civil Rights

Act of 1968 itself requires jury trials when damages are

claimed.

6

Summary of Argument

I. a. The statutory language of Title VIII clearly con

templates that open housing cases arising thereunder shall

be tried by a judge without a jury. Section 812(c) directs

that “the court” may award damages and injunctive relief.

The word “court” is used elsewhere in the statute where

it can only refer to the judge, such as the provision in

section 814 authorizing the court to expedite these cases.

“ The court” is used to denote the trial judge, as opposed

to any jury, in the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure and

numerous statutes. Congress must be presumed to have

intended the “court” to have the same meaning throughout

Title VIII, and to have the same meaning with which it

was used by Congress elsewhere.

Had Congress desired to require a jury trial in these

cases, it would have done so expressly, using the words

“jury” or “ jury trial” , as it has in at least 22 other statutes.

b. At the 1966 Senate hearings on Title VIII, Attorney

General Katzenbach expressly testified that Title VIII did

not authorize jury trials. A committee member suggested

amending the bill to provide juries as to some issues, but

no such amendment was passed. The Attorney General’s

opposition to jury trials appears to have been based on

his concern, expressed elsewhere in the hearings, that juries

might refuse to enforce civil rights legislation.

As first proposed in 1966, Title VIII expressly provided

for a jury trial in certain cases of criminal contempt. The

different treatment of civil actions in the 1966 bill betokens

a different intent on the part of the draftsmen.

c. Title V III should not be interpreted as requiring

jury trials merely to avoid possible doubts as to its validity

under the Seventh Amendment, for there are equally im

7

portant constitutional policies which, might be adversely

affected by such a statutory requirement.

For 35 years great concern has been expressed in Con

gress that juries, particularly in the South, would refuse

to rule against white defendants in civil rights cases. Con

gressional proponents of civil rights legislation have con

sistently opposed jury trials in actions to enforce such

statutes on the ground that hostile juries would nullify

the proposed laws. Congress has granted a limited right

to jury trial in contempt cases arising under some civil

rights statutes, hut has refused to do so for civil enforce

ment proceedings. A jury trial requirement in Title VIII

cases might well defeat the statutory purpose of enforcing

the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments. Similarly,

a jury hostile to blacks or open housing would be unlikely

to afford an individual plaintiff her right to the fair hear

ing guaranteed by the Due Process clause of the Fifth

Amendment.

Plaintiff does not maintain that these constitutional con

siderations could prevent a jury trial if a jury were other

wise required by the Seventh Amendment. But since there

are constitutional policies militating both for and against

jury trials, the statute should be given its plain meaning

and its constitutionality under the Seventh Amendment

directly faced and resolved.

II. a. There is no constitutional right to a jury trial in

actions enforcing rights unknown at common law. This is

such a case. At common law the owner of real property

enjoyed unfettered discretion to refuse to sell or lease his

property to any person for any reason. This discretion

included the right to refuse to rent or lease property be

cause of the race of the would-be tenant or buyer. Title

V III was enacted for the purpose of reversing this principle

of common law.

8

The obligation of innkeepers at common law to serve all

travellers seeking shelter is of no relevance here. That

duty was limited to transients, not persons seeking perma

nent lodgings, and extended only to wonld-be guests who

had no home near the inn. Moreover in the United States

innkeepers were permitted to refuse to provide accommoda

tions because of the race of a traveller.

b. The various forms of relief available in a Title VIII

case are part of a single integrated equitable remedy. The

statute contemplates that the judge will fashion a remedy

in each case which will best promote the statutory policy

of equal access to housing. The award of actual or punitive

damages is discretionary, and in exercising that discretion

the court may well consider whether injunctive relief has

been awarded. Thus when, as here, actual or punitive dam

ages are awarded, that relief is not damages as they were

known at common law, but is part of an integrated equitable

remedy awarded only after consideration of the availability

and effectiveness of traditional equitable remedies.

c. Prior to the merger of law and equity by the Federal

Eules of Civil Procedure, courts of equity had the unques

tioned authority to award legal relief incidental to an

equitable claim without recourse to a jury. Both actual and

punitive damages were awarded in cases involving an

equitable claim where resolution of these legal issues was

essential to complete justice. This doctrine of equitable

cleanup was applied even where, as in the instant case, the

request for equitable relief was withdrawn or denied after

the commencement of the action. Thus before the promulga

tion of the Federal Eules in 1938, this case would have been

heard in equity and without a jury.

Since the merger of law and equity, this Court has ex

panded the right of jury trial in civil actions. Beacon

9

Theatres v. Westover, 359 U.S. 509 (1959). The meaning of

the Seventh Amendment, however, was not changed by the

Federal Exiles. Rather, Beacon Theatres and its progeny

apply an equitable practice, originating before the Seventh

Amendment, of declining to assume jurisdiction over cases

which could be adequately resolved at law so as to avoid

unnecessarily impairing the rights available in legal pro

ceedings. The instant case, however, involves a statutory

requirement that Title V III cases be tried to the court

without a jury. In such a case, as in Katchen v. Tandy,

382 U.S. 323 (1966), Beacon Theatres and its progeny are

inapplicable and the law must be upheld unless it violates

the Seventh Amendment itself. Since this case could have

been heard in equity in 1791, the statute is constitutional.

L

Title VIII Provides That All Issues Shall Be Tried

By a Judge Without a Jury.

a. Statutory Language

Congress has dealt in three ways with the question of

whether there should be a jury trial in, civil litigation

arising under Federal statutes. In some statutes Congress

has provided that all issues shall be tried before a judge

or referee alone, without a jury. See e.g., Katchen v.

Landy, 382 U.S. 323, 328-336 (1966) (Bankruptcy Act). A

second group of statutes require that some or all issues

must be decided by a jury, regardless of whether a jury

trial is mandated by the Seventh Amendment. See 5

Moore’s Federal Practice §38.12; note 2, infra. A third

class of statutes make no reference to the trier of fact,

leaving the question of jury trial vel non to be resolved

solely by reference to the Seventh Amendment. See e.g.,

10

Beacon Theatres v. Westover, 359 U.S. 500, 504 (1959)

(Declaratory Judgment Act).

In the instant case plaintiff submits that Title V III of

the 1968 Civil Rights Act requires that all questions of

law and fact in any action arising thereunder be decided

by the judge, not by a jury. The District Court construed

that statute in this manner. (26a-28a). The defendants

have heretofore maintained that Title V III neither required

nor forbade a jury trial, and that the question must be

resolved by reference to the Seventh Amendment. Hear

ing of April 30, 1970, pp. 2, 13; Brief for Defendant-

Appellant, p. 18; District Court Brief In Support of Jury

Trial, p. 6. The Court of Appeals went beyond the posi

tion urged by defendant and held that Title VIII requires

a jury trial (71a-73a).

The express language of the statute clearly indicates that

the court, not a jury, is to decide whether to award dam

ages. Section 812(c) of the Civil Rights Act of 1968, 42

U.S.C. § 3612(c), provides:

The court may grant as relief, as it deems appropriate,

any permanent or temporary injunction, temporary

restraining order, or other order, and may award to

the plaintiff actual damages and not more than $1,000

punitive damages, together with court costs and rea

sonable attorney fees in the case of a prevailing plain

tiff. Provided, that the said plaintiff in the opinion of

the court is not financially able to assume said attor

ney’s fees. (Emphasis added)

The meaning of “ the court” is undeniably the same through

out this section. The entity authorized to award actual and

punitive damages is the same entity authorized to grant in

junctive relief, temporary restraining orders, court costs,

11

and attorney’s fees. It is beyond question that only the trial

judge, sitting without a jury, would pass on injunctive re

lief or costs and fees, and the statutory language requires

that the question of damages be resolved in the identical

manner.

The phrase “ the court” is used elsewhere in Title VIII

in a context where it can only refer to the trial judge sit

ting alone, not a jury or the judge with a jury. In litigation

following the failure of conciliation under the statute, it is

“ the court” which may enjoin discrimination or order af

firmative action. 42 U.S.C. § 3610(d). If, after the com

mencement of litigation, conciliation efforts appear likely

to result in a settlement, “ the court” is required to continue

the case. 42 U.S.C. § 3612(a). “ The court” is authorized,

under circumstances it deems just, to appoint an attorney

for a plaintiff in civil litigation under the Act. 42 U.S.C.

§ 3612(b). Any “ court” in which a Title V III case is insti

tuted must expedite it in every way. 42 U.S.C. § 3614.

When the same words are used in different parts of the

same statute, they should be construed as having the same

meaning throughout. United States v. Cooper Corporation,

312 U.S. 600, 607 (1941).

In numerous other statutes the phrase “the court” is

used not merely to denote the trial judge, but to distin

guish a trial judge from any jury. “The court” is to assess

the issue in contractual forfeiture cases unless a jury is

requested by either party. 28 U.S.C. § 1874. In arbitration

cases where a jury is authorized and requested, “ the court”

refers the appropriate issues to the jurjr and “the court”

issues the appropriate order thereafter. 9 U.S.C. § 4. An

involuntary bankrupt is entitled to a jury as to certain

issues, and the bankruptcy proceeding must be postponed

if a jury is demanded and no jury is in attendance upon

“the court.” 11 U.S.C. § 42. In proceedings to condemn a

12

variety of substances, “ the court” directs the manner of

disposal or destruction of the goods after the jury, if re

quested, has found they are in violation of the law. 7 U.S.O.

§§135g(b), 136k, 1595; 21 U.S.C. §1049. The statutory

right to a jury trial in certain cases does not apply to

contempts committed in the presence of “the court.” 18

U.S.C. §§3691, 3692; 42 U.S.C. §§ 1995, 2000h. The phrase

“ the court” is used in the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure

to denote the trial judge, particularly to describe responsi

bilities of a judge as distinguished from those of a jury.

Federal Rules of Civil Procedure 39, 47, 49, 50, 51, 52,

53(e) (3), 57. Congress must be assumed to have been aware

of this widely accepted meaning of the phrase “ the eourt”

when it used that phrase in Title VIII. Malat v. Riddell,

383 U.S. 569 (1966); Banks v. Chicago Grain Trimmers

Association, 390 U.S. 459, rehearing den. 391 U.S. 929.

Particularly significant is the use of “the court” to de

note the trial judge throughout the Jury Selection and

Service Act of 1968. That statute provides that “ the court”

may allow extra preemptory challenges, “ the court” passes

on challenges for cause, “ the court” orders that names of

prospective jurors be drawn, “ the court” may excuse jurors

from service, “ the court” may order that jury records be

retained for more than four years, and “ the court” is to

pass on challenges to the jury selection procedure. 28

U.S.C. §§ 1866-1870. These provisions were first proposed

as Title I of the Civil Rights Act of 1966, the same bill

which contained in Title IV the open housing provisions at

issue in this case. See generally Hearings Before a Sub

committee on Constitutional Rights of the House Judiciary

Committee, 89th Cong. 2d Sess. (1966); H.R. 14765, 89th

Cong. 2d Sess.1 The Jury Selection Act was finally en

1 Section 406(c) of that bill was substantially the same as section

812(c) of the statute finally enacted. See p. 15 infra.

13

acted two weeks before Title V III in 1968. It must be

presumed that the draftsmen of the 1966 bill and the Con

gress which passed these laws two years later intended

“the court” to have the same significance in both.

Had Congress desired to require a jury trial, it would

have done so expressly as it has elsewhere. In at least 22

other statutes Congress has by law conveyed just such a

right, in each case using the words “ jury” or “jury trial.” 2

Congress clearly knew how to make known any desire

for jury trials in Title VIII cases; its failure to do so can

only betoken its intention to have those cases tried before

a judge. Had Congress wished to assure defendants jury

trials in Title VIII cases, it would not have authorized

state administrative proceedings in housing discrimination

cases, since such proceedings do not involve any right to

trial by jury. 42 U.8 .C. §§ 3610(c), 3615,3 * * * * * * 10 N.L.R.B. v. Jones

2 7 U.S.C. §§ 135g(b), 136k, 1595; 9 U.S.C. §4 ; 11 U.S.C. §42;

18 U.S.C. §§ 3691, 3692; 19 U.S.C. § 1305; 21 U.S.C. §§ 334(b),

882, 1049(a); 25 U.S.C. § 1302; 28 U.S.C. §§ 959, 1872, 1873, 1874,

2402; 39 U.S.C. § 840; 42 U.S.C. §§ 1995, 2000h; 46 U.S.C. § 688;

48 U.S.C. § 413.

3 At least twenty-four states have set up administrative agencies

empowered to award damages.

Eleven state statutes expressly mention damages. Alaska Stat

utes, Title 18, § 22.10.020(c) ; California Civil Code § 35738(3);

General Statutes of Connecticut, § 53-36; Hawaii Rev. Stat. § 515-

13(b) (7 ); Ind. Code §22-9-6 (k) (i) ; Anno. Laws of Mass., Ch. 151

B, § 5; Minn. Statutes, § 363.071(2); New Mex. Stat. Anno. § 4-33-

10 E ; N.Y. Executive Law § 297 (4) (c) ■ General Laws of R.I.

§ 34-7-5 (L) ; Wash. Rev. Code § 49.60.225. Twelve states authorize

their agencies to order any affirmative action necessary to carry

out the purposes of the state law. Del. Code Anno., § 4605(e);

Iowa Code §105A.9(12); Kan. Stat. Anno. §44-1019; Ky. Rev.

Stat. § 344.230; Anno. Code. Md. Article 49B, § 14(e) ; N.H. Rev.

Stat. Anno. § 354-A :9; N. J. Stat. Anno. § 10:5-17; Ohio Rev. Code

Anno., § 4112.05(G); Pa. Stat. Anno., Title 43, Ch. 17, § 959; S.D.

Human Relations Act of 1972, L. 1972, S.B. I l l , § 11(12) ; W. Va.

Code, § 5-11-10; Wise. Stat. Anno. § 101.60. These provisions have

uniformly been held to authorize orders directing the payment of

14

& LaugJilin Steel Corp., 301 U.S. 1 (1937); Edwards v.

Elliott, 88 U.S. 532, 557 (1874).

This construction of Title V III is supported by the word

ing and judicial interpretations of section 706 of the Civil

Eights Act of 1964, authorizing private actions to enforce

the Title V II ban on employment discrimination. Section

706(g), 42 U.S.C. § 2000e(f) (g), provides that “ the court”

may give injunctive relief and back pay.4 The lower courts

reaching this question have uniformly held that all issues in

a Title V II case should be heard and decided by a judge.6 * 4 5 *

damages. Jackson v. Concord Company, 45 N.J. 113, 253 A.2d 793

(1969); Robinson v. Pauley, No. H 29-72 (W. Va. Human Rights

Commission), Equal Opportunity in Housing [hereinafter “ EOH” ]

ft 17,504 (1972) ; Bridges v. Mendota Apartments, No. 898-H (D.C.

Commission on Human Rights), EOH ft 17,505 (1972); Jacoby v.

Wiggins, No. H-1582 (Pa. Human Relations Commission), EOH

ft 17,502 (1972) ; Lord v. Mala.koff, No. H-71-0062 (Md. Commission

on Human Relations) EOH ft 17,503 (1972); In Re Consolidated

Properties, No. 228 (Ohio Civil Rights Commission), EOH ft 17,506

(1972). The Oregon statute, Ore. Rev. Stat. § 659, 010-.110, au

thorizing orders to “ eliminate effects” of discrimination, has been

held to authorize awards of damages. Williams v. Joyce, 4 Ore.

App. 482, 479 P.2d 513 (1971).

4 “ If the court finds that the respondent has intentionally

engaged in or is intentionally engaging in an unlawful em

ployment practice charged in the complaint, the court may

enjoin the respondent from engaging in such unlawful em

ployment practice, and order such affirmative action as may

be appropriate, which may include reinstatement or hiring of

employees, with or without back pay.. .

5 Robinson v. Lorillard Corporation, 444 F.2d 791, 802 (4th Cir.

1971); Johnson v. Georgia Highway Express, 417 F.2d 1122 (5th

Cir. 1969) reversing 47 F.R.D. 327, 330-31 (N.D. Ga. 1968) ; Lowry

v. Whitaker Cable Corporation, 348 F. Supp. 202, 209 n.3 (W.D.

Mo. 1972); Williams v. Travenol Laboratories, 344 F. Supp. 163

(N.D. Miss. 1972) ; Ochoa v. American OH Co., 338 F. Supp. 914

(S.D. Tex. 1972); United States v. Anibac Industries, 15 F.R.Serv.

2d 607 (D. Mass. 1971); Gillin v. Federal Paper Board Co., Inc., 52

F.R.D. 383 (D. Conn. 1970) ; Moss v. Lane Company, 50 F.R.D. 122

(W.D. Ya. 1970) ; Cheatwood v. South Central Bell Tel. & Tel Co.,

303 F.2d 754 (M.D. Ala. 1959); Hayes v. Seaboard Coast Line R.R.

15

b. Legislative History

The legislative history of Title V III indicates that the

statute was intended to preclude jury trials in actions such

as this. A federal fair housing law was first proposed by

President Johnson as part of the Civil Rights Act of 1966.* 6

Section 406 of the administration bill, like section 812(c)

of the statute enacted two years later, authorized “the

court” to award damages.7 At the Senate hearings on

1966 Senator Ervin expressly inquired as to whether a

jury trial was provided by the proposed bill.

Senator Ervin. Now, I would like to know under

the same subsection (c) of section 408 [sic] who deter

mines the amount of damages that are to be awarded

if a case is made out under Title IV of the bill.

Attorney General Katzenbach. The court does.

Senator Ervin. That is the judge.

Attorney General Katzenbach. Yes, sir.

Senator Ervin. There is no jury trial.

Attorney General Katzenbach. No, sir.

Senator Ervin. Well, is the administration opposed

to or has it forsaken the ancient American love for

trial by jury!

Co., 46 F.R.D. 49 (S.D. Ga. 1969); Culpepper v. Reynolds Metals

Co., 296 F. Supp. 1232 (N.D. Ga. 1968), rev’d on other grounds

421 F.2d 888 (5th Cir. 1970); Lea v. Cone Mills, Civil Action No.

C176-D-66 (N.D. N.C., order dated March 25, 1968); Banks v.

Local 136, I.B.E.W., Civil Action No. 67-598 (N.D. Ala., order

dated January 25, 1968) ; Anthony v. Brooks, 67 LRRM 2897

(N.D. Ga. 1967). Lea, Banks and Anthony were decided prior to

the enactment of Title VIII.

6112 Con. Rec. 9390 (1966).

7 “ The court may grant such relief as it deems appropriate,

including a permanent or temporary injunction, restraining

order, or other order, and may award damages to the plaintiff,

including damages for humiliation and mental pain and suffer

ing, and up to $500 punitive damages.” S. 3296, § 406(c),

89th Cong. 2d Sess., 112 Cong. Rec. 9397 (1966).

16

Attorney General Katzenbaeh. No, sir. I assume if

there was a suit here that was for purely damages that

the court would use a jury.

Senator Ervin. Would the administration have any

objection to subsection (c) being amended to spell out

the fact that a man has a right to have the issues of

fact arising in the case and the amount of damages

determined by a jury instead of the judge.

Attorney General Katzenbaeh. No, in a damage suit

I have no objection to that. With respect to the equi

table relief I would, obviously.8

Neither an amendment like that proposed by Senator Ervin,

providing for a jury trial on all issues of fact, nor an

amendment like that acquiesced to by Attorney General

Katzenbaeh, providing for a jury trial as to damages, was

passed by the Congress. Instead this provision was enacted

two years later in essentially the form objected to by Sen

ator Ervin.9 The reason for the Attorney General’s op

position to jury trials in Title V III cases was made clear

elsew’here. At a House hearing that year on the same Act

8 Hearings on S. 3296 before the Subcommittee on Constitutional

Rights of the Senate Committee on the Judiciary, 89th Cong., 2nd

Sess., pt. 2, 1178 (1966).

9 Attorney General Katzenbach’s prediction that courts would

use juries in damage only actions seems to refer to the use of

advisory juries. See Rule 39(c) Federal Rules of Civil Procedure.

The term “use” as applied to juries is generally employed to de

scribe the role given an advisory jury, not a jury sitting as the

ultimate trier of the faets. See 5 Moore’s Federal Practice 39.10.

Such advisory juries have in fact been used under the similar

provision of Title VII. Cox v. Babcock and Wilcox Company, 471

F.2d 13 (4th Cir. 1972) ; Moss v. Lane Company, 471 F.2d 853

(4th Cir. 1973). The Attorney General’s assumption regarding

future practice under Title VIII does not purport to be a con

struction of those provisions. For reasons set forth infra, pp. 27

and 39, a jury trial would not be constitutionally required in an

action seeking only damages.

17

Attorney General Katzenbach. was asked Ms views on a

proposed bill creating a civil action for damages on behalf

of victims of civil rights related violence. He responded

candidly, “I would not be sanguine in such community

about the capacity to recover from a jury in that situation.

I would be inclined to doubt it might occur.” 10 The At

torney General expressed similar reservations about the

likelihood of obtaining convictions from any jury under a

proposal to make criminal economic coercion in civil rights

cases.11

This construction of section 812(c) is supported by the

treatment of jury trials in contempt cases during the legis

lative history of Title VIII. The first proposed provision,

Title IV of the 1966 Civil Rights Act, expressly directed

that in any contempt proceeding for violation of any in

junction under that Title the defendant would be entitled

to a trial de novo before a jury if the court upon convic

tion set a fine in excess of $300 or imprisonment for more

than 45 days.12 Attorney General Katzenbach testified he

10 Hearings Before a Subcommittee of the House Judiciary Com

mittee, 89th Cong., 2d Sess., 1183 (1966). The Civil Rights Act

of 1966 and 1968 proposed by the President dealt with discrimina

tion in jury selection as well as in housing. The Fair Housing Law

and the Jury Selection and Service Act were enacted within weeks

of each other in 1968. See p. 12 supra. The instant hearings

dealt with both problems, and included testimony regarding the

refusal of southern juries to convict white defendants in civil rights

eases. See e.g. Id. at 1321 (Remarks of Congressman Ryan), 1331

(Remarks of Congressman Diggs), 1142 (Remarks of Roy Wil

kins) , 1519 (Remarks of Whitney Young).

11 Hearings on S. 3296 before the Subcommittee on Constitutional

Rights of the Senate Judiciary Committee, 89th Cong., 2d Sess.

175-176 (1966).

12 Section 410 of the bill provided: “All cases of criminal con

tempt arising under the provisions of this title shall be governed

by section 151 of the Civil Rights Act of 1957 (42 U.S.C. 1995).”

Section 1995 provides in pertinent part:

In all cases of criminal contempt arising under the provi

sions of this Act, the accused, upon conviction, shall be pun-

18

supported this limited right to jury trial as “ a quite wise

balance between the need of the Court to have respect and

to vindicate its own decisions, and for the right of the in

dividual not to have any major encroachments on his free

dom and liberty without the benefit of trial by jury.” 13

The proposed Fair Housing Act of 1967, supported by the

administration, made no express reference to the problem

of criminal contempts,14 tacitly relegating that matter to the

inherent power of the courts to enforce their decrees

and the limitations thereon imposed by this Court.

Cheff v. SchnacJcenberg, 384 TJ.S. 373 (1966).15 Similarly

the bill finally enacted by Congress in 1968 deleted this jury

trial requirement. Had the original draftsmen of section

ished by fine or imprisonment or both: Provided, however,

That in case the accused is a natural person the fine to be

paid shall not exceed the sum of $1,000, nor shall imprison

ment exceed the term of six months: Provided further, That

in any such proceeding for criminal contempt, at the discre

tion of the judge, the accused may be tried with or without

a jury: Provided further, however, That in the event such

proceeding for criminal contempt be tried before a judge

without a jury and the sentence of the court upon convic

tion is a fine in excess of the sum of $300 or imprisonment

in excess of forty-five days, the accused in said proceeding,

upon demand therefor, shall be entitled to a trial de novo

before a jury, which shall conform as near as may be to the

practice in other criminal cases.

13 Hearings Before a Subcommittee of the House Judiciary Com

mittee 89th Cong., 2d Sess. 1238-39 (1966) ; see also Hearings Be

fore the Subcommittee on Constitutional Rights of the Senate

Judiciary Committee, 89th Cong., 2d Sess. 17 (1966).

14 S. 1358, 90th Cong., 1st Sess.; see Hearings Before the Sub

committee on Housing and Urban Affairs of the Senate Banking

and Currency Committee, 90th Cong., 1st Ses. 1-7 (1967) (Testi

mony of Attorney General Clark).

15 The right to jury trial afforded by the Sixth Amendment is,

in general, limited to cases involving sentences in excess of six

months. Bloom v. Illinois, 391 U.S. 194 (1968). The jury trial

authorized by the 1966 bill covered sentences exceeding 45 days as

well as fines of more than $300. See n. 12 supra.

19

812(c) in 1966 desired jury trials in civil actions there

under, they would have said so expressly as they did at

first regarding criminal contempts. It is unlikely that Con

gress, having considered and declined to authorize jury

trials in such contempt cases, would have required such

trials in civil actions whose consequences to a defendant

were far less serious.

c. Constitutional Consideration

The Court of Appeals refused to construe Section 812 as

requiring that all issues he tried to a judge because of its

“grave doubts” as to the constitutionality of the statute if

so construed. The Court of Appeals applied the established

canon of construction that, where fairly possible, statutes

should be interpreted so as to avoid serious question as to

their constitutionality (Pp. 71a-73a). That canon, however,

has no application where important constitutional consider

ations militate in favor of both alternative constructions

under consideration. In this case the statutory require

ment that these cases be tried to judges rather than juries

is essential to carrying out the Act’s purpose of enforcing

the guarantees of the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amend

ments, and to assure to plaintiffs the fair trial guaranteed

by the Due Process Clause of the Fifth Amendment. Under

such circumstances the canon can provide no guidance, and

the Court must construe the statute in view of its language

and history and then resolve any constitutional questions

which may arise.

Congress’s decision to bar jury trials in Title VIII eases

occurred in the context of 35 years of congressional con

cern, debate and legislation concerning the role of juries

in civil rights legislation. For several generations after

Reconstruction Congress took no action to effectuate the

guarantees of the Thirteenth, Fourteenth and Fifteenth

2 0

Amendments. During the 1930’s federal legislation was

proposed under the Fourteenth Amendment to deal with

lynchings in the South. One of the few such proposals to

reach the floor of either house was a bill introduced by

Senator Wagner to authorize criminal and civil damage

actions against public officials or local governments which

failed to prevent such lynchings.16 Senator Bailey of North

Carolina, opposing the bill, openly predicted that southern

juries would refuse to enforce the law.

I say to the Senate that when that kind of suit is

brought, in the first place, the jury in the county is

not going to bring in a verdict for the Attorney Gen

eral of the United States. Oh no—we are not going

to think of doing such a thing. . . . I have tried cases

for 25 years in the United States and in the state

courts of North Carolina, and I have never known

any difference as to juries. They are a fine body of

men in either circumstance, but they are men who have

a sense of loyalty to their county and a sense of loyalty

to their people.17

The anti-lynching bill never came to vote. In 1949 Con

gressman Powell of New York proposed a Fair Employ

ment Practices Act to end racial discrimination in hiring

and promotion.18 Representative Powell proposed that en

forcement be entrusted to a Fair Employment Practices

Commission similar to the National Labor Relations Board,

in part because “commission procedure avoids the neces

sity of criminal penalties which juries hesitate to invoke.”

96 Cong. Rec. 2168. This denial of a right to trial by

16 H.R. 1507, 75th Cong. 2d Sess.

17 82 Cong. Rec. 77 (1937); see also 83 Cong. Ree. 141 (1938)

(Remarks of Senator Borah).

18 H.R. 4453, 81st Cong. 2nd Sess.

21

jury was objected to by opponents of the bill, 96 Cong.

Rec. 2177, 2182, 2200, 2201, 2203, 2204, 2249, and an amend

ment to deny enforcement powers to the Commission was

narrowly passed, 96 Cong. Rec. 2253. The bill was ap

proved by the House only to die in the Senate.

The conflict between the use of jury trials and the ef

fective enforcement of civil rights legislation was fully

aired in the debates leading to the Civil Rights Act of

1957.19 When the bill was first proposed in 1956, Attorney

General Brownell asked for civil rather than criminal sanc

tions so as to avoid jury trials, 102 Cong. Rec. 13141, and

the administration bill provided there would be no jury

trial in contempt prosecutions for violation of injunctions

obtained by the United States. Proponents of the bill ar

gued at length that jury trials for contempt would nullify

the statute, since racially prejudiced purors would refuse

to convict.20 Numerous instances were cited in which south

ern juries had refused to indict or convict white defendants

accused of violence against blacks or civil rights workers.21

19 71 Stat. 634; see 28 U.S.C. §§ 1343, 1861; 42 U.S.C. §§1971,

1975-1975e, 1995.

20 102 Cong. Rec. 13175. (Remarks of Congressman Roosevelt) ;

102 Cong. Ree. 8409 (Remarks of Congressmen Madden, Scott),

8412 (Remarks of Congressman Keating), 8418 (Letter from the

Attorney General), 8488 (Remarks of Congressman Chudoff), 8505

(Remarks of Congressman Addonizio), 8509 (Remarks of Congress

man Pelley), 8535 (Remarks of Congressman Hillings), 8648 (Re

marks of Congressman Dennison), 9193 (Remarks of Congress

man Powell), 9216 (Remarks of Congressman Ashley), 12801

(Remarks of Senator Morse), 13312 (Remarks of Senator Know-

land), 13316-17 (Remarks of Senator Morse), 13334 (Remarks of

Senator Douglas).

21103 Cong. Rec. 8490 (Remarks of Congressman Celler), 12535

(Remarks of Senator Javits), 12588 (Remarks of Senator Hum

phrey), 12848 (Remarks of Senator Case), 12893 (Remarks of

Senator Javits). See also n. 10, supra.

2 2

Senator Douglas urged:

[0]bvious[ly], southern juries . . . will tend to have

color bias to begin with. Second, . . . at the termin

ation of their service they must go back into the com

munities from which they came and be exposed to all

the economic, social and at times physical pressures

which may be brought to bear. . . . [I] t would be ex

tremely difficult to obtain any deserved enforcement.

. . . [Judges] tend to have greater respect for the

law . . . [and] are somewhat insulated from the pas

sions and prejudices of their community.22

Proponents of a jury trial requirement repeatedly insisted

that the right to trial by jury should apply to criminal con

tempts as to all other crimes, as a matter of policy or con

stitutional law.23 The House rejected a jury trial require

ment in contempt cases, 103 Cong. Bee. 9219, but the Senate

adopted an amendment authorizing jury trials, 103 Cong.

Bee. 13356, and the statute finally enacted provided a lim

ited right to such trials. 42 U.S.C. § 1995.24

Since the 1957 debates the dispute has continued with

varying results. In the 1960 Civil Bights Act Congress

22 103 Cong. Rec. 12804.

28 102 Cong. Ree. 13180 (Remarks of Congressman Rivers) ; 103

Cong. Rec. 2014 (Minority Report), 8414 (Remarks of Congress

man Colmer), 8501 (Remarks of Congressman Hyde), 8502 (Mr.

Winstead), 8508 ) Remarks of Congressman Poff), 8545 (Remarks

of Congressman Abiff), 8552 (Remarks of Congressman Brown),

8559 (Remarks of Congressman Abernethy), 8649 (Remarks of

Congressman Smith), 8655 (Remarks of Congressman Tuck), 8657

(Remarks of Congressman Davis), 8666 (Remarks of Congress

man Ashmore), 8839 (Remarks of Congressman Smith), 9042 (Re

marks of Congressman Walter), 12531 (Remarks of Senator

O’Mahoney), 12571 (Remarks of Senator O’Mahoney), 12651 (Re

marks of Senator Johnson), 13005 (Remarks of Senator Ervin)

13326 (Remarks of Senator Church). Congressman Poff also denied

southern juries would refuse to enforce the law. 103 Cong. Ree.

8509.

24 Supra, n. 12.

23

gave the courts power to enjoin certain discriminatory con

duct without providing jury trials for contempt, despite the

objection that this was part of “ the growing tendency to

do away with the jury system in the Federal courts.” 25

The 1964 Civil Rights Act provided a right to jury trials

in most cases of contempt, 42 U.S.C. § 2000h, but provided

for non-jury trial civil actions arising in employment dis

crimination cases. 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5; see n. 5, supra.

As in 1957, the contempt jury trial provision was rejected

by the House but imposed by the Senate,26 and the debate

closely resembled that of 1957.27 That no jury trial would

be available in civil actions for injunction and back pay

was reiterated in the Senate debates by one of the bills’

floor managers, in response to repeated questions by Sen

ator Ervin; neither Senator Ervin nor any other proponent

of jury trials in contempt cases asked for such trials in

civil enforcement proceedings.28 In the 1965 Voting Rights

Act Congress gave the limited right to jury trial in con

tempt cases provided by the 1957 Act, 42 U.S.C. § 19731,

26 1 06 Cong. Rec. 6375 (Remarks of Congressman Brooks) ; Sen

ator Clark urged, “ Certainly one cannot be confident that a jury

drawn from the citizens in the southern district of Mississippi

would be eager to make such a finding in favor of Negro fellow

citizens who have been denied the right to vote! . ” 106 Cong

Rec. 7241.

26110 Cong. Rec. 2804 (House Vote), 13051 (Senate Vote).

27 For arguments that jury trials would emasculate the law, see

110 Cong. Rec. 1993 (Remarks of Congressman Taft), 2266 (Re

marks of Congressman Gilbert), 8660 (Remarks of Senator Morse),

9818 (Remarks of Senator Javits), 12958 (Remarks of Senator

Humphrey). Advocates of jury trials once again pointed to the

Constitution, 110 Cong. Rec. 8700 (Remarks of Senator Fulbright),

9565 (Remarks of Senator Johnston), 9681 (Remarks of Senator

Long). See generally 110 Cong. Rec. 9572-3, 10164-5, 2272 8649-

57, 8700-8703, 10077-80, 10563-4, 12926, 11204-5, 10340-1, 9685-6

10203-09, 9817-19, 9917-19, 10111, 11012, 10199-203, 12953-4

13050-1.

28110 Cong. Rec. 7693. Senator Ervin did make such a proposal

eight years later. See n. 30, infra.

24

the House having rejected, after brief debate, an amend

ment that would have required jury trials in all contempt

cases. I l l Cong. Rec. 16263. The proponents of open hous

ing legislation first proposed and then deleted the limited

jury trial right in contempt cases in the 1957 statute, and

the Congress which enacted Title VIII also established new

rules to prevent racial discrimination in the selection of

federal juries.29

In sum, Congress, out of a repeatedly expressed concern

that juries would refuse to enforce civil rights legislation,

has provided only a limited right to jury trial in criminal

contempt cases arising under such enactments, and has con

sistently refused to sanction jury trials in civil enforce

ment proceedings.30 A similar concern has been expressed

by a number of lower courts in enforcing civil rights leg

islation.31

29 See supra, p. 12.

20 In 1972 Senator Ervin proposed to require jury trials in Title

VII civil actions, conceding the Seventh Amendment did not apply

to such equitable proceedings but urging that its salutary policies

should be enforced in all such cases. Senator Javits objected, “ If

it is valid for this, why is it not valid for all proceedings under

the 14th amendment, which would include education, housing, and

everything else in the Civil Rights Act of 1964?” The proposal

was rejected. 118 Cong. Rec. 2277-2278 (Feb. 22, 1972) (Daily

Ed.).

31 The District Court at oral argument on the jury trial motion

in this case:

“ [T]his issue has been debated as long as I can remember in

Congress and all the civil rights legislation passed since 1948,

I believe. And I think the general consensus is that if you

have jury trials, civil rights legislation, you don’t really re

sult in very effective legislation, so Congress—pro civil rights

people shred away from it.” Hearing of April 30, 1970, p. 13.

In Lawton v. Nightingale, 345 P.Supp. 683, 684 (N.D. Ohio, 1972),

the district court held there was no right to a jury trial for dam

ages under 42 U.S.C. § 1983:

“ [A] contrary holding would, in many instances, totally defeat

the purposes of § 1983. If a jury could be resorted to in

25

The constitutional policies which, such legislation en

forces, in this case those of the Thirteenth and Fourteenth

Amendments, are no less important than those of the Sev

enth. Plaintiff does not maintain that the protections of the

Bill of Bights should not extend to defendants in civil rights

cases; on the contrary, plaintiff recognizes that those pro

tections, including the right to jury trial, are a bulwark

against government oppression, and should not be withheld

even in the name of liberty itself. Compare United States

v. Barnett, 376 U.S. 681 (1964). A seriously delibitating

limitation on Title V III may be imposed if unequivocally

required by the Seventh Amendment, but should not be

merely because of “ serious doubts.” The Court should ac

cord section 812 its natural interpretation as prohibiting

jury trials, and resolve explicitly the Seventh Amendment

questions posed by that construction.32

actions brought under this statute, the very evil the statute