Calhoun v. Latimer Brief for Petitioners

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1964

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Calhoun v. Latimer Brief for Petitioners, 1964. c844db81-ac9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/7d435e71-9611-4785-a846-507d1e26b892/calhoun-v-latimer-brief-for-petitioners. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

v

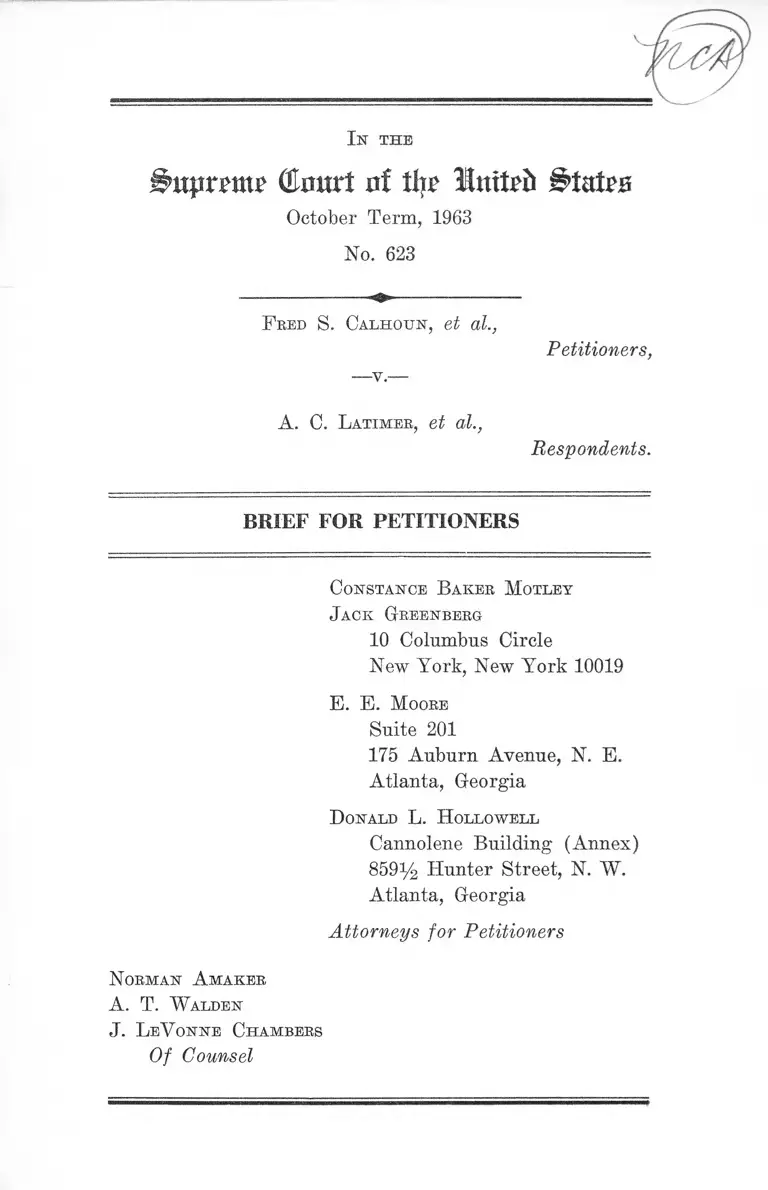

I n the

Glmtrt of Up Inttfb States

October Term, 1963

No. 623

F red S. Calh o u n , et at.,

Petitioners,

A. C. L atim er , et al.,

Respondents.

BRIEF FOR PETITIONERS

Constance B aker M otley

J ack Greenberg

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

E. E. M oore

Suite 201

175 Auburn Avenue, N. E.

Atlanta, Georgia

D onald L . H ollowell

Cannolene Building (Annex)

859% Hunter Street, N. W.

Atlanta, Georgia

Attorneys for Petitioners

N orman A makeb

A . T. W alden

J . L eV onne Chambers

Of Counsel

I N D E X

PAGE

Opinions B elow ................................................................... 1

Jurisdiction ......................................................................... 2

Constitutional Provision Involved.................................. 2

Question Presented ............................................................ 2

Statement ............................................................................. 2

Argument

The Plan Erroneously Approved Below Does Not

Conform to the Mandate of This Court; the Plan

Desegregates Too Little, Too L ate.......................... 7

Conclusion ............... 18

Table of Cases

Augustus v. Board of Public Instruction, 306 P. 2d 862

(5th Cir. 1962) ............................................................. 5, 6, 9

Board of Public Instruction of Duval County v, Brax

ton, 5th Cir., No. 20294, January 10, 1964 .................... 16

Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, 347 U. S.

483 ......................................................................... ..... 2, 5, 7, 9

Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, 349 U. S.

294 ......... ................... .................................. ...................2, 5, 9

Bush v. Orleans Parish School Board, 308 F. 2d 491

(5th Cir. 1962) ....................................................... 5, 6,10,15

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1 ............................................ 5, 9

Evans v. Ennis, 281 F. 2d 385 (3d Cir. 1960) ............... 15

11

PAGE

Farmer v. Greene County Board of Education, 4th Cir.,

No. 9125 ........................................................................... 11

Goss v. Board of Education of the City of Knoxville,

373 U. S. 683 ....................................... ............................5,14

Goss v. Board of Education of the City of Knoxville,

301 F. 2d 164 (6th Cir. 1962), reversed on other

grounds, 373 U. S. 683 ....................... ............................ 15

Green v. School Board of the City of Roanoke, 304 F.

2d 118 (4th Cir. 1962) .................................................... 11

Jackson v. School Board of the City of Lynchburg,

321 F. 2d 230 (4th Cir. 1963) ........................................ 15

Jeffers v. Whitley, 309 F. 2d 621 (4th Cir. 1962) ....... 11

Jones v. School Board of the City of Alexandria, 278

F. 2d 72 (4th Cir. 1960) ..................................................5,11

Northcross v. Board of Education of the City of Mem

phis, 302 F. 2d 818 (6th Cir. 1962) ...................5,11,12,13

Shuttlesworth v. Birmingham Board of Education, 358

U. S. 101, affirming 162 F. Supp. 372 (N. D. Ala,

1958) ................................................................................. 8

Watson v. City of Memphis, 373 IT. S. 526 .......................5,13

F edebal S tatute

United States Code, Title 28, §1254(1) .......................... 2

Othek A uthorities

Bickel, The Decade of School Desegregation, 64 Colum

bia Law Review 193 (1964) .......................................... 17

Southern Education Reporting Service, Statistical

Summary of School Segregation—Desegregation in

the Southern and Border States (1963-1964) ........... 7

In the

inprTmT (Emtrt nf tljr Hnttpit States

October Term, 1963

No. 623

F eed S. Calh o u n , et al.,

—v.—

Petitioners,

A. C. L atim ee , et al.,

Respondents.

BRIEF FOR PETITIONERS

Opinions Below

The District Court’s opinion denying further relief and

from which an appeal was taken to the court below is re

ported at 217 F. Supp. 614 and printed in the record at

page 156.

Prior Findings of Fact, Conclusions of Law, Orders and

Judgments of the United States District Court for the

Northern District of Georgia, Atlanta Division (R. 9, 18, 38,

43, 47, 48, 160, 165) are reported at 188 F. Supp. 401 and

188 F. Supp. 412.

The opinions of the United States Court of Appeals for

the Fifth Circuit, modifying and affirming the decision of

the District Court and denying petitioners’ petition for re

hearing en banc are printed in the record at 229, 258 and

reported at 321 F. 2d 302.

2

Jurisdiction

The judgment of the Court of Appeals was entered on

June 17, 1963 (R. 254). Application for rehearing en banc

was denied on August 16, 1963 (R. 259). The petition for

writ of certiorari was filed November 14, 1963 and granted

January 13, 1964. The jurisdiction of this Court is invoked

pursuant to 2S U. S. C. §1254(1).

Constitutional Provision Involved

This case involves Section 1 of the Fourteenth Amend

ment to the Constitution of the United States.

Question Presented

Respondent school authorities operate a biracial system

which, under court order, now allows children to transfer to

schools for the other race upon satisfying seventeen pupil

assignment criteria, leaving the dual system otherwise in

tact. This limited opportunity to transfer has been given on

a twelve year descending grade-a-year basis and is now

enjoyed by children in the 12th, 11th, 10th and 9th grades.

In 1972 children will still have only this limited right. Does

not Brown v. Board of Education impose upon respondents

the affirmative duty to (a) reorganize the schools into a

unitary non-racial system, and (b) to do so much more

quickly than in twelve years?

Statement

For approximately four years subsequent to this Court’s

decision in Brown v. Board of Education, of Topeka, 347

U. S. 4S3, the public schools of Atlanta remained segregated,

3

while Negro parents vainly petitioned local school authori

ties for redress (E. 4,163).

Then, on January 11, 1958, petitioners, parents of Negro

school children, brought suit in the U. S. District Court for

the Northern District of Georgia, seeking desegregation of

Atlanta’s public school system. The Court found that a

biracial school system existed; therefore, the Court ordered

respondents to submit a plan for desegregation by Decem

ber 1, 1959, which they did. The plan was approved by the

District Court on January 20, 1960. 188 F. Supp. 401, 412.

The plan called for the imposition of a racial transfer

procedure upon the existing biracial school structure (E.

61-63). Individual transfer applications were to be judged

by the Board on the basis of 17 pupil assignment criteria

(E. 33-34). The plan was to commence in the 12th and 11th

grades in September, 1961 and was to proceed on a grade-a-

year basis, in descending order, thereafter (E. 47). All

those students in grades below those in which the plan

operated were to remain segregated.

Between May 1st and 15th, 1961, pursuant to the plan,

129 Negro students in grades 11 and 12 returned applica

tion forms for transfer to white high schools (E. 65).

Of these, school authorities admitted 10 to four formerly

all-white high schools (E. 68).

The pupil assignment criteria were applied only to those

applicants, all Negroes, seeking transfer during the May

lst-15th period to schools attended by pupils of the op

posite race. All other applications for transfer, whites

to white schools and Negroes to Negro schools, were con

sidered “ informal” transfers and were made throughout the

school year (E. 94-96).

On April 30, 1962, after the plan’s first year of operation

petitioners moved the district court for further relief (E.

4

53). They claimed that the plan, which had been approved

over their numerous objections, had not resulted in de

segregation (R. 56-57). They prayed for not only a new

plan to speed up desegregation, but for one providing

prompt reassignment and initial assignment of all students

on some reasonable non-racial basis, e.g., the drawing of

a single set of attendance area lines for all schools without

regard to race or color to replace the dual scheme of school

attendance area lines for Negro and white schools. Peti

tioners further claimed that the Brown case contemplated

the reassignment of teachers on a non-racial basis and the

elimination of all other racial distinctions in the operation

of the school system (R. 56). In short, the petitioners

sought integration of the dual school system into a unitary

non-racial system, and with greater speed.

In September, 1962, 44 out of 266 Negro applicants were

admitted to grades 10, 11 and 12 (R. 94). On November

15, 1962, petitioners’ motion for further relief was denied

(R. 156). 217 F. Supp. 014. The District Court (Hooper,

District Judge) held (R. 157):

There is no disputing that discrimination had existed

prior to the Order of this Court of January 20, 1960,

and that the Order of that date was designed to elimi

nate the discrimination over a period of years. Even

plaintiffs’ counsel upon the original trial disclaimed

any purpose of seeking to have “wholesale integration.”

The only question then involved was the plan by which

discrimination could be eliminated; a Plan was care

fully prepared and adopted and no appeal taken. The

Plan is eliminating segregation, but until it has com

pleted its course there will of course still be areas

(in the lower grades) where segregation exists. The

Court is therefore at a loss to see how anything could

be accomplished at this time by “ an order enjoining

5

defendants from continuing to maintain and operate

a segregated biraeial school system”, for the Court has

already taken care of that in its decree of January

20, 1960.

Petitioners appealed to the Court of Appeals for the Fifth

Circuit which (2-1),1 on June 17, 1963, affirmed.

The Court, per Griffin B. Bell, Circuit Judge, recognized

that the “ bare bones” (R. 239) of the case was petitioners’

prayer for desegregation through the drawing of school

zone lines for each school on a non-racial basis and the as

signment of all children living in the zone to the school

without regard to race or color. Judge Bell denied peti

tioners’ prayer, saying (R. 240), “ the Atlanta plan of

abolishment is one of gradualism by permitting transfers

from present assignments.” Judge Bell found no incon

sistency between his decision and the decisions of this

Court in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, 347 U. 8.

483; Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, 349 U. S.

294; Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1; Watson v. City of

Memphis, 373 U. S. 526; Goss v. Board of Education of the,

City of Knoxville, 373 U. S. 683; or the decisions of his

own circuit, Bush v. Orleans Parish School Board, 308 F.

2d 491 (5th Cir. 1962); Augustus v. Board of Public In

struction, 306 F. 2d 862 (5th Cir. 1962); or the decisions

of the Fourth Circuit, Jones v. School Board of the City of

Alexandria, 278 F. 2d 72 (4th Cir. 1960); or the decisions of

the Sixth Circuit, Northcross v. Board of Education of the

City of Memphis, 302 F. 2d 818 (6th Cir. 1962). Judge Bell

concluded (R. 242-243) that “ the dual system will be en

tirely eliminated when the plan reaches the first grade. . . .

So considered, we hold that there is insufficient evidence

on which to base a determination that the start made in the

1 The Court consisted of Judges Bell and Rives and David T.

Lewis of the 10th Circuit, sitting by designation.

6

Atlanta schools is not reasonable, or that the plan is not

proceeding toward the goal at deliberate speed.”

Circuit Judge Bichard T. Kives, in his dissent, found an

inconsistency between the majority opinion and the prior

applicable decisions of this Court, He also demonstrated

that the opinion of the court was “ a backward step” (B.

246) for the Fifth Circuit, which had previously required

New Orleans, Louisiana and Pensacola, Florida to do far

more toward insuring full compliance with this Court’s

school desegregation decisions, Bush v. Orleans Parish

School Board, supra, Augustus v. Board of Public Instruc

tion, supra. He concluded that until a start was made in

abolishing the dual system of schools, whereby all white

children went initially to white schools and all Negro

children initially to Negro schools, no plan of selective

transfer from formerly Negro to formerly white schools

would fully satisfy the requirements of the Brown decision.

Moreover, Judge Kives concluded that the Atlanta Plan

does not now meet the requirements of deliberate speed.

In this regard he declared (B. 253) :

Enjoined as we are to give fresh consideration to the

element of timing in these school cases by the Su

preme Court’s latest pronouncement on the subject in

[Watson v. City of Memphis, 373 U. S. 526] and, fol

lowing the Watson decision, in Josephine Goss et al. v.

Board of Education, City of Knoxville, Tenn., et al.,

[373 IT. S. 683], I cannot concur in a decision of this

Court that takes a backward rather than a current,

much less forward, step.

Behearing was denied (2-1) on August 16, 1963 (B. 258-

259).

Petitioners filed a petition for writ of certiorari on No

vember 14, 1963, which was granted on January 13, 1964

(B. 260).

7

A R G U M E N T

The Plan Erroneously Approved Below Does Not Con

form to the Mandate of This Court; the Plan Desegre

gates Too Little, Too Late.

1. The Transfer Plan Is Not an Effective Vehicle

for Desegregation Because It Preserves the

Biracial School Structure.

The end result of Atlanta’s plan has been that in At

lanta’s public schools, a decade after the first Brown deci

sion, 145 out of a total of 56,000 Negro students have been

permitted to attend school with 58,000 white students.2 In

short, tokenism has been now superimposed upon so called

separate but equal.3 * * Petitioners submit that tokenism does

not satisfy the Fourteenth Amendment mandate of equal

protection of the laws.

Prior to September, 1961, Atlanta had a dual school sys

tem (R. 157). There was one system of schools for white

pupils and a separate system of schools for Negro pupils.

In September, 1961, a plan purporting to cure this con

stitutional infirmity was instituted. The adequacy of this

plan must now be examined by this Court in the light of

this Court’s decisions.

2 Southern Education Reporting Service, Statistical Summary of

School Segregation-Desegregation in the Southern and Border

States (1963-1964), p. 17.

3 Separate and «wequal would be a more accurate characteriza

tion, for the school facilities for Negroes are in fact unequal to

those for whites. Negroes constitute 49% of the school population,

but they have been allotted only 33% of the school buildings and

40% of the teachers and principals; as a result, they suffer serious

overcrowding in certain schools and have higher pupil-teacher

ratios (R. 101).

8

Petitioners start with the incontrovertible proposition

that segregation in Atlanta’s schools exists unimpaired ex

cept as modified by the racial transfer plan.4

The plan provides for transfers on an individual basis

for those students who satisfy 17 pupil placement criteria

(R. 33-34).5 Respondents judge the individual applications

of Negroes, reject most,6 and permit a nominal number to

transfer. In practice, the structure of segregation remains

unaltered—with a new facade.

In theory, as well, the plan is devoted to the promotion

of token desegregation. The theory is to place the burden

of leveling the structure on each individual school child.

The child must procure a transfer application, prepare and

submit it. If rejected for any of a number of vague rea

sons, the child must protest to the Board and then apply

to the court for relief (R. 233). In court, the child must

show a discriminatory application of the plan. It is pain

fully apparent that the plan calls for a war of attrition,

in which only the hardiest will be able to bear the burden

of a contest with state power. Moreover, the theory not

only depends upon enmeshing each child in an administra

tive net, but depends as well upon clothing respondents—

admitted wrongdoers—with practically unreviewable dis

cretion over the quality and extent of their own reforma

tion. The theory of the plan is to allow respondents to

place a high price tag on the exercise of the constitutional

4 R. 61-63; Majority opinion, Footnote 4 (R. 240) ; dissenting

opinion, Footnotes 4, 5 (R. 250-251).

5 The 17 criteria are identical with those of the Alabama Pupil

Assignment Law upheld as constitutional on its face in Shuttles-

worth v. Birmingham Board of Education, 358 U. S. 101, affirming

162 F. Supp. 372 (N. D. Ala. 1958). Here, of course, the case

involves the application of such a plan, not its surface plausibility.

6 119 out of 129 applicants were rejected in 1961 (R. 68); 222

out of 266 applicants were rejected in 1962 (R. 94).

9

right to attend desegregated public school facilities; the

theory is to recognize a paper, not a present, right. The

theory works and the result is, not unexpectedly, a system

of token desegregation.

This Court did not hold in Brown v. Board of Educa

tion that the vice of total segregation could be cured

by the device of token desegregation. This Court decreed

the abolition of the biracial school system. That system

retains its pristine strength today in Atlanta’s grades 1-8;

in grades 9-12, the essential structure of the biracial school

system perdures.

This Court’s decisions interdict the tokenism counte

nanced by the Atlanta plan. Brown II is perfectly explicit

in its command that a prompt and reasonable start be made

“ to achieve a system of determining admission to the public

schools on a nonracial basis” (349 U. S. at 300-301). What

Brown requires is elimination, not modified retention, of

the biracial school structure. In this context, what was said

in Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1, 17, is significant:

In short, the constitutional rights of children not to

be discriminated against in school admission on

grounds of race or color declared by this Court in the

Brown case can neither be nullified openly and directly

by state legislators or state executive or judicial offi

cers or nullified indirectly by them through an evasive

scheme for segregation whether attempted “ ingen

iously or ingenuously.” Smith v. Texas, 311 U. S. 128,

132, 85 L. Ed. 84, 87, 61 S. Ct. 164.

The decision below also conflicts sharply with decisions

in the Fifth Circuit and in the Fourth and Sixth Circuits.

Judge Rives, in dissent below, correctly noted that the

instant decision is an unwarranted retreat from the posi

tion taken in Augustus v. Board of Public Instruction, 306

10

F. 2d 862 (5th Cir. 1962) and Bush v. Orleans Parish School

Board, 308 F. 2d 491 (5th Cir. 1962).

Both decisions unquestionably stand for the proposition

that it is the dual school system itself which must be abol

ished and that the window dressing of a transfer plan is not

a permissible substitute for the outright abolition of the

system.

In Bush, as here, the Court of Appeals was presented

with a pupil placement system which purported to be a

vehicle for school desegregation. In Bush, the court rightly

exposed the system as a sham. The Court said:

This Court, like both Judge Wright7 and Judge Ellis,8

condemns the Pupil Placement Act, when, with a fan

fare of trumpets, it is hailed as the instrument for

carrying out a desegregation plan, while all the time

the entire public knows that in fact it is being used to

maintain segregation by allowing a little token de

segregation. . . . The Act is not an adequate transi

tionary substitute in keeping with the gradualism im

plicit in the “ deliberate speed” concept. It is not a

plan for desegregation at all. 30S F. 2d at 499-500.

7 The Court set forth and approved Judge W right’s statement:

To assign children to a segregated school system and then

require them to pass muster under a pupil placement law is

discrimination in its rawest form. 308 F. 2d at 498.

8 The Court set forth and approved Judge Ellis’ statement:

. . . It goes without saying that although “ [the] school

placement law furnishes the legal machinery for an orderly

administration of the public schools in a constitutional man

ner,” . . . “ [the] obligation to disestablish imposed segrega

tion is not met by applying placement assignment standards,

educational theories or other criteria so as to produce the

result of leaving the previous racial situation existing as it

was before” . . . It does no good to say that the pupil placement

law is applied solely to transferees without regard to race

when the procedure is so devised that the transferees are

always Negroes. 308 F. 2d at 498.

11

Augustus is in accord. There it was said: “ There cannot

be full compliance with the Supreme Court’s requirements

to desegregate until all dual school districts based on race

are eliminated” (306 F. 2d at 869).

Pupil placement plans superimposed upon biracial school

structures have been similarly discarded in the Fourth9 and

Sixth10 Circuits.

In Northeross, as here, the pupil assignment system con

tinued. to assign Negroes to Negro schools and whites to

white schools, except as modified by the transfer plan. The

9 Jones v. School Board of the City of Alexandria, 278 F. 2d

72, 76 (4th Cir. 1960); Green v. School Board of the City of

Roanoke, 304 F. 2d 118 (4th Cir. 1962).

It is possible that pupil placement plans or laws as a vehicle

for school desegregation have some vestigial vitality in the Fourth

Circuit, but their effectiveness for this purpose has been attenu

ated by the requirement that transfers be freely given. Jeffers v.

Whitley, 309 F. 2d 621 (4th Cir. 1962). The question in Jeffers

was whether a system of racial assignments could cure the con

stitutional infirmity of a biracial school system. The Court found

that this could not be so if the system were not completely vol

untary. The Court said:

[ I ] f a voluntary system is to justify its name, it must, at

reasonable intervals, offer to the pupils reasonable alternatives,

so that, generally, those who wish to do so may attend a

school with members of the other race. 309 F. 2d at 627.

In other words, transfers must be “had for the asking” (309

F. 2d at 628). The Jeffers solution still left the administrative

burden on the individual school child to apply to the School Board

for that to which he was entitled as of right. However, the Court

threw doubt on this vestige of the pupil placement law by saying:

There can be no freedom of choice if its [the transfer re

quest’s] exercise is conditioned upon exhaustion of adminis

trative remedies which, as administered, are unnegotiable

obstacle courses. 309 F. 2d at 628.

Pending before the Fourth Circuit is the issue of whether the

administrative burden may continue to be placed on each indi

vidual school child to level the biracial school structure. See

Farmer v. Greene County Board of Education, 4th Cir., No. 9125,

now being reconsidered en hone.

10 Northcross v. Board of Education of the City of Memphis, 302

F. 2d 818 (6th Cir. 1962).

12

School Board argued that the transfer provisions created

a voluntary system and that therefore, there was no com

pulsory segregation of the races. The Court of Appeals

dismissed this and similar contentions saying (302 F. 2d

at 823):

Minimal requirements for non-racial schools are geo

graphic zoning according to the capacity and facilities

of the buildings and admission to a school according to

residence as a matter of right. “ Obviously the main

tenance of a dual system of attendance areas based on

race offends the constitutional rights of the plaintiffs

and others similarly situated and cannot be tolerated.”

Jones v. School Board of City of Alexandria, Virginia,

278 F. 2d 72, 76, C. A. 4.

That Court concluded (302 F. 2d at 823):

Negro children cannot be required to apply for that

to which they are entitled as a matter of right.

The reasons assigned for holding the transfer provisions

an insufficient vehicle for reorganizing the schools on a non-

racial basis were essentially practical. The reasons stemmed

from an appreciation of the hard fact that shifting the ad

ministrative burden of desegregation to each individual

school child ineluctably results in token desegregation.

The Court found (302 F. 2d at 823):

Any pupil through both parents may request a trans

fer, but in the final analysis it is up to the School

Board to grant or reject it. Although an appeal may

be taken into the courts it would be an expensive and

long drawn out procedure with little freedom of action

on the part of the courts. In determining requests for

transfers the Board may apply the criteria heretofore

13

mentioned. None of these criteria is based on race, but

in the application of them, one or more could always

be found which could be applied to a Negro. The denial

of the transfers herein referred to is significant of the

practical application of the transfer provisions of the

law.

In short, Northcross persuasively demonstrates that the

responsibility for initiating and effectuating desegregation

rests upon the school authorities and that these authorities

cannot shift their responsibilities to others. Especially is

that true when that shifting of responsibility operates to

inhibit desegregation.

The short of petitioner’s submission is that the Atlanta

plan is ineffective to transform the biracial system into a

unitary nonracial system in accordance with the decisions

of this Court. The remedy is not to strike at the branches

of the evil, but at its root. In this case, the root of the

evil is the biracial school structure itself. That structure

must be removed in favor of some reasonable nonracial

system of pupil assignment.

2. The Delay Countenanced by the Plan Is Unwarranted.

Not only must a unitary system be established, but it

must come with greater celerity than 12 years. Petitioner’s

plan for moderate acceleration to 6 years (1960-1965) (R.

82-83) should have been approved by the court below. If

this had been done, desegregation would today be on the

verge of completion.

Petitioners submit that this Court’s recent admonition

in Watson v. City of Memphis, 373 U. S. 526, not only au

thorized but compelled such acceleration. Mr. Justice

Goldberg speaking for the Court in Watson said:

14

[T]lie second Brown decision, 349 U. S. 294, 75 S. Ct.

753, which contemplated the possible need of some

limited delay in effecting total desegregation of public

schools, must be considered . . . in light of the signifi

cant fact that the governing constitutional principles

no longer bear the imprint of newly enunciated doc

trine. . . . [W ]e cannot ignore the passage of a sub

stantial period of time since the original declaration

of the manifest unconstitutionality of racial practices

such as are here challenged, the repeated and numerous

decisions giving notice of such illegality, and the many

intervening opportunities heretofore available to at

tain the equality of treatment which the Fourteenth

Amendment commands the States to achieve. These

factors must inevitably and substantially temper the

present import of such broad policy considerations as

may have underlain, even in part, the form of decree

ultimately framed in the Brown case. Given the ex

tended time which has elapsed, it is far from clear

that the mandate of the second Brown decision re

quiring that desegregation proceed with “ all deliberate

speed” would today be fully satisfied by types of plans

or programs for desegregation of public educational

facilities which eight years ago might have been deemed

sufficient. Brown never contemplated that the concept

of “ deliberate speed” would countenance indefinite de

lay in elimination of racial barriers in schools . . .

373 U. S. at 529-30.

That standards for desegregation plans adequate in 1955

are no longer adequate—-and that it is time for a second look

| at the rate of desegregatioiF1̂ ^ 'm by Mr. Jus

tice Clark in Goss v. Board of Education of the City of

Knoxville, 373 U. S. 683, 689:

15

Now however, eight years after this decree [Brown II]

was rendered, and over nine years after the first

Brown decision, the context in which we must interpret

and apply this language to plans for desegregation

has been significantly altered.

The Courts of Appeals have also shown great impatience

with the all-too-deliberate-sloth of the 12-year plans. Four

circuits—the Third,11 Fourth,12 Fifth13 and Sixth14—have

now invalidated “ grade-a-year” plans.

'These decisions make perfectly plain that, the burden was

on respondents here to show that the delay attendant upon

the “ grade-a-year” feature of the plan was imperatively

and compellingly unavoidable. No such showing was made.

Moreover, these decisions dictate that respondents should

not now be treated as those school boards which made a

prompt and reasonable start in 1955.

3. A Prompt and Reasonable Start Should Be Made

Toward Desegregation of the School Personnel.

Another major prop of the segregated school system

which the majority opinion leaves standing is the segre

gated staff. As all the world knows, in Atlanta, as else

where, school segregation not only consists of having a

Negro child in every seat in a Negro school but in having

a Negro teacher in front of every Negro class. Moreover,

11 Evans v. Ennis, 281 F. 2d 385 (3d Cir. 1960).

12 Jackson v. School Board of The City of Lynchburg, 321 F. 2d

230 (4th Cir. 1963).

13 Bush v. Orleans Parish School Board, 308 F. 2d 491, 500,

501-502 (5th Cir. 1962).

14 Ooss v. Board of Education of the City of Knoxville, 301 F. 2d

164 (6th Cir. 1962), reversed on other grounds, 373 U. S. 683.

16

Atlanta goes so far as to put all Negro schools under the

direction of a Negro supervisor (E. 72).

The District Court, in this case, indefinitely postponed

consideration of the assignment of Negro teachers on a

nonracial basis. Such deferment is per se contrary to this

Court’s admonitions in Watson and Goss that the time has

come for full compliance with this Court’s directive to put

an end to jerry-built devices for preserving segregation.

And recently the Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit

decreed that the practice of assigning teachers by race falls

within the Brown proscription against the continuation of

racial distinctions in the public school system. Board of

Public Instruction of Duval County v. Braxton, 5th Cir., No.

20294, January 10, 1964.

4 . Unreversed, the Majority Opinion Dictates That

Soon Another Generation of Negro Students Will

Graduate From Atlanta’s Public School System

With the Promise of Equality Made in 1954

Unredeemed.

The majority opinion’s approval of Atlanta’s policy of

tokenism and delay cannot be squared with the proposition

that the constitutional right to attend a desegregated pub

lic school system is a present right. This court recently said

in Watson :

[T]he delay countenanced by Brown was a necessary

albeit significant adaptation of the usual principle that

any deprivation of constitutional rights calls for

prompt rectification. The rights here asserted are, like

all such rights, present rights; they are not merely

hopes to some future enjoyment of some formalistic

constitutional promise. The basic guarantees of our

Constitution are warrants for the here and now, and,

unless there is an overwhelmingly compelling reason,

they are to be promptly fulfilled. 373 IT. S. at 532-33.

17

The result of the majority opinion is not only inconsistent

with the great promise of equality envisioned by this

Court’s 1954 decision, but it also jeopardizes the forward

progress made to date. Three other major school districts

—Savannah, Georgia, Birmingham, Alabama, and Mobile

County, Alabama—ordered to commence desegregation in

September, 1962, by the Fifth Circuit, pending appeal, im

mediately adopted the Atlanta plan which had just been

approved. As a result, Savannah admitted 21 Negro stu

dents to the 12th grade out of a school population of 24,013

whites and 15,336 Negroes. Birmingham admitted 5 to the

12th grade out of a school population of 37,500 whites and

34,834 Negroes. Mobile County admitted 2 to the 12th grade

out of a school population of 47,247 whites and 30,020

Negroes.

ITnreversed, the majority opinion supports the proposi

tion that token desegregation conforms to the mandate of

equal protection of the laws. This erroneous and mischie

vous doctrine requires prompt expunetion by this Court.15

15 See Bickel, The Decade of School Desegregation, 64 Columbia

Law Review 193 (1964), particularly pp. 208-211.

18

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, it is respectfully submitted

that the judgment below should be reversed.

Respectfully submitted,

C onstance B aker M otley

J ack Greenberg

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

E. E. M oore

Suite 201

175 Auburn Avenue, N. E.

Atlanta, Georgia

D onald L . H ollowell

Cannolene Building (Annex)

859!/2 Hunter Street, N. W.

Atlanta, Georgia

Attorneys for Petitioners

N orman A m aker

A. T. W alden

J. L eV onne C hambers

Of Counsel

ojiigĝ . S 8