Lampkin v. Connor Opinion

Public Court Documents

April 14, 1966

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Lampkin v. Connor Opinion, 1966. 98c54842-ba9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/7dad48a6-117a-4877-8d0d-e097170c3537/lampkin-v-connor-opinion. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

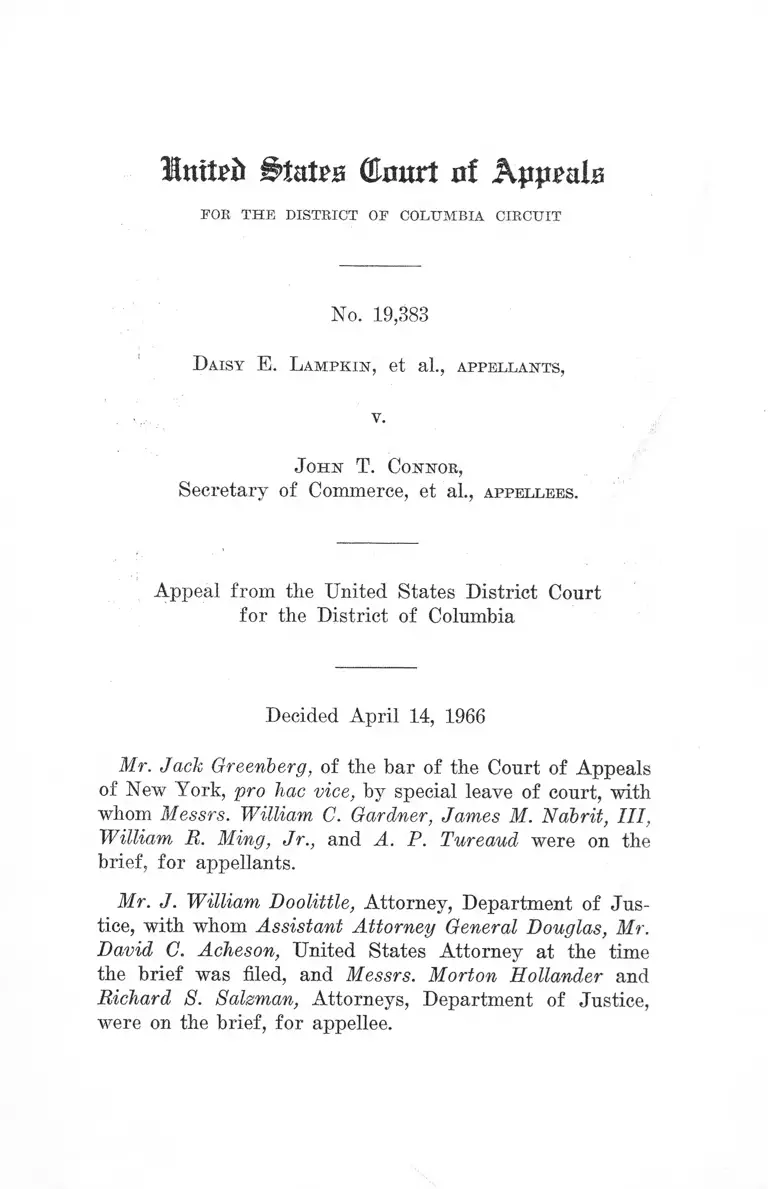

Imted States (£mxt of Appeals

FOE THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA CIRCUIT

No. 19,383

D aisy E. Lampkin, et al., appellants,

v.

J ohn T. Connor,

Secretary of Commerce, et al., appellees.

Appeal from tlie United States District Court

for the District of Columbia

Decided April 14, 1966

Mr. Jack Greenberg, of the bar of the Court of Appeals

of New York, pro Jiac vice, by special leave of court, with

whom Messrs. William C. Gardner, James M. Nabrit, III.

William R. Ming, Jr., and A. P. Tureaud were on the

brief, for appellants.

Mr. J. William Doolittle, Attorney, Department of Jus

tice, with whom Assistant Attorney General Douglas, Mr.

David G. Acheson, United States Attorney at the time

the brief was filed, and Messrs. Morton Hollander and

Richard 8. Salsman, Attorneys, Department of Justice,

were on the brief, for appellee.

2

Before Edgerton, Senior Circuit Judge, and F ahy and

M cG o w a n , Circuit Judges.

McGowan, Circuit Judge: This is an appeal from the

dismissal of a complaint under the Declaratory Judgment

Act. 28 U.S.C. §§ 2201-02. Appellants sought in the Dis

trict Court a determination that appellees, in their official

capacities as Secretary of Commerce and Director of the

Census, are required to implement the provisions of Sec

tion 2 of the Fourteenth Amendment,1 which contemplates

a reduction in the basis of a state’s representation in

Congress when that state denies or abridges the right to

vote. For the reasons appearing hereinafter, we do not

reinstate the complaint.

I

Appellants, who brought this action on behalf of them

selves and others similarly situated, Rule 23 (a) (3) F ed.

R. Civ. P., comprise two groups by their own designation.

The so-called Group I appellants are registered voters

from Pennsylvania, Massachusetts, Missouri, Illinois,

Ohio, and California. They assert that, if apportionment

were to be effected in accordance -with the literal com

1 “Representatives shall be apportioned among the several

states according to their respective numbers, counting the

whole number of persons in each State, excluding Indians

not taxed. But when the right to vote at any election for

the choice of electors for President and Vice President of

the United States, Representatives in Congress, the Execu

tive and Judicial officers of a State, or the members of the

Legislature thereof, is denied to any of the male inhabitants

of such State, being twenty-one years of age, and citizens

of the United States, or in any way abridged, except for

participation in rebellion, or other crime, the basis of repre

sentation therein shall be reduced in the proportion which

the number of such male citizens shall bear to the whole

number of male citizens twenty-one years of age in such State.”

3

mands of Section 2, the alleged denials and abridgements

of the right to vote by certain other states would compel

a reduction in the representation of those latter states,

and a corresponding increase in the representation of

their own. Since appellees do not presently provide the

necessary statistical basis for such reapportionment, the

Group I appellants claim that (1) their congressmen rep

resent more persons than the congressmen from states

which deny or abridge the right to vote, (2) the value of

their votes is consequently diluted in violation of their con

stitutional rights, and (3) enforcement of Section 2 is

necessary in order to protect their votes from such dilution.

The remaining appellants classify themselves as Group

II. They are citizens of Virginia, Mississippi, and Loui

siana, claiming to be qualified voters in all respects except

that various discriminatory practices, including literacy

tests and poll tax requirements, deprive them of their

right to vote. They invoke Section 2 in order to deter

the deprivations which they are allegedly suffering.

All appellants point out that, under the relevant statutes,2 * * * 6

appellees are presently charged with the responsibility

for compiling a tabulation of the population for the pur

poses of representation, preparing a statement showing

2 2 U.S.C. §§ 2(a), 6; 13 U.S.C. §§ 4, 5, 11, 21, 141. 2

U.S.C. § 2(a) provides that the President shall transmit an

apportionment statement to Congress showing the number of

representatives to which each state is entitled. 2 U.S.C. §

6 declares that the number of representatives apportioned

shall be reduced in accordance with Section 2 of the Four

teenth Amendment. 13 U.S.C. §§ 4, 5, and 141 variously

authorize the Secretary of Commerce to take the census, to

tabulate “ total population by States as required for the

apportionment of Representatives . . to report to the

President, and to delegate his functions. 13 U.S.C. § 11

authorizes the appropriations needed to carry out these pro

visions, and 13 U.S.C. § 21 provides for the appointment

of a Director of the Census.

4

the representation to which each state is entitled, and

submitting that statement to the President for transmittal

to Congress.3 They contend that these laws, properly con

strued, also require appellees, contrary to their present

practice, to take into account whatever reduction in rep

resentation may be required by Section 2 of the Four

teenth Amendment; and that, if these statutes be viewed

as not embodying this requirement, they must be declared

void and of no effect as unconstitutional. The complaint

prays for a declaration that appellees are now required

(1) to take steps to compile statistics in the 1970 census

on the denial and abridgement of the right to vote, and

(2) thereafter to prepare an apportionment statement

based upon such statistics for submission to the President

and ultimate transmittal to Congress. In the event such

a reading of the statutes is not made, the complaint asks

that the existing statutes relating to the administration

of the census and the preparation of the apportionment

statement be invalidated.

Appellees filed a timely motion to dismiss or, in the

alternative, for summary judgment. This motion asserted

that appellants lacked standing to sue, a justiciable con

troversy was absent, and the complaint failed to state a

cause of action for which equitable relief is available.

Attached to the motion was an affidavit of the then Direc

tor of the Census to the effect that the compilation of

the statistics demanded by appellants was not feasible.

In opposing the motion, appellants submitted a counter

affidavit contradicting the Director’s assertions in this

regard.

The District Court, being of the view that, under 3

3 Appellants assert that “while it is the President who

transmits the figures to Congress, he is merely a conduit

for the statement prepared, compiled and computed by the

Secretary and Bureau of the Census.”

5

Frothingham v. Mellon, 262 U.S. 447 (1923), both groups

of appellants lacked standing to sue, granted the motion

to dismiss. As to the Group I appellants, the court re

garded as sheer speculation their allegations that increased

representation of their states was a likely consequence

of the relief sought. In any event, the claimed dilution

of the value of their vote was viewed bĵ the court as

shared with millions of other voters in other states where

the. right to vote is neither abridged nor denied. The

Group II appellants were thought to be in no better

position. The possibility that the relief requested would

serve as a meaningful deterrent to the alleged denials

and abridgements of voting rights was, to the court, too

remote and speculative to found judicial intervention.

Although the order appealed from is limited to a grant

of the motion to dismiss, the District Court volunteered

the further opinion that, even if appellants had standing,

summary judgment in favor of appellees would be appro

priate. It did not regard appellees as under a statutory

dutj ̂ to compile the statistics and submit the apportion

ment statement demanded; 4 nor did it regard the omission

of any such duty as rendering the legislation unconstitu

tional. United States v. Sharrow, 309 F.2d 77 (2d Cir.

1962), cert, denied, 372 U.S. 949 (1963), was cited by the

court to support its view that the census machinery was

not the constitutionally requisite channel for carrying out

the purposes of Section 2 of the Fourteenth Amendment.

4 Reliance was placed upon (1) the language of 2 U.S.C.

§ 2(a) which requires the President to transmit to Congress

an apportionment statement showing “the whole number

of persons in each state, excluding Indians not taxed . . . .”

(emphasis added) ; (2) the failure to effect amendments to

the Census and Reapportionment Act which would have re

quired the compilation of statistics to enforce Section 2; and

(3) various legislative and judicial statements that Section

2 has never yet been implemented by Congress.

6

Immediately in issue on this appeal is appellants’ con

tention that the District Court erred in dismissing their

complaint, either for lack of standing or non-justiciability.

We sherry v. Sanders, 376 U.S. 1 (1964), and other reappor

tionment cases are said to establish beyond any doubt

the standing of the Group I appellants to protect the

full weight of their right to vote.5 And the Group II

appellants have standing, so it is said, because Section 2

of the Fourteenth Amendment was directed at protecting

the very rights of an individual and personal nature

which these particular appellants are asserting. If, we

are told, these latter appellants do not have standing to

invoke, Section 2, then it is unlikely that any one does.

Contrary to the view of the court below, appellants insist

that the threat of breathing life into Section 2 would be

of great practical utility in securing greater recognition

of their rights to vote. The doctrine of standing does not,

in this submission, require a shoving of absolute cer

tainty of success.

In response, appellees argue that standing is lacking

because the recent civil rights legislation either has

removed or is fast removing the barriers to voting of

which appellants complain. By the 1970 census it is

likely, they contend, that these barriers will be eliminated.

Alternatively, they argue that dismissal was proper, even

if standing existed, because a non-justiciable question is

involved, since apportionment is a duty which has been

constitutionally entrusted to Congress, with an unreview-

able discretion as to how it is to be accomplished. In

enacting the recent civil rights legislation, culminating

II

5 Cases allowing taxpayers to challenge the apportionment

of taxes among the states are also cited to support appel

lants’ contention that voters have standing to challenge the

apportionment of representatives.

7

in the Voting Rights Act of 1965, Congress has selected

its own method of insuring the right of all citizens to vote.

Whatever Baker v. Carr, 369 U.S. 186 (1962), did to limit

the political question doctrine with respect to the intru

sion of the federal judiciary into matters of state gov

ernment, it is claimed to have no relevance to cases

involving the relationship of co-equal branches of the fed

eral government. In any event, the determination of

whether, within the meaning of Section 2, an individual

has been wrongfully denied his right to vote is said to

involve a standard which it would not be feasible for

either the courts or the executive department to try to

apply.

In disposing of this appeal, however, we need not—and

do not—proceed solely by reference to the pi'ecise grounds

pressed upon us by the parties. Our point of departure

is that this is an action brought under the Declaratory

Judgment Act. As we have said on another occasion, in

accord with numerous declarations by this court6 as well

as the Supreme Court,7 “ [T]he courts have a broad

6 Davis V. Board of Parole, 113 U.S.App.D.C. 194, 306

F.2d 801 (1962) (discretion to decline jurisdiction when

another jurisdiction is more appropriate) ; Gordon V.

Mattheivs, 106 U.S.App.D.C. 400, 273 F.2d 525 (1959) (simi

lar) ; Heyward V. Public Housing Administration, 94 U.S.App.

D.C. 5, 214 F.2d 222 (1954) (discretion to decline jurisdic

tion when a party, although not an indispensable party, was

not before the court) ; Williams V. Virginia Military Insti

tute, 91 U.S.App.D.C. 206, 198 F.2d 980 (1952), cert, denied,

345 U.S. 904 (1953) (discretion to decline jurisdiction when

jurisdiction is doubtful and another forum exists where

jurisdiction is proper and which is better suited to decide

the question) ; Washington Terminal Co. V. Boswell, 75 U.S.

App.D.C. 1, 124 F.2d 235 (1941), aff’d, 319 U.S. 732 (1942)

(discretion to decline jurisdiction when the statutory scheme

provides special review procedures).

7 Zemel v. Rusk, 381 U.S. 1, 19 (1965); Public Affairs

8

measure of discretion to decline to issue declaratory judg

ments . . Marcello v. Kennedy, 114 U.S.App.D.C. 147,

312 F.2d 874 (1962), cert, denied, 373 U.S. 933 (1963).

The language of the Act is permissive: “ [A]ny court of

the United States . . . may declare the rights and other

legal relations of any interested party seeking such dec

laration . . . ” (emphasis added). These provisions have

been regarded as “ an enabling Act, which confers a dis

cretion on the courts rather than an absolute right upon

the litigant.” Public Service Comm’n. v. Wycoff Co., 344

U.S. 237, 241 (1952). Thus it is appropriate, in the context

o f a declaratory judgment suit, to weigh a wider range

of considerations than would be either necessary or appro

priate if the only issue were one of standing.8

This discretion is not unbounded, and the admonition

in Wesberry v. Sanders that dismissal for want of equity

cannot mask what is in effect an improper dismissal for

“political question” reasons must be observed. 376 U.S. 1,

4, 7 (1964). But some circumstances have been recognized

as appropriate for declining to exercise jurisdiction under

the Declaratory Judgment Act, and the factors there rele

vant are present here as well. In matters of public law,

courts should be careful to avoid “ futile or premature

interventions” that would reach far beyond the particular

case; and “ the disagreement must not be nebulous or

contingent but must have taken on fixed and final shape ... .”

Public Service Comm’n, v. Wycoff Co., supra at 244-45.9

Associates, Inc. V. Rickover, 369 U.S. I l l (1962) ; A. L. Mech-

ling Barge Lines, Inc. V. United States, 368 U.S. 324 (1961) ;

Great Lakes Dredge & Dock Co. V. Huffman, 319 U.S. 293

(1943) ; Brillhart V. Excess Ins. Co., 316 U.S. 491 (1942) ;

Aetna Life Ins. Co. V. Haworth, 300 U.S. 227 (1937).

8 See Public Service Comm’n. V. Wycoff Co., supra; Eccles

v. Peoples Bank, 333 U.S. 426 (1948).

9 In Public Service Comm’n the Supreme Court reversed

9

When the possibility of the injury’s occurring is remote

and uncertain, a declaratory judgment is inappropriate.

See Eccles v. Peoples Bank, supra at 431,10 where it

is said that “ [E]specially where governmental action

is involved, courts should not intervene unless the need

for equitable relief is clear, not remote or speculative.”

So it is that we must be concerned with the timing of

the present action. The problem is not so much one of

whether, as in some of the cases discussed hereinabove,

an injury not yet incurred is likely ever to happen. We

a determination that respondent’s carriage of motion picture

films between points in Utah constituted interstate com

merce. That conclusion was sought by respondent in order

to prevent the Public Service Commission of Utah from

regulating its activities. As viewed by the Court, the record

did not reveal any attempt by the Commission “to enter

any specific order or take any concrete regulatory step;”

rather, it viewed respondent as seeking a declaratory judg

ment “ to guard against the possibility that said Commission

would attempt to prevent respondent from operating under

its certificate from the Interstate Commerce Commission.”

344 U.S. at 244 (emphasis in original). Thus, a proper

exercise of discretion required dismissing the case, because

the possibility and the nature of any adverse action against

respondent was too uncertain.

10 Eccles was an action for a declaratory judgment that

a condition imposed upon respondent’s membership in the

Federal Reserve System was invalid. The condition pro

vided that Transamerica, a bank holding company, could

not own any of respondent’s stock. The suit was instituted

because the condition was violated by the acquisition of a

small amount of stock by Transamerica. The Board of

Governors of the Federal Reserve System expressed an inten

tion not to invoke the condition, although it technically was

violated, because the acquisition did not affect the control

of respondent. Because of this assurance, respondent’s

grievances were regarded as “ too remote and insubstantial,

too speculative in nature,” to be appropriate for judicial

correction.

10

are under no illusions as to what has been going on in

the states of residence of the Group II appellants. The

remote and speculative character of the relief sought here

derives, rather, from the fact that it cannot, by its very

nature, become effective before several years have elapsed.

Meanwhile, and largely since this suit was first filed, Con

gress has moved directly and in a massive way to eliminate

the injuries which this complaint seeks to get at indirectly

by means of the 1970 census and the apportionment made

on the basis of it for the election of 1972. It is these

events which create a remoteness of their own, and bring

into play in this suit considerations of judicial economy

and reluctance to prescribe for, or to correct, a coordinate

branch of the national government in the discharge of its

constitutional responsibilities as it understands them.

The Group I appellants claim to be injured because the

value of their votes in allegedly non-discriminating states

is diluted by the discrimination of other states against

Negro voting. The continuation of this discrimination is

an essential predicate to the relief they request. I f these

practices cease, there is no dilution of their votes and,

consequently, no injury needing redress. Whether the

Group I appellants suffer any injury depends upon

whether the allegations made by the Group II appellants

concerning the denials and abridgements of the right to

vote by their states can be sustained.11

11 Appellants contend that the complaint may fairly be

construed as alleging an interest of the Group I appellants

which is independent of that asserted by the Group II appel

lants. But the allegations to which they refer, and the sta

tistics offered in support of them, relate to the extent of

the discrimination of which the Group II appellants com

plain with greater particularity. If, then, the specific prac

tices complained of by the Group II appellants do not give

rise to an injury which may be recognized at this time, the

injuries alleged by the Group I appellants must also be

viewed as prematurely asserted.

11

The Group II appellants claim to be injured because

of certain state-created obstacles to their exercise of the

franchise. More specifically, the Virginia appellants com

plain that they are unable to vote because Virginia law

requires the payment of a poll tax and the completion

of a registration form in the registrant’s handwriting.

The Mississippi appellants advance a similar disability

because of the constitutional interpretation test and poll

tax required by their state. And the appellant from

Louisiana asserts a like disability because of that state’s

requirement that voter registration forms must be com

pleted without error of any kind.

The Voting Rights Act of 1965, however, was directed

at eliminating voting discrimination for reasons of race

or color through the use of literacy tests and similar

devices. Under Section 4 of that Act, if the Attorney

General of the United States determines that such devices

were maintained by a state on November 1, 1964, and the

Director of the Census determines that less than fifty per

cent of the persons of voting age residing in that state

were registered for or voted in the presidential elections

of 1964, then use of such devices is to be suspended. The

requisite findings have been made by the Attorney General

and the Director of the Census as to Virginia, Mississippi,

and Louisiana; and the literacy tests of which appellants

complain have been suspended.

The Twenty-fourth Amendment, which became effec

tive in February of 1964, erases poll tax requirements

for federal elections. Although it does not reach the im

position of poll taxes in state elections, Section 10 of the

Voting Rights Act of 1965 recognizes that problem.12 That

12 On September 15, 1965, appellants moved for postpone

ment of oral argument until the Supreme Court could decide

the question of the rights of citizens to vote in state elec

tions without payment of a poll tax. Although appellees

12

Act includes a Congressional declaration “ that the con

stitutional right of citizens to vote is denied or abridged

in some areas by the requirement of the payment of a

poll tax as a precondition to voting.” It authorizes the

Attorney General to institute actions to set aside such

taxes, and suits have been brought, pursuant to these

provisions, to eliminate the poll tax requirements in the

states in question. Appellants suggested that a substantial

question exists as to the constitutionality of state poll

taxes, but the Supreme Court has recently, in Harper

v. Virginia State Board of Elections, 43 U.S. L aw W eek

4305, (March 22, 1966), removed that issue from the realm

of speculation. In that case, the Court declared a Virginia

poll tax of $1.50 repugnant to the equal protection clause,

and spoke in words which leave no doubt as to the uncon

stitutionality of poll taxes as a prerequisite to voting.

Congress has, thus, acted vigorously and comprehen

sively to remove the obstacles to voting of which the

appellants complain. To regard its measures as having

no effect upon the discriminations alleged by the Group

II appellants, and derivatively relied upon by the Group

I appellants, would not afford them the respect an Act

of Congress deserves. Congress has established a plan

of direct action for assuring to all citizens a non-dis-

criminatory right to vote, and steps have been taken to

implement these provisions. At this time we cannot assay

the final impact of these measures upon discrimination

against Negro voting; nor do any of the allegations in

the complaint assist in this task.13 It has been thought

consented to the motion, it was denied because of disagree

ment as to the effect of such decision on this case.

13 The complaint in this case was filed two years prior to

the enactment of the Voting Rights Act of 1965. As appel

lants admit, “ [A]t the time the complaint was drafted, pro

posal of the Act, much less its adoption, was unlikely.”

13

the better part of judicial wisdom to withhold declaratory

relief when “ it appears that a challenged ‘continuing prac

tice’ is, at the moment adjudication is sought, undergoing

significant modifications so that its ultimate form cannot

be confidently predicted.” A. L. Mechling Barge Lines,

Inc. v. United States, 368 U.S. 324, 331 (1961). In this

case, in light of the specific steps taken by Congress to

eliminate the Group II appellants’ causes for complaint,

our discretion is best exercised by declining to compel the

District Court to open the door to judicial relief until it

can fairly be said that discrimination persists despite

these new measures.

That the relief appellants seek concerns preparation

for a census which will not occur until 1970 reinforces

our view that the march of events has made the com

plaint premature. Although litigation involves delay and

time must be allowed to prepare for taking the census,

some considerable latitude would still seem to exist for

appraisal of the effectiveness of the new Voting Rights

Act before appellants turn in desperation once more to

the indirect sanction they believe to be imbedded in Sec

tion 2 of the Fourteenth Amendment.

Appellants argue that the Voting Rights Act is not

certain to eliminate the injuries which are the basis for

this suit. But we cannot speculate on that score. Congress

has selected the means it deems suitable. It should be

presumed that these measures will receive the support

that is commensurate with their high aims. If the Con

gressional means fall short of the Congressional ends,

whether through lack of enforcement or stubborn resist

ance, that is a matter to be explored by the trier of fact

at a later day.

In deciding to leave the District Court’s dismissal of

the complaint undisturbed, many of the contentions so

vigorously made by the parties are not reached. We

intend thereby neither to intimate any decision on the

14

merits of this ease, nor to disparage the seriousness of

the questions presented. Issues affecting the right to

vote touch upon “matters close to the core of our con

stitutional system.” Carrington v. Bash, 380 U.S. 89, 96

(1965). In telling appellants that events have made their

complaint unsuitable for judicial disposition at this time,

we think it also premature to conclude that Section 2

of the Fourteenth Amendment does not mean what it

appears to say.

Affirmed.