Reply Brief for Appellants

Public Court Documents

December 7, 1978

25 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Bolden v. Mobile Hardbacks and Appendices. Reply Brief for Appellants, 1978. 9d0b1289-cdcd-ef11-8ee9-6045bddb7cb0. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/7dbf10e1-66dd-42f4-b829-2a1059808c54/reply-brief-for-appellants. Accessed February 20, 2026.

Copied!

® *

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

OFFICE OF THE CLERK

WASHINGTON, D. C. 20543

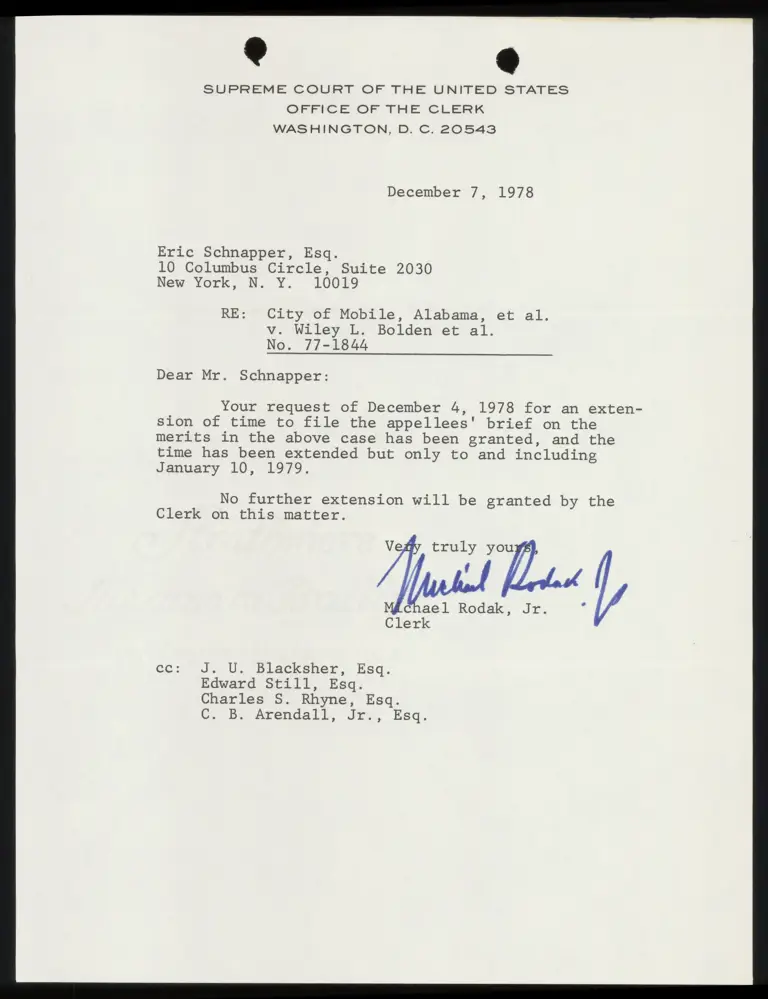

December 7, 1978

Eric Schnapper, Esq.

10 Columbus Circle, Suite 2030

New York, N. Y. 10019

RE: City of Mobile, Alabama, et al.

v. Wiley L. Bolden et al.

No. 77-1844

Dear Mr. Schnapper:

Your request of December 4, 1978 for an exten-

sion of time to file the appellees' brief on the

merits in the above case has been granted, and the

time has been extended but only to and including

January 10, 1979.

No further extension will be granted by the

Clerk on this matter.

V truly you

c

/ f

ael Rodak, Jr. .

Clerk

ce: J. U, Blacksher, Esq.

Edward Still, Esq.

Charles S. Rhyne, Esq.

C. B. Arendall, Jr., Esq.

IN THE

Supreme Court of the United States

OCTOBER TERM, 1978

No. 77-1844

CITY OF MOBILE, ALABAMA, et al.,

Appellants,

V.

WILEY L. BOLDEN, et al.,

Appellees.

ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES

COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

REPLY BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

C. B. ARENDALL, JR.

WILLIAM C. TIDWELL, III

TRAVIS M. BEDSOLE, JR.

Post Office Box 123

Mobile, Alabama 36601

FRED G. COLLINS

City Attorney

City Hall

Mobile, Alabama 36602

CHARLES S. RHYNE

WILLIAM S. RHYNE

DONALD A. CARR

MARTIN W. MATZEN

1000 Connecticut Avenue, N.W.

Suite 800

Washington, D.C. 20036

Counsel for Appellants

a I

THE CASILLAS PRESS, INC.—1717 K Street. N W.-Washington, 0. C.-223-1220

(i)

TABLE OF CONTENTS

ARGUMENT

I. NO ELECTORAL OBSTACLE, INTENTIONAL OR

OTHERWISE, TO FULL BLACK ELECTORAL

PARTICIPATION IS PRESENT IN THIS CASE

CONCLUSION

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases:

Beer v. United States,

425 U.S. 130

Brennan v. Arnheim and Neely, Inc.,

410 U.S. 512

City of Dallas v. United States,

Civil Action No. 78-1666 (D.D.C.)

Dallas County v. Reese,

421 U.S. 477

Dusch v. Davis,

387 U.S. 112

Fortson v. Dorsey,

379 U.S. 433

Gomillion v. Lightfoot,

364 U.S. 339

Nevett v. Sides,

571 F.2d 209 (Sth Cir. 1978),

petition for cert. filed, No. 78-492

Palmer v. Thompson,

403 U.S. 217

(ii)

Reynolds v. Sims,

77.8. 533... ih ine ee lS a a S

United Jewish Organizations of Williamsburgh,

Inc. v. Carey,

430).S 144s... ss a hee 2,5,9,10, 14

United States v. Pennsylvania Industrial

Chemical Corp.,

AEs ot ee oe ee es EB IR ae 2

Village of Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan

Housing Development Corp.,

5 2 BTR ET al BO re NR, 4,6,10,13

Washington v. Davis,

AOS. 20. es ae aes 1,10,13

Whitcomb v. Chavis,

4O3US. 124, . ss Er eines 5,8,9,14

White v. Regester,

C3 IE LOT ed ee aa ee a Re 3,5,9,14

Wise v. Lipscomb,

U.S. IBS. CL 293... ha ir 13

Zimmer v. McKeithen,

485 F.2d 1297 (Sth Cir. 1973)

(en banc), aff'd. sub nom. East Carroll Parish

School Board v. Marshall, 4241.85.636 . ...........c coven. 5

Constitution and Statutes:

U.S. Constitution

Amendment XIV . ii ieee passim

Amendmemt XV a. eae i i 1,2,9,10

Voting Rights Act of 1965, as amended, 42 U.S.C.

STARR ERT Sel Sa CE ol en OR ne 12

Section2, 42U.S.C.81973.. ....... consi iscninninivinna 1,2

Section 3,42 U.5.C. 819730... cites pre aie 2

(iii)

Miscellaneous:

National Roster of Black Elected Officials,

Joint Center for Political Studies,

Nolume S(1078Y .. iis nana reir 8

IN THE

Supreme Court of the United States

OCTOBER TERM, 1978

No. 77-1844

CITY OF MOBILE, ALABAMA, et al.,

Appellants,

v.

WILEY L. BOLDEN, et al.,

Appellees.

ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES

COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

REPLY BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

This Brief responds to the Brief for the Appellees in No.

77-1844," and to the Briefs of the United States (in Nos. 77-

1844 and 78-357) and the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil

Rights Under Law in No. 77-1844° as Amici Curiae.

ARGUMENT

At the outset, and in light of the attempt of the Appellees

to broaden the issues in this case without preserving issues

by cross-appeal, it is necessary to establish what is — and

what is not — involved in this particular case. This is a

Fourteenth Amendment case solely. Issues under the Fif-

teenth Amendment® and §2 of the Voting Rights Act, 42

'Cited Appellee Br., p. .

Cited U.S. Amicus Br., p. :

3Cited Lawyers’ Comm. Amicus Br., p.

‘Appellees continue to argue that a showing of purpose is not

necessary to a dilution claim under the Fifteenth Amendment, because

Washington v. Davis, 426 U.S. 229, did not expressly overrule dicta in

(footnote continued on next page)

U.S.C. §1973,° were rejected by the Court of Appeals below

and have not been cross-appealed.®

The attempt by the Appellees and their Amici to add in

their defense of the judgments of the courts below issues

rejected by the courts below, merely indicates the fear of the

Appellees and Amici of resolution of the Fourteenth Amend-

ment voting issue, the sole issue to which we devote the

balance of this reply.

The Defendants below were four: the City of Mobile and

its 3 incumbent Commissioners.” Neither the State of

Alabama nor any of its Legislators officially or personally

were joined. Thus, the focus of this case is whether the in-

cumbent City Commissioners created or maintained, with

racially discriminatory intent, an obstacle to full black par-

ticipation in City at-large elections.

(footnote continued from previous page)

Fortson v. Dorsey, 379 U.S. 433. This contention, rejected by the Fifth

Circuit in its opinion in the companion case of Nevett v. Sides, S71 F.2d

209, 217-221 (Sth Cir. 1978), pet. cert. filed, No. 78-492, which was in-

corporated in its opinion in this case, is both frivolous in light of United

Jewish Organizations v. Carey, 430 U.S. 144, 166-67, and not the subject

of any cross-appeal. See Brennan v. Arnheim and Neely, Inc., 410 U.S.

512, 516; United States v. Pennsylvania Industrial Chemical Corp., 411

U.S. 66S, 660-61 (Appellees not permitted absent cross-appeal to raise

issues resolved against them below).

*Appellees’ assertion that §2 of the Voting Rights Act affords them a

purpose-less cause of action for dilution was also properly rejected by

the Court of Appeals below (571 F.2d at 242 n. 3; Juris. St. 4a-5a) as

without foundation in any precedent. That section only recites

the language of the Fifteenth Amendment. Section S of the Act, 42

U.S.C. §1973c, which speaks of purpose and effect in the disjunctive,

has no application to the maintenance of at-large Commission elections

in Mobile. No cross-appeal has been taken on this point either.

*Similarly, not before the Court is Appellees’ attempt, Br. 37, to

argue that, contrary to the decision below, intent is not required under

the Fourteenth Amendment or Fifteenth Amendment, Br. S3, 82.

"App. 17.

The Amicus brief of the United States merges the City

(No. 77-1844) with the County School Board (No. 78-357);

but the facts of the two cases are different, the electoral

processes are different® and the administration of each is

different.’

The City case must be decided on its own facts.

Since there is no obstacle to full black participation

within the at-large system? in the City of Mobile, the Ap-

pellees must divert their attention to the maintenance of the

at-large system itself."

Since the record reflects no maintaining action (or inac-

tion) by the City Commissioners, the Appellees must divert

their attention to the actions of State Legislators."?

There is nothing in the record to suggest — and Ap-

pellees do not argue — that any Mobile Commissioners

8The City of Mobile has non-partisan elections. The only slating

organization of record below is the local branch of the National

Association for the Advancement of Colored People, the Non-Partisan

Voters League (NPVL). The NPVL endorsed the two white incumbent

City Commissioners who were opposed in the most recent City election.

The County School Board is elected in partisan elections at-large.

The Alabama Legislature is elected in partisan elections from single-

member districts.

*The City Commissioners are both legislators and administrators.

The County School Board appoints an administrator whose tenure and

duties would not be affected by either affirmance or reversal in No. 78-

357. In contrast, affirmance in No. 77-1844 will give effect to the 60-

page order (Juris. St. 1d-63d) establishing an entire and entirely new

administrative structure for the City of Mobile.

Therefore, the City is, both factually and constitutionally, different

from both the County School Board in No. 78-357 and the State

Legislature. See Opposition to Mot. to Affirm (No. 77-1844), pp. 1-S.

WCY.. White v. Regester, 412 11.8. 755, 767.

''All agree that an at-large electoral system is not per se un-

constitutional. Appellee Br., pp. 40-42; Lawyers’ Comm. Amicus Br.,

p. 4; U.S. Amicus Br., p. 41.

Appellee Br., pp. 21-24.

4

were involved in the proposal or defeat of any special elec-

toral legislation? concerning Mobile, cited throughout Ap-

pellees’ Brief.

So, at bottom, Appellees are left only with their next

argument, set out in their Brief, pp. 24-25:

“No black has ever been elected to the at-large

commission, and no black has ever won any at-

large election in Mobile City. . ..”"*

Thus, Appellees — and the Amicus Lawyers’ Commit-

tee'> — have only the argument that Appellees hereto-

fore'® have avoided: that the evil is the at-large system itself

and the description of the evil is the failure of the at-large

system to guarantee black Mobilians proportional

representation by race.

The Appellees urge this Court to correct the evil by

declaring a constitutional right in each voter to be represen-

ted by one of his own race, and a corresponding con-

stitutional obligation in all local governments to constantly

restructure themselves so as to insure this result.’

13The Appellees then quote from Arlington Heights, 429 U.S. 252

(Appellee Br., p. 24). The legislative intent on which the Court in

Arlington Heights focused was that of the defendant Village Board. By

analogy to their argument in this case, Appellees would see the proper

focus in Arlington Heights to be the state legislature in Springfield in

authorizing the village to make zoning decisions at all.

“But the United States admits, Br., pp. 43, 88, that no inference

arises solely from the failure to elect blacks.

'sLawyers’ Comm. Amicus Br., pp. 9-10.

'*See Mot. to Affirm, p. S.

7A logical implication of Appellees’ position is a right in white

citizens to resist maintenance of at-large elections where the black

voting population approaches S0%. Cf., the companion case Nevett v.

Sides, S71 F.2d 209, 214 n. 6 (Sth Cir. 1978), pet. cert. filed, No. 78-492.

In that circumstance, white voters would claim a Fourteenth Amend-

ment right to proportional representation by race.

5

This retrenchment of position forces Appellees and

Amici to oppose this Court’s decisions in Whitcomb v.

Chavis, 403 U.S. 124, White v. Regester, 412 U.S. 75S, and

United Jewish Organizations of Williamsburgh, Inc. v.

Carey, 430 U.S. 144, which hold that the focus of a con-

stitutional voting rights'® case is racial equality of electoral

access and participation rather than electoral result, and

that states are permitted — but not required — to provide

systems which guarantee proportional representation. It

leaves Appellees arguing that this Court did not mean what

it said in those cases, and urging a license for District Courts

such as the one below to dispense with meaningful find-

ings concerning concrete impediments to effective black

electoral participation in favor of speculation about the

causes and cures for the failure of any qualified black to

run for City Commissioner in Mobile, notwithstanding

black success at-large elsewhere.'’

'® Appellees proffer an ill-conceived analogy (Br. 61) between the sort

of claim they raise and the one-person, one-vote claim governed by the

rule of Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U.S. 533. They urge that at-large elections

“underweight” black votes. A Reynolds-type redistricting cures the evil

that, proportionally, voters are not represented by anyone. But Ap-

pellees’ class is underpresented only insofar as a black must be

represented by a black. At-large elections, of course, are a

mathematically perfect remedy for the one-person, one-vote problem.

See, e.g., Zimmer v. McKeithen, 485 F.2d 1297, 1301 (Sth Cir. 1973) (en

banc); aff'd sub nom. East Carroll Parish Sch. Board v. Marshall, 424

U.S. 626 (at-large plans have ‘‘zero population deviation”).

"See Appellants’ Br., p. 11 and n. 14.

I

NO ELECTORAL OBSTACLE, INTENTIONAL

OR OTHERWISE, TO FULL BLACK ELEC-

TORAL PARTICIPATION IS PRESENT IN

THIS CASE.

This brings us to the quality of evidence which the Ap-

pellees and Amici cite in defending the analysis of the

Courts below. The evidence is a search for a substitute for

that electoral obstacle which the Fourteenth Amendment

requires be proved, and whose existence the record in this

City case precludes.

The Appellees thus seek a form of license for district

judges to eschew evidence in favor of judicial notice as local

residents.’ If such license is given by this Court, there is

neither need nor ability in appellate courts to review the

local federal judicial soothsayers.

However, a review of the evidence in this case reveals a

complete absence of any voting obstacle and a complete ab-

sence of evidence of discriminatory intent by the Mobile

City Commissioners.

Appellees recount (Br., p. 75) the District Court’s “find-

ing”’ that Mobile blacks are denied access to the political

process because they are deterred from candidacy by the

certain prospect of defeat. The finding is hinged on the

existence of a phenomenon of white bloc voting, which as

the United States points out (U.S. Amicus Br., pp. 12-17),

was discerned not on the basis of any head-to-head contest

between black and white Commission candidates (because,

as the District Court found, there have been no serious or

20“In conducting the ‘sensitive inquiry’ contemplated by Arlington

Heights, the district judge [in No. 77-1844] was able to bring to bear an

understanding of local political, legislative and racial realities born of

years of legal, judicial and practical experience in the state.” Appellee

Bt... p- 35.

7

able black candidates for Commission seats)’ but on an

assessment of the electoral experience of a white candidate,

Joseph Langan, known to espouse civil rights causes and at-

tract solid support from blacks.?? The District Court, con-

tradicting the candidate’s own explanation (App. 111-15),

conjectured that his defeat in a 1969 bid for a fifth con-

secutive Commission term must have been attributable to

white backlash generated by the extent of his black sup-

port. The District Court, ignoring statistical evidence and

expert testimony that more recent City Commission elec-

tions had shown little racial polarization (App. S03-07),

elevated the so-called backlash to the status of a “‘usual”

pattern. 423 F. Supp. at 388, Juris St. 8b. Even the United

States concedes (U.S. Amicus Br., p. 16) that “race was not

a factor’ in any subsequent City Commission election.

21 Appellees attack (Br., p. 75) this negative description of the can-

didacies of those (3) blacks who have run as merely Appellants’ view. It

was, however, the finding of the District Court. 423 F.Supp. at 388,

Juris. St. 8b. Cf., for partisan elections to the County School Board in

No. 78-357, the discussion at U.S. Amicus Br., pp. 15-17, and 423

F.Supp. at 388.

The City does not agree to the Solicitor General’s intertwining of the

facts and law as to the political processes of the City with those of

the State Legislature, the Mobile County Government, and the Mobile

County School Board, all of whom have partisan primary elections and

a factual and legal record of their own which is inapplicable to the

record of the City of Mobile. Insofar as the Solicitor General attempts

to ignore this fact he falls into the errors of the District Court and the

Court of Appeals below, who, finding no evidence of intent adverse to

the City of Mobile, reached out and applied to the City the experience

and differing political processes of the County, School Board and

Legislature.

The Appellees go even further, by adopting findings from other cities

and other states. Br., p. 31-32.

22The District Court also relied for this conclusion on its own intuitive

understanding of ‘“‘common knowledge.” (App. 65-67) Cf., Palmer v.

Thompson, 403 U.S. 217, 224-26, where reversal was urged un-

successfully on the basis of common knowledge that the City of

Jackson, Mississippi had closed its swimming pools in order to avoid

the necessity of integration.

8

It is hardly undisputed (contrary to the United States’

suggestion, Amicus Br., p. 12) that “no . . . candidate iden-

tified with blacks has ever won an at-large election for any

office in or for the city. . . .”’ As we pointed out,?’ in the

City of Mobile, blacks participate vigorously in the elec-

toral process, identifying their preference principally

through the Non-Partisan Voters League, the only slating

organization active in the City’s nonpartisan elections.**

Appellees disparage (Br., p. 80) the impact of the NPVL'’s

endorsement by arguing that in 1973 Commissioner

Greenough’s opponent, Bailey, actually received a greater

share of the black vote in the City election. This attempt to

fill the vacuum in the District Court’s analysis only does it

further damage: Bailey was the candidate who had

defeated Langan in the 1969 City Commission contest so

23 Appellants’ Br., pp. 9-10.

The distinction between this case and Chavis is that there qualified

blacks ran rather than slated whereas here qualified blacks slated

rather than ran.

To give effect to this distinction is to hold that the only defense for a

City is to guarantee electoral victory by black candidates, qualified or

not. This Court would have to hold that no white Commissioner — not

even those endorsed by Mobile’s black leadership — is capable of fairly

administering a government for black Mobilians. (See App. 143).

This Court has ruled precisely to the contrary in Dallas County v.

Reese, 421 U.S. 477, and Dusch v. Davis, 387 U.S. 112.

As the Joint Center for Political Studies points out in commentary on

its roster of black elected officials, effective black political par-

ticipation cannot be measured simply by a count of black elected of-

ficials:

“Black political progress can be monitored in as many dif-

ferent ways as there are avenues of political activity. Public

officeholding is only one of the many ways in which blacks

may impact the political arena. Others include voter

registration; voting; membership in political parties or

other political organizations; service in appointive office;

and active support of and/or opposition to issues and can-

didates.”” National Roster of Black Elected Officials, Joint

Center for Political Studies, Volume 8 at xiv (1978).

9

crucial to the District Court’s theory about polarization and

backlash, a theory which posited Bailey to be anathema to

the black community.

The only real safeguard against such ex cathedra “find--

ings”’ by the district courts is a realistic requirement that

plaintiffs in such dilution cases as this prove the present

existence in the City’s voting or political processes of some

identifiable barrier to effective black participation, and

that the identified barrier is the result of an impermissible

racial purpose in the City’s incumbents.?®

>The Appellees see the gravamen of this case, not as the existence vel

non of an obstacle to full electoral participation, but the mere existence

of bloc voting. (Br., pp. 46-50, discussing White v. Regester and Whit-

comb v. Chavis. See also, Appellee Br., pp. 69-70). Neither Amici nor

Appellees make any attempt whatsoever to reconcile this view with this

Court’s decision in United Jewish Organizations, supra, that neither

the Fourteenth nor the Fifteenth Amendment touches the outcome of

elections, even where the regular outcome is minority defeat occasioned

by racially polarized voting. 430 U.S. at 166-67. Their putative distinc-

tion of Chavis (defeats explained by partisan rather than racial voting)

was explicitly rejected in United Jewish Organizations, 430 U.S. at 166-

67. Their argument (Br. 7, 44-46) that Regester turned on the effects

of racial voting, rather than the existence of exclusionary slating and

registration (absent here) suffers from the same infirmity. Id. The Ap-

pellees summarize:

“The franchise is a valuable right because it can be exer-

cised to decide ‘issue-oriented elections.’ [citation omitted]

But that right is rendered nugatory if candidates are

regularly defeated, not because of their ideas or ideology,

but because of the color of their skin or of that of their sup-

porters.” Appellee Br., p. 49.

This analysis requires findings which the social scientists in this case

said could not be made. The first is a finding that candidates are

defeated because of their race. Statisticians and political science ex-

perts steadfastly deny that their regression analyses admit of such

causal proof. (App. 60-61). They would express an inability to

distinguish this causation from that partisan or *‘issue-oriented’’ defeat

which Appellees, Br., p. 53, endorse. Moreover in this case where there

were no qualified black candidates, Appellees must assert that Com-

(footnote continued on next page)

10

The most chimerical of the findings in this case concern

the discriminatory intent which this Court has held

necessary to a Fourteenth or Fifteenth Amendment claim

in Washington v. Davis, 426 U.S. 229; Village of Arlington

Heights v. Metropolitan Housing Development Corp., 429

U.S. 252; and United Jewish Organizations, supra, 430

U.S. at 166-67.

The United States, Amicus Br., p. 38, says:

“[Tlhe claimed justification for at-large voting

was essentially that it produced political represen-

tatives with a broad, rather than a parochial,

view. But where, as in these cases, voting is

strongly polarized along racial lines, the broad

view is likely to be simply the view of the majority

racial group.”

This passage is offered to prove discriminatory intent in

the maintenance of the Commission form of government.

Yet, it assumes the missing premise, an assumption not

even the Fifth Circuit below makes. The missing premise

is that political representatives are capable of representing

only themselves, their party or their race.

(footnote continued from previous page)

missioner Langan was defeated — after being reelected for 16 years —

not by his race, but by the race of some of his supporters. Lacking

evidence of qualified black candidates, Appellees cite to a finding that

the at-large system itself must “discourage’’ qualified blacks from run-

ning. Appellee Br., pp. 75-76. To attempt to psychoanalyze not only the

candidates but every voter in Mobile in this fashion is ludicrous.

These are the findings which must be given effect if the judgment

below is to be affirmed. Appellants feel that findings of this character

are beyond the competence of any court, when the social science experts

called by plaintiffs refuse to indulge in them.

But outlandish findings are not needed in a proper vote dilution case.

Where the intentional creation or maintenance of an electoral obstacle

is proved, the case proceeds in a competent and reviewable fashion.

11

Amicus offers this assumption as an ipse dixit. Yet, if

true in a particular case, it is susceptible of proof: declining

to seek or accept black endorsement, and eschewing the

black vote, as well as the exclusion of any black input into

the nominating process. Thus, the missing premise was

proved in Regester.*®

That proof is lacking here: the record of the City case is

exactly contrary to the premise. The record reflects cam-

paigning for black endorsement, and the decisive quality of

that endorsement in City elections. (App. 141-42).

The evidence of racial intent upon which the District

Court below ordered a new City administrative structure

and on which the Court of Appeals affirmed the dis-

establishment of Mobile’s Commission form of govern-

ment, was that the Alabama Legislature had on two oc-

casions rejected authorization of a mayor-council, part

single-member district system for Mobile, and had been

conscious of the likelihood that such a measure would have

enhanced black candidates’ chances of election. The

repository of the only suggested ‘inactive maintenance’ in-

tent,”” the State Legislators, are elected from single-

member districts, specifically the 11-member Mobile Coun-

ty delegation to the House.?® The United States neglects to

mention that 3 of these 11 districted State legislators are

black. See 423 F.Supp. at 389.%°

There is no other electoral system under which the City of

Mobile can preserve its own and entirely separate, strong

local governmental interest.

26See also Nevett v. Sides, 571 F.2d 209, 222 (5th Cir. 1978), pet. cert.

filed, No. 78-492.

>’See U.S. Amicus Br., pp. 23, 28.

281 bid.

»Juris. St. 10b.

12

There is real irony in the fact that Mobile was faulted by

the Courts below because its 70-year-old at-large Com-

mission Government was not changed by the Legislature to

one which gave blacks a better chance to elect black of-

ficials. For the Voting Rights Act itself was designed and

intended to make electoral changes difficult, indeed

“freezing election procedures . . . unless they can be shown

to be nondiscriminatory’”’ was the purpose noted by this

Court in Beer v. United States, 425 U.S. 130, 140.

During the pendency of this litigation (App. 2595),

Alabama State Senator Roberts introduced legislation to

change the City’s government to a mayor-council plan in

which seven councilmen were to be elected by single-

member district, with two members of the council plus the

mayor to be elected at-large. (App. 249-50). The ‘“‘major

reason’ for its introduction was the Senator’s belief that

this would be ‘““a better form of government.” (App. 251).

He acknowledged that this was a view as to which

“reasonable men may reasonably differ” (App. 261), and

had attempted to alleviate somewhat the “tendency” of

councilmen ‘to be concerned just with their particular

district” by providing two at-large seats. (App. 253). The

Senator also felt that he had written the bill in such a way

as to eliminate “interference” by councilmen with parochial

concerns ‘‘in the day to day operations of the City.” (App.

259). Senator Roberts did not testify that his bill failed to

pass for reasons other than racially neutral legislative

disagreement with its policies and effectiveness. (App. 258).

Though the United States as Amicus now urges (Br., pp.

96-97) that some variant of the entirely at-large Com-

mission might have been adopted to retain its key feature of

at-large officials with mixed legislative/administrative func-

tions, it is clear that the Attorney General has longstand-

ing objections to the retention of at-large elements in any

electoral change subject to the Voting Rights Act. Even

now the United States is resisting the Dallas 8-3 plan with

13

which this Court dealt in Wise v. Lipscomb, LL.S.

, 98 S. Ct. 2493, with the assertion that retention of 3

at-large seats is suggestive of impermissible racial purpose.

Memorandum in Response to Plaintiffs’ Motion for Sum-

mary Judgment, pp. 24-28, in City of Dallas v. United

States, Civil Action No. 78-1666 (D.D.C.).

There is no reason to suppose that anything less than a

fully single-member districted plan for the City of Mobile

(e.g., the plan proposed by Senator Roberts) would have

been satisfactory to the United States if it had been adopted

by the Alabama Legislature.

The United States insists on proportional representation

by race.

Quite apart from the fact that the evidence showed that

much of the debate in the Alabama Legislature in this case

centered on the relative merits of the two forms of govern-

ment, Appellees’ flagrant hyperbole’® misses the mark

because the issue in the case is the intent of the Mobile City

Commission, not the intent of the non-party State of

Alabama or its Legislature.*’

3°Appellees characterize this as “two affirmative and express

legislative decisions” (Br., p. 35) and say that this proves that the

Legislature “acted from racial malice” (Br., p. 36) so stark as to come

within the ambit of Gomillion v. Lightfoot, 364 U.S. 339 (Br., p. 18).

Cf., Palmer v. Thompson, 403 U.S. 217, 224.

3' Amicus Lawyers’ Committee proffers a theory to fill this gap: that

the Mobile Commission knew that at-large elections unconstitutionally

deprive blacks of a right to proportional representation because

“public officials in the South can hardly claim to be unaware’ of that

fact. (Br., pp. 15, 19). Neither Court below, obviously, was willing to ex-

tend the “recognized effect” theory (rejected in both Washington v.

Davis, 426 U.S. at 252, and Arlington Heights, 429 U.S. at 260) quite

that far. The argument is also diametrically at odds with the position

taken by Appellees (Br., pp. 68-69, 70-71) that the at-large successes of

blacks around the country are not relevant to the Mobile City case.

14

There was no claim of any “discriminatory maintenance”

on the part of the City Commissioners or candidates, and

no showing even of any peripheral involvement of City of-

ficials in the Legislature’s treatment of these two bills.

Rather, the Commissioners’ interest in this case is in

retaining the Commission form itself. That form of govern-

ment is necessarily elected at-large. The strong govern-

mental interest in retaining a system where named ad-

ministrators are elected by, and responsible to, all

Mobilians exercising equal votes, is detailed at Juris. St.,

pp. 9-10. This interest is not replicated in any other case

before this Court, today or in Chavis or Regester.

Even assuming, however, that the transactions in the

Alabama Legislature are a salient consideration here, they

reveal no unconstitutional purpose whatever. At most they

embody a refusal to implement an ‘‘affirmative action”

measure that is constitutionally permissible but not con-

stitutionally required.

CONCLUSION

The principle on which Appellees’ case rides is the one

rejected in United Jewish Organizations. The distillate of

their lengthy brief and of the opinions below is this:

“White voters are entitled to cast their ballots on

any basis they may please, including that of race.

But they are not entitled to have the State

maximize the impact of racially based votes by

means of at-large elections.” (Br., p. SO).

Appellants say that this stands the rule clearly articulated

in Chavis, Regester, and United Jewish Organizations

precisely upside down. Minority groups are not entitled to

have the state maximize and concentrate their voting

strength so as to guarantee electoral victories. A con-

stitutional vote dilution case stands ready to eliminate

13

clearly identified obstacles created or maintained by the

Mobile Commissioners to full black electoral par-

ticipation.’> When the lack of an electoral obstacle is ad-

mitted — as it has been here — Mobile’s Commission form

should be permitted to continue.

Respectfully submitted,

C.B. ARENDALL, JR.

WILLIAM C. TIDWELL, III

TRAVIS M. BEDSOLE, JR.

Post Office Box 123

Mobile, Alabama 36601

FRED G. COLLINS

City Attorney

City Hall

Mobile, Alabama 36602

CHARLES S. RHYNE

WILLIAM S. RHYNE

DONALD A. CARR

MARTIN W. MATZEN

1000 Connecticut Avenue, N.W.

Suite 800

Washington, D.C. 20036

Counsel for Appellants

?We have pointed out that remedies exist for the other evils adum-

brated by Appellees: employment, municipal services, racial terrorism,

school segregation. See Appellants’ Br. p. 16 n. 19.