Pilot Freight Carriers, Inc. v. Walker Brief in Opposition to Certiorari

Public Court Documents

October 7, 1968

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Pilot Freight Carriers, Inc. v. Walker Brief in Opposition to Certiorari, 1968. f4253e3e-c19a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/7dc89c18-2f01-4553-907a-b276a18c9c39/pilot-freight-carriers-inc-v-walker-brief-in-opposition-to-certiorari. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

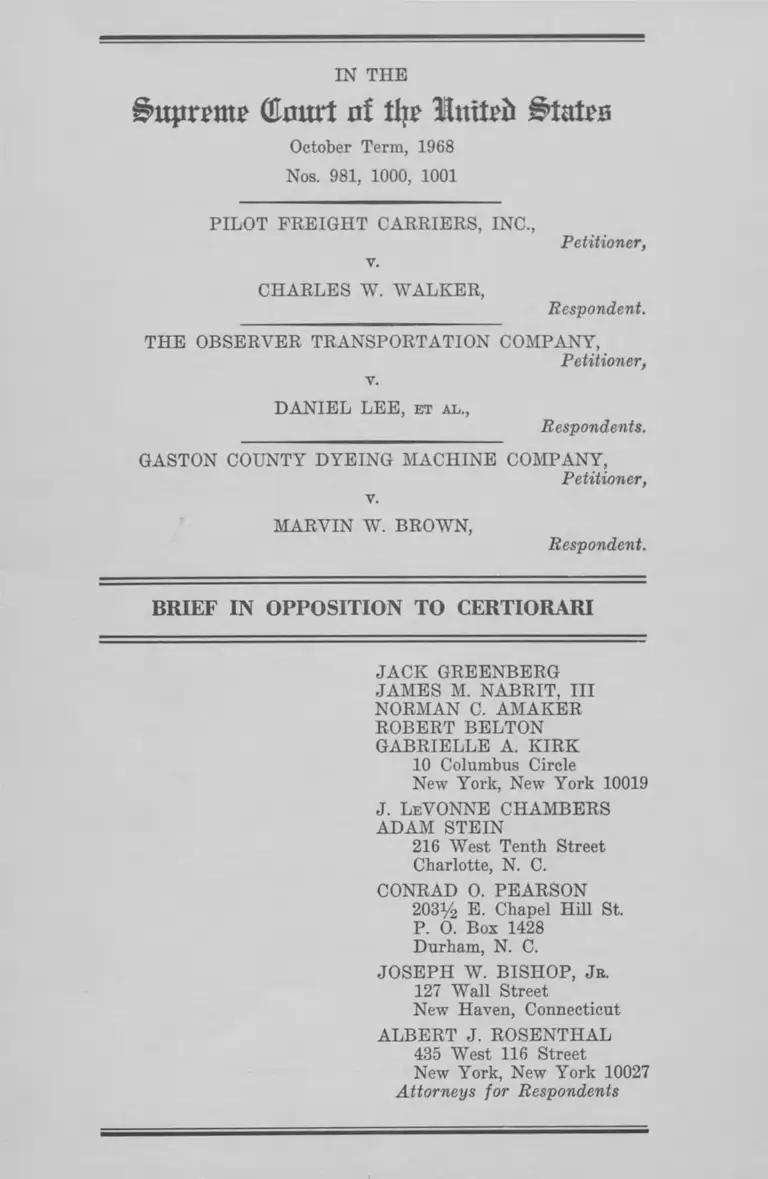

IN THE

gutprmp (Cmtrt of tip T&nxtib BtnUs

October Term, 1968

Nos. 981, 1000, 1001

PILOT FREIGHT CARRIERS, INC.,

Petitioner,

v.

CHARLES W . W ALKER,

Respondent.

THE OBSERVER TRANSPORTATION COMPANY,

Petitioner,

v.

DANIEL LEE, et al.,

Respondents.

GASTON COUNTY DYEING MACHINE COMPANY,

Petitioner,

v.

M ARVIN W . BROWN,

Respondent.

BRIEF IN OPPOSITION TO CERTIORARI

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT, III

NORMAN C. AM AKER

ROBERT BELTON

GABRIELLE A. KIRK

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

J. LeVONNE CHAMBERS

ADAM STEIN

216 West Tenth Street

Charlotte, N. C.

CONRAD O. PEARSON

2031/2 E. Chapel Hill St.

P. O. Box 1428

Durham, N. C.

JOSEPH W . BISHOP, Jr.

127 Wall Street

New Haven, Connecticut

ALBERT J. ROSENTHAL

435 West 116 Street

New York, New York 10027

Attorneys for Respondents

INDEX

Question Presented for Review ...................................... 1

Statement of the Cases ................................................... 2

Argument ......................................................................... 4

Conclusion ....................................................................................... 8

A ppendix—

Opinion of the Court of Appeals for the Fifth

Circuit in Dent v. St. Louis-San Francisco By.

Co............................................................................. la

Opinion of the Court of Appeals for the Fifth

Circuit in Burrell v. Kaiser Aluminum.............. 12a

Table of Cases

American Construction Co. v. Jacksonville, T.&K.Ry.

Co., 148 U.S. 372 .......................................................... 7

Anthony v. Brooks, 65 L.R.R.M. 3074 (N.D. Ga. 1967) .... 5

Bowe v. Colgate-Palmolive Co., 272 F. Supp. 332 (S.D.

Ind. 1967) ...................................................................... 5

Burrell v. Kaiser Aluminum & Chemical Co., 287

F. Supp. 289 (E.D. La. 1968) ........................................ 4

Burrell v. Kaiser Aluminum & Chemical Co.,------F.2d

------ (5th Cir. 1969) ..................................................... 4

Choate v. Caterpillar Tractor Co., 402 F.2d 357 (7th

Cir. 1968) ...................................................................... 4

Cox v. U. S. Gypsum Co., 284 F. Supp. 74 (N.D. Ind.

1968)

PAGE

5

11

Dent v. St. Louis-San Francisco Ry. Co.,------F.2d-------

(5th Cir. 1969) ............................................................ 4

Dent v. St. Louis-San Francisco Ry. Co., 265 F. Supp.

56 (N.D. Ala. 1967) ..................................................... 4

Edwards v. North American Rockwell Corp., 58 L.C.

H 9153 (C.D. Calif. 1968) ............................................ 5

Evenson v. Northwest Airlines, Inc., 268 F. Snpp. 29

(E.D. Va. 1967) .... 5

Hall v. Werthan Bag Corporation, 251 F. Supp. 184

(M.D. Tenn. 1966) ....................................................... 6

Hamilton-Brown Shoe v. United States, 240 U.S. 251 .... 7

Harris v. Orkin Exterminating Co., 58 L.C. 1f 9134

(N.D. Ga. 1968) .......................................................... 5

Hayes v. Seaboard Coast Line Ry. Co., 59 L.C. If 9196

(S.D. Ga. 1969) ............................................................ 5

Kendrick v. American Bakery Co., 58 L.C. If 9146 (N.D.

Ga. 1968) ..................................................................... 5

Mickel v. South Carolina State Employment Service,

377 F.2d 239 (4th Cir. 1967) ...................................... 6

Mickel v. South Carolina State Employment Service,

291 F. Supp. 910 (D.S.C. 1968) ................................. 5

Mondy v. Crown Zellerbach Corp., 271 F. Supp. 258

(E.D. La. 1967) ........................................................... 5

Moody v. Albemarle Paper Co., 271 F. Supp. 27 (E.D.

N.C. 1967) ...................................................................... 5

Pena v. Hunt Tool Co., 58 L.C. 11 9123 (S.D. Tex., 1968) 5

Pullen v. Otis Elevator, 292 F. Supp. 715 (N.D. Ga.

1968)

PAGE

5

Ill

PAGE

Quarles v. Philip Morris, Inc., 271 F. Supp. 842 (E.D.

Va. 1967) and 279 F. Supp. 505 (E.D. Va. 1968) ....... 5

Reese v. Atlantic Steel Co., 282 F. Supp. 905 (N.D. Ga.

1967) ............................................................................. 5

Sokolowski v. Swift and Co., 286 F. Supp. 775 (D. Minn.

1968) ............................................................................. 5

Wheeler v. Bohn Aluminum & Brass Co., 58 L.C. H 9137

W.D. Mich. 1968) .......................................................... 5

Statutes

Title VII, Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. §§ 2000e

et seq., section 706(e) ........................................1, 2, 3, 4, 6

Other Authorities

110 Cong. Rec. 14191 (June 17, 1964) ........................... 6

Stern and Gressman, Supreme Court Practice (3rd

ed. 1962) ....................................................................... 7

I n t h e

irtynmte CEmtrl nf tlw Unitrii

October Term, 1968

Nos. 981, 1000, 1001

P ilot P eeight Cabeiers, I nc .,

v.

Petitioner,

Charles W . W alker,

Respondent.

T he Observer T ransportation Company,

Petitioner,

v.

Daniel L ee, et al.,

Respondents.

Gaston County Dyeing M achine Company,

v.

Petitioner,

M arvin W . B rown,

Respondent.

BRIEF IN OPPOSITION TO CERTIORARI

Question Presented for Review

Was the Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit correct

in holding that conciliation efforts by the Equal Employ

ment Opportunity Commission (hereinafter referred to as

2

“the Commission” ) are not a jurisdictional prerequisite to

the institution of a civil action under section 706(e) of the

Civil Rights Act of 1964 by a person aggrieved, who has

exhausted his administrative remedy?

Statement of the Cases

These three cases are before the Court on petitions for

writs of certiorari from the same Court of Appeals; they

present the same legal issue with no substantial factual

differences. This Brief in Opposition, therefore, covers

all three cases. Cf. Rule 23(5) of the Rules of the Supreme

Court of the United States.

None of the facts in the cases are in dispute.

No. 981, Pilot Freight Carriers, Inc. v. Charles W. Walker

On February 28, 1966, the Respondent, Charles W.

Walker, filed with the Commission a charge (amended on

March 15, 1966) alleging a violation of Title VII of the

Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. §§ 2000e et seq. The

Commission investigated the charge and on July 20, 1966,

found reasonable cause to believe that its allegations were

true. By letter dated August 5, 1966, the Commission noti

fied the Respondent that due to its heavy workload it had

been “impossible to undertake or conclude conciliation,”

and that he had a right to institute a civil action within

thirty days of receipt of the letter. The Respondent com

menced this action by filing a complaint in the District Court

for the Western District of North Carolina on August 23,

1966. That court dismissed his complaint on January 25,

1968, on the sole ground that an effort to conciliate by the

Commission is a jurisdictional prerequisite to the right of

a person aggrieved to file a civil action. On October 29,

1968, the Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit reversed

the District Court.

3

No. 1000, Gaston County Dyeing Machine Company v.

Marvin W. Brown

On February 1, 1966, Respondent Brown filed a charge

of employment discrimination against Gaston County Dye

ing Machine Company with the Commission alleging

violation of Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The

Commission investigated the charge and rendered a deci

sion on May 5, 1966, finding “reasonable cause” to believe

the charge to be true. Brown was duly notified of the deci

sion by a letter dated May 12, 1966. By a letter also dated

May 12,1966, the Commission notified him that it had “been

impossible to undertake or conclude conciliation efforts”

in his case and that he had a right to institute a civil ac

tion within 30 days of the receipt of the letter. Brown com

menced an action by filing a complaint in the District Court

on May 31, 1966.

No. 1001, The Observer Transportation Company v.

Lee, et al.

Each Respondent herein filed a charge of employment

discrimination against The Observer Transportation Com

pany on or about February 28, 1966, alleging a violation of

Title VII. By a letter dated May 19, 1966, each was notified

by the Commission that the charge was still being processed;

that sixty days had elapsed since the filing of the charge;

and that he had a right to institute a civil action within 30

days from receipt of the letter. On June 9, 1966, the Com

mission found reasonable cause to believe that petitioner

had violated Title VII. Suit was filed on June 20, 1966, in

the District Court.

On March 22, 1968, the District Court dismissed the com

plaints in No. 1000 (Gaston County Dyeing Machine Co.)

and No. 1001 (The Observer Transportation Co.) on the

sole ground that an effort at conciliation is a jurisdictional

4

prerequisite to suit. On November 1, 1968, the Court of

Appeals for the Fourth Circuit reversed the dismissals of

these complaints.

Argument

The decision of the court below follows the plain language

of the statute. The explicit language of section 706(e) of

the Act places just two conditions upon the aggrieved per

son’s right to bring suit: that he have filed charges with

the Commission in proper form and that he have been

notified by the Commission that it has been unable (for

whatever reason) to obtain voluntary compliance. As the

court below pointed out, “ ‘Unable’ is not defined by statute

to give it a narrow or special meaning. We think ‘unable’

means simply unable—and that a commission prevented by

lack of appropriations and inadequate staff from attempt

ing persuasion is just as ‘unable’ to obtain voluntary com

pliance as a commission frustrated by the recalcitrance of

an employer or a union.” (Petition No. 981, p. 7a).

Both of the other Circuit Courts of Appeal which have

considered the question have reached the same conclusion

as the court below. Dent v. St. Lonis-San Francisco Ry. Co.,

------F.2d-------(5th Cir. 1969); Burrell v. Kaiser Aluminum

<& Chemical C o.,------F .2d------- (5th Cir. 1969), reversing

287 F. Supp. 289 (E.D. La. 1968)* Choate v. Caterpillar

Tractor Co., 402 F.2d 357 (7th Cir. 1968). The Dent case

reversed one of the few district court decisions to reach

an opposite conclusion, reported at 265 F. Supp. 56 (N.D.

Ala. 1967), a decision which was much relied upon by the

District Court and by the dissenting Circuit Judge in the

* The opinions of the Fifth Circuit in Dent v. St. Louis-San

Francisco Ry. Co., and Burrell v. Kaiser Aluminum & Chemical

Co., are not yet officially reported. A copy of Dent is reprinted

in the Appendix hereto at pp. la -lla , infra, and a copy of Burrell

is reprinted in the Appendix hereto at pp. 12a-13a, infra.

5

instant case. The great majority of district court decisions

are in accord with that of the Court of Appeals in the

present case. Mondy v. Crown Zellerbacli Corp., 271 F.

Supp. 258 (E.D. La. 1967); Bowe v. Colgate-Palmolive Co.,

272 F. Supp. 332 (S.D. Ind. 1967); Moody v. Albemarle

Paper Co., 271 F. Supp. 27 (E.D. N.C. 1967); Evenson v.

Northwest Airlines, Inc., 268 F. Supp. 29 (E.D. Va. 1967);

Quarles v. Philip Morris, Inc., 271 F. Supp 842 (E.D. Va.

1967) and 279 F. Supp. 505 (E.D. Va. 1968); Reese v.

Atlantic Steel Co., 282 F. Supp. 905 (N.D. Ga. 1967); An

thony v. Brooks, 65 L.R.R.M. 3074 (N.D. Ga. 1967); Sokol-

owski v. Sivift and Co., 286 F. Supp. 775 (D. Minn. 1968);

Cox v. U.S. Gypsum Co., 284 F. Supp. 74 (N.D. Ind. 1968);

Harris v. Orkin Exterminating Co., 58 L.C. H 9134 (N.D.

Ga. 1968); Pullen v. Otis Elevator, 292 F. Supp. 715 (N.D.

Ga. 1968); Pena v. Hunt Tool Co., 58 L.C. If 9123 (S.D. Tex.

1968) ; Wheeler v. Bolm Aluminum <& Brass Co., 58 L.C.

If 9137 (W.D. Mich. 1968); Kendrick v. American Bakery

Co., 58 L.C. fl 9146 (N.D. Ga. 1968); Edwards v. North

American Rockwell Corp., 58 L.C. If 9153 (C.D. Calif. 1968);

Hayes v. Seaboard Coastline Railroad Co., 59 L.C. 9196

(S.D. Ga. 1969).

The only district court decision to the contrary which

has not yet been reversed is Mickel v. South Carolina State

Employment Service, 291 F. Supp. 910 (D.S.C. 1968), which

is pending on appeal in the Fourth Circuit.

While the legislative history of the Act is, as the court

below recognized, less than clear and consistent, it certainly

does not compel a contrary construction. Overall, it sup

ports the Court of Appeals’ conclusion. Most of the state

ments cited to support the view that an effort by the Com

mission to conciliate is a prerequisite to the institution of

suit were made at a time when the bill contemplated judi

cial enforcement by the Commission itself. The more per

6

tinent statements made after the bill had been amended to

its present form, which places the burden of enforcement

on the alleged victim of discrimination rather than the

Commission, support the view that “ the Commission does

not hold the key to the court room door.” Statement by Sen

ator Javits at 110 Cong. Rec. 14191 (June 17, 1964).

The language and the legislative history of the Act make

it quite clear, and the Respondents certainly do not dispute,

that Congress intended the Commission, if it found reason

able cause to believe that a charge of discrimination was

true, to do what it could to correct the situation by concili

ation and persuasion. They make it equally clear that per

sons aggrieved by discrimination must have recourse to

the state and federal administrative remedies available to

them before resorting to the judicial remedy granted by sec

tion 706(e). This was in fact the holding of Michel v. South

Carolina State Employment Service, 377 F.2d 239 (4th Cir.

1967), which the Petitioners wrongly describe as incon

sistent with the Court of Appeals’ decision in the present

case. (Petition No. 981, p. 8.) But it is no less clear that

Congress did not intend the extreme unfairness of depriv

ing a victim of discrimination, who has exhausted the ad

ministrative remedies afforded him, of his judicial remedy

because of a circumstance wholly beyond his control: the

inability of the Commission to endeavor to effect concilia

tion. The Petitioners (Petition No. 981, p. 16; Petition No.

1000, pp. 13-14) seem to concede that, as Senator Javits

said, “The Commission may find the claim invalid; yet the

complainant can still sue.” 110 Cong. Rec. 14191 (June 17,

1964). See also the remarks of Senator Morse, Ibid.-, Hall

v. TVerthan Bag Corporation, 251 F. Supp. 184, 188 (M.D.

Tenn. 1966). The Petitioners thus appear to make the pre

posterous contention that Congress denied the Commission

power to deprive a complainant of judicial remedy by a

7

deliberate finding that bis complaint lacked merit, but em

powered it to achieve the same result by doing nothing.

Furthermore, the decisions below in which the Court of

Appeals reversed the granting of motions to dismiss and

ordered the cases remanded for trial are plainly interlocu

tory non-final judgments. While this Court plainly has the

power to review non-final judgments of the federal courts,

“ . . . in the absence of some . . . unusual factor, the inter

locutory nature of a lower court judgment will result in a

denial of certiorari.” Stern and Gressman, Supreme Court

Practice (3rd ed. 1962), p. 150. “This court should not

issue a writ of certiorari to review a decree of the circuit

court of appeals on appeal from an interlocutory order,

unless it is necessary to prevent extraordinary inconven

ience and embarrassment in the conduct of the cause.”

American Construction Co. v. Jacksonville, T.&K.R.Co.,

148 U.S. 372, 384. See Hamilton-Brown Shoe Co. v. United

States, 240 U.S. 251, 258 (lack of finality “of itself alone

furnished sufficient ground for the denial” ). These cases

have none of the exceptional characteristics that might

justify a review on certiorari at the present interlocutory

stage.

8

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, the petitions for writs of

certiorari should be denied.

Respectfully submitted,

Jack Greenberg

James M. N abrit, III

N orman C. A maker

Gabrielle A . K irk

10 Columbus Circle

New York, N. Y. 10019

J. L eV onne Chambers

A dam S tein

216 West Tenth Street

Charlotte, N. C.

Conrad O. Pearson

2031/2 E. Chapel Hill St.

P. 0. Box 1428

Durham, N. C.

Joseph W. B ishop, Jr.

127 Wall Street

New Haven, Connecticut

A lbert J. R osenthal

435 West 116 Street

New York, N. Y. 10027

Attorneys for Respondents

APPENDIX

IN THE

United States Court of Appeals

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

N o . 2 4 8 1 0

JAMES C. DENT and UNITED STATES EQUAL

EMPLOYMENT OPPORTUNITY COMMISSION,

Appellants,

versus

ST. LOUIS-SAN FRANCISCO RAILWAY

COMPANY, ET AL,

Appellees.

N o . 2 4 7 8 9

JOHN A. HYLER, ET AL,

Appellants,

versus

REYNOLDS METAL COMPANY, ET AL,

Appellees.

N o . 2 4 8 1 1

ALVIN C. MULDROW, ET AL,

Appellants,

versus

H. K. PORTER COMPANY, INC., ET AL,

Appellees.

-a DENT. ET AL v. ST. LOUIS-S. F. RY.. ET AL

N o . 2 4 8 1 2

WORTHY PEARSON, ET AL,

Appellants,

versus

ALABAMA BY-PRODUCTS CORPORATION, ET AL,

Appellees.

N o . 2 4 8 1 3

RUSH PETTWAY, ET AL, Individually and on behalf of

others similarly situated, and UNITED STATES EQUAL

EMPLOYMENT OPPORTUNITY COMMISSION,

Appellants,

versus

AMERICAN CAST IRON PIPE COMPANY,

Appellees.

Appeals from the United States District Court for the

Northern District of Alabama

(January 8, 1969)

Before COLEMAN and CLAYTON,* Circuit Judges,

and JOHNSON, District Judge.

•Judge Clayton, the third judge constituting the court, participated

in the hearing and the decision of this case. The present opinion

is rendered by a quorum of the court pursuant to 28 U.S.C.A.

§ 46, Judge Clayton having taken no part in the final draft of

this opinion.

DENT, ET A L v. ST. LOUIS-S. F. RY., ET A L 3a

COLEMAN, Circuit Judge: Because they present the

same legal issue, with no substantial factual differ

ences, these cases were consolidated for appellate dis

position. The District Court held that actual concilia

tion attempts by the Equal Employment Opportunity

Commission [proceeding under Title VII of the Civil

Rights Act of 1967, 42 U.S.C.A., §2000e et seq.] was

jurisdictionally prerequisite to the maintenance of an

action in the courts under Title VII, 265 F.Supp. 56

(N.D. Ala., 1967). We reverse.

The facts in the Dent case may be taken as illustra

tive of the group.

September 10, 1965, Dent filed with the Equa Em

ployment Opportunity Commission a charge that +he St.

Louis-San Francisco Railway Company and the Broth

erhood of Railroad Carmen of America were violating

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The substance

of the complaint was that the railway company had on

account of race, terminated the employment of Dent

and other Negroes, eliminated the job classifications m

which they were employed and excluded them from

employment in and training programs for other rb

classifications; that the railway company maintains

racially segregated facilities, and that the Brotherhood

of Railroad Carmen maintains racially segregated 1o-

cal unions, with Local No. 60 being all-white and Locai

No. 750 being all-Negro — these locals being the x-

clusive bargaining representatives of the employees

of the railway company.

4a DEN T, ET AL v. ST. LOUIS-S. F. RY., E T AL

October 8, 1965, copies of Dent’s charges were served

on the company and the Brotherhood.

December 8, 1965, the Commission issued a decision,

after investigation, to the general effect that there was

reasonable cause to believe that the company and the

Brotherhood were violating Title VII.

December 15, 1965, the company was informed of this

decision by letter from the Commission’s executive di

rector. This letter also discussed the Commission’s de

sire to engage in conciliation, but advised the com

pany that an action would possibly be filed before con

ciliation could be undertaken. On this point, the ex

ecutive director wrote:

“A conciliator appointed by the Commission

will contact you to discuss means of correcting

this discrimination and avoiding it in the fu

ture.

* * * *

“Since the charges in this case were filed in

the early phases of the administration of Title

VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the Com

mission has been unable to conciliate the mat

ter during the sixty (60) day period provided in

Section 706. The Commission is, accordingly,

obligated to advise the charging party of his

right to bring a civil action pursuant to Section

706 (e).

DENT, ET AL v. ST. LOUIS-S. F. R Y „ ET AL 5a

“Nevertheless we believe it may serve the

purposes of the law and your interests to meet

with our conciliator to see if a just settlement

can be agreed upon and a lawsuit avoided.

“ We are hopeful that you will cooperate with

us in achieving the objectives of the Civil Rights

Act and that we will be able to resolve the mat

ter quickly and satisfactorily to all concerned.”

There was no conciliation.

Neither the company nor the Brotherhood made any

effort to promote conciliation. Because of the unex

pectedly large number of complaints that were filed

with the Commission and the extremely small staff

available, the Commission made no further effort to

promote conciliation.

By letter dated January 5, 1966, the Commission ad

vised Dent that “ the conciliatory efforts of the Com

mission have not achieved voluntary compliance with

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964” . The letter

continued:

“Since your case was presented to the Com

mission in the early months of the administra

tion of Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964,

the Commission was unable to undertake ex

tensive conciliation activities. Additional con

ciliation efforts will be continued by the Com

mission . . . . Under Section 706 (e) of the Act,

you may within thirty (30) days from the re-

6a DEN T, E T A L v. ST. LOUIS-S. F. RY., E T AL

ceipt of this letter commence a suit in the Fed

eral district court.”

The action was filed in the District Court on Feb

ruary 7, 1966. As stated, the district court dismissed on

the ground that “conciliation . . . . is a jurisdictional

prerequisite to the institution of a civil action under

Title VII” .

Section 706 (e), 42 U.S.C. 2000e-5 (a), after making

reference to the receipt by the Commission of a charge

of unlawful employment practice, provides:

“The Commission shall . . . make an investi

gation of such charge . . . . If the Commission

shall determine, after such investigation, that

there is reasonable cause to believe that the

charge is true, the Commission shall endeavor

to eliminate any such alleged unlawful employ

ment practice by informal methods of con

ference, conciliation and persuasion.”

Section 706 (e), 42 U.S.C. 2000e-5 (e), provides:

“ If, within thirty days after a charge is filed

with the Commission . . . (except that . . . such

period may be extended to not more than sixty

days upon a determination by the Commission

that further efforts to secure voluntary com

pliance are warranted), the Commission has

been unable to obtain voluntary compliance

with this title, the Commission shall so notify

the person aggrieved, and a civil action may,

DENT, ET AL v. ST. LOUIS-S. F. RY., ET AL 7a

within thirty days thereafter, be brought a-

gainst the respondent named in the charge

)>

Section 706 (e) further provides:

“Upon request, the court may, in its discre

tion, stay further proceedings for not more

than sixty days pending . . . . the efforts of the

Commission to obtain voluntary compliance.”

Thus it is quite apparent that the basic philosophy of

these statutory provisions is that voluntary compliance

is preferable to court action and that efforts should be

made to resolve these employment rights by concilia

tion both before and after court action. However, we

are of the opinion that a plain reading of the statute

does not justify the conclusion that, as a jurisdictional

requirement for a civil action by the aggrieved em

ployee under Section 706 (e), the Commission must

actually attempt and engage in conciliation.

The United States Court of Appeals for the Fourth

Circuit recently considered and decided this issue in

companion cases, Ray Johnson v. Seaboard Coast Line

Railroad Company and Charles W. Walker v. Pilot

Freight Carriers, Inc.,____ F.2d-------- That Court held:

“ It seems clear to us that the statute, on its

face, does not establish an attempt by the Com

mission to achieve voluntary compliance as a

jurisdictional prerequisite. Quite obviously, 42

U.S.C. §2000e-5 (a) does charge the Commis

DENT, ET A L v. ST. LOUIS-S. F. RY., ET A L

sion with the duty to make such an attempt if

it finds reasonable cause, ‘but it does not pro

hibit a charging party from filing suit when

such an attempt fails to materialize’. Mondy v.

Crown Zellerbach Cory., 271 F.Supp. 258, 262

(E.D. La. 1967). Subsection (e), which contains

the authorization for civil actions, provides on

ly that the action may not be brought unless

within 30 days ‘the Commission has been un

able to obtain voluntary compliance.’

“The defendants argue that Section 2000e-5

must be read as a whole and that, so read, the

use of the word, ‘unable’, in subsection (e) im

plies that the duty imposed by subsection (a)

must be fully performed before a civil action is

authorized. We do not agree. ‘Unable’ is not

defined by statute to give it a narrow or special

meaning. We think ‘unable’ means simply un

able — and that a commission prevented by

lack of appropriations and inadequate staff

from attempting persuasion is just as ‘unable’

to obtain voluntary compliance as a commis

sion frustrated by the recalcitrance of an em

ployer or a union. Contra, Dent v. St. Louis-San

Francisco Ry. Co., 265 F.Supp. 56, 61 (N.D. Ala.

1967). At most, we think, a reading of the two

sections together means only that the Commis

sion must be given an opportunity to persuade

before an aggrieved person may resort to court

action. See Stebbins v. Nationwide Mut. Ins.

Co., 382 F.2d 267 (4th Cir. 1967); Mickel v. South

DENT, ET AL v. ST. LOUIS-S. F. RY., ET AL 9a

Carolina State Employment Serv., 377 F.2d 239

(4th Cir. 1967).”

Similarly, the United States Court of Appeals for the

Seventh Circuit considered and decided the same issue

in Choate v. Caterpillar Tractor C o.,____ F .2d_____ In

the following language, the Seventh Circuit rejected the

no-jurisdiction argument:

“ In the present case, although the complain

ant makes no allegation concerning the con

ciliation efforts of the Commission, it is clear

from the face of the complaint that the Com

mission had the opportunity to investigate and

conciliate, in that the Commission could have

investigated and attempted to conciliate be

tween the filing of the charge on March 14, 1966

and the issuance of its October 5, 1966 letter

stating that it had reasonable cause to believe

that a violation had occurred.

“We believe that these allegations are suf

ficient to state a claim under section 706. A

complainant may have no knowledge when he

received the required notification of what con

ciliation efforts have been exerted by the Com

mission. And more importantly, even if no ef

forts were made at all, the complainant should

not be made the innocent victim of a derelic

tion of statutory duty on the part of the Com

mission.”

10a DENT, ET AL v. ST. LOUIS-S. F. RY., ET AL

We particularly agree with the reasoning of the

majority in the Fourth Circuit cases and it is upon that

reasoning that we leverse the judgment below. See also

Oatis v. Crown Zellerbach Corp., 5 Cir., 1968, 398 F.2d

496, and Jenkins v. United Gas Corp., 5 Cir., 1968, 400

F.2d 28.

In arriving at the conclusion that actual conciliatory

efforts are jurisdictionally prerequisite, the District

Court relied heavily on the legislative history of the

Act. The majority and the dissenting opinions in John

son and Walker, 4 Cir., supra, extensively analyze this

aspect of the problem, obviating any necessity for

prolonged repetition here. As a matter of fact, the

Congressional committee reports and floor debates

lend great comfort to both sides. This, we believe,

leaves no clearly discernible Congressional intent,

certainly not enough to avoid plain statutory language.

Section 2000e-5 (e), Title 42, U.S.C.A. very clearly sets

out only two requirements for an aggrieved party be

fore he can initiate his action in the United States dis

trict court: (1) he must file a charge with the Equal

Employment Opportunity Commission and (2) he must

receive the statutory notice from the Commission that

it has been unable to obtain voluntary compliance. It

is extremely important in these cases that both the

spirit and the letter of Title VII reflect an unequivocal

intent on the part of Congress to create a right of

action in the aggrieved employee. The dismissal of

these cases deprived the aggrieved employee of that

right of action, not because of some failure on his part

to comply with the requirements of the Title, but for

the Commission’s failure to conciliate — a failure that

DEN T, E T AL v. ST. LOUIS-S. F. RY., ET A L 11a

was and will always be beyond the control of the ag

grieved party.

We do not overlook the fact that in November, 1966,

the Commission issued a regulation stating that it

“ shall not issue a notice * * * where reasonable cause

has been found, prior to efforts at conciliation witn

respondent,” except, that, after sixty (60) days from

the filing of the charge, the Commission will issue a

notice upon demand of either the charging party or

the respondent, 29 C.F.R. § 1601, 25a.

It may be that this regulation will generally put an

end to cases in the posture of that here decided.

In any event, these appeals are decided on the facts

and circumstances herein reported. The Court does not

have before it, and it is not now passing upon, a

situation, if there were to be one, in which the Com

mission as a matter of routine simply abandons all

efforts at actual conciliation.

It is not to be doubted that Congress did intend that

where possible these controversies should be settled

by conciliation rather than by litigation. The statute

ought to be so administered.

For the reasons herein enumerated, the judgment of

the District Court will be reversed and remanded for

further proceedings not inconsistent herewith.

REVERSED AND REMANDED.

Adm. Office, U.S. Courts— Scofields’ Quality Printers, Inc., N. O., La.

12a

IN THE

United States Court of Appeals

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

N o . 2 6 8 9 3

Summary Calendar

A. J. BURRELL, ET AL,

Plaintiff s-Appellants,

versus

KAISER ALUMINUM AND CHEMICAL COMPANY,

ET AL,

Defendants-Appellees.

Appeal from the United States District Court for the

Eastern District of Louisiana

i February 12, 1969)

Before BROWN, Chief Judge, THORNBERRY and

MORGAN, Circuit Judges.

PER CURIAM: Judicial pre-calendar screening un

der our new Rules 17-20 revealed that the District

Court dismissed this case' on the ground that “ Dent

'Burrell v. Kaiser Aluminum and Chemical Corp., E.D.La., 1968,

287 F.Supp. 289, 290.

B U R R E LL , ET AL v. K AISER ALM ., ETC., ET AL 13a

v. St. Louis-San Francisco Railway Co., D.C.. 265 F.

Supp. 56 (1967) is controlling here.”

Because Dent has been categorically overruled. Dent

v. United States Equal Employment Opportunity Com

mission, 5 Cir., 1969,____ F.2d ____ [Nos. 24810. 24789,

24811, 24812, 24813, January 8, 1969], we have conc’uded

that summary disposition of this appeal without oral

argument is appropriate. Accordingly, the Clerk has

been directed, pursuant to new Rule 18, to transfer this

case to the summary calendar and notify the parties

thereof.2

It follows, as in Dent, supra, the judgment must be

reversed and remanded for further consistent proceed

ings.

REVERSED AND REMANDED.

2ln order to establish ?. docket control procedure, the Fifth Circuit

adopted new Rules 17-20 on December 6, 1968. All four of

these new rules are reproduced in the Appendix to this opin

ion. For a general discussion of the need for and propriety of

summary review of certain appeals, see Groendyke Transport,

Inc. v. Davis, 5 Cir., 1969, ---------F.2d ---------- [No. 26812, Jan. 2,

1969],

For cases heretofore placed on the summary calendar see

Wittner v. United States, 5 Cir., 1969 --------- F.2d --------- [No.

25781,------------------ , 1969]; United States v. One Olivetti Elec. 10-

Key Adding Machine, 5 Cir., 1969, --------- F.2d --------- [No.

26676 ,------------------ , 1969]; United States v. One 6.5 mm. Mann-

licher-Carcano Military Rifle, 5 Cir., 1969, --------- F.2d ---------

[No. 26620, ------------------ , 1969]; NLRB v. Great A. & P. Tea Co.,

5 Cir., 1969, --------- F.2d --------- [No. 26134, ----------------- , 1969];

Thompson v. White, 5 Cir., 1989, --------- F.2d --------- [No. 26696,

------------------ , 1969]; Diffenderfer v. Homer, 5 Cir., 1969, — —

F.2d --------- [No. 26566, ------------------ , 1969]; Cohen v. Meadows,

5 Cir., 1969, --------- F.2d --------- [No. 26674, ----------------- , 1969];

Byrd v. Smith, 5 Cir., 1969, --------- F.2d --------- [No. 26683,

____________, 1969]; Hall v. United States, 5 Cir., 1969, ---------

F.2d ______ [No. 2G774, ____________, 1969]; Montos v. Smith, 5

Cir., 1969, --------- F.2d --------- [No. 26231, ------------------ , 1969],

M E IIEN PRESS INC. — N. Y C. <4^1^>219