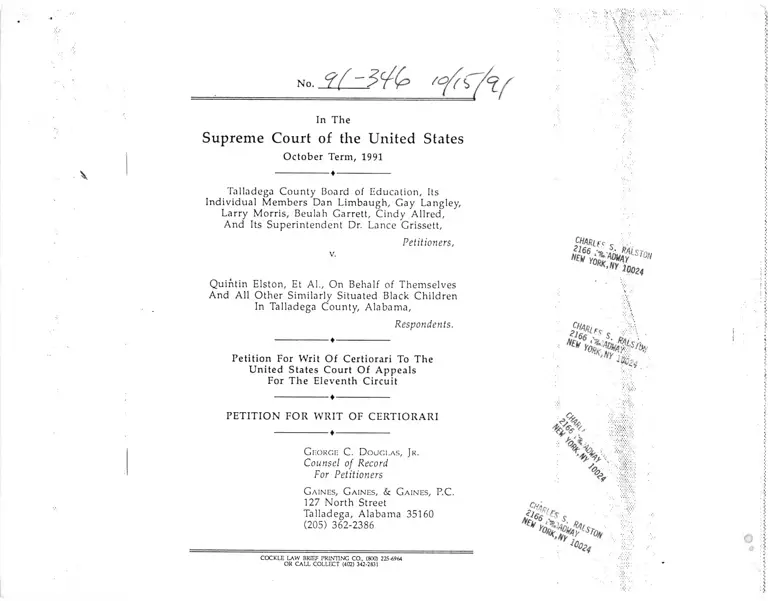

Talladega County Board of Education v. Elston Petition for Writ of Certiorari

Public Court Documents

October 15, 1991

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Talladega County Board of Education v. Elston Petition for Writ of Certiorari, 1991. 77fdbebb-c59a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/7de485c3-7bdc-4d19-b2b4-dd4e0472300e/talladega-county-board-of-education-v-elston-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari. Accessed February 20, 2026.

Copied!

No. < ? {

In The

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1991

Talladega County Board of Education, Its

Individual Members Dan Limbaugh, Gay Langley,

Larry Morris, Beulah Garrett, Cindy Allred,

And Its Superintendent Dr. Lance Grissett,

Petitioners,

v.

Quintin Elston, Et Al., On Behalf of Themselves

And All Other Similarly Situated Black Children

In Talladega County, Alabama,

Respondents.

Petition For Writ Of Certiorari To The

United States Court Of Appeals

For The Eleventh Circuit

---------------- ♦-----------------

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI

---------------♦---------------

George C. Douci.as, Jr.

Counsel of Record

For Petitioners

G aines , G aines, & G aines , P.C.

127 North Street

Talladega, Alabama 35160

(205) 362-2386

' i v.

ffiRUs s

TUK K ,H y j

!\ a

Ill

% .

. ■ j M

.;. J0°*4

COCKLE LAW BRIEF PRINTING CO., (800) 225-6964

OR CALL COLLECT (402 ) 342-2831

i

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

1. In this school desegregation case, did the Court

of Appeals depart from the "clearly erroneous" rule of

Fed.R.Civ.P. 52(a) by vacating the trial court's findings of

fact without holding they were clearly erroneous?

2. Did the Court of Appeals depart from the "harm

less error" mandates of Fed.R.Civ.P. 61 and 28 USC 2111

by vacating the trial court's judgment for abuse of discre

tion, without explaining why the stated error was not

harmless?

3. Does the Court of Appeals' judgment conflict

with Anderson v. Bessemer City, 470 U.S. 564 (1985) and

similar recent opinions of this Court, which carefully

limit the power of a federal appeals court to disturb a

trial court's findings of fact in a non-jury case?

4. Did the Court of Appeals depart from its own

precedent for reviewing abuse of discretion issues?

5. Should the trial court's judgment be reinstated by

this Court, since it rests on detailed findings of fact made

after a three day non-jury trial, which were not found to

be clearly erroneous by the Court of Appeals?

11

PARTIES TO THE PROCEEDING

All of the petitioners are listed in the caption.

In addition to the respondents listed in the caption,

the following persons were plaintiffs in the trial court

and appellants in the Court of Appeals, individually and

on behalf of all other black children alleged to be sim

ilarly situated:

Darius, Kierston and Gwynethe BALL; Delicia,

Loretta, Ronnie and Lecorey BEAVERS; Roslyn and John

nie COCHRAN; Tiffanie, Augustus and Cardella

ELSTON; Jerrok and Kate EVANS; Daniel, Althea, Vernon

and Estella GARRETT; Kereyell and Delia GLOVER; Step

hanie and Connally HILL; Ernest, Rayven, Rollen &

Helen JACKSON; Carla, Dorothy, Bertha, Willie and Paul

JONES; Danielle and Donald JONES; Datrea, Quinton and

Willie MORRIS; Jeffrey and Lela MORRIS; Quinedell and

Ouinell MOSLEY; Tiffani, Kedrick, Terry, Donyae and

Gwendolyn SWAIN; Cora, Louise, William and Veronica

TUCK; Jacques TURNER; Wendell and John WARE; Mon-

tina, Richard and Angie WILLIAMS.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

QUESTIONS PRESENTED.............................................. i

PARTIES TO THE PROCEEDING................................. ii

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI..................... 1

OPINIONS BELOW............................................................ 1

JURISDICTION OF THIS COURT................................. 2

STATUTES AND RULES INVOLVED........................... 2

STATEMENT OF THE CASE........................................... 3

BASIS FOR FEDERAL JURISDICTION....................... 5

REASONS TO GRANT THE WRIT............................... 5

APPENDIX.............................................................................A-l

Opinion Of The Court Of Appeals (April 30, 1991) . . . A-l

Findings Of Fact, Conclusions Of Law, And Judg

ment Of The District Court (September 19, 1989) .. . A-4

The Court Of Appeals' Order Denying Petition

For Rehearing (June 7, 1991)......................................A-27

Excerpts From Plaintiff's Brief On Abuse Of Dis

cretion Issues (May 4, 1990)......................................A-30

IV

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Page

O ases:

Anderson v. Bessemer City, 470 U.S. 564 (1985)............. 7

Bank of Nova Scotia v. U.S., 487 U.S. 250 (1988)......... 10

Cooter & Gell v. Hartmarx Corn., 496 U.S. ___, 110

L.Ed.2d 359 (1990)........................................................7> 12

McDonough Power Equipment v. Greenwood, 464

U.S. 548 (1984)................................................................... 8

Pullman-Standard v. Swint, 456 U.S. 273 (1982)............. 7

United States v. Gahay, 923 F.2d 1536 (11th Cir.

1991)........................................................................................

United States v. Lane, 474 U.S. 438 (1986)....................... 8

'Mited States v. Loyd, 743 F.2d 1555 (11th Cir. 1984) . . . . 11

United States v. Magdaniel-Mora, 746 F.2d 715 (11th

Cir. 1984)........................................................................... .....

F ederal R ules O f C ivil P ro ced ure :

Rule 52<a) ............................................................. 2, 6, 8, 10, 11

Rule 61........................................................................... 2 , 8, 10

S tatutes :

28 USC 2111 2, 9, 10

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI

TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE ELEVENTH CIRCUIT

The Talladega County Board of Education, its indi

vidual members and superintendent respectfully petition

for a Writ of Certiorari from this Court to review the

judgment of the United States Court of Appeals for the

Eleventh Circuit, which vacated a final judgment of the

United States District Court for the Northern District of

Alabama in favor of the defendants in this school deseg

regation and civil rights case.

This case has national significance. The issue is

whether there are any circumstances under which a court

of appeals may avoid the "clearly erroneous" and "harm

less error standards of review by reversing on other

grounds, without citing authority for its action, and with

out explaining why the perceived error was not harmless

or why it resulted in clearly erroneous findings of fact.

--------------- ♦------------ -—

OPINIONS AND ORDERS BELOW

The April 30, 1991 opinion of the Court of Appeals

was designated by that Court as not for publication. It is

reproduced in the Appendix at page A-l, and the order

denying rehearing is reproduced at page A-27.

The District Court's findings of fact, conclusions of

law, and judgment are reproduced in the Appendix

beginning at page A-4.

1

2

JURISDICTION OF THIS COURT

The Court of Appeals issued its opinion vacating the

District Court's judgment on April 30, 1991, and denied

Petitioners' timely application for rehearing on June 7,

1991.

This Court has jurisdiction to review the judgment by

certiorari under 28 USC Section 1254(1).

---------------4---------------

STATUTES AND RULES INVOLVED

1. Fed.R.Civ.P. 52(a) provides as follows:

"Findings of fact, whether based on oral or doc

umentary evidence, shall not be set aside unless

clearly erroneous and due regard shall be given

the opportunity of the trial court to judge of

the credibility of the witnesses."

2. 28 USC 2111 provides:

"On the hearing of any appeal or writ of cer

tiorari in any case, the court shall give judgment

after an examination of the record without

regard to errors or defects which do not affect

the substantial rights of the parties."

3. Fed.R.Civ.P. 61 provides:

" . . . no error or defect in any ruling or order or

in anything done or omitted by the court or by

any of the parties is ground for granting a new

trial or for setting aside a verdict or for vacating,

modifying, or otherwise disturbing a judgment

or order, unless refusal to take such action

appears to the court inconsistent with substan

tial justice. The court at every stage of the pro

ceeding must disregard any error or defect in

3

the proceeding which does not affect the sub

stantial rights of the parties."

---------------- ♦-----------------

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

Like virtually every other school system in Alabama,

the Talladega County Schools were made a party to the

original statewide desegregation suit styled Lee v. Macon

County Board Of Education, et a l, 267 F.Supp. 458 (MD Ala.

1967). The Talladega County Board Of Education ("The

Board") was dismissed from that suit on March 13, 1985

by consent of the plaintiffs and the U.S. Dept, of Justice.

The stipulation for dismissal acknowledged that the

Board had achieved a unitary school system.

In 1987 the Board decided to build a new elementary

school which would combine the elementary grades at

three existing schools in the northern part of Talladega

County. The plaintiffs opposed the new school location,

and filed a motion to reopen the Lee v. Macon case as to

Talladega County in July 1988. When this motion was

denied, plaintiffs filed this suit claiming that (a) the loca

tion of the new elementary school was racially motivated,

(b) the Board was allowing "zone jumping" (i.e. allowing

students to attend public school out of their assigned

attendance zones), and (c) that the Board had not imple

mented affirmative action plans regarding faculty and

staff in its schools. The .plaintiffs also made First Amend

ment and state claims based on the Board's alleged fail

ure to provide them with copies of certain documents and

allow them to make recordings of Board meetings.

4

Discovery was conducted in early .1989, and the Dis

trict Court conducted a three day non-jury trial beginning

on August 21, 1989. The trial court heard testimony from

18 witnesses, with numerous exhibits admitted into evi

dence.

On September 19, 1989 the District Court filed

detailed findings of fact and entered judgment for the

defendants. (Appendix p. A-4). The District Court found

that:

(a) The plaintiffs failed to prove any of their claims,

and the planned new school would provide a better edu

cation for all children attending it; (A-16, 17)

(b) That the new school's location was not racially

motivated, had no disparate impact on blacks, and was

" . . . consistent with the operation of a unitary, racially

nun-discriminatory public school system"; (A-17)

(c) That the Board neither allowed nor condoned

"zone jumping"; (A-18) and

(d) That "even though defendants had no burden of

proof, they have articulated and established by clear and

convincing evidence substantial, legitimate, non-discrimi-

natory reasons for the decisions and practices in ques

tion". (A-24).

In a one page order with no citation of authority, the

Court of Appeals vacated the District Court's judgment

on grounds that the trial court had abused its discretion.

The Eleventh Circuit stated that the District Court should

have granted the plaintiffs' motion for pro hac vice admis

sion of two other attorneys shortly after the suit was

5

filed, and should have allowed the plaintiffs' untimely

motion to add the Talladega City school system as an

additional defendant.

The Eleventh Circuit's opinion did not state that the

District Court's findings of fact were clearly erroneous,

and gave no explanation as to why the perceived abuses

of discretion were not harmless error, or why they had

led to clearly erroneous findings of fact or an otherwise

unjust result. (Appendix p. A-3).

------------------------------------ — -----------------------------------

BASIS FOR FEDERAL JURISDICTION

The district court had jurisdiction over this case pur

suant to 28 USC Sections 1331 and 1343(4).

-----------------♦------ -

REASONS TO GRANT THE WRIT

In this case, a Court of Appeals has vacated findings

of fact made by a District Court after a non-jury trial,

without any holding that the facts found were clearly

erroneous or that the perceived errors were not harmless.

Like any other error in the trial court, reversal for abuse

of discretion should be subject to the clearly erroneous

and harmless error standards of appellate review. Unless

the District Court s factual finding of no discrimination was

clearly erroneous , then the abuse of discretion perceived by

the Court of Appeals was necessarily "harmless error".

During the trial, the district judge heard testimony

from 18 witnesses, including one expert for the plaintiff,

and received numerous exhibits from both parties. One of

6

the main issues was the Board's elementary school plan;

during the trial the plaintiffs' expert admitted on cross-

examination that this plan was " . . . a good plan . . . a

pretty good plan".

After the trial, the district court entered detailed

findings of fact concerning the plaintiffs' claims, and

summarized its findings as follows:

" . . . plaintiffs have failed to establish by a

preponderance of the evidence that any of the

challenged decisions and practices were tainted

by a racially discriminatory animus. . . .

. . . Even though defendants had no burden of

proof, they have articulated and established by

clear and convincing evidence substantial, legit

imate, nondiscriminatory reasons for the deci

sions and practices in -question. . . . "

(Appendix p. A-24).

The Court of Appeals vacated the district court's

judgment on grounds that it had abused its discretion,

but without any discussion or citation of authority on

why its reversal was not subject to the clearly erroneous

or harmless error standards. The Court of Appeals' order

did not state that any of the district court's findings were

clearly erroneous, nor did it explain why the perceived

errors were not harmless.

Fed.R.Civ.P. 52(a) severely limits the power of an

appellate court to review or disturb facts found by a

District Court sitting as the trier of fact. An appellate

court must accept a District Court's finding of "ultimate

fact" on the issue of discriminatory intent, and may not

finding aside unless it is found to be clearly

7

erroneous. Pullman-Standard v. Swint, 456 U S 273

285-287 (1982).

This Court's recent opinion in Anderson v. Bessemer

City, 470 U.S. 564 (1985) emphasized that:

Rule 52(a) does not make exceptions or purport

to exclude certain categories of factual findings

from the obligation of a court of appeals to

accept a district court's findings unless clearly

erroneous." 7

S H’n at 574/ citinS Pull™™-Standard v. Swint,456 U.S. at 287.

Still more recently, in Cooler & Cell v. Hartmarx Corp,

496 U.S. ---- , 110 L.Ed.2d 359 (1990), this Court stated:

In practice, the 'clearly erroneous' standard

requires the appellate court to uphold any dis

trict court determination that falls within a

broad range of permissible conclusions. [Citing

Anderson v. Bessemer City, supra],

. . . If the district court's account of the evidence

is plausible in light of the record viewed in its

entirety, the court of appeals may not reverse it

even though convinced that had it been sitting

as the trier of fact, it would have weighed the

evidence differently. Where there are two per

missible views of the evidence, the factfinder's

choice between them cannot be clearly erro

neous; [Citing Inwood Laboratories, Inc. v Ives

Laboratories, Inc., 456 U.S. 844 (1982)].

. . . Whe n an appellate court reviews a district

court s factual findings, the abuse of discretion and

clearly erroneous standards are indistinguishable■ A

court of appeals would be justified in concluding

that a district court had abused its discretion in

making a factual finding only if the finding were

clearly erroneous." 6

8

496 U.S. a t___,110 L.Ed.2d at 378-379 (Emphasis

added).

It might be argued that the Eleventh Circuit did not

actually review or set aside the trial court's findings of

fact in this case, but merely vacated its judgment and

remanded for further proceedings. Such an argument

would ignore the obvious point that the trial court's

judgment was clearly based on the ultimate finding of

fact that no defendant was guilty of any racially discrimi

natory motives or actions as charged in the complaint.

The Eleventh Circuit necessarily had to vacate the District

Court's findings of fact to remand for further proceed

ings, because if those factual findings were accepted then

the defendants were entitled to judgment in their favor.

If the Court of Appeals had found any of the District

Court's factual findings to be clearly erroneous, then it

presumably would have said so and explained why. The

Court of Appeals' failure to discuss a clearly erroneous

analysis suggests that application of this standard would

not have allowed reversal.

It might also be argued that reversal was proper

because the perceived abuse of discretion affected the

facts which the plaintiffs could present or the actual trial

itself. This argument is met head-on by the harmless error

rule of Fed.R.Civ.P. 61:

"No error in either the admission or the exclu

sion of evidence and no error or defect in any

ruling or order or in anything done or omitted

by the court or by any of the parties is ground

for granting a new trial or for setting aside a

verdict or for vacating, modifying, or otherwise

disturbing a judgment or order, unless refusal to

9

take such action appears to the court inconsis

tent with substantial justice. The court at every

stage of the proceedings must disregard any

error or defect in the proceeding which does not

affect the substantial rights of the parties".

In the same way, 28 USC 2111 requires an appellate

court to " . . . give judgment after an examination of the

record without regard to errors or defects which do not

affect the substantial rights of the parties."

The commands of Rule 61 and 28 USC 2111 are as

clear as those of Rule 52, and perhaps more so. As this

Court emphasized in McDonough Power Equipment v.

Greenwood, 464 U.S. 548 (1984)

"The harmless error rules adopted by this Court

and Congress embody the principle that courts

should exercise judgment in preference to the

automatic reversal for "error" and ignore errors

that do not affect the essential fairness of the

trial . . . While in a narrow sense Rule 61 applies

only to the district courts, . . . it is well settled

that the appellate courts should act in accor

dance with the salutary policy embodied in Rule

61. [citations omitted]. Congress has further

reinforced the application of Rule 61 by enacting

the harmless-error statute, 28 USC 2111, which

applies directly to appellate courts and which

incorporates the same principle as that found in

Rule 61. [Citing Tipton v. Socony Mobil Oil Co.,

375 U.S. 34, 37 (1963) and U.S. v. Borden Co., 347

U.S. 514, 516 (1954)]."

464 U.S. at 553-554.

As this Court recently stated in United States v. Lane,

474 U.S. 438 (1986):

"Since Chapman [v. California, 386 U.S. 18 (1967)],

we have consistently made it clear that it is the

10

duty of a reviewing court to consider the trial

record as a whole and to ignore errors that are

harmless, including most constitutional viola

tions."

474 U.S. at 445.

If denial of the plaintiffs' motions for additional

attorneys and to add a defendant in some way affected

the essential fairness of the trial, the Eleventh Circuit

would have undoubtedly offered some explanation or

example to support reversal and illustrate why the error

was not harmless. The lack of such explanation, as with

the lack of a clearly erroneous analysis, suggests that the

Court of Appeals simply wished to reverse but had no

firm ground on which to do so.

The argument that a. court of appeals has inherent

supervisory power to correct procedural and trial errors

by a district court without regard to the harmless error

rule was rejected by this Court in Bank of Nova Scotia v.

U.S., 487 U.S. 250 (1988). This was a criminal case involv

ing Fed.R.Crim.P. 52(a), which contains the same harm

less error rule as Fed.R.Civ.P. 61 and 28 USC 2111. This

Court stated there:

" . . . Rule 52(a) provides that 'any error, defect,

irregularity or variance which does not affect

substantial rights must be disregarded.'

. . . federal courts have no more discretion to

disregard the Rule's mandate than they do to

disregard constitutional or statutory provisions.

The balance struck by the Rule between societal

cost and the rights of the accused may not casu

ally be overlooked because a Court has elected

to analyze the question under the supervisory

power."

11

487 U.S. at 255, citing U.S. v. Payner, 447 U.S.

727, 736 (1980).

This Court's opinions are very clear that no district

court judgment may be reversed for any reason, whether

abuse of discretion or otherwise, without a showing that

the error affected the essential fairness of the trial, and (if

a non-jury case), resulted in clearly erroneous findings of

fact. Rule 52(a) requires appellate courts to give the same

deference to a district court's findings when it sits as the

trier of fact as the Seventh Amendment requires in jury

cases.

Finally, it might be argued that the Court of Appeals

implicitly considered the clearly erroneous and harmless

error rules even though its opinion did not expressly say

so. This would overlook the fundamental obligation of a

reviewing court to explain both the standard of review it

applies and the basis for its reasoning. Without such

explanations, this Court would have no way of assuring

that the courts of appeal were uniformly and consistently

adhering to the proper standards of review.

Besides departing from the recent opinions of this

Court, the Eleventh Circuit's opinion in this case

departed from its own precedent for reviewing abuse of

discretion issues. In numerous recent decisions, the Elev

enth Circuit has stated that " . . . a showing of prejudice is

necessary for the Court to find an abuse of discretion".

U.S. v. Loyd, 743 F.2d 1555, 1564 (11th Cir. 1984). Likewise

in U.S. v. Magdaniel-Mora, 746 F.2d 715, 718 (11th Cir.

1984), Judge Vance wrote that in order to establish an

abuse of discretion the defendant must show that he was

" . . . unable to receive a fair trial and . . . suffered

compelling prejudice against which the trial court could

12

offer no protection". And in U.S. v. Qabay, 923 F.2d 1536

(11th Cir. 1991) the Eleventh Circuit stated that a trial

court had " . . . broad discretion in handling a trial" and

that an appellate court . . . will not intervene absent a

clear showing of abuse".

Although the plaintiffs argued abuse of discretion in

their brief, they made no attempt to show how they had

been denied a fair trial as a result of the alleged abuse of

discretion, or how the outcome of the case would proba

bly have been different, or how the ostensible abuse led

to factual findings that were clearly erroneous. (See p.

53-55, "Brief for Appellants", dated May 4, 1990, Appen

dix p. A-30). The Eleventh Circuit's opinion contained no

discussion or explanation of how the plaintiffs had car

ried their burden of showing a clear abuse of discretion

or why they had suffered'substantial prejudice as a result

of the alleged errors.

The trial court's judgment in this case was supported

by detailed findings of fact, entered after hearing testi

mony from eighteen witnesses and considering numerous

exhibits. The plaintiffs' own expert admitted that the

challenged elementary school plan was "good . . . pretty

good". The District Court's judgment clearly falls within

the "broad range of permissible conclusions" referred to

by this Court in Cooter & Gell v. Hartmarx, and is more

than plausible in light of the record as a whole. Under

these circumstances, this Court should reverse the judg

ment of the Court of Appeals and reinstate the judgment

of the District Court.

♦

13

CONCLUSION

The Court of Appeals effectively vacated the District

Court's findings of fact while ignoring the clearly erro

neous and harmless error standards of review.

This case presents the Court with the opportunity to

emphasize once more that the power of federal appeals

courts to disturb the findings of a district court is very

limited, and may not be exercised for any reason without

application of the clearly erroneous and harmless error

rules.

The judgment of the Court of Appeals should be

reversed, and the District Court's judgment reinstated.

Respectfully submitted,

G eorge C. D ouglas , Jr.

Counsel Of Record For Petitioners

G aines , G aines & G aines, RC.

127 North Street

Talladega, Alabama 35160

(205) 362-2386

A-l

APPENDIX 1

DO NOT PUBLISH

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE ELEVENTH CIRCUIT

No. 89-7777

D. C. Docket No. CV-88-H-2052-E

QUINTIN ELSTON; RHONDA ELSTON; and

TIFFANIE ELSTON, all minor children, by

and through their parents and guardians,

AUGUSTUS ELSTON, and CARDELLA ELSTON;

on behalf of themselves and all other similarly

situated black children and parents or

guardians of black children in

Talladega County in the

State of Alabama, etc., et al.,

Plain tiffs-Appellants,

versus

TALLADEGA COUNTY BOARD OF

EDUCATION; LANCE GRISSETT;

DAN LIMBAUGH; M. R. WATSON;

GAY LANGLEY; and LARRY MORRIS

and BEULAH GARRETT;

Defendants-Appellees.

JOSEPH POMEROY,

Defendant.

A-2

89-7917

TORRANCE BECK, a/k/a

Albert Beck, Jr.,

Plaintiff,

QUINTIN ELSTON, RHONDA ELSTON, and

TIFFANIE ELSTON, all minor children,

by and through their parents and

guardians, AUGUSTUS ELSTON and

CARDELLA ELSTON; on behalf of

themselves and all other similarly

situated black children in Talladega

p nunty in the State of Alabama,

Plain tiffs-Appellants

versus

TALLADEGA COUNTY BOARD OF EDUCATION'

LANCE GRISSETT; DAN LIMBAUGH; M. R.

WATSON; GAY LANGLEY; LARRY MORRIS;

and BEULAH GARRETT,

Defendants-Appellees.

Appeals from the United States District Court

for the Northern District of Alabama

(April 30, 1991)

Before TJOFLAT, Chief Judge, DUBINA, Circuit Judge,

and HENDERSON, Senior Circuit Judge.

PER CURIAM:

Appellants' appeal from the district court's judgment

in favor of the appellees on appellants' claims under Title

A-3

VI, Title VII and the equal protection clause of the four

teenth amendment.

During proceedings in this case, the district court

denied the appellants' motion to add the Talladega City

Board of Education as a party defendant and also denied

a motion for admission pro hac vice of two attorneys for

the appellants from the NAACP Legal Defense Fund. We

find that the district court abused its discretion in deny

ing these motions.

Accordingly, we vacate the judgment of the district

court and remand this cause with directions to the district

court to grant the motion for leave to amend, grant the

motion for admission pro hac' vice, permit such addi

tional discovery as may be necessary and conduct such

additional evidentiary hearings as determined appropri

ate by the court.

VACATED and REMANDED with directions.

A-4

APPENDIX 2

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE

NORTHERN DISTRICT OF ALABAMA

EASTERN DIVISION

QUINTIN ELSTON, ET AL„

PLAINTIFFS,

VS.

TALLADEGA COUNTY

BOARD OF

EDUCATION, ET AL„

DEFENDANTS.

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

CV88-H-2052-E

(Filed Sep 19, 1989)

FINDINGS OF FACT

AND

CONCLUSIONS OF LAW

This action was tried before the court, without the

aid of a jury, on August 21, 22 and 23, 1989. The matter is

now under submission and the court herein sets forth its

findings of fact and conclusions of law. Pursuant to the

Pretrial Order, counsel for the parties filed with the court

on August 11, 1989 a statement of agreed and disputed

facts. The court's findings of fact and conclusions of law

are basically addressed to the proposed facts contained in

that document in the order and under the headings set

forth therein.

Stipulated Facts

In 54 separately numbered paragraphs the parties

stipulated a number of facts and each of those stipulated

facts are accepted by the court as facts for the purposes of

this action. The court does, however, note that at least

A-5

one of those stipulated facts may not be correct but any

error is relatively immaterial. In paragraph 13 of the

stipulated facts, counsel stipulated that defendants' plan

for the students currently residing in Jonesview and Tal

ladega County Training School zones to attend Talladega

County Training School for grades 7 through 12. Defen

dant Lance Grissett has such plan and will recommend

such to the Board of Education but the Board of Educa

tion has not formally approved such plan.

Plaintiffs' proposed factual findings

In 44 separately numbered paragraphs counsel for

plaintiffs presented to the court proposed factual find

ings. The court will now set forth, using the same para

graph numbers, some of its findings of fact and

conclusions of law germane to each proposed factual

finding. The failure to include the language or the "facts"

as proposed by counsel for plaintiffs could generally be

viewed as a determination by the court that the proposed

language or "facts" have not been established or are

embraced in other findings or conclusions found else

where in this document.

1. Defendants plan to discontinue grades K-6 at

Jonesview (an historically white school) and at Talladega

County Training School (an historically black school) and

to relocate those grades at the site of the former Idalia

School (which burned in 1986) in a new school building

which will house grades K-6 from the three school zones.

2. Black parents have contributed significant time

and financial resources to support and enhance the

A-6

Talladega County Training School. Despite these contri

butions and the expenditures by the Board of Education

for maintenance and improvements over the years, the

Training School, like other schools in the system, has

generally deteriorated. A renovation and rebuilding pro

gram has been underway for several years and Talladega

County Training School is slated for substantial renova

tion in the immediate future. Several historically white

schools are not as far along as Talladega County Training

School in the renovation plans.

3. Assignment of all students from the new school

to the Talladega County Training School for grades 7-12

would add about 135 white students to the Training

School which would significantly improve integration at

the Training School. About 55 of those students would

come from Jonesview Elementary School zone and

approximately 80 would be supplied by Idalia Elemen

tary School zone. While it seems clear the Jonesview

students will be so assigned, the Board has not made a

decision as to where the Idalia students will be assigned.

4. Although the Board has never formally voted to

close the elementary section of the Talladega County

Training School or voted to close Jonesview Elementary

school, when the Board approved the construction of the

new 500 pupil school to be known as Stemley Bridge

Road Elementary, implicit in that decision was the closure

oi jonesview and the elimination of elementary grades at

the Talladega County Training School.

5. The Talladega County Board of Education has not

finalized where students attending the new school who

currently live in the Idalia School zone will go for grades

A-7

7-12, but the Superintendent presently intends to recom

mend that many of them attend Drew Middle School for

grades 7-8 and Lincoln High School for grades 9-12 which

are the schools those students have historically been

zoned to attend.

6. Defendants plan to renovate the Talladega

County Training School for use as a 7-12 facility. As of

June 1988, the estimated expenditure on renovation for

the Training School was $500,000.

7. The construction of a new school at the site adja

cent to the Idalia School, originally estimated to cost

about $1,200,000, later estimated to cost $1,800,000, is

now anticipated by defendants to cost almost $2,600,000.

8. The plan to renovate all buildings at the Training

School for use in the operation of a grades 7-12 school

would cost essentially the same whether the new elemen

tary school is located there or elsewhere. The cost of

construction of a new school building containing about

53,000 gross square feet for use as a K-6 grade school for

about 550 students would be approximately the same

whether constructed at the Idalia or at the Talladega

County Training School site.

9. In 1988 the Board relocated the Phyllis Wheatley

Middle School, which historically was a black school, to a

new facility about a mile from its former site. Although

its name was changed to Childersburg Middle School, its

attendance zones, faculty and bus routes did not change.

The composition of the student body remained the same.

10. Some black parents, including Mr. Charles

Woods (a local leader), objected to moving the Wheatley

A-8

School to the new location and changing the name. Mr.

Woods believed the plan was racially motivated and part

of a pattern of closing historically black schools. He asked

to be allowed to meet with the Talladega County Board of

Education to express his opposition to the moving of

Phyllis Wheatley but was not successful in arranging

such a meeting.

11. Under the terms of a resolution adopted

i\uvcmber 22, 1983 by the Talladega County Board of

Education and filed in this court in Lee v. Macon County

prior to the March 13, 1985 "unitary" order, the Board

committed itself to maintaining a unitary, nondiscrimina-

tory school system. There is no evidence that it has vio

lated this commitment since March 13, 1985; and the

court is satisfied that the Board's actions and decisions

challenged in this suit do not violate that commitment.

12. Prior to the March 13, 1985 order (a) determin

ing that the Talladega County School System had attained

unitary status and (b) dismissing the Talladega County

Board of Education from the Lee v. Macon County litiga

tion, the Board decided to close Hannah Mallory Elemen

tary School, a 100% black school with grades K-6, at the

end of the school year 1984-85. A formal "closure" resolu

tion was adopted in the summer of 1985. 13 * * * * * *

13. When the Hannah Mallory School was closed

after the 1984-85 school year, the Hannah Mallory atten

dance zone was divided among three attendance zones

primarily on a proximity basis. Prior to the March 13,

1985 unitary order, defendants had submitted to the

Department of Justice the proposed closing of Hannah

Mallory and the anticipated distribution of its students as

A-9

actually distributed. The plan envisioned assigning the

132 black students at Hannah Mallory as follows: 26 -

Childersburg; 26 - Jonesview; 80 - Talladega County

Training School. Childersburg zone, Jonesview zone and

Talladega County Training zone all received the Hannah

Mallory students, all of whom were black.

14. As a result of the zoning changes made in 1985

when Hannah Mallory was closed, about 132 black stu

dents were reassigned to the three zones earlier men

tioned. The following school year, as a result of a

combination of those assignments and natural or normal

enrollment fluctuations, black student enrollments in

grades K-6 in the three receiving school districts

increased as follows: Jonesview went from 85 to 116;

Childersburg went from 134 to 147; and Talladega County

Training went from 134 to 236.

15. This increase crowded the facilities at the Train

ing School and required the use of some portable class

rooms. Disbursement of the Hannah Mallory students

among the three receiving zones promoted integration in

the Childersburg zone, adversely affected integration in

the Jonesview zone and had no significant effect on inte

gration at Talladega County Training School. The

increased concentration of black students at the Training

School makes it more difficult to desegregate the Training

School, but the planned new school will dramatically

improve the black-white ratio for the students who cur

rently attend grades K-6 at the Training School. Those

students currently are in an environment which is 99%

black and will be in an environment that is 70-75% black.

A-10

16. This proposed fact has not been established.

17. This proposed fact has not been established.

18. The additional K-6 zone that was created for the

Training School following the closure of Hannah Mallory

is not contiguous with the original Training School K-6

zone and in this respect it is unique; but the K-6 zone is

contiguous to a then existing Training School 7-12 zone.

19. There is property adjacent to the Talladega

County Training School which if acquired by gift, pur

chase or condemnation, would have been suitable for

expansion. This includes property owned by members of

the Dumas family and the Lawson family. A minimum of

15 acres were needed for the new school and the Board

ultimately was able to acquire for the new school 48 acres

at the Idalia site in October of 1987. 20

20. Inquiries in the spring of 1988 made to a repre

sentative of the Dumas property owners by the principal

of the Talladega County Training School, Mr. John

Stamps, caused Mr. Stamps to conclude and to report that

the Dumas owners after resolving a boundary line prob

lem with the Board, might be receptive to offers to pur-

^ase or swap land and might even donate some property

to the school. The Dumas representative seemed partic

ularly concerned that a portion of their land might be

across the road and was being used by the school as

school land. All of this took place after the Board of

Education had acquired a 48 acre site at Idalia and made

the decision to build the new school at the Idalia site and

also after including funds for construction of the new

school in the bond issue authorized December 1, 1987.

A-l 1

21. In 1988, Mr. Stamps inquired of a representative

of the Lawson family whether it would consider the sale

of about 6 acres of property adjacent to the school. This

was adjacent to the football field and was not a suitable

site for a new school facility. The representative reported

that if absolutely necessary, the family might consider a

sale. This conversation also took place after the Board

had acquired the 48-acre site at Idalia.

22. There is no evidence that the Board sought opin

ions from parents, black or white, of students to be

affected by the decision to create a single large elemen

tary school to serve the Jonesview, Talladega County

Training and Idalia zones. Board meetings, however, have

been open to all parents and interested persons. The

Board sets aside a portion of each meeting to receive

comments, complaints, etc., from members of the public

in attendance.

23. On January 21, 1988, Mr. Augustus Elston wrote

Superintendent Grissett noting that concerned parents

with children in attendance at Talladega County Training

High School were requesting permission to be heard at

the next meeting of the Talladega County Board of Educa

tion. The letter stated that "[t]here are many items of

grave concern that we need to discuss." This letter was

also sent to the other Board members. The next day the

Superintendent of the Board wrote to Elston, referring

him to Principal Stamps and saying he (the Superinten

dent) would be glad to meet with Mr. Elson, if necessary.

This letter was followed up by a telephone call from

Principal Stamps to Mr. Elston.

A-12

24. On January 27, 1988, Mr. Elston again wrote to

Dr. Grissett requesting that concerned parents of Tal

ladega County Training High School be allowed the

opportunity to be heard at the next Board meeting. The

letter requested that if the parents were not following the

proper channels to get on the agenda, that they be

;nformed of the correct procedure. Copies were sent to

the other Board members. No response to this letter was

made by any Board member or Dr. Grissett.

25. On February 9, 1989, Mr. Elston wrote to Dr.

Morris, Chairman of the Talladega County Board of Edu

cation, complaining about an atmosphere of racism and

racially prejudiced occurrences, and expressed concern

that the Training School had been marked for closure and

been excluded from recent planning for facility improve

ments. Four days later the Chairman of the Board of

Education responded, specifically referring to the Tal

ladega City Training School concerns and welcoming

them to a Board meeting to voice any concern. Mr. Elston

attended the next Board meeting but when the time set

aside to receive public comments arrived, Mr. Elston did

not speak up. Mr. Elston explains this silence by his belief

mat it was too late in the meeting for the Board properly

to consider his concerns.

26. This proposed fact has not been established.

27. On June 23, 1988, the Board, through its counsel,

informed counsel for some of the plaintiffs in writing that

the new school would accommodate students currently

enrolled in the Idalia School and the "surrounding area"

and that the attendance zone for the new school "could"

A-13

include students from Lincoln Elementary and the Train

ing School. The Board, through its counsel, reported that

it had no plans to change the use of the Jonesview Ele

mentary School. No evidence was presented to the court

which sheds light on this incorrect information in such

correspondence.

28. With respect to the May 1988 request for state

facilities surveys referenced in paragraph 35 of the Stipu

lated Facts, the Board, through its counsel, informed

counsel for plaintiffs that when the Board received the

facilities reports, a copy would be made available.

29. This proposed fact has not been established.

30. Significant numbers of white students who re

side within the Talladega County Training School zone

attend public schools in the Talladega City School system.

This has occurred for many years and occurred long

before the March 13, 1985 "unitary" order.

31. Dr. Grissett has not contacted school officials of

the Talladega City School system in an effort to stop it

from accepting into its system children who reside in the

Talladega County Training School zone.

32. This proposed fact has not been established.

33. On April 19, 1979, the Justice Department noti

fied counsel who represented both the Talladega City

Board of Education and the Talladega County Board of

Education that the Talladega City School system was

governed by a provision in its school desegregation order

that it should not consent to transfers where the cumula

tive effect would reduce desegregation in either district.

A-14

34. As required by state law, defendants have trans

ferred school records of students leaving the Talladega

County School system after they have enrolled in the

Talladega City School system.

35. The Talladega County School system does not

have a written policy regarding verification of residences

of students seeking to enroll in County schools. It does

seek to verify the residences of students in its system

transferring to another school in its system.

36. Defendants are aware of zone-jumping by white

and black students alike. Many of the white students are

likely avoiding historically black Talladega County Train

ing School. One of the objectives in building the new

Stemley Bridge Road Elementary School was to discour

age such zone-jumping; another of such objectives was to

foster and promote integration of children in the three

affected zones.

37. This proposed fact has not been established.

38. If there is any significant zone-jumping within

the County system by students avoiding the Training

School, no evidence sufficient to reach that conclusion

has been presented. 39 40

39. The Board of Education provides transportation

to students who attend school in the County system and

it is possible for some students to use that transportation

to attend an incorrect school.

40. The Talladega County Board of Education may

have received an inquiry in 1984 by the Justice Depart

ment regarding possible zone-jumping by students avoid

ing historically black Hannah Mallory School and the

A-15

Talladega County Training School. The extent of any such

zone-jumping in 1984 is not known.

41. About ten years ago, when a portion of the

Talladega County school district was sought to be

annexed by a school system in another county, the Board

took steps in Lee v. Macon County to stop the annexation.

The area sought to be annexed contained mostly white

students and both the school systems involved were

under court ordered integration. The Board has taken

few, if any, steps to stop the loss of white students to the

separate school systems operated by the City of Talladega

or the City of Sylacauga from predominately and histori

cally black Talladega County Training School.

42. The Talladega County Board's policy authorized

majority-to-minority transfers.

43. The Talladega County Board has not advertized

[sic] the availability of the majority-to-minority transfer

option.

44. One of the members of the Talladega County

Board was recently asked and did not know what a

majority-to-minority transfer is.

Facts to be offered by proffer

The document filed August 11, 1989 contain 10 para

graphs setting forth "facts" which counsel contemplated

would be offered to the court by a proffer. No proffer was

made during the trial and that section of the August 11,

1989 document will not be addressed by the court.

A-l 6

Defendants' proposed factual findings

In 24 separately numbered paragraphs counsel for

defendants presented to the court proposed factual find

ings. The court will now set forth, using the same para

graph numbers, some of its findings of fact and

conclusions of law germane to each proposed factual

finding. The failure to include the language or the "facts"

as proposed by counsel for defendants could generally be

viewed as a determination by the court that the proposed

language or "facts" have not been established or are

embraced in other findings or conclusions found else

where in this document.

1. Plaintiffs have failed to establish their entitle

ment to prevail or obtain relief under any of the claims

they have made in their complaint.

2. There has been no significant or material change

in the percentage of white and non-white students

attending schools operated by the Talladega County

Board of Education during the past 15 years.

3. The Talladega County schools were under the

supervision of the United States District Court from 1970

until March 13, 1985.

4. The Talladega County Board of Education was

dismissed from the Lee v. Macon County litigation on

March 13, 1985 by consent, the court expressly conclud

ing that the system had achieved a unitary status.

5. The closing of Jonesview School, the elimination

of grades K-6 at Talladega County Training School, and

the consolidation of all those students with students in

A-l 7

the Idalia zone at a new facility under construction adja

cent to and on the north side of the old Idalia site is

consistent with the operation of a unitary, racially non-

discriminatory public school system. The anticipated

zones for the students when they reach grades 7-12 are

also consistent with such an operation.

6. The decision to build the new Stemley Bridge

Road Elementary School now under construction has not

been shown to have been racially motivated. Its construc

tion will provide better educational opportunities for all

of the children it serves. Construction of the new Stemley

Bridge School will enhance desegregation of grades K-6

at the present Talladega County Training School, since it

will take students who are now in an environment about

99% black and change that ratio to about 70-75% black.

7. The Board was reasonable in assuming that the

Lawson family which owns much of the land around the

present site of the Talladega County Training School

likely would not sell land to the Board. At one point in

the past, the patriarch of the family is reputed to have

told a former Board member that he would "freeze in

hell" before he would sell another piece of land to the

County. Regardless of whether land might have been

available at the Talladega County Training School site, the

Board made a sound decision from an educational view

point not to locate the new elementary school at the site

of a middle school/high school. This decision did not

have a racially discriminatory animus and did not have a

disparate impact on blacks.

8. The plaintiffs have not shown that the location of

the new Stemley Bridge Road School was racially moti

vated or effected a disparate impact on blacks.

A-18

9. Talladega County Training School is not sched

uled for closing, but is scheduled for substantial renova

tion and upgrading so that it may serve as an expanded

grades 7-12 school. The capital outlay for the improve

ments will equal or exceed $500,000.

10. The Talladega Board of Education neither

"allows" nor "condones" out-of-zone attendance, or

zone-jumping" by a child residing within its system but

attending a public school outside its system. The Board

has a significant financial interest in discouraging such

zone-jumping. The Board also has a general policy

against a child zoned for one of its schools attending one

of the Board's schools out of his/her zone, but it has two

reasonable exceptions to this policy, viz., children of

employees of the Board may attend in the zone of a

parent's employment and children in need of special

education may attend out-of-zone. No evidence even sug

gests that these exceptions are abused or applied along

racial lines, and it is clear the Board takes steps calculated

fo assure that a child in its system attends the proper

school. Talladega County School personnel have been

aware for quite some time that students of both races, but

primarily white students, who are zoned for Talladega

County schools such as Talladega County Training School

are attending schools in the Talladega City system and

the Sylacauga City system. Talladega County school per

sonnel are, as a practical matter, unable to prevent this,

since the enrollment and attendance of a public school

student is verified and determined by the gaining school

system (i.e„ the city school system) and not by the losing

school system (in this case, Talladega County). Talladega

County loses approximately $2,000 to $3,000 (depending

A-19

upon the year) of state education money per child per

year for every county" student who attends a "city"

system school.

11. Talladega County school personnel have previ

ously attempted to bring the problem discussed in para

graph 10 above to the attention of the Federal Bureau of

Investigation and the United States Justice Department,

but nothing has happened.

12. Only one historically black school (Hannah Mal

lory) has been closed since 1970. One historically white

school (Eastoboga) has also been closed during that

period and another historically white school (Jonesview)

is currently in the process of being closed.

13. At the end of the 1987-88 school year, the Phyllis

Wheatley School, with the support of some members of

the local black community and over the objections of

other members of the local black community, was relo

cated to a new site about one mile away. The relocation of

Phyllis Wheatley School did not change the bus route,

faculty, or student composition in any way. The name of

the school was changed to Childersburg Middle School.

14. In 1985 Hannah Mallory was the only remaining

one-race school in Talladega County. It had been allowed

to remain that way during the entire time the school

system was operating under its Lee v. Macon County inte

gration order primarily because of the school's geograph

ical location and the difficulty of integrating it.

15. The trend in modern public education is to con

solidate smaller "neighborhood" schools into larger ones

with more diverse student bodies and better facilities.

A-20

The new Stemley Bridge Road School is in line with this

. end, and it will make modern, up-to-date facilities

available to a large number of children in grades K-6. Its

student body will be 70-75% black.

16. There were two principal logistical problems

with locating the new larger elementary school at the site

of Talladega County Training School: (1) adequate land

consisting of a minimum of 15 acres was not readily

available, and (2) the Board needed the existing space at

Talladega County Training School embracing about 55,000

square feet for its planned upgrade of that school and the

enhanced grades 7-12 program it now has planned. The

Board also had a strong desire not to locate the large,

consolidated elementary school at the site of a middle

school or a high school.

17. The new Talladega County Training School

building program will include an up-to-date library, a

media center embracing a computer lab, and the addition

of adequate science laboratory space. It will also include

greatly expanded home economics and industrial arts

programs and facilities. The remodeling program also

includes substantial physical improvements, such as re

wiring, re-lighting, replacement of all windows and

doors, etc. 18

18. By expanding and upgrading the facilities at

Talladega County Training School to enhance the educa

tion offered to grades 7-12 there, the Board hopes to be

able to improve its course offerings and attract and retain

more white students to improve racial balance at Tal

ladega County Training School. Regardless of how effec

tive this upgrade is in attracting more students to that

A-21

school who are now going to private schools or to adjoin

ing public systems, the planned renovation at Talladega

County Training School will unquestionably improve the

quality of education for students now attending there.

19. The Talladega County Board of Education has

moved forward to improve the quality of education

offered to all of its students since March 13, 1985. In so

doing there is no evidence which can support a conclu

sion that race impermissibly was considered in the deci

sion-making process. There was no discriminatory

animus behind the plans and decisions challenged in this

case and it is clear that the challenged plans and deci

sions have had no disparate impact on blacks.

20. It is clear to the court that over the years the

Board has delayed providing to the public, black and

white alike, information with regard to developments

under consideration by the Board, but there is no evi

dence that this has been done in a racially discriminatory

manner or with a racial animus. The Board has not

refused to receive comments or input from plaintiffs at

Board meetings or otherwise.

21. Mr. Elston wrote a total of three or four letters to

Talladega County school personnel, but all of those letters

were vague and he never made any follow up about what

his "concerns" were. In all but one instance the Board

properly responded to such letters. The court is partic

ularly impressed with the restrained response (Plaintiffs'

Exhibit 4) to one of such letters (Plaintiffs' Exhibit 5).

Neither Mr. Elston nor any other plaintiff who attended a

Board meeting asked to speak to the Board meeting about

A-22

any of the “concerns" which they have raised in the

complaint.

22. The extent of the "zone-jumping" in which Tal

ladega County students are attending Talladega City or

Sylacauga City schools is not known, but it involves a

significant number of students, most of which are white

but some of which are black. Any such jumping does not

appear to have changed significantly over the years the

racial composition of the students in the Talladega

County system or the Talladega City system. Talladega

County system enrollment has remained about constant

at 43% black and Talladega City system enrollment has

moved in recent years from 40% black to 43% black

notwithstanding the City's receipt of students who reside

outside the City. Many of the students who are or have

been attending Sylacauga City Schools have done so

oi.Ucr "temporary guardianship" or similar court orders

which could well have been devices to permit their atten

dance at Sylacauga City Schools. There is no evidence

that the orders are fake and it seems that each such order

was signed by a state court judge with appropriate juris

diction. With regard to each of these "receiving" systems,

the Talladega County Board has few, if any, avenues

available to it to stop this drain from its system other

than to discourage it by improvements to its system, such

as the improvements out of which this suit arose. Cer

tainly it is clear that the Board would like to stop the

zone-jumping. The Board is in no way intending to dis

criminate against plaintiffs on the basis of race or to deny

plaintiffs equal protection by not being more "creative" in

finding a way to prevent such zone-jumping.

A-23

23. The Talladega County School System has not

notified parents of children going out of zone" to

another public school system that their actions are

improper. Defendants' view that it has no legal right or

duty to do so is a sincere view with a reasonable basis to

support it. Transferring school records, in accordance

with state law requirements, of students leaving the

County system for the City system does not make the

defendants accountable for the conduct of the parents

and the receiving school officials. Any "zone-jumping"

among or between zones in the County school system is

very limited, not authorized by the defendants, includes

black as well as white students, and is largely corrected

through the Board's policy of requiring the receiving

principal to investigate transfers within the County's sys

tem.

24. One of the purposes, and hopefully one of the

results of the upgrading and enhancement of Talladega

County Training School grades 7-12 is to stop the loss of

white students by providing attractive physical facilities

and curriculum changes at Talladega County Training

School.

Summary

In this case plaintiffs have endeavored to establish

that several decisions and practices of defendants violate

or violated (a) the Equal Protection Clause of the Four

teenth Amendment, (b) Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of

1964, 42 U.S.C. § 2000d, et seq., and (c) regulations pro

mulgated to effectuate Title VI, 34 C.F.R. §100 et seq., and

particularly 34 C.F.R. § 100.3. They have failed in this

A-24

endeavor. Wilh regard to all such claims, plaintiffs have

a.led to establish by a preponderance of the evidence

hat any of the challenged decisions and practices were

■nted by a racially discriminatory animus. A discrimi

natory intent being a prerequisite to recovery under the

constitutional claim and the statutory claim, defendants

are en ,tied to a judgment in their favor on these claims.

Also, to the extent that plaintiffs sought to prevail on

disparate treatment theories under their claims predicated

on regu|atlons lo ef/ec,uate Ti,|e Vl_ defendanls arc en[._

, to a judgment in their favor. With regard to the

claims based on disparate impact theories under the regu-

Is't'ahT h i effeC,Ua' e T‘tle VI' P’aln,iffS have faiI«* establish by a preponderance of the evidence that any of

e c a enged decisions and practices violated the regu-

_ ions or otherwise had a disparate impact on blacks.

hus plamtiffs have not established even a prima facie

case under the regulations. Even though defendants had

no burden of proof, they have articulated and established

by clear and convincing evidence substantial, legitimate

non-d,scriminatory reasons for the decisions and prac-

tices in question. Since the court has earlier held that the

decisions and practices of defendants did not result in a

isparate impact on plaintiffs, it goes without saying that

plaintiffs also failed to establish an alternative to the

chal enged decisions and practices which alternative

would have resulted in less of a disparate impact.

A separate final judgment in favor of defendants will

he entered.

A-25

DONE this 19th day of September, 1989.

/s/ James H. Hancock

UNITED STATES DISTRICT

JUDGE

A-26

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF ALABAMA

EASTERN DIVISION

QUINTIN ELSTON, ET AL„ )

PLAINTIFFS, }

VS. )

TALLADEGA COUNTY BOARD J

OF EDUCATION, ET AL„ j

DEFENDANTS. )

CV88-H-2052-E

Filed

Sep 19, 1989

FINAL JUDGMENT

In accordance with the findings of fact and conclu

sions of law this day entered, it is hereby ORDERED,

ADJUDGED and DECREED that judgment in favor of

defendants is ENTERED. Costs are taxed against plain

tiffs.

DONE this 19th day of September, 1989.

/s/ James H. Hancock

UNITED STATES

DISTRICT JUDGE

A-27

APPENDIX 3

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE ELEVENTH CIRCUIT

No. 89-7777

QUINTIN ELSTON; RHONDA

ELSTON; and TIFFANIE ELSTON, all

minor children, by and through their

parents and guardians, AUGUSTUS

ELSTON, and CARDELLA ELSTON;

on behalf of themselves and all other

similarly situated black children and

parents or guardians of black

children in Talladega County in the

State of Alabama, etc., et al.,

Plain tiffs-Appel lan ts,

versus

TALLADEGA COUNTY BOARD OF

EDUCATION; LANCE GRISSETT;

DAN LIMBAUGH, M. R. WATSON;

GAY LANGLEY; AND LARRY

MORRIS and BEULAH BARRETT;

JOSEPH POMEROY,

Defendants-Appellees,

Defendant.

A-28

No. 89-7917

TORRANCE BECK, a/k/a

Albert Beck, Jr.,

Plaintiff,

QUINTIN ELSTON, RHONDA

ELSTON, and TIFFANIE ELSTON, all

minor children, by and through their

parents and guardians, AUGUSTUS

ELSTON and CARDELLA ELSTON;

on behalf of themselves and all other

similarly situated black children in

Talladega County in the State of

Alabama,

Plain tiffs-Appellants,

versus

TALLEDEGA COUNTY BOARD OF

EDUCATION; LANCE GRISSETT;

DAN LIMBAUGH; M. R. WATSON;

GAY LANGLEY; LARRY MORRIS;

and BEULAH GARRETT,

Defendants-Appellees.

Filed June 7, 1991

Appeals from the United States District

Court for the Northern District of Alabama

ON PETITION(S) FOR REHEARING

BEFORE: TJOFLAT, Chief Judge, DUBINA, Circuit

Judge, and HENDERSON, Senior Circuit

Judge.

1

A-29

PER CURIAM:

The petition(s) for rehearing filed by appellant's is

denied.

ENTERED FOR THE COURT:

I s / Joel F. Dubina

UNITED STATES CIRCUIT JUDGE

A-30

APPENDIX 4

♦ X- X-

715, 725-26 (1966).

V. THE DISTRICT COURT ABUSED ITS DISCRETION

IN REFUSING TO JOIN THE TALLADEGA CITY

BOARD OF EDUCATION AS A PARTY

After learning in depositions in early May that inter

district transfers to the Talladega City schools were sig

nificant and documented and that the County School

Board relied exclusively on an argument that it was

beyond their power to prevent County students from

attending the City schools, plaintiffs moved on May 25,

1989 to join the City Board as a party in the litigation

(Rl-62). Defendants did not object.

The district court denied the motion solely because it

was beyond the May 5 deadline that the court set direct

ing that the "parties to the litigation . . . shall be reflected

by the pleadings on file" on May 5, 1989 (Rl-63).

Plaintiffs contend that the court abused its discretion

here by exercising it in a manner directly contradictory to

Fed. R. Civ. P. 21, which specifically permits a party to be

dropped or added "at any stage of the action." Fed. R.

Civ. P. 21.71 A request to add parties is generally denied

when it is so late in the litigation that it will delay the

71 Parties have been added on appeal, Reed v. Robilio, 376

L2d 392 (6th Cir. 1967), after trial, Rcichcnberg v. Nelson, 310 F.

upp. 248 (D. Neb. 1970), and in the Supreme Court, Rogers v.

0952)382 ^ ̂ 105 1̂965 ;̂ Mullaney v■ ^derson, 342 U.S. 415

A-31

case or prejudice any of the parties to the action, Wright,

Miller & Kane, Federal Practice & Procedure, § 1688 at

467-69 (1986); however, that was not the case here.

Here the date was arbitrarily set at the outset of the

litigation; defendants did not object to the addition or

claim prejudice; the request was only 20 days after the

Court deadline; discovery was ongoing and not com

pleted until shortly before trial in August; all the discov

ery necessary with respect to Talladega City was also

necessary for the claim against the County and was taken

anyway. Courts routinely add surrounding school dis

tricts in interdistrict transfer cases.77 Substantial case law

supports joining parties to existing litigation where the

party sought to be joined could frustrate or interfere with

the relief granted by the court.72 73

Wrongly refusing to add the City Board of Education

as a party also caused the district court to err in ordering

plaintiffs to pay hourly fees and costs to the City on the

grounds that "a non-party should not bear such cost."

72 See United States v. Lowndes County, 878 F.2d at 1302

(after the government's investigation revealed a network of

interdistrict transfers Montgomery, Pike, Coffe, Covington,

Conecuh, and Wilcox Counties and Elba City were later added

as defendants for the limited purpose of considering inter

district transfers); Robinson v. Alabama State Department of Edu

cation, Civ. No. 86-T-569-N (M.D. Ala. Order of Aug. 3, 1987)

(adding surrounding school districts as parties defendant on

the issue of interdistrict transfers).

73 Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Educ., Civ. No.

1974 (D.N.C. Order of Feb. 25, 1970) (See appendix at 52, North

Carolina State Ed. of Educ. v. Swann, 402 U.S. 43 (1971)); Ben

jamin v. Malcolm, 803 F.2d 46, 53 (2d Cir. 1986); Bradley v. School

Bd. of City of Richmond, 51 F.R.D. 139, 143 (E.D.Va. 1970).

A-32

(Rl-68.) Further, with respect to the $5,188 awarded, it is

impossible to determine how many hours were spent, by whom,

or what hourly rate is claimed. (Rl-92; Rl-91.) In these

circumstances, it was an abuse of discretion for the court

to order plaintiffs to pay $5,188 to the City Board.

V. THE DISTRICT COURT ABUSED ITS DISCRETION

IN DENYING ADMISSION PRO HAC VICE TO

PLAINTIFFS' COUNSEL

The district court abused its discretion in denying

admission pro hac vice to two of plaintiffs' attorneys from

the NAACP Legal Defense Fund on the ground that it

would place an undue burden on the taxpayers if plain

tiffs won (Rl-20). First, the district court awards attor

neys' fees and in its discretion can eliminate any requests

that are duplicative or excessive and can set appropriate

hourly rates. But, more importantly, this Court has ruled

that "civil rights litigants may not be charged with selec

ting the nearest and cheapest attorney."74 While plaintiffs

do have well qualified local counsel, the court did not

consider the arrangements between local counsel and

LDF for sharing the work-load, nor plaintiffs' interest in

having lawyers with special expertise in school deseg

regation cases. The district court's ruling was improper

and an abuse of discretion.75

74 Johnson v. University College of the University of Alabama,

706 F.2d 1205, 1208 (11 h Cir. 1983) (quoting Dowdell v. City of

Apopka, Florida, 689 F.2d 1181, 1188 (11th Cir. 1983).

75 See Sanders v. Russell, 401 F.2d 241 (5th Cir. 1968).

A-33

Conclusion

For the foregoing reasons, plaintiffs respectfully

request that each of the district court's rulings challenged

above be reversed and that the case be remanded for

consideration of Counts I, IV, and V.

Respectfully submitted,

Janell M. Byrd

CLEOPHUS THOMAS, JR.

P.O. Box 2303

Anniston, AL 36202

(205) 236-1240

JANELL M. BYRD

1275 K Steet, N.W., #301

Washington, D.C. 20005

(202) 682-1300

Counsel for Plaintiffs-Appellants

/s/

JULIUS L. CHAMBERS

NORMAN J. CHACHKIN

99 Hudson Street, 16th FI.

New York, New York 10013

(212) 219-1900