Compromise and Settlement Agreement with Escambia County Defendants

Public Court Documents

December 2, 1986

4 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Dillard v. Crenshaw County Hardbacks. Compromise and Settlement Agreement with Escambia County Defendants, 1986. fabe68da-b7d8-ef11-a730-7c1e5247dfc0. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/7df58638-b65c-4feb-b909-f4435ab635ba/compromise-and-settlement-agreement-with-escambia-county-defendants. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE

MIDDLE DISTRICT OF ALABAMA

NORTHERN DIVISION

JOHN: DILLARD, ET AlL.,

Plaintiffs,

VS. CIVIL ACTION NO. 85-T7-1332-N

CRENSHAW COUNTY, ALABAMA,

ET AL.,

(

S

U

S

U

L

S

U

I

U

X

R

R

S

S

L

G

l

SR

Y}

S

y

G

y

Defendants.

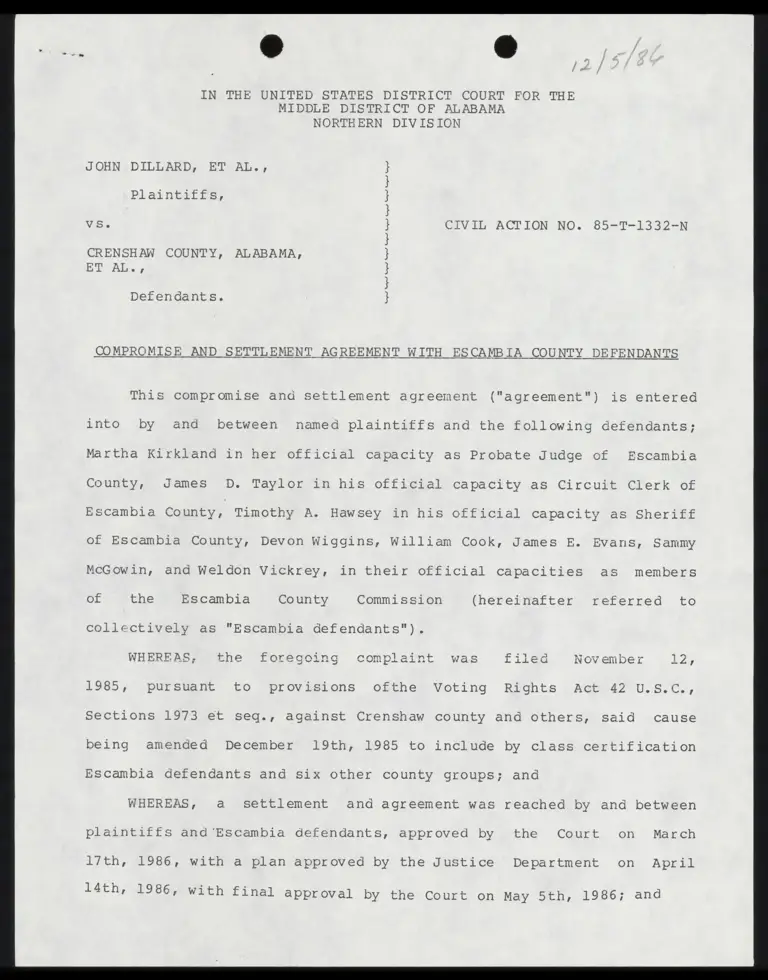

COMPROMISE AND SETTLEMENT AGREEMENT WITH ESCAMBIA COUNTY DEFENDANTS

This compromise and settlement agreement ("agreement") is entered

into by and between named plaintiffs and the following defendants;

Martha Kirkland in her official capacity as Probate Judge of Escambia

County, James D. Taylor in his official capacity as Circuit Clerk of

Escambia County, Timothy A. Hawsey in his official capacity as Sheriff

of Escambia County, Devon Wiggins, William Cook, James E. Evans, Sammy

McGowin, and Weldon Vickrey, in their official capacities as members

of the Escambia County Commission (hereinafter referred to

collectively as "Escambia defendants").

WHEREAS; the foregoing complaint was filed November 12,

1985, pursuant to provisions ofthe Voting Rights Act 42 U.S8.C.,

Sections 1973 et seq., against Crenshaw county and others, said cause

being amended December 19th, 1985 to include by class certification

Escambia defendants and six other county groups; and

WHEREAS, a settlement and agreement was reached by and between

plaintiffs and ‘Escambia defendants, approved by the Court on March

17th, 1986, with a plan approved by the Justice Department on April

l4th, 1986, with final approval by the Court on May 5th, 1986; and

WHEREAS, plaintiffs did thereafter continue with the said cause

against other counties and defendants resulting in final orders

against dineiiitne counties being entered by the Court, and

WHEREAS, plaintiffs filed a motion for award of attorney fees and

expenses with the Court on or about November 20th, 1986; and

WHEREAS, plaintiffs and Escambia defendants have agreed to settle

their differences as to attorney fees and expenses pro tanto reserving

all right of plaintiffs tO proceed with thelr motion against all

remaining parties to this cause of action.

NOW THEREFORE, in consideration of the promises and agreements of

the. parties, each to the . other as. set forth in this pro tanto

settlement, it is hereby agreed as follows:

1. Escambia County defendants shall pay to plaintiffs the sum of

$15,000.00 for attorney fees and expenses incurred to this date.

2. Plaintiffs do hereby for themselves, their heirs, executors,

administrators and assigns, release, acquit, and discharge Escambia

defendants, their successors and assigns from any and all claims, for

attorney fees, «costs or «court and expenses, arising out of or

connected with the matters and occurrences made the basis of this

cause of action to date, provided, however, that this release does not

nor is it intended to operate as a release or discharge for the

liability of any other party.

3. Plaintiffs specifically reserve the right to pursue said

action against all other defendants to this cause or any other person

or entity other than Escambia defendants which may be liable to them

for such fees, costs or expenses and to seek to recover therefrom the

full amounts claimed.

ENTERED this the = day of wevembery 1986.

Ye Vem

Zatry JI. Menefee |

Attor for Bee tra

BLACKSHER, MENEFEE & STEIN

405 Van Antwerp Building

P.O. Box 1051

Mobile, Alabama 36633

SF yl

/ 7

ot ip

James W. Webb ¢

Attorney for Escambia Defendants

WEBB, CRUMPTON & MCGREGOR

166 Commerce Street

P.O. Box 238

Montgomery, Alabama 36101

(205) 834-3176

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I hereby certify that copies of the foregoing Compromise

and Settlement Agreement have been mailed to Larry T. Menefee,

Esquire, James U. Blacksher, Esquire and Wanda J. Cochran, Esquire,

Blacksher, Menefee & Stein, 405 Van Antwerp Building, P.O. Box 1051,

Mobile, Alabama 36633, Terry G. Davis, Esquire, Seay & Davis, 732

Carter Hill Road, P.O. Box 6125, Montgomery, Alabama 36106, Deborah

Fins, Esquire, and Julius L. Chambers, Esquire, NAACP Legal Defense

Fund, 99 Hudson Street, 16th Floor, New York, New York, 10013, dack

Floyd, Esquire, Floyd, Kenner & Cusimano, 816 Chestnut Street,

Gadsden, Alabama 35999, Alton Turner, Esquire, Turner & Jones, P.O.

Box 207, Luverne, Alabama 36049, D.L. Martin, Esquire, 215 S. Main

Street, Moulton, Alabama 35650, David R. Boyd, Esquire, Balch &

Bingham, P.O. Box 78, Montgomery, Alabama 36101, W.0. Kirk, Jr,

Esquire, Curry & Kirk, Phoenix Avenue Carrollton, Alabama 35447, Barry

D. Vaughn, Esquire, Proctor & Vaughn, 121 N. Norton Avenue, Sy lacauga,

Alabama 35150, H.R. Burnham, Esquire, Burnham, Klinefelter, Halsey,

Jones & Cater, 401 SouthTrust Bank Building, P.O. Box 1618, Anniston,

Alabama 36202, Warren Rowe, Esquire, Rowe, Rowe & Sawyer, P.O. BOX

150, Enterprise, Alabama 36331, Edward Still, Esquire, 714 South 29th

Street, Birmingham, Alabama 35233-2810, Reo Kirkland, Jr., Esquire,

P.O. Box 646, Brewton, Alabama 36427, and all defendants not

represented by counsel by placing copies of the same. in, the United

States Mail, postage prepaid, this the _5 day of fernace 1986.

=7 { ry

<2 (Le Sag

James W. i ~