Loving v. Virginia Brief for Appellants

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1966

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Loving v. Virginia Brief for Appellants, 1966. a27cc5f2-bb9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/7df9e2c1-64de-4b84-ab8a-d18c8bba3b55/loving-v-virginia-brief-for-appellants. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

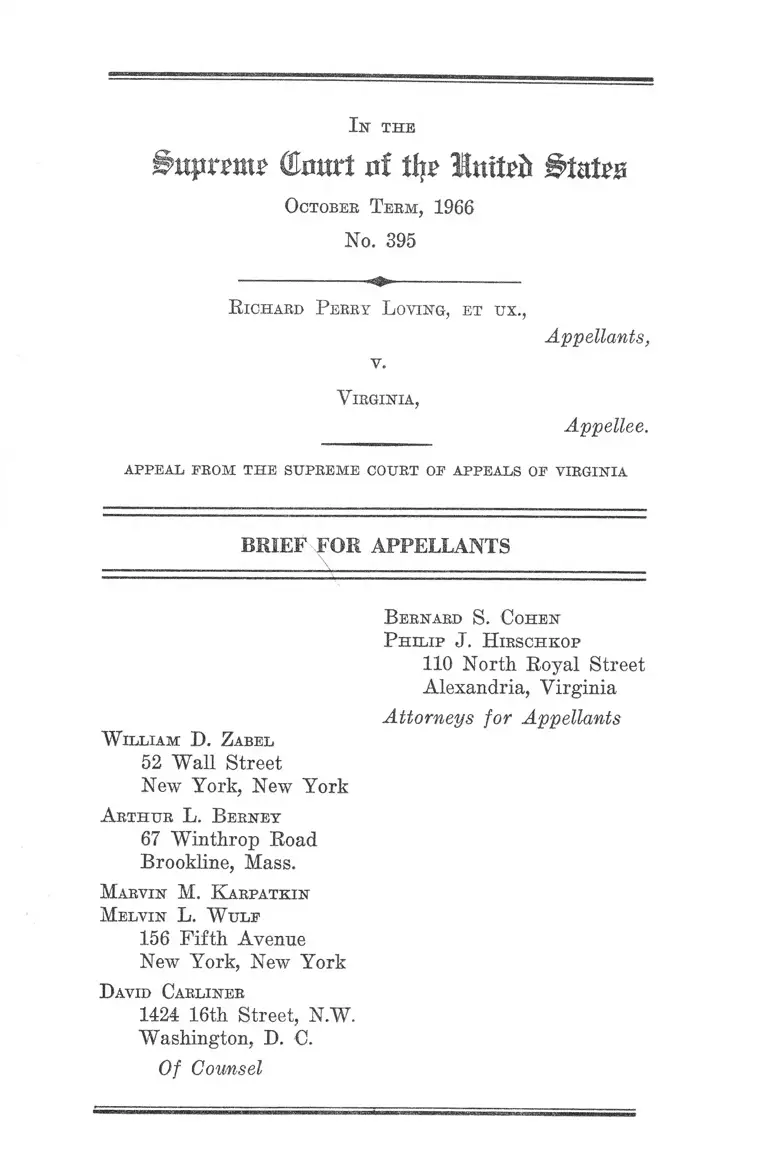

I n the

ûprrrnr Court at % Hmtrft

October Term, 1966

No. 395

R ichard P erry L oving, et ux.,

v.

Appellants,

V irginia,

Appellee.

APPEAL, FROM THE SUPREME COURT OP APPEALS OP VIRGINIA

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

B ernard S. Cohen

P hilip J. H irschkop

110 North Royal Street

Alexandria, Virginia

Attorneys for Appellants

W illiam D. Zabel

52 Wall Street

New York, New York

A rthur L. B erney

67 Winthrop Road

Brookline, Mass.

Marvin M. K arpatkin

Melvin L. W ulp

156 Fifth Avenue

New York, New York

David Carliner

1424 16th Street, N.W.

Washington, D. C.

Of Counsel

I N D E X

Preliminary Statement .................................................... 1

Citation to Opinions Below ............................................. 2

Jurisdiction .................. ........... .......— .........—-............... 2

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved .... 4

Questions Presented ................... 6

Statement of the Case ............ 6

Summary of Argument................................................ ... 8

A rgument :

I. The validity of the entire Virginia statutory

scheme prohibiting interracial marriage is at

issue in this case ............................................. 11

II. The history of the Virginia anti-miscegena

tion laws shows they are relics of slavery

and expressions of racism ............................. 15

Early History .................................. 16

Racial Integrity Act of 1924 .......................... 20

III. Anti-miscegenation laws cause immeasurable

social harm........................................................ 24

IV. The legislative history of the Fourteenth

Amendment does not exempt anti-miscegena

tion laws from its application ...................... 28

PAGE

11

PAGE

Y. The Virginia anti-miscegenation laws are

racially discriminatory and deny appellants

equal protection of the laws .......................... 31

VI. The Virginia anti-miscegenation laws violate

the due process clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment ...................................................... 38

Conclusion .............. ..................................................... ..... 39

T able op A uthorities:

Cases:

Anderson v. Martin, 375 U. S. 399 (1964) ................... 33

Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U. S. 497 (1954) ...................... 39

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483 (1954) .... 10,

25-26, 29, 31, 32

Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S. 60 (1917) ............. . 39

Burton v. Wilmington Parking Authority, 365 U. S.

715 (1961) ..................................................................... 30

Dorsey v. State Athletic Comm., 168 F. Supp. 149

(E. D. La. 1958), aff’d per curiam, 359 TJ. S. 533

(1959) ............................................................................. 33

Greenhow v. James’ Executor, 80 Va. 636 (1885) .......12,13

Griswold v. Connecticut, 381 U. S. 479 (1965) .......3, 38, 39

Hamm v. Virginia State Board of Elections, 230 F.

Supp. 156 (E. D. Va.), aff’d per curiam, 379 U. S. 19

(1964) .................................. 33

Hirabayashi v. TJ. S., 320 TJ. S. 81 (1943) ____ ______ 33

Home Bldg. & Loan Ass’n v. Blaisdell, 290 H. S. 398

(1934) 31

I l l

In re Shun Takahashi’s Estate, 113 Mont. 400, 129

P. 2d 217 (1942) ............ ............................................. 12

Jackson v. City and County of Denver, 109 Colo. 196,

124 P. 2d 240 (1942) ......... ....................................... 32

Kinney v. Commonwealth, 71 Va. 858 (1878) ...........13,14

Largent v. Texas, 318 U. S. 418 (1943) ...................... 3

Meyer v. Nebraska, 262 U. S. 390 (1922) ...................... 38

McLaughlin v. Florida, 379 U. S. 184 (1964) .......14, 29, 32,

33, 34

McPherson v. Commonwealth, 69 Va. 939 (1877) ....... 14

NAACP v. Alabama, 357 U. S. 449 (1958) .................. 39

NAACP v. Button, 371 U. S. 415 (1963) ............ .......... 39

Naim v. Naim, 197 Va. 80, 87 S. E. 2d 749, vacated

and remanded, 350 U. S. 891 (1955), aff’d, 197 Va.

734, 90 S. E. 2d 849, appeal dismissed, 350 U. S.

985 (1956) ..................................... ........................ 11,34,36

Nebbia v. New York, 291 U. S. 502 (1934) .................. 39

Norris v. Alabama, 294 U. S. 587 (1935) ........ 29

Oyama v. California, 332 U. S. 633 (1948) .............. .... 33

Pace v. Alabama, 106 U. S. 583 (1883) ......................29,32

Palko v. Connecticut, 302 U. S. 319 (1937) ____ ___ 38

Perez v. Sharp, 32 Cal. 2d 711, 198 P. 2d 17 (1948)

(sub nom. Perez v. Lippold) ..................................... 38

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1 (1948) .......... ............ . 32

Skinner v. Oklahoma, 316 U. S. 535 (1942) ............... 38

Stevens v. U. S., 146 F. 2d 120 (10th Cir. 1944) ....... 12

Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 IT. S. 303 (1880) ....... 29

PAGE

IV

Takahashi v. Fish & Game Commission, 334 U. S. 410'

(1948) ............................................................................. 33

Toler v. Oakwood Smokeless Coal Corp., 173 Va. 425,

4 S. E. 2d 364 (1939) ................................................ 12

Watson v. City of Memphis, 373 U. S. 526 (1963) ....... 33

Williams v. Bruffy, 96 U. S. 176 (1877) ...................... 3

Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U. S. 356 (1886) .................. 33

United States Constitution:

Fourteenth Amendment ............... passim

Statutes:

28 U. S. C. §1257(2) ............................................... 3

42 U. S. C. § 4 1 6 (h )(l)....... 12

Virginia Code Annotated:

§1-14 (Supp. 1964) .............................................. passim

§18.1-188 (1950) ........................................................ 14

§18.1-193 (1950) ........................................................ 14

§20-50 (1950) ............................................................. 23

§20-53 (1950) ............................................................. 23

§20-54 (1950) .................. ...... ............... passimi

§20-57 (1950) .............................. passim

§20-58 (1950) ..........................................................passim

§20-59 (1950) .......................... passim

§20-60 (1960) ........................................... 18

§2253 (1887)........... 13

PAGE

V

PAGE

2 Laws of Virginia 170 (Hening 1823) ...................... 17

3 Laws of Virginia 86 (Hening 1823) ....................... 17

Virginia Acts of Assembly, 1877-78, eh. VII, § 3 ........... 13

Other Authorities:

Avins, Anti-Miscegenation Laws and the Fourteenth

Amendment: The Original Intent, 52 Va. L. Rev.

1224 (1966) ................................................................... 28

Applebanm, Miscegenation Statutes: A Constitutional

and Social Problem, 53 Geo. L. J. 49 (1965) ....31-32, 38

Bickel, The Least Dangerous Branch (1962) .............. 32

Bickel, The Original Understanding and the Segre

gation Decision, 69 Harv. L. Rev. 1 (1956) ........... 30

Black, The Lawfulness of the Segregation Decisions,

69 Yale L. J. 421 (1960) ............................................. 31

Bloch, Miscegenation, Melaleukation and Mr. Lincoln’s

Dog (Schaum Publ. Co., N. Y. 1958) ...................... 2

Bruce, Economic History of Virginia in the Seven

teenth Century (MacMillan & Co. 1896) .......... 16,17,18

Cash, The Mind of the South (1941) ......................... 24,25

Cox, The South’s Part in Mongrelizing the Nation

(White America Society, Richmond 1926) .............. 23

Cox, White America (White America Society, Rich

mond 1923) ............................. ..................................... 20

Cummins & Kane, Miscegenation, The Constitution

and Science, 38 Dicta 24 (1961) 37

V I

Fried, A Four-Letter Word That Hurts (Saturday

PAGE

Review, October 2, 1965) ............................................ 35

Greenberg, Race Relations and American Law 348

(1959) .................................. .......................................... 12

Journal of the Senate of the Commonwealth of Vir

ginia (Supt. of Public Printing, Richmond 1924) .... 21

Kaplan, Miscegenation Issue in the Election of 1864,

XXXIV Journal of Negro History 277 (July, 1949) 2

Kelly, Clio and the Court: An Illicit Love Affair, 1965

Sup. Ct. Rev. 119 ........................................................ 30

Letter to the Editor From Members of the Dept, of

Anthropology of Columbia University, New York

Times, December 15, 1964 ......................................... 37

Montagu, Man’s Most Dangerous Myth: The Fallacy

of Race (4th ed. 1964) ................................................ 35

Myrdal, An American Dilemma (1962) ______24,25,26,27

Pettigrew, A Profile of the Negro American (1964) ....24, 25

Pittman, The Fourteenth Amendment : Its Intended

Effect on Anti-Miscegenation Laws, 43 N. C. L. Rev.

92 (1964) ........................................................... 28

Restatement, Conflict of Laws §§133-134 (1934) ......... 13

Restatement (Second), Conflict of Laws §132 (Ten.

Draft No. 4-1957) ....................... 13

Reuter, The American Race Problem: A Study of the

Negro (Revised ed., Thos. Y. Crowell Co., N. Y.

1938) .................................................. 16,17,20

V II

Richmond Times Dispatch, February 17, 1924, p. 6 .... 21

Richmond Times Dispatch, February 13, 1924, p. 1 .... 22

Seidelson, Miscegenation Statutes and the Supreme

Court: A Brief Prediction of What the Court Will

Do and Why, Catholic U. L. Rev. 156 (1966) ....... 12

Shapiro, Race Mixture (UNESCO 1965) ...................... 37

Smith, Killers of the Dream (1961 ed.) .................. 25,26

Taintor, Marriage in the Conflict of Laws, 9 Yand.

L. Rev. 607 (1956) ........................................................13-14

The Race Question and Modern Science: The State

ment of the Nature of Race and Race Differences,

Article 7 (UNESCO 1952) ......................................... 37

United Nations Universal Declaration of Human

Rights, Article 16.1 ...................................................... 38

Wadlington, The Loving Case: Virginia’s Anti-

Miscegenation Statute in Historical Perspective, 52

Va. L. Rev. 1189 (1966) ........................... ..... 15,17,19,22

Wechsler, Toward Neutral Principles of Constitutional

Law, 73 Harv. L. Rev. 1 (1959) ................................. 30, 32

Weinberger, A Reappraisal of the Constitutionality of

Miscegenation Statutes, 42 Cornell L. Q. 208 (1957) .. 35

PAGE

In THE

(Etmrt af X\\t lluttub States

October T erm, 1966

No. 395

R ichard P erry L oving, et ttx.,

Appellants,

v.

V irginia,

Appellee.

ON APPEAL FROM THE SUPREME COURT OF APPEALS OF VIRGINIA

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

Preliminary Statement

This important case presents the question whether the

United States Constitution invalidates those laws of Vir

ginia which prohibit and penalize the marriage of a man

and a woman and their subsequent living together simply

because one of the couple is Negro and the other is white.

It gives this Court an appropriate opportunity to strike

down the last remnants of legalized slavery in our coun

try—the anti-miscegenation laws of Virginia and sixteen

other states which ban Negro-white marriages. This Court

has never ruled on the constitutionality of the anti-misce

2

genation laws. No other civilized country in the world has

such laws except the Union of South Africa.

Citation to Opinions Below

The opinion of the Circuit Court of Caroline County,

Virginia (R. 8) is not officially reported. The opinion of

the Supreme Court of Appeals of Virginia is reported at

206 Va. 924, 147 S. E. 2d 78 (1966) (R. 19-27).

Jurisdiction

On January 6, 1959, appellants, who were represented

by counsel, pleaded guilty and were convicted in the Circuit

Court of Caroline County of violating Virginia’s anti

miscegenation* statutes. The specific charge in the indict

ment (R. 5-6) was that they left Virginia and contracted a

miscegenetic marriage in the District of Columbia with

the intention of returning to and actually returning and

cohabiting as man and wife in Virginia in violation of

Va. Code § 20-58. They were each sentenced to one year

in jail but their sentences were suspended by Judge Leon

M. Bazile for a period of twenty-five years, upon the con

dition that they immediately leave Caroline County and

the State of Virginia and not return together or at the

* The term “miscegenation” , derived from the Latin “miscere”

(to mix) and “genus” (race), was coined in an anonymously pub

lished political pamphlet, “ Miscegenation: The Theory of the

Blending of the Races, Applied to the American White Man and

Negro” . It was written by Democrats David Goodman Croly and

George Wakeman, primarily in order to use the race issue in the

1864 Presidential election by attributing the pamphlet’s favorable

views on racial intermixing to the Republicans. Bloch, Miscegena

tion, Melaleukation and Me. L incoln’s Dog 37-42 (Schaum Publ.

Co., N. Y. 1958); S. Kaplan, “Miscegenation Issue in the Election of

1864” , X X X IV Journal of Negro History 277 (July, 1949).

3

same time to the county or state for twenty-five years

(R. 6).

On November 6, 1963, appellants filed a Motion to Vacate

Judgment and Set Aside Sentence (R. 7) in the Circuit

Court of Caroline County which was denied by an Order

of Judge Bazile on January 22, 1965 (R. 17).

Appellants then appealed to the Supreme Court of Ap

peals of Virginia which heard the case on the merits. On

March 7, 1966, the Supreme Court of Appeals of Virginia

affirmed the convictions of appellants, set aside their sen

tences,* and remanded for further sentencing not incon

sistent with its opinion (R. 28). However, on March 28,

1966, the Supreme Court of Appeals of Virginia issued an

Order staying execution of its judgment of March 7, 1966,

so that appellants “may have reasonable time and opportu

nity to present to the Supreme Court of the United States

a petition for appeal to review the judgment of this Court”

(R. 28) (Omitted in printing).

Notice of Appeal to the Supreme Court of the United

States was filed in the Supreme Court of Appeals of Vir

ginia on May 31, 1966 (R. 29). Jurisdiction of this Court

rests upon 28 U. S. C. § 1257 (2). Williams v. Bruffy, 96

U. S. 176 (1877); Largent v. Texas, 318 U. S. 418 (1943);

Griswold v. Connecticut, 381 U. S. 479 (1965). Probable

jurisdiction was noted December 12, 1966 (R. 32).

* The highest Virginia court held that the condition imposed by

Judge Bazile in suspending the sentences was unreasonable since

cohabitation in Virginia by the Lovings, as man and wife, which

the highest Virginia court termed “the real gravamen of the offense

charged” against them, could be prohibited without preventing ap

pellants from returning together to the State.

4

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved

1. Petitioners were convicted of violating V a. Code A nn .

§20-58 (1950) (Vol. 4, p. 491), which provides:

§ 20-58. Leaving State to evade law.—If any white

person and colored person shall go out of this State,

for the purpose of being married, and with the inten

tion of returning, and be married out of it, and after

wards return to and reside in it, cohabiting as man

and wife, they shall be punished as provided in § 20-59,

and the marriage shall be governed by the same law

as if it had been solemnized in this State. The fact

of their cohabitation here as man and wife shall be

evidence of their marriage.

2. This case also involves:

(i) V a. Code A n n . § 20-59 (1950) (Yol. 4, p. 492), which

provides:

§ 20-59. Punishment for marriage.—If any white per

son intermarry with a colored person, or any colored

person intermarry with a white person, he shall be

guilty of a felony and shall be punished by confine

ment in the penitentiary for not less than one nor

more than five years.

(ii) Va. Code A n n . § 20-57 (1950) (Vol. 4, p. 491), which

provides:

§ 20-57. Marriages void without decree.—All mar

riages between a white person and a colored person

shall be absolutely void without any decree of divorce

or other legal process.

0

(iii) Va. Code A nn . § 20-54 (1950) (Yol. 4, p. 489), which

provides:

§ 20-54. Intermarriage prohibited; meaning of term

‘white persons’—It shall hereafter be unlawful for any

white person in this State to marry any save a white

person, or a person with no other admixture of blood

than white and American Indian. For the purpose of

this chapter, the term ‘white person’ shall apply only

to such person as has no trace whatever of any blood

other than Caucasian; but persons who have one-

sixteenth or less of the blood of the American Indian

and have no other non-Caucasic blood shall be deemed

to be white persons. All laws heretofore passed and

now in effect regarding the intermarriage of white

and colored persons shall apply to marriages pro

hibited by this chapter.

(iv) Va. Code A n n . §1-14 (Supp. 1964) (Yol. 1, p. 12),

which provides:

§ 1-14. Colored persons and Indians defined.—Every

person in whom there is ascertainable any Negro blood

shall be deemed and taken to be a colored person, and

every person not a colored person having one-fourth

or more of American Indian blood shall be deemed an

American Indian; except that members of Indian tribes

existing in this Commonwealth having one-fourth or

more of Indian blood and less than one-sixteenth of

Negro blood shall be deemed tribal Indians.

3. This case also involves the equal protection and due

process clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Con

stitution of the United States.

6

Questions Presented

1. Do the Virginia anti-miscegenation laws violate the

due process and equal protection clauses of the Fourteenth

Amendment to the United States Constitution?

2. Can a State, either by its criminal or civil law, con

stitutionally prohibit and penalize a marriage between and

cohabitation by two of its residents because one of them

is Negro and the other is white?

Statement of the Case

On or about June 2, 1958, Mildred Jeter, a Negro female,

and Eichard Perry Loving, a white male, were lawfully

married in the District of Columbia pursuant to its laws.

There is no dispute here that Mrs. Loving is a “ colored

person” and Mr. Loving is a “white person” within the defi

nitions of those terms in the Virginia Code or that, at all

times relevant to this litigation, the Lovings were residents

of Virginia (R. 20).

Shortly after their marriage, appellants returned to Vir

ginia and established their marital abode in Caroline

County. On July 11, 1958, warrants were issued charging

them with attempting to evade the Virginia ban on inter

racial marriages (R. 2). Thereafter, a grand jury of Caro

line County indicted them in the following manner:

The said Richard Perry Loving, being a white per

son, and the said Mildred Delores Jeter, being a colored

person, did unlawfully and feloniously go out of the

State of Virginia, for the purpose of being married,

and with the intention of returning to the State of

7

Virginia and were married out of the State of Virginia,

to-wit, in the District of Columbia on June 2, 1958,

and afterwards returned to and resided in the County

of Caroline, State of Virginia, cohabiting as man and

wife against the peace and dignity of the Common

wealth (R. 5-6).

On January 6, 1959, the Lovings entered pleas of guilty,

and they were each sentenced to one year in jail but their

sentences were suspended, as previously explained, on the

condition that they leave Virginia and not return together

for twenty-five years.

After their convictions and until the summer of 1963,

the Lovings took up residence in the District of Columbia.

Subsequently, they retained counsel who have represented

them in their attempts to reverse the judgment and set

aside the sentences of the Circuit Court of Caroline County

so that they may live peacefully and without fear of legal

prosecution in their home state.

On October 28, 1964, appellants instituted a class action

in the United States District Court for the Eastern Dis

trict of Virginia, requesting that a three-judge federal

court be convened to declare the Virginia anti-miscegenation

laws unconstitutional and to enjoin the State officials from

enforcing appellants’ prior convictions.

On February 11, 1965, the three-judge federal court

(Judges Bryan, Butzner and Lewis) entered an interlocu

tory order continuing the matter so that appellants herein

might have a reasonable time to “ submit [the] issue

[therein] to the state courts for final determination.”

Since the summer of 1963 and during the pendency of all

8

court proceedings thereafter and at the present time, the

Lovings have continued to reside in Virginia, safe from

further arrest and prosecution only because the three-judge

federal court’s interlocutory order stated that:

. . . in the event the plaintiffs [Lovings] are taken

into custody in the enforcement of the said judgment

and sentence, this court, under the provisions of title

28, section 1651, United States Code should grant the

plaintiffs bail in a reasonable amount during the pen

dency of the State proceedings in the State Courts

and in the Supreme Court of the United States, if

and when the case should be carried there . . . .

Summary of Argument

This case challenges the validity of the entire Virginia

statutory scheme prohibiting and penalizing miscegenation.

There is no legal argument of any merit which would

allow Virginia to punish its residents who enter into

miseegenetic marriages within the State and, on the

other hand, prohibit Virginia from punishing couples who

go out of the State to evade the anti-miscegenation laws.

Furthermore, any holding that the particular evasion stat

ute, Section 20-58, under which the Lovings were convicted,

is invalid on some limited ground would not do justice to

appellants because their marriage under settled Virginia

case law would be void. Thus they would be subject to fur

ther prosecution for the same acts that have caused the

convictions from which they appeal, namely, the inter

racial nature of their marriage together with their co

habitation as man and wife in Virginia. Also, they would

suffer the outrageous civil effects of being parties to a

9

void miscegenetic marriage: they -would not be able to

inherit from each other; their three children would be

deemed illegitimate; they could lose Social Security bene

fits, the right to file joint income tax returns and even

rights to workmen’s compensation benefits—all of which

are contingent upon a valid marital relationship.

Accordingly, this case requires a determination whether

a State, either by its criminal or civil law, can constitu

tionally prohibit and penalize a marriage between two com

petent, consenting adults and their cohabitation within such

State solely because one of them is Negro and the other

is white.

The Virginia anti-miscegenation laws were originally

passed primarily for economic and social reasons as means

to foster and implement the institution of slavery. To a

lesser extent, they were also the products of the majority

white group’s racial and religious prejudices and fears of

the Negro. The present Virginia statutory scheme as en

acted in 1924 both incorporated many past miscegenation

laws and expanded the prohibitions on interracial marriage.

This legislation, however, was motivated primarily by ra

cial intolerance and antagonism directed against the Negro,

and sought to preserve only the integrity of the so-called

“ White Race” for reasons intellectually analogous to

Hitler’s goal of creating a Super Race.

In light of the history, symbolic meaning and effects of

miscegenation laws, their deleterious social impact on our

people, both Negro and white, is immeasurable. So long

as they exist they will continue to perpetuate racial bitter

ness and constitute an open affront to the dignity of the

individual Negro American.

1 0

A correct appraisal of the legislative history of the

Fourteenth Amendment shows that anti-miscegenation

laws were not exempted from the application of its broad

guarantees of equal protection and due process of law.

These guarantees were open-ended and meant to be ex

pounded in light of changing times and circumstances to

prohibit racial discrimination.

Virginia’s miscegenation laws violate the equal protec

tion and due process clauses of the Fourteenth Amend

ment. The principle of Brown v. Board of Education, 347

U. S. 483 (1954)—however it is articulated—controls the

constitutionality of these laws and makes clear their in

validity under the equal protection clause. Similarly, there

is a constitutionally protected right of marriage which

these laws arbitrarily and capriciously infringe in viola

tion of due process of the law. While the States have an

interest in and the power to regulate marriages, restric

tions on marriage based on race are constitutionally sus

pect. The State has the burden to show an overriding

legislative purpose to justify such restriction. There is no

such purpose to justify anti-miscegenation laws.

1 1

A R G U M E N T

I.

The validity o f the entire Virginia statutory scheme

prohibiting interracial marriage is at issue in this case.

The “ evasion statute”, Section 20-58, under which appel

lants were convicted supplements Virginia’s basic prohibi

tion of Negro-white marriages celebrated within Virginia

(Va. Code § 20-54); it deals with Virginia residents* who

leave the State with the intention of returning in order to

marry in a State permitting Negro-white marriages and

who then return and cohabit in Virginia as man and wife.

By the terms of the evasion statute, a marriage of such a

couple “ shall be governed by the same law as if it had been

solemnized in this State.” Accordingly, such couples are

(i) subject to the same criminal punishment as Negroes

and whites who marry in Virginia, namely, the penalty

imposed by Va. Code § 20-59 of imprisonment for not less

than one nor more than five years, and (ii) their marriages

are considered void under Virginia law. Va. Code § 20-57;

Naim v. Naim, 197 Va. 80, 87 S. E. 2d 749 (1955) (In an

annulment action, marriage held void where the Virginia

couple had gone to North Carolina to evade the Virginia

law). Furthermore, the terms “white person” and “ colored

person” in the evasion statute are comprehensible, if at

# Unlike the situation in Naim v. Naim, 197 Ya. 80, 87 S. E. 2d

749, vacated and remanded, 350 U. S. 891 (1955), aff’d, 197 Va.

734, 90 S. E. 2d 849, appeal dismissed, 350 U. S. 985 (1956),

there is no dispute that appellants were residents of Virginia at

the time of their marriage and at all other times relevant to this

litigation. Thus, there is no question here of the permissible appli

cation of the evasion statute to non-residents of Virginia.

1 2

all, only by use of the definitions in other provisions of

Virginia’s anti-miscegenation laws. (Va. Code § 20-54 de

fines “white person” and §1-14 defines “ colored person”.)

Because appellants’ miscegenetie marriage is void under

Virginia law, various outrageous civil effects can result:

one spouse may be prevented from inheriting from his or

her mate by other heirs who prove the forbidden inter

racial nature of the marriage (see, e.g., In re Shun Taka-

hashi’s Estate, 113 Mont, 400, 129 P. 2d 217 (1942)); par

ticipants in such marriages can lose their marital rights

under intestacy and similar statutes, Stevens v. United

States, 146 F. 2d 120 (10th Cir. 1944), and the benefits of

Social Security (see 42 U. S. C. § 416(h)(1),* of joint in

come tax returns, and of workmen’s compensation—all of

which are contingent upon a marital relationship. Toler v.

Oaktvood Smokeless Coal Corp., 173 Va. 425, 4 S. E. 2d 364

(1939). A husband may desert his mate and their children

without the usual legal consequences and apparently free

of any obligation of support. See generally G-reenberg,

R ace R elations and A merican Law 348 (1959). The Lov-

ings’ three children may be illegitimate, Greenhow v. James’

Executor, 80 Va. 636 (1885), even though a Virginia stat

ute legitimatizes the issue of void marriages, and they

may lose inheritance rights in their parents’ estates.

* For a recent example where a death gratuity usually payable

to a widow of a U. S. military serviceman was not paid because the

validity of anti-miscegenation laws remains in doubt see the letter

of the Assistant Comptroller General of the United States dated

January 6, 1965, which refused to authorize payment of arrears of

pay and a death gratuity to the Negro widow of a deceased white

soldier because the validity of their miscegenetie marriage which

occurred in Texas “cannot be resolved on the basis of the current

judicial decisions . . . ” as quoted in Seidelson, Miscegenation Stat

utes and the Supreme Court: A Brief Prediction of What the

Court Will Do and Why, Catholic U. L. Rev. 156, 157 (1966).

13

Even if there were no evasion statute (or if some tech

nical ground could be found to invalidate only the evasion

statute and leave the rest of Virginia’s anti-miscegenation

scheme in effect), appellants’ situation would not be signifi

cantly changed. Under Virginia law, their marriage is void

for both criminal and civil law purposes because Virginia

follows the established conflict of laws principle that the

state of the domicile of the parties at the time of their

marriage will refuse to recognize its validity if the mar

riage is offensive to such State’s public policy. Kinney v.

Commonwealth * 71 Va. 858 (1878); Creenhow v. James’

Executor,** 80 Va. 636 (1885); See generally R estatement,

Conflict of L aws §§ 133-134 (1934); R estatement (S ec

ond) Conflict of L aws § 132 (Ten. Draft No. 4-1957);

Taintor, Marriage in the Conflict of Laws, 9 V and. L. R ev.

* In Kinney, the conviction of a Negro spouse of a white woman

for illegal cohabitation with her was upheld by Virginia’s highest

court even though the couple had been married in Washington,

D. C. which recognized the validity of the marriage. The first Vir

ginia evasion statute (Va. Acts of Assembly, 1877-78, ch. VII § 3 at

p. 302) relating to Negro-white marriages had been enacted but was

not in effect with respect to this case. Judge Christian in his opinion

said that “ . . . without such statute, the marriage was a nullity . . .

denounced by the public law of the domicile [Virginia] as unlawful

and absolutely void . . . the law of the domicile will govern in such

case, and when they return, they will be subject to all penalties, as

if such marriage had been celebrated within the state whose public

law they have set at defiance . . . connections and alliances so un

natural that God and nature seem to forbid them, should be pro

hibited by positive lawr, and be subject to no evasion.” At 865-66,

869.

## In Greenhow, a miscegenetic marriage valid where performed

in the District of Columbia was deemed void under Virginia law in

a case holding the eleven children of such marriage to be illegiti

mate. This holding with respect to the nullity of such a marriage

was incorporated into a statute in 1887 by means of a provision

that such marriages of Virginia residents outside of Virginia were

to be governed by the same law as if the marriages were solemnized

in Virginia. V a . Code A n n . § 2253 (1887).

14

607, 627-29 (1956). Tims the same civil effects of the mar

riage would result and also appellants would he subject to

criminal prosecution for illegal cohabitation,* Kinney v.

Commonwealth, supra, § 18.1-193 (Y a. Code A n n . 1950, Vol.

4, p. 253), or fornication, McPherson v. Commonwealth, 69

Va. 939 (1877), §18.1-188 (V a. Code A n n . 1950, Vol. 4, p.

253), or perhaps both.

The reality of Virginia’s statutory scheme prohibiting

miscegenation is clear. Both the evasion statute (§ 20-58)

and the basic prohibition of miscegenetic marriages (§20-

54) serve and are necessary to effect the same unjustifiable

purpose: to prohibit and penalize interracial marriages

involving persons who after their marriage reside as man

and wife in Virginia. We doubt that the basic prohibition

would be invoked against a couple married in Virginia if

they did not cohabit there as man and wife. Of course the

evasion statute requires cohabitation as an essential ele

ment of its proscribed crime. Nevertheless, any technical

distinction between the statutes is academic. The con

stitutionality of the evasion statute, as applied .. to ap

pellants in light of Virginia’s clear public policy against

miscegenation and the relevant conflict of laws principle,

cannot be determined separately from a determination of

the constitutionality of Virginia’s civil and criminal bans

on interracial marriages celebrated in Virginia. There is

no constitutional or other legal argument of substance

which would justify allowing Virginia to deny the validity

of an interracial marriage, under its civil or criminal law,

if such marriage were celebrated in Virginia while pro-

m It should be noted that Virginia has no specific statute pro

hibiting only interracial fornication or cohabitation. See, e.g., the

Florida interracial cohabitation statute invalidated in McLaughlin

v. Florida, 379 U. S. 184 (1964).

15

habiting Virginia from penalizing the marriage if the mar

riage of Virginia residents took place outside of Virginia.

Accordingly, a holding that the evasion statute is in

valid, on some limited ground, without reaching the basic

question of the validity of Virginia’s bans on miscegenetic

marriages, would seem disingenuous and incorrect under

the circumstances. Of even more importance, such a hold

ing would not do justice to appellants. Their marital life

has been in continuous legal jeopardy for over eight and

one-half years and their marriage, under settled Virginia

law, with or without the evasion statute, is void. Therefore,

they would be subject to further prosecution for the same

acts that have caused their prior convictions, namely, the

interracial nature of their marriage together with their

cohabitation as man and wife in Virginia.

II.

The history of the Virginia anti-miscegenation laws

shows they are relics of slavery and expressions of

racism.

To understand that the Virginia anti-miscegenation laws

at issue here are both relics of slavery and expressions of

modern day racism which brand Negroes as an inferior

race, it is necessary to consider their history.*

As Professor Wadlington has recently noted,** it is sur

prising that Virginia which prides itself on the story of

* Counsel wish to thank Mr. Frank F. Arness for the use of his

unpublished thesis which deals with the history of these laws and

was written in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a master’s

degree in history at Old Dominion College, Norfolk, Virginia.

** Wadlington, The Loving Case: Virginia’s Anti-Miscegenation

Statute in Historical Perspective, 52 V a . L. Rev. 1189 (1966).

(Hereafter cited as “ Wadlington” )

16

how one of her early white sons married an Indian princess*

today maintains one of the strictest statutory bans on racial

intermarriage. Virginia has enacted a great deal of anti-

miscegenation legislation beginning in the seventeenth cen

tury and spanning a period of nearly three centuries to

1932 when the last enactment on this subject was passed.

Early History

The first Negroes arrived in the colony of Virginia in

1619. Their numbers increased slowly. White indentured

servants served as the principal source of manpower in

the early colonial period before plantation owners recog

nized the value of the Negro slave. See generally Bruce,

E conomic H istory of V irginia in ti-ie Seventeenth Cen

tury, Vol. I, Chap. IX (MacMillan & Co. 1896). As late as

1673, white servants still outnumbered Negroes by four to

one. R euter, T he A merican R ace P roblem: A Study of

the Negro 136 (New York: Thomas Y. Crowell Company,

revised ed. 1938) (Hereafter cited as “Reuter” ).

Generally, indentured white servants came from the low

est social strata in England or elsewhere and the Virginia

colonists considered them originally on the same level as

the Indian slave or servant and the Negro. A principal

difference among persons of the servant class was their

tenure of service; the white servant usually served out a

seven-year contract while the Negro or Indian might be

enslaved for life. As a result of their common status, this

class intermixed to a considerable extent both within and

outside the banns of marriage. Reuter, 134-138.

* If John Rolfe and Pocahontas were married in Virginia to

day, they would be guilty of violating the anti-miscegenation law.

V a . Code A n n . § 20-54.

17

Some of the earliest actions of the colonial govern

ment involving miscegenation reflected religious prejudice

against Christian-heathen intermixing. See Bruce, supra,

Yol. II, pp. 109-110 and Wadlington, 1191. However,

with the establishment of Negro slavery, economic reasons

for restricting miscegenation became dominant. Slave

owners wanted protection from the loss of their slave prop

erty through intermarriage with a free white Christian

by laws that all offspring of slaves with whites, whether

free or indentured servants, would be deemed slaves.

By the 1660s, illegitimate births from relationships

among Negro slaves and white masters presented prob

lems primarily relating to the status of the children. A

1662 Act provided that any child of an “Englishman” and

a “negro woman” should be slave or free according to the

condition of the mother. 2 Laws of Va. 170 (Hening 1823).

This kind of legislation, according to some historians,

led to intentional slave breeding by slave-owners.

At the time of the 1662 Act, there was nothing to pre

vent interracial marriages of whites and Negroes. The

colonial society and the church viewed any such marriages

in a disparaging manner and in some cases mobs may have

acted to apply extralegal punishment to the couples.

Reuter, 137.

Apparently social pressure was insufficient to prevent

such marriages, for in April of 1691, the Virginia Assembly

passed the first law proscribing Negro-white marriages as

part of “An Act for Suppressing Outlying Slaves.” 3

Laws of Va. 86 (Hening 1823). One stated purpose of

this Act was to prevent “ that abominable mixture and

spurious issue which hereafter may arise” from interracial

18

unions, demonstrating that racial prejudice as well as eco

nomic reasons led to the early miscegenation laws. The

free white person marrying a Negro was to be banished

from Virginia forever. (Considering the practical banish

ment of the Lovings in 1959, Virginia’s policy has not

changed much since 1691.) This same Act* provided that

any English white woman who had a bastard by a Negro

should pay the church wardens fifteen pounds or, in default

of payment, she would be indentured for a term of five

years. The child in each instance would be bound out by the

church wardens until he or she reached thirty years of age.

In 1705, the Assembly eliminated the banishment pen

alty for miscegenation and instead imposed a six-month

prison sentence, without bail, and a fine. Ministers marry

ing such persons were also penalized and, to this day,

Virginia punishes a minister who performs such a mar

riage by a fine, one-half of which goes to the informer.

Va. C ode A nn , §20-60 (1960).

By the end of Virginia’s colonial period, Negroes with

few exceptions were enslaved. Negro children by a white

father were free or bond ^according to the condition of

the Negro mother. White women, free or bond, were se

verely penalized for bearing a child from a miscegenetic

* The primary purpose of this Act was to authorize the capture

of “negroes, mulattoes and other slaves” who hide “ in obscure places

killing hoggs and committing other injuries to the inhabitants” by

local sheriffs and their deputies who were specifically authorized,

if such slaves “shall resist, run away or refuse to deliver and sur

render . . . to kill and destroy such negroes, mulattoes and other

slave or slaves by gunn or any otherwaise whatsoever.” If any slave

were so killed, the owner was to receive “ four thousand pounds of

tobacco by the publique” . At this time, slaves were legally con

sidered to be personal property and treated the same as household

goods, horses, cows, oxen and hogs. Bruce, supra,, Vol. II, pp.

99-100.

19

union and such child was bound out in prescribed periods

of servitude by the parish vestrymen. Finally, the leg

islature had constructed a law punishing the free white

partner of a miscegenetic marriage by both imprisonment

and fine.

No change of significance occurred until the Code of

1849 in which it was provided that any marriage between

a white person and a Negro was absolutely void without

further legal process. V a. Code ch. 109 § 1, Yol. I at 471

(1849) (now § 20-57).

After the Civil War no essential changes wTere made in

Virginia’s anti-miscegenation laws until the enactment of

the Racial Integrity Act of 1924.# However, the first eva

sion statute, the predecessor of Section 20-58 under which

the Lovings were convicted, was passed in 1878 to deal

with interracial couples leaving the State to marry in a

jurisdiction which allowed their marriages and then re

turning to live in Virginia even though the Virginia courts

had treated such marriages as void without a statute. In

the same year, for the first time, the penalty imposed on a

party to a miscegenetic marriage was made clearly ap

plicable to the Negro spouse. Also, the penalty was en

larged to not less than two nor more than five years in the

penitentiary.## Va. Acts of Assembly 1877-1878, ch. VII,

§ 8 at 302 (now § 20-59). *

* Problems with respect to the definition of racial classifications

and to the civil effects of miscegenetic marriages did occur but have

no specific relevance here. See Wadlington, 1195-1199.

## The final Virginia statute on this subject passed in 1932 made

the crime of interracial marriage a felony but reduced the minimum

term of imprisonment to one year. Va. Acts of Assembly 1932, Ch.

78 at 68 (now § 20-59).

2 0

Despite the existence of deterrent legislation, interracial

sexual relationships continued and increased after the Civil

War. Reuter, 141. The rising tide of mulatto offspring

and the passing of many of them as whites motivated

a tightening of the definition of Negro and enactment of

stronger anti-miscegenation legislation. In the slave days,

there had been essentially economic motivations for deny

ing Negro slaves the legal right to marry. In fact, as

previously indicated, no criminal penalties were imposed

on the Negro partner of a miscegenetic marriage until 1878.

With the end of slavery, unfortunately, new motivations

arose which were purely racist and based on the theory that

Negroes and other non-whites are members of inferior

races.

Racial Integrity Act of 1924

After World War I, the United States experienced a

period of intolerance and racial animosity expressed in the

spread of all forms of hate groups and super-patriotic

orders with dogmas of “yellow peril”, “mongrelization of

the white race” and “ un-Americanism”. In fact, at the time

of passage of the Racial Integrity Act of 1924, racists

predicted the destruction of the white race if Negro-white

miscegenation and the tide of immigrants arriving in the

United States each year were not suppressed. Earnest

Sevier Cox, in his book entitled W hite A merica (Rich

mond: White America Society, 1923), posed this alleged

threat to America and suggested federally supported colo

nization and uniform legislation barring the mixing of the

races in any form.

White racial superiority, a carry-over in the South from

slavery days, formerly had rested primarily on observa

2 1

tions by 19th. century scientists and questionable Biblical

texts. The authority which the new and popular science of

eugenics provided for this concept was eagerly received in

Virginia. Originally eugenics had dealt with the breeding

of animals and the disclosure of their heredity traits. Race

conscious Americans seized upon immature conclusions of

eugenicists and subjected them to an overdose of racial

pride embodied in the concept of “Anglo-Saxonism”. New

Englanders and Southerners alike talked about “mongrel-

ization of the white race” and “ race suicide” . Racial preju

dice increased; “Anglo-Saxon clubs of America” sprang up

throughout Virginia and sponsored legislation designed to

halt the mixing of the races in Virginia.*

On February 7, 1924, on petition from these organiza

tions, and in response to the racist sentiment of the time,

a number of State senators initiated the bill which ulti

mately became the Racial Integrity Act of 1924, and was

originally entitled “A Bill to Preserve the Integrity of the

White Race” .* ** Members of both houses of the General

Assembly displayed a great interest in the bill. The House

of Delegates invited John Powell, a renowned Virginia

pianist and local racist, to speak before it on the dangers

of “ racial amalgamation” . According to the Richmond

Times Dispatch of February 18, 1924, the delegates se

lected Powell because of his knowledge of “ ethnological

problems and conditions in various parts of the world and

# Richmond Times Dispatch, February 17, 1924, p. 6. At the

time of passage of the Racial Integrity Act of 1924, there were

Anglo-Saxon clubs in Virginia at the University of Virginia, Col

lege of William and Mary, Virginia Military Institute, Washington

and Lee College and Randolph Macon College. Clubs could also be

found at Richmond and other cities and towns of the State.

** Journal of the Senate of the Commonwealth of Virginia (Rich

mond: Superintendent of Public Printing, 1924), p. 135.

2 2

Ms wide acquaintance among European authorities and

statesmen”. Powell was very much involved in the national

eugenics movement and had, himself, organized many of

the Virginia Anglo-Saxon clubs which petitioned the As

sembly to take action to preserve the white race. Powell

stressed to a “well-filled gallery” the need to preserve

the white race from contamination with non-white blood,

and observed that when a white race absorbed the Negro

through amalgamation its civilization disintegrated.

Powell was assisted in his efforts by Dr. W. A. Plecker,

the State Registrar of Vital Statistics, who supplied “vital

statistics” to show confusion in Virginia concerning racial

origins and the necessity for a stronger anti-miscegenation

law to preserve racial integrity. Richmond Times Dispatch,

February 13, 1924, p. 1. In response to Powell’s address

and the statistics of Dr. Plecker, the House introduced a

bill of its own only three days after Powell’s address.

Thereafter, apparently without significant debate or

controversy between the Senate and the House of Dele

gates, the Act, technically entitled “An Act to Preserve

Racial Integrity” (Va. Acts of Assembly, 1924, ch. 371),

passed the Senate on February 27, 1924, and the House on

March 8,1924, and was approved by the Governor on March

20, 1924.

It in part repeated earlier prohibitions on miscegenation

but also effected “ a sweeping change in the scope of the

law . . . by keying the miscegenation provisions to a new

and very narrow definition of a ‘white person’.” Wadling-

ton, 1200. Under this new definition, a white person was

forbidden to marry anyone other than another white person

defined to be one “who has no trace whatsoever of any

23

blood other than Caucasian . . . ” (now § 20-54).* For

the first time, Virginia prohibited the marriage of whites

with Mongoloids and other non-Negro races as well as

Negroes. Earnest Sevier Cox, in his book, T he South ’s

P art in Mongbelizing the Nation (Richmond: White

America Society, 1926), called the Virginia law “probably

the most perfected expression of the white racial ideal

since the institution of caste in India some four thousand

years ago” . At p. 98.

Other new provisions of the 1924 legislation which re

main in force today remind one of the laws of Nazi Ger

many: The State Registrar of Vital Statistics was em

powered to prepare a form so that persons could certify

to their “ racial composition” to local registrars who could

issue duplicate certificates of racial composition, one for

the person registering and one for the State Registrar

(now §20-50). The knowing or willful falsification of a

registration certificate as to color or race was made a

felony punishable by one year in the penitentiary. A mar

riage license was not to be issued unless the issuing official

had “ reasonable assurance” that the statements of the

parties as to color were correct, and the Act assigned the

burden of proof, if a question should arise, to the persons

applying for the license (now § 20-53).

All statutes relating to racial intermarriage which were

in effect in 1924 were made applicable to marriages pro

hibited by the new provisions. Thus the 1924 act carried

forward the provision making Negro-white marriages void,

* There was an exception to this definition designed apparently

to protect the descendants of John Rolfe and Pocahontas which

deemed persons “who have one-sixteenth or less of the blood of the

American Indian and no other non-Caueasic blood” to be white

persons.

24

the civil and criminal applicability of the evasion provision

[Section 20-58], and the criminal penalties applicable to

the parties to an interracial marriage and to the minister

performing the ceremony.

III.

Anti-miscegenation laws cause immeasurable social

harm.

There is still another history to be told; it lurks beneath

the surface of the “written” history we have examined.

This is the story of what these laws have done to our

entire people. Unhappily this is the familiar chronicle of

race relations in our nation. Here briefly is some intima

tion of what the miscegenation laws—born out of oppres

sion and hatred—contribute to our legacy.

The high degree of racial mixture that exists in the

United States—estimates of the ratio of Negro Americans

with at least one known white forebear run as high as

72 to 83 per cent, P ettigrew, A P rofile of the Negro

A merican 68 (1964)—has occurred predominantly in the

South under illicit conditions fostered by the miscegena

tion laws. Of more relevance, this racial mixing was

almost entirely in the context of illicit exploitative sexual

intercourse; white male of Negro female. Myrdal, A x

A merican D ilemma, Chapter 5 especially at pp. 1204-1207

(1962) (Hereafter cited as “Myrdal” ) ;* Cash, T he Mind of

the S outh 87-88 (1941).

* Throughout this section, we often utilize this definitive treatise

on the Negro problem in America by the eminent Swedish social

economist, Gunnar Myrdal.

This history of illicit sex relationships conditions, psycho

logically and sociologically, the entire pattern of American

race relations. Nor can its importance be overemphasized

since “ [t]o the ordinary white American the caste line

between white and Negro is based upon, and defended by,

the anti-amalgamation doctrine”, and “ [moreover this] . . .

doctrine, more than anything else, gives the Negro problem

its uniqueness among other problems of lower status groups,

not only in terms of the intensity of feeling but more

fundamentally in the character of the problem.” Myrdal,

54 (our emphasis). This socio-psychological taproot of

American racial prejudice is nowhere more vividly de

scribed than in Lillian Smith’s great work, K illers of t h e

Dream, in the chapter entitled “ Three Ghost Stories” (1961

ed.), and in W . J. Cash’s, T he Mind of t h e South (1941).

Considering such accounts, it is difficult to avoid Myrdal’s

conclusion that

[t]he fixation on the purity of white womanhood, and

also part of the intensity of emotion surrounding the

whole sphere of segregation and discrimination, are

to be understood as the backwashes of the sore con

science on the part of white men for their own or

their compeers’ relations with, or desires for, Negro

women. Myrdal, 591.

The Negro participant in this abnormal sex relationship

did not escape psychologically unscathed. Although iso

lating psychogenic factors is difficult, there can be no doubt

of the profound adverse effect racial discrimination has had

on the individual personality traits of the Negro. See Petti

grew, supra at Chapter I, “ The Kole and Its Burdens”

(1964); cf., Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483

26

(1954). It is a frightful thing, to use one example, if

Miss Smith is right when she claims “ . . . there is a

burning blasting scorn of white men growing in the

minds . . . of nearly every woman of the colored race. . . . ”

Smith, supra at 109. Any social construct which can en

gender such group hatred and personal antagonism is

wrong.

Admitting the futility of attempts to expunge the sins

of the past, Virginia’s anti-miscegenation laws (and those

of sixteen Southern and border States) stand as a present

day incarnation of an ancient evil. As such, these laws do

not simply bar interracial marriage, they perpetuate and

foster illicit exploitative sex relationships. Moreover, these

laws are explicitly designed to that end. To fail to under

stand such invidious purpose is to doom the reasonable

man to an unrequited search for logic, viz:

. . . the relative license of white men to have illicit

intercourse with Negro women does not extend to for

mal marriage. The relevant difference between these

two types of relations is that the latter, but not the

former, does give social status to the Negro woman

and does take status away from the white man. These

status concerns . . . are functions of the caste ap

paratus which, in popular theory, is itself explained

as a means of preventing intermarriage, the whole

theory [thus] becoming largely a logical circle. Myrdal,

590 (our emphasis).

The relevance of such purpose to our scope of inquiry

here—the present day impact of these laws—seems clear.

27

Cutting through the psychological overlay and rationali

zations, Myrdal explains that:

. . . The great majority of non-liberal white South

erners utilize the dread of ‘intermarriage’ . . . to jus

tify discriminations which have quite other and wider

goals than the purity of the white race. . . . what white

people really want is to keep the Negroes in a lower

status. Myrdal, 590-91.

And enlarging on the same theme he adds:

The persistent preoccupation with sex and marriage

in the rationalization of social segregation and dis

crimination against Negroes is . . . an irrational escape

on the part of the whites from voicing an open demand

for difference in social status between the two groups

for its own sake. Ibid.

In short, the basis of harm that makes this Court’s

warrant equal to the ultimate evil of these laws is that

they constitute an infliction of indignity upon every person

cast among others as not good enough to marry a “white

person”.

Paradoxical as it may seem that this most blatant ascrip

tion of inferior status is the last to be condemned by this

Court, it is fitting that the opportunity to make the con

demnation universal presents itself. The miscegenation

laws, understood as the paradigm of “ all of these thousand

and one precepts, etiquettes, taboos, and disabilities in

flicted upon the Negro [having the] common purpose: to

express the subordinate status of the Negro people and

the exalted position of the whites,” Myrdal, 66, and func

28

tioning chiefly as the State’s official symbol of a caste

system, must be dealt with accordingly.

IV.

The legislative history of the Fourteenth Amendment

does not exempt anti-miscegenation laws from its ap

plication.

The only substantive argument advanced by the Com

monwealth of Virginia in its Statement opposing the not

ing of jurisdiction by this Court was that the legislative

history of the Fourteenth Amendment conclusively estab

lishes that it was not intended to apply to miscegenation

laws. Eclectic statements from the debates on the bill

which became the Civil Eights Act of 1866 are used to

support this thesis, which was also advanced in the School

Segregation Cases, and a law review article, Pittman, The

Fourteenth Amendment: Its Intended Effect on Anti-

Miscegenation Laws, 43 N. C. L. R ev. 92 (1964). (A more

recent article in support of the same thesis, which was not

cited by the Commonwealth, is Avins, Anti-Miscegenation

Laws and the Fourteenth Amendment: The Original In

tent, 52 V a. L. R ev. 1224 (1966).)

A close examination of such statements indicates that

many legislators who felt the Civil Rights Act of 1866 was

not intended to reach miscegenation laws based their views

on the now discredited equal application theory (later enun

ciated as a judicial construction of the equal protection

29

clause in Pace v. Alabama, 106 U. 'S. 583 (1883)). For

example, the Commonwealth quotes Senator Trumbull as

follows (at p. 8 of its Statement):

How does this interfere with the law of Indiana pre

venting marriages between whites and blacks'? Are

not both races treated alike by the law of Indiana?

Does not the law make it just as much a crime for a

white man to marry a black woman as for a black

woman to marry a white man, and vice versa? I pre

sume there is no discrimination in this respect, and

therefore your law forbidding marriages between

whites and blacks operates alike on both races. This

bill does not interfere with it. If the negro is denied

the right to marry a white person, the white person

is equally denied the right to marry the negro. I see

no discrimination against either in this respect that

does not apply to both. . . . (our emphasis)

But Senator Trumbull’s presumption has proven incorrect;

equal application of inequalities based on race is uncon

stitutional. McLaughlin v. Florida, 379 II. S. 184, 188

(1964).

If such legislative history—whatever its real meaning

assuming one could read the minds of the legislators from

the historical record—were determinative of the scope

of the Fourteenth Amendment, then it might not have been

applicable to school segregation, jury service and other

forms of segregation. See, e.g., Brown v. Board of Educa

tion, 347 U. S. 483 (1954); Strauder v. West Virginia, 100

U. S. 303 (1880); Norris v. Alabama, 294 U. S. 587 (1935);

30

Biekel, The Original Understanding and the Segregation

Decision, 69 H arv. L. R ev. 1, 64-65 (1956).

A correct appraisal of the legislative history of the

broad guarantees of the Fourteenth Amendment for pur

poses of constitutional adjudication is that they were open-

ended and meant to be expounded in light of changing

times and circumstances. See Biekel, swpra, at 64 (“But

the relevant point is that the Radical leadership succeeded

in obtaining a provision whose effect was left to future

determination” . ) ; Kelly, Clio and the Court: An Illicit Love

Affair, 1965 Sup. Ct. R ev. 119, 145 (Evidence from the

debates indicates that Bingham and others “hoped that the

prohibitions on racial discrimination would have an open-

ended character, i.e., would grow through judicial interpre

tation and congressional legislation with the progress of

time” ) ; Wechsler, Toward Neutral Principles of Constitu

tional Law, 73 H arv. L. R ev. 1, 32 (1959) (“ . . . the words

[of the equal protection clause] are general and leave room

for expanding content as time passes and conditions

change” ) ; Burton v. Wilmington Parking Authority, 365

U. S. 715, 722 (1961) (“Because the virtue of the right to

equal protection of the laws could lie only in the breadth

of its application, its constitutional assurance was reserved

in terms whose imprecision was necessary if the right were

to be enjoyed in the variety of individual-state relations

which the Amendment was designed to embrace” ).

In short, the applicability in 1967 of the equal protection

and due process clauses to miscegenation laws cannot be

ascertained by a resort to doubtful legislative history but

must be determined by this Court, utilizing all appropriate

means of constitutional adjudication and bearing in m ind

Chief Justice Hughes’ admonition:

31

If . . . the great clauses of the Constitution must

be confined to the interpretation which the framers,

with the conditions and outlook of their time, would

have placed upon them, the statement carries its own

refutation. It was to guard against such a narrow

conception that Chief Justice Marshall uttered the

memorable warning—‘we must never forget that it is

a constitution we are expounding’ (McCulloch v. Mary

land, 4 Wheat, 316, 407) . . . Home Bldg. & Loan

Ass’n v. Blaisdell, 290 U. S. 398, 442-43 (1934).

V .

The Virginia anti-miscegenation laws are racially dis

criminatory and deny appellants equal protection of the

laws.

There can be no doubt that the conviction of the Lovings

was because Mrs, Loving is a Negro. But for this fact, and

that Bichard Loving is a “white person” under Va. Code

§ 20-54, no crime would have been committed. Except for

the difference of color, the state never raised any objec

tion to the marriage. If both had been white or both had

been other than white, their marriage would be valid.

In Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483 (1954),

this Court struck down segregation in public schools as a

violation of equal protection. Whether Brown means that

(i) the Fourteenth Amendment prohibits the intentional

disadvantaging of Negroes as Negroes by any form of

legalized segregation (Black, The Lawfulness of the Segre

gation Decisions, 69 Y ale L. J. 421 (1960)) or, (ii) there can

be no rational basis for a statutory classification which

stamps Negroes as inferior (Applebaum, Miscegenation

32

Statutes: A Constitutional and Social Problem, 53 Geo.

L. J. 49, 86 (1965)) as the Virginia anti-miscegenation

laws do or, (iii) a state statute cannot constitutionally

deny Negroes the freedom to associate with whites

(Weehsler, Toward Neutral Principles of Constitutional

Law, 73 Harv. L. R ev. 1, 34 (1959)), we agree with Pro

fessor Bickel that the principle of the Brown case should

control the constitutionality of miscegenation laws. B ickel,

T he Least Dangerous B ranch 71 (1962).

In fact, miscegenation laws seem more clearly uncon

stitutional than school segregation since (i) the right of

two consenting, competent adults to marry each other seems

even more fundamental than the right of students to attend

an integrated public school, (ii) there clearly is no equal

alternative and (iii) both parties to an interracial marriage

wish to associate or join together as man and wife, while

in Brown, arguably, the white students, or some of them,

did not wish to associate w7ith the Negro students.

When a Negro is denied the right, solely because he

is a Negro, to marry a white woman who wishes to marry

him, the law discriminates against him and denies him as

well as the woman equal protection of the laws. While mis

cegenation laws have been upheld in the past by use of the

“ equal application” theory of Pace v. Alabama, that these

laws do not discriminate because both whites and Negroes

are prohibited from intermarrying (see, e.g., Jackson v.

City ami County of Denver, 109 Colo. 196, 124 P. 2d 240

(1942)), this theory “ . . . represents a limited view7 of

the Equal Protection clause which has not withstood analy

sis in the subsequent decisions of this Court.” McLaughlin

v. Florida, 379 U. S. 184,188 (1964).

33

Statutory distinctions based on race alone have been

struck down in many cases involving rights much less

substantial than the right to marry. See, e.g., Hamm v.

Virginia State Board of Elections, 230 F. Supp. 156 (E. D,

Va.), aff’d per curiam, 379 U. S. 19 (1964) (designation of

race in voting and property records); Anderson v. Martin,

375 U. S. 399 (1964) (designation of race on nomination

papers and ballots); Watson v. City of Memphis, 373 U. S.

526 (1963) (segregation in public parks and playgrounds);

Oyama v. California, 332 U. S. 633 (1948) (racial restric

tion involving alienation of land) ; Takahashi v. Fish &

Game Commission, 334 U. S. 410 (1948) (racial restriction

on commercial fishing licenses); Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118

U. S. 356 (1886) (racial restriction on licensing of laun

dries). And this Court has enunciated as the law of the

land that:

Distinctions between citizens solely because of their

ancestry are by their very nature odious to a free

people whose institutions are founded upon the doc

trine of equality. For that reason, legislative classi

fication or discrimination based on race alone has

often been held to be a denial of equal protection.

Hirabayashi v. United States, 320 U. S. 81, 100 (1943).

In fact, “ classification based on race alone is inherently

discriminatory” . Horsey v. State Athletic Comm., 168 F.

Supp. 149, 151 (E. D. La. 1958), aff’d per curiam, 359

U. S. 533 (1959).

In McLaughlin v. Florida, supra, this Court held that

there must be “ some overriding statutory purpose requir

ing the proscription of the specified conduct when engaged

in by the white person and a Negro, but not otherwise” ,

34

379 IT. S. at 192, and also stated, in effect, that the burden

of demonstrating this overriding purpose is on the State

because:

. . . the central purpose of the Fourteenth Amend

ment was to eliminate racial discrimination emanating

from official sources in the States. This strong policy

renders racial classifications ‘constitutionally suspect’

. . . and ‘in most circumstances irrelevant’ to any con

stitutionally acceptable legislative purpose . . . 379

U. S. at 192.

At least two members of this Court have recognized

that there can be no such “ overriding statutory purpose”

to justify a miscegenation law:

I cannot conceive of a valid legislative purpose

under our Constitution for a state law which makes the

color of a person’s skin the test of whether his conduct

is a criminal offense. (Mr. Justice Stewart, joined by

Mr. Justice Douglas, concurring in McLaughlin, 379

U. S. at 198.)

The Supreme Court of Appeals of Virginia upheld the

miscegenation laws in this case (R. 25) by reliance on its

earlier decision in Naim v. Nairn, 197 Va. 80, 87 S. E. 2d

749 (1955). In Naim, the purposes of these laws were set

forth as follows:

We are unable to read in the Fourteenth Amend

ment to the Constitution, or in any other provision of

that great document, any words or any intendment

which prohibit the State from enacting legislation to

preserve the racial integrity of its citizens, or which

denies the power of the State to regulate the marriage

35

relation so that it shall not have a mongrel breed of

citizens. We find there no requirement that the State

shall not legislate to prevent the obliteration of racial

pride, but must permit the corruption of blood even

though it weaken or destroy the quality of its citizen

ship. . . . 87 S. E. 2d at 756.

Of course the maintenance of racial purity or integrity is

a meretricious basis for these laws for there is no evidence

to support the existence of so-called “pure” races. M on

tagu, Man ’s Most Dangerous My t h : T he F allacy of R ace

(4th ed. 1964); see authorities discussed in Weinberger,

A Reappraisal of the Constitutionality of Miscegenation

Statutes, 42 Cornell L. Q. 208, 217 (1957). The idea

of a pure race is a subterfuge to cloak ignorance of the

phenomenon of racial variation.

Even if racial purity were a constitutionally acceptable

purpose, the Virginia laws are not reasonably calculated

to effect this purpose. The only race kept “pure” is the

Caucasian. This is because the Virginia laws are not de

signed to preserve the purity of races but, as the original

name* of Virginia’s 1924 Racial Integrity Act indicates and

its legislative history affirms, to preserve only the integrity

of one group: members of the so-called “White” ** or

“Anglo-Saxon Race” . A person of Chinese ancestry, for

example, is not included within the definition of “ colored

* “A Bill to Preserve the Integrity of the White Race.” See p. 21

of this Brief.

## jjior a persuasive discussion of the fact that there is no white

race and never has been one see “A Four-Letter Word That Hurts”

by anthropologist, Morton H. Fried, in Saturday Review, October

2, 1965.

36

persons” [Va. Code § 1-14], or “white persons” [Ya. Code

§ 20-54]. Tims the marriage of a Chinese and a “white

person” would be unlawful under Va. Code § 20-54, Naim

v. Naim, 197 Va. 80, 87 S. E. 2d 749 (1955). On the other

hand, a marriage between a Chinese and a “ colored person”

would be neither unlawful nor subject to prosecution. Cer

tainly this is not equal protection. In fact, Virginia’s con

cept of “ race” , based on statutory definitions which are

a combination of legal fiction and genetic nonsense, is a

social rather than a scientific concept, designed to preserve

the social status of Virginia’s politically dominant group.

The other articulated legislative purpose is the preven

tion of “ corruption of the blood” from racial intermixing

which would “weaken or destroy the quality of its [Vir

ginia’s] citizenship” . To assume this is a valid legislative

purpose—as the highest Virginia court did—which justifies

miscegenation laws is not enough to meet the State’s bur

den with respect to laws which on their face discriminate

on the basis of race or color. Virginia has not presented,

and we submit cannot present, reputable scientific evidence

to prove that a person of mixed blood is somehow “ inferior”

in quality to one of racial purity, assuming arguendo that a

person of racial purity such as a pure Caucasian exists.*

Most serious students of anthropology do not even consider

this question a present problem for research, agreeing that

the races of the world are essentially equal in native ability

and capacity for civilization and that group differences are

for the most part cultural and environmental, not heredi

* Even if reliable scientific evidence could be presented to sup

port an inferior race theory, the State’s burden would not be met.

The possibility of less superior but healthy progeny of interracial

couples would not justify the serious restriction on personal liberty

effected by miscegenation laws prohibiting interracial marriages.

37

tary. See, e.g., T he R ace Question and Modern Science:

T he Statement on the Nature op R ace and R ace D iffer

ences, Article 7 (UNESCO, 1952).

As for the progeny of racial intermixing, there is not a

single anthropologist teaching at a major university in the

United States who subscribes to the theory that Negro-

white matings cause biologically deleterious results. See

letter to editor from members of Department of Anthro

pology, Columbia University, N. Y. Times, December 15,

1964. On the contrary, some conclude that, because of a

certain hybrid vigor, interracial marriage may be desirable

and the offspring superior, citing the Hawaiian population,

among others, to support this view. See Shapiro, R ace

Mixture (UNESCO, 1965), and the authorities discussed in

Cummins & Kane, Miscegenation, The Constitution and

Science, 38 D icta 24, 47-49 (1961).

We will not postulate unarticulated legislative purposes.*

In the final analysis, these laws are unjustifiable relics

of slavery—initially passed to foster that peculiar and dis

tasteful institution, and re-enacted in their present form

as part of the surge of racial antagonism and intolerance

of the 1920’s. They deny Negroes and other non whites equal

protection of the law and stamp them as inferior citizens.