Goffer v. West Petition for a Writ of Certiorari

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1995

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Goffer v. West Petition for a Writ of Certiorari, 1995. a66e4f89-b39a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/7e0825d5-c113-4e7a-a614-d09dfb184bbe/goffer-v-west-petition-for-a-writ-of-certiorari. Accessed March 14, 2026.

Copied!

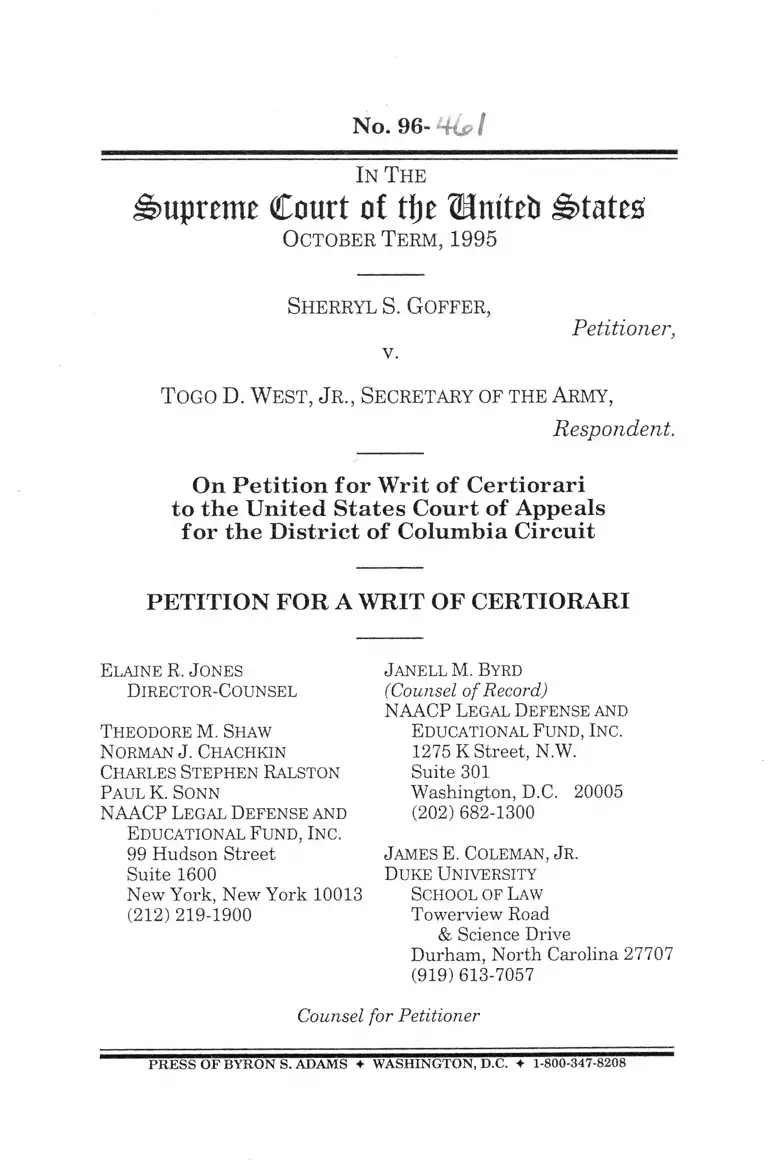

No. 96- Hip I

I n T h e

Supreme Court of tfje IMteb States?

O c t o b e r T e r m , 1995

S h e r r y l S. G o f f e r ,

v.

Petitioner,

T o g o D. W e s t , J r ., S e c r e t a r y o f t h e A r m y ,

Respondent.

On Petition for Writ of Certiorari

to the United States Court of Appeals

for the District of Columbia Circuit

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI

Elaine R. J ones

Director-Counsel

Theodore M. Shaw

Norman J. Chachkin

Charles Stephen Ralston

Paul K. Sonn

NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street

Suite 1600

New York, New York 10013

(212) 219-1900

J anellM. Byrd

(Counsel o f Record)

NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc.

1275 K Street, N.W.

Suite 301

Washington, D.C. 20005

(202) 682-1300

J ames E. Coleman, J r.

Duke University

School of Law

Towerview Road

& Science Drive

Durham, North Carolina 27707

(919) 613-7057

Counsel for Petitioner

PRESS OF BYRON S. ADAMS ♦ WASHINGTON, D.C. ♦ 1-800-347-8208

1

Q u e s t io n P r e se n t e d

Did the court of appeals err in holding that the

three-page "Memorandum and Order" issued by the trial

court — that necessarily contained the court’s findings of fact

and conclusions of law thereon as required by F e d . R. C iv .

P. 52 — also satisfied F e d . R. Q v . P. 58, which requires that

"[ejvery judgment shall be set forth on a separate document"

and which this Court has repeatedly instructed "must be

mechanically applied in order to avoid . . . uncertainties as

to the date on which a judgment is entered?" United States

v. Indrelunas, 411 U.S. 216, 222 (1973); see also Bankers

Trust Co. v. Mallis, 435 U.S. 381, 386 (1978).

11

P a r t ie s

The parties in the proceedings below were:

Sherryl S. Goffer,

Plaintiff in the District Court, Plaintiff-Appellant in

the Court of Appeals

Togo D. West, Jr., Secretary of the U.S. Army,

Defendant in the District Court, Defendant-Appellee

in the Court of Appeals

Ill

T a b l e o f C o n ten ts

Question Presented ................... i

P arties............... ii

Table of Authorities............. v

Opinions B elow ............................. 1

Jurisdiction ................................. 2

Legal Provision Involved................................................. 2

Statement of the Case . ....................... 2

A. Delay By the District Court .................... 3

B. Procedural Irregularities

Attendant to the District

Court’s Issuance of the Order

Disposing of this C ase................... 5

C. The Motion for Entry

of Judgm ent............................................ 8

D. The Ruling Below...................... 8

IV

Reasons for Granting the Writ ...................................... 9

I. The Decision Below Flatly

Contradicts This Court’s

Decisions in United States v.

Indrelunas and Bankers Trust

Co. v. Mallis .......................................... .. 9

II. The Decision Below Conflicts

with Decisions of the Second,

Third, Fourth, Ninth, and Tenth

Circuit Courts of A ppeals............. .. 14

III. In Permitting the District

Court’s Serious Procedural

Errors to Deny Petitioner Her

Right to Appellate Review,

the Decision Below So

Departs From the Accepted

and Usual Course of Judicial

Proceedings as to Call for

Exercise of This Court’s

Supervisory Pow ers............... ................. 17

Conclusion . . .. 21

T a b le o f A u t h o r it ie s

Cases: Pages:

Allah v. Superior Court of Calif.,

871 F.2d 887 (9th Cir. 1989) ...................... 15, 16

Axel Johnson, Inc. v. Arthur Anderson & Co.,

6 F.3d 78 (2d Cir. 1993)................................. 15

Bankers Trust Co. v. Mallis,

435 U.S. 381 (1978) . ........... ........................passim

Barber v. Whirlpool Corp.,

34 F.3d 1268 (4th Cir. 1994) ............. .......... .. . 15

Clough v. Rush,

959 F.2d 182 (10th Cir. 1992)...................... 15, 16

Cooper v. Town of East Hampton,

83 F.3d 31 (2d Cir. 1996) .................. ................. 15

Gregson & Assoc, v. Virgin Islands,

675 F.2d 589 (3d Cir. 1982)........................ 15, 16

Hensley v. Eckerhart,

461 U.S. 424 (1983)............................................ 17

Kanematsu-Gosho, Ltd. v. M/T Messiniaki Aigli,

805 F.2d 47 (2d Cir. 1986)............. ................. . 15

Paddock v. Morris,

783 F.2d 844 (9th Cir. 1986) . . . . . . . . . . . 15, 16

Shalala v. Schaefer,

509 U.S. 292 (1993)........................................... 18

Pages:

Spann v. Colonial Village, Inc.,

899 F.2d 24 (D.C. Cir.),

cert, denied, 498 U.S. 980 (1990) . ......... .............13

United States v. Indrelunas,

411 U.S. 216 (1973)........... .......... .......... .. . passim

Vernon v. Heckler,

811 F.2d 1274 (9th Cir. 1987) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 15

Rules and Statutes: Pages:

Fed. R. App. P. 4 ............................... .......... . . . 6, 13, 18

Fed. R. Civ. P. 52 . ............................... ................... .. 1, 16

Fed. R. Civ. P. 5 8 ............................... .. passim

Fed. R. Civ. P. 77(d) ......... .. 6, 7, 17

Sup. Ct. R. 10(a) ................................................... .. 14, 20

Sup. Ct. R. 10(c) . ........................... .......................... 9, 14

Civil Service Reform Act,

5 U.S.C. § 1101 et seq. .................................. .. . 3, 5

5 U.S.C. § 7702(e)(1) ............................................... .. 3

Judicial Improvements Act of 1990,

28 U.S.C. §§ 471-82 ................ .......... .......... . . . 20

28 U.S.C. § 1254(1) .......................................... .. ......... .. 2

vi

Pages:

28 U.S.C. § 1331 . . ............... .................................. .. 3

28 U.S.C. § 1343 ................................... .. 3

Title VII, Civil Rights Act of 1964,

42 U.S.C. §§ 2000e-3a, 2000e-16 . .................. 3, 5

Other Authorities: Pages:

S. Rep. No. 416, 101st Cong., 2d Sess. (1990),

reprinted in 1990 U.S.C.C.A.N. 6802 ........... .. . 20

vu

In T h e

Supreme Court of ti)e Umteb States?

O c t o b e r T e r m , 1995

No. 96-

Sh e r r y l S. G o f f e r ,

Petitioner;

v.

T o g o D. W e st , J r ., Se c r e t a r y o f t h e A r m y ,

Respondent.

On Petition for Writ of Certiorari

to the United States Court of Appeals

for the District of Columbia Circuit

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI

Petitioner, Sherryl S. Goffer, respectfully prays that

a writ of certiorari issue to review the judgment of the Court

of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit entered in

this proceeding on June 24, 1996.

O pin io n s Be lo w

The opinion of the United States Court of Appeals

for the District of Columbia Circuit is unreported and is set

out at pages la-2a of the Appendix hereto ("App."). The

Memorandum and Order of the United States District Court

for the District of Columbia disposing of petitioner’s claims

is unreported and is set out at App. 5a-6a. The Decision

2

and Order of the United States District Court for the

District of Columbia denying petitioner’s motion for a

preliminary injunction is unreported and is set out at App.

7a-lla. The Order of the United States District Court for

the District of Columbia denying petitioner’s motion for

entry of judgment is unreported and is set out at App. 3a-4a.

The opinion of the United States Court of Appeals for the

District of Columbia Circuit denying petitioner’s earlier

motion for a writ of mandamus to the district court is

unreported and is set out at App. 12a.

J u r is d ic t io n

The judgment of the Court of Appeals for the

District of Columbia Circuit was entered on June 24, 1996.

Jurisdiction of this Court is invoked under 28 U.S.C.

§ 1254(1).

L e g a l P r o v isio n I n v o lv e d

This case involves F e d . R. Civ . P. 58,1 which

provides, in pertinent part:

Every judgment shall be set forth on a

separate document. A judgment is effective

only when so set forth and when entered as

provided in Rule 79(a).

St a t e m e n t o f t h e Ca se

This case is an employment discrimination suit

brought against the Secretary of the Army by a civilian army

employee terminated in her fifteenth year of service

1The complete text of Fed. R. Civ. P. 58 is set out at App, 13a.

3

following a history of "exceptional" employment evaluations

and promotions. Plaintiff-petitioner, Sherryl Goffer, alleged

violations of Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, 42

U.S.C. § 2000e-16 and § 2000e-3a, and the Civil Service

Reform Act ("CSRA"), 5 U.S.C. § 1101 et seq. Jurisdiction

over this case in the district court was conferred by 28

U.S.C. §§ 1331 and 1343. See 5 U.S.C. § 7702(e)(1).

This case has been marred by a series of troubling

procedural irregularities in the district court that culminated

in petitioner’s being wrongly denied her right to appeal after

having waited approximately five years after the trial for the

district court to render a decision.

A. Delay By the District Court

This petition brings before this Court a case that at

one time ranked as the oldest pending case undecided after

a bench trial in the United States District Court for the

District of Columbia. The complaint was filed in that court

on September 5, 1985. Dispositive cross-motions on the

CSRA claims were submitted in August of 1987. A bench

trial before Judge Thomas Penfield Jackson proceeded

between September 8 and December 17, 1987. Upon

completion of the trial, the district court expressed its desire

to hear closing arguments from the parties, which it

indicated would be scheduled at a later date. On March 29,

1988, both parties submitted proposed findings of fact and

conclusions of law on the Title VII claims. Thereafter,

nothing happened.

Counsel for petitioner were puzzled both by the long

delay and by the fact that the district court still had not

scheduled closing arguments as it had stated it intended to

do. In an effort to expedite resolution of the case,

petitioner’s counsel took the following steps:

4

(1) Counsel made repeated periodic telephone

inquiries to the district court to check on the status of the

case.

(2) On May 17, 1990, petitioner’s counsel filed a

motion requesting a status conference to discuss resolution

of the case. The court held such a conference on July 18,

1990, at which time it reiterated its desire to hear closing

arguments before rendering a decision and stated that the

court would schedule such arguments.2 However, no action

or decision was forthcoming from the district court.

(3) On April 18, 1991, petitioner filed with the

district court a Request for a Decision in the case. Despite

subsequent telephone inquiries, no response came from the

district court.

(4) On February 8, 1993 — approximately five

years after the close of trial and nearly two years after

petitioner’s Request for a Decision - petitioner reluctantly

sought appellate intervention. Petitioner filed a mandamus

petition in the court of appeals, asking the higher court to

direct the district court to render a decision within thirty

days. On April 8, 1993, the court of appeals denied the

mandamus petition, but encouraged the district court "to

attend to the resolution of this case as promptly as feasible."

App. 12a.

2The docket confirms that on July 18, 1990, the court indicated

that it would schedule closing arguments.

5

B. Procedural Irregularities Attendant to the District

Courtis Issuance of the Order Disposing of this Case

Unbeknownst to petitioner and the court of appeals,

prior to that court’s April 8, 1993 order encouraging the

district court to act "promptly,” on February 23, 1993, the

district court apparently had issued a three-page

"Memorandum and Order" (App. 5a-6a) in which the court

purported to assess the evidence presented in the case, made

certain findings of fact and conclusions of law based on that

evidence, and recited that judgment was entered for the

defendant. In the order, the district court stated that it was

incorporating by reference the findings and conclusions that

it had set forth in an earlier order issued November 20,

1985, in which it had denied a motion by petitioner for a

preliminary injunction (App. 7a~lla). The order was

surprisingly conclusory, resolving in just over two pages the

numerous questions of fact and law presented in a five-day

bench trial and the many complex issues raised in cross

motions for summary judgment on the CSRA claim.3

Even more surprising, however, is the fact that the

district court did not notify the court of appeals of its

decision, although the petition for a writ of mandamus was

still pending in that court. Nor did the district court notify

the court of appeals after receipt of the April 8, 1993 order

encouraging "promptf]" action. Such a notification also

would have informed petitioner that the district court

3Illustrating the detailed nature of the factual and legal inquiries

were the parties’ proposed findings of fact and conclusions of law on

the Title VII claims that jointly exceeded 100 pages. Although the

court’s order incorporated by reference its findings and conclusions

from the 1985 preliminary injunction order, that earlier order, of

course, did not consider the substantial evidence uncovered during

discovery that was presented during the five-day bench trial.

6

believed that her time to file a notice of appeal had begun

to run. Knowledge of the district court’s February' 23 ruling,

even at that April date, would have permitted petitioner to

safeguard her appellate rights. At that date, petitioner could

still have filed a precautionary notice of appeal, for even if

the February 23 order had constituted a valid entry of

judgment — which it did not — under Fed. R. App. P. 4(a)

petitioner would have had until April 24, 1993, to file a

notice of appeal.

The case was subject to further peculiar treatment; in

particular, the highly irregular manner in which the district

court clerk entered the Memorandum and Order reflected

violations of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure and was

inconsistent with elementary notions of fairness:

(1) First, it appears that the district court never

mailed copies of the order to petitioner’s counsel. As a result,

it was not until more than two years later on June 5, 1995,

that petitioner’s counsel, in the course of obtaining a copy

of the docket for the purpose of attaching it to a second

mandamus petition, learned that an order had been issued

purportedly disposing of the case.4 Although Fed. R. Civ.

P. 77(d) requires the clerk to mail copies of all orders or

judgments to the parties in the case,5 neither of petitioner’s

4During the intervening period, petitioner’s counsel attempted to

check the status of the case by calling the clerk’s office. However,

counsel was informed that such inquiries could no longer be made by

telephone and that parties could check the docket only by use of a

certain computer program (which counsel did not have) or by a

physical examination of the docket at the clerk’s office.

5 Immediately upon the entry of an order or judgment the

clerk shall serve a notice of the entry by m ail. . . upon each

7

two counsel of record ever received any notice of the court’s

decision. The apparent failure of the court to mail a copy

of the order to petitioner’s counsel is confirmed by the

district court docket, which contains no notation indicating

that the order had been mailed, as is required by

Rule 77(d).6

(2) The district court also evidently failed to

transmit the order to the court of appeals, for the court of

appeals ruled on petitioner’s then-pending mandamus

petition six weeks after the district court’s ruling, clearly

demonstrating no knowledge that the district court had

already ruled. Nor did the government take any steps to

bring to the attention of the court of appeals (either before

party . . . , and shall make a note in the docket of the

mailing.

Fed. R. Civ. P. 77(d).

6In opposing petitioner’s motion for entry of judgment,

respondent asserted that the U.S. Attorney’s Office had received a

copy of the February 23 Memorandum and Order within a week of

its issuance, and that the document bore a handwritten "(N)" at the

bottom corner of the first page, which indicated that the clerk had

sent notice of its entry to the parties. In denying petitioner’s motion

for entry of a judgment in conformity with Fed . R. Crv. P. 58, the

district court stated, apparently based upon the same notation, that

"the February 23, 1993 judgment indicates that notice of entry of

judgment was sent to the parties counsel" (App. 3a). However, the

docket contains no indication that notice of entry of the February 23

order was sent to the parties, as Rule 77(d) requires, see supra note 5.

Indeed, other than orders actually transcribed by a court reporter

during court proceedings, the docket entry for every other order in

the case except this one bears a typewritten "(N)," confirming such

mailing in accordance with the Rule. (A copy of the docket has been

lodged with the Clerk of this Court.)

8

or after it issued its decision) the district court ruling which

had, in effect, rendered the mandamus petition moot.

(3) Finally, and most importantly for the purposes

of this petition, the district court failed to comply with

Rule 58’s strict requirement that every court opinion

disposing of a case be accompanied by a separate document

setting forth the judgment in the case. The "Memorandum

and Order" included a cursory discussion of the facts and the

applicable law, concluding with a single sentence purporting

to enter judgment for defendant (App. 5a-6a). However, the

order was not accompanied by a separate document setting

forth the judgment as required by Rule 58.

C. The Motion for Entry o f Judgment

As noted above, on June 5,1995, petitioner’s counsel,

in the course of preparing to file a second mandamus

petition, obtained an updated copy of the docket and

learned for the first time of the district court’s February 23,

1993 Memorandum and Order. Upon obtaining a copy of

that Memorandum and Order from the clerk’s office,

counsel learned that the district court had failed to comply

with Rule 58’s separate judgment requirement. Petitioner

immediately filed on June 6, 1995, a motion requesting the

district court to remedy that error by entering a separate

judgment as required by Rule 58. The district court denied

that motion on July 24, 1995 (App. 3a-4a), and petitioner

appealed that ruling to the court of appeals.

D. The Ruling Below

The court of appeals affirmed the district court’s

denial of the motion for entry of a separate judgment in a

cursory opinion holding that the district court’s

Memorandum and Order entered two years earlier had

9

satisfied the requirements of Rule 58, and that a separate

judgment document was therefore not needed (App. la).

This petition for writ of certiorari followed.

Reasons for Granting the Writ

I

The Decision Below Flatly Contradicts

This Court’s Decisions in United States v.

INDRELUNAS AND BANKERS TRUST CO. V.

Mallis

Since the amendment of F e d . R. C iv . P. 58 in 1963

to include the separate judgment rule, this Court has

repeatedly stressed the importance of the requirement.

Although the Court has recognized one narrowly

circumscribed exception to the rule, that exception clearly

does not apply here. The decision below conflicts with the

unequivocal teaching of this Court and should be corrected

through a grant of certiorari. See Sup. Ct. R. 10(c).

In United States v. Indrelunas, 411 U.S. 216 (1973),

this Court explained the purpose and meaning of the

Rule 58 separate document requirement:

Rule 58 was substantially amended in

1963 to remove uncertainties as to when a

judgment is entered . . . .

The reason for the "separate

document" provision is clear from the notes of

the advisory committee of the 1963

amendment. See Notes of Advisory

Committee following F e d . R u l e C iv . P. 58,

reported in 28 U.S.C. Prior to 1963, there

was considerable uncertainty over what

10

actions of the District Court would constitute

an entry of judgment, and occasional grief to

litigants as a result of this uncertainty. See,

e.g., United States v. F. & M. Schaefer Brewing

Co., 356 U.S. 227 (1958). To eliminate these

uncertainties, which spawned protracted

litigation over a technical procedural matter,

Rule 58 was amended to require that a

judgment was to be effective only when set

forth on a separate document.

Professor Moore makes the following

cogent observation with respect to the

purpose of the separate-document provision

of the rule:

"This represents a mechanical

change that would be subject

to criticism for its formalism

were it not for the fact that

something like this was needed

to make certain when a

judgment becomes effective,

which has a most important

bearing, inter alia, on the time

for appeal and the making of

post-judgment motions that go

to the finality of the judgment

for purposes of appeal." 6A J.

M o o r e , F e d e r a l P r a c t ic e

1F 58.04 [4.-2], at 58-161 (1972).

Indrelunas, 411 U.S. at 119-21. In light of this purpose, this

Court concluded that "[Rule 58] must be mechanically applied

in order to avoid new uncertainties as to the date on which

a judgment is entered." 411 U.S. at 222 (emphasis added).

11

Five years later in Bankers Trust Co. v. Mallis, 435

U.S. 381 (1978), this Court clarified further the meaning and

application of Rule 58. Cases had arisen repeatedly in

which the parties had regarded as final — and attempted to

appeal from -- a district court ruling that, while disposing of

all claims, did not set forth the judgment in a separate

document as required by Rule 58. In such cases, strict

enforcement of Rule 58 would be wasteful as it would

require dismissal of what often was a fully-briefed appeal,

only for the district court to go through the formality of

entering a separate judgment, at which point the appellate

process would begin anew. In Mallis, the Court, while

stressing the critical importance of the separate judgment

rule, sensibly held that in certain very limited circumstances

the requirement might be waived. Where both parties are

prepared to go forward with an appeal, notwithstanding the

lack of a separate judgment, and where no part)' would be

prejudiced, "parties to an appeal may waive the separate

judgment requirement of Rule 58." Mallis, 435 U.S. at 387.

The Court explained:

The separate-document requirement was thus

intended to avoid the inequities that were

inherent when a party appealed from a

document or docket entry that appeared to be

a final judgment of the district court only to

have the appellate court announce later that

an earlier document or entry had been the

judgment and dismiss the appeal as untimely.

The 1963 amendment to Rule 58 made clear

that a party need not file a notice of appeal

until a separate judgment has been filed and

entered. See United States v. Indrelunas, 411

U.S. 216, 220-222 (1973). Certainty as to

timeliness, however, is not advanced by

holding that appellate jurisdiction does not

12

exist absent a separate judgment. If, by error,

a separate judgment is not filed before a

party appeals, nothing but delay would flow

from requiring the court of appeals to dismiss

the appeal. Upon dismissal, the district court

would simply file and enter the separate

judgment, from which a timely appeal would

then be taken. Wheels would spin for no

practical purpose.

Mallis, 435 U.S. at 385. The Court continued:

The need for certainty as to the timeliness of

an appeal, however, should not prevent the

parties from waiving the separate-judgment

requirement where one has accidentally not

been entered. As Professor Moore notes, if

the only obstacle to appellate review is the

failure of the District Court to set forth its

judgment on a separate document, "there

would appear to be no point in obliging the

appellant to undergo the formality of

obtaining a formal judgment." 9 J. M o o r e ,

F e d e r a l P r a c t ic e H 110.08 [2], p. 120 n. 7

(1970). "[I]t must be remembered that the

rule is designed to simplify and make certain

the matter of appealability. It is not designed

as a trap for the inexperienced."

Mallis, 435 U.S. at 386. However, still quoting Professor

Moore, the Court concluded this discussion with the

significant warning that "[Rule 58] should be interpreted to

prevent loss of the right of appeal, not to facilitate loss." Id.

(quoting 9 J. MOORE, FEDERAL PRACTICE 11 110.08[2], p.120

n.7 (1970)) (emphasis added).

13

In holding that the district court’s order satisfied

Rule 58 in this case even though the judgment was not set

forth in a separate document, the court below has created a

new exception to Rule 58 that negates its purpose. The

court of appeals’ summary ruling, which contains no analysis

whatsoever, justifies its holding with a bare citation to Spann

v. Colonial Village, Inc., 899 F.2d 24, 32 (D.C. Cir.), cert,

denied, 498 U.S. 980 (1990). However, Spann arose in a very

different posture from this case and in no way supports the

instant ruling. Spann was a routine application of the waiver

rule outlined by this Court in Mallis: it involved a timely-

filed and fully briefed appeal in a case where no separate

judgment had been entered. Spann was thus a case where

waiving the Rule 58 requirement would avoid an

unnecessary remand and would not result in either party

losing its right to appeal. See Spann, 899 F.2d at 32

(following Mallis).

Unlike Spann, this case does not fall into the

category of cases where the strict Rule 58 requirement may

be waived under Mallis. Here, if Rule 58 is not

"mechanically applied," Mallis, 435 U.S. at 386, petitioner

will lose her right to appeal after unfairly being forced to

wait for years to have her case decided. This result would

be particularly unfair in view of the fact that petitioner was

not able take the precautionary step of filing a provisional

notice of appeal from the defective 1993 Memorandum and

Order, since her counsel never received it.

The court of appeals’ unexplained new exception to

Rule 58 not only construes the rule so as unfairly to deny

petitioner her right of appeal but, if permitted to stand, will

pose a grave risk to the appellate rights of all litigants by

destroying the predictability established by Rule 58.

Safeguarding litigants’ appellate rights depends on the

existence of and adherence to universally recognized "bright-

14

line" standards for determining when a final judgment has

been entered, thus triggering F e d . R. A p p . P. 4 ’s deadlines

for filing an appeal. Before 1963, confusion as to when a

judgment was final had caused litigants unfairly to lose their

rights of appeal. Responding to this serious problem, the

drafters of the 1963 amendments to Rule 58 settled on the

"mechanical" separate judgment requirement as a solution.

Tolerating the court of appeals’ ad hoc creation of a new

exception will gut the Rule 58 amendments, giving rise once

again to the wasteful and unfair uncertainty that prevailed

before 1963. This would be particularly egregious in this

case where petitioner had to mount a five-year effort to get

the district court to decide her case.

In light of this Court’s stern injunction that

"[Rule 58] should be interpreted to prevent loss of the right

of appeal, not to facilitate loss," Mallis, 435 U.S. at 386

(quoting 9 J. M o o r e , F e d e r a l P r a c t ic e H 110.08[2], p.120

n.7 (1970)) (emphasis added), the court of appeals’

dangerously misguided doctrinal innovation stands in

contravention of binding precedent of this Court and, under

Su p . Ct . R. 10(c), should be corrected through exercise of

the certiorari power.

II

The Decision Below Conflicts with

Decisions of the Second, Third, Fourth,

Ninth, and Tenth Circuit Courts of

Appeals

Not only is the ruling of the Court of Appeals for the

District of Columbia Circuit in this case unfaithful to this

Court’s teaching in Indrelunas and Mallis, but the decision

conflicts with rulings of at least five other federal courts of

appeals. See Su p . Ct. R. 10(a). The Courts of Appeals for

the Second, Third, Fourth, Ninth, and Tenth Circuits have

15

all held that an order that disposes of a case and that

contains a discussion of the legal analysis supporting the

ruling cannot satisfy the separate judgment requirement of

Rule 58. See Cooper v. Town of East Hampton, 83 F.3d 31,

34 (2d Cir. 1996) (order containing discussion of reasons for

decision directing entry of judgment cannot satisfy separate

judgment requirement); Gregson & Assoc, v. Virgin Islands,

675 F.2d 589, 591-93 & n.l (3d Cir. 1982) (document

containing legal analysis and setting out judgment on final

page does not satisfy separate document requirement);

Barber v. Whirlpool Corp., 34 F.3d 1268, 1274-75 (4th Cir.

1994) (order containing findings of fact and conclusions of

law with last page containing order of dismissal cannot

satisfy separate judgment requirement); Allah v. Superior

Court of Calif, 871 F.2d 887, 890 (9th Cir. 1989) (opinions

containing legal analysis cannot satisfy separate judgment

requirement); Vernon v. Heckler, 811 F.2d 1274, 1276 (9th

Cir. 1987) (same); Paddock v. Morris, 783 F.2d 844, 846 (9th

Cir. 1986) (same); Clough v. Rush, 959 F.2d 182, 185 (10th

Cir. 1992) (orders can contain "neither a discussion of the

court’s reasoning nor any dispositive legal analysis" if they

are to qualify as separate judgments). Indeed, the Court of

Appeals for the Second Circuit has gone even further and

imposed the additional requirement that a document that is

not clearly labeled as a "Judgment" can never satisfy the

separate judgment requirement of Rule 58. See Cooper v.

Town of East Hampton, 83 F.3d 31, 34 (2d Cir. 1996); Axel

Johnson, Inc. v. Arthur Anderson & Co., 6 F.3d 78, 84 (2d

Cir. 1993); Kanematsu-Gosho, Ltd. v. MIT Messiniaki Aigli,

805 F.2d 47, 49 (2d Cir. 1986).

This case law from other circuits conflicts importantly

with the ruling of the Court of Appeals for the District of

Columbia Circuit in this case. Here, the district court’s

opinion, while surprisingly conclusory given the very

significant amount of evidence presented at trial, nonetheless

16

set forth findings of fact and conclusions of law supporting

the court’s ruling for defendant on all claims. See App. Sa

ha. As the district court explicitly recognized, this document

necessarily constituted the court’s findings of fact and

conclusions of law, as required by F e d . R. C iv . P. 52(a)

following a bench trial. See App. 5a. In deeming that such

a document also constitutes the separate judgment required

by Rule 58, the court below has both created a significant

split with the legal standard prevailing in the five other

circuits noted above, and has also created new confusion

regarding the critical issue of when a ruling constitutes a

separate -- and hence final — judgment.

These other circuits have frequently faced

circumstances such as this, where a district court has issued

an order purporting to combine both legal analysis and a

judgment in the same document, and where the losing party

did not take the extra precautionary step of filing a notice of

appeal from that defective order. In such cases, because

failure to enforce the separate judgment requirement would

result in the appeal being time-barred, the courts have

uniformly refused to waive the separate judgment

requirement, thus preserving the opportunity for appeal. See

Gregson & Assoc., 675 F.2d at 591-93 (3d Cir.) (Rule 58 not

waived so as to preserve opportunity to appeal); Allah, 871

F.2d at 890 (9th Cir.) (same); Paddock, 783 F.2d at 846 (9th

Cir.) (same); Clough, 959 F.2d at 185 (10th Cir.) (same).

17

The law and practice of these circuits stands in direct

conflict with the holding of the District of Columbia Circuit

in this case,7 thus making certiorari review appropriate.

I l l

I n P erm ittin g th e D istr ic t C o urt’s

Seriou s P rocedural E rrors to D eny

P etitio n er H er R ig h t to Appella te

R eview , th e Decisio n Below So D eparts

F r o m the Accepted and Usual Co urse o f

J udicial P roceed in gs as to Call fo r

E x ercise o f Th is Co urt’s Supervisory

P owers

A serious error occurred in this case when neither of

petitioner’s counsel of record were notified of the district

court’s Memorandum and Order disposing of the case, after

petitioner had been forced to wait approximately five years

for a ruling. This error could easily have resulted in

petitioner losing her right to appeal, for Rule 77(d)

establishes the harsh rule that "[ljack of notice of the entry

[of an order or judgment] by the clerk does not affect the

time to appeal" as specified under FED. R. APP. P. 4(a). As

petitioner did not learn of the order until two years after it

was entered, the deadline for appealing - here, sixty days

7While the decision by the court of appeals in this matter was

entered summarily and withheld from publication, this does not lessen

the conflict between the rule applied by the court below and that

applied in similar circumstances by the courts of appeals of five other

circuits; Rule 58 contains no exception for unreported decisions. See,

e.g., Hensley v. Eckerhart, 461 U.S. 424, 428, 432 & n.5 (1983) (Court

granted certiorari from unreported summary affirmance "to clarify the

proper relationship of the results obtained to an award of attorney’s

fees" under 42 U.S.C. § 1988, noting "varying standards" applied by

the courts of appeals to the question).

18

under F e d . R. A p p . P. 4(a) - would have long since run

had the district court’s 1993 order otherwise been in

conformity with the applicable rules.8 However -- and

fortunately for petitioner — the deadline for pursuing an

appeal did not begin to run because the district court,

erroneously, failed to enter a separate judgment as required

by Rule 58.

That additional error should have meant that the

grave injustice to petitioner - losing her right to appeal —

would be avoided. Under Rule 58, the time for filing the

notice of appeal does not begin to run until the required

separate judgment is entered. Shalala v. Schaefer, 509 U.S.

292, 302-03 (1993). However, the district court and the

court of appeals denied petitioner’s right to appellate review

by carving out a new exception to the Rule 58 separate

judgment rule, one that negates the very purpose of the rule.

As a result of this unprecedented exception - for which the

cursory lower court opinions offer no coherent justification

(App. la; App. 3a) — the courts below held that judgment in

Petitioner never had the opportunity to file a precautionary

notice of appeal. When the district court issued its Memorandum

and Order, petitioner had a petition for a writ of mandamus pending

in the court of appeals, requesting that court to direct the district

court to decide the case. The court of appeals decided the pending

matter nearly two months after the district court disposed of the case.

In its order, the court of appeals refused to direct the district court

to act, but encouraged that court to decide the case promptly. Since

neither petitioner nor the court of appeals was aware of the district

court’s Memorandum and Order, there was no reason to expect that

the district court’s response to the court of appeals’ ruling had

already occurred. Petitioner therefore had no reason to review the

docket to determine whether the district court had taken any action

that predated the court of appeals ruling. Nor did the continued

delay put petitioner on notice, since the district court already had

delayed acting in the case for five years.

19

the case was validly entered back when the district court

issued its 1993 order,9 and any appeal by petitioner was

accordingly time-barred.

As explained above, this new exception conflicts with

the clear and repeated teaching of this Court, and creates a

9The court of appeals, in its very short decision, termed

"troubling" the fact that petitioner’s counsel did not learn of the

district court’s 1993 ruling until 1995 (App. la). The court criticized

counsel for not having visited the courthouse and examined the

district court docket during the period between 1993 and 1995. (It

was on such a trip in 1995 that petitioner’s counsel learned of the

1993 order.) This criticism is unfair for several reasons. First,

because the district court had told counsel explicitly in 1990 that it

still intended to schedule closing arguments, counsel reasonably

believed that no dispositive order would be entered until after such

arguments. Second, during the first several years after the close of

trial, while petitioner was awaiting action by the court, her counsel

did, in an abundance of caution, regularly check for activity in the

case by telephoning the district court clerk’s office. However, as

previously noted, the clerk’s office later stopped allowing telephone

inquiries, requiring instead that litigants either physically inspect the

docket at the courthouse, or else use a computer program that

counsel did not have, in order to monitor case activity. Finally, as

noted, at the time the district court purported to enter judgment,

petitioner had a petition pending in the court of appeals asking that

court to order the district court to act. The court of appeals did not

dispose of that petition until almost two months after the district

court’s Memorandum and Order was issued. Petitioner respectfully

suggests that in a case where the district court had still not ruled five

years after the close of trial — and where the court had indicated that

it would not rule until closing arguments had been held — it is

unreasonable to expect that counsel should have visited the

courthouse daily or weekly as a precaution against the off chance that

the court might unexpectedly rule - and then fail to mail copies of

the order to both lawyers who had appeared on petitioner’s behalf, or

to the court of appeals where a petition for a writ of mandamus was

pending.

20

conflict with the law of at least five circuits. If left

uncorrected, it will operate in this case to deny petitioner

her basic and important right to appellate review — after she

waited more than five years for a ruling. Such wholesale

denial of a litigant’s right to appeal defies basic notions of

fair play and seriously undermines litigants’ confidence in

the federal courts.10 As such, the decision below so departs

from the accepted and usual course of judicial proceedings

as to call for review on certiorari in the exercise of this

Court’s supervisory powers, as authorized by Su p . Ct .

R. 10(a).

10The extreme delay and inattention in processing this case likely

contributed to its irregular treatment, resulting in the unusual denial

of a party’s cherished right of appeal. Injury of this type, unless

corrected, should be added to the list of problems caused by delays

in the federal judiciary, which Congress recently sought to remedy in

the Judicial Improvements Act of 1990, 28 U.S.C. §§ 471-82.

Congress found cost and delay in the administration of justice posed

serious problems, id. § 471, note, and concluded that high costs and

long delays had left the "time honored promise" of "just, speedy, and

inexpensive resolution of civil disputes" out of reach of many citizens.

S. Rep. No. 416, 101st Cong., 2d Sess. 1 (1990), reprinted in 1990

U.S.C.C.A.N. 6802, 6804.

21

C o n c lu sio n

For the foregoing reasons, the petition for a writ of

certiorari should be granted and the decision of the court

below reversed.

Respectfully submitted,

E l a in e R . J o n es

D ir e c t o r -C o u n se l

T h e o d o r e M. Sh a w

N o r m a n J. Ch a c h k in

Ch a r l e s St e p h e n R a lst o n

P a u l K. So n n

NAACP L e g a l D e f e n s e a nd

E d u c a t io n a l F u n d , I n c .

99 Hudson Street

Suite 1600

New York, New York 10013

(212) 219-1900

J a n e l l M. B y r d

(Counsel o f Record)

NAACP L e g a l D e f e n s e a n d

E d u c a t io n a l F u n d , In c .

1275 K Street, N.W.

Suite 301

Washington, D.C. 20005

(202) 682-1300

J a m es E . C o l e m a n , J r .

D u k e U n iv e r sit y

Sc h o o l o f L aw

Towerview Road

& Science Drive

Durham, North Carolina 27707

(919) 613-7057

Counsel for Petitioner

Appendix

l a

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA CIRCUIT

No. 95-5259

Filed June 24, 1996

Sherryl S. Goffer,

Appellant

v.

Togo D. West, Jr., Secretary of the Army,

Appellee

BEFORE: Wald, Williams, and Tatel, Circuit Judges

ORDER

Upon consideration of the motion for summary

affirmance and the opposition thereto, and the motion for

summary reversal, it is

ORDERED that the motion for summary affirmance

of the order filed July 24, 1995 be granted. The district

court’s February 23, 1993, order complied with the

requirements of Fed. R. Civ. P. 58 and 79(a). See Spann v.

Colonial Village, Inc., 899 F.2d 24, 32 (D.C. Cir. 1990). The

court notes that appellant’s failure to learn of the entry of

the order (through an examination of the district court

docket) until June 1995 is troubling. The merits of the

parties’ positions are so clear as to warrant summary action.

See Taxpayers Watchdog, Inc. v. Stanley, 819 F.2d 294, 297

(D.C. Cir. 1987) (per curiam); Walker v. Washington, 627

F.2d 541, 545 (D.C. Cir.) (per curiam), cert, denied, 449 U.S.

994 (1980). It is

FURTHER ORDERED that the motion for

summary reversal be denied.

2a

The Clerk is directed to withhold issuance of the

mandate herein until seven days after disposition of any

timely petition for rehearing. See D.C. Cir. Rule 41.

Per Curiam

3a

U N IT E D S T A T E S D IS T R IC T C O U R T

F O R T H E D IS T R IC T O F C O L U M B IA

F ile d Ju ly 24, 1995

SHERRYL S. GOFFER,

Plaintiff,

v.

TOGO D. WEST, JR.,

Secretary of the Army,

Defendant.

Civil Action No. 85-2827 TPJ

ORDER

UPON CONSIDERATION of Plaintiffs Motion for

Entry of Judgment, defendant’s opposition thereto, and the

entire record herein, and

UPON FURTHER CONSIDERATION that,

contrary to plaintiffs assertion, the court’s February 23,

1993, Memorandum and Order was entered on the Court’s

docket consistent with Fe d . R. Civ . P. 79(a), and

UPON FURTHER CONSIDERATION that,

contrary to plaintiffs assertion, the Court’s February 23,

1993, Memorandum and Order complies with the separate-

document requirement of Fed. R. Civ. P. 58, and

UPON FURTHER CONSIDERATION that the

February 23,1993, judgment indicates that notice of entry of

judgment was sent to the parties counsel consistent with

Fe d . R. Q v . P. 77(d), and that even if plaintiffs counsel did

not receive a copy, Rule 77(d) explicitly states that "[l]ack of

notice of the entry by the clerk does not affect the time to

appeal or relieve or authorize the court to relieve a party for

failure to appeal within the time allowed, . . ."

4a

ACCORDINGLY, it is by the Court this 21st day of

July, 1995, hereby

ORDERED, that plaintiffs motion for entry of

judgment should be and hereby is DENIED.

s/s ___________________ _

UNITED STATES DISTRICT JUDGE

SUSAN A. NELLOR

Assistant United States Attorney

555 4th Street, N.W.

Room 4116

Washington, D.C. 20001

JAMES E. COLEMAN, ESQUIRE

Wilmer, Cutler & Pickering

2445 M Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20037-1420

JANELL M. BYRD, ESQUIRE

NAACP Legal Defense

& Educational Fund, Inc.

1275 K Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20005

5a

U N IT E D S T A T E S D IS T R IC T C O U R T

F O R T H E D IS T R IC T O F C O L U M B IA

F ile d Feb . 23, 1993

SHERRYL S. GOFFER,

Plaintiff,

v. Civil Action No. 85-2827

JOHN O. MARSH, JR.,

Secretary of the Army,

Defendant.

MEMORANDUM AND ORDER

Two matters remain for resolution by the Court in

this case: (1) findings and conclusions pursuant to Fe d . R.

Civ . P. 52(a), following non-jury trial in September, 1987,

upon plaintiffs Title VII claim that she was first demoted

and later dismissed from federal service in the Department

of the Army in retaliation for her EEO activity: and (2) a

decision upon dispositive cross-motions to reverse or affirm

a decision of the MSPB affirming plaintiffs demotion and

dismissal in August, 1986.

The Court incorporates its findings and conclusions

set forth in its Decision and Order of November 20, 1985,

denying plaintiffs motion for a preliminary injunction.

There the Court found that no discriminatory or retaliatory

animus has been shown on the part of defendants in

reassigning — and in the process demoting — the plaintiff as

part of a major intra-departmental reorganization within the

Department of the Army. Similarly, the court finds that no

such animus permeated her termination from federal service.

The court credits in full the testimony of Delbert

Spurlock, former general counsel of the Army, who, as a

newly appointed Assistant Secretary of the Army in August,

6a

1983, instituted the reorganization to, inter alia, enhance the

Army’s discharge of its EEO responsibilities, as it ultimately

did, although the reorganization entailed the abolition of

plaintiffs position. The Court also credits in full the

testimony of Delores Symons, under whose supervision the

plaintiff came after the reorganization. According to

Symons, plaintiffs performance in her capacity as an EEO

case analyst was markedly deficient, and did not improve

despite concerted efforts made by Symons and others to that

end. The Court finds that plaintiff was justifiably terminated

for cause from federal service in October, 1985, and that no

employment decision by any of her superiors was ever taken

during her term of service on the basis of her race or sex, or

in retaliation for any EEO activity she had undertaken,

either on her own behalf or generally in the court of her

duties.

Having so found, the Court also concludes as well

that the decisions of the MSPB of March 7, 1986, and

August 12,1986, affirming plaintiffs separation from federal

service are supported by substantial evidence, are not

arbitrary or capricious, and are in all respects in accordance

with law, i. e,, the Civil Service Reform Act, as upholding a

legitimate exercise of managerial discretion.

For the foregoing reasons, therefore, it is this 23rd

day of February, 1993,

ORDERED, that judgment is entered in favor of

defendant Secretary of the Department of the Army on the

amended complaint of Sherryl S. Goffer, in its entirety, and

the complaint is dismissed with prejudice.

s/s ______

Thomas Penfield Jackson

U.S. District Judge

7a

SHERRYL S. GOFFER,

Plaintiff,

v. Civil Action No. 85-2827

JOHN O. MARSH, JR.

Secretary of the Army,

Defendant.

U N IT E D S T A T E S D IS T R IC T C O U R T

F O R T H E D IS T R IC T O F C O L U M B IA

F ile d N ov. 20, 1985

ORDER

This Title VII employment discrimination case,

brought on race, sex, and reprisal grounds, is presently

before the Court on plaintiffs motion for preliminary

injunction, her earlier application for a TRO having been

denied.1 She asks that defendant Secretary of Army be

ordered to reinstate her pendente life in the Grade 15 EEO

position she once held in the office of an Assistant Secretary

prior to her demotion pursuant to a reorganization of the

secretariat begun in October, 1983, and her subsequent

termination in the fall of 1985 from government service

altogether. The merits of her claim are, therefore, now at

issue only insofar as they bear upon the familiar four

elements of a meritorious claim for preliminary injunctive

relief:

1) That without such relief, plaintiff will suffer

irreparable injury, having no adequate remedy otherwise;

M ore precisely, defendant has moved to "deny" the motion for

a preliminary injunction, on analogy to Fed . R. Civ . P. 41(b), at the

close of plaintiffs evidence. Defendant was permitted to call one

witness, already present in court, to preserve his testimony in the

event the motion to deny were denied.

8a

2) That plaintiff appears substantially likely to

prevail on the merits at trial;

3) That the equities balance in plaintiffs favor,

or at lease not against her; and

4) That it is in the public interest to grant the

relief requested.2

The Court finds from the evidence that plaintiff has

satisfied, at best, only the third and fourth of the necessary

elements for the relief she seeks; in other words, had she

been able to establish irreparable injury and a likelihood of

success on the merits, it would be neither inequitable, nor

contrary to the public interest, to order a restoration of the

status quo ante while the matter is litigated to a conclusion.

Plaintiffs evidence, however, does not establish that

she is at any greater risk of irreparable injury now than she

was at the time her application for a TRO was denied, as to

which the Court found her allegations of injury insufficient

as a matter of law on the authority of Sampson v. Murray,

415 U.S. 61 (1974). The additional items of injury she has

proffered here, viz., her fear of losing custody of her

2The Court concludes that the two-day evidentiary hearing on

plaintiffs motion — of which all but the final 17 minutes was devoted

to the testimony of plaintiff herself and multiple "adverse" witnesses

she called from the Department of the Army — afforded plaintiff the

full and fair opportunity to which she was entitled to demonstrate the

"pretextual" character of the reasons proffered by the witnesses she

herself called for her demotion and discharge. See Mitchell v.

Baldridge, 759 F.2d 80, 87-88 (D.C. Cir. 1985). Plaintiff does not

contend that her presentation was unduly restricted, but, rather, that

the defendant’s reasons must be deemed prima facie pretextual until

they are further explained in its case-in-chief. The Court finds them

to have been sufficiently explained in the course of plaintiff s case and

in need of no elaboration.

9a

daughter if unable to support her, and her apprehensions for

the future of EEO enforcement generally throughout the

Department of the Army if others are discouraged by her

example, are both purely speculative at this stage, and

neither is of a nature substantially more compelling than

those the Supreme Court rejected in Sampson v. Murray?

Insofar as the likelihood of her ultimate success on

the merits is concerned, plaintiff has offered absolutely no

direct evidence that any of the actions taken by Army

officials which adversely affected her were improperly

motivated by her race or sex, or that her dismissal was an

act of retaliation against her either for her assertion that her

demotion was so motivated, or for her earlier EEO activism.

If race, sex, or activism had played any part, it would have

to be inferred entirely from the circumstances alone that

plaintiff is black, female, and an activist; that her

termination occurred subsequent to her EEO complaint; and

that the explanation of the adverse witnesses for their

conduct towards her is unworthy of credence.

Whether she was treated fairly or not, however, there

is no other evidence to show that those explanations were

"pretextual" for unlawful discrimination or retaliation

originating in considerations of race or sex, or activism,

assuming they were "pretextual’ at all — which the Court

expressly does not find -- and it is at least an equally

permissible inference from this record that the Army

officials were unfavorably disposed towards Ms. Goffer,

because they found her to be a contentious and self-centered

person, unwilling or unable to defer to authority, and more 3

3The latter is, moreover, convincingly refuted by the testimony of

defendant’s only witness that the reorganization of which plaintiff

complains — and the officials she has accused of discrimination —

have significantly advanced the cause of EEO as perceived by Army

EEO officials in the field.

10a

concerned with her own status and perquisites than the

efficient and harmonious operation of her office.4

The Court does expressly find that Mr. Spurlock’s

stated purposes in implementing the reorganization were not

pretextual at all. They had a rational basis unconnected in

any way with a desire to manipulate the EEO program other

than to increase its efficiency. And as to its impact on Ms.

Goffer specifically, her race and sex genuinely made his

decision to go forward with it more difficult. Rather than

seeking to excuse to discriminate against her, or to punish

her for her past EEO activities, Mr. Spurlock actually sought

ways to ameliorate its impact upon her.

The court also expressly credits the testimony of Ms.

Symons and Mr. Matthews as to their subjective reasons for

the actions taken by them which ultimately lead to plaintiffs

termination from federal service. It makes no finding with

respect to whether any of them were objectively justified,

since it is unnecessaiy to do so, having found that the

reasons given had nothing whatsoever to do with plaintiffs

race, sex, or her prior administrative complaint that they

were.

For the foregoing reasons, therefore, it is, this 20th

day of November, 1985,

ORDERED, that plaintiffs motion for a preliminary

injunction is denied; and it is

4In this respect the Court contrasts her attitude toward the

reorganization with that of Ms. Symons who, although also opposed

to it, nevertheless acceded to it gracefully once her objections had

been registered.

11a

FURTHER ORDERED, that the proceedings

thereon are made a part of the record on the trial pursuant

to Fe d . R. Civ . P. 65(a)(2); and it is

FURTHER ORDERED, that this case is scheduled

for a status conference at 9:30 a.m. on January 6, 1986, if

the case still remains before this court.

s/s _____________ _

Thomas Penfield Jackson

U.S. District Judge

12a

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA CIRCUIT

No. 93-5025

Filed April 8, 1993

In re: Sheriyl S. Goffer

Petitioner,

BEFORE: Wald, Ruth B. Ginsburg and Sentelle,

Circuit Judges

ORDER

Upon consideration of the petition for writ of

mandamus, it is

ORDERED that the petition be denied. Mandamus

is an extraordinary and drastic remedy, Kerr v. United States

District Court, 426 U.S. 394, 402 (1967), justified only by

"exceptional circumstances amounting to a judicial

‘usurpation of power.’" Gulfstream Aerospace Corp. v.

Mayacamas Corp., 485 U.S. 271, 289 (1988) (citations

omitted). The district court’s delay, although prolonged,

does not yet warrant the extreme measure petitioner seeks.

See Cartier v. Secretary of State, 506 F.2d 191,199 (D.C. Cir.

1974), cert, denied, 421 U.S. 947 (1975). We encourage the

district court, however, to attend to the resolution of this

case as promptly as feasible. Should the court fail to do so,

we will entertain a renewed petition.

Per Curiam

13a

Federal Rules of Civil Procedure

Rule 58. Entry of Judgment

Subject to the provisions of Rule 54(b): (1) upon a

general verdict of a jury, or upon a decision by the court

that a party shall recover only a sum certain or costs or that

all relief shall be denied, the clerk, unless the court

otherwise orders, shall forthwith prepare, sign, and enter the

judgment without awaiting any direction by the court;

(2) upon a decision by the court granting other relief, or

upon a special verdict or a general verdict accompanied by

answers to interrogatories, the court shall promptly approve

the form of the judgment, and the clerk shall thereupon

enter it. Every judgment shall be set forth on a separate

document. A judgment is effective only when so set forth

and when entered as provided in Rule 79(a). Entry of the

judgment shall not be delayed, nor the time for appeal

extended, in order to tax costs or award fees, except that,

when a timely motion for attorneys’ fees is made under

Rule 54(d)(2), the court, before a notice of appeal has been

filed and has become effective, may order that the motion

have the same effect under Rule 4(a)(4) of the Federal

Rules of Appellate Procedure as a timely motion under

Rule 59. Attorneys shall not submit forms of judgment

except upon direction of the court, and these directions shall

not be given as a matter of course. (As amended Dec. 27,

1946, eff. Mar. 19,1948; Jan. 21,1963, eff. July 1,1963; Apr.

22, 1993; eff. Dec. 1, 1993.)