Roberts v Hermitage Cotton Mills Brief for Appellant

Public Court Documents

March 1, 1979

27 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Roberts v Hermitage Cotton Mills Brief for Appellant, 1979. 3a66059f-c29a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/7e1f9fe1-bd64-45e8-9370-f521f6fc96eb/roberts-v-hermitage-cotton-mills-brief-for-appellant. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

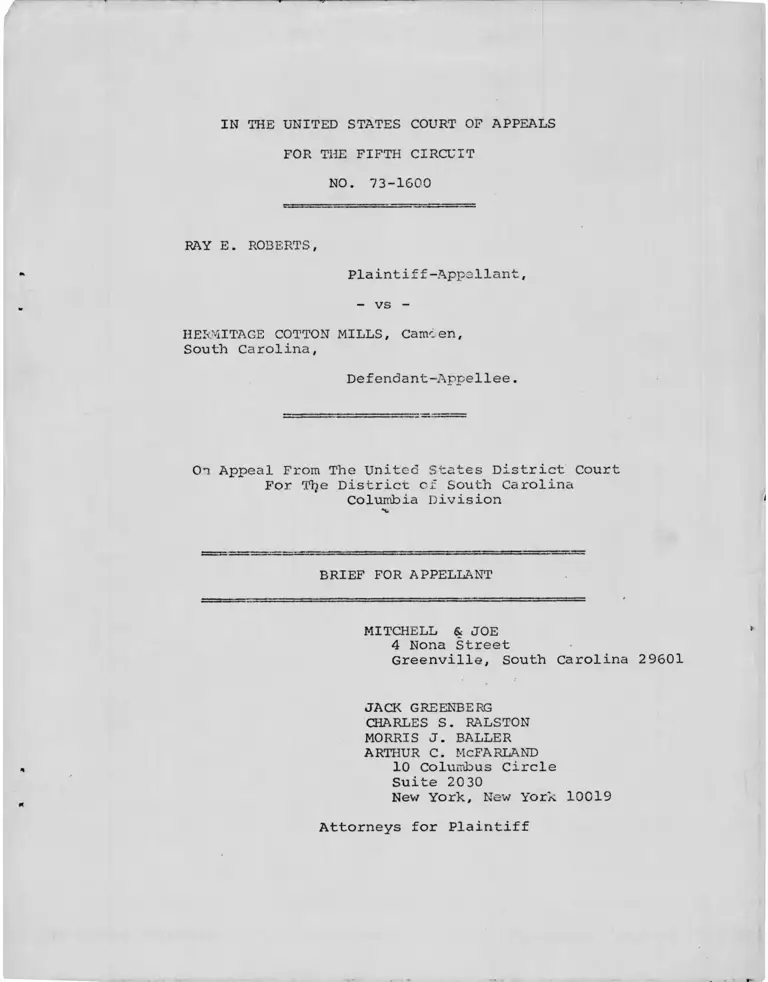

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

NO. 73-1600

RAY E. ROBERTS,

Plaintiff-Appellant,

- vs -

HERMITAGE COTTON MILLS, Camcen,

South Carolina,

Defendant-Appellee.

On Appeal From The United States District Court

For Tfye District of South Carolina

Columbia Division

BRIEF FOR APPELLANT

MITCHELL & JOE 4 Nona Street

Greenville, South Carolina 29601

JACK GREENBERG

CHARLES S. RALSTON

MORRIS J. BALLER

Arthur c. McFarland 10 Columbus Circle

Suite 2030

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Plaintiff

Page

I N D E X

Table of Authorities .............................. j_

Questions Presented ................................. £v

Statement of the Case ............................... 1

I. Proceedings Below ....................... 2

II. Statement of Facts ...................... 2

ARGUMENT

I. THE DISTRICT COURT ERRED IN HOLDING THAT

DEFENDANT DID -NOT VIOLATE TITLE VII OF

THE CIVIL RIGHTS ACT OF 1964 IN DIS

CHARGING PLAINTIFF FOR HIS RELIGIOUSBELIEFS .................................. 5

A. Defendant Did Not Attempt An

Accommodation, of Plaintiff's

Religious Beliefs As Required By

Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights

Act And the EEOC Guidelines .......... 7

b. The Evidence Presented at Trial Dons Not Support the Trial

Court's Finding of Undue Hardship ...... 9

C. The Evidence Does Not Support a

Holding That a Reasonable Accommodation is Possible ............... 12

II. THE COURT BELOW ERRED AS A MATTER OF LAW IN STATING THAT EVEN IF INJUNCTIVE RELIEF

IS ORDERED, SPECIAL CIRCUMSTANCES RENDERING BACK PAY AND COUNSEL FEES INAPPROPRIATE

EXIST H E R E ..... ..............•.......... 13

CONCLUSION________________'....................... 20

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Bowe v. Colgate-Palmolive Co., 415 F.2d 711

(6th Cir. 1969)................................ 15,

Claybaugh v. Pacific Northwest Bell Telephone

Co., 355 F.Supp. 1 (D. Ore. 1973)................ 6,8,13

Dewey v. Reynolds Metals Co., 429 F.2d 324

(6th Cir. 1970)................................ 6

Eastern Greyhound Lines v. Division of HumanRights ____ F.Supp. ____ (1970) 2 FEP Cases

710 (1970)..................................... 6

Head v. Timken Roller Bearing Co., 486 F.2d

870 (6th Cir. 1973)............................ 16 15

Johnson v. U.S. Postal Service, 6 EPD [̂7740

(E.D. Ark. 1972)............................... 6

Kober v. Westinghouse, 480 F.2d 240 (3rd

Cir. 1973)............... -..................... 15

Kettell v. Johnson & Johnson, 337 F.Supp. 892

(E.D. Ark. 1972)............................... 6,9

Lea v. Cone Mills, 438 F.2d 86 (4th Cir. 1971)......... 15,17,18,19

Le Blanc v. Southern Bell Tel. & Tel. Co.,333 F.Supp. 602 (E.D. La. 1971) aff'd per

curiam, 460 F.2d 1228 (5th Cir. 1972)

cert. denied. 409 U.S. 990 (1972)............. 18

1

Manning v. International Union, 466 F.2d 812

(6th Cir. 1972)............................... 16

Moody v. Albemarle Paper Co., 474 F.2d 134(4th Cir. 1973)............................... 4,14,15

Newman v. Piggie Park Enterprises, Inc. 390 U.S.

400 (1968)................................... 19

Reid v. Memphis Publishing Co., 468 F.2d 346

(6th Cir. 1972).............................. 5,8,12

Page

r

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES TCont'dl

Page

Reid v. Memphis Publishing Co., ____ F.Supp.

____ (W.D. Tenn. 1973) Slip, op.............. 7 12

Riley v. Bendix Corp., 464 F.2d 1113 (5th Cir.

1972)........................................ 5,7,8,

Robinson v. Lorillard, 444 F.2d 791 (4th

Cir. 1971)................................... 18

Rowe v. General Motors Corp., 457 F.2d 342

(5th Cir. 1972)............................... 15

Schaeffer v. San Diego Yellow Cabs, Inc., 462

F . 2d 1002 (oth Cir. 1972)..................... 15

United States v. Georgia Power Co.., 474 F.2d 906

(5th Cir. 1973)............................... 15

Statutes and Regulations

Civil Rights Act of 1964, Title VII,

42 U.S.C. §§2000e et_ seq.................. 1

42 U.S.C. §2000e-(j)...................... 2,642 U.S.C. §2000e-2 (a)..................... 2,5

42 U.S.C. §2000e-5(g)..................... 1442 U.S.C. §2000e-5(k) Section 706(k)....... 17

Equal Employment Opportunities Commission

Guidelines On Religious Discrimination....

29 C.F.R. §1605.1(b)..................... 5

29 C.F.R. §1605.1(c)..................... 5

Page

t

- iii -

i

r

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

1. Whether Hermitage Cotton Mills' refusal to attempt

to accommodate the religious beliefs of plaintiff

violates Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act

where the evidence does not support a finding of

undue hardship as required by the EEOC guidelines

of July 10, 1967 on religious discrimination.

2. Whether the District Court Erred as a matter oflaw in stating that, even if injunctive relief is

ordered, "special circumstances" rendering back

pay and counsel fees inappropriate exist where

plaintiff sought actual employment worked all

shifts except his Sabbath and was subsequently discharged for his religious beliefs.

#

IV

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

NO. 73-1600

RAY E. ROBERTS,

Plaintiff-Appellant,

- vs -

HERMITAGE COTTON MILLS, Camden,South Carolina,

Defendant-Appellee.

On Appeal From The United States District Court

For The District of South Carolina

‘ Columbia Division

BRIEF FOR APPELLANT

Statement of the Case

This appeal involves a private employment discrim

ination suit under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of

1964, 42 U.S.C. §2000e et seq. The appellant, plaintiff

below, is a former employee at Hermitage Cotton Mills in

Camden, South Carolina. The appellee, defendant below, is

Hermitage Cotton Mills, a South Carolina corporation (textile

mill incorporated in South Carolina).

I. Proceedings Below

This action was commenced on November 15, 1972 within

thirty days of the issuance of a right-to-sue letter by the

Equal Employment Opportunity Commission pursuant to the

provisions of Title VII. The compjaint alleged that the

defendant, Hermitage Cotton Mills, discriminatorily discharged

plaintiff because of his religious beliefs in violation of

Title VII, 42 U.S.C. §§2000e-2(a) and 2000e(j). Plaintiff

prayed for injunctive relief against defendant as well as an

award of back pay, attorney's fees and costs.

On January 12,' 1972, defendant, Hermitage Cotton Mills

filed its answer acknowledging jurisdiction but denying any

liability to plaintiff. The case was tried on the merits

before Judge Sol Blatt on April 16, 1972, and an order dis

missing the case with costs assessed against plaintiff was

entered the same day. A timely notice of appeal was filed on

April 19, 1973, and the appeal was docketed in this Court on

February ll, 1974.

II. Statement of Facts

Plaintiff is and has been since 1967 a devoted adherent

to the Worldwide Church of God religious faith . (R. 23) which

requires him to abstain from working from sundown on Friday

2

until sunset Saturday (R. 26). Plaintiff, since his con

version to said faith has adhered strictly to this requirement.

Defendant Hermitage Cotton Mills manufactures tobacco

cloth (commonly known as cheese cloth), which is used in

hospitals as surgical gauze (R. 47, 98). In October 1969

defendant operated 6 days a week, three shifts per day from 10 p.m

Sunday through 10 p.m. Saturday. It employed approximately

400 persons in various job categories including 30 loom

fixers, 10 to a shift, who fix the weaving looms so thay can

make as perfect a cloth as possible (R. 37). In the plant there

were 10 set 3 of looms, each containing 92 looms; each set required

a loom fixer, a weaver and a battery filler. Although there

was a spare weaver and battery filler on each shift there was

no spare loom fixer (R*. 49) . All employees are paid time and

a half for all working hours over forty hours.

On Tuesday, October 21, 1969 plaintiff commenced employ

ment with defendant as a loom fixer working the third shift

(10 p.m. - 6 a.m.) on that date and on the following Wednesday

1/and Thursday (October 22 and 23) (R. 50). On Firday, October

24, 1969, plaintiff did not report to work for the third shift

(R. 34) due to the observance of his Sabbath. Defendant, after

being advised of plaintiff's religious beliefs, refused to

1/ Prior to his employment with defendant, plaintiff

had worked at another textile mill for 27 years as a loom-

fixer (R. 18) .

- 3

attempt to accommodate plaintiff (R. 26, 60). When plaintiff

refused to work after sundown the following Friday, he was

discharged (R. 57 ).

The district court found that the defendant made an

exceptionally strong case to show that it would have created

an undue hardship to provide employment for plaintiff; that

there was no way the employer could have made provision for

relief every Firday for fifty Fridays (R. Ill); and that there

was no evidence as to what would have actually happened if the

plaintiff and defendant worked together to determine if such

an arrangement could in fact be made (R. 113, 114). Therefore

the court directed defendant to reemploy plaintiff for a period

of two weeks to give plaintiff and defendant an opportunity

to find someone willing to work 50 Fridays for him or 4 hours

each Friday (R. 115) . However, the court held that even if an

injunction were to be issued at the end of this two week period,

plaintiff's prayer for back pay and attorney's fees would be

denied on grounds that the special circumstances described in

Moody v. Albemarle existed making such relief inappropriate.

Plaintiff, because he was by then employed by the South

Carolina Highway Department, refused this offer of temporary

re-employment. Consequently, the court dismissed the complaint.

4

A R G U M E N T

I .

THE DISTRICT COURT ERRED IN HOLDING THAT

DEFENDANT DID NOT VIOLATE TITLE VII OF THE

CIVIL RIGHTS ACT OF 1964 IN DISCHARGING

PLAINTIFF FOR HIS RELIGIOUS BELIEFS.

This case raises a question of religious discrimi

nation of first impression in this Court. It is controlled

by 42 U.S.C. §2000e-2(a) which prohibits employment dis

crimination based on religion and the EEOC July 10, 1967

guideline on religious discrimination, 29 C.F.R. Sec. 1605.1

which provides in part:

(b) The Commission believes that the duty

not to discriminate on religious grounds

required by section (703 (a) (1)) of the Civil

Rights Act of 1964, includes an obligation

on the part of the''‘■employer to make reasonable

accommodations to the religious needs of

employees and prospective employees where such accommodations can be made without undue

hardship on the conduct of the employer's

business. Such undue hardship, for example,

may exist where the employee's needed work

cannot be performed by another employee of

substantially similar qualifications during

the period of absence of the Sabbath observer.

(c) . . . the employer has the burden of

proving that an undue hardship renders the

required accommodations to the religious

needs of the employee unreasonable.

Courts have almost uniformly applied the EEOC guideline in

cases alleging religious discrimination arising since its

issuance. Riley v. Bendix Corp., 464 F.2d 1113 (5th Cir.

1972); Reid v. Memphis Publishing Co., 468 F.2d 346 (6th Cir

5

1972); Johnson v. U.S. Postal Service, 6 EPD [̂8984 (N.D.

Fla. 1973); Claybaugh v. Pacific Northwest Bell Telephone

Co., 355 F.Supp. 1 (D. Ore. 1973).

The EEOC's authority to issue this guideline was

challenged in some other cases where courts refused to apply

it. See Dewey v. Reynolds Metals Co., 429 F.2d 324 (6th Cir.

1970), aff'd by an equally divided Court, 402 U.S. 689 (1971);

Kettell v. Johnson & Johnson, 337 F.Supp. 892 (E.D. Ark. 1972),

Eastern Greyhound Lines v. Division of Human Rights ____ F.Supp.

____ (1970), 2 FEP Cases 710 (1970). However, any doubts as

to the effect to be given to these guidelines were laid to

rest by Congress on March 6, 1972 when the following provision

was added to the 1964 Civil Rights Act:

tThe term "religion" includes all aspects of

religious observance and practice, as well

as belief, unless an employer demonstrates

that he is unable to reasonably accommodate

to an employee's or prospective employee's

religious observance or practice without

undue hardship on the conduct of the employer's

business.

42 U.S.C. §2000e (j) .

The legislative history of the 1972 amendment makes

it clear that the EEOC guideline expressed the prior intention

of Congress. Senator Randolph, the sponsor of the amendment,

noting that the Supreme Court had divided evenly in Dewey v.

Reynolds Metals Co., supra, stated:

The amendment is intended, in good purpose, to resolve by legislation - and in a way I

think was originally intended by the Civil

Rights Act - that which the courts have not

resolved. 118 Cong. Rec. §228.

6

See also Riley v. Bendix Corp., supra, where the

Fifth Circuit had little difficulty finding the EEOC guide

lines valid as being a proper interpretation of the statute.

A . Defendant Did Not Attempt An Accommodation of

Plaintiff's Religious Beliefs As Required by

Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act and the

EEOC Guidelines-

The district court held that defendant made an excep

tionally strong case to prove or to carry the burden that iv.

would have created an undue hardship to provide employment

for plaintiff (R. Ill) . It also found that "all of the evi

dence and the undisputed testimony is to the effect that it

would have created an undue hards?nip and an undue burden on

the employer bach in 1969 to employ plaint iff"(R. 121). The

court then sets up what appears to be a direct contradiction

i

by stating that there is no evidence as to what would have

actually happened if plaintiff and defendant had worked to

accommodate plaintiff and had made work available for him

(R. 113).

The holding of undue hardship must be taken as the con

clusive one since it is necessary to support the award of

judgment for defendant. That award, however, was initially

made contingent upon the failure to work out an accommodation

during a two-week re-employment period which the court offered

plaintiff (R. 113-14). When plaintiff rejected this offer,

the court immediately entered judgment for defendant.

This offer of re-employment is critical, however, be

cause it evidences the trial court's uncertainty as to which

- 7 -

i

party carries the burden of making a reasonable accommodation.

The court stated, "The burden is to be on the plaintiff to

make every effort . . . (R. 115). It also said, "I want to

know (after the probationary period) what plan, if any, the

plaintiff has made, a workable 50-week plan, and one that

wouldn't create an undue hardship on defendant. And . . . I

want to know from the defendant what efforts it has made . . .

(R. 115). The most reasonable conclusion to be drawn here is

that the court believed that the burden is not entirely on

the defendant to attempt an accommodation. Plaintiff submits

that the trial court's requirement that plaintiff share the

burden of making a reasonable accommodation does not satisfy

the requirements of Title VII nor the EEOC guidelines.

Courts of other circuits have held that the EEOC

guideline by its very language places an affirmative duty upon

an employer to attempt an accommodation. Claybaugh v. Pacific

Northwest Bell Telephone Co., supra, at 5; Riley v. Bendix

Corp., supra. See Reid v. Memphis Publishing Co., supra.

In Claybaugh, a case where the employer discharged plaintiff

for his religious beliefs, the district court stated:

The burden is on the employer and not

the employee asking for an accommodation

to seek out the cooperation of other

employees if, as here, this would be a reasonable accommodation. 355 F.Supp. at 5.

* * *

The requirement upon an employer to make

a reasonable accommodation to the

religious needs of an employee is not

unbending. However, an employer cannot sustain its burden of showing undue hard

ship without first showing that it made an

accommodation as an attempted remedy. I_d. at 6.

8

that the employer did not demonstrate that he was unable to

reasonably accommodate to Riley's religious observance or

practice without undue hardship on the conduct of the

employer's business noted that:

. . . no "accommodation" of any kind was

made to permit Riley to be absent on Friday

evenings. . . . Nor was there any effort

made . . . to arrange for another person

to substitute for him during these hours.

464 F .2d at 1115.^

The district court found that defendant made no

affirmative effort whatsoever to accommodate plaintiff's

religious beliefs. Thus, the lack of any affirmative action

precluded the district court from making a finding of undue

hardship.

B . The Evidence Presented At Trial Does Not Support

The Trial Court's Finding of Undue Hardship.

The district court cited certain facts in support of

its holding of undue hardship. To illustrate the insuffi

ciency of these facts to support this holding as a matter of

law, we quote at length from the court's opinion:

The Fifth Circuit in Riley v. Bendix, supra, holding

2/ Even in Kettell v. Johnson & Johnson, supra. the dis

trict court, although refusing to apply the EEOC guidelines,

found that the defendant had made reasonable efforts to accom

modate to plaintiff's religious beliefs and that failure to take further affirmative action cannot be said to constitute dis

crimination. The court held that the EEOC guidelines went

beyond any legitimate interpretation of Title VII by placing the

burden upon the employer to-inflict upon itself some hardship to avlid a charge of discrimination; but it qualified its holding,

however, stating:

This is not to say that the Act, and particularly

the word "discriminate,cannot be interpreted to •

require some degree of affirmative accommodation.• ' ;.

Under the proper circumstances, failufe to reasonably accommodate may indeed be strong evidence .

of discrimination.* :

9

Some of the facts which have led the Court to

conclude that the employer has made such a

strong showing is that there has been testimony by the General Manager of the plant, and by

one of the shift supervisors, that based on

their expertise from years in this type of

work, and by the General Manager of a simi

larly situated plant, that it would have been

impossible to have accommodated the plaintiff.

And there has been no testimony by the plaintiff

to the contrary.

The Court is impressed with the fact that

there were thirty loom fixers, which is a

specialty in the mill of the defendant, and

that generally 50 percent of these employees

don't want to work on the weekends,vhich would

eliminate about half of the ones who would be

available to work in the place of the plaintiff.

There is further testimony that a 16-hour day

would be necessary for somebody to replace the

plaintiff and over a period of time that would

be injurious to the health of loom fixers who

are older people generally, and that it would

not be conducive to the maintenance of the

health of the person or persons who agree to

provide this 16 hours of steady work (R. 111-12).

However, the trial court itself and the testimony of witnesses

at trial was contradictory.

First, the trial court in its opinion stated:

I am going to direct that plaintiff and defend

ant, working together, to determine factually

rather than by opinion if such an arrangement

can be made and if relief can be given to the

plaintiff. . . (R.ill).

I realize that the expert testimony has been

given in good faith that it can't be done,

but sometimes things that you think can't

be done, if you try, work far better than

you anticipate (R.l 11).

Had the trial court been certain that the testimony was suffi

cient to support the conclusion, it would not have been nec

10

essary to postpone entering of a judgment to await the results

of plaintiff's and defendant's efforts to achieve accommo

dation .

Secondly, the testimony of defendant's witnesses leaves

open the question whether an accommodation was possible. Mr.

Hughes, the Superintendent of Weaving testified it was possible

to get someone to replace plaintiff sometimes but not on a

weekly basis. He reasoned that it "is too much to ask people

to double over fifty times a year" (R. 61). However, he also

testified that when a loom fixer is sick, his substitute works

a 16-hour day (R. 58-9), so apparently at least some loom fixers

are willing to work 16-hour days at the request of defendant.

Moreover, he stated that there was a replacement who was will

ing to work a day a week even though he didn't always want it

to be on Firday (R. 85).

The trial court's conclusion that fifty percent of the

loom fixers don't want to work on the weekend was drawn from

the testimony of the General Manager of the mill, Mr. Pitts,

who stated, "And there is no question in my mind that if we

let the people run the mill, I think 50 percent of them would

not show up on weekends, and a lot wouldn't come in on Friday

night? (R. 112). However, the defendants also stated that

they had not polled employees "in years" as to their willing

ness to work on weekends. ■

Finally, a generalization about the preference of

defendant's employees does not satisfy the EEOC guideline or

- 11 -

the developing judicial standards. Subsection (b) of the EEOC

guideline suggests that undue hardship may inhere in a lack

of substitutes with "substantially similar qualifications."

There is no indication in the record that all of the 30 loom

fixers are not fungible. In Reid v, Memphis Publishing Company,

supra, the employer's policy was to give senior employees their

preference of which days to work. This did not deter the

Court of Appeals from requiring defendant to attempt an

accommodation. 468 F.2d at 348. Nor did the district court

find on remand undue hardship where the employees in plaintiff's

category (copyreaders) had areas oi special expertise and hence

were not all interchangeable. F .Supp. _____, (W.D. Tenn.

3/December 17, 1973). Slip op. at 10-11.

C. The Evidence Does Support A Holding That A

Reasonable Accommodation Is Possible.

4/In 1969 the defendant's mill operated 6 days a week,

three shifts per day from 10 p.m. Sunday to 10 p.m. Saturday.

At the time of his discharge, plaintiff was working on the 10

p.m. to 6 a.m. Sunday night to Saturday morning shift. The

trial court in offering plaintiff temporary employment suggested

that it would only be necessary to find someone willing to work

4 hours for plaintiff on Fridays. Thus, a replacement would

3/ The district court also ruled that an accommodationwopld not necessarily involve undue hardship just because it

included assigning other employees, voluntarily or involuntarily,

to substitute for the plaintiff on his Sabbath. Id.

4/ At time of trial defendant operated on a 5 day week.

12

only have to work 12 hours at most during any season of the

year. In late spring and summer the replacement would only

5/have to work 9 hours due to the extra hours of sunlight.

Other possibilities exist presently in light of defendant's

shift to a five day work week. Plaintiff merely suggest that

alternatives are available and does not wish to usurp the

duty of defendant to make whatever accommodation is reasonable.

In sum, we submit that the testimony of defendant's

witnesses leaves undisputed the fact that no attempt was made

to accommodate plaintiff's beliefs; that their testimony does

not support a finding of undue hardship and that, as suggested

by the trial court, a reasonable accommodation was possible.

Therefore, the district court erred in holding that defendants

4did not violate Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act in dis-•H.

charging plaintiff for his religious beliefs.

II.

THE COURT BELOW ERRED AS A MATTER OF LAW IN

STATING THAT EVEN IF INJUNCTIVE RELIEF IS

ORDERED, SPECIAL CIRCUMSTANCES RENDERING BACK

PAY AND COUNSEL FEES INAPPROPRIATE EXIST HERE

Plaintiff sought as part of his remedy relief in the

form of attorney's fees and back pay for economic loss suffered

as a result of defendant's unlawful discriminatory practices.

The district court concluded that, as a matter of law, even

5/ . See Claybaugh v. Pacific Northwest Bell Telephone Co.,

supra. 355 F.Supp. at 5, n.8 where the court noted that "at least

during the winter months where on the Saturday evening shift an hour or less of post-sundown time was involved Bell could

have accommodated Claybaugh as it accommodated other employees

for these activities.

13

if it issued an injunction or passed an order requiring re

employment, special circumstances rendering back pay and

attorney's fees unjust and inequitable are present in this

case. The court assigned the following reasons in support

of its denial of back pay:

(1) Plaintiff knew of defendant's six-day work

week and did not inform defendant of his

religious beliefs at the time of hire;

(2) Plaintiff was knowledgeable about the issues

involved since prior to his employment he had

filed an EEOC charge two years earlier against

a former employer; and

(3) Thus plaintiff had baited a trap for defendant.

Plaintiff submits that the trial court's description of the

circumstances of the instant case is not the kind of special

circumstances this Court described in Moody v. Albemarle Paper

Co., 474 F.2d 134, 142 n.5 (4th Cir. 1973), which would render

back pay and attorney's fees inappropriate. Therefore, should

an injunction be issued, an award of back pay and attorney's

fees would be required under the present state of the law in

this circuit.

The relief provision in Title VII authorizes "the

court to enjoin the respondent from engaging in such unlawful

employment practice, and order affirmative action as may be

appropriate, which may include reinstatement or hiring of

employees, with or without back pay." 42 U.S.C. §2000e-5(g).

- '14 - •

This Court and other circuits have developed from this pro

vision the principle that back pay is an integral part of

injunctive relief which compensates the victim rather than

punishes the respondent and therefore courts should give wide

scope to the act in order to remedy the plight of victims of

employment discrimination. United States v. Georgia Power

Company. 474 F.2d 906, 921 (5th Cir. 1973); Rowe v. General

Motors Corp., 457 F.2d 348, 354 (5th Cir. 1972); Moody v.

Albemarle Paper Co., supra at 142. See also Bowe v. Colgate-

Palmolive Co.. 415 F.2d 711, 720 (7th Cir. 1969).

Hence in Moody v. Albemarle, supra, this Court gave

concrete meaning to the above stated principle of law while at

the same time limiting its application when it said:

Thus, a plaintiff or a complaining class who

is successful in obtaining an injunction under

Title VII of the Act should ordinarily be awarded

back pay unless special circumstances would

render such an award unjust. 474 F.2d

at 142.

See also, Head v. Timken Roller Bearing Co., 486 F.2d 870,

877 (6th Cir. 1973).

This Court in Moody and the other courts which have

adopted the "special circumstances" exception to the award of

back pay have cited only cases involving female protective

statutes as examples of proper application of this rule of

law. See Albemarle v. Moody, supra, citing Schaeffer v. San

Diego Yellow Cabs, Inc., 462 F.2d 1002 (9th Cir. 1972); Lea

Blanc v. Southern Bell Te. & Tel. Co., 333 F.Supp. 602 (E.D.

La. 1971)'; aff'd per curiam, 460 F.2d 1228 (5th Cir. 1972),

15

cert, denied, 409 U.S. 990 (1972); Accord the Sixth Circuit

in Head v. Timken Roller Bearing Co., supra, at 877 n.10

citing Manning v. International Union, 466 F.2d 812 (6th Cir.

1972) and the Third Circuit in Kober v. Westinghouse, 480

F.2d 240 (3rd Cir. 1973). The rationale behind these decisions

is that where unlawful discrimination is shown but the employer's

practices were compelled by a state law in conflict with Title

VII, there is no abuse of the trial judge's discretion in deny

ing back pay. Kober v, Westinghouse, supra, 480 F.2d at

246-48.

The instant case has none of the trappings of the cases

cited by this Court and other circuit courts a_ involving

"special circumstances." Thus, the district court would have

tthis Court expand the circumstances under which a trial judgeH.

may deny back pay to include situations where plaintiff seeks

employment with the knowledge that he might be discriminated

against by defendant. In such cases, says the district court,

even though unlawful discrimination occurs back pay should be

denied because plaintiff lured ("baited a trap") defendant into

violating plaintiff's rights. However, the evidence does not

support the trial court's conclusion. When plaintiff approached

defendant, he was seeking actual employment. Although he did

6/not reveal his religious beliefs to defendant, it is of no

6/ Q. ' And you withheld evidence on the fact that you would

not work on Friday night from him?

A. No sir; nobody asked me.

* * * * * * * * *

If he had asked me I would have told him the whole

truth (R. 68).

16

consequence since defendant made it clear that he would not

have hired plaintiff had he been aware of his religious beliefs.

Thus, this case is unlike Lea v. Cone Mills Coro..

438 F.2d 86 (4th Cir. 1971) where this Court affirmed a denial

of back pay citing the trial court's findings (1) that

plaintiff's primary motive was to test defendant's employment

practices rather than seek actual employment and (2) that there

was no vacancy of any type at the time plaintiff applied fcr

employment. Ld. at 87-8. As stated above, plaintiff sought

actual employment, was hired and worked all shifts except his

Sabbath during his ten day employment period.

With regard to attorney's fees, they are to be awarded

as one of the remedies available to the courts as a means of

fostering enforcement *of Title VII by private litigants. In

§706(k) 42 U.S.C. §2000e-5(k), Congress provided that plaintiffs

should receive an award of "reasonable" attorney's fees as part

of the costs allowed to them. Congress realized that such a

provision would encourage effectuation of Title VII rights by

the private sector on behalf of those who would not ordinarily

be able to hire an attorney by their own means. The district

court, however, found that because of the "special circumstances"

of this case, counsel fees would be denied even if injunctive

relief was granted. Plaintiff submits that no special cir

cumstances exist and should an injunction be issued an award

of attorney's fees is required by the precedents of this

Court.

17

The instant case is controlled by this Court's decisions

in Lea v. Cone Mills, supra, and Robinson v. Lorillard, 444 F.2d

791 (4th Cir. 1971) where Judge Sobellof stated:

In Lea v. Cone Mills [supra] we noted that

under Title II of the Civil Rights Act of

1964, attorney's fees are to be imposed not

only to penalize defendants for pursuing

frivolous arguments, but to encourage indi

viduals to vindicate the strongly expressed

congressional policy against racial discri

mination. The appropriate standard, therefore,

is that expressed by the Supreme Court in

Newman v. Piggie Park Enterprises, 390 U.S. 400,

432 88 S.Ct. 964, 19 L.ed 2d 1263 (1968):

"It follows that one who succeeds in obtaining

an injunction under that Title should ordinarily

recover an attorney's fee unless special circum

stances would render such an award unjust."

[Emphasis <udded]

Id. at 804. Above, we have dealt with the trial court's

trefusal to award back pay; for the same reasons given, supra,

pp. 16-17, no "special circumstances" exist which would justify

the trial court's position with regard to attorney's fees.

Furthermore, we note that in Lea v. Cone Mills, supra,

this Court ordered that attorney's fees be awarded notwith

standing the fact that it agreed with the lower court that

plaintiffs' primary motive was to test defendant's employment

practices. 438 F.2d at 88. The instant case is far removed

from the difficult question of whether attorney's fees should

1/be awarded in test cases, plarntiff here presents no such

7/ . Attorney's fees have even been awarded in cases involving

what this Court has described as "special circumstances" in Le

Blanc v. 'Southern Bell Tel. & Tel. Co., supra; the district

court stated:

18

extraordinary situation.

Thus, to deny plaintiff counsel fees is to penalize

him for seeking vindication of his rights in the only forum

available to him. More importantly, plaintiff has performed

the public function of furthering the Congressional policy

against religious discrimination as embodied in Title VII.

Plaintiff acted within the purposes set forth as basis for

compensation in Newman v. Pigcpie Park Enterprises, Inc., supra,

and Lea v. Cone Mills, supra and therefore, the district

court had no valid reason for denying plaintiff counsel fees.

#

7J [Cont'd]

The Courts have uniformly awarded attorney's

fees in these cases even where the prevailing

party was unable to recover back pay or other

damages because the defendant was relying in

good faith on a state statute. 333 F.Supp.

at 6 1 1 . . .

19

C O N C L U S I O N

The district court order should be reversed and

the case remanded for injunctive relief for plaintiff, back

pay and attorney's fees.

Respectfully submitted,

MITCHELL & JOE

4 Nona street

Greenville, South Carolina 29601

JACK GREENBERG

CHARLES S. RALSTON

MORRIS J. BALLER

Arthur c. McFarland10 Columbus Circle Suite 2030

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Plaintiff

- ' 2 0 • -

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I hereby certify that I have this day of March,

1974, served a copy of the above Brief for Appellant upon

the attorney for appellee, G. Thomas Cooper, Jr., Esq., by

mailing sane to him at his office at P. 0. Box 656, Camden,

South Carolina 29020, postage prepaid.

for Appellant