LDF Article on Charlie Taite

Press

January 1, 1981 - January 1, 1981

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Bozeman & Wilder Working Files. LDF Article on Charlie Taite, 1981. 58c05605-ef92-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/7e22c750-ba6e-4c28-9e35-3adece224b61/ldf-article-on-charlie-taite. Accessed February 04, 2026.

Copied!

One Man's

Struggle Against

Racial Injustice

In Florida

"I don't mind fightin'; I

come up fishtin'; I been

doing this all my life."

"At some point, J,ou going to have to moke some changes."

Novelist Joseph Conrad once wrote, "White men looked on [black] life as a mere

play of shadows. A play of shadows the dominant race could walk through unaf-

fected. . . ." Although Conrad was describing life in the Caribbean, he could just as

well have been w,riting about the world of the Deep South into which Charlie Taite

was born 65 years ago. Black people were expected to stay in the background, com-

ing forth only when whites needed them and never complaining about their lot in life.

But Charlie Taite, who lives in Pensacola, Florida, is a black man who never did

"know his place." From his youth, when it rvas downright dangerous for a black to

stand up for his rights, to the present, when racism in the South is no less viru-

lent for having become more subtle, Charlie Taite has been unable to accept the

idea that "that's just the way things are."

Today, with the help of the Legal Defense Fund

(LDF), Charlie Taite is one of the plaintiffs in a major

voting rights suit against the city of Pensacola and

surrounding Escambia County, where.white manip-

ulation of the election system has thwarted the

hopes of virtually every black candidate

for office, including Charlie

Taite, whose

story is told

inside.

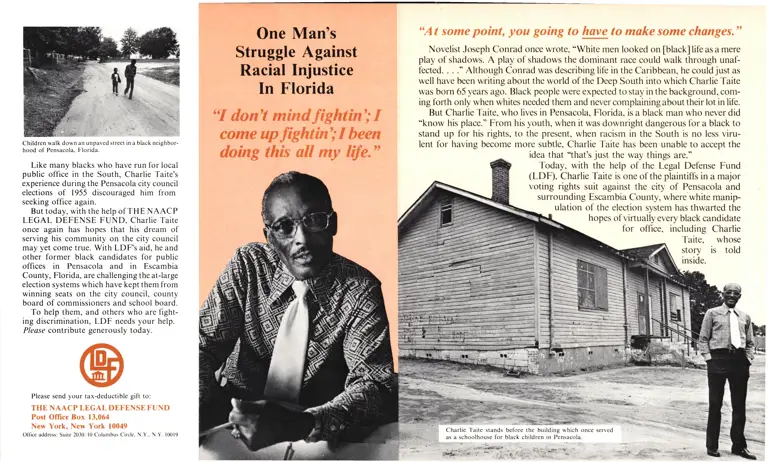

Children walk down an unpaved street in a black neighbor-

hood of Pensacola. FIorida.

Like many blacks who have run for local

public office in the South, Charlie Taite's

experience during the Pensacola city council

elections of 1955 discouraged him from

seeking office again.

But today, with the help of THE NAACP

LEGAL DEFENSE FUND, Charlie Taite

once again has hopes that his dream of

serving his community on the city council

may yet come true. With LDF's aid, he and

other former black candidates for public

offices in Pensacola and in Escambia

County, Florida, are challenging the at-large

election systems which have kept them from

winning seats on the city council, county

board of commissioners and school board.

To help them, and others who are fight-

ing discrimination, LDF needs your help.

Please contribute generously today.

Please send your tax-deductible gift to:

TtlE NAA(IP LEGAL DhI"E\St. F t.NI)

Post Office Box I3.064

New York. New York 10049

OlTice address: Suite 2010, I0 Columbus Circle. N.Y.. N.Y. 10019

Charlie Taite stands

as a schoolhouse for

, 1.*'.J*i".

ivi;i*i';.< .: * .:

black children in Pensacola.

'I

Born near Grove Hill. Alabama. Charlie

Taite was five years old when his tamily

moved to Pensacola. Florida, in 1918. It

was a time of unprecedented violence by

whites against blacks in Florida. where from

1900 to 1930 the lynching rate was the high-

est in the South. Eight blacks were burned

alive between l9l8 and 1927. and white

mob violence against blacks reached its peak

during the 1920 elections. When a promi-

nent black citizen of Ocoee, near Orlando.

attempted to vote, whites went on a ram-

page through the black neighborhood,

burning 20 houses. two churches. a school

and a lodge hall. Thirty-two to thirty-five

blacks died during this race riot.

jus( alx'a.t's' been curious lo a.s'A

questiotts. ll'he n I v'u\ u bo.t'. tt'( u\ed

ltt ,gti itt t itt' ilrltr' \[o] (', ttttd ,,,t'.t' itutl

lutt<'h cotltlt(r\ | ltart. J ri'rtr?, !"' i'tl "' 1,.'.'

I t'rtttltirt ! (ul thtrc. !'d usi x'lt)' I

couldn'l go lo the .school neuresl nr.t'

house instead oJ'nr-t' all hlac'k school.

I even osked x'h_t' there w'es a hlack

church and a w'hite church."

Charlie Taite was l2 when his stepfather

died. and since his mother's health was

bad, he dropped out of school to help sup-

port her. his sister and three younger

brothers. Holding a variety ol- jobs. from

water boy at a sawmill to longshoreman at

the Pensacola docks. he applied I'or a job as

a WPA worker in 1937 and u'as accepted.

"l'rtt rro( ,t4oitr,g lo he :ulis.l'itd lo tt'rtrk

here urtd the x'ltilt'ntun,q(t ull (he cus.t'

x'ork und x't' gt'l tltt' hard x'ork."

u'ere laborers and never had the easier jobs.

'I-he supervisor asked him if he realized

where he was in the South - and then

said. "Niggers just don't ask white men

questions." Charlie lost his temper and

grabbed the supervisor. who had him fired

on the spot without a hearing.

Charlie demanded to know who he could

u'rite in Washington. and soon sent a letter

to the head of the WPA. Within two weeks.

he got a hearing and was rehired.

But Charlie continued to have trouble

r,r'ith his white supervisors and was trans-

ferred from one job to another because ol'

his complaints about inequalitl,. His con-

Ilicts with the white power structure in the

WPA did not end until he lcli to servc in the

military during World War II. When he re-

turned to Pensacola. Charlie took a cir,il

serr,ice job at the nearby Naval Air Station.

Here. too. Charlie Taite's refusal to sit still

1'or discrimination resulted in numerous

confrontations with his bosses. who I'inally

managed to have him fired in 1954 after

I 2 years of service.

In 1955. Charlie Taite became the first

black man in history to run for the city

council of Pensacola. At that time. members

of the city council were elected by voters

in their own districts. rather than all voters

in the city at large. His bid for office pitted

hirn against retired Admiral C.P. Mason.

who was also the mayor of Pensacola.

Charlie could raise no more than $300

for his campaign, but he knocked on every

door in his district. including the white

houses. On election day. the white estab-

lishment was shocked at the large numbers

of blacks turning out, and a local radio

station urged whites to get to the polls or

they would "wake up Wednesday morning

with a black man on the city council."

'Ihe1' ncarll, did. Charlie lost by a narrow

margin. and there is suspicion of irregularity

in the counting of the ballots. Soon after-

ward, to nrake the election ol'a black nearly

impossible. the citv switched to an at-large

clection systern. which is today being chal-

lenged in l'edcral court by LDF.

i itt , iiiit! i !t ti(' i. (' \ I I IiI d i t ;!

This was when he first began to have

serious conflicts with his white bosses.

Some of the WPA jobs rvere easy ones, and

Charlie asked his superl'isor (all super-

visors were white, of course) why all blacks