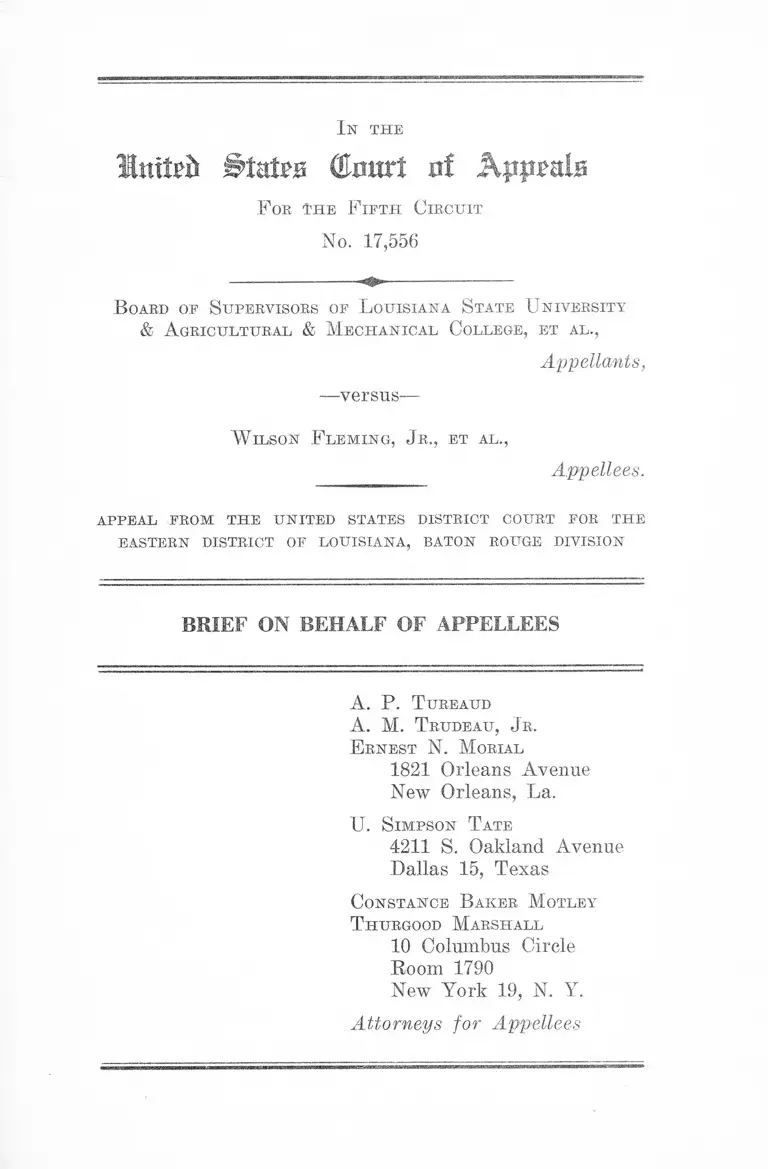

Board of Supervisors of Louisiana State University & Agricultural & Mechanical College v Wilson Fleming Jr. Brief on behalf of Appellees

Public Court Documents

March 4, 1959

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Board of Supervisors of Louisiana State University & Agricultural & Mechanical College v Wilson Fleming Jr. Brief on behalf of Appellees, 1959. 848658ce-bb9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/7e3a2de3-3de4-43a7-ba6b-fc7972e90013/board-of-supervisors-of-louisiana-state-university-agricultural-mechanical-college-v-wilson-fleming-jr-brief-on-behalf-of-appellees. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

In the

Ittt&ft (ta rt nf Appeals

F ob the F ifth Circuit

No. 17,556

B oard of Supervisors of L ouisiana State U niversity

& A gricultural & M echanical College, et al.,

Appellants,

•—versus—

W ilson F leming, Jr., et al.,

Appellees.

appeal from the united states district court for the

EASTERN DISTRICT OF LOUISIANA, BATON ROUGE DIVISION

BRIEF ON BEHALF OF APPELLEES

A . P. T ureaud

A . M. T rudeau, Jr.

E rnest N. M orial

1821 Orleans Avenue

New Orleans, La.

U. S impson T ate

4211 S. Oakland Avenue

Dallas 15, Texas

Constance B aker M otley

T hurgood M arshall

10 Columbus Circle

Room 1790

New York 19, N. Y.

Attorneys for Appellees

In the

U n i t e d © m i r ! u f A p j t e a L a

F or the F ifth C ircuit

No. 17,556

B oard of S upervisors of L ouisiana State U niversity

& A gricultural & Mechanical College, et al.,

Appellants,

—versus—

W ilson F leming, Jr., et al.,

Appellees.

APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE

EASTERN DISTRICT OF LOUISIANA, BATON ROUGE DIVISION

BRIEF FOR APPELLEES

Statement o f the Case

In addition to the facts set forth in appellants’ brief

under their Statement of the Case, appellees bring to the

attention of this court the following facts appearing in the

record.

Appellees, who were plaintiffs below, are Negro citizens

and residents of Louisiana who possess all of the requisite

qualifications for admission to a branch of Louisiana State

University now located in the City of New Orleans (R.

34). Prior to instituting suit in the court below, and dur

ing the period of registration for the school year 1958-

1959, each appellee duly made application for admission

2

to said institution, after complying with the rules and

regulations governing admissions of students (R. 34).

Their applications for admission were first rejected by

a letter from appellee W. R. Burleson, registrar of the

institution, which, after acknowledging receipt of the ap

plications, stated as follows:

The policy of the Board of Supervisors of Louisiana

State University and Agricultural and Mechanical Col

lege as Administrators of the Louisiana State Uni

versity in New Orleans, does not permit your admis

sion (R. 34).

Thereafter, appellees asked for clarification of the word

“policy” referred to in said letter. In reply thereto, ap

pellees were advised by letter, again written by the regis

trar, as follows:

In answer to your inquiries contained in your letter

of June 13, 1958, please be advised that your applica

tion for admission to the Undergraduate School of

L. S. U. in New Orleans * * * was not accepted as

Negroes are not admitted to said school under the laws

of the State of Louisiana and the policy of the Board

of Supervisors of Louisiana State University and Agri

cultural and Mechanical College (R. 35, emphasis ours).

At the time appellants refused the admission of these

appellees, white students were being accepted as students

at the same institution (R. 35).

Appellees’ complaint was filed in the court below on

July 29, 1958 (R. 2). On August 27, 1958 appellees filed

a motion for preliminary injunction enjoining appellants

from denying appellees and members of their class ad

mission to the undergraduate classes (R. 15). On the next

day, upon consideration of appellants’ motion for an addi

3

tional 45 days in which to file an answer, the court below

entered an order granting appellants an additional 20 days

in which to answer or otherwise move with respect to the

complaint (B. 15). On the same date, the court below set

September 3, 1958 as the date of hearing the motion for

preliminary injunction (E. 17).

Thereafter, on September 3, 1958 the registrar, W. E.

Burleson, filed an affidavit alleging that one of the plain

tiffs, Jamesetta, Henley, was not entitled to admission be

cause of the grades which she received while attending

Dillard University (E. 17-18). An affidavit was also filed on

September 3, 1958 by Homer L. Hitt, Dean of the insti

tution, to the effect that none of the plaintiffs had appealed

to him the ruling of the registrar denying his or her ad

mission (E. 18-19). An affidavit was likewise filed on the

same date by Albert L. Clary, Jr., registrar of Louisiana

State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College

to the effect that the registrar of the University in New

Orleans is responsible to the Director of Student Services

at Louisiana State University in New Orleans who, in turn,

is responsible to the Dean of Louisiana State University

in New Orleans; the Dean of Louisiana State University

is responsible to the Dean of the University for academic

matters, including admissions; and an applicant for ad

mission to Louisiana State University in New Orleans

has a right to appeal through the channels thus indicated

(E. 19-20).

Affidavits of three plaintiffs were filed on September 3,

1953 setting forth facts regarding residence, race, applica

tion for admission, and rejection of application by the

registrar (E. 20-27).

On September 3, 1958 when the motion for preliminary

injunction came on for hearing, defendants also filed their

opposition to the motion alleging that 1) the Board of

4

Supervisors of Louisiana State University is immune from

suit; 2) a single judge is without jurisdiction under 28

United States Code 2281; 3) proper notice had not been

given the Governor as required by 28 United States Code

2284; and 4) the suit is premature in that plaintiffs have

not exhausted administrative remedies. The Board of Su

pervisors also filed a motion to dismiss on the ground that

it is immune from suit (R. 28-31). The court below there

upon continued the hearing on the motion for preliminary

injunction until September 8,1958.

On September 8,1958 the first named plaintiff, Jamesetta

Henley, moved the court below for an order withdrawing

her name as a plaintiff in the action which was duly granted

(R. 33). Wilson Fleming, Jr., was the second named plain

tiff and, consequently, the style of this case was changed

accordingly.

On the same date, the court below entered an order

granting the motion for preliminary injunction, supported

by its findings of fact and conclusions of law (R. 33-38).

By this injunction, appellees were enjoined, pending the

determination of the action, “ from refusing on account

of race or color to admit plaintiffs, and any other Negro

citizens of the State similarly qualified and situated, to

the Undergraduate School of Louisiana State University

in New Orleans” (R. 37-38).

Thereafter, on September 11, 1958, appellants filed their

answer (R. 39-43). By their answer, they again claimed

the immunity of the Board of Supervisors from suit (R.

40). However, they admitted the allegations of the com

plaint in Paragraph V, Sub-paragraph 9 (R. 8-9) to the

effect that the registrar, W. R. Burleson, while acting in

his official capacity, wrote to appellees that “ Negroes are

not admitted to the said school under the laws of the State

of Louisiana and the policy of the Board of Supervisors

5

of Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Me

chanical College” (R. 42).

On September 19, 1958 following the filing of their

answer, defendants filed their Notice of Appeal to this

court from the order of September 8, 1958 granting the

preliminary injunction (R. 45).

Upon this appeal, appellants specify only two errors:

first, that suit against the Board of Supervisors of Louisi

ana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical

College is prohibited by the 11th Amendment to the United

States Constitution as the Board is an agency of the State

of Louisiana, and second, that the court below could not

entertain this suit since the plaintiffs had not exhausted

administrative remedies available to them (Appellants’

Brief, p. 4).

A R G U M E N T

I.

Suit against the Board o f Supervisors is not prohibited

by the 11th Amendment, nor is the Board entitled to

sovereign immunity, where the facts alleged or proved

show that the laws or policy under which the Board acted

is unconstitutional.

This court, in the case of Orleans Parish School Board

v. Bush, 242 F. 2d 156 (1957), gave special consideration

to the claim which has been repeatedly made by school

officials of the State of Louisiana in school segregation

cases that such officials are immune from suit under the

doctrine of sovereign immunity and that suit against them

is prohibited by the 11th Amendment to the Constitution

of the United States. In that case this court concluded that

the question had been foreclosed by the decision of the

6

Supreme Court of the United States in the School Segrega

tion Cases where actions of the same type as this one

were before that Court (at 160-161). However, because

the state officials in that case so strongly urged upon this

court their contention that that suit was in fact a suit

brought by citizens of the State of Louisiana against the

State, this court reviewed again, at great length, the theory

applicable to cases of this kind (at 160-161).

As in the Bush case, this suit does not seek to compel

state action. “ It seeks to prevent action by state officials

which they are taking because of the requirements of a

state constitution and laws challenged by the plaintiffs

as being in violation of their rights under the Federal

Constitution. If in fact the laws under which the Board

here purports to act are invalid, then the Board is acting

without authority from the State and the State is in no

wise involved” (at 161). Here the complaint alleges, the

answer admits, and the court below found as a fact that

“Negroes are not admitted to the said school under the

laws of the State of Louisiana and the policy of the Board

of Supervisors of Louisiana State University and Agri

cultural and Mechanical College” (R. 9, 42, 35).

That the laws and policy referred to are invalid and un

constitutional is a proposition too well settled to require

citation. And appellees do not understand appellants to

claim their validity under the Constitution and laws of the

United States. This case is, therefore, squarely within the

holding of this court in the Bush case on the question of

sovereign immunity and the effect of the Eleventh Amend

ment in suits brought against state officers to enjoin un

constitutional action.

However, appellants, without mentioning the Bush case,

seek to distinguish the instant case on the ground that there

is involved here a state corporation or agency as dis

7

tinguished from a state officer or individual. Appellants

properly concede at the outset of their argument that their

alleged distinction has already been held to be without

foundation in law by the Fourth Circuit in School Board

of City of Charlottesville v. Allen, 240 F. 2d 59 (1956).

In that case the Fourth Circuit said, as appellants point

out,

If high officials of the state and of the federal gov

ernment, * * * may be restrained and enjoined from

unconstitutional action, we see no reason why a school

board should be exempt from such suit merely because

it has been given corporate powers. A state can act

only through agents; and whether the agent be an

individual officer or a corporate agency, it ceases to

represent the state when it attempts to use state power

in violation of the Constitution and may be enjoined

from such unconstitutional action (at 63).

Although the question was not raised in the School

Segregation Cases, as appellants point out, the question

has been raised in the United States Supreme Court and

disposed of contrary to the contention of appellants.

In Sloan Shipyard Corp. v. United States Shipping

Board Emergency Fleet Corporation, 258 U. S. 549, the

Supreme Court squarely held that “ * * # it cannot matter

that the agent is a corporation rather than a single man”

(at 567). The Court then proceeded to give its reasoning

therefor: “ The meaning of incorporation is that you have

a person, and as a person one that presumably is subject

to the general rules of law” (at 567).

In addition, as the Fourth Circuit also pointed out in the

Charlottesville case, supra, although the question was not

specifically raised in the School Segregation Cases, “ * * *

it is not reasonable to suppose that the Supreme Court

8

would have directed injunctive relief against school boards

acting as state agencies, if no such relief could be granted

because of the provisions of the Eleventh Amendment to

the Constitution” (at 63).

II.

Administrative remedies need not be exhausted where

there is a law or policy o f excluding Negroes.

In the court below, appellants, by the affidavits of Homer

L. Hitt, Dean of Louisiana State University at New Or

leans, and Albert L. Clary, Jr., registrar of Louisiana

State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College,

sought to establish that there is a chain of command, in

volving at least three persons, to whom appellants could

have appealed the ruling of W. K. Burleson, the registrar

of Louisiana State University at New Orleans. This chain

of command did not include the Board of Supervisors, but

if appellants are correct, then after having appealed to

these three persons, logically, appellees would then be re

quired to appeal a fourth time to the Board of Supervisors.

However, despite appellants’ efforts to conjure up an al

leged administrative remedy there is in fact no such “pre

scribed” administrative remedy. Myers v. Bethlehem Ship

building Corp., 303 U. S. 41, 51. If there were, appellants

would have offered in evidence the rules and regulations

governing such appeals.

But even if it could be said that there is a “prescribed”

administrative remedy which appellees should have ex

hausted prior to invoking jurisdiction of the court below,

to require them to do so when “ Negroes are not admitted

to said school under the laws of the State of Louisiana and

the policy of the Board of Supervisors” would, as this court

pointed out in the Bush case, supra, “be a vain and useless

gesture, unworthy of a court of equity, # # # a travesty in

9

which this court will not participate” (at 162). See also,

Gibson v. Board of Public Instruction of Dade Coirnty, 246

F. 2d 913 (5th Cir., 1957); Holland v. Board of Public

Instruction of Palm Beach County, 258 F. 2d 730 (5th Cir.,

1958); Kelley v. Board of Instruction of the City of Nash

ville, 159 F. Supp. 272 (M. D. Tenn. 1958).

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, the order appealed from

should be affirmed.

Respectfully submitted,

A. P. T ureaud

A. M. T rudeau, Jr.

E rnest N. M orial

1821 Orleans Avenue

New Orleans, La.

U. S impson T ate

4211 S. Oakland Avenue

Dallas 15, Texas

Constance B aker M otley

T hurgood M arshall

10 Columbus Circle

Room 1790

New York 19, N. Y.

Attorneys for Appellees

10

Certificate of Service

I hereby certify that on this 4th day of March, 1959, I

served copies of the foregoing Brief for Appellees on the

following counsel for Appellants: Jack P. F. Gremillion,

Attorney General, State of Louisiana, Baton Rouge, Loui

siana and William P. Schuler, Asst. Attorney General, State

of Louisiana, 301 Loyola Avenue, New Orleans, Louisiana,

by mailing a copy of each to them, via United States mail,

postage prepaid.

Constance B aker M otley

Attorney for Appellees

3 8