Hayden v. Pataki Plaintiffs' Memorandum of Law in Opposition to Defendants' Motion for Judgment on the Pleadings

Public Court Documents

September 9, 2003

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Hayden v. Pataki Plaintiffs' Memorandum of Law in Opposition to Defendants' Motion for Judgment on the Pleadings, 2003. 4c0608d5-b79a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/7e4c8509-bdb1-436d-90d4-e061de2098c8/hayden-v-pataki-plaintiffs-memorandum-of-law-in-opposition-to-defendants-motion-for-judgment-on-the-pleadings. Accessed February 17, 2026.

Copied!

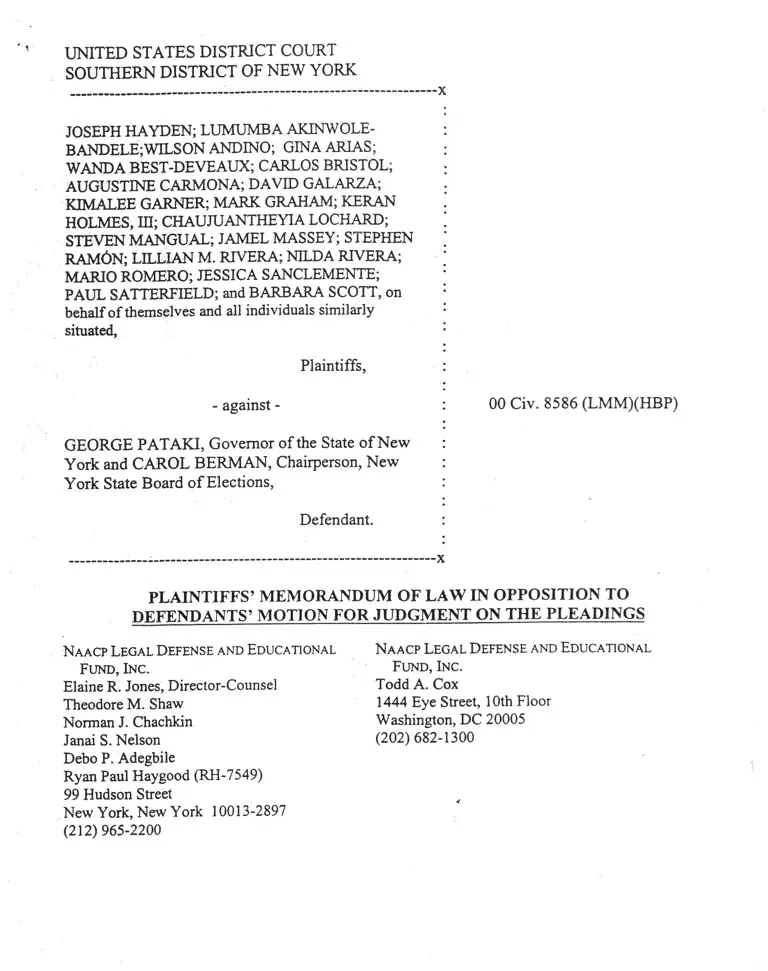

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK

JOSEPH HAYDEN; LUMUMBA AKJNWOLE- :

BANDELE;WILSON ANDINO; GINA ARIAS; ;

WANDA BEST-DEVEAUX; CARLOS BRISTOL; :

AUGUSTINE CARMONA; DAVID GALARZA; .

KIMALEE GARNER; MARK GRAHAM; RERAN !

HOLMES, HI; CHAUJUANTHEYIA LOCHARD; ]

STEVEN MANGUAL; JAMEL MASSEY; STEPHEN

RAMON; LILLIAN M. RIVERA; NILDA RIVERA; ;

MARIO ROMERO; JESSICA SANCLEMENTE;

PAUL SATTERFIELD; and BARBARA SCOTT, on

behalf o f themselves and all individuals similarly

situated, •

Plaintiffs, :

- against -

GEORGE PATAKI, Governor o f the State o f N ew

York and CAROL BERMAN, Chairperson, New

York State Board o f Elections,

Defendant.

00 Civ. 8586 (LMM)(HBP)

PLA IN TIFFS’ M EM ORANDUM OF LAW IN O PPO SITIO N TO

D EFEN D A N TS’ M OTION FOR JU D G M EN T ON THE PLEADINGS

Naacp Legal Defense and Educational

Fund, Inc .

Elaine R. Jones, Director-Counsel

Theodore M. Shaw

Norman J. Chachkin

Janai S. Nelson

Debo P. Adegbile

Ryan Paul Haygood (RH-7549)

99 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10013-2897

(212) 965-2200

Naacp Legal Defense and Educational

Fund, Inc.

Todd A. Cox

1444 Eye Street, 10th Floor

Washington, DC 20005

(202) 682-1300

Community Service Society of New York

Juan Cartagena (JC-5087)

Risa Kaufman

105 E. 22nd Street

New York, NY 10010

(212)260-6218

Center for Law and Social Justice

at Medgar Evers College

Joan P. Gibbs

Esmeralda Simmons

1150 Carroll Street

Brooklyn, NY 11225

(718) 270-6296

Attorneys for Plaintiffs Joseph Hayden; Lumuba Akinwole-Bandele; Wilson Andino; Gina Arias; Wanda

Best-Deveaux; Carlos Bristol; Augustine Carmona; David Galarza; Kimalee Garner; Mark Graham;

Keran Holmes, III; Chaujuantheyia Lochard; Steven Mangual; Jamel Massey’; Stephen Ramon; Lillian

M. Rivera; Nilda Rivera; Mario Romero; Jessica Sanclemente; Paul Satterfeld; and Barbara Scott, on

behalf of themselves and all individuals similarly situated.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PRELIMINARY STATEM ENT.......................................................................................................... 1

BACKGROUND FACTS.......................................................................................................................2

STANDARD OF REVIEW ................................................................................................................... 3

ARGUMENT.............................................................................................................................................5

I. Richardson v . Ramirez Does Not D ispose of

Plaintiffs’ Constitutional Cla im s .................................... .......5

II. Plaintiffs’ Amended Complaint Sufficiently Alleges a Claim For

Intentional Discrimination Under The Equal Protection Clause of

the Fourteenth Amendment and under the Fifteenth Amendment..................... 7

A. The Amended Complaint Contains Facts Sufficient To Satisfy

The Standard for Alleging Discriminatory Intent Under ih e

Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment as

Articulated by the Supreme Court............................................................... 8

1. New York's Extensive History of Intentional Racial Discrimination

In Voting Dates As Far Back As The State's Provisional Constitution

Regarding Suffrage.................................................................................... 10

2. The Allegations Contained In The Amended Complaint Are More

Detailed And Specific Than The Allegations In The Complaint

Submitted In Hunter...................................................................................18

III. The Amended Complaint Sufficiently States A Claim That Defendants’ Non-

Unform Practices Disfranchising Persons Convicted Of A Felony Violate The

Equal Protection Clause Of The Fourteenth Amendment.....................................21

A. The Application Of Strict Scrutiny Is Appropriate He r e .......................21

B. New York Election Law §5-106(2) Fails Strict Scrutiny Analysis

Because It Is Not Narrowly Tailored To The State's Interest ............23

C. Even If Rational Basis Scrutiny Is Applied, New York Election Law

§5-106(2) Fails Constitutional Rev fw Because It Is Irrational And

Arbitrary ............................................................................................................24

IV. The Amended Complaint Sufficiently States A First Amendment Claim On

Behalf Of Persons Who Are Incarcerated Or On Parole......................................26

A. New York's Disfranchisement Laws Impose A Severe Restriction

On The Right To Vo t e ........................................................................................26

Page

B. Defendants Erroneously Interpret Green and Richardson To

Foreclose A First Amendment Challenge To Felon

Disfranchisement Laws .................................................................................... 22

V. The Court Has Subject Matter Jurisdiction To Hear Plaintiffs’ Claim Under

The Civil Rights Acts Of 1957 and 1960, And Plaintiffs Have Standing To

Assert Such A Cl a im ................................................................................................ 29

A. Section § 1971 Impliedly Creates A Private Right Of Action Under

Which Plaintiffs May Challenge Defendants’ Unlawful

Discrimination Against Black And Latino Felons....................................30

B. In Addition And In The Alternative, Plaintiffs May Bring

A Claim For Defendants’ Violation of 42 U.S.C. §1971

T h r o u g h 42 U.S.C. §1983.................................................................................... 32

C. Section 1971 Can Reach Challenges To D iscriminatory Voting

Qualifications................................................................ 33

VI. The Amended Complaint Sufficiently States A Claim That §5-106(2) A n d

Article II, §3 Of The New York State Constitution Violate Customary

International La w ..................................................... 3^

A. The Court Has Subject Matter Jurisdiction To Hear

Plaintiffs’ Claims As The Law Of Nations Is Part Of

The Federal C o m m o n La w ................................................................................ 35

B. Plaintiffs Have Alleged Sufficient Facts To Establish A Violation

Of Customary International Law ................................................................. 40

C. Evolving Notions Of Customary International Law Support The

Right To Vote For Felons................................................................................. 42

VII. Defendants’ Practice Of Disfranchising Persons W ithout Notice Or Hearing,

Violates The Due Process Clause Of The Fourteenth Am endm ent.................... 45

CONCLUSION.......................................................................................................................................51

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases Page

Abebe-Jiri v. Negewo, 72 F.3d 844 (11th Cir. 1996)...............................................................................38

Abebe-Jiri v. Negewo,

No. 90-2010, 1993 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 21158 (N.D. Ga. Aug. 20, 1993)

affd other grounds, 72 F.3d 844 (11th Cir. 1996)................................................................... 37

Ad-Hoc Comm. O f Baruch Black & Hispanic Alumni Ass'n v. Bernard M. Baruch Coll.,

835 F.2d 980 (2d Cir. 1987)..........................................................................................................3

Alexander v. Sandoval, 532 U.S. 275 (1976)........................................................................................... 29

Allen v. Board o f Elections, 393 U.S. 544 (1969)................................................................................... 30

Armstrong v. Manzo, 380 U.S. 545 (1965).........................................................................................••••• 45

Atkins v. Virginia, 536 U.S. 304 (2002).................................................................................... 35, 39 n.25

August and Another v. Electoral Commission and Others, 1999 (4) BCLR 363 (CC)....................... 42

Baker v. Pataki, 85 F.3d 919 (2d Cir. 1996)............................................................................................. 1

Ball v. Brown, 450 F. Supp. 4 (N.D. Ohio. 1977)...................................................................... 31, 32-33

Barnes v. Merritt, 376 F.2d 8 (5th Cir. 1967)........................................................................................... 4

Benjamin v. Jacobson, 124 F.2d 162 (2d Cir. 1997)....................................................................... 21, 24

Blessing v. Freestone, 520 U.S. 329 (1997)........................................................................................... 32

Branum v. Clark, 927 F.2d 698 (2d Cir. 1991).......................................................................................... 4

Brier v. huger, 351 F. Supp. 313 (M.D. Pa. 1972)............................ 31

Brooks v. Nacrelli, 331 F. Supp. 1350 (E.D. Pa. 1971).............. 31

Buckley v. American Constitutional Law Foundation, Inc., 525 U.S. 182 (1999)............................. 27

Buell v. Mitchell, 274 F.3d 337 (6th Cir. 2001)...................... ........................................................ 40, 42

Burdick v. Takushi, 504 U.S. 428 (1992).................................................................................... 21,22, 27

Chapman v. Houston Welfare Rts. Org., 441 U.S. 600 (1979)............................................................. 32

City o f Cleburne v. Cleburne Living Ctr., Inc., 473 U.S. 432 (1985)....................................... 21, 22-23

Cleveland Bd. O f Ed. v. LaFleur, 414 U.S. 632 (1974).......................................................................... 49

Cort v. Ash, 422 U.S. 66 (1975).................................................................................................... 29-30, 31

Doe v. Rowe, 156 F. Supp.2d 35 (D. Me.. 2001)........................................................................46, 48, 49

Dunn v. Blumsiein, 405 U.S. 330 (1972).............................................................................. 21, 22, 23, 24

Dwyer v. Regan, 111 F.2d 825 (2d Cir. 1985)...................................................................... 4

Escalera v. New York City Hous. Auth., 425 F.2d 853 (2d Cir. 1970)......................................................4

Filartiga v. Pena-lrala, 630 F.2d 876 (2d Cir. 1980).................................................................... passim

Forti v. Suarez-Mason, 672 F. Supp. 1531 (N.D. Cal. 1987)......................................................... 37-38

General Electric Capital Corp. v. Domino's Pizza, Inc.,

No. 93 Civ. 5070, 1994 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 7277 (S.D.N.Y. June 2, 1994)....................... 3 n.2

Gieslerv. Petrocelli, 616 F.2d 636 (2d Cir. 1980)......................................... ..........................................4

Gonzaga University v. Doe, 536 U.S. 273 (1978)................................................................................. 32

Green v. Board o f Elections, 259 F. Supp. 290 (S.D.N.Y. 1966)............. 27

Green v. Board o f Elections, 380 F.2d 445 (2d Cir. 1967)..................................................................... 27

Grutter v. Bollinger, 123 S. Ct. 2325 (2003)................................................................................. 39 n.25

Heller v. Doe, 509 U.S. 312 (1993)................................................................................................. . 24, 25

Holmes v. New York City Housing Authority, 398 F.2d 262 (2d Cir. 1968)..........................................4

Hunter v. Underwood, 471 U.S. 222 (1985).................................................................................. passim

Illinois v. City o f Milwaukee, 406 U.S. 91 (1972)................................................................................. 34

Irish Lesbian and Gay Org. v. Giuliani, 3 43 F.3d 638 (2d Cir. 1998)............................................... 3, 4

Kadic v. Karadzic, 70 F.3d 232 (2d Cir. 1995).................................................................................36, 37

Lawrence v. Texas, 123 S. Ct. 2472 (2003)............................................................................. 35, 39 n.25

Cases (cont'd) Page

Cases (eont'd) Page

Little v. Streater, 452 U.S. 1 (1981)..........................................................................................................46

Maher v. Runyan, No. 94 Civ. 5052, 1996 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 642 (S.D.N.Y. Jan. 24, 1996)........ 3 n.2

Maine v. Thiboutot, 448 U.S. 1 (1980)..................................................................................................... 32

Maria v. McElroy, 68 F. Supp.2d 206 (E.D.N.Y. 1999).................................................... 38 n.24, 40, 41

Martinez-Baca v. Suarez-Mason,

No. 87-2057, 1988 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 19470 (N.D. Cal. Apr. 22, 1988).................... .......... 37

Matthews v. Eldridge, 424 U.S. 319 (1976)............................................................................................ 45

Monell v. Dep't o f Social Servs., 436 U.S. 658 (1978)........................................................................... 32

Morse v. Republican Party o f Virginia, 517 U.S. 186 (1996)............................................................... 30

Mt. Healthy City Board o f Education v. Doyle, 429 U.S. 274 (1977)....................................................8

Mullane v. Central Hanover Bank & Trust, 339 U.S. 306 (1950)........................................................ 45

Norman v. Reed, 502 U.S. 279 (1992).............................................................................................. 21, 27

Patel v. Contemporary Classics o f Beverly Hills, 259 F.3d 123 (2d Cir. 2001)......................... passim

Pellv. Procunier, 417 U.S. 817 (1974).................................................................................................. 26

Procunier v. Martinez, 416 U.S. 396 (1974).......................................................................................... 26

Raetzel v. Parks/Bellemont Absentee Election Bd., 762 F. Supp. 1354 (D. Anz. 1990).................... 46

Republic o f Philippines v. Marcos, 818 F.2d, 1473 (9th Cir. 1987).............................................. 37-38

Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U.S. 533 (1964)................................................................................................... 21

Richardson v. Ramirez, 418 U.S. 24 (1974).................................................................................. passim

Scheuer v. Rhodes, 416 U.S. 232 (1974)..................................................................................................4

Schwierv. Cox, No. 02-13214,2003 U.S. App. LEXIS 16410 (11th Cir. Aug. 11, 2003)........ passim

Sequihua v. Texaco, 847 F. Supp. 61 (S.D. Tex. 1994)........................................................................ 38

Shecter v. Comptroller o f the City o f New York, 79 F.3d 265 (2d Cir. 1996)....................................... 4

Cases (cont’d) Page

Sheppard v. Beerman, 18 F.3d 147 (2d Cir. 1994)........................................................................

Shivelhood v. Davis, 336 F. Supp. 1111 (D. Vt. 1971)........................................................................... 30

Smith v. Allwright, 321 U.S. 649 (1944).................................................. ................................................30

Stephens v. Yeomans, 327 F. Supp. 1182 (D.N.J. 1970)......................................................................... 25

Stevens v. Goord, No. 99 Civ 11669, 2003 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 10118 (S.D.N.Y. June 16, 2003)..........3

Suave v. Canada, 2002 SCC 68 (2002)..............................................................................................43

Tel-Oren v. Libyan Arab Republic, 726 F.2d 774 (D.C. Cir. 1984)................................ ......................37

Textile Workers Union v. Lincoln Mills o f Alabama, 353 U.S. 448 (1957).............................. 34-35

The Nereide, 13 U.S. (9 Cranch) 388 (1815).......................................................................................... 35

77ie Paquete Habana, 175 U.S. 677 (1900)............................................................................................ 35

Underwood v. Hunter, 730 F.2d 614 (11th Cir. 1984)........................................................................... ^

United States v. Mississippi, 380 U.S. 128 (1965)......................................................................... passim

United States v. Texas, 252 F. Supp. 234 (W.D. Tex. 1966)

affd mem. per curiam, 384 U.S. 155 (1966).......................................................................... 46

United States v. West Productions, Ltd.,

95 Civ. 1424, 1997 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 313 (S.D.N.Y. Jan. 17, 1997)......................................4

United States v. Yousef, 327 F. 3d 56 (2d Cir. 2003)............................................................................ 40

Village o f Arlington Heights v. Metro. Hous. Dev. Corp., 429 U.S. ~52 (1977)................ 8, 9, 16 n.l 1

Washington v. Davis, 426 U.S. 229 (1976)...............................................................................................8

IVhite v. Paulsen, 997 F. Supp. 1380 (E.D. Wa. 1998)...............................................................................

Williams v. Taylor, 677 F.2d 510 (5th Cir. 1982)..................................................................................... 2

Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U.S. 356 (1886)............................. ................................................................21

York v. Story, 324 F.2d 450 (9th Cir. 1963)..............................................................................................4

US Constitution Amendment XIV................................................................................................................5

US Constitution Amendment X V ............................................................................................................... 15

Civil Rights Acts of 1957 and 1960, 42 U.S.C. § 1971.................................................................. passim

Section 2 of Voting Rights Act of 1965, 42 U.S.C. § 1973 and 42 U.S.C. § 1983 ..................... passim

Federal Rules of Civil Procedure Rule 12(c)................................................................................... passim

Cong. Globe, 41st Cong., 2d Sess..................................................................................................... 15 n.10

H.R. Rep. No. 85-291 (1957), reprinted in, 1957 U.S.C.C.A.N. 1966.................. ................................30

28 U.S.C. § 1331.... ................................................................................. .......................................... passim

Alien Tort Statute, 28 U.S.C. § 1350..... ................................................................. ........... .............. 36, 37

International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, Article 2 5 ,1CCPR, 1966 U.S.T. LEXIS 521 ..40

Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination, Article 5, Section (c),

CERD, 1966 U.S.T. LEXIS 521......................................................................................................... 40

138 Cong. Rec. S4781-01 (daily ed. Apr. 2, 1992) ..................... ......................................................41

140 Cong. Rec. S7634-02 (daily ed. June 24, 1992)......................................... .............................. ......41

State Statutes and Legislative History

NY Constitution (1821) Article II § 1 (repealed 1870)............................................................ 11 n.4, 12

NY Constitution (1821) Article II § 2 (amended 1894) became Article II § 3 (1938)............... passim

NY Constitution Article V II......................................................................................... ...........................10

New York Election Law § 5-106(2)............................................................................................... passim

New York Laws of 1822, c. CCL, § XXV.............................................................................................. 16

New York Laws of 1896, c. 909, § 34(2)..................................................................................... 17 n. 13

New York Laws of 1901, c. 654, § 2 ...................................................................................................... 17

Federal Statutes and Legislative History'

NY C riminal Procedure § 220.50......................................................................................................... 47

NY Pena] Law § 65 (2003)........................................................................................................................ 47

Maine Revised Statute Annotated title 21, § 111 (2003)................................................................42 n.27

Vermont Statutes Annotated title 17 §, 2121 (2003).......................................................................42 n.27

Laws of Puerto Rico Annotated 16 § 3001, et seq. (2003).............................................................42 n.27

Miscellaneous

2A Moore, Federal Practice (2d ed. 1968)............................... ............... ..................................................4

Nathanial Carter, William Stone, and Marcus Gould, Reports of the Proceedings and Debates of

the Convention of 1821 (Albany: E & E Hosford, 1821)).................................................. 11, 13, 14

New York State Constitutional Convention Committee, Problems Relating to Home Rule and

Local Government (Albany, NY: J.B. Lyon Company, 1938)................................................. 12, 14

The Committee on State Legislation of ABCNY, 1935 Bulletin, No. 231 ................................... 12 n.5

Reports of the Proceedings and Debates of the Convention of 1846 (Albany: E & E Hosford,)...... 14

Documents of the Convention of the State of New York, 1867-1868 No. 16, 3, Volume One

(Albany: Weed, Parsons and Company, 1868)................................................................................ 15

ABA Standards for Criminal Justice (Third Edition), Collateral Sanctions and Discretionary

Disqualification of Convicted Persons (August 2003) at

http://www.abanet.Org/leadership/2003/summary/l 01 a.pdf..................................................... 46-47

US Census 2000 at http://www.factfinder.census.gov...................................................................26 n.16

U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics, "Probation and Parole in the United States

2002," August 2003, NCJ 201135 at http://www.ojp.usdoj.gov/bjs.......................................26 n.17

U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics, "Prison and Jail Inmates at Midyear

2002," April 2003, NCJ 198877 at http://www.ojp.usdoj.gov/bjs.......................... ............... 28 n.18

Restatement (Third) of Foreign Relations Law § 102(2)...................................................................... 40

Restatement (Third) of Foreign Relations Law § 702(f)..................................................................... 44

State Statutes and Legislative History' (cont’d)

http://www.factfinder.census.gov

http://www.ojp.usdoj.gov/bjs

http://www.ojp.usdoj.gov/bjs

PLAINTIFFS’ M EM ORANDUM OF LAW IN OPPOSITION TO

DEFENDANTS’ M OTION FOR JUDGM ENT ON THE PLEADINGS

Plaintiffs respectfully submit this memorandum of law in opposition to Defendants' Motion For

Judgment On The Pleadings pursuant to Rule 12(c) of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, in which

defendants ask this Court to dismiss plaintiffs’ claims that Article II, § 3 of the New York State

Constitution and § 5-106(2) of New York's Election Law violate the First, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth

Amendments of the United States Constitution: the Civil Rights Acts of 1957 and 1960; and customary

international law.

PRELIMINARY STATEMENT

This case raises fundamental legal questions about the integrity of New York’s democratic

processes generally, and their impact on its Black and Latino citizens in particular. Plaintiffs challenge

New York’s unconstitutional and discriminatory practice of denying suffrage to persons who are

sentenced to incarceration or subject to parole as a result of a felony conviction. The essence of

plaintiffs’ Amended Complaint is that New York’s felon disfranchisement regime has discernible

discriminatory origins and. not surprisingly, continuing corrosive and discriminatory effects.

This action seeks invalidation of a legal regime that has been the subject of focused analysis by

the Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit. Nevertheless, the legal issues raised by New York’s felon

disfranchisement law-s have defied easy resolution.1 Ignoring this reality, defendants seek to dismiss

cognizable claims even before plaintiffs have had the opportunity to develop a record to place the full

scope of the legal and factual issues squarely before this Court. A premature dismissal would be

inconsistent with the liberal standard of Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 12(c), the applicable

precedents, and the legal complexities that New York’s disfranchisement regime implicates.

See Baker v. Pataki. 85 F.3d 919 (2d Cir. 1996).

As plaintiffs make plain below, defendants attempt to achieve a favorable, threshold disposition

by framing far less than half of the story. Of equal importance, defendants urge dismissal based upon

their invitation to this Court to heighten the showing required of plaintiffs under Rule 12(c).

Consistent with plaintiffs’ burden at this stage of the litigation, the Amended Complaint provides

sufficient specificity on each claim, satisfies the pleading requirements of those claims, and provides

adequate background to substantiate the factual allegations that form the basis of each claim. For these

reasons, and those set forth in detail below, Defendants’ Motion For Judgment On The Pleadings

should be denied.

BACKGROUND FACTS

Plaintiffs seek to invalidate N.Y. Const, art. II, § 3 and New York Election Law § 5-106(2),

which unlawfully deny suffrage to incarcerated and paroled felons on account of their race.

N.Y. Const, art. II, § 3 provides:

The Legislature shall enact law-s excluding from the right of suffrage all persons convicted of

bribery or any infamous crime.

New York Election Law § 5-106(2) provides:

No person who has been convicted of a felony pursuant to the laws of the state, shall have the

right to register for or vote at any election unless he shall have been pardoned or restored to the

rights of citizenship by the governor, or his maximum sentence of imprisonment has expired, or

he has been discharged from parole. The governor, however, may attach as a condition to any

such pardon a provision that any such person shall not have the right of suffrage until it shall

have been separately restored to him.

The Amended Complaint, dated January 15, 2003, alleges that N.Y. Const, art. II, § 3 and New

York Election Law § 5-106(2) violate the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment,

based on an unlawful statutory classification (first claim); the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment (second claim); the Equal Protection Clause, based on intentional race discrimination

(third claim): the Fifteenth Amendment (third claim); the Civil Rights Acts of 1957 and 1960, codified

_ 2 -

at 42 U.S.C. § 1971 (third claim): Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965. based on § 5-106(2)’s

disproportionate impact on incarcerated and paroled Blacks and Latinos (fourth claim); Section 2 of

the Voting Rights Act of 1965. based on § 5-106(2)’s dilution of the voting strength of Blacks and

Latinos and certain minority communities in New York State (fifth claim); the First Amendment (sixth

claim); and Customary International Law (seventh claim).

STANDARD OF REVIEW

To prevail on their Motion For Judgment On The Pleadings dismissing plaintiffs’ claims

asserting civil rights violations, defendants must show this Court that there is simply no set of facts that

could support those claims.

The standard for evaluating defendants’ Rule 12(c) motion is identical to that of a 12(b)(6)

Motion for Failure to State a Claim. See Patel v. Contemporary Classics of Beverly Hills. 259 F,3d

123, 126 (2d Cir. 2001) (citing Insh Lesbian and Gav Org. v. Giuliani. 143 F.3d 638, 644 (2d Cir.

1998); see also Sheppard v. Beerman, 18 F.3d 147, 150 (2d Cir. 1994); Ad-Hoc Comm, of Baruch

Black & Hispanic Alumni Ass'n v. Bernard M. Baruch Coll.. 835 F.2d 980, 982 (2d Cir. 1987)). As

with a 12(b)(6) motion, a court evaluating a Rule 12(c) motion must read a plaintiff’s complaint

generously, accepting as true all of the allegations in the complaint, and drawing all reasonable

inferences in the non-moving party’s favor. See Patel, 259 F.3d at 126; Irish Lesbian and Gay Org.

143 F.3d at 644. A court will not dismiss a case on a Rule 12(c) motion unless “it appears beyond a

reasonable doubt that the plaintiff can prove no set of facts in support of [his] claim which would

entitle him to relief.” Irish Lesbian and Gav Org., 143 F.3d at 644 (quoting Sheppard. 18 F.3d at 150);

- 3 -

See also Stevens v. Goord. No. 99 Civ. 11669, 2003 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 10118. at *9 n.6 (S.D.N.Y. June

16, 2003).2

Thus, in considering a Rule 12(c) motion, the trial court “is merely to assess the legal feasibility

of the complaint, not to assay the weight of the evidence which might be offered in support thereof.”

United States v. West Productions. Ltd.. No. 95 Civ. 1424, 1997 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 313, *3 (S.D.N.Y.

Jan. 17, 1997) (quoting Giesler v, Petrocelli. 616 F.2d 636, 639 (2d Cir. 1980)). Indeed. “[t]he issue is

not whether a plaintiff will ultimately prevail but whether the claimant is entitled to offer the evidence

to support the claims.” Id. (quoting Scheuer v. Rhodes, 416 U.S. 232, 236 (1974)).

The Second Circuit requires that courts apply this already demanding standard for prevailing on

a Rule 12(c) motion with “particular strictness when the plaintiff complains of a civil rights violation.”

Irish Lesbian and Gav Ore., 143 F.3d at 644 (quoting Branum v. Clark, 927 F.2d 698, 705 (2d Cir.

1991)). As the Second Circuit long-ago noted in Escalera v. New York City Hous. Auth., 425 F.2d

853 (2d Cir. 1970), “[a]n action, especially under the Civil Rights Act, should not be dismissed at the

pleadings stage unless it appears to a certainty that plaintiffs are entitled to no relief under any state of

the facts, which could be proved in support of their claims.” 425 F.2d at 857 (emphasis added) (citing

Holmes v. New York City Housing Authority, 398 F.2d 262, 265 (2d Cir. 1968); Bames v. Memtt,

376 F.2d 8 (5th Cir. 1967); York v. Story,' 324 F.2d 450, 453 (9th Cir. 1963), 2A Moore, Federal

Practice para. 12.08, at 2271-74 (2d ed. 1968)); see also Shechter v. Comptroller of the City of New

York. 79 F.3d 265, 270 (2d Cir. 1996) (noting that courts must draw all reasonable inferences in favor

of the non-moving party on a Rule 12(c) motion, and this standard is applied with “particular strictness

See also Maher v. Runvon. No. 94 Civ. 5052, 1996 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 642, at *8 (S.D.N.Y. Jan. 24. 1996) (citing

General Electric Capital Corp. v. Domino's Pizza. Inc.. No. 93 Civ. 5070, 1994 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 7277, at *3

(S.D.N.Y. June 2. 1994) (“When entertaining a Rule 12(c) motion, a court may consider only the factual

allegations of the complaint, which are taken as true; any documents attached to the complaint as exhibits or

incorporated by reference, and any matters of which judicial notice may be taken.”).

- 4 -

when the plaintiff complains of a civil rights violation”)(mtemal citations and quotations omitted):

Dwver v. Regan, 777 F.2d 825, 829 (2d Cir. 1985) (same).

Thus, in order to prevail on their Motion For Judgment On The Pleadings, defendants must

satisfy a rigorous and exacting standard.

ARGUMENT

I.

RICHARDSON V. RAMIREZ DOES NOT

DISPOSE OF PLAINTIFF'S CONSTITUTIONAL CLAIMS

Defendants argue that the Supreme Court’s decision in Richardson v. Ramirez, 418 U.S. 24

(1974), “disposes all of the constitutional claims in this action.” Defs.’ Mot. at 8. Defendants

characterization of Richardson’s holding, however, is grossly overstated. Indeed, the Court's decision

in Richardson left open the issues raised here by plaintiffs’ Equal Protection, Due Process and other

Constitutional claims.

In Richardson, the Supreme Court examined the particular question of whether the Equal

Protection Clause, § 1 of the Fourteenth Amendment, prohibited California’s felon disfranchisement

scheme in light of § 2 of the same Amendment, which appeared to sanction such laws. Richardson,

418 U.S. at 27. The Court held that § 2 of the Fourteenth Amendment allows states to exclude from

the franchise convicted felons, notwithstanding § l ’s requirement that “no state shall . . . deny to any

person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the law's.” U.S. Const. Amend. XIV, § 1. The

Court looked at the Fourteenth Amendment as a whole, stating that Ҥ 1, in dealing with voting rights

as it does, could not have been meant to bar outright a form of disenfranchisement which was

expressly exempted from the less drastic sanction of reduced representation which § 2 imposed for

other forms of disenfranchisement.” Richardson, 418 U.S. at 55. The Court concluded that § 2 is “as

much a part of the Amendment as any of the other sections.” Id.

- 5 -

Richardson did not. however, close the door on all Constitutional challenges to felon

disfranchisement provisions: indeed it did not even close the door on Equal Protection challenges. The

Supreme Court's own decision make this plain. Nearly a decade after deciding Richardson, the Court

in Hunter v. Underwood, 471 U.S. 222 (1985), found that Alabama had enacted its felon

disfranchisement provision with discriminatory intent, and therefore in violation of the Equal

Protection Clause, on grounds that § 2’s authorization of state disfranchisement laws did not permit

purposeful discrimination. Hunter, 471 U.S. at 233. Thus, Richardson clearly was not the last word on

Constitutional challenges to felon disfranchisement provisions.

Recognizing Hunter, defendants attempt to shoehorn all of plaintiffs’ non-intentional

discrimination claims into Richardson's narrow holding, expanding Richardson to stand for the

proposition that felon disfranchisement restrictions are never subject to a heightened level of scrutiny,

unless the felon disfranchisement provision involves a suspect class. Defs.’ Mot. at 45. Yet. the Court

in Richardson did not address the issues raised by plaintiffs in this case. Specifically, the Court did not

address whether states and election officials, when enacting and implementing felon disfranchisement

provisions, may chose among disqualifying crimes and individuals in a way that violates the

Constitution. Indeed, Hunter struck down race-based classifications. Hunter. 471 U.S. at 232-33.

Moreover, the Richardson Court noted that it was leaving open the “alternative contention that there

was such a total lack of uniformity in county election officials' enforcement of the challenged state

laws as to work a separate denial of equal protection.” Richardson, 418 U.S. at 56. Thus, plaintiffs

may challenge a state’s scheme for choosing which convicted felons to disfranchise. That is precisely

what plaintiffs here seek to do; plaintiffs’ First and Second claims for relief allege that defendants have

maintained and administered a non-uniform practice of disfranchising persons convicted of a felony

under the laws of New York, whereby persons convicted of a felony who receive a suspended or

- 6 -

commuted sentence or are sentenced to probation or conditional or unconditional discharge are

permitted to vote while persons convicted of a felony who are sentenced to incarceration are not.

Amended Complaint fj[ 79, 82. Richardson simply does not dispose of these claims.

Likewise, though defendants acknowledge that “the Richardson Court did not address . . .

directly” a Fifteenth Amendment claim, they nevertheless attempt to dismiss plaintiffs’ Fifteenth

Amendment claim on the basis that the Fourteenth Amendment's limited sanction of felon

disfranchisement provisions bars any claim under that amendment as well. Defs.’ Mot. at 18. Again,

Richardson cannot be read so broadly, and plaintiffs’ Fifteenth Amendment claim must be dealt with

on its merits, as plaintiffs do herein.

II.

PLAINTIFFS’ AMENDED COMPLAINT SUFFICIENTLY ALLEGES A CLAIM FOR

INTENTIONAL DISCRIMINATION UNDER THE EQUAL PROTECTION CLAUSE

OF THE FOURTEENTH AMENDMENT AND UNDER THE FIFTEENTH AMENDMENT

Defendants contend that because New York’s facially neutral felon disfranchisement provision

is not motivated by a discriminatory purpose, plaintiffs fail to state a claim for violation of the Equal

Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment and the Fifteenth Amendment. Defs.’ Mot. at 10-11.

Defendants’ argument is not only factually erroneous, as it simply fails to address the reality of New

York's long history of intentional discrimination against Blacks in voting, but it also relies on a

misstatement of established legal principle. To survive a Rule 12(c) motion plaintiffs need only state

facts, which taken as true, would entitle them to relief under a particular claim. See Patel, 259 F.3d at

126. In this case, plaintiffs assert that New York’s extensive history of intentional racial

discrimination in voting dates back to its Constitution in 1777 and spans more than a century. During

this time, delegates to Constitutional Conventions and legislators purposefully erected barriers,

including the enactment of a felon disqualification statute, that were intended to, and have had the

- 7 -

effect of, disfranchising Blacks and other racial minorities. These allegations, taken as true,

sufficiently state the basis for this Court to find a violation of the Equal Protection Clause ot the

Fourteenth Amendment and the Fifteenth Amendment.

A. The Amended Complaint Contains Facts Sufficient To Satisfy The

Standard for Alleging Discriminatory Intent Under the Equal Protection

Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment as Articulated bv the Supreme Court.

Defendants seek to heighten the standard for alleging intentional discrimination under the

Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. When presented with a facially neutral state

law that produces disproportionate effects along racial lines, the Supreme Court requires courts to

apply the test outlined in Village of Arlington Heights v. Metro. Hous. Dev. Corp.. 429 U.S. 252

(1977), to determine whether the law violates the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment. See Hunter, 471 U.S. at 228. In Arlington Heights, the Supreme Court held that

although “[disproportionate impact is not irrelevant,” proof of “racially discriminatory intent or

purpose is required to show a violation of the Equal Protection Clause.” 429 U.S. at 264-265 (quoting

Washington v. Davis, 426 U.S. 229, 242 (1976)). However, “once racial discrimination is shown to

have been a ‘substantial' or ‘motivating’ factor behind enactment of the law, the burden shifts to the

law’s defenders to demonstrate that the law would have been enacted without this factor.” Hunter, 471

U.S. 227 (citing Mt. Healthy Citv Board of Education v. Dovle. 429 U.S. 274. 287 (1977)).

Determining whether invidious discriminatory purpose was a motivating factor behind an

official action “demands a sensitive inquiry into such circumstantial and direct evidence of intent as

may be available.” Arlington Heights, 429 U.S. at 266. Accordingly, as evidence of intent courts may

consider, among other things, whether the impact of an action bears more heavily on one race than

another, the historical background of an official decision, and the legislative or administrative history

of an official action, particularly where there are statements by members of the decision-making body.

See Id. at 266-67 (quoting Washington. 426 U.S. at 242). ,

In this case, the Amended Complaint sufficiently alleges that New York's restrictions on felon

voting were enacted with the intent to discriminate against “persons incarcerated and on parole for a

felony conviction ... on account of their race” in violation of the Equal Protection Clause of the

Fourteenth and the Fifteenth Amendment. See Amended Complaint, ffl 85-86. To substantiate the

allegations in the Amended Complaint that an invidious purpose was a motivating factor in the

enactment of New York’s felon voting restrictions, plaintiffs utilize the available historical background

and legislative history of the restrictions. Additionally, plaintiffs point to the fact that the impact of the

action bears more heavily on Blacks and Latinos than on whites. See Arlington Heights, 429 U.S. at

266-268.

In a further attempt to raise the Rule 12(c) standard, defendants compare the claims made by

plaintiffs in the Amended Complaint with the “convincing direct evidence" available to plaintiffs in

Hunter. Defs.’ Mot. at 10; see Hunter. 471 U.S. at 229-231. In that case, the Supreme Court

invalidated a 1901 provision of the Alabama Constitution that disfranchised persons based on

convincing direct evidence that the State had enacted the provision for the purpose of disfranchising

Blacks. Id. Defendants’ comparison, however, is improper.

The issue is not whether plaintiffs will ultimately prevail, but whether plaintiffs are “entitled to

offer' evidence to support the claims in the Amended Complaint. Id. (emphasis added). Thus,

plaintiffs are not required to produce evidence, direct or otherwise, as defendants suggest here. Rather,

plaintiffs are required to, and indeed do, sufficiently allege that New York practiced unlawful

- 9 -

discrimination in violation of the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments and the Supreme Court's

rulings in Arlington Heights and Hunter.J

1. New York's extensive history of intentional racial

discrimination in voting dates as far back as the

State's provisional constitution regarding suffrage.

Defendants assert that plaintiffs “fail to state a claim upon which relief can be granted because

the Amended Complaint stops short of asserting that any New York constitution since 1777

intentionally discriminated against [Bjlacks convicted of crimes,” and that the Amended Complaint

only contains a single conclusion “that [a] State felon disqualification statute was enacted with an

intention to discriminate against [Bjlacks.” Defs.’ Mot. at 9-10. On the contrary, plaintiffs’ Amended

Complaint asserts throughout that New York’s extensive history of intentional racial discrimination in

voting dates as far back as New York’s Constitution in 1777 and spans more than 100 years, during

which time delegates to Constitutional Conventions and legislators purposefully erected barriers

intended to prevent Blacks from voting, culminating in the development and enactment of a felon

disqualification statute, that were intended to, and have had the effect of, disproportionately

disfranchising Blacks and other racial minorities. Amended Complaint, 41-42, 43-46, 51-52, 57.

(a) New York State Constitution. 1777

The Amended Complaint asserts that the framers of the New York State Constitution in 1777

intentionally excluded minorities from the polls by limiting suffrage to property holders and free men.

Amended Complaint, % 43 (citing N.Y. Const, art. VII) (repealed 1826)). Not surprisingly, these

Although Rule 12(c) does not require plaintiffs at this stage of the litigation to provide an exhaustive history of

New York's intentional discrimination against Blacks, and the allegations contained in the Amended Complaint

sufficiently state the basis for this Court to find a violation of the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment and the Fifteenth Amendment, plaintiffs here provide additional historical information to highlight the

context in which New York's felon disfranchisement laws were enacted.

- 10 -

voting requirements disproportionate]}' disfranchised Blacks, most of w hom were neither property

holders nor free men.

Defendants respond by stating that “the Amended Complaint recognizes that the constitution of

1777 did not restrict voting on the part of criminals.” Defs.’ Mot. at 11. Defendants fail to recognize,

however, that a restriction specifically disqualifying criminals from voting would have been

unnecessary, and indeed redundant, as the goal of disfranchising Black voters was adequately

accomplished by the limitations contained in the 1777 New York State Constitution. Moreover,

defendants’ focus on the absence of specific language excluding criminals from voting is a distraction

from the real issue: that the framers of New Y'ork’s Constitution crafted a document that intentionally

excluded Blacks and other racial minorities from democratic participation in general, and suffrage in

particular, solely on the basis of their color. Amended Complaint, f f 42-43.

In 1801 the legislature removed all property restrictions from the suffrage requirements for the

election of delegates to New York’s first Constitutional Convention. Id. at f 45. However, to ensure

that this act would not extend the vote to Blacks, the legislature expressly excluded Blacks from

participating in this election. Id.

(b) New York Constitutional Convention of 1821

The historical origin of the felon disfranchisement provisions at issue here trace their roots to

the Constitutional Convention of 1821 — a convention dominated by racist invective.

At the New York Constitutional Convention of 1821, the question of Black suffrage sparked

heated discussions, during which delegates expressed their views that Blacks, as a “degraded” people,

and by virtue of their natural inferiority, were unfit to participate in civil society. Nathanial Carter,

William Stone, and Marcus Gould. Reports of the Proceedings and Debates of the Convention of 1821,

198 (Albany: E. & E. Hosford. 1821) (hereafter “Debates of 1821”). Based on their belief in Blacks’

- 11 -

unfitness for democratic participation, the delegates crafted new voting requirements that were aimed

at stripping Black citizens of their previously held, although severely restricted, right to vote.

Amended Complaint, ‘jj 47.

The delegates’ efforts to disfranchise Black voters were successful, as only 298 of

approximately 29,701, or 1% of the Black population, met these new requirements. As an additional

barrier to voting, Blacks were required to possess a freehold estate worth $250 for the year preceding

any election. Id. N.Y. Const. (1821), art. II, § 1 (repealed in 1870). The delegates' expressed

justification for the property requirement demonstrates that the voting condition was not designed to

limit the franchise to the propertied classes. Rather, as articulated by one delegate at the 1821

Constitutional Convention, the property qualification “was an attempt to do a thing indirectly which

we appeared either to be ashamed of doing, or for some reason chose not to do directly... This freehold

qualification is [for Blacks] a practical exclusion [from the franchise].” New York State Constitutional

Convention Committee, Problems Relating to Home Rule and Local Government, 143 n.13 (Albany,

NY: J.B. Lyon Company, 1938) (hereafter “Home Rule”).5 With respect to the property requirement

for Blacks, a subsequent constitutional convention committee noted that “[the property qualification]

was retained [for Blacks] ... not in the belief that ownership of property was a proper criterion of the

right to vote. That retention was merely a subterfuge for keeping suffrage from the Negro.” Home

Rule, 161.

Heightening the requirements for Black voters previously outlined in the New York State Constitution of 1777,

delegates to the New York Constitutional Convention of 1821 required that Black males be citizens of New York

for three years while whites were only required to be “inhabitants” for one year. N.Y. Const. (1821), art. II, § 1

(repealed in 1870). Moreover, as an additional barrier to voting. Blacks were required to possess a freehold estate

worth S250 for the year preceding any election. Id.

In fact, in an 1826 amendment to the Constitution. New York formally abolished all property requirements for

white male suffrage, "except to "persons of color.'” Home Rule. 160 (quoting The Committee on State Legislation

of AJBCNY, 1935 Bulletin, No. 231).

- 12 -

New York's intentional discrimination against Blacks culminated in art. II, § 2, a new provision

in the Constitution of 1821, which further restricted the suffrage of Blacks by permitting the state

legislature to disfranchise persons “who have been, or may be. convicted of infamous crimes."

Amended Complaint, <f 49; See N.Y. Const. (1821), art. II, § 2. The historical record suggests that art.

II. § 2 was adopted for an invidious purposes.6 The language of the delegates themselves makes clear

that N.Y. Const. (1821), art. II, § 2 was created to serve the same purposes as the heightened

citizenship and onerous property requirements placed on Blacks: it was enacted to disfranchise

Blacks. For instance, one delegate warned his colleagues to “[l]ook to your jails and penitentiaries.

By whom are they filled? By the very race, whom it is now' proposed to cloth wnth pow'er of deciding

upon your political rights.” Debates of 1821. 191. Another delegate urged the convention to “{sjurvey

your prisons — your alms houses — your bridewells and your penitenciaries and w'hat a darkening

host meets your eye! More than one-third of the convicts and felons which those walls enclose, are of

your sable population.” Id. at 199. As is made manifest by their own language, the delegates not only

understood that enacting art. II, § 2 would result in the disproportionate disfranchisement of the

“sable” or Black population, but actually intended to bring about that result to prevent Blacks from

affecting w'hites’ political power. One delegate expressed that it was necessary to exclude Blacks from

any “footing of equality in the right of voting,” and reasoned that “[Blacks] are a peculiar people,

incapable ... of exercising the privilege w'ith any sort of discretion, prudence, or independence. They

have no just concepts of civil liberty. They know not how' to appreciate it. and are consequently

indifferent to its preservation.” Id. at 180. Another delegate summed up the goals of the delegates to

Even a subsequent constitutional committee was unable to discern any reason for its insertion or locate evidence of

hearings, debates, or committee discussions on the new provision. Home Rule. 173. According to a report

published by the constitutional convention committee of 1938. the felon disfranchisement provision of 1821 was

adopted "apparently with a complete lack of preliminaries.” Id.

- 13 -

the 1821 Constitutional Convention by stating that “all w ho are not white ought to be excluded from

political rights.” Id. at 183.

Defendants’ claim that “[plaintiffs’ historical account ignores the fact that, at the same time,

the People of the State of New York, and their Legislature, were busy abolishing slavery," Defs.' Mot.

at 12 n.3, is not substantiated by New York’s social and political landscape at that time. The delegates

to the convention of 1821 saw no incongruity in abolishing slavery in New York while at the same

time barring Blacks from voting. In fact, in the debates over extending access to the franchise to

Blacks, one delegate commented that “this exclusion [from the ballot] invades no inherent rights, nor

has it any connection at all with the question of slavery.” Debates of 1821, 181.

(c) New York Constitutional Convention of 1846

The question of Black suffrage continued to spark heated debates at the New York

Constitutional Convention of 1846, where delegates accepted that “prejudice against the Negro” was

not only accepted, but was desirable. Home Rule. 144. Advocating for the denial of equal suffrage to

Blacks, delegates continued to make explicit statements regarding Blacks’ unfitness for suffrage,

including one delegate’s assertion that “[Blacks] were an inferior race to whites, and would always

remain so.” Constitutional Convention of 1846, Debates of 1846, 1033 (hereafter “Debates of 1846”).

Felon disfranchisement was further solidified at the Convention of 1846. Amended Complaint,

][ 52.' When re-enacting the felon disfranchisement provision while specifically including “any

infamous crime” in the category of convictions that would disqualify voters, the delegates were acutely

As amended, the relevant constitutional provision stated: “Laws may be passed excluding from the right of

suffrage all persons who have been or may be convicted of bribery, of larceny, or of any infamous crime; and for

depriving every person who shall make, or become directly or indirectly interested in any bet or wager depending

upon the result of any election, from the right to vote at such election.’' Amended Complaint. 1 52.; See N.Y.

Const, art. il, § 2 (amended 1984)(emphasis added).

- 14 -

aware that these restrictions would have a discriminatory impact on Blacks. Amended Complaint, at 'I

53.

In one portentous reflection on the inherent injustice to w hich this action is directed, during the

debates about whether to extend equal suffrage rights to Blacks at the 1846 Constitutional Convention,

one delegate declared that the proportion of “infamous crime" in the minority population was more

o

than thirteen times that in the white population. Debates of 1846. 1033.

(d) New York Constitutional Convention of 1866-67

At the New York Constitutional Convention of 1866-67, the delegates determined, after

engaging in heated debates regarding whether to eliminate the discriminatory property qualification for

Blacks, that if Blacks w-ere ever to be afforded equal voting rights, “it must be done by the direct and

explicit vote [via a referendum] of the electors. We are foreclosed from any other course by the

repeated action of the State.” Documents of the Convention of the State of New' York, 1867-1868,

No. 16, 3, Volume One. Albany: Weed, Pearsons and Company, 1868 (hereafter “Documents”).

That the electorate voted largely against this measure (to afford Blacks equal voting rights),

however, did not at all surprise the delegates, since the electorate had previously and consistently voted

against similar referendums regarding voting rights for Blacks.9 Indeed, as the delegates knew, asking

the electorate to determine w'hether Blacks should receive equal voting rights w'as the functional

equivalent of the delegates and Legislature answering that question negatively themselves. In

elevating the “popular will” above the voting rights of Blacks, the delegates of New York’s

Moreover, the delegates to the convention were well aware of. and even admired, the success of other slaveholding

state legislatures in excluding Blacks from the ballot. As one delegate suggested to the convention, “in nearly all

the western and southern states ... the [BJlacks are excluded . ..would it not be well to listen to the decisive weight

of precedents furnished in this case also?’’ Debates of 1846. 181.

For instance, an 1846 referendum to extend the universal franchise to Blacks failed by a vote of 85.306 to 223,884.

In 1850, the reintroduced referendum failed by a vote of 197.503 to 337,984. Documents, No. 16, 3, Volume One.

- 15 -

Constitutional Convention o f 1866-67 made it c lear that an equal opportunity for Blacks to vote would

be unavailable because the “convictions of the m am body of the constituency"’ w ould not permit it.

New York’s explicitly race-discriminatory suffrage requirements were in place until voided tn

1870 by the adoption of the Fifteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution. Amended

Complaint, f 55; See U.S. Const, amend. XV. However, two years after the passage of the Fifteenth

Amendment,10 an unprecedented committee convened and amended the disfranchisement provision in

New York to require the state legislature, at its following session, to enact law's excluding persons

convicted of infamous crimes from the right to vote.11 Amended Complaint, f 56; See N.Y. Const, art.

II, § 2 (amended 1894). Until that point, the enactment of such laws had been permissive. Amended

Complaint, f 56.

Defendants’ claim that this amendment to the disfranchisement provision is “meaningless”

because “persons convicted of ‘infamous crimes’ had been disqualified from voting for fifty years”

pursuant to N.Y. Laws of 1822, c. CCL, § XXV, Defs.’ Mot. at 14. is unpersuasive. Prior to the

passage of the amendment to the disfranchisement provision, the Legislature was not required to enact

felon disqualification laws, and could in fact choose not to (if it were later determined, for example,

that such laws had been written into the state Constitution by delegates w'bo were — as here —

motivated by an unlawful discriminatory purpose). The committee’s removal of discretion from the

Legislature here is significant in light of the timing of the meeting (shortly after the passage of the

Fifteenth Amendment), the expressed intentions of many of the delegates at prior constitutional

New York initially ratified the Fifteenth Amendment but later withdrew its ratification. Cong. Globe, 41st Cong..

2d Sess. at 1447-81.

This is a significant factor under Arlington Heights, where the Supreme Court held that the historical background

of an official decision is evidence of intent that courts may consider when determining whether an invidious

discriminatory purpose was a motivating factor behind an official action. Arlington Heights. 429 U.S. at 266-67.

- 16 -

conventions to deprive Blacks o f the right to vote, and their clear intention for felon disqualification

provisions to accomplish that purpose.

(e) New York Constitutional Convention of 1894

In 1894, at the New York Constitutional Convention following this amendment, the delegates

permanently abandoned the permissive language and adopted a constitutional requirement that the

legislature enact disfranchisement law's. Amended Complaint, ‘f 57. As amended, the provision stated

that “[t]he legislature shall enact laws excluding from the right of suffrage all persons convicted of

bribery or of any infamous crime.” Id.; See N.Y. Const, art. II, § 2 (emphasis added).1" This is the

language of the Constitution (originally created in 1821) pursuant to which § 5-106(2) of the New

York State Election Law was enacted and under which persons incarcerated and on parole for felony

convictions are presently disfranchised in New York. Id.

Defendants claim that the Legislature did not in fact enact such laws and that the felon

disqualification lapsed in 1896. Defs.’ Mot. at 15. “If there w'as any discriminatory intent before

1896,” defendants allege, “that year’s lapse in felon voting disqualification broke the chain.” Id.

First, defendants’ suggestion that the felon disqualification lapse w'as an attempt by the Legislature to

cure any discriminatory intent before 1896 (which defendants disavow) would clearly be inconsistent

w'ith its past intentional and numerous attempts to exclude Blacks from voting.1'’ Rather, the felon

In New York's Constitutional Convention of 1938, Article II, § 2 of the New York Constitution of 1894 became

Article II, § 3. See N.Y. Const, art II. § 3.

ln addition to defendants’ claim that the Legislature failed to enforce voter disfranchisement laws at the close of

the nineteenth century, defendants also allege that § 34(2) of Chapter 909 “provided for registering to vote and

voting from State prison.” Defs.' Mot. at 15 (emphasis added). The relevant provision from chapter 909 of N.Y.

Laws of 1896 states:

For the purpose of registering and voting no person shall be deemed to have gained or lost a residence, by

reason of his presence of absence.. .while confined in any public prison.

N.Y. Laws of 1896. c. 909, § 34(2).

- 17 -

disqualification lapse in 1896 appears to be more a product of the Legislature's carelessness than its

desire to remedy the effects of past discrimination, as evidenced by the fact that the Legislature was

required to enact such laws and indeed five years later, through N.Y. Laws of 1901, c. 654, § 2, did

reinstate a felon voting disqualification. Defs.’ Mot. at 15; See N.Y. Laws of 1901. c. 654, § 2.

Moreover, defendants' notion that the mere passage of time cleanses legislation of the invidious

intent behind its original passage is equally unpersuasive, and, in fact, was rejected by the Supreme

Court in Hunter. Hunter, 471 U.S at 232-34. In that case, the Supreme Court found that “events

occurring m the succeeding 80 years’- since the law was adopted did not cure it of its original

discriminatory purpose, particularly because the law had an immediate disparate impact on Black

voters when it was enacted, which earned on into the present day. Id. at 232-33. In fact, the Supreme

Court upheld the 11th Circuit’s ruling that although the current administrators of the law acted in “good

faith” in administenng the statute without reference to race, “neither impartiality nor the passage of

time ... can render immune a purposefully discriminatory scheme whose invidious effects still

reverberate today.” Underwood v. Hunter. 730 F.2d 614, 621 (11th Cir. 1984)), aff’d. Hunter v.

Underwood. 471 U.S. 222 (1985).

2. The allegations contained in the Amended

Complaint are more detailed and specific than

the allegations in the complaint submitted in Hunter.

Defendants devote several paragraphs to their attempt to distinguish plaintiffs’ allegations from

those accepted by the Supreme Court in Hunter by distinguishing New York Constitutional

Significantly, the language of § 34(2) does not mandate or even permit felons to register to vote from prison or to

vote at all for that matter. It merely ensures that if incarcerated citizens were ever permitted to vote, they could not

cast ballots in the localities in which prisons were located. Moreover, defendants’ interpretation of § 34(2) in this

way directly contradicts the mandatory disqualification provision of the N.Y. Constitution in place at that time,

which required that “(t)he legislature shall enact laws excluding from the right of suffrage all persons convicted of

bribery or of any infamous crime.” N.Y. Const, of 1894. art. II § 2.

- 18 -

Conventions from the Alabama Constitutional Convention of 1901, where the President of the

Convention, in his opening address, stated his desire “[t]o establish white supremacy in this State,”

Defs.’ Mot. at 11 (quoting Hunter, 471 U.S. at 229). Defendants conclude by suggesting that unlike

the State of Alabama, New York has never enacted any provision for the purpose of disfranchising

Blacks. Id. at 10-11.

First, the allegations contained in the Amended Complaint are, in fact, more detailed and

specific than those contained in the Complaint in Hunter. In Hunter, the Supreme Court relied on a

number of historical factors presented to the District Court as evidence of a Alabama’s discriminatory

intent, including the racial composition of members of the convention that enacted the bill, comments

made by the President of the convention, historical studies noting that the Alabama convention was

part of a movement to disfranchise Blacks, evidence that the crimes selected for inclusion in the

provision were more commonly committed by Blacks, and witness testimony that the provision had an

immediate and predictable disparate impact on Black voters. Hunter, 471 U.S at 224-30. Although

these factors were enumerated as evidence of discriminatory intent by both the Supreme Court in

Hunter and the 11th Circuit, Underwood v. Hunter, 730 F.2d 614 (1 l !h Cir. 1984), none of these factors

were mentioned in the original Complaint filed by plaintiffs in the case. See Complaint, Underwood v.

Hunter, CA78 Mo704S (filed June 21, 1978)14 (annexed as Exhibit A to Haygood Affirmation,

September 9, 2003).

In contrast, the Amended Complaint in this case reveals a historical pattern of discrimination

by New York intended to disfranchise Black voters. See Amended Complaint. 'H 39-57. The historical

development of New York's felon disfranchisement laws in the Amended Compliant is not embodied

It is important to note here, however, that this is evidence that must be developed through discovery, including

expert testimony, and is not required to be proven or alleged in exhaustive detail by plaintiffs at this stage in the

litigation. Plaintiffs here should be afforded an opportunity to develop their case as plaintiffs were in Hunter.

in mereJy one comment made at one convention, but rather is a culmination of specific efforts aimed at

disfranchising Blacks that spanned the course of more than 100 years. Id. at f ! 43. 45-46. 51-52. 57.

As a result, plaintiffs’ Amended Complaint clearly alleges Equal Protection and Fifteenth Amendment

claims in a way that is consistent with the Supreme Court's holding in Hunter. Second, defendants'

assertion that unlike Alabama, New' York has never enacted any provision for the purpose of

disfranchising Blacks completely ignores New York’s history. See supra pp. 7-20.

Not surprisingly, New York's felon disqualification statutes, as intended, have had a

predictable and lasting impact on Blacks.15 Today, Blacks and Latinos are sentenced to incarceration

at substantially higher rates than whites, and whites are sentenced to probation at substantially higher

rates than Blacks and Latinos. Amended Complaint, f 66. Collectively Blacks and Latinos make up

86% of the total current prison population and 82% of the total current parolee population in New

York State, while they approximate only 31% of New York’s overall population. Id. at ^ 64.

As a result, nearly 52% of those currently denied the right to vote pursuant to New' York State

Election Law § 5-106(2) are Black and nearly 35% are Latino. Id. at f 68. Collectively, Blacks and

Latinos comprise nearly 87% of those currently dented the right to vote pursuant to New York State

Election Law § 5-106(2). Id.

In sum, the Amended Complaint sufficiently alleges a claim for intentional discrimination

under the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment and under the Fifteenth Amendment.

Plaintiffs' allegations regarding § 5-106(2)'s disparate impact on Blacks and Latinos are also outlined in the

Amended Complaint at 61-68.

- 20-

III.

THE AMENDED COMPLAINT SUFFICIENTLY STATES A CLAIM THAT

DEFENDANTS’ NON-UNIFORM PRACTICES DISFRANCHISING PERSONS

CONVICTED OF A FELONY VIOLATE THE EQUAL PROTECTION CLAUSE

In support of this claim, plaintiffs assert that New York’s non-uniform practices of

disfranchising only those felons sentenced to incarceration or serving parole are neither compelling nor

rational. These allegations, taken as true, sufficiently state the basis for a violation of the Equal

Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

A. The Application Of Strict Scrutiny Is Appropriate Here.

Defendants claim that the Supreme Court’s decision in Richardson “disposes all of the

constitutional claims in this action,” Defs.’ Mot. at 8, and attempt to expand Richardson’s narrow

holding to stand for the proposition that felon disfranchisement restrictions are never subject to

heightened scrutiny, unless the felon disfranchisement provision involves a suspect class. Id. at 45. In

reality, however, the Court in Richardson did not preclude the application of strict scrutiny to felon

disfranchisement cases. See Richardson. 418 U.S. at 56. Neither did the Court specifically address the

issues raised by plaintiffs in this case: whether states, when enacting and implementing felon

disfranchisement statutes, may choose to disqualify felons from voting in a manner that violates the

Constitution. Id.

Here. § 5-106(2)’s distinction among felons, that disqualifies from voting only those felons

sentenced to incarceration and serving parole, violates the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment, see Amended Complaint, f l 79-80. The Equal Protection Clause requires that all persons

who are similarly situated be treated alike. Citv of Clebume v. Clebume Living Ctr., Inc., 473 U.S.

432. 439 (1985). The “threshold question” in an equal protection challenge “is the appropriate level of

scrutiny to be applied.” Beniamin v. Jacobson. 124 F.3d 162. 174 (2d Cir. 1997). In addressing the

- 21 -

“threshold question,” the Supreme Court has held that a statute is subjected to heightened scrutiny

when it “burdens a fundamental right.” Id. Clearly, as noted by the Supreme Court, “voting is of the

most fundamental significance under our constitutional structure. Burdick v. Takushi, 504 U.S. 42S,

433 (1992); Dunn v. Blumstem, 405 U.S. 330, 336 (1972) (stating that “before the right (to vote) can

be restricted, the purpose of the restriction and the asserted overriding interests served by it must meet

close constitutional scrutiny”); Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U.S. 533, 562 (1964) (stating that by denying

some citizens the nght to vote, durational residence requirements deprive them of “a fundamental

political right, ... preservative of all rights”) (quoting Yick Wo v. Hopkms. 118 U.S. 356, 370 (1886)).

Accordingly, the rigorousness of a Court’s inquiry into the propriety of a state election law depends

upon the extent to which the challenged regulation burdens Fourteenth Amendment rights. Burdick,

504 U.S. at 434 (1992). Thus, when Fourteenth Amendment rights are “subjected to ‘severe’

restrictions, the regulation must be ‘narrowly drawn to advance a state interest of compelling

importance.’” Id. (quoting Norman v. Reed, 502 U.S. 279 (1992)).

In this case. New' York’s application of § 5-106(2) constitutes more than a severe restriction on

— indeed it is an absolute denial o f— the voting rights of felons who are incarcerated and on parole,

and thus triggers strict scrutiny under Burdick and Dunn. Accordingly, this Court must rigorously

inquire into the propriety of New York’s felon disqualification statute and sustain it only if it concludes

that the statute is narrowly drawn to advance a compelling New York State interest. Id. at 434; see

also Dunn, 405 U.S. at 337 (concluding that “if a challenged statute grants the right to vote to some

citizens and denies the franchise to others, ‘the Court must determine whether the exclusions are

necessary to promote a compelling state interest’”)

Defendants proffer two explanations, neither of which are compelling, for the Legislature’s

1973 amendment that helped to “clearly distinguish[] between felons sentenced to prison and paroled

- 22 -

and felons not sentenced to prison upon conviction.” Defs.’ Mot. at 46-47. First, defendants claim

that the original statute was too “ambiguous, in that it referred to felon's ‘maximum sentence’ and

‘discharge from parole, but did not contain the term ‘imprisonment.’” Id. at 47. Second, defendants

claim that the original statute contained a “mistake that needed to be corrected” because felons not

sentenced to prison were disfranchised for the period during which a sentence could be revoked (which

could be life), and felons who were sentenced to prison w'ere disfranchised for the period of the

sentence (which could also be life). Id.

Although defendants offer reasons as to why the statutory language was altered, they offer

absolutely no reason, much less a compelling reason, for the Legislature’s distinction among similarly

situated felons. It is conceivable, indeed likely, that under New York’s current felon disqualification

scheme, felons who are convicted of identical crimes can either continue to exercise'their right to vote

(if sentenced to probation), or be disqualified from the franchise (if sentenced to incarceration and

parole). This disparate treatment of convicted felons violates the Equal Protection Clause. City of

Cleburne. 473 U.S. at 439; See also Williams v. Tavlor. 677 F.2d 510, 516 (5th Cir. 1982) (holding that

states may not apply facially neutral statutes in a way that arbitrarily distinguishes among — and

thereby denies equal protection to — groups of individuals who have committed a crime).

In this case, New' York State Election Law § 5-106(2) fails strict scrutiny analysis because

defendants have failed to proffer any justification, much less a compelling one as required here, for

treating similarly situated felons differently. Accordingly, the Amended Complaint has more than

sufficiently alleged facts that state a claim under the Equal Protection Clause.

B. New York Election Law § 5-106(2) Fails Strict Scrutiny Analysis

Because It Is Not Narrowly Tailored To The State's Interest.

Even if defendants provided a reason for distinguishing among felons, New York Election Law

§ 5-106(2) violates the Equal Protection Clause because it is not narrowly drawn to advance a state

- 23 -

interest of compelling importance. As the Court in Dunn held, statutes affecting constitutional rights

must be precisely drawn, and tailored to serve their legitimate objectives. Dunn. 405 U.S. at 343

(holding that Tennessee’s durational residence requirement was too crude and imprecise a

classification because it excluded too many residents)(intemal quotations omitted). “If there are other,

reasonable ways to achieve those goals with a lesser burden on constitutionally protected activity, a

State may not choose the way of greater interference.” Id.

Like the statute in Dunn. New York Election Law § 5-106(2) is not narrowly tailored.

Specifically, under § 5-106(2) persons who are convicted of “bribery or of any infamous crime” and

are sentenced to incarceration and parole are not permitted to vote, whereas their counterparts who

have been pardoned, received a suspended or commuted sentence, or been sentenced to probation or

conditional or unconditional discharge are permitted to vote. Amended Complaint, f 60. Accordingly,

New York Election Law § 5-106(2) fails strict scrutiny analysis because it is far from narrowly drawn,