Littles v. Jefferson Smurfit Corporation (US) Petitioners Reply Brief in Opposition to Certiorari

Public Court Documents

October 2, 1995

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Littles v. Jefferson Smurfit Corporation (US) Petitioners Reply Brief in Opposition to Certiorari, 1995. 7f213955-bb9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/7e77f953-49a3-42a6-88b4-4da0385a9055/littles-v-jefferson-smurfit-corporation-us-petitioners-reply-brief-in-opposition-to-certiorari. Accessed February 03, 2026.

Copied!

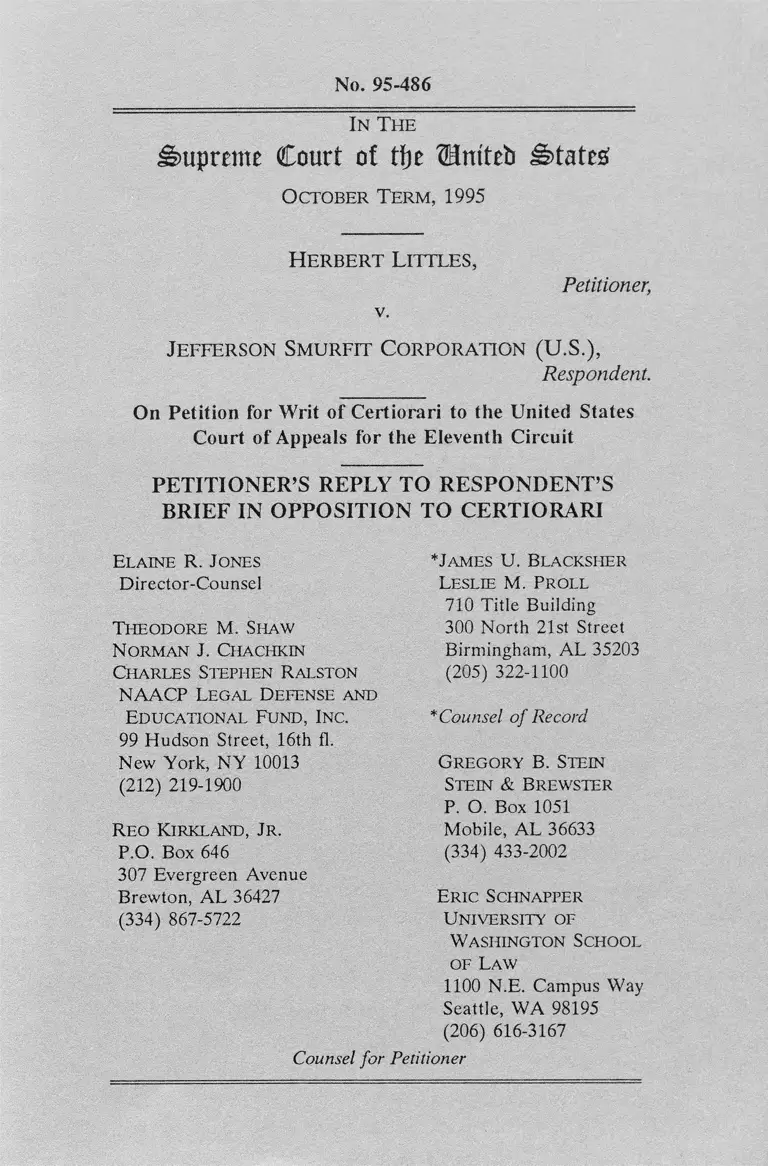

No. 95-486

In T h e

Supreme Court of tfje Hm'teb

O c t o b er T e r m , 1995

Herbert Littles,

Petitioner,

v.

Jefferson Smurfit Corporation (U.S.),

Respondent.

On Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the United States

Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit

PETITIONER’S REPLY TO RESPONDENT’S

BRIEF IN OPPOSITION TO CERTIORARI

Elaine R. Jones * James U. Blacksher

Director-Counsel Leslie M. Proll

Theodore M. Shaw

710 Title Building

300 North 21st Street

Norman J. Chachkin Birmingham, AL 35203

Charles Stephen Ralston (205) 322-1100

NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc. * Counsel o f Record

99 Hudson Street, 16th fl.

New York, NY 10013 Gregory B. Steen

(212) 219-1900 Stein & Brewster

Reo Kirkland, Jr.

P. O. Box 1051

Mobile, AL 36633

P.O. Box 646 (334) 433-2002

307 Evergreen Avenue

Brewton, AL 36427 Eric Schnapper

(334) 867-5722 University of

Washington School

of Law

1100 N.E. Campus Way

Seattle, WA 98195

(206) 616-3167

Counsel for Petitioner

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Table of Authorities ...................................................... i

Petitioner’s Reply to Respondent’s Brief

in Opposition to Certiorari .............................. 1

Conclusion......................................................................... 9

Table of Authorities

Cases:

Conley v. Gibson, 335 U.S. 41 (1 957 )........................5

Demery v. City of Youngstown, 818 F.2d

1257 (6th Cir. 1987)........................................ 2n

General Building Contractors Ass’n, Inc. v.

Pennsylvania, 458 U.S. 375 (1982) ................ 2

Goodman v. Lukens Steel Co., 777 F.2d 113 (3d

Cir. 1985), affd, 482 U.S. 656 (1987) .......... 2n

Hishon v. King & Spalding, 467 U.S. 69 (1984) . . . 5

Miree v. DeKalb County, 433 U.S. 25 (1 9 7 7 ) ......... 5

Scheuer v. Rhodes, 416 U.S. 232 (1974)...................5

Statutes:

42 U.S.C. §§ 1981, 1982 ...................................... 1, 7, 8

1

PETITIONER’S REPLY TO RESPONDENT’S

BRIEF IN OPPOSITION TO CERTIORARI

1.

Although Respondent advances a flurry of factual

arguments, it expressly acknowledges that the decisions of

the courts below actually rested on a legal determination:

a "holding that claims of ‘perpetuation of past

discrimination’ are not actionable under 42 IJ.S.C. §§

1981 and 1982" (Br. Op. 13). As it admits, "the district

court . . . h[eld] that [Petitioner’s] allegation of

[Respondent’s] ‘knowing perpetuation of past

discrimination’ failed to state a claim under §§ 1981 or

1982" (id. at 24) (emphasis supplied). Whether this

holding was correct is precisely the issue which Petitioner

asks this Court to decide; Respondent’s formulation of

the issue decided below is essentially the same as the first

Question Presented in the Petition (Pet. i).

The Petition sets forth half a dozen decisions of

this Court holding, under various circumstances, that

perpetuation of past intentional discrimination violates the

Fourteenth or Fifteenth Amendments (Pet. 19-21).

Respondent does not dispute our characterization of these

decisions, nor deny that the allegations in the instant case

would state a claim if the paper mill in question had been

operated by the State of Alabama rather than by a private

corporation. Instead, Respondent defends the lower

court rulings on the same mistaken legal premise relied

on by the courts below, arguing that the legal standard

under §§ 1981 and 1982 is different from the

constitutional standard embodied in the Fourteenth and

Fifteenth Amendments:

The analyses applicable to suits alleging . . .

invidious, unconstitutional, state-sponsored

violations of civil rights are completely different

2

from those applicable to suits alleging violations of

§§ 1981 and 1982 by private businesses.

(Br. Op. 27) (emphasis supplied.) See also id. at 14

("Constitutional standards are not applicable to this case

under 42 U.S.C. §§ 1981 and 1982"). This was the very

position adopted by the trial court (see Pet. App. 26a).

But that holding and argument are flatly

inconsistent with this Court’s teaching in General Building

Contractors Ass’n, Inc. v. Pennsylvania, 458 U.S. 375, 389-

91 (1982):

[T]he origins of [section 1981] can be traced to

both the Civil Rights Act of 1866 and the

Enforcement Act of 1870. Both of these laws, in

turn, were legislative cousins of the Fourteenth

Amendment . . . . The 1870 Act, which contained

the language that now appears in § 1981, was

enacted as a means of enforcing the recently

ratified Fourteenth Amendment. In light of the

close connection between these Acts and the

Amendment, it would be incongruous to construe

the principal object of their successor, § 1981, in a

manner markedly different from that of the

Amendment itself. . . . Although congress might

have charted a different course in enacting the

predecessors of § 1981 than it did in proposing the

Fourteenth Amendment, we have found no

convincing evidence that it did so.1

1Accord, e.g., Demery v. City o f Youngstown, 818 F.2d 1257, 1260

(6th Cir. 1987); Goodman v. Lukens Steel Co., I l l F.2d 113, 120 (3d

Cir. 1985), affd, 482 U.S. 656 (1987).

3

2.

Respondent asserts (Br. Opp. 18) that

the factual linchpin upon which all of Littles’

arguments in his Petition depends simply does not

exist. Since Littles never proffered any evidence

whatsoever that JSC had a past policy of

discrimination with respect to its supplier contracts,

Littles’ arguments . . . raise issues that are not

presented by the facts of this case, in addition to

being legally unfounded.

This contention is both misleading and incorrect.

In the first place, it overlooks the fact that five

months before the trial took place, the district court had

held that Petitioner’s "knowing perpetuation" contentions

failed to state a claim and that Petitioner could not

present them at trial. In denying Petitioner’s motion for

partial summary judgment,2 the court held that it

need not even determine whether there are any

material disputed factual issues with respect to

plaintiffs motion for partial summary judgment

since the legal claims are not relevant in the

instant action. As discussed above, if he is to

prevail in this case plaintiff must prove that the

defendant intentionally discriminated against him.

Plaintiff cannot prove intentional discrimination by

either theory of proof proposed in his motion for

Petitioner moved for partial summary judgment on the "knowing

perpetuation" claims, "(1) that [Respondent]^ current practices

perpetuate past and present intentional segregation of [Respondentj’s

business environment and (2) that [Respondents criteria for

awarding dealerships ‘lock in’ the effects of [Respondentj’s historical

discrimination" (Pet. App. 24a-25a).

4

partial summary judgment. If these theories tend to

prove anything, they prove discriminatory impact,

which is not actionable under either § 1981 or §

1982.

(Id. at 25a) (emphasis supplied.) Then, at Respondent’s

behest, the court ruled that evidence tending to show

"historical" discrimination by Respondent in awarding

dealer contracts could not be introduced even on the

narrower issue whether Respondent’s most recent decision

not to extend a dealership contract to Littles was

"intentionally discriminatory." In granting, in part,

Respondent’s motion in limine, the court interpreted

Bazemore to stand for the proposition that "evidence of

pre-Act discrimination was relevant to show that it

continued, not to show that the continuation of the

discrimination was intentional" (Pet. App. 31a; see id. at

32a-33a).

Under these circumstances, it is frivolous for

Respondent to complain about the quantum of evidence

of its historic discriminatory dealer contract practices

introduced or proffered at trial; as the district court

remarked during the hearing (addressing Respondent’s

counsel), "you very artfully or forcefully caused me in your

argument, and I think correctly, to close [the door] on

[evidence of perpetuation]" (Tr. 283).3

Second, it is untrue that Petitioner "never proffered

any evidence whatsoever that [Respondent] had a past

policy of discrimination with respect to its supplier

3Indeed, when Petititioner again sought to argue the "knowing

perpetuation" claims in his post-trial motion for equitable relief,

Respondent suggested that sanctions should be awarded against

Petitioner. See Pet. App. 44a-45a.

5

contracts" (emphasis supplied). It is correct that, faced

with the district court’s rulings on his motion for partial

summary judgment and the Respondent’s motion in

limine, Petitioner did not attempt a comprehensive

evidentiary presentation of the "knowing perpetuation"

claims. But Petitioner did in fact make a proffer of

evidence that is probative of historical discrimination in

the timber industry in Alabama, of which Respondent is

a part (Pet. App. 39a-41a). The trial court, as requested

by Respondent, refused to consider that evidence.

Finally, Respondent’s attack on the factual

sufficiency of Petitioner’s "knowing perpetuation" claims

is simply premature. As explained above, the question

presented by the rulings in this case is whether the courts

below erred in holding as a matter of law that Petitioner’s

"knowing perpetuation" allegations "failed to state a claim

under §§ 1981 or 1982" (Br. Opp. 24). In determining

that legal issue, well-pleaded factual allegations are

assumed to be true, Miree v. DeKalb County, 433 U.S. 25,

27 n.2 (1977); Hishon v. King & Spalding, 467 U.S. 69, 73

(1984) (same); Conley v. Gibson, 355 U.S. 41, 45-46 (1957)

(same). "TTie issue is not whether a plaintiff will

ultimately prevail but whether the claimant is entitled to

offer evidence to support the claims," Scheuer v. Rhodes,

416 U.S. 232, 236 (1974).

3.

Preclusion of Petitioner’s opportunity to present

evidence that, in the past, Respondent itself participated

in an industry-wide practice of restricting dealerships to

whites limited Petitioner’s ability to respond to the

company’s factual defense even on the narrow question of

its current motives for refusing to give Petitioner a dealer

contract. Although Petitioner performs all the functions

6

of a wood dealer, procuring 100% of his wood directly

from landowners, cruising the timber, negotiating its sale

to various markets, building roads as necessary, hiring

crews to cut the wood, paying their insurance and

workmen’s compensation, etc. (Tr. 121-23, 147-49, 456-

60), Respondent argued to the jury, as it does in this

Court, that Petitioner’s business is not as large as that of

most dealers with paper mill contracts (Br. Opp. 5, 7).

But Petitioner cannot expand his business without access

equal to that of other dealers to the pulpwood market

within 30 to 50 miles of his Brewton area timber base, as

Respondent concedes [id. at 10). Yet as Respondent tells

this Court, "during the several years prior to trial," it has

not even considered increasing the number of its Brewton

area dealers (id. at 12). The question before this Court

is whether the lower courts committed legal error by

refusing to allow Petitioner to prove that this all-white

dealer monopoly is directly traceable to Respondent’s own

racially discriminatory practices prior to 1979.

4.

As we set out in the margin, even the erroneously

constricted evidentiary record made below does not

support the factual assertions set out in the Brief in

Opposition.4 At this point in the proceedings, however,

4For example, Respondent suggests that few, if any, of its currrent

dealerships are held by the children of its pre-1979 dealers. But

Respondent’s Procurement Manager tesified that one "common way

[new dealers] obtain [a dealership] is through inheritance . . . . Many

times a son will come into an operation that his father had previously

been operating a dealership and his son will take over the business"

(Tr. 548). Respondent cites three examples to suggest that

individuals now routinely become dealers by buying existing

dealerships (Br. Opp. 8). But two of the cited instances are

acquisitions that occurred in the 1960’s (Tr. 674, 720-21), when

7

factual arguments are premature. Petitioner is not

seeking a ruling from this Court that the evidence he

presented was sufficient to establish a "knowing

perpetuation" claim actionable under 42 U.S.C. §§ 1981

(Petitioner alleges) Respondent refused to permit blacks to become

dealers in any fashion, and the third example is in fact that of a firm

inherited by the son of one of the original 1941 co-owners of the

dealership in question (Tr. 849).

Respondent also asserts that subsequent to 1987 it "made

thirteen new roundwood supplier contracts" (Br. Opp. 8, 13, 19)

(emphasis supplied). Respondent’s Procurement Manager explained

at the trial that these thirteen contracts were "different" from the

dealerships at issue in the litigation (Tr. 585). Some were "one time

shot" contracts to buy a single lot of wood from a firm located far

from Brewton (Tr. 489 (Carter Pulpwood; "no ongoing relationship"),

493 (Southern Timber; "a one tract deal"), 493-94 (Wire Grass

Pulpwood; after one transaction, "we ceased doing business")). In a

number of instances the firms receiving these contracts were dealers

for other paper mills operated by Respondent outside of Brewton

(Tr. 497 (firms that "regularly do business" with Respondent’s

Georgia mills)). Several of the one-time contracts were simply

arrangements to swap wood with other major paper mills (Tr. 412-13

("a number of those were wood swaps"), 494). At least one of the

contracts was to buy wood that was owned by International Paper but

which had mistakenly been delivered by a railroad to Respondent’s

Brewton mill (Tr. 418-19, 495-96). None of the firms with which

Respondent made these thirteen contracts were minority-owned.

Finally, Respondent asserts that the Brewton mill "contracted

directly with black-owned businesses for the purchase of wood

products" (Br. Opp. 13 (emphasis supplied); see also id. at 18, 20, 23).

However, Respondent conceded that it had never contracted directly

with any black-owned firm to buy the roundwood which it uses to

manufacture paper (Tr. 562). The transaction cited in the Brief in

Opposition is a single instance prior to 1984 in which Respondent

purchased "wood fuel," a reference to wood chips sold to the Brewton

mill by a black-owned mill in Lowndes County (Tr. 562-63).

8

and 1982. Petitioner seeks only the opportunity to present

and try such a claim to a jury empaneled in the United

States District Court for the Southern District of

Alabama. Nothing that Respondent says in the Brief in

Opposition changes the fact that Petitioner was prevented

from making that claim by the district court’s legal ruling

about the scope of §§ 1981 and 1982.

As we demonstrated in the Petition, that ruling is

important; it is inconsistent with decisions of this Court

and of other Courts of Appeals; it is erroneous; it affects

a major industry in the southern United States; it will

deny to many African-Americans the legal redress that

Congress intended they should have to eliminate the

legacy of past discrimination whose effects continue to

this day; and it merits review by this Court.

9

Conclusion

For the foregoing reasons as well as those set forth

in the Petition, a writ of certiorari should issue to review

the judgment of the court below.

Respectfully submitted,

Elaine R. Jones

Director-Counsel

Theodore M. Shaw

Norman J. Chachkin

Charles Stephen Ralston

NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc.

99 H udson Street, 16th fl.

New York, NY 10013

(212) 219-1900

Reo Kirkland, Jr .

P.O. Box 646

307 Evergreen Avenue

Brewton, AL 36427

(334) 867-5722

* James U. Blacksher

Leslie M. Proll

710 Title Building

300 N orth 21st Street

Birmingham, AL 35203

(205) 322-1100

* Counsel o f Record

Gregory B. Stein

Stein & Brewster

P. O. Box 1051

Mobile, AL 36633

(334) 433-2002

Eric Schnapper

University of

Washington School

of Law

1100 N.E. Campus Way

Seattle, WA 98195

(206) 616-3167

Counsel for Petitioner