Greene v. Podbersky Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the US Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1994

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Greene v. Podbersky Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the US Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit, 1994. f11ee17c-b49a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/7e8085c0-33c7-4a7c-9ac1-a839baf20a69/greene-v-podbersky-petition-for-a-writ-of-certiorari-to-the-us-court-of-appeals-for-the-fourth-circuit. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

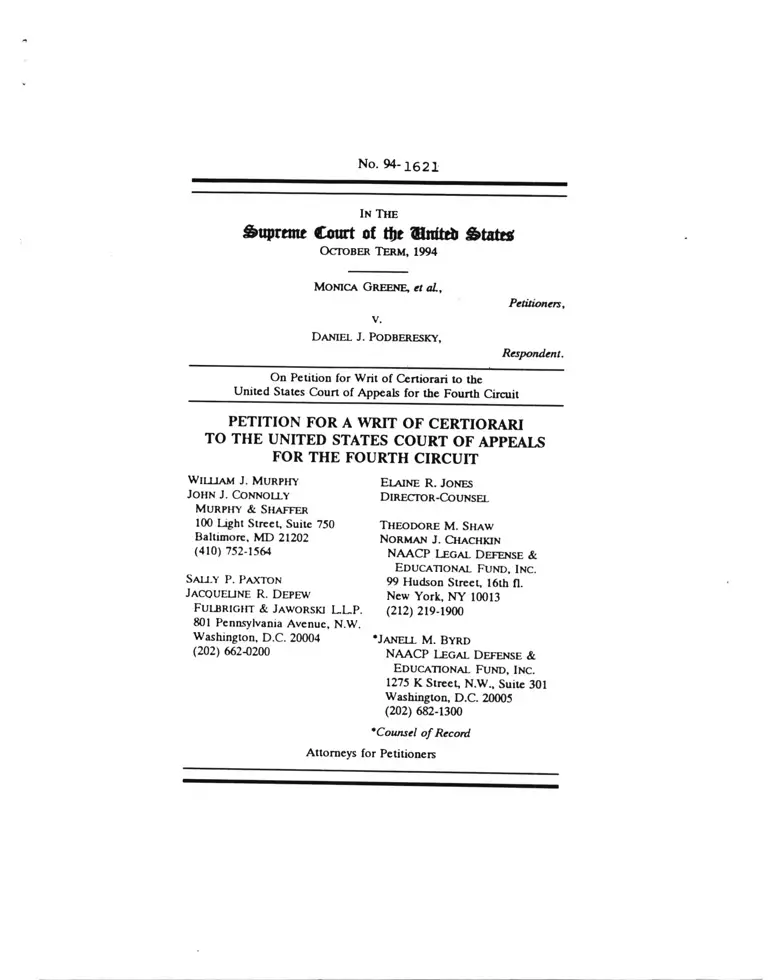

No. 94-1621

In The

&upremt Court of tfte ®Wteb j&tates

October Term, 1994

Monica Greene, et aL,

Petitioners,

V.

Daniel J. Podberesky,

Respondent.

On Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the

United States Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI

TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

William J. Murphy

John J. Connolly

Murphy & Shaffer

100 Light Street, Suite 750

Baltimore, MD 21202

(410) 752-1564

Sally P. Paxton

Jacoueune R. Depew

Fulbright & Jaworski L.L.P.

801 Pennsylvania Avenue, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20004

(202) 662-0200

Elaine R. Jones

Director -Counsel

Theodore M. Shaw

Norman J. Chachkin

NAACP Legal Defense &

Educational Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street, 16th fl.

New York, NY 10013

(212) 219-1900

•Janell M. Byrd

NAACP Legal Defense &

Educational Fund, Inc.

1275 K Street, N.W., Suite 301

Washington, D.C. 20005

(202) 682-1300

*Counsel o f Record

Attorneys for Petitioners

1

Questions Presented for Review

1. Whether a State — that maintained a de jure

segregated higher education system for more than a century;

that for a generation after Brown v. Board o f Education took

few meaningful steps to dismantle the dual system, acting

only when threatened by federal officials with loss of

funding; that had not been released from its remedial

obligations by federal authorities; that continued to operate

the same racially identifiable institutions that existed under

the dual system; and that had been unsuccessful in prior

efforts to increase the low level of African-American

enrollment and graduation at its historically white "flagship"

institution or to alter the longstanding climate of hostility to

blacks on that campus - was justified in 1989, as part of its

desegregation plan, in continuing to award a small number

of scholarships to high-achieving African-American students

at that campus.

2. Whether the court below erred in holding, contrary

to the decision in Bazemore v. Friday, 478 U.S. 385 (1986),

that statistical evidence of underrepresentation lacks any

probative value on the issue of discrimination unless every

imaginable explanatory factor is included in the calculation.

3. Whether the Court of Appeals "departed from the

accepted and usual course of judicial proceeding," Sup. Ct.

R. 10.1(a). disregarded the requirements of Fed. R. Civ. P.

56(c). and misapplied the teachings of this Court when, after

having found that there were genuine disputes about facts

material to the parties cross-motions for summary judgment,

it not only reversed the trial court’s summary disposition in

favor of the defendant parties but also directed that on

remand, summary judgment should be entered for the

plaintiff.

11

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Questions Presented for Review ....................................... j

Table of Authorities......................................................... jjj

Opinions B e low .....................................................................j

Jurisdiction ........................................................................... 2

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved........... 2

Statement of the Case ......................................................... 2

Maryland’s de jure segregated system of

higher education .......................................................3

The Banneker scholarship program ....................... 6

Initial litigation ......................................................... 8

Proceedings after remand .............................. 10

The ruling be low .................................................. 14

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE WRIT

I This Case Presents Issues of Extraordinary

National Importance ........................................... 15

There Is A Compelling Need for

Race-Conscious Remedial Action at UMCP . . . 17

The Approach of the Court Below

Allows Insufficient Room for Necessary

Race-Conscious Remedial S teps...........................21

Page

Ill

TABLE OF CONTENTS (continued)

Pape

II The Decision Below Rests Upon A Wholly

Erroneous View of Statistical Proof in

Discrimination Cases that is Contrary

to the Explicit Teaching of this Court

in Bazemore v. Friday, 478 U.S. 385

(1986), a Ruling in Which This Court

Reversed the Same Court of Appeals for

the Same E r ro r .......................................................24

III Since the Court Below Concluded that

There Were Genuine Disputes about Facts

Material to the Cross-Motions for Summary

Judgment, It Acted Contrary to Fed. R. Civ.

P. 56(c) and the Decisions of this Court

in Directing the Trial Judge to Enter Summary

Judgment for the Plaintiff on R em and ................26

Conclusion.................................. -jo

Table of Authorities

Cases:

Anderson v. City of Bessemer City, 470 U.S.

564 (1985)............................................................. 29

Anderson v. Liberty Lobby, 477 U.S. 242

0 9 8 6 ) .................................................................... 27n

Ayers v. Fordice, No. 4:75CV009-B-0

(N.D. Miss. March 7, 1995) ................................. 19

Bazemore v. Friday, 478 U.S. 385 (1986)___ i, 19, 24, 26

IV

Table of Authorities (continued)

Cases (continued):

Bazemore v. Friday, 751 F.2d 662 (4th

Cir- 1984) ....................................................... 24, 25

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S.

483 (1954)................................................i, 5, 11, 18

Celotex Corp. v. Catrett, 477 U.S. 317 (1986) ............ 27n

City of Richmond v. J.A. Croson Co.,

488 U.S. 469 (1989)......................... 8, 9, 15, 17, 21

Firefighters v. Stotts, 467 U.S. 561 (1984).................. 16n

Geier v. Alexander, 593 F. Supp. 1263

(M.D. Tenn. 1984), afFd, 801 F.2d

799 (6th Cir. 1986) ............................................. 20

Hughes v. United States Dep’t of Education,

Civ. No. N-76-01 (D. Md. June 3, 1985)........... 5n

Johnson v. Transportation Agency, 480 U S

616 (1987)......................................................... 15-16

Knight v. State of Alabama, 787 F. Supp.

1030 (N.D. Ala. 1991), affd in part,

rev’d in part, vacated in part and

remanded, 14 F.3d 1534 (11th Cir. 1994) ......... 20

Local 28 v. EEOC, 478 U.S. 421 (1986)

Local No. 93 v. City of Cleveland, 478

U.S. 501 (1986).........................

V

Cases (continued):

Lujan v. National Wildlife Federation,

497 U.S. 871 (1990)............................................. 27

Mandel v. HEW, 411 F. Supp. 542 (D. Md.

1976), affd, 571 F.2d 1273 (4th Cir.),

cert, denied, 439 U.S. 862 (1978)....................... 5n

McCready v. Byrd, 195 Md. 131, 73 A.2d 8,

cert, denied, 340 U.S. 827 (1950).................... 4-5

Pearson v. Murray, 169 Md. 478, 182 A. 590 (1936) . . . 4n

Pullman-Standard v. Swint, 456 U.S. 273 (1982) ......... 29

United States v. Fordice,__ U.S.___ , 112

S. Ct. 2727 (1992) .................... 6n, 10, 17, 19, 26n

United States v. Louisiana, Civ. No. 80-3300

(E.D. La. Nov. 14, 1994) .................................... 20

United States v. Paradise, 480 U.S. 149 (1987) ......... 16n

Wygant v. Jackson Bd. of Educ., 476 U.S. 267

(1986) ........................................................ 16, 18, 22

Statutes and Court Rules:

7 U.S.C. §§ 301 et seq. (1988 & Supp. V 1993)..............4

20 U.S.C. § 3413 (1988) .................................................. 5n

20 U.S.C. § 3441(a)(3) (1988 & Supp. V 1993) ........... 5n

Table of Authorities (continued)

Page

VI

Statutes and Court Rules (continued):

28 U.S.C. § 1254(1) ........................................................... 2

42 U.S.C. § 2000d .................................................. 2,8,21

1878 Md. Rev. Code, Art. 27, §§ 95, 98 ......................... 3n

1872 Md. Laws Ch. 377 .................................................. 3n

1870 Md. Laws Ch. 311 .................................................... 3n

1868 Md. Laws Ch. 407 .................................................. 3n

1865 Md. Laws Ch. 160 .................................................... 3n

Sup Ct R. 10.1 (a) ........................................................... j

Sup. Ct R. 14.1 ( k ) ..............................................................2n

Fed. R. Civ. P. 5 2 ........................................................... 29

Fed. R Civ. P. 56(c) ............................................. i, 26, 27, 29

Other Authorities:

59 Fed. Reg. 8756 (February 23, 1 994 )......................... 20n

59 Fed. Reg. 4271 (January 31, 1994)............................. 6n

43 Fed. Reg. 6658 (February 15, 1978 )................ 5n, 20n

Md. House J. 1141 (1867)................................................ 3n

Table of Authorities (continued)

Page

Vll

Paee

Table of Authorities (continued)

Other Authorities (continued):

Md. Sen. J. 808 (1867).................................................... 3n

Gil Kujovich, Equal Opportunity in Higher

Education and the Black Public College:

The Era of Separate But Equal, 72 Minn.

L. Rev. 29 (1987)...............................................

Carl T. Rowan, Dream Makers, Dream Breakers

(1993)....................................................................4n

In The

Supreme Court of tfje fSlufttb States

October Term, 1994

No. 94-

Monica Greene, et aL,

v.

Daniel J. Podberesky,

Petitioners,

Respondent.

On Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the

United States Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI

TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

Monica Greene, et aL, defendant-intervenors in the

trial court and appellees below,1 respectfully pray that this

Court issue a Writ of Certiorari to review the judgment of

the United States Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit

in this matter.

Opinions Below

The initial opinion of the District Court is reported

at 764 F. Supp. 364 (D. Md. 1991) and is reprinted in the

‘The parties to this litigation are: Daniel J. Podberesky (the

plaintiff); William E. Kirwan, President of the University of Maryland at

College Park, the University of Maryland at College Park (UMCP) (the

defendants); Monica Greene [the surname is misspelled in the Court of

Appeals' caption], Maudlyn George, on her own behalf and on behalf of

her daughter Allison George, Eileen Heath, Richard A. Dalgetty, Gerard

W. Henry, Maisha Herren, Aletha S. McRae, on her own behalf and on

behalf of her daughter Daletha McRae, and Charles L. Smith, III, on his

own behalf and on behalf of his son, Charles Smith, IV (the defendant-

intervenors).

2

Appendix2 [hereinafter cited as "_a."] at 109a-138a. The

opinion of the United States Court of Appeals for the

Fourth Circuit reversing and remanding is reported at 956

F.2d 52 (4th Cir. 1992) and appears at 96a-108a. The

opinion of the District Court on remand is reported at 838

F. Supp. 1075 (D. Md. 1993) and is found at 34a-95a. The

opinion of the United States Court of Appeals for the

Fourth Circuit, of whose judgment review is sought, is

reported at 38 F.3d 147 (4th Cir. 1994) and is printed at la-

293. The Order of the United States Court of Appeals for

the Fourth Circuit denying timely filed petitions for

rehearing, three Judges dissenting, is reported at 46 F.3d 5

(4th Cir. 1994) and is reprinted at 30a-33a.

Jurisdiction

The jurisdiction of this Court is invoked pursuant to

28 U.S.C. § 1254(1). The Order denying the petitions for

rehearing was entered December 30, 1994 (30a).

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved

This case involves the Fourteenth Amendment to the

United States Constitution and Title VI of the Civil Rights

Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. § 2000d; the text of each is set out at

221a-222a.

Statement of the Case

This suit was brought by Daniel Podberesky, a white

student of Hispanic descent who in 1989 was granted

admission to the Fall, 1990 undergraduate class at the

University of Maryland at College Park ("UMCP") but was

2Although defendant-in tervenors Greene, et al. and defendants

Kirwan and University of Maryland at College Park are filing separate

Petitions for Writs of Certiorari, a single Appendix containing the rulings

below and other materials required by Sup. Cr. R. 14.1(k) has been

prepared for both Petitions.

3

held ineligible to receive a Benjamin Banneker scholarship

to the school because the Banneker program was limited to

African Americans in accordance with a plan adopted by the

State of Maryland to desegregate its institutions of higher

education.3

Maryland’s de jure segregated system of higher education

Maryland has a typically extensive history of

segregation in higher education, dating to Colonial times.4

The first public institutions of higher learning that received

public funds (from 1782 to 1810) were open only to whites

(UX 70 at 138). Later in the 19th century, the State

resumed chartering and funding higher education institutions

and professional schools which were available only to whites

JOne of plaintiffs parents is from Costa Rica. He originally claimed

that the Banneker Program at UMCP should have been available to

persons of Hispanic descent, whom he asserted were also victims of prior

discrimination, as well as to African Americans. This claim was not

passed upon by the District Court nor presented to or decided by the

court below. Cf. 764 F. Supp. at 378, 136a-137a (rejecting similar claim

with respect to Key Scholarship program).

‘State authorities admit that prior to 1865, despite having the largest

number of free blacks of any southern state (UX 70 at 38), all of the

educational opportunities provided by the State were "in favor of the

white race" - there being no colleges for blacks or evidence that the

white institutions enrolled blacks (IX 4 at 127). (Citations in the form

"u x and IX are to exhibits to the defendants’ and defendant-

mtervenors’ 1993 Motions for Summary Judgment.)

Following the Civil War, the legislature of the State of Maryland

refused to ratify the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution, Md.

Sen. J. 808 (1867), Md. House J. 1141 (1867), and in 1870 enacted a new

Public Education Act extending free public education to "[a]ll white

youth between the ages of six and twenty-one years" (previously limited

to age nineteen) and maintaining separate schools for "colored children"

between the ages of six and twenty. 1870 Md. Laws Ch. 311 (Public Edu

cation Act of 1870); see also 1865 Md. Laws Ch. 160; 1868 Md. Laws Ch.

407; 1872 Md. Laws Ch. 377; 1878 Md . Rev. Code, Art. 27, §§ 95, 98.

4

(id. at 138-39), including, in 1859, the Maryland Agricultural

College (now UMCP), which became the State’s land-grant

institution under the 1862 Morrill Act, 7 U.S.C. §§ 301 et

seq. (1988 & Supp. V 1993). The school was open only to

white males until 1916, when it admitted white females.

(UX 70 at 141-42). Between 1866 and 1909 four higher

education institutions for blacks, all founded by religious

groups, were chartered by the State but received little if any

state aid (id. at 141).5

By 1937, the State Commission on the Higher

Education of Negroes found that of the four schools

providing education for blacks, only one was accredited and

that instruction in all was "considerably inferior" to that in

the white institutions; the Commission recommended that

the only state college for blacks, Princess Anne Academy,

"had far better be abandoned altogether than continue its

present pretense as a college" (IX 4 at 11-12, 26-27). In

response to pressure to address these inequities or

desegregate, Maryland chose to pay for a limited number of

African Americans to attend out-of-state institutions rather

than inegrate its own colleges and universities (IX 5 at 93-

95). Finally, in the early 1950’s several blacks successfully

sued for admission to UMCP. E.g., McCready v. Byrd 195

Even after the 1890 Morrill Act required Maryland to designate a

land-grant college for African Americans in order to receive federal land-

grant aid, it appears that the State failed to allocate funds to the black

institution, instead allowing all state funding to flow to UMCP (IX 4 at

136).

®The first court challenge to Maryland’s de jure segregated higher

education system came after the State denied Thurgood Marshall

admission to its law school, see Carl T. Rowan, Dream Makers,

Dream Breakers 45-46 (1993). After graduating from Howard Law

School. Marshall won an order directing the admission of Donald Murray

to the University of Maryland Law School. Pearson v. Murray 169 Md

478, 182 A. 590 (1936). V

5

Md. 131, 73 A.2d 8, cert denied, 340 U.S. 827 (1950); see

also UX 70 at 154; IX 6.

After the decision in Brown, University officials voted

in 1954 to remove restrictions on black enrollment (UX 70

at 155), but took few steps in the ensuing two decades to

change the racially dual character of the higher education

system. Only when threatened with loss of funding by the

federal government’s Office for Civil Rights ("OCR") in the

1970’s and early 1980’s did Maryland begin to take steps to

dismantle its dual system.7

In 1985, Maryland proposed a higher education

desegregation plan that OCR accepted. The plan reflected

OCR’s strong encouragement of using "other-race" financial

assistance (aid made available to students who are members

of groups that are underrepresented at racially identifiable

institutions operated under the dual system) as a

desegregation tool. For the period 1985-89, over $7,900,000

'In 1969, the Office for Civil Rights of the United States Department

of Health. Education and Welfare notified Maryland that it was

continuing to operate a racially segregated system of higher education in

violation of Title VI (UX 71; see 43 Fed. Reg. 6658 n.2 (Feb. 15, 1978)).

In so doing. OCR noted the racial identifiability of Maryland’s colleges:

three formerly white state colleges and UMCP had enrollments that were

approximately 99% white, while the three formerly black schools and the

Princess Anne campus of the University of Maryland had enrollments

approximately 92% black (UX 71).

In 1975, the State brought an action against OCR to forestall

formal Title V] enforcement proceedings, Mandel v. HEW, 411 F. Supp.

542 (D. Md. 1976), offd, 571 F.2d 1273 (4th Cir.), cert, denied, 439 U.S.

862 (1978). That litigation was dismissed in 1985 when OCR accepted

a five-year desegregation plan from the State. Stipulation of Dismissal

at 2, Hughes v. United States Dep’t o f Education, Civ. No. N-76-01 (D.

Md. June 3, 1985). (The responsibilities of HEW* Office for Civil

Rights were transferred to the Office for Civil Rights of the U.S.

Department of Education following its establishment in 1980, 20 U.S.C.

§ 3441(a)(3) (1988 & Supp. V 1993); see also 20 U.S.C. § 3413 (1988).)

6

in other-race financial assistance was provided to students at

all institutions; $2,387,065 at historically black schools and

$5,586,103 at other institutions.8 Although black enrollment

at several historically white colleges, particularly UMCP,

increased during the life of the plan, by 1990 more than 60%

of black full-time undergraduate students in Maryland public

colleges still attended one of the four historically black

institutions (UX 43, Table B-8). African-American students

made up 11.2% of UMCP’s enrollment that year (UX 21).9

The Banneker scholarship program

The Banneker Program was originally established by

UMCP in 1978 as part of the State of Maryland’s efforts to

comply with the OCR requirement that it dismantle its

segregated system of higher education. In 1980, OCR

concluded that the State s efforts were still inadequate and

ineffective. The agency specifically directed Maryland’s

attention to the low enrollment of black students at

traditionally white colleges, including UMCP (UX 81, at 9-

10). Five years later, OCR explicitly recommended that the

State increase the number and amount of need- and merit-

based scholarships designated for African Americans

enrolled at UMCP (UX 84, attachment at 3).

The Banneker scholarships originally provided $1000

per year for two years to minority students at UMCP. They

were subsequently expanded to provide four years’ * *

'Appendix C lo Brief of Amicus Curiae United States Department of

1 Education, Podberesky v. Kirwan, Civ. No. JFM-90-1685 fD Md filed

July 27. 1993).

*OCR has not yet made a determination whether Maryland’s higher

education system is in compliance with the requirements of Title VI.

The agency has announced that it will apply the standards of this Court’s

ruling in United States v. Fordtce,__ U.S.___ , 112 S. Ct. 2727 (1992), to

pending Title VI evaluations of the expired plans of six states, including

Maryland. 59 Fed. Reg. 4271-72 (Jan. 31, 1994).

7

undergraduate support (IX 20, at 231a) and in 1981 to

provide full (in-state) tuition (UX 59, Chart 1). In 1988,

eligibility for the Banneker program was restricted to

African-American students and the amount of aid was

increased to provide support for all costs normally associated

with matriculation at UMCP. However, in the 1990-91

school year, the cost represented only one per cent of total

financial aid available to UMCP students (Id; UX 62; see

also 838 F. Supp. at 1077, 35a-36a).

At the time plaintiff applied, eligibility for Banneker

scholarships was restricted to African-American students

who had been admitted to UMCP and who had a minimum

high school grade-point average of 3.0 and minimum SAT

score of 900.10 UMCP selected, from among applicants

meeting these criteria, those who also demonstrated

characteristics that had been found to correlate better than

grades and standardized test scores with retention and

graduation of black students at UMCP (UX 47 11 17

[affidavit of Banneker Committee chair]; see also UX 15 at

4 [study by UMCP professor]; UX 6 at 14-15 [study by Dr.

Walter Allen, UCLA, commissioned for this case]).

The selection process brought to UMCP, as

Banneker Scholars, black students who have completed their

studies and graduated with honors at rates closest to those

for white students (UX 43 at 13 [study by Dr. William Trent,

University of Illinois]). Recipients of Banneker scholarships

do far more than just graduate with honors; they also serve

as tutors and mentors to other African-American students at

UMCP and frequently participate in the school’s recruiting

efforts that are directed toward high schools with substantial

1 838 F. Supp. at 1077, 35a-36a. UMCP. also awards lull-cost, merit-

based Francis Scott Key scholarships without any racial restriction. Id.

at 1095, 83a. However, Mr. Podberesky did not qualify for a Key

scholarship for 1990. 764 F. Supp. at 377, 134a.

8

black student enrollments (UX 6 at 21; UX 9 f 31, UX 12

II 14 [affidavits of Director and Assistant Director of

Undergraduate Admissions at UMCP]). A study of African-

American students’ persistence and graduation from 1974

through 1992 indicated that the Banneker scholarships were

an important factor in increasing blacks’ enrollment and

success at UMCP (UX 43 at 18 [Trent]). As the District

Court found (838 F. Supp. at 1094-95, 82a-83a):

Continuation of the Banneker Program thus serves to

enhance UMCP’s reputation in the African-American

community, increase the number of African-

American students who might apply to the

University, improve the retention rate of those

African-American students who are admitted and

help ease racial tensions that exist on the campus.

Initial litigation

Respondent’s complaint alleged that restriction of

Banneker scholarships in 1990 to black students violated,

inter alia. the Fourteenth Amendment’s Equal Protection

Clause and Title VI of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, 42 U.S.C.

§ 2000d. Following discovery, the parties (then limited to

the respondent, and UMCP and its President) filed cross-

motions for summary judgment. On May 15, 1991, the

District Court granted summary judgment in favor of the

University. It held that while the operation of the Banneker

program was subject to the "strict scrutiny" analysis of City

of Richmond v. J.A. Croson Co., 488 U.S. 469 (1989), the

requirements of that analysis were satisfied.

The district court ruled that Maryland had a

compelling justification for adopting the Banneker program

as a means of remedying its own prior discrimination against

African Americans in the operation of its higher education

system. The court pointed to OCR’s findings that Maryland

violated Title VI, to the protracted enforcement proceedings,

9

and to the fact that the federal enforcement agency had not

yet made a determination that the State had met its

remedial obligations under Title VI. 764 F. Supp. at 371-73,

122a-125a. The court stated that "there must be continuing

effects of past discrimination to justify a race-conscious

remedy," id. at 374-75, 129a, and that plaintiff offered "some

evidence" that by 1989 the State’s implementation of its 1985

desegregation plan had been effective at UMCP. Neverthe

less, the court found that there was no triable issue as to

whether UMCP officials in 1989 had a "strong basis in

evidence" for concluding that the effects of their prior

discrimination had not yet been eradicated, particularly in

light of the fact that OCR had not made a determination to

the contrary. Id. at 372, 123a [citing Croson, 488 U.S. at

500], 375, 130a. It also held the Banneker Program to be

"narrowly tailored," as required by Croson and other rulings

of this Court. Id. at 375-76 (130a-133a).

The Court of Appeals reversed, because it

determined that the district court "failed to make a

[sufficiently] specific finding" that there were continuing

effects of the prior discrimination at the time respondent

was held ineligible for a Banneker scholarship in 1989. 956

F.2d at 57, 106a. It emphasized the need for a careful

review of the facts (id. ):

In determining whether a voluntary race-based

affirmative action program withstands scrutiny, one

cannot simply look at the numbers reflecting

enrollment of black students and conclude that the

higher educational facilities are desegregated and

race-neutral or vice versa. It may very well be, given

the complexities of institutions of higher education

and the limited record on appeal, that information

exists which provides evidence of present effects of

past discrimination at UMCP, but no such evidence

was brought to our attention nor is it part of the

10

record. . . . Should no further evidence be available

upon remand, summary judgment for appellant

would be appropriate.

The Court of Appeals did not reach the "narrowly tailored"

issue, id. at 57 n.7, 107a n.7.

Proceedings after remand

When the case returned to the District Court in 1992,

the present Petitioners (six African-American UMCP

student recipients of Banneker scholarships and two African-

American high school students who were potential applicants

to UMCP) were permitted to intervene as defendants. The

University of Maryland conducted an extensive

administrative fact-finding review of the Banneker program

in which all parties to this litigation were invited to

participate. On April 26, 1993, the University issued a

formal Decision and Report (139a-220a), accompanied by

extensive supporting exhibits, which concluded that in 1989

and in 1993 continuing effects of the racially discriminatory

dual system persisted at UMCP and influenced the

enrollment decisions of African-American students (c/.

Fordice. 112 S. Ct. at 2737).

These materials, along with additional affidavits,

declarations and documentary evidence, were presented to

the District Court in connection with cross-motions for

summary judgment again filed by both sides in the case,

following an additional discovery period.11 On November

“The defendant parties deposed both of plaintiff's designated expert

witnesses, neither of whom indicated familiarity with the facts and

circumstances relating to the Maryland higher education system in

general, or UMCP in particular. For example. Dr. Carl Cohen admitted

that he had "conducted no independent study of . . . the extent to which

past discriminatory actions with lingering effects were at any time

eliminated as a consequence of the remedial actions taken by the

University of Maryland" (IX 46 at 58) and that "I have been veiy careful

11

18, 1993, the District Court again granted summary

judgment against respondent Podberesky. 838 F. Supp.

1075, 34a. In its opinion, the court first summarized the

extensive history of official discrimination against African

Americans in Maryland, including lack of access to

opportunities for higher education; it then described the

State’s painfully slow response both to Brown and to the

federal government’s attempts to have the State dismantle its

dual system of higher education. Id. at 1077-81, 36a-48a.

The court thereafter turned to the four specific effects of the

prior discrimination that the University had concluded, in its

Decision and Report, persisted at UMCP: (1) the school’s

reputation within the black community as an institution at

which African-American students were not welcome and

would not succeed; (2) continuing underrepresentation of

blacks in the student body; (3) persistent low retention and

graduation rates of African-American students at UMCP;

and (4) a racially hostile campus climate. Id at 1082, 50a.* 12

Based upon the affidavits and declarations of University

officials, faculty and students, and others, statistical data,

in my previous answers to explain that I cannot speak with authority

concerning the causal connections between previous events and the

present" (id. at 124). Dincsh D’Souza testified that he had reviewed only

one document prior to preparing his affidavit (IX 47 at 69-72, 78-80).

On the basis of this discovery, the defendant parties moved to exclude

evidence from plaintiffs’ "experts," but the District Court did not rule on

the motion and allowed affidavits from both individuals to be submitted

with plaintiffs cross-motion for summary judgment.

l2Defendant-intervenors also argued that the low number of black

faculty at UMCP was traceable in part to the long-maintained dual

system and exclusion of African-American students from opportunities

for study leading to academic careers. The District Court did not address

this argument, except to note that the "absence of African-American

members of the faculty to serve as mentors" was a "significant

contributing factor[]" to low retention rates for African-American

students, 838 F. Supp. at 1091-92, 74a-75a.

12

and scholarly studies conducted at the defendant parties’

request, the District Court concluded that "all four of

UMCP’s findings are supported by strong evidence." 838 F.

Supp. at 1083, 52a. Specifically, the trial court determined

that

(a) there was substantial evidentiary

justification for UMCP’s conclusion in 1989 that the

school continued to be viewed, in Maryland’s black

community, as a racially exclusionary institution

based upon the personal experience and exposure of

parents and other adults to its long history of

segregation, resistance to integration, and prevalent

atmosphere of hostility to African Americans on the

campus, 838 F. Supp at 1084-87, 54a-62a;

(b) the most appropriate statistical

comparisons, taking into account UMCP’s highly

flexible admissions process,13 indicated that African

Americans continued to enroll as undergraduates at

UMCP in numbers significantly below what might

n Although UMCP considered whether applicants had high school

diplomas, had completed a set of specified secondary education course

offerings, had taken the SAT or ACT tests (and, if so, the scores they

had achieved), and what their high school grade-point average was, each

of these criteria was applied with great flexibility; indeed, applicants were

admitted without any requirement that they meet any particular standard

or level of performance as to any or all of these factors, but rather based

upon individual assessment of their likelihood of succeeding in the

school’s program. (Decision and Report at 17, 173a-175a; UX 9 11 6-9;

IX 36 at 6-7, 17-19, 22-25; UX 108 [Admissions Criteria].) The District

Court correctly concluded that "in fact, the University does not have rigid

minimum admissions requirements," 838 F. Supp. at 1087, 64a.

Nevertheless, the court did not "entirely disregard[]" the criteria but

rather held that then existence and impact on the majority of admissions

decisions required comparison of African-American enrollment rates with

a pool more restricted than simply Maryland high school graduates id.

at 1089, 68a-69a.

13

reasonably be anticipated at Maryland’s flagship

institution in the absence of its racially exclusionary

past and continuing negative reputation, id at 1087-

89, 63a-69a;

(c) there was "a strong evidentiary basis for

th[e] finding" that black undergraduate students

admitted to UMCP are disproportionately less likely

than whites with similar credentials to remain

enrolled and to graduate, due in part to factors

connected with the University’s prior discrimination,

id. at 1091-92, 72a-75a; and

(d) "there is a strong evidentiary basis in the

record to support" the finding that on the UMCP

campus, a climate of hostility to blacks (inconsistent

though it may be with the University’s contemporary

official policies and pronouncements) exists that in

part reflects problems created by UMCP’s past

exclusion and discriminatory treatment of African

Americans, id. at 1092-94, 75a-81a.

The District Court also found, as it had initially, that

the Banneker Program was "narrowly tailored" to address

these continuing effects of prior discrimination because the

University’s experience with "race-neutral" measures had

been unsatisfactory, because the University will reconsider

the need for its continuation at least every three years,

because the proportion of UMCP financial aid subject to

this racial restriction is minute, and because the scholarship

program, while it appears to be succeeding (over time) in

eliminating the continuing effects of discrimination, operates

without impact upon the decision whether or not to admit

any non-African-American applicant to the school, id. at

1095-96, 83a-87a. The court accordingly granted summary

judgment in favor of defendants and defendant-intervenors

and denied Podberesky’s cross-motion.

14

The ruling below

The Court of Appeals again reversed. It disagreed

with the trial court about whether the University was

entitled to summary judgment on any issue. Interpreting the

District Court’s finding about UMCP’s reputation in the

black community as relating solely to pre-1954 absolute

exclusion of undergraduate African-American students from

the school, it ruled that as a matter o f law this effect, even if

traceable to the State’s prior discrimination, could not justify

a race-conscious remedy such as the Banneker Program. 38

F.3d at 154, 10a. The panel also disagreed with the District

Court’s conclusion that the hostile racial climate at UMCP

was traceable to the dual system because "the [evidence]

. . . do[es] not necessarily implicate past discrimination on

the part of the University, as opposed to present societal

discrimination," which was an insufficient ground for

employing a race-conscious remedy, id. at 154, 11a.

With respect to the underrepresentation of African

Americans in UMCP’s student body, and retention and

graduation rates, the panel held that summary judgment for

defendant parties was improper because plaintiff had

presented sufficient evidence to raise triable factual issues on

these claims, id. at 155-57, 13a-18a.14 The panel went

further, however, holding that plaintiff’s cross-motion for

summary judgment should have been granted. In its view,

there were several reasons the Banneker Program could not

be said to be narrowly tailored, even assuming arguendo that

defendants and defendant-intervenors had established that

Despite the District Court’s finding, supported by uncontroverted

evidence, that there were no rigid qualifications for admission to UMCP,

see supra note 13, the panel ruled that "the district court should have

determined what the effective minimum criteria for admission were by

determining the lowest GPA and SAT scores achieved by admittees to

the University that year," id. at 157 n.5, 16a n.5.

15

underrepresentation of blacks at UMCP and their

disproportionate attrition were remnants of the State’s past

discrimination. Id. at 157-58, 18a-19a. First, according to

the panel, "[h]igh achievers" - such as recipients of

Banneker scholarships - "are not the group against which

the University discriminated in the past," id. at 158, 20a.

Second, the Banneker Program is open to non-residents of

Maryland, id. at 158-59, 20a-21a. Further, the degree of

underrepresentation (and, hence, the necessary duration of

the program) cannot be sufficiently ascertained because

the reference pool must factor out, to the extent

practicable, all nontrivial, non-race based disparities

in order to permit an inference that such, if any,

racial considerations contributed to the remaining

disparity,

id. at 160, 24a. Finally, the panel asserted, notwithstanding

the affidavits and declarations of University officials, that the

State had not shown that race-neutral alternatives to the

Banneker Program had ever been employed in an effort to

reduce attrition of African Americans,id. at 160-61, 26a-27a.

Rehearing en banc was denied on December 30,

1994. three judges dissenting without opinion (30a-33a).

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE WRIT

I

This Case Presents Issues of Extraordinary

National Importance

As the preceding description indicates, this case is

unlike any of this Court’s recent decisions in the area of

voluntary affirmative action, e.g., City o f Richmond v. J.A.

Croson Co., 488 U.S. 469 (1989); Johnson v. Transportation

16

Agency, 480 U.S. 616 (1987);15 Wygant v. Jackson Bd. o f

Educ., 476 U.S. 267 (1986). In each of those cases, the

existence of prior discrimination by the governmental

agencies involved was either not admitted or not proven, and

the issue before this Court concerned the nature of the

State’s interest and the showing ~ short of proving past

discrimination - that would be necessary in order to justify

the affirmative consideration of race or gender.16

Here, in contrast, Maryland’s operation of separate

institutions of higher education for blacks and whites, and its

long delay after 1954 in taking any meaningful action toward

dismantling that system, is undisputed. The genesis of the

Banneker scholarship program in the course of Title VI

administrative proceedings involving the desegregation of

Maryland’s university system is also undisputed. Thus the

remedial purpose motivating the original adoption of the

Banneker Program is unquestioned. The Court has not yet

addressed the contours of permissible affirmative action in

15Of course, Johnson involved only a Title VII claim, and not the

Equal Protection Clause, 480 U.S. at 620 n2, and the Court’s opinion

there applied a standard of justification for affirmative action that is less

rigorous than that applicable in the constitutional context, see id. at 632-

33 ("manifest imbalance" need not rise to level of "prima facie" case).

However, the analysis is very similar to that in constitutional challenges,

and Justice O’Connor, concurring m the judgment, specifically applied

that analysis based upon her conclusion that the "'pnma facie" standard

was satisfied on the facts of Johnson, 480 U.S. at 656.

The instant case also differs from decisions involving the scope of

the federal courts equitable authority to impose race-conscious remedies,

e.g.. United States v. Paradise. 480 U.S. 149 (1987); Local No. 93 v. City

of Cleveland, 478 U.S. 501 (1986); Local 28 v. EEOC, 478 U.S. 421

(1986); Firefighters v. Stotts, 467 U.S. 561 (1984). Cf. Local No. 93, 478

U.S. at 526 (parties may consent to broader relief than court is

empowered to order).

17

such circumstances.17 It is imperative that it do so in this

case, for lacking such guidance, the panel below

mechanically applied the strict scrutiny test of Croson, a case

in which no remedial purpose could be discerned, to

diametrically contrary conditions.

There Is A Compelling Need for Race-

Conscious Remedial Action at UMCP

Podberesky (and the panel below) focused their

criticism upon the University’s determination that effects of

the dual system endured at UMCP and justified continued

operation of the Banneker Program. As developed in the

Decision and Report issued by the University in 1993, and in

the evidence put before the District Court, salient

characteristics of UMCP’s historic mission and operation as

a whites-only school have continued to affect the enrollment

and retention of African Americans at the institution and to

contribute to its racial identifiability, see supra pp. 6, 12-13;

cf. Fordice, 112 S. Ct. at 2736-38 (policies and practices

conceived in the era of the dual system may restrict or

influence students’ current institutional choices). For

example, there was abundant evidence that UMCP

continued to be burdened by its reputation as a once-totally

segregated institution that only grudgingly admitted black

students and which failed to provide them with the same

kind of academic and other support systems available to

whites,1*' and that African-American students still suffered

Seventeen southern and border states operated de jure segregated

systems of higher education, faced federal pressure to dismantle those

systems, and continue to struggle to eliminate the harmful remnants of

their existence. See, e.g., Gil Kujovich, Equal Opportunity in Higher

Education and the Black Public College: The Era o f Separate But Equal,

72 Minn. L. Rev. 29 (1987).

"The panel’s view that UMCP’s reputation in the African-American

community stems solely from pre-1954 practices, 38 F3d at 154, 10a,

1 8

much higher attrition rates than whites. The University

designed the Banneker Program not merely to increase black

enrollment — as a simple admissions preference might have

done -- but to address these underlying problems in a

positive manner and change its reputation in the African-

American community. Indeed, the University’s Banneker

Program minimizes its impact on non-black third parties

because it is applicable only after admissions decisions are

made and because it represents a very small proportion of

total financial aid available to UMCP students.

Such carefully tailored voluntary actions by State

officials to overcome the legacy of their constitutional

violations deserve to be encouraged if the nation as a whole

is ever to overcome its sorry history of discrimination. "The

Court is in agreement that, whatever the formulation

employed, remedying past or present racial discrimination by

a state actor is a sufficiently weighty state interest to warrant

the remedial use of a carefully constructed affirmative action

program." Wygant, 476 U.S. at 286 (O’Connor, J.,

concurring in part and concurring in the judgment).

The panel below acknowledged that patterns of

enrollment bv race that originated prior to Brown and

cannot be squared with the evidence. For example, the District Court

quoted from the affidavit of a UMCP official (UX 10 II 8) recounting

conversations with teachers, principals and counsellors in Baltimore in

which they reported not only their own negative experiences at College

Park, but also -their former students[’j, whose feedback over the years

indicated that life at UMCP had not significantly changed over time," 838

F. Supp. at 1085, 57a-58a. Similarly, a series of focus group interviews

with randomly selected black parents indicated that contemporary racial

incidents and the hostile climate at UMCP were as important as

historical events tn shaping the school’s negative reputation in the

African-American community (UX 7 at 8-14, 20-27 [report of Dr. Joe R.

Fcagin]), which led many parents to advise black high school students not

to apply to UMCP (id. at 31-34).

19

continued into the 1970’s persist in Maryland’s higher

education system, see infra note 23, suggesting that

institutional choice in the State is not yet "wholly voluntaiy

and unfettered," Fordice, 112 S. Ct. at 2737, citing Bazemore

v. Friday, 478 U.S. 385, 407 (1986) (White, J., concurring).

But the panel deprived the State of authority to address

lingering influences upon choice. It held the University was

powerless to undertake the Banneker Program for the

purpose of extirpating its negative reputation within the

African-American community and it trivialized the State’s

concern. Even if UMCP’s negative reputation was

attributable to prior segregation, the panel said, it was based

upon "mere knowledge of historical fact [and] is not the kind

of present effect that can justify a race-exclusive remedy. If

it were otherwise, as long as there are people who have

access to history books, there will be programs such as this

one." 38 F.3d at 154, 10a.

But this Court recognized explicitly in Fordice that a

state that formerly operated a dual system may "need . . .

[to] take additional steps to ameliorate [racial] identifiability"

that persists at its higher education institutions. 112 S. Ct.

at 2736 n.4. As lower courts in higher education

desegregation cases have perceived, if the remedy is to be

effective such steps must include race-conscious measures.

E.g., Memorandum Opinion and Remedial Decree, Ayers v.

Fordice, No. 4:75CV009-B-0 (N.D. Miss. March 7, 1995), at

167 n.365. See id. at 105-06, 108-12, 118 (approvingly noting,

in discussion of steps taken to increase diversity and improve

the racial climate,19 the provision of special financial aid

“The Avers court said: "Ghosts of the past, which potentially have

segregative effects by stimulating a climate nonconducive to diversity on

the historically white campuses, include the lack of minority faculty as

well as their absence in significant numbers in the top positions within

Mississippi’s academia . . . to some extent . . . a product of the de jure

segregation," Avers, slip op. at 117-18. Cf. supra note 12.

20

and scholarship opportunities for blacks at historically white

institutions in Mississippi), 178-79 H1I 6, 9 (directing state to

establish $5 million endowments for purposes of increasing

racial diversity at Jackson State University and Alcorn State

University, including by establishing other-race scholarship

programs); Settlement Agreement, appended to Minute

Entry, United States v. Louisiana, Civ. No. 80-3300 (E.D. La.

Nov. 14, 1994), at 19 11 21 ("significant financial assistance"

to be provided for African-American law students at LSU

Law Center), 21 U 22.3 ($900,000 per year to be provided for

scholarships for other-race doctoral candidates at

predominantly white institutions), 22 11 22.f ($700,000 per

year for other-race graduate scholarships to be provided at

Southern University campuses); Knight v. State o f Alabama,

787 F. Supp. 1030, 1292-97 (N.D. Ala. 1991) (favorably

describing other-race financial aid offered to promote

increased African-American enrollment in traditionally white

Alabama institutions of higher education), affyd in part, rev’d

in pan, vacated in pan and remanded on other grounds, 14

F.3d 1534 (11th Cir. 1994); Geier u Alexander, 593 F. Supp.

1263, 1270 (M.D. Tenn. 1984) (approving pre-professional

program and scholarships for black students as part of

settlement of issues in higher education desegregation suit

between private plaintiffs and state, and binding intervenor

United States to terms), affd, 801 F.2d 799 (6th Cir

1986).20

^ h e U.S. Department of Education and its predecessor agency have

approved and encouraged the use of other-race scholarship programs in

state desegregation efforts pursuant to Title VI, 42 U.S.C. § 2000d

(1994). See Revised Criteria Specifying the Ingredients o f Acceptable Plans

to Desegregate State Systems o f Higher Education, 43 Fed. Reg. 6658, 6662

(Feb. 15, 1978), t H.H.; UX 84, attachment at 3 (1985 OCR

recommendation that Maryland increase number and amount of other-

race scholarships); 59 Fed. Reg. 8756 (February 23, 1994).

21

The Approach of the Court Below Allows Insufficient

Room for Necessary Race-Conscious Remedial Steps

The decision below subjects Maiyland’s use, in 1989,

of these same tools not just to "strict scrutiny," but rather to

a "presumption" of unlawfulness, see 38 F.3d at 152, 6a. In

spite of the undisputed background of segregation and

official discrimination at UMCP and in spite of the

unquestioned remedial purpose that led to the creation of

the Banneker Program, the court below treated the State of

Maryland as if it were the City of Richmond in the Croson

case, lacking any documented history of past discrimination

in the domain of its affirmative action plan. Viewed in that

light, it is hardly surprising that the Banneker Program -

once uprooted from the legacy of segregation that spurred

its creation -- was found not "narrowly tailored." Applying

a presumption of illegality even in cases of proven prior

discrimination leaves virtually no room at all for remedial

affirmative action, no matter how carefully structured. It

amounts to "a rule of automatic invalidity for racial

preferences in almost every case," Croson, 488 U.S. at 519

(Kennedy, J., concurring in part and concurring in the

judgment), and it presents states that formerly operated

racially dual systems with a severe dilemma - they can do

nothing and wait to be sued by African-American citizens or

the federal government, or they can attempt to address their

problems frontally and creatively and risk being sued by

whites, who already enjoy disproportionate access to the

benefits of public higher education.

The effect of applying a presumption of unlawfulness

even to a remedial affirmative action plan adopted after an

unambiguous finding of past discrimination is illustrated by

the panel’s cramped and error-laden analysis of features of

the Banneker Program that it found to be indicators that the

program was not "narrowly tailored." For example, the

panel ruled that ”[i]f the purpose of the [Banneker] program

22

was to draw only high-achieving African-American students

to [UMCP], it could not be sustained. High achievers,

whether African-American or not, are not the group against

which the University discriminated in the past." 38 F.3d at

158, 20a. Not only does this pronouncement lack any

support whatsoever in the record of this litigation -- indeed,

the record contradicts it - it is flatly belied by a history of

pre-1954 educational segregation in the southern and border

states of this nation that is so well established that it is

subject to judicial notice. All African-Americans,

notwithstanding their academic potential or their place of

residence, were barred from Maryland’s flagship institution

and its professional schools for more than a century. Of

course, the tragedy of this history is that we can never know

how many more Thurgood Marshalls might have emerged

from Maryland to enrich the State’s citizeniy and the history

of our country if there had been equal educational

opportunity even for "high achievers" who were black.

Moreover, the purpose of the Banneker Program is

not solely to benefit high-achieving African Americans.

Banneker Scholars serve as positive role models and

mentors, helping to break down racially hostile attitudes at

UMCP and to stimulate increased black enrollment, see

supra p. 7-8. The panel dismissed this remedial purpose

based upon its reading of Wygant, 38 F.3d at 159, 21a-22a.

But in Wygant the "role model theory" was advanced by a

school board which denied any past discrimination as a

justification for racial preferences in making layoffs. Here,

the underlying remedial purpose is indisputable, and UMCP

seeks merely to take advantage of the "role model"

phenomenon to assist in remedying the lingering effects of

prior discrimination in admitting and treating African

Americans at the school. Nothing in Wygant rules out

otherwise permissible affirmative action merely-because it is

23

designed to take advantage of "role modeling" opportunities

to combat prejudice and stereotyping.

Finally, applying a presumption of invalidity despite

the University’s remedial purpose led the panel to question

UMCP’s flexible admissions process in assessing whether

there was still underrepresentation of African Americans at

the school that could be ameliorated by the Banneker

Program. Although acknowledging that there are no

minimum criteria for admission, 38 F.3d at 157 n.5, 16a n.5,

the panel held that "the district court should have

determined what the effective minimum criteria for admission

were by determining the lowest GPA and SAT scores

achieved by admittees to the University that year," id

(emphasis added), and then calculated the pool of potential

African-American applicants who met those "effective

minimum criteria." This approach ignores the fact that the

lowest GPA and SAT scores of a particular entering

freshman class are an artifact of the overall characteristics of

the applicant pool in that year, and not a reflection of the

"unspoken" but "effective" real minimum criteria for

admission, and the fact that UMCP officials may at any time

accept another candidate with a lower average or score than

anyone already granted admission if they conclude that the

candidate has the ability, overall, to succeed at the school.21

If the ruling below is permitted to stand, neither

college and university staffs, states, federal courts nor the

United States Department of Education will have anyway of

knowing whether other-race scholarships such as those

awarded under the Banneker program at UMCP are to be

2lEven if the panel were correct, that could not support its holding

that Podberesky was entitled to judgment as a matter of law.

Underrepresentation was only one of the continuing effects of past

discrimination identified by the District Court to which the Banneker

Program was addressed.

24

viewed as constitutional remedies or constitutional violations,

even in states with long histories of operating racially dual

systems of higher education. The decision of the Fourth

Circuit in this case, therefore, presents questions of

overwhelming national importance that demand resolution

by this Court. The Court should issue the writ for this

purpose.

II

The Decision Below Rests Upon A Wholly

Erroneous View of Statistical Proof in

Discrimination Cases that Is Contrary to the

Explicit Teaching of this Court in Bazemore v.

Friday, 478 U.S. 385 (1986), a Ruling in

Which This Court Reversed the Same Court

of Appeals for the Same Error

In Bazemore v. Friday, 751 F.2d 662, 671-72 (4th Cir.

1984), a panel of the Fourth Circuit reviewed the district

court s judgment in a suit charging discrimination in

compensation against African-American employees of the

North Carolina Agricultural Extension Service. The

plaintiffs’ expert witness had prepared regression analyses

which, he testified, indicated that race was a factor

accounting for then-current salary disparities between white

and black county agents. The defendants’ expert witness

also prepared regression analyses using the same variables

and interpreted the results differently from the plaintiffs’

witness. The Court of Appeals affirmed the district court’s

decision to reject the testimony of plaintiffs’ expert about the

multiple regression findings in its entirety "because the

plaintiffs’ expert had not included a number of variable

factors the court considered relevant," id. at 672.

This Court reversed, Bazemore v. Friday, 478 U.S.

385, 387, 400-01 (1986). It held that the inclusion or non-

inclusion from a statistical regression equation of additional

25

factors which might have explanatory value goes only to the

probative weight of the evidence, but that it was error to

exclude such evidence from consideration entirely because

the fact-finder hypothesized that there might be alternative

justifications for the observed disparities. The Court

suggested that defendants in such cases should not merely

criticize the plaintiffs’ analyses but should come forward with

their own regression tables to rebut whatever showing is

made by the plaintiffs.

The panel below made the same error as in the

earlier case. The parties to this lawsuit offered different

interpretations of statistical data in several categories as

appropriate indicators of the pool of qualified potential

applicants to UMCP, in light of the fact that the University

did not have rigid eligibility criteria (see supra note 13). The

district court carefully reviewed the evidence presented by

the parties and their contentions, ultimately rejecting some

arguments made by both sides but determining that at least

as late as 1991-92, black students were underrepresented at

UMCP in comparison to appropriate "pool" measures. See

838 F. Supp. at 1087-89, 63a-69a. The court below, however,

held that the district court erred by not including in its

analysis a number of other variables that had not been

quantified in any evidentiary presentation by respondent but

which the panel thought might have explanatory power. 38

F.3d at 159-60, 21a-25a. "[T]he reference pool must factor

out. to the extent practicable, all nontrivial, non-race-based

disparities in order to permit an inference that such, if any,

racial considerations contributed to the remaining disparity.

This the district court simply has not done." Id. at 160

24a “

“ Compare the language in Bazemorc, 751 F.2d at 672: "An

appropriate regression analysis of salary should therefore include all

measurable variables thought to have an effect on salary level."

26

The panel thus made the same error as in

B a ze m o re this Court should issue the writ to correct it.

Ill

Since the Court Below Concluded that There

Were Genuine Disputes about Facts Material

to the Cross-Motions for Summary

Judgment, It Acted Contrary to FED. R. Civ.

P. 56(c) and the Decisions of this Court in

Directing the THal Judge to Enter Summary

Judgment for the Plaintiff on Remand

The responsibility of the court below, in passing upon

the parties’ appeals from the District Court’s disposition of

“ In this portion of the opinion the panel also made a different and

significant error. It held that the reference pool of potential African-

American applicants to UMCP should have been reduced to reflect "that

percentage of otherwise eligible African-American high school graduates

who . . . voluntarily limited their applications to Maryland’s predomin

antly African-American institutions," id. at 159-60, 23a (footnote

omitted), adding that it

infer)red) that significant numbers of UMCP-eligible Maryland

African-Americans do choose to go to the [historically]

predominantly African-American Maryland schools, such as

Coppin State, Bowie State, and UM Eastern Shore, whether

their reasons are economic, academic, geographic, or cultural,

because the percentages of African-Americans in the student

bodies at those schools are so high,"

id. at 159-60 & n.13, 23a & n.13. Since one of the underlying issues in

these cases is whether currently existing racial patterns of enrollment

decisions are influenced by policies and practices traceable to the prior

dual system, see Fordice, 112 S. Ct. at 2737, the panel’s approach to this

question would have the effect of excluding highly probative evidence

from the statistical analysis. In short, the panel would preclude any

finding of continuing underrepresentation of blacks at UMCP so long as

their "college attendance [at the Slate’s historically black institutions] is

by choice and not by assignment" - the veiy position rejected by this

Court in Fordice, see 112 S. Ct. at 2236.

27

the cross-motions for summary judgment, was "to assess the

record under the standard set forth in Rule 56 of the

Federal Rules of Civil Procedure," Lujan v. National Wildlife

Federation, 497 U.S. 871, 883-84 (1990).

Rule 56(c) states that a party is entitled to summary

judgment in his favor "if the pleadings, depositions,

answers to interrogatories, and admissions on file, if

any, show that there is no genuine issue as to any

material fact and that the moving party is entitled to

a judgment as a matter of law."

Id at 884 (emphasis added). The panel applied this

standard when it determined that the District Court erred in

granting summary judgment for the defendant parties

because, ”[t]aking the facts [proffered] in the light most

favorable to Podberesky, the non-moving party, . . . [there

were] factual disputes in this case [that] are not

inconsequential and could have been resolved only at trial."

38 F.3d at 156, 157, 14a, 18a. However, the panel

completely ignored these asserted factual controversies when

it directed the District Court to enter summary judgment for

Podberesky on remand. This fundamental error warrants

review and correction by this Court to assure that the

summary judgment process in the federal courts functions

properly.24

In an early section (II) of its opinion, the panel

reviewed the four present effects of past discrimination

identified by the District Court. Two, it held, were

insufficient as a matter of law to justify continued race

conscious action. See supra p. 14.25 But as to the

^The Court has demonstrated its concern for these issues in recent

years. See, e.g., Lujan; Celotex Corp. v. Cairetl, 477 U.S. 317 (1986);

Anderson v. Liberty Lobby, 477 U.S. 242 (1986).

Neither of these points, we believe, warranted summary judgment

for Podberesky. In brief, the panel viewed the availability of Banneker

2 8

remaining "two effects that rely on statistical data," the panel

said, the "district court erred in its analysis of the under

representation evidence and the attrition evidence for a

fundamental reason . . . [a] district court may not resolve

conflicts in the evidence on summary judgment motions

. . . [as it did] here." 38 F.3d at 155, 13a. When it turned to

the denial of plaintiff’s cross-motion for summary judgment,

the panel focused on the same issues -- underrepresentation

and attrition. Id. at 157-58, 18a-19a. In this part of the

opinion, however (and despite the panel’s apparent

disclaimer26), the court simply ignored the implication of its

earlier recognition that there were factual disputes that

could be resolved only at trial: there was enough evidence

introduced in support o f the positions o f the defendant parties

to create triable issues and to prevent summary disposition?

scholarships to non-residents and to high-achieving students as being

divorced from properly remedial purposes; but, as we have previously

pointed out, UMCP excluded all African-Americans, resident and non

resident, high-achieving and not-so-high-achieving, for many years.

“ At the beginning of its discussion about the propriety of denying

Podbereskv’s cross-motion for summary judgment, the panel said, "[e]ven

if we assumed that the University had demonstrated that African-

Americans were underrepresented at the University and that the higher

attrition rate was related to past discrimination, we could not uphold the

Banneker Program [because i]t is not narrowly tailored . . . . " 38 F Jd at

157-58, 18a-19a (footnote omitted). But in the balance of its discussion,

the panel not only failed to make this assumption but instead sharply

criticized the District Court’s assessment of the evidence introduced by

the parties on these questions, see id. at 159-61, 19a-27a, and commented

that ’[i]t is difficult to determine whether the Banneker scholarship

program is narrowly tailored to remedy the present effects of

discrimination when the proof of present effects is so weak," id. at 158,

19a.

^The panel began this last section of its opinion with the comment

that "[i]n our first opinion in this case, we required that should no further

evidence be available upon remand, summary judgment for Podberesky

should be granted, id. at 161, 28a. Extensive additional evidence about

29

Instead, the panel ignored that factual record; it

characterized the State’s position on underrepresentation as

"resting] on . . . unsupported assumptions]," id at 160, 25a

and it opined, contrary to the declarations and affidavits of

both Maryland officials and numerous Presidents and

Chancellors of colleges and universities in the United States,

that ”[t]he causes of the low retention rates submitted both

by Podberesky and the University and found by the district

court have little, if anything, to do with the Banneker

Program," id. at 161, 27a.

The standards of Fed . R. Civ . P. 56(c), like other

provisions of the Federal Rules, apply equally to plaintiffs

and defendants, see, e.g., Anderson v. City o f Bessemer City,

470 U.S. 564 (1985) (Rule 52); Pullman-Standard v. Swint,

456 U.S. 273 (1982) (same). The court below failed to

follow this bedrock principle in deciding this case, and its

error merits correction by this Court.28

racial discrimination in Maryland’s higher education system and its

continuing effects was put before the District Court upon that remand,

including, as indicated in the text, sufficient evidence to warrant summary

judgment for the defendant parties, or at a minimum a trial, rather than

the grant of summary judgment. Nevertheless, the panel suggested that

respondent was entitled to summary judgment in his favor pursuant to

the earlier remand instructions. The panel nowhere explained this

contradiction.

“ Indeed, this error is so clear and unambiguous that the Court may

wish to reverse summarily on this ground and remand the case to the

District Court with instructions to conduct a trial.

30

Conclusion

For the foregoing reasons, petitioners Monica

Greene, et al, respectfully pray that the Writ of Certiorari

be issued to review the judgment of the United States Court

of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit in this matter.29

Respectfully submitted,

W illia m J. M u r p h y

Jo h n J. C o n n o lly

M u r p h y & Sh a f f e r

100 Light Street, Suite 750

Baltimore, MD 21202

(410) 752-1564

Sa l l y P. Pa x t o n

Ja c o u e u n e R. D epew

F u l b r ig h t & Jaw o rski L.L.P.

801 Pennsylvania Avenue, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20004

(202) 662-0200

E la in e R . Jo n es

D ir e c t o r -Co u n s e l

T h e o d o r e M . Sh aw

No r m a n J. C h a c h k in

NAACP L e g a l D e f e n s e &

E d u c a t io n a l F u n d , In c .

99 Hudson Street, 16th fl.

New York, NY 10013

(212) 219-1900

•Ja n e l l M . By r d

NAACP L e g a l D e fe n s e &

E d u c a t io n a l F u n d , In c .

1275 K Street, N.W., Suite 301

Washington, D.C. 20005

(202) 682-1300

* Counsel o f Record

Attorneys for Petitioners

^Greene Petitioners note that the second Question Presented in the

separate Petition of William E. Kirwan, et aL was presented to, but not

decided by, either court below. However, the judgment below implicitly

decides it adversely to the State of Maryland, in directing the entry of

summary judgment in favor of plaintiff Podberesky. That question will

be moot if this Court reverses the Fourth Circuit on the other grounds

ui^ged in both petitions. If the Court does not, it may wish to vacate and

remand so that the question may be explicitly considered by the District

Court and the Court of Appeals.