Cooper v. Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the US Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1983

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Cooper v. Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the US Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit, 1983. 51fe8642-ae9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/7efa89a0-6c07-4fb7-a0a4-796642360973/cooper-v-federal-reserve-bank-of-richmond-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari-to-the-us-court-of-appeals-for-the-fourth-circuit. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

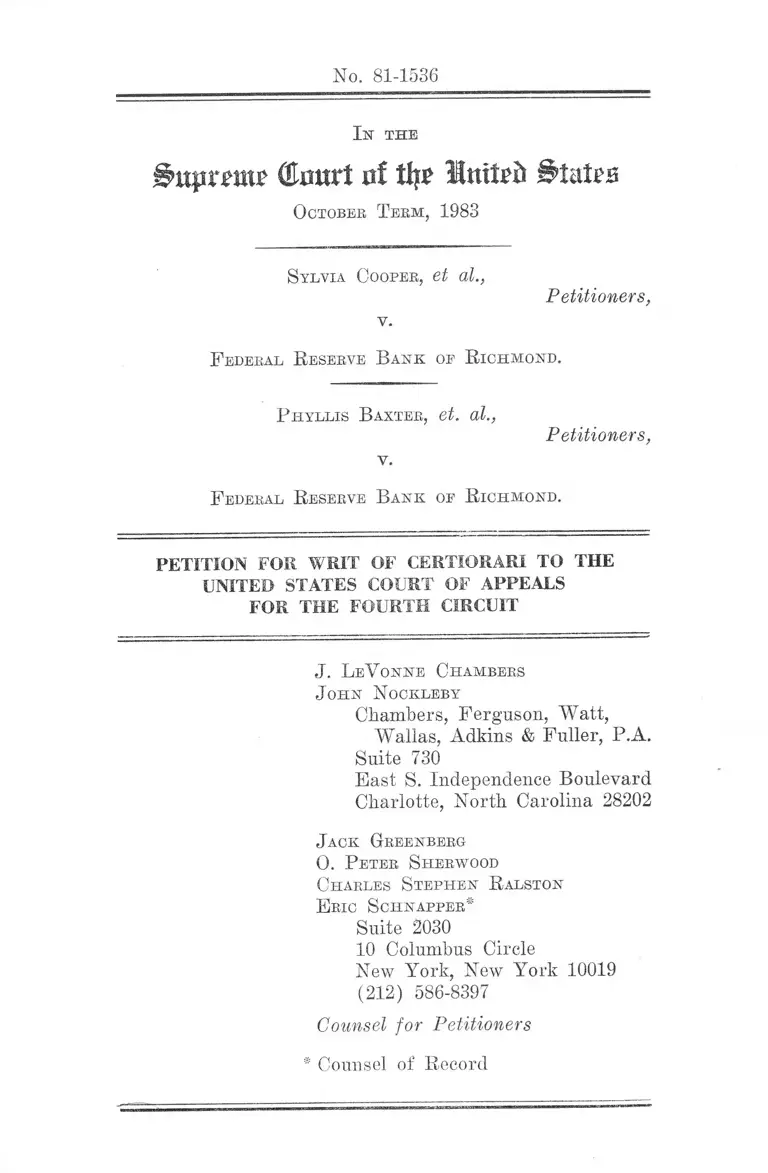

No. 81-1536

IS THE

ji>uprm£ ©Hurt n i X\\t United States

O ctober T e em , 1983

S ylvia C ooper, et al.,

Petitioners,

v.

F ederal R eserve B a n k op R ic h m o n d .

P h y l lis B axter , et. al.,

v.

Petitioners,

F ederal R eserve B a n k op R ic h m o n d .

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

J . L eV onne C h am bers

J o h n N ockleby

Chambers, Ferguson, Watt,

Wallas, Adkins & Fuller, P.A.

Suite 730

East S. Independence Boulevard

Charlotte, North Carolina 28202

J ack G reenberg

0 . P eter S herwood

C harles S te p h e n R alston

E ric S c h n a ppe r*

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

New Toi’k, New York 10019

(212) 586-8397

Counsel for Petitioners

* Counsel of Record

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

1. Did the Court of Appeals err

in holding that a prior finding that any

pattern or practice of employment discrimi

nation was not "pervasive" precludes,

as a matter of res judicata, all employees

from litigating any individual claims

of discrimination?

2. Did the Court of Appeals violate

the principles of Pullman-Standard Co. v.

Swint, 456 U.S. 273 (1982) when it held that

the trial court's finding of intentional

discrimination was "a statement of ultimate

fact ... not a finding of fact reviewable

under the 'clearly erroneous' rule"?

3. Does Rule 52, F.R.C.P., authorize

the appellate courts to reconsider de novo

or give little weight to the decision of a

district court merely because the lower

court based its findings of fact on pro-

l

posed findings submitted by counsel at the

direction of the court?

The parties to this proceeding are

Sylvia Cooper, Constance Russell, Helen

Moore, Elmore Hannah, Jr., Phyllis Baxter,

Brenda Gilliam, Glenda Knotts, Alfred

Harrison, Sherri McCorkle, the Federal

Reserve Bank of Richmond, and a class

PARTIES

composed of all black persons who were

employed at the Charlotte facilities of

the Bank at any time between January 3,

1974, and September 8, 1980, who were

subjected to employment discrimination on

the basis of race. The Equal Employment

Opportunity Commission was a party to the

Cooper action in the courts below.

i i i

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Questions Presented ......... i

Parties .................................. ii

Table of Authorities .................... vi

Opinions Below .......................... 2

Jurisdiction ............................ 3

Rule Involved ............... 3

Statement of the Case ................... 4

Reasons for Granting the Writ ........... 12

I. Certiorari Should Be Granted to

Resolve A Conflict Among the

Courts of Appeals Regarding

Whether A Finding of No Pervasive

Pattern and Practice of Discrimi

nation Bars All Individual

Claims of Discrimination Because of Res Judicata ................ 12

II. Certiorari Should Be Granted to

Resolve A Conflict Among the

Courts of Appeals Regarding the

Use of Proposed Findings Prepared

by Counsel for a Party ......... 19

III. The Decision of the Court of

Appeals Is Inconsistent With

Pullman-Standard Co. v. Swint,

456 U.S. 273 (1982) ............. 38

- iv

Page

Conclusion .............................. 41

APPENDIX

Opinion of the Court of Appeals,

January 11, 1983 ................ 2a

Order of the Court of Appeals

Denying Rehearing, April 6, 1983 .. 186a

Order of the Court of Appeals

Denying Rehearing En Banc,

April 6, 1 983 .................... 188a

District Court Memorandum of Decision,

October 30, 1980 ................. 191a

District Court Findings of Fact and

Conclusions of Law, May 29, 1981 .. 197a

District Court Order, May 29, 1981 .. 286a

District Court Order, February 26,

1982 ............................... 290a

v

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases: Page

Amstar Corporation v. Domino's Pizza, Inc.,

615 F. 2d 552 (5th Cir. 1980) ......... 23, 29

Askew v. United States, 680 F.2d 1206

(8th Cir. 1982) . ...................... 23, 29

Bradley v. Maryland Casualty Co.,

382 F. 2d 415 (8th Cir. 1967) ......... 23, 24

Bogard v. Cook, 586 F.2d 399

(5th Cir. 1978) ...................... 13

Chicopee Manufacturing Corp. v. Kendall

Co., 288 F.2d 719 (4th Cir. 1961) .... 26

Connecticut v. Teal, U.S. ,

73 L.Ed. 2d 130 (1982) ............... 16

Continuous Curve Contact Lenses v. Rynco

Scientific Corp., 680 F.2d 605 (9th

Cir. 1982) ........................... 25, 30

Cuthbertson v„ Biggers Brothers, Inc.,

(4th Cir.) (slip opinion, March 9,

1983) .................................. 28

Dickerson v. United States Steel, 582

F. 2d 827 (3d Cir. 1978) ..... ......... 12

Eastland v. T.V.A., F.2d

(11th Cir. 1983) ........ ............. 14-15

Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co.,

424 U.S. 747 (1976) ................... 16, 17

Furnco Construction Co. v. Waters,

438 U.S. 567 (1978) ................... 15

- vi -

Halkin v. Helms, 598 F.2d 1

(D.C. Cir. 1978) ..................... 20

Hill & Range Songs, Inc. v. Fred Rose

Music, Inc., 570 F.2d 554

(6th Cir. 1978) ................. ..... 21

Holsey v. Armour, 683 F.2d 864 '

(4th Cir. 1982) .................... . . 27

In Re Las Colinas, Inc.,426 F. 2d 1005 (1st Cir. 1970) ........ 25, 2829

International Controls Corp. v. Vesco,

490 F. 2d 1334 (2d Cir. 1974) ......... 25

Kelson v. United States, 503 F.2d 1291

(10th Cir. 1974) ..................... 23

Marshall v. Kirkland, 602 F.2d 1282

(8th Cir. 1979) ...................... 14

Mississippi Valley Barge Line Co. v.

Cooper Terminals, 217 F.2d 321

(7th Cir. 1954) ...................... 22

O'Leary v. Liggett Drug Co.,

150 F. 2d 656 (6th Cir. 1946).......... 21

Pullman-Standard Co. v. Swint, 456 U.S.

273 (1982) ........................... 7, 38,39, 40

Ramey Construction Co. v. Apache Tribe,

616 F. 2d 464 (10th Cir. 1980) ........ 25, 28

Roberts v. Ross, 344 F.2d 747

(3d Cir. 1965) ....................... 23, 24,

Saco-Lowell Shops v. Reynolds,141 F. 2d 587 (4th Cir. 1944) ......... 19, 26

- vii -

Page

Schilling v. Schwitzer-Cummins Co.,

142 F. 2d 82 (D.C.Cir. 1944) ........... 21

Scheller-Globe Corp. v. Milsco Mfg. Co.,

636 F. 2d 177 (7th Cir. 1980) ......... 22

Schlensky v. Dorsey, 574 F.2d 131

(3d Cir. 1978) ....................... 23

Schwerman Trucking Co. v. Gartland

Steamship Co., 496 F.2d 466

(8th Cir. 1974) ...................... 22

The Severance, 152 F.2d 916

(4th Cir. 1945) ..... ................. 26

Teamsters v. United States, 431 U.S.

324 (1977) ........................... 16, 1 7

United States v. Crescent Amusement Co.,

323 U.S. 173 (1945) ............. ..... 37

United States v. El Paso Natural Gas

Co. , 376 U.S. 651 (1964) ............. 37

White v. Carolina Paperboard Corp.,

564 F.2d 1073 (4th Cir. 1977) ......... 27

Statutes;

28 U.S.C. § 1254(1) ..................... 3

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5 ..................... 5

- viii -

Page

Rules:

Rule 23(a), Federal Rules of

Civil Procedure .................. .___ 17, 18

Rule 52(a), Federal Rules of Civil

Procedure ........................ 25, 38

Rule 19.4, Supreme Court Rules ...... ___ 2

IX

UNITED STATES SUPREME COURT

October Term, 1983

No. 81-1536

SYLVIA COOPER, et al.,

Petitioners

v.

FEDERAL RESERVE BANK OF RICHMOND

PHYLLIS BAXTER, et al.,

Petitioners,

v.

FEDERAL RESERVE BANK OF RICHMOND,

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI

TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

Petitioners Sylvia Cooper, et al., and

Phyllis Baxter, et al., respectfully pray

that a Writ of Certiorari issue to review

the judgment and opinion of the United

States Court of Appeals for the Fourth

2

Circuit entered in this proceeding on

January 11, 1983. Civil actions commenced

separately by petitioners Cooper and Baxter

were consolidated in the court of appeals;

a joint petition is being filed pursuant

to Rule 19.4 of this Court.

OPINIONS BELOW

The decision of the court of appeals

is reported at 698 F.2d 633 , and is set

out at pp. 2a- 185a of the Appendix. The

order denying rehearing, which is not yet

reported, is set out at p. 186a. The

district court's Memorandum Decision of

October 30, 1980, is not reported, and

is set out at pp. 191a-96a. The district

court's Findings of Fact and Conclusions

of Law, which is not reported is set out

at pp. 197a-285a. The district court orders

of May 29, 1981, and February 26, 1982,

which are not reported, are set forth at pp.

286a-88a and 290a-97a respectively.

JURISDICTION

The judgment of the Court of Appeals

was entered on January 11, 1983. A timely

Petition for Rehearing was filed, which was

denied on April 6, 1983 by an equally

divided court. (App. p. 186a) This Court

granted an extension of time in which to

file the Petition for Writ of Certiorari

until August 4, 1983. Jurisdiction of this

Court is invoked under 28 U.S.C. § 1254(1).

RULE INVOLVED

Rule 52(a), Federal Rules of Civil

Procedure, provides:

In all actions tried upon the facts

without a jury or with an advisory

jury, the court shall find the facts

specially and state separately its

conclusions of law thereon, and

judgment shall be entered pursuant

to Rule 58; and in granting or refus

ing interlocutory injunctions the court

4

shall similarly set forth the find

ings of fact and conclusions of law

which constitute the grounds of its

action. Requests for findings are not

necessary for purposes of review.

Findings of fact shall not be set aside

unless clearly erroneous, and due

regard shall be given to the opportun

ity of the trial court to judge of the

credibility of the witnesses. The

findings of a master, to the extent

that the court adopts them, shall be

considered as the findings of the

court. If an opinion or memorandum of

decision is filed, it will be suffi

cient if the findings of fact and

conclusions of law appear therein.

Findings of fact and conclusions of law

are unnecessary on decisions of motions

under Rules 12 or 56 or any other

motion except as provided in Rule

41(b).

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

This petition involves two related

proceedings which were consolidated in the

court of appeals for argument and decision.

Cooper Plaintiffs: On March 22, 1977

the EEOC brought suit against the Federal

Reserve Bank of Richmond alleging that the

Bank had discriminated against black employ

ees in making promotions at its Charlotte,

5

North Carolina facilities, and that it had

discriminated in particular against Sylvia

Cooper because of her race, first by refus

ing to promote her to a supervisory position

and then by discharging her. Jurisdiction

was asserted under 42 U.S.C. 2000e-5. On

September 21, 1977, Cooper and three other

present or former Bank employees (the

"Cooper plaintiffs") were permitted to

intervene as plaintiffs. On April 28, 1978,

the district court certified a plaintiff

class consisting of blacks who had been

employed at the Bank's Charlotte branch

since January 3, 1974, and had been dis-

crimminated against on the basis of race.

The case was tried without a jury in

September, 1980. On October 30, 1980, the

district court issued a Memorandum of

Decision which held that the Bank had

discriminated against Cooper and another

6

intervenor, but concluding that no such

discrimination had been shown regarding

the other two intervenors. The trial court

also concluded that the Bank had engaged in

a pattern and practice of discrimination

in denying promotions to black employees

in pay grades 4 and 5.

The district court directed counsel

for the plaintiffs to propose more detailed

"findings of fact and conclusions of law

consistent with [its] findings." 194a.

The plaintiff submitted the requested pro

posed findings, and the defendant responded

with comments and objections of its own. On

May 29, 1981, the district court issued

proposed findings substantially similar to

those urged by plaintiff. 197a-285a.

On appeal the Fourth Circuit held that

the finding of discrimination contained

in the district court's October 30, 1980

Memorandum was "a statement of ultimate

7

fact ... not ... reviewable under the

'clearly erroneous' rule." 15a. The

court of appeals ruled that the more

detailed findings issued by the district

court were to be subject to a special

"careful scrutiny" (23a) because based

on findings proposed by counsel, a practice

the appellate court expressly disapproved.

16a. The court of appeals then undertook

an exhaustive 25,000 word re-examination

of the evidence considered by the trial

judge, and reversed each of his findings of

discrimination. Petitioners sought rehearing

en banc in the Fourth Circuit, urging inter

alia that the panel's decision exceeded

the bounds of appellate review permitted

by Rule 52(a), Federal Rules of Civil

Procedure, and by this Court's decision in

Pullman-Standard Co. v. Swint, 456 U.S.

273 (1982). Rehearing en banc was denied by

an equally divided court, judges Winter,

8

Phillips, Murnaghan and Sprouse all having

voted to reconsider the panel decision.

Baxter Plaintiffs

At the trial of the Cooger class

action the plaintiffs presented testimony

from a number of class member witnesses,

including Phyllis Baxter, Brenda Gilliam,

Glenda Knott and Sherri McCorkle (the

"Baxter plaintiffs"), all of whom held

job grades 6 or above. The Bank success

fully argued that the district court should

receive the class members' testimony

only as it related to the pattern and

practice allegation, and that the court

should not pass on the merits of these

witnesses' individual claims. The trial

court ruled that the individual claims

of the Baxter plaintiffs would not be heard,

and that the Court would not consider their

testimony except insofar as it tended to

9

establish the existence of a class-wide

pattern and practice of discrimination.

After trial, the district court issued

a Memorandum of Decision in the Cooper lit

igation holding that the class had demon

strated a discriminatory pattern of promo

tions out of grades 4 and 5. However, with

respect to promotions out of grades 6 and

above, the Court held:

There does not appear to be a

pattern and practice pervasive

enough for the court to order

relief. 194a. (emphasis added)

The trial court did not, however, rule that

there had been no discrimination in grades 6

and above.

Shortly after receiving the trial

court's Memorandum in Cooper, the Baxter

plaintiffs sought to intervene in that

action. Again, as it had done during

trial, defendant's counsel opposed hearing

the individual claims of the Baxter plain-

10-

tiffs in the context of the Cooper action.

In its memorandum in opposition to the

motion to intervene, the defendant assured

the district court that denying interven

tion would not preclude a separate subse

quent action by the Baxter plaintiffs:

"There is no way there will be any

prejudice to applicants in denying

their motion [to intervene], since

they can pursue any individual

claims they have in separate pro

ceedings." (Defendant's Response

to Motion to Intervene, p. 4.)

The district court denied the Baxter plain

tiffs' Motion to Intervene in EEOC v.Cooper

on the very basis advanced by the defend

ants, explaining:

I see no reason why, if any of the

would be intervenors are actively

interested in pursuing their

claims, they cannot file a §1981

suit next week, or why they could

not file a claim with EEOC next

week ___ All motions for leave

to intervene are thus denied

without prejudice to any underly

ing rights the intervenors may

have. 288a.

The Baxter plaintiffs promptly filed a

separate proceeding, styled Baxter, et al.

v. Federal Reserve Bank. Their Complaint

alleged that each had been discriminated

against in certain respects on an individual

basis. The Baxter plaintiffs did not claim

that the defendant had engaged in a pattern

of discrimination against a class of black

employees. The defendant moved to dismiss

that new action, contending that the Cooper

decision barred it as a matter of res

judicata. The district court denied the

motion to dismiss, but certified the ques

tion to the court of appeals (291a), which

reversed. 172a-85a. Upon consideration of

the Baxter plaintiffs' Petition for Rehear

ing and Suggestion for Rehearing En Banc,

the Panel's decision was upheld by an

equally divided (4-4) Court. 188a.

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE WRIT

I. Certiorari Should Be Granted To Resolve

^LQnq the Courts of Appeals

Regarding Whether A Finding of No Pervasive

Pattern and Practice of Discrimination Bars ATI Individual Claims of DiscrimTnat ion

BecFuse-of Res Judicata

The Fourth Circuit's decision that the

rejection of a class-wide pattern and prac

tice discrimination claim bars all indivi

dual discrimination claims is squarely in

conflict with what has hitherto been the

uniform view of the other courts of appeals

which have considered this issue. In

Dickerson v. United States Steel, 582 F.2d

827 (3d Cir. 1978), the Third Circuit

rejected the identical argument made by the

Bank in this case:

The Company contends that, as a

threshold matter, the district court's

dismissal of a class-wide claim bars

individual lawsuits under that claim by

class member witnesses .... The class

claims were not examined as a mere

aggregation of individual claims, as

the Company's argument suggests.

Rather, the district court looked to

13

statistical evidence offered to support

the existence of a practice or pattern

of discrimination .... The district

court's finding of an absence of

class-wide discrimination is not

necessarily inconsistent with a claim

that discrete, isolated instances

of discrimination occurred, for which

the statis tical evidence of a pattern

of discrimination may have been

lacking; there may have been suffi

cient evidence to establish a prima

facie case of discrimination directed

against specific employees. There

fore, the court's decision.as_to

class-wide claims of discrimination

does not, as a matter of res judi-

cata, bar class members from assert-

ing individual claims of personal

discrimination.

582 F.2d at 830-31.

In Bogard v. Cook, 586 F.2d 399 (5th

Cir. 1978 ), the Fifth Circuit held that

an individual prison inmate who had testi

fied during an earlier class action regard

ing prison conditions could still litigate

the defendant's particular treatment of

him, and was not barred by that earlier

prison—wide class action. The court of

appeals emphasized that the prior litiga-

14

tion had not specifically adjudicated

Bogard's personal claim, and expressed

doubts as to whether the district court

would have been willing to resolve such

individual questions in the context of

the class litigation. 586 F.2d at 409. In

Marshall v. Kirkland, 602 F.2d 1282 (8th

Cir. 1979), the plaintiffs in a class

action had sought individual relief for

only certain members of the class. The

Eighth Circuit held that relief for other

individuals could not be obtained on

appeal, but stressed

Our determination is "without prej

udice" to the right of the other

members of this class ... to initiate

a new action if they see fit.......

[C]lass members whose claims were

not actually litigated should not

be estopped by res judicata.

602 F.2d at 1282.

Recently, the Eleventh Circuit reached

a result inherently inconsistent with

the Fourth Circuit's holding. In Eastland

15

v. T.V.A., F. 2d (11th Cir. 1983),

the court affirmed the district court's

determination that there was no cj.ass

discrimination, but reversed its finding

of no discrimination against certain class

members. That decision conflicts squarely

with the Fourth Circuit's holding that a

finding of no class discrimination disposes

of all individual claims as well.

The decision of the Fourth Circuit

conflicts as well with the decisions of

this Court. Furnco Construction Co._

v. Waters, 438 U.S. 567 (1978) makes clear

that the absence of a general policy of

discrimination "cannot immunize an employer

for liability for specific acts of dis

crimination." 438 U.S. at 579. It empha

sized that the existence of a racially

balanced workforce, while relevant to

a claim that a particular employment action

was racially motivated, could not "conclu

sively demonstrate" the absence of such a

motive. 438 U.S. at 580 (emphasis added).

See also Connecticut v. Teal, ___U.S.

____, 73 L.Ed. 2d 130, 142 (1982). Con

versely, the decisions of this Court in

Teamsters v. United States, 431 U.S. 324

(1977), and Franks v. Bowman Transportation

Co♦, 424 U.S. 747 (1976), establish that

a finding of class-wide discrimination does

not constitute a final adjudication of the

claims of individual class members. In such

a case, the employer, while bound by the

finding of a pattern of discrimination,

still is entitled to an opportunity to prove

that particular employment decisions were

made free of discriminatory intent.

If a finding regarding the existence

of a class-wide pattern and practice of

discrimination is conclusive of all individ

ual claims of class members, individual

class members would have no choice but to

intervene e_n masse prior to trial in order

to protect those individual claims. Were

that to occur, Rule 23 class actions would

become an irresistible invitation for the

joinder of claims which, by definition,

are "so numerous that joinder ... is

impracticable." Rule 23(a), Federal Rules

of Civil Procedure. Such a rule would

be equally burdensome on defendants, which

would be required in response to proof of

a class-wide pattern of discrimination

to offer individualized defenses to the

potential claims of each and every class

member. The district courts would no

longer be able to use the bifurcated trial

procedure which was expressly sanctioned by

Teamsters and Franks and which the lower

court have found eminently practical and

expeditious; individual and class claims

would have to be tried together.

18

This is not a case in which the indi

vidual claims of the Baxter plaintiffs

either were or even could have been adju

dicated in the class action litigation.

The district judge did not find there had

never been any discrimination in any promo

tions above pay grade 6, but only that there

was not proof that such discrimination was

sufficiently "pervasive" to warrant a

class-wide remedy. 194a. No objection is

made that the Baxter plaintiffs failed to

seek resolution of their claims in the

Cooper litigation; on the contrary, they

tried to do precisely that. The decision of

the Fourth Circuit both required the Baxter

plaintiffs to pursue their claims in the

class litigation, and upheld a district

court order forbidding them from doing so.

Administered in this way Rule 23 would serve

as a snare for the diligent as well as the

unwary.

19

11 . Certiorari Should Be Granted To

Resolve_A_Cqnflict Among the Courts of

Appeals Regarding the , U.se_of_Pro£osed

Findings Prepared By Counsel for the Parties

Rule 52(a) requires the United States

District Courts, in all cases tried without

a jury, to "find the facts specially and

state separately their conclusions of law

thereon." Since the original promulgation

of this Rule, there has been a widespread

practice among district judges of asking for

and relying on proposed findings of fact and1/conclusions of law drafted by counsel. In

some instances trial judges solicit such

findings prior to deciding the case; in

other instances they are sought only after

the judge has indicated how he or she in

ends to rule on the controversy at issue.

1/ See, e . g . , Saco-Lowell Shops v.

Reynolds^ 141 F.2d 587, 589 (4th Cir.

T944j“

20

The appellate courts are increasingly-

divided over whether the use or adoption of

such proposed findings is always or ever

permissible, and those circuits which

disapprove this practice are in disagreement

as to how such findings should be dealt with

on appeal. These divisions are especially

sharp over the district court practice, fol

lowed in this case, of asking the prevailing

party to draft proposed findings consistent

with the trial judge's announced decision in

its favor.

The procedure utilized by the trial

judge in this case is expressly sanctioned

in the Sixth, Seventh and District of

Columbia Circuits. The court of appeals

for the District of Columbia most recently

rejected an attack on this practice in

Halkin v. Helms, 598 F.2d 1, 8 (D.C.Cir.

21

1978). That circuit court defended the

practice at length in Schilling v. Schwitz-

er-Cummins Co., 142 F.2d 82 ( D . C . Cir.

1944 ) :

Whatever may be the most commendable

method of preparing findings --

whether by a judge alone, or with

the assistance of his ... law clerk

... or from a draft submitted by

counsel -- may well depend upon

the case, the judge, and facilities

available to him. If inadequate

findings result from improper reliance

upon drafts prepared by counsel — or

from any other case — it is the

result and not the source that is

objectionable. 142 F. 2d at 83 (foot

notes omitted)

In Hill & Range Songs, Inc, v. Fred Rose

Music, Inc., 570 F.2d 554 (6th Cir. 1978),

the Sixth Circuit noted that it was "not

unusual" for a court "to adopt verbatim"

proposed findings of fact and conclusions

of law, and held that so long as those

findings and conclusions are supported

by the record "it makes no real difference

which counsel submitted them." 580 F. 2d

at 558. See also O'Leary v. Liggett Drug

22

Co. , 150 F. 2d 656 , 667 (6th Cir. 1946 )

("findings of fact, prepared and submitted

by the successful attorneys, [which]

have been adopted by the trial court

... are entitled to the same respect as if

the judge, himself, had drafted them").

The Seventh Circuit upheld the practice in

Schwerman Trucking Co. v. Gartland Steam

ship Co . , 496 F.2d 466, 475 (8th Cir.

1974), explaining:

By having the prevailing party submit

proposed findings of fact and conclu

sions of law, the judge followed

a practical and wise custom in which

the prevailing party has "an obliga

tion to a busy court to assist it

in performance of its duty" under

Rule 52(a).

See also Scheller-Globe Corp. v. Milsco

Mfg. Co., 636 F.2d 177, 178 (7th Cir. 1980)

("This circuit ... leaves the matter within

the trial court's discretion and recognizes

that the procedure can be of considerable

assistance to a trial court ...."); Missi-

23

ssippi Valley Barge Line Co. v._Cooper

Terminal Co. , 217 F.2d 321, 323 (7th Cir.

1954) ("It was perfectly proper to ask

counsel for the successful party to

perform the task of drafting the findings

But this use of findings prepared by

the prevailing party, a procedure described

by the Seventh Circuit as of "considerable

assistance" to the trial courts, has been

specifically disapproved, although in

2/ 3/varying degrees, by the Third, Fifth,

4/ 5/Eighth, and Tenth circuits. On the other

2/ Schlensky v. Dorsey, 574 F.2d 131,

148-49 (3d Cir. 1978); Roberts v. Ross, 344

F.2d 747, 751-53 (3d Cir. 1965).

3/ Amstar Corporation v. Domino's Pizza,

Inc. , 615 F. 2d 552, 258 (5th Cir. 1980).

£/ Askew v. United States, 680 F.2d 1206,

1207-08 (8th Cir. 1982); Bradley v. Mary

land Casualty Co. , 382 F.2d 415, 422-23

(8th Cir. 1967).

5/ Kelson v. United States, 503 F.2d 1291,

1294 (10th Cir. 1974).

24

hand, the

do approve

counsel if

6/ 7/Third and Eighth circuits

the use of findings drafted by

the trial court solicits and

considers such proposed findings from both

sides prior to its decision on the merits.

In Roberts v. Ross, 344 F.2d 747, 752 ( 3d

Cir. 1965), the Third Circuit noted:

In most cases it will appear that

many of the findings proposed by one

or the other of the parties are

fully supported by the evidence,

are directed to material matters and

may be adopted verbatim and it may

even be that in some cases the find

ings and conclusions proposed by a

party will be so carefully and objec

tively prepared that they may all

properly be adopted by the trial judge

without change.

But the verbatim adoption of proposed

findings, sanctioned in appropriate cases

by these two circuits, is "roundly con-

6/ Sc:h lensky v. Dorsey, 574 F .

148--49 ; Roberl: s v. Ross, 344 F .

752-53.

7/ Bradley v. Maryland Casualty Co.

F. 2d at 423.

382

25

demned" by the Second Circuit and approved

only in "highly technical" cases in the

9/ _1_0/First and Ninth Circuits. The most

recent Tenth Circuit opinion on this sub

ject states both that the verbatim adoption

of proposed findings "may be acceptable

under some circumstances" and that it "is

an abandonment of the duty imposed on trial

11/judges by Rule 52."

Consistent with this inter-circuit

conflict, the Fourth Circuit's position on

8/

8/ International Controls Corp. v. Vesco,

490 F. 2d 1334, 1341 n. 6 (2d Cir. 1974 ).

9/ In_

1009 (1st

adopting

should be

when the

technical

Re Las Colinas, Inc., 426 F.2d 1005,

("[T]he practice of

findings verbatim

extraordinary cases

is of a highly

expertise

Cir. 1970)

proposed

limited to

subject matter

nature requiring

which the court does not possess.")

10/ Continuous Curve Contact Lenses v.

Rynco Scientific Corp., 680 F.2d 605, 607

(9th Cir. 1982).

11/ Ramey Construction Co. v. Apache

Tribe, 616 F.2d 464, 466 (10th Cir. 1980)

26

the use of proposed findings has undergone

a complete reversal in recent years. Saco-

Lowell Shops v. Reynolds,. 141 F.2d 587, 589

(4th Cir. 1944), held that findings of fact

"are not weakened or discredited because

made by the trial judge in the form re

quested by counsel." In The Severance,

152 F.2d 916 (4th Cir. 1945), the trial

judge had requested the prevailing party to

draft proposed findings of fact and conclu

sions of law, and had adopted them "practi

cally in toto"; the court of appeals held

that " [t]his practice is not to be con

demned." 152 F.2d at 918. Chi copee

M a n u£ a^ t̂]j r iLng__C o r v_. a KL^C o . ,

288 F .2 d 719, 7 2 4-25 (4th Cir. 1961),

citing decisions in the Sixth and District

of Columbia circuits, noted there was

authority for "the adoption of such ...

proposed findings and conclusions as the

27

judge may find to be proper," and condemned

only the £x parte drafting of an opinion

by counsel for one of the parties. In

White v. Carolina Paperboard Corp., 564

F. 2d 1073 ( 4th Cir. 1977), the court of

appeals, although criticizing the content

of particular findings adopted from the

proposals of counsel, expressed no per se

disapproval of the use of such findings,

and merely concluded that" [o]n remand, we

suggest the district court prepare its own

opinion." 564 F.2d at 1082-83. (Emphasis

added) In July, 1982, the Fourth Circuit

"cautioned against" the adoption of find

ings solicited by the trial judge from the

prevailing party. Holsey v. Armour, 683

F. 2d 864, 866 (4th Cir. 1982). Not until

the decision below did that "caution"

evolve into "disapproval." 16a. Two months

after the decision in the , instant case,

the Fourth Circuit announced that it

28

had "previously condemned" this practice,

inexplicably citing The Severance, which,

as we noted above, had held precisely

the opposite. Cuthbertson v ._BjLĝ ejrjs

Brothers, Inc., (Slip opinion, March 9,

1983, pp. 8-9).

Those courts of appeals which do

disapprove the adoption of findings pre

pared by counsel are themselves in dis

agreement about how such findings should

be treated on appeal. No court regards

that practice as reversible error. In

12/at least some circumstances the First and

13/Tenth circuits will remand a case for

additional findings drafted by the trial

court itself. The Eighth circuit applies

the same "not clearly erroneous" rule

12/ In re Las Colinas, Inc. , 426 F . 2d

1005, 1010 (1st Cir. 1970).

1 3/ Ramey Construction Co. v. Apache

Tribe , 616 F . 2d 464, 467-69 (10th Cir.

1980).

29

regardless whether the findings appealed

from were drafted by counsel or the trial

1A/ . ,judge. Five circuits apply a special

standard of review when considering find

ings of fact adopted by the trial court

from proposals submitted by counsel. The

First Circuit conducts a "most searching

15/

examination for error" in such cases.

In the Third Circuit findings drafted by

counsel are "looked at ... more narrowly

11/and given less weight on review." The

Fifth Circuit will "take into account"

17/

the origin of such findings, while the

Ninth Circuit subjects them to "special

14/ Askew v. United States, 680 F.2d 1206,

1208 (8th Cir. 1982).

15/ In re Las Colinas, Inc., 426 F.2d

1005, 1010 (1st.Cir. 1970).

16/ Roberts v. Ross, 344 F.2d 747, 752 (3d

Cir. 1965).

17/ Amstar Corporation v. Domino's Pizza

Inc., 615 F. 2d 252, 258 (5th Cir. 1980).

30

scrutiny." The Fourth Circuit decision

in the instant case refers to several of

these apparently divergent standards with

out indicating which was being adopted.

23a-24a.

The standard of review actually ap

plied by the court of appeals in this case

was for all practical purposes a de novo

determination of the controversy. The

Fourth Circuit's 25,000 word opinion is

more than three times as long as the trial

judge's 38 page Findings of Fact and Con

clusions of Law. Virtually every finding

of fact made by the trial court on an issue

controverted by the defendants was decided

afresh, and in favor of defendants, on

appeal. The appellate court's discussion

of the minute details of the conflicting

11/

18/ Continuous Curve Contact Lenses, Inc.

v. Rynco Scientific Corporation, 680 F.2d

605, 607 (9th Cir. 1982).

31

evidence reflects, not an effort to

determine whether the lower court's find

ings were supported by substantial evi

dence, but an effort, in the words of

the Fourth Circuit, to determine what

result would "reflect the truth and the

right of the case." 24a.

The Fourth Circuit's treatment of ‘

petitioner Cooper's claim of discrimination

in promotion is typical of its approach.

There was conflicting testimony regarding

whether the promotion at issue in her

case was to the position of "utility

supervisor" or "reader sorter supervisor."

The trial court, expressly relying on the

demeanor of the witnesses, held that the

position was that of a utility supervisor.

220a, 266a-267a. The court of appeals,

after reviewing the same evidence, reached

the opposite conclusion. 155a-158a. The

district court found that Cooper was

qualified to supervise operation of the

32

reader-sorter machine. 266a. The court of

appeals found she was not. 161a. The

district court concluded that Cooper was

more qualified for the promotion than the

white employee who received it, 220a;

the court of appeals concluded that

she was not. 166a. The district court

held that the reasons given by defendant

for promoting a less experienced white

in place of Cooper were "pretextual,"

noting that the defendant had ignored its

own procedures in refusing to even consider

Cooper for the promotion, 265a-66a; the

court of appeals accepted without question

the defendant's account of the "qualifica

tions" for the job at issue. 163a.

The court of appeal's rejection of

the claim of class wide discrimination

demonstrates the dangers of such de novo

appellate review. Where, as here, there

is a complex trial involving technical

33

issues, and thousands of pages of exhibits

and documents, an appellate court which

attempts to decide afresh all the questions

at issue is virtually certain to misunder

stand or overlook relevant evidence. The

trial court in this case found there was a

pattern and practice of discrimination in

promoting employees from grades 4 and 5,

noting that blacks remained in these low

paid entry level positions longer than did

whites. Between 1966 and 1977, for exam

ple, white employees in grade 4 received

promotions after an average of 652 days,

while black employees waited an average of

982 days. 241a. The court of appeals

reversed on the assumption that these

differences were the result of black

employees being assigned to service

and cafeteria jobs rather than to clerical

positions. 105a-106a.

34

The court of appeals believed "it was

reasonable to expect" a substantial

portion of black hirees would be assigned

to service and cafeteria work. 105a.

But the district court found that over a

ten year period only 3 blacks expressing

no job preference had been assigned to

cleaning jobs. 243a. The court of appeals

felt it was "to be expected" that there

would be few promotion opportunities

in service and cafeteria jobs. 106a. But

the defendant only claimed that 13 of the

68 blacks in those departments had no

11/promotional opportunities. The court of

appeals rejected an analysis of promotion

rates because it did not include employees

who had resigned or been fired after

receiving a promotion, 57a-62a; but in

fact the exclusion of those employees

19/ Appendix, No. 81-1536, 4th Cir., p.

1117.

35

simply had no effect on the pattern of

20/disparities revealed by that analysis.

The Fourth Circuit's elaborate discus

sion of statistical methodology reflects a

similar approach. The defendants on

appeal criticized plaintiffs' expert for

using a "one-tail" rather than a "two-tail"

analysis of certain statistics. The Fourth

Circuit noted that "after all the technical

statistical jargon like 'one tail' and

'two-tail' ... were placed before the

judge, it was his job to resolve the

issues." 243a, n. 16. And then, having

noted that this was a question for the

trial court, the court of appeals proceeded

to hold that the use of a "one-tail" test

was improper. 83a-110a. Similarly, the

court of appeals insisted that the proper

20/ Petition for Rehearing and Suggestion

for Rehearing En Banc, No. 81-1536, 4th

Cir., pp. 9-12.

36

manner for calculating standard deviations

was the binomial distribution formula,

criticizing the trial judge for having

"accepted without question" a calculation

using the hypergeometric distribution

formula. 62a. In fact, however, the

trial judge had never questioned use of

the hypergeometric method because the

defendants had never objected to it at

trial, or raised the issue on appeal,

circumstances that would ordinarily

have precluded an appellate court from

even considering the issue.

As the very length and detail of

the Fourth Circuit opinion make clear,

the widespread differences regarding

the use of findings prepared by counsel

raises equally serious issues regarding the

roles of the appellate courts. The inde

pendent factfinding apparent on the face of

the Fourth Circuit's opinion would not

have occurred in the three circuits which

37

approve use of such findings, or in the

Eighth Circuit which applies to them the

usual "not clearly erroneous" rule.

This division among the lower courts

stems in part from this Court's past

ambivalent attitude towards findings

prepared by counsel. United States v.

Crescent Amusement Co., 323 U.S. 173

(1945), denounced the verbatim adoption of

proposed findings as "leav[ing] much to be

desired," and yet insisted "they are

nonetheless the findings of the District

Court." 323 U.S. at 185. United States v.

El Paso Natural Gas Co., 376 U.S. 651

(1964) complained that such findings were

"not the product of the workings of the

district judge's mind," and nonetheless

held that they were "formally his" and thus

"not to be rejected out of hand." 376 U.S.

at 656. The confusion and division among

and within the courts of appeals will

necessarily continue until this Court

38

resolves the conflicting implications of

Crescent Amusement and El Paso Natural Gas

by determining when if ever the adoption

of findings prepared by counsel is imper

missible, and by specifying what if any

thing the appellate courts are to do when

that occurs.

III. The Decision of the Court of Appeals

is Inconsistent with Pullman-Standard Co.

v. Swint, 456 U.S. 273 (1982).

The briefs in the instant case were

filed in the Court of Appeals in February

and March, 1982. In April of 1982,

this Court in Pullman-Standard Co. v .

Swint, 456 U.S. 273 (1982), rejected the

Fifth Circuit practice of refusing to

apply to findings of "ultimate fact" the

"not clearly erroneous" standard of Rule

52(a), Federal Rules of Civil Procedure.

In January, 1983, the court of ap

peals, apparently unaware of the decision

in Pullman-Standard, premised its reversal

39

of the district court's finding of dis

crimination on the very "ultimate fact"

doctrine that had been disapproved by this

Court only nine months earlier. The

linchpin of the Fourth Circuit's analysis

was its assertion that

the District Court['s] ... statement

that "the defendant [had] engaged in

a pattern and practice of discrimina

tion ..." [is] a statement of ultim

ate fact ... not a finding of fact

reviewable under the "clearly erro

neous" rule ... . (15a)(emphasis

added).

This holding is virtually identical to the

Fifth Circuit distinction, condemned in

' that "a finding of

discrimination ... is a finding of ultimate

fact." 456 U.S. at 286. The decision

below expressly relied on a pre-Pullman-

Standard Fifth Circuit opinion applying the

discredited distinction between ultimate

and subsidiary findings of fact 1 5a.

40

In our petition for rehearing below we

repeatedly referred to this Court's deci-

s i on in PulIman -Standard 2J./

f not ing

that "the panel's reference to 1' ultimate

fact[s] ' is the very concept on which the

Supreme Court reversed the Fifth Circuit

22/ The Fourth Circuit's refusal

to comply with the mandate of Pullman-Stan

dard is neither explicable nor excusable,

and warrants summary reversal by this

Court.

21 / Petition for Rehearing and Suggestion

for Rehearing En Banc, pp. 3, 10, 14, 21,

24, 26-28.

22/ Ibid, at 27.

41

For

ce rt ior,

j udgment

CONCLUSION

the above reasons a writ of

iri should issue to review the

and opinion of the Fourth Circuit.

Respectfully submitted,

J. LEVONNE CHAMBERS

JOHN NOCKLEBY

Chambers, Ferguson, Watt,

Wallas, Adkins & Fuller, P.A. Suite 730

East S. Independence

Boulevard

Charlotte, North Carolina 28202

J A C K G R E E N B E R G 0. PETER SHERWOOD

CHARLES STEPHEN RALSTON

ERIC SCHNAPPER

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019 (212) 586-8397

Counsel for Petitioners

Counsel of Record

MEILEN PRESS INC. — N. Y. C. S19