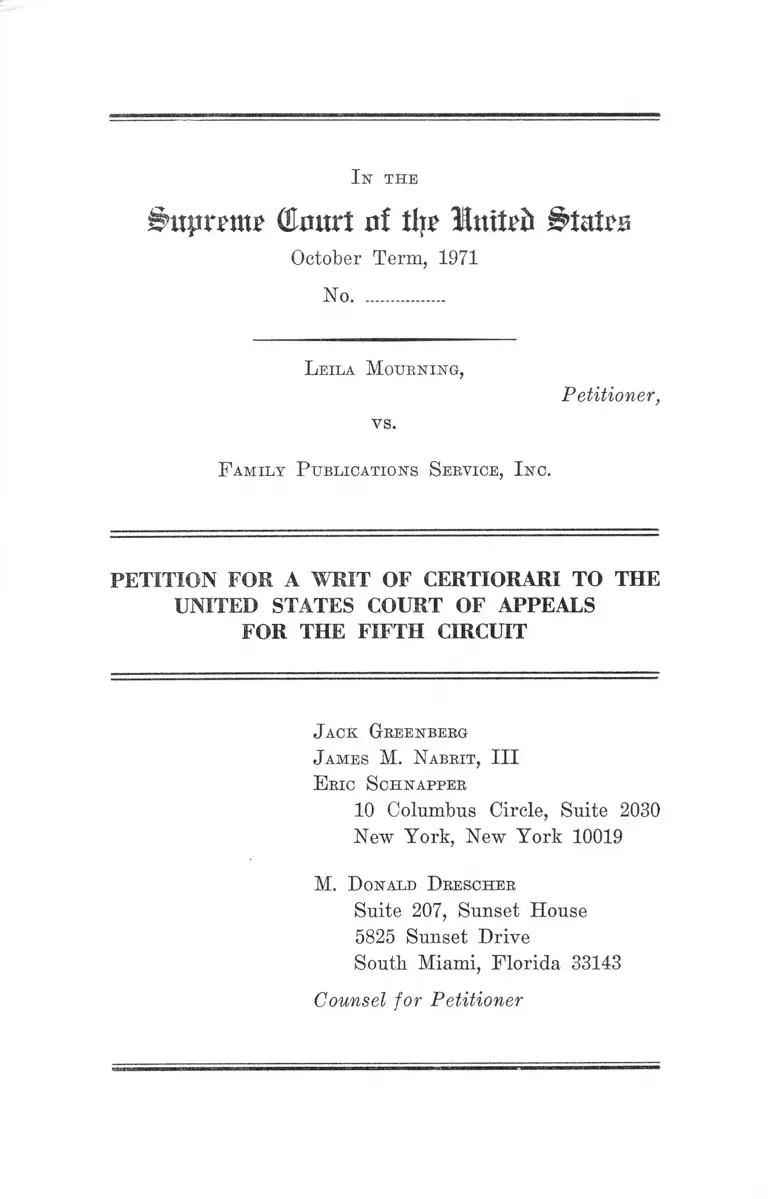

Mourning v. Family Publications Service, Inc. Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the US Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1971

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Mourning v. Family Publications Service, Inc. Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the US Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit, 1971. 6061ecde-be9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/7f13e753-89d4-49a9-9025-d30eaa386c6b/mourning-v-family-publications-service-inc-petition-for-a-writ-of-certiorari-to-the-us-court-of-appeals-for-the-fifth-circuit. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

I n the

^itprrmr (ta rt of tljr Imtrti i>tatro

October Term, 1971

No..................

L eila M ourning ,

vs.

Petitioner,

F am ily P ublications S ervice, I n c .

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. N abrit, III

E ric S chnapper

10 Columbus Circle, Suite 2030

New York, New York 10019

M. D onald D bescher

Suite 207, Sunset House

5825 Sunset Drive

South Miami, Florida 33143

Counsel for Petitioner

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PAGE

Opinion B elow ........................................................ 1

Jurisdiction .......................... ............................................ .. 1

Questions Presented ................................................... 2

Statutory Provisions and Regulations Involved______ 2

Statement of the Case ...................................................... 6

Reasons for Granting the Writ .... ................................. 9

Conclusion ............... 19

A ppendix

Opinion of the District Court ................. ............. . la

Opinion of the Court of Appeals .... ...................... 6a

Judgment of the Court of Appeals ........................ 24a

T able of A uthorities

Cases:

Federal Power Commission v. Hope Nat. Gas Co., 320

TT.S. 591 (1944) ......... ................................................... . 16

Federal Trade Commission v. Gratz, 253 U.S. 421

(1920) .................................... ...................... .................. - 15

General Telephone Co. of California v. Federal Com

munications Commission, 413 F.2d 390 (D.C. Cir.

1969) ..................... ................ .......................................... 18

11

PAGE

National Broadcasting Co. v. United States, 319 U.S.

190 (1943) .......................................................................13,15

Norwegian Nitrogen Prod. Co. v. United States, 288

U.S. 294 (1933) .............................................................17,18

Perez v. United States, 402 U.S. 146 (1971) .......... 16

Sproles v. Binford, 286 U.S. 374 (1932) ...... .......... 15,16

Strompolos v. Premium Readers Service, 326 F. Supp.

1100 .......................................... ........... 9,10,12,15,16,18,19

United States v. Shreveport Grain & Elevator Co.,

287 U.S. 77 (1932) ................... .............. ....................... 15

Statutes:

15 U.S.C. §1601 ...

15 U.S.C. §1602(e)

15 U.S.C. §1602(f)

15 U.S.C. §1602 (g)

15 U.S.C. §1604 ...

15 U.S.C. §1606(a)

15 U.S.C. §1631 ...

15 U.S.C. §1638(a)

15 U.S.C. §1640(e)

28 U.S.C. §1254(1)

...2, 9,15

..... 3

3,10,13

..... 3

3,14,15

....16,17

...... 4

...... 4

...... 7

...... 2

Ill

12 C.F.R. §226.2 (k) .............................. passim,

12 C.F.R. §226.2(1) ..... 6

12 C.F.R. §226.2(m) .................................. 6

Congressional Hearings:

Hearings Before the Consumer Subcommittee of the

House Banking and Currency Committee, 91st Cong.,

1st Sess., Part II (1969) ............................... ....... ...... 12

Miscellaneous:

“ Consumer Legislation and the Poor,” 76 Yale L.J.

745 (1967) ............................................................... 18

Davis on Administrative L a w ................................ 15

4 C.C.H. Consumer Credit Guide 1130,114 ............... 17

4 C.C.H. Consumer Credit Guide H30,228 .......... ..... 11,17

4 C.C.H. Consumer Credit Guide U30,320 ........ 17

4 C.C.H. Consumer Credit Guide 1130,434 .................. 11

4 C.C.H. Consumer Credit Guide §30,658 .................. 17

Regulations: page

I n t h e

(Euurt of % In it^ States

October Term, 1971

No..................

L eila M ourning ,

vs.

Petitioner,

F am ily P ublications S ervice, I n c .

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

The petitioner, Leila Mourning, respectfully prays that

a writ of certiorari issue to review the judgment of the

United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit

entered in this proceeding on September 27, 1971.

Opinion Below

The opinion of the Court of Appeals, not yet reported,

appears in the Appendix hereto, p. 6a. The opinion of the

District Court for the Southern District of Florida, which

is not reported, appears in the Appendix hereto, p. la.

Jurisdiction

The judgment of the Court of Appeals for the Fifth

Circuit was entered on September 27, 1971, and appears in

2

the Appendix hereto, p. 24a. This Court’s jurisdiction is

invoked under 28 U.S.C. §1254(1).

Questions Presented

1. Whether the Federal Reserve Board acted within its

statutory authority when it promulgated 12 C.F.R. §226.2

(k), defining “consumer credit” covered by the Consumer

Credit Protection Act to include any credit payable in more

than four installments?

2. Whether the Federal Reserve Board acted consistent

with the Fifth Amendment when it promulgated 12 C.F.R.

§226.2(k), defining “consumer credit’’ covered by the Con

sumer Credit Protection Act to include any credit payable

in more than four installments?

Statutory Provisions and Regulations Involved

United States Code, Title 15, §1601, 82 Stat. 146 (1968):

§1601. Congressional findings and declaration of pur

pose

The Congress finds that economic stabilization would

be enhanced and the competition among the various

financial institutions and other firms engaged in the

extension of consumer credit would be strengthened by

the informed use of credit. The informed use of credit

results from an awareness of the cost thereof by con

sumers. It is the purpose of this subchapter to assure

a meaningful disclosure of credit terms so that the

consumer will be able to compare more readily the

various credit terms available to him and avoid the

uninformed use of credit.

3

United States Code, Title 15, §1602(e), 82 Stat. 146:

(e) The term “credit” means the right granted by a

creditor to a debtor to defer payment of debt or to

incur debt and defer its payment.

United States Code, Title 15, §1602(f), 82 Stat. 146:

(f) The term “creditor” refers only to creditors who

regularly extend, or arrange for the extension of, credit

for which the payment of a finance charge is required,

whether in connection with loans, sales of property or

services, or otherwise. The provisions of this title shall

apply to any such creditor, irrespective of his or its

status as a natural person or any type of organization.

United States Code, Title 15, §1602 (g), 82 Stat. 146

(1968):

(g) The term “ credit sale” refers to any sale with

respect to which credit is extended or arranged by the

seller. The term includes any contract in the form of

a bailment or lease if the bailee or lessee contracts to

pay as compensation for use a sum substantially equiv

alent to or in excess of the aggregate value of the

property and services involved and it is of the aggre

gate value of the property and services involved and

it is agreed that the bailee or lessee m il become, or for

no other or a nominal consideration has the option to

become, the owner of the property upon full compli

ance with his obligations under the contract.

United States Code, Title 15, §1604, 82 Stat. 148 (1968):

The Board shall prescribe regulations to carry out the

purposes of this subchapter. These regulations may

contain such classifications, differentiations, or other

provisions, and may provide for such adjustments and

4

exceptions for any class of transactions, as in the judg

ment of the Board are necessary or proper to effectuate

the purposes of this subchapter, to prevent circum

vention or evasion thereof, or to facilitate compliance

therewith.

United States Code, Title 15, §1631, 82 Stat. 152 (1968):

(a) Each creditor shall disclose clearly and conspicu

ously, in accordance with the regulations of the Board,

to each person to whom consumer credit is extended

and upon whom a finance charge is or may be imposed,

the information required under this part.

United States Code, Title 15, §1638(a), 82 Stat. 156

(1968):

§1638. Sales not under open end credit plans—Re

quired disclosures by creditor

(a) In connection with each consumer credit sale not

under an open end credit plan, the creditor shall dis

close each of the following items which is applicable:

(1) The cash price of the property or service pur

chased.

(2) The sum of any amounts credited as downpay

ment (including any trade-in).

(3) The difference between the amount referred to

in paragraph (1) and the amount referred to in para

graph (2).

(4) All other charges, individually itemized, which

are included in the amount of the credit extended but

which are not part of the finance charge.

5

(5) The total amount to be financed (the sum of the

amount described in paragraph (3) plus the amount

described in paragraph (4)).

(6) Except in the case of a sale of a dwelling, the

amount of the finance charge, which may in whole or

in part be designated as a time-price differential or

any similar term to the extent applicable,

(7) The finance charge expressed as an annual per

centage rate except in the case of a finance charge

(A) which does not exceed $5 and is applicable

to an amount financed not exceeding $75, or

(B) which does not exceed $7.50 and is applicable

to an amount financed exceeding $75.

A creditor may not divide a consumer credit sale into

two or more sales to avoid the disclosure of an annual

percentage rate pursuant to this paragraph.

(8) The number, amount, and due dates or periods

of payments scheduled to repay, the indebtedness.

(9) The default, delinquency, or similar charges pay

able in the event of late payments.

(10) A description of any security interest held or

to be retained or acquired by the creditor in connec

tion with the extension of credit, and a clear identifica

tion of the property to which the security interest

relates.

12 C.F.R. §226.2 ( k ) :

(k) “ Consumer credit” means credit offered or ex

tended to a natural person, in which the money, prop

erty, or service which is the subject of the transaction

is primarily for personal, family, household, or agri

6

cultural purposes and for which either a finance charge

is or may be imposed or which pursuant to an agree

ment, is or may be payable in more than 4 instalments.

“ Consumer loan” is one type of “ consumer credit.”

12 C.F.R. §226.2(1):

(l) “Credit” means the right granted by a creditor to

a customer to defer payment of debt, incur debt and

defer its payment, or purchase property or services

and defer payment therefor. (See also paragraph (bb)

of this section.)

12 C.F.R. §226.2 (m):

(m) “Creditor” means a person who in the ordinary

course of business regularly extends or arranges for

the extension of consumer credit, or offers to extend

or arrange for the extension of such credit.

Statement of the Case

Petitioner is a seventy-three year old widow residing in

Dade County, Florida. On August 19, 1969, she entered

into a contract with the Family Publications Service, Inc.,

(hereinafter “FP:S” ), a Delaware corporation engaged in

interstate commerce, for the purchase of certain magazines.

The contract was the result of a telephone solicitation made

to petitioner followed up by a solicitation at her home.

Petitioner made an initial payment of $3.95, and contracted

to pay an equal amount monthly for a period of thirty

months. FPS agreed that petitioner would receive 4 maga

zines for a period of sixty months.

The contract, made on a standard printed form supplied

by FPS, did not disclose to petitioner the total purchase

7

price of the magazines—'$122.45. Nor did it disclose the

balance due after the initial payment, $118.50, or reveal

other information or use terminology required by the Con

sumer Credit Protection Act, 15 XJ.S.C. §§1601 et seq. Peti

tioner was required to state in writing information normally

used in a credit check, such as her occupation and business

address, and an agent of FPS wrote on the contract “ Own 4

years” , apparently indicating the period time which peti

tioner had owned her home.

The sale of magazine subscriptions under similar circum

stances is agreed to be FPS’s sole business and source of

income. FPS contracts with the magazine publishers to

supply magazines directly to its customers, and FPS

periodically reimburses the publishers out of the payments

received from subscribers. What portion of a subscriber’s

payments are paid to the publishers and what portion re

tained by FPS is not disclosed by the record.

Shortly after entering into this contract petitioner, ap

parently realizing for the first time the large amount of

money involved, refused to make further payments. There

after petitioner received at least five dunning letters from

FPS demanding at first a resumption of monthly payments

and then payment of the full $118.50 balance. The letters

stressed that petitioner had “ a credit account” , warned of

the “ embarrassment” of having her name appear on a

“monthly delinquent report” , and threatened “ expensive

and unpleasant” legal action.

On April 23, 1970, petitioner, then represented by the

Legal Services Senior Citizens Center, brought this action

in the United States District Court for Southern District of

Florida alleging that the contract violated the Consumer

Credit Protection Act. Jurisdiction of the District Court

was invoked under 15 U.S.C. §1640(e) providing for federal

jurisdiction of actions arising under the Act. Petitioner de-

8

mantled $100 in statutory damages, legal fees, and costs.*

FPS urged, inter alia, that it was not required to make any

disclosures because the transaction with petitioner did not

involve a finance charge and was thus not covered by the

Act. Petitioner maintained that she was not required to

prove that the $122.45 total cost included a. hidden finance

charge because the applicable regulation, 15 C.F.R. §226.2

(k), required disclosure whenever, as here, the contract was

payable in four or more instalments.

In connection with the proceedings in the District Court

petitioner filed affidavits of the Director and an Inspector

of the Consumer Protection Division of Metropolitan Dade

County. The affidavits stated that the Consumer Protection

Division had received over 100 complaints about FPS’s

practices, that to entice potential subscribers FPS falsely

represented it was giving away free 5 year subscriptions

to “Life” magazine, that those entering into contracts with

FPS would not have done so had they known the full con

tract price, that FPS refused to permit subscribers to cancel

contracts and used threatening and harassing tactics to en

force them. The affidavit of the Director further states

that on July 29, 1970, defendant and two of its employees

were convicted in Dade County Criminal Court of mislead

ing advertising and that FPS was ordered to cease doing

business in the State of Florida.

On November 27, 1970, the District Court held that the

four instalment rule set out in section 226.2 (k) was valid

and applicable to the facts of this case, and granted peti

tioner’s motion for summary judgment for $100 statutory

damages plus costs and a reasonable attorney’s fee. On

September 27, 1971, the Court of Appeals reversed on the

* The action was originally denoted a class action. The District

Court denied class action treatment, and petitioner did not appeal

from that decision.

9

Reasons for Granting the Writ

Title I o f the Consumer Credit Protection Act, also

known as the Truth in Lending Act, was enacted in 1968

“to assure a meaningful disclosure of credit terms so that

the consumer will be able to compare more readily the

various credit terms available to him and avoid the unin

formed use of credit,” 15 U.S.C. §1601. The Act requires

certain specified disclosures to be made in all credit con

tracts, authorizes the Federal Reserve Board to prescribe

regulations under the Act, and provides for enforcement by

a variety of administrative agencies and by private litiga

tion. The decision of the Fifth Circuit invalidated a major

regulation which the Federal Reserve Board has found to

be essential to prevent circumvention of the Act. The Fifth

Circuit’s erroneously constricted view of the Board’s rule

making authority threatens the continued vitality of the

Act, is in direct conflict with the well reasoned decision in

Strompolos v. Premium Readers Service, 326 F. Supp. 1100

(N.D. 111. 1971), and has brought about serious uncertainty

as to the legal obligations of thousands of creditors which

only this Court can resolve.

The only issue in this case is whether the transaction

between petitioner and FPS is the type of transaction in

which disclosures are legally required. FPS concedes that

it did not disclose to petitioner the total purchase price of

the magazines or several other items of information re

quired in transactions falling under the Act and regulations.

While the delineation of the types of transactions subject

to disclosure requirements depends on several definitions,

sole ground that the four instalment rule contained in Regu

lation §226.2 (k) was invalid and that FPS was therefore

not required to make any disclosures.

10

statutory provisions and regulations, the instant petition

concerns regulation §226.2 (k). That regulation provides in

pertinent part:

“Consumer credit” means credit . . . for which a finance

charge is or may be imposed or which pursuant to an

agreement, is or may be payable in more than 4 in

stallments . . . .

The District Court, in granting petitioner’s motion for

summary judgment, concluded that consumer credit was

involved because the transaction involved 30 installments

and thus fell under the second clause quoted, known as the

four installment rule. The District Court did not consider

whether the transaction might also involve consumer credit

because of the presence of a finance charge.

The Court of Appeals reversed the judgment for peti

tioner below on the sole ground that the four installment

rule on which the District Court had relied was invalid.

The Court of Appeals reasoned that, since the definition

of a “creditor” in the statute, 16 U.S.C. §1602(f), includes

only creditors extending credit for a finance charge, the

Act could only be applied to creditors who were proven to

have imposed a finance charge in each particular case.

The Court concluded that the four installment rule pur

ported to require disclosures in cases not involving finance

charges and was therefore outside the authority of the

Board and involved an unconstitutional conclusive pre

sumption that a finance charge was present in every trans

action involving more than four installments. (See pp. 16a-

23a). The decision of the Fifth Circuit is in direct conflict

with that more than four months earlier in a case involving

virtually identical facts, Strom,polos v. Premium Readers

Service, 326 F. Supp. 1100 (N.D.Ill. 1971).* The Court of

* Strompolos is now on appeal before the Seventh Circuit Court

of Appeals.

11

Assuming, arguendo, that Title I of the Consumer Credit

Protection Act is concerned primarily with disclosures in

transactions involving finance charges, the four installment

rule embodied in §226.2 (k) is nonetheless well within the

statutory authority of the Board.

The four installment rule is founded upon an explicit and

reiterated finding by the Federal Reserve Board that such

a rule is essential to prevent wholesale evasion of the Act.

In an opinion letter issued eight days after the regulation

became effective, Vice-Chairman Robertson of the Board

explained:

The Board considers this to be a rather significant

part of the Regulation, intended as a deterrent to those

who might cease to charge a finance charge but, in

stead, inflate their so-called “cash” price and thus avoid

compliance. 4 C.C.H. Consumer Credit Guide, Tf.30,434.

Six months later, on December 9, 1969, Governor Robertson

wrote:

We believe that without this general provision [the

four instalment rule] the practice of burying the finance

charge in the cash price, a practice which already exists

in many cases, would be encouraged by Truth in Lend

ing. In order to prevent this ironic result we felt it

imperative to establish the more than four payment

rule. 4 C.C.H. Consumer Credit Guide f[30,228.

Again on March 3, 1970, Governor Robertson explained:

The Board felt that it was imperative to include trans

actions involving more than four instalments under

Appeals, however, neither mentioned Strompolos nor pur

ported to consider the detailed reasoning given therein for

upholding the validity of regulation §226.2 (k).

12

the Regulation since without this provision the prac

tice of burying the finance charge in the cash price,

a practice which already exists in many cases, would

have been encouraged by Truth in Lending. Conse

quently we believe that this is a rather important part

of the Regulation. . . . 4 C.C.H. Consumer Credit

Guide; 1j30,320.

See also Hearings Before the Consumer Subcommittee of

the House Banking and Currency Committee, 91st Cong.,

1st Sess., Part II, p. 375 (1969).

The District Court in Strompolos also concluded that the

four instalment rule was essential to avoid evasion:

We agree with the Federal Reserve Board’s evaluation

of the necessity of this type of regulation.

The facts of this particular case may very well dem

onstrate why the four installment rule is not only

sensible but also necessary to prevent the Truth in

Lending Act from being a hoax and a delusion upon

the American public. Although the defendant con

tends that it charges the same unitary price for both

credit and cash sales, it is readily apparent that a

seller in any industry which sells primarily or almost

exclusively on a long term credit basis could easily

set a theoretical unitary cash and credit price which

he knows no one will pay in less than four installments

and thus exempt himself and his industry from the

coverage of the Act. . . .

It is most logical that the Federal Reserve Board

would . . . plug a loophole by which a substantial por

tion of long term credit dealers could escape from

the Act’s coverage. Neither the law, the Federal Re

serve Board nor the courts are so simplistic as to

13

believe that a person in the business of extending long

term credit should be permitted in effect to abolish

the Truth in Lending Act by merely charging a single

“cash or credit” price knowing full well that the great

bulk of its customers will never pay in less than, for

example, thirty months.

. . . Were the Board not to have promulgated this

rule nor the courts to sustain it, the Truth in Lending

Act might never achieve its stated goals. 326 F. Supp.

at 1103-04.

The Board’s finding that the regulation is essential to pre

vent wholesale evasion of the Act is not subject to judicial

review absent a clear showing of abuse of discretion on the

part of the Board. National Broadcasting Co. v. United

States, 319 U.S. 190, 224 (1943). The Court of Appeals in

the instant case, however, completely ignored both this

principle of deference to the Board’s expertise and the find

ing of the Board.

The Court of Appeals reasoned that if the literal defini

tion of “creditor” in 15 XJ.S.C. §1602 (f) permitted on its

face a scheme which would make a shambles of the entire

statute, there was absolutely nothing the Board could do

about it. This argument seriously misconstrues the pur

pose of the Act and the authority given to the Board.

Congress did not intend to require exactly and only the dis

closures set out in the statute under exactly and only those

circumstances defined therein, authorizing the Board to

merely resolve minor ambiguities. Rather the Congress

intended, as it stated, “to assure meaningful disclosure of

credit terms” , and to this end set out a rough outline of

what disclosures it believed would be needed under what

circumstances to effectuate this purpose, and left it to the

Board to fill in the details, correct any oversights or omis

sions, and make any necessary exceptions.

14

The express grant of rule making authority to the Board

is extremely broad, and encompasses both interpretative

and legislative rules:

The Board shall prescribe regulations to carry out the

purposes of this title. These regulations may contain

such classifications, differentiations, or other provi

sions, and may provide for such adjustments and ex

ceptions for any class of transactions, as in the judg

ment of the Board are necessary or proper to effectu

ate the purposes of this title, to prevent circumvention

or evasion thereof, or to facilitate compliance there

with. 15 U.S.C. §1604.

The grant of authority to avoid evasion is particularly ap

plicable here. As the District Court reasoned in Strompolos:

The wording of section 105 of the Act [15 U.S.C.

§1604] clearly indicates, not only that Congress dele

gated to the Board authority to issue regulations to

effectuate the purposes of the Act, but that Congress

also went further and granted the Board the power

to promulgate, at its discretion, regulations necessary

to prevent circumvention of the Act. The use of the

word “ circumvention” in the Act signifies that Congress

was aware that some creditors who would otherwise

fall within the purview of the Act might, after passage

of the Act, attempt to restructure their consumer busi

ness relations in such a manner that they might techni

cally avoid the wording of the Act.

Along with the recognition of this potential for eva

sion, Congress also recognized the equally obvious fact

that no legislative body could conceivably put into a

workable piece of legislation regulations and restric

tions covering every imaginable business transaction

wherein credit may be involved. Consistent with other

15

complex regulatory legislation, Congress granted an

administrative agency the power to apply the basic

purposes of the Act to the everyday world. Not only

did Congress order the Federal Reserve Board to

promulgate regulations to effectuate the purposes of

the Act, it also took the further affirmative step of

enabling the Board to reach creditors, who in the

Board’s judgment, were attempting to circumvent or

evade the Act by structuring their credit activities to

fall a fine line outside the Act. 326 F. Supp. 1103-04.

Indeed, as the instant case makes clear, if the grant of au

thority to prevent evasion does not include the power to

reach transactions just outside the literal reach of the

statute that grant is meaningless.

That Congress should have given the Board the authority

to modify the details of its statutory plan is not unusual.

Congress could of course have given the Board the rule

making authority set out in section 1604, and the broad

statement of purpose in section 1601, and left it to the

Board to promulgate the entire regulatory scheme. Com

pare National Broadcasting Co. v. United States. 319 U.S.

190 (1943) (F.C.C. authorized to regulate broadcast indus

try in accordance with “public convenience, interest, or

necessity” ) ; Federal Trade Commission v. Grafs, 253 U.S.

421 (1920) (F.T.C. authorized to define and prevent “un

fair methods of competition” ). It was entirely proper for

the Congress in the instant case to set out, in addition to a

statement of the ultimate purpose to be sought by the

Board, a sketch of how it thought that goal would be

achieved subject to such “variations, extensions, or exemp

tions” as the Board might find necessary to effectuate the

general purpose of the Act. Davis on Administrative Law

§20; United States v. Shreveport Grain & Elevator Co., 287

U.S. 77, 85 (1932); Sproles v. Binford, 286 U.S. 374, 397

16

(1932); compare Federal Power Commission v. Hope Nat.

Gas Co., 320 U.S. 591 (1944). It is not, of course, necessary

in each individual case for the Board to establish that the

creditor is seeking to evade the law. Such a requirement

would reduce the Board to proving the existence of a finance

charge in each case and render nugatory its power to

promulgate rules to avoid evasion. The Board need only

have a reasonable basis for concluding that its regulation

of the class of activities involved is necessary to effectuate

the purposes of the Act. Compare Peres v. United States,

402 U.S. 146 (1971).

The four installment rule is also necessary to avoid

hopeless confusion as to when a creditor in FPS’s position

has imposed a finance charge and is thus required to make

disclosures. “Finance charge” is defined broadly in the

statute to include “ the sum of all charges, payable directly

or indirectly by the person to whom the credit is extended,

and imposed directly or indirectly by the creditor as an

incident to the extension of credit. . . 15 U.S.C. §1606(a).

As the District Court pointed out in Strompolos, 326 F.

Supp. at 1103, the fact that a creditor purports to have

a cash price equal to his credit price may only mean that

the finance charge is well hidden.

As a practical matter any creditor who permits a cus

tomer to defer payment of an obligation for goods or ser

vices already provided or paid for by the creditor must

as a consequence borrow from a third party or his own

capital reserves and incur a finance charge or resulting

loss of interest. He must also maintain, as FPS evidently

did, some form of collection department. The costs of the

creditor’s borrowing and collections, as well as his bad debt

reserve, must ultimately and literally come out of his

customer’s pockets, since, as in the case of FPS, their

17

payments to him are his only source of funds, regardless

of whether the creditor in any sense “ intends” to bury a

finance charge in his prices. FPS presumably met all these

costs out of the difference between the amount received

from its customers and the amount it paid to the magazine

publishers. The statute sets no standards, however, for

determining the existence and amount of a finance charge

under these circumstances, and the Court of Appeals in

the instant case intimated no suggestions as to what sort

of proof petitioner could have offered along these lines.

Section 226.2 (k) resolves this problem as a practical

matter by requiring disclosures in all transactions involv

ing more than four installments. The section may be

understood as an interpretation of the definition of “ finance

charge” in Section 1606(a). As such it would reflect the

Board’s apparent conclusion that it -would not be feasible

to determine for categories of transactions or on a case

by case basis when the price paid by the consumer includes,

purposely or otherwise, part of all of the costs necessarily

incurred by the creditor in extending credit. See 4 C.C.H.

Consumer Credit Guide 1130,228.

In the instant case both the Federal Reserve Board and

the Federal Trade Commission, which share the primary

responsibility for interpreting and enforcing the Act, be

lieve that the four installment rule set out in §226.2 (k) and

promulgated within a year of the passage of the Act is a

valid use of the Board’s general rule making authority.

See 4 C.C.H. Consumer Credit Guide 1ffl30,ll4, 30,658. A

strong presumption of validity attaches to “a contempo

raneous construction of a statute by the men charged with

the responsibility of setting its machinery in motion, of

making the parts work efficiently and smoothly while they

are yet untried and new.” Norwegian Nitrogen Prod. Co. v.

18

United States, 288 U.S. 294, 315 (1933). The presumption

is particularly weighty when the regulation involved is

directed at effectuating the ultimate purposes of the Act.

General Telephone Co. of California v. Federal Communi

cations Commission, 413 F.2d 390, 403 (D.C.Cir. 1969).

The decision of the Court of Appeals in the instant case

is not only clearly erroneous, but has opened the door to

wholesale evasion of the Consumer Credit Protection Act.

If the four installment rule is invalidated there will be

little if any incentive to prevent merchants from reverting

with avengeance to the practices common prior to the

passage of the Act, disclosing neither finance charges, in

terest rates, or total prices for their goods. The success

of such a scheme of evasion will give merchants selling

on credit a substantial and unwarranted competitive edge

over hanks and other lenders who have no price in which

to bury their finance charges. Such results would have a

particularly adverse effect on the poor. Burying finance

charges and advertising “free credit” was especially com

mon prior to 1969 in ghetto neighborhoods, and low income

consumers are particularly susceptible to these practices

because they are least likely to ask the total cost of some

good or service so long as the monthly payments seems

within their reach. See Comment, “ Consumer Legislation

and the Poor,” 76 Yale L.J. 745, 762-63 (1967). Moreover,

the Court of Appeals’ constricted view of the Board’s rule

making authority calls into question the validity of, and is

likely to precipitate a flury of attacks on the many other

regulations with which creditors may prefer not to comply.

The need for a final ruling by this Court on the validity

of the four installment rule is particularly great because

of the financial stakes involved. The regulation invalidated

by the Fifth Circuit is still being enforced in the Northern

District of Illinois because of Strompolos. Throughout the

19

rest of the country there is general uncertainty as to

whether compliance is necessary in view of the conflict be

tween the instant case and Strompolos. A creditor who

gambles that the regulation will be invalidated in his Cir

cuit and loses may be liable for millions of dollars in statu

tory damages. A creditor who presumes incorrectly that

the regulation will be held valid in his area stands to lose

a substantial amount of business because of the competitive

edge assumed by his non-complying competitors. The nine

federal agencies charged with enforcing the Act as to vari

ous groups of creditors are themselves left in a quandary

as to how to proceed pending a final resolution of this

question.

CONCLUSION

For these reasons, a writ of certiorari should issue to re

view the judgment and opinion of the Fifth Circuit.

Respectfully submitted,

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. Nabrit, III

E ric S chnapper

10 Columbus Circle, Suite 2030

New York, New York 10019

M. D onald D rescher

Suite 207, Sunset House

5825 Sunset Drive

South Miami, Florida 33143

Counsel for Petitioner

APPENDIX

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

S outhern D istrict of F lorida

M ia m i D ivision

No: 70-559-Civ-WM

Filed November 27, 1970

L eila M ourning , on beh a lf o f h erse lf and

a ll those sim ilarly situated,

Plaintiffs,

vs.

F am ily P ublications S ervice, I n c .,

Defendant.

AMENDED ORDER GRANTING FINAL SUMMARY

JUDGMENT TO PLAINTIFF, DENYING DEFEND

ANT’S MOTION FOR SUMMARY JUDGMENT AND

DISMISSING CLASS ACTION CLAIM

T h is Cause came on to be heard upon the Defendant’s

motion to amend this Court’s Order and judgment entered

October 30, 1970, and the Court having heard argument

of counsel, and having considered the memoranda sub-

la

2a

mitted by counsel for the parties, and being otherwise

fully advised in the premises,

The Court finds that the Plaintiff, L eila M ourning , can

not fairly and adequately protect the interests of the

alleged class in this cause, and any previous order herein

to the contrary is superceded by this Order and Judgment,

and it is therefore,

Ordered and A djudged that this action shall not be

m aintained as a class action, and the class action claim

o f the “ second am ended com plain t” is h ereby dism issed,

and it is further,

Ordered and A djudged that this Court’s Order of

October 30, 1970, be and it is hereby vacated and amended

to state as follows:

T h is Cause having come on before me upon Motions

for Summary Judgment filed by the parties, Philip L.

Coller, Esq. of the Legal Services Senior Citizens Center,

and M. Donald Drescher, Esq., appearing for the Plaintiff,

and Peter Fay, Esq. of Prates Fay Floyd & Pearson, P.A.,

appearing for the Defendant, and the Court having heard

argument of counsel and being otherwise fully advised

in the premises, makes the following findings of fact and

conclusions of law:

F indings of F act

This action is founded on the Consumer Credit Protec

tion Act (Title I, Truth in Lending Act) 15 USC §1601

et seq., and the Regulations duly promulgated thereunder

by the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System

Amended Order Granting Final Summary Judgment

3a

(Regulation Z, 12 CFR §§226.1-226.12). The relief sought

is recovery of a civil penalty imposed by the Act for fail

ure to make disclosures required by the Act and its Regu

lations.

There is no issue as to any material fact. Defendant

admits (1) that it entered into a written standard form

contract with the named Plaintiff and other members of

this class; and (2) that the standard form contract did

not contain the disclosures specified by the Truth in

Lending Act. Further, Defendant admits contacting the

named Plaintiff on several occasions subsequent to the

filing of this suit to enforce collection of a debt asserted

by Defendant against the Plaintiff. Defendant is engaged

in the interstate business of soliciting subscriptions to

magazines and offering contracts therefor. The contract

on its face provides that the customer agrees to pay a

stated sum over a period of 24 or 30 months, that it is

non-cancellable and that “Payments due monthly, other

wise entire balance due.”

Plaintiff Leila Mourning entered into a standard form

contract with the Defendant on August 19, 1969. Subse

quent to July 1, 1969, the date the Act went into effect,

a number of other individuals in Dade County entered

into identical or similar contracts with the Defendant.

The sole question presented is : “ Does the transaction

here sued upon come within the scope of the Truth in

Lending Act and the Regulations duly promulgated there

under?”

Amended Order Granting Final Summary Judgment

Conclusion 's of L aw

A. The Truth in Lending Act and the Regulations must

be interpreted so as to be consistent with each other and

4a

with the declared Congressional purpose of the Act—-

“to assure meaningful disclosure of credit terms.”

B. The uncontroverted evidence before the Court plainly

demonstrates that it is the intent of the Begulation and

the interpretation of the Federal Reserve Board and of

the staff of the Federal Trade Commission that the trans

action here in question falls squarely within the scope

of the Act and its Regulations by virtue of the “more than

four installments” rule, 12 CFR §226.2 (k); F.R.B. Letter,

July 24, 1969, 1 CCH, Consumer Credit Guide, §§30,113, 30,

114; FTC Letter, September 3, 1970 (in Court file); CLE,

TRUTH IN LENDING IN FLORIDA, Chapter 2.2(1))“;

Tanner, Truth in Lending and Regulation Z — A Primer,

6 Ga. S.B.J. 1 (Aug. 1969).

C. The uncontroverted facts show that Consumer credit

was extended by the Defendant to the Plaintiff. The

Plaintiff received a present contract right—a subscription,

in exchange for a promise to pay a certain sum in more

than four installments. The promise to pay is uncondi

tional and non-cancellable, and, further, the written agree

ment provides that “Payments due monthly, otherwise

entire balance due.” The evidence before the Court regard

ing the named Plaintiff reveals that the Defendant, itself,

considered the transaction to be a credit transaction, and

that it was owed a debt by the Plaintiff.

D. No constitutional question is presented by the case

at bar.

E. The answer to the question presented to the Court

must be “yes,” and since the Defendant has extended

“ Consumer credit” within the meaning of the Truth in

Lending Act and its Regulations and has failed to make

Amended Order Granting Final Summary Judgment

5a

the material disclosures required by 15 USC §1631 and

12 CFR §226.8, the Defendant is liable to the Plaintiff

for the penalties imposed by 15 USC §1640(a).

Accordingly, it is Ordered and A dju dicated :

1. That the motion of Plaintiff, L eila M ourning , for

summary judgment be and the same is granted and the

Defendant’s motion for summary judgment is denied.

2. That as a penalty for its failure to provide the

disclosures required by the Act and its Regulations, the

Defendant shall pay to the Plaintiff, L eila M ourning ,

the sum of One Hundred Dollars ($100.00).

3. That the Clerk of this Court shall enter final judg

ment in favor of Plaintiff, L eila M ourning , against the

Defendant, F am ily P ublications S ervice, I n c ., in the

amount of One Hundred Dollars ($100.00), plus 1500.00

on behalf of Plaintiff, L eila M ourning , as a reasonable

attorneys’ fee and the costs of this action.

D one and Ordered in Chambers at Miami, Florida, on

this 27th day of November, 1970.

/ s / W . M ehrtens

United States District Judge

Amended Order Granting Final Summary' Judgment

6a

I n the

UNITED STATES COURT1 OF APPEALS

F ob t h e F if t h C ircuit

Opinion of United States Court of Appeals

For the Fifth Circuit

No. 71-1150

L eila M ourning , et al .,

Plaintiffs-Appellees,

versus

F am ily P ublications S ervice, I n c .,

D efendant-A ppellant.

APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR TH E SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF' FLORIDA

(September 27, 1971)

Before

Colem an , S im pson , and R oney,

Circuit Judges.

Colem an , Circuit Judge: The validity of Regulation Z,1

promulgated by the Federal Reserve Board under the

Truth-In-Lending Act,2 is the material issue in this appeal.

The District Court held for validity. We reverse.

112 C.F.R. 226.

215 U.S.C., §1601, et seq.

7a

I

The Facts

Appellant, Family Publications Service, Inc., is a Dela

ware Corporation engaged in tire interstate business of

soliciting subscriptions and offering contracts for the sale

and delivery of a large number of well known periodicals.

The appellee Leila Mourning, is a seventy-three year old

widow having her domicile in Dade County, Florida.

Under appellant’s method of conducting its business for

the sale and delivery of well known periodicals, the cus

tomer under a standard form contract agrees to receive

his particular magazine selections for 48 (or 60) months

and to pay for them over the first 24 (or 30) months. Under

normal operating circumstances, the appellant expects to

receive a prepayment for magazines to be delivered to the

customer in the future. The only circumstances in which

magazines are occasionally delivered prior to appellant’s

receipt of payment for them is when a. customer defaults in

making the prepayment. According to the appellant, these

transactions, contractual in nature, for the sale and delivery

of magazines do not involve the extension of credit as de

fined by the Truth-In-Lending Act or the imposition of a

finance charge, either directly or indirectly, requiring the

disclosures specified in the Truth-In-Lending Act.

On August 19, 1969, appellee entered into a written con

tract with the appellant for the purchase of the Ladies Some

Journal, Holiday, Life, and Travel and Camera. As usual,

the standard form contract required the appellee to make

thirty monthly payments of $3.95 each, in return for which

she would receive magazines for sixty months. The contract

provided that it was non-cancellable and that failure to

Opinion of United States Court of Appeals

For the Fifth Circuit

8a

make the monthly payments would result in the entire bal

ance becoming due. Said contract is the only instrument

executed and existing between the parties and it does not

contain a disclosure as to the total purchase price, finance

charges, service charges, or the amount to be financed.

Although Leila Mourning, the appellee, received the mag

azines ordered, she defaulted on her contract and never

made any payments beyond the initial $3.95'. Consequently,

her contract was cancelled by Family Publications Service,

Inc., on April 15, 1970. Appellant admits contacting the

named appellee on several occasions seeking to enforce the

contract. In those letters, appellant explained that it had

already entered her subscriptions for the entire period;

that it was a financier which had fully invested in her con

tract and would not receive a refund from the publishers;

that Mrs. Mourning would have had to pay in advance had

she dealt directly with the publishers; that she had an obli

gation to repay appellant on her “credit” account, much the

same as if she had purchased any other type of merchan

dise ; and that the entire balance of $118.50 was due.

On April 23, 1970, Mrs. Mourning filed her civil suit as

serting that the appellant, Family Publications Service,

Inc., had failed to make the disclosures required by the

Truth-In-Lending Act and, on that basis seeking the civil

penalty, including the attorney’s fees, prescribed by the

Act.

II

The Decision of the District Court

Both Mrs. Mourning and Family Publications, Inc. moved

for summary judgment. The judgment went to the plain

tiff, in the following language:

Opinion of United States Court of Appeals

For the Fifth Circuit

9a

“ T h is Cause having come on before me upon Motions

for Summary Judgment filed by the parties, Philip L.

Coller, Esq. of the Legal Services Senior Citizens

Center, and M. Donald Drescher, Esq., appearing for

the Plaintiff, and Peter Fay, Esq. of Frates Fay Floyd

& Pearson, P.A., appearing for the Defendant, and the

Court having heard argument of counsel and being

otherwise fully advised in the premises, makes the

following findings of fact and conclusions of law:

F ihdiwgs oe F act

“ This action is founded on the Consumer Credit Pro

tection Act (Title I, Truth in Lending Act) 15 USC

§1601 et seq., and the Regulations duly promulgated

thereunder by the Board of Governors of the Federal

Reserve System (Regulation Z, 12 CFR §§226.1-226.12).

The relief sought is recovery of a civil penalty imposed

by the Act for failure to make disclosures required by

the Act and its Regulations.

“ There is no issue as to any material fact. Defen

dant admits (1) that it entered into a written standard

form contract with the named Plaintiff and other mem

bers of this class; and (2) that the standard form

contract did not contain the disclosures specified by

the Truth in Lending Act. Further, Defendant admits

contacting the named Plaintiff on several occasions

subsequent to the filing of this suit to enforce collection

of a debt asserted by Defendant against the Plaintiff.

Defendant is engaged in the interstate business of

soliciting subscriptions to magazines and offering con

tracts therefor. The contract on its face provides that

the customer agrees to pay a stated sum over a period

Opinion of United States Court of Appeals

For the Fifth Circuit

10a

of 24 or 30 months, that it is non-cancellable and that

‘Payments due monthly, otherwise entire balance due’ .

“Plaintiff Leila Mourning entered into a standard

form contract with the Defendant on August 19, 1969.

Subsequent to July 1, 1969, the date the Act went into

effect, a number of other individuals in Dade County

entered into identical or similar contracts with the

Defendant.

“ The sole question presented is: ‘Does the transac

tion here sued upon come within the scope of the Truth

in Lending Act and the Regulations duly promulgated

thereunder!’

Conclusions o r L aw

“A. The Truth in Lending Act and the Regulations

must he interpreted so as to be consistent with each

other and with the declared Congressional purpose

of the Act—-‘to assure meaningful disclosure of credit

terms.’

“B. The uncontroverted evidence before the Court

plainly demonstrates that it is the intent of the Regu

lation and the interpretation of the Federal Reserve

Board and of the staff of the Federal Trade Com

mission that the transaction here in question falls

squarely within the scope of the Act and its Regula

tions by virtue of the ‘more than four installments’

rule, 12 CFR §226.2 (k ) ; F.R.B. Letter, July 24, 1969,

1 CCH, Consumer Credit Guide, §§30,113, 30,114;

FTC Letter, September 3, 1970 (in Court file); CUE,

TRUTH IN LENDING IN FLORIDA, Chapter 2.2

(D) Tanner, Truth in Lending and Regulation Z -----

A Primer, 6 Ga. S.B.J. 1 (Aug. 1969).

Opinion of United States Court of Appeals

For the Fifth Circuit

11a

“ C. The uncontroverted facts show that Consumer

credit was extended by the Defendant to the Plaintiff.

The Plaintiff received a present contract right—a

subscription, in exchange for a promise to pay a

certain sum in more than four installments. The pro

mise to pay is unconditional and non-caneellable, and,

further, the written agreement provides that ‘Pay

ments due monthly, otherwise entire balance due’. The

evidence before the Court regarding the named Plain

tiff reveals that the Defendant, itself, considered the

transaction to be a credit transaction, and that it was

owed a debt by the Plaintiff.

“D. No constitutional question is presented by the

case at bar.

“E. The answer to the question presented to the

Court must be ‘yes,’ and since the Defendant has

extended ‘Consumer credit’ within the meaning of the

Truth in Lending Act and its Regulations and has

failed to make the material disclosures required by

15 U8C §1631 and 12 CFR §226.8, the Defendant is

liable to the Plaintiff for the penalties imposed by

15 DSC §1640(a).

“Accordingly, it is Ordered and A dju dicated :

“ 1. That the motion of Plaintiff, L eila M ourning ,

for summary judgment be and the same is granted

and the Defendant’s motion for summary judgment

is denied.

“2. That as a penalty for its failure to provide the

disclosures required by the Act and its Regulations,

Opinion of United States Court of Appeals

For the Fifth Circuit

12a

the Defendant shall pay to the Plaintiff, L eila

M ourning , the snm of One Hundred Dollars ($100.00).

“3. That the Clerk of this Court shall enter final

judgment in favor of Plaintiff, L eila M ourning ,

against the Defendant, F am ily P ublication S ervice,

I n c ., in the amount of One Hundred Dollars ($100.00),

plus 1500.00 on behalf of Plaintiff, L eila M ourning ,

as a reasonable attorneys’ fee and the costs of this

action.”

We have included the Findings and Conclusions be

cause they reveal the absence of any finding that a

finance charge was involved in this transaction. The

defendant’s answer denied the existence of such a charge,

and the plaintiff did not traverse it. The long and the

short of it is that the plaintiff and the court stood on the

Regulation.

Opinion of United States Court of Appeals

For the Fifth Circuit

I l l

The Truth-In-Lending Act,

Its Statutory Scheme, and

Regulation Z

Recognizing that the full disclosure of finance charges

would greatly aid consumers in deciding for themselves

the reasonableness of the credit charges imposed and

would thereby enable consumers to effectively shop for

credit, the Truth-In-Lending Act, Title I of the Consumer

Credit Protection Act, Public Law 90-321, 82 Stat. 146,

was enacted by the Congress, establishing the statutory

requirement that as a matter of fair play to the consumers

13a

the cost of credit should be disclosed fully, simply, and

clearly. United States Code Congressional and Adminis

trative News, 90th Congress, Second Session (1968), pp.

1962, 1965. It was the feeling- of the Congress that “the

informed use of credit results from an awareness of the

cost thereof by consumers” . 15 U.S.C., §1601.

The basic thrust of the Truth-In-Lending Act is that

each creditor who regularly extends, or arranges for his

debtors in consumer transactions to defer payment of debt

or to incur debt and defer its payment and -who thereby as

an incident to such extension or arrangement for the de

ferred payment of debt imposes either directly or indirectly

a finance charge for such deferred debt, shall disclose clearly

and conspicuously, in accordance with the regulations of the

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, to each

person to whom such right of deferred payment of debt

is granted and upon which right a finance charge is or may

be imposed, the information required by 15 U.S.C., §1638(a),

15 U.S.C., §1602(e) and (f), §1605(a), §1631(a). Accord

ing to such section, 15 U.S.C., §1638(a), in any consumer

transaction, not under an open end credit plan, where the

debtor is granted the right to defer payment of debt or to

incur debt and defer its payment, and for which right the

payment of a finance charge is required of the debtor by the

creditor, the creditor shall disclose each of the folio-wing

items:

1. The cash price of the item purchase, 15 U.S.C.,

§1638(a)(1).

2. The amount of the down payment, 15 U.S.C.,

§1638(a )(2).

Opinion of United States Court of Appeals

For the Fifth Circuit

14a

3. The difference between the cash price of the item pur

chased and the amount of the down payment, 15

U.S.C., §1638 (a) (3),

4. All additional charges, individually itemized, which

are included in the amount of the credit extended but

which are not part of the finance charge, 15 U.S.C.,

§1638(a ) (4).

5. The total amount to be financed (the sum of # 3 and

# 4 ) , 15 U.S.C., §1638(a ) (5).

6. Amount of the finance charge, 15 U.S.C., §1638(a) (6).

7. The annual percentage rate of the finance charge, 15

TJ.'S.C., §1638(a) (7).

8. The schedule of payments required, 15 U.S.C.,

§1638(a )(8).

9. The charges for late payments, 15 U.S.C., §1638(a) (9).

10. A description of any security interest involved, 15

ILS.C., §1638(a) (10).

In order to assure the effective operation of the statutory

provisions of the Act and to assure the meaningful dis

closures of credit terms so that all consumers would be able

to compare more readily the various credit terms available

and thereby avoid the uninformed use of credit, the Act

delegated to the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve

System the authority to promulgate regulations to accom

plish the above-mentioned objectives, 15 TT.S.C., §1604. This

section expressly authorized the Board of Governors to

promulgate regulations containing such classifications, dif

ferentiations, or other provisions, and providing for such

Opinion of United States Court of Appeals

For the Fifth Circuit

adjustments and exceptions for any class of transactions, as

in the judgment of the Board of Governors are necessary

or proper to effectively effectuate the purposes of the

Truth-In-Lending Act, to prevent the circumvention or

evasion of such statutory provisions, or to facilitate com

pliance with such provisions. In connection with the Truth-

In-Lending Act’s delegation of authority to promulgate

regulations, the Act provided that any reference in the Act

to requirements imposed by the Act included reference to

the Board of Governor’s regulations, 15 U.S.C., §1602 (k).

In addition to the specification in the Truth-In-Lending

Act of criminal penalties for the wilful and knowing failure

of a creditor to make the required disclosures of 15 U.S.O.,

§1638(a), or for failing to comply with any other require

ments of the Act, 15 U.S.C., §1611, the Act established two

methods of civil enforcement. One is administrative in

nature and is vested (1) in a number of federal agencies

which already exercised jurisdiction by virtue of other

statutory authority, over particular classes of creditors, 15

U.S.C., §1607(a), and (2) in the Federal Trade Commis

sion with respect to all other creditors, 15 U.S.C., §1607(c).

The other civil remedy established by Congress was made

available directly to consumers. Specifically, the Act estab

lished federal court jurisdiction over actions for a civil

penalty and authorized the courts, in successful actions, to

award the consumer a reasonable attorneys’ fee, 15 LT.S.C.,

§1640(a) and (e). The amount of the civil penalty was set

at “ an amount equal to the sum of twice the amount of the

finance charge in connection with the transaction” , except

that the penalty could not be less than $100 nor greater than

$1,000, 15 U.S.C., §1640(a).

Opinion of United States Court of Appeals

For the Fifth Circuit

16a

The Four Installment Rule of Regulation Z

On February 10, 1969, the Board of Governors of the

Federal Reserve System implemented the Act by promulgat

ing a set of regulations dealing comprehensively and

thoroughly with all aspects of the Truth-In-Lending Act.

Within these regulations there was included a provision

that the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve Sys

tem determined that the Act’s disclosure requirements

would be applied not only to those creditors who extend

consumer credit which involves an expressly stated finance

charge, lout also those who extend consumer credit for which

no finance charge is stated hut which pursuant to agree

ment, is or may he payable in more than four installments.

The purpose, indeed the inescapable result of the Regula

tion, is the imposition of a conclusive presumption that

those who extend credit and permit payment in four or

more installments have added a finance charge for the ex

tension of credit.

The primary question, then, is: Was such a require

ment within the delegated authority of the Board?

IV

Our Decision

As already stated, the Act requires that “ each creditor

shall disclose clearly and conspicuously, in accordance with

the regulations of the Board, to each person to whom con

sumer credit is extended and upon whom a finance charge

is or may be imposed, the information required under 15

U.S.G., §1638(a).” 15 U.S.C., §1631(a). For failure in con

nection with any consumer credit transaction to disclose

Opinion of United States Court of Appeals

For the Fifth Circuit

17a

to any person information required by 15 U.S.C., §1638(a),

tire Truth-In-Lending Act imposes on such creditor civil

liability, 15 U.S.C., §1640, and in cases of wilful and know

ing violation of the disclosure requirement, criminal lia

bility, 15 U.S.C., §1611. This particular action was brought

under the civil liability provisions.

Mindful of the Supreme Court’s decision in Federal

Communication Commission v. American Broadcasting

Company, 347 U.S. 284, 290 (1954), that penal statutes are

to be strictly construed, and mindful that it is the duty of

the judiciary to finally determine the proper construction of

statutes, this Court construes 15 U.S.C., §1631 to require

that three essential elements must be found present together

in a transaction before a person is obligated under the

Truth-In-Lending Act to make the information disclosures

listed in 15 U.S.C., §1638(a). These three essential elements

consist of the following:

First, there must be found present a creditor as defined

by the Act, or a person who regularly extends or arranges

for the extension of the right to defer payment of debt, or

to incur debt and defer its payment, and for which right of

deferred payment the payment of a finance charge is re

quired, 15 U.S.C., §1602(e) and (f).

Secondly, there must be found present a consumer credit

transaction as defined by the Act, or a transaction in which

the person to whom is extended the right to defer payment

of debt or to incur debt and defer its payment is a natural

person, and the money, property, or services which are the

subject of the transaction are primarily for personal,

family, household, or agricultural purposes, 15 U.S.C.,

§1602(e) and (h).

Opinion of United States Court of Appeals

For the Fifth Circuit

18a

Thirdly, there must be found present a “finance charge”

as defined by the Act, 15 U.S.C., §1605(a), and §1602(e) and

(f).

Regulation Z provides:

“ Consumer credit means credit offered or extended

to a natural person, in which the money, property,

or service which is subject of the transaction is

primarily for personal, family, household, or agri

cultural purposes for which either a finance charge

is or may be imposed or which, pursuant to an agree

ment, is or may be payable in more than four install

ments.”

According to the brief of the United States as amicus

curiae, the four installment rule in effect establishes a

conclusive presumption that those who extend credit and

allow payment in four or more payments have included

within the price which the consumer pays for their product

their cost of extending credit, notwithstanding that they

purport not to levy a finance charge. Therefore, we can

conclude from the Regulation promulgated by the Board

of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, from the

decision of the lower district court, and from the brief filed

in this cause by the United States as amicus curiae, that in

order for the disclosure and penalty provisions of the

Truth-In-Lending Act to be applicable, all that is required

is that the transaction involve the extension of credit

which, pursuant to agreement, is or may be payable in

more than four installments. No showing or finding of the

imposition, directly or indirectly, of a finance charge is

necessarily required. The presence of a finance charge

Opinion of United States Court of Appeals

For the Fifth Circuit

19a

is conclusively presumed from the nature of the trans

action, involving payment in more than four installments.

It can be readily seen from a consideration of the four

installment rule of Regulation Z as defined by the appellee

and from a consideration of this Court’s construction of

the statutory provisions of the Truth-In-Lending Act that

an inconsistency exists between the four installment rule

and the Truth-In-Lending Act. On the one hand, the four

installment rule requires the application of the disclosure

and penalty provisions of the Truth-In-Lending Act to

transactions involving the extension of credit which, pur

suant to agreement, is or may be payable in more than four

installments, whether or not a finance charge is proven

to have been imposed, directly or indirectly, as an incident

to the extension of credit. On the other hand, the statutory

provisions of the Truth-In-Lending Act requires that a

finance charge must be found present, directly or indirectly,

along with the other two essential elements in a trans

action before such transaction is considered to be subject

A

to the penalty and disclosure provisions of the Truth-In-

Lending Act.

By extending the applicability of the disclosure and

penalty provisions of the Truth-In-Lending Act to trans

actions involving the extension or credit repayable by

agreement in more than four installments, whether or not

there is found in such transactions the imposition of a

finance charge as an incident to the extension of credit,

the Board of Governors, in our opinion, over-stepped the

authority granted to them under 15 IT.S.C., §1604. The

authority delegated to the Board of Governors to prescribe

such regulations as they deem necessary and proper to

further the purposes of the Act and to prevent the cir-

Opinion of United States Court of Appeals

For the Fifth Circuit

20a

cumvention of the Act did not include the authority to

make subject to the disclosure and penalty provisions of

the Act transactions not involving the imposition of a

finance charge, and therefore not covered within the scope

of the Act.

“ The power of an administrative officer or board to

administer a federal statute and to prescribe rules and

regulations to that end is not the power to make law—

for no such power can be delegated by Congress—but the

power to adopt regulations to carry into effect the will

of the Congress as expressed by the statute. A regulation

which does not do this, but operates to create a rule out

of harmony with the statute is a mere nullity” , Manhattan

General Equipment Company v. Commissioner of Internal

Revenue, 297 TT.S. 129, 134, 56 S.Ct. 397, 399, 80 L.Ed. 528

(1935).

We therefore hold that the four installment rule of

Regulation Z constituted an administrative endeavor to

amend the law as enacted by the Congress and to thereby

make the Act reach transactions which the Congress by its

statutory language did not seek or intend to cover by its

enactment. The effect of such an effort comes within the

condemnation of decisions of the Supreme Court. This

condemnation is exemplified by Commissioner of Internal

Revenue v. Acker, 361 U.S. 87, 80 S.Ct. 144, 4 L.Ed.2d

127 (1959), where the Court stated:

“But the section contains nothing to that effect, and

therefore, to uphold this addition to the tax would be

to hold that it may be imposed by regulation, which,

of course, the law does not permit. United States v.

Calamaro, 354 U.S. 351, 359; Koshland v. Helvering,

Opinion of United States Court of Appeals

For the Fifth Circuit

21a

298 U.S. 441, 446, 447; Manhattan Co. v. Commis

sioner, 297 U.S. 129, 134.”

Equally applicable to the above holdings of the United

States is this Court’s opinion in United States v. Marett, 5

Cir., 1963, 325 F.2d 28, 30, 31.

As previously noted, the four installment rule of Regu

lation Z which decrees that those who extend credit and

permit payment in more than four installments have in

cluded within the price which the consumer pays for their

product their cost of extending credit, notwithstanding that

they purport not to levy a finance charge, creates a con

clusive or irrebuttable presumption. Such a presumption

states a rule of substantive law. This is in contrast to a

rebuttable presumption which only states a rule of evi

dence and which the opposing party is entitled to overcome

by proof. The Supreme Court has held that a statute which

creates a conclusive presumption contravenes the Four

teenth Amendment, if enacted by the State Legislature. It

violates the Fifth Amendment if enacted by the Congress.

In Schlesinger v. State of Wisconsin, 270 U.S. 230, 46

S.Ct. 260, 70 L.Ed. 557 (1926), the Supreme Court struck

down as violative of the Fourteenth Amendment a statute

of the State of Wisconsin which provided in effect that

gifts of a decedent estate made within six years of death

were made in contemplation thereof. The Court, 270 U.S.,

at page 239, 46 S.Ct., at page 261, stated:

“The challenged enactment plainly undertakes to

raise a conclusive presumption that all material gifts

within 6 years of death were made in anticipation of it

and to lay a graduated tax upon them without regard

to the actual intent. The presumption is declared to

Opinion of United States Court of Appeals

For the Fifth Circuit

22a

be conclusive and cannot be overcome by evidence. It

is no mere prima facie presumption of fact.”

In Seiner v. Donnan, 285 U.S. 312, 52 S.Ct. 358, 76 L.Ed.

772 (1932), the Court likewise struck down a Congressional

enactment which created a conclusive presumption that

gifts made within two years prior to the death of the donor

were made in contemplation of death, on the ground that the

provision violated the Fifth Amendment of the Constitu

tion. The Court pointed out, 285 U.S., at page 324, 52 S.Ct.,

at page 360, that Congress had the power to create a rebut

table presumption, and stated:

“ But the presumption here created is nest of the

kind. It is made definitely conclusive, incapable of

being overcome by proof of the most positive charac

ter.”

And further the Court stated, 285 U.S., at page 329, 52

S.Ct., at page 362:

“ T his court has held more than once that a statute

creating a presumption which operates to deny a fair

opportunity to rebut it violates the due process clause

of the 14th Amendment.”

It thus appears that Congress itself would have been

without power to create the conclusive presumption which

the Board of Governors seeks to accomplish in the four

installment rule. It is then even more certain that an ad

ministrative agency is without authority to promulgate

such a regulation. Therefore, we conclude that the four

installment rule, as promulgated by an agency of the Fed

eral Government is void because it violates the Fifth

Opinion of United States Court of Appeals

For the Fifth Circuit

23a

Amendment to the Constitution. Although Regulation Z

was designed by the Board of Governors to prevent cir

cumvention of the Act and to facilitate the purposes of the

Act, in its present language it exceeded the authority dele

gated, or which could have been delegated, to the Board

and is, as presently written, void. This necessitates the re

versal of the judgment below.

We further point out that since this transaction carried

with it no finance charge, or cost of credit, it was without

the scope of the Act, leaving aside the matter of Regulation

Z, 15 U.S.C., §1602 (e) and (f).

The judgment of the District Court is reversed and re

manded with directions that the complaint be dismissed.

R eversed and R emanded With Directions.

Opinion of United States Court of Appeals

For the Fifth Circuit

24a

Judgment of Court of Appeals

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

F ob the F if t h Cibcuit

October Term, 1970

No. 71-1150

D. C. Docket No. Civ. 70-559-WM

L eila M ourning , et al.,

Plaintiff s-Appellees,

versus

F am ily P ublications S ervice, I n c .,

Defendant-Appellant.

APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE

SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF FLORIDA

Before C olem an , S im pson and R oney, Circuit Judges.

This cause came on to be beard on the transcript of the

record from the United States District Court for the

Southern District of Florida, and was argued by counsel;

On C onsideration W hereof, It is now here ordered and

adjudged by this Court that the judgment of the said

District Court in this cause be, and the same is hereby,

reversed; and that this cause be, and the same is hereby

25a

Judgment of Court of Appeals

remanded to the said District Court with directions that

the complaint he dismissed.

September 27, 1971

Issued As Mandate: Oct. 19, 1971.

[ S e a l ]

A true copy 12-7-71

Test: E dward W. W adsworth

Clerk, IT. S. Court of Appeals, Fifth Circuit

B y / s/ B arry W. S tirling

Deputy

New Orleans, Louisiana

MEILEN PRESS INC. — N. Y. C. «sjiis>* 219