Hawkins v. North Carolina Dental Society Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the US Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1964

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Hawkins v. North Carolina Dental Society Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the US Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit, 1964. 5152eece-b79a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/7f18270c-831a-4e5e-bd84-ce7e62305255/hawkins-v-north-carolina-dental-society-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari-to-the-us-court-of-appeals-for-the-fourth-circuit. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

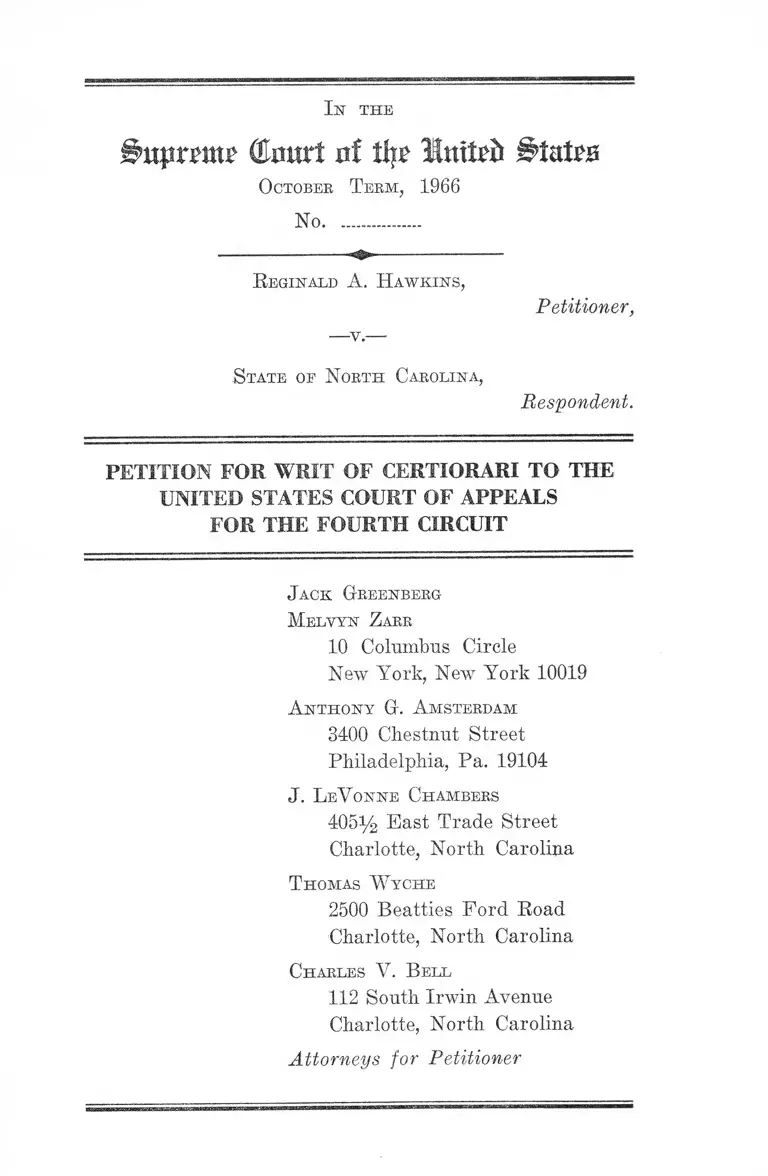

I n t h e

Ihtpratu? ( ta r t at % llmtrfr

October T eem, 1966

No.................

Reginald A. H awkins,

—v.—

Petitioner,

S tate of North Carolina,

Respondent.

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

J ack Greenberg

Melvyn Zarr

10 Columbus Circle

NewT York, New York 10019

A nthony G. Amsterdam

3400 Chestnut Street

Philadelphia, Pa. 19104

J . LeVonne Chambers

405% East Trade Street

Charlotte, North Carolina

T homas YVyche

2500 Beatties Ford Road

Charlotte, North Carolina

Charles V. Bell

112 South Irwin Avenue

Charlotte, North Carolina

Attorneys for Petitioner

I N D E X

Citations to Opinions Below ......................................... 1

Jurisdiction .................................................................... 2

Questions Presented ... ................... 2

Statutes Involved ........................................................... 2

Statement ........................................................................ 6

PAGE

Reasons for Granting the Writ

I. Certiorari Should Be Granted to Reverse the

Court of Appeals’ Holding That Federal Re

moval Jurisdiction May Be Defeated by the

State’s Choice of Charges ............................... 9

II. Certiorari Should Be Granted to Clarify the

Scope of This Court’s Decision in City of

Greenwood v. Peacock, Which Was Extended

by the Court Below So As To Bring It Into

Conflict With Georgia v. Rachel ..................... 10

III. Certiorari Should Be Granted to Reconsider

City of Greenwood v. Peacock Insofar as That

Case Indicates Disallowance of Federal Civil

Rights Removal Jurisdiction of State Criminal

Prosecutions Brought Solely to Harass and

Intimidate Negroes and to Punish Them for,

and Deter Them From, Exercising Their Right

to Vote .............................................................. 13

Conclusion 19

11

PAGE

Appendix I

Opinion of United States Court of Appeals for the

Fourth Circuit........................................................... la

Judgment of United States Court of Appeals for

the Fourth Circuit ................................................ 9a

Appendix II

Opinion of United States District Court for the

Western District of North Carolina ............... ..... 10a

Judgment of United States District Court for the

Western District of North Carolina ..................... 14a

Table of Cases

City of Greenwood v. Peacock, 384 U. S. 808 (1966) —.8,10,

11,12,13,14,15,18

Georgia v. Rachel, 384 U. S. 780 (1966) ..........9,10,11,12,

13,15,16

Harper v. Virginia Board of Elections, 383 U. S. 663

(1966) ......................................................................... 15

Hawkins v. North Carolina Dental Society, 355 F. 2d

718 (4th Cir. 1966) ................................................... 6

Hawkins v. North Carolina State Board of Education,

W. D. N. C., No. 2067 .......................................... 6

Kentucky v. Powers, 201 U. S. 1 (1906) ........... ......... 9

Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U. S. 533 (1964) ....... ............. 14

United States v. Clark, 249 F. Supp. 720 (S. D. Ala.

1965) ..........................................................................- 16

Ill

PAGE

United States v. Raines, 362 U. S. 17 (1960) ............ - 15

United States v. Wood, 295 F. 2d 772 (5th Cir. 1961),

cert. den. 369 U. S. 850 (1962) ............................16,17

Walker v. Georgia, 381 U. S. 355 (1965) ..................... 10

Wilson v. Republic Iron & Steel Co., 257 U. S. 92

(1921) ...............-......................................................... 9

Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U. S. 356 (1886) ................. 14

F ederal S tatutes

R. S. §2004 (1875) ......................................................... 3

Act of September 9, 1957, Pub. L. 85-315, §131, 71 Stat.

637 .................................................................... -11,14,16

Act of May 6, 1960, Pub. L. 86-449, 74 Stat. 9 0 .......... - 14

Act of July 2, 1964, Pub. L. 88-352, §201 (a), 78 Stat.

243 .......................................-.................................... 10,14

Act of July 2, 1964, Pub. L. 88-352, §203, 78 Stat.

244 .... ................................................................. 10,14,17

Act of August 6, 1965, Pub. L. 89-110, §11 (b), 79 Stat.

443 ............................................. -.........................11,14,17

28 U. S. C. §1254(1) (1964) .......................-................. 2

28 U. S. C. §1443(1) (1964) ................................2,3,11,13

42 U. S. C. §1971(a)(l) (1964) ........... ...................... 2,3,11

42 U. S. C. §1971(b) (1964) .....................2,3,11,12,16,17

42 U. S. C. §1973i(b) (Supp. I, 1965) ..............2, 3, 4,11,12

42 U. S. C. §2000a(a) (1964) ....... ........................... 4,10,11

42 U. S. C. §2000a-2 (1964) ..........................5,10,11,12

S tate S tatutes

N. C. Gen. Stat. §163-196(3) ....................................... 6

N. C. Gen. Stat. §163-197(1) ....................................... 6

I n th e

CUnurt of Iff? Intfrii §miisB

October T erm, 1966

No................

Reginald A. H awkins,

Petitioner,

State of North Carolina,

Respondent.

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

Petitioner prays that a writ of certiorari issue to review

the judgment of the United States Court of Appeals for the

Fourth Circuit entered in this case on August 16, 1966.

Citations to Opinions Below

The per curiam opinion and judgment of the Court of

Appeals and Judge Sobeloff’s special concurrence are as

yet unreported and are set forth in Appendix I, hereto,

pp. la-9a, infra.

The remand order and supporting opinion of the United

States District Court for the Western District of North

Carolina, entered May 15, 1965 and affirmed by the Court

of Appeals, are as yet unreported and are set forth in

Appendix II, hereto, pp. 10a-14a, infra.

2

Jurisdiction

The judgment of the Court of Appeals was entered

August 16, 1966 (Appendix I, p. 9a). Jurisdiction of this

Court is invoked pursuant to 28 U. S. C. §1254(1) (1964).

Questions Presented

1. Did the Court of Appeals err in accepting, without

an evidentiary hearing below, the charges against petitioner

rather than the allegations of his petition for removal as

the basis for testing petitioner’s claim to civil rights re

moval jurisdiction over his state criminal prosecution?

2. Did the Court of Appeals err in disallowing federal

civil rights removal jurisdiction of petitioner’s state

criminal prosecution where that prosecution was brought

(a) on account of acts directly involved in the process of

Negro voting registration, and (b) solely to harass peti

tioner and to punish him and other Negroes for, and deter

them from, registering to vote?

Statutes Involved

A. This case involves the construction of 28 U. S. C.

§1443(1) (1964) as it pertains to the protection afforded

rights conferred by 42 U. S. C. §§1971(a)(1), (b) (1964),

1973i(b) (Supp. I, 1965), the latter section being Sec. 11(b)

of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, 79 Stat. 443.

In relevant part, these statutes provide:

1. 28 U. S. C. §1443(1) (1964):

§1443. Civil rights cases

Any of the following civil actions or criminal prosecu

tions, commenced in a State Court may be removed

by the defendant to the district court of the United

States for the district and division embracing the place

wherein it is pending :

(1) Against any person who is denied or cannot

enforce in the courts of such State a right under any

law providing for the equal civil rights of citizens

of the United States, or of all persons within the juris

diction thereof; . . .

2. 42 U. S. C. §1971(a) (1) (1964) (R. S. §2004 (1875):

§1971 . . .

(a) (1) All citizens of the United States who are

otherwise qualified by law to vote at any election by

the people in any State, Territory, district, county,

city, parish, township, school district, municipality, or

other territorial subdivision, shall be entitled and al

lowed to vote at all such elections, without distinction of

race, color, or previous condition of servitude; any

constitution, law, custom, usage, or regulation of any

State or Territory, or by or under its authority, to the

contrary notwithstanding.

3. 42 U. S. C. §1971 (b) (1964) (Sec. 131 of the Civil

Rights Act of 1957, 71 Stat. 637):

§1971 . . . (b) Intimidation, threats, or coercion

No person, whether acting under color of law or

otherwise, shall intimidate, threaten, coerce, or at

4

tempt to intimidate, threaten, or coerce any other per

son for the purpose of interfering with the right of

such other person to vote or to vote as he may choose,

or of causing such other person to vote for, or not to

vote for, any candidate for the office of President, Vice

President, presidential elector, Member of the Senate,

or Member of the House of Representatives, Delegates

or Commissioners from the Territories or possessions,

at any general, special, or primary election held solely

or in part for the purpose of selecting or electing any

such candidate.

4. 42 U. S. C. §1973 i (b) (Supp. I, 1965) (Sec. 11(b) of

the Voting Rights Act of 1965, 79 Stat. 443):

§1973 i . . . (b) Intimidation, threats, or coercion

No person, whether acting under color of law or

otherwise, shall intimidate, threaten, or coerce, or at

tempt to intimidate, threaten, or coerce any person

for voting or attempting to vote, or intimidate,

threaten, or coerce, or attempt to intimidate, threaten,

or coerce any person for urging or aiding any person

to vote or attempt to vote, or intimidate, threaten, or

coerce any person for exercising any powers or duties

under section 1973a(a), 1973d, 1973f, 1973g, 1973h, or

1973j(e) of this title.

B. In this petition, important reference will also be

made to the following statutes:

1. 42 U. S. C. §2000a (a) (1964) (Sec. 201(a) of the

Civil Rights Act of 1964, 78 Stat. 243):

§2000a. Prohibition against discrimination or segrega

tion in places of public accommodation—Equal

access

5

(a) All persons shall be entitled to the full and

equal enjoyment of the goods, services, facilities,

privileges, advantages, and accommodations of any

place of public accommodation, as defined in this sec

tion, without discrimination or segregation on the

ground of race, color, religion, or national origin.

2. 42 U. S. C. §2000a-2 (1964) (Sec. 203 of the Civil

Eights Act of 1964, 78 Stat. 244):

§2000a-2. Prohibition against deprivation of, inter

ference with, and punishment for exercising

rights and privileges secured by section

2000a or 2000a~l of this title

No person shall (a) withhold, deny, or attempt to

withhold or deny, or deprive or attempt to deprive, any

person of any right or privilege secured by section

2000a or 2000a-l of this title, or (b) intimidate, threaten,

or coerce, or attempt to intimidate, threaten, or coerce

any person with the purpose of interfering with any

right or privilege secured by section 2000a or 2000a-l

of this title, or (c) punish or attempt to punish any

person for exercising or attempting to exercise any

right or privilege secured by section 2000a or 2000a-l

of this title.

6

Statement

November 12, 1964, petitioner Reginald A. Hawkins, a

Negro dentist active in civil rights work,1 filed in the

United States District Court for the Western District of

North Carolina a petition for removal of a criminal prose

cution from the Superior Court of Mecklenburg County,

North Carolina (R.I., 20a.-25a).2 The criminal proceedings

against petitioner involved charges of interfering with a

special registration commissioner in the performance of

her duties, an alleged violation of N. C. Gen. Stat. §163-

196(3), and of fraudulently procuring the registration of

certain persons not qualified to vote under North Carolina

law, an alleged violation of N. C. Gen. Stat. §163-197(1)

(R.I., 23a).

Petitioner’s removal petition invoked 28 U. S. C. §1443

(1964), the civil rights removal statute. It alleged that

the prosecution against him was maintained for the sole

purpose and effect of harassing him and punishing him

for, and deterring him and other Negroes from, exercising

their right to vote (R.I., 25a), and that the conduct with

which he was charged was protected by the First, Four

teenth and Fifteenth Amendments and by federal civil

rights statutes, including 42 U. S. C. §1971 (R.I., 24a-25a).3

1 See, e.g., Hawkins v. North Carolina Dental Society, 355 F. 2d

718 (4th Cir. 1966) ; Hawkins v. North Carolina State Board of

Education, W. D. N. C., No. 2067 (decided April 4, 1966; three-

judge court).

2 An amended petition was filed on April 26, 1965 (R. I., 26a).

3 Petitioner had earlier moved the Superior Court of Mecklen

burg County to quash the indictments against him on the grounds,

inter alia, that the statutes upon which the indictments were based

were unconstitutionally vague and thus repugnant to the due

7

Specifically, it alleged that on the night of April 8, 1964,

in his capacity as president of the Mecklenburg Organiza

tion on Political Affairs, a civic affairs association, peti

tioner engaged in a voter registration project to encourage

Negroes in the community to register and vote in the forth

coming federal and state elections (R.I., 20a). Petitioner

visited the homes of prospective voters, determined

whether they could read and write and were otherwise

eligible for registration; encouraged those persons who

were qualified to register to do so; and assisted them by

providing transportation to the local high school which

was nsed as a place of registration (R.I., 20a-21a). Upon

petitioner’s arrival at the place of registration, there were

many applicants waiting to be registered (R.I., 21a). The

special registration commissioner, assertedly unfamiliar

with the registration procedure, requested petitioner to

assist her in registering the prospective Negro voters

(R.I., 21a). Petitioner suggested, inter alia, that the oath

be administered collectively rather than individually; the

registration commissioner accepted this suggestion, ad

ministered the oath and attested to the qualifications of

the applicants (R.I., 20a-21a). These activities led to the

indictments against petitioner (R.I., 21a-23a).

On April 26, 1965, the State filed a motion to remand,

challenging the sufficiency of the petition to invoke fed

process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment; that the indict

ments were based upon alleged violations of statutes which, on

their face and as applied to his conduct, infringed federal statutory

and constitutional voting rights and the North Carolina Constitu

tion; and that application of the literacy test referred to in the

indictments was forbidden by 42 U. S. C. §1971 (1964), depriving

petitioner of his rights under that statute (R.I., 7a-lla). This

motion was denied (E.I., 12a-19a). After removal of the case,

petitioner filed in the District Court a motion to dismiss based on

substantially identical grounds (R.I., 27a-29a).

8

eral removal jurisdiction under 28 U. S. C. §1443 (1964)

(R.I., 30a-31a).

The district court held no evidentiary hearing, but heard

oral argument on the question of the sufficiency in law of

the removal petition. On May 15, 1965, the district court

remanded the case and a timely appeal was taken (R.I.,

32a-37a).

On August 16, 1966, the United States Court of Appeals

for the Fourth Circuit, in a per curiam opinion by Judges

Haynsworth and Bryan, affirmed the district court’s remand

order. Two grounds for affirmance were cited (Appendix

I, p. 2a):

1. The specific charges of the indictment contradicted

the allegations of the removal petition.

2. This Court, in City of Greenwood v. Peacock, 384

U. S. 808 (1966), had disallowed removal to federal court

of a state criminal prosecution brought to harass the re

moval petitioner and to punish him and other Negroes for,

and deter them from, registering to vote.

As to the first ground of decision, Judge Sobeloff dis

sented (Appendix I, pp. 5a, 8a). As to the second ground

of decision, Judge Sobeloff concurred, stating that City

of Greenwood v. Peacock, 384 U. S. 808 (1966), precluded

him from holding that voting harassment prosecutions

were removable to federal court (Appendix I, pp. 3a-8a).

9

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE WRIT

I.

Certiorari Should Be Granted to Reverse the Court of

Appeals’ Holding That Federal Removal Jurisdiction

May Be Defeated by the State’s Choice of Charges.

The majority of the Court of Appeals apparently took

the view that civil rights removal should be disallowed

whenever the factual allegations in a petition for removal

are contradicted by the criminal charges against the peti

tioner. No reasoning or authority was assigned for this

proposition, which sub silentio overturns accepted practice

in the federal courts.4 Judge Sobeloff disagreed, saying:

“The test of removability is the content of the petition,

not the characterization given the conduct in question by

the prosecutor” (Appendix I, p. 8a).

The majority’s test threatens the right to removal given

by Georgia v. Rachel, 384 U. S. 780 (1966). This Court,

in Rachel, did not suggest that removal of state prosecu

tions for acts protected by Title II of the Civil Rights Act

of 1964 was limited to trespass prosecutions. So to limit

Rachel would invite the State to defeat removal merely

by charging persons sitting-in at protected public accom

modations with, for example, breach of the peace instead

4 I t is well settled that, in dealing with removal petitions, whether

in civil rights cases or others, the factual allegations of the petition,

absent an evidentiary hearing, are to be taken as true. Kentucky

v. Powers, 201 U. S. 1, 33-35 (1906); Wilson v. Republic Iron &

Steel Co., 257 U. S. 92, 97-98 (1921).

10

of trespass.5 The present decision by a majority of the

Fourth Circuit constitutes such an invitation. To preserve

even the narrow right of removal allowed by Rachel, it is

vital that this Court grant certiorari to review this wholly

frustrating innovation in removal procedure.6

II.

Certiorari Should Be Granted to Clarify the Scope of

This Court’s Decision in City of Greenwood v. Peacock,

Which Was Extended by the Court Below So As To

Bring It Into Conflict With Georgia v. Rachel.

Section 201(a) of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 78 Stat.

243, 42 U. S. C. §2000a(a) (1964), pp. 4-5 supra, gives all

persons a right of service without racial discrimination

in places of public accommodation. Section 203 of the Act,

78 Stat. 244, 42 U. S. C. §2000a-2 (1964), p. 5, supra,

assures the practical realization of that right by providing

that no person shall “intimidate, threaten or coerce, or

attempt to intimidate, threaten, or coerce” or “punish or

attempt to punish” another in the exercise of the substan

tive rights given by section 2QOOa(a). Similarly, R. S.

5 The danger posed by such an invitation is not merely specu

lative. The State of Georgia is now charging persons who sought

to enjoy non-discriminatory treatment in the place of public ac

commodation involved in Rachel with crimes other than trespass.

For example, those persons whose trespass convictions were re

versed by this Court in Walker v. Georgia, 381 U. S. 355 (1965),

are now being prosecuted for the same activities for crimes other

than trespass. These prosecutions have been removed to the United

States District Court for the Northern District of Georgia, Cr.

Nos. 24701 and 24705.

6 Because the Fourth Circuit is one of the two federal circuits

comprising the substantial bulk of the southern States, the present

decision represents a critical obstruction of the right given in

Rachel, even if it is not persuasive to the other courts of appeals.

11

§2004 (1875), 42 U. 8. C. §197L(a)(l) (1964), p. 3, supra,

gives all persons a right to register and vote without

racial discrimination. Section 131 of the Civil Eights Act

of 1957, 71 Stat. 637, 42 TJ. S. C. §1971(b) (1964), pp. 3-4,

supra, assures the practical realization of the latter right

by providing that no person shall “intimidate, threaten, or

coerce, or attempt to intimidate, threaten or coerce”

another in the exercise of voting rights. And section 11(b)

of the Voting Eights Act of 1965, 79 Stat. 443, 42 U. S. C.

§1973i(b) (Supp. I, 1965), p. 4, supra, further assures

protection of the voting right by providing that no person

shall “intimidate, threaten, or coerce, or attempt to intimi

date, threaten, or coerce any person for voting or attempt

ing to vote or . . . for urging or aiding any person to

vote or attempt to vote.”

In Georgia v. Rachel, supra, this Court sustained re

moval under 28 U. S. C. §1443(1) (1964) of state criminal

trespass prosecutions brought against Negroes for re

fusing to leave places of public accommodation in which

they were given a right of service without racial discrimina

tion by §2000a. §2000a(a) was read as giving persons

seeking restaurant service a right to insist upon such

service without discrimination, and §2000a-2 was read as

giving a concomitant right not to be prosecuted for that

insistence.

In City of Greenwood v. Peacock, supra, this Court dis

allowed removal of prosecutions against civil rights demon

strators based upon their conduct in protesting the denial

to Negroes of rights to register and vote given by §1971 (a)

(1). Section 1971(a)(1) was read as not extending to per

sons a right to protest racial discrimination in voting regis

tration, as distinguished from a right to register, or to

12

assist others in registering, to vote without racial discrimi

nation. Thus, §§1971 (b) and 1973i(b), which protect those

persons directly engaging in the exercise of voting rights in

the same way that §2000a-2 protects sit-ins, that is, against

the coercive, intimidating and punishing effects of state

prosecution for protected activity, were not called into

play.

The only other possible distinction between Rachel and

Peacock—namely, that §2000a-2 includes the word “pun

ish” together with “intimidate, threaten or coerce” within

its prohibition, while §§1971(b) and 1973i(b) do not—is so

palpably insubstantial as to trivialize the significance of

these important pieces of federal civil rights legislation.

Yet, only this second and wholly impermissible distinction

will support the decision below affirming remand of peti

tioner’s case. For Dr. Hawkins, unlike the demonstrators

in Peacock, was directly engaged in the process of regis

tering prospective Negro voters, and the conduct for which

he is prosecuted comes flush within the language of

§1973i(b): “aiding any person to vote or attempt to vote.”

His is clearly conduct for which one of the “specific pro

visions of a federal pre-emptive civil rights law”—

§1973i(b)—“confers immunity from state prosecution.”

Peacock, supra, at 826, 827. The decision of the Court of

Appeals extending Peacock to deny removal in his case,

therefore, calls imperatively for review by this Court if

Rachel is not to be reduced to trifling and rationally un-

supportable dimensions.

13

III.

Certiorari Should Be Granted to Reconsider City of

Greenwood v. Peacock Insofar as That Case Indicates

Disallowance of Federal Civil Rights Removal Jurisdic

tion of State Criminal Prosecutions Brought Solely to

Harass and Intimidate Negroes and to Punish Them for,

and Deter Them From, Exercising Their Right to Vote.

In authorizing removal to a federal court, under 28

U. .S. C. §1443(1) (1964), of state criminal charges for con

duct immunized from prosecution by federal laws providing

for equal civil rights, this Court in Georgia v. Rachel, supra,

recognized the practical effect of such charges. The mere

pendency of state prosecutions, without more, was properly

seen to defeat the meaningful exercise of federally pro

tected rights because, regardless of their outcome, these

prosecutions serve to punish the defendants for, and in

timidate and deter them from, exercising their federal

rights. Therefore, a removal petitioner was held to be

“denied” his federal rights by prosecution in the state

court system whenever a federal law providing for equal

civil rights immunized his conduct from prosecution.

This Court said (384 U. S. at 805):

It is no answer in these circumstances that the de

fendants might eventually prevail in the state court.

The burden of having to defend the prosecutions is it

self the denial of a right explicitly conferred by the

Civil Rights Act of 1964 as construed in Hamm v. City

of Rock Hill [379 U. S. 306],

The federal law successfully relied upon by the removal

petitioners in Rachel was Title II of the Civil Rights Act

14

of 1964, pp. 4-5, supra, protecting the right of equal access

to places of public accommodation. Unless Congress has de

termined that voting rights are less worthy or needful of

federal protection than the right to equal public accom

modations, or unless it has failed to protect the former

rights by similarly “specific provisions of a federal pre

emptive civil rights law,” City of Greenwood v. Peacock,

supra, 384 U. S. at 826, then state prosecutions brought

solely to harass and intimidate Negroes and to punish them

for, and deter them from, exercising their right to vote

should likewise be removable to federal court.

Neither Congress nor this Court has relegated voting

rights to such a subordinate position. In the Civil Rights

Acts of 1957,7 I960,8 1964,9 and 1965,10 Congress has en

acted a comprehensive scheme for the protection of voting

rights, a legislative scheme certainly no less protective than

Title II of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Analysis of this

scheme renders it “difficult to conceive that Congress in

tended to place voting rights guarantees on a lower plane

of protection than the right to equal public accommoda

tions” (Opinion of Judge Sobeloff below, Appendix I, p.

8a). And this Court has long recognized that the right

to vote is a fundamental right, “because preservative of all

rights” (Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U. S. 356, 370 (1886)).

In Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U. S. 533, 561-62 (1964), the

Court said: “Undoubtedly, the right of suffrage is a funda

mental matter in a free and democratic society. Especially

since the right to exercise the franchise in a free and unim

7 Act of September 9,1957, Pub. L. 85-315, 71 Stat. 637.

8 Act of May 6,1960, Pub. L. 86-449, 74 Stat. 90.

9 Act of July 2,1964, Pub. L. 88-352, 78 Stat. 241.

10 Act of August 6,1965, Pub. L. 89-110, 79 Stat. 437.

15

paired manner is preservative of other basic civil and

political rights, any alleged infringement of the right of

citizens to vote must be carefully and meticulously scruti

nized.” 11

If City of Greenwood v. Peacock, supra, has disallowed

federal civil rights removal jurisdiction as a protection of

federal voting rights, it has disallowed too much. In Part

II, supra, of its petition for certiorari, petitioner has de

scribed the two possible grounds of distinction between

Peacock and Rachel. One, turning on the adventitious in

sertion of the Avord “punish” in Title II of the Civil Rights

Act of 1964, is plainly less plausible than the other. But

both are equally neglectful of profound and pervasive fed

eral constitutional and statutory commitments to effective

protection of the American citizen’s right to the franchise

without racial discrimination.

Peacock was a victim of diffuse presentation in this

Court. Confronted by a welter of factual situations and by

a statute having an obscure text, a muddy history, a broad

range of alternative plausible readings and no authoritative

construction by this Court for 60 years, presentation was

necessarily dispersed and unfocused. The result was an

opinion by the Court which cut too broadly, ignoring the

special position of federal voting rights in our federal sys

tem and the exhaustive scheme of congressional legislation

designed to protect those rights.

With all deference, it is submitted the language and in

tent of federal voting legislation12 plainly enable petitioner

11 See also, Harper v. Virginia Board of Elections, 383 U. S. 663,

667-68 (1966) ; United States v. Baines, 362 U. S. 17, 27 (1960).

12 The Voting Rights Act of 1965 Avas not enacted until peti

tioner’s case was on appeal. HoAvever, in order to promote effi-

16

and others subjected to prosecutions which repress Negro

voting registration activity to meet the test of removal

announced in Georgia v. Rachel, supra. Title 42 U. S. C.

§1971 (b) (1964),13 pp. 3-4, supra, provides an ample declara

tion of congressional intention to immunize from state

prosecution a person against whom state criminal charges

are brought with the sole purpose and effect of harassing

and intimidating him and other Negroes and punishing

them for, and deterring them from, exercising their right to

vote. The United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth

Circuit has so held, and its reasoning and authority are

persuasive. United States v. Wood, 295 F. 2d t72 (5th Cir.

1961), cert. den. 369 U. S. 850 (1962).

In Wood, the Fifth Circuit ordered a federal injunction

against the state prosecution of John Hardy, a Negro

voter registration worker in Walthall County, Mississippi,

for peacefully attempting to encourage Negro citizens to

attempt to register to vote. Hardy had been arrested, with

out cause, for breach of the peace. The court held that the

prosecution of Hardy, regardless of its outcome, would

effectively intimidate Negroes in the exercise of their right

to vote in violation of 42 U. S. C. §1971 (b) (1964).“

As a matter of language, 42 U. S. C. §1971(b) (1964), is

broad enough to cover the case of official intimidation

eiency of judicial administration, its impact upon petitioner’s case

should be evaluated here, since not to do so would compel peti

tioner to file a second petition for removal, were removal under

the other voting rights acts disallowed. See Georgia- v. Rachel,

supra.

“ Enacted in the Civil Eights Act of 1957, §131, 71 Stat. 637.

14 Wood was followed in United States v. Clark, 249 F. Supp.

720 (S. D. Ala. 1965) (three-judge court).

17

through abuse of the state criminal process. “If, as alleged

in the removal petition, prosecution against persons as

sisting in a Negro voter registration drive is racially mo

tivated, this is an ‘attempt to intimidate, threaten, or

coerce’ Negroes in the exercise of their right to vote” (Opin

ion of Judge Sobeloff, Appendix I, p. 6a). Moreover, the

legislative history of 42 U. S. C. §1971 (b) (1964), canvassed

in Wood, 295 F. 2d at 781-82, compels the conclusion “that

Congress contemplated just such activity as is here alleged

—where the state criminal processes are used as instru

ments for the deprivation of constitutional rights” (295

F. 2d 781).

Sec. 11(b) of the Voting Eights Act of 1965, p. 4,

supra, is of particular significance here for two reasons.

First, it has signified congressional acceptance of the

Wood construction of §1971 (b) in that it specifically pro

scribes any “attempt to intimidate, threaten, or coerce any

person for urging or aiding any person to vote or attempt

to vote.” This should set to rest whatever doubt §1971 (b)

may have left that petitioner, himself previously regis

tered to vote, merits the protection of federal voting legis

lation in aiding others to do so. Second, it has retained the

“intimidate, threaten or coerce” formula of §1971(b), ap

parently deeming it sufficient to cover the case of official in

timidation through harassment prosecutions—a case un

doubtedly recognized by the 89th Congress as an important

means of repression of persons aiding other persons to

register to vote. Thus it can be seen that there is no

magic to the language “punish or attempt to punish” of Sec.

203(c) of the Civil Eights Act of 1964 which qualifies it

alone to combat harassment prosecutions violative of im

portant federal rights.

18

The need for a protective removal jurisdiction over vot

ing intimidation cases has been sufficiently stated by Judge

Sobeloff (Appendix I, p. 6a):

If Georgia is forbidden to prosecute sit-ins under

the public accommodations provisions of the 1964 Act,

North Carolina would likewise seem to be forbidden to

prosecute Dr. Hawkins for assisting in the exercise of

[voting] rights.

* * * * *

It is immaterial that Dr. Hawkins himself was not

seeking to register; it is enough that he was assisting

other Negroes to do so. If the law’s protection cannot

be invoked by the more intelligent and better-educated

Negro who furnishes leadership and guidance to others

of his race, the purpose of the Voting Eights Act will

be severely impaired.

Negroes’ rights are as effectively frustrated by prose

cutions arising out of the attempt to exercise voting

rights as by prosecutions growing out of the assertion

of the right to equal accommodations. The use of the

criminal process for the purposes of intimidation, I

submit, would logically be proscribed in both cases.

Permitting appellant to prove in a federal evidentiary

hearing that the state prosecution against him is nothing

more than an attempt to stifle the exercise of the right to

vote by Negroes in Mecklenburg County, North Carolina

will not “work a wholesale dislocation of the historic re

lationship between the state and federal courts in the

administration of the criminal law” (Peacock, supra, 384

U. S. at 831). Rather, it will vindicate respect for that law.

19

CONCLUSION

The writ of certiorari should be granted to review and

reverse the judgment of the Court of Appeals.

Respectfully submitted,

J ack Greenberg

Melvyn Zarr

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

A nthony G. A msterdam

3400 Chestnut Street

Philadelphia, Pa. 19104

J. L eV onne Chambers

405% East Trade Street

Charlotte, North Carolina

Thomas W yche

2500 Beatties Ford Road

Charlotte, North Carolina

Charles V . B ell

112 South Irwin Avenue

Charlotte, North Carolina

Attorneys for Petitioner

A P P E N D I C E S

APPENDIX I

Opinion of United States Court of Appeals

for the Fourth Circuit

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

F oe, the F ourth Circuit

No. 10,062

S tate of N orth Carolina,

versus

Appellee,

R eginald A. H aw kins,

Appellant.

APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE

WESTERN DISTRICT OF NORTH CAROLINA, AT CHARLOTTE

J . BRAXTON CRAVEN, JR ., DISTRICT JUDGE

(Argued April 7, 1966 Decided August 16, 1966.)

B e f o r e :

H aynsworth, Chief Judge, and

S obeloff and B ryan, Circuit Judges.

P er Curiam :

Dr. Hawkins, a dentist, was indicted by a state grand

jury charged with unlawful interference with a voting regis

tration commissioner in the discharge of her duties and with

the unlawful procurement of the registration of four un-

2a

qualified voters. He undertook to remove the prosecution to

the District Court. We affirm the order of remand.

In the removal petition, it is alleged that he merely ren

dered requested assistance to the commissioner, that he

made no representations about the qualifications of any

voter, that the state’s purpose was to harass and deter

him, and, in conclusionary language, that he could not

obtain a fair trial in North Carolina’s courts. His allega

tions as to what transpired on the particular occasion are

in contradiction of the specific charges of the indictment.

It is clear that this is not a case removable under 28

u. S. C. A. § 1443. Compare City of Greenwood v. Peacock,

384 H. S. 808, with State of Georgia v. Rachel, 384 U. S.

780; See Baines v. City of Danville, 384 U. S. 890; affirming

Baines v. City of Danville, 4 Cir., 357 F. 2d 756; and Wallace

v. Virginia, 384 H. S. 891, affirming Commonwealth of Vir

ginia v. Wallace, 4 Cir., 357 F. 2d 105.

Affirmed.

S obeloff, Circuit Judge, concurring specially:

Appellant, Dr. Reginald A. Hawkins, is a Negro dentist

practicing in Charlotte, North Carolina, who has engaged

in civil rights activities. E.g., see Hawkins v. North Caro

lina Dental Society, 355 F. 2d 718 (4th Cir. 1966). On

September 7, 1964, he was indicted by the Grand Jury of

Mecklenburg County, North Carolina, on charges of un

lawfully interfering with a special voting registration com

missioner, North Carolina General Statutes § 163-196(3),

and unlawfully and fraudulently procuring the registration

of certain persons not qualified to vote under North Caro

lina law, in violation of § 163-197 (h) of the statute. The

prosecutions were removed to the District Court for the

3a

Western District of North Carolina, pursuant to 28 U. S.

C. A. §§ 1443 et seq., but that court remanded to the state

court, and this appeal followed.

The removal petition recites inter alia, that on the night

of April 8,1964, in his capacity as president of the Mecklen

burg Organization on Political Affairs, Dr. Hawkins was

engaged in a voters’ registration campaign to encourage

Negroes in the community to register and vote in the forth

coming federal and state elections. Petitioner, and pre

sumably others participating in the drive, visited the homes

of prospective voters, determined whether they could read

and write and were otherwise eligible for registration, en

couraged qualified persons to register, and assisted them

by providing transportation to the local high school which

was used as a place of registration.

On petitioner’s arrival at the place of registration, there

were a large number of applicants waiting to be registered.

The special registration commissioner, due to her asserted

unfamiliarity with the procedure, requested Dr. Hawkins

to assist in registering the prospective Negro voters. Dr.

Hawkins suggested, among other things, that the oath be

administered en masse rather than individually, and then

the registration commissioner herself attested to the quali

fications of the applicants and signed their applications.

The indictments mentioned above allegedly grew out of

these activities.

In Rachel v. Georgia,----- U. S .------ , 34 U. S. L. Week

4563 (1966), the Supreme Court authorized removal to the

federal court of prosecutions against Negro defendants

charged under a local trespass statute with failing to obey

an order to leave a restaurant. Adhering generally to the

interpretation of removal enunciated in the Rives-Powers

4a

line of decisions,1 the Court nevertheless held that removal

was in order if a basis could be shown for a “firm predic

tion that the defendant would be ‘denied or cannot enforce’

the specified federal rights in the state court.” Id. a t ----- ;

34 U. S. L. Week at 4570. That basis was found in the

public accommodations section of the Civil Rights Act of

1964, which grants all persons, regardless of their race,

a right to be served in places of public accommodation, and

further prohibits the state from punishing or attempting

to punish any person for exercising those rights. Civil

Rights Act of 1964, § 203(c). 42 U. S. C. A. § 2000a-2

(1964). The Court went on to hold that:

“Hence, if as alleged in the present removal petition,

the defendants were asked to leave solely for racial

reasons, then the mere pendency of the prosecutions

enables the federal court to make the clear prediction

that the defendants will be ‘denied or cannot enforce in

the courts of [the] state’ the right to be free of any

‘attempt to punish’ them for protected activity.” Ibid.

at p .----- .

Since the removal petition in Rachel had been remanded

by the District Court to the state court without a hearing,

the Supreme Court ordered the District Court to conduct

a hearing to determine the truth of the petitioners’ allega

tions that they had been ordered to leave the restaurant

solely for racial reasons. If that should be the finding of

the District Court, said the Supreme Court, then “it will

be apparent that the conduct of the defendants is ‘im

1 See Kentucky v. Powers, 201 U. S. 1 (1906); Rives v. Virginia,

100 U. S. 303 (1879) ; Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U. S. 313

(1879) ; Rachel v. Georgia, supra a t ----- , 34 U. S. L. Week at

4565, n. 5.

5a

munized from prosecution’ in any court,” and the removal

petition should be allowed. Id. a t ----- ; 34 U. S. L. Week at

4571.

Rachel cannot fairly be construed to mean that removal

may be had only where the facts precisely duplicate those

presented there, he.: where a Negro is indicted under a

state criminal statute for refusing to leave the premises

of a place of public accommodation. The essence of the

Rachel decision is that the federal court is empowered to

determine the narrow question whether the activities giving

rise to a charge in the state courts constitute conduct pro

tected by a federal statute that provides for equal civil

rights and prohibits the state from prosecuting persons

engaged in that conduct.

The court’s opinion in the present case states that Dr.

Hawkins’ “allegations as to what transpired on the par

ticular occasion are in contradiction of the specific charges

of the indictment,” and suggests that this is the ground for

rejecting removal. The Supreme Court’s opinion in Rachel

makes clear, however, that conflict between the allegations

in the removal petition and the criminal indictment is not

ground for denying removal, provided that (1) the petition

alleges facts which, if true, establish that the conduct is

protected under a federal statute guaranteeing equal civil

rights, and (2) there is a federal statutory prohibition

against prosecution in the state courts for such conduct.

Establishment of both propositions will impel the conclu

sion that the petitioner “is denied or cannot enforce” his

rights in the state court, justifying removal.

Here, as in the Rachel sit-in cases, Dr. Hawkins was

engaged in assisting Negroes in the exercise of equal civil

rights guaranteed by a federal statute, namely the Voting

Eights Act of 1964. Section 1971(b) of that statute, orig

6a

inally a part of the Civil Eights Act of 1957, specifically

provides that:

“No person, whether acting under color of law or other

wise, shall intimidate, threaten, coerce, or attempt to

intimidate, threaten or coerce any other person for the

purpose of interfering with the right of such other

person to vote * * * 42 TJ. S. C. A. § 1971(b) (1964).

(Emphasis added.)

If, as alleged in the removal petition, prosecution against

persons assisting in a Negro voter registration drive is

racially motivated, this is an “attempt to intimidate,

threaten or coerce” Negroes in the exercise of their right

to vote. If Georgia is forbidden to prosecute sit-ins under

the public accommodations provisions of the 1964 Act,2

North Carolina would likewise seem to be forbidden to

prosecute Dr. Hawkins for assisting in the exercise of

rights under the voting provisions of the same act.3 Section

203(c) of the public accommodations portion of the Civil

Rights Act of 19644—the basis for permitting removal in

Rachel—provides that “No person shall * # * (c) punish

or attempt to punish any person for exercising or attempt-

~~*Hamm v. City of Eock Hill, 379 U. S. 306 (1965).

3 It is immaterial that Dr. Hawkins himself was not seeking to

register; it is enough that he was assisting other Negroes to do so.

If the law’s protection cannot be invoked by the more intelligent

and better-educated Negro who furnishes leadership and guidance

to others of his race, the purpose of the Voting Eights Act will be

severely impaired.

Negroes’ rights are as effectively frustrated by prosecutions aris

ing out of the attempt to exercise voting rights as by prosecutions

growing out of the assertion of the right to equal accommodations.

The use of the criminal process for the purposes of intimidation,

I submit, would logically be proscribed in both cases.

4 42 U. S. C. A. § 2000a-2 (1964).

7a

ing to exercise any right or privilege secured by section 201

or 202 [equal access to public accommodations].” 5 (Em

phasis added.) Section 1971(b) of the voting rights pro

visions employs a more general prohibition against any

attempted intimidation, threats, or coercion by persons “act

ing under color of law or otherwise.” 6 Literal comparison

of the two provisions suggests that § 1971(b) is a more,

not less, sweeping prohibition of official acts of harassment

against equal civil rights than the limited proscription of

§ 203(c), since “attempts to punish” are only one means

of coercing, threatening, or intimidating.7

5 Section 201 provides in its entirety:

“No person shall (a) withhold, deny, or attempt to withhold

or deny, or deprive or attempt to deprive, any person of any

right or privilege secured by section 201 or 202, or

(b) intimidate, threaten, or coerce any person with the pur

pose of interfering with any right or privilege secured by

section 201 or 202, or

(e) punish or attempt to punish any person for exercising

or attempting to exercise any right or privilege secured by

section 201 or 202.” 42 U. S. C. A. § 2000a-2 (1964).

6 “No person, whether acting under color of law or otherwise,

shall intimidate, threaten, coerce, or attempt to intimidate, threaten

or coerce any other person for the purpose of interfering with the

right of such other person to vote * * 42 U. S. C. A. § 1971(b)

(1964). (Emphasis added.)

7 Section 203(6) prohibits acts of intimidation, threats, and

coercion, but does not contain the key words “acting under color

of authority of law” -which are found in the comparable provision

of § 1971. § 203(c) cures this omission by specifying that no one

shall “punish or attempt to punish” any person for exercising or

attempting to exercise his rights. Having eliminated acts of state

officials from part (b) of § 203, they are thus in effect restored by

paragraph (c).

In other words, § 1971(b) of the voting rights provisions seems

to express in different language the principle contained in § 203(c)

of the public accommodations clauses—that the states, acting

through state officials are forbidden to employ any form of at

tempted intimidation, coercion, or threats, including “attempts to

punish.” Thus, § 1971(b) performs the same function as § 203(c),

8a

However, in Peacock v. City of Greenwood, —— IJ. S.

----- , 34 U. S. L. Week 4572 (1966), where the voting rights

provisions of § 1971 were invoked in support of a removal

claim, the Supreme Court held that “no federal law confers

immunity from state prosecution [s]” growing out of at

tempts to secure the right to vote. Since § 1971 did not

contain the specific prohibition against state action that

“punish[es] or attempts to punish” present in Rachel the

Court distinguished voting rights cases from public ac

commodations cases, and refused to permit removal. Under

this interpretation of § 1971(b), which is binding upon me,

I agree that the present case must be held not entitled to

removal.

On that ground I concur in today’s per curiam opinion,

and not on the ground therein stated, that the allegations

of the petitioner are “in contradiction of the specific charges

of the indictment.” The test of removability is the content

of the petition, not the characterization given the conduct

in question by the prosecutor.

and suggests that the two clauses should be given the same effect.

In this view the Supreme Court’s interpretation of § 203(c) in

Hamm v. City of Rock Hill, supra, 379 IJ. S. 306 (1965), would

apply with equal force to the prohibitions of § 1971(b). I t is

difficult to conceive that Congress intended to place voting rights

guarantees on a lower plane of protection than the right to equal

public accommodations.

9a

Judgment of United States Court of Appeals

for the Fourth Circuit

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

F ob the F ourth Circuit

No. 10,062

S tate of N orth Carolina,

vs.

Appellee,

R eginald A. H aw kins,

Appellant.

A ppeal from the United States District Court for the

Western District of North Carolina.

T his cause came on to be heard on the record from the

United States District Court for the Western District of

North Carolina, and was argued by counsel.

On consideration whereof, It is now here ordered and

adjudged by this Court that the judgment of the said Dis

trict Court appealed from, in this cause, be, and the same

is hereby, affirmed with costs.

Clement F . H aynsworth J r.

Chief Judge, Fourth Circuit

10a

APPENDIX II

Opinion of United States District Court

for the Western District of North Carolina

At its September-October term, 1964, the Grand Jury of

Mecklenburg County returned indictments against Dr.

Reginald A. Hawkins charging, without reference to any

particular statute, violations of the election laws of North

Carolina. On November 12, 1964, Dr. Hawkins removed

these cases (in this court given the single number 1943)

from the Superior Court of Mecklenburg County to this

court pursuant to 28 U. S. C. A. Sections 1443 and 1446.

The cases were set for trial before the undersigned district

judge and a jury for April 26, 1965. On that day, and for

the first time, the Solicitor for the State moved the court to

remand the cases to the Superior Court of Mecklenburg

County, questioning federal jurisdiction. The trial of the

cases was thereupon postponed and the question of juris

diction was set down for argument and heard on May 12,

1965.

The court has been helped tremendously by an excellent

historical brief filed by counsel for Dr. Hawkins.

It is conceded that there is no federal jurisdiction to try

these criminal cases arising upon indictments in the state

court unless it be under 28 U. S. C. A. Section 1443, which

reads as follows:

“Section 1443. Civil rights cases

“Any of the following civil actions or criminal prose

cutions, commenced in a State court may be removed

by the defendant to the district court of the United

l la

States for the district and division embracing the place

wherein it is pending:

“ (1) Against any person who is denied or cannot

enforce in the courts of such State a right under any

law providing for the equal civil rights of citizens

of the United States, or of all persons within the

jurisdiction thereof;

“(2) For any act under color of authority derived

from any law providing for equal rights, or for refus

ing to do any act on the ground that it would be in

consistent with such law.”

Since Virginia v. Rives, 100 U. S. 313 (1880), and Ken

tucky v. Powers, 201 U. S. 1 (1906), it has been well settled

that removal under present Section 1443(1) was allowable

only on a claim of facial unconstitutionality of a statute or

constitutional provision. In Rives the Court said that the

inability to enforce federal rights of which the removal

statute speaks “is primarily, if not exclusively, a denial of

such rights, or an inability to enforce them, resulting from

the Constitution or laws of the State, rather than a denial

first made manifest at the trial of the case”. Virginia v.

Rives, supra, 100 U. S. at 319.

It may well be argued that subsequent cases have put

too narrow a construction upon Rives. The Fifth Circuit

has noted, without approval or disapproval, that it may be

argued today that the Supreme Court would recognize the

right of removal under Section 1443(1) even where no legis

lative denial of rights is shown. Rachel v. State of Georgia,

342 F. 2d 336 at 339 (5th Cir. 1965). It would be presumptu

ous for a district court to anticipate such an interpretation

of Section 1443(1) by the Supreme Court. The Court of

Appeals for the Fifth Circuit in Rachel also declined the

invitation to do so.

The pertinent election laws of North Carolina, allegedly

violated by Dr. Hawkins, are facially constitutional. Inter

ference with an election registrar or usurpation of the au

thority of such a registrar is clearly the kind of conduct

which may be made punishable by a state. Section 1443(1)

has not yet been expanded beyond the narrow confines of

Powers v. Rives, supra. There is no federal jurisdiction

under 28 U. S. C. A. Section 1443(1).

Petitioner next contends that, in any event, jurisdiction

is conferred upon this court under subsection (2) of 28

U. S. C. A. Section 1443 for the reason that Dr. Hawkins

acted under “color of authority” to peacefully assist in regis

tering qualified persons to vote, and to extend suffrage,

under 42 U. S. C. A. Section 1971.

It is not altogether clear that Dr. Hawkins is one of

those persons who may act “under color of authority”.

Quite possibly 28 U. S. C. A. Section 1443(2) may be availed

of only by persons who are government officers or persons

acting on their behalf or at their instance. See Roard of

Education of City of New York v. Citywide Committee for

Integration, 342 F. 2d 284 at 285 (2d Cir. 1965).

But, assuming, without deciding, that Dr. Hawkins is one

of those persons who may come within the statute, it is quite

clear, in my opinion, that he did not act under “color of

authority” within the meaning of subsection (2) of Sec

tion 1443. Nothing in any federal statute called to my at

tention, nor in the Federal Constitution, directs or au

thorizes Dr. Hawkins to act as a North Carolina election

registrar, or to interfere with a duly-authorized registrar,

or to usurp the functions of such a registrar. However

13a

worthy Ms motives and activity may have been with re

spect to his legitimate desire to further suffrage, the laws

and constitutional provisions relating to the right to vote

are permissive rather than mandatory, and required of Dr.

Hawkins no action. Dr. Hawkins fails to point to any fed

eral law providing for equal rights or the right to vote

which gives him authority or direction to act in the way

and manner alleged by the State in its indictments.

“When the removal statute speaks of ‘color of authority

derived from’ a law providing for equal rights, it refers to

a situation where the lawmakers manifested an affirmative

intention that a beneficiary of such a law should be able

to do something and not merely to one where he may have

a valid defense or be entitled to have civil or criminal lia

bility imposed on those interfering with him.” People of the

State of New York v. Galamison, 342 F. 2d 255 at 271 (2d

Cir. 1965).

The construction of Section 1443(2) urged by Dr. Haw

kins would be a startling innovation having immeasurable

impact on federal jurisdiction. That the statute is nearly

one hundred years old and has never been so construed is

some indication of the novelty of the theory now advanced.

Since there is no jurisdiction, Dr. Hawkins’ motion to

dismiss the indictment is not reached.

The motion to remand will be allowed and an appropriate

order will be entered in accordance with this Memorandum

of Decision.

This 15th day of May, 1965.

J . B . C r a v e n , J r .

J. Braxton Craven, Jr., Chief Judge

Chief Judge

United States District Court for the

Western District of North Carolina

14a

Judgment of United States District Court

for the Western District of North Carolina

Order of R emand

For the reasons stated in a Memorandum, of Decision

filed simultaneously, I t is adjudged that these cases (desig

nated in this court as Cr. No. 1943) were removed improvi-

dently, and without jurisdiction, and it is accordingly

ordered that the cases he, and they hereby are, remanded to

the Superior Court of Mecklenburg County.

A certified copy of the Order of Remand shall be mailed

by the Clerk of this court to the Clerk of the Superior Court

of Mecklenburg County.

This 15th day of May, 1965.

J . B . C r a v e n , J r .,

J. Braxton Craven, Jr., Chief Judge

United States District Court for the

Western District of North Carolina

38