Simmon v Schlesinger Petition and Suggestions for Hearing in Banc

Public Court Documents

December 20, 1976

32 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Simmon v Schlesinger Petition and Suggestions for Hearing in Banc, 1976. 6ba8d272-c49a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/7f34881b-b27e-407f-9cfe-8c43231c4bb3/simmon-v-schlesinger-petition-and-suggestions-for-hearing-in-banc. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

r

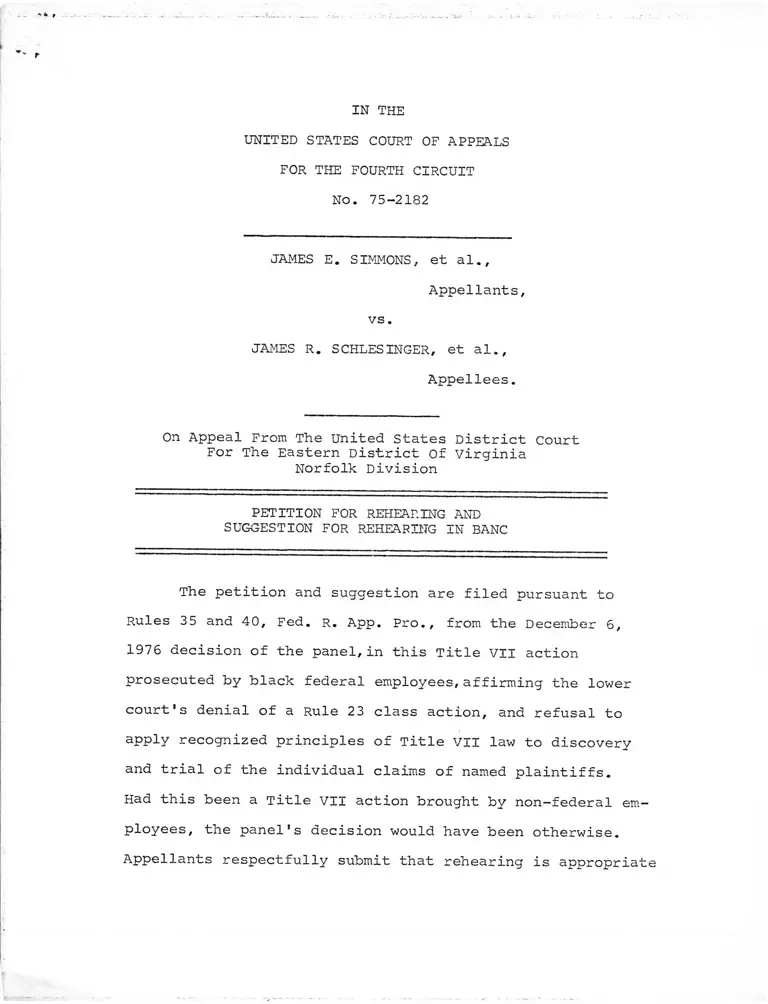

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

NO. 75-2182

JAMES E. SIMMONS, et al.,

Appellants,

vs.

JAMES R. SCHLESINGER, et al.,

Appellees.

On Appeal From The United States District Court

For The Eastern District Of Virginia

Norfolk Division

PETITION FOR REHEARING AND

SUGGESTION FOR REHEARING IN BANC

The petition and suggestion are filed pursuant to

Rules 35 and 40, Fed. R. App. Pro., from the December 5,

1976 decision of the panel,in this Title VII action

prosecuted by black federal employees, affirming the lower

court's denial of a Rule 23 class action, and refusal to

apply recognized principles of Title VII law to discovery

and trial of the individual claims of named plaintiffs.

Had this been a Title VII action brought by non-federal em

ployees, the panel's decision would have been otherwise.

Appellants respectfully submit that rehearing is appropriate

because the panel overlooked or misapprehended the record and

applicable law in ruling that federal employees have different

and fewer rights than all other employees under Title VII. More

over, the appeal raises questions of exceptional importance

concerning, first, the principle recently announced by the

Supreme Court that " [a] principal goal of . . . the Equal Employ

ment opportunity Act of 1972 . . . was to eradicate 'entrenched

discrimination in the Federal Service,' Morton v. Mancari, 417

U.S. 535, 547, by . . . according ' [a]ggrieved [federal]

employees or applicants . . . the full rights available in the

private sector under Title VII,'" chandler v. Roudebush. ___

U*S. ___, 48 L.Ed. 2d 416, 420 (1976); second, the uniformity

of this court's decisions construing Title VII with respect to

rights of employees; and, third, the effect of complex, confusing

and much-criticized Civil Service Commission administrative

1/

regulations and procedures on rights of federal employees in2/

court.

1. The panel opinion overlooked or misapprehended that the

purpose of the action is the same as in other "private attorney

3/general" Title VII suits that have come before the Court, viz. * S.

1/ See Chandler v. Roudebush, supra, 48 L.Ed. 2d at 424 n. 9;

Hackley v. Roudebush, 519 F.2d 108, 136-141 and 171 (Leventhal, J.);

S. Rep. No. 92-415, on S.2515, 92d Cong., 1st Sess. at 14-17 (1971)*

H.R. Hep. No. 92-238, on H.R. 1746, 92d Cong., 1st Sess. at 23-26

(1971); U.S. Comm, on Civil Rights, The Civil Rights Enforcement

Effort-1974, vol. V, To Eliminate Employment Discrimination (July

ls7iilip?oyer785(5 £a?~£?3Rtv? ton' Federal Government

2/ For the convenience of the Court, the petition discusses points

in the order they arise in the panel opinion.

3/ See, e.g., Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody. 422 U.S. 405 (1975);

Barnett v. w. T. Grant Co.. 518 F.2d 543 (4th Cir. 1975).

2

' K ,

to eliminate across-the-board policies and practices of racial

discrimination at an industrial plant as they adversely affect the

rights of both individual named plaintiff black employees and the

class of black employees and applicants generally. The panel

opinion, however, mischaracterizes the "’systemic' class discrimi

nation" claim as "manifestly . . . one not related to the

individual claims but one that was applicable and relevant to

the entire personnel organization of the Facility," p. 3 n.*

(emphasis added), although the complaint expressly asserts that

named plaintiffs bring the action "on their own behalf and on

behalf of the class they represent" (A. 4); identifies the potential

class as similarly situated black employees or applicants (A. 4);

identifies a broad spectrum of discriminatory policies and

practices (A. 4-5), and further states that " [e]ach of the

named plaintiffs has been a victim of some or all of the dis

criminatory acts of the defendants enumerated above" (A. 6).

The panel opinion’s distortion of the record is fundamental to

its erroneous decision: it is later used to justify unnecessary

specific class pleading and illegal bifurcation of inter

i m

related individual-class claims in administrative proceedings,

see infra at 2-13. The simple fact is that plaintiffs and the

potential class seek a judicial class action precisely because

their claims were not and could not have been effectively remedied

administratively. It is too late in the day to doubt that in a

Title VII litigation "racial discrimination is by definition

4/ Jenkins v. United Gas Corp.. 400 F.2d 28, 32 (5th Cir. 1968).

3

class discrimination."

5/

2. The panel opinion overlooked or misapprehended that

named plaintiffs did exhaust administrative remedies prescribed

by Title VII by submitting their claims of racial discrimination

to the agency for investigation, p. 12 et secy. The administra

tive complaint plainly states:

We believe we were discriminated against because

of our race (Black). We were placed out of the area

of consideration for the selection to GS-7 Production

Controller, by the rating panel. This is a process

that is used when there is a majority of Black applicants .

(A. 759). under applicable Title VII standards, this recital of

facts would have sufficed in the private sector to reasonably

result in investigation by the EEOC into like or related policies

6/ 7/

and practices, including systemwide patterns. in the federal

sector, this recital should have had the same result under clear

direction in the legislative history of the 1972 amendments that

the Civil Service Commission and federal agencies have failed to

8/"address themselves to the various forms of systemic discrimination"

and that they take advantage of "the significant reservoir of

expertise developed by the EEOC with respect to problems of

discrimination11 and "to work closely with EEOC in the development

9/and maintenance of its equal employment opportunity programs."

5/ Hall y. werthan Bag Corp.. 251 F. Supp. 184, 186 (M.D. Tenn.

1966); Qatis v. Crown Zellerbach Corp., 398 F.2d 496, 499 (5th Cir. 1968).

6/ See, e.g., Sanchez v. Standard Brands, Inc., 431 F.2d 455 (5th Cir. 197077^ ~ ~ ----

1/ See, , Jenkins v. United Gas Corp., supra, 400 F.2d at 33.

The panel opinion so concedes, p. 25.

8/ S. Rep. No. 92-415, supra at 14.

9/ S. Rep. No. 92-415, supra at 16.

4

If the agency's obligation needed to be clarified any further,

a federal district court has

present civil Service Commission regulations in issue on the

"exhaustion" question are illegal under Title VII and that the

Commission "must accept, process and resolve complaints of class and

systemic discrimination which are advanced through individual

complaints of discrimination and must provide relief to the class

when warranted by the particular circumstances of each class com-

10/

plaint." However, the agency in the instant case shirked its

legal obligation to fully investigate the charge of discrimination,

even though named plaintiffs gave the agency explicit notice of

their belief that at least some systemic patterns were known to

them when they asserted that " [t]his is a process that is used

when there is a majority of Black applicants," and even though

the job histories of named plaintiffs demonstrate that their

careers and ability to meet "paper" experience and qualification

standards for promotion have been adversely affected by systemic

n • • 11/policies and practices.

The panel opinion, however, announces the unprecedented

rule in Title VII litigation that employees must affirmatively

plead class allegations in addition to a factual statement of their

charge of discrimination in order later to be able to file a

judicial class action. This misplaces the administrative burden

of investigating the class dimension of charges on complainants

10/ Barrett v. u. s . Civil Service Commission, 10 EPD If 10,586 at 6450 (D.D.C. 1976).

11/ See Brief For Appellants at 9-13. The administrative record in ract does show that one of the investigators requested department and plant-wide racial statistics by grade (A. 814-185) and considered them in recommending relief for plaintiffs (A. 794). The recommendation was not followed.

5

who have neither the statutory or regulatory obligation nor the

ability to investigate their own claims, rather than on the

agency which has both the obligation and ability to fully investi-

12/

gate, resolve and remedy the charge. The administrative process

is designed for informal resolution; it is not a formal proceeding

. . . , 13/m which common law pleading rules have a place.

3. The panel opinion overlooks or misapprehends that

"Congress . . . chose to give [federal] employees who had been

through [administrative] procedures the right to file a de novo

civil action1 equivalent to that enjoyed by private sector

employees," in suits brought pursuant to 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-16,

Chandler v. Roudebush, supra, 48 L.Ed.2d at 432,that an equivalent

action includes resort to Rule 23 class action procedures; that

con ccdcGCongress specifically cited Qatis and Jenkins (which the opinion/

would permit a class action if this were a private sector case)

with approval in explicating the right to class actions under 42

14/

U.S.C. § 2000e-5 general Title VII procedure sections, and that

§ 2000e-5 "shall govern [federal] civil actions" brought under

§ 2000e-16. This is surely enough to pretermit the panel

opinion's long dissertation on "exhaustion" that attempts to

distinguish what cannot be distinguished, P. 12 et sec. ^

12/ See 5 C.F.R. § 713.216. The employee can only "prosecute" his

a llmited fashion at an optional administrative hearing,

136-14118* SeS generally Hackley v, Roudebush, supra, 519 F.2d at

13/ See, e.g., Love v. Pullman Co., 404 U.S. 522 (1972).

-j~/ ^S * Rep* No. 92-415, supra at 27; 118 Cong. Rec. 7168, 756 (Conference Commxttee Section—by—Section Analysis).

See Chandler v. Roudebush. supra, 48 L.Ed. 2d at 423-424.

16/ Chandler simply cannot be distinguished as involving only the

de novo issue because the right to a plenary judicial proceeding is

6

With respect to "exhaustion," the panel opinion simply

ignores the rule that " [a]pplication of the doctrine to specific

cases requires an understanding of its purposes and of the

17/particular administrative scheme involved." Thus, the opinion

attempts to justify an altogether novel Title VII administrative

pleading requirement by ignoring the obligation of the agency

to investigate the class aspects of cases whether pleaded or

18/

not. The court relies on mostly non-Title VII non-class

action cases dealing not with scope of administrative claims,

19/but with the total failure to exhaust administrative remedies.

16/ (cont'd)

basic and properly encompases class action procedures, nor as

dealing only with "procedure in the judicial proceedings" since

that is precisely what is in issue because named plaintiffs have

exhausted. The rule stated in Hackley v. Roudebush, supra, cited

with approval by Chandler, and lower court decisions(granting

class actions on the basis of a reading of § 2000e-16 requiring

the same rights for federal and non-federal employees, that proved

consistent with Chandler), see p. 21, n. 21 is on point. See also

Thompson v. Roudebush, N.D. 111. No. 74 C 3719, memorandum opinion

dated October 12, 1976.

17/ McKart v. United States, 395 U.S. 185, 193 (1969).

18/ See supra at 4-6.

19/ Brown v. G.S.A.. ___U.S.___, 48 L.Ed. 2d 402 (1976), for

example, discusses the administrative process only in terms

of the need not to exhaust under other judicial remedies and then

only the regulations on their face. Beale v. Blount, 461 F.2d

1133 (5th Cir. 1972) and Penn v. Schlesinger, 497 F.2d 970

(5th Cir. 1974), also 42 U.S.C. § 1981 cases, do not establish

an alternative Fifth Circuit "exhaustion" standard for federal

Title VII cases; indeed, Brown specifically overruled the

Beale-Penn requirement of exhaustion under § 1981. The question

of federal Title VII class actions is presently before the

Fifth circuit in three pending cases, McLaughlin v. Callaway,

No. 75-2261; Swain v. Callaway, No. 75-2002 and Eastland v .

TVA, No. 75-1555, with the Civil Division having confessed

error that the "exhaustion" standard now adopted by the panel

opinion is erroneous, see infra at 8-9.

7

The opinion uncritically embraces the peculiarities of an

administrative process whose regulations and actual operation

have been condemned by congress, the U.S. Commission on Civil

2 0/

Rights and the courts, particularly provisions whose

21/

illegality under Title VII, the Solicitor General does not

22/

oppose. Lastly, the panel opinion relies on the purpose of

"conservation of judicial energy" which is not in issue because

specific class claims are unnecessary and which the Supreme Court,

23/

in any event, has disowned in the federal Title VII area.

4. The Solicitor General of the United States has expressly

conceded that there is no provision in present civil Service

Commission regulations for administrative class actions by

approving of the declaratory judgment order in Barrett v, U.S.

civil Service Commission. ("A district court . . . has recently

invalidated Commission rules that effectively prohibited

administrative class actions," Brief For Respondents, Chandler

v. Roudebush, No. 74-1599 at p. 65. The regulations the Solicitor

General refers to are still in effect.) Moreover, the Assistant

Attorney General for the Civil Division of the Department of

Justice has expressly conceded in the Fifth Circuit that the

district court erred in holding that the third-party complaint

20/ See supra at 2 n. 1.

21/ See suma at 5 n. 10.

22/ See infra.

23/ Chandler v. Roudebush, supra.

8

process should have been exhausted. This point standing

alone warrants rehearing so that government attorneys can

account for their position before this Court,upon which the

panel opinion relies, although the government is unwilling to

argue for it in the Supreme Court and the Fifth Circuit.

5. The panel opinion overlooked or misapprehended the

futility of named plaintiffs raising claims of and obtaining

relief for class discrimination in "individual" administrative charge

p. 30 et_ seq. First, named plaintiffs indicated on their

administrative charge that there were class dimensions to their

25/

claim and the agency simply did nothing. Thus, the futility

of these named plaintiffs raising and obtaining relief on a

broader class claim is a_ fortiori obvious. Second, the Civil

24/

24/ "As interpreted by the Civil Service Commission,

the regulations do not permit filing of a class

action administrative complaint. 5 C.F.R.

713.251 is designed to permit third party com

plaints and not class action complaints.

5 C.F.R. 713.251 is not a substitute for the

filing of individual complaints, and plaintiff

could not use 5 C.F.R. 713.251 to prosecute

his individual claim on behalf of a class.

Rather, it is contemplated that groups, (e.g.,

civil rights organizations) or other third

parties will use 713.251 to prosecute "general

allegations . . . which are unrelated to an

individual complaint of discrimination." (Emphasis added)

Brief For The Defendants [-Appellees], McLaughlin v. Callaway,

5th Cir. No. 75-2261 at 13, reversing position taken in, 382

F. Supp. 885 (S.D. Ala. 1974).

25/ The panel opinion argues that named plaintiffs should not

only have raised the claim but "prosecuted" it, overlooking or

misapprehending that the regulations do not contemplate or

provide for any role for complainants to do anything in the

investigation phase, see supra at 4-6 . The agency is required

to "prosecute" the claim. No authority in law or equity requires

that employees be penalized for the failure of the Civil Service

Commission and agency to perform its duty.

9

Service Commission regulations on their face and as

authoritatively construed are clear that class claims cannot be

26/raised and remedied in individual charges as such. Third,

the panel opinion's citation of cases in which agencies and CSC

"considered" class claims supports the proposition that

exhaustion of class claims in individual charges is futile.

The cases do not establish that Commission or agencies will

provide relief for class or systemic discriminatipn; indeed,

2 7,the cases relied on clearly establish precisely the contrary.

26/ 5 C.F.R. § 713.212 provides that the individual complaint

sections do not apply to "general allegation [s] of discrimination

by an organization or other third party which Tare] unrelated to

an individual complaint of discrimination" and has been authorita

tively construed as not permitting "general allegations of discrimi

nation within the context of individual complaints of discrimination.

See discussion in Memorandum in Support of Plaintiff's Motion For

A Reconsideration Of The Order Denying Class Action And For A

Motion Requiring The Defendants To Answer Interrogatories, filed

March 31, 1974 (A. 3) at 3-5. For the convenience of the Court

the memorandum is attached hereto as Appendix A. Moreover,

effective classwide relief simply is not obtainable; the Com

mission's Discrimination Complaints Examiner's Handbook at p. 74

(April 1973) specifically provides:

"In some instances, only one person out of a

similarly situated group of employees files a

complaint of discrimination. I.f the Examiner

finds discrimination in such a case, any specific

corrective action, for example, promotion, may

be recommended only for the complainant. Recom

mended corrective action relevant to the general

environment at the activity should, of course,

be brought to the attention of the agency Director

of Equal Employment Opportunity in the recommended

decision or by separate memorandum or letter."

The Civil Service Commission Appeals Review Board has specifically

upheld this policy, see Ralston, The Federal Government As

Employer, supra, 10 Ga. L. Rev. at 734.

2_7_/ Contrary to the asertion at pp. 32-33, none of the administra

tive charges in Sylvester v. U. S. Postal Service, 393 F. Supp.

1334 (S.D. Tex. 1975) contained any express class claim, see

Appendix B. The "class claim" referred to was investigated without

a class pleading as should have occurred in the instant case.

(cont'd)

10

Fourth, the government has never contended that class claims

could be raised and remedies in individual proceedings or

28/

disputed plaintiffs' showing of futility, and, consequently,

no evidentiary record exists of whether named plaintiffs made or

attempted to make such a claim, although there is a colorable

297 --------------------------------

factual issue. (At the very least, the Court should remand

the case to the trial court for a hearing in light of the Court's

unanticipated exhaustion rule. Cf., Ettinger v. Johnson. 518

F.2d 648, 652-653 (3d cir. 1975)). Fifth, assuming again that

the panel opinion was correct, it is inexplicable why a narrower

class action is impermissible since named plaintiffs did specifi

cally assert that " [tjhis is a process that is used when there is

a majority of black applicants," i.e., stating a specific claim

for black employees and applicants subject to discrimination in

staffing or selection procedures.

27/ (Cont'd)

In none of the cases cited did the agency or the Commission

provide classwide or systemic relief. Indeed, in Williams v.

TVA, 415 F. Supp. 454 (M.D. Tenn. 1976), the very part of the

opinion cited at p. 34 refuses to treat the class claim as a

remediable charge in behalf of a class, but only as to "a discrimi

natory environment which has a direct bearing on the matter

forming the basis for the individual complaint."

28/ The government only argued that a separate third-party charge

pursuant to 5 C.F.R. § 713.251 had to be filed, see, e.g.,

Defendants' Brief In Opposition To Maintenance Of Class Action

And Trial De Novo, filed December 5, 1974 at 1-4 (A. 2) and Brief

For Appellees at 14 et_ seq.

29/ The attached affidavit of named plaintiffs' counsel, Mr.

Archie Elliott, states that he and named plaintiffs made broad

class claims, but that the EEO Counselor refused to accept the

claims and discouraged making them part of the administrative

charge, see Appendix.C. (Mr. Elliott was counsel for the initial phase of administrative proceedings: named plaintiffs engaged present counsel only after the events in question had occurred).

11

6. The panel opinion overlooked or misapprehended that

Civil Service commission regulations plainly do not permit

employees to simultaneously file individual and 5 c.F.R. § 713.251

third-party administrative complaints in an effort to plead class

claims within the present regulatory scheme, pp. 36-37. Section

713.251, cited at p. 36-37 n. 38, expressly states "This section

applies to general allegations by organizations or other third

parties of discrimination in personnel matters within the agency

which are unrelated to an individual complaint of discrimination

subject to §§ 713.211 through 713.222" (emphasis added). Appendix

III to Reply Brief For Appellants is a Commission decision in

which the Appeals Review Board authoritatively construed

§§ 713.212 and 713.251 prohibit employees to file simultaneously:

"General allegations are not within the purview of section 713.212

of the civil Service regulations and must be raised by an organi

zation or other third party under the provisions of section 713.

251," III-3 (emphasis added). Third-party complaints, in any

event, do not result in an investigation as such but only a

"management review" and relief in fact provided is wholly

30/

ineffective. Moreover, the opinion concedes that the Civil

Service Commission regulations, as framed, do not contemplate

a right to sue under Title VII, but correctly decides that

31/

there is such a right now, pp. 39-40. "Exhaustion" of the

30/ Ralston, The Federal Government As Employers, supra, 10

Ga. L. Rev. at 734 n. 102; see also Appendix A at 6-7.

31/ The opinion, here as elsewhere, misdescribes appellants'

position; the failure of the Civil Service Commission and government

attorneys (defending Title VII actions from third-party complaints)

to recognize a right to sue was raised in Reply Brief For Appellants

at 5-6, see also Appendix A at 7.

12

Pa^ty complaint procedure thus was futile for named plain

tiffs .

32/ With resPect to the discovery issue, there is no

doubt that an equivalent de_ novo trial encompasses broad

.. . , . 33/discovery permitted m non-class action Title VII cases. The

panel opinion, however, overlooked or misapprehended the record

that answers to first interrogatories were sought to prepare for

34/

the individual and class claims, and that defendants did

32/ Cf. Hackley v. Roudebush. supra, 520 F.2d at 157-158;

Chandler v. Roudebush, supra, 48 L.Ed.2d at 420.

13/ McDonnell Douglas Corp. v. Green, 411 U.S. 792, 804-07

(1973); Burns v. Thikal Chemical Corp., 483 F.2d 300 (5th Cir.

1973)? Rich v. Martin Marietta Corp.. 522 F.2d 333 (10th cir. 1975).

34/ The motion to reconsider denying class action and motion to

compel the defendants to answer interrogatories plainly states,

Plaintiffs assert that they are entitled to have this litigation

proceed as a class action through the discovery stages at least

according to McDonnell Douglas v. Green, 411 U.S. 792 (1973)"

(A. 71). The portion quoted by the panel opinion at p. 46 follows

soon thereafter, but is cited out of context. The memorandum in support dispells any doubt.

Clearly, if this case does proceed as a

class action, plaintiffs are entitled to full

class-wide discovery. We further urge, however,

that even if this Court~holds that a class action

is not appropriate, plaintiffs still must be

allowed to do broad discovery. The Courts have

consistently held that even an individual claim

of racial discrimination can only be properly

judged in the context of information relating

to the general practice of the employer.

(Emphasis added)

Appendix A at 9, see generally 9-11. Plaintiffs' motion for appeal

pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 1292(b) similarly states: "Plaintiffs

assert that their ability to participate in the trial of the

individual claims of federal employees in the instant case will

be severely limited and handicapped by the bar on broad discovery

of racial discrimination in employment practices and denial of the class action" (A. 75) .

13

not provide information sought in a limited subpoena.

The prejudice is per se when plaintiffs are deprived of relevant

2&/discovery to prepare and put on their case, but especially

so in the instant case where only the defendants were permitted

to present their selected broad statistical and other system-wide

data and the district court did rely on such information in

ruling against named plaintiffs on their individual claims (A. 120-

121) .

8. Lastly, the panel opinion overlooked or misapprehended

that the court below erred as a matter of law in its adjudication,

and that defendants' case for rebuttal, which was hindered in

no way by discovery limitations, was legally insufficient

such that reversal and judgment for the plaintiffs on their

individual claims would be appropriate. Appellants make this

point even though they suffered clear prejudice and are entitled

to conduct the broad discovery denied then below in order to

further develop their prima facie case and to demonstrate the

pretextual nature of the defenses, because defendants' case was

so weak that they cannot in any event have prevailed.

35/

35/ Defendants' response to the subpoena duces tecum is set

forth in a motion for protective order and affidavit of Mr. James

Early filed May 13, 1975 on the eve of trial (A. 3a). The motion

states " [t]hat the material sought pertains to the class action

the maintenance of which has been denied on several occasions;"

the affidavit states reasons why the material sought in the

subpoena was not being provided. The motion does recite that

the Navy had furnished "the plaintiffs with all available

information regarding the individual plaintiffs lawsuit": this

information was later submitted as defendants1 exhibits. At no

time were plaintiffs permitted to conduct discovery of their

individual claims under procedures set forth in the Federal Rules

of civil Procedure.

36/ See cases supra, at 13, n. 13.

14

CONCLUSION

For the above reasons, appellants request that the Court

grant the petition for rehearing and suggestion for rehearing

en banc.

HENRY L. MARSH, III

RANDALL G. JOHNSON

STEPHANIE J. VALENTINE

HILL, TUCKER & MARSH

214 East Clay Street

P. O. Box 27363

Richmond, Virginia 23261

JACK GREENBERG

CHARLES STEPHEN RALSTON

MELVYN R. LEVENTHAL

BARRY L. GOLDSTEIN

BILL LANN LEE

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Counsel for Appellants

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I hereby certify that a copy of the foregoing Petition

for Rehearing and Suggestion for Rehearing En Banc was mailed

this 20th day of December 1976, to Seth M. Lloyd, Lt., JAGC,

USNR, Department of the Navy, Office of Civilian Manpower

Management, Washington, D. C. 20390, and to Edward R. Baird,

Jr., Esquire, Assistant United States Attorney, P. 0. Box 60,

Norfolk, Virginia 23501, counsel for appellees.

15 Counsel for Appellants

standard government employment dispute. To rut plaintiff's

position in the proper context, it is necessary to discuss both

the claims sought to be raised here, and to describe in some

detail the limited nature of administrative process available

to raise charges of racial discrimination.

I.

THE CLAIMS ADVANCED 3Y PLAINTIFFS RELATE TO

DISCRIMINATION AGAINST BLACKS AS A CLASS.

This case involves precisely the kinds of issues that

have been litigated innumerable times against private employers

in Title VII suits brought both by employee plaintiffs and

range

of employment and promotion policies that have the effect of

discriminating against blacks ajs a_ class. They seek to correct

. /systemic practices that impinge on their right to equal employ-

.ment practices as members of the class of black workers affected

“by stigmatization and explicit or implicit application of a

badge of inferiority."

:! 2/i| the United States. That is, plarntirrs are attacking

_______________________ !1/ See, e,g,, Jenkins v. United Gas Corp., 400 F.2d 28 (5th Cir.j

• 1968); Johnson v. Georgia Highway Express, Inc., 417 F.2d 1122

I (5th Cir. 1969); Moody v, Albemarle paper Company, 474 F.2d 134 j

| (4th Cir. 1973).

I 2/ See, e,q ,, Graniteville Co. v. EEOC. 438 F.2d 32 (4th Cir.

1971); United States v. Georgia Power Company, 474 F.2d 906

lj (5th Cir. 1973) .

jj 3/ Sosna v. Iowa, ___ U.S. ___, 43 U.S.L.W. 4125, 4132 n.l

(1975) (White, j., dissenting). Justice white, who dissented

II from the application of established Title VII law to class

actions generally, went on to point out that Congress had given

j persons aggrieved by such systemic discrimination “standing . . .'

I| to continue an attack upon such discrimination even though they i

fail to establish injury to themselves in being denied employ-

|j ment unlawfully." See, Moss v. Lane Company, Inc., 47.1 F.2d 853 j

I (4th Cir. 1973).1

A ' I

Thus, the complaint alleges that the defendants have taken

and wil continue to take systemic "personnel actions based on

discrimination because of race." These actions include, inter,

alia: recruitment; denials of promotions and supervisory status;

promotion based on subjective recommendations; discriminator/

performance and disciplinary standards; discriminatory assign

ment into deadend jobs; and failing to have either effective

iarfirmative action programs or an effective complaint procedure |

(Complaint, pp. 4-5).

The complaint goes on to allege that each of the plaintiffs

has been aggrieved by those general and systemic practices.

The particular incident that gave rise to their administrative

complaint and this lawsuit is but one particular instance of

what they complain of; thus, that incident can be properly as

sessed only in the context of a fully developed record as to the

general and systemic employment practices at N.A.R.F.

II.

THE ADMINISTRATIVE COMPLAINT PROCESS DOES

NOT PERMIT SYSTEMIC CLASS CLAIMS TO BE

RAISED'AND ADJUDICATED.

This Court based its decision not to permit a class action

in part on the ground that class claims had not been raised in

the administrative process. Plaintiffs urge that an examination

of the administra tive procedures for adjudicating EEO claims

can not be raised as part of an EEO complaint. Moreover, con

trary to the argument of the government, the "third-party" com

plaint procedure under §713.251 does not provide a vehicle where

by individual complainants can obtain an adjudication of class-

type claims. Thus, this is a case where there exists no adequate

administrative remedy that had to be exhausted. see, k . Davis,

Administrative Law, § 20.07.

A. The Individual Complaint Process

Both the regulations on their face and decisions of the

Civil Service Commission make it clear that class claims can not

- 3 -

A -3

S5ST>?

/ \ I

be made by an individual federal employee filing a complaint of j

racial discrimination. Thus, individual comolaints are oro- I

cessed pursuant to §§ 713^211-713.222; section 713.212 provides !

that those sections do not apply to "general allegation!"s] of

discrimination by an organization or other third oartv which

[are] unrelated to an individual complaint of discrimination." '

The Civil service Commission has authoratively interpreted this j

language as not permitting "general allegations of discrimination

within the context of individual complaints of discrimination." j

In a case involving NASA, an employee charged that she had been j

discriminated against when she was not selected for a particular

promotion. She alleged that:

[M-] inorities, as a class, have been and are

discriminated against because of the Center's

personnel policies and practices as they cer

tain to recruitment, hiring, initial assign

ments, job classifications, merit promotions,

training opportunities, retention," and the

terms, conditions, and privileges of employment.

I

II

These allegations, of course, are of precisely the kind

made in plaintiffs' complaint here. The Appeals Review Board

of the civil service Commission, in a letter decision attached

hereto as exhibit A, affirmed the agency's rejection of these

allegations of class discrimination as part of the individual

complaint. It held that:

There is no provision in the civil service regulations j

for the processing of general allegations of dis

crimination within the context of individual com

plaints of discrimination.

Rather, such allegations can only be raised "by an organization ̂

or other third party under the provisions of section 713.251."

This interpretation of the regulations has been expanded !

in a recent memorandum to all government EEO Directors sent out

by the Commission's Assistant Executive Director in charge of I

EEO (attached hereto as exhibit B). The memo states that class |

, iallegations can be made by an individual only "as long as the j

allegations relate to general matters and are not related to in

dividual complaints."

4

bs

'“N

These restrictions on the questions that may be raised by ■

individual complaints derive from an action by the Commission

ij itself in a case raising charges of religious discrimination in '

■ promotions. The 3oard of Appeals and Review (now the Appeals j

and Review Board), found discrimination against Jewish employees,

generally and ordered relief for the individual complainants

(3.A.R. decision No. 713-73-455, attached hereto as Exhibit C).

jj The commission, exercising its authority under §713.235, re-

opened the case for the purpose of establishing binding policy. 1

It vacated BAR's decision on the ground that the complaint was

jj not "a valid first-partv complaint," since the claim/was a

!! ‘ i•j general rarlure to promote Jewish employees since 1955 (see,

letter of December 19, 1973, attached hereto as Exhibit D).

;i iOne consequence of these rules is that broad evidence of

class-wide discrimination is not even admissible in an EEO

ji;j complaint adjudication. Thus, in B.A.R. decision No. 713-73-

ij 593 (attached hereto as Exhibit E) , the refusal of the complaints

lj ’ Examiner to permit certain witnesses at the hearing into an EEO I

•I complaint was upheld. 3.A.R. held:

ii ' !The other witnesses requested by the complainant would:

1 not have first-hand knowledge of the complainant's

case, and it is assumed that they were to testify

relative to the equal employment opportunity program

with respect to Hispanic Americans, and particularly

to Puerto Ricans. Any complaint involving a minority j group agency-wide is a "third-party" complaint and it ;

is processed under a different set of procedures.

Finally, another restrictive rule limits the possible

scope of an EEO charge filed under Part 713. An employee must !

Ii Igo to a counsellor within 30-days after some act of discrimi- ;

nation, and only matters occurring within that short period may I

'I I'j. become the basis for the formal complaint. Any concept of a

"continuing violation," a principle long-recognized by the |jj courts in Title VII cases, has been squarely rejected by the

ij Commission:

As regards the matter of "continuing" discrimination, I

5 CFR 713-214 establishes a time limit in which a

matter must be brought to the attention of an EEO

Counselor before that matter can be accepted as a

-■ , •• •■»

%&ZES3t-

\

valid basis for a complaint. Therefore, the require- ;

ment implies that a complaint must be over a specific

employment matter which occurred at a specific time. i

There is no provision whatsoever for accepting non

specific complaints of "continuing" discrimination.

Decision dated October 15, 1974, emphasis added (attached hereto,

as Exhibit F).

■j i

3. Third-party Complaints

The government here has argued that the third-party

■; complaint procedure under §713.251 was available to the plaintiffs

i i; and had to be followed as a condition to their filing a class-

action complaint in court under Title VII. Neither the text of \

:! the regulations nor their application supports the government's :

position. First, 713.251 itself specifically states that it

, i| applies only to general allegations "by organizations or other

j third carties" that are "unrelated to an individual comolaint of'

ij ' !discrimination." Similarly, the explanatory Memorandum sent out

II * jj! by the Commission (Exhibit 3), makes it clear that a third party'l|

|j complaint is not possible if the allegations relate, to the com- 'II |plaints of any individuals. The general allegations involved

ijj nere, of course, are directly related to the plaintiffs' own com

il plaints.

ij I

Second, the third-party allegations procedure is not *ad-

judicatory in nature. As described by the regulation and

I Exhibit B, its purpose is simply "to call agency management's j

attention" to allegedly discriminatory policies. Third-party j

;i allegations are "handled solely through an agency investigation, "

jj there is no right either to a hearing or to present evidence in

j| any formal way. Further, the investigation itself:

[I]s not expected to cover individual cases in

sufficient depth which necessarily would result in |

findings or decisions with respect to those in

dividuals.

There is no right to an appeal to the civil service Commission,

rather, only a "review" can be sought. The review is not con-

! ducted by the Appeals Review 3oard as an adjudication of rights;.

rather it is handled by the Commission's Bureau of personnel

Management Evaluation. At most that review may result in a

request to the agency to conduct a further investigation; there

iis no adjudication as such.

Third, consistent with the above, the Commission does not :

consider that the third-party allegation procedure under §713.251

gives rise to the right to proceed in federal court under Title !

VII. Thus, §713.282 provides when "an employee or applicant" i

iwill be notified of his right to file>- a civil action. It refers

only to §§713.215, 713.217, 713.220, 713.224, and 713.234, viz./

those sections relating to individual complaints, and excludes :!

any reference to §713.251. In accord with §713.282, the Com

mission does not notify a third-party complainant of a right

to bring action when it concludes its review under §713.251(b).

See, Exhibit G, attached hereto. Finally, the government's

argument here that exhaustion of remedies under 713.251, is a

prerequisite to filing a class action is totally inconsistent j

with its position in cases where third-party complaints have I

been filed. Thus,' in MEAM v. NASA, D.D.C. C.A. No. 74-1832, the

government has opposed a class action on the ground that under ;

the regulations discussed above, "Such Third Party complaints

!are administrative matters appealable to the civil service Com- :I

mission, and there is no right to file a civil action thereon." j

(Memorandum in Support of Motion of Defendants To Strike-, to

Sever, To Dismiss in Part, and to Remand In Part, p.3).

i-

III.

THIS CASE CAN PROCEED AS A CLASS ACTION

As noted above, plaintiffs have already brought to the

Court's attention the legislative history Qf and court decisions^

under Title VII that they contend establish their right to main

tain this suit as a class action. Here, we will simply make a j

few additional points that address themselves to the bases for 1

the Court's ruling against a class action.

,4-7

First, it is no douot true that particular employment de

cisions regarding individual federal employees often involve

questions peculiar to the circumstances of the particular

employee. However, this is certainly no less true of employees’

of private employers, but that fact has never been held to bar

a class action under Title VII against a private company. In

deed, such a proposition would totally negate the concent of oat

tern and practice suits upon which all Title VII actions

iprosecuted by the government are based. The courts have uni

formly distinguished between the question of the validity of

general employment practices on the one hand, and that of the

impact of such practices on individual employees on the other.

With regard to the former, general declaratory or injunctive

relief is appropriate; with regard to the latter, individualized

promotion, hiring, or 'specific back, pay awards may be the proper

relief. see, e.g,, Moss v. Lane co., Inc., 471 F.2d 853 (4th

Cir. 1973); Brown v. Gaston County Dyeing Machine co., 457 F.2d!

1377 (4th Cir. 1972). Here, the plaintiffs seek to remedy both;Ithe systemic problems common to all black employees and to ob

tain relief from the particularized injury they have suffered.

Moss and 3rown clearly establish that these two goals are not

exclusive. I

Second, the government has argued that the "employee ag- j

grieved" language, and the existence of an allegedly effective

alternative administrative procedure militates against a class ;

action. We urge that precisely the opposite is the case. in

Lance v. Plummer, 353 F.2d 585 (5th Cir. 1965), an action under

Title xi of the 1964 Civil Rights Act brought under the predeces

sor to Rule 23, the defendants argued that since the United

States Attorney General could bring a "pattern or practice"

suit, a "person aggrieved" was restricted to an individual l

action when he sought to enforce Title n. The Fifth Circuit

rejected this view and held that civil rights actions can be

brought as class actions generally. When Rule 23 was revised,

""s

the Advisory Committee pointed out

ally directed towards civil rights

"action or inaction is directed to

of this subdivision even if it has

threatened only as to one or a few

vided it is based on grounds which

the class." 39 F.R.D. 102 (1966).

alleged in this case.

that 23(b)(2) was specific-

action, and explained that:

a class within the meaning

taken effect or is

members of the class pro-

have general application to

Precisely this has been

IV. I

THE DEFENDANTS SHOULD BE REQUIRED TO

RESPOND TO THE PLAINTIFFS' INTERROGATORIES. '

ii

Clearly, if this case does proceed as a class action,

plaintiffs are entitled to full class-wide discovery, we

further urge, however, that even if this Court holds that a

class action is not appropriate, plaintiffs still must be al

lowed to do broad discovery. The courts have consistent held i

that even an individual claim of racial discrimination can only

be properly judged in the context of information relating to i

the general practices of the employer. See, Burns v. Thiokol !~ IChemical Corporation, 483 F.2d 300, 306 (5th Cir. 1973). Thus,:

the Supreme Court of the United States in McDonnell Douglas v.

Green, 411 U.S. 792, 804-805 (1972) held in an individual case !i

not brought as a class action, that since "petitioner's general!

policy and practice with respect to minority employment" (411 !

U.S. at 804-05) is relevant to determining the validity of an j

individual claim of racial discrimination, "statistics as to

petitioner's employment policy and practice may be helpful to a

determination of whether petitioner's refusal to rehire re

spondent in this case conformed to a general pattern of dis

crimination against blacks." 4/ The government cannot advance i

4/ It is interesting that the United States in its amicus

curiae brief filed in McDonnell Douglas at page 11, n.10,

acknowledged that "the use of statistics and other documentary

proofs can of course substantially strengthen the plaintiff's case in a private non-class action."

any reason as to why such general information is not relevant

to deciding an individual claim of a federal employee, since,

whatever may be the merits of the government's claim that there

is a difference between federal employees and private employees

with regard to trials de novo and class actions, the elements

of proof of a claim of discrimination against any employer are

the same.

Indeed, the government has consistently, and success

fully, argued that the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission

has the right to access to precisely the kind of information i

sought here when it is investigating an individual charge of i

discrimination. See, Graniteville Co. v. EEOC, 438 F.2d 32

(4th Cir. 1971); Georgia Power v. EEOC, 412 F.2a 462 (5th Cir.

1969); Local No. 104 v. EEOC, 439 F.2d 237 (9th Cir. 1971);

Blue Bell Boots, Inc., v. EEOC, 418 F.2d 355 (6th Cir. 1969).

The Fifth Circuit has applied in Burns v. Thiokol, supra, those

decisions in deciding whether broad discovery requests in a

private non-class Title VII action should have been granted. j

It held that such information was clearly relevant, in a dis

covery sense, to the proper adjidication of an individual, non-

class claim. The only reason for the government's now taking

a position directly contrary to the one advanced in the above

cases, is that here it is seeking to block access to such in

formation as a defender against an adequate inquiry into al- i

leged discrimination.

Under the principles of the above cases, the inter

rogatories prepounded by the plaintiffs here are clearly

proper discovery, in that they are designed to lead to relevant

evidence. The government has long been under a legal duty not ,

to discriminate. The complaint here alleges that NARF has,

for a long period of time, pursued discriminatory practices,

of which the particular failure to promote the plaintiffs is

but the most recent example. The plaintiffs are employees of

long standing who have consistently been the victims of these

practices. As demonstrated by their employment records they

10

have been denied promotions and job changes time after time

over a period of twenty years. The interrogatories seek to

determine the employment patterns of NARF since I960, a

period encompassing the employment of the plaintiffs, and a

Per -̂0<̂ fully consistent with decisions requiring discovery

against private employers. See, e,q., Burns v. Thiokal. suora,

where the company was required to give data going back to 1960 '

over a claim of undue burden.

j

The interrogatories quoted in notes 4-7 of the Thiokol

decision are quite similar to those propounded here. Thus,

here, plaintiffs seek information relating to: (1) the

organization of NARF, the names and descriotion of all jobs,

and the race of those occupying them (Interr. No. 1); (2)

applicants for jobs and / their race and qualifications, hiring

procedures, the procedures for assigning new hires to various i

jobs, and any tests, manuals, etc., used in the process (Nos.

2-3); (3) methods of recruitment (Nos. 32-42); (4) training

courses and temporary assignments (Nos. 43-45); (5) the process’

of handling EEO complaints (Nos. 48-51); (6) the race of

persons in all job positions, divisions and organizational

units (Nos. 52-66); (7) promotions and transfers (Nos. 67-85), !

and other relevant matters. All of this information is

directly related to the crucial issue in this lawsuit, whether \

it proceeds as a class action or as an individual action, viz.,

has there been a pattern of racially discriminatory employment !

practices that has affected individual employment decisions?

Without this information the plaintiffs cannot prepare for

trial, and the court cannot adjudicate their claims.

Respectfully submitted,

HENRY L. MARSH, III

WILLIAM H. BASS, III

STEPHANIE J. VALENTINE

HILL, TUCKER & MARSH

214 East Clay Street

Richmond, Virginia 23261

- 11 -

A-n

t1

JACK GREENBERG

BARRY L. GOLDSTEIN

CHARLES STEPHEN RALSTON

10 Columbus Circle Suite 2030

New York, New York 10019.

Attorneys for Plaintiffs

!

UNITED STATES POSTAL SL JICE

HEADQUARTERS, SOUTHERN REGION

Memphis, TN 38166

o u r r e f .- 201:MG: sc D A T E : August 17, 1972

S U B J E C T :: Equal Employment Opportunity Complaint

T O :

Mr, Harold L. Sylvester

4327 Worrell Drive

Houston, TX 77045

This will acknowledge receipt of your letter dated August 7, 1972,

regarding a complaint of discrimination.

This matter will be given attention as expeditiously as possible.

Office of Equal Employment Compliance

Appendix A

p. 0. Bex 2641

Houston, Texas

August 7, 1972

Equal Employment Opportunity Officer TJ» S. Postal Service

Southern Hegional Office

llemphis, Texmessee 38166

Pear Sir:

I am filing a formal complaint of discrimination against the

Houston, Texas Post Office in regard to job assignments, quality

step increase and superior accomplishment award.

1. Harold L. Sylvester, 4327 Worrell, Houston, Texas 77045

2. Title and Level - Poreman of Hails, Level 9

3* Specific Action or Situation complained of - (a) job

assignments, (b) quality step increase and (c) superior accomplishment award.

4. Pate of Alleged act of discrimination - June 26, 1972.

5* Postmaster George J. Poitevent and his administrative Personnel.

6. Type of discrimination - Race.

7* I have been discriminated against by the Houston, Texas

Post Office Personnel in regards to job assignments.

Also, I have not received a quality step increase or

superior accomplishment award despite my outstanding performance as foreman of mails.

8. Pate of final interview with the Equal Employment Opportunity Counselor July 28. 1972.

I will be represented by Mr. Charles Ballard of N. A. P. P. E.

Respectfully yours,

Harold L. Sylvester

Poreman of Hails, Tour III

t s - 2

1̂ 327 Worrell

Houston, Texas 7 7 ^ 5 June 76, 1972

Mr. H duc.rd I . ..d ir.cnd

K.r.n. F.r. ic ‘ * ? i:;t

1*.01 ?r:Ui*:l In

General Post Office

Houston, Texas 77913

Dear* 31;-:

I, Hanoi;’ L. Sylvester, have been discriminated against by too

Houston, ^exas Post Office in rcrerds to Job assignments.

Also, I have not received a

accomplishr-ent award despite

foremen of mails,

q veliiy step inor>. e s c

wy cutntending ps.vfc:

I would like an appointment with you at the earliest possible

date to discuss ti.is matter.

Respectfully,

Harold L. Sylvester

Foronnr ojT

G.rV'. - Toiv 3

T~> e-|

,4c/(T * 1

CJt-C. /nA ■

M l

U 0 9,*. a*~

2003 Blodgett

Houston, Texas 7700/*

August 2, 1972

Eoual Employment Office

Attention E E 0 Coordinator

Headquarters, Southern Region

U. S. Postal Service

Memphis, Tennessee 38166

Dear Sir:

I*m filing a formal complaint of discrimination becquse of Race.

1. Rayford V. Pryor, Jr., 2003 Blodgett, Houston, Texas 77COA.

2. Supervisor PS-8

3. Specific Complaint-Piscriminated against in regard to promotion,

training, Superior Performance awards, evaluation, and-job assign

ments.

4. Alle ged act of discrimination June 23, 1972.

4-A A continuing obstinate dogma of white Supremacy, Nepotism,

and Black Tokenism. _

$. Houston, Texas Postmaster George J. Poitevent's promotional,

assignment and, evaluation personnel.

6. Type of discrimination alleged-Race and Color.

7. I have been and I am now being discriminated against by the Postal

Service in Houston, Texas because of my race in regard to training,

Superior Performance awards, evaluation, promotions, and job

assignments. I have also been harrassed for making inequities

known.

8. Date of final interview with E E 0 Counselor - July 31. 19?2.

I will be represented by H. L. Sylvester and N. A. A. C. P . s f r Z S

Resp edt f ■ullyxyours,

Foreman Mails, Tour 111

G P 0, Houston, Texas

2003 Blodgett Street

Houston, Texas 77004

June 27, 1972

Mr. Edward L. Edmond

EEO Specialist

401 Franklin Avenue

General Post Office

Houston, Texas 77013

Dear Sir:

I have been and I am now being discriminated against by the Postal

Service at Houston, Texas, because of my race and color in regard

to training, Superior Performance Awards, evaluations, promotions, and

job assignments. I am also being harassed and punished for making

inequities known.

I am requesting that you investigate this situation and take action

to cause correction of these Postal Service Violations.

V. Pryor, Jr.

Foreman, Mails

GP0, Houston, Texas