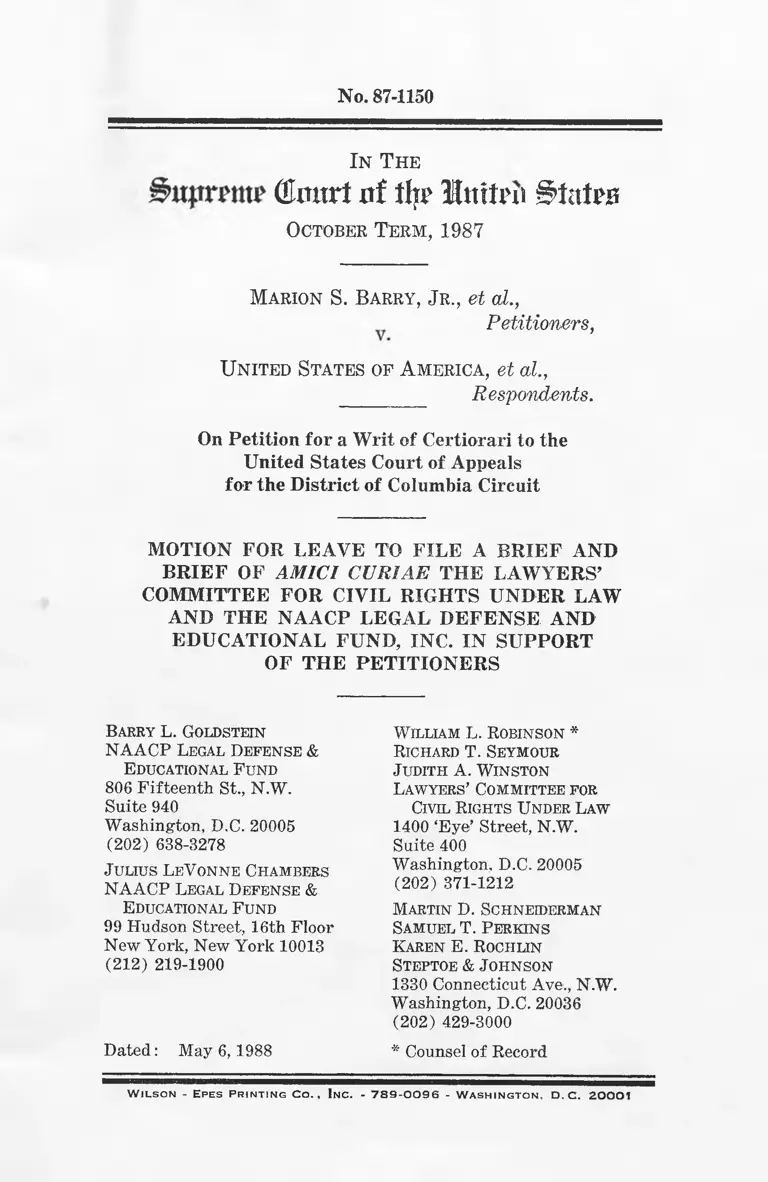

Barry v. United States Motion for Leave to File a Brief and Brief of Amici Curiae The Lawyer's Committee for Civil Rights Under Law and the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund in Support of the Petitioners

Public Court Documents

May 6, 1988

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Barry v. United States Motion for Leave to File a Brief and Brief of Amici Curiae The Lawyer's Committee for Civil Rights Under Law and the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund in Support of the Petitioners, 1988. a7847696-be9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/7f70aaee-b750-4a7b-ab23-5f64cda32be1/barry-v-united-states-motion-for-leave-to-file-a-brief-and-brief-of-amici-curiae-the-lawyers-committee-for-civil-rights-under-law-and-the-naacp-legal-defense-and-educational-fund-in-support-of-the-petitioners. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

No. 87-1150

I n T h e

(Hmtrt of % Inttrii § ta ta

October T e r m , 1987

Marion S. Barry , J r ., et al.,

Petitioners,

U n it ed States of A m erica , et al.,

_______ Respondents.

On Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the

United States Court of Appeals

for the District of Columbia Circuit

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE A BRIEF AND

BRIEF OF AMICI CURIAE THE LAWYERS’

COMMITTEE FOR CIVIL RIGHTS UNDER LAW

AND THE NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND

EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC. IN SUPPORT

OF THE PETITIONERS

Barry L. Goldstein

NAACP Legal Defense &

William L. Robinson *

Richard T. Seymour

J udith A. Winston

Lawyers’ Committee for

E ducational F und

806 Fifteenth St., N.W.

Suite 940

Washington, D.C. 20005

(202) 638-3278

Civil Rights Under Law

1400 ‘Eye’ Street, N.W.

Suite 400

Washington. D.C. 20005

(202) 371-1212J ulius LeVonne Chambers

NAACP Legal Defense &

Educational F und Martin D. Schneiderman

Samuel T. Perkins

Karen E. Rochlin

Steptoe & J ohnson

1330 Connecticut Ave., N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20036

(202) 429-3000

99 Hudson Street, 16th Floor

New York, New York 10013

(212) 219-1900

Dated: May 6,1988 * Counsel of Record

W i l s o n - E p e s P r i n t i n g C o . , In c . - 7 8 9 - 0 0 9 6 - W a s h i n g t o n , D . C . 2 0 0 0 1

I n T h e

i&tpran? (Emtrt at % luitrft

October Th rm , 1987

No. 87-1150

M arion S. Barry , J r ., et al.,

Petitioners,

U n ited States o f A m erica , et al.,

Respondents.

On Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the

United States Court of Appeals

for the District of Columbia Circuit

MOTION OF AMICI CURIAE THE LAWYERS’

COMMITTEE FOR CIVIL RIGHTS UNDER LAW

AND THE NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND

EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC. FOR LEAVE TO

FILE A BRIEF IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONERS

The Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law

and the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund,

Inc. (Amici) respectfully move for leave to file the at

tached Brief as Amici Curiae. This motion is being filed

under Rule 36.1.1 Petitioners and Respondent The United

States of America have consented to the filing of this

brief and their letters of consent have been filed with the

Clerk of the Court. Respondents Marvin K. Hammon,

et al., have not consented.

1 The brief is timely filed under Rule 36.1 since it has been

submitted within the time allowed for filing the brief in opposition

to the Petition for Writ of Certiorari.

Amici are civil rights organizations representing mem

bers of a variety of disadvantaged groups to secure their

civil and constitutional rights. Many of the employment

discrimination problems which amici have attempted to

resolve could have been cured without jurdicial inter

vention if the employers involved had implemented rea

sonable affirmative action plans, such as the plan at issue

in this matter. Amici and their clients have a direct in

terest in securing a rule of law encouraging employers

throughout the nation to resolve their own problems

through voluntary remedies so that resort to litigation

will be unnecessary.

This case involves a question which continues to trouble

lower federal courts and employers nationwide, namely,

what circumstances will support an employer’s voluntary

efforts to remedy discrimination. The decision by the

court of appeals, which prevents the Petitioners from

correcting the present discriminatory impact of an in

valid test, conflicts with instructions from this Court de

signed to encourage voluntary remedies for discrimina

tion while protecting employers from otherwise inevit

able litigation, either from minorities or from non

minorities alleging reverse discrimination. The results of

the decsion below conflict with those of other federal

courts, while threatening to increase the need for court-

ordered remedies for discrimination. The resolution of

this case will significantly affect the employment prac

tices of public and private employers nationwide, and

not just those of the parties to the litigation below.

Amici have represented a large number of discrimina

tion plaintiffs in the District of Columbia and nation

wide, and are thus able to present factual information

and legal analysis that will demonstrate the larger im

portance and far-reaching consequences of the decision

issued in this case. Amici were granted leave to appear

as amid below, and at the invitation of the district court

participated in the briefing and argument of many of

the key issues below.

For these reasons, leave to file the attached amici

curiae brief should be granted.

Respectfully submitted,

Barry L. Goldstein

NAACP Legal Defense &

E ducational Fund

806 Fifteenth St., N.W.

Suite 940

Washington, D.C. 20005

(202) 638-3278

J ulius LeYonne Chambers

NAACP Legal Defense &

Educational F und

99 Hudson Street, 16th Floor

New York, New York 10013

(212) 219-1900

Dated: May 6,1988

William L. Robinson *

Richard T. Seymour

J udith A. Winston

Lawyers’ Committee for

Civil Rights Under Law

1400 ‘Eye’ Street, N.W.

Suite 400

Washington, D.C. 20005

(202) 371-1212

Martin D. Schneiderman

Samuel T. Perkins

Karen E. Rochlin

Steptoe & J ohnson

1330 Connecticut Ave., N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20036

(202) 429-3000

* Counsel of Record

QUESTION PRESENTED

Whether an employer may voluntarily follow a tem

porary affirmative action plan in order to avoid illegal

discrimination caused by a non-job-related selection sys

tem which disproportionately limits job opportunities for

minorities.

(i)

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

QUESTION PRESENTED ............................................. i

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ........................................... iv

INTEREST OF AMICI ........ ...... .... ........................ ..... 1

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT ............................ 2

ARGUMENT

I. THIS CASE PRESENTS QUESTIONS AND

CONFLICTS WHICH ARE OF NATIONAL

IMPORTANCE ....... 3

A. The Dilemma Which the DCFD Sought to

Resolve Through Its AAP Continues to Per

plex Lower Federal Courts and Employers

Nationwide....... ........ 3

B. By Adopting Inapplicable Standards and Re

quiring a Factual Predicate Unrelated to the

Invalid Hiring Test, the Court of Appeals

Has Departed from Other Federal Authori

ties and Has Exacerbated a Dilemma Which

Merits Review By This Court ........................ 6

C. Because the DCFD’s Plan Meets Even the

Most Demanding Factual Predicate for Vol

untary Affirmative Action, Additional Re

view is Necessary ___ _____ ____________ 12

II. THE DECISION BELOW, LIMITING THE

AVAILABILITY OF VOLUNTARY AFFIRM

ATIVE ACTION AND CONFLICTING WITH

OTHER FEDERAL AUTHORITIES, WILL

HAVE RAMIFICATIONS EXTENDING BE

YOND THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA ......... 16

CONCLUSION ____________ _____ ___ _________ _ 19

APPENDIX................................................. ....... ....... . la

(iii)

IV

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

CASES Page

Berkman v. City of New York, 580 F. Supp. 226

(E.D.N.Y. 1983), aff’d without op., 755 F.2d

913 (2d Cir. 1985) ....... ...................... .................. 17

Berkman v. City of New York, 705 F.2d 584 (2d

Cir. 1983) ................. 11

Berkman v. City of New York, 536 F. Supp. 177

(E.D.N.Y. 1982), aff’d, 705 F.2d 584 (2d Cir.

1983) ........... 17,18

Bushey v. New York State Civil Serv. Comm’n, 733

F.2d 220 (2d Cir. 1984), cert, denied, 469 U.S.

1117 (1985).................................... ......... ............. 11

Firefighters Institute v. City of St. Louis, 588 F.2d

235 (8th Cir. 1978), cert, denied, 443 U.S. 904

(1979) ....... 11

Firefighters Local Union No. 1 7 8 v. Stotts, 467

U.S. 561 (1984) ............. 9

Fullilove v. Klutznick, 448 U.S. 448 (1980) ........... 8

Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424 (1971)—. 13

Guardians Ass’n of the N.Y. Police Dep’t v. Civil

Serv. Comm’n, 630 F.2d 79 (2d Cir. 1980), cert.

denied, 452 U.S. 940 (1981) ____________ _ 17

Hazelwood School District v. United States, 433

U.S. 299 (1977) ______ ________ _______ ____ 7-8

Janowiak v. Corporate City of South Bend, 836

F.2d 1034 (7th Cir. 1984) _______ _____ _____ 14

Johnson v. Transportation Agency, Santa Clara

County, Cal., 107 S. Ct. 1442 (1987).......8, 11, 12,13, 15

Kirkland v. New York State Dep’t of Correctional

Services, 628 F.2d 796 (2d Cir. 1980), cert, de

nied, 450 U.S. 980 (1981) ............ ........ .......... ..... 16

Local No. 93, Int’l Assoc, of Firefighters v. City of

Cleveland, 106 S.Ct. 3063 (1986) ................. ..... 8,10

Local 28 of the Sheet Metal Workers Int’l Assoc, v.

EEOC, 106 S. Ct. 3019 (1986)............ .............. 8, 13,14

Marks v. United States, 430 U.S. 188 (1977) ____ 14

NAACP v. Seibels, 14 Fair Empl. Prac. Cas.

(BNA) 670 (N.D. Ala. 1977), aff’d in part, rev’d

in part, 616 F.2d 812 (5th Cir.), cert, denied, 449

U.S. 1061 (1980) ........... ....... ............... ..... ......... 11,18

V

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES—Continued

Page

Oburn v. Shapp, 393 F. Supp. 561 (E.D. Pa.), aff’d,

521 F.2d 142 (3d Cir. 1975).............................. .. 11, 17

Payne v. Travenol Laboratories, Inc., 673 F.2d 798

(5th Cir.), cert, denied, 459 U.S. 1038 (1982)..... 8

Pennsylvania v. O’Neill, 348 F. Supp. 1084 (E.D.

Pa. 1972), aff’d in part, vacated in part, 473 F.2d

1029 (3d Cir. 1973) (enbane) (per curiam)....... 17-18

Pennsylvania v. Rizzo, 13 Fair Empl. Prac. Cas.

(BNA) 1475 (E.D. Pa. 1975), aff’d in part, ap

peal dismissed in part, 530 F.2d 501 (3d Cir.),

cert, denied, 426 U.S. 921 (1976) ........ ............ 11, 16,18

Reed v. Lucas, 11 Fair Empl. Prac. Cas. (BNA)

153 (E.D. Mich. 1975) _____ ______ ______ _ 18

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Educ., 402

U.S. 1 (1971) ................... ................... ................ 8

United States v. City of Buffalo, 609 F. Supp. 1252

(W.D.N.Y.), aff’d sub nom. United States v.

NAACP, 779 F.2d 881 (2d Cir. 1985), cert, de

nied, 106 S. Ct. 3333 (1986) ........................ ........ 16

United States v. City of Chicago, 663 F.2d 1354

(7th Cir. 1981) (en banc) ................ ...... ........... 11

United States v. County of Fairfax, 629 F.2d 932

(4th Cir. 1980), cert, denied, 449 U.S. 1078

(1981) ................. - .................................................. 8

United States v. Paradise, 107 S. Ct. 1053 (1987) ..8, 9,10

United Steelworkers v. Weber, 443 U.S. 193

(1979) ____ _______ _________ _____ -............... 8,9,15

University of Cal. Regents v. Bakke, 438 U.S. 265

(1978) .................. .................................................. 8

Vulcan Soc’y v. City of New York, 96 F.R.D. 626

(S.D.N.Y. 1983) ............. ........... ..... ............ .... . 18

Vulcan Soc’y v. Fire Dep’t of White Plains, 505

F. Supp. 955 (S.D.N.Y. 1981)_______________ 6

Wygant v. Jackson Bd. of Educ., 476 U.S. 267

(1986) ................................... ................... ..8, 9,14, 15, 16

VI

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES—Continued

STATUTES AND REGULATIONS Page

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-16 (1982) ................................. 18

Pub. L. No. 97-91, 95 Stat. 1182 (Dec. 4,1981) ___ 5

Pub. L. No. 98-473, 98 Stat. 1937 (Oct. 12, 1984).. 5

28 C.F.R. § 50.14 (1987) ..........................................3,11,17

29 C.F.R. § 1608 (1987) ............. ............................. 10,17

MISCELLANEOUS

44 Fed. Reg. 4,422 (1979) ................. ...................... . 10

Rutherglen & Ortiz, Affirmative Action Under the

Constitution and Title VII: From Confusion to

Convergence, 35 U.C.L.A. L. Rev. 467 (1988).— 9

Schnapper, The Varieties of Numerical Remedies,

39 Stan. L. Rev. 851 (1987)....... ......... ............... 6

United States Dep’t of Commerce, Bureau of The

Census, Statistical Abstract of the United States

1987 ......................................................................... 19

United States Office of Personnel Management,

Federal Civilian Workforce Statistics, Biennial

Report of Employment by Georgraphic Area

(Dec. 31, 1986)....................................................... 19

Washington Post, Feb. 26, 1988, C l ...................... 5

In T he

Ihtfjratt? (Emrrt of tip luttPii States

October Term , 1987

No. 87-1150

Marion S. Barry, J r., et al. ,

Petitioners, v. ’

United States of America, et al. ,

Respondents.

On Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the

United States Court of Appeals

for the District of Columbia Circuit

BRIEF OF AMICI CURIAE THE LAWYERS’

COMMITTEE FOR CIVIL RIGHTS UNDER LAW AND

THE NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL

FUND, INC. IN SUPPORT OF THE PETITIONERS

INTEREST OF AMICI

The Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law

is a nationwide civil rights organization with local offices

in Washington, Philadelphia, Boston, Chicago, Jackson,

Denver, Los Angeles, and San Francisco. It was formed

by leaders of the American Bar in 1963, at the request

of President Kennedy, to provide legal representation to

blacks who were being deprived of their civil rights. Over

the years, the national office of the Lawyers’ Committee

and its local offices have represented the interests of

blacks, Hispanics, and women in many hundreds of class

actions in the fields of employment discrimination, voting

rights, equalization of municipal services, and school de-

2

segregation. Well over a thousand members of the private

bar, including former Attorneys General, former presi

dents of the American Bar Association, and other leading

lawyers, have assisted in these efforts.

The NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund,

Inc. is a nonprofit corporation whose principal purpose is

to secure the civil and constitutional rights of minorities

through litigation and education. For more than forty

years, its attorneys have represented plaintiffs in thou

sands of civil rights cases, including many significant

cases before this Court.

Many of the employment discrimination cases brought

by amici are against employers who could have cured

their problems without judicial intervention if they had

developed and implemented reasonable affirmative action

plans such as the plan at issue in the case at bar. Amici

and their clients have a direct interest in securing a

rule of law encouraging employers to address and resolve

their own problems, so that the filing of enforcement law

suits will be unnecessary.

Amici were granted leave to appear as amid below,

and at the invitation of the district court participated in

the briefing and argument on many of the key issues

below.

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

The decisions below have failed to recognize that the

affirmative action plan (AAP) of the District of Colum

bia Fire Department (DCFD), far from being an ab

stract quota program developed in a vacuum, is a meas

ured and reasonable response to avoid immediate liability

arising from an invalid test with an unlawful discrimina

tory impact on blacks which would otherwise occur. The

examination’s disparate impact and lack of validity are a

matter of record and have been stipulated to by the par

ties to the litigation. By overlooking this critical feature

of the DCFD Plan, the court of appeals has not only mis-

3

applied the rulings of this Court, but would force the

DCFD to choose between liability to minorities for dis

crimination or not hiring firefighters until a valid selec

tion procedure can be developed. Adjusting for the ad

mitted disparate impact of the DCFD’s hiring test was

entirely overlooked as the basis for justifying the DCFD’s

Plan.

The court of appeals so focused on its assessment of

past discrimination that it overlooked the AAP’s critical

function of avoiding present discrimination. In so doing,

the court of appeals created a situation in which other

employers are prevented from taking appropriate steps

to prevent present liability. This result contradicts the

directions of the Justice Department’s own Uniform

Guidelines On Employee Selection Procedures, see 28

CFR § 50.14 (1987), and results reached by other fed

eral courts. Because of the importance of this issue, the

devastating effect the court of appeals’ decision will have

on voluntary remedies to avoid discrimination, and the

conflict with the results of other federal court decisions

and federal guidelines, the Petition for Certiorari should

be granted.

ARGUMENT

I. THIS CASE PRESENTS QUESTIONS AND CON

FLICT'S WHICH ARE OF NATIONAL IMPOR

TANCE

A. The Dilemma Which the DCFD Sought to Resolve

Through Its AAP Continues to Perplex Lower

Federal Courts and Employers Nationwide

To appreciate the difficulty that the decisions below

pose for other employers faced with similar problems of

validation, this Court need consider only a few critical

facts. As a matter of record, it is undisputed that the

DCFD’s hiring examination (the Firefighters Selection

Test or FST) has an adverse discriminatory impact on

blacks. The parties to this litigation have stipulated to

4

this disparate impact.1 Even before initiation of this

litigation, a hearing examiner for the District of Colum

bia’s Office of Human Rights (OHR) found that the 1980

version of the FST and the virtually identical 1984 ver

sion both had severe adverse impacts on blacks without

being job-related. Petition at 6, n.3. These findings,

made after fifty days of trial, were affirmed on admini

strative appeal. All of the parties to the present litiga

tion, including the Justice Department, stipulated to these

findings.2 The trial court below once again found that

selecting job applicants in order of their ranked FST

scores resulted in an adverse racial impact. Hammon v.

Barry, 606 F. Supp1. 1082, 1088 (D.D.C. 1985) ; Peti

tioner’s Appendix (P. App.) at 134-35a. What this

means is that rank-ordered hiring causes black appli

cants to wait far longer than whites before they receive

offers, even though the rank-ordering system is not a

valid predictor of job performance. As explained by

amici during oral argument before the trial court,

twenty-nine percent of the DCFD’s white hires were em

ployed within a year of the 1980 test. Within that same

period, only one percent of the black hires were em

ployed. Of those applicants forced to wait two or three

years before employment, only twenty-five percent were

white while forty-eight percent, nearly twice the percen

tage, were black.®

To correct the FST’s ongoing adverse impact, the

DC-FD made a reasonable attempt to eliminate this dis

crimination, and consequent exposure to liability under

Title VII, through its AAP. Indeed, all of the parties,

1 Statement of Stipulated Material Facts, Hammon v. Barry,

Nos. 84-0903, 85-0782, 85-0797 (D.D.C.) at (ft 17, 20, and 22. The

pertinent pages of this Statement are included in the Appendix to

this Brief (App.) at la-4a.

2 Id. at H 18, App. at 2a.

8 March 23, 1985 Hearing Transcript at 103-106. Pertinent pages

from this Transcript have been appended to this Brief. App

at 5a-8a.

5

including Respondent The United States of America,

stipulated that the portions of the AAP directed towards

hiring were “designed solely to eliminate the racial and

sexual disparity which would exist if the examination

results were used in rank order.” 4 At issue here is the

intractable dilemma which the DCFD now faces without

this plan. The FST remains the DCFD’s only currently

available hiring examination, and the District of Colum

bia needs additional firefighters now.® See Petition at

19-21 (emphasizing the current lack of any alternatives

to the FST). Since the District has not been able to hire

firefighters through random selection,'6 it has employed

them according to their rank order based on FST scores.

Yet rank-ordered selection is the primary cause of the

F'ST’s severely adverse racial impact. Since blacks re

ceive generally lower FST scores than whites, black ap

plicants have been precluded from employment entirely

or have faced years of delay before the DCFD could hire

them, even though the FST itself has no demonstrated

relevance for job performance.

The AAP was adopted to adjust for and eliminate pre

cisely these harsh discriminatory consequences from se

lecting applicants by rank order from the FST. Without

the AAP, the DCFD confronts an unenviable choice. It

may address the urgent need for additional firefighters

on the basis of rank-ordered selection and confront lia

bility to minority applicants, or it may adopt the equally

unsatisfactory alternative of not hiring at all, regardless

of safety or other concerns, until a valid alternative to

the FST can be developed. For all of those affected by

4 Statement of Stipulated Material Facts, f[ 30, App. at 3a

(emphasis added).

5 For an account of the increasingly urgent need for hiring more

firefighters, and the costs of not being able to do so, see Washington

Post, Feb. 26, 1988, at Cl.

6 See, e.g., Pub. L. No, 97-91, 95 Stat. 1182 (Dec. 4, 1981);

Pub. L. No. 98-473, 98 Stat. 1837 (Oct. 12, 1984) (enacting H.R.

5899) ; Petition at 20, 20 n.9.

6

this dilemma, including minority as well as nonminority

applicants and the DCFD itself, the most reasonable solu

tion continues to be use of the AAP, which directs that

new classes of firefighters contain the same percentage of

minorities as the approximate percentage of minorities

who pass the FST.

Once they acknowledge or become liable for the adverse

impact of a hiring procedure, employers like the DCFD

have frequently urged federal courts to create or approve

temporary affirmative action measures until alternative

procedures can be developed.7 Indeed, in at least one in

stance, an employer and a predominately white union

preferred to neutralize the adverse impact of a test and

retain it permanently.8 Because courts and employers

continue to be vexed by the need to respond effectively

to hiring procedures that have an adverse impact on

disadvantaged groups, the present case warrants review

by this Court.

B. By Adopting Inapplicable Standards and Requiring

a Factual Predicate Unrelated to the Invalid Hir

ing Test, the Court of Appeals Has Departed from

Other Federal Authorities and Has Exacerbated a

Dilemma Which Merits Review By This Court

Despite the DCFD’s need to remedy the adverse effects

of the FST or face continued charges of discrimination,

the court below struck down the AAP. By so doing, on

the grounds that the DCFD lacked the appropriate fac

tual predicate for affirmative action,® the court below has

undermined the ability of public or private employers to

voluntarily avoid imminent racial discrimination.

7 See generally Schnapper, The Varieties of Numerical Remedies,

39 Stan. L. Rev. 851, 889 (1987); infra cases cited at 11, note 24.

8 Vulcan Soc’y v. Fire Dep’t of White Plains, 505 F. Supp. 955,

960-61 (S.D.N.Y. 1981).

® Hammon v. Barry, 826 F.2d 73, 78-81 (D.C. Cir. 1987) ; P.

App. at 90a-92a; 813 F.2d at 426, P. App. at 31a.

7

Over dissent, the majority below first ruled that to

comply with the requirements of Title VII, the AAP must

respond to a “manifest racial imbalance” in the DCFD’s

workforce, despite the record and the trial court’s find

ings that the FST had a disparate impact. The court

below then managed to find that such an imbalance did

not exist. Amici concur with Petitioners that such a

“finding” by the court of appeals is riddled with errors

of law for the reasons the Petitioners have addressed,

including improper statistical comparisons, confusion of

the standards required by Title VII and the Constitu

tion, reversal of the appropriate burdens of proof, and

most disturbing of all, the appellate court’s unwarranted

assumption of the trial court’s role as finder of fact, re

sulting in conclusions unsupported by any record evi

dence.10

Yet the heart of the error below, and the source of

this case’s fundamental importance, is that any analysis

for “manifest imbalance” within the DCFD’s workforce

was unnecessary.11 Indeed, the facts of this case support

ing the AAP are far more compelling than a “manifest

imbalance” test. The AAP was needed not just to adjust

for an imbalance, but to avoid imminent discrimination.

110 For example, the majority below regarded observations that

the AAP adopted quotas merely to refleet the racial composition

of applicants passing the test as “drawn out of the ether.” 826

F.2d at 79 n .ll, P. App. a t 93a. Had the majority considered

stipulations to this effect made by all of the parties before the trial

court, however, the source and binding effect for these observations

would have been clear. See Statement of Stipulated Material Facts,

HIT 24, 30, 32; App. at 3a-4a.

1:1 Even if such analysis were necessary, the proper statistical

comparison would reveal a manifest imbalance. The proper com

parison is not that adopted by the court below, comparing the

DCFD’s workforce with the labor force of the entire Washington

Metropolitan area, see 826 F.2d at 77, P. App. at 88a. Instead, the

proper comparison is between the DCFD’s work force and its appli

cant pool. See Hazelwood School District v. United States, 433

8

If evidence of present discrimination will not create a

factual predicate supporting affirmative action, then the

decisions of this Court permitting race-conscious reme

dial measures are without meaning.12 Nothing in any

of the rulings of this Court requires an employer, public

or private, to convict itself of liability under Title VII or

the Constitution before undertaking affirmative action.

The anomaly of requiring employers to remedy discrimi

nation while denying them a reasonable means to avoid

it in the first place is absurd. In fact, this Court has

never accepted that an employer must choose between

liability to nonminorities if it fails to prove its own dis

crimination, or liability to minorities after such discrim

ination has been proven. See Johnson, 107 S. Ct. at 1451,

n.8; Wygant, 476 U.S. at 290-91 (O’Connor, J., concur

ring) ; Weber, 443 U.S. at 210-11 (Blackmun, J., con-

U.S. 299, 508 n.13 (1977) ; Payne v. Travenol Laboratories Inc.,

673 F.2d 798, 823-24 (5th Cir.), cert, denied, 459 U.S. 1038 (1982) ;

United States v. County of Fairfax, 629 F.2d 932, 940 (4th Cir.

1980), cert, denied, 449 U.S. 1078 (1981). The court of appeals

further muddied its statistical comparison by focusing only on new

hires employed after 1981; however, for the years 1983 and 1984

of this comparison, the DCFD was hiring in compliance with rec

ommendations of the OHR which were meant to correct an im

balance in the DCFD’s workforce. Finally, the court of appeals

ignored the readily manifest, imbalance of white applicants hired

shortly after passing the test and black applicants facing years of

delay before hire. When proper comparisons are made which do not

dilute the percentage of blacks in the appropriate labor market or

applicant group, a manifest imbalance is apparent.

12 Cf. Johnson v. Transportation Agency, Santa Clara County,

Cal., 107 S. Ct. 1442 (1987) ; United States v. Paradise, 107 S. Ct.

1053, 1064 (1987) ; Local No. 93, In t’l Assoc, of Firefighters v.

City of Cleveland, 106 S. Ct. 3063 (1986); Local 28 of the Sheet

Metals Workers’ Int’l Assoc, v. EEOC, 106 S. Ct. 3019, 3049, 3052

(1986) ; Wygant v. Jackson Board of Educ,, 476 U.S. 267 (1986) ;

Fullilove v. Klutznick, 448 U.S. 448 (1980) ; United Steelworkers

v. Weber, 443 U.S. 193 (1979) ; University of Cal. Regents v.

Bakke, 438 U.S. 265 (1978) ; Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd.

of Educ., 402 U.S. 1 (1971).

9

curring). The Court has also recognized that employers

adopt voluntary remedial measures to avoid claims for

backpay or reduce claims of disparate impact. See Fire

fighters Local Union No. 1784 v. Stotts, 467 U.S. 561,

589 (1984) (O’Connor, J., concurring) ; Weber, 443 U.S.

193, 211 (Blackmun, J., concurring).

Development of a valid alternative to the FST will be

costly and may take years. This Court, and Respondents

themselves, have recognized that validation of hiring pro

cedures is both expensive and time-consuming. See, e.g.,

Paradise, 107 S. Ct. at 1068 n.21 (noting “how difficult

it is to develop and implement selection procedures that

satisfy the rigorous standards of the ‘Uniform Guide

lines’ because The validation of selection procedures is

an expensive and time-consuming process usually extend

ing over several years’ ” ) (quoting The Brief for the

United States, 24-25, n.13).13 As noted above, unless and

until a valid test is developed, the DCFD may avoid lia

bility under Title VII through the use of an AAP or by

not hiring at all. The court of appeals, however, has

eliminated the first option for the DCFD. Indeed, no

employer will be able to meet the requirements of the

decision below for voluntary affirmative action if the

virtual certainty of discrimination claims is not by itself

sufficient to warrant remedial measures. To insist upon

such requirements places voluntary compliance with Title

VII in jeopardy. Weber, 443 U.S. at 210 (Blackmun, J.,

concurring); Wygant, 476 U.S. at 290-91 (O’Connor, J.,

concurring).

Moreover, abundant legal authority already exists

which instructs employers to do exactly what the DCFD

13 See also Uniform Guidelines on Employee Selection Procedures,

28 C.F.R. § 50.14 (1985) ; Rutherglen & Ortiz, Affirmative Action

Under the Constitution and Title VII: From Confusion to Con

vergence, 35 U.C.L.A. L. Rev. 467 at 508 (1988) (suggesting that

the expense of validation makes affirmative action the only viable

option employers have for avoiding liability for claims of disparate

impact).

10

has attempted. E.g., Paradise, 107 S. Ct. 1053, 1059,

(quoting NAACP v. Allen, 493 F.2d 614, 618 (5th Cir.

1974)) (“The . . . use of unvalidated selection procedures

that disproportionately excluded blacks precluded any

argument that ‘quota hiring produces unconstitutional

“reverse” discrimination, or a lowering of employment

standards, or the appointment of less or unqualified per

sons.’ ” ). Also in the more restricted context of court-

ordered affirmative action, the Supreme Court has held

that interim hiring or promotional goals may be neces

sary:

pending the development of nondiscriminatory hiring

or promotion procedures. In these cases, the use of

numerical goals provides a compromise between two

unacceptable alternatives : an outright ban on hiring

and promotions, or continued use of a discriminatory

selection procedure.

Sheet Metal Workers, 106 S. Ct. at 3037.

Such authority is nothing new. The EEOC Guidelines

on “Affirmative Action Appropriate Under Title VII of

the Civil Rights Act of 1964, As Amended,” 29 CFR

§ 1608 (1987),14 direct employers to engage in a “self

analysis” to determine, inter alia, if there is a “reason

able basis” for concluding that employment practices

“ [h]ave or tend to have an adverse effect on employment

opportunities of . . . groups whose employment . . . oppor

tunities have been artificially limited.” Id. § 1608.4(b).

If so, as is the case with the DCFD, the employer may

take reasonable action “includ[iing] goals and timetables

. . . [and] the adoption of practices which will eliminate

the actual or potential adverse impact . . . .” 15

14 These guidelines were first issued in 44 Fed. Reg. 4,422 (1979).

15 29 CFR § 1608.4(c) (1987). These guidelines “constitute a

body of experience and informed judgment to which courts and

litigants may properly resort for guidance.” Local Number 93,

11

Similarly, numerous court decisions have held that af

firmative action is appropriate to remedy the adverse im

pact of an invalid hiring procedure. See, e.g., Bushey v.

New York State Civil Serv. Comrn’n, 733 F.2d 220, 226-

27 (2d Cir. 1984), cert, denied, 469 U.S. 1117 (1985);

Berkman v. City of New York, 705 F.2d 584, 595-98 (2d

Cir. 1983), affirming 536 F. Supp. 177, 216-18 (E.D.N.Y.

1982); United States v. City of Chicago, 663 F.2d 1354,

1361-62 (7th Oir. 1981) (en banc); Firefighters Insti

tute v. City of St. Louis, 588 F.2d 235, 242 (8th Cir.

1978) (“We, therefore, direct the District Court, on re

mand, to enter an injunctive decree which requires that

assignments to acting fire captain positions reflect a fifty

percent black ratio as far as is practicable, pending the

development of a valid examination.” ), cert, denied, 443

U.S. 904 (1979); Pennsylvania v. Rizzo, 13 Fair Empl.

Prac. Cas. (BNA) 1475, 1481 (E.D. Pa. 1975), aff’d in

part, appeal dismissed in part, 530 F.2d 501 (3d Cir.),

cert, denied, 426 U.S. 921 (1976); Obum v. Shapp, 393

F. Supp. 561, 574-75 (E.D. Pa.), aff’d, 521 F.2d 142

(3d Cir. 1975), NAACP v. Seibels, 14 Fair Empl. Prac.

Cas. (BNA) 670, 686-87 (N.D. Ala. 1977), aff’d in

part, rev’d in part, 616 F.2d 812 (5th Cir.), cert, denied,

494 U.S. 1061 (1980); see also Uniform Guidelines on

Employee Selection Procedures, 28 CFR § 50.14. It is

difficult to imagine how the DCFD could not justify its

AAP in view of the various authorities instructing it

to correct the adverse impact of its test, including the

Uniform Guidelines adopted by the Justice Department

itself. Indeed, the result of the decision below would ap

pear to be in direct conflict with the results of the

authorities just cited, further warranting review by this

Court.

In t’l Assoc, of Firefighters v. City of Cleveland, 106 S. Ct. 3063,

3073 (1986) (quoting General Electric v. Gilbert, 429 U.S. 125,

142 (1976)). See also 28 CFR § 50.14(6) (1987) (use of alternate

selection procedures to eliminate adverse impact).

12

C. Because the DCFD’s Plan Meets Even the Most

Demanding Factual Predicate for Voluntary Affirm

ative Action, Additional Review is Necessary

In Johnson v. Transportation Agency, Santa Clara

County, California, 107 S. Ct. 1442 (1987), this Court

addressed the minimum requirements under Title VII for

a factual predicate supporting a public employer’s vol

untary affirmative action plan. Johnson concerned ap

plication of a county transportation agency’s affirmative

action plan which addressed the complete absence of fe

male employees in 238 skilled craft worker positions. Id.

at 1446. Unlike the DCFD, the agency had not been con

fronted with charges of discrimination prior to adoption

of its plan, nor had the agency stipulated that it had used

invalid selection procedures with a discriminatory ad

verse impact. The agency had not been charged with

discrimination, and the record in Johnson did not contain

prior findings of any type of discrimination, including

findings of adverse impact. The facts in Johnson which

supported affirmative action were thus less compelling

than those at issue in the present case, which involves

imminent discrimination with resumption of rank-

ordered hiring under the FST. See id. at 1451-52, 1452-

53 n.10.

The requirement of a “manifest imbalance” is closer to

the minimum which a public employer need show for its

affirmative action plan to meet the factual predicate re

quired by Title VII.16 As the Court reasoned in Johnson,

citing its earlier decision in Weber, “an employer seeking

to justify the adoption of a plan need not point to its own

prior discriminatory practices, nor even to evidence of

an ‘arguable violation’ on its part.” Id. at 1451. A case

like the present one exceeds the requirements of Johnson,

18 Moreover, as the strength of other evidence indicating dis

crimination increases, an employer need not rely as heavily, if at

all, on statistical evidence in order to voluntarily adopt affirmative

action. See Johnson, 107 S. Ct. at 1453 n .ll.

13

since use of the invalid FST w-ith the resulting disparate

racial impact amounts to an actual violation of Title

VII. See, e.g., Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424

(1971). For a court to engage in statistical comparisons

concerning proof of a manifest imbalance when an on

going disparate impact has already been established is

at best an academic exercise, and at worst a w'aste of

time for the court and the parties before it.17

Even under the arguably more stringent18 factual

predicate required by the Constitution, the AAP with

stands scrutiny.19 While this Court has not yet fully de-

17 Similarly, the focus on the DCFD’s prior discrimination in the

decision below was unnecessary. While Johnson associated the re

quirement of manifest imbalance with its appearance in a “tradi

tionally segregated job category,” it did so only so that “sex or

race will be taken into account in a manner consistent with Title

A ll’s purpose of eliminating the effects of employment discrimina

tion.” Id. at 1452. While much has been made below of the sig

nificance of the DCFD’s historical discrimination, such historical

analysis should be unnecessary in a case like the present one involv

ing the current adverse impact of an invalid test. This current

adverse impact demonstrates that the AAP was consistent with

Title VII’s purpose of eliminating discrimination. See Sheet Metal

Workers, 106 S. Ct. at 3049 (“The purpose of affirmative action

is . . . to prevent discrimination in the future.”).

118 See Johnson, 107 S. Ct. 1442 at 1450 n.6 (“The fact that a

public employer must also satisfy the Constitution does not negate

the fact that the statutory prohibition with which the employer

must contend was not intended to extend as far as that of the

Constitution.”) .

19 Petitioners maintain that this case rests entirely on Title VII.

Petition for Writ of Certiorari at 12, n.6. While this matter is

open to dispute, compare Hammon v. Barry, 826 F.2d 73, 76

(D.C. Cir. 1987), P. App. at 80a; with 826 F.2d at 81-82, P. App.

at 98a, 826 F.2d at 88, P. App. at 113a, and 813 F.2d at 420, P.

App. at 17a, Petitioners and Amici both appear to agree that the

opinions below have confused constitutional requirements with those

of Title VII. The importance of these issues, the need for clarity

between the two standards, and the impact this matter will have on

14

fined these requirements,20 one method of meeting the

constitutional predicate is with “convincing” or “suf

ficient” evidence of prior discrimination. Wygant v. Jack-

son Bd. of Educ., 476 U.S. at 277-78 (Powell, J., writ

ing for the plurality) at 286 (O’Connor, J., concurring).

In Wygant, this Court reviewed a challenge to terms in a

public school district’s collective bargaining agreement

governing layoffs. The plurality struck down this plan in

part because it was burdensome and not narrowly tail

ored; however, five Justices agreed that the school dis

trict had offered no evidence of prior discrimination.

Justice O’Connor’s concurring opinion articulated what

factual predicate established the constitutionally required

compelling interest in race-conscious remedial action.21

She wrote:

The Court is in agreement that, whatever the formu

lation employed, remedying past or present racial

discrimination by a state actor is a sufficiently

weighty state interest to warrant the remedial use of

a carefully constructed affirmative action program.

This remedial purpose need not be accompanied by

contemporaneous findings of actual discrimination

to be accepted as legitimate as long as the public

actor has a firm basis for believing that remedial

action is required.

interpreting- constitutional requirements for affirmative action,

highlight the importance of this matter and further warrant grant

ing Petitioners’ application for review.

2'° See, e.g., Sheet Metal Workers, 106 S. Ct. at 3052.

21 Her concurrence has been described as “critical” to an under

standing of these requirements. Janowiak v. Corporate City of

South Bend, 836 F.2d 1034, 1041 (7th Cir. 1984) ; see also Marks

v. United States, 430 U.S. 188, 193 (1977) (when no single rationale

explaining the result enjoys the assent of five Justices, the holding

of the Court may be viewed as the position taken by those who

concurred on the narrowest grounds).

15

Id. at 286 (emphasis added). Ultimately, she wrote, non

minority challengers to an affirmative action plan bear

the burden “of persuading the Court that the [public

employer’s] evidence did not support an inference of prior

discrimination, and thus a remedial purpose.” Id. at 293

(emphasis added). In other words, under the Constitu

tion an affirmative action plan will be sustained and its

factual predicate will be established where the public

employer provides evidence of its reasonable belief that

remedial action was needed.

These requirements could not apply more easily to the

present case. The OHR had recommended that the DCFD

adopt an affirmative action plan, which it did under a

consent order. The discriminatory impact resulting from

use of the FST, as noted above, had been established

through adjudicative findings and stipulations. Federal

regulations adopted by the Justice Department and the

Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, as well as

guidelines from federal court decisions in other juris

dictions, directed that prior to test validation, temporary

affirmative action to correct precisely this kind of ad

verse impact was appropriate and even necessary. The

DCFD had ample reaon to believe in its need to remedy

discriminatory use of the FST. As a matter of simple

logic, if the DCFD’s voluntary plan was based on a fac

tual predicate meeting constitutional requirements, it

must have met the requirements of Title VII.02

2:2 In evaluating the factual predicate for affirmative action, this

Court has also emphasized that preferential remedies for discrim

ination must not unduly trammel the interests of nonminorities.

See, e.g., Johnson, 107 S. Ct. at 1451; Wygant, 476 U.S. at 282-84;

Weber, 443 U.S. at 208. In the present case, this requirement could

not be more fully met, since the DCFD’s Plan does not impose any

burden on nonminorities. The AAP merely re-orders selection to

eliminate the disparate impact of rank-oredered selection from the

FST. Since the FST is an invalid predictor of job performance,

nonminorities cannot say that they have been deprived of anything

simply because they are hired out of rank order. See Kirkland v.

New York State Dep’t of Correctional Services, 628 F.2d 796, 798

16

While claiming to strike the DCFD’s Plan under anal

ysis based solely on Title VII, the court of appeals ap

plied a standard equal if not greater in strength to that

required by the Constitution. Yet not all employers, in

cluding those in the private sector, are governed by con

stitutional standards. Accordingly, one additional con

sequence of the decision below is to effectively provide

reverse discrimination plaintiffs with a previously un

available and unintended cause of action. Review by this

Court is therefore necessary not only to prevent confu

sion of the standards imposed by this Court and other

authorities, but to restore the balance under Title VII of

rights and remedies for minorities and nonminorities

alike.

II. THE DECISION BELOW, LIMITING THE AVAIL

ABILITY OF VOLUNTARY AFFIRMATIVE AC

TION AND CONFLICTING WITH OTHER FED

ERAL AUTHORITIES, WILL HAVE RAMIFICA

TIONS EXTENDING BEYOND THE DISTRICT OF

COLUMBIA

“The question presented in this case is too important

to leave in its present unsatisfactory state in this circuit

(2d Cir. 1980) (adding points to minority scores on invalid test

with adverse impact “does not bump white candidates because of

their race but rather reranks their [estimated] predicted perform

ance”), cert, denied, 450 U.S. 980 (1981) ; United States v. City of

Buffalo, 609 F. Supp. 1252, 1254 (W.D.N.Y.) (“Since selection pro

cedures used by the City have not yet been shown to be accurate

predictors of job performance, it is, at this juncture, somewhat

presumptuous to say that an injustice is done every time a candi

date is selected out of rank order.”), ajf’d sub nom. United States

v. NAACP, 779 F.2d 881 (2d Cir. 1985), cert, denied, 106 S. Ct.

3333 (1986); Rizzo, 13, Fair Empl. Prac. Cas. (BNA) at 1481

(“if a person appears in a certain position on an eligibility list

prepared in violation of the law, his lawful position must give way

to the lawful requirement to avoid discriminatory promotions”).

Perhaps most significantly, the DCFD’s Plan did not address the

context of layoffs, where legitimate expectations of employment

have developed, but instead addressed new hires, who would not have

such expectations. This distinction can be critical to evaluating the

17

or elsewhere.” S3 So wrote five dissenting judges below,

protesting the reversal of the appellate court, by a bare

majority, of its decision to hear this case en banc. This

reversal, however, issued with virtually no explanation,

does not alter the exceptional importance of this case.

As a result of the decisions below, government employers

may no longer remedy the adverse impact of an invalid

hiring examination. Such a result defies the rulings of

this Court while placing government employers in an

untenable position, forcing them to choose between lia

bility to minorities for discrimination or liability to non-

minorities for reverse discrimination. Indeed, in view of

the efforts by the court of appeals to limit its ruling to

Title VII, this same unaccpetable dilemma will apply

equally to private employers as well.

Moreover, the majority below has created an addi

tional dilemma for employers attempting to follow con

tradictory federal authorities. The federal government

itself has instructed employers to adopt goals and time

tables to remedy employment practices with an adverse

impact on disadvantaged groups. 29 CFR § 1608.4(b)

(1987). Through the Uniform Guidelines, even the Jus

tice Department had adopted such directions. 28 CFR

§ 50.14 (1987). Numerous federal courts, including

courts of appeals, have accepted the use of affirmative

action to remedy the discriminatory impact of invalid

tests.®4 In contrast, the Court of Appeals for the District

burden of affirmative action on nonminorities. See Wygant, 476

U.S. at 282.

23 Supplemental Brief in Support of Petition for Certiorari,

Appendix at 3a.

124 See Berkman v. City of New York, 580 F. Supp. 226 (E.D.N.Y.

1983), aff’d without op., 755 F.2d 913 (2d Cir. 1985) ; Guardians

Ass’n of the N.Y. Police Dep’t v. Civil Serv. Comm’n, 630 F.2d 79,

108-09 (2d Cir. 1980), cert, denied, 452 U.S. 940 (1981) ; Berkman

v. City of New York, 536 F. Supp. 177, 216 (E.D.N.Y. 1982), aff’d,

705 F.2d 584 (2d Cir. 1983) ; Oburn v. Shapp, 393 F. Supp. 561,'

574 (E.D. Pa.), aff d, 521 F.2d 142 (3d Cir. 1975); Pennsylvania

v. O’Neill, 348 F. Supp. 1084, 1103-04 (E.D. Pa. 1972), aff’d in

18

of Columbia Circuit now stands alone in its failure to rec

ognize the need to correct imminent discrimination from

use of a test with a discriminatory impact through the

use of a temporary affirmative action plan.

Employers hiring nationwide will be especially bur

dened by such conflicting messages. For example, Title

VII now applies with equal force to federal employers®5

As federal employers in the District of Columbia attempt

to develop policies in compliance with the paradoxical

mandates of the decisions below, it stands to reason that

such policies may take effect throughout the country in

regional offices of federal agencies.06 Without the inter

part, vacated in part, 473 F.2d 1029 (3d Cir. 1973) (en banc)

(per curiam) (proportional hiring provision affirmed by equally

divided court) ; Vulcan Soc’y v. City of New York, 96 F.R.D. 626,

628-29 (S.D.N.Y. 1983) ; Reed v. Lucas, 11 Fair Empl. Prac. Cas.

(BNA) 153, 155-56 (E.D. Mich. 1975) ; NAACP v. Seibels, 14

Fair Empl. Prac. Cas (BNA) 670, 686-87 (N.D. Ala. 1977), aff’d

in part, rev’d in part, 616 F.2d 812 (5th Cir.), cert, denied, 449

U.S. 1061 (1980) ; Pennsylvania v. Rizzo, 13 Fair Empl. Prac. Cas.

(BNA) 1475, 1481 (E.D. Pa. 1974), aff’d in part, appeal dismissed

in part, 530 F.2d 501 (3d Cir.), cert, denied, 426 U.S. 921 (1976).

For public agencies such as police or fire departments, the ability

to hire is often vital to public safety, and courts have recognized

this concern, which is of no less importance in the present case,

in upholding affirmative action plans. See Berkman v. City of New

York, 536 F. Supp. 177, 216 (E.D.N.Y. 1982) (“to freeze all

appointments [to the Fire Department] may present a hazardous

situation to the citizens of the community”) (quoting Vulcan Soc’y

v. Civil Serv. Comm’n, 360 F. Supp. 1265, 1278 (S.D.N.Y.)), aff’d

in part, 490 F.2d 387 (2d Cir. 1973)), aff’d, 705 F.2d 584 (2d Cir.

1983); Reed, 11 Fair Empl. Prac. Cas. (BNA) at 155 (“Any injunc

tion which caused continuing vacancies in the . . . [Sheriff’s] De

partment would jeopardize . . . efficient operation.”).

25 See 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-16 (1982).

26 While the District of Columbia is the center of the federal

government, and the source of many agency-wide policies, the en

tire Washington Metropolitan area contains only the second largest

number of federal civilian employees. California ranks first as

19

vention of this Court, the conflicts described above will

only grow more burdensome for federal or similarly sit

uated private employers where other jurisdictions are

more lenient in their requirements for affirmative action.

Should other jurisdictions follow the court below, how

ever, the ability for all employers to remedy discrimina

tion will only suffer more consistent impairment.

CONCLUSION

For the reasons stated above, the Petition for Writ of

Certiorari should be granted.

Respectfully submitted,

Barry L. Goldstein

NAACP Legal Defense &

E ducational F und

806 Fifteenth St., N.W.

Suite 940

Washington, D.C. 20005

(202) 638-3278

J ulius LeVonne Chambers

NAACP Legal Defense &

E ducational F und

99 Hudson Street, 16th Floor

New York, New York 10013

(212) 219-1900

Dated: May 6,1988

William L. Robinson *

Richard T. Seymour

J udith A. Winston

Lawyers’ Committee for

Civil Rights Under Law

1400 ‘Eye’ Street, N.W.

Suite 400

Washington, D.C. 20005

(202) 371-1212

Martin D. Schneiderman

Samuel T. Perkins

Karen E. Rochlin

Steptoe & J ohnson

1330 Connecticut Ave., N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20036

(202) 429-3000

* Counsel of Record

the jurisdiction with the highest number of such employees. See

United States Dep’t of Commerce, Bureau of the Census, Statistical

Abstract of the United States 1987, at 310; United States Office of

Personnel Management, Federal Civilian Workforce Statistics,

Biennial Report of Employment by Geographic Area 4-5 (Dec 31

1986). ‘ ’

APPEN DIX

la

APPENDIX

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA

Civil Action No. 84-0903

Marvin K. Hammon, et al,

Plaintiffs,

v.

Marion S. Barry, J r., et al.,

Defendants.

Civil Action No. 85-0782

Kevin Michael Byrne, et al,

Plaintiffs,

v.

Theodore R. Coleman, et al,

Defendants.

Civil Action No. 85-0797

U nited States of America,

Plaintiff,

v.

The District of Columbia, et al,

Defendants.

STATEMENT OF STIPULATED MATERIAL FACTS

* * * *

2a

16. Components of the 1984 test were substantially

the same as the corresponding components of the 1980

test; but one component, following oral directions, was

revised and substantially modified.

17. Both the 1980 test and the 1984 test had an ad

verse impact upon Black applicants as more fully de

scribed below.

The 1980 Examination

18. After an evidentiary hearing, the Hearing Ex

aminer found that the entry level examination admin

istered on November 22, 1980 had an adverse impact

upon Black applicants and was not a valid predictor of

successful job performance as required by the Uniform

Guidelines on Employee Selection Procedures.

19. There were 974 test takers, of whom 724 (74.35%)

were Black and 207 (21.5%) were White. There were

959 passers, of whom 713 (74.35%) were Black and 205

(21.5%) were White.

20. The hearing examiner’s finding of adverse impact

is based upon the rank order use of the examination, be

cause such use resulted in a substantially different rate

of selection of Black and White applicants.

21. The hearing examiner found that if selections

were made in rank order the following would have re

sulted :

for the first 100 names on the eligible list the selection

rate for Blacks would be 3.6% and for Whites 34%;

for the first 200 names on the eligible list the selection

rate for Blacks would be 11.2% and for Whites 54%;

for the first 300 names on the eligible list the selection

rate for Blacks would be 20.8% and for Whites 69.4%.

22. The District of Columbia accepted these and other

findings of the Hearing Examiner concerning adverse

3a

impact and job relatedness, and does not now contend

that the written examination either had no adverse im

pact or is valid and job related.

The 19 8U Examination

23. The 1984 firefighters examination was adminis

tered in March, April and July 1984.

24. There were 1,626 test takers, of whom 1,050

(64.6%) were Black, 492 (30.3%) were White and 84

(5.1%) Hispanic and others; 1,384 persons passed the

exam, of whom 830 (60%) were Black, 486 (35.1%)

were White, 33 (2.4%) were Hispanic and 35 (2.5%)

were others, 1287 (93%) were males and 96 (6.9%)

were female.

# -ifr * *

29. The District of Columbia has agreed to validate

the examination in accordance with the May 23, 1984

consent decree in the Hammon case but, to date, has not

done so. In particular, neither the District of Columbia

nor any other party to these consolidated cases has de

veloped validity evidence meeting the standards of the

psychological profession showing that those who score

higher on the test are more likely to perform better on

the job than those who score lower.

Proposed Selection Procedures From the 1981* Eligibility

List Using the District of Columbia Affirmative

Action. Plan

30. The AAP requires the use of multiple certificates

to select firefighters and is designed solely to eliminate

the racial and sexual disparity which would exist if the

examination results were used in rank order.

31. Under the Plan, the District of Columbia Office

of Personnel is to generate 12 certificates, each consist

ing of approximately 120 candidates, from separate lists

of White males, White females, Black males, Black fe-

4a

males, Hispanic males, and other males based upon the

candidate’s score on the written examination (plus vet

eran’s preference points).

32. Each certificate, described in paragraph 31 above,

is to have the following racial and sexual proportion of

candidates: 60% Black, 2.4;% Hispanic, 35.1% White,

2.6% other, 93% male, and 7% female.

* • * * * ■

DATED: March 14, 1985

/s / Inez Smith Reid

Inez Smith Reid

Corporation Counsel, D.C.

J ohn H. Suda, Principal

Deputy Corporation Counsel,

D.C.

Martin L. Grossman

Deputy Corporation Counsel,

D.C.

Sandra J efferson Grannum

Assistant Corporation Counsel,

D.C.

District Building, Room 316

Washington, D.C. 20004

(202) 727-6303

Attorneys for Defendants

Marion S. Barry, et al.

/ s / Joan A. Burt

J oan A. Burt

310 Oklahoma Avenue, N.E.

Suite 4

Washington, D.C. 20002

(202) 388-0549

Karl W. Carter, J r.

1850 K Street, N.W.

Suite 880

Washington, D.C. 20036

(202) 331-2034

Attorneys for

Marvin K. Hammon, et al.,

Plaintiffs in No. 84-0903

Respectfully submitted,

Wm . Bradford Reynolds

Assistant Attorney General

/ s / By: Richard S. Ugelow

David L. Rose

Richard S. Ugelow

Attorneys

Department of Justice

Civil Rights Division

Washington, D.C. 20530

(202) 633-3415

Attorneys for United States

of America, Plaintiff in

No. 85-0797

/s / George H. Cohen

George H. Cohen

Robert M. Weinberg

J eremiah A. Collins

Mady Gilson

Bredhoff & Kaiser

1000 Connecticut Avenue, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20036

(202) 833-9340

Attorneys for Kevin Michael

Byrne, et al., Plaintiffs in

No. 85-0782

5a

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA

Civil Action No. 84-0903

Marvin K. Hammon, et al,

vs Plaintiffs,

The District of Columbia, et al,

_______ Defendants.

Civil Action No. 85-0782

Kevin Michael Byrne, et al,

vs Plaintiffs,

Theodore R. Coleman, et al,

_______ Defendants.

Civil Action No. 85-0797

United States of America,

vg Plaintiff,

The District of Columbia, et al,

_ _ _ _ _ _ Defendants.

Courtroom No. 11

Washington, D.C.

Saturday, March 23, 1985

The above-entitled matter came on for hearing in open

court on Cross-Motions for Summary Judgment before

The Honorable CHARLES R. RICHEY, United States

District Judge, commencing at 10:13 a.m.

* * * *

6a

[103] Now, maybe they haven’t sufficiently thought

through their approach, but there’s—I think there’s a

serious Article III question, frankly, whether the Justice

Department’s challenge on the hiring test can properly

be before the Court, but I have to go through the process

one at a time.

On the factual question, to set the predicate for this,

the Department of Justice reply memorandum says at

page 7, note 3, that there’s no need for concern over hir

ing, because, since 1981, 66 percent of the hires have

been black; since 1982, 73 percent of the hires have been

black.

What they overlook is, first, that there was adverse

impact on those who never got hired. Our figure there

is 2.67 standard deviations away from what you would

expect by chance, and I’ll supply those figures to the

Court, also.

Second, they overlook the fact that the black candidates

by and large had to wait years before they got hired.

Those who were—of all the whites who were hired, 29

percent were hired in the same year they took the test,

within one year; one percent of blacks, a 29-fold differ

ence in the percentage of those who were hired the same

year.

Among those who had to wait two or three years after

[104] they took the test to be hired; that’s true of 25

percent of the whites who ultimately got hired; it’s true

of 48 percent of the blacks who ultimately got hired.

Now, Justice says again, this is no problem, having

to wait to be hired. Put aside the fact that the Byrne

plaintiffs include some people who have apparently just

a couple of months of delay in reaching their promotional

ranks, and that’s enough for them to be here in court,

it’s enough for the Justice Department to come in to

champion their interests, but the years of delay for

blacks are no problem, says the Justice Department, be

cause everyone got retroactive seniority dates, so that

anybody who did get hired from the 1980 test—put aside

7a

the people who never got hired—but those who did get

hired have the same seniority date.

What about back pay? Years’ worth of loss of earn

ings is a fairly significant problem, and the hearing

examiner’s recommendation makes clear—this is on page

93, the asterisked footnote at the bottom of the page—

that the retroactive seniority date has no connection with

back pay, nobody is receiving any back pay, so there as

a major problem there that Justice did not see fit to get

involved in.

THE COURT: Well, maybe they’d like to ask the

Congress of the United States to raise the federal pay

ment, so that Ms. Reid and her colleagues, Mr. Reid and

Mr. Suda and Mr. Grossman and the others, can pay

these people their back [105] pay and front pay.

MR. SEYMOUR: But it is against the background—

THE COURT: I don’t want the taxpayers to have to

do it.

MR. SEYMOUR: It is against this background of a

clear violation of Title VII on the 1980 test that what

the District is proposing to do on the 1984 test has to be

weighed.

The Justice Department’s own regulations allow the

District a choice. They don’t mention this in their pa

pers, but they allow the District a choice. You can either

validate and show it’s valid, or you can come up with

some change in the selection procedures that is guaran

teed to eliminate the adverse impact. In the additional

citations of authority we’ve provided today, we’ve pro

vided copies of the questions and answers to clarify the

uniform guidelines., and of the uinform guidelines pro

vision that make that clear.

* * * *