Order; Correspondence from Boyd to Judge Thompson

Public Court Documents

October 7, 1986 - October 9, 1986

7 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Dillard v. Crenshaw County Hardbacks. Order; Correspondence from Boyd to Judge Thompson, 1986. 590e03b3-b7d8-ef11-a730-7c1e5247dfc0. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/7f74bf9c-0471-464b-a4f2-d831e7bd87de/order-correspondence-from-boyd-to-judge-thompson. Accessed February 05, 2026.

Copied!

% ® Da fix. fe

7, rail rig LCF

°K Re. / L g )/ / JO (o

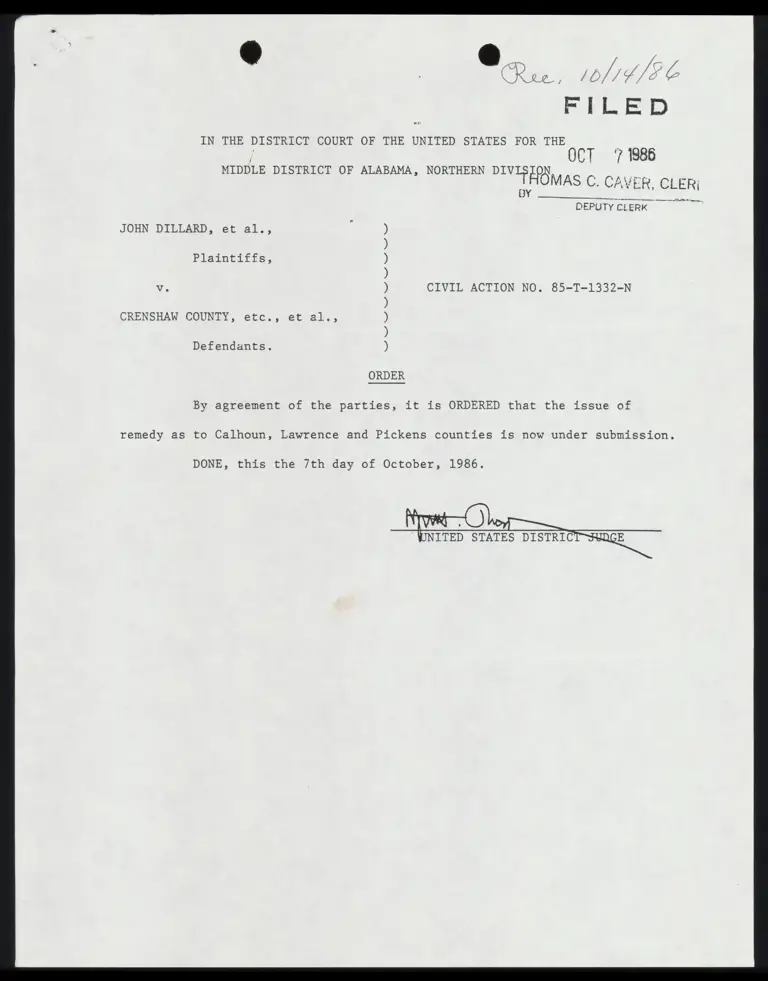

FTILED

IN THE DISTRICT COURT OF THE UNITED STATES FOR THE

: OCT 71986

MIDDLE DISTRICT OF ALABAMA, NORTHERN PIV IN MAS C. C

2 AVER, CLER;

By oa RIE

DEPUTY CLERK

JOHN DILLARD, et al., ! )

)

Plaintiffs, )

)

V. ) CIVIL ACTION NO. 85-T-1332-=N

)

CRENSHAW COUNTY, etc., et al., )

)

Defendants. )

ORDER

By agreement of the parties, it is ORDERED that the issue of

remedy as to Calhoun, Lawrence and Pickens counties is now under submission.

DONE, this the 7th day of October, 1986.

A

"YNITED STATES inn

/

a % Rie 0/15] LE

BALCH & BINGHAM

ATTORNEYS AND COUNSELORS

S EASON BALCH JOHN RICHARD CARRIGAN THE WINTER BUILDING

JOHN BINGHAM WILLIAM E. SHANKS, UR POST OFFICE BOX 78 2 DEXTER AVENUE

SCHUYLER A BAKER T DWIGHT Susan COURT SOUARE

EA wr AN THORNE SEE tN i MONTGOMERY, ALABAMA 3810! MONTGOMERY, ALABAMA 36.2<

MAURY D. SMITH RALPH F MacDONALD. Il TELECOPIER 205. 269-0.28

WILLIAM J. WARD STEVEN G. MSKINNEY (20%) B34-8500

ROBERT M COLLINS STEVEN F CASEY

HAROLD A. BOWRON. JR MALCOLM N CARMICHAEL BIRMINGHAM OFFICES CAREY J. CHITWOOD RICHARD L L PEARSON

A. KEY FOSTER. JR. BRIAN D HBTs STR

JOHN S. BOWMAN JAMES A. BRADFORD rg dh Ee vy THOMAS W. THAGARD, JR DAN H. MCCRARY I

CHARLES M. CROOK EDWARD B. PARKER, 11 BIRMINGHAM, ALABAMA 3527

STERLING G. CULPEPPER, UR WILLIAM P COBB. || 20%) 25-8100

EDWARD S. ALLEN WILLIAM S. WRIGHT TELECOPIER 1205) 252-0 WARREN H. GOODWYN JOHN J. COLEMAN, Ii

ROBERT A. BUETTNER PATRICK H. LUCAS AND

JAMES O. SPENCER. JR. JOHN F. MANDY "

H. HAMPTON BOL ROBERT L. SHI ;

C. WILLIAM GLADDEN, JR. ALAN T. ROGERS Octob 1 9 FINANCIAL SENTER

MICHAEL L. EDWARDS M. STANFORD BLANTON ctober 9 ’ 86 B05 NCIITE TDD. ees

MARSHALL TIMBERLAKE ELLEN G. RAY iO5 NOR? gol STREE

WALTER M. BEALE, JR. KEITH B. NORMAN CE BOX 306

RODNEY O. MUNDY JAMES M. PROCTOR, II BIRMINGHAM, ALABAMA 3527

JAMES F. HUGHEY, JR. T. KURT MILLER 205) 251-8100

S. EASON BALCH, JR. J. THOMAS FRANCIS, JR. TELECOPIER (205i 252-1074

JOHN P. SCOTT. JR. ROY W. SCHOLL. lil

S. ALLEN BAKER, JR. SUSAN B. BEVILL

J. FOSTER CLARK PAUL A. BRANTLEY OF COUNSEL

STANLEY M. BROCK PATRICIA A. MCGEE

RANDOLPH H. LANIER JONATHAN S. HARBUCK D. PAUL JONES, JR

DAVID R. BOYD DAVIS G. REESE EDWIN W. FINCH, iI

The Honorable Myron H. Thompson HAND DELIVERED

United States District Judge

Federal Courthouse

Montgomery, Alabama 36104

Re: Dillard, et al. v. Crenshaw County, et al.

Civil Action No. 85-T-1332-N

Dear Judge Thompson:

Now that the Court is considering the remedial matters

relating to Lawrence County, we take this opportunity to make

some limited observations and argument, and specifically to res-

pond to some of the matters addressed in Mr. Menefee's recently-

filed memorandum.

As a preliminary matter, the Court should be aware of cert-

ain recent developments which will impact on the scheduling of

the special election to be held pursuant to the Court's earlier

orders. As the Court is aware, the parties originally agreed

that the special election would be held during the fall of this

year. However, it has now become clear that, at least in Law-

rence County, it will simply not be possible to conduct the

election on that schedule. The impossibility results from the

time required for the mechanics of identifying voters to dist-

ricts, notifying the voters, qualifying candidates, and assorted

October 9, 1986

Re: Dillard, et al. v. Crenshaw County, et al.

Page 2

kindred problems. In an effort to work our way through these

problems, we have met with Mr. Menefee and are well under way

with the preparation of an alternate schedule which will be pre-

sented to the Court in due course for approval, with the consent

of all parties.

As the Court also knows, we are awaiting word from the Vot-

ing Section of the Department of Justice regarding Lawrence

County's Section 5 submission. We expect to hear from the Attor-

ney General in the next two weeks or so (although it could be

longer since it was necessary for Lawrence County to make a sup-

plemental submission), and we respectfully suggest that the Court

might reasonably decide to defer any ruling on the Lawrence

County situation for a short while, in order to give the Attorney

General a little while longer to make a decision. Since it

appears that the Lawrence County elections will not take place

until perhaps January of 1987 -- assuming approval by the Court

of the parties' joint proposal -- it does not appear that any

harm would be caused by the Court waiting a little longer before

ruling on the Lawrence County matter.

Regardless of what the Court decides about going forward

with a ruling, there are some substantive matters that we feel

need to be addressed. With respect to the five (5) single-member

districts proposed by the County, it is clear that the Court

should give its approval. Disregarding, for the time being, the

unpopulated Airport-Industrial Park complex area, we ask the

October 9, 1986

Re: Dillard, et al. v. Crenshaw County, et al.

Page 3

Court to examine the competing plans. First, the one predomi-

nantly black district proposed by the County is identical to the

one predominantly black district proposed by the Plaintiffs. The

County's demographer and the Plaintiffs' demographer shared and

agreed upon data in constructing this district. With respect to

the other four (4) districts, there is simply nothing wrong with

the County's proposal. Indeed, Mr. Menefee concedes that "there

is ... no real dispute as to the location of the lines.” (Brief

p. 14). Plaintiffs' passing comments about their proposed dist-

ricts being more contiguous and following census boundaries more

1/ closely= raise superficial points which are hardly grounds

authorizing this Court to select the Plaintiffs' plan over the

County's plan, when the County's plan is conceded to be racially

fair, and, equally as advantageous to blacks, as the Plaintiffs’

plan. We urge the Court to review the deposition of the County's

1/ Unless the compactness, or lack thereof, of districts

somehow has an impermissible purpose, effect, or result, the

County's preferences should be honored. For example, what may

appear to the eye to be "more contiguous" may actually upset

communities of interest far more than some other, perhaps less

compact, plan. This is simply a quagmire which this Court should

avoid. The same is true regarding the "issue" of preservation of

census boundaries. As made clear in the deposition of Charles R.

Clark, it was necessary to secure "split" data from the Census

Bureau to create a racially-fair plan which also met one person-

one vote considerations. In other words, several enumeration

districts had to be split. The Plaintiffs accomplished the same

thing by conducting some supplemental house counts. The Plain-

tiffs' plan no more honors traditional enumeration district lines

than does the County's, and, even if it did, any difference would

be de minimis. In this regard, please see pages 30-34 and 37-40

of the Clark deposition.

October 9, 1986

Re: Dillard, et al. v. Crenshaw County, et al.

Page 4

demographer, Mr. Clark, in reaching its conclusions regarding the

fairness and reasonableness of the County's proposal.

The only real point of contention regarding the districts is

the placement of the unpopulated Airport-Industrial Park area.

In the Plaintiffs' plan, this area is included in the majority

black District 1, but is included in the majority white District

2 in the County's plan. The Plaintiffs' explanation of the rea-

sons for this difference is factually inaccurate, misleading, and

totally unsupported by any evidence before this Court. In truth,

the County's decision to put the complex in District 2 had noth-

ing to do with race and is entirely reasonable.

First, it is not true that all the residents immediately

surrounding the Airport-Industrial Park site are black. In fact,

the residents on three sides are mostly white, and some of the

residents to the north are white. The undisputed evidence before

this Court clearly establishes this fact. (Please see the

excerpts from the deposition of Charles R. Clark which are

attached hereto.) The area north of the site, which is mostly

black, was included in the predominantly black district in order

to increase its black population, but the predominantly white

areas east, west, and south of the site were not, for obvious

reasons.

There was nothing illogical or discriminatory about includ-

ing the Airport-Industrial Park site in District 2 rather than

in District 1. The site is owned jointly by the County and the

October 9, 1986

Re: Dillard, et al. v. Crenshaw County, et al.

Page 5

City of Courtland, which is in proposed District 2. The County

simply believed it was most appropriate to put the unpopulated

site in the same district as Courtland. There were no impermis-

sible considerations -- racially motivated or otherwise -- enter-

ing into this decision. The City of Courtland simply wanted to

have the airport site, of which it is a partial owner, in the

same district with the City, and the County acceded to this

wish.

We recognize that there was no trial evidence (except Mr.

Clark's testimony regarding the instructions given to him, depo.

p. 34) regarding the reason for the County's decision to locate

the complex in District 2 rather than District 1. At the same

time, there was no evidence that its placement was for any imper-

missible purpose, and the Plaintiffs' suggestion to the contrary

is simply a product of their imagination. We respectfully sug-

gest that, in the absence of any evidence of racial motivation or

discriminatory result, the Court should not tamper with the

County's proposed districts based on the placement of an unpopu-

lated area which, because of its nature, will never become popu-

lated.

With respect to the issue of the commission chairman elected

at-large, the County adopts the arguments set forth in its pre-

trial memorandum, the evidence submitted by all of the Defendants

at trial, and the memoranda submitted by the Pickens and Calhoun

County Defendants since the trial. We also ask the Court to

October 9, 1986

Re: Dillard, et al. v. Crenshaw County, et al.

Page 6

consider the matters set forth in our recent letter to the Attor-

ney General regarding the County's Section 5 submission, which is

attached hereto along with the pre-trial memorandum mentioned

above and some excerpts from the Clark deposition. We also adopt

the position set forth in that letter with respect to the

permissibility of ‘phasing in the remedial plan, rather than

requiring immediate elections in all five districts.

Summarizing, we urge the Court to approve the County's pro-

posed districts without change. If the Court were to conclude

that the Airport-Industrial Park area should be included in the

majority black district, rather than in District 2, we respect-

fully submit that the very most the Court should do would be to

order that this limited change be made, and that the County's

plan otherwise be implemented as proposed. See Upham v. Seamon,

456 U.S. 37 (1982). We emphasize that we do not believe that any

change should be ordered.

Also, we believe that the Court should approve without

change the County's proposal for a commission chairman elected

at-large, and for the phasing in of the new district system.

Respectfully submitted,

Aerio R Boyd —

David R. Boyd

DRB/jam

Enclosures