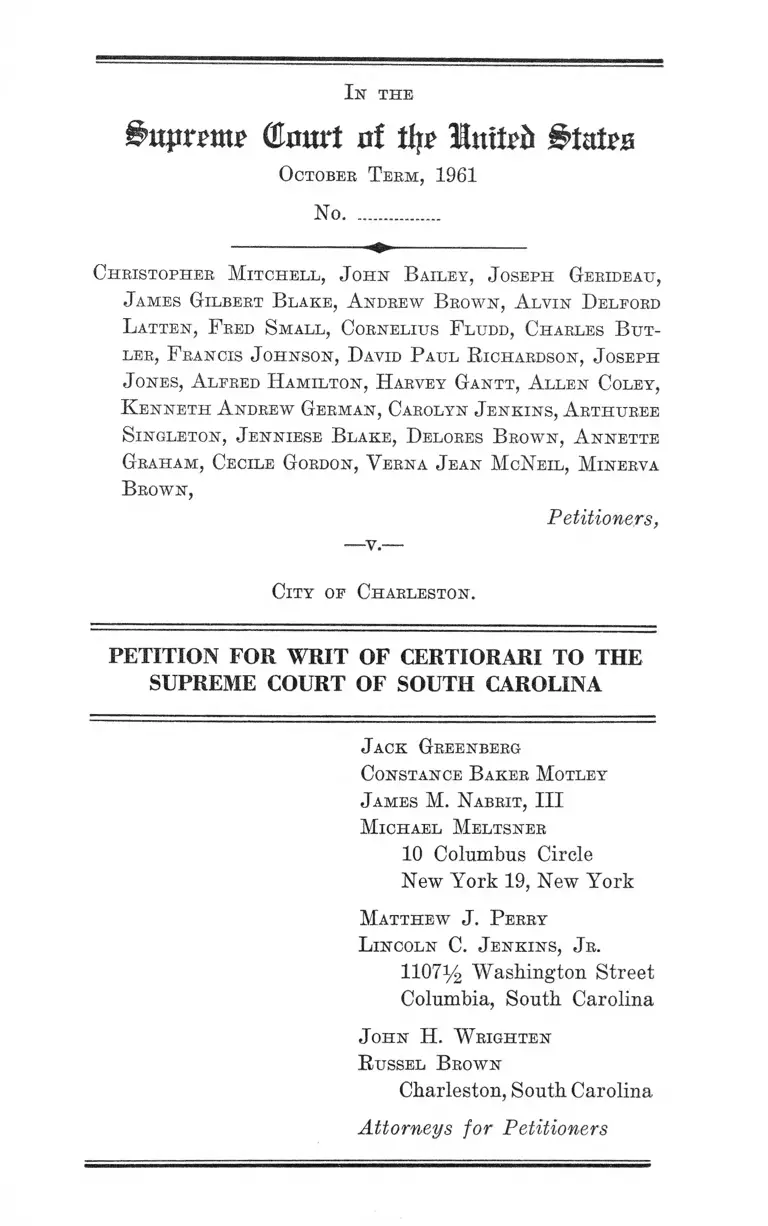

Mitchell v. City of Charleston Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court of South Carolina

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1961

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Mitchell v. City of Charleston Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court of South Carolina, 1961. 90e9cf0b-be9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/7f833573-3c00-44f1-a489-ea53756f87dd/mitchell-v-city-of-charleston-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari-to-the-supreme-court-of-south-carolina. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

I n th e

0 u|im np (Emtrt at tljp llm frii States

O ctober T er m , 1961

No.................

C h risto ph er M it c h e l l , J o h n B ailey , J oseph G erideau ,

J am es G ilbert B l a k e , A ndrew B r o w n , A lvin D elford

L a tten , F eed S m a ll , Cornelius F ludd , C harles B u t

ler , F rancis J o h n son , D avid P au l R ichardson , J oseph

J ones, A lered H a m il to n , H arvey G a n t t , A lle n C oley ,

K e n n e t h A ndrew G e r m a n , Carolyn J e n k in s , A rthu ree

S in g leto n , J en n iese B l a k e , D elores B ro w n , A n n ette

G r a h a m , C ecile G ordon, V ern a J ean M cN eil , M inerva

B r o w n ,

Petitioners,

C it y of C h arlesto n .

PETITION FOR W RIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

SUPREME COURT OF SOUTH CAROLINA

J ack G reenberg

C onstance B aker M otley

J am es M . N abrit , I I I

M ic h ael M eltsner

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

M a t t h e w J . P erry

L in co ln C. J e n k in s , J r .

HO714 Washington Street

Columbia, South Carolina

J o h n H . W righ ten

R ussel B rown

Charleston, South Carolina

Attorneys for Petitioners

I N D E X

PAGE

Citation to Opinions Below ............................................. 1

Jurisdiction ..... 2

Questions Presented ................................ 2

Statutory and Constitutional Provisions Involved .... 3

Statement ........................................................................... 3

How the Federal Questions Were Raised and Decided

Below .... ........................................................ 6

Reasons for Granting the Writ ..................... 9

I. The Criminal Statute and Warrant Applied to

Convict Petitioners Gave No Fair and Effective

Warning That Their Actions Were Prohibited;

Petitioners’ Conduct Violated No Standard Re

quired by the Plain Language of the Law or Any

Earlier Interpretation Thereof; Thereby Their

Convictions Offend the Due Process Clause of

the Fourteenth Amendment and Conflicts With

Principles Enunciated by This Court .............. 9

II. The State of South Carolina Has Enforced

Racial Discrimination Contrary to the Equal

Protection and Due Process Clauses of the

Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of

the United States ................................................ 16

C onclusion ....................................................................... 23

A ppen d ix ........... l a

Order of the Charleston County Court.................. l a

Opinion of the Supreme Court of South Carolina .. 9a

Order of Denial of Petition for Rehearing ........... 29a

11

T able op Cases

page

Boynton v. Virginia, 364 U. S. 454 ............................. 17,19

Breard v. Alexandria, 341 U. S. 622 .............................. 21

Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S. 60 ............... ....... ...... . 19

Burton v. Wilmington Parking Authority, 365 IT. S.

715 ................................................................................... 21

Cantwell v. Connecticut, 310 U. S. 296 .......................... 15

Champlin Rev. Co. v. Corporation Com. of Oklahoma,

286 U. S. 210...................... .............................................. lg

Chaplinsky v. New Hampshire, 315 IT. S. 568 ___ __ 15

City of Columbia v. Barr, et al., ------ S. C. ------ , 123

S. E. 2d 521 ............................... ................................ 0

City of Greenville v. Peterson, 122 S. E. 2d 826 (No.

750, October Term, 1961) ............... ............................. 19

Civil Rights Cases, 109 IT. S. 3 ............................... ..19, 22

District of Columbia v. John R. Thompson Co., 346

IT. S. 100 ._............ ......................................................... 20

Garner v. Louisiana, 368 U. S. 157 ..........................15, 21, 22

Herndon v. Lowry, 301 U. S. 242 .................... .......... ...13,15

Hudson County Whiter Co. v. McCarter, 209 U. S. 349 .. 22

Lanzetta v. New Jersey, 306 U. S. 451.......... ....... 11,13,14

Mapp v. Ohio, 367 IT. S. 643, 6 L. ed. 2d 108.............. . 21

Marsh v. Alabama, 326 U. S. 501..................................... 19

McBoyle v. United States, 283 U. S. 25 ..........................12,15

Monroe v. Pape, 365 U. S. 167 ......................................... 19

Munn v. Illinois, 94 U. S. 113 ..... ................................ 19

Napue v. Illinois, 360 U. S. 264 ..................................... 19

I l l

People v. King, 110 N. Y. 419, 18 N. E. 245 (1888) .... 20

Peterson, et al. v. City of Greenville (No. 750, October

Term, 1961) .......... .............................. ........................... 10

Pickett v. Kuchan, 323 111. 138, 153 N. E. 667, 49

A. L. R. 499 (1926) ............ ............................. .......... 20

Pierce v. United States, 314 U. S. 306 .......................... 11,12

Poe v. Ullman, 367 U. S. 497, 6 L. ed. 2d 989 .................. 21

Railway Mail Assn. v. Corsi, 326 IJ. S. 8 8 ...................... 20

Randolpli v. Virginia, 202 Va. 661, 119 S. E. 2d 817

(No. 248, October Term, 1961) ................................. 19

Republic Aviation Corp. v. N. L. R. B., 324 U. S. 793 .. 19

Rex v. Storr, 3 Burr. 1698 ............................................. 10

Screws v. United States, 325 U. S. 91 .......................... 19

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1 .............. ..................... 19

Shramekv. Walker, 152 S. C. 88, 149 S. E. 331............ 10

State v. Avent, 253 N. C. 580, 118 S. E. 2d 47 (No. 85,

October Term, 1961) .................................................... 19

State v. Williams, 76 S. C. 135, 56 S. C. 783 .................. 10

Thompson v. City of Louisville, 362 U. S. 19 .............. 11

Thornhill v. Alabama, 310 U. S. 88 ................................. 21

United States v. Cardiff, 344 U. S. 174.......................... 12

United States v. L. Cohen Grocery Co., 255 U. S. 81 .... 13

United States v. Weitzel, 246 U. S. 533 ......................12,13

United States v. Willow River Power Co., 324 U. S. 499 19

United States v. Wiltberger, 18 U. S. (5 Wheat.) 76 .... 12

PAGE

Western Turf Asso. v. Greenberg, 204 U. S. 359

Winters v. New York, 333 U. S. 507 .......................

. . . 20

15,16

IV

S tatutes

United States Code, Title 28, Section 1257(3) ........... 2

Code of Alabama, Title 14, §426 .................................. . 14

Compiled Laws of Alaska Ann. 1958, Cum. Supp. Vol.

Ill, §65-5-12 ...................... ........... ....................... ........ 14

Arkansas Code, §71-1803 ............ ......... ........... ............... 14

Conn. Gen. Stat. (1958 Rev.), §53-103 .......................... 14

D. C. Code, §22-3102 (Supp. VII 1956) .......................... 14

Florida Code, §821.01 .................................................... 14

Hawaii Rev. Code, §312-1 ......................................... ....... 14

Illinois Code, §38-565 ...................................................... 14

Indiana Code, §10-4506 ................................. _................. 14

Mass. Code Ann., C. 266, §120 ..................................... 14

Michigan Statutes Ann. 1954, Vol. 25, §28.820(1) ....... 14

Minnesota Statutes Ann. 1947, Vol. 40, §621.57 ........... 14

Mississippi Code, §2411 ................................................... 14

Nevada Code, §207.200 .................. ....................... ........... . 14

Ohio Code, §2909.21 ........................................................ 14

Oregon Code, §164.460 ......................... ........................... 14

S. C. Code, §5-19 ............................................................. 23

S. C. Code, §21-2 ......................................... ..................... 22

S. C. Code, §21-230(7) .................................................... 22

S. C. Code, §21-238 (1957 Supp.) .................... ............. 22

S. C. Code, §§21-761 to 779, repealed by A. & J. R.

1955 (49) 85

PAGE

22

V

S. C. Code, §40-452 (1952) ..... 22

S. C. Code, §§51-1, 2.1-2.4 (1957 Supp.) ....................... 23

S. C. Code, §51-181 ......................................................... 23

S. C. Code Ann., Tit. 58, §§714-720 (1952) ....... 23

S. C. A. & J. R. 1956 No. 917 ................................... 22

S. C. A. & J. R. 1952 (47) 2223, A. & J. R. 1954 (48)

1695, repealing S. C. Const. Art. 11, §5 (1895) ....... 22

S. C. Code of Laws, Section 16-386 (1952 as amended)

3, 5, 6, 7,

8, 9,10

S. C. Code of Laws, Section 16-388 ........................... 14

Code of Virginia, 1960 Replacement Volume, §18.1-173 14

Wyoming Code, §6-226 ..................................................... 14

Code of the City of Charleston, §33-39 ...................... 5

O th e r A u thorities

American Penal Law Institute, Model Penal Code,

Tentative Draft No. 2, §206.53, Comment .............. 10

Annotation 49 A. L. R. 505 ......................................... 20

Ballantine, “ Law Dictionary” (2d Ed. 1948), 436 ....... 15

“Black’s Law Dictionary” (4th Ed. 1951) 625 .............. 15

Konvitz, A Century of Civil Bights (1961) .............. 20

PAGE

Ik t h e

(Emtrt nf tip Imtefr B M xb

O ctober T e r m , 1961

No.................

C h risto ph er M it c h e l l , J o h n B aile y , J oseph G erideau ,

J am es G ilbert B l a k e , A ndrew B r o w k , A l v in D elford

L a t t e n , F red S m a ll , C ornelius F ludd , C harles B u t

ler , F rancis J o h n son , D avid P au l R ichardson , J oseph

J ones, A lfred H a m il to n , H arvey G a n t t , A lle n C oley ,

K e n n e t h A ndrew G e r m a n , Carolyn J e n k in s , A rthu ree

S in g leto n , J enn iese B l a k e , D elores B r o w n , A n n ette

G r a h a m , C ecile G ordon, V erna J ean M cN eil , M inerva

B r o w n ,

Petitioners,

C it y of Ch arlesto n .

PETITION FOR W RIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

SUPREME COURT OF SOUTH CAROLINA

Petitioners pray that a writ of certiorari issue to review

the judgment of the Supreme Court of South Carolina,

entered in the above entitled case on December 13, 1961,

rehearing of which was denied on January 8, 1962.

Citation to Opinions Below

The opinion of the Supreme Court of South Carolina is

reported at 123 S. E. (2d) 512 and is set forth in the ap

pendix hereto, infra, pp. 9a-28a. The opinion of the Charles

ton County Court is unreported and is set forth in the

appendix hereto, infra, pp. la-8a.

2

Jurisdiction

The Judgment of the Supreme Court of South Carolina

was entered December 13, 1962, infra, pp. 9a-28a. Petition

for Rehearing was denied by the Supreme Court of South

Carolina on January 8, 1962, infra, p. 29a.

The jurisdiction of this Court is invoked pursuant to

Title 28, United States Code, Section 1257(3), petitioners

having asserted below and asserting here, deprivation of

rights, privileges and immunities secured by the Constitu

tion of the United States.

Questions Presented

1. Whether petitioners’ conviction of trespass, while en

gaged in a sit-in demonstration at a department store lunch

counter, offends the due process clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment when the criminal statute applied to convict

petitioners gave no fair and effective warning that their

actions were prohibited, and their conduct violated no

standard required by the plain language of the law or any

earlier interpretation thereof.

2. Whether the due process and equal protection clauses

of the Fourteenth Amendment permit a state to use its

executive and judiciary to enforce racial segregation in

conformity with a state custom of segregation by arresting

and convicting petitioners of criminal trespass on the

premises of a business which has for profit opened its

property to the general public.

3

1. This ease involves Section 1 of the Fourteenth

Amendment to the Constitution of the United States.

2. This case also involves Section 16-386, Code of Laws

of South Carolina for 1952, as amended, which states:

Entry on lands of another after

notice prohibiting same.

Every entry upon the lands of another where any

horse, mule, cow, hog or any other livestock is pastured,

or any other lands of another after notice from the

owner or tenant prohibiting such entry shall be a mis

demeanor and be punished by a fine not to exceed one

hundred dollars or by imprisonment with hard labor

on the public works of the county for not exceeding

thirty days. When any owner or tenant of any lands

shall post a notice in four conspicuous places on the

borders of such land prohibiting entry thereon a proof

of the posting shall be deemed and taken as notice

conclusive against the person making entry as afore

said for the purpose of trespassing.

Statement

At 10:45 A.M. on April 1, 1960, petitioners, twenty-four

Negro high school students entered the S. H. Kress and

Company department store in Charleston, South Carolina

(E. 11). They seated themselves at the lunch counter and

sought service (R. 11, 17, 18, 50, 52). Rather than serve

them, shortly after petitioners seated themselves (R. 11,

16) about 11 A.M. (R. 50), the manager roped off the

counter (R. 11,17, 47, 50), but did not request them to leave

(R. 11). The police were called at 10:45 A.M. (R. 19) and

Statutory and Constitutional Provisions Involved

4

remained in the store for the rest of the day (R. 19). Peti

tioners sat at the counter until about 4 :30 P.M. or for about

five and one-half hours (R. 11, 23, 24, 48, 70). At no time

during this period did anyone request petitioners to leave

the counter (R. 11,17, 29, 48).

At about 4:30 P.M., the Chief of Police of Charleston

(R. 11) told the manager that the police had received an

anonymous phone call claiming that a bomb would go off

in the Kress store at 4:45 P.M. (R. 21, 22, 23, 11). As a

result of this conversation, the manager, in the presence

of the Chief of Police (R. 31), approached petitioners and

“ • • • asked them to leave for their own safety . . . ” (R. 11,

23). Other patrons in the store were asked to leave by the

police, not the manager or store employees (R. 37). Peti

tioners remained seated at the counter (R. 12, 24). The

Chief of Police then requested petitioners to leave (R. 24)

and when they failed to respond, he placed them under

arrest (R. 25). Petitioners were at no time informed that

there was a “bomb scare” (R. 11, 24, 36). Later, the store

was searched and no bomb was found (R. 41).

Kress and Company is a large nationwide chain (R. 13)

which operates variety stores (R. 13). Negroes and whites

are invited to purchase and are served alike in all depart

ments of the store with the single exception that Negroes

are not served at the lunch counter which is reserved for

whites (R. 14, 15, 16). Negroes are not served at the lunch

counter because, as the store manager testified, “he would

be going against local customs” (R. 16). There was, how

ever, no evidence that any signs or notices are present in

the store indicating that Negroes are not served at the

lunch counter.

Throughout the events that led to their arrest, peti

tioners were completely orderly and peaceful (R. 38, 40).

5

Petitioners were charged under a warrant which alleged

that they did

■‘unlawfully, knowingly and willfully commit a tres

pass, in that they did refuse to leave the premises

and property of S. H. Kress & Company, having been

requested and ordered to leave, vacate and remove

themselves from said premises all in violation of Title

16, Section 386 of the Code of Laws of South Carolina

for 1952, as amended.” [Emphasis added.]

Title 16, Section 386 states:

Entry on lands of another after

notice prohibiting same.

“Every entry upon the lands of another where any

horse, mule, cow, hog or any other livestock is pastured,

or any other lands of another, after notice from the

owner or tenant prohibiting such entry shall be a mis

demeanor and be punished by a fine not to exceed one

hundred dollars or by imprisonment with hard labor

on the public works of the county for not exceeding

thirty days. When any owner or tenant of any lands

shall post a notice in four conspicuous places on the

borders of such land prohibiting entry thereon a proof

of the posting shall be deemed and taken as notice con

clusive against the person making entry as aforesaid

for the purposes of trespassing.” [Emphasis added.]

Petitioners were also charged with a violation of Section

33-39, Code of the City of Charleston in that they did

“ interfere with . . . [an] officer . . . of the police department

of the City” when they did not leave the lunch counter

when ordered to do so by the Chief of Police.

Petitioners were tried and convicted of both offenses in

the Recorder’s Court of the City of Charleston without a

6

jury, and sentenced to pay fines of $50.00 or serve fifteen

days in jail for each offense (E. 56), the sentences to run

consecutively (E. 56).

Petitioners appealed to the Charleston County Court

which affirmed the judgments of conviction of the Eecorder’s

Court of the City of Charleston on June 26, 1961, infra,

pp. la-8a.

They then appealed to the Supreme Court of South Caro

lina which affirmed the judgment of conviction of trespass

in violation of Title 16, Section 386 of the 1952 Code of

Laws of South Carolina, as amended, and reversed the judg

ment of conviction for the offense of interfering with a

police officer on December 13, 1961, infra, pp. 9a-28a. The

Supreme Court of South Carolina denied rehearing on Jan

uary 8, 1962, infra, p. 29a.

'City of Columbia v. Barr, et al.,------S. C .-------• 123 S. E.

2d 521, a sit-in case involving the same trespass statute,

was decided at the same time, and a petition for certiorari

in that case is being submitted simultaneously with this one.

How the Federal Questions Were Raised

and Decided Below

At the commencement of trial in the Eecorder’s Court,

petitioners moved to dismiss the warrant against them on

the ground that:

“ Title 16, Section 386 does not charge trespass, but it

set out the entry after notice. In that there are no

allegations in the warrant which shows an entry we

feel as though the warrant is insufficient in that it does

not substantially apprise the defendants of the crime

set forth in this warrant . . . ” (E. 8).

The motion was overruled by the trial Court (E. 8).

7

Petitioners appealed to the Charleston County Court

claiming error in that the warrant under which they were

convicted did not set forth the offense charged, “ in that

it does not specifically set forth the manner in which it

is contended that the defendants entered the lands of an

other after notice from the owner . . . thereby failing to

provide the defendants with sufficient information to meet

the charge against them . . . [in] deprivation of defendants’

liberty without due process of law, secured by the Four

teenth Amendment to the United States Constitution”

(R. 62).

The Charleston County Court ruled that the warrant

set forth the offense charged and was not vague, uncertain

and indefinite (R. 71). The Court held petitioners were

trespassers under Title 16, Section 386 (R. 74).

Petitioners appealed this ruling to the Supreme Court

of South Carolina (R. 78) asserting that the warrant did

not apprise them of the nature and cause of the accusation

against them (R. 78). Petitioners’ contended that Title 16,

Section 386, only made criminal an entry upon the premises

of another “ after notice from the owner or tenant pro

hibiting such entry” , infra, p. 16a, and to convict petitioners

on the ground that they remained upon the premises after

notice to leave was to open the Statute to the vice of vague

ness (R. 78). Relying principally on State v. Avent, 253

N. C. 580, 118 S. E. 2d 47, petition for writ of certiorari

pending in this Court, No. 85, October Term 1961, the South

Carolina Supreme Court rejected petitioners’ contention

holding that under Title 16, Section 386 a, person

who remains on the lands of another after being directed

to leave is guilty of a wrongful entry even though the orig

inal entrance was peaceful’ ”, infra, p. 18a. Under this

construction of the statute, the warrant was not uncertain

and indefinite, infra, pp. 13a-15a.

8

At the close of the City’s case in the trial court, defen

dants moved to dismiss the case against them on the

ground that “ . . . the Defendants were arrested on the

basis of race and color under color of law to enforce the

S. H. Kress and Company store racially discriminatory

policy, thereby violating the Defendants right to due process

of law and equal protection protected to them by the Four

teenth Amendment of the United States Constitution”

(R. 42, 43). The motion was denied (R. 43). The motion

was renewed at the close of the trial (R. 53, 54), and again

denied (R. 54). Defendants moved for a new trial and

arrest of judgment on the same ground (R. 56-58). The

motion was denied (R. 58). Defendants excepted to these

rulings by the trial court (R. 63-65, 78, 79) and defendants’

exceptions were overruled, on the merits, by the Charleston

County Court and the Supreme Court of South Carolina,

infra, pp. 6a, 7a, 20a-24a. The Supreme Court of South

Carolina, in disposing of petitioners’ contention that South

Carolina, enforced racial discrimination held that “ Section

16-386 of our code is not a racial segregation [statute],”

infra, p. 21a, and that the acts of state officials in enforcing

the trespass statute did not constitute “ state action en

forcing racial segregation” infra, pp. 24a, 21a-23a.

9

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE WRIT

I.

The Criminal Statute and Warrant Applied to Con

vict Petitioners Gave No Fair and Effective Warning

That Their Actions Were Prohibited; Petitioners’ Con

duct Violated No Standard Required by the Plain Lan

guage of the Law or Any Earlier Interpretation There

o f; Thereby Their Convictions Offend the Due Process

Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment and Conflicts With

Principles Enunciated by This Court.

Petitioners were convicted under Title 16, Section 386

of the Code of Laws of South Carolina of 1952 which pro

vides :

Every entry upon the lands of another where any

horse, mule, cow, hog or any other livestock is pastured,

or any other lands of another, after notice from the

owner or tenant prohibiting such entry shall be a mis

demeanor and be punished by a fine not to exceed one

hundred dollars or by imprisonment with hard labor

on the public works of the county for not exceeding

thirty days. When any owner or tenant of any lands

shall post a notice in four conspicuous places on the

borders of such land prohibiting entry thereon a proof

of the posting shall be deemed and taken as notice con

clusive against the person making entry as aforesaid

for the purpose of trespassing. [Emphasis added.]

Although the statute in terms forbids only entry on the

land of another after notice prohibiting one to do so, the

Supreme Court of South Carolina has now construed the

statute to forbid also remaining on property when directed

to leave following lawful entry, infra, pp. 18a-19a. In short,

the statute is now applied as if “ remaining” were substi

10

tuted for “ entry” . There is no history of such a construc

tion of the statute.1 No South Carolina case has ever

adopted such a construction. The statute, Section 16-386,

was originally passed in the Nineteenth Century and al

though amended on numerous occasions it has never lost

its character as a measure intended to punish entry on

farm land. The instant case is the first case which directly

or indirectly convicts defendants who went upon property

with permission and merely refused to leave when directed

for unlawful “ entry” .

Subsequent to petitioners’ conviction the legislature of the

State of South Carolina enacted into law Section 16-388

a trespass statute making criminal failing and refusing “ to

leave immediately upon being ordered or requested to do

so” the premises or place of business of another. See Peti

tion for Writ of Certiorari filed in this Court in Peterson

et al. v. City of Greenville, No. 750, Oct. Term, 1961.

There is no question but that petitioners and all Negroes

were welcome within the Kress store—apart from the lunch

counter area (R. 14, 46, 47). The manager of the store

testified that Negroes “are welcome to do business in those

departments [other than the lunch counter]” (R. 16). The

lunch counter is an integral part of the store (R. 11, 37,

46) so that the only “ entry” petitioners made was to the

store itself. There is no evidence of racial signs or notices

of any kind at the lunch counter. Whatever petitioners’

knowledge of the store’s racial policy as it had been prac

1 As authority for this construction the Supreme Court of South

Carolina cites the charge to the jury in State v. Williams, 76 S. C.

135, 56 S. C. 783, a murder case. No question of the meaning of

criminal trespass was involved in that case. Shramek v. Walker,

152 S. C. 88, 149 S. E. 331, also cited by the Supreme Court of

South Carolina, was a civil suit for trespass. But civil and crim

inal trespass have long been distinguished, the latter requiring,

at common law, special circumstances such as breach of the peace.

Rex v. Storr, 3 Burr. 1698. Cf. American Law Institute, Model

Penal Code, Tentative Draft No. 2, §206.53, Comment.

11

ticed (and petitioners’ testified they thought they might be

served (R. 47, 51, 52)) there was no suggestion that they

had ever been forbidden to go to the lunch counter and

request service.

Absent the special expansive interpretation given §16-386

by the South Carolina Supreme Court the case would plainly

fall within the principle of Thompson v. City of Louisville,

362 U. S. 19, and would be a denial of due process of law

as a conviction resting upon no evidence of guilt. There

was obviously no evidence that petitioners entered the

premises “after notice . . . prohibiting such entry” and

the conclusion that they did rests solely upon the special

construction of the law. Petitioners were not even charged

with “ entry” but with trespass “ in that they did refuse to

leave the premises” (R. 5).

Under familiar principles the construction given a state’s

statute by its highest court determines its meaning. Peti

tioners submit, however, that this statute has been judicially

expanded to the extent that it does not give a fair and

effective warning of the acts it now prohibits. Because of

the expansive construction, the statute now reaches more

than its words fairly and effectively define, and therefore,

as applied it offends the principle that criminal laws must

give fair and effective notice of the acts they prohibit.

The due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment

requires that criminal statutes be sufficiently explicit to

inform those who are subject to them what conduct on their

part will render them criminally liable. “All are entitled to

be informed as to what the State commands or forbids” ,

Lametta v. New Jersey, 306 U. S. 451, 453, and cases cited

therein in note 2.

Construing and applying federal statutes this Court has

long adhered to the principle expressed in Pierce v. United

States, 314 U. S. 306, 311:

12

. . . judicial enlargement of a criminal act by interpre

tation is at war with a fundamental concept of the

common law that crimes must be defined with appro

priate definiteness. Cf. Lanzetta v. New Jersey, 306

U. S. 451, and cases cited.

In Pierce, supra, the Court held a statute forbidding false

personation of an officer or employee of the United States

inapplicable to one who had impersonated an officer of the

T. V. A. Similarly in United States v. Cardiff, 344 U. S.

174, this Court held too vague for judicial enforcement a

criminal provision of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic

Act which made criminal a refusal to permit entry or

inspection of business premises “as authorized by” another

provision which, in turn, authorized eertain officers to enter

and inspect “after first making request and obtaining per

mission of the owner.” The Court said in Cardiff, at 344

U. S. 174,176-177”

The vice of vagueness in criminal statutes is the treach

ery they conceal either in determining what persons

are included or what acts are prohibited. Words which

are vague and fluid (cf. United States v. L. Cohen

Grocery Co., 255 U. S. 81) may be as much of a trap

for the innocent as the ancient laws of Caligula. We

cannot sanction taking a man by the heels for refusing

to grant the permission which this Act on its face

apparently gave him the right to withhold. That would

be making an act criminal without fair and effective

notice. Cf. Herndon v. Lowry, 301 U. S. 242.

The Court applied similar principles in McBoyle v. United

States, 283 U. S. 25, 27; United States v. Weitzel, 246 U. S.

533, 543, and United States v. Wiltberger, 18 U. S. (5

13

Wheat.) 76, 96. Through these eases run a uniform ap

plication of the rule expressed by Chief Justice Marshall:

It would be dangerous, indeed, to carry the principle,

that a case which is within the reason or mischief of a

statute, is within its provisions, so far as to punish

a crime not enumerated in the statute, because it is

of equal atrocity, or of kindred character, with those

which are enumerated (Id. 18 U. S. (5 Wheat.) at 96).

The cases discussed above involved federal statutes con

cerning which this Court applied a rule of construction

closely akin to the constitutionally required rule of fair

and effective notice. This close relationship is indicated

by the references to cases decided on constitutional grounds.

The Pierce opinion cited for comparison Lametta v. New

Jersey, supra, and “cases cited therein,” while Cardiff men

tions United States v. L. Cohen Grocery Go., supra, and

Herndon v. Lowry, supra.

On its face the South Carolina trespass statute warns

against a single act, i.e., entry upon the land of another

“ after” notice prohibiting such. “ After” connotes a se

quence of events which by definition excludes going on or

entering property “before” being forbidden. The sense

of the statute in normal usage negates its applicability

to petitioners’ act of going on the premises with permission

and later failing to leave when directed.

But by judicial interpretation “ entry” was held synony

mous with “ remaining” and, in effect, also with “ trespass” .

Here a legislative casus omissus was corrected by the court.

But as Mr. Justice Brandeis observed in United States v.

Weitzel, supra, at 543, a casus omissus while not unusual,

and often undiscovered until much time has elapsed, does

not justify enlargement of a criminal statute.

14

Moreover, that the warrant specified that petitioners had

refused to leave after being ordered to do so, does not

correct the unfairness inherent in the statute’s failure spe

cifically to define a refusal to leave as an offense. As this

Court said in Lametta v. New Jersey, supra:

It is the statute, not the accusation under it, that pre

scribes the rule to govern conduct and warns against

transgression. See Stromberg v. California, 283 U. S.

359, 368; Lovell v. Griffin, 303 U. S. 444.

Petitioners do not contend for an unreasonable degree

of specificity in legislative drafting. Some state trespass

laws have recognized as distinct prohibited acts the act

of going upon property after being forbidden and the act

of remaining when directed to leave.2 South Carolina

passed a statute punishing those who remain after being

directed to leave within a month of petitioners’ conviction,

Section 16-388, Code of Laws of South Carolina. See supra,

p. 10. Converting, by judicial construction, the common

English word “ entry” into a word of art meaning “ remain”

or “ trespass” has transformed the statute from one which

2 See for example the following state statutes which do effectively

differentiate between “ entry” after being forbidden and “ remain

ing” after being forbidden. The wordings of the statutes vary but

all of them effectively distinguish the situation where a person has

gone on property after being forbidden to do so, and the situation

where a person is already on property and refuses to depart after

being directed to do so, and provide separately for both situations:

Code of Ala., Title 14, §426; Compiled Laws of Alaska Ann. 1958,

Cum. Supp. Yol. I ll , §65-5-112; Arkansas Code, §71,1803; Gen.

Stat. of Conn. (1958 Rev.), §53-103; D. C. Code §22-3102 (Supp.

VII, 1956); Florida Code, §821.01; Rev. Code of Hawaii, §312-1;

Illinois Code, §38-565; Indiana Code, §10-4506; Mass. Code Ann.

C. 266, §120; Michigan Statutes Ann. 1954, Vol. 25, §28.820(1);

Minnesota Statutes Ann. 1947, Vol. 40, §621.57; Mississippi Code

§2411; Nevada Code, §207.200; Ohio Code, §2909.21; Oregon Code,

§164.460; Code of Virginia, 1960 Replacement Volume, §18.1-173;

Wyoming Code, §6-226.

15

fairly warns against one act into a law widen fails to

apprise those subject to it “ in language that the common

world will understand, of what the law intends to do if a

certain line is passed” (McBoyle v. United States, 283

II. S. 27). Nor does common law usage of the word “ entry”

support the proposition that it is synonymous with “ tres

pass” or “ remaining”. While “ entry” in the sense of going

on and taking possession of land is familiar (Ballantine,

“Law Dictionary” (2d Ed. 1948), 436; “ Black’s Law Dic

tionary” (4th Ed. 1951, 625), its use to mean remaining on

land and refusing to leave it when ordered off is novel.

Judicial construction often has cured criminal statutes

of the vice of vagueness, but this has been construction

which confines, not expands, statutory language. Compare

Chaplinsky v. New Hampshire, 315 U. S. 568, with Herndon

v. Loivry, 301U. S. 242.

At the time of their arrest, petitioners were engaged

in the exercise of free expression by verbal and nonverbal

requests for nondiscriminatory lunch counter service, im

plicit in their continued remaining at the lunch counter

when refused service.

If in the circumstances of this case free speech is to

be curtailed, the least one has a right to expect is reasonable

notice in the statute under which convictions are obtained.

Winters v. New York, 333 U. S. 507. To uphold petitioners’

conviction by novel and enlarged construction of this statute

is to violate the principle that when freedom of expression

is involved conduct must be proscribed within a statute

“narrowly drawm to define and punish specific conduct as

constituting a clear and present danger to a substantial

interest of the State” , Cantwell v. Connecticut, 310 U. S.

296, 307, 308; Garner v. Louisiana, 368 U. S. 157, 185

(Mr. Justice Harlan concurring). If the Supreme Court of

South Carolina can affirm the convictions of these peti

16

tioners by such a construction it has exacted obedience

to a rule or standard that is so ambiguous and fluid as to

be no rule or standard at all. Champlin Rev. Co. v. Cor

poration Com. of Oklahoma, 286 U. S. 210. But when free

expression is involved, the standard of precision is greater;

the scope of construction must, consequently be less. If

this is the case when a State court limits a statute it must

a fortiori be the case when a State court expands the mean

ing of the plain language of a statute. Winters v. New

York, 333 U. S. 507, 512.

As construed and applied, the law in question no longer

informs one what is forbidden in fair terms, and no longer

warns against transgression. This failure offends the

standard of fairness expressed by the rule against ex

pansive construction of criminal laws which is embodied

in the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

II.

The State of South Carolina Has Enforced Racial

Discrimination Contrary to the Equal Protection and

Due Process Clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment to

the Constitution of the United States.

Petitioners were not served in Kress’s because they were

Negroes and the custom of the City of Charleston is that

Negroes may not be served at counters which also cater

to whites (R. 14, 17). No other variety store lunch counter

in Charleston would have served petitioners either (R. 14).

They sat at the counter, however, because they thought the

management “might” “ change their mind and serve” them

(R. 50). If they had been served when they sought service,

they would have been out of the store and away from the

counter shortly after having entered it, in the morning,

well before 4:45 P.M. (R. 17).

17

As things were, they remained seated at the counter

nntil late afternoon when there was a “bomb scare.” Pur

suant to police and fire department policy (R. 27, 41), the

store manager asked the petitioners to leave the store,

although neither police, fire, nor store officials informed

petitioners that there was a “bomb scare” (R. 36, 48). It

may be noted that at the same time the police themselves

directed other patrons to depart (R. 37). Upon petitioners’

failure to leave, police arrested them for trespassing.

In the context of the entire episode petitioners were,

therefore, arrested for two reasons—indirectly to enforce

the custom of racial segregation and because of the “ bomb

scare”—as the chief of police acknowledged upon cross

examination:

Q. Now, Chief, when you asked these twenty-four

young people to leave Kress’s Store, weren’t you just

helping the manager of Kress to maintain the policy

[of not serving Negroes at the lunch counter] which

the store already followed? A. I would say indirectly,

yes. Paramount and more so for the safety of every

one leaving the building (R. 33).

Failure to depart from the premises because of the “bomb

scare,” stems from Charleston’s and Kress’s segregation

policy. Petitioners never would have been in the store at

the time of the bomb threat if they had been served on the

same basis as white persons. Moreover, to the exent that

petitioners have an immunity from arrest to enforce racial

segregation—discussed in detail below—they had a right to

persist in demanding service. If some secret, nonracial

reason existed whereby anyone without regard to race

might have been required to leave, they hardly could have

been expected to conform to the demand without knowing

that suddenly a nonracial standard was being applied. The

case is as Boynton v. Virginia, 364 U. S. 454, would have

18

been, if unknown to Boynton he were asked to leave the

premises because of a “bomb scare.” If knowing that the

management is disabled from enforcing a demand to depart

based upon race, by police and judicial action, one persists

in demanding service, it hardly can be made criminal that

the manager has a secret nonracial reason which subse

quently he discloses.

Indeed, petitioners originally were charged with two

offenses, (1) trespass and (2) interfering with a police

officer, in violation of a Charleston ordinance. The convic

tion on the second charge was reversed by the State Su

preme Court on the ground that petitioners’ conduct was

passive, not active, and did not constitute “ interference” ,

infra, p. 27a. The refusal to obey the police with respect

to the bomb situation, therefore, no longer appears to be

in the case. To the extent that the management ordered

petitioners to leave because of the “bomb” situation, it was

carrying out police and fire department policy, not asserting

a “property” right.

The subsisting offense, trespass, is one against the State’s

interest in enforcing Kress’s “property right,” not in police

regulation of a dangerous situation involving a “bomb

scare.”

The Supreme Court of South Carolina recognized the

issue in this case to be whether police and judicial enforce

ment of Kress’s racial segregation policy violated the equal

protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

The appellants assert that the court erred in re

fusing to hold that their arrests and convictions were

in furtherance of a custom of racial segregation in

violation of the Fourteenth Amendment to the United

States Constitution. It is also asserted that enforce

ment of segregation in this case was by State action

within the meaning of such Fourteenth Amendment

(infra, p. 20a).

19

It answered this question contrary to petitioners’ posi

tion by relying upon cases involving similar issues, some

of which are now pending before this Court, e.g., Randolph

v. Virginia, 202 Va. 661, 119 S. E. 2d 817 (No. 248, October

Term, 1961); City of Greenville v. Peterson, 122 S. E. 2d

826 (No. 750, October Term, 1961); State v. Avent, 253

N. C. 580, 118 S. E. 2d 47 (No. 85, October Term, 1961).

But the decision below flies in the face of principles

declared by this Court, Where there is state action by the

police, Screws v. United States, 325 U. S. 91; Monroe v.

Pape, 365 U. S. 167; prosecutors, Napue v. Illinois, 360

IT. S. 264, and judiciary, Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1,

14-18; Boynton v. Virginia, 364 U. S. 454, racial discrimina

tion supported by state authority violates the Fourteenth

Amendment. Civil Rights Cases, 109 U. S. 3, 17.

It is asserted, however, that the state is not enforcing

racial discrimination, but is implementing a property right.

But to the extent that management was asserting a “prop

erty” right to enforce racial segregation according to the

custom of the City of Charleston, it becomes pertinent to

inquire just what that property right is.

The mere fact that “property” is involved does not

settle the matter, Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1, 22.

“ Dominion over property springing from ownership is not

absolute and unqualified.” Buchanan v. War ley, 245 U. S.

60, 74; United States v. Willow River Power Co., 324 U. S.

499, 510; Marsh v. Alabama, 326 U. S. 501, 506; cf.

Munn v. Illinois, 94 U. S. 113; Republic Aviation Corp.

v. N. L. R. B., 324 IT. S. 793, 796, 802.

Kress’s is a commercial variety store open to the public

generally for the transaction of business, including the sale

of food and beverages at is lunch counter. It does not seek

to keep everyone, or Negroes, or these petitioners from

20

coming upon the premises. The white public is invited to

use all the facilities of the store and Negroes are invited

to use all these facilities except the lunch counter. The

management does not seek to exclude petitioners because

of an arbitrary caprice, but rather, follows the community

custom of Charleston which is, in turn, supported and

nourished by law.

The portion of the store from which petitioners are

excluded is not set aside for private or non-public use as

an office reserved for the management or lounge or private

restroom for employees. Petitioners did not seek to use the

lunch counter for any function inappropriate to its normal

use. They merely sought lunch counter service. Therefore,

it appears that the property interest which the State pro

tects here, by arrest, prosecution, and criminal conviction,

is the claimed right to open the premises to the public

generally, including Negroes, for business purposes, in

cluding the sale of food and beverages, while racially dis

criminating against Negroes, as such, at one integral part

of the facilities. While this may, indeed, be a property

interest, the question before this Court is whether the

State may enforce it without violating the Pourteenth

Amendment. This property interest certainly may be taken

away by the State without violating the Fourteenth Amend

ment. Western Turf Asso. v. Greenberg, 204 U. S. 359;

Railway Mail Assn. v. Corsi, 326 IT. S. 88; Pickett v. Kuchan,

323 111. 138, 153 N. E. 667, 49 A. L. R. 499 (1926); People

v. King, 110 N. Y. 419, 18 N. E. 245 (1888); Annotation 49

A. L. R. 505; cf. District of Columbia v. John R. Thompson

Co., 346 U. S. 100.

Many states make it a crime to engage in the racially

discriminatory use of private property which South Caro

lina enforces here. For the latest collection of such statutes,

see Konvitz, A Century of Civil Rights (1961), passim.

Indeed, Kress s has sought to achieve in this case some

21

thing which the State itself could not permit it to do on

state property leased to it for business use. Burton v.

Wilmington Parking Authority, 365 U. S. 715, or require

or authorize it to do by positive legislation. See Mr. Justice

Stewart’s concurring opinion in Burton, supra. Although

it does not necessarily follow from the fact that some states

constitutionally may make racial discrimination on private

property criminal, that other states may not enforce racial

discrimination, it does become evident that Kress’s prop

erty interest is hardly inalienable or absolute.

Basic to the disposition of this case is that Kress is a

public establishment open to serve the public as a part

of the public life in the community. See Garner v. Louisiana,

368 U. S. 157, 176, Mr. Justice Douglas concurring. The

case involves no genuine claim that Kress’s right “private”

use of its property was interfered with by petitioners. To

uphold petitioners’ claims here affects only slightly the

entire range of what are called private property rights.

For if Kress is disabled by the Fourteenth Amendment

from enforcing by state action racial bias at its public

lunch counter, homeowners are hardly disabled from en

forcing their private rights even to implement racial

prejudices. There is a constitutional right of privacy pro

tected by the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amend

ment. Mapp v. Ohio, 367 U. S. 643, 6 L. ed. 2d 1081, 1080,

1103, 1104; see also Poe v. Ullnian, 367 U. S. 497, 6 L. ed.

2d 989, 1006, 1022-1026 (dissenting opinions). This Court

has recognized the relationship between right of privacy

and property interests. Thornhill v. Alabama, 310 U. S.

88, 105-106; Breard v. Alexandria, 341 U. S. 622, 626, 638,

644. Only a very absolutist view of the property right

to determine who may come or stay on one’s property on

racial grounds would require that a unitary principle apply

to the whole range of property uses, public connections,

dedications, and privacy interests which may be at stake.

22

As Mr. Justice Holmes stated in Hudson County Water

Co. v. McCarter, 209 U. S. 349, 355:

All rights tend to declare themselves absolute to their

logical extreme. Yet all in fact are limited by the

neighborhood of principles of policy which are other

than those on which the particular right is founded,

and which become strong enough to hold their own

when a certain point is reached.

Where a right of private property is asserted by a

proprietor so narrowly as to claim state intervention only

in barring Negroes from a single portion of a public estab

lishment, and that restricted assertion of right collides with

the great immunities of the Fourteenth Amendment, peti

tioners respectfully submit that the property right is no

right at all.

Moreover, the assertion of racial prejudice here is not

“private” at all. The segregation here enforced is that

demanded by custom of the City of Charleston. While

“ custom” is referred to in the Civil Rights Cases as one

of the forms of state authority within the prohibitions of

the Fourteenth Amendment, 109 U. S. 3, 17 (see also Mr.

Justice Douglas concurring in Garner v. Louisiana, 368

U. S. 157, 179, 181), Charleston’s custom exists in a context

of massive state support of racial segregation.3

3 See S. C. A. & J. R. 1952 (47) 2223, A. & J. R. 1954 (48) 1695

repealing S. C. Const. Art. 11, §5 (1895) (which required legis

lature to maintain free public schools). S. C. Code §§21-761 to

779 (regular school attendance) repealed by A. & J. R. 1955 (49)

85; §21-2 (appropriations cut off to any school from which or to

which any pupil transferred because of court order; §21-230(7)

(local trustees may or may not operate schools); §21-238 (1957

Supp.) (school officials may sell or lease school property whenever

they deem it expedient) ; S. C. Code §40-452 (1952) (unlawful

for cotton textile manufacturer to permit different races to work

together in same room, use same exits, bathrooms, etc., $100 pen

alty and/or imprisonment at hard labor up to 30 days; S. C. A. &

J. R. 1956 No. 917 (closing park involved in desegregation su it);

23

Consequently, we have here state nurtured and state

enforced racial segregation in a public institution concern

ing which no property right may be asserted in the face

of the Fourteenth Amendment’s prohibition of state en

forced racial segregation. This state enforced segregation

conflicts with Fourteenth Amendment principles which have

been consistently asserted by this Court.

CONCLUSION

W herefore , for the foregoing reasons petitioners respect

fully pray that the Petition for Writ of Certiorari be

granted.

Respectfully submitted,

J ack G reenberg

Constance B ak er M otley

J am es M. N abrit , III

M ich ael M eltsner

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

M a t t h e w J . P erry

L incoln C. J e n k in s , J r .

IIO714 Washington Street

Columbia, South Carolina

J ohn H. W righ ten

R ussel B rown

Charleston, South Carolina

Attorneys for Petitioners

S. C. Code §§51-1, 2.1-2.4 (1957 Supp.) (providing for separate

State Parks) §51-181 (separate recreational facilities in eities with

population in excess of 60,000); §5-19 (separate entrances at

circus); S. C. Code Ann. Tit. 58, §§714-720 (1952) (segregation

in travel facilities).

APPENDIX

I n th e

CHARLESTON COUNTY COURT

C it y of C harleston ,

—v.-

Respondent,

M it c h e l l , el al.,

Appellants.

Order of the Charleston County Court

This is an appeal from the Recorder’s Court of the

City of Charleston, there, on April 19, 1960, the twenty-

four (24) named defendants were tried and found guilty

of violating Section 16-386 of the Code of Laws of South

Carolina for 1952, and Section 33-39 of the Ordinances of

the City of Charleston, 1952. The defendants were charged

on two separate warrants, the first charging all of the

defendants, and each of them, with committing a trespass

upon the property of S. H. Kress & Company in the City of

Charleston, and the second charging all of the defendants,

and each of them, with resisting and interfering with the

Chief of Police of the City of Charleston in the discharge

of his official duties.

The record show’s that on April 1, 1960, at about 10:45

A. M. the twenty-four (24) defendants, all of whom are

young Negroes, entered the premises of S. H. Kress &

Company in the City of Charleston and seated themselves

at the lunch counter. Shortly after they occupied seats

at the lunch counter, the counter was closed for business

2a

and the area was roped off. The defendants remained

seated at the counter until about 4 :30 P. M., at which time

Mr. Albert C. Watts, the manager of the Kress store, ap

proached the group, told them who he was, and requested

them to leave the store premises. He repeated his request,

but the defendants remained seated. The evidence shows

that the City Police had received an anonymous telephone

call reporting that there was a bomb in the store set to go

off at 4:45 P. M. This information was relayed to the

Chief of Police, who was stationed in the Kress store at

the time, and he in turn reported this information to Mr.

Watts, the store manager. Mr. Watts determined at that

time to close the store and clear the building of all em

ployees and customers. It was then that he approached

the defendants and asked them twice to leave the premises.

Immediately thereafter, the Chief of Police spoke to the

defendants, identified himself, and ordered them to leave

the store. The defendants remained seated and the Chief

repeated his order. When the defendants refused to leave,

they were placed under arrest.

Upon trial and conviction in Recorder’s Court, each of

the defendants was sentenced to pay a fine of Fifty ($50.00)

Dollars or serve a term of fifteen (15) days in jail on each

of the charges, the sentences to run concurrently. All of the

defendants have appealed the rulings and the judgments

of the Recorder of the City of Charleston.

Before pleading to the charges, the defendants challenged

the sufficiency of the two separate warrants and moved for

dismissal of both warrants on the ground that they were

vague, uncertain and indefinite and did not plainly set

forth the offenses charged. The defendants’ motion for

dismissal were denied by the Recorder, and properly so

in the opinion of this Court.

Order of the Charleston County Court

3a

Our State Constitution, in Article 1, Section 18, affords

to a person charged with a criminal offense the right to

be fully informed of the nature and cause of the accusation.

An inspection of the warrants in this case reveals that

the offenses charged are stated in clear and definite lan

guage which fully and adequately informed the defendants

of the nature and cause of the charges.

Before entering pleas at trial, the defendants moved to

require the City of Charleston, under Section 15-902 of

the State Code, to elect which of the charges preferred

against them the City would proceed to trial on. It was

the defendants’ contention that the offenses charged actu

ally arose out of the same facts and circumstances and

were, in fact, not separate acts but a single act on the

part of the defendants. The Recorder overruled this

motion.

Section 15-902 provides that “whenever a person be ac

cused of committing an act which is susceptible of being

designated as several different offenses, the magistrate or

the municipal court * * * shall be required to elect which

charge to prefer. * * * ” (Emphasis added.)

In the light of the evidence, it is the opinion of this court

that the motion to elect was properly overruled by the

trial judge. The evidence clearly shows that the defendants

were first requested by the manager of Kress to leave the

store premises. They refused this request, and thereafter,

they refused an order of the Chief of Police. In fact and

in law, these were two separate and distince acts on the

part of the defendants. The first act was directed against

the private property rights of S. H. Kress & Company,

while the second act, entirely different in nature, was di

rected against the Sovereign in the person of the Chief

of Police of the City of Charleston. The acts did not

Order of the Charleston County Court

4a

happen at the same time, and it was entirely possible for

the defendants to be guilty of one offense and innocent

of the other.

Section 15-902 contemplates a single “ act” . Here, we have

two separate and independent refusals to leave the store

premises. The act of trespass was final and complete be

fore there occurred the entirely independent act of inter

ference with a police officer in the discharge of his duty.

At the close of the case for the prosecution, and again

after the close of all evidence, the defendants interposed

motions for dismissal of the charge. Each motion was

overruled. After judgment and sentencing, the defendants

moved for arrest of judgment or in the alternative, for a

new trial on basically the same grounds which were cited

in support of their earlier motions for dismissal. The

Recorder overruled such motions.

In their Notice of Intention to Appeal as well as in their

brief, the defendants in essence contend that their arrest

and subsequent conviction constitutes State action to en

force racial segregation, in violation of their rights under

the due process clause and under the equal protection of the

laws clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Federal

Constitution. They contend that the evidence shows that

in arresting the defendants the police officers of the City

of Charleston were aiding and assisting the management

of S. H. Kress & Company in refusing lunch counter ser

vice to the defendants solely on account of their race or

color. They further contend that S. H. Kress & Company

is “ invested with the public interest” and is, therefore,

required to provide services “ in the manner of State op

erated facilities of a like nature” , and may not segregate

or exclude persons on the basis of race or color. There

is no merit in the defendants’ contentions.

Order of the Charleston County Court

5a

S. H. Kress & Company owns and operates a store on

King Street in the City of Charleston. It is common

knowledge that it is a five and ten cent store engaged in

the business of offering for sale various articles of mer

chandise. In the conduct of its business, Kress also owns

and operates a food and lunch counter in a part of the

store premises. S. H. Kress & Company, as other retail

stores, opens its doors to the general public and invites

the public in to do business. According to the testimony

of the store manager, it is the policy of Kress to operate

its business in accordance with prevailing local custom,

and following such custom, it does not serve Negroes at

its lunch counter.

Although a member of the general public has an in

vitation or implied license to enter a retail store to do

business, the proprietor or manager of such store has

the right to revoke this license at any time. An invitation

to the public to come into a store to buy does not auto

matically impose upon the store an obligation to sell. A

private business always has the right to select its cus

tomers and to make such selection on any basis it chooses.

A private business is under no compulsion whatsoever to

serve everyone who enters and applies for service.

Section 16-386, under which the defendants were found

guilty, reads: “ Every entry upon the lands of another * * *

after notice from the owner or tenant prohibiting such

entry, shall be a misdemeanor. * * * ” The obvious and

sole purpose of this statute is to protect the property

owner from trespassers on his property. The statute is

directed against all trespassers, regardless of race or color.

“ The right of property is a fundamental, natural, in

herent, and inalienable right. It is not ex gratia from the

legislature, but ex debite from the Constitution. In fact,

Order of the Charleston County Court

6a

it does not owe its origin to the Constitutions which pro

tect it, for it existed before them. It is sometimes char

acterized judicially as a sacred right, the protection of

which is one of the most important objects of government.

The right of property is very broad and embraces prac

tically all incidents which property may manifest.” 11

Am. Jur., Constitutional Law, Section 335.

The defendants in this case entered the property of S. H.

Kress & Company presumably in the role of customers.

They seated themselves at the lunch counter for some five

hours and refused the store manager’s request that they

leave. When they refused this request they became under

the law trespassers. There is absolutely no merit in the

defendants’ contention that their arrest by the City Police

constituted State action.

Recently, the Supreme Court of our sister State of North

Carolina had before it a case quite similar to the instant

case. State v. Avent et al., 253 N. C. 580, 118 S. E. (2d)

47. There, as here, the Court was considering a trespass

case, or “ sit-in demonstration” as such incidents have been

termed, which took place in a S. II. Kress & Company store

in Durham, North Carolina. The following quotation from

that case is appropriate to the case at hand.

“Private rights and privileges in a peaceful society liv

ing under a constitutional form of government like ours are

inconceivable without State machinery by which they are

enforced. Courts must act when parties apply to them—

even refusal to act is a positive declaration of law—and,

hence, there is a fundamental inconsistency in speaking of

the rights of an individual who cannot have judicial recog

nition of his rights. All the State did * * * was to give or

create a neutral legal framework in which S. H. Kress &

Company could protect its private property from tres

Order of the Charleston County Court

7a

passers. * * * There is a recognizable difference between

State action that protects the plain legal right of a person

to prevent trespassers from going upon his land after

being forbidden, or remaining upon his land after a demand

that they leave, even though it enforces the clear right of

racial discrimination of the owner, and State action enforc

ing covenants restricting the use or occupancy of real

property to persons of the Caucasian race. The fact that

the State provides a system of courts so that S. H. Kress

& Company can enforce its legal rights against trespassers

upon its property * * * and the acts of its judicial officers

in their official capacities, cannot fairly be said to be State

action enforcing racial segregation in violation of the 14th

Amendment to the Federal Constitution. Such judicial

process violates no rights of the defendants. * * * To rule

as contended by defendants would mean that S. H. Kress

& Company could enforce its rights against White tres

passers alone, but not against Negro trespassers. * * *

Surely, that would not be an impartial administration of

the law, for it would be a denial to the White race of the

equal protection of the law. If a landowner or one in pos

session of land cannot protect his natural, inherent and

constitutional right to have his land free from unlawful

invasion by * * * trespassers in a case like this by judicial

process as here, because it is State action, then he has no

other alternative but to eject them, with a gentle hand if

he can, with a strong hand if he must. White people also

have constitutional rights as well as Negroes, which must

be protected, if our constitutional form of government is

not to vanish from the face of the earth.”

The customs of the people of a State do not constitute

State action within the prohibition of the Fourteenth

Amendment. Williams v. Howard Johnson’s Restaurant,

268 F. (2d) 845.

Order of the Charleston County Court

8a

In Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1, 92 L. Ed. 1161,

3 A. L. R. (2d) 441, the Court said: “ Since the decision

of this Court in the Civil Rights cases, 109 U. S. 3, 27 L. Ed.

835, 3 S. Ct. 18 (1883), the principle has become firmly

embedded in our constitutional law that the action inhibited

by the first section of the Fourteenth Amendment is only

such action as may fairly be said to be that of the State.

That Amendment erects no shield against merely private

conduct, however discriminatory or wrongful.”

None of the cases cited in the defendants’ brief are ap

plicable to the situation before this Court for the reasons

already stated.

Although the defendants make no mention of it in their

brief, they contend in their grounds for appeal that Sec

tion 16-386 is unconstitutional in that it does not require

that a person making the demand to leave present docu

ments or other evidence of possessory right sufficient to

apprise the defendants of the validity of the demand. This

contention is not tenable. The evidence shows very clearly

that the manager of S. H. Kress & Company identified

himself to the defendants before he requested them to leave

the store. No more than that is required under this statute.

All of the defendants’ grounds for appeal have been con

sidered, and all are overruled. The defendants have not

shown that any of their rights guaranteed by the Four

teenth Amendment to the Federal Constitution have been

violated.

The judgments of the Recorder’s Court of the City of

Charleston are affirmed.

/ s / T h o s . P. B ussey ,

Judge, Ninth Judicial Circuit.

Charleston, South Carolina,

June 26,1961.

Order of the Charleston County Court

9a

Opinion of Supreme Court of South Carolina

THE STATE OF SOUTH CAROLINA

I n t h e S u prem e C ourt

C it y oe Charleston ,

— Y .—

Respondent,

C h risto ph er M it c h e l l , J o h n B ailey , J oseph G erideau ,

J am es G ilbert B l a k e , A ndrew B r o w n , A l v in D eleord

L atten , F red S m a ll , Cornelius F ludd , C harles B u tler ,

F rancis J o h n son , D avid P au l R ichardson , J oseph

J ones, A lfred H a m il to n , H arvey G a n t t , A lle n C oley ,

K e n n e t h A ndrew G erm an , Carolyn J e n k in s , A rth u ree

S in g leton , J en n iese B l a k e , D elores B r o w n , A n n ette

G r a h a m , Cecile G ordon, V ern a J ean M cN eill and

M in erva B r o w n ,

Appellants.

Appeal From Charleston County

T h o m as P. B ussey , Judge

Filed December 13, 1961

R eversed in P a r t ;

A ffirm ed in P art

Moss, A. J .:

The twenty-four appellants, all of whom are Negro high

school students, were arrested on April 1,1960, and charged

with the violation of Section 16-386, as amended, of the

10a

1952 Code of Laws of South Carolina, and Section 33-39,

1952 Code of the City of Charleston.

The appellants were tried before the City Recorder in

the police court of the City of Charleston, on April 19, 1960.

Each of the appellants was found guilty of both charges

and sentenced to pay a fine of Fifty & 00/100 ($50.00) Dol

lars or to imprisonment for fifteen days on each offense,

the sentences in each case to run concurrently. The con

viction of each of the appellants was sustained by the

Circuit Court. The appellants gave timely notice of in

tention to appeal to this Court.

The questions involved in this appeal may be summarized

as follows: (1) Did the court err in refusing to hold that

the warrants charging the appellants with the violation of

Section 16-386, as amended of the 1952 Code of Laws of

South Carolina, and of Section 33-39, 1952 Code of the

City of Charleston, were vague, indefinite and uncertain

and do not plainly and substantially set forth the offenses

charged. (2) Did the testimony fail to establish the corpus

delicti or prove a prima facie case. (3) Did the court err

in refusing to hold that under the facts of these cases, the

arrests and convictions of the appellants were in further

ance of a custom of racial segregation in violation of the

Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United

States. Under this question the appellants assert that the

enforcement of segregation was by State action and that

they were unwarrantedly penalized for exercising their free

dom of expression.

The first question for determination is whether the ap

pellants’ motion to quash and dismiss the warrants should

have been sustained upon the ground that the charge con

tained in each of said warrants was too vague, indefinite

and uncertain, in that they do not substantially apprise

Opinion of Supreme Court of South Carolina

11a

them of the offenses charged. The appellants were tried

on warrants which were based on an affidavit of the Chief

of Pdice of the City of Charleston. In the first affidavit he

avers that the appellants, on April 1, 1960, “did unlawfully,

knowingly, and willfully commit a trespass, in that they

did refuse to leave the premises and property of S. H. Kress

& Company, having been requested and ordered to leave,

vacate and remove themselves from said premises, all in

violation of Title 16, Section 386, of the Code of Laws of

South Carolina for 1952, as amended, and against the peace

and dignity of the said State.” The second warrant charged

that the appellants, on April 1, 1960, “did unlawfully,

knowingly, and willfully hinder, resist, oppose and inter

fere with an employee of the City of Charleston, namely,

William F. Kelly, Chief of Police, in the discharge of his

official duties, in that they did refuse to leave the premises

and property of S. H. Kress & Company after being ordered

and requested to do so by William F. Kelly, Chief of Police,

all in violation of Section 33-39 of the Code of the City

of Charleston, 1952, and against the peace and dignity of

said State.”

The pertinent portion of Section 16-386, as amended, of

the 1952 Code of Laws of South Carolina, is as follows:

“ Every entry upon the * * * lands of another, after

notice from the owner or tenant prohibiting such entry,

shall be a misdemeanor and be punished by a fine not to

exceed one hundred dollars, or by imprisonment with

hard labor on the public works of the county for not

exceeding thirty days. When any owner or tenant of

any lands shall post a notice in four conspicuous places

on the borders of such land prohibiting entry thereon,

a proof of the posting shall be deemed and taken as

notice conclusive against the person making entry as

aforesaid for the purpose of trespassing.”

Opinion of Supreme Court of South Carolina

12a

Section 33-39, of the 1952 Code of the City of Charleston,

provides:

“ It shall be unlawful for any person to assault, resist,

hinder, oppose, molest or interfere with any em

ployee of the City or of any department or board there

of, or any officer or employee of the police department

of the City, in discharge of official duties, under penalty

of fine of not less than twenty dollars or not more

than one hundred dollars or imprisonment not exceed

ing 30 days.”

Article 1, Section 18, of the 1895 Constitution of this

State, provides that in all criminal prosecutions the ac

cused shall have the right “to be fully informed of the

nature and cause of the accusation.” This Constitutional

right is set forth with reference to criminal prosecutions in

a Magistrate’s Court in Section 43-111 of the 1952 Code of

Laws of South Carolina, as follows: “All proceedings be

fore magistrates in criminal cases shall be commenced on

information under oath, plainly and substantially setting

forth the offense charged, upon which, and only which, shall

a warrant of arrest issue.” Section 43-112, of the 1952 Code,

provides that the information may be amended at any

time before trial. Proceedings before a magistrate are sum

mary in nature. Section 43-113 of the 1952 Code of Laws.

We should point out that Section 15-901 of the 1952 Code

of Laws gives to the mayor or intendant of the cities and

towns of this State all the powers and authority of magis

trates in criminal cases for offenses committed within the

corporate limits and within the police jurisdiction of the re

spective cities and towns, as is contained in Section 43-111

of the 1952 Code. Section 15-1561 of the Code gives to

the recorder of the police court of the City of Charleston

all the powers, duties and jurisdiction of a magistrate.

Opinion of Supreme Court of South Carolina

13a

In the case of State v. Randolph, et al., 239 S. C. 79, 121

S. E. (2d) 349, which prosecution originated in a Magis

trate’s Court, we summarized the rule concerning the right

of an accused to be fully informed of the offense charged

against him. We said:

“Proceedings before a magistrate are summary in

nature. Section 43-113 of the 1952 Code. His jurisdic

tion to try criminal cases is confined to minor offenses.

Many of our magistrates are without legal training.

In the preparation of warrants they are not required

to conform to the technical precision required in indict

ments. Duffie v. Edwards, 185 S. C. 91, 193 S. E. 211.

But it does not follow that the accused may be denied

those fundamental rights essential to a fair trial,

among which is the right to be informed of the nature

of the offense charged against him. In McConnell v.

Kennedy, 29 S. C. 180, 7 S. E. 76, 80, the Court stated

that the manifest object of the statute now forming

Section 43-111 of the 1952 Code was ‘to require that

the offense with which a party was charged should be

so set forth, plainly and substantially, as would enable

the party accused to understand the nature of the of

fense with which he was charged, so that he might

be prepared to meet the charge at the proper time.’ In

Town of Ilonea Path v. Wright, 194 S. C. 461, 9 S. E.