Appellant's Petition for Rehearing and Suggestion for Hearing In Banc with Cover Letter

Public Court Documents

December 21, 1972

14 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Milliken Hardbacks. Appellant's Petition for Rehearing and Suggestion for Hearing In Banc with Cover Letter, 1972. 62be28b2-53e9-ef11-a730-7c1e5247dfc0. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/804a2252-6338-4895-be4c-aeb86d29937b/appellants-petition-for-rehearing-and-suggestion-for-hearing-in-banc-with-cover-letter. Accessed February 27, 2026.

Copied!

H I L L , L E W I S , A D A M S , G O O D R I C H 6c T A I T

3 7 0 0 P E N O B S C O T B U I L D I N G

S H E R W I N A . H J L L ( 1 6 0 5 - 1 9 6 1 )T H O M A S H . A D A M S

E D W A R D T. G O O D R I C H

G A R L A N D D. T A I T

J A Y W . S O R G E

E L L I O T T H . P H I L L I P S

W I L L I A M W. S L O C U M , J R .

T H O M A S E . C O U L T E R

M A R T I N C . O E T T I N G

L E E B D U R H A M , J R .

W. M E R R I T T J O N E S , J R .

R O B E R T B . W E B S T E R

D O U G L A S H . W E S T

D A V I D L . R O L L

T I M O T H Y W. M A S T

T I M O T H Y D . W I T T L I N G E R

D E T R O I T , M I C H I G A N 4 0 2 2 6

T E L E P H O N E ( 3 1 3 ) 9 6 2 - 6 - 4 8 5

C A B L E A D D R E S S : H I L L

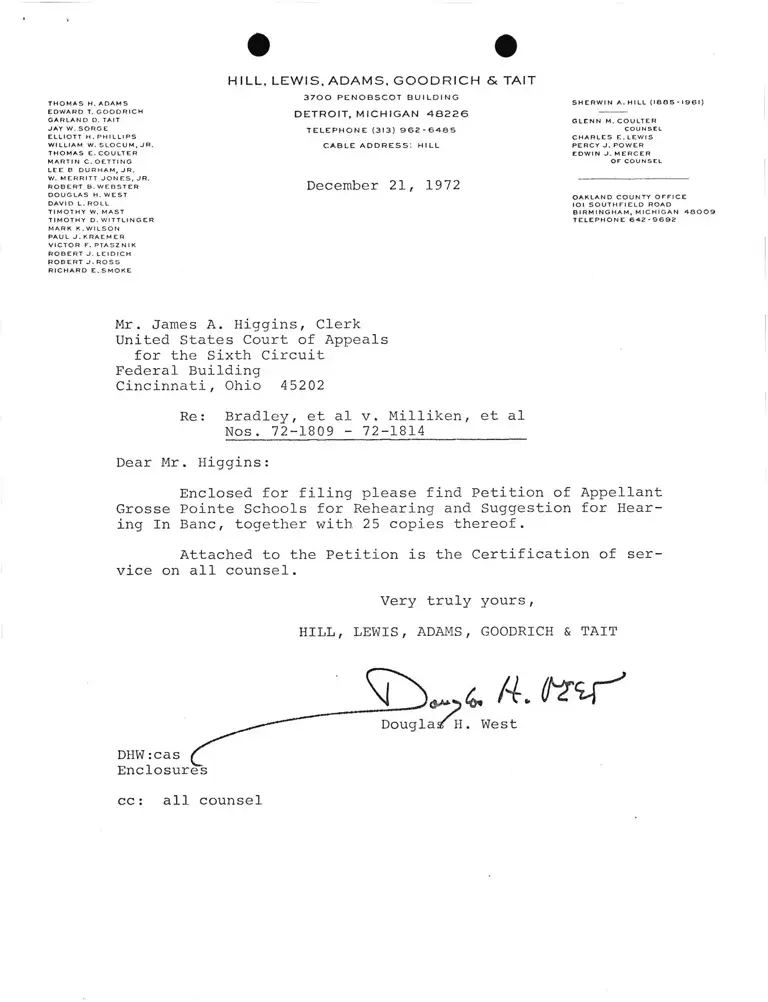

December 21, 1972

G L E N N M . C O U L T E R

C O U N S E L

C H A R L E S E . L E W I S

P E R C Y J . P O W E R

E D W I N J . M E R C E R

O F C O U N S E L

O A K L A N D C O U N T Y O F F I C E

I O I S O U T H F I E L D R O A D

B I R M I N G H A M , M I C H I G A N 4 8 0 0 9

T E L E P H O N E 6 4 2 - 9 6 9 2

M A R K K . W I L S O N

P A U L J . K R A E M E R

V I C T O R F. P T A S Z N I K

R O B E R T J . L E I D I C H

R O B E R T J . R O S S

R I C H A R D E . S M O K E

Mr. James A. Higgins, Clerk

United States Court of Appeals

for the Sixth Circuit

Federal Building

Cincinnati, Ohio 45202

Re: Bradley, et al v. Milliken, et al

Nos. 72-1809 - 72-1814

Dear Mr. Higgins:

Enclosed for filing please find Petition of Appellant

Grosse Pointe Schools for Rehearing and Suggestion for Hear

ing In Banc, together with 25 copies thereof.

Attached to the Petition is the Certification of ser

vice on all counsel.

Very truly yours

HILL, LEWIS, ADAMS, GOODRICH & TAIT

DHW:cas

Enclosures

cc : all counsel

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

IN THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

Nos. 72-1809 - 72-1814

RONALD BRADLEY, et al,

Plaintiffs-Appellees,

vs .

WILLIAM G. MILLIKEN, Governor of

Michigan, etc.; BOARD OF EDUCATION

OF THE CITY OF DETROIT,

Defendants-Appellants,

and

DETROIT FEDERATION OF TEACHERS

LOCAL 231, AMERICAN FEDERATION

OF TEACHERS, AFL-CIO,

Defendant-Intervenor-Appellee,

and

ALLEN PARK PUBLIC SCHOOLS, et al ,

Defendants-Intervenors-Appellants,

and

KERRY GREEN, et al,

Defendants-Intervenors-Appellees. /

PETITION OF APPELLANT GROSSE POINTE

SCHOOLS FOR REHEARING AND

SUGGESTION FOR HEARING IN BANC

INTRODUCTION

Now comes Grosse Pointe Schools, one of the Defendant

Intervenor school districts and an Appellant in this matter, and

respectfully petitions this Court for a rehearing of these appel

late proceedings and this Court's decision of December 8, 1972.

Grosse Pointe Schools further respectfully suggests that a re

hearing in banc would be appropriate under the circumstances of

this case.

Grosse Pointe Schools reserves and reaffirms its argued

position on each of the points presented by it in the Brief of In

tervenor School Districts, filed by it jointly with all other inter

vening school districts which were Appellants in this matter. Addi

tionally, Grosse Pointe Schools makes specific reference to and in

corporates herein by reference the Petitions for Rehearing currently

being filed in this matter by such other Appellant school districts,

as well as the Petition for Rehearing currently being filed by the

State Defendants.

Grosse Pointe Schools believes rehearing should be granted

for the following principal reasons:

1. Even assuming arguendo that the State of Michigan

has committed each of the constitutional violations described in

Section III(b) of the Court's decision, that such acts are causally

related in any way to de jure segregation in the Detroit School

System or in the Detroit Metropolitan area, is not supported by

the record.

2. The Court's decision affirming the inadequacy of a

Detroit only remedy and the necessity of a Metropolitan Plan of

desegregation is inconsistent with this Court's previous decisions,

as well as the decisions of other Federal Courts.

ARGUMENT

1. The Court has affirmed a finding that the "State

of Michigan", through the named State Defendants, committed five

specified constitutional violations:

(a) Pre-1962 supervision of discriminatory site

selections; ,

(b) Bonding authority discrimination;

(c) Transportation funds discrimination;

(d) Public Act 48;

(e) Approval of Transportation of Carver School students.

Although Grosse Pointe Schools disagrees that the specified actions

amounted to constitutional violations, it is assumed for purposes

of this argument that the Court is correct in such findings. Even

though assumed to be correct, however, Grosse Pointe Schools further

disagrees with the conclusions drawn therefrom. The Court has

found that the actions of the State Defendants "...are significant,

2

pervasive and' causally related to the substantial amount of segre

gation found in the Detroit school system...." (slip opinion, p.

49). This statement is simply not supported by the record in this

cause. There has been no showing whatsoever that these specific

acts of the State Defendants had any causal connection with the

segregation found to exist in the Detroit schools. The Court fur

ther stated: "the record contains substantial evidence to support

the finding...that segregation of the Detroit public schools...was

validated and augmented by the ...Michigan State Board action of

pervasive influence through the system." (slip opinion, p. 50).

To the contrary, it is submitted that the record is devoid of any

such evidence, except as the Court may have imputed other acts of

the Detroit Board of Education to the State Board of Education.

In addition to the absence of any evidence of a causal connection

between the actions of the State Defendants and segregation within

Detroit, the record is even more obviously lacking with respect to

the actions of the State Defendants and their effect throughout the

Metropolitan area. Indeed, the Plaintiffs' Complaint and the trial

before the District Court were limited solely to the issues of the

segregated conditions within the Detroit Public Schools. Because

the State of Michigan has plenary power over local school districts,

the Court found that it had the duty to disregard school district

boundary lines for the purpose of providing an effective desegregation

plan to eliminate the racial identifiability of the Detroit Schools.

The Court concluded:

3

"The- power to disregard such artifical barriers

is all the more clear where, as here, the State

has been guilty of discrimination which had the

effect of crediting a nd~~ma in tanning racial segre

gation along school district lines." (slip

opinion, p. 65, emphasis added)

Again, it is most respectfully submitted that the Court has read

into the record that which does not exist. The District Court

stated in its June 14, 1972 Order that:

"...the Court has taken n_o proofs with respect

to the establishment of the boundries of the

86 public school districts in the Counties of

Wayne, Oakland and Macomb..." (emphasis added)

No testimony was taken or evidence presented as to the effects of

the actions of the State Defendants upon the racial make-up of the

schools in the Detroit Metropolitan area. No testimony was taken

or evidence presented as to whether any school district other than

Detroit was de jure segregated as a result of the actions of the

State Defendants., Grosse Pointe Schools is aware of the statement

by the Court that its conclusions are amply supported by the record.

With all due respect to the Court, however, it has misapprehended

the content of the record to which it refers.

The actions of the State Defendants, if assumed to be

constitutional violations, related only to the operation of the

schools in the City of Detroit and there is nothing from the nature

of the actions themselves which could be presumed by the Court

to naturally or probably lead to or tend to cause a segregated

condition in one school district vis-a-vis surrounding school dis

tricts. In summary, even if it is assumed that all schools within

4

the Detroit school system are de jure segregated, either by action

of the Detroit Board of Education or the State Defendants, or both,

it is impossible to conclude from the record in this cause that

any segregation which the Court might find to exist was created or

maintained along school district lines as a result of actions of

the State Defendants.

2. The Court has affirmed the District Court's finding

that no "Detroit only" plan could achieve the desegregation of the

Detroit Public School System and it has quoted with approval the

District Court's findings of March 28, 1972 which hold that a

Detroit only plan would make Detroit a "racially identifiable"

system and that it would be "perceived as Black", thus making de

segregation impossible. The Court has further held that "big city

school systems for blacks surrounded by suburban school systems

for whites" is constitutionally impermissible and is a "problem"

which must be solved by disregarding school district boundary lines.

As stated above, the findings that actions of the State

Defendants had the effect of creating and maintaining racial segre

gation along school district lines are totally unsupported by the

record and patently erroneous. It is respectfully submitted that

this is a conclusion that has been begged from the Court's realiza

tion that there exists an enormous social problem which the Court

feels a compelling need to solve. In the Court's quest to find

evidence necessary to satisfy the clearly established propostion

that there must be a legally cognizable violation found to exist

5

as a prerequisite to the granting of equitable relief, the Court

has either presumed that the five areas of constitutional viola

tions found to have been committed by the State Defendants were

causally connected with the problem it wishes to solve, or the Court

has simply misapprehended what is contained in the record in this

regard. That Detroit is a predominately black school system and

that most suburban school districts are predominately white is un-

controvertable. That they would not be any the less "perceived" or

"identifiable" as black or white, or that there would not be any

the less a "problem", even if the alleged actions of the State had

never occurred, is also undeniable. Although the Court has sought

legal justification for judicial intervention in this case, it is

submitted that unless this Court is to abandon its previous decisions

in Dea-1 1 , Deal II , Goss , Davis , and most recently Mapp , the de

cision of this Court of December 8, 1972 should not stand as written.

The Court has emphasized that it does not consider school

district boundary lines as being sacrosanct or inviolate in the face

of a compelling need to remedy a deprivation of Constitutional rights.

We agree. Nor did we argue to the contrary in the Brief of the

Intervenor School Districts filed with the Court. What was argued,

however, was the proposition that in any event the remedy (disregard

ing district boundary lines) must be related to the wrong that has

been found to exist. This could not have been more clearly stated

than in Swann , at page 16:

1. Deal v. Cincinnati Bd. of Educ ., 369 F.2d 55 (CA6 , 19 6 6).

2. Deal v. Cincinnati Bd. of Educ., 419 F.2d 1387 (CA6, 1969).

3. Goss v. Bd. of Educ. of Knoxville, Tenn. , 444 F.2d 632

ICA6, 197ITT ~ '

4. Davis v. School Dist. of the City of Pontiac, 433 F .2d 573

Tc a g t t97Tt : ~ ..... . ~

5. Mapp v . Bd. of Educ. of Chattanooga, Slip Opinion, Oct. 11, 1972.

6. Swann v. Charlotte-Meaklenberg Bd. of Educ., 402 U.S. 1 (1.971) .

6

"...it is important to remember that judicial powers

may be exercised only on the basis of a constitu

tional violation. Remedial judicial authority does

not put judges automatically in the shoes of school

authorities whose powers are plenary. Judicial

authority enters only when local authority defaults.

...As with any equity case, the nature of the vio

lation determines the nature of the remedy." (emphasis

added)

The nature of the violation found to exist in this case had nothing

whatsoever to do with the Metropolitan remedy which the Court

wishes to impose, as a means of correcting the racial identifiability

of the black city school district vis-a-vis the white suburban dis

tricts. We do not believe that it could be seriously argued that the

demographic composition of the City of Detroit and its suburban

communities would be any different today if the discriminatory

acts alleged to have been committed by the State Defendants had

never taken place. Yet it is the demography of the entire Metro

politan Detroit area that has been made the subject of the Court's

equitable powers; not the effects of the State's Constitutional

violations (if any) which might ultimately be found to be causally

related to the acts of the State Defendants.

On October 11, 1972, this Court issued its decision in

Mapp v, Bd. of Educ. of Chattanooga, supra, in which the Court

approved a finding that certain schools in Chattanooga would not

be subject to a racial balance order because the District Court had

found that the racial imbalance with respect to such schools was

not the result of past or present discrimination. This Court held:

7

"We do not believe that Boards of Education can be

faulted for the residential patterns of a city,

or for the heavy concentration of black or white

population in certain areas, or for the mobility

of both races. These are matters over which the

school system has no control, neither does it have

authority to assume such control. It has always

been the practice in the American educational system,

until recently, to locate schools near residences,

and these schools have been known as neighborhood

schools. Neighborhood schools enabled parents of

children to participate in the school's operation,

enabled the children to engage in other activities

and to associate with their friends and neighbors,

and even to walk to and from school. Destruction of

the neighborhood school system deprives both parents

and their children of these advantages, and can even

lower the quality of education." (slip opinion,

p. 9)

It is respectfully submitted that this, and other portions of

the Court's decision in Mapp, are totally inconsistent with the

opinion of this Court in the instant matter. Indeed, the Court's

decision is inconsistent with its prior decision in this same

case7, wherein the Court stated:

"The issue in this case is not what might be a

desirable Detroit School Plan, but whether or

not there are constitutional violations in the

school system as presently operated, and, if

so, what relief is necessary to avoid further

impairment of constitutional rights."

The Court has apparently conclusively determined that

judicial relief on a metropolitan scale is in all events necessary

because anything less "...would result in an all black school

system immediately surrounded by practically all white suburban

7. Bradley v. Milliken, 438 F.2d 945 (CA6, 1970) at pg. 946.

8

school systems, with an overwhelmingly white majority population

in the total metropolitan area", (slip opinion, page 56). If this

is the case, and if this is the real underlying reason for the

Court's decision, it is respectfully submitted that, rather than

postulate the effects of isolated acts of Constitutional violations

by certain State agencies in an effort to conform the legal propo-

gsitions upon which the decision is based with the progeny of Brown /

the Court should declare the existence of a racial imbalance as

between schools in a single school district and as between several

school districts to constitute the constitutional violation per

9se.

CONCLUSION

Rule 35 of the Federal Rules of Appellate Procedure

provides that a rehearing in banc will not ordinarily be granted

except:

(1) When consideration by the full Court is necessary

to secure or maintain uniformity of its decisions, or

(2) When the proceeding involves a question of excep

tional importance.

On November 28, 1972, this Court granted a rehearing in banc

of the decision in Mapp, supra. Because of the inconsistency of

this Court's decision in the instant case with that of Mapp, as

well as other decisions of this Circuit cited above, it is

Brown v. Board of Educ . of Topeka, 347 U.S. 483 (1954) .

9. Cf. Spencer v. Kugler, 326 F.Supp. 1235 (N.J. 1971), aff'd.

404 U.S. 1027(1972).

9

apparent that rehearing in banc should be granted so that

uniformity of decisions within the Circuit may be maintained.

Additionally, the exceptional importance of this case is also

apparent. It involves novel and complex issues of first impres

sion in this Circuit, dealing with the education of almost 1,000,000

children and the potential expenditure of enormous amounts of public

funds to implement a Metropolitan plan of desegregation. The decision

of this Court of December 8, 1972 is, as frankly noted by the Court,

in direct conflict with the 4th Circuit in Bradley v. School Bd. of

Richmond, 462 F.2d 1058 (4th Cir. 1972), petition for cert, filed

41 U.S.L.W. 3211 (U.S. Oct. 5, 1972). The decision of this Court

is also in direct conflict with the 10th Circuit in Keyes v .

School District No. 1, Denver, Colorado (10th Cir. 1971) cert,

granted 404 U.S. 1036.

fully requests that this Court order this Appeal to be reheard

and it suggests that a rehearing before the Court sitting in banc

would be appropriate under the circumstances.

For the foregoing reasons, Grosse Pointe Schools respect-

Respectfully submitted,

HILL, LEWIS, ADAMS, GOODRICH & TAIT

December 21,

Dated:

Intervenor Grosse Pointe Schools

3700 Penobscot Building

Detroit, Michigan 48226

962-6485

10

CERTIFICATION

This is to certify that a copy of the attached Petition

of Appellant Grosse Pointe Schools for Rehearing and Suggestion for

Hearing In Banc, filed by the Grosse Pointe Public School System,

has been served upon counsel of record by United States Mail, pos

tage pre-paid, addressed as follows:

LOUIS R. LUCAS

WILLIAM E. CALDWELL

525 Commerce Title Building

Memphis, Tennessee 38103

WILLIAM M. SAXTON

JOHN B. WEAVER

1881 First National Bldg.

Detroit, Michigan 48226

NATHANIEL R. JONES

General Counsel, NAACP

1790 Broadway

New York, New York 10019

E. WINTHER MC CROOM

3245 Woodburn Avenue

Cincinnati, Ohio 45207

JACK GREENBERG

NORMAN J. CHACHKIN

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

J. HAROLD FLANNERY

PAUL R. DIMOND

ROBERT PRESSMAN

Center for Law & Education

Harvard University

Cambridge, Mass. 02138

DAVID L. NORMAN

Department of Justice

Washington, D.C. 20530

ROBERT J. LORD

8388 Dixie Highway

Fair Haven, Michigan 48023

RALPH GUY

United States Attorney

Federal Building

Detroit, Michigan 48226

EUGENE KRASICKY

GERALD YOUNG

Assistant Attorney General

Law Building

525 West Ottawa Street

Lansing, Michigan 48913

THEODORE SACHS

1000 Farmer

Detroit, Michigan 48226

ALEXANDER B. RITCHIE

1930 Buhl Building

Detroit, Michigan 48226

BRUCE A. MILLER

LUCILLE WATTS

2460 First National Building

Detroit, Michigan 48226

RICHARD P. CONDIT

Long Lake Building

860 West Long Lake Road

Bloomfield Hills, Mich. 48013

KENNETH B. MC CONNELL

74 West Long Lake Road

Bloomfield Hills, Mich. 48013

DONALD F. SUGERMAN

2460 First National Building

Detroit, Michigan 48226

THEODORE W. SWIFT

900 American Bank & Trust Bldg.

Lansing, Michigan 48933

FRED W. FREEMAN

CHARLES F. CLIPPERT

1700 N. Woodward Avenue

P. 0. Box 509

Bloomfield Hills, Mich. 48013

GEORGE T. ROUMELL, JR.

LOUIS D. BEER

7th Floor

Ford Building

Detroit, Michigan 48226

JOHN F. SHANTZ

222 Washington Square Bldg.

Royal Oak, Michigan 48067

ERWIN B. ELLMANN

1800 Penobscot Building

Detroit, Michigan 48226

CHARLES E. KELLER

1600 Penobscot Building

Detroit, Michgian 48226

Respectfully submitted,

HILL, LEWIS, ADAMS, GOODRICH & TAIT

Douglas H. West

3700 Penobscot Building

Detroit, Michigan 48226

Dated: December 21, 1972.