Slade v Harford County BOE Petition for Writ of Certiorari

Public Court Documents

February 12, 1958

48 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Slade v Harford County BOE Petition for Writ of Certiorari, 1958. 2eb406a9-c49a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/805c45ee-550c-4d63-a108-c0184909f1ef/slade-v-harford-county-boe-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari. Accessed January 29, 2026.

Copied!

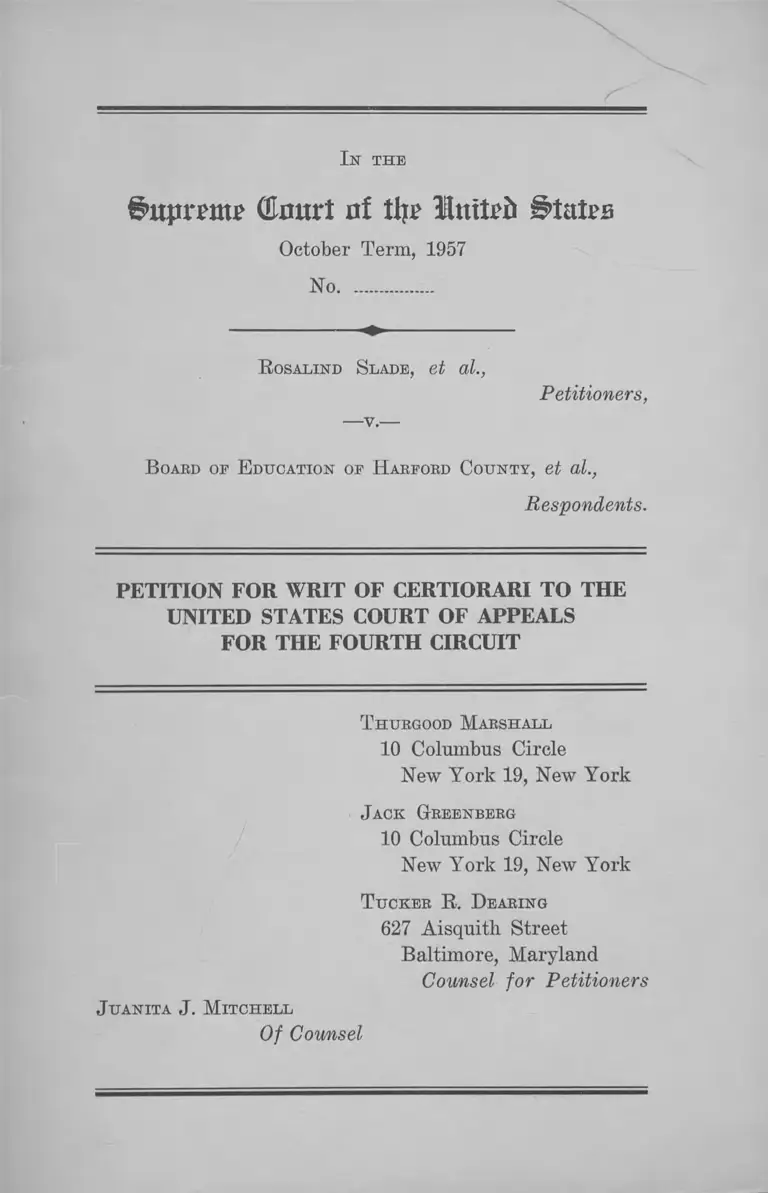

I n the

Supreme CEnurt of tlj? Hutted States

October Term, 1957

No............... .

R osalind Slade, et al.,

Petitioners,

—v.—

Board of Education of H arford County, et al.,

Respondents.

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

Thurgood Marshall

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

Jack Greenberg

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

T ucker R. Dearing

627 Aisquith Street

Baltimore, Maryland

Counsel for Petitioners

Juanita J. Mitchell

Of Counsel

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PAGE

Citations to Opinions Below............................................. 1

Jurisdiction ........................................................................ 2

Question Presented ........................................................... 2

Statement ............................................................................ 2

Reasons for Granting the Writ .................................... 8

The decision below conflicts with constitutional

principles established by this Court ...................... 8

There is a conflict among the Circuits ................ 14

Conclusion.......................................................................... 16

A ppendix ................................................................................ 17

Opinion of the Court of Appeals.............................. 17

Judgment .................................................................... 18

District Court Opinion of November 23, 1956 ....... 21

District Court Opinion of June 20, 1957................... 33

T a b l e op C a s e s :

Aaron v. Cooper, 243 F. 2d 361 (C. A. 8th, 1957) .... 14

Booker v. Tennessee Board of Education, 240 F. 2d

689 (6th Cir., 1957) cert. den. 353 U. S. 965 .............. 11,15

Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U. S. 294 .......9,14,15,16

Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S. 6 0 .................................. 9

Ill

PAGE

Universal Camera Corp. v. N. L. E, B., 340 U. S. 474 .. 13

Willis v. Walker, 136 F. Supp. 177 (W. D. Ky., 1955) .. 15

Statutes :

28 U. S. C. A., Section 1254(1) ..................................... 2

5 U. S. C. A., Section 1009(e) (B) (5) .......................... 8

15 U. S. C. A., Section 45(c) ............................................. 8

Other Authorities:

Southern School News, Nov., 1954 pp. 8-9 .................. 9

Southern School News, Dec., 1954 p. 7 .... ...................... 9

11

PAGE

Clemons v. Board of Education of Hillsboro, 228 F. 2d

853 (6th Cir., 1956) cert, denied 350 U. S. 1006 .......11,15

Dunn v. Board of Education of Greenbrier, 1 R. Rel.

L. Rep. 319 (S. D. W. Va. 1956) .................................. 14

Folds v. F. T. C., 187 F. 2d 658 (7th Cir., 1951) ........... 13

Garnett v. Oakley, 2 R. Rel. L. Rep. 303 (W. D. Ky.,

1957)................................................................................11,15

Gordon v. Collins, 2 R. Rel. L. Rep. 304 (W. D. Ky.,

1957) .............................................................................. 11,15

Jackson v. Rawdon, 235 F. 2d 93 (5th Cir., 1956) cert,

denied 352 U. S. 925 ............................................... 9

Lane v. Wilson, 307 U. S. 268, 275, 276-277 .................. 9,13

Lonesome v. Maxwell, 123 F. Supp. 193 (D. Md., 1954),

rev. sub nom. Dawson v. Maxwell, 220 F. 2d 386 (4th

Cir., 1955), aff’d 350 U. S. 877 .................................. 9

Mitchell v. Pollock, 2 R. Re], L. Rep. 305 (W. D. Ky.,

1957) ..............................................................................11,15

NAACP v. St. Louis & San Francisco Ry. Co., 297

I. C. C. 335, 345 (1955) ................................................ 10

O’Leary v. Brown-Pacific-Maxon, 340 U. S. 504 ........... 13

Pierce v. Board of Education of Cabell County (S. D.

W. Va., 1956, unreported) ........................................ 14

Shedd v. Board of Education of County of Logan, 1

R, Rel. L. Rep. 521 (S. D. W. Va., 1956) .................. 14

Taylor v. Board of Education of County of Raleigh, 1

R. Rel. L. Rep. 321 (S. D. W. Va., 1956) 14

In the

g>upnmte (Emtrt at f c Ittttpfr Btntm

October Term, 1957

No..................

Rosalind Slade, et al.,

—v.—

Petitioners,

Board of Education of H arford County, et al.,

Respondents.

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

Petitioners pray that a writ of certiorari issue to re

view the judgment of the United States Court of Appeals

for the Fourth Circuit entered in the above-entitled case

on February 12, 1958.

Citations to Opinions Below

The opinions of the District Court are reported at 146

F. Supp. 91 and 152 F. Supp. 114 sub nom. Moore v. Board

of Education of Harford County; the opinion of the Court

of Appeals is reported at 252 F. 2d 291. These appear in

the Appendix infra, at pp. 21, 33 and 17 respectively.

3

“ ‘any child regardless of race may make application to

the Board of Education to be admitted to a school other

than the one attended by such child, and the admis

sions to be granted by the Board of Education in ac

cordance with such rules and regulations as it may

adopt and in accordance with the available facilities

in such schools, effective for the school year beginning

September, 1956’ ” 146 E. Supp. at p. 93.

Counsel for the Board asserted “ ‘Since that plan em

braces the relief prayed for, I think that takes care of

that . . . ’ ” Id. at p. 94. Belying on the Resolution, peti

tioners agreed to dismiss. Ibid.

Subsequently, on August 1, 1956 respondents adopted a

“ Desegregation Policy.” It limited Negro applicants for

transfer to only the first three grades of two elementary

schools in the county. Id. at p. 95.

Petitioners, therefore, on August 28, 1956, filed a fresh

suit alleging that respondents were under a constitutional

duty to desegregate completely and that they were estop

ped from retreating from their original resolution. The

trial court remitted petitioners to an administrative remedy

before the State Board of Education.

The petitioners (including intervenors who were granted

leave to intervene, 152 F. Supp. at p. 115) filed an appeal

with the State Board. While it was pending respondents

again changed their policy on February 6, 1957. The new

policy provided that:

Applications for transfer will be accepted from pupils

who wish to attend elementary schools in the areas

where they live, if space is available in such schools.

Space will be considered available in schools that were

not more than 10% overcrowded as of February 1,

1957. All capacities are based on the state and national

2

Jurisdiction

The judgment of the Court of Appeals was entered on

February 12, 1958 (App. p. 17).1 The jurisdiction of this

Court is invoked under 28 U. S. C., Section 1254(1).

Question Presented

Whether respondent public school officials met the con

stitutional burden of demonstrating adherence to this

Court’s direction of proceeding “with all deliberate speed”

where their plan of desegregation—commencing in 1956

and extending to 1963—was delayed over that period of

time because of alleged community opposition, overcrowd

ing, and the so-called incapacity of all but specially cer

tified Negro students to adjust to high school if admitted

above the first year; while the record demonstrates that

there was adequate space for Negro students and that

white transferees above the first high school year need

not be so certified.

Statement

This cause has been in litigation since 1955. There have

been two connected suits involving four judicial hearings,

a court required appeal to the State Board of Education and

a number of hearings before local school officials. This cause

commenced with an earlier (separate) action, see 146 F.

Supp. 91, brought on behalf of some of the petitioners here

to desegregate the schools in Harford County. Two days

before that trial respondents adopted a resolution stating

that

1 “App.” refers to the Appendix to this petition. “App. R.”

refers to petitioner’s Appendix Record used below and filed as the

record with this petition.

5

respondents estopped from denying admission to named

plaintiffs in the first case and also ordered as follows

(see the judgment, App. p. 18):

Most of the county’s elementary classes were opened to

Negro children transfer-applicants in accordance with

specified transfer procedures which did not contemplate

use of a racial standard. For the school year 1958-1959,

Negro children might so transfer to three additional ele

mentary schools; for the school year 1959-1960, they might

transfer to still another three elementary schools and the

sixth grade in a high school. The 1959-1960 elementary

school change would mark the abolition of all racial re

strictions in transfers among elementary schools in the

county.

Desegregation of the county’s high and junior high schools

was scheduled to commence with a non-racial transfer

policy in September, 1958. Thereafter Negroes’ applications

for transfer without regard to race would be permitted to

the 8th grade in 1959; to the 9th grade in 1960; the 10th in

1961; 11th in 1962; the 12th in 1963. In 1963 and there

after all Negro applicants to classes are scheduled to be

admitted on the same basis upon which they would be

admitted if they were white.

At the same time the following other Negro applicants

might be permitted to transfer to high schools without

regard to race: those able to meet special qualifications

pertaining to probability of their individual success mea

sured by intelligence and achievement tests, grade level

achievements and other similar matters to be adjudged by

a committee consisting of the principals of the schools from

which the pupil is transferred and the school to which he

desires to transfer, the director of instruction and the

county supervisors working in the schools.

4

standard of thirty pupils per classroom. 152 F. Supp.

at p. 116.

Under the then newest plan five elementary schools and

the sixth grade in two schools were opened. Ibid.

The State Board held that the plan had been adopted in

good faith and constituted a reasonable start. Ibid.

At a hearing of this cause on April 18, 1957 the plan

of February 6 was amplified to include ten elementary

schools and the sixth grade in one school; as well as three

elementary schools as of September 1958, when contem

plated construction was projected to be completed. Three

elementary schools and the sixth grade of a high school

would commence receiving Negroes’ applications in Sep

tember, 1959.

At the April, 1957 hearing, the Court ruled tentatively

that the plan was “ generally satisfactory for the elementary

grades but not for the high school grades.” Ibid.

Another hearing was scheduled for June 11, 1957. On

June 5th, the Board changed its plan once more and noti

fied the parties of the change just before the hearing (App.

p. 39a). The new plan—consisting of additions to the old—

would permit Negro children to enter high school by a

route additional to that of the earlier plan (whereby they

could enter only through normal promotions from desegre

gated elementary schools). It would permit Negro children

to be admitted only after special examination and evalua

tion for admission to nonsegregated high schools, 152 F.

Supp. at 117.

This plan set forth below was incorporated into the

decree of the district court and approved by the Court of

Appeals judgment here under review. The trial court held

7

receive, and that “ after carefully considering all factors

at its disposal the committee is of the opinion that pro

vision can be made to accommodate such colored students

as apply for admission to Harford County public schools

for the year 1956 to 1957” (App. E. 44a). The record also

shows that during an earlier period of time when the school

board had authorized a plan which the court and plain

tiffs construed as permitting transfer of any applicant to

any grade without regard to race, about sixty Negro chil

dren made such application; most of these, however, were

rejected upon the adoption of other, more restrictive,

standards by the respondents which are assailed in this

case (App. E. 26a).

There are approximately 12,600 white and 1,400 Negro

students in the county (App. E. 26a).

Negro schools in the county were overcrowded in the

words of the Superintendent “ about like some of the others”

(App. E. 34a). “ [I ]f a white child applied to any of the

so-called overcrowded schools he would . . . have been ad

mitted” (App. E. 34a; see also App. E. 29a). And, of

course, he would have been admitted notwithstanding

problems of “pupil consciousness” or “ subject conscious

ness” whereby all but specially approved Negroes are

barred.

It will be noted that the high school “ stair-step” proce

dure, although formulated before the 1957 school year,

did not contemplate the transfer of Negro children to the

seventh grade without regard to race until the 1958 school

year. The school board offered no justification for this

other than, in the words of the Superintendent “ I can’t

say why, your Honor, but the policy was moving forward

three years, and that was all” (App. E. 36a).

As to whether there were administrative reasons for

desegregating only the 7th grade in 1958 and not the 8th

6

These criteria were to be applied only to Negro transfer

applicants; white students might transfer without regard

to these standards.

The Board took no steps to eliminate the situation in

which, apart from any other school assignment standard,

some schools are assigned solely to Negro children because

of their race. Their approach to the constitutional require

ment has been to maintain these schools while permitting

those Negro children who come forward to transfer out

if they come within the 1956-1963 plan.

The reasons advanced for deferring desegregation in

this manner were three: (1) there was alleged fear of

“ bitter local opposition,” 146 F. Supp. at p. 95, a recurrence

of events such as had occurred in Delaware2 * (App. R. 30a)

and perhaps riots (App. R. 37a). One application to a

school was refused, for example, “ [bjecause it was a par

ticularly sensitive spot.” (App. R. 33a); and see (App. R.

35a); (2) there was alleged overcrowding on an “ overall

average” (App. R. 33a); (3) it was stated that high schools

are subject-matter oriented unlike elementary schools which

are pupil-oriented; that entering high school above the

initial grade, during which associations and cliques form,

imposes a burden of adjustment on the transferee which

the faculty is not equipped to handle. 152 F. Supp. at p.

118.

A committee on facilities established by the school board

had surveyed the county schools, and as to overcrowding

had concluded that the overall capacity of Harford County

schools is such that eight of them could receive more than

500 students in excess of the number they expected to

2 Presumably referring to events in Milford, Delaware, which are

sketched in Shoemaker (ed.), With All Deliberate Speed 40-41

(1957).

9

The respondents herein failed to meet this burden. The

Courts below failed to follow or apply the standards set

out above. Of the problems enumerated by this Court only

alleged overcrowding has been preferred by respondents

as grounds for delay and the Record refutes this claim.

One cannot read the Record in this case without concluding

that respondents have endeavored, as assiduously as they

can, to continue the segregated pattern of schools with as

little change as possible for as long as they can.

1. We may exclude the alleged threats and intimidation

against desegregation as grounds for delay. Brown v.

Board of Education, 349 U. S. 294, 300; Jackson v. Rawdon,

235 F. 2d 93 (5th Cir., 1956) cert, denied 352 U. S. 925;

Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S. 60. Moreover, the State of

Maryland has made entirely clear that it will not at all

tolerate such lawlessness, Southern School News, Nov.,

1954 pp. 8-9; Dec., 1954 p. 7 (Baltimore disturbances

stopped).4

2. No one denies that until 1963 Negro children will

have to take tests not required of white children. No one

denies that abolition of formerly all Negro schools—so

constituted on a racial basis—is nowhere within the con

templation of respondents’ plan. In this context then we

may appropriately quote from Lane v. Wilson, 307 U. S.

268, 275, 276-2771

4 Intimations of illegal activity by this same trial court as

grounds for refusing desegregation of Maryland parks because,

allegedly, the “ degree of racial feeling or prejudice in this State

is probably higher with respect to bathing, swimming and dancing

than with any other interpersonal relations except direct sexual

relations,” Lonesome v. Maxwell, 123 F. Supp. 193 (D. Md., 1954),

rev. sub nom. Dawson v. Maxwell, 220 F. 2d 386 (4th Cir., 1955)’

aff’d 350 U. S. 877, have not been borne out by events. The Mary

land State Commission of Forests and Parks has ordered that

facilities under its jurisdiction “ henceforward [shall be conducted]

on an integrated basis.” 1 Race Rel. L. Rep. 971 (1956).

8

grade also, the Superintendent stated “Well, I won’t say

none, but at the moment, I don’t think of any big one; let’s

put it that way” (App. R. 37a).

Reasons for Granting the Writ

The decision below conflicts with constitutional

principles established by this Court.

In the School Segregation Cases this Court prescribed

the standards by which District Courts were to review

school board decisions on how and when to desegregate.3 *

The School Cases held that “ [t]he burden rests' upon the

defendants to establish that such time is necessary in the

public interest and is consistent with good faith compliance

at the earliest practicable date” 349 U. S. 294, 300. While,

of course, various questions of school administration may

be considered, such as “ problems related to administration,

arising from the physical condition of the school plant, the

school transportation system, personnel, revision of school

districts and attendance areas into compact units to achieve

a system of determining admission to the public schools

on a nonracial basis, and revision of local laws and regu

lations which may be necessary in solving the foregoing

problems,” 349 U. S. at pp. 300, 301, the overriding con

sideration obviously is “ the personal interest of the plain

tiffs in admission to public schools as soon as practicable

on a nondiscriminatory basis” 349 U. S. at p. 300.

3 These standards are unlike the typical rules for the review of

administrative determinations which are provided by the Federal

Trade Commission Act ( “ the findings of the Commission as to the

facts, if supported by evidence, shall be conclusive” ) 15 U. S. C. A.

Section 45(c) or the Administrative Procedure Act ( “ . . . the re

viewing court shall . . . hold unlawful and set aside agency action

. . . unsupported by substantial evidence . . .” ), 5 U. S. C. A. Sec

tion 1009(e) (B )(5 ).

11

Signs such as “white” and “ colored” , as displayed in

the Broad Street Station, are commonly understood

to represent rules established by managers of buildings

in which they are posted in the expectation that they

will be observed by persons having due regard for

the proprieties. It is reasonable to believe that such

was the original purpose of these signs, and that this

is still true, despite the Terminal’s acquiescence in

disregard of the signs. 297 I. C. C. 335, 345 (1955).

3. As to overcrowding, Respondent’s own Committee,

which made an intensive study of the situation, concluded

that the schools in question could accommodate such

Negroes as might apply; in fact only 60 did apply at a

time when the transfer standards purportedly allowed un

limited transfer, although under the amended restrictions

adopted by Respondents only 15 of these were actually ad

mitted. Negro schools too, were crowded.

Moreover, white children, transferring in from out of the

district would have suffered no restriction because of the

so-called crowding. At any rate, if there were a crowding-

problem a racial standard would be no way to treat it.

Clemons v. Board of Education of Hillsboro, 228 F. 2d 853

(6th Cir., 1956) cert, denied 350 U. S. 1006; Booker v. Ten

nessee Board of Education, 240 F. 2d 689 (6th Cir., 1957)

cert. den. 353 U. S. 965.5

4. The postponement because of the so-called “ subject-

matter-mindedness” of high schools becomes patently frivo-

5 See also Gordon v. Collins, 2 R. Rel. L. Rep. 304 (W . D. Ky.,

1957) (court rejecting alleged reasons for delay which included

overcrowding, transportation difficulties, reallocation problems,

need for time to study the problems, unfavorable social conditions;

the position of defendants is unreported); Mitchell v. Pollock,

2 R. Rel. L. Rep. 305 (W. D. Ky., 1957) (rejecting similar grounds

for delay) ; and see, for the same considerations and holding

Garnett v. Oakley, 2 R. Rel. L. Rep. 303 (W. D. Ky., 1957).

10

. . . The Amendment nullifies sophisticated as well

as simple-minded modes of discrimination. It hits

onerous procedural requirements which effectively

handicap exercise of the franchise by the colored race

although the abstract right to vote may remain un

restricted as to race.

# # # # *

. . . We believe that the opportunity thus given

negro voters to free themselves from the effects of

discrimination to which they should never have been

subjected was too cabined and confined. The restric

tions imposed must be judged with reference to those

for whom they were designed. It must be remembered

that we are dealing with a body of citizens lacking the

habits and traditions of political independence and

otherwise living in circumstances which do not en

courage initiative and enterprise. To be sure, in ex

ceptional cases a supplemental period was available.

But the narrow basis of the supplemental registration,

the very brief normal period of relief for the persons

and purposes in question, the practical difficulties, of

which the record in this case gives glimpses, inevitable

in the administration of such strict registration pro

visions, leave no escape from the conclusion that the

means chosen as substitutes for the invalidated “ grand

father clause” were themselves invalid under the Fif

teenth Amendment. They operated unfairly against

the very class on whose behalf the protection of the

Constitution was here successfully invoked.

The situation is like that of maintaining white and Negro

waiting rooms, appropriately designated by signs which,

however, may not be enforced by overt sanction which the

Interstate Commerce Commission condemned in NAACP

v. St. Louis and San Francisco By. Co.:

13

for the delay of one year are less satisfactory than the

reasons given for the rest of the plan, a federal court

should be slow to say that the line must be drawn here

and cannot reasonably be drawn there, where the dif

ference in time is short and individual rights are rea

sonably protected, during the transition period, as they

are by the June 5, 1957 modification. 152 F. Supp at

p. 119.

It is therefore apparent that respondents herein did not

meet the burden of establishing reasons for delay and that

the court for the most part acquiesced to so-called admin

istrative expertise. At best the board produced some evi

dence which, on the whole record, it may be doubted, would

have supported an ordinary administrative determination

where the presumptions are all on the side of the agency.

Cf. Universal Camera Corp. v. N. L. B. B., 340 U. S. 474;

Folds v. F. T. C., 187 F. 2d 658 (7tli Cir., 1951). But even

more than this, we are concerned not only with an appraisal

of the facts but a proper view of the law, cf. O’Leary v.

Brown-Pacific-Maxon, 340 IT. S. 504, involving as it does

“ the personal interest of the plaintiffs in admission to pub

lic schools as soon as practicable on a nondiscriminatory

basis” 349 II. S. at p. 300. Insufficient regard was paid to

the seriousness of this claim.

Constitutional rights were here subordinated to inef

fable considerations of policy without substantial factual

basis. The Court of Appeals in affirming and according the

normal deference to district court findings pyramided pre

sumption upon presumption.

As the plan now stands there are Negro children in the

county, including plaintiffs, who will never see a desegre

gated education unless they are examined and become

specially certified in a manner not required of white chil-

12

Ions when considered along with the fact that the special

certification requirement “may be applied only to Negro

students not qualified for admission under paragraph 4,”

i.e., the stair-step arrangement (App. E. 3 a ); white children

are not barred by this factor. If subject consciousness is a

valid ground for barring Negro transferees above the first

year (absent special certification) this would almost auto

matically convert all desegregation plans to at least 12

years: one can readily expect intransigent districts to call

their schools “ subject matter conscious” instead of “pupil

conscious” thereby justifying differential racial treatment.

The postponement of desegregation of the 7th and 8th

grades, as the Record indicates, was even without a pre

ferred reason. When asked what administrative considera

tions entered into such a decision the superintendent re

plied that there were none of significance. Petitioner sub

mits that the absence of even alleged reason for denying

these fundamental rights exposes the baselessness of the

other alleged justifications.

5. Although the trial judge recited that: “ the burden of

proof is on defendants to show that a delay during a transi

tion period is necessary, that the reasons for the delay are

reasons which the court can accept under the constitutional

rule laid down by the Supreme Court, and that the proposed

plan is equitable under all the circumstances,” 152 F. Supp.

at p. 118, its deference to the board’s determination appears

in its treatment of postponement of seventh grade desegre

gation :

My only doubt is whether it is necessary to postpone

until September, 1958, the complete desegregation of

the seventh grade. But I am not charged with the re

sponsibility of administering the Harford County pub

lic school system. Although I think the reasons given

15

parently not contradicted in tlie record as in the Harford

County case now before this court). It held that a seven-

year stair-step desegregation plan did not deny funda

mental Fourteenth Amendment rights.

On the other hand, an entirely different view has been

taken by the Sixth Circuit in Clemons v. Board of Educa

tion of Hillsboro, 228 F. 2d 853 (6tli Cir., 1956), cert, denied

350 U. S. 1006. The Court of Appeals held that where, as

here, white children were not denied admission because of

alleged overcrowding, desegregation could not be delayed

for that reason. While the Clemons case involved, in addi

tion to constitutional considerations, a question of validity

under state law, it is to be noted that the court’s opinion

rests principally on the importance of the constitutional

rights involved. Similarly, in Booker v. Tennessee Board of

Education, 240 F. 2d 689 (6th Cir., 1957), cert, denied

353 U. S. 965, a five-year stair-step plan involving Ten

nessee’s collegiate education was rejected. Alleged over

crowding was treated as a spatial problem, not a racial one.

The board, it was held, might act to remedy the situation

but could not treat it by a color standard. The Booker

case, while not involving elementary or high school educa

tion, applied the standards of Brown v. Board of Educa

tionJ

7 Cf. the following district court cases in this (the Sixth) circuit:

Willis v. Walker, 136 F. Supp. 177 (W. D. Ky., 1955) the court

pointed out that “no white children either before or after the

application for admission of the plaintiffs, were denied admission” ;

and that “ good faith alone is not the test. There must be ‘com

pliance at the earliest practicable date.’ ” 136 F. Supp. at p. 181.

Desegregation was ordered by the next school year. See also

Gordon v. Collins, 2 R. Rel. L. Rep. 304 (W. D. Ky., 1957); Mitchell

v. Pollock, 2 R. Rel. L. Rep. 305 (W. D. Ky., 1957); Garnett v.

Oakley, 2 R. Rel. L. Rep. 303 (W. D. Ky., 1957), (all summarily

described op. cit. supra, n. 5).

14

dren similarly situated. Given the history of the situation,

and the continued maintenance of formerly colored schools

as colored on solely a racial basis the deterrent effect of

this special requirement is obvious; Cf. Lane v. Wilson,

supra. At any rate the difference in treatment based on

race is express and unconstitutional.

There is a conflict among the Circuits.

The Courts of Appeal of the Fourth, Sixth and Eighth

Circuits have passed upon the constitutionality of desegre

gation plans. Moreover, a number of district courts in these

circuits also have passed upon this question. While from

the expectable disparity in factual situations and in trial

records the cases are not clearly comparable, there is a

substantial contrariety of views in application of the per

tinent constitutional principles among the courts. These

differences call for clarification by this Court of what it

meant by “ all deliberate speed” in Brown v. Board of

Education, 349 U. S. 294, 301, the implementation decision.

In the instant case, in essence, the trial court’s decision

was epitomized by extreme deference to the School Board’s

plan, with little or no support in the record." In the same

vein and cited by the Court of Appeals herein is Aaron v.

Cooper, 243 F. 2d 361 (C. A. 8th, 1957). This decision re

lied upon a complex of administrative considerations (ap-

6 In the Fourth Circuit a series of West Virginia District Court

cases involving plans, overcrowding, fiscal problems, and time for

consideration, have been rejected as grounds for delay when it was

clear that Negro children could be admitted notwithstanding the

proffered reasons for deferment. Shedd v. Board of Education of

County of Logan, 1 R. Rel. L. Rep. 521 (S. D. W. Va., 1956) ;

Dunn v. Board of Education of Greenbrier, 1 R. Rel. L. Rep. 319

(S. D. W. Va., 1956) ; Taylor v. Board of Education of County

of Raleigh, 1 R. Rel. L. Rep. 321 (S. D. W. Va., 1956); Pierce v.

Board of Education of Cabell County (S. D. W. Va., 1956, un

reported) .

17

APPENDIX

Opinion of the Court of Appeals

Per Curiam :

This is an appeal in a school segregation case involving

the public schools of Harford County, Maryland. The

school board of the county had adopted a plan for the

gradual desegregation of elementary schools over a two

year period and high schools over a period of five years.

At the suggestion of the District Judge, the plan was

amended to provide for the transfer of qualified students

in high school grades pending the final elimination of

segregation in those grades. As so amended the plan was

approved by the judge and a decree was entered enforcing

it and making special provision for the admission of two

Negro children who had been parties to a prior action. The

facts are fully set forth in the opinion of the District Judge,

and we think that his discretion was properly exercised

for reasons adequately stated in the opinion, to which noth

ing need be added. See Moore v. Board of Education of

Harford County, 152 F. Supp. 114. See also Allen et al. v.

County School Board of Prince Edivard County, Va., 4 Cir.

249 F. 2d 462, 465; Bippy v. Borders, 5 Cir. F. 2d ;

Aaron v. Cooper, 8 Cir. 243 F. 2d 361.

Affirmed.

16

CONCLUSION

The evil of racial segregation still permeates respon

dent’s plan. Little effort has been made towards faithfully

complying with this Court’s holding that state created racial

distinctions must be eliminated from public education.

Every effort has been made to continue the overall pattern

with as little desegregation as possible so that nonsegrega

tion would be the exception rather than the rule.

Noav, three years following this Court’s implementation

decision in Brown v. Board of Education, respondents

submit that it is time to clarify whether such departure

from prior segregation affords full equality which the

United States Constitution secures.

W herefore for the foregoing reasons it is prayed that

this petition for a writ of certiorari should be granted.

Respectfully submitted,

Thurgood Marshall

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

Jack Greenberg

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

T ucker R. Dearing

627 Aisquith Street

Baltimore, Maryland

Counsel for Petitioners

J uanita J. Mitchell

Of Counsel

19

the principal of the school the applicant attends. Such

applications will be reviewed at the regular June meeting

of the Board of Education. Applicants and their parents

will be informed of the action taken on applications prior

to the close of school in June of each year. In no event

shall a Negro child’s application for admission or transfer

be rejected if it would have been granted had he been

white.

4. A Negro child’s application for admission or transfer

to seventh grade classes commencing September, 1958, and

thereafter, under defendant’s control shall be considered

and granted on the basis upon which it would be considered

and granted if he were white. Such applications to the

following classes shall be so treated during and after the

year set forth alongside the class, as follows:

eighth grade — 1959

ninth grade — 1960

tenth grade — 1961

eleventh grade — .1962

twelfth grade — 1963

In 1963 and thereafter all Negro applicants to all classes

shall be admitted on the same basis upon which they would

be admitted if they were white.

5. Commencing September, 1957 applications for admis

sion or transfer by Negro children not qualified for admis

sion or transfer under paragraph 4 to high schools under

defendants’ control will be considered and granted if the

applicants fulfill special qualifications pertaining to the

probability of success of each individual pupil. These

qualifications will be measured by intelligence and achieve

ment tests, grade level achievements and other similar

matters to be adjudged by a committee consisting of the

principals of the schools from which the pupil is transfer-

18

Judgment

This cause having come on for final hearing by the court

without a jury on June 11, 1957 and the court having heard

all the evidence adduced and being fully advised in the

premises, it is hereby ordered, adjudged and decreed as

follows:

1. Defendants now and hereafter shall accept applica

tions for admission or transfer to all elementary classes

under their control (except in the schools named in para

graph 2 as to which applications will be accepted as de

scribed in that paragraph), in accordance with rules and

regulations set forth in paragraph 3 and every Negro child’s

application to classes governed by the instant paragraph

shall be considered and granted on the basis upon which

it would be considered and granted if he were white.

2. Defendants shall accept Negro children’s applications

for admission or transfer to Old Post Road, Bel Air and

Highland elementary schools for the school year 1958-1959

and thereafter; and shall accept Negro children’s applica

tions for admission or transfer to Forest Hill, Jarrettsville

and Dublin elementary schools and the sixth grade at Edge-

wood High School for the school years 1959-1960 and

thereafter. Every Negro child’s application to the schools

named in this paragraph for the respective school years

specified herein and thereafter shall be considered and

granted on the basis upon which it would be considered

and granted if he were white.

3. All applications for transfer to elementary classes

shall be made during the month of May on a regular

application form furnished by the Board of Education and

must be approved by the applicant’s classroom teacher and

21

District Court Opinion of November 23, 1956

T homsen, Chief Judge:

This action, brought by four Negro children seeking ad

mission to certain public schools in Harford County, Mary

land, present: (1) the usual questions under Brown v.

Board of Education, 347 U. S. 4S3, 74 S. Ct. 686, 98 L. Ed.

873; Id., 349 U. S. 294, 75 S. Ct. 753, 99 L. Ed. 1083; (2)

the same questions of law which were raised by the de

fendants in Robinson v. Board of Education, D. C. D. Md.,

143 F. Supp. 481; and (3) a problem of equitable estoppel

arising out of a previous action brought by the plaintiffs

herein and others against the defendants herein, which was

dismissed by the plaintiffs in reliance upon a resolution

adopted by the defendants, the Board of Education of Har

ford County.

F a c t s

Harford County is predominately rural, but in the

southern portion of the county there are two large govern

ment reservations, the Aberdeen Proving Ground at Aber

deen, and the Army Chemical Center at Edgewood. On

these reservations there are non-segregated housing de

velopments.

There are approximately 12,600 white students and 1,400

Negro students in the public schools of Harford County.

The defendant Board of Education operates a 6-3-3 sys

tem; that is, 6 years of elementary school, 3 years of jun

ior high and 3 years of senior high. The white high schools,

at Bel Air, Bush’s Corner (North Harford), Edgewood,

Aberdeen, and Havre de Grace, are combination junior-

senior high schools; the colored schools, at Hickory and

Havre de Grace, are “ consolidated schools” , comprising

elementary, junior high and senior high classes.

20

ring and the school to which he desires to transfer, the

Director of Instruction and the county supervisors work

ing in these schools. Apart from the fact that these condi

tions may be applied only to Negro students not qualified

for admission under paragraph 4 no racial distinction is

to be made in the administration of these tests and evalua

tions. Such applications may be made to the Board of

Education between July 1 and July 15 of 1957 and years

following in which these tests may be given.

6. Infant plaintiff Moore shall be admitted to the sixth

grade at the Bel Air School. Infant plaintiff Spriggs shall

be admitted to the eighth grade at Edgewood High School.

7. No racial distinctions whatsoever shall be made by

defendants in treating Negro children who have been ad

mitted to schools pursuant to this decree.

8. This Court retains jurisdiction for the purpose of

granting any other relief that may become necessary.

23

gated in their schooling because of race, violate the

Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Con

stitution.

“3. The Court issue preliminary injunctions order

ing the defendants to promptly present a plan of

desegregation to this Court which will expeditiously

desegregate the schools in Harford County and for

ever restrain and enjoin the defendants and each of

them from thereafter requiring these plaintiffs and all

other Negroes of public school age to attend or not to

attend public schools in Harford County because of

race.

“ The Court allow plaintiffs their costs and such

other relief as may appear to the Court to be just.”

On February 27, 1956, the Citizens Consultant Commit

tee held a meeting, at which all of the sub-committees pre

sented their final reports, and the full committee unani

mously adopted the following resolution:

“ To recommend to the Board of Education for Har

ford County that any child regardless of race may

make individual application to the Board of Education

to be admitted to a school other than the one attended

by such child, and the admissions to be granted by

the Board of Education in accordance with such rules

and regulations as it may adopt and in accordance

with the available facilities in such schools; effective

for the school year beginning September, 1956.”

On March 7, 1956, the Board of Education of Harford

County adopted the resolution as submitted by the Citizens

Consultant Committee.

On March 9, 1956, Civil Action No. 8615 came on for

hearing before me on defendants’ motion to dismiss the

22

On June 30, 1955, just one month after the second opin

ion in Brown v. Board of Education, the Board of Educa

tion of Harford County selected a Citizens Consultant Com

mittee of thirty-six members from all sections of the county,

five of whom were Negroes, to consider the problem of

desegregation of the public schools in Harford County

and to make recommendations to the Board of Education.

On July 27, 1955, a group of Negro parents petitioned

the Board of Education, calling upon them “ to take imme

diate steps to reorganize the public schools under your

jurisdiction on a nondiscriminatory basis.”

The Citizens Consultant Committee held its first meet

ing on August 15, 1955, and was split up into a number of

sub-committees, to consider facilities, transportation and

social relationships respectively. A member of the staff

of the Board of Education served as consultant to each sub

committee. The sub-committees met at various times dur

ing the rest of the year 1955 and the first two months of

1956.

On November 29, 1955, the four infant plaintiffs in the

instant case, together with seventeen other Negro children,

through their parents and next friends, brought suit in this

court against the defendants herein (Civil Action No. 8615),

alleging that the Board had “ refused to desegregate the

schools within its jurisdiction and has not devised a plan

for such desegregation,” and praying that:

“ 1. The court advance this cause on the docket and

order a speedy hearing of the application for prelimi

nary injunction and the application for permanent in

junction according to law and that upon such hearings:

“2. The Court enter preliminary and permanent

judgments that any orders, customs, practices, and

usages pursuant to which said plaintiffs are segre-

25

The following stipulation, signed by counsel for all par

ties, was filed in the case on the same day:

“Dismissal of Action

“ 1. This cause came to be heard in this Court on

motion to dismiss the 9th day of March, 1956.

“2. Defendants, by their counsel, presented to the

Court the attached Resolution of the Harford County

Citizens Consultant Committee, adopted by the Har

ford County Board of Education, as submitted, at its

regular meeting on March 7, 1956.

“3. Relying upon said resolution, as adopted, plain

tiffs hereby withdraw their complaint, and pray that

the same be dismissed, costs to be paid by plaintiffs.”

To this stipulation was attached a certified copy of the

resolution recommended by the Citizens Consultant Com

mittee and adopted by the Harford County Board of Edu

cation.

On June 6, 1956, the Board of Education adopted the fol

lowing “ Transfer Policy” , which all parties agree was

reasonable:

“If a child desires to attend a school other than

the one in which he is enrolled or registered, it will

be necessary for his parents to request a transfer.

Applications for transfer are available on request.

These requests should be addressed to the Board of

Education, c/o Superintendent of Schools, Bel Air,

Maryland. Applications will be received by the Board

of Education between June 15 and July 15, 1956.

All applications for transfer must state the reason

for the request, and must be approved by the principal

of the school which the pupil is now attending.

24

complaint, pursuant to Rule 12(b), Fed. Rules Civ. Proc.

28 U. S. C. A. At the beginning of the hearing, counsel for

defendants advised the court that the Board of Education

of Harford County had “approved or adopted” the recom

mendation offered by the Citizens Consultant Committee

and read the resolution into the record. He then said:

“ Since that plan embraces the relief prayed for, I think

that takes care of that, and I want to call that to Your

Honor’s attention.” Counsel for plaintiffs then said: “ We

are in a position to enter into a consent decree embody

ing the terms of this resolution. We would like to discuss

it, but I do not think there is any need for further litiga

tion.” Counsel for the defendants replied: “ I do not think

that the Court should enter a consent decree when the

relief prayed for is the policy adopted by the Board. 1

think the complaint should be dismissed in open court

because there is really nothing before the Court to effectu

ate.” I then left the bench so that counsel could discuss

the matter more freely. When court reconvened the fol

lowing colloquy took place:

“ Mr. Greenberg: We discussed this resolution that

has been adopted by the School Board and we have

told counsel for the defendants that we are sure they

are proceeding in good faith and this plan is accept

able to us, and we will dismiss our suit and make that a

matter of record in open court, and file this.

“Mr. Barnes: That’s agreeable to the defendants,

your Honor.

“ The Court: I think it would be well to have the

record show that in view of the fact that you have

been presented with this you offered to dismiss the

suit, and attach this paper as an exhibit.

“Mr. Greenberg: Yes, sir.

“ The Court: I am very happy this has worked out

in a very satisfactory way.”

27

local school problems. The resolution of the Harford

County Citizens Consultant Committee is in accord

with this principle. The report of this committee leaves

the establishment of policies based on the assessing

of local conditions of housing, transportation, person

nel, educational standards, and social relationships to

the discretion of the Board of Education.

“ The first concern of the Board of Education must

always be that of providing the best possible school

system for all of the children of Harford County.

Several studies made in areas where complete de

segregation has been practiced have indicated a lower

ing of school standards that is detrimental to all

children. Experience in other areas has also shown

that bitter local opposition to desegregation in a school

system not only prevents an orderly transition, but also

adversely affects the whole educational program.

“With these factors in mind, the Harford County

Board of Education has adopted a policy for a gradual,

but orderly, program for desegregation of the schools

of Harford County. The Board has approved applica

tions for the transfer of Negro pupils from colored to

white schools in the first three grades in the Edgewood

Elementary School and the Halls Cross Roads Ele

mentary School. Children living in these areas are

already living in integrated housing, and the adjust

ments will not be so great as in the rural areas of the

county where such relationships do not exist. With

the exception of two small schools, these are the only

elementary buildings in which space is available for

additional pupils at the present time.

“ Social problems posed by the desegregation of

schools must be given careful consideration. These

can be solved with the least emotionalism when younger

children are involved. The future rate of expansion

26

“Applications for transfer will be handled through

the usual and normal channels now operating under the

jurisdiction of the Board of Education and its execu

tive officer, the Superintendent of Schools.

“While the Board has no intentions of compelling

a pupil to attend a specific school or of denying him

the privilege of transferring to another school, the

Board reserves the right during the period of transi

tion to delay or deny the admission of a pupil to any

school, if it deems such action wise and necessary for

any good and sufficient reason.

“ All applications for transfer, with recommenda

tions of the Superintendent of Schools, will be sub

mitted to the Board of Education for final considera

tion at the regular meeting of the Board on Wednesday,

August 1, 1956. When requests for transfer are ap

proved, parents must enroll their child at the school

on the regular summer registration date, Friday, Au

gust 24, 1956.”

The transfer policy was advertised in all newspapers

published in Harford County. Sixty applications for trans

fer of Negro pupils were submitted within the time specified.

On August 1, 1956, the Board of Education of Harford

County adopted a “Desegregation Policy” , embodied in a

document which recited the appointment of the Citizens

Consultant Committee, the recommendation made by that

Committee, the resolution adopted by the Board of Educa

tion on March 7, 1956, and the transfer policy adopted by

the Board in June. The statement of Desegregation Policy

continued as follows:

“ The Supreme Court decision, which required de

segregation of public schools, provided for an orderly,

gradual transition based on the solution of varied

29

Garland seek transfer from the Havre de Grace Consoli

dated School to the Aberdeen High School (9th and 11th

grades respectively). They pray that:

“ 1. The Court advance this cause on the docket

and order a speedy hearing of the application for

preliminary injunction and application for permanent

injunction according to law and that upon such hear

ing;

“ 2. The Court enter preliminary and permanent

judgments, that any orders, customs, practices and

usages pursuant to which said plaintiffs are each of

them, their lesees, agents and successors in office

from denying to plaintiffs and other Negro residents

of Harford County of the State of Maryland admis

sion to any Public School operated and maintained

by the Board of Education of Harford County, on

account of race and color.” (sic)

Defendants tiled a motion to dismiss the complaint pur

suant to Rule 12(b), raising substantially the same points

which were considered in Robinson v. Board of Education

of St. Mary’s Comity, supra. I overruled that motion on

October 5, 1956. Defendants filed their answer on October

24, and the case was set for hearing on November 14. Both

sides offered testimony and documentary evidence. From

the testimony it appears that most, but not all, of the schools

in Harford County are overcrowded if the “ standards”

or “goals” set out by the State are considered, namely, an

average of 30 per class in elementary schools and 25 per

class in secondary schools. But defendants conceded that

any white children moving into the county would be ad

mitted to the appropriate white school, however crowded.

The factors considered by the Board of Education in adopt

ing the August 1 Desegregation Policy were discussed at

some length. The President of the Board of Education and

28

of this program depends upon the success of these

initial steps.”

Pursuant to the Desegregation Policy so adopted, fifteen

of the sixty applications were granted, and forty-five,

including those of the infant plaintiffs in the instant case,

were refused. On August 7, 1956, the defendant Charles

W. Willis, Superintendent of Schools, sent the following

letter to the parents of each of the infant plaintiffs:

“ The Board of Education, at its regular August

meeting, adopted a policy for the desegregation of

Harford County schools. Under the provisions of

this policy your child will not be allowed to transfer

from his present school. Your request for a trans

fer has been refused by the Board of Education.

“ A copy of the desegregation policy is enclosed.”

Neither the infant plaintiffs nor their parents appealed

to the State Board of Education from the action of the

County Superintendent denying their requests for transfer.

Nor have any appeals been filed by or on behalf of any of

the other Negro children whose requests for transfer were

refused.

On August 28, 1956, the four infant plaintiffs by their

parents and next friends filed the instant suit, pursuant to

Buie 23(a)(3), “ for themselves and on behalf of all other

Negroes similarly situated” , alleging most of the facts set

out above and other facts, some of which are disputed,

which need not be detailed at this time.

Infant plaintiff Moore seeks transfer from the Central

Consolidated Elementary School in Hickory to the elemen

tary school in Bel Air, where he resides; Spriggs seeks

transfer from the school in Hickory to the High School

(junior high) in Edgewood, where he resides; Slade and

31

“A. Defendants are administratively ready to ef

fectuate desegregation;

“B. ‘Community unreadiness’ constitutes no legal

justification for continued segregation.”

Discussion

[1] The Maryland statutes and decisions were analyzed

in Robinson v. Board of Education of St. Mary’s County,

supra, 143 F. Supp. at pages 487-491. I adhere to that

analysis, and it need not be repeated here. It is clear that

some of the factors considered by defendants in the instant

case when they adopted the August 1 Desegregation Policy,

and some of the points argued by counsel for plaintiffs in

opposition thereto, involve administrative problems, over

which the State Board of Education has jurisdiction, and

which should be appealed to that Board under the Maryland

authorities. Some of the other factors and points involve

legal questions, which under Maryland law are for the

courts. Most, if not all, involve both administrative and

legal problems. Even the estoppel point is a mixed ques

tion, because the March 7 resolution leaves open at least

the question of available facilities, whatever other matters

may have been foreclosed.

Whether the court should attempt to segregate the legal

questions and decide them at this time, or should defer any

decision until the State Board has been given an oppor

tunity to pass on the problem as an integrated whole, is a

matter of comity and discretion. Since, at the time of the

hearing in the St. Mary’s County case, the State Board

assured the court that it will give prompt attention to any

appeal filed by or on behalf of Negro students, I am satisfied

that I should not make a final decision in this case until

the plaintiffs have appealed to the State Board from the

action of the County Superintendent denying their applica-

30

the County Superintendent testified that they did not con

sult counsel before adopting the August 1 Desegregation

Policy, but that they thought this policy was in accord

with the recommendation of the Citizens Consultant Com

mittee and with the March 7 resolution adopted by the

Board.

Plaintiff’s counsel do not charge bad faith against either

the Board or the Superintendent, but contend that:

“ I. The Harford County School Board Resolution

of March 7, 1956, meant that from the following school

year and thereafter there would be no legally com

pelled racial segregation of school children in Harford

County;

“II. The defendants are estopped from any further

delay in complete integration by their action in caus

ing plaintiffs to withdraw plaintiffs’ original suit in

reliance on the Board’s resolution, which resolution

was expressly incorporated by reference into the court’s

order of dismissal;

“III. Plaintiffs are entitled to judicial rather than

administrative relief at this time in view of the history

and facts of this case;

“A. Defendants, by their actions, are estopped from

asserting the doctrine of administrative exhaustion as

a defense;

“ B. Even if defendants were not estopped from rais

ing the defense of the doctrine of administrative ex

haustion, the defense would nevertheless fail as the

doctrine is not here applicable;

“ IV. Even if defendants could validly raise the

questions of necessary administrative delay, their own

actions clearly demonstrate the fact that no additional

time is needed to solve administrative problems;

33

District Court Opinion of June 20, 1957

T homsen, Chief Judge:

This action was brought by four Negro children, on

their own behalf and on behalf of those similarly situated,

seeking admission to certain public schools in Harford

County, Maryland. The background and first stages of

the case are detailed in an opinion filed herein on Novem

ber 23, 1956, D. C., 146 F. Supp. 91.

Following that opinion, the four plaintiffs and eight

other children, who have asked and been granted leave

to intervene in this case, filed appeals with the State Board

of Education from the refusal of the Superintendent of

Schools of Harford County to grant their applications for

transfer from consolidated schools for colored children to

various white schools which were not desegregated in Sep

tember, 1956.

While those appeals were pending before the State

Board, on February 6, 1957, the Harford County Board

adopted the following “ Extension of the Desegregation

Policy for 1957-1958” :

“Applications for transfers will be accepted from

pupils who wish to attend elementary schools in the

areas where they live, if space is available in such

schools. Space will be considered available in schools

that were not more than 10% overcrowded as of

February 1, 1957. All capacities are based on the state

and national standard of thirty pupils per classroom.

“ Under the above provision, applications will be

accepted for transfer to all elementary schools ex

cept Old Post Road, Forest Hill, Bel Air, Highland,

Jarrettsville, the sixth grade at the Edgewood High

School, and Dublin. Such applications must be made

32

tions for transfer. Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U. S.

294, 75 S. Ct. 753; Hood v. Board of Trustees of Sumter

County School District No. 2, 4 Cir., 232 F. 2d 626; Carson

v. Board of Education of McDowell County, 4 Cir., 227 F.

2d 789; Robinson v. Board of Education of St. Mary’s

County, D. C. D. Md., 143 F. Supp. 481. However, the final

decision in this court, if one is necessary after the State

Board has acted, should be rendered within such time that

the losing parties may have an appeal heard by the Court

of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit at its June, 1957 term.

Conclusions

[2] 1. The appointment of the Citizens Consultant

Committee in the summer of 1955, its study, resulting in

its recommendation to the Board of Education, and the

resolution adopted by the Board on March 7, 1956, were

a prompt and reasonable start toward compliance with

the Supreme Court ruling.

2. I intimate no opinion at this time with respect to

the sufficiency or propriety of the Desegregation Policy

adopted by the Board on August 1,1956.

3. I will enter a decree dismissing this action unless

the plaintiffs appeal to the State Board of Education on

or before December 15, 1956, from the action of the County

Superintendent refusing their applications for transfer.

If plaintiffs enter such an appeal, I will stay further pro

ceedings in this case until the State Board shall have

decided the appeal or shall have delayed decision for an

unreasonable time; provided that after the State Board

shall have rendered its decision, or after March 1, 1957,

whichever is earlier, either plaintiffs or defendants may

request the court to set this case for further argument

and prompt decision.

35

intendent, explained and amplified the February 6, 1957

resolution of the County Board. The President of the

Board and its counsel accepted that interpretation. So

explained and amplified, the plan was substantially the

same as the plan which was later adopted by the County

Board on May 1, 1957, as follows:

“ The Board reviewed its desegregation policy of

February 6, 1957. In accordance with this plan, the

following elementary schools will be open in all six

grades to Negro pupils at the beginning of the 1957-

1958 school year:

“Emmorton Elementary School

“ Edgewood Elementary School

“ Aberdeen Elementary School

“Halls Cross Roads Elementary School

“ Perryman Elementary School

“ Churchville Elementary School

“ Youth’s Benefit Elementary School

“ Slate Ridge Elementary School

“ Darlington Elementary School

“ Havre de Grace Elementary School

“ 6th Grade at Aberdeen High School

“Schools now under construction or contemplated

for construction in 1958, if no unforeseen delays occur,

will automatically open all elementary schools to Negro

pupils by September, 1959. As a result of new con

struction, the elementary schools at Old Post Road, Bel

Air, and Highland will accept applications for transfer

of Negro pupils for the school year beginning in

September, 1958. Forest Hill, Jarrettsville, Dublin

and the sixth grade at the Edgewood High School

would receive applications for the school year begin

ning in September, 1959.

34

during the month of May on a regular application form

furnished by the Board of Education, and must be

approved by both the child’s classroom teacher and the

principal of the school the child is now attending.

“All applications will be reviewed at the regular

June meeting of the Board of Education and pupils

and their parents will be informed of the action taken

on their applications prior to the close of school in

June, 1957.”

After a hearing, the State Board dismissed the appeals,

finding that “the Harford County Board acted within the

policy established by the State Board” , that “ the County

Superintendent acted in good faith within the authority set

forth in the August 1, 1956, Desegregation Policy adopted

by the County Board” ,1 that the Desegration Policy was

adopted in a bona fide effort to make a reasonable start

toward actual desegregation of the Harford County pub

lic schools” , and that “ this initial effort [the desegrega

tion of three grades in two elementary schools] has been

carried out without any untoward incidents” . The State

Board also took “cognizance of the resolution of the County

Board of February 6, 1957”, set out above herein, “ as well

as the testimony to the effect that the proposed Harford

County Junior College, which is to be established in Bel Air

in the fall of 1957, will open on a desegregated basis, and

also the testimony to the effect that the present program

of new buildings and additions will make further desegre

gation possible” .

After the decision of the State Board, plaintiffs set this

case for further hearing, as provided in the earlier decree,

146 F. Supp. at page 98. That hearing was held on April

18, 1957. Charles W. Willis, the Harford County Super-

1 See 146 F. Supp. at page 95.

37

adjustment of each individual pupil, and the commit

tee will utilize the best professional measures of both

achievement and adjustment that can be obtained

in each individual situation. This will include, but

not be limited to, the results of both standardized

intelligence and achievement tests, with due considera

tion being given to grade level achievements, both

with respect to ability and with respect to the grade

into which transfer is being requested.

“ The Board of Education and its professional staff

will keep this problem under constant and continuous

observation and study.”

The modified plan was presented to the court at a hear

ing on June 11, 1957. It was made clear that when an

elementary school has been desegregated, all Negro chil

dren living in the area served by that school will have "the

same right to attend the school that a white child living

in the same place would have, and the same option to attend

that school or the appropriate consolidated school that a

white child will have. The same rule will apply to the high

schools, all of which operated at both junior high and senior

high levels, as they become desegregated, grade by grade.

Of course, the County Board will have the right to make

reasonable regulations for the administration of its schools,

so long as the regulations do not discriminate against any

one because of his race; the special provisions of the June

5, 1957 resolution will apply only during the transition

period.

[1] Willis also testified that the applications which will

be made pursuant to the June 5, 1957 modification will be

approved or disapproved on the basis of educational fac

tors, for the best interests of the student, and not for other

reasons. I have confidence in the integrity, ability and

fairness of Superintendent Willis and of the principals,

36

“As a normal result of this plan, sixth grade gradu

ates will be admitted to junior high schools for the

first time in September, 1958 and will proceed through

high schools in the next higher grade each year. This

will completely desegregate all schools of Harford

County by September, 1963.

“ The Board will continue to review this situation

monthly and may consider earlier admittance of Negro

pupils to the white high schools if such seems feasible.

The Board reaffirmed its support of this plan as ap

proved by the State Board of Education.”

At the April, 1957 hearing. I ruled tentatively that

the plan was generally satisfactory for the elementary

grades, but not for the high school grades, and suggested

that the parties attempt to agree on a modified plan. Con

ferences between counsel were held, but no agreement was

reached. The County Board, however, on June 5, 1957

modified the plan as follows:

“ The Board reaffirmed its basic plan for the de

segregation of Harford County Schools, but agreed

to the following modification for consideration of

transfers to the high schools during the interim period

while the plan is becoming fully effective.

“Beginning in September, 1957, transfers will be

considered for admission to the high schools of Har

ford County. Any student wishing to transfer to a

school nearer his home must make application to the

Board of Education between July 1 and July 15.

Such application will be evaluated by a committee

consisting of the high school principals of the two

schools concerned, the Director of Instruction, and

the county supervisors working in these schools.

“These applications will be approved or disap

proved on the basis of the probability of success and

39

it justifies the one or two years delay in desegregating the

seven schools.

With respect to the high schools, other factors are

involved. Superintendent Willis testified that when a child

transfers to a high school from another high school he

faces certain problems which do not arise when he enters

the seventh grade, which is the lowest grade in the Harford

County high schools. After a year or so in the high schools

social groups, athletic groups and subject-interest groups

have begun to crystallize, friendships and attachments have

been made, cliques have begun to develop. A child trans

ferring to the school from another high school does not have

the support of a group with whom he has passed through

elementary school. A Negro child transferring to an upper

grade at this time would not have the benefit of older

brothers, sisters or cousins already in the school, or parents,

relatives or friends who have been active in the P. T. A.

High school teachers generally, with notable exceptions,

are less “ pupil conscious” and more “ subject conscious”

than teachers trained for elementary grades, and because

each teacher has the class for only one or two subjects, are

less likely to help in the readjustment. The Harford County

Board had sound reasons for making the transition on a

year to year basis, so that most Negro children will have a

normal high school experience, entering in the seventh grade

and continuing through the same school. But I was un

willing in April to approve a plan which would prevent all

Negro children now in the sixth grade or above from ever

attending a desegregated high school.

However, the modified plan adopted on June 5, 1957,

permits any Negro child to apply next month for transfer

to a presently white high school, and if his application is

granted, to be admitted in September, 1957, three months

hence. This plan is different from any to which my atten-

38

supervisors and others who will make the decisions under

his direction. In the light of that confidence, I must decide

whether the modified plan meets the tests laid down in the

opinions of the Supreme Court and of the Fourth Circuit,2

with such guidance as may be derived from other decisions.3

The burden of proof is on defendants to show that a delay

during a transition period is necessary, that the reasons

for the delay are reasons which the court can accept under

the constitutional rule laid down by the Supreme Court, and

that the proposed plan is equitable under all the circum

stances. In considering whether defendants have met that

burden, the court must recognize that each county has a

different combination of administrative problems, tradi

tions and character. Many counties are predominantly

rural, others suburban; some have large industrial areas

or military reservations. See 146 F. Supp. at page 92.

[2] Eleven out of the eighteen elementary schools in

Harford County will be completely desegregated in Sep

tember, 1957, three months from now. Three more will be

completely desegregated in 1958, and the remaining four

in 1959. The reason for the delay in desegregating the

seven schools is that the county board and superintendent

believe that the problems which accompany desegregation

can best be solved in schools which are not overcrowded and

where the teachers are not handicapped by having too

many children in one class. That factor would not justify

unreasonable delay; but in the circumstances of this case

2 Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U. S. 294, 75 S. Ct. 753,

99 L. Ed. 1083; Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483, 74

S. Ct. 686, 98 L. Ed. 873; Carson v. Warlick, 4 Cir., 238 F. 2d 724;

Carson v. Board of Education of McDowell County, 4 Cir., 227

F. 2d 789.

3 Aaron v. Cooper, D. C. E. D. Ark., 143 F. Supp. 855; Kelley

v. Board of Education of the City of Nashville, M. D. Tenn., 2 Race

Rel. L. Rep. 21 (1957). Cf. Mitchell v. Pollock, W. D. Ky., 2 Race

Rel. L. Rep. 305 (1957).

41

[4] The March 7, 1956 resolution was somewhat am

biguous, but, as it was interpreted by defendants’ coun

sel in open court, plaintiffs were justified in believing, as

I did, that applications for transfer would be considered

without regard to the race of the applicant. The County

Board interpreted it differently in the statement entitled

“Desegregation Policy” adopted on August 1, 1956; see

146 F. Supp. at page 95. I cannot accept the interpreta

tion adopted by the County Board, but I find that it was

adopted as a result of a mistake and not as the result of

any bad faith on the part of the Board, the Superintendent,

or their counsel. The Board adopted the Desegregation

Policy of August, 1956, in the honest belief that it was to

the best interests of all of the children in the County.

Pursuant to that policy the Superintendent admitted

fifteen Negro children to two previously white schools,

but denied admission to forty-five others, including the

infant plaintiffs herein.

There is grave doubt whether a governmental agency

such as a county school board can be estopped from adopt

ing a policy, otherwise legal, which it believes to be in the

best interests of all the people in the County. In the instant

case it would be inequitable and improper, on the ground

of estoppel, to require the County Board to open all schools

to Negroes immediately, as requested in the complaint.

The County Board should not be foreclosed by the facts

which I have found from taking such actions, and adopt

ing and modifying such policies, as it believes to be in the

best interest of the people in the County, so long as those

actions and those policies are constitutional.