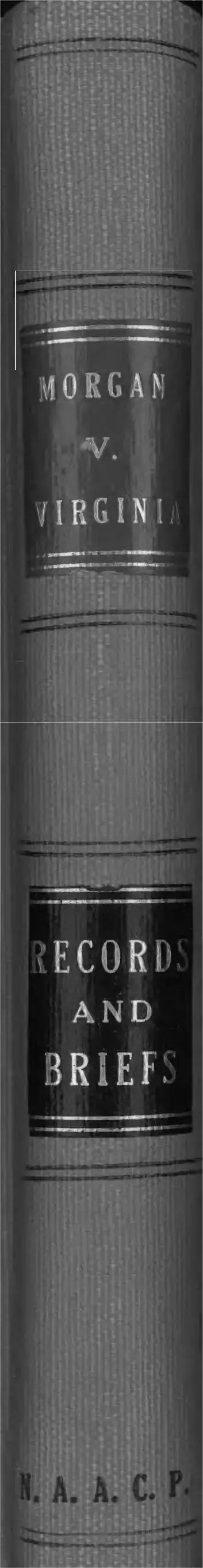

Morgan v. Virginia Records and Briefs

Public Court Documents

December 29, 1945

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Morgan v. Virginia Records and Briefs, 1945. 959e116c-ca9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/80c8b8ad-d776-4e00-9349-02a08e63dacf/morgan-v-virginia-records-and-briefs. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

MORGAN

w .

VIRGIN!

t-i ft

ECORD

A N D

B R I E F

TRANSCRIPT OF RECORD

Supreme Court of the United States

OCTOBER TERM, 1945

No. 704

IRENE MORGAN, APPELLANT,

vs.

COMMONWEALTH OF VIRGINIA

APPEAL PROM THE SUPREME COURT OF APPEALS OP THE STATE

OF VIRGINIA

FILED DECEMBER 29, 1945.

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

APPEAL FROM THE SUPREME COURT OF APPEALS OF THE STATE

OCTOBER TERM, 1945

No. 704

IRENE MORGAN, APPELLANT,

vs.

COMMONWEALTH OF VIRGINIA

OF VIRGINIA

IN D E X

Original Print

Proceedings in Supreme Court of Appeals of Virginia.............. 1 1

Petition for writ of e r r o r ....................................................................... 1 1

Errors assigned .................................................................................. 2 1

Questions involved ........................................................................... 3 2

Statement of facts ........................................................................... 3 3

Argument ............................................................................................. 7 7

Conclusion .................................................................................................. 22 23

Record from Circuit Court of Middlesex County............................ 23 24

Warrant and sheriff’s return............................................................ 23 24

Journal entry of hearing on appeal................................................ 26 26

Judgment entry ..................................................................................... 27 28

Order suspending execution of ju d gm en t................................... 29 30

Bill of Exception No. 1— Evidence........................................... 30 30

R. P. Kelly .................................................................................. 30 31

C. M. B r isto w .............................................................................. 36 37

R. B. Segar.................................................................................. 37 38

Irene Morgan .............................................................................. 39 40

Estelle F ie ld s .............................................................................. 42 44

Richard Scott ........................................................................... 44 45

W illie Robinson ....................................................................... 45 46

William Garnett ....................................................................... 45 47

Thomas Carter ......................................................................... 46 47

Rachel Goldman ....................................................................... 46 47

Ruby Catlett .............................................................................. 46 48

J udd & D etw eiler ( I nc . ) , P rin ters , W a sh in g to n , D . C., F ebruary 4, 1946.

— 2737

11 IN D EX

Record from Circuit Court of Middlesex County— Continued

Original

Bill of Exception No. 2— Motion to strike evidence............

Bill of Exception No. 3— Motion to set aside judgment. .

Bill of Exception No. 4— Motion in arrest of judgm ent..

Clerk’s certificate .............................................................................

Judgment, case of resisting arrest, October 18, 1944____

Opinion, Gregory, J......................................................................................

Judgment ......................................................................................................

Recital as to filing of petition for rehearing..................................

Order denying petition for rehearing................................................

Petition for appeal and assignments of error................................

Order allowing a p p e a l....................................................................

Bond on appeal........................................... (omitted in printing). .

Citation and serv ice ................................(omitted in printing). .

Praecipe for transcript of rec o rd .......................................................

Clerk’s certificate.......................................(omitted in printing). .

Statement of points to be relied upon and designation of rec

ord ...............................................................................................................

Designation by appellee of additional parts of record..............

Order noting probable jurisdiction....................................................

48

49

50

51

52

55

78

78

78

80

83

84

85

86

88

89

90

92

Print

49

50

52

53

54

56

68

69

69

69

71

72

74

75

76

1

[fol. 1]

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF APPEALS OF VIRGINIA

AT RICHMOND

Record No. 2974

I rene M organ

versus

Commonwealth of V irginia

Petition for Writ of Error

To the Honorable Judges of the Supreme Court of Appeals

of Virginia:

Your petitioner, Irene Morgan, respectfully represents

that on the 16th day of July, 1944, a warrant was issued

upon the oath of R. P. Kelly charging that, on the date

aforesaid, she did “ Unlawfully refuse to move back on the

Greyhound Bus in the section for colored people” ; that

whereupon she was tried in the Circuit Court of Middlesex

County without a jury, trial by jury having been waived,

upon an amended warrant charging that, on the date afore

said, she did “ Unlawfully refuse and fail to obey the direc

tion of the driver or operator of the Greyhound Bus Lines

to change her seat and to move to the rear of the bus and

occupy a seat provided for her, in violation of section 5 of

the Act, Micliie Code of 1942, section 4097dd” ; that where

upon the said Court found her guilty of said offense and

sentenced her to pay a fine of Ten ($10.00) Dollars, and

final judgment thereupon was entered on the 18th day of

October, 1944.

A transcript of the record in this case and of the judg

ment therein is herewith filed as a part of this petition.

[fol. 2] E rrors A ssigned

Your petitioner is advised and represents to your Honors

that the said judgment is erroneous, and that she is ag

grieved thereby in the following particulars, namely:

First. The action of the Court in overruling petitioner’s

motion, first made at the conclusion of the presentation of

the Commonwealth’s evidence-in-chief, to strike the evi-

1—704

2

dence of the Commonwealth and dismiss the case upon the

ground that the evidence introduced by the Commonwealth

was legally insufficient to sustain a conviction of the crime

charged in the amended warrant, upon which she was being

tried and that no judgment thereupon could lawfully be

rendered against her, for the following reasons, to-wit:

that the law upon which the prosecution was based could

not constitutionally be applied to her as she was, as shown

by the evidence, an interstate passenger traveling upon the

vehicle of an interstate public carrier, and that its applica

tion to such a passenger would be in violation of Article I,

Section 8, of the Constitution of the United States; and that

under settled rules of construction said law could not be

construed to apply to a passenger in interstate commerce,

and that it must be construed as limited in its operation to

passengers in intrastate commerce; which motion was re

newed and again overruled at the conclusion of the entire

case after both the Commonwealth and your petitioner had

rested.

Bill of Exception No. 2, Record, pp. 34-35.

Second. The action of the Court in overruling petitioner’s

motion to set aside said Court’s decision and judgment of her

guilt of the aforesaid offense, and to award her a new trial,

which motion was predicated upon the same grounds and

reasons aforesaid, and upon the additional ground and

reason that said decision and judgment of her guilt was

contrary to the evidence, and lacking in evidence sufficient

to support the same.

Bill of Exception No. 3, Record, pp. 36-37.

Third. The action of the Court in overruling petitioner’s

motion for a new trial, which motion was predicated upon

the same grounds and reasons aforesaid, and upon the addi

tional ground and reason that said Court’s decision and

judgment of her guilt was contrary to the evidence, and

lacking in evidence sufficient to support the same.

[fol. 3] Bill of Exception No. 4, Record, pp. 38-39.

Questions I nvolved in the A ppeal

These assignments of error present two questions:

First: Is the statute upon which petitioner was prose

cuted, if construed as applicable to a passenger in interstate

commerce, constitutional?

3

Second. Should the statute upon which petitioner was

prosecuted be construed as limited in its operation to pas

sengers in intrastate commerce, and, therefore, as inappli

cable to petitioner?

Statement of the F acts

In the statement of the facts and the argument, petitioner

will be referred to as the defendant, in accordance with the

position occupied by her in the trial court.

On July 16, 1944, defendant, who is a Negro or colored

person (R., pp. 9, 21), was a passenger upon a bus of the

Richmond Greyhound Lines, Inc. She boarded the bus at

Hayes Store, in Gloucester County, Virginia, and was

traveling to the City of Baltimore, Maryland (R., pp. 9, 21).

R. P. Kelly, an employee of the Greyhound Lines for six

years, was the driver in charge and control of the bus (R.,

pp. 9, 11, 21).

When the bus arrived in Saluda, Virginia, the driver per

ceived defendant and another colored woman, the latter

carrying an infant, seated in a seat forward of the long

seat in the extreme rear of the bus (R., pp. 9, 10). Defend

ant was requested by the driver to move from said seat,

and, upon her refusal so to do, the driver procured a war

rant charging the offense for which she was prosecuted in

the court below.

As to the condition of the bus, the events occurring and

the circumstances leading up to and surrounding defend

ant’s refusal to leave her seat, the testimony introduced by

the Commonwealth and the defendant, respectively, is in

hopeless conflict. Defendant concedes the binding effect

of the decision of the trial court in this regard, but submits

that as it was shown without contradiction that she and the

Greyhound Company were, respectively, interstate pas

senger and carrier, she could not be prosecuted for violating

the statute aforesaid upon the basis of either the Common

wealth’s or her own evidence.

The evidence of the Commonwealth, consisting chiefly of

the testimony of the bus driver, tended to show that at the

[fol. 4] time defendant’s removal from the seat was sought,

there were two vacancies on the long rear seat in the

extreme rear of the bus, which seat is designed to accommo

date five persons, and was then occupied by three colored

passengers; that all other seats in the bus were occupied;

4

that defendant and her seatmate were requested to move

back into these seats, the driver advising them that under

the rules of the bus company, he was required to seat white

passengers from the front of the bus backward and colored

passengers from the rear of the bus forward; that defend

ant refused to move, whereupon the driver procured a

warrant charging her with a violation of the segregation

law through her refusal to move.

On the other hand, defendant’s version, which was cor

roborated by the testimony of four other witnesses, includ

ing Estelle Fields, her seatmate, was that the seat in ques

tion became vacant when the bus stopped in Saluda; that

she then moved from the long rear seat which, from Hayes

Store to Saluda, had been occupied by six or seven passen

gers, including herself, into said seat, the latter being the

only vacant seat in the bus; that about five minutes later a

white couple boarded the bus, whereupon the driver ap

proached defendant and her seatmate and told them that

they must get up so that the white couple might sit down;

that she, the defendant, informed the driver that she was

willing to exchange the seat she occupied for another on

the bus, but was unwilling to stand, in reply to which the

driver stated that colored passengers would be seated only

after all white passengers had obtained seats that when

asked by defendant where she would sit if she relinquished

the seat she occupied the driver said nothing; that at the

time she was directed to move, there were no vacant seats

either on the long rear seat or elsewhere in the bus.

A second charge was lodged against the defendant as a

consequence of events which allegedly occurred when the

Sheriff and Deputy Sheriff of Middlesex came on the bus to

execute the warrant obtained by the bus driver. The claim

of the Commonwealth in this connection was that defendant

resisted said officers in the discharge of their duties. This

claim was substantially denied by defense witnesses, but

defendant was convicted of the second offense also. By

consent of the Commonwealth, the defendant, and the

Court, both charges were tried together (R., p. 3), but no

appeal from the conviction on the resisting charge was

taken.

It appeared without controversy that the sources of the

difficulties aboard the bus, whatever they may have been,

were the efforts to remove defendant from the seat which

5

she occupied. The bus driver admitted, that neither he nor

[fol. 5] anyone else on the bus had any difficulties whatso

ever with defendant until he sought to move her from her

seat (R., p. 16), and both the Sheriff and Deputy Sheriff

testified that defendant was in all respects orderly and well-

behaved and caused no trouble whatsoever until efforts w’ere

commenced to remove her from the seat (R., pp. 18, 20).

The driver also testified that under the rules of the bus

company all colored passengers were required to be seated

from the rear of the bus forward and that all white pas

sengers from the front of the bus backward, and that the

general custom and policy pursued by his company upon

buses traveling in or through the State of Virginia was to

assign seats to colored and white passengers in this manner

(R., p. 16), and so far as the record discloses, the sole

ground upon which defendant’s removal was sought and

effected was that she is a Negro.

That defendant, at the time she allegedly committed the

offense with which she was charged, and for which she was

convicted, was a passenger traveling in interstate com

merce upon the vehicle of an interstate public carrier, is

conclusively established by the uncontroverted evidence for

the Commonwealth as well as the defendant.

The Richmond Greyhound Lines, Incorporated, is regu

larly engaged in the business of transporting passengers

for hire and reward from points within the State of Vir

ginia to various points throughout the United States, in

cluding the City of Baltimore, Maryland, and was so en

gaged on July 16, 1944, the date upon which the events for

which defendant was prosecuted occurred (R., p. 12). Pas

sengers traveling to points outside the State of Virginia

are, and were, on this day, regularly taken aboard its buses

in Gloucester County, Virginia, including Hayes Store,

and transported therein to points outside the State of Vir

ginia (R., p. 12).

On July 15, 1944, defendant had purchased from the

regular agent of the Richmond Greyhound Lines, Incorpo

rated, at its ticket office at Hayes Store, Virginia, a through

ticket for transportation from Hayes Store to Baltimore,

Maryland (R., pp. 12,13, 21). The stub of this ticket, which

was introduced into evidence (R., p. 13), sets forth Hayes

Store as the point of departure and Baltimore as the point

of destination (R., p. 13). Defendant, as the holder of said

6

ticket, thereby became entitled to transportation from

Hayes Store, Virginia, to Baltimore, Maryland, in a Grey

hound bus (R., p. 12), and was entitled to transportation

between the points aforesaid on July 16, 1944, in the bus

upon which occurred the incidents out of which the prose

cution grew (R., p. 12).

Upon hoarding the bus at Hayes Store, for transportation

[fol. 6] to Baltimore, defendant surrendered the ticket and

R. P. Kelly, the driver, accepted the same (R., pp. 12, 21).

Kelly was personally driving and operating the bus from

the City of Norfolk, Virginia, to Baltimore (R., pp. 9, 11).

This bus regularly made and was on that day making a

continuous or through trip from Norfolk to Baltimore,

traveling by way of and through the City of Washington,

District of Columbia (R., pp. 11, 12).

After the arrest of defendant and her removal from the

bus, Kelly prepared a transfer or token, identified at the

trial by both Kelly (R., pp. 13, 14) and defendant (R., pp.

21, 22), in order that defendant might employ it for trans

portation from Saluda, Virginia, to Baltimore, Maryland,

or for a cash refund of the fare paid for that portion of

her trip between the said two points (R., p. 14). Kelly

punched this transfer at the appropriate places to show

Saluda as the point of beginning and Baltimore as the point

of ending of the incompleted portion of her trip (R., pp.

14, 15).

Kelly testified that he would not have prepared or issued

a transfer showing Saluda as the point of beginning and

Baltimore as the point of ending, unless defendant had held

a ticket entitling her to transportation on his bus to Balti

more (R., p. 15) ; and that he knew that all of the colored

passengers remaining on the bus in Saluda, after those

destined there had been discharged, held tickets to and were

traveling to Baltimore, Maryland (R., p. 15). Defendant-

testified that she had no intention of leaving the bus prior

to its arrival in Baltimore (R., p. 21).

At the conclusion of the presentation of the Common

wealth’s evidence-in-chief, defendant moved to strike the

evidence of the Commonwealth and to dismiss the case,

upon the ground that the evidence for the Commonwealth

was legally insufficient to sustain a conviction of the offense

with which she was charged, and that no judgment there

upon could lawfully be rendered against her, for the reason

that the statute upon which the prosecution was based

7

could not constitutionally be applied to her as she was, as

shown by the evidence, an interstate passenger traveling

upon the vehicle of an interstate public carrier, and that its

application to such a passenger would be in violation of

Article I, Section 8, of the Constitution of the United States,

and also for the reason that under settled rules of construc

tion said law could not be construed to apply to a passenger

in interstate commerce, and that it must be construed as

limited in its operation to passengers in intrastate com

merce (R., pp. 4, 20, 21, 34). At the conclusion of the entire

case, after both the Commonwealth and the defendant had

[fol. 7] rested, this motion was renewed (R., pp. 4, 5, 32,

33, 34, 35). After the Court had returned a finding that

defendant was guilty of the offense charged (R., p. 5), de

fendant moved to set aside said finding (R., pp. 5, 6, 36, 37),

and also moved for a new trial (R., pp. 6, 38, 39) upon the

same grounds and for the same reasons. Each of said

motions the Court overruled, to which action of the Court

defendant in each instance excepted. Final judgment was

entered sentencing defendant to pay a fine of $10.00 (R.,

pp. 6, 7).

A rgument

I

The Statute Upon Which the Prosecution was Based, if

Construed As Applicable to Defendant, a Passenger

in Interstate Commerce, Is Unconstitutional

and Void.

The Statutes Involved

In 1930, the General Assembly of Virginia enacted a

statute described by its title as “ An Act to provide for the

separation of white and colored passengers in passenger

motor vehicle carriers within the State; to constitute the

drivers of said motor vehicles special policemen, with the

same powers given to conductors and motormen of electric

railways by general law.” (Acts of Assembly, 1930, Chap.

128.)

This statute, now appearing as Sections 4097z to 4097dd

of Micliie’s Code of Virginia, 1942, requires all passenger

motor vehicle carriers to separate the white and colored

passengers in their motor busses, and to set apart and

\

designate in each bus seats or portions thereof to be occu

pied, respectively, by the races, and constitutes the failure

and refusal to comply with said provisions a misdemeanor

(Sec. 4097z); forbids the making of any difference or dis

crimination in the quality or convenience of the accommo

dations so provided (Sec. 4097aa); confers the right and

obligation upon the driver, operator or other person in

charge of such vehicle, to change the designation so as to

increase or decrease the amount of space or seats set apart

for either race at any time when the same may be necessary

or proper for the comfort or convenience of passengers so

to do; forbids the occupancy of contiguous seats on the

same bench by white and colored passengers at the same

time; authorizes the driver or other person in charge of the

vehicle to require any passenger to change his or her seat

[fol. 8] as it may be necessary or proper, and constitutes

the failure or refusal of the driver, operator or other person

in charge of the vehicle, to carry out these provisions a

misdemeanor (Sec. 4097bb); constitutes each driver, oper

ator, or other person in charge of the vehicle, while actively

engaged in the operation of the vehicle, a special policeman,

with all of the powers of a conservator of the peace in the

enforcement of the provisions of this statute, the mainte

nance of order upon the vehicle, and while in pursuit of

persons for disorder upon said vehicle, for violating the

provisions of the act, and until such persons as may be

arrested by him shall have been placed in confinement or

delivered over to the custody of some other conservator of

the peace or police officer, and protects him against the

consequences of error in judgment as to the passenger’s

race, where he acts in good faith and the passenger has

failed to disclose his or her race (Sec. 4097cc). Section

4097dd, upon which the prosecution in this case was based,

reads as follows:

“ All persons who fail while on any motor vehicle carrier,

to take and occupy the seat or seats or other space assigned

to them by the driver, operator or other person in charge of

such vehicle, or by the person Avliose duty it is to take up

tickets or collect fares from passengers therein, or who fail

to obey the directions of any such driver, operator or other

person in charge, as aforesaid, to change their seats from

time to time as occasions require, pursuant to any lawful

rule, regulation or custom in force by such lines as to assign-

8

9

ing separate seats or other space to white and colored

persons, respectively, having been first advised of the fact

of such regulation and requested to conform thereto, shall

be deemed guilty of a misdemeanor, and upon conviction

thereof shall be fined not less than five dollars nor more than

twenty-five dollars for each offense. Furthermore, such

persons may be ejected from such vehicle by any driver,

operator or person in charge of said vehicle, or by any

police officer or other conservator of the peace; and in case

such persons ejected shall have paid their fares upon said

vehicle, they shall not be entitled to the return of any part

of same. For the refusal of any such passenger to abide by

the request of the person in charge of said vehicle as afore

said, and his consequent ejection from said vehicle, neither

the driver, operator, person in charge, owner, manager nor

bus company operating said vehicle shall be liable for

damages in any court. ’ ’

[fol. 9] The Defendant’s Contention

Defendant is unconcerned with the applicability of the

statute aforesaid to passengers whose journeys commence

and end within the state. Nor does she base her contention

of invalidity upon a claim of inequality or inferiority

in the accommodations afforded members of her race.

Her position is that since it appears without controversy

that she was a passenger in interstate commerce upon an

interstate carrier, the statute could not constitutionally

apply, and therefore affords no basis for her prosecution.

Such Statutes Are Unconstitutional and Void When Appli

cable to Interstate Passengers

That state laws of the kind upon which this prosecution

was based cannot be permitted to operate upon interstate

commerce is apparent from principles too well known and

settled to require citation of authority.

In recognition of the necessity of uniformity through

national control in the regulation of commerce among the

states, the Constitution of the United States, in Article I,

Section 8, confers the regulatory power upon Congress and

invests it with power to determine what these regulations

shall be. Whenever the subject matter of regulation is

in its nature national, and admits of only one uniform

10

system or plan of regulation, the power of Congress is

exclusive, and cannot be encroached upon by the states.

There is no room for the operation of the police power of

the state where the legislature passes beyond the exercise

of its legitimate authority and undertakes to regulate in

terstate commerce by imposing burdens upon it.

It has therefore been flatly declared by the highest Court

in the land that legislation which seeks to direct the inter

state carrier with respect to the policy which it is to pursue

in transporting the races is unconstitutional and void.

Halil v. DeCuir, 95 U. S. 485, 24 L. Ed. 547 (1877).

In that case the defendant was the owner of a steam

boat licensed under Federal law for the coasting trade

plying between New Orleans, Louisiana, and Vicksburg,

Mississippi, and touching at intermediate points within

and without Louisiana. Plaintiff, a Negro, took passage

from New Orleans to Hermitage, Louisiana. Upon being

refused a place in a cabin set apart by defendant for ex

clusive occupancy by white persons, plaintiff brought an

action for damages under the Louisiana Act of 1869, which

[fol. 10] prohibited “ discrimination” because of race or

color, and provided a right of action to recover damages.

The defense was that the statute was inoperative as re

gards the defendant because, as to him, it was an attempt

to regulate commerce among the states. The trial court

gave judgment for the plaintiff, which was affirmed by

the Supreme Court of Louisiana. In the Supreme Court

of the United States, the judgment was reversed. The

Court pointed out that the state court had construed the

statute and held that it applied to interstate commerce,

and that it guaranteed a passenger in interstate commerce

equal rights and privileges in all parts of the conveyance,

without discrimination on account of race or color, and

that this construction was binding upon the Supreme Court

and therefore excluded from the case all questions concern

ing its application to intrastate passengers. The Court,

by Chief Justice Waite, said:

‘ ‘ But we think it may safely be said that state legislation

which seeks to impose a direct burden upon interstate com

merce, or to interfere directly with its freedom, does en

croach upon the exclusive power of Congress. The statute

now under consideration in our opinion occupies that posi-

11

tion. * * * While it purports only to control the car

rier when engaged within the state, it must necessarily

influence his conduct to some extent in the management

of his business throughout his entire voyage. His dispo

sition of passengers taken up and put down within the

State, or taken up to be carried without, cannot but affect

in a greater or less degree those taken up without and

brought within, and sometimes those taken up and put down

without. A passenger in the cabin set up for the use of

whites without the state must, when the boat comes within,

share the accommodations of that cabin with such colored

persons as may come on board afterwards if the law is

enforced. It was to meet just such a case that the com

mercial clause in the Constitution was adopted. * * *

Each state could provide for its own passengers and regu

late the transportation of its own freight, regardless of

the interests of others— * * * On one side of the river

or its tributaries he might be required to observe one set

of rules, and on the other another. Commerce cannot flour

ish in the midst of such embarrassment. No carrier of

passengers can conduct his business with satisfaction to

himself, or comfort, to those employing him, if on one side

of a State line his passengers, both white and colored,

must be permitted to occupy the same cabin, and on the

other be kept separate. Uniformity in the regulations by

[fol. 11] which he is to be governed from one end to the

other of his route is a necessity in his business.”

Pointing out that the exclusive legislative power, as re

spects interstate commerce, rests in Congress, the Court

further said:

“ This power of regulation may be exercised without

legislation as well as with it. By refraining from action,

Congress, in effect, adopts as its own regulations those

which the common law or the civil law, where that prevails,

has provided for the government of such business.”

It was further held that Congressional inaction left the

carrier free to adopt reasonable rules and regulations, and

the statute in question sought to take away from him that

power. It was therefore concluded that

“ If the public good require such legislation it must come

from Congress and not from the States.”

12

Mr. Justice Clifford, in a concurring opinion, pointed out

that

“ Unless the system or plan of regulation is uniform, it

is impossible of fulfillment. Mississippi may require the

steamer carrying passengers to provide two cabins and

tables for passengers, and may make it a penal offense for

white and colored persons to be mixed in the same cabin or

at the same table. If Louisiana may pass a law forbidding

such steamer from having two cabins and two tables—one

for white and the other for colored persons—it must be

admitted that Mississippi may pass a law requiring all

passenger steamers entering her ports to have separate

cabins and tables, and make it penal for white and colored

persons to be accommodated in the same cabin or to be

furnished with meals at the same table. Should state legis

lation in that regard conflict, then the steamer must cease

to navigate between ports of the states having such con

flicting legislation, or must be exposed to penalties at every

trip.”

The same reasons which operated to destroy the consti

tutionality of the statute there involved operate equally

to render unconstitutional legislation which seeks to compel

a separation of interstate passengers upon a racial basis.

Consequently, notwithstanding decisions in two states to

the contrary, which have elsewhere been disapproved,

[fol. 12] Illinois Central Railroad Company v. Redmond,

119 Miss. 765, 81 S. 115 (1919);

Southern Railway Co. v. Norton, 112 Miss. 302, 73 S. 1

(1916);

Alabama & Vicksburg Ry. Co. v. Morris, 103 Miss. 511,

60 S. 11 (1912) ;

Smith v. State, 100 Tenn. 494, 49 S. W. 566 (1900);

the conclusion has been uniformly reached in the federal

courts, and in the majority of state courts, that statutes

requiring separate accommodations for white and Negro

passengers are unconstitutional when applied to interstate

passengers.

Washington, R. & A. Elec. R. Co. v. Waller, 53' App. D.

C. 200, 289 F. 598, 30 A. L. E. 50 (1923);

Thomphins v. Missouri, K. & T. Ry. Co. (C. C. A. 8th)

211 F. 391 (1914);

13

McCabe v. Atchison, T. & S. F. Ry. Co. (C. C. A. 8th)

186 F. 966 (1911);

Anderson v. Louisville & N. R. Co. (C. C. Ivy.), 62 F. 46

(1894);

Brown v. Memphis C. R. Co. (C. C. Tenn.), 5 F. 499

(1880);

State v. Galveston H. £ S. A. Ry. Co. (Tex. Civ. App.),

184 S. W. 227 (1916);

Huff v. Norfolk & S. R. Co., 171 N. C. 203, 88 S. E. 344

(1916);

State v. Jenkins, 124 Md. 376, 92 A. 773 (1914);

Hart v. State, 100 Md. 596, 60 A. 457 (1905);

Carrey v. Spencer (N. Y. Sup. Ct.), 36 N. Y. S. 886 (1895);

State ex rel. Abbott v. Hicks, 44 La. Ann. 770, 11 S. 74

(1892).

Such also has been the position of the Supreme Court of

the United States where the same opinion has, in decisions

subsequent to Hall v. DeCuir, been intimated or assumed.

McCabe v. Atchison, T. & S. F. Ry. Co., 235 U. S. 151, 35

S. Ct. 69, 59 L. Ed. 169 (1914);

Chiles v. Chesapeake do 0. Ry. Co., 218 U. S. 71, 30 S. Ct.

667, 54 L. Ed. 936 (1910);

Chesapeake & 0. Ry. Co. v. Kentucky, 179 U. S. 388, 21 S.

Ct. 101, 45 L. Ed. 244 (1900);

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U. S. 537,16 S. Ct. 1138, 41 L. Ed.

256 (1896);

[fol. 13] Louisville, N. 0. & T. Ry. Co. v. Mississippi, 133

U. S. 587, 10 S. Ct. 348, 33 L. Ed. 784 (1890).

In McCabe v. Atchison, Topeka & S. F. Ry. Co., supra, the

Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals was faced with the 1907

Oklahoma statute which required separate coaches and

waiting rooms for white and colored passengers, and pro

vided penalties for its violation by either the passengers or

the carrier. Before the act went into effect, five Negro citi

zens of Oklahoma brought a suit in equity against five rail

road companies to enjoin them from making racial distinc

tions upon the ground, inter alia, that the statute was re

pugnant to the commerce clause of the Federal Constitu

tion. In holding that the act would be unconstitutional if

applicable to interstate passengers, the Court said:

“ It may be conceded that, if it applies to interstate trans

portation, it is a regulation of interstate commerce within

14

the meaning of the Constitution. We think this follows

from the doctrine laid down by the Supreme Court in Hall

v. DeCuir, 95 U. S. 485, 24 L. Ed. 547. * * * For like

reasons, the Oklahoma law, if as properly construed, it

embraces or relates to interstate commerce, at all, would

also be a regulation of that commerce. It compels carriers

when operating in that state to exclude colored persons

from cars or compartments set apart for white persons.

The only difference between the Louisiana and the Okla

homa law is that the one compels carriers to receive into

and the other to exclude colored persons from cars or com

partments carrying white persons. They act alike directly

upon the carrier’s business as its passenger crosses the

state line. Hence, if one is a regulation of interstate com

merce, the other must be. The contention, therefore, that

the provisions of the Oklahoma statute do not amount to a

regulation of interstate commerce, if they concern that com

merce at all, is untenable. ’ ’

Likewise, in State ex rel. Abbott v. Hicks, supra, the de

fendant, a Pullman official, was prosecuted for violation of

the 1890 Louisiana act requiring separate coaches for the

races. There was a plea to the jurisdiction and a motion to

quash the information on the ground that the passenger

involved was an interstate passenger. The lower court sus

tained a demurrer to the plea and motion, and the defendant

took the case to the Supreme Court of Louisiana on certio

rari, where the judgment was reversed. This court, con

struing the decision in Louisville, New Orleans & Texas

Ry. Co. v. Mississippi, supra, held:

[fol. 14] “ The terms of the decision left no doubt that the

Court (Supreme Court of the United States) regarded the

statute as unconstitutional if it applied to interstate pas

sengers, and only upheld it because construed by the Su

preme Court of Mississippi as applicable only to domestic

passengers. * * * These decisions leave no room for

question that the jurisprudence of the United States Su

preme Court holds such statutes as the one here presented

to be only valid in so far as they apply to domestic trans

portation of passengers or goods, and that, as applicable to

interstate passengers or carriage, they are regulations of

interstate commerce, prohibited to the states by the con

stitution of the United States.”

Again, in Huff v. Norfolk & Southern R. Co., supra, plain

tiff, a white deputy sheriff who was carrying a Negro

15

prisoner from Norfolk, Virginia, to Newbern, North Caro

lina, was compelled by defendant to ride in a coach on de

fendant’s train maintained for the exclusive occupancy of

Negro passengers, in compliance with the statute of North

Carolina requiring separate accom-odations for the races.

He then brought this action for damages. In holding that

the statute could not be applied to this case, the court said:

“ While there is learned and forcible decision to the con

trary (Smith v. State, 100 Tenn. 494, 46 S. W. 566), it seems

to be the trend of opinion and the decided intimation of the

Supreme Court of the United States, on the subject that

state legislation of this character may not extend to a case

of interstate traffic.”

And, in Hart v. State, supra, the appellant, a Negro, held

a ticket from New York to Washington entitling him to

transportation over a line extending from Pennsylvania

through Delaware and into Maryland. Upon his refusal to

take the seat assigned to him, he was indicted under the 1904

Maryland statute requiring separate coaches for white and

colored passengers. A plea in abatement was filed, where

upon the trial court sustained a demurrer to the plea and

appellant was thereupon convicted. Upon appeal, however,

the conviction was reversed. It was argued by the Attorney

General for the state that the statute was constitutional as

a police measure, although it affected interstate passengers,

to which contention the court replied that

“ Although the state has power to adopt reasonable police

regulations to secure the safety and comfort of passengers

[fol. 15] on interstate trains while within its borders, it is

well settled, as we have seen, that it can do nothing which

will directly burden or impede the interstate traffic of the

carrier, or impair the usefulness of its facilities for such

traffic. When the subject is national in its character and

admits and requires uniformity of regulation affecting alike

all the states, the power is in its nature exclusive, and the

state cannot act. The failure of Congress to act as to mat

ters of national character is, as a rule, equivalent to a dec

laration that they shall be free from regulation or restric

tion by any statutory enactment, and it is well settled that

interstate commerce is national in its character. Applying

these general rules to the particular facts in this case, and

bearing in mind the application of the expressions used in

16

Hall v. DeCuir to cases involving questions more or less

analogous to that before us, we are forced to the conclusion

that this statute cannot be sustained to the extent of making

interstate passengers amenable to its provisions. When a

passenger enters a car in New York under a contract with

a carrier to be carried through to the District of Columbia,

if when he reaches the Maryland line, he must leave that

car, and go into another, regardless of the weather, the

hour of the day or the night, or the condition of his health,

it certainly would, in many instances, be a great incon

venience and possible hardship. It might be that he was

the only person of his color on the train, and no other

would get on in the State of Maryland, but he, if the law is

valid against him, must, as soon as he reaches the state

line, leave the car he started in, and go into another, which

must be furnished for him, or subject himself to a criminal

punishment. ’ ’

and that, therefore, the statute could not be sustained under

the police power. The court added that it was convinced

that if the Supreme Court of the United States were called

to pass upon the precise question, it would hold such statute

invalid as applicable to interstate passengers.

In Anderson v. Louisville <& N. R. Co., supra, plaintiff and

his wife were forced, by the defendant, to occupy seats in

the Negro coach upon two separate trips. Upon the first,

they were traveling as first class passengers from Evans

ville, Indiana, to Madisonville, Kentucky, and were re

quired to move into said coach when the train reached Ken

tucky. On the second trip, the trip was wholly within

Kentucky. Suit was then brought against defendant

wherein the court considered the constitutionality of the

1892 Kentucky statute calling for separate but equal facili-

[fol. 16] ties for the races. It was held that the statute was

invalid as its language was broad enough to extend its ap

plication to interstate as well as intrastate passengers and

therefore constituted it a regulation of interstate commerce.

Defendant’s demurrer was accordingly overruled.

In Carrey v. Spencer, supra, plaintiff, a Negro, bought a

ticket for passage from New York to Knoxville, Tennessee.

At or near the Tennessee line he was moved into the coach

provided for Negro passengers pursuant to the provisions

of the Tennessee separate coach law. This suit was for

damages, being brought in a New York Court because de-

17

fendant company was in the hands of a receiver and the

court of receivership had granted plaintiff leave to sue in

New York. It was held that plaintiff was entitled to judg

ment, on the ground that the Tennessee statute, as applied

to an interstate passenger, was unconstitutional.

In Thompkins v. Missouri, K. & T. Ry. Co., supra, plain

tiff, a Negro, sued for damages arising from his ejection

from a Pullman car in Oklahoma, and for his arrest, con

viction and fine for disturbing the peace. He was a pas

senger from Kansas City, Missouri to McAlester, Okla

homa. The Oklahoma statute was in question, one of de

fendant’s positions being that it acted in conformity there

with. It was held that, as plaintiff was an interstate pas

senger, the statute was irrelevant.

In Brown v. Memphis <& C. R. Co., supra, plaintiff, a

Negro, sued for her exclusion from the ladies’ car on one

of defendant’s trains upon her refusal to take a seat in the

smoking car. There was at the time a statute of Tennessee

providing that all common law remedies for the exclusion

of any person from public means of transportation were

thereby abrogated, that no carrier should be bound to carry

any person whom he should for any reason choose not to

carry, that no right of action should exist in favor of any

person so refused admission, and that the right of carriers

as to the exclusion of persons from their means of transpor

tation should be as perfect as that of any private person.

Following Hall v. DeCuir, it was held that so far as this

statute purported to apply to interstate passengers, it was

unconstitutional, being a regulation of interstate commerce.

So long as uniform regulation remain a sine qua non of

the growth of the interstate carrier, the orderly conduct of

its business, and the protection of the national interest

therein, the recognition of a power in the states to deter

mine whether interstate traffic while within their boundaries

[fol. 17] shall be subject to a legislative policy of segrega

tion or non-segregation of the races is conducive only to a

result which the commerce clause was intended to forbid.

While such legislation purports merely to control the car

rier while within the territorial limits of the state, it neces

sarily influences its conduct in the management of its busi

ness throughout its entire route, since all passengers, inter

state as well as intrastate, are affected by the carrier’s dis-

2—704

18

position of its passengers pursuant thereto. Since each

state could legislate in its own interest without regard for

the consequences, and the various enactments could differ

in provision, a compliance with all would produce the kind

of confusion and embarrassment in the midst of which com

merce could not flourish. When it is perceived that the

recognition of the validity of a state law requiring the

segregation of the races would in turn necessitate the same

recognition of a non-segregation statute, there is no limit

to the carrier’s burden.

Such injurious consequences are already at hand. An ex

amination of the law of the six jurisdictions contiguous to

Virginia demonstrates the diversity of policy in our imme

diate section of the nation. Two such jurisdictions (West

Virginia and the District of Columbia) do not attempt to

segregate the races in either interstate or intrastate com

merce. Three others (Maryland, North Carolina and Ken

tucky) have, as appears from the second part of this argu

ment, construed their laws as limited in operation to intra

state traffic. Only one (Tennessee) has held its law appli

cable to the interstate passenger. Not a single state on the

Atlantic seaboard from Maine to Florida has decided that

its state policy in this regard can control any other than its

domestic commerce. Situated as it is in the path of a chan

nel of interstate transportation, Virginia should not provide

a stumbling block.

II

The Statute Upon Which This Prosecution Was Based

Should Be Construed As Limited in Its Operation to

Passengers in Intrastate Commerce, and Therefore As

Inapplicable to Defendant

If limited in operation to intrastate passengers, the stat

ute upon which this prosecution was based is valid, insofar

as the commerce clause of the Federal Constitution is con

cerned. Defendant’s position in this connection is that as

a matter of statutory construction rather than constitu-

[fol. 18] tional limitation, this statute did not apply to

her. Well established canons compel this conclusion.

The Applicable Rules of Construction

Where the validity of a statute is assailed and there are

two possible interpretations, by one of which the statute

19

would be unconstitutional and by the other it would be

valid, the Court should adopt the construction which will

uphold it and bring it into harmony with the Constitution,

if its language will permit.

Miller v. Commonwealth, 172 Va. 639, 2 S. E. 2d 343

(1939);

Hannabass v. Ryan, 164 Va. 519, 180 S. E. 416 (1935);

Commonwealth v. Carter, 126 Va. 469, 102 S. E 58

(1920);

Commonwealth v. Armour & Co., 118 Va. 242, 87 S E

610 (1916).

The duty of the court to so construe a statute as to save

its constitutionality when it is reasonably susceptible of two

constructions includes the duty of adopting a construction

that will not subject it to a succession of doubts as to its

constitutionality. It is well settled that a statute must be

construed, if fairly possible, so as to avoid not only the

conclusion that it is unconstitutional, but also serious doubt

upon that score.

National Labor Relations Board v. Jones & Laughlin

Steel Corp., 301 U. S. 1, 57 S. Ct. 615, 81 L. Ed. 893, 108

A. L .R . 1352 (1937);

Crowell v. Benson, 285 U. S. 22, 52 S. Ct. 285, 76 L. Ed

598 (1932);

South Utah Mines & Smelters v. Beaver County, 262

U. S. 325, 43 S. Ct. 577, 67 L. Ed. 1004 (1923);

Ann Arbor R. Co. v. United States, 281 U. S. 658, 50 S Ct

444, 74 L. Ed. 1098 (1930);

Be Keenan, 310 Mass. 166, 37 N. E. 2d 516, 137 A. L R

766 (1941).

In order to uphold the statute, the courts may restrict its

application to the legitimate field of legislation, unless the

act indicates a different intention on the part of its framers.

A statute should not be given a broad construction if its

validity can be saved by a narrower one.

South Utah Mines and Smelters v. Beaver County, supra;

[fol. 19] Schuylkill Trust Co. v. Pennsylvania, 302 U s!

508, 58 S. Ct. 295, 82 L. Ed. 392 (1938);

United States v. Walters, 263 U. S. 15, 44 S. Ct 10 68

L. Ed. 137 (1923);

20

Schoberg v. United States (C. C. A., 6th), 264 F. 1

(1920);

Mints v. Baldwin (D. C., N. Y.), 2 F. Supp. 700 (1933).

The Construction of Carrier Racial Segregation Laivs

In the vast majority of cases wherein there has arisen a

question as to the validity of a state carrier racial segrega

tion law upon the ground that it amounted to an unconstitu

tional interference with interstate commerce, the law has

been construed as limited in its operation to passengers in

intrastate commerce.

McCabe v. Atchison, T. & S. F. By. Co., 235 XL S. 151, 35

S. Ct. 69, 59 L. Ed. 169 (1914);

Chiles v. Chesapeake & 0. By. Co., 218 U. S. 71, 30 S. Ct.

667, 54 L. Ed. 936 (1910);

Chesapeake <& O. By. Co. v. Kentucky, 179 U. S. 388, 21

S. Ct. 101, 45 L. Ed. 244 (1900);

Louisville, N. O. <& T. By. Co. v. Mississippi, 133 U. S.

587, 10 S. Ct. 348, 33 L. Ed. 784 (1890);

Washington, B. & A. Elec. B. Co. v. Waller, 53 App.

D. C. 200, 289 F. 598, 30 A. L. R. 50 (1923);

South Covington & C. By. Co. v. Commonwealth, 181 Kv.

449, 205 S. W. 603 (1918);

McCabe v. Atchison, T. & S. F. By. Co. (C. C. A., 8th),

186 F. 966 (1911);

State v. Galveston, II. <& S. A. By. Co. (Tex. Civ. App.),

184 S. W. 227 (1916);

O’Leary v. Illinois Central B. Co., 110 Miss. 46, 69 S. 713

(1915);

State v. Jenkins, 124 Md. 376, 92 A. 773 (1914);

Chiles v. Chesapeake & O. By. Co., 125 Ivy. 299,101 S. W.

386 (1907);

Southern Kansas By. Co. v. State, 44 Tex. Civ. App. 218,

99 S. W. 166 (1906); “

Hart v. State, 100 Md. 596, 60 A. 457 (1905);

Ohio Valley B y.’s Beceiver v. Lander, 104 Ivy. 431, 47

S. W. 344 (1898);

Louisville, N. O. & T. By. Co. v. State, 66 Miss. 662, 6 S.

203 (1889);

State, ex rel., Abbott v. Hicks, 44 La. Ann. 770, 11 S. 74

(1892).

21

[fol. 20] Thus, in McCabe v. Atchison, T. & S. F. Ry. Co.,

supra, a case involving the 1907 Oklahoma law which re

quired separate coaches for the races, and providing penal

ties for its violation, five Negroes, citizens of Oklahoma,

brought suit in equity before the law went into effect against

five railroad companies to restrain its enforcement upon

the ground, inter alia, that it was repugnant to the com

merce clause. Of course, the highest court of Oklahoma

had not construed the act. There was a demurrer to the

bill which the trial court sustained. Upon appeal to the

Circuit Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit, the judg

ment below was affirmed upon the ground that the act, in

the absence of a different construction by the state court,

must be construed as applying to intrastate transportation

exclusively, and therefore as not contravening the com

merce clause. The Circuit Court of Appeals said on this

score:

“ The question, then, is whether that statute, when prop

erly construed, applies to interstate transportation, or

whether it is limited in its application to that transporta

tion which has its origin and ending within the confines

of the state. No provision is found in the act indicating

in any express terms that it was intended to apply to inter

state commerce. All its provisions concerning the subject

of legislation are general. Thus Section 1 provides that

‘ every railway company * * * doing business in this

state, * * * shall provide separate coaches,’ etc. Sec

tions 2 and 6 make it unlawful ‘ for any person’ to occupy

any waiting room or ride in any coach not designated for

the race to which he belongs. While, therefore, the lan

guage of the act, literally construed, is comprehensive

enough to include railroads doing interstate business, and

include passengers while making interstate trips, it neither

in express terms nor by any implication other than that

involved in the general language employed, manifests any

intention to invade the exclusive domain of congressional

legislation on the subject of interstate commerce. Local

transportation, or that which is wholly within the state

only, being within the competency of the state legislature,

would naturally be presumed to have been alone contem

plated in the law enacted by it. The constitutional inhibi

tion against a state legislating concerning interstate com-

22

merce, and the uniform decisions of courts of high and

controlling authority, emphasizing and enforcing that in

hibition, without doubt, were actually as well as construc

tively known to the members of the legislature of Okla

homa. It is unreasonable to suppose they intended to leg

islate upon a subject known by them to be beyond their

[fol. 21] power, and upon which an attempt to legislate

might imperil the validity of provisions well within their

power. Any other view would imply insubordination and

recklessness, which cannot be imputed to a sovereign state.”

Upon appeal to the Supreme Court of the United States,

the same conclusion was reached and the rule of interpreta

tion applied by the Circuit Court of Appeals confirmed.

Likewise, in Chesapeake & 0. By. Co. v. Kentucky, supra,

there was a review of the conviction of the railroad com

pany, an interstate carrier, under the 1892 statute which

provided that all railroads in the state must furnish sepa

rate but equal accommodations for the races. Defendant,

in the trial court, had contended that the statute was uncon

stitutional as a regulation of interstate commerce. Its

demurrer predicated upon this ground was overruled. The

Court of Appeals of Kentucky construed the act as apply

ing only to intrastate passengers, and affirmed the convic

tion, which the Supreme Court of the United States likewise

affirmed. Said the latter Court, through Mr. Justice

Brown:

“ Of course this law is operative only within the state.

* * * The real question is whether a proper construction of

the act confines its operation to passengers whose journeys

commence and end within the boundaries of the state or

whether a reasonable interpretation of the act requires

colored passengers to be assigned to separate coaches when

traveling from and to points in other states. * * *

“ This ruling (of the Court of Appeals of Kentucky) ef

fectually disposes of the argument that the act must be con

strued to regulate the travel or transportation on the rail

roads of all white and colored passengers, while they are in

the state without reference to where their journey com

mences and ends, and of the further contention that the

policy would not have been adopted if the act had been con-

23

fined to that portion of the journey which commenced and

ended within the state lines.

‘ ‘ Indeed, we are by no means satisfied that the Court of

Appeals did not give the correct construction to this statute

in limiting its operation to domestic commerce. It is

scarcely courteous to impute to a legislature the enactment

of a law which it knew to be unconstitutional, and if it were

well settled that a separate coach law was unconstitutional,

as applied to interstate commerce, the law applying on its

face to all passengers should be limited to such as the legisla

ture was competent to deal with. The Court of Appeals has

found this to be the intention of the General Assembly in

[fol. 22] this case, or as least, that if such were not its in

tention, the law may be supported as applying alone to

domestic commerce. In thus holding the act to he severable,

it is laying down a principle of construction from which

there is no appeal.”

There is ample room for this Court to avoid all constitu

tional difficulties with respect to the statute in question. It

is not in terms applicable to interstate passengers. It has

never been construed in this respect by this Court. It is not

necessary to impute a frustrated motive to the legislature

when settled principles require the limitation of its opera

tion in order to remove all doubt as to its validity.

Conclusion

Your petitioner submits that for the reasons set forth in

this her petition, which is hereby adopted as her opening

brief, the judgment of the trial court is erroneous, and

should be set aside, and prays that a writ of error may be

granted to said judgment, and a supersedeas thereto

awarded, and that the same may he reviewed and reversed.

Counsel for the petitioner hereby request that they be per

mitted to argue orally the matters contained in this petition

upon the application for a writ of error and supersedeas,

and certify that a copy hereof has been forwarded by regis

tered mail to the Honorable Lewis Jones, Commonwealth’s

Attorney for Middlesex County, Virginia, who was Com

monwealth’s Attorney when this case was tried and who

prosecuted the same on behalf of the Commonwealth. Said

copy was mailed on the 5th day of February, 1945. The

24

original hereof is filed in the office of the Clerk of this court

in Richmond, Virginia.

Irene Morgan, Petitioner, By Spottswood W. Robin

son, III, Of Counsel.

Hill, Martin & Robinson, Consolidated Bank Building,

Richmond 19, Virginia, Counsel for Petitioner.

[fol. 23] Certificate

I, Martin A. Martin, an attorney practicing in the Su

preme Court of Appeals of Virginia, do certify that in my

opinion the judgment complained of in the foregoing peti

tion is erroneous and should he reviewed.

Martin A. Martin, Consoliadted Bank Building,

Richmond 19, Virginia.

Received February 5, 1945.

M. B. Watts, Clerk.

March 6, 1945. Writ of error and supersedeas awarded

by the Court. Bond $100.

M. B. W.

I n Circuit Court of M iddlesex County

W arrant— Filed July 22, 1944

S tate of V irginia,

County of Middlesex, to-wit:

To any Sheriff or Police Officer:

Whereas R. P. Kelly has this day made complaint and

information on oath before me, G. C. Bourne, Justice of the

Peace of the said County, that Irene Morgan in said county

did on the 16th day of July, 1944: Unlawfully Refuse to

move back on the Greyhound Bus in the section for colored

people,

These are, therefore, to command you, in the name of the

Commonwealth, to apprehend and bring before the Trial

Justice of the said County, the body (bodies) of the above

accused, to answer the said complaint and to be further

dealt with according to law. And you are also directed to

25

[fol. 24] summon---------------color -------- Address ------ as

witnesses.

Given under my hand and seal, this 16th day of July, 1944.

G. C. Bourne, J. P. (Seal.)

R everse Side of Said W arrant :

Docket No. A 1450, Court No. 330 File 40

Commonwealth

v.

I rene M organ (c), Hayes Store, Va.

Warrant of Arrest

Executed this, the 16 day of July, 1944, by arresting

Irene Morgan.

R. B. Segar, Sheriff.

Upon the examination of the within charge, I find the

accused

July 18, 1944.

Upon a plea of not guilty to the within charge, and upon

examination of witnesses, I find the accused guilty as

charged and fix his punishment at a fine of $10.00 and —

days in jail and costs. Appeal noted. Bail set at $500.00.

Let to Bail.

Catesby G. Jones, Trial Justice.

Fine .................................. $10.00

Costs ................................. 5.25

Total ..................... $15.25

Filed July 22,1944.

C. W. Eastman, Clerk.

State of V irginia,

County of Middlesex, to-wit:

I, G. C. Bourne a justice of the peace in and for the

[fol. 25] County aforesaid, State of Virginia, do certify

that Mrs. Irene Morgan and Mrs. Ethel Amos, Sr., as her

surety, have this day each acknowledged themselves in-

26

debted to the Commonwealth of Virginia in the sum of

Five Hundred Dollars ($500.00), to be made and levied of

their respective goods and chattels, lands, and tenements

to the use of the Commonwealth to be rendered, yet upon

this condition: That the said Irene Morgan, shall appear

before the Trial Justice Court of Middlesex County, on the

18th day of July, 1944, at 10 A. M., at Saluda, Virginia,

and at any time or times to which the proceedings may be

continued or further heard, and before any court thereafter

having or holding any proceedings in connection with the

charge in this warrant, to answer for the offense with which

he is charged, and shall not depart thence without the

leave of said Court, the said obligation to remain in full

force and effect until the charge is finally disposed of or

until it is declared void by order of a competent court: and

upon the further condition that the sa id -------------- shall

keep the peace and be of good behavior for a period of

— days from the date hereof.

Given under my hand, this 16th day of July, 1944.

G. C. Bourne, J. P.

Costs— T. J. Court

Warrant ............................. $1.00

Trial ..................................... 2.00

Arrest ................................. 1.00

I n Circuit Court of M iddlesex County

[Title omitted]

Appeal from Trial Justice: Misdemeanor: Violation of

Section 4097dd of 1942 Code

[Title omitted]

[fol. 26] Appeal from Trial Justice: Misdemeanor: Resist

ing Arrest

Journal E ntry of H earing— September 25, 1944

This day came the Attorney for the Commonwealth and

the accused came to the bar with her counsel, and by con

sent of both parties these two cases are to be heard on the

evidence heard in both cases together and by consent of all

27

parties trial by jury was waived in both cases, and the

defendant agreed to submit her case to the Judge of this

Court for trial and disposition according to law, and mo

tion was made by the Attorney for the Commonwealth to

amend the warrant as follows: State of Virginia, County

of Middlesex, to-wit: To Any Sheriff or Police Officer:

Whereas E. P. Kelly, operator of the Greyhound Bus has

this day made complaint and information on oath before

me, G. C. Bourne, Justice of the Peace of the said County,

that Irene Morgan in the said County did on the 16 day of

July, 1944, Unlawfully refuse and fail to obey the direction

of the driver or operator of the Greyhound Bus Lines to

change her seat and to move to the rear of the bus and

occupy a seat provided for her, in violation of Section 5

of the Act, Michie Code of 1942, section 4097dd, which

motion was granted by the Court and to which ruling the

defendant excepted.

After the evidence for the Commonwealth was in, the

defendant moved to strike out all the evidence of the Com

monwealth and to dismiss the case wherein she was charged

of a violation of Section 4097dd of the Code, upon the

grounds that the defendant, Irene Morgan, was shown by

the evidence for the Commonwealth to be a passenger in

the interstate commerce upon an interstate public carrier,

towit, the Greyhound Bus, that she was a through passenger

from Hayes Store, Gloucester County, Virginia, to Balti

more, Maryland, that Section 4097dd of the Code of Vir

ginia could not constitutionally apply to interstate passen

gers and that its application to such passengers would vio

late Article I, Section 8 of the Constitution of the United

States, and that said Section 4097dd should, under settled

rules of construction, be construed as inapplicable in opera

tion to passengers in intrastate commerce; and also moved

to strike out all the evidence of the Commonwealth and to

dismiss the case wherein she was charged with resisting an

officer of the law in the discharge of his duty, upon the same

grounds previously advanced in support of her motion to

strike all the evidence of the Commonwealth and to dis

miss the case wherein she was charged with a violation of

Section 4097dd of the Code, and upon the additional

[fol. 27] grounds that the arrest of her person sought to

be made in this case was illegal, and that her conduct was

therefore within her privilege to resist an unlawful arrest.

28

These Motions the Court overruled, to which action of the

Court the defendant excepted.

After all the evidence for the Commonwealth and the

defendant respectively, was in, and both the Commonwealth

and the defendant had rested, defendant renewed her mo

tion to strike out all the evidence for the Commonwealth

in each of the cases aforesaid, upon the same grounds re

spectively, previously advanced in support of the motion

to strike made at the conclusion of the Commonwealth’s

case-in-chief, and upon the additional ground that the

conviction of the defendant in either case would constitute

a violation of her rights under the Fourteenth Amendment

to the Constitution of the United States. These motions

the Court overruled, to which action of the Court the de

fendant excepted.

And the Judge of this Court reserves his decision in each

case until October 18th, 1944.

I n Circuit Court of M iddlesex County

[Title omitted]

J udgment— October 18, 1944

This day came the Attorney for the Commonwealth and

the accused, Irene Morgan came to the bar with her counsels,

Spottswood Bobinson, III, and Linwood Smith, and the

Court having maturely considered of its judgment in this

case doth find the defendant Guilty: Thereupon the defend

ant moved the Court to set aside its findings of facts and

grant the defendant a new trial upon the grounds that the

said findings of fact were contrary to the law and the evi

dence and assigned in support of said motion the following

reasons:

(1) That the law upon which the prosecution was based

could not be constitutionally applied to the defendant, an

interstate passenger, and that its application to a passen

ger in interstate commerce was a violation of Article I,

Section 8, of the Constitution of the United States;

[fol. 28] (2) That under settled rules of construction

said law could not be construed to apply to a passenger in

29

interstate commerce, and that it must be construed as lim

ited in its application to intrastate passengers:

(3) That the conviction of the defendant would, under

the circumstances of this case, constitute a violation of her

rights under the Fourteenth Amendment of the Constitution

of the United States; and that (4) said findings of facts

were contrary to the evidence, and lacking in evidence suffi

cient to support them. This motion the Court overruled,

to which action of the Court the defendant excepted.

Defendant moved the Court to grant her a new trial,

upon the ground that her conviction was erroneous under

the law and contrary to the evidence, and assigned as rea

sons in support of this motion the same reasons previously

advanced in support of the motion to set aside the findings

of fact and to grant the defendant a new trial. This motion

the Court overruled, to which action of the Court the de

fendant excepted.

Defendant moved the Court to arrest the judgment in

this case upon the ground of errors of law and fact appar

ent upon the face of the record in the case, and assigned

as reasons in support of this motion the same reasons

previously advanced in support of the motion to set aside

the findings of fact and to grant the defendant a new trial.

This motion the Court overruled, to which action of the

Court the defendant excepted.

The Court having found the said Irene Morgan guilty

as charged in said warrant doth sentence the said Irene

Morgan to pay a fine to the use of the Commonwealth of

Ten Dollars and the costs in this behalf expended.

Whereupon, the defendant indicated to the Court her

intention of applying to the Supreme Court of Appeals of

Virginia for a writ of error to the judgment of the Court

in this case, and moved the Court to grant a suspension

of the execution of the judgment entered in this case. There

upon, the Court granted said motion and granted a sus

pension of the execution of the judgment for a period of

sixty days from date within which period counsel for the

defendant might present to the Court bills of exception

in said case, and granted to defendant leave to apply to

the Court for additional time within which to present to,

and have acted upon by, the Supreme Court of Appeals of

Virginia, a petition for writ of error to the judgment in

this case.

30

[fol. 29] I n Circuit Court of M iddlesex County

[Title omitted]

Order S uspending E xecution of J udgment— Filed Decem

ber 7, 1944

This day came the defendent by her counsel and moved

the Judge rendering the judgment in this case to further

suspend the execution of the judgment and sentence here

tofore rendered and imposed in this case on the 18th day

of October, 1944, in order to permit the defendant to present

a petition for a writ of error to said judgment to the Su

preme Court of Appeals of Virginia, and to have the same

acted upon by said Court.

Whereupon, it appearing that the defendant has applied

to said Judge, who is the Judge of this Court, for the

signing and sealing of her several Bills of Exception, the

same having been this day signed, sealed, enrolled and

saved to her, and made a part of the record in this case,

within sixty days of the final judgment in this case, and

that the defendant desires and intends to present to the

Supreme Court of Appeals of Virginia a petition for a writ

of error to the judgment herein. It is hereby adjudged

and ordered that execution of the said judgment and sen

tence be and the same is hereby suspended until the 17tli

day of February, 1945, and thereafter until such petition

is acted upon by the Supreme Court of Appeals of Vir

ginia if such petition is actually filed on or before the 17th

day of February, 1945. ______

I n the Circuit Court of M iddlesex County

Case 330

Commonwealth of V irginia

v.

I rene M organ

Appeal from Trial Justice, Violation of Section 4097dd of

1942 Code

[fol. 30] B ill of E xception N o. 1— Filed December 7, 1944

Be it remembered that on the trial of this case the fol

lowing evidence on behalf of the Commonwealth and of the

defendant, respectively, as hereinafter denoted, is all of

the evidence that was introduced:

Witnesseth for the Commonwealth.

R. P. Kelly.

Direct examination:

R. P. Kelly testified that he lives in Norfolk, Virginia;

that he is an employee of the Greyhound Lines, and has

been employed by said company for the last six years;

that on the 16tli day of July, 1944, he was engaged in his

duties and was driving, and was in charge and control of,

a Greyhound bus from Norfolk, Virginia, to Baltimore,

Maryland; that Irene Morgan, the defendant, was a pas

senger on, his bus on July 16, 1944; that the defendant is

a colored person; that she boarded the bus at Hayes Store,

in Gloucester County, Virginia; that when she boarded the

bus at Hayes Store the bus was crowded; that all seats

were occupied and both white and colored passengers were

standing in the aisle; that after the arrival of the bus in

Saluda, at about 11 A. M. on that day, and the discharge

of the white and colored passengers destined there, there

were six white passengers standing, but no colored pas

sengers standing; that at this time he perceived the defend

ant and another colored woman, the latter carrying an

infant, seated in the second seat forward of the long seat

in the extreme rear of the bus, the seat in which they were

so seated being, in a view toward the rear of the bus, on

the left side of the aisle; that at this time he also saw two

vacant seats on the long rear seat, which long rear seat

was partly occupied by colored passengers; that he re

quested the defendant and her seatmate to move back into

the two vacant seats on the long rear seat; that the defend

ant’s seatmate started to change her seat, but the defend

ant pulled her back down into the seat; that the defendant

refused to change her seat as requested; that he, the wit

ness, thereupon explained to her the bus rules and regula

tions as to seating colored and white passengers on busses,

and informed her that he was required to seat white pas-

[fol. 31] sengers from the front of the bus backward and

colored passengers from the rear of the bus forward.

At this point the witness produced a booklet in evidence

which he identified as the Manual of Rules for Bus Opera-

31

32

tors of the Greyhound Lines, and testified that said Manual

contained, on pages 34 and 35 thereof, a rule of said com

pany. Thereupon, the Commonwealth introduced into evi