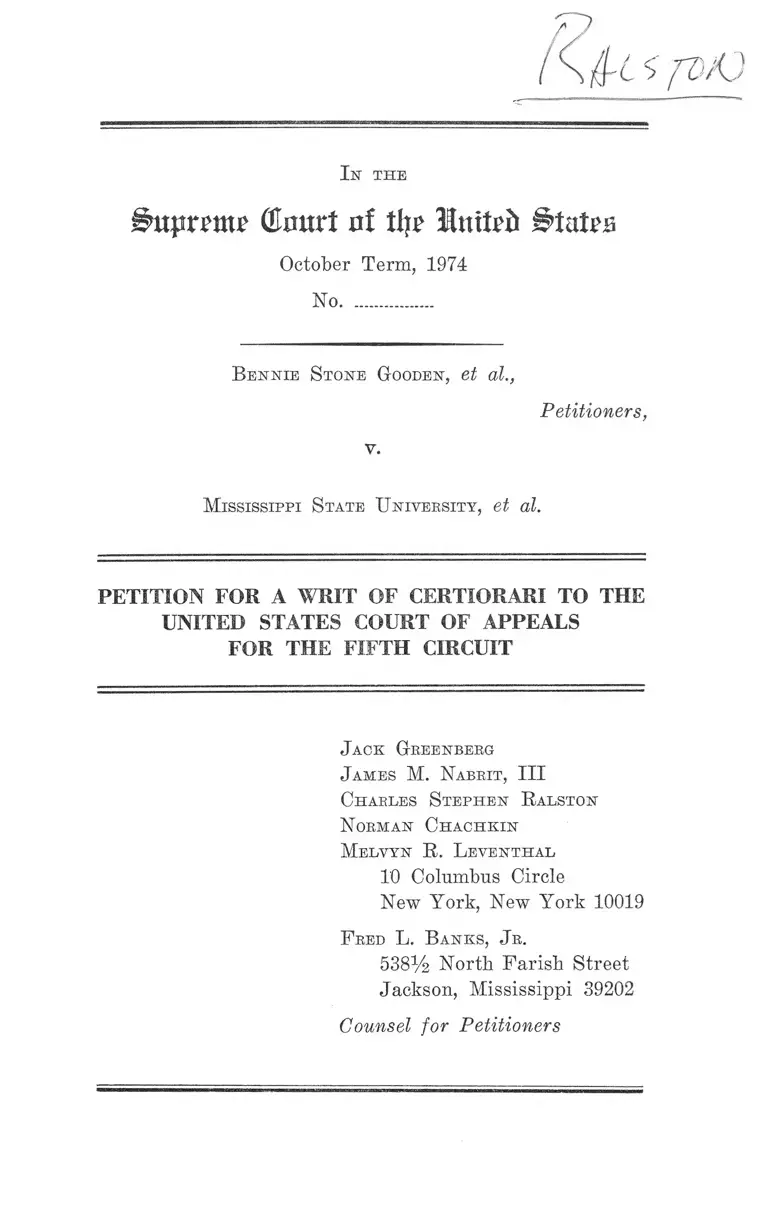

Gooden v. Mississippi State University Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1974

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Gooden v. Mississippi State University Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit, 1974. 144996ad-b39a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/81080d4a-a290-41f2-92be-befd230c5aca/gooden-v-mississippi-state-university-petition-for-a-writ-of-certiorari-to-the-united-states-court-of-appeals-for-the-fifth-circuit. Accessed March 13, 2026.

Copied!

I n t h e

Bnpxmx GImtrt nf % luttrd §>tatxa

October Term, 1974

No................

B e n n ie S to n e G ooden, et al.,

Petitioners,

v.

M is s is s ip p i S tate U n iv er sity , et al.

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

J ack G reenberg

J am es M. N abrit , III

C h a r les S t e p h e n R alston

N orman C h a c h k in

M elv y n R . L ev e n t h a l

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

F red L. B a n k s , J r.

538% North Farish Street

Jackson, Mississippi 39202

Counsel for Petitioners

I N D E X

Opinions Below ................................. 1

Jurisdiction .................................................................... 2

Questions Presented ..................................................... 2

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved ...... 2

Statement of the Case ................................................. 3

Reasons for Granting the Writ—

I. Summary .............................................................. 7

II. Mootness .............................................................. 9

III. Attorneys’ Pees ..................................................... 15

CONCLUSION ....... 18

A ppe n d ix —•

Complaint .............................................................. la

Motion for Preliminary Injunction or in the Al

ternative for a Temporary Restraining Order .... 6a

Certificate of Service ............................................ 7a

Answer ......... 8a

Exhibit “A” Annexed to Answer.................... 11a

Notice of Motion ...... 12a

District Court Findings — Excerpts from Tran

script ....................................................................... 13a

PAGE

11

Letter to District Court ......................................... 19a

Order ............ 20a

Appeals Court Opinion ..................................... 22a

Judgment ............ 28a

Denial of Petition for Rehearing En Banc.......... 29a

T able of A u t h o b it ie s

Cases:

Alexander v. Holmes County Board of Education, 396

TT.S. 19 (1969) ................................................. ......... 7

Anderson v. Canton Municipal Separate School Dis

trict, 5th Cir., No. 28030, Aug. 1973 ........................ 12

Barron v. Bellairs, 496 F.2d 1187 (5th Cir. 1974)...... 9

Bishop v. Starkville Academy, N.D. Miss. Civil Ac

tion No. 7497-K ........................................ ................ 13

Blackwell v. Anguilla Line Consolidated School Dis

trict, 5th Cir. No. 28030, Nov. 24, 1969 ..................... 12

Bradley v. School Board of Richmond, 40 L.Ed. 2d

476 (1974) ............... .............................. 6,8,14,15,16,17

Coffey v. State Educational Finance Commission, 296

F. Supp. 1389 (S.D. Miss. 1969) ............................ 12

Coffey v. State Educational Finance Commission,

C.A. No. 2906, Sept. 2, 1970 (unreported).............. 12

Cook v. Hudson, 365 F. Supp. 855 (N.D. Miss. 1973) 12

Cypress v. Newport News General & Nonsectarian

Hospital, 375 F.2d 648, 658 (4th Cir. 1967)............ 13

DeFunis v. Odegaard, 40 L.Ed.2d 164 (1974)............. 8,10

DeSimone v. Linford, 494 F.2d 1186 (5th Cir. 1974).... 9

PAGE

I l l

Driver v. Tunica County School District, 323 F. Supp.

1019 (N.D. Miss. 1970) ............................................ 12

Gilmore v. City of Montgomery, 473 F.2d 832 (5th

Cir. 1973) (Alabama) ......................................... 13

Gilmore v. City of Montgomery, 41 L.Ed.2d 304, 321

(1974) .........................................................................8,13

Graham v. Evangeline Parish School Board, 484 F.2d

649 (5th Cir. 1973) (Louisiana) ............................. 13

Green v. Connally, 330 F.Supp. 1150 (D.D.C. 1970).... 12

Hollon v. Mathis Independent School District, 491

F.2d 92 (5th Cir. 1974) .......................................... 9

Lankford v. Gelston, 364 F.2d 197, 203 (4th Cir. 1966)..5,13

McNeal v. Tate County School District, 460 F.2d 568

(5th Cir. 1972) ........................................................ 12

Merkey v. Board of Regents, 493 F.2d 790 (5th Cir.

1974) .......................................................................... 9

Miller v. Amusement Enterprises, Inc., 426 F.2d 534

(5th Cir. 1970) ..................................... 16

National Lawyers Guild v. Board of Regents, 490 F.2d

97 (5th Cir. 1974) ............................. 9

Newman v. Piggy Park Enterprises, 390 U.S. 400

(1968) ....................... 15,16

Northcross v. Board of Education, 412 U.S. 427

(1973) ....................................................................................................................................... . . . 6, 8,15,17

Norwood v. Harrison, 413 II.S. 455 (1973)..........3, 7,12,13

Roe v. Wade, 410 U.S. 113, 124-25 ............................... 10

Super Tire Engineering Co. v. McCorkle, 40 L,Ed.2d

1 (1974) ..................................................................... 8,10

PAGE

PAGE

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education,

402 U.S. 1, 15 (1971) ................................................

Taylor v. Coahoma County School District, 345 F.

Supp. 891 (N.D. Miss., 1972) .......................... ..... .

United States v. Mississippi, 499 F.2d 425 (5th Cir.

1974) ...........................................................................

United States v. Phosphate Export Association, 393

U.S. 199 (1968) ................................................... 8,10,

United States Servicemen’s Fund v. Killen Indepen

dent School District, 489 F.2d 693 (5th Cir. 1974)....

United States v. W. T. Grant & Co., — U.S. 629

(1953) ................................................................... 8,10,

Wright v. Baker County Board of Education, 501 F.2d

131 (5th Cir. 1974) (Georgia) ...............................

Constitution and Statutes:

20 U.S.C. §1605(d)(l)(A) ...........................................

20 U.S.C. §1617 ....................... .................... 2, 6, 7, 8,15,

28 U.S.C. §1254(1) ......................................................

42 U.S.C. §1983 ............................................................

Miss. Code, 1942 §7931 ................... ............................

Miss. Code, 1972, §37-23-61 (as amended, 1974) .......

Miss. Code, 1972, §47-5-91 ...........................................

Other Authorities:

Cong. Ree. S. 5485 (daily ed. April 22, 1971), 117

Cong. Rec. 5490-91 ...................................................

15

12

13

11

9

14

13

13

16

2

4

13

13

13

16

I n t h e

Supreme (Emirt of % Mutko States

October Term, 1974

No................

B e n n ie S tone G ooden, et al.,

Petitioners,

v.

M is s is s ip p i S tate U n iv er sity , et al.

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

Petitioners, Bennie Stone Gooden, et al., respectfully

pray that a Writ of Certiorari issue to review the opinion

and judgment of the United States Court of Appeals for

the Fifth Circuit entered in this proceeding on August 19,

1974.

Opinions Below

The opinion of the Court of Appeals is reported at 499

F.2d 441 (5th Cir. 1974) and is reprinted in the Appendix

hereto, pp. 22a-27a. The district court did not enter an

opinion, but its findings and order, not reported, are re

printed in the Appendix hereto, pp. 13a-18a, 20a-21a.

2

Jurisdiction

The judgment of the Court of Appeals was entered on

August 19, 1974 (p. 28a); a petition for rehearing or in the

alternative for rehearing en banc was denied on October

16, 1974 (p. 30a). Jurisdiction of this Court is invoked

pursuant to 28 U.S.C. §1254(1).

Questions Presented

I.

Whether the Court of Appeals erred in directing the dis

missal of this action as moot and in reversing a district

court determination that injunctive relief was necessary

to prevent state defendants from providing material aid to

Mississippi’s private segregationist academies.

II.

Whether the Court of Appeals erred in holding that the

alleged cessation of unlawful activity subsequent to service

upon defendants of the Complaint and Motion for Pre

liminary Injunction foreclosed an award of attorneys’ fee

under 20 U.S.C. §1617.

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved

This case involves the Equal Protection Clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment and 20 U.S.C.A. §1617 (Volume

20, page 463) which provides as follows:

§1617 Attorneys Fees

Upon the entry of a final order by a court of the United

States against a local educational agency, a State (or

any agency thereof), or the United States (or any

3

agency thereof), for failure to comply with any pro

vision of this chapter or for discrimination on the basis

of race, color, or national origin in violation of Title

VI of the Civil Eights Act of 1964, or the fourteenth

amendment to the Constitution of the United States as

they pertain to elementary and secondary education,

the court, in its discretion, upon a finding that the pro

ceedings were necessary to bring about compliance,

may allow the prevailing party, other than the United

States, a reasonable attorney’s fee as part of the costs,

(emphasis added)

Statement of the Case

Plaintiffs are black children in attendance at Clarksdale,

Mississippi public schools which, upon desegregation, lost

the majority of its white students, enrolled in grades 7-12,

to the Lee Academy, Clarksdale’s segregationist private

secondary school. All Mississippi private segregationist

secondary schools with athletic programs, including the

Lee Academy, are members of the Academy Athletic Con

ference (also known as the “Academy Activities Commis

sion of the Mississippi Private School Association).” 1

The Complaint herein charged that defendants, the Board

of Trustees of Institutions of Higher Learning, Mississippi

State University, and the President thereof, had granted

the segregationist Academy Athletic Conference permis

sion to use the State University’s gymnasium and related

facilities for the conduct of its annual championship and

all-star basketball games scheduled for the week of Feb

1 These facts were established through the record of Norwood

v. Harrison, 413 TJ.S. 455 (1973), of which the district court took

judicial notice (pp. 14a-15a). The non-discriminatory counterpart

to the Academy Athletic Conference is the Mississippi High School

Activities Commission: all public and non-discriminatory private

schools are members of that organization.

4

ruary 21 and March, 1972, in violation of the Equal Pro

tection Clause and 42 U.S.C. §1983, A preliminary injunc

tion, to prevent the specified use, a permanent injunction

against the underlying policy authorizing such uses, costs

and attorneys’ fees were sought (pp. la-6a).

Friday, February 11, 1972, plaintiffs hand delivered to

the Attorney General of Mississippi, and mailed to each

of the defendants, a copy of the Complaint and the Mo

tion for Preliminary Injunction or in the Alternative

Motion for Temporary Restraining Order which had that

day been posted to the Clerk of the District Court

for filing (p. 7a). After receiving those documents, the

Attorney General’s representative contacted Mississippi

State University and/or officials of the Academy Athletic

Conference and arranged for the Athletic Conference to

withdraw its request to use the state owned facilities (pp.

9a, 11a, 15a).

On the following Monday—February 14, 1972—the

Academy Athletic Conference addressed a letter to the

President of Mississippi State University, with carbon

copy to the Assistant Attorney General assigned to this

case. The letter stated that the segregationist athletic con

ference “wishes to withdraw any and all of its requests to

hold functions at Mississippi State University as of this

date, February 14, 1972. We especially wish to withdraw

the request for hosting the Academies’ . . . championship

basketball games to be held the weekend of the 24-25-26 of

February, 1972” (p. lla). The cancellation of the February

games at Mississippi State made unnecessary further pro

ceedings on plaintiffs’ motion for preliminary injunctive

relief and no hearing was held thereon.

March 13, 1973, defendants filed a “Notice of Motion,”

through which they renewed the motion to dismiss con

tained in their Answer, alleging that the controversy was

5

moot as a result of the Academy Conference’s February 14,

1972, letter (p. 12a).

March 22, 1973, the case was called for hearing before

the District Court (pp. 13a-18a). Defendants declined to

offer any proof of mootness and rested on the allegations

contained in their Answer and the February 14, 1972,

letter. During the hearing the Court, from the bench, made

the following findings:

(a) The constitutional violation had been established by

the pleadings: defendants’ Answer admitted that defen

dants had plenary authority over Mississippi State Uni

versity and other public institutions of higher learning and

that they had authorized the segregationist academies to

conduct their basketball all-star and championship games

using the gymnasium and supporting facilities of Missis

sippi State University. Accordingly, the burden of proving

“mootness” was assigned to defendants (pp. 9a, 16a-18a).

(b) Defendants’ policy of permitting private segrega

tionist academies use of public facilities was still in effect:

the Academy Conference (not a party to the action) had

withdrawn its request to use the facilities; but defendants

did not withdraw and have never withdrawn permission to

use facilities2 (p. 16a). In addition, it was clear from the

pleadings that the cessation of unlawful activity “was

timed to blunt the force of a lawsuit,” Lankford v. Gelston,

364 F.2d 197, 203 (4th Cir. 1966), having occurred only

after the Complaint and Motion for Preliminary Injunction

or Temporary Restraining Order had been delivered to

counsel opposite and mailed to the clerk of the Court for

filing (pp. 6a-7a, 11a).

2 The District Court asked counsel for defendants to provide

some assurance that the Board of Trustees would adopt a new

policy meeting constitutional standards; the Assistant Attorney

General could not provide such assurance (pp. 15a-17a).

6

(c) State officials are urged repeatedly to provide as

sistance to Mississippi’s private segregationist academies;

an injunction could be used by defendants as a shield to

resist such demands:

It would give . . . [defendants] something on which

they could stand if requests are made in the future by

racially discriminatory school groups . . . We all know

that when these requests come . . . from racially dis

criminatory schools that they are difficult to turn down.

The Court is not naive. The only way they could be

turned down effectively and feasibly [by the Board of

Trustees or Mississippi State] would be to have some

thing on the books that says . . . [public facilities] can

not be used (pp. 16a-17a).

The District Court concluded that it “could not say that

merely because there has been a withdrawal of the request

. . . that there is no reasonable expectation that the wrong

will be repeated” (p. 18a). The injunction was issued, but

plaintiffs’ request for attorneys’ fees was denied without

opinion or discussion (pp. 20a-21a).3 Defendants appealed

from the entry of the injunction and plaintiffs cross-ap

pealed from the denial of attorneys’ fees.

August 19,1974, the Court of Appeals entered its opinion

directing the district court to vacate the injunction and to

dismiss the action as moot, and affirming the denial of at

3 At the conclusion of March 22, 1973 hearing, plaintiffs’ counsel

requested an award of attorneys’ fees which request was denied by

the Court without explanation. Plaintiffs renewed their request

and cited 20 U.S.C. §1617 by letter to the district court dated

March 29, 1973 (p. 18a). Again, the District Court summarily

denied the request through its order of April 4, 1973 (pp. 19a).

However, the district court did not have the benefit of Northeross

v. Board of Educ., 412 U.S. 427 (1973), decided two months after

the order denying fees was entered; nor could it anticipate Bradley

v. School Board of Richmond, 40 L.Ed. 2d 476 (1974).

7

torneys’ fees4 (pp. 22a-27a). It reasoned that plaintiffs

had the burden of proving that the case was not moot; i.e.,

that plaintiffs were required to establish that permission

to use Mississippi State had been granted prior to, or dur

ing the one year following, the unlawful act specified in

the Complaint (p. 27a). The Court held that the case had

been rendered moot by the Academy Conference’s decision

to withdraw its request for Mississippi State facilities

(p. 27a). It also determined that the cancellation of the

basketball games at Mississippi State, subsequent to de

livery of the pleadings to counsel for defendants, fore

closed an award of attorneys’ fees under 20 IT.S.C. §1617,

reasoning that “no finding that these proceedings were

necessary to bring about compliance with statutory or

constitutional rights was made or could be supported by

this record” (p. 27a).

Reasons for Granting the Writ

I.

Summary

The Court of Appeals has decided an important question

of federal law having widespread impact in a way in con

flict with applicable decisions of this Court. Dismissal of

this action as moot frustrates the District Court’s efforts

to establish and maintain only unitary public school sys

tems in the State of Mississippi.5 Judge Keady, the Dis

trict Judge, “has lived with this . . . [problem] for so many

years and . . . has a much better appreciation both of the

4 Plaintiff school children were also taxed with costs (p. 28a).

6 See Alexander v. Holmes County Board of Education, 396

U.S. 19 (1969) ; Norwood v. Harrison, 413 U.S. 455 (1973).

8

extent to which these . . . matters are actually problems in

the . . . [State of Mississippi], and of the need for injunc

tive relief to resolve . . . [them] to the extent they exist.”

Gilmore v. City of Montgomery, 41 L.Ed.2d 304, 321 (1974)

(Mr. Justice Marshall, concurring in part and dissenting

in part). The decision below provides defendant state

officials with an incentive to engage in “resist and with

draw” tactics, i.e., to materially assist private segregation

ist academies unless and until lawsuits are filed challenging

separately each of their activities, and it imposes upon the

private bar the duty to enforce the Constitution, acting as

watchmen on a day-to-day basis to prevent the recurrence

of unlawful acts.

The decision below also confuses the doctrine of “moot

ness” arising in the context of a change in the status of the

parties, with the issue of “mootness” arising in the context

of the cessation of unlawful activity or the alleged elimina

tion of a controversy’s subject matter and, in this additional

respect, departs from controlling decisions of this Court.

Compare, e.g., DeFunis v. Odegaard, 40 L.Ed.2d 164 (1974);

Super Tire Engineering Co. v. McCorJcle, 40 L.Ed.2d 1

(1974), with, e.g., United States v. W. T. Grant & Co., 345

U.S. 629 (1953); United States v. Phosphate Export As

sociation, 393 U.S. 199 (1968).

Finally, the Court of Appeals’ sua sponte finding that

this litigation was not “necessary to bring about compliance

with . . . constitutional rights,” and its decision to deny

counsel fees to plaintiffs’ attorneys, is in conflict with

Congress’ intent in enacting 20 U.S.C. §1617 as definitively

interpreted by the Court in Bradley v. School Board of

Richmond, 40 L.Ed.2d 476 (1974), and Northcross v. Board

of Education, 412 U.S. 427 (1973).

In the face of a clear uncontroverted violation of plain

tiffs’ constitutional rights, the Court of Appeals has freed

9

defendants from injunctive relief and permitted them to

avoid any attorneys’ fee liability; the holding even re

sults in costs being taxed against plaintiff black children

and parents (p. 29a). And in this manner the “resist and

withdraw” tactic is established as an effective strategy

for undermining constitutional rights.

II.

Mootness

The Court of Appeals, in finding this case moot, relies

upon precedent holding that an intervening change in cir

cumstances (generally, a change in plaintiffs’ status re

vealing the absence of “standing”), compels a finding that

either plaintiffs no longer suffer any injury from the

policy or practice under challenge or that the Court, for

practical reasons, is not able to remedy the wrong.6 The

6 The eases cited by the Court of Appeals illustrate the point:

Barron v. Bellairs, 496 F.2d 1187 (5th Cir. 1974) (new legislation

removing plaintiff class from purview of the statute under chal

lenge, rendered controversy, as to plaintiffs, m oot); National

Lawyers Guild v. Board of Regents, 490 F.2d 97 (5th Cir. 1974)

(suit to enjoin university to permit a specific meeting of plaintiff

group, rendered moot when time for meeting had passed) ; Merkey

v. Board of Regents, 493 F.2d 790 (5th Cir. 1974) (suit to enjoin

recognition of college club rendered moot after plaintiff student

left the school) ; DeSimone v. Linford, 494 F.2d 1186 (5th Cir.

1974) (effort to obtain preliminary injunction ordering reinstate

ment pending final determination of administrative appeal, ren

dered moot by the completion of the administrative appeal) ;

United States Servicemen’s Fund v. Killen Independent School

District, 489 F.2d 693 (5th Cir. 1974) (suit challenging school-

district’s refusal to permit school auditorium to be used for anti

war theatrical production, rendered moot by the cessation of the

Vietnam War and indication that plaintiffs no longer desired

facilities) ; Eollon v. Mathis Independent School District, 491

F.2d 92 (5th Cir. 1974) (plaintiffs’ graduation rendered moot a

challenge to school regulation).

10

doctrine has recently been applied in DeFunis v. Odegaard,

40 L.Ed.2d 164, 169 (1974), wherein plaintiff was assured

the result he sought through his lawsuit—graduation from

the University of Washington Law School—and a “determi

nation . . . of the legal issues . . . [was] no longer necessary

to compel that result and could not serve to prevent it.” 7

However, the Court has distinguished the issue of mootness

as it arises in DeFunis from the issue as it arises when

defendants claim that the lawsuit’s subject matter has been

eliminated by their “voluntary cessation of allegedly il

legal conduct.” United States v. W.T. Grant & Go., 345

U.S. 629, 632 (1953).8 Generally, the DeFunis issue arises

through an event affecting plaintiffs while the W.T. Grant

issue arises through activity initiated by defendants.

The Court of Appeals’ failure to distinguish between

these two separate and distinct lines of cases is at the

foundation of its error: the case at bar does not involve

any claim that petitioners, black children attending Mis

sissippi public schools, no longer have an interest in, or can

suffer any injury from, defendants’ policy of assisting the

State’s segregationist academies; rather, the only issue

raised is whether the Academy Conference’s decision to

cancel its 1972 games at Mississippi State offered sufficient

7 See also: Super Tire Engineering Co. v. McCorkle, 40 L.Ed.

2d 1, 8 (1974) (employers who brought suit challenging a state

welfare program for striking workers continued to “retain suffi

cient interest” in lawsuit’s subject matter—the state statute and

program—after its striking employees returned to work) ; Roe V.

Wade, 410 U.S. 113, 124-25 (1973) (plaintiff pregnant women

challenging abortion statutes continued to retain sufficient interest

in the statutes after the termination of their pregnancies).

8 See, for example, United States v. Phosphate Export Ass’n,

393 U.S. 199, 202 (1968), wherein defendant association claimed

it had ceased to exist and that, the allegedly illegal sales could

not again take place, i.e., that the lawsuit's subject matter—the

illegal sales—had been eliminated and the case rendered moot.

11

assurance that unlawful practices would not recur, result

ing in the elimination of the action’s subject matter.

The District Court, but not the Court of Appeals, tested

defendants’ claim, of mootness, based upon the alleged

cessation of unlawful activity, by the proper standard re

cently summarized by the Court:

The test for mootness . . . is a stringent one. Mere

voluntary cessation of allegedly illegal conduct does

not moot a case; if it did, the courts would be compelled

to leave ‘the defendants . . . free to return to his old

ways.’ . . . A case might become moot if subsequent

events made it absolutely clear that the allegedly

wrongful behavior could not reasonably be expected

to recur. . . . [There is] a heavy burden of persuasion

which we have held rests upon . . . [defendants].

[There must be proof] that the likelihood of further

violations is sufficiently remote to make injunctive re

lief unnecessary.

United States v. Phosphate Export Ass’n, 393 TI.S.

199, 203 (1968) (emphasis added).

The District Court determined that defendants had not

met their “heavy burden of persuasion.” It found of para

mount importance the absence of any change in defendants’

policy toward the use of public facilities by segregationist

schools: the Academy Conference, not a party to the action,

had withdrawn its request to use Mississippi State Uni

versity but defendants continued to authorise such illegal

use (pp. 15a-18a).

The trial court also recognized that state officials are

torn between two school systems, one public and integrated,

a second, private, segregated and owing its existence to the

desegregation of public schools. Judge Keady, drawing

12

upon his own judicial experience, knew that the potential

for recurring violations was great since the academies

could be expected to continue their practice of pressuring

public officials for support (pp. 17a-18a). He viewed the

practices under challenge as but a continuation of the long

history of Mississippi support for segregationist acad

emies: Coffey v. State Educational Finance Commission,

296 F. Supp. 1389 (S.D. Miss. 1969) (tuition grants in

validated) ; Coffey v. State Educational Finance Commis

sion, C.A. No. 2906, September 2, 1970 (unreported) (tui

tion loan program invalidated); Green v. Connally, 330

F. Supp. 1150 (D.D.C. 1970) (tax exemptions invalidated);

Norwood v. Harrison, 413 U.S. 455 (1973) (text book aid

invalidated); Driver v. Tunica County School District,

323 F. Supp. 1019 (N.D. Miss. 1970) (salaries paid to

academy teachers invalidated); Cook v. Hudson, 365 F.

Supp. 855 (N.D. Miss. 1973) (public school district regula

tion prohibiting employment of professionals who enroll

their own children in segregationist academies upheld);

McNeal v. Tate County School District, 460 F.2d 568 (5th

Cir. 1972) (transfer of school building to segregationist

academy subjected it to restrictions); Taylor v. Coahoma

County School District, 345 F. Supp. 891 (N.D. Miss.,

1972) (transfer of school property to segregationist acad

emies enjoined); Anderson v. Canton Municipal Separate

School District, 5th Cir., No. 28030, August, 1973, (un

reported) (injunction issued to enjoin transfer of school

buildings or property to Canton Academy followed by

Motion for Contempt Judgment and then Consent Order

directing school officials to assure the return to public

schools of stadium bleachers and flood lights removed to

Canton Academy); Blackwell v. Anguilla Line Consoli

dated School District, 5th Cir., No. 28030, Nov. 24, 1969

(unreported) (“No abandoned school facility under this

plan, if any, shall be used for private school purposes”) ;

13

United States v. Mississippi, 499 F.2d 425 (5th Cir. 1974)

(lease of public school building to private segregationist

academy voided).9

The “resist and withdraw” tactic used by defendants and

the Academy Athletic Conference has been uniformly re

jected, until now, as a basis for finding mootness since

changes “timed to anticipate or blunt the force of a law

suit offer insufficient assurance” that the practice at issue

will not be repeated. Lankford v. Gelston, 364 F.2d 197,

203 (4th Cir. 1966); Cypress v. Newport News General &

Nonsectarian Hospital, 375 F.2d 648, 658 (4th Cir. 1967).

The decision below can serve only to encourage state de

fendants and the Academy Conference to violate constitu

tional rights until plaintiff class musters the resources

necessary for cases such as these.10 The tactic promises to

9 At least one case is still pending in Mississippi: Bishop v.

Starkville Academy, N.D. Miss. Civil Action No. 7497-K, (chal

lenges Miss. Code, 1972, §37-23-61, as amended 1974, to the extent

that it authorizes annual tuition grants of $600. to educationally

disadvantaged or gifted children enrolled in private segregationist

schools). Other forms of state assistance to Mississippi segrega

tionist academies persist. See, for example, Miss. Code, 1972,

§47-5-91 (1964 and 1969 enactments), authorizing tuition and

transportation payments for state penetentiary employees’ children

in segregationist academies; statute modified original 1942 enact

ment (Miss. Code, 1942 §7931), providing for transportation and

tuition payments for education of penitentiary employees’ chil

dren in neighboring public school district.

The problem has taxed black students’ resources in other states

as well: Wright v. Baker County Board of Education, 501 F.2d

131 (5th Cir. 1974) (Georgia) ; Graham v. Evangeline Parish

School Board, 484 F.2d 649 (5th Cir. 1973) (Louisiana) ; Gilmore

v. City of Montgomery, 473 F.2d 832 (5th Cir. 1973) (Alabama).

Two such cases have been resolved in this Court: Norwood v.

Harrison, supra and Gilmore v. City of Montgomery, 41 L.Ed.2d

304 (1974).

I t has also been the subject of congressional concern and legisla

tion, 20 U.S.C. §1605(d) (1) (A).

10 “ [T] his sort of case is an enterprise on which any private

individual should shudder to embark. . . . To secure counsel will

ing to undertake the job of trial . . . necessarily means that some-

u

be most effective in undermining efforts to monitor and

eliminate state support for segregationist academies since

black students and their parents are not privy to segrega

tionist school meetings or policy decisions and cannot

anticipate requests for and grants of public assistance from

or to such schools. Indeed, the Academy Conference used

Mississippi State University for its 1970-71 games, with

out challenge, because petitioners first learned of these

events through newspaper accounts the day after they oc

curred. When the elimination of state support for racially

discriminatory schools—a matter of high national priority

—is so readily frustrated, injunctive relief to prevent re

peated violations is necessary.

These considerations, found compelling by the district

court, were given no weight on appeal despite the limited

scope of review authorized in these cases. An appellate

court can only reverse a district court’s determination on

the issue of mootness upon finding that “no reasonable

basis” supports the lower court’s decision: “[t]he Chan

cellor’s decision is based upon all the circumstances; his

discretion is necessarily broad and a strong showing of

abuse must be made to reverse it.” 11 United States v.

one—plaintiff or lawyer—must make a great sacrifice unless equity

intervenes.” Bradley v. School Board of Richmond, 40 L.Ed.2d

476, 492, n. 25 (quoting the district court).

11 The Court of Appeals also implies that the burden is upon

the plaintiffs to prove that recurring violations will occur. It

determined, from a silent record, that “no proof was made that

permission of this sort had ever previously been given” (p. 26a).

Since the burden of proving mootness under W. T. Grant, supra,

is assigned to defendants, the court should have found that there

was no proof that permission had ever been denied. Defendants

declined to offer any proof of mootness (p. 14a), and plaintiffs

consequently offered no proof of previous violations. [As we note

in the text, the Academy Conference used Mississippi State during

the 1970-71 school term, or a full year before the lawsuit was filed.

This fact, although not in the record, was brought to the attention

of the Court of Appeals at oral argument and in the petition for

rehearing].

15

W. T. Grant & Co., 345 U.S. 629, 633-34 (1953). This stan

dard is particularly appropriate in cases challenging state

support for racially segregated education. Swann v.

Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education, 402 U.S. 1, 15

(1971). The District Court was either clearly correct or it

was not clearly incorrect in finding the potential for recur

ring violations, and the Court of Appeals abused its dis

cretion and misperceived controlling precedent in vacating

the injunction.

III.

Attorneys’ Fees

The District Court summarily denied attorneys’ fees

without the benefit of this Court’s decisions in Northcross,

supra, and Bradley, supra, construing 20 U.S.C. §1617.

The Court of Appeals should have remanded the case to

the District Court for reconsideration in light of these

intervening decisions; instead, it sua sponte foreclosed an

award of attorneys’ fees.

In Northcross v. Board of Education, 412 U.S. 427, 428

(1973), the Court held that “plaintiffs in school cases are

‘private attorneys general’ vindicating national policy in

the same sense as are plaintiffs in Title II cases.” Ac

cordingly, it was held that since attorneys’ fees must be

awarded routinely to prevailing plaintiffs in Title II cases,

“unless special circumstances would render such an award

unjust,” [Newman v. Piggy Park Enterprises, 390 U.S. 400,

(1968)] so must they be awarded under 20 U.S.C. §1617

in cases charging racial discrimination in education. More

over, the statutes’ objective of encouraging individuals to

vindicate Congressional policy against racial discrimina

tion, has led the court to reject as evidence of “special

circumstances” a variety of factors including the absence

16

of frivolous defenses, good faith, or that some members of

the court agreed with defendants, or that plaintiffs were

not obligated to pay any fees. Newman v. Piggie Park

Enterprises, 390 TJ.S. 400 (1968); Miller v. Amusement

Enterprises, Inc., 426 F.2d 534 (5th Cir. 1970). Similarly,

in deciding that under 20 U.S.C. §1617, counsel fees should

be awarded for services performed prior to the effective

date of that Act, the Court considered the importance of

encouraging individuals to vindicate national policy against

racial discrimination in education. Bradley v. School

Board of Richmond, 40 L.Ed.2d 476, 491-93, and n. 27

(1974). Read together, the cases establish the principle

that limitations upon fee awards to prevailing plaintiffs,

acting as “private attorneys general,” are disfavored and

20 TJ.S.C. §1617’s requirement that a fee award is to be

made “upon finding that the proceedings were necessary

to bring about compliance,” must be construed in that

light.

Equally important, much of the debate in the Senate

leading to the passage of 20 U.S.C. §1617, centered on the

language of the statute cited by the Court of Appeals to

deny counsel fees. It is clear that the prerequisite for a

fee award, a “finding that the proceedings were necessary

to bring about compliance,” was intended to protect against

two abuses: the champertous filing of lawsuits to obtain a

fee and the unnecessary protraction of litigation to trial

and judgment when defendants have made a bona fide and

adequate offer of settlement. See Cong. Rec. S. 5485 (daily

ed. April 22, 1971), (colloquy between Senators Javits

and Cook), 117 Cong. Rec. 5490-91. Thus the statute would

bar or limit an attorneys’ fee herein if defendants had been

willing to enter into a consent order on the merits and to

an award of attorneys’ fees for services rendered through

the filing of the Complaint, but plaintiffs had insisted upon

trial on the merits. However, defendants declined to pur

17

sue that course and have insisted instead that injunctive

relief is to be resisted at all costs.

It is uncontroverted that the pleadings were hand de

livered to counsel for defendants three days before the

Academy Conference withdrew its request to use Missis

sippi State University (p. 7a). This fact, when viewed in

the light of this Court’s decisions in Northcross and Bradley

and the legislative history, compels a presumption that, in

this case, “proceedings were necessary to bring about com

pliance,” with plaintiffs’ constitutional rights under the

Fourteenth Amendment; the appeals court decision fore

closing such a finding is simply untenable.

Defendants must be assigned the burden of proving that

the proceedings were champertous or marked by bona fide

offers of settlement rejected by plaintiffs. The case should

be remanded to the district court for reconsideration of the

attorneys’ fee issue in light of that standard compelled by

Bradley, Northcross and the legislative history as dis

cussed above.

18

CONCLUSION

For these reasons a Writ of Certiorari should issue to

review the judgment and opinion of the United States

Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit.

Respectfully submitted,

J ack G reenberg

J am es M . N abrit , I I I

N orm an C h a c h k in

C h a rles S t e p h e n R alston

M elv y n R . L ev e n t h a l

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

F red L . B a n k s , J r .

538% North Farish Street

Jackson, Mississippi 39202

Counsel for Petitioners

APPENDIX

Complaint

(Filed February 14, 1972)

I n t h e U n ited S tates D istrict C ourt

F or t h e N o rth ern D istrict oe .Mis s is s ip p i

E astern D iv isio n

C iv il A ction N o. EC72-12K

B e n n ie S tone G ooden , J r ., by bis father, Bennie Stone

Gooden, Sr.; J o h n W esley L ong and L a w ren ce L ong,

by tbeir mother, Mrs. Herbie Cannon Long,

vs.

Plaintiffs,

M is s is s ip p i S tate U n iv e r s it y ; Dr. W illia m L . G il e s , Pres

ident o f Mississippi State University; T h e B oard of

T ru stees oe I n st it u t io n s of H ig h er L ea r n in g ,

Defendants.

1. Jurisdiction of this Court is invoked pursuant to

28 U.S.C. §1343(3) and (4). This is a suit in Equity

authorized by 42 U.S.C. §1983, which seeks to redress the

deprivation of rights assured and protected by the Four

teenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United States.

2. Plaintiffs seek a preliminary and permanent injunc

tion enjoining defendants from affording The Academy

Athletic Conference of Mississippi, and its member schools,

the use of athletic and other facilities at Mississippi State

University and other state owned institutions of higher

learning.

la

2a

II

3. Plaintiffs Bennie Stone Gooden, Jr., John Wesley

Long and Lawrence Long are black citizens of the United

States residing in Clarksdale, Mississippi. They are stu

dents in attendance at the public schools of the Clarksdale

Municipal Separate School District. Their right to a ra

cially integrated and otherwise non-discriminatory public

school system, and their right to the elimination of all

state support for racially segregated schools, have been

frustrated and/or abridged by the creation of the racially

segregated Lee Academy of Clarksdale, Mississippi, the

formation of The Academy Athletic Conference of Missis

sippi, and the policies and practices of defendants as set

forth below. The named plaintiffs are minors and are repre

sented by their parents, Bennie Stone Gooden, Sr. and Mrs.

Herbie Cannon Long.

4. The named plaintiffs bring this action as a class ac

tion pursuant to Rule 23 of the Federal Rules of Civil

Procedure. They sue in their own behalf and in behalf of

students throughout the state of Mississippi who are ag

grieved by the policies and practices of defendants com

plained of herein. The members of the class on whose behalf

plaintiffs sue are so numerous so as to make it impractica

ble to bring them all individually before the Court, but

there are common questions of law and fact involved and

common grievances arising out of common wrongs. A com

mon relief is sought for plaintiffs and all members of the

class. The plaintiffs fairly and adequately represent the

interests of the class. The policies and practices of defen

dants complained of herein are applicable to the plaintiff

class generally. Moreover, the questions of law and fact

common to the members of the class predominate over any

Complaint

3a

question affecting only individual members and a class

action is superior to other available methods for adjudica

tion of the controversy.

5. Defendant Mississippi State University is an institu

tion of higher learning owned, supported and operated by

the State of Mississippi. Defendant William L. Giles, is

the President, the chief executive officer and administrator,

of Mississippi State University. Defendant, The Board of

Trustees of Institutions of Higher Learning governs, and

has plenary authority and control over, all state owned in

stitutions of higher learning in the state of Mississippi.

I l l

6. a) Beginning with the 1964-65 school year—when the

first public school districts in Mississippi were required to

integrate under freedom of choice—and through the pres

ent, numerous private racially segregated schools and

academies have been either formed or enlarged, which

schools have established as their objective and/or have had

the effect of affording white children of the state of Mis

sissippi racially segregated elementary and secondary

schools as an alternative to racially integrated and other

wise nondiscriminatory public schools.

b) These private racially segregated schools have formed

and are members of The Academy Athletic Conference

which Conference sponsors and conducts athletic programs

and events for the racially segregated private schools of

the State.

7. Defendant Mississippi State University has granted

The Academy Athletic Conference permission to use the

Complaint

4a

University’s gymnasium and campus facilities for the pur

pose of holding an overall conference championship in

basketball; these playoff games are scheduled to be held

during the week of February 21-26, 1972.

8. Defendant Mississippi State University has granted

The Academy Athletic Conference permission to use the

University’s gymnasium and campus facilities for the pur

pose of holding Academy Conference all-star games in

basketball; these all-star games are scheduled to be held

during the second week of March, 1972.

9. Defendants, in permitting The Academy Athletic Con

ference the use of state owned gymnasiums and facilities,

have provided state aid and encouragement to racially seg

regated education and have thereby impeded the achieve

ment of racially integrated public schools in violation of

plaintiffs’ rights assured and protected by the Fourteenth

Amendment to the Constitution of the United States.

W h e r e fo r e , plaintiffs respectfully pray that this Court;

1. Enter a preliminary injunction enjoining defendants

to deny The Academy Athletic Conference and its member

schools the use of Mississippi State University’s gymnasium

and facilities for the conduct of basketball playoffs, tourna

ments and all-star games, scheduled for February and

March, 1972.

2. Enter a permanent injunction enjoining defendants

to deny The Academy Athletic Conference and its members

schools the use of all facilities subject to the control of the

Board of Trustees of Institutions of Higher Learning.

Complaint

5a

3. Grant plaintiffs their costs herein including reason

able attorney’s fees.

4. Grant such additional or alternative relief as the

Court deems just and equitable.

February 11, 1972

Complaint

Respectfully submitted,

M elvyn R. L ev e n t h a l

A nderson , B a n k s , N ic h o ls

& L ev e n t h a l

538% North Farish Street

Jackson, Mississippi 39202

F r a n k R. P arker

233 North Farish Street

Jackson, Mississippi 39202

J ack G reenberg

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Counsel for Plaintiffs

6a

Motion for Preliminary Injunction or in the

Alternative for a Temporary Restraining Order

(Title Omitted)

Plaintiffs respectfully move this Court to enter an order

preliminarily enjoining Mississippi State University, its

President, Dr. William L. Giles and the Board of Trustees

of Institutions of Higher Learning from affording The

Academy Athletic Conference of Mississippi and/or its

member schools the use of Mississippi State University’s

gymnasium and other facilities for the conduct of Academy

Athletic Conference basketball play-offs, tournaments and

all-star games or other programs pending full hearing on

plaintiffs’ Complaint and Motion for Permanent Injunction.

Unless the Court grants the relief prayed for herein

plaintiffs will be irreparably injured: The Academy

Athletic Conference has scheduled basketball play-offs at

Mississippi State University beginning February 21, 1972.

February 11, 1972

Respectfully submitted,

M elvyn R. L e v e n t h a l

A nderson , B a n k s , N ich o ls

& L ev e n t h a l

538% North Farish Street

Jackson, Mississippi 39202

F r a n k R. P arker

233 North Farish Street

Jackson, Mississippi 39202

J ack Greenberg

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Counsel for Plaintiffs

7a

Certificate of Service

I hereby certify that on this 11th day of February, 1972,

I caused to be served by personal delivery upon Honorable

William Allain, Assistant Attorney General, State of Mis

sissippi, New Capitol Building, Jackson, Mississippi and

by United States mail, postage prepaid, upon Dr. William

L. Giles, President, Mississippi State University, Stark-

ville, Mississippi and Mr. W. 0. Stone, President, Board

of Trustees, Institutions of Higher Learning, Post Office

Box 1491, Jackson, Mississippi, copies of a Complaint,

Motion For Preliminary Injunction Or In The Alternative

For A Temporary Restraining Order and Notice of Motion.

M elvyst R. L e v ek th a l

8a

Answer

(Title Omitted)

Come now the Defendants, Mississippi State University,

Dr. William L. Giles, President, Mississippi State Uni

versity, and the Board of Directors of the State Institutions

of Higher Learning, and answer the Complaint filed herein

as follows:

F irst D e f e n s e

This Court lacks jurisdiction of any of the defendants or

the subject matter in this cause.

S econd D e fe n se

The Complaint fails to state a claim against the defen

dants upon which relief can be granted.

T h ir d D e fe n se

The Complaint filed herein fails to satisfy the prerequi

site to a class action pursuant to Rule 23 of Federal Rules

of Civil Procedure.

F o u r th D e f e n s e

1. Defendants deny that this court has jurisdiction un

der any of the constitutional amendments or statutes set

out in Paragraph 1 of the Complaint.

2. Defendants deny the allegations contained in Para

graph 2 of the Complaint.

9a

Answer

3. Defendants lack information sufficient to form a belief

as to the truth of the averments of the first, second and last

sentences of Paragraph 3 of the Complaint and deny the

remaining portion of Paragraph 3.

4. Defendants deny the allegations contained in Para

graph 4 of the Complaint.

5. Defendants admit the allegations of Paragraph 5 of

the Complaint.

6. Defendants deny the allegations contained in Para

graph 6 of the Complaint, including subparagraphs a and b

therein.

7. Defendants admit the allegations of Paragraph 7 of

the Complaint, but would further state that upon initiation

of said Academy Activities Commission of the Mississippi

Private School Association, the acceptance and/or permis

sion of said commission to use the facilities of Mississippi

State University was withdrawn effective February 14,

1972. (Ex. “A”)

8. Defendants admit the allegations contained in Para

graph 8 of the Complaint, but would further state that the

Academy Activities Commission of the Mississippi Private

School Association has withdrawn its request to hold its

championship games in the facilities at Mississippi State

University on February 24, 25, and 26, 1972. (Ex. “A”)

9. Defendants deny the allegations contained in Para

graph 9 of the Complaint.

10a

Answer

W h e r e fo r e , Defendants deny that p la in t i f f s are entitled

to any relief in this action and pray that the action he dis

missed at plaintiffs’ cost.

Respectfully submitted,

A. F. S u m m e r , Attorney General

of the State of Mississippi

W illia m A. A l l a in , First Assistant

Attorney General of Mississippi

E d D avis N oble, J r ., Special Assistant

Attorney General of Mississippi

By: E d D avis N oble, J r .

11a

Exhibit “A” Annexed to Answer

February 14, 1972

Dr. W. L. Giles, President

Mississippi State University

State College, Mississippi

Dear Dr. Giles:

The Academy Activities Commission of the Mississippi

Private School Association wishes to withdraw any and all

of its requests to hold functions at Mississippi State Uni

versity as of this date, February 14,1972.

We especially wish to withdraw the request for hosting the

Academy Activities Commission’s championship basketball

games to be held the weekend of the 24-25-26th of February,

1972.

With very best regards, I am

Sincerely yours,

/ s / Gleitk A. Caih

Glenn A. Cain

Executive Secretary

GAC :lkt

cc: Mr. Charles Shira, Athletic Director,

Miss. State University

Mr. Ed. Nobles, State Attorney General’s Office

12a

Notice of Motion

[M otion to D is m is s ]

Please take notice that the undersigned will bring the

attached Motion to Dismiss [Answer, pp. 8a-lla] or in the

alternative Summary Judgment which is contained in De

fendants’ answer pursuant to Rule 12 (b), F.R.C.P., on for

hearing before this Court at the United States Courthouse

in the City of Greenville, State of Mississippi, on Thurs

day, the 22nd day of March, 1973, at 1 :30 P.M. or as soon

thereafter as counsel may be heard.

A.F. S u m m e r

Attorney General of

the State of Mississippi

B y: E d D avis N oble , J r.

13a

Note: The following are all of the district court’s findings

entered during the March 22, 1972 hearing and relating to

the issue of mootness.

No. EC-72-12-K

The following proceedings were had in the United States

District Court, Northern District of Mississippi, on

March 22, 1973, before the Honorable William C. Keady,

Chief Judge, at Greenville, Mississippi.

A ppe a r a n c e s :

For the Plaintiffs:

The Honorable Melvyn Leventhal

For the Defendants:

The Honorable Ed Davis Noble, Jr.

The Court: The Court will call EC-72-12, Bennie Stone

Gooden, Jr., and others versus Mississippi State University

and others, defendants, pursuant to notice of the Court

to set this matter down at this time for final hearing or

other disposition that may be appropriate.

Are the plaintiffs ready!

Mr. Leventhal: Yes, your Honor.

The Court: Are the defendants ready!

Mr. Noble: Yes, Your Honor.

The Court: All right, Mr. Leventhal—

Mr. Noble: May it please the Court, preliminarily, I

believe we noticed that we would bring forward—

The Court: A motion to dismiss!

District Court Findings— Excerpts from Transcript

14a

Mr. Noble: —a motion to dismiss and in the alternative

summary judgment, Your Honor.

The Court: All right. Do you wish to present that?

Mr. Noble: Your Honor—

The Court: Let’s see first for the record whether there

is any evidence to be taken. Do you have any evidence in

connection with your motion or otherwise?

Mr. Noble: No, sir. The only thing we have, Your

Honor, of course, is the memorandum with the attached

exhibit. [Letter from Academy Conference, February 14,

1972, attached to Answer]

The Court: Well, the exhibit . . . will be considered as

offered in evidence. [It is] . . . attached to the memoran

dum?

Mr. Noble: Yes, sir, that was mailed to you.

The Court: Let’s get [it] . . . and mark . . . [it].

The Clerk: That will be Exhibit One for the Defendant.

Mr. Leventhal: I ’m familiar with it, Your Honor.

The Court: All right.

Now, before proceeding further, Mr. Leventhal, for the

record, do you have any evidence to present at this time?

Mr. Leventhal: No, Your Honor.

The Court: All right.

Mr. Leventhal: However, we would ask the Court to

take judicial notice of the record presented to this Court

in Norwood v. Harrison and we ask the Court to take

judicial notice of the fact that we have a private academy

string in the state and secondly establish by Norwood v.

Harrison that all senior academies conducting junior or

senior high athletic programs are members of the con

ference and sought and obtained permission to use Missis

sippi State University facilities.

The Court: All right.

District Court Findings

15a

Does the state have any objection to the Court taking

such judicial notice?

Mr. Noble: We would object, Your Honor, of course, to

the extent that since we consider the case moot that it is

unnecessary for the Court to take judicial notice at this

time of the existence of the private schools or of any

academy athletic conference.

The Court: Well, the Court does take judicial notice

of that because, of information contained in its own records.

What it may be worth for the purpose of the present hear

ing is another question.

You may proceed with your motion to dismiss . . . .

# # *

The Court: Was this matter ever brought before the

board of trustees and did they adopt a resolution as a

matter of policy?

Mr. Noble: No, Your Honor, it was never brought before

the board because it was not necessary, for the simple

reason that as soon as the Complaint was tiled it was

brought to my attention and as a. result I personally

represented to Mississippi State that at that time the—

The Court: But this suit has been pending against the

board for over a year. They have not adopted any official

policy regarding the use of public facilities ?

Mr. Noble: No, sir, as far as I know, they haven’t. As

far as my office is concerned, Your Honor, we are only

subject to call by the board. We might add that taking the

Complaint at face value, Your Honor, there is only repre

sentation there as to Mississippi State, one, that the plain

tiffs themselves are only students at the Coahoma County

public school system and that any sort of support that

District Court Findings

16a

would have accrued that might injure these plaintiffs would

come to Lee Academy. That is the only locale that would

injure these particular plaintiffs. Mr. Leventhal, I would

assume, in his drawing the Complaint, did not represent

or has not offered any other particular evidence to show

that there is any damage as related to any activity held at

the University of Mississippi, Mississippi State College for

Women or any other representation to any of the other

institutions. . . .

# * #

The Court: Well, it would be easy enough to settle it if

the board of trustees would adopt a resolution declaring

the policy. That would be easy enough. They have had a

year. And if they will do it, I am willing to give them

another opportunity and hold up. But it is the fact they

have not adopted a policy. And as Mr. Leventhal points

out, the only reason this matter was not brought into the

Court was the decision of one not a defendant to withdraw

his request. There was no request by the college officials.

Mr. Noble: The request was made by the Academy

Athletic Conference.

The Court: And permission was granted. But permis

sion was not withdrawn. Had permission been withdrawn

by the state university people—

Mr. Noble: Your Honor, if I may, I would like to state

to you that I attempted to reach Hr. Giles and get the

letter of transmittal back that the request was accepted

and permission therefor withdrawn.

The Court: I understand. Your clients have been sued

in federal court and extraordinary injunctive relief asked.

Now, you have had over a year, you might say, to prepare

your record for defense. There has been no record made

District Court Findings

17a

that would put this case on ice, so to speak, as far as you

are concerned. Now, very clearly had the board of trustees

adopted a resolution saying that they would not permit

the exclusive use of any of the state university and college

facilities by private, racially discriminatory academies, I

would regard it as moot, even though they have fixed terms

and are subject to going out of office in the future. I think

that is getting into speculation. But they have not as of

now taken any position. I do not, know what their view is.

They may think there is nothing wrong . . . .

# * #

The Court: But that is what is bothering the Court.

There has been no declaration of policy that would inform

this Federal Court that there is no need to issue.

Mr. Noble: Your Honor, again the representation of

Mr. Leventhal was that these children in Coahoma County

—have they been injured? Have they been injured in

Clarksdale? Has there been any benefit derived from it at

all to Lee Academy which is represented in the Complaint?

Has there? Mr. Leventhal has not presented any statistics

that one white child has withdrawn from the black schools

over there because of it.

The Court: [I]f I thought holding the case open for 30

days would cause the board of trustees to adopt a resolu

tion satisfactory to this Court, I would do so. But there is

no indication that would be forthcoming. It has not been

forthcoming. And I think that with the law being settled as

it is the injunction would possibly be a useful thing not

only to members of the plaintiff class but also to the board

and to college administrators. It would give them some

thing on which they could stand if requests are made in the

District Court Findings

18a

future by racially discriminatory school groups. So I can

not say that merely because there has been a withdrawal

of the request by one or the other defendant that there is

no reasonable expectation that the wrong will not be

repeated. We all know that when these requests come

from—if they do come from racially discriminatory schools

that they are difficult to turn down. The Court is not naive.

The only way they could be turned down effectively and

feasibly would be to have something on the books that says

they cannot be used.

So I am going to grant the permanent injunction on the

basis of this jacket file and the statement made by counsel

today.

District Court Findings

19a

March 29, 1973

Honorable William C. Keady

United States District Judge

Post Office Box 190

Greenville, Mississippi 38701

Be: Bennie Stone Gooden, et al.

v. Mississippi State

University, et al.,

Civil Action No. EC72-12(K)

Letter to District Court

Dear Judge Keady:

In accordance with your instructions, I enclose a proposed

order. I have attempted to set forth the standard adopted

by the Fifth Circuit in Gilmore v. City of Montgomery. . . .

3. In accordance with your instructions, I have included a

paragraph denying plaintiffs an award of attorney’s fees.

However, I enclose a copy of a recent Fifth Circuit opinion

{Johnson v. Combs, 471 F.2d 84 (5th Cir. 1972)), which

makes an award of such fees mandatory in a case such as

this.

I respectfully ask the Court to reconsider its denial of a

fee in light of Combs.

Sincerely,

Melvyn R. Leventhal

MRL :msc

Enclosures

cc: Ed Davis Noble, Jr., Esquire

20a

Order

(Title Omitted)

This cause having been heard on March 22, 1973, on

plaintiffs’ motion for a permanent injunction, and the court

having considered memorandum briefs, and the contents

of the jacket file and having taken judicial notice of certain

facts recorded in the court reporter’s notes of these pro

ceedings; it is

Ordered

(1) Defendant, Board of Trustees of Institutions of

Higher Learning, is permanently enjoined from allowing

or permitting gymnasiums, athletic fields, and other school

facilities of all colleges and universities subject to its

control or jurisdiction to be used for the holding of con

tests, activities and programs sponsored by Academy

Athletic Conference (also known as Academy Activities

Commission of the Mississippi Private School Associa

tion), or its member schools, or any other private school

which does not enroll black students; provided, however,

that this shall not preclude any student, or group of stu

dents attending any private school from access to such

facilities under defendants’ control when such facilities

are open to the general public on a nonexclusive, com

munal basis. Gilmore v. City of Montgomery, Fifth Circuit

Court of Appeals No. 72-1610, Slip Opinion February 9,

1973.

(2) The defendant, Board of Trustees of Institutions of

Higher Learning, shall notify the president, chancellor or

executive head of each college or university subject to its

jurisdiction of the requirements of this order.

(3) Plaintiffs’ motion for an award of attorney’s fees is

hereby denied.

21a

Order

The clerk of this court is directed to serve a copy of this

order by certified mail upon Dr. E. E. Thrash, Executive

Secretary and Director of the Board of Trustees of Insti

tutions of Higher Learning, Jackson, Mississippi.

This, 4th day of April, 1973.

W illia m C. K eady

Chief Judge

United States District Court

22a

Appeals Court Opinion

Gooden, et al. v. Mississippi State University, et al.,

5th Cir. No. 73-2108

E n tered A ug u st 19, 1974

Appeals from the United States District for the Northern

District of Mississippi.

B e f o r e :

B e l l , D yeb a n d Cla rk ,

Circuit Judges.

P er C ubiam :

Plaintiffs, three black students attending public school

in Clarksdale, Mississippi, sued on behalf of a class com

prised of “students throughout the State of Mississippi

who are aggrieved by the policies and practices of the

defendants complained of herein.” The complaint, filed

February 14, 1972, alleged that “numerous private racially

segregated schools and academies,” as members of the

Academy Athletic Conference, had been granted permission

by Mississippi State University to use the University’s

gymnasium and facilities to hold basketball games on Feb

ruary 21-26, 1972. It was further asserted that this action

provided state aid and encouragement to such member

schools and thereby impeded the achievement of racially

integrated public schools. Preliminary injunctive relief

was sought to stop Mississippi State from allowing the

tournament, and permanent injunctive relief was requested

denying the Academy Athletic Conference the use of all

facilities controlled by the Board of Trustees of Institu

tions of Higher Learning, which oversees the eight public

four-year collegiate institutions in the state. The defen

23a

dants were the president of Mississippi State University

and the Trustees of the Institutions of Higher Learning.

They answered admitting that permission had been given

for the use of Mississippi State’s facilities on February

21-26, but alleged that on the same day the complaint had

been filed the Academy Athletic Conference withdrew its

request, and the games had not been played on state

property. A hearing consisting solely of statements and

arguments of counsel, was held in February of the follow

ing year. The district judge made no findings of fact but

issued this injunction on April 4,1973:

Defendant, Board of Trustees of Institutions of Higher

Learning, is permanently enjoined from allowing or

permitting gymnasiums, athletic fields, and other

school facilities of all colleges and universities subject

to its control or jurisdiction to be used for the holding

of contests, activities and programs sponsored by

Academy Athletic Conference (also known as Academy

Activities Commission of the Mississippi Private

School Association), or its member schools, or any

other private school which does not enroll black stu

dents; provided, however, that this shall not preclude

any student, or group of students attending any private

school from access to such facilities under defendants’

control when such facilities are open to the general

public on a nonexclusive, communal basis. Gilmore v.

City of Montgomery, [473 F.2d 832 (CA 5, 1973) 1973],

Both parties appeal. Defendants seek to vacate the in

junction. Plaintiffs protest the court’s failure to award

them attorneys’ fees. Defendants protest the issuance of

the injunction as an imprudent exercise of the court’s

equitable power because (1) none of the circumstances

Appeals Court Opinion

24a

present in Gilmore was shown to be present in this ease,

(2) no threat of similar requests or approvals in the future

was shown, and (3) at the time of issuance the cause was

moot. Plaintiffs contend that the court’s action must be

judged in light of its knowledge of the existence of a wide

spread network of private schools that pose a threat to the

success of public school integration—knowledge which was

gained from taking judicial notice of its own records in

Norwood v. Harrison, 413 U.S. 455, 93 S.Ct. 2804, 37

L.Ed.2d 723 (1973). They reason from this that it was

permissible for the court to conclude that the Board of

Trustees of Institutions of Higher Learning had an affir

mative duty to adopt a negative policy forbidding use of

all facilities under their supervision in the manner en

joined. Plaintiffs’ cross-appeal claims that Section 718 of

Title VTI, 20 U.S.C. § 1617,1 applies and, coupled with the

decisions in Newman v. Piggie Park Enterprises, 390 IT.S.

400, 88 S.Ct. 964, 19 L.Ed.2d 1263 (1968) and Johnson v.

Combs, 471 F.2d 84 (5th Cir. 1972), mandates the award

of attorneys’ fees in this case.

Because the Supreme Court granted certiorari in Gil

more, supra, 414 U.S. 907, 94 S.Ct. 215, 38 L.Ed.2d 145

(1973), and Bradley v. Richmond School Board, 412 U.S.

937, 93 S.Ct. 2773, 37 L.Ed.2d 396 (1973), the latter case

relating to the applicability of Section 718, we withheld

1 Upon the entry of a final order by a court of the United States

against a local educational agency, a State (or any agency thereof),

or the United States (or any agency thereof), for failure to comply

with any provision of this chapter or for discrimination on the

basis of race, color, or national origin in violation of title YI of

the Civil Rights Act of 1964, or the fourteenth amendment to the

Constitution of the United States as they pertain to elementary

and secondary education, the court, in its discretion, upon a finding

that the proceedings were necessary to bring about compliance,

may allow the prevailing party, other than the United States, a

reasonable attorney’s fee as part of the costs.

Appeals Court Opinion

25a

the disposition of the instant appeal pending its decisions

in those cases, which have now been handed down. Gilmore

v. Montgomery, ----- U.S. ----- , 94 S.Ct. 2416, 41 L.Ed.2d

-—— (1974); Bradley v. Richmond School Board,-----U.S.

— , 94 S.Ct. 2006, 40 L.Ed.2d 476 (1974). Even with the

guidance provided, the central issue in this cause continues

to be whether a controversy which would support injunctive

relief remained after the withdrawal of the single private

school request for use of public facilities.

Although the question for resolution on this appeal might

be posed in terms of standing, i.e., did plaintiffs show an

injury to themselves resulting from defendants’ action;2 *

or in terms of ripeness, i.e., did plaintiffs demonstrate a

realistic possibility that the actions of defendants would

injure them;8 or in terms of abuse of discretion, i.e-., was

the injunction unsupported or overbroad,4 * the issue here

2 In Pevsner v. Eastern Air Lines, 493 F.2d 916 (5th Cir. 1974),

we affirmed the dismissal for lack of standing of a class action

claim by one who had been overcharged for an air line ticket,

because the initial overcharge was placed on a Bank Americard

form and somehow got reduced to a proper charge before being

billed to Pevsner.

8 In International Tape Manufacturers Association v. Gerstein,

494 F.2d 25 (5th Cir. 1974), an injunction against enforcement

of a Florida tape piracy statute was vacated as granted in a con

troversy lacking ripeness where the proof failed to disclose how

plaintiffs’ members would be affected by the law or that any

prosecution had been had or threatened under the law. See n. 8

comparing the doctrines of “standing”, “ripeness” and “mootness”.

4 Only Mississippi State University was shown to have acted,

yet the injunction controlled the actions of the Board of Trustees

at all eight collegiate institutions under their control which were

located throughout the state. Its single action was a year prior to

our decision in Gilmore. The district court never entered any

order on the maintainability of this action as a class suit. Fed.R.

Civ.P. 23(c). The effect on Clarksdale high school students of the

proposed but aborted Starkville basketball tournament was not

demonstrated except by the unarticulated inferences which might

Appeals Court Opinion

26a

is most properly classified as raising the question of moot

ness, i.e., does the cause lack the concrete adverseness nec

essary to an Article III case or controversy?

This court has on several occasions this year held causes

moot—when the allegedly offending action was rescinded,

see Barron v. Bellairs, 5 Cir., 496 F.2d 1187 [1974] (new

Georgia welfare statute enacted prior to entry of injunc

tive relief),—when the proof failed to show the complain

ing party was or would be injured by the challenged actions

of the defendant, see National Lawyers Guild v. Board of

Regents, 5 Cir., 490 F.2d 97 (injunction requiring use of

college facility for meeting held moot -where meeting date

set had long gone by and no showing was made that re

quired co-sponsorship by college dean had been sought or

refused); and Merkey v. Board of Regents, 5 Cir., 493 F.2d

790 (where plaintiff was a non-student at the time of

appeal and no student was shown to seek recognition for

a college club, the action demanding recognition was moot

—Judge Goldberg dissented),—and when the matter in

controversy has become passe, see De Simone v. Lindford,

5 Cir. 494 F.2d 1186 (request for injunctive relief pending

completion of administrative review held moot upon final

agency decision); United States Servicemen’s Fund v. Kil

leen Independent School District, 5 Cir., 489 F.2d 693 (right

to use a high school auditorium for a “Counter-USO Show”

by Viet Nam war protesters held moot after the conflict

ended); and Hollon v. Mathis Independent School District,

5 Cir., 491 F.2d 92 (injunction suspending a school rule

against married athletes mooted by plaintiff’s graduation).

Appeals Court Opinion

be drawn from facts established in the record from Norwood v.

Harrison, supra. The asserted affirmative duty of the Board to

adopt a policy forbidding the grant of exclusive use of facilities

to private school students is devoid of support in the record. See